Abstract

We study quantum correlation of a massive scalar field in a maximally entangled state in de Sitter space. We prepare two observers, one in a global chart and the other in an open chart of de Sitter space. We find that the state becomes less entangled as the curvature of the open chart gets larger. In particular, for the cases of a massless and a conformally coupled scalar field, the quantum entanglement vanishes in the limit of infinite curvature. However, we find that the quantum discord never disappears, even in the limit that entanglement disappears.

1. Introduction

The quantum entanglement between two free modes of a scalar field becomes less entangled if observers who detect each mode are relatively accelerated. In fact, the authors in [1,2] considered two free modes of a scalar field in flat space. One is detected by an observer in an inertial frame, and the other by a uniformly accelerated observer. They evaluated the entanglement negativity—a measure of entanglement for mixed states—between the two free modes (which started in a maximally entangled state) to characterize the quantum entanglement, and found that the entanglement disappeared for the observer in the limit of infinite acceleration.

From the view of the equivalence principle, it is interesting to extend the analysis to curved spacetime. Recently, entanglement entropy—a measure of entanglement for pure states—in de Sitter spacetime has been studied in the Bunch–Davies vacuum [3]. Moreover, entanglement negativity—a measure of entanglement for mixed states—has been also studied in [4]. It turns out that the entanglement negativity disappears in the infinite curvature limit, which is consistent with the result of accelerating system.

It was recently shown that quantum entanglement is not the only kind of quantum correlations possible, and are merely a particular characterization of quantumness. In fact, other quantum correlations have now been experimentally found, and quantum discord is known to be a measure of all quantum correlations, including entanglement [5,6]. This measure can be non-zero, even in the absence of entanglement. In order to see the observer dependence of all quantum correlations (i.e., the total quantumness), the quantum discord between two free modes of a scalar field in flat space—which are detected by two observers in inertial and non-inertial frames, respectively—has also been discussed [7,8]. They found that the quantum discord—in contrast to the entanglement—never disappears, even in the limit of infinite acceleration. Again, from the view of the equivalence principle, it is important to verify if the same happens in de Sitter cases. This has been done by us in [9], and this contribution is a report of the work.

The organization of the paper is as follows. In Section 2, we review the quantum information theoretic basis of quantum discord. In Section 3, we quantize a free massive scalar field in de Sitter space, and we introduce two observers, Alice and Bob, who detect two free modes of the scalar field which start in an entangled state. We obtain the density operator for Alice and Bob. In Section 4, we compute the entanglement negativity. In Section 5, we evaluate the quantum discord in de Sitter space. In the final section, we summarize our results.

2. Quantum Discord

Quantum discord is a measure of all quantum correlations (including entanglement) for two subsystems [5,6]. For a mixed state, this measure can be nonzero, even if the state is unentangled. It is defined by quantum mutual information and computed by optimizing over all possible measurements that can be performed on one of the subsystems.

In classical information theory, the mutual information between two random variables A and B is defined as

where the Shannon entropy is used to quantify the ignorance of information about the variable A with probability , and the joint entropy with the joint probability of both events A and B occurring. The mutual information (1) measures how much information A and B have in common.

Using Bayes theorem, the joint probability can be written in terms of the conditional probability as

where is the probability of A given B. The joint entropy can then be written as .

Plugging this into Equation (1), the mutual information can be expressed as

where has been used, and the conditional entropy is defined as ; i.e., the average over B of Shannon entropy of event A, given B. Equations (1) and (3) are classically equivalent expressions for the mutual information.

If we try to generalize the concept of mutual information to a quantum system, the above two equivalent expressions do not yield identical results, because measurements performed on subsystem B disturb subsystem A. In a quantum system, the Shannon entropy is replaced by the von Neumann entropy , where ρ is a density matrix. The probabilities , , and are replaced, respectively, by the density matrix of the whole system , the reduced density matrix of subsystem A, , and the reduced density matrix of subsystem B, .

In order to extend the idea of the conditional probability to the quantum system, we use projective measurements of B described by a complete set of projectors , where i distinguishes different outcomes of a measurement on B. There are of course many different sets of measurements that we can make. Then, the state of A after the measurement of B is given by

A quantum analog of the conditional entropy can then be defined as

which corresponds to the measurement that least disturbs the overall quantum state; that is, to avoid dependence on the projectors.

Thus, the quantum mutual information corresponding to the two expressions Equations (1) and (3) is defined, respectively, by

The quantum discord is then defined as the difference between the above two expressions

The quantum discord thus vanishes in classical mechanics, however it appears not to in some quantum systems.

3. Setup of Quantum States

We consider a free scalar field ϕ with mass m in de Sitter space represented by the metric . The action is given by

The coordinate systems of open charts in de Sitter space with the Hubble radius can be divided into two parts, which we call R and L. Their metrics are given, respectively, by

where is the metric on the two-sphere. Note that the regions L and R covered by the coordinates and , respectively, are the two causally disconnected open charts of de Sitter space. The harmonic functions on the three-dimensional hyperbolic space are defined by

where the eigenvalues p normalized by H take positive real values. We define a mass parameter

The Bogoliubov transformation between the Bunch–Davies vacuum and R, L vacua, derived in [3], is expressed as

where the states and span the Fock space for the L and R open charts. Here, eigenvalue is given by

Note that in the case of conformal invariance () and masslessness (), we have .

The solutions in the Bunch–Davies vacuum are related to those in the R, L vacua through Bogoliubov transformations. Using the transformation, we find that the ground state of a given mode seen by an observer in the global chart corresponds to a two-mode squeezed state in the open charts. These two modes correspond to the fields observed in the R and L charts. If we probe only one of the open charts (say L), we have no access to the modes in the causally disconnected R region and must therefore trace over the inaccessible region. This situation is analogous to the relationship between an observer in a Minkowski chart and another in one of the two Rindler charts in flat space, in the sense that the global chart and Minkowski chart cover the whole spacetime geometry, while open charts and Rindler charts cover only a portion of the spacetime geometry, and thus horizons exist.

We start with two maximally entangled modes with and s of the free massive scalar field in de Sitter space,

We assume that an observer, Alice, in the global chart has a detector which only detects mode s and another observer, Bob, in an open chart has a detector sensitive only to mode k. When Bob resides in the L region, the Bunch–Davies vacuum with mode k can be expressed as a two-mode squeezed state of the R and L vacua

The single particle excitation state is then calculated from Equation (16) as

Since the R region is inaccessible to Bob, we need to trace over the states in the R region. If we plug Equations (16) and (17) into the initial maximally entangled state (15), the reduced density matrix after tracing out the states in the R region is represented as

where

with . This is a mixed state.

4. Entanglement Negativity

Let us first calculate the entanglement negativity—a measure of entanglement for mixed states. This measure is defined by the partial transpose, the non-vanishing of which provides a sufficient criterion for entanglement. If at least one eigenvalue of the partial transpose is negative, then the density matrix is entangled.

If we take the partial transpose with respect to Alice’s subsystem, then we find

where

The negativity is defined by summing over all the negative eigenvalues

and there exists no entanglement when . However, this measure is not additive and not suitable for multiple subsystems. The logarithmic negativity is thus a better measure than the negativity in this scenario, and is defined as

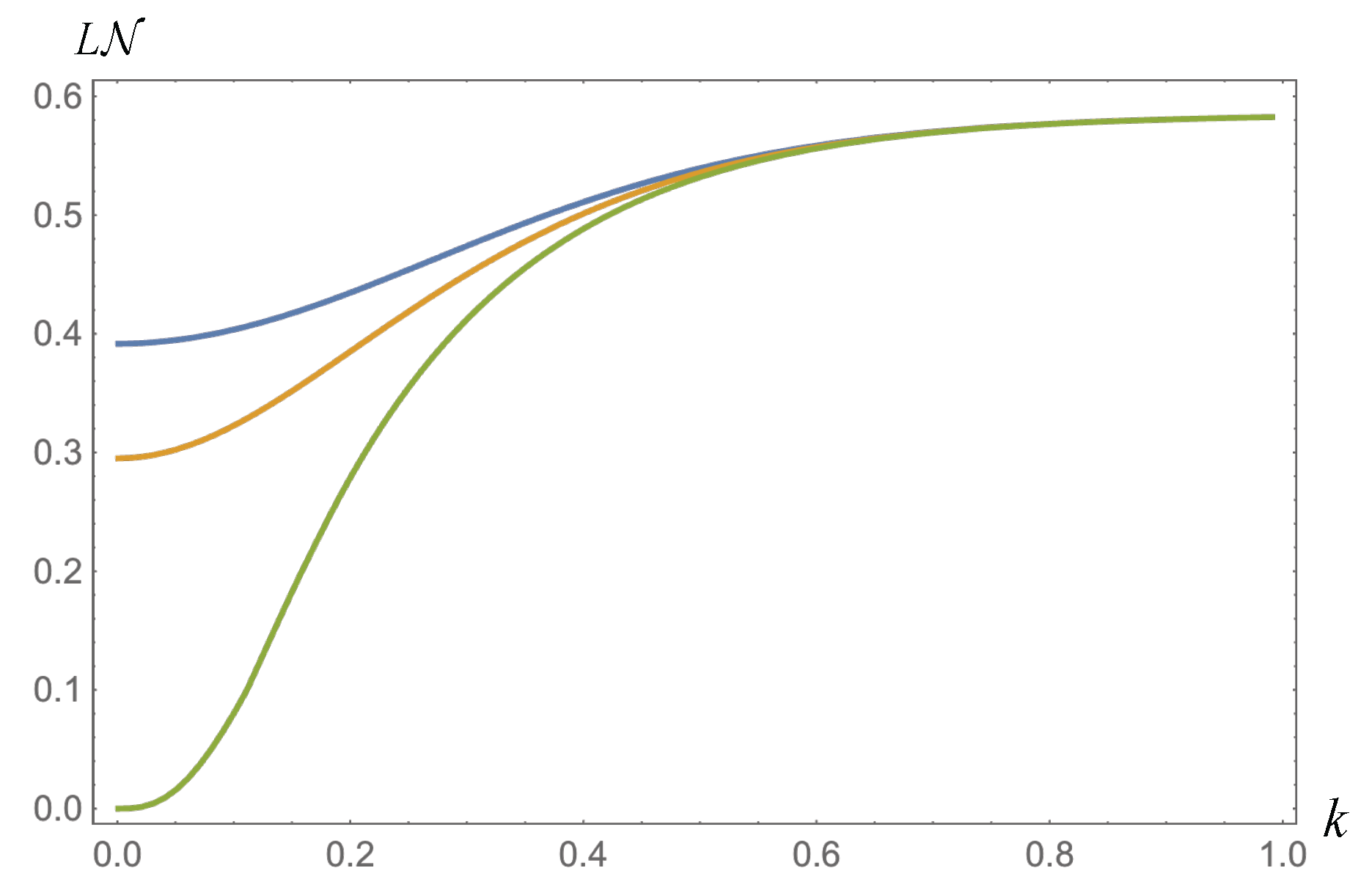

The state is entangled when . We sum over all negative eigenvalues and calculate the logarithmic negativity. We focus on Alice and Bob’s detectors for modes of momentum s and k, and thus do not integrate either over k, nor a volume integral over the hyperboloid. We plot the logarithmic negativity in Figure 1. For and , the logarithmic negativity vanishes in the limit of ; that is, in the limit of infinite curvature. This is consistent with the flat space result, where the entanglement vanishes in the limit of infinite acceleration of the observer. Here we stress that the entanglement weakens, but survives even in the limit of infinite curvature for a massive scalar field other than and , as can be seen from Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Plots of the logarighmic negativity as a function of k. The blue line is for , 1; the yellow is for , ; and the green is for , .

5. Quantum Discord in de Sitter Space

Next we calculate the overall quantumness of the system given by the quantum discord. We will make our measurement on Alice’s side. The quantum discord is

The state is split into Alice’s subsystem (two dimensions) and Bob’s subsystem (infinite dimensional). Then, Alice’s density matrix is easy to obtain as

and we get . For the von Neumann entropy of the whole system , we need to find the eigenvalues of numerically.

In order to calculate the quantum conditional entropy , we restrict ourselves to projective measurements on Alice’s subsystem described by a complete set of projectors

where , I is the identity matrix and are the Pauli matrices. Here, a choice of the corresponds to a choice of measurement, and we will thus be interested in the particular measurement which minimises the disturbance on the system. Then, the density matrix after the measurement is

The trace of it is calculated as

where we used and

By using the parametrization is found to be independent of the phase factor ϕ:

Thus, the quantum discord (22) is now expressed as

We will find eigenvalues of , and numerically, and find θ that minimizes the above . We found that minimize . Note that the convergence of the sum for is not fast for and in the limit of , because in the summation becomes 1, so we have truncated our plot for small k.

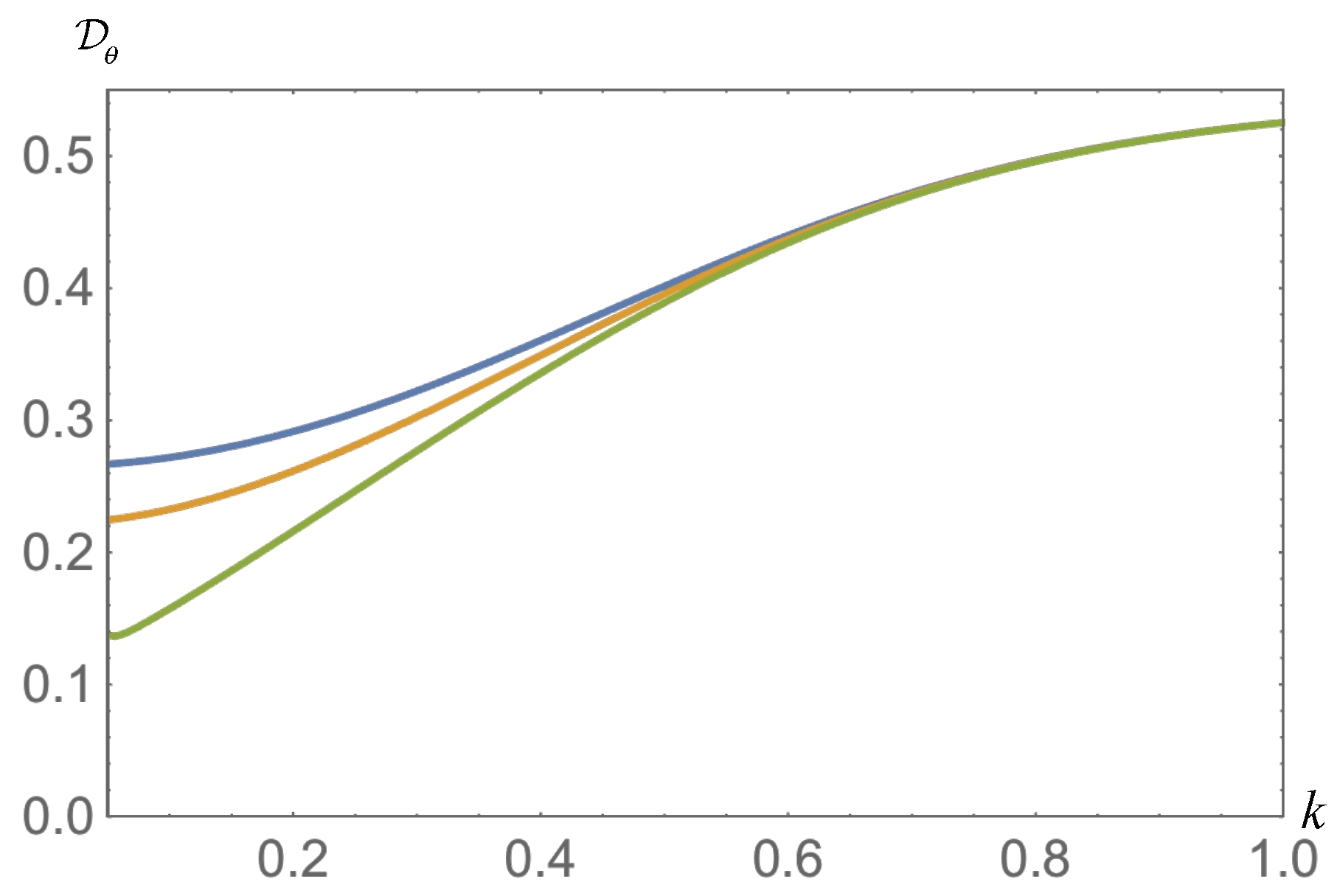

We plot the quantum discord in Figure 2. For and , the quantum discord does not vanish, even in the limit of ; that is, in the limit of infinite curvature. This is consistent with the flat space result where the quantum discord survives even in the limit of infinite acceleration of the observer.

Figure 2.

Plots of the quantum discord as a function of k. The blue line is for , 1; the yellow is for , ; and the green is for , .

6. Discussion

In this work, we investigated quantum discord between two free modes of a massive scalar field in a maximally entangled state in de Sitter space. We introduced two observers—one in a global chart and the other in an open chart of de Sitter space—and then determined the quantum discord created by each detecting one of the modes. This situation is analogous to the relationship between an observer in Minkowski space and another in one of the two Rindler wedges in flat space. In the case of Rindler space, it is known that the entanglement vanishes when the relative acceleration becomes infinite [1]. In de Sitter space, on the other hand, the observer’s relative acceleration corresponds to the scale of the curvature of the open chart. We first evaluated entanglement negativity, and then quantum discord in de Sitter space. We found that the state becomes less entangled as the curvature of the open chart gets larger. In particular, for a massless scalar field and a conformally coupled scalar field , the entanglement negativity vanishes in the limit of infinite curvature. However, we showed that quantum discord does not disappear, even in the limit that the entanglement negativity vanishes. In addition, we found that both the entanglement negativity and quantum discord survive even in the limit of infinite curvature for a massive scalar field. These findings seem to support the equivalence principle.

It is intriguing to observe that our results indicate that quantum discord may gives rise to an observable signature of quantumness of primordial fluctuations generated during inflation. If observed, this would be strong evidence for an inflationary scenario.

Acknowledgments

SK was supported by IKERBASQUE, the Basque Foundation for Science. JShock is grateful for the National Research Foundation (NRF) of South Africa under grant number 87667. JSoda was in part supported by MEXT KAKENHI Grant Number 15H05895.

Author Contributions

The authors contribute equally to this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Fuentes-Schuller, I.; Mann, R.B. Alice falls into a black hole: Entanglement in non-inertial frames. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 95, 120404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsing, P.M.; Fuentes-Schuller, I.; Mann, R.B.; Tessier, T.E. Entanglement of Dirac fields in non-inertial frames. Phys. Rev. A 2006, 74, 032326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldacena, J.; Pimentel, G.L. Entanglement entropy in de Sitter space. J. High Energ. Phys. 2013, 2013, 038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanno, S.; Shock, J.P.; Soda, J. Entanglement negativity in the multiverse. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2015, 2015, 015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollivier, H.; Zurek, W.H. Quantum Discord: A Measure of the Quantumness of Correlations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001, 88, 017901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, L.; Vedral, V. Classical, quantum and total correlations. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 2001, 34, 6899–6905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, A. Quantum discord between relatively accelerated observers. Phys. Rev. A 2009, 80, 052304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Deng, J.; Jing, J. Classical correlation and quantum discord sharing of Dirac fields in non-inertial frames. Phys. Rev. A 2010, 81, 052120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanno, S.; Shock, J.P.; Soda, J. Quantum discord in de Sitter space. arXiv, 2016; arXiv:1608.02853. [Google Scholar]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).