New Horizons in Quality Control of Enzyme Pharmaceuticals: Combining Dynamic Light Scattering, Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy, and Radiothermal Emission Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

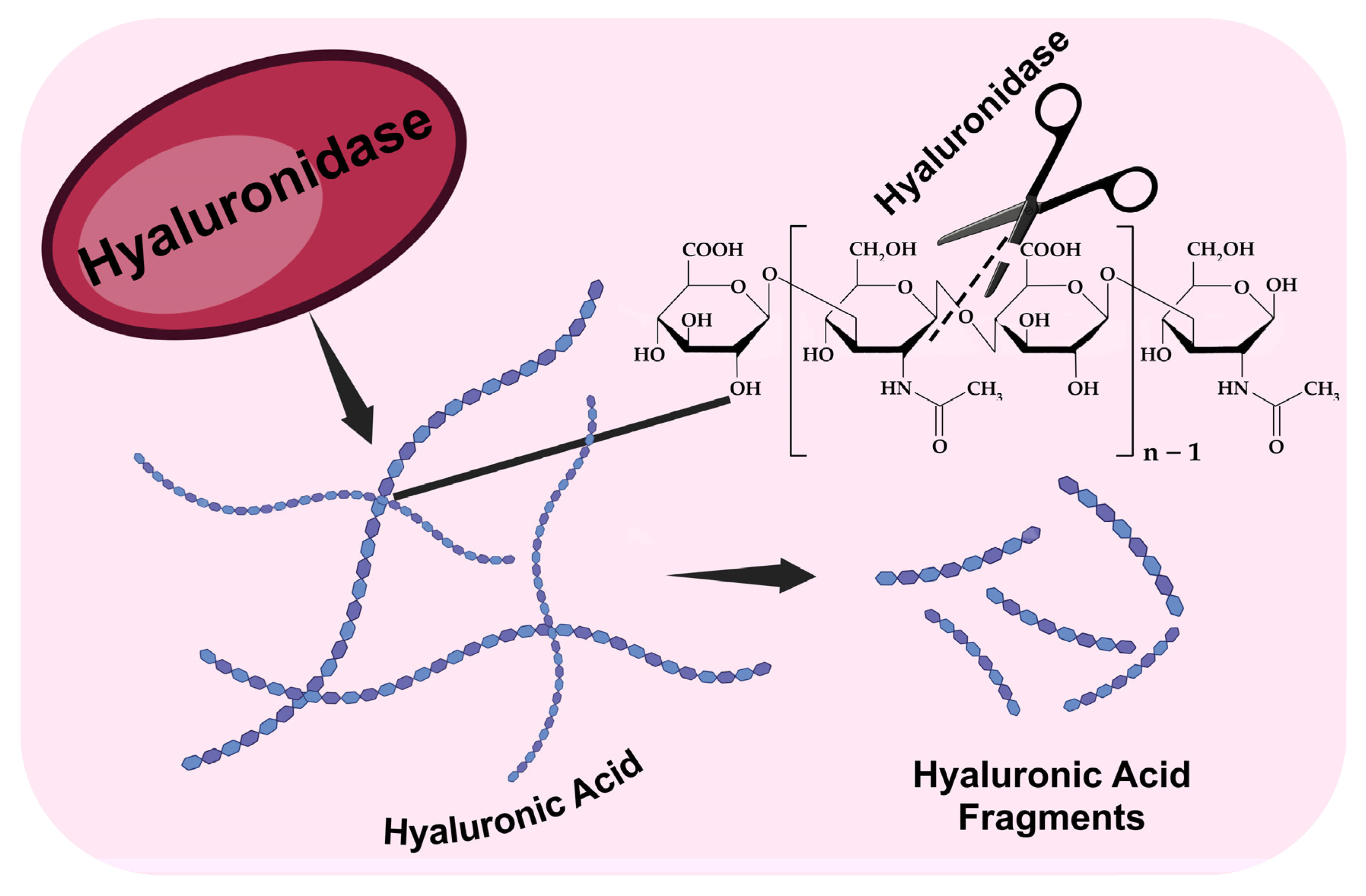

1.1. Structure, Biochemistry, and Physiological Role of Hyaluronic Acid: A Bridge Between Health and Disease

1.2. Contemporary Biopharmaceuticals Based on Hyaluronidase

1.3. Quality Control of Hyaluronidase Pharmaceuticals: Contemporary Approaches and Challenges

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Pharmaceuticals Based on Hyaluronidase

- A drug containing hyaluronidase, registration number: LP-(006291)-(RG-RU), (LLC “Samson-Med”, Saint-Petersburg, Russia), which is a lyophilizate for preparing solutions for injection and topical application, with a dosage of 1280 IU.

- A hyaluronidase-based drug, registration number: LP-(000276)-(RG-RU), (JSC “NPO Microgen”, Moscow, Russia), which is a lyophilizate for preparing solutions for injection and topical application, with a dosage of 1280 IU.

- A drug based on azoximer-conjugated hyaluronidase, registration number: LP-(009351)-(RG-RU), (“NPO Petrovax Pharm LLC”, Moscow, Russia), which is a lyophilizate for preparing solutions for injection, with a dosage of 3000 IU. The finished dosage form contains the excipient mannitol—up to 20 mg.

2.2. Dynamic Light Scattering

2.3. FTIR Spectroscopy

2.4. Measurement of Intrinsic Radiothermal Emission

2.5. Statistics

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Study of the Dimensional Characteristics of Hyaluronidase Pharmaceuticals

3.2. IR Spectroscopy of Hyaluronidase Conjugated with Azoximer

3.3. Non-Invasive Control of the Quality Characteristics of Hyaluronidase Biopharmaceuticals

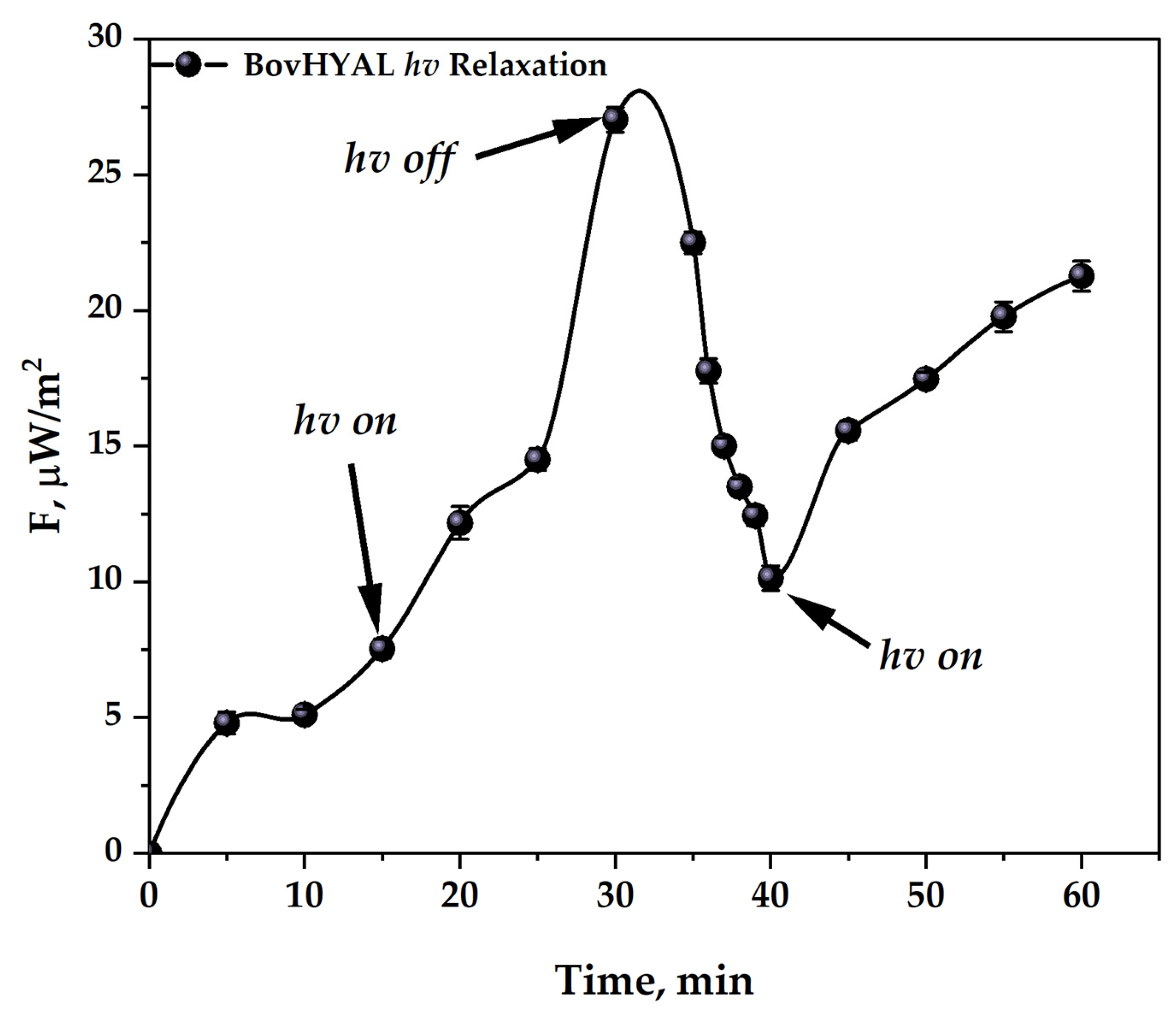

3.3.1. Development of a Methodology for Activating Hyaluronidase Samples

3.3.2. Quality Control of Hyaluronidase Pharmaceuticals

3.4. From Pharmacopeial Standards to Innovative Quality Control Strategies for Enzymatic Pharmaceuticals

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Graça, M.F.P.; Miguel, S.P.; Cabral, C.S.D.; Correia, I.J. Hyaluronic Acid—Based Wound Dressings: A Review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 241, 116364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knopf-Marques, H.; Pravda, M.; Wolfova, L.; Velebny, V.; Schaaf, P.; Vrana, N.E.; Lavalle, P. Hyaluronic Acid and Its Derivatives in Coating and Delivery Systems: Applications in Tissue Engineering, Regenerative Medicine and Immunomodulation. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2016, 5, 2841–2855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraser, J.R.E.; Laurent, T.C.; Laurent, U.B.G. Hyaluronan: Its Nature, Distribution, Functions and Turnover. J. Intern. Med. 1997, 242, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cowman, M.K.; Lee, H.-G.; Schwertfeger, K.L.; McCarthy, J.B.; Turley, E.A. The Content and Size of Hyaluronan in Biological Fluids and Tissues. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fallacara, A.; Baldini, E.; Manfredini, S.; Vertuani, S. Hyaluronic Acid in the Third Millennium. Polymers 2018, 10, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litwiniuk, M.; Krejner, A.; Speyrer, M.S.; Gauto, A.R.; Grzela, T. Hyaluronic Acid in Inflammation and Tissue Regeneration. Wounds 2016, 28, 78–88. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.; Sugihara, K.; Gillilland, M.G.; Jon, S.; Kamada, N.; Moon, J.J. Hyaluronic Acid–Bilirubin Nanomedicine for Targeted Modulation of Dysregulated Intestinal Barrier, Microbiome and Immune Responses in Colitis. Nat. Mater. 2020, 19, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Liu, G.; Liu, P.; Hu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Fang, Y.; Sun, G.; Huang, H.; Wu, J. Hyaluronic Acid-Based Glucose-Responsive Antioxidant Hydrogel Platform for Enhanced Diabetic Wound Repair. Acta Biomater. 2022, 147, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, T.; Chanmee, T.; Itano, N. Hyaluronan: Metabolism and Function. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhou, W.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, S.; Luo, X.; Stupack, D.G.; Luo, N. Role of Hyaluronan and Glucose on 4-Methylumbelliferone-Inhibited Cell Proliferation in Breast Carcinoma Cells. Anticancer Res. 2015, 35, 4799–4805. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Wu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, S.; Ding, J.; Chen, Z.; Wu, K.; Wu, X.; Zhou, T.; Zeng, M.; et al. Hyaluronan-Based Hydrogel Integrating Exosomes for Traumatic Brain Injury Repair by Promoting Angiogenesis and Neurogenesis. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 306, 120578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, D.; Liang, J.; Noble, P.W. Hyaluronan as an Immune Regulator in Human Diseases. Physiol. Rev. 2011, 91, 221–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, P.; Arif, A.A.; Lee-Sayer, S.S.M.; Dong, Y. Hyaluronan and Its Interactions With Immune Cells in the Healthy and Inflamed Lung. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Seki, E. Hyaluronan in Liver Fibrosis: Basic Mechanisms, Clinical Implications, and Therapeutic Targets. Hepatol. Commun. 2023, 7, e0083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albeiroti, S.; Soroosh, A.; de la Motte, C.A. Hyaluronan’s Role in Fibrosis: A Pathogenic Factor or a Passive Player? Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 790203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzouvelekis, A.; Harokopos, V.; Paparountas, T.; Oikonomou, N.; Chatziioannou, A.; Vilaras, G.; Tsiambas, E.; Karameris, A.; Bouros, D.; Aidinis, V. Comparative Expression Profiling in Pulmonary Fibrosis Suggests a Role of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1α in Disease Pathogenesis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2007, 176, 1108–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sime, P.J.; O’Reilly, K.M.A. Fibrosis of the Lung and Other Tissues: New Concepts in Pathogenesis and Treatment. Clin. Immunol. 2001, 99, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirawat, R.; Jain, N.; Aslam Saifi, M.; Rachamalla, M.; Godugu, C. Lung Fibrosis: Post-COVID-19 Complications and Evidences. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 116, 109418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockey, D.C.; Bell, P.D.; Hill, J.A. Fibrosis—A Common Pathway to Organ Injury and Failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 1138–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, S.; Hascall, V.C.; Markwald, R.R.; Ghatak, S. Interactions between Hyaluronan and Its Receptors (CD44, RHAMM) Regulate the Activities of Inflammation and Cancer. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, G.; Rao, K.; Chung, I.; Ha, C.-S.; An, S.; Yun, Y. Derivatization of Hyaluronan to Target Neuroblastoma and Neuroglioma Expressing CD44. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roma-Rodrigues, C.; Mendes, R.; Baptista, P.V.; Fernandes, A.R. Targeting Tumor Microenvironment for Cancer Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toole, B.P. Hyaluronan: From Extracellular Glue to Pericellular Cue. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2004, 4, 528–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heldin, P.; Basu, K.; Olofsson, B.; Porsch, H.; Kozlova, I.; Kahata, K. Deregulation of Hyaluronan Synthesis, Degradation and Binding Promotes Breast Cancer. J. Biochem. 2013, 154, 395–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugaiah, V.; Agostinis, C.; Varghese, P.M.; Belmonte, B.; Vieni, S.; Alaql, F.A.; Alrokayan, S.H.; Khan, H.A.; Kaur, A.; Roberts, T.; et al. Hyaluronic Acid Present in the Tumor Microenvironment Can Negate the Pro-Apototic Effect of a Recombinant Fragment of Human Surfactant Protein D on Breast Cancer Cells. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provenzano, P.P.; Cuevas, C.; Chang, A.E.; Goel, V.K.; Von Hoff, D.D.; Hingorani, S.R. Enzymatic Targeting of the Stroma Ablates Physical Barriers to Treatment of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell 2012, 21, 418–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobetz, M.A.; Chan, D.S.; Neesse, A.; Bapiro, T.E.; Cook, N.; Frese, K.K.; Feig, C.; Nakagawa, T.; Caldwell, M.E.; Zecchini, H.I.; et al. Hyaluronan Impairs Vascular Function and Drug Delivery in a Mouse Model of Pancreatic Cancer. Gut 2013, 62, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, F.; D’Este, M.; Vadalà, G.; Cattani, C.; Papalia, R.; Alini, M.; Denaro, V. Platelet Rich Plasma and Hyaluronic Acid Blend for the Treatment of Osteoarthritis: Rheological and Biological Evaluation. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0157048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-K.; Yu, Q.-M. Effect of Sodium Hyaluronate Combined with Rehabilitation Training on Knee Joint Injury Caused by Golf. World J. Clin. Cases 2024, 12, 4543–4549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrey, A.C.; de la Motte, C.A. Hyaluronan, a Crucial Regulator of Inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pibuel, M.A.; Poodts, D.; Díaz, M.; Hajos, S.E.; Lompardía, S.L. The Scrambled Story between Hyaluronan and Glioblastoma. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 296, 100549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bannuru, R.R.; Osani, M.C.; Vaysbrot, E.E.; Arden, N.K.; Bennell, K.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S.M.A.; Kraus, V.B.; Lohmander, L.S.; Abbott, J.H.; Bhandari, M.; et al. OARSI Guidelines for the Non-Surgical Management of Knee, Hip, and Polyarticular Osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2019, 27, 1578–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowman, S.; Awad, M.E.; Hamrick, M.W.; Hunter, M.; Fulzele, S. Recent Advances in Hyaluronic Acid Based Therapy for Osteoarthritis. Clin. Transl. Med. 2018, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buhren, B.A.; Schrumpf, H.; Hoff, N.-P.; Bölke, E.; Hilton, S.; Gerber, P.A. Hyaluronidase: From Clinical Applications to Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2016, 21, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shpilberg, O.; Jackisch, C. Subcutaneous Administration of Rituximab (MabThera) and Trastuzumab (Herceptin) Using Hyaluronidase. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 109, 1556–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, S.L.; Davies, A. Subcutaneous Rituximab with Recombinant Human Hyaluronidase in the Treatment of Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma and Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Future Oncol. 2018, 14, 1691–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belem-Gonçalves, S.; Tsan, P.; Lancelin, J.-M.; Alves, T.L.M.; Salim, V.M.; Besson, F. Interfacial Behaviour of Bovine Testis Hyaluronidase. Biochem. J. 2006, 398, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatina, A.; Trizna, E.; Kolesnikova, A.; Baidamshina, D.; Gorshkova, A.; Drucker, V.; Bogachev, M.; Kayumov, A. The Bovhyaluronidase Azoximer (Longidaza®) Disrupts Candida Albicans and Candida Albicans-Bacterial Mixed Biofilms and Increases the Efficacy of Antifungals. Medicina 2022, 58, 1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scodeller, P.; Catalano, P.N.; Salguero, N.; Duran, H.; Wolosiuk, A.; Soler-Illia, G.J.A.A. Hyaluronan Degrading Silica Nanoparticles for Skin Cancer Therapy. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 9690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwaighofer, A.; Ablasser, S.; Lux, L.; Kopp, J.; Herwig, C.; Spadiut, O.; Lendl, B.; Slouka, C. Production of Active Recombinant Hyaluronidase Inclusion Bodies from Apis Mellifera in E. Coli Bl21(DE3) and Characterization by FT-IR Spectroscopy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, B.d.C.; Mello, M.L.S. FT-IR Microspectroscopy of Rat Ear Cartilage. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0151989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazarov, A.A.; Ledenev, O.V.; Petrov, G.V.; Levitskaya, O.V.; Syroeshkin, A.V. New Method of Quality and Quantity Control of the Insulin Glulisine Pharmaceuticals Based on Intrinsic Radiothermal Emission. J. Drug Deliv. Ther. 2025, 15, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, G.V.; Galkina, D.A.; Koldina, A.M.; Grebennikova, T.V.; Eliseeva, O.V.; Chernoryzh, Y.Y.; Lebedeva, V.V.; Syroeshkin, A.V. Controlling the Quality of Nanodrugs According to Their New Property—Radiothermal Emission. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morozova, M.A.; Koldina, A.M.; Maksimova, T.V.; Marukhlenko, A.V.; Zlatsky, I.A.; Syroeshkin, A.V. Slow Quasikinetic Changes in Water-Lactose Complexes During Storage. Int. J. Appl. Pharm. 2021, 13, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, G.C.; Buhren, B.A.; Schrumpf, H.; Wohlrab, J.; Gerber, P.A. Clinical Applications of Hyaluronidase. In Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer: Singapore, 2019; Volume 1148, pp. 255–277. [Google Scholar]

- Bordon, K.C.F.; Wiezel, G.A.; Amorim, F.G.; Arantes, E.C. Arthropod Venom Hyaluronidases: Biochemical Properties and Potential Applications in Medicine and Biotechnology. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 2015, 21, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Titenok, K.V. Methods for The Synthesis of Poly-1,4-Ethylene Piperazine, A Copolymer of 1,4-Ethylene Piperazine N-Oxide and (N-Carboxymethyl)-1,4-Ethylene Piperazine Bromide and Their Derivatives, Products Obtained by These Methods, and the Reactor Synthesis. RU 2 776 181 C2, 14 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson, H.P. Size and Shape of Protein Molecules at the Nanometer Level Determined by Sedimentation, Gel Filtration, and Electron Microscopy. Biol. Proced. Online 2009, 11, 32–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marković-Housley, Z.; Miglierini, G.; Soldatova, L.; Rizkallah, P.J.; Müller, U.; Schirmer, T. Crystal Structure of Hyaluronidase, a Major Allergen of Bee Venom. Structure 2000, 8, 1025–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, A. Infrared Spectroscopy of Proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Bioenerg. 2007, 1767, 1073–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Weert, M.; Haris, P.I.; Hennink, W.E.; Crommelin, D.J.A. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectrometric Analysis of Protein Conformation: Effect of Sampling Method and Stress Factors. Anal. Biochem. 2001, 297, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, S.; Qi, Z.; Watts, B.; Shao, Z.; Chen, X. Structural Determination of Protein-Based Polymer Blends with a Promising Tool: Combination of FTIR and STXM Spectroscopic Imaging. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 7741–7748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.Y. Accurate Measurement of Millimeter-Wave Attenuation from 75GHz to 110GHz Using a Dual-Channel Heterodyne Receiver. Measurement 2012, 45, 1105–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, G.V.; Koldina, A.M.; Ledenev, O.V.; Tumasov, V.N.; Nazarov, A.A.; Syroeshkin, A.V. Nanoparticles and Nanomaterials: A Review from the Standpoint of Pharmacy and Medicine. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syroeshkin, A.V.; Petrov, G.V.; Taranov, V.V.; Pleteneva, T.V.; Koldina, A.M.; Gaydashev, I.A.; Kolyabina, E.S.; Galkina, D.A.; Sorokina, E.V.; Uspenskaya, E.V.; et al. Radiothermal Emission of Nanoparticles with a Complex Shape as a Tool for the Quality Control of Pharmaceuticals Containing Biologically Active Nanoparticles. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levitskaya, O.V.; Petrov, G.V.; Ledenev, O.V.; Yakunin, D.Y.; Grebennikova, T.V. Non-Destructive Remote Determination of Total Native Protein Concentration in Virus-Like Particle Vaccine Preparations. J. Drug Deliv. Ther. 2025, 15, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakhomova, A.; Pershina, O.; Bochkov, P.; Ermakova, N.; Pan, E.; Sandrikina, L.; Dagil, Y.; Kogai, L.; Grimm, W.-D.; Zhukova, M.; et al. Anti-Inflammatory and Antifibrotic Potential of Longidaze in Bleomycin-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis. Life 2023, 13, 1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arioua, A.; Shaw, D. Use of Expired Drugs: Patients Benefits versus Industry Interest. JMA J. 2024, 7, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gervais, D. Quality Control and Downstream Processing of Therapeutic Enzymes. In Therapeutic Enzymes: Function and Clinical Implications. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer: Singapore, 2019; Volume 1148, pp. 55–80. [Google Scholar]

- Kheirollahi, A.; Sadeghi, S.; Orandi, S.; Moayedi, K.; Khajeh, K.; Khoobi, M.; Golestani, A. Chondroitinase as a Therapeutic Enzyme: Prospects and Challenges. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2024, 172, 110348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariga, K.; Ji, Q.; Mori, T.; Naito, M.; Yamauchi, Y.; Abe, H.; Hill, J.P. Enzyme Nanoarchitectonics: Organization and Device Application. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 6322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, L.; Bustos, R.H.; Zapata, C.; Garcia, J.; Jauregui, E.; Ashraf, G.M. Immunogenicity in Protein and Peptide Based-Therapeutics: An Overview. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2018, 19, 958–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, M.; Nezafat, N.; Rahbar, M.R.; Negahdaripour, M.; Sabetian, S.; Morowvat, M.H.; Ghasemi, Y. Decreasing the Immunogenicity of Arginine Deiminase Enzyme via Structure-based Computational Analysis. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2019, 37, 523–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, M.H.G.; da Silva Fiúza, T.; de Morais, S.B.; Trevizani, R. Circumventing the Side Effects of L-Asparaginase. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 139, 111616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Morais, S.; De Souza, T. Human L-asparaginase: Acquiring Knowledge of Its Activation (Review). Int. J. Oncol. 2021, 58, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, K.C.R.; Homem-de-Mello, M.; Motta, J.A.; Borges, M.G.; de Abreu, J.A.C.; de Souza, P.M.; Pessoa, A.; Pappas, G.J.; de Oliveira Magalhães, P. A Structural In Silico Analysis of the Immunogenicity of L-Asparaginase from Penicillium Cerradense. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Linhardt, R.J. Lessons Learned from the Contamination of Heparin. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2009, 26, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Pharmacopoeia, 11th ed.; Council of Europe, European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines and Healthcare: Strasbourg, France, 2022; ISBN 9789287191052.

- Tindall, B.; Demircioglu, D.; Uhlig, T. Recombinant Bacterial Endotoxin Testing: A Proven Solution. Biotechniques 2021, 70, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, J.S. Large-Scale High-Performance Liquid Chromatography of Enzymes for Food Applications. J. Chromatogr. A 1997, 760, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Börner, T.; Grey, C.; Adlercreutz, P. Generic HPLC Platform for Automated Enzyme Reaction Monitoring: Advancing the Assay Toolbox for Transaminases and Other PLP-dependent Enzymes. Biotechnol. J. 2016, 11, 1025–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, Y.; Thibodeaux, C.J. A Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry (HDX-MS) Platform for Investigating Peptide Biosynthetic Enzymes. J. Vis. Exp. 2020, 159, e61053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, C.; Zha, W.; Dong, S.; Xing, H.; Li, X. Multifunctional Lipid Nanoparticles for Protein Kinase N3 ShRNA Delivery and Prostate Cancer Therapy. Mol. Pharm. 2022, 19, 4588–4600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stetefeld, J.; McKenna, S.A.; Patel, T.R. Dynamic Light Scattering: A Practical Guide and Applications in Biomedical Sciences. Biophys. Rev. 2016, 8, 409–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Hyaluronidase | Azoximer-Conjugated Hyaluronidase |

|---|---|---|

| Dosage form | Lyophilizate | Lyophilizate and suppositories |

| Dosage | 1280 IU | 3000, 1500 IU |

| Half-life | Up to 48 h | Up to 84 h (suppositories), up to 45 h (lyophilizate) |

| Molecular weight | ~60–200 kDa * | ~100–180 kDa * |

| Stability | Sensitive to pH and/or T °C | Stable |

| Pharmacotherapy | Dermatology, Ophthalmology, Surgery, and Improvement of absorption of other drugs | Urology, Gynecology, Dermatology, Surgery, Pulmonology |

| Sample | Estimated Molecular Weight (M), Da | Theoretical Rmin, nm | Theoretical dmin, nm |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hyaluronidase | From 60,000 to 200,000 | From 2.6 to 3.9 | From 5.2 to 7.8 |

| Azoximer-conjugated hyaluronidase | From 100,000 to 180,000 | From 3.1 to 3.7 | From 6.2 to 7.4 |

| Wave Number, cm−1 | Type of Vibrations | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| 1464 | δ (scissors) | C-H vibrations in the CH2 group in the piperazine cycle |

| 1448 | δ (scissors) | C-H vibrations in the CH2 group in the side chain |

| 1326 | δ (twisting) | C-H vibrations in the CH2 group in the piperazine cycle |

| 1158 | ν | C-N vibrations in one of the piperazine cycles |

| 1010 | ν | C-N vibrations in one of the piperazine cycles |

| Sample | HYAL-1 | HYAL-2 | BovHYAL | Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F, μW/m2 | ||||

| In primary packaging | 7.2 ± 0.4 | 6.9 ± 0.5 | 12.1 ± 0.9 | 1.0 ± 0.2 |

| Without primary packaging | 7.3 ± 0.2 | 7.8 ± 0.3 | 15.6 ± 1.2 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Österreichische Pharmazeutische Gesellschaft. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Petrov, G.V.; Nazarov, A.A.; Koldina, A.M.; Syroeshkin, A.V. New Horizons in Quality Control of Enzyme Pharmaceuticals: Combining Dynamic Light Scattering, Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy, and Radiothermal Emission Analysis. Sci. Pharm. 2026, 94, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/scipharm94010002

Petrov GV, Nazarov AA, Koldina AM, Syroeshkin AV. New Horizons in Quality Control of Enzyme Pharmaceuticals: Combining Dynamic Light Scattering, Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy, and Radiothermal Emission Analysis. Scientia Pharmaceutica. 2026; 94(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/scipharm94010002

Chicago/Turabian StylePetrov, Gleb Vladimirovich, Aleksandr Andreevich Nazarov, Alena Mikhailovna Koldina, and Anton Vladimirovich Syroeshkin. 2026. "New Horizons in Quality Control of Enzyme Pharmaceuticals: Combining Dynamic Light Scattering, Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy, and Radiothermal Emission Analysis" Scientia Pharmaceutica 94, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/scipharm94010002

APA StylePetrov, G. V., Nazarov, A. A., Koldina, A. M., & Syroeshkin, A. V. (2026). New Horizons in Quality Control of Enzyme Pharmaceuticals: Combining Dynamic Light Scattering, Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy, and Radiothermal Emission Analysis. Scientia Pharmaceutica, 94(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/scipharm94010002