Models of Charged Gravastars in f(T)-Gravity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Foundations of f(T) Gravity

3. Tetrad Vectors and Conformal Killing Vectors (CKVs): Fundamental Concepts

4. The General Einstein–Maxwell Equations (EME) of the Field

4.1. Analytical Solutions for the Interior Field Equations Gravity

- We will proceed to analyze the first scenario when ,

- We will proceed to analyze the second scenario when:, indicates that is a linear function of the torsion scalar . When and , we revert to the standard model. In this scenario, the field equations align with those of the conventional Ricci scalar model.

- We will now move on to analyze the third scenario when .

4.2. Thin Shell Solution for the Gravitational Field Equations

- We will proceed to analyze the first scenario when .

- We will proceed to analyze the second scenario when ,

- We will now move on to analyze the third scenario when .

4.3. Exterior Spacetime Solution for a CGM

- We will proceed to analyze the first scenario with .In this case, Equations (96)–(98) results in

- We will proceed to analyze the second scenario with , In this case, Equations (96)–(98) results in

4.4. Proper Length of the Thin Shell in CGMs

4.5. Entropy and Thermodynamic Stability of the CGM Shell

4.6. Energy Content and Stability of the CGM Shell

5. Junction Condition

- We will proceed to analyze the first scenario with the model

- We will proceed to analyze the second scenario with the model . The following result is obtained by substituting the expressions from Table 3 into Equations (133) and (133):

- We will proceed to analyze the second scenario with the model .

6. Conclusions

- i.

- Structural Role: Maintains continuity between distinct spacetime regions, mediates the transition of gravitational properties, and governs the matching conditions for the metric tensor.

- ii.

- Physical Significance: Determines the stability criteria through surface tension effects, hosts non-trivial stress-energy distributions, and acts as the primary locus for energy condition verification.

- iii.

- Morphological Properties: Characterized by an intrinsic length scale significantly smaller than system radius, exhibits hypersurface-embedded dynamics, and demonstrates anisotropic pressure components.

- (1)

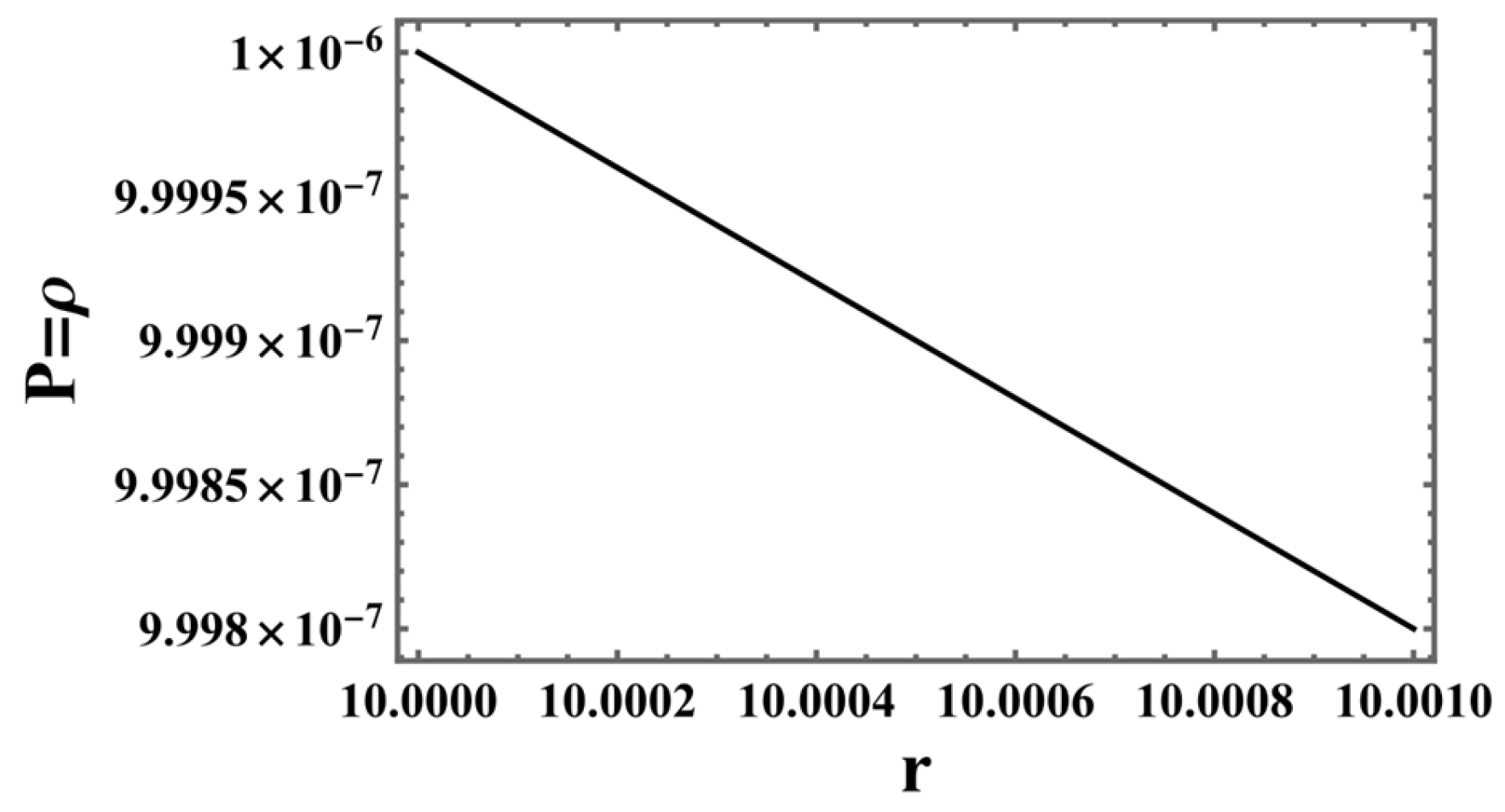

- Pressure-density: Figure 1 depicts a high-resolution analysis of the internal structure of a CGMs, focusing on a thin shell region. The graph illustrates the pressure and density profile within this shell, where the matter is modeled as an ultrarelativistic fluid governed by the equation of state . The plotted values demonstrate a gradual decrease in both pressure and density with increasing radial distance from the center. This gradient is a critical feature of the shell’s hydrostatic equilibrium. The primary objective of this analysis is to precisely characterize the behavior of matter under extreme conditions within the CGMs shell. This detailed profile is essential for solving the Tolman–Oppenheimer–Volkoff (TOV) equations, which describe the hydrostatic equilibrium and overall structure of the CGMs. Understanding these fine-scale details is paramount for accurately modeling the CGMs internal structure, assessing its stability, and calculating its gravitational redshift properties.

- (2)

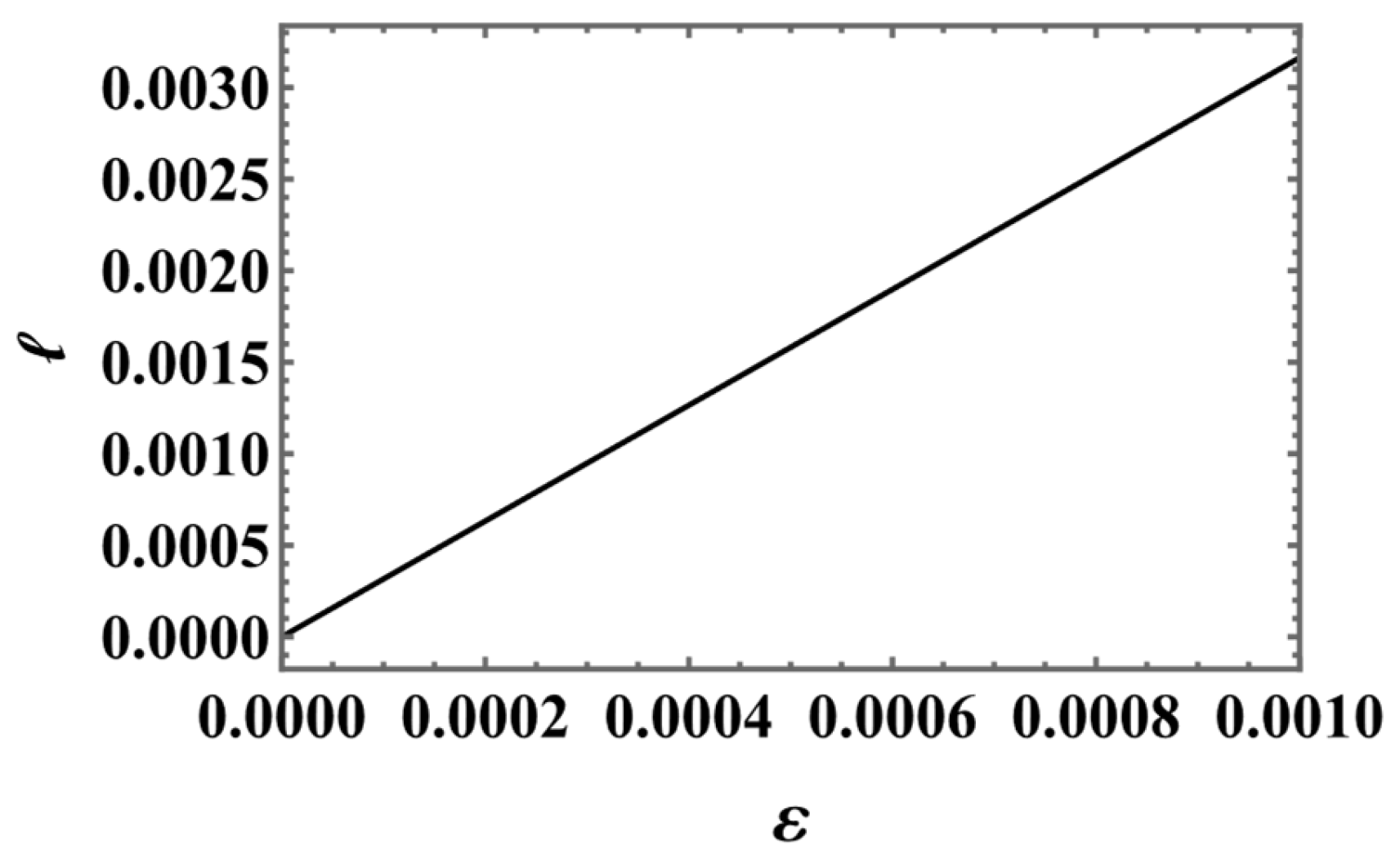

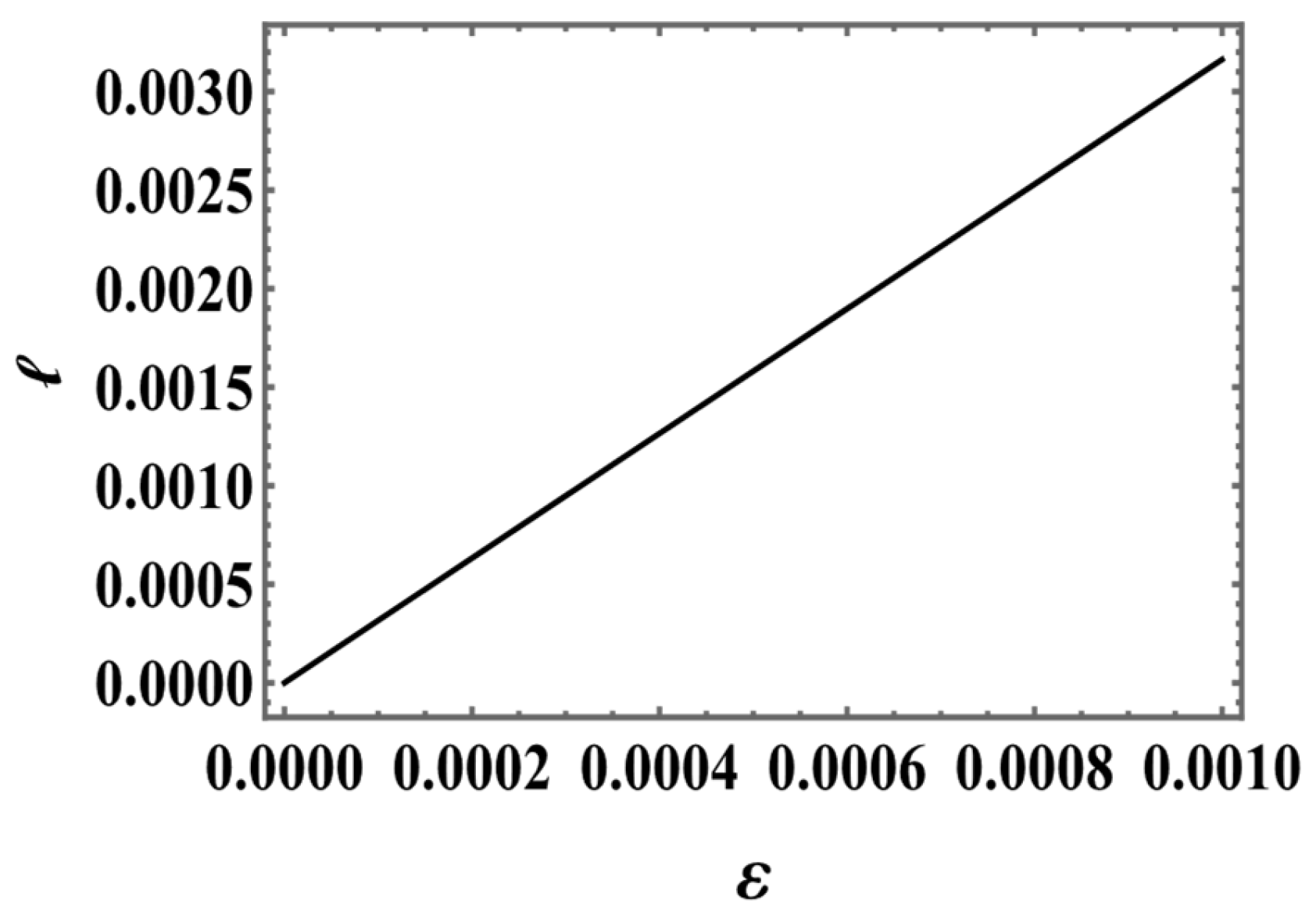

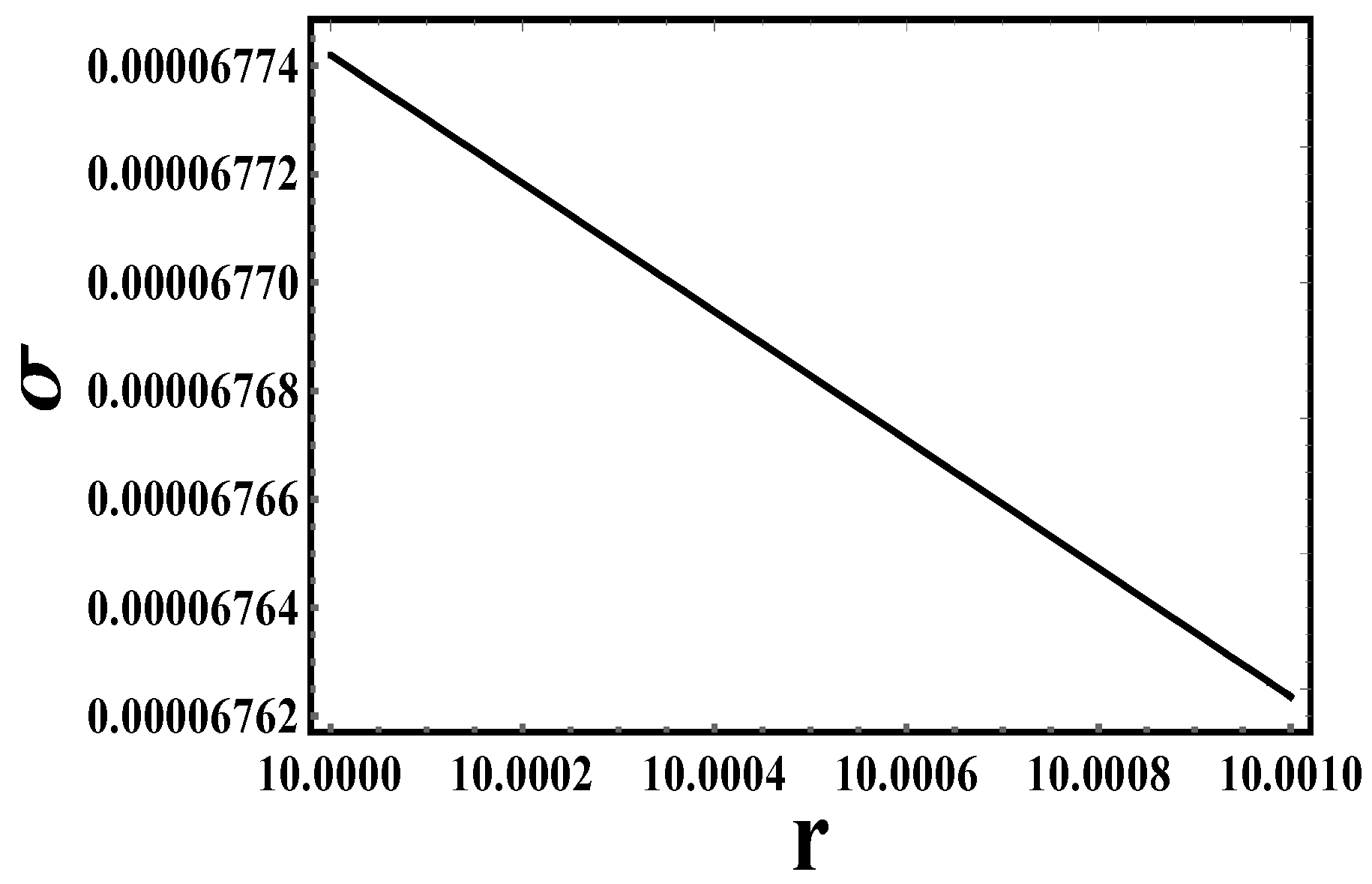

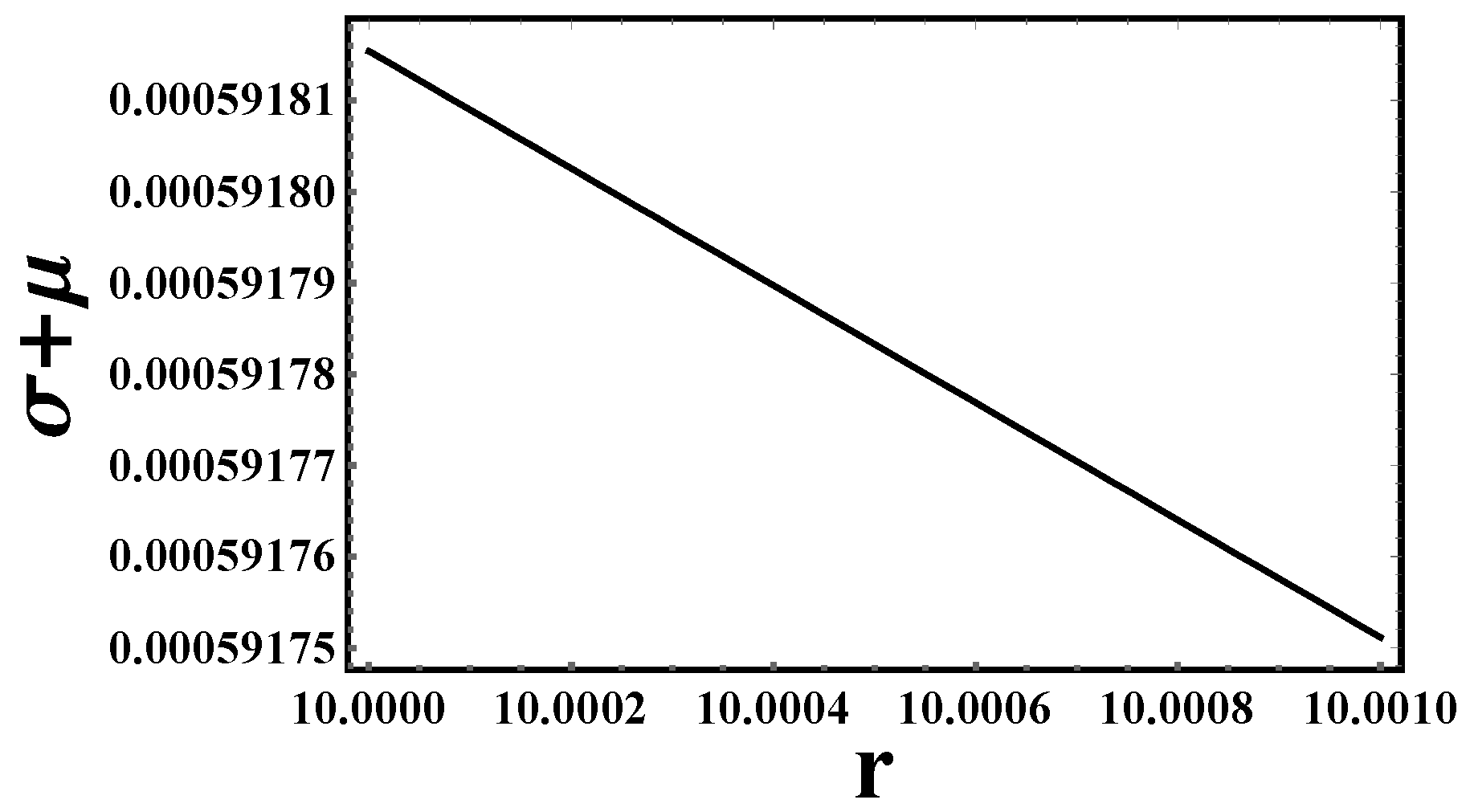

- Proper length: Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4 reveal a fundamental scaling relationship between the shell’s proper length ℓ and its thickness across all three gravity models. The observed positive correlation exhibits several key features: Linear dependence of ℓ on in the model, mild nonlinearity emerging in the case, and distinct power-law behavior for

- (3)

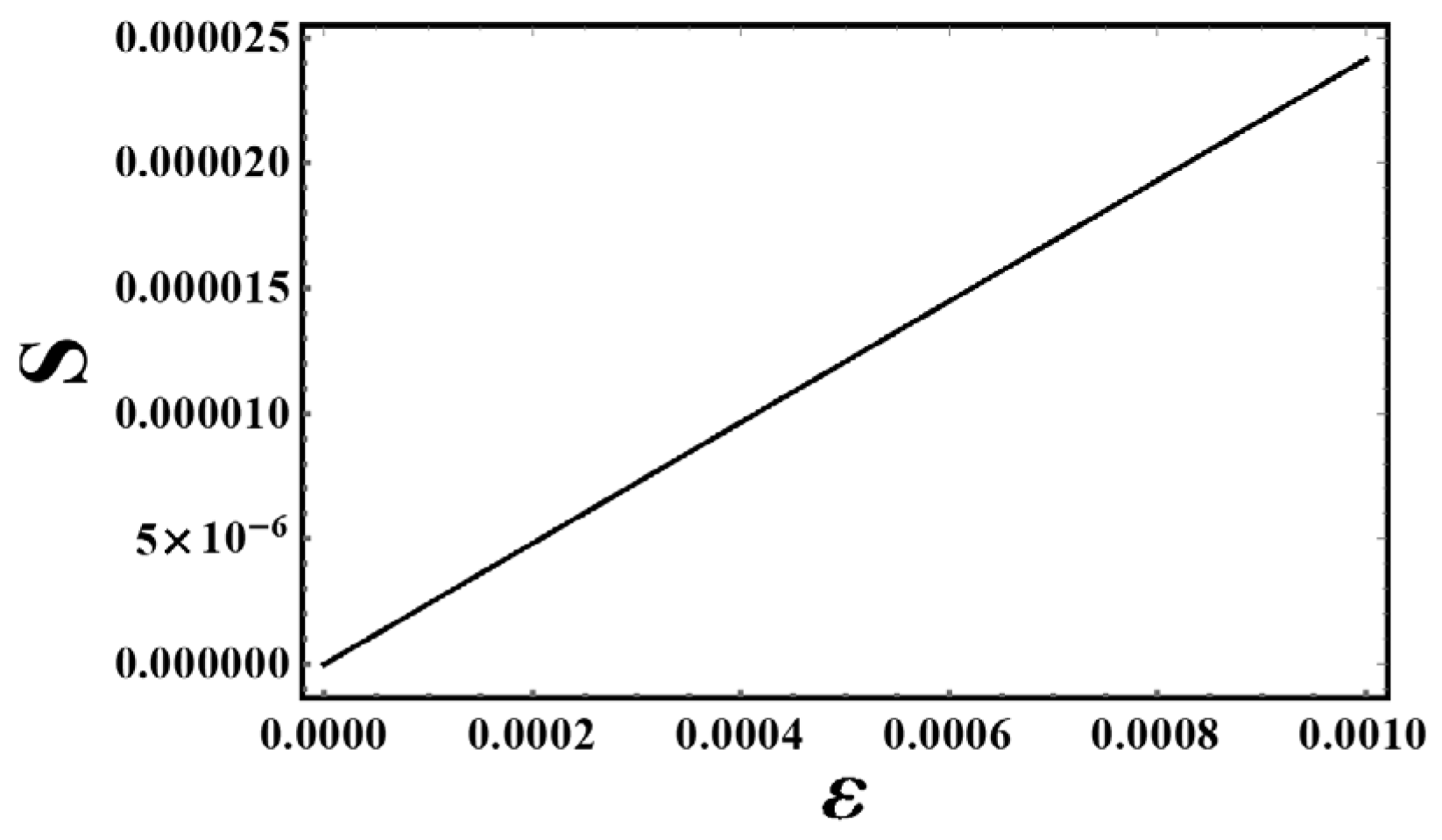

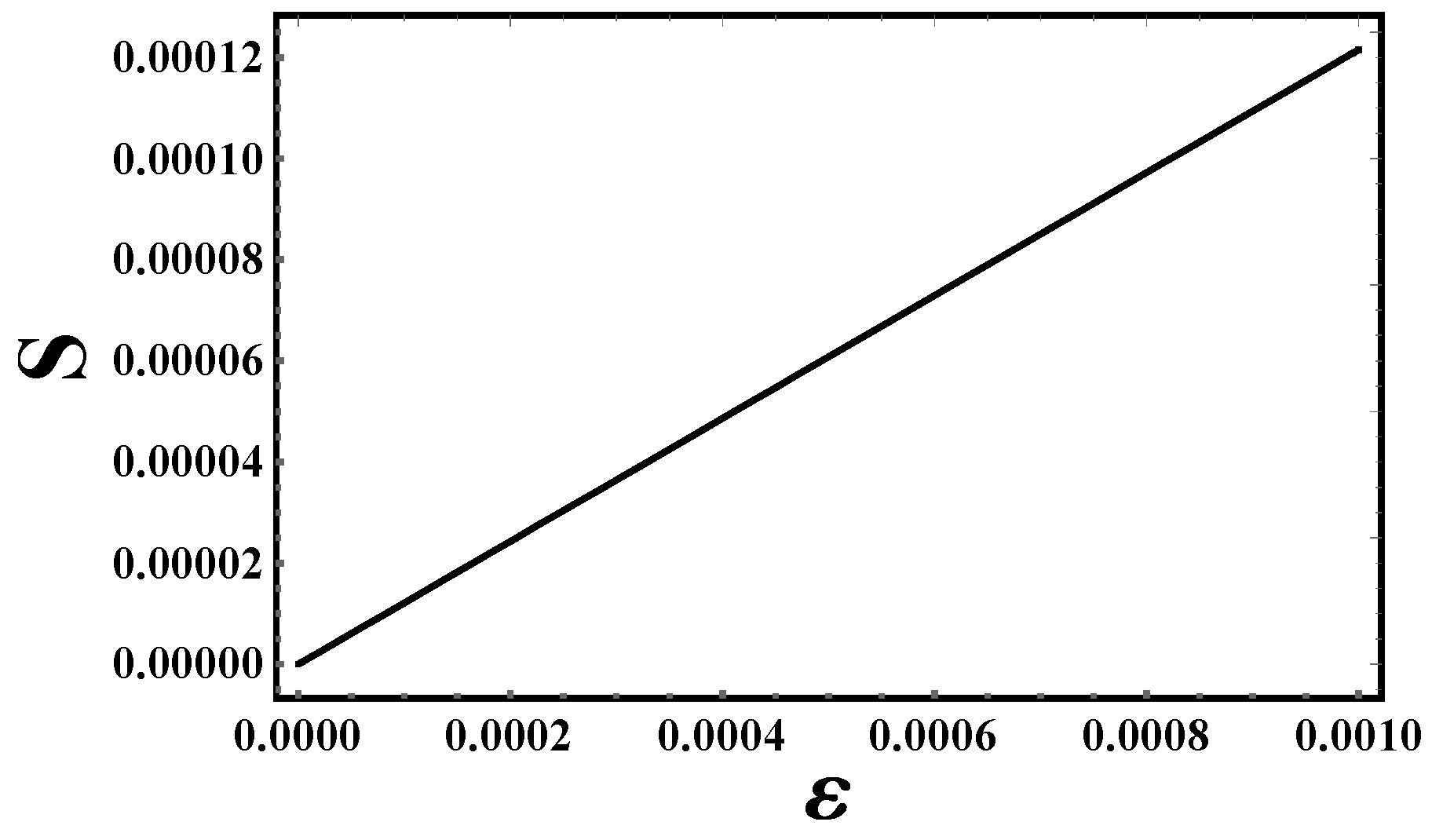

- Entropy: Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7 provide a comprehensive analysis of thermodynamic disorder in CGMs based on shell thickness ϵ\epsilonϵ across three gravitational models. It is important to note that the entropy of CGMs becomes zero when there is no shell thickness. As the shell thickness increases, the system’s complexity rises, promoting better energy distribution and leading to a greater degree of disorder. Consequently, this rise in disorder correlates with an increase in entropy. These findings underscore the intricate interplay between shell thickness and the thermodynamic properties of CGMs, highlighting how structural variations influence the overall behavior of these exotic cosmic entities.

- (4)

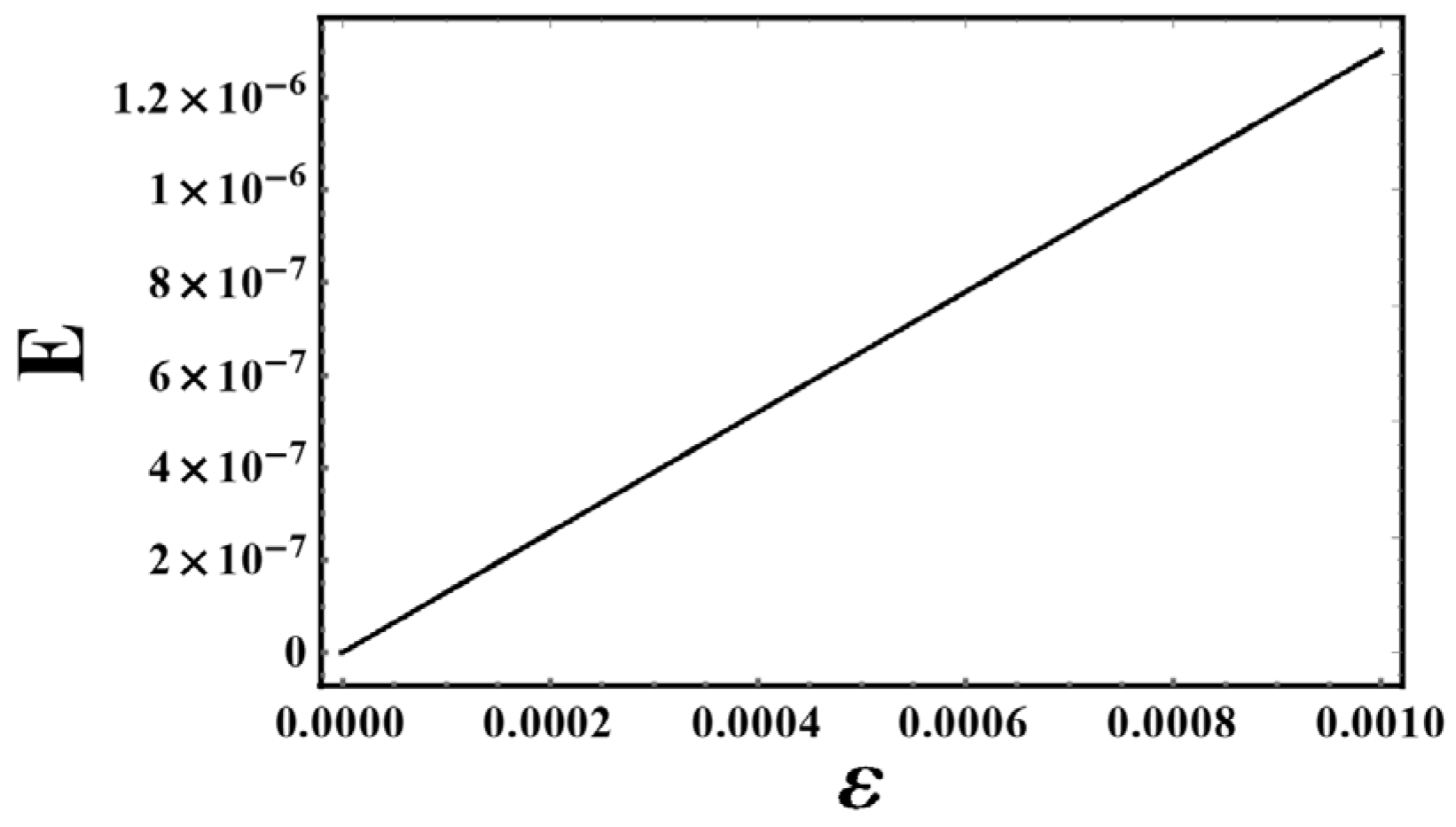

- Energy content: Figure 8 establishes a fundamental scaling relation between the shell’s internal energy E and its thickness that holds consistently across all three f(T) gravity models. The analysis reveals: Linear energy-thickness dependence: E ∝ .

- (5)

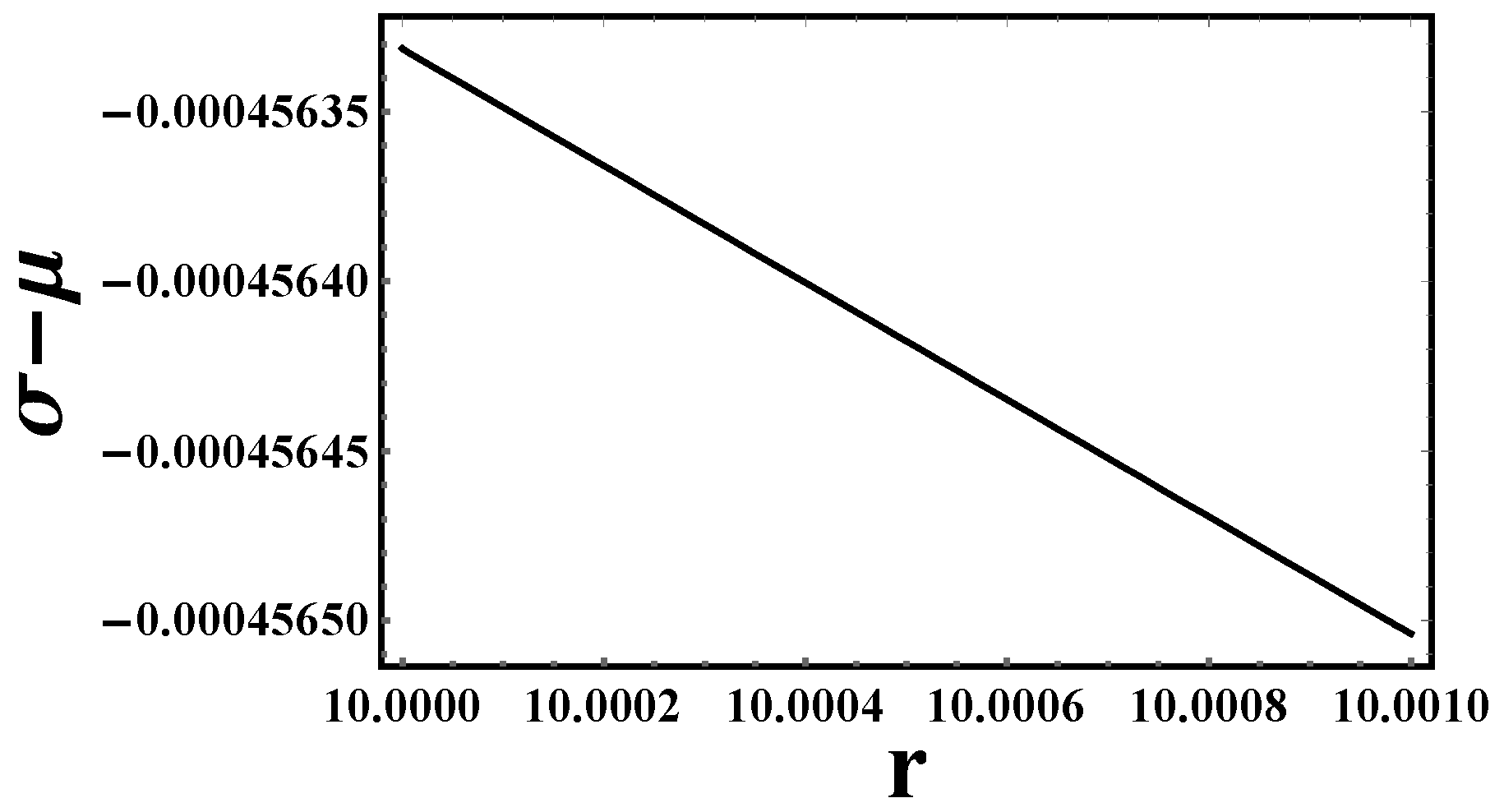

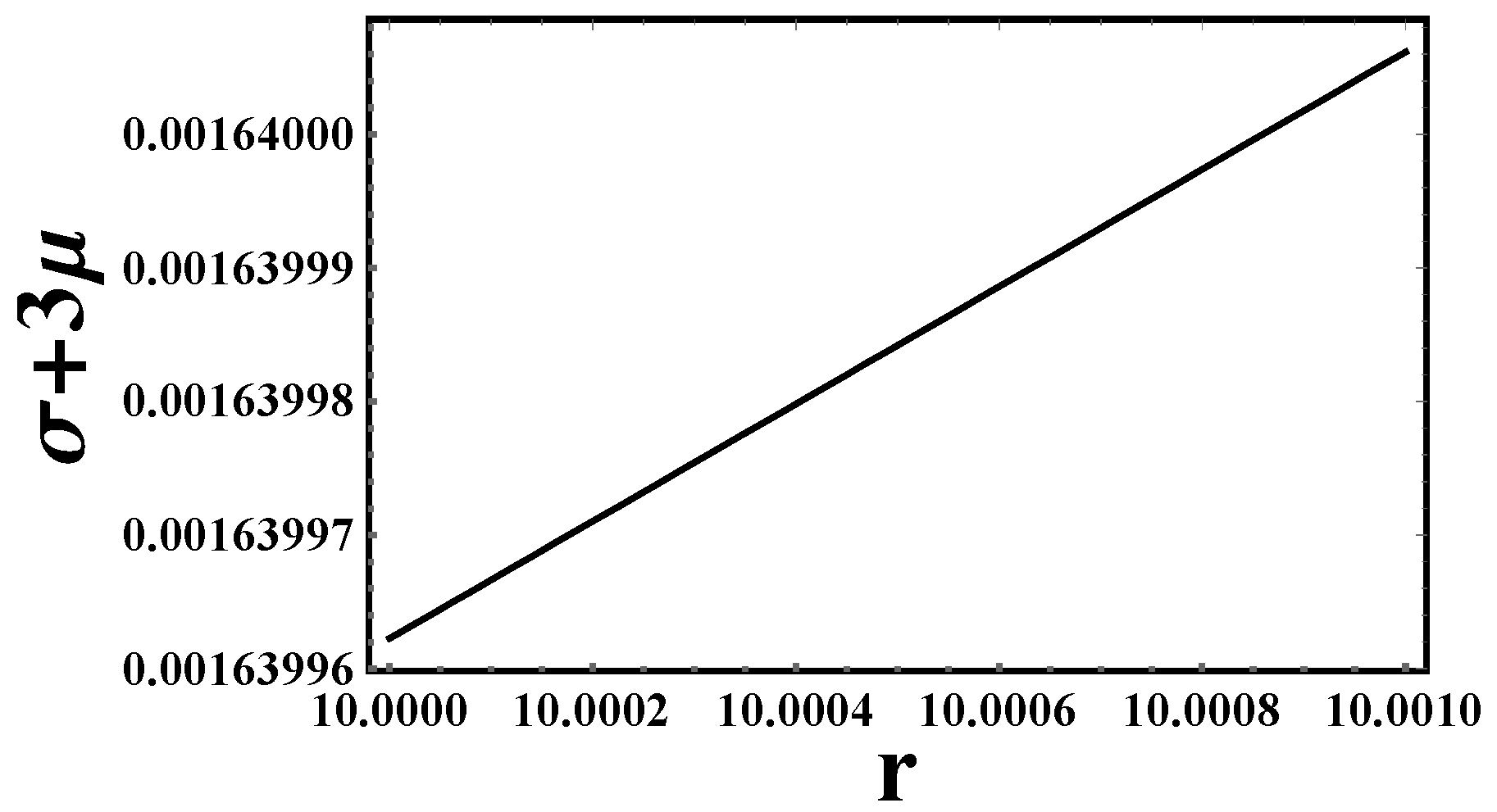

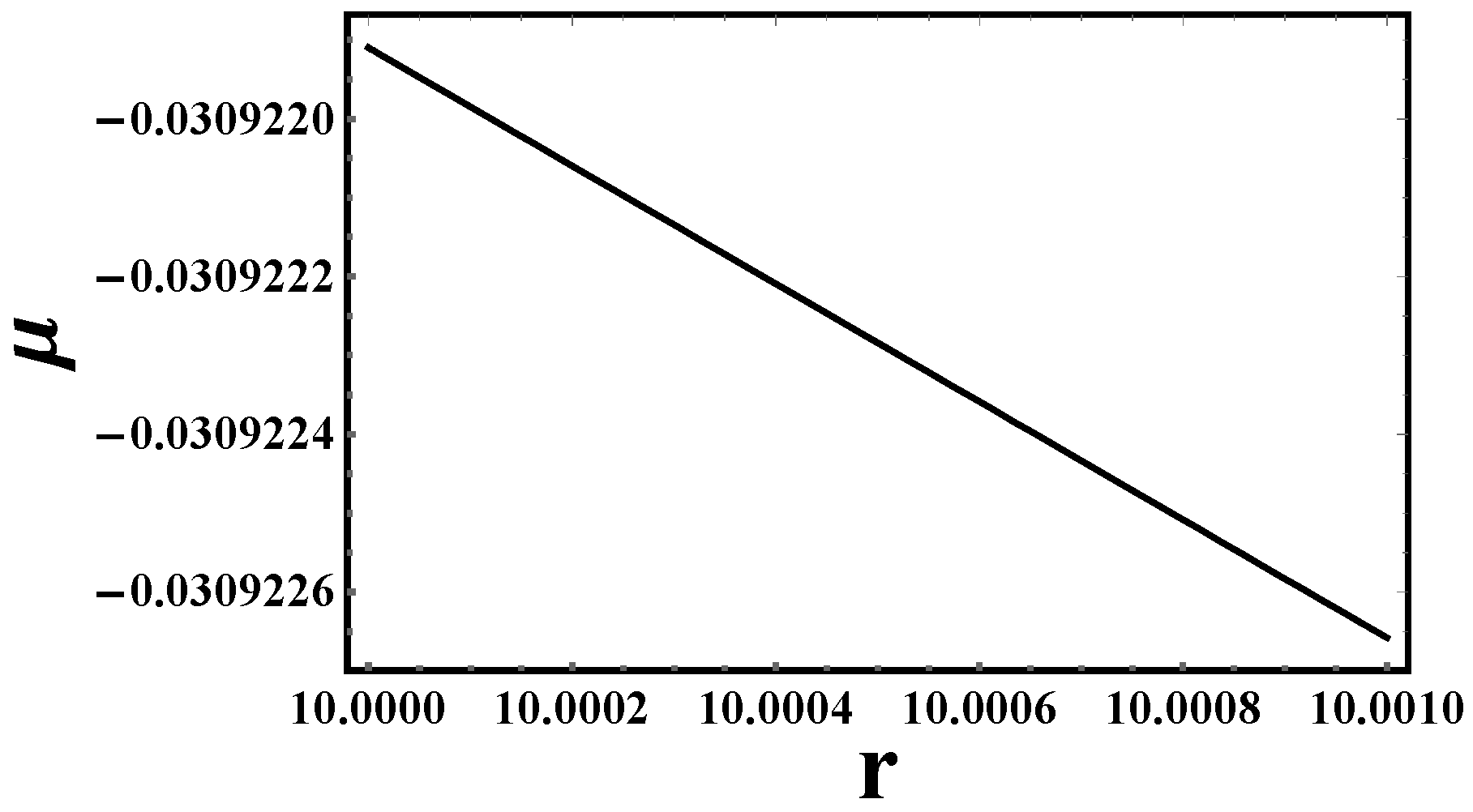

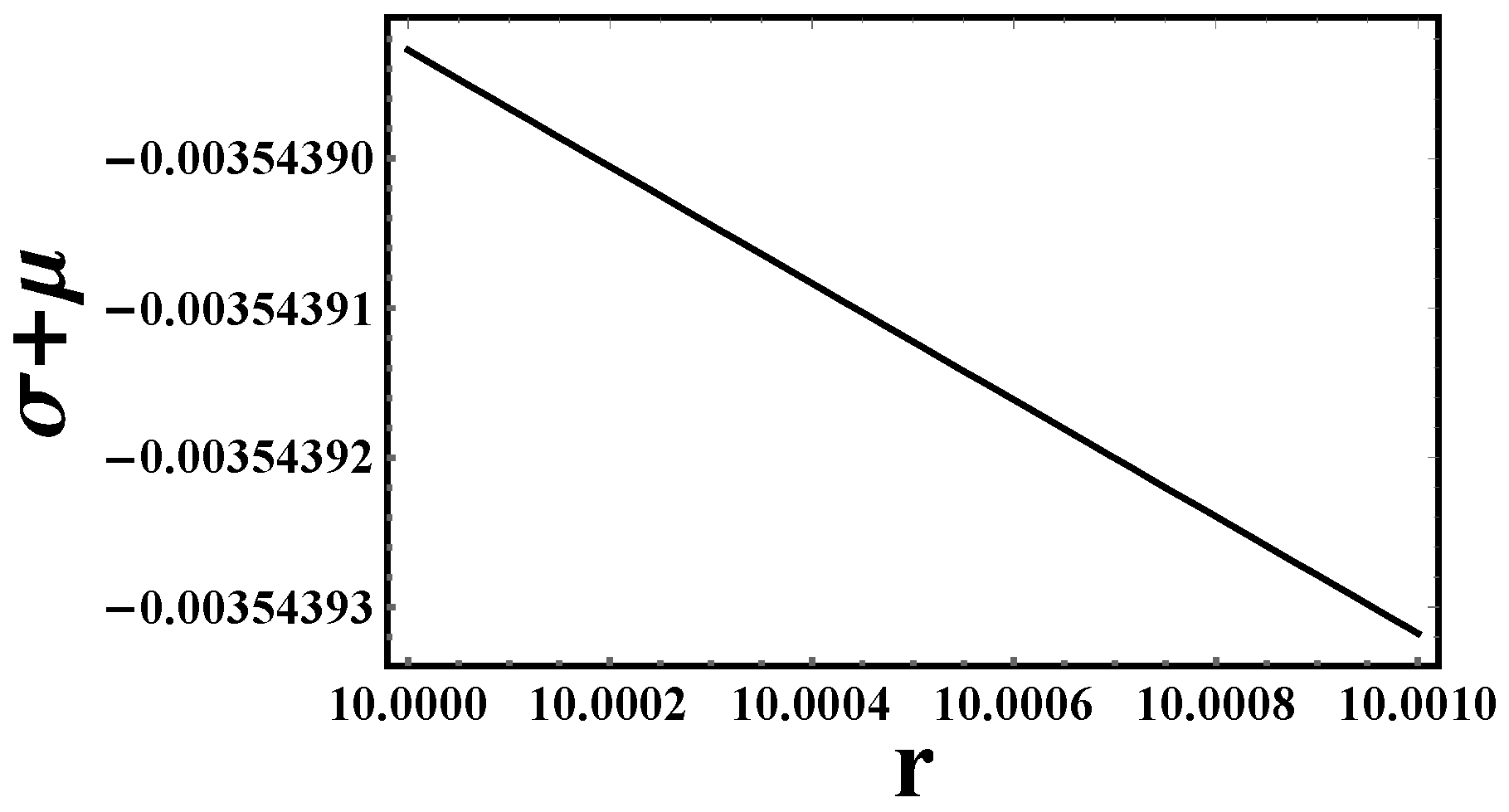

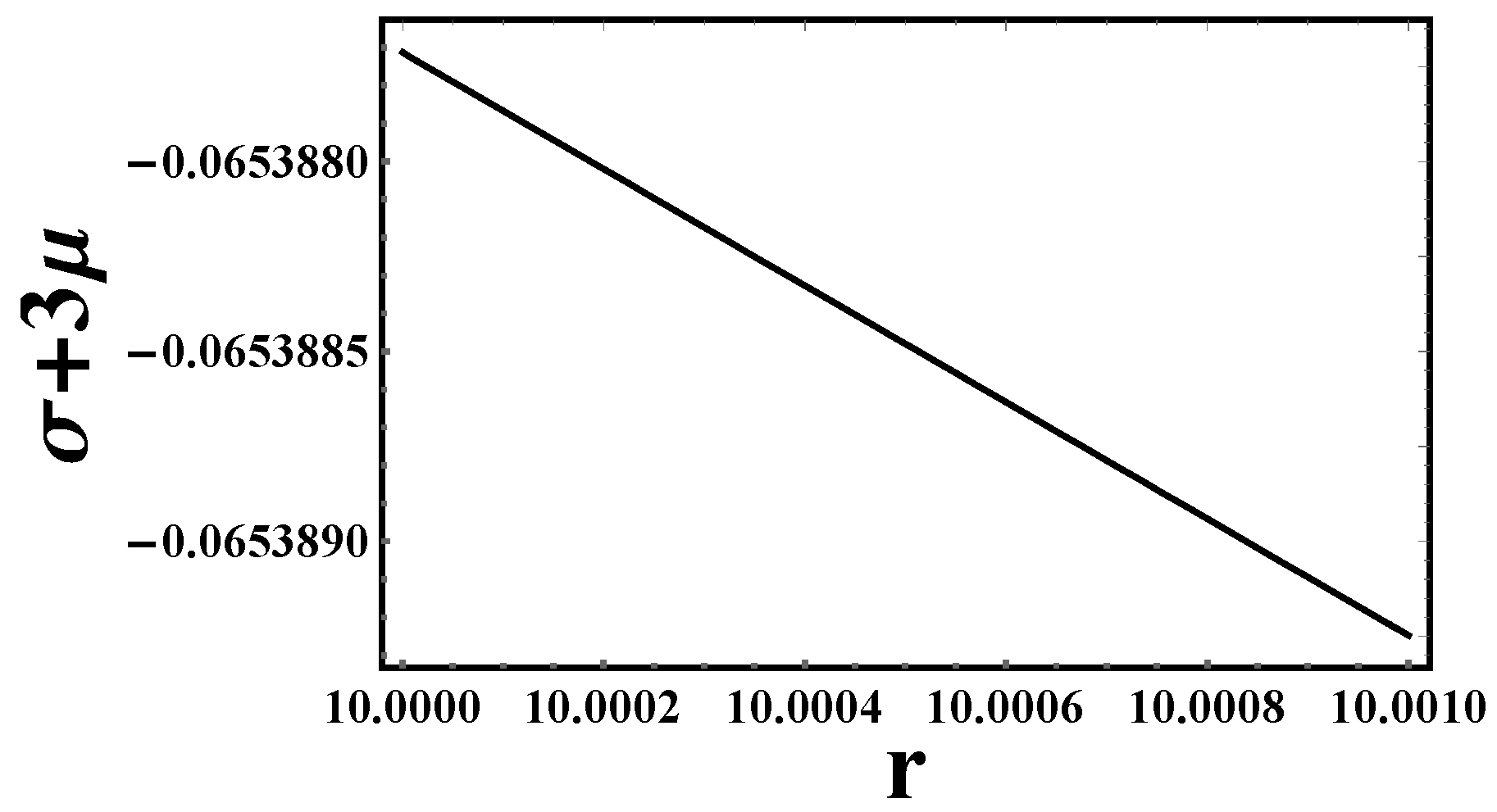

- Energy conditions: Let us discuss the energy conditions for the previous models in Table 4,

6.1. Partial Energy Condition Compliance

- -

- Gravastars require non-singular, ultra-compact solutions where the interior violates some energy conditions (e.g., DEC) but retains stability.

- -

- The f(T) = T model satisfies WEC, SEC, and NEC (unlike the other two models), which aligns with gravastar stability criteria.

- -

- The DEC violation matches expectations for gravastars, as they often involve exotic vacuum energy or anisotropic pressures at the shell.

6.2. Physical Plausibility

- -

- The f(T) = a + bT and f(T) = T2 models fail all energy conditions, making them too extreme for gravastar modeling (likely unstable or requiring unphysical matter).

- -

- The f(T) = T case maintains minimal physicality while allowing DEC-violating effects (similar to Mazur–Mottola gravastars).

6.3. Structural Consistency

- -

- Gravastars rely on a thin-shell (ultrarelativistic fluid) separating de Sitter-like interiors from exterior Schwarzschild solutions.

- -

- model’s shell dynamics (pressure, density trends) better match gravastar expectations than the other models.

- -

- : Total energy condition violation suggests uncontrollable exotic matter, making it unsuitable for stable gravastar solutions.

- -

- : Even in the σ = μ = 0 case, the model fails all conditions, implying non-viability for gravastar construction.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mazur, P.O.; Mottola, E. Gravitational condensate stars: An alternative to black holes. Universe 2023, 9, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur, P.O.; Mottola, E. Gravitational vacuum condensate stars. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 9545–9550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeBenedictis, A.; Horvat, D.; Ilijić, S.; Kloster, S.; Viswanathan, K.S. Gravastar solutions with continuous pressures and equation of state. Class. Quantum Gravity 2006, 23, 2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilic, N.; Tupper, G.B.; Viollier, R.D. Born Infeld phantom gravastars. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2006, 2006, 013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, F.; Chakraborty, S.; Ray, S.; Usmani, A.A.; Islam, S. The higher dimensional gravastars. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 2015, 54, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhar, P. Higher dimensional charged gravastar admitting conformal motion. Astrophys. Space Sci. 2014, 354, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Rahaman, F.; Guha, B.K.; Ray, S. Charged gravastars in higher dimensions. Phys. Lett. B 2017, 767, 380–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Ray, S.; Rahaman, F.; Guha, B.K. Gravastars with higher dimensional spacetimes. Ann. Phys. 2018, 394, 230–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattoen, C.; Faber, T.; Visser, M. Gravastars must have anisotropic pressures. Class. Quantum Gravity 2005, 22, 4189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usmani, A.A.; Rahaman, F.; Ray, S.; Nandi, K.K.; Kuhfittig, P.K.; Rakib, S.A.; Hasan, Z. Charged gravastars admitting conformal motion. Phys. Lett. B 2011, 701, 388–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Rahaman, F.; Islam, S.; Govender, M. Braneworld gravastars admitting conformal motion. Eur. Phys. J. C 2016, 76, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvat, D.; Ilijic, S.; Marunovic, A. Electrically charged gravastar configurations. Class. Quantum Gravity 2008, 26, 025003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, R.; da Silva, M.F.A. How the charge can affect the formation of gravastars. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2010, 2010, 029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, F.; Usmani, A.A.; Ray, S.; Islam, S. The (2+ 1)-dimensional charged gravastars. Phys. Lett. B 2012, 717, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, C.F.C.; Chan, R.; da Silva, M.F.A.; Rocha, P. Charged gravastar in a dark energy universe. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1309.2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovgun, A.; Banerjee, A.; Jusufi, K. Charged thin-shell gravastars in noncommutative geometry. Eur. Phys. J. C 2017, 77, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, B.M.N. Stable gravastars with generalized exteriors. Class. Quantum Gravity 2005, 22, 4551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, P.; Miguelote, A.Y.; Chan, R.; Da Silva, M.F.; Santos, N.O.; Wang, A. Bounded excursion stable gravastars and black holes. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2008, 2008, 025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, P.; Chan, R.; da Silva, M.F.A.; Wang, A. Stable and ‘bounded excursion’gravastars, and black holes in Einstein’s theory ofgravity. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2008, 2008, 010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, R.; Da Silva, M.F.A.; Rocha, P. Gravastars and black holes of anisotropic dark energy. Gen. Relati. Gravi. 2011, 43, 2223–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Villanueva, J.R.; Channuie, P.; Jusuf, K. Stable Gravastars: Guilfoyle’s electrically charged solutions. Chin. Phys. C 2018, 42, 115101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nojiri, S.; Odintsov, S.D. Introduction to modified gravity and gravitational alternative for dark energy. Int. J. Geom. Methods Mod. Phys. 2007, 4, 115–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capozziello, S.; Francaviglia, M. Extended theories of gravity and their cosmological and astrophysical applications. Gen. Relativ. Gravit. 2008, 40, 357–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotiriou, T.P.; Faraoni, V. f(R) theories of gravity. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2010, 82, 451–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Felice, A.; Tsujikawa, S. f(R) theories. Living Rev. Relativ. 2010, 13, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harko, T.; Lobo, F.S.; Nojiri, S.I.; Odintsov, S.D. f(R,T) gravity. Phys. Rev. D 2011, 84, 024020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, M.; Asad, H. Impact of modified Chaplygin gas on electrically charged thin-shell wormhole models. Phys. Dark Univ. 2025, 48, 101841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, M.; Wiltshire, D. Stable gravastars an alternative to black holes? Class. Quantum Grav. 2004, 21, 1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, B. Frozen rigging model of the energy dominated universe. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 2005, 44, 1729–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chirenti, C.; Rezzolla, L. Ergoregion instability in rotating gravastars. Phys. Rev. D 2008, 78, 084011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pani, P.; Berti, E.; Cardoso, V.; Chen, Y.; Norte, R. Gravitational wave signatures of the absence of an event horizon: Nonradial oscillations of a thin-shell gravastar. Phys. Rev. D 2009, 80, 124047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, V.; Pani, P. Tests for the existence of black holes through gravitational wave echoes. Nature Astro. 2017, 1, 586–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramowicz, M.; Fragile, P.C. Foundations of black hole accretion disk theory. Liv. Rev. Relat. 2013, 16, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobo, F.S.; Arellano, A.V. Gravastars supported by nonlinear electrodynamics. Class. Quantum Grav. 2007, 24, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jampolski, D.; Rezzolla, L. Nested solutions of gravitational condensate stars. Class. Quant. Grav. 2024, 41, 065014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houndjo, M.J.S. Reconstruction of f(R,T) gravity describing matter dominated and accelerated phases. J. Mod. Phys. D 2012, 21, 1250003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, M.; Waseem, A. Anisotropic quark stars in f(R,T) gravity. Eur. Phys. J. C 2018, 78, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A. Riemannian geometry with maintaining the notion of distant parallelism. Sitz. Preuss. Akad. Wiss. 1928, 217, 224. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Y.F.; Capozziello, S.; De Laurentis, M.; Saridakis, E.N. f(T) teleparallel gravity and cosmology. Repor. Prog. Phys. 2016, 79, 106901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A. Auf die riemann-metrik und den fern-parallelismus gegründete einheitliche feldtheorie. Math. Ann. 1930, 102, 685–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unzicker, A.; Case, T. Translation of Einstein’s attempt of a unified field theory with teleparallelism. arXiv 2005, arXiv:physics/0503046. [Google Scholar]

- De Andrade, V.C.; Guillen, L.C.T.; Pereira, J.G. Gravitational energy-momentum density in teleparallel gravity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000, 84, 4533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bengochea, G.R.; Ferraro, R. Dark torsion as the cosmic speed-up. Phys. Rev. D- Part. Fiel. Grav. Cos. 2009, 79, 124019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T. Static solutions with spherical symmetry in f(T) theories. Phys. Rev. D 2011, 84, 024042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dent, J.B.; Dutta, S.; Saridakis, E.N. f(T) gravity mimicking dynamical dark energy. Background and perturbation analysis. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2011, 2011, 009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakry, M.A.; Ibraheem, S.K. Gravity. Grav. Cos. 2023, 29, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakry, M.A.; Moatimid, G.M.; Shafeek, A.T. Charged gravastar in f(R,Σ,T)-gravity. Mod. Phys Lett. A 2024, 39, 2450166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafeek, A.T.; Bakry, M.A.; Moatimid, G.M. Gravastars in f(R,Σ,T) strong-gravity and antigravity theories. Pramana 2023, 97, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakry, M.A.; Alkaoud, A.; Eid, A.; Khader, M.M. LRS Bianchi type I with anisotropic bulk viscosity matter cosmological typical and quadratic deceleration parameter in f(R,Σ,T) gravity. Indian J. Phys. 2024, 98, 3033–3042. [Google Scholar]

- Myrzakulov, N.; Shekh, S.H.; Pradhan, A. Cosmological implications of f(R,Σ,T) gravity: A unified approach using OHD and SN ia data. Phys. Lett. B 2025, 862, 139369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, S.; Sultan, M.D.; Ashraf, A.; Alanazi, Y.M.; Abidi, A.; Mubaraki, A.M. Analysis of Hawking evaporation, shadows, and thermodynamic geometry of black holes within the Einstein SU (N) non-linear sigma model. J. High Energy Astrophys. 2025, 45, 463–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekh, S.H.; Yadav, A.K.; Pradhan, A.; Myrzakulov, N. Cosmological Analysis of f(R,Σ,T) Gravity via Om(z) Reconstruction: Implications into Dark Energy Dynamics. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.13446. [Google Scholar]

- Myrzakulov, N.; Pradhan, A.; Dixit, A.; Shekh, S.H. Exploring Phase Space Trajectories in ΛCDM Cosmology with f(G) Gravity Modifications. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.16304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, G.; Javed, F.; Maurya, S.K.; Waseem, A.; Fatima, G. Imprints of dark energy models on structural properties of charged gravastars in extended teleparallel gravity. Phys. Dark Universe 2024, 46, 101574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, M.; Singh, S.S. Strange quark stars in mimetic gravitational theory. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.10583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanas, M.I.; Nabil, L.Y.; Sid-Ahmed, A.M. Teleparallel Lagrange geometry and a unified field theory. Class. Quan. Grav. 2010, 27, 045005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Sotiriou, T.P.; Barrow, J.D. Large-scale structure in f(T) gravity. Phys. Rev. D Part., Fiel., Grav. Cos. 2011, 83, 104017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Ghosh, S.; Deb, D.; Rahaman, F.; Ray, S. Study of gravastars under f(T) gravity. Nuc. Phys. B 2020, 954, 114986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capozziello, S.; D’Agostino, R.; Luongo, O. Model-independent reconstruction of f(T) teleparallel cosmology. Gen. Relat. Grav. 2017, 49, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrovandi, R.; Pereira, J.G. Teleparallel Gravity: An Introduction; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; Volume 173, p. 87. [Google Scholar]

- Capozziello, S.; Stornaiolo, C. Torsion tensor and its geometric interpretation. Fond. Louis Broglie 2007, 32, 195. [Google Scholar]

- Toptygin, I.N.; Levina, K. Energy–momentum tensor of the electromagnetic field in dispersive media. Physics-Uspekhi 2016, 59, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panat, P.V. Contributions of Maxwell to electromagnetism. Resonance 2003, 8, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhmer, C.G.; Mussa, A.; Tamanini, N. Existence of relativistic stars in f(T) gravity. Class. Quantum Gravity 2011, 28, 245020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Ghosh, S.; Guha, B.K.; Das, S.; Rahaman, F.; Ray, S. Gravastars in f(R,T) gravity. Phys. Rev. D 2017, 95, 124011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, L.; Ponce de Leon, J. Anisotropic spheres admitting a one-parameter group of conformal motions. J. Math. Phys. 1985, 26, 2018–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, M.Z.; Yousaf, Z.; Rehman, A. Gravastars in f(R,G) gravity. Phys. Dark Univ. 2020, 29, 100561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, R.; Edgar, S.B.; Barnes, A. Killing tensors and conformal Killing tensors from conformal Killing vectors. Class. Quan. Grav. 2003, 20, 1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehmer, C.G.; Harko, T.; Lobo, F.S. Wormhole geometries in modified teleparallel gravity and the energy conditions. Phys. Rev. D Part., Fiel. Gravi. Cos. 2012, 85, 044033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, G.; Zubair, M.; Mustafa, G. Anisotropic strange quintessence stars in f(R) gravity. Astro. Space Sci. 2015, 358, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, U. Charge gravastars in f(T) modified gravity. Eur. Phys. J. C 2019, 79, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.F.; Gong, J.O.; Wang, D.G.; Wang, Z. Features from the non-attractor beginning of inflation. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2016, 2016, 017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatsymovsky, V.M. On the discrete version of the Reissner–Nordström solution. Inter. J. Mod. Phys. A 2022, 37, 2250064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, Z.; Bamba, K.; Bhatti, M.Z.; Ghafoor, U. Charged gravastars in modified gravity. Phys. Rev. D 2019, 100, 024062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Chattopadhyay, S. Realistic compact objects in the f (R, T) gravity in the background of polytropic and barotropic gas models. Phys. Scrip. 2024, 99, 055020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekenstein, J.D. Black holes and entropy. Phys. Rev. D 1973, 7, 2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eling, C.; Foster, B.Z.; Jacobson, T.; Wall, A.C. Lorentz violation and perpetual motion. Phys. Rev. D- Part. Fiel. Grav. Cos. 2007, 75, 101502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanczos, K. Flächenhafte verteilung der materie in der einsteinschen gravitationstheorie. Ann. Der Phys. 1924, 379, 518–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.-Y.; Zhang, M.; Zou, D.-C.; Lai, M.-Y. Analytical Approximations to Charged Black Hole Solutions in Einstein–Maxwell–Weyl Gravity. Universe 2023, 9, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dymnikova, I.; Galaktionov, E. Generic behavior of electromagnetic fields of regular rotating electrically charged compact objects in nonlinear electrodynamics minimally coupled to gravity. Symmetry 2023, 15, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dymnikova, I. Density and Mass Function for Regular Rotating Electrically Charged Compact Objects Determined by Nonlinear Electrodynamics Minimally Coupled to Gravity. Particles 2023, 6, 647–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffini, R.; Bonazzola, S. Systems of self-gravitating particles in general relativity and the concept of an equation of state. Phys. Rev. 1969, 187, 1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khlopov, M.Y.; Malomed, B.A.; Zeldovich, Y.B. Gravitational instability of scalar fields and formation of primordial black holes. Mont. Not. Roy. Astro. Soci. 1985, 215, 575–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, M.; Grasso, D.; Ruffini, R. Jeans mass of a cosmological coherent scalar field. Astro. Astrophys. 1990, 231, 301–308. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb, E.W.; Tkachev, I.I. Axion miniclusters and Bose stars. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1993, 71, 3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dymnikova, I. Vacuum nonsingular black hole. Gen. relat. Gravi. 1992, 24, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dymnikova, I.; Khlopov, M. Regular black hole remnants and graviatoms with de Sitter interior as heavy dark matter candidates probing inhomogeneity of early universe. Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 2015, 24, 1545002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | Ref. | The Proper Length of the Thin Shell | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Equation (85) | |||

| Equation (92) | |||

| Equation (97) |

| Model | The Entropy of the Thin Shell | |

|---|---|---|

| Model | Interior Region | Exterior Region |

|---|---|---|

| Model | Energy Conditions | Physical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| WEC, SEC, NEC: Satisfied DEC: Violated | Generally physically plausible except for energy flow restrictions. Possible superluminal energy transport. | |

| All conditions DEC/WEC/SEC/NEC: Violated | Non-standard energy-momentum tensor. Likely requires exotic matter (e.g., phantom fields). | |

| All conditions DEC/WEC/SEC/NEC: Violated. Special case: σ = μ = 0 | Strong spacetime geometry effects. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bakry, M.A.; Eid, A. Models of Charged Gravastars in f(T)-Gravity. Universe 2025, 11, 353. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe11100353

Bakry MA, Eid A. Models of Charged Gravastars in f(T)-Gravity. Universe. 2025; 11(10):353. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe11100353

Chicago/Turabian StyleBakry, Mohamed A., and Ali Eid. 2025. "Models of Charged Gravastars in f(T)-Gravity" Universe 11, no. 10: 353. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe11100353

APA StyleBakry, M. A., & Eid, A. (2025). Models of Charged Gravastars in f(T)-Gravity. Universe, 11(10), 353. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe11100353