Primordial Black Holes and Instantons: Shadow of an Extra Dimension

Abstract

1. Introduction

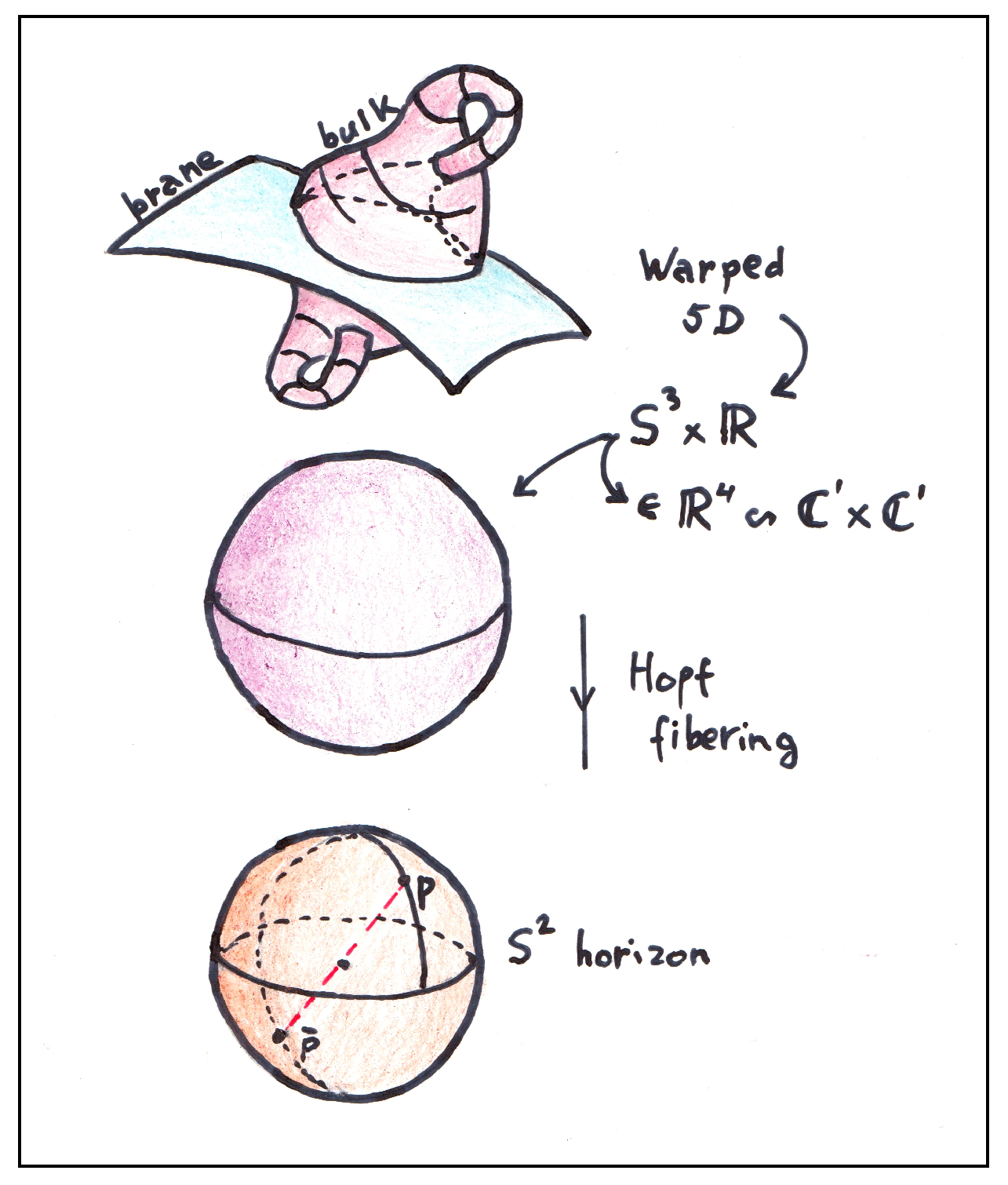

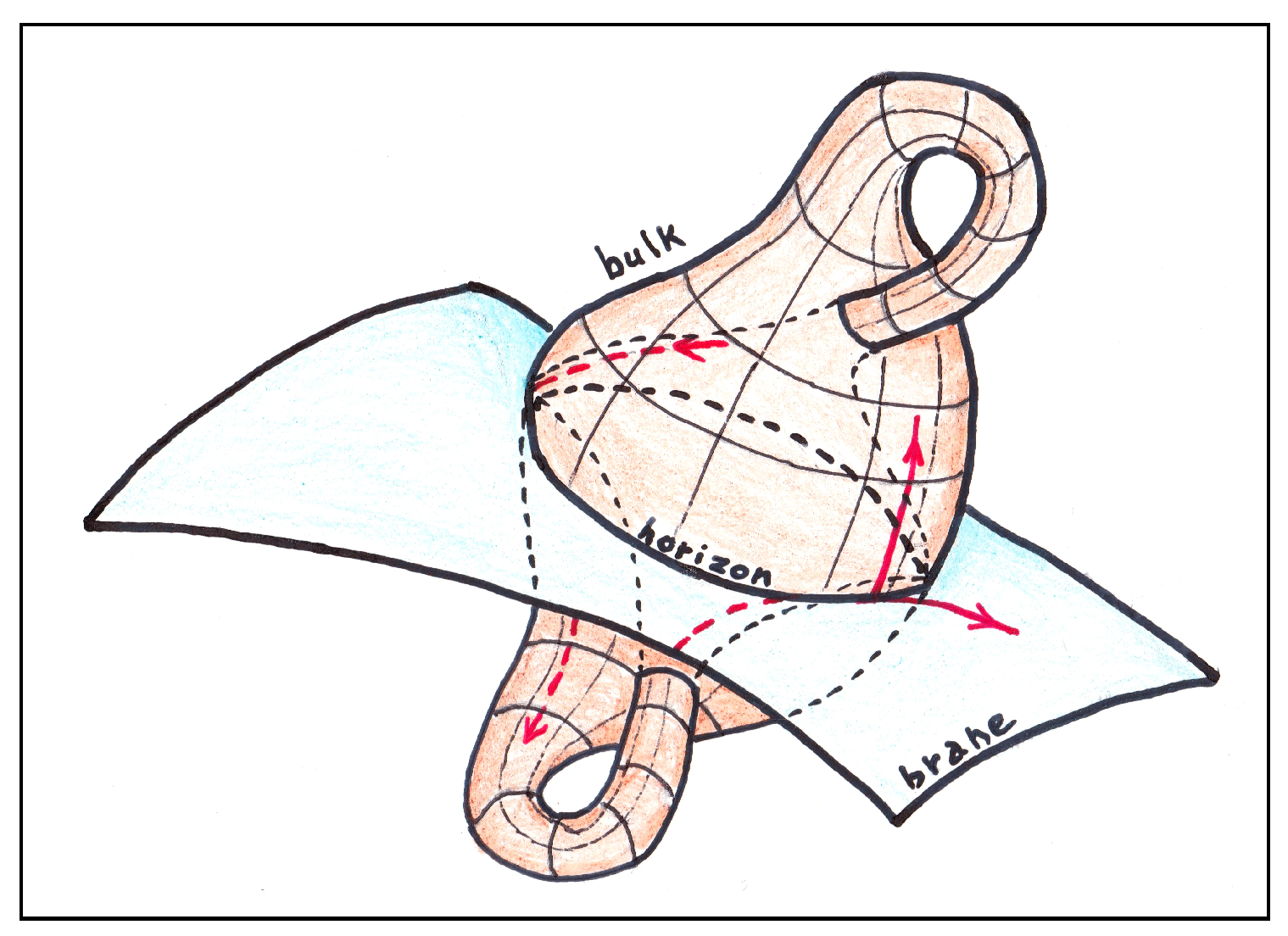

2. The Model

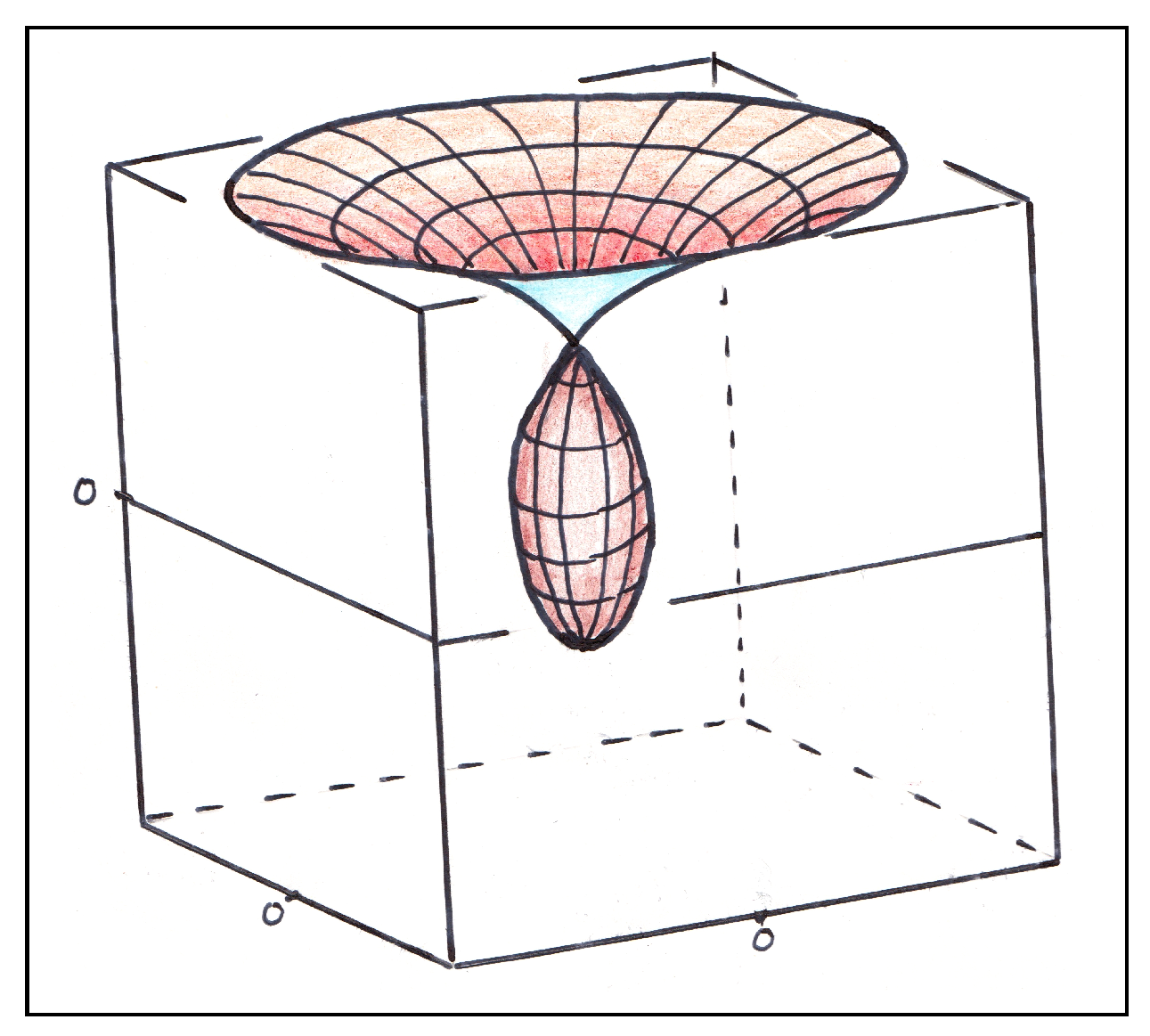

Some Conjectures

3. The New Topology and

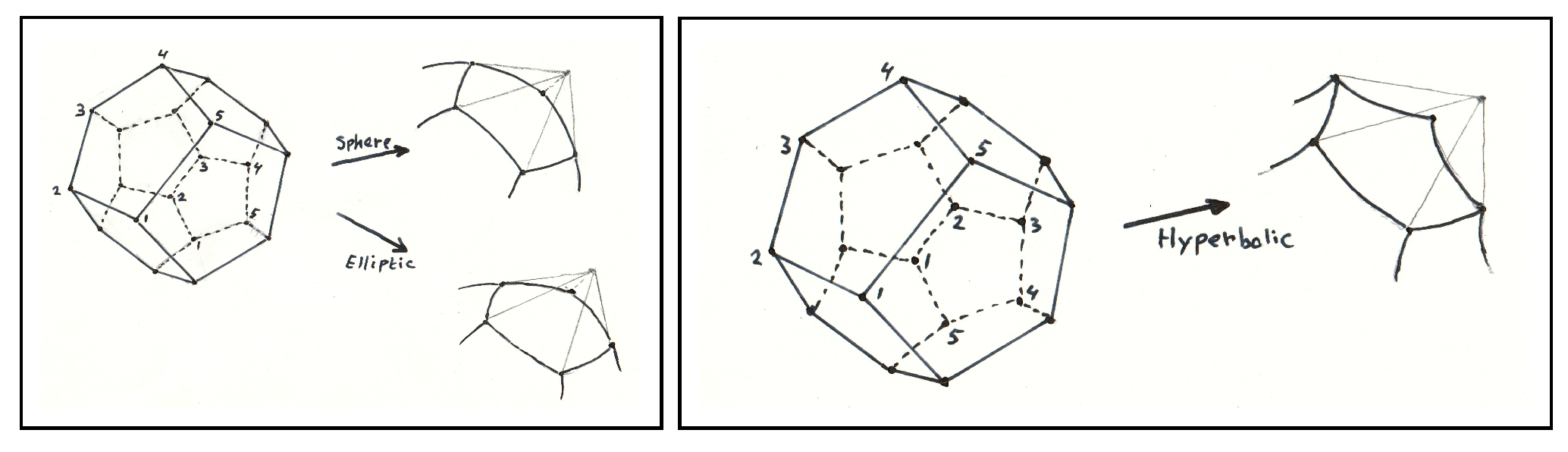

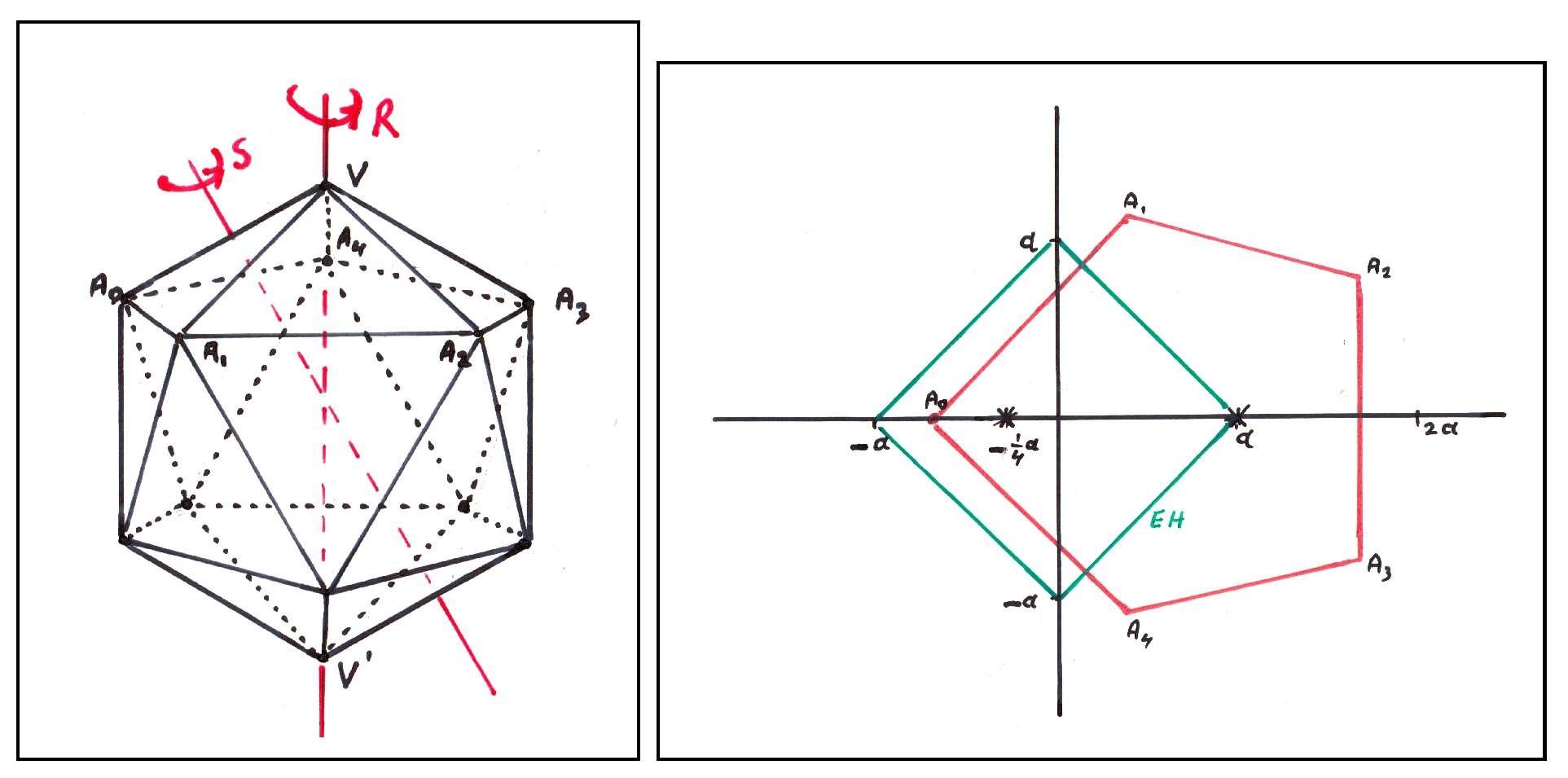

3.1. Summary of Earlier Treatments

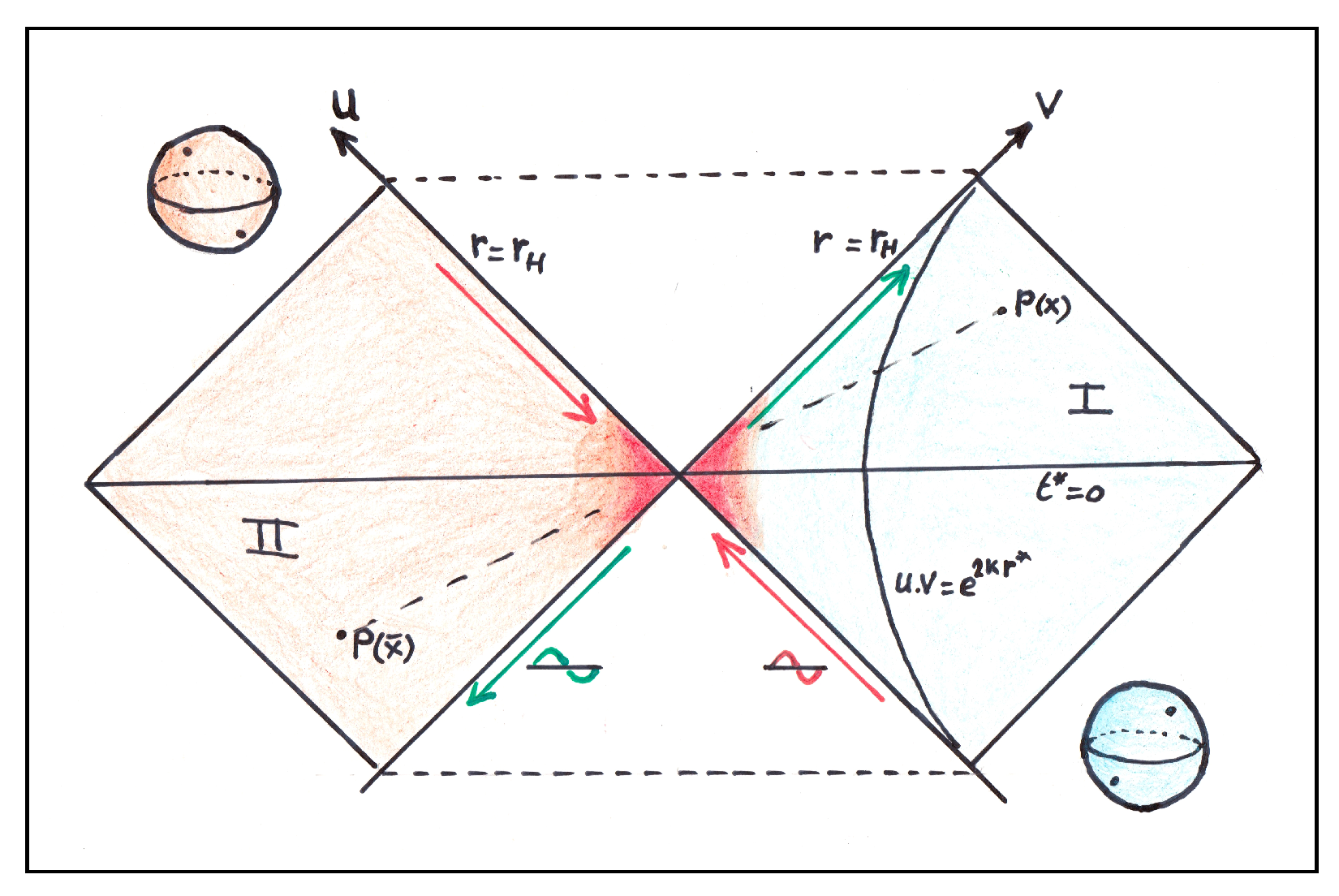

3.2. Treatment of the Hawking Particles

3.3. The New Antipodal Map and CPT Invariance

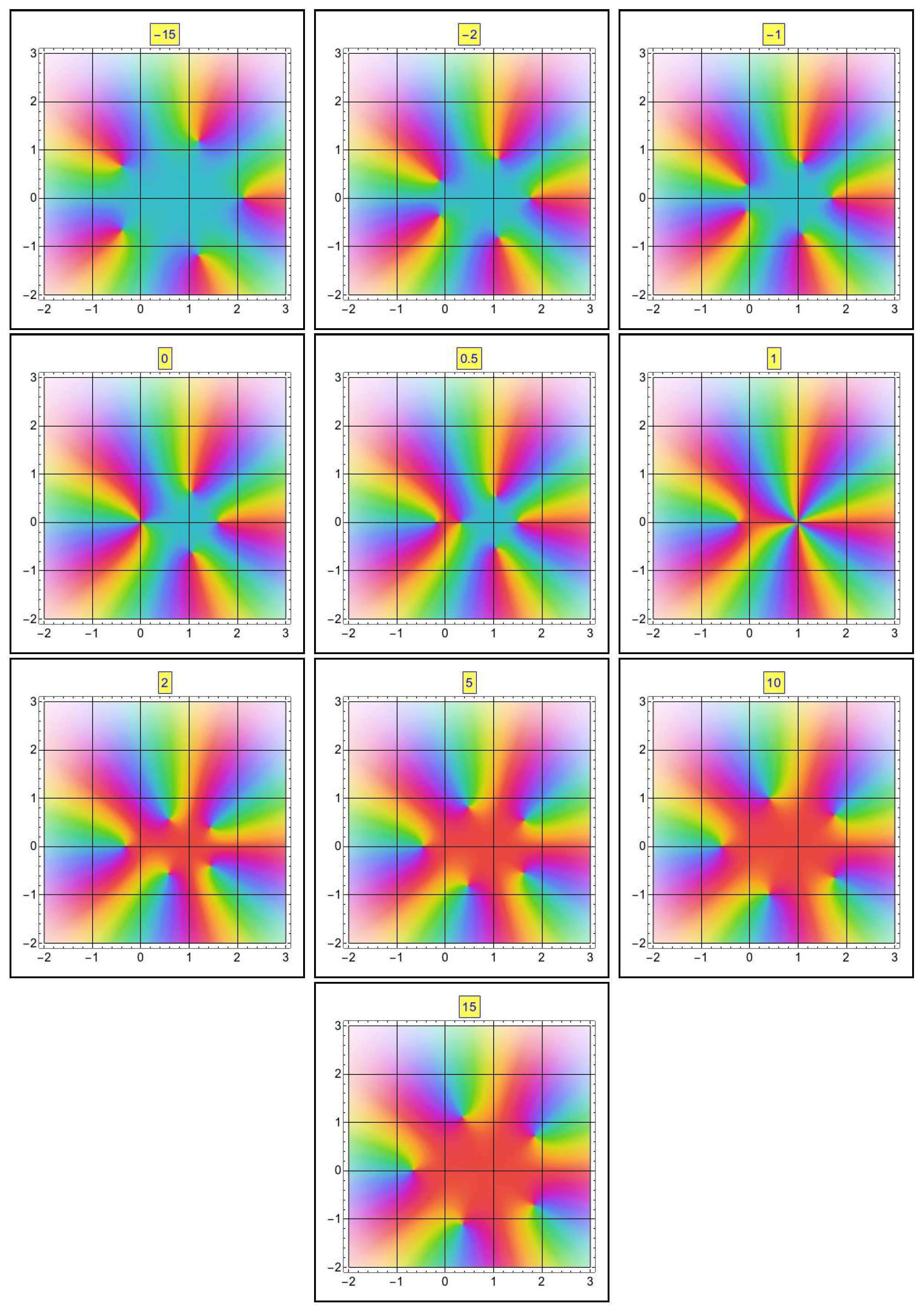

4. The Instanton

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | |

| 2 | On a FLRW spacetime, the dilaton field is then considered as a warp factor, which can also be expressed exactly in , where the bulk part becomes ([23]). You will need these solutions when the Hawking particles become hard. |

| 3 | Schrödinger applies the case of an expanding universe. |

| 4 | Note that there are two possible paths for the Hawking particle in the bulk, due to the symmetry. |

| 5 | Recently, primordial BHs have been observed, which could not be formed by contracting matter. |

| 6 | These are the dihedral, Möbius, tetrahedral, octahedral and icosahedral groups respectively. |

| 7 | The study of fifth-degree equations written in various forms, goes back a long way. See, for example, Klein’s classic book [42]. |

References

- Hawking, S. Particle creation by black holes. Comm. Math. Phys. 1975, 43, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekenstein, A. Black holes and the second law. Lett. Nuovo C. 1972, 4, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ’t Hooft, G. Dimensional reduction in quantum gravity. arXiv 1993, arXiv:Gr-qc/9310026. [Google Scholar]

- Maldacena, J.M. The large-N limit of superconformal field theories and supergravity. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 1999, 38, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, J. Introduction to the AdS/CFT correspondence. Les Houches Lect. Notes 2015, 97, 163. [Google Scholar]

- Bekenstein, A. The quantum mass spectrum of the Kerr black hole. Lett. Nuovo C 1974, 11, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekenstein, A. Advances in the Interplay Between Quantum and Gravity Physics; Bergmann, P.G., De Sabbata, V., Eds.; Kluwer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- ’t Hooft, G. The quantum black hole as a theoretical lab, a pedagogical treatment of a new approach. arXiv 2019, arXiv:Grqc/ 190210469. [Google Scholar]

- Hawking, S.W. Gravitationally collapsed objects of very low mass. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1971, 152, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, L.; Sundrum, R. A large mass hierarchy from a small extra dimension. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1999, 83, 3370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, L.; Sundrum, R. An alternative to compactification. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1999, 83, 4690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaluza, T. Zum Unitätsproblem der Physik Sitzungsber. Preuss. Akad. Wiss (Math. Phys.) 1921, 1921, 966–972. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, O. Quantentheorie und fünfdimensionale Relativitätsthe- orie. Z. Phys A 1926, 37, 859. [Google Scholar]

- ’t Hooft, G. Local conformal symmetry: The missing symmetry component for space and time. Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 2015, 24, 1543001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger, E. Expanding Universe; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons, G.W. The elliptic interpretation of black holes and quantum mechanics. Nucl. Phys. B 1986, 271, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ’t Hooft, G. Black hole unitarity and antipodal entanglement. Found. Phys. 2016, 46, 1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slagter, R.J. Alternative for black hole paradoxes. Int. J. Mod. Phys. A 2022, 37, 2250176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slagter, R.J. Quantum black holes in conformal dilaton—Higgs gravity on warped spacetimes. Universe 2023, 9, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slagter, R.J. Primordial black holes and instantons: Shadow of an extra dimension. Int. J. Mod. Phys. A 2024, 40, 2450148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slagter, R.J. Black Holes and Cosmic Strings Revisited; Amazon Publishing: Seattle, WA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Slagter, R.J. Everything You Need to Know About Black Holes: Shadow of an Extra Dimension; Cambridge Scholar Publications: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Slagter, R.J.; Pan, S. A new fate of a warped 5D FLRW model with a U(1) scalar gauge field. Found. Phys. 2016, 46, 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, B. The quintic, the icosahedron, and elliptic curves. Not. Amer. Math. Soc. 2024, 71, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartle, J.B. Gravity; Pearson Education, Inc.: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Baňados, M.; Teitelboim, C.; Zanelli, T. The black hole in three dimensional space time. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1992, 69, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compère, G. Advanced Lectures on General Relativity; Lecture notes in Physics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- King, R.B. Beyond the Quartic Equation; Birkhauser: Boston, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Eguchi, T.; Hanson, J. Self-dual solutions to euclidean gravity. Ann. Phys. 1979, 120, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aneva, B. Symmetry of the Riemann operator. arXiv 1998, arXiv:08041618V1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, N.; Whiting, B.F. Quantum field theory and the antipodal identification of black-holes. Nucl. Phys. B 1987, 283, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, G.W. Topology and topology change in general relativity. Class. Quantum Grav. 1993, 10, S75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betzios, P.; Gaddam, N.; Papadoulaki, O. Black holes, quantum chaos, and the Riemann hypothesis. CsiPost Phys. Core 2021, 4, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betzios, P.; Gaddam, N.; Papadoulaki, O. The black hole S-matrix from quantum mechanics. J. High Energy Phys. 2021, 11, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ’t Hooft, G. The black hole firewall transformation and realism in quantum mechanics. Universe 2021, 7, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbantke, U. Two-level quantum systems: States, phases, and holonomy. Am. J. Phys. 1990, 59, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freed, D.S.; Uhlenbeck, K.K. Instantons and Four-Manifolds; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Felsager, B. Geometry, Particles and Fields; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons, G.W.; Hawking, S.W. Euclidean Quantum Gravity; World Scientific: Singapore, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Joyce, D.D. Explicit construction of self-dual-manifolds. Duke Math. J. 1995, 77, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atiyah, M.F.; Hitchin, N.J.; Singer, I.M. Selfduality in four-dimensional riemannian geometry. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 1978, 362, 425. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, F. Lectures on the Icosahedron and the Solution of Equations of the Fifth Degree; Trübner and Co.: London, UK, 1888. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Slagter, R.J. Primordial Black Holes and Instantons: Shadow of an Extra Dimension. Universe 2026, 12, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe12010026

Slagter RJ. Primordial Black Holes and Instantons: Shadow of an Extra Dimension. Universe. 2026; 12(1):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe12010026

Chicago/Turabian StyleSlagter, Reinoud Jan. 2026. "Primordial Black Holes and Instantons: Shadow of an Extra Dimension" Universe 12, no. 1: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe12010026

APA StyleSlagter, R. J. (2026). Primordial Black Holes and Instantons: Shadow of an Extra Dimension. Universe, 12(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe12010026