Abstract

People use social media not only for social purposes but also for business purposes. It is used in management and marketing as a tool to manage organizations and market products and services, especially to influence customers’ intention and satisfaction. Therefore, the research purpose is to define factors that influence continuous intention to use TikTok in Jordan and to what extent satisfaction with TikTok influences continuous intention to use TikTok. The current research uses a quantitative cross-sectional approach. Data was collected by online surveys and shared on several social media sites such as WhatsApp, Instagram, and Facebook. A total of 402 responses were valid for further analysis. Then, Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was performed. The results indicate that the following factors significantly affect satisfaction: self-expression, informativeness, a sense of belonging, and trendiness in TikTok. However, the following factors do not significantly affect satisfaction: sociability, affection in TikTok, and past time in TikTok. The factors can explain 48.5% of satisfaction. Finally, satisfaction has a positive significant influence on users’ continuous intention to use TikTok and can explain 30.6% of the user’s continuous intention to use TikTok. In conclusion, the organizations have to heavily use the factors that influence the users’ satisfaction to increase users’ continuous intention.

1. Introduction

The typical idea about social media, in general, is that it is affecting people negatively, but in 2016 the gratification theory focused on how an individual uses the media to satisfy their needs and satisfy themselves. Rather than claiming what media does to people, the theory discusses what people do for the media [1]. The uses and gratifications theory is utilized as a starting point for observational research that serves in getting the researchers closer to the uses and motives for using social media. Considering this theory will aid the researchers in framing and comprehending the purposes and goals of using social media, as well as introducing a set of variables that must be considered [2]. Therefore, this study investigates the social and personal needs that the Internet satisfies, establishing a typology of motives for use and examining the key variables that can predict various outcomes.

Consumers can use social networking sites (SNSs) to create personal accounts and connect with other users using the web, they are also able to upload, download, share, posts, images, and other content that is shared on their newsfeeds [3,4]. Nowadays, social networking sites (SNSs) are becoming increasingly popular.

Tiktok started with Musical.ly, which is an app that was founded by Luyu Yang and Alex Zhu in Shanghai, China in 2014 [5]. The founders of TikTok at first wanted to make an educational app, however, they started realizing that an educational app would be unprofitable and so they came up with creating Muscial.ly, which was an app that allowed users to post a video of the user lip-syncing up to 15 s to famous songs. By 2016, the application reached about 70 million downloads [6]. Additionally, in 2016, Douyin (an application that allowed short-form video sharing) was found in China. It ultimately reached East Asian countries as well and then TikTok was introduced in 2017 by ByteDance. TikTok ultimately came to the United States when it merged in 2017 with Musically for nearly USD 1 billion. Musical.ly became TikTok, however, Douyin stayed a separate app in China [7].

Since then, there have been more than 2 billion downloads of TikTok. Many famous people started using TikTok. Moreover, people have become famous through TikTok. Charlie D’Amelio is a TikTok user and began posting videos of herself dancing, and as of July 2020, she had 71 million followers on TikTok, 23 million followers on Instagram, and 3 million on Facebook [8]. The origin of the app is lip-syncing and comedy, however, it has grown to other niches such as food, business, fashion, pets, health, and even short films. Based on the above-mentioned story, the current study aims to explore the factors that affect satisfaction using TikTok and the continuous intention to use the application. This research seeks to respond to the following questions:

RQ1: What are the factors that impact continuous intention to use TikTok in Jordan?

RQ2: To what extent do these factors, past-time, affection, sense of belonging, sociability, trendiness, self-expression, and informativeness, influence satisfaction using TikTok?

To what extent does satisfaction with TikTok influence continuous intention to use TikTok?

Finally, to answer these questions, the paper starts with reviewing the previous related literature to develop hypotheses, then the materials and method used, followed by data analysis, results, and finally, the results discussion, conclusion, and proposed recommendations.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

The purpose of the current study is to explore the factors that affect satisfaction using Tiktok and the continuous intention to use the application. Hence, a revision of the existing literature regarding this topic was conducted. Most of the present related studies examined Facebook [9] and others on Instagram [10,11]. However, only one study, to the best of the authors’ knowledge was found that focused on examining customer satisfaction or behavior using TikTok. The current research model is developed according to the Uses and Gratification Theory (UGT) [12].

2.1. Social Networking Sites (SNSs)

The current research examines a person’s use of TikTok which is regarded as a social networking site (SNS). Other social network sites include Instagram, Facebook, Snapchat, LinkedIn, Messenger, Kik, and Twitter. These sites were examined by previous researchers. Social networking sites (SNSs) allow consumers to build personal profiles, express their individuality, link with other people using the site and brands, upload, comment, share, and view messages, videos, photos, and other content that is uploaded on their newsfeeds [3,4]. SNSs are becoming more pervasive in the day-to-day lives of individuals globally. The activities of social media brands nurture the user base of the brand [13] and commitment to social media brand areas increases users’ consumption expenditures [14].

Moreover, this research studies users’ usage of some of the most famous SNS platforms to satisfaction earned from utilizing them, their impact on brand community-related results, and following brands. From previously observed findings and UGT, the current research theorized that regular users of top social media platforms, such as Tiktok and Facebook, would obtain distinct gratifications from their usage (enhancing social knowledge, passing time, sharing problems, showing affection, demonstrating sociability, and the following fashion) [12]. Moreover, there are various influences on brand community-associated consequences (member intention, engagement, identification, and commitment) [15].

In addition, the correlation between brand-associated consequences and the use of SNS would additionally be facilitated by several interfering variables, such as SNS trust, network homophily, interest in social comparison, and tie strength. Generally, the research presents perceptions of the effectiveness of an SNS platform (TikTok) for marketing and its impacts on users’ perceptions of brands [15].

2.2. Social Networking Sites (SNSs) and Brands

The volume of SNSs for superior user interactivity is a great benefit of SNSs on the traditional media (which can be on TV or Radio for example). When users of SNS follow or like a brand, on their newsfeed, they will receive a notification, posts, and updates about the brand. Then the users can share, comment on, or like the posts [15].

Furthermore, brand content is conveyed in SNSs more quickly and gains additional responses compared to traditional media, but at considerably less expense [16]. E-marketers are progressively integrating SNSs as an essential component of their online brand strategy through increasing conversions for their products and brands, attracting engagement, and increasing brand awareness [17]. It is found in earlier research about SNSs raised consumer engagement with brands based on regular updates on brand pages [17,18,19], propagation of user-generated content (UGC) [20,21], membership and identification in brand communities [22], and celebrity-endorsed electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) [23,24].

Another aspect is the motives (which can be for instance promoting content) for engagement with SNS studied by [25,26,27,28] and concluded that users of SNS have a variety of motives (such as leisure and information-seeking) that affect their usage of elements within one platform of SNS as well as across various SNS platforms. Many other studies attempted to assess whether gratifications of utilizing SNSs substantially vary across five distinct SNS platforms (Tiktok, Twitter, Snapchat, Facebook, and Instagram), each with exclusive cooperative elements and methods for users to connect to and take part in branded content [15].

2.3. The Use of Media

The uses and gratification theory investigates how individuals use media to satisfy their needs. The most crucial function of media for humankind is to satisfy needs. People use media for contact, information, understanding, escape, stimulation, and interpersonal communication, as well as entertainment [29]. UGT was used in previous studies because it is the most relatable since it is a tool for finding out when and how people knowingly search out relevant media to fulfill their needs [15]. Unlike other analytical views, UGT suggests that consumers are in control of selecting media to satisfy their interests and needs. In addition, other theories were extensively studied; thus, UGT was used, since there was only one study on Tiktok related to this topic and, therefore, there is not enough information about it [29].

2.4. Uses and Gratifications Theory (UGT)

Uses and gratifications theory (UGT) [30] is a theory that clarifies why and why people enthusiastically try to find various media to achieve their particular wants and needs. UGT suggests that the gratified consumers through the media choose it to fulfill a range of social, leisure, and informational requirements [15]. Papacharissi and Rubin studied the motives to use the Internet, and they concluded that people seek to fulfill certain requirements, and there are five motives to use the Internet: seeking information, passing time, convenience, entertainment, and interpersonal utility, all of which affect satisfaction [31]. These needs and motives drive people to choose suitable media based on gratification, which refers to the expected benefits from media use [32]. People’s needs and motives vary depending on individual characteristics, traits, and situational exposure [30].

The crucial proposition of UGT is that users are goal-targeted in their channel choice and aggressively understand and incorporate media messages that contain ads, within their daily activities, to attain peak scales of gratification for their wants and needs [33]. Research applying UGT has discovered that users enthusiastically find different channels to attain their needs, whether these needs are entertainment, informational, escapism, or social needs, with self-regulation, media self-efficacy, prior attitudes, habitual behavior, and other elements distinguishing their channel choices [34,35,36].

Recently, academic studies have applied UGT to assess users’ goal-directed utilization behaviors in SNSs context [26,27,28,37]. To be precise, two trends concerning SNS practice among brand users have been recognized: (1) most users concurrently consume many SNS platforms because each has its exclusive purposes and features; (2) users gradually adopt SNSs as Current Contents/Engineering and/or Computing and Technology platforms and use them as an informational tool as well as a communication channel that supports them to achieve their social desires, emotions, and acquire information [12,38].

2.5. The Factors Affecting Social Media (TikTok)

It was noted that the majority of prior research focused on the following elements for social media use and gratification, and these are affection, past time, sharing problems, fashion, social information, and sociability [12], contribution, discovery, social interaction, and entertainment [39]. In the current study, these factors were all used except for social interaction and entertainment. Nevertheless, some factors were merged due to the similar context but were made more relatable to this research and some phrases were changed, such as fashion being changed trendiness, where the idea was to keep up with the latest trends on Tiktok. Furthermore, sharing problems was changed to become a sense of belonging, and social information was changed to become informative, which includes contribution and discovery. Last but not least, self-expression included discovery [12].

2.5.1. Past-Time/Entertainment

Studies showed that past time can affect a person’s use of social media. This refers to stepping further away from duties and burdens and using a form of amusement/entertainment. This factor consists of [40] initial factors: escape, relaxation, and entertainment [12]. In addition, although key enjoyments for all social media are an escape, relaxation, and entertainment, these appear to be more conspicuous in TikTok. Students and teens look at TikTok mainly as a type of pastime, as a practical hobby in their hectic schedules. Moreover, several studies show that this factor relates to individuals killing time, having fun, having a way to escape from daily stress and a busy schedule, and as well as to relax [12].

A previous report showed that escape, relaxation, and entertainment are ICQ (I see you) motives to use while presence, sociability, and affection are intrinsic motives [41]. ICQ is a cross-platform messenger as well as a Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP client). Students who devote longer periods to ICQ also tend to spend more time on online games for entertainment, especially if they do not need to subscribe to any Internet Service Provider (ISP) service at home [41]. Another study [42] stated that the motive behind the use of TikTok is self-expression, social recognition, and fame-seeking, where people (especially teenagers) would like to use TikTok for those aims, especially since TikTok is known for its high reach and this will allow them to shortcut their way to fame. Sometimes, being famous and well recognized among people is what makes a person happy, which makes these kinds of people enjoy using TikTok, even more so when they start reaching a high audience. According to the discussion above the following hypothesis is formulated:

H1.

Past time in Tiktok has a significant positive influence on users’ satisfaction with using Tiktok.

2.5.2. Affection

Affection relates to thanking people, letting people acknowledge that you care about them, showing others encouragement, aiding and assisting others, and showing others that you are concerned about them. These five items were tested previously to enable the researchers to discover what social media platforms provide friendly acts towards the users. The items that were stated were studied by linking them to Facebook [12]. Facebook communications are concentrating on the trade of information. Even though there is no uncertainty that Facebook connections offer a sense of link, they intimately seem like a combination of online media, where messages can be seen by the entire community, and e-mail (writing a private message) [12].

Leung [40] discovered in his research of instant messages (IM) that the gratification features of sociability and affection have a positive correlation with repeated consumption of IM, while the usage of IM for being trendy was adversely related to IM consumption. Therefore, people who utilized IM for affection and socialization consumed IM more frequently. People who consumed IM exclusively to be trendy, by distinction, managed to consume IM less than others. Additionally, previous studies discovered that IM is consumed basically to satisfy needs including affection. Another study by [43] revealed that using social media pleases five socio-psychological demands: demonstrating affection, expressing negative feelings, earning recognition, receiving entertainment, and satisfying cognitive needs. The research found no age differences in utilizing Facebook plus blogs as a method to fulfill social needs or the demand for affection. However, changes in patterns of social media practice were discovered among baby boomers by distinct egotistical characters.

Moreover, Park et al. [44] indicated that Facebook can be used to share posts, photos, messages, and update statuses. The action of sharing info on Facebook is a method of self-disclosure. Disclosure arises when consumers respond and share information by liking, sharing, or commenting on the content. Farrugia [45] described that an act of self-disclosure is original even if revealed again. Online or offline self-disclosure offers people chances to interchange information that can help in developing relationships. Marshall [46] showed that philandering a colleague offline is reaching out to a person to convey curiosity to know them. Farrugia [45] stated that, usually, relationships are related to trust, satisfaction, love, passion, honesty, and commitment. Finally, Papp et al. [47] determined that the usage of Facebook has changed the approach individuals act together and build relationships, discovering that people cannot ignore Facebook connections’ potential to develop intimate relations, which is important for personal relationships, and the study of [12] explained the differences and similarities between Facebook and instant messages and how they contribute to the use and gratification for social media. This counter-argument has made us come up with the hypothesis below:

H2.

Affection with Tiktok has a significant positive influence on users’ satisfaction with using Tiktok.

2.5.3. Trendiness

The consumption of social network sites (SNSs) has become widespread and, therefore, the use of digital technologies and adoption of digital technologies follow a social trend. This means that if a medium becomes popular among users, other users will start using it since everyone else is. This is what happened with Facebook, when Facebook started; people started downloading it and using it since, at the time, their friends and family members used it. This brings us to the fact that people are attracted to trends and like to stay fashionable, especially young users (teens) [12]. Generation and age play a role in the effect of this factor. This is proven by previous studies which showed that young users are more into adopting trends and are affected by trends and new fashion as well. [12]. According to [48], a study that explains the habits of teenagers that are using social media and how they are using it, results show how being trendy is very important to them and how it could affect their satisfaction because being trendy could lead to better belonging for specific groups. Therefore, the following hypothesis is developed:

H3.

Trendiness in Tiktok has a significant positive influence on users’ satisfaction with using Tiktok.

2.5.4. A Sense of Belonging

As mentioned earlier in the study of [48], teenagers, according to their habits on social media, would like to be trendy, this is also connected to the sense of belonging where the more they become trendy, the more they will be considered as a part of a specific group of people, giving them a better sense of belonging. In addition to the fact that the feeling of personal participation in a system or atmosphere that let people feel like they are an intrinsic part of the system or environment is known as a sense of belonging [49]. In a study done by [50], people can expand their offline friendships into an online world using social networking platforms such as Tiktok where they can share information with others, and comment on other people’s activities, in addition to sending and receiving private messages. Therefore, using a social networking site can make it easier than ever to fulfill one’s desire to belong. Papp et al. [50] mainly focused on Facebook and mentioned how using social networking sites might lead to an increase in the possibility of social rejection, which can lead to loosening the sense of belonging to a specific group in people’s lives in addition to the fact that it might lead to a change in an individual’s attitude to the strong influence it has on it. Finally, Graff [51] mentioned in his research that people with a strong sense of belonging report higher levels of satisfaction, less depression and loneliness, and higher self-esteem. Certainly, achieving a sense of belonging is a powerful motivator for using social media, where influencers can be open and expressive when it comes to their personal stories, habits, and overall life, which attracts an audience that has experienced similar situations. Hence, normalizing these situations and forming a bond of the relation between the audience and their influence, gives the audience a sense of belonging and fitting in. From the previous research, it can be stated that one’s sense of belonging may have a strong impact on satisfaction using TikTok. Therefore, the following hypothesis is derived:

H4.

A sense of belonging in Tiktok has a significant positive influence on users’ satisfaction with using Tiktok.

2.5.5. Sociability

Sociability refers to individuals engaging socially for bonding, interacting, and sharing through social media [52]. In today’s culture, sociability is evolving, with social media serving as a big facilitator and a platform for people to shape friendships or relationships [53]. Osazee-Odia [54] explained that social media sociability gives the chance to develop connections, and the number of friends, contacts, and confidantes has grown at a rapid rate. Décieux et al. [55] concluded people are constantly using social media networks to stay connected with people and connect with peers. Hu et al. [56] mentioned that the level of using social media strong impact on users’ happiness with their online social relationships, in which TikTok can help decrease loneliness through the users’ everyday social connectedness, as well as provide social psychological advantages for social interactions and emotional well-being. Eckstein [57] stated social media is simply media without social contact. People use social media as a two-way communication instrument. They are looking for people with whom they can communicate. In the current study, it can be stated that Tiktok became a way for people to communicate and create friends online. Based on this, it can be suggested that:

H5.

Sociability in Tiktok has a significant positive influence on users’ satisfaction with using Tiktok.

2.5.6. Informative

People use social networking sites for a variety of purposes, one of which is to obtain information [58]. Individuals, entities, and agencies all benefit from information exchange in several ways [59]. Short videos, which can last from a few seconds to a few minutes, have become a common way for people to learn and share artistic skills such as cooking, drawing, and crafting, and this is the main content of Tiktok and how it works [60]. Tiktok and other SNSs are reforming the learning artistic skills experience with visually appealing resources and communication characteristics, and it also enables people to socialize with others who have common interests. Social networking may promote the creation and exchange of information among people with common goals and attitudes, generating alternate viewpoints and innovative ideas in online communities, since social interactions are essential qualities for transferring knowledge among individuals [60]. People are more optimistic about learning collaboration on social media because it gives them a more engaging environment and motivates them to participate in knowledge-related events. Short video platforms have become a common way for millennials to share entertaining content via social media. Most short video platforms are smartphone apps that allow users to create, upload, post, and watch short videos [60]. Thus, previous studies showed that information and content have a great influence on people and on their satisfaction with using social media. Hence, it can be stated that informativeness has an important influence on consumers’ satisfaction with using SNSs and particularly short videos at Tiktok. Based on the previous discussion, it may be postulated that:

H6.

Informativeness in Tiktok has a significant positive influence on users’ satisfaction with using Tiktok.

2.5.7. Self-Expression

Self-expression through social media is defined as “the level of consumer uses social networking sites” to show their personalities, values, and characteristics to the public [61]. Moreover, it is the competence to communicate verbally when interacting with others [62]. It is a way in which people can make their feelings and thoughts familiar by using self-expressive information [63]. Where people transfer their opinions, ideas, and perceptions to others through nonverbal or verbal manners, containing written and spoken words, gestures, and images [64,65]. Self-expression motivates users to express their thoughts through distinct platforms [66]. In addition, self-expression is relatively important as many if not all since users prefer to express their own identity and individuality [67]. On the other hand, many studies [66,68,69,70,71,72,73] declared that self-expression increases brand engagement through feedback on products and services which can generate lifetime value. Individuals use social media platforms to satisfy their needs, which is aided by self-expression [66,74,75]. Furthermore, people’s satisfaction rises when other users interact with their content where they stated their feelings. This can be done through liking, sharing, commenting, and reactive icons [62,76,77]. Users can also feel satisfied when they freely express themselves within an online community to ask other colleagues to share an opinion, information, experience, and interest on the same platform [70,73,78]. Many studies believe that there is a strong correlation between self-expression and satisfaction. For instance, Anderson et al. [48,62,79] showed that with satisfaction and self-expression, the popularity of social media can grow immensely. For the current research, self-expression is defined as a way to express your feelings, ideas, personality, and opinions using spoken and unspoken words. Based on the above discussion, it can be suggested that:

H7.

Self-expression in TikTok has a significant positive influence on users’ satisfaction with using TikTok.

2.5.8. Satisfaction and Continuous Intention to Use

Satisfaction is described as an emotional state or a noticeable level of gratification an individual has from a product, service, or a social online environment [80,81,82,83,84]. Satisfaction can be gained from social interactions on different platforms; thus, social media interactions increase satisfaction [69,85,86,87]. Satisfaction has been said to be one of the most potent and significant relational outcomes [88,89,90]. Satisfaction encourages creating an improved relationship between consumers and social media platforms. This enhanced relationship will motivate users to write better feedback and spread positive word-of-mouth which reflects how satisfied the user is [88,91,92]. Hence, increasing users’ satisfaction levels is crucial for social media sites [93].

The continuous intention is also said to be behavioral is the willingness of users to continue browsing, publishing content, and remaining loyal to the same social media platform. It is staying committed to knowledge searching and involvement [94,95,96]. Moreover, it reflects consumer behaviors that are provoked by different users’ knowledge, points of view, and attitudes [97,98]. Brand image mediates the correlations between sales promotion, social media advertising, and behavioral intention. Furthermore, a continuous intention has two separate types that are treated in different ways, which are previous usage and perceived benefits [99,100]. Many argue that there is an insignificant correlation between behavioral intention and social media advertising content; however when users are persuaded by the social media advertising content, they create a positive and favorable image for that platform [98,101].

Customer satisfaction has a major effect on behavioral intentions. This has been proved, as when people are satisfied with a service or product, they will repeat purchasing and using it, spread positive word of mouth (WOM), have loyalty, and adopt continuous intention [102,103,104,105]. Moreover, when users produce a positive effect of satisfaction on diverse social media platforms, you see how they satisfy their own needs and pursue a change behaviors more related to social media which leads to behavioral intention [83,106,107]. In addition, when users are pleased with their social media interaction, they more frequently visit and will use the social media platform again [108]. Therefore, they become more likely to be more engaged when satisfied. Based on the above discussion, the following hypothesis is assumed:

H8.

Satisfaction has a significant positive influence on users’ Continuous Intention with using TikTok.

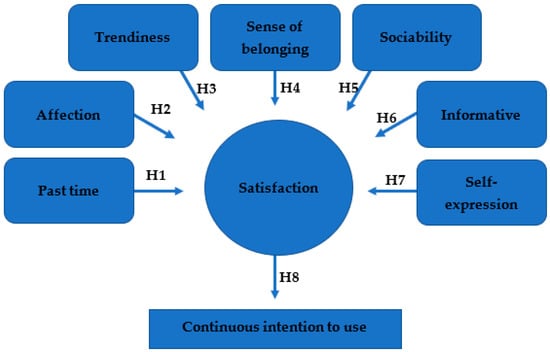

2.6. Research Model

The research model shown below represents the factors that influence the satisfaction of users using different SNSs, and the influence of satisfaction on the continuous intention of TikTok users, see Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research Model.

3. Materials and Methods

The most appropriate method for investigating this research is to take a quantitative approach since it has several advantages; for instance, using quantitative research is straightforward, errors are not common, and it is less open to subjectivity [109]. Data collection can be used by mobile surveys which allow higher reach and convenience, and are faster and easier than other methods [110,111]. The survey is described as a tool for data collection from respondents to the questionnaire [112]. The data collection was split into two sections: secondary and primary sources. In terms of the secondary source, the available literature and other related articles were read to establish a theoretical structure and to learn what previous research had to say about the chosen subject. The survey was created and designed using Google Forms [111,113]. The questionnaire was shared on several social media sites such as WhatsApp, Instagram, and Facebook groups by using a link and it was easy to access.

The survey contains three sections. The first part includes the question “Do you use TikTok?” and only TikTok users were eligible to fill out the survey. The second part includes the demographic variables, which are gender and age. The questionnaire only focused on people living in Jordan who are over 17 years old. The third section consists of 24 items, all were measured by using a Likert scale from “1” for strongly disagree to “5” for strongly agree.

The following variables were selected for this study: past time measured by using two items, affection by using two items, trendiness by using three items, the sense of belonging by using two items, and sociability by using two items, all adapted from [12]. Four items were used to measure informative, extracted from [12,39]. Three items were used to measure self-expression, extracted from [39]. Four items were used to measure satisfaction, extracted from [9]. Finally, three items were used to measure continuous intention, extracted from [114]. Data were collected within 1 month, therefore the study used a cross-sectional approach to collect data. The total filled-out responses were 606, 204 people answered “No” to the question “Do you use TikTok?” leaving 402 responses that were valid for further analysis. The size of the respondents was fair since there were 24 items and the minimum range for each item number was (10 to 15), which gives 240, and the survey size was 402; therefore, it is said to be valid [115]. Then, Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was performed, which is the most widely used methodology in the quantitative social sciences [116].

4. Results

The survey requests respondents to define their age and gender. Table 1 shows that out of 606 participants, 402 participants used TikTok, while 204 participants did not use TikTok. There are 259 (64.4%) females and 143 (35.6%) males, which means that the females exceeded the males in this survey. As for the respondents’ ages, the majority were 18–29 years old, 377 (93.8%) respondents, while other ages made up 6.2%.

Table 1.

Demographics Analysis of Sample.

4.1. Reliability and Validity Tests

4.1.1. Exploratory Factorial Analysis (EFA)

EFA uses statistics to analyze the variances among items by testing each item’s relationship with its dimension [117]. The criterion that specifies the rule of thumb when performing an EFA is factor loadings >0.60, and cross-loadings <0.30. One item (question) from informative was deleted because the value is lower than the threshold recommended by [117] as the factor loadings value for this element was 0.341. Table 2 shows that in the remaining questions, the factor loadings values were from 0.740 to 0.957, which is above the recommended threshold of (0.60) [118]. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkine (KMO) indicates data harmony and was (KMO = 0.902, df = 276, p < 0.05 = 0.000), which is more than (70%) [119,120,121]. Further, Bartlett test for Sphericity (χ2 = 6733.064, df = 276, p < 0.05 = 0.000).

Table 2.

Exploratory Factorial Analysis Loading Matrix.

4.1.2. Construct Reliability and Validity Analysis

The analysis of reliability is a psychometric attribute of responses to a measure given within particular circumstances [122]. Cronbach’s alpha is a proposition that the scale presents internal consistency with a high level [123]. Cronbach’s alpha shows more bias to reliability than composite reliability [124]. Composite reliability (CR) of (0.80) and Cronbach alpha’s (α) of (0.70) are accepted [125]. Convergent validity uses the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) to describe the correlation between the concept and its measures [126]. This kind of validity can establish through the extracted average variance, which shows the relationship between a variable and its components [127].

Table 3 shows Cronbach’s alpha (α exceeding (70%) for all scales (e.g., 0.722 to 0.919), and the Composite Reliability (CR) for scales was higher than (80%) (0.843 to 0.948). The (AVE) of the eight variables was more than (50%) which is the advised threshold, and the (AVE) of the eight dimensions is (0.643 to 0.866), denoting that the items are related to dimensions.

Table 3.

Construct Reliability and Validity Analysis (Descriptive Analysis).

Table 3 also shows the descriptive analysis. The total average of answers for Affection is 3.292, the total average of answers for continuous intention to use TikTok is 3.658, the total average of answers for informative is 2.673, the total average of answers for past time is 4.014, the total average of answers for satisfaction is 3.054, the total average of answers for self-expression is 2.698, the total average of answers for the sense of belonging is 1.665, the total average of answers for sociability is 1.799, and, finally, the total average of answers for trendiness is 1.852. The results show that the sense of belonging, sociability, and trendiness is not well implemented yet.

4.1.3. Validation of Model Convergent and Discriminant Validity

Before starting structural analysis, the research model must be confirmed by a set of indicators to check the model’s correctness, as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Fit Model.

Confirmatory factor analysis indicates that all of these indicators fall within the recommended values. Table 3 and Table 4 indicate that all indicators are higher than recommended values, therefore the model is fit and suitable. Discriminant validity shows how each item is related to its dimension [125]. Discriminant validity is measured by comparing the construct correlation coefficients with the square roots of AVE [132]. Table 5 shows discriminant validity.

Table 5.

Discriminant Validity Matrix.

4.2. Hypotheses Testing

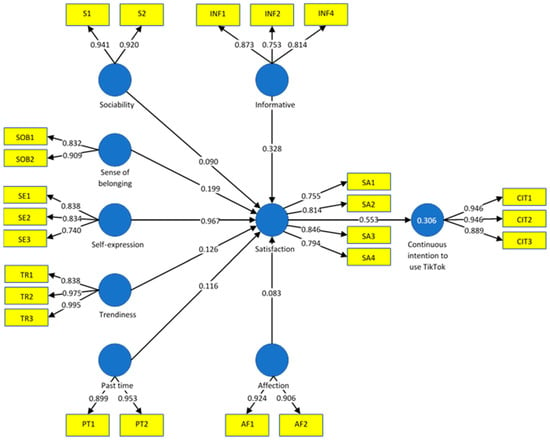

To test the model, the study applied Path Analysis through the structural equation. According to [133], this test analyzes complicated casual models and is based on the covariance-based structural equation. The structural equation shows four values: the effect size (f2), path coefficients (β), and p-value [118], also will be clarified the variation in a customer purchase intention variable which was clarified by (R2) [128,134]. Table 6 and Figure 2 show the points of cut-off of the tests. Depending on the above-mentioned hypotheses, structural equation analysis was as shown below:

Table 6.

The Results of Testing Hypotheses.

Figure 2.

The Study’s Model Testing.

H1: Past time in TikTok has a significant positive influence on users’ satisfaction with using TikTok. This hypothesis is unaccepted, where (β = 0.116; t-value = 1.928; p > 0.05; = 0.054).

H2: Affection in TikTok has a significant positive influence on users’ satisfaction with using TikTok. This hypothesis is unaccepted, where (β = 0.083; t-value = 1.317; p > 0.05; = 0.189).

H3: Trendiness in TikTok has a significant positive influence on users’ satisfaction with using TikTok. This is an acceptable hypothesis, where (β = 0.126; t-value = 2.116; p < 0.05; = 0.035). This effect is considered to be small based on the value (f2 = 0.026). This means that increased trendiness in TikTok leads to increase users’ satisfaction with using TikTok.

H4: A sense of belonging has a significant negative influence on users’ satisfaction with using TikTok. This is an acceptable hypothesis, where (β = 0.139; t-value = 2.782; p < 0.05; = 0.006). This effect is considered to be small based on the value (f2 = 0.029). This means that increasing the sense of belonging leads to increase users’ satisfaction with using TikTok.

H5: Sociability has a significant positive influence on users’ satisfaction with using TikTok. This hypothesis is unaccepted, where (β = 0.030; t-value = 10.439; p > 0.05; = 0.661).

H6: Informativeness has a significant positive influence on users’ satisfaction with using TikTok. This is an acceptable hypotheses, where (β = 0.328; t-value = 6.232; p < 0.05; = 0.000). This effect is considered moderate based on the value (f2 = 0.164). This means that increased informativeness leads to increase users’ satisfaction with using TikTok.

H7: Self-expression has a significant positive influence on users’ satisfaction with using TikTok. This is an acceptable hypotheses, where (β = 0.367; t-value = 7.038; p < 0.05; = 0.000). This effect is considered moderate based on the value (f2 = 0.164). This means that increased self-expression leads to increase users’ satisfaction with using TikTok.

The variance in the users’ satisfaction with using TikTok was explained by four characteristics (trendiness, sense of belonging, informativeness, and self-expression), the characteristics can explain 48.5% of satisfaction, which strongly affect satisfaction, where (R2 = 0.485).

H8: Satisfaction has a significant positive influence on users’ continuous intention to use TikTok. This is an acceptable hypothesis, where (β = 0.553; t-value = 4.675; p < 0.05; = 0.000). This effect is considered to be big based on the value (f2 = 0.442). This means that increased users’ satisfaction leads to increased users’ continuous intention to use TikTok.

The variance in user continuous intention to use TikTok that was explained by online user satisfaction with using TikTok was moderate (R2 = 0.306).

5. Discussion

The purpose of this research is to explore the factors that affect customer satisfaction using TikTok and continuous intention to use it, and what are the factors that motivate them to continue using it and become loyal users. Data was gathered, evaluated, and interpreted, to determine how each factor affected satisfaction while using Tiktok, which will ultimately contribute to the continuous use of the application.

The data analysis reveals that the model variance is strong, where R2 = 0.485. Four of the seven hypotheses were accepted, which are trendiness, sense of belonging, informativeness, and self-expression, with the most significant impact coming from self-expression β = 0.367, followed by informativeness β = 0.328, then sense of belonging β = 0.139, and trendiness β = 0.126. However, three factors were rejected (sociability, affection, and past time) in the following order: sociability had the lowest effect β = 0.030, followed by affection β = 0.083, and finally past time β = 0.116.

Research results show that past time in TikTok has no significant positive influence on users’ satisfaction with using TikTok. Previous studies proposed that past time is positively affecting consumer satisfaction with TikTok. Quan-Haase et al. [12,136] showed that past time is positively correlated to satisfaction using Facebook. Previous research has shown that providing entertainment through social media elicits positive emotions that affect people’s attitudes. According to [137] the ability of social media to fulfill the user’s desires for escapism, enjoyment, and distress relaxation may be evaluated by the entertainment gratifications obtained through it. Social networking sites are part of daily life for many people. Finally, sometimes passing time could affect a person’s life negatively, especially hard workers, and students who have something important.

The results suggest that affection in TikTok has no significant positive impact on customer satisfaction. Sheth et al. [137] showed that there is a remarkable lack of data establishing the emotional experience of browsing social media. Based on the principle of emotions, it stated that reading or watching positive content on social media will lead to positive feelings and vice versa. Anyway, is still difficult to understand how and whether affection has influenced a person’s behavior. Quan-Haase et al. [12] showed the opposite, where it states that affection has a positive influence on using social media platforms.

Research results show that trendiness positively and significantly impacts TikTok satisfaction. Bilgin [138] stated that social networking trends aid in the formation of more interpersonal connections because it allows individuals to interact with like-minded people and it often satisfies people’s desires for better esteem and self-actualization.

Results showed that the sense of belonging positively and significantly impacts satisfaction using TikTok. Eren et al. [139] concluded that using Tiktok leads to creating a sense of belonging also leading to satisfaction using the application. People like the sense of being a part of something that gives them a feeling of safety and trust which affect satisfaction using Tiktok.

Results also show that sociability does not impact satisfaction when using TikTok. Chiang et al. [136] indicated that sociability does not influence satisfaction and this confirmed the dependability of the results to the present research. Nguyen et al. [140] quote Norbert Elias, “the issue of human relationships constitutes the base of society”. Usually, the audience who are using TikTok follow people and only enjoy content or videos but are not interactively connected.

Findings indicate that informativeness has a positive significant influence on satisfaction by using TikTok. Kujur et al. [141] stated consumers’ online engagement is greatly influenced by the presence of informative content. Islam et al. [142] assured that informativeness has a positive impact on satisfaction.

Analysis showed that TikTok satisfaction is positively influenced by self-expression. [143] concluded teenagers believe that social media positively affect the users’ mood. Vecchio et al. [144] mentioned as a larger audience started using TikTok from different ages, the material broadened into a field of humanity and self-expression.

Finally, results showed that satisfaction positively and significantly affects continuous intention to use TikTok. Garg et al. [145] indicated that user satisfaction has affected consumers’ continuous intention to use Tiktok. Bhattacherjee [146] discovered that customer satisfaction is positively related to the decision to continue using the platform and thus has a significant impact on the desire to do so.

6. Conclusions

People use social media for several purposes. Moreover, they use different social media tools to communicate with each other such as TikTok, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, Snapchat, Kik, Messenger, Twitter, WhatsApp, and other tools. Nowadays, organizations, whether they are public or private, use social media tools to keep in contact with their residents or customers. Business organizations heavily use different social media tools to satisfy customers with their products and services. TikTok is increasingly used to communicate with customers, at the same time many factors affect TikTok users, affecting users’ satisfaction and continuous intention to use TikTok. Therefore, this research is dedicated to answering the below questions: What are the factors that affect continuous intention to use TikTok in Jordan? To what extent do these factors, past-time, affection, sense of belonging, sociability, trendiness, self-expression, and informativeness, influence satisfaction using TikTok? To what extent does satisfaction with TikTok influence continuous intention to use TikTok? To answer these questions, the research uses the quantitative cross-sectional approach. Data were collected by mobile surveys. Facebook, WhatsApp, TikTok, and Instagram, were used to distribute a questionnaire. Out of 606 filled questionnaires, only 402 were suitable for further analysis. These questionnaires were coded against SPSS. Then validity and reliability were checked and Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was used for analysis.

The research results showed that self-expression, informativeness, a sense of belonging, and trendiness in TikTok significantly and positively influence TikTok users’ satisfaction. However, affection in TikTok and past time in TikTok do not influence TikTok users’ satisfaction. Satisfaction positively significantly influences users’ continuous intention to use TikTok. Theoretically, the current research shows many factors that impact satisfaction using Tiktok and the continuous intention to use TikTok. The theoretical model uses the use and gratification theory. It uses a new variable, trendiness, to examine its relationship with user satisfaction. Practically, many marketing agencies and companies, as well as influencers, will benefit from this research. Since trendiness has a significant positive impact on satisfaction, marketing agencies and influencers should always follow trends to be able to attract consumers. The sense of belonging has a direct important effect on satisfaction. Marketing agencies and influencers should benefit from this factor as they should use it as a method to connect and relate to their consumers. Another factor that has a significant positive impact on satisfaction is informativeness. The marketing agencies and influencers should always share knowledge and information on social media while using TikTok will attract more consumers. Self-expression is another factor that has a significant positive influence on satisfaction. People tend to use TikTok as a channel to express their thoughts, emotions, and even problems. Companies and influencers should understand customers’ wants and needs and post content that triggers this aspect to sell what they want. In addition, satisfaction significantly positively affects continuous intention to use TikTok. If the customers and users are more satisfied, they will encourage feedback about that product. Marketing agencies and influencers must satisfy their consumers’ needs to gain continuous intention to use TikTok and they should always collect feedback to assure the satisfaction of their consumers. Finally, this research is cross-sectional and was conducted in Jordan. The study recommends conducting future studies to analyze behavior over time, applying the same research model in other countries, and testing the effect of other factors such as self-presentation and motivational cues. Moreover, organizations should use different social media channels such as TikTok, Instagram, Facebook, Snapchat, LinkedIn, Messenger, Kik, and Twitter as marketing tools to aware, inform, attract, retain, and engage users and increase their satisfaction, which affects users’ continuous intention to use TikTok application. Marketers should concentrate on affection, trendiness, sense of belonging, informativeness, and self-expression more than past time and sociability. Recently, TikTok has introduced Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR) to its camera, which helps users to create and develop their camera effects and feel they are within a scenic environment; therefore, marketers can use this property as a marketing tool and the study recommends studying the effect of TikTok Augmented Reality on users’ behavior and attitudes [147]. Moreover, the VR in the xReality framework can provide 360-degree views to multi-sensing, as well as allow a full-immersion VR experience [148].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A.-H. and M.A.-K.; methodology, A.-A.A.S. and S.A.-H.; software, N.N., M.M. and Q.A.G.; validation, A.-A.A.S., S.A.-H. and M.A.-K.; formal analysis A.-A.A.S. and S.A.-H.; investigation, N.N., M.M. and Q.A.G.; resources, N.N., M.M. and Q.A.G.; data curation, A.-A.A.S. and S.A.-H.; writing—original draft preparation, N.N., M.M. and Q.A.G.; writing—review and editing S.A.-H., and M.A.-K.; visualization, N.N., M.M. and Q.A.G.; supervision, M.A.-K.; project administration, S.A.-H.; funding acquisition, A.-A.A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Middle East University. Thanks for its Funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data were included in the research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Vinney, C. What Is Uses and Gratifications Theory? Definition and Examples. Available online: https://www.thoughtco.com/uses-and-gratifications-theory-4628333 (accessed on 5 March 2022).

- García-Jiménez, A.; López-Ayala-López, M.C.; Gaona-Pisionero, C. A vision of uses and gratifications applied to the study of Internet use by adolescents. Commun. Soc. 2012, 25, 231–254. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, D.M.; Ellison, N.B. Social network sites: Definition, history, and scholarship. J. Comput. Commun. 2007, 13, 210–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phua, J.; Jin, S.A.A. “Finding a home away from home”: The use of social networking sites by Asia-Pacific students in the United States for bridging and bonding social capital. Asian J. Commun. 2011, 21, 504–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şimşek, B.; Abidin, C.; Brown, M.L. Musical. ly and Microcelebrity Among Girls. In Microcelebrity around the Globe: Approaches to Cultures of Internet Fame; Emerald Group Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2018; pp. 47–56. ISBN 9781787567498. [Google Scholar]

- Leskin, P. The Life of TikTok Head Alex Zhu, the Musical.ly Cofounder in Charge of Gen Z’s Beloved Video-Sharing App. Available online: https://www.businessinsider.com/tiktok (accessed on 5 March 2022).

- Qu, D. Douyin and TikTok are Released; Douyin for the Chinese Market; TikTok for the Rest of the World. Available online: https://www.historyofinformation.com/detail.php?id=5298 (accessed on 7 March 2022).

- Monroe, R. 98 Million TikTok Followers Can’t Be Wrong How a 16-year-old from Suburban Connecticut Became the Most Famous Teen in America. Available online: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2020/12/charli-damelio-tiktok-teens/616929/ (accessed on 7 March 2022).

- Kanthawongs, P.; Kanthawongs, P.; Chitcharoen, C. Factors affecting perceived satisfaction with Facebook in education. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Cognition and Exploratory Learning in Digital Age (CELDA 2016), Mannheim, Germany, 28–30 October 2016; pp. 188–194. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.T.; Su, S.F. Motives for Instagram use and topics of interest among young adults. Futur. Internet 2018, 10, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apodaca, J. True Self and the Uses and Gratifications of Instagram among College-Aged Females. Bachelor’s Thesis, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Quan-Haase, A.; Young, A.L. Uses and Gratifications of Social Media: A Comparison of Facebook and Instant Messaging. Bull. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2010, 30, 350–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, K.; Lee, Y.J. Social Media and Brand Purchase: Quantifying the Effects of Exposures to Earned and Owned Social Media Activities in a Two-Stage Decision-Making Model. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2015, 32, 204–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuin, G.P.; Huey, L.H.; Hwee, V.T.M. Malaysian Youth’s Preferences towards the Use of Social Network Networking. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman, Kampar, Malaysia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Phua, J.; Jin, S.V.; Kim, J.J. Gratifications of Using Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, or Snapchat to Follow Brands: The Moderating Effect of Social Comparison, Trust, Tie Strength, and Network Homophily on Brand Identification, Brand Engagement, Brand Commitment, and Membership Intentio. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 412–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qualman, T. Design and Numerical Investigations of a Counter-Rotating Axial Compressor for A Geothermal Power Plant Application. Master’s Thesis, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Colliander, J.; Dahlén, M. Following the Fashionable Friend: The Power of Social Media: Weighing publicity effectiveness of blogs versus online magazines. J. Advert. Res. 2011, 51, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W.-H.S.; Men, L.R. Motivations and Antecedents of Consumer Engagement with Brand Pages on Social Networking Sites. J. Interact. Advert. 2013, 13, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.J.; Phua, J.; Shan, Y. Starring in Your Own Linkedin Job Advertisement: The Influence of Self-Endorsing, Oneness, and Involvement on Brand Attitude. In Proceedings of the American Academy of Advertising Conference Proceedings, Atlanta, Georgia, 22 April 2014; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurthy, S.; Dou, W. Note from Special Issue Editors: Advertising with user-generated content: A framework and research agenda. J. Interact. Advert. 2008, 8, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergh, B.G.V.; Lee, M.; Quilliam, E.T.; Hove, T. The multidimensional nature and brand impact of user-generated ad parodies in social media. Int. J. Advert. 2011, 30, 103–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulides, G.; Jevons, C.; Bonhomme, J.; Christodoulides, G.; Jevons, C.; Bonhomme, J. Memo to Marketers: Quantitative Evidence for Change—How User-Generated Content Really Affects Brands. J. Advert. Res. 2012, 52, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.A.A.; Phua, J. Following celebrities’ tweets about brands: The impact of Twitter-based electronic word-of-mouth on consumers source credibility perception, buying intention, and social identification with celebrities. J. Advert. 2014, 43, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Youn, S. Electronic word of mouth (eWOM): How eWOM platforms influence consumer product judgement. Int. J. Advert. 2009, 28, 473–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coa, V.V.; Setiawan, J. Analyzing Factors Influencing Behavior Intention to Use Snapchat and Instagram Stories. Int. J. New Media Technol. 2017, 4, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, K.H.; Stefanone, M.A.; Barnett, G.A. Social Network Influence on Online Behavioral Choices: Exploring Group Formation on Social Network Sites. Am. Behav. Sci. 2014, 58, 1345–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muntinga, D.G.; Moorman, M.; Smit, E.G. Introducing COBRAs: Exploring motivations for Brand-Related social media use. Int. J. Advert. 2011, 30, 13–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A. More than Mobile: Migration and Mobility Impacts from the “Technologies of Change” for Aboriginal Communities in the Remote Northern Territory of Australia. Mobilities 2012, 7, 269–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Berger, C.; Roloff, M. Interpersonal Communication; Taylor and Francis: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2019; pp. 277–291. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, E.; Blumler, J.G.; Gurevitch, M. Utilization of mass communication by the individual. Uses Mass Commun. Curr. Perspect. Gratif. Res. 1974, 5578 LNCS, 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Papacharissi, Z.; Rubin, A.M. Predictors of Internet use. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2000, 44, 175–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmgreen, P.; Wenner, L.A.; Rayburn, J.D. Relations between Gratifications Sought and Obtained: A Study of Television News. Commun. Res. 1980, 7, 161–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, R.B.; Rubin, A.M.; Perse, E.M.; Armstrong, C.; Mchugh, M.; Faix, N. Media Use and Meaning of Music Video. J. Mass Commun. Q. 1986, 63, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimmick, J.; Chen, Y.; Li, Z. Competition between the Internet and Traditional News Media: The Gratification-Opportunities Niche Dimension. J. Media Econ. 2004, 17, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, H.; Cho, C.H.; Roberts, M.S. Internet uses and gratifications: A structural equation model of interactive advertising. J. Advert. 2005, 34, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaRose, R.; Eastin, M.S. A Social Cognitive Theory of Internet Uses and Gratifications: Toward a New Model of Media Attendance. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2004, 48, 358–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, H.H. Interactive Digital Advertising vs. Virtual Brand Community: Exploratory Study of User Motivation and Social Media Marketing Responses in Taiwan. J. Interact. Advert. 2011, 12, 44–61. [Google Scholar]

- Lenhart, A. Teens, Social Media & Technology Overview 2015. Pew Res. Cent. 2015. Available online: http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/04/09/teens-social-media-technology-2015 (accessed on 5 March 2022).

- Karnik, M.; Oakley, I.; Venkatanathan, J.; Spiliotopoulos, T.; Nisi, V. Uses & gratifications of a Facebook media sharing group. In Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, CSCW, San Antonio, TX, USA, 23–27 February 2013; pp. 821–826. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, L. College student motives for chatting on ICQ. New Media Soc. 2001, 3, 483–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, L.; Wei, R. More than just talk on the move: Uses and gratifications of the cellular phone. J. Mass Commun. Q. 2000, 77, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossen, C.; Kottasz, R. Uses and gratifications sought by pre-adolescent and adolescent TikTok consumers. Young Consum. 2021, 21, 1747–3616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, L. Generational differences in content generation in social media: The roles of the gratifications sought and of narcissism. Comput. Human Behav. 2013, 29, 997–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, N.; Jin, B.; Annie Jin, S.A. Effects of self-disclosure on relational intimacy in Facebook. Comput. Human Behav. 2011, 27, 1974–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrugia, R.C. Facebook and Relationships: A Study of How Social Media Use is Affecting Long-Term Relationships; RIT Press: Rochester, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 9781303601200. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, J.A. Ethical Leadership, Prototypicality, Integrity, Trust, and Leader Effectiveness. Ph.D. Thesis, Regent University School, Virginia Beach, VA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Papp, L.M.; Danielewicz, J.; Cayemberg, C. “Are we Facebook official?” Implications of dating partners’ Facebook use and profiles for intimate relationship satisfaction. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2012, 15, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.; Jiang, J. Teen’s Social Media Habits and Experiences. PEW Res. Cent. 2018, 5, 33. [Google Scholar]

- Raman, S. Sense of belonging. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 253–311. [Google Scholar]

- Papp, S.J.; Vanman, E.J.; Verreynne, M.; Saeri, A.K. Threats to belonging on Facebook: Lurking and ostracism. Soc. Influ. 2015, 10, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graff, M. Is Using Instagram Beneficial to Well-being? Available online: https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/love-digitally/201911/is-using-instagram-beneficial-well-being (accessed on 7 March 2022).

- Preece, J. Online Communities: Researching sociability and usability in hard-to-reach populations. Australas. J. Inf. Syst. 2004, 11, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufekci, Z. Who Acquires Friends through Social Media and Why? “Rich Get Richer” versus “Seek and Ye Shall Find”. In Proceedings of the ICWSM 2010—Proceedings of the 4th International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media, Washington, DC, USA, 23–26 May 2010; pp. 170–177. [Google Scholar]

- Osazee-Odia, O.U. Investigating the influence of social media on sociability: A study of university students in Nigeria. Int. J. Int. Relat. Media Mass Commun. Stud. 2017, 3, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Décieux, J.P.; Heinen, A.; Willems, H. Social Media and Its Role in Friendship-driven Interactions among Young People: A Mixed Methods Study. Young 2019, 27, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Kim, A.; Siwek, N.; Wilder, D. The Facebook Paradox: Effects of Facebooking on individuals’ social relationships and psychological well-being. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckstein, M. Social Media Engagement: Why it Matters and How to Do it Well; Buffer Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Arli, D. Does Social Media Matter? Investigating the Effect of Social Media Features on Consumer Attitudes. J. Promot. Manag. 2017, 23, 521–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipps, B.; Phillips, B. Social networks, interactivity, and satisfaction: Assessing socio-technical behavioral factors as an extension to technology acceptance. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2013, 8, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiyang, Z.; Jung, H. Learning and Sharing Creative Skills with Short Videos: A Case Study of User Behavior in TikTok and Bilibili. In Proceedings of the International Association of Societies of Design Research Conference, Manchester, UK, 2–5 September 2019; pp. 25–50. [Google Scholar]

- Pagani, M.; Hofacker, C.F.; Goldsmith, R.E. The influence of personality on active and passive use of social networking sites. Psychol. Mark. 2011, 28, 441–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.Y.; Xu, X.; Atkin, D. The alternatives to being silent: Exploring opinion expression avoidance strategies for discussing politics on Facebook. Internet Res. 2020, 30, 1709–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Sherman, D.K. “Express yourself”: Culture and the effect of self-expression on choice. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.F. Exploring the forms of self-censorship: On the spiral of silence and the use of opinion expression avoidance strategies. J. Commun. 2007, 57, 785–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.H.; Lin, Y.H. Online communication of visual information: Stickers’ functions of self-expression and conspicuousness. Online Inf. Rev. 2020, 44, 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Jiang, Y. A human touch and content matter for consumer engagement on social media. Corp. Commun. 2020, 26, 501–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, G. Understanding the appeal of user-generated media: A uses and gratification perspective. Internet Res. 2009, 19, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achado, J.C.; Azar, S.; de Carvalho, L.V.; Mendes, A. Motivations to interact with brands on Facebook—Towards a typology of consumer-brand interactions. In Proceedings of the 10th Global Brand Conference, Turku, Finland, 27–29 April 2015; pp. 169–174. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, M.; Kaltcheva, V.D.; Rohm, A. Hashtags and handshakes: Consumer motives and platform use in brand-consumer interactions. J. Consum. Mark. 2016, 33, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, S.H.; Chang, A. The Psychological Mechanism of Brand Co-creation Engagement. J. Interact. Mark. 2016, 33, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, A.R. The influence of perceived social media marketing activities on brand loyalty: The mediation effect of brand and value consciousness. Asia Pacific J. Mark. Logist. 2017, 29, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.G.; Taylor, M. Empowering Engagement: Understanding Social Media User Sense of Influence. Int. J. Strateg. Commun. 2017, 11, 148–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldus, B.J.; Voorhees, C.; Calantone, R. Online brand community engagement: Scale development and validation. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 978–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, L.; Peluso, A.M.; Romani, S.; Leeflang, P.S.H.; Marcati, A. Explaining consumer brand-related activities on social media: An investigation of the different roles of self-expression and socializing motivations. Comput. Human Behav. 2017, 75, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enginkaya, E.; Yılmaz, H. What Drives Consumers to Interact with Brands through Social Media? A Motivation Scale Development Study. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 148, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Feng, C. Branding with social media: User gratifications, usage patterns, and brand message content strategies. Comput. Human Behav. 2016, 63, 868–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, F.; Lubascher, B.; Moers, T.; Schaap, P.; Spanakis, G. Social emotion mining techniques for Facebook Posts reaction prediction. In Proceedings of the ICAART 2018—Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence, Funchal, Portugal, 16–18 January 2018; Volume 2, pp. 211–220. [Google Scholar]

- Seyyedamiri, N.; Tajrobehkar, L. Social content marketing, social media, and product development process effectiveness in high-tech companies. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2021, 16, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, A.; Kesse, P. Van Anger Topped Love When Facebook Users Reacted to Lawmakers’ Posts after 2016 Election. Available online: https://policycommons.net (accessed on 28 February 2022).

- Ceron, A.; Memoli, V. Flames and Debates: Do Social Media Affect Satisfaction with Democracy? Soc. Indic. Res. 2016, 126, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amegbe, H.; Boateng, H.; Mensah, F.S. Brand community integration and customer satisfaction of social media network sites among students. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2017, 7, 541–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, H.Y.; Janda, S. The effect of customized information on online purchase intentions. Internet Res. 2014, 24, 496–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.L.; Lin, C.L. Why do people stick to Facebook Web Site? A value theory-based view. Inf. Technol. People 2014, 27, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chea, S.; Luo, M.M. Post-adoption behaviors of e-service customers: The interplay of cognition and emotion. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2008, 12, 29–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrecque, L.I. Fostering consumer-brand relationships in social media environments: The role of parasocial interaction. J. Interact. Mark. 2014, 28, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapp, A.; Beitelspacher, L.S.; Grewal, D.; Hughes, D.E. Understanding social media effects across seller, retailer, and consumer interactions. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2013, 41, 547–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohm, A.; Kaltcheva, V.D.; Milne, G.R. A mixed-method approach to examining brand-consumer interactions driven by social media. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2013, 7, 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.H.; North, M.; Li, C. Relationship building through reputation and tribalism on companies’ Facebook Pages: A uses and gratifications approach. Internet Res. 2017, 27, 1149–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Satisfaction: A Behavioral Perspective on the Consumer, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.Z.K.; Benyoucef, M.; Zhao, S.J. Building brand loyalty in social commerce: The case of brand microblogs. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2016, 15, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attar, R.W.; Shanmugam, M.; Hajli, N. Investigating the antecedents of e-commerce satisfaction in social commerce context. Br. Food J. 2021, 123, 849–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffee, J.C.; Lowenstein, L.; Rose-Ackerman, S. Knights, Raiders, and Targets: The Impact of the Hostile Takeover; Oxford University Press on Demand: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard, A.L. Testing a model of sense of virtual community. Comput. Human Behav. 2008, 24, 2107–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.J.; Barry, T.E.; Dacin, P.A.; Gunst, R.F. Spreading the word: Investigating antecedents of consumers’ positive word-of-mouth intentions and behaviors in a retailing context. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2005, 33, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, S.W.; Hung, I.H. Understanding knowledge outcome improvement at the post-adoption stage in a virtual community. Inf. Technol. People 2016, 29, 774–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhao, K.; Stylianou, A. The impacts of information quality and system quality on users’ continuance intention in information-exchange virtual communities: An empirical investigation. Decis. Support Syst. 2013, 56, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godey, B.; Manthiou, A.; Pederzoli, D.; Rokka, J.; Aiello, G.; Donvito, R.; Singh, R. Social media marketing efforts of luxury brands: Influence on brand equity and consumer behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5833–5841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raji, R.A.; Rashid, S.; Ishak, S. The mediating effect of brand image on the relationships between social media advertising content, sales promotion content, and behaviuoral intention. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2019, 13, 302–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.V.; Nguyen, T.; Oncheunjit, M. Understanding continuance intention in traffic-related social media: Comparing a multi-channel information community and a community-based application. Internet Res. 2020, 30, 539–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Stylianou, A.C.; Zheng, Y. Predicting users’ continuance intention in virtual communities: The dual intention-formation processes. Decis. Support Syst. 2013, 55, 903–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alford, B.L.; Biswas, A. The effects of discount level, price consciousness, and sale proneness on consumers’ price perception and behavioral intention. J. Bus. Res. 2002, 55, 775–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, R.; Zhang, J. The effect of service interaction orientation on customer satisfaction and behavioral intention: The moderating effect of dining frequency. Asia Pacific J. Mark. Logist. 2012, 24, 153–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Fang, Y.; Vogel, D.; Liang, L. Understanding affective commitment in social virtual worlds: The role of cultural tightness. Inf. Manag. 2018, 55, 984–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.T.; Wang, Y.S.; Liu, E.R. The stickiness intention of group-buying websites: The integration of the commitment–trust theory and e-commerce success model. Inf. Manag. 2016, 53, 625–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Fang, Y.; Vogel, D.; Jin, X.L.; Zhang, X. Attracted to or locked in? predicting continuance intention in social virtual world services. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2012, 29, 273–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eginli, A.T.; Tas, N.O. Interpersonal Communication in Social Networking Sites: An Investigation in the Framework of Uses and Gratification Theory. Online J. Commun. Media Technol. 2018, 2, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Corrada, M.S.; Flecha, J.A.; Lopez, E. The gratifications in the experience of the use of social media and its impact on the purchase and repurchase of products and services. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2020, 32, 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallock, W.B.; Roggeveen, A.; Crittenden, V.L. Social Media and Customer Engagement: Dyadic Word-of-Mouth. In Developments in Marketing Science: Proceedings of the Academy of Marketing Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; p. 11815. [Google Scholar]

- DeVault, A.E. A Mixed Methods Study of Iowa World Language Teachers’ Attitudes toward the Inclusion of Students with Disabilities; The University of Iowa: Iowa City, IA, USA, 2020; ISBN 9798662496828. [Google Scholar]

- Mander, J. How to Use Qualitative and Quantitative Research to Your Advantage; GlobalWebIndex: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, J.R.; Mathur, A. The value of online surveys: A look back and a look ahead. Internet Res. 2018, 28, 854–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Check, J.; Schutt, R.K. Research Methods in Education; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nayak, M.; Narayan, K.A. Strengths and Weakness of Online Surveys. IOSR J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2019, 24, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, D.H.; Lankton, N.; Tripp, J. Social networking information disclosure and continuance intention: A disconnect. In Proceedings of the Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Fall 11-2010, Kauai, HA, USA, 4–7 January 2011; pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- VanVoorhis, C.R.W.; Morgan, B.L. Understanding Power and Rules of Thumb for Determining Sample Sizes. Tutor. Quant. Methods Psychol. 2007, 3, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, D. Structural Equation Modelling: Foundations and Extensions; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2008; Volume 10. [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Eijk, C.; Rose, J. Risky business: Factor analysis of survey data—Assessing the probability of incorrect dimensionalisation. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagan, M.H.; Neill, S.; Wooldridge, B.R. Exploring the intention to use computers: An empirical investigation of the role of intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, and perceived ease of use. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2008, 48, 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics; Pearson: London, UK, 2019; ISBN 9780134790541. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, H.F.; Rice, J. Educational and Psychological Measurement. Ser. Rev. 1974, 34, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glen, S. Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) Test for Sampling Adequacy. Available online: https://www.statisticshowto.com/kaiser-meyer-olkin/ (accessed on 28 February 2022).

- Wilkinson, L. Statistical methods in psychology journals: Guidelines and explanations. Task Force on Statistical Inference American Psychological. Am. Psychol. 1999, 54, 594–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekaran, U.; Bougie, R. Research Method for Business: A Skill Building Approach, 7th ed.; Wiley & Son Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, K.K.-K. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Techniques Using SmartPLS. Mark. Bull. 2013, 24, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage Publications. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 6, 220–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couchman, P.K.; Fulop, L. Building trust in cross-sector R & D collaborations: Exploring the role of credible commitments. In European Group for Organizational Studies (EGOS) 22nd Colloquium Trust Within and Across Boundaries; Griffith University; Griffith University: Bergen, Norway, 2006; pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, P.; Doll, W.J.; Nahm, A.Y.; Li, X. Knowledge sharing in integrated product development. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2004, 7, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modelling. In Modern Methods for Business Research Chapter Ten; Marcoulides, G.A., Ed.; Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 1998; Volume 295, pp. 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Lowry, P.B.; Gaskin, J. Partial Least Squares (PLS) Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) For Building and Testing Behavioral Causal Theory: When to Choose it and How to Use it. IEEE Trans. Prof. Commun. 2014, 57, 123–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate data analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice-Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; Volume 15. [Google Scholar]

- KAMIS, R.P. The Relationship between Expanded Concepts of Self and Well-Being. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/1df783fe36087b5f576f1b77f786ffde/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750 (accessed on 28 February 2022).

- Chiang, I.P.; Lo, S.H.; Wang, L.-H. Customer Engagement Behaviour in Social Media Advertising: Antecedents and Consequences. Contemp. Manag. Res. 2017, 13, 193–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]