Innovation Centric Knowledge Commons—A Systematic Literature Review and Conceptual Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Exploring the application of commons within KM literature through a Systematic Literature Review (SLR). Based on our review, this is the first time such a study has been reported.

- Focusing on innovation and discussing ways the commons framework can be utilized to support Open Innovation.

2. Commons, Knowledge Commons, and Open Innovation

3. Methods

3.1. Planning the Literature Review

3.2. Conducting the Literature Review

4. Results

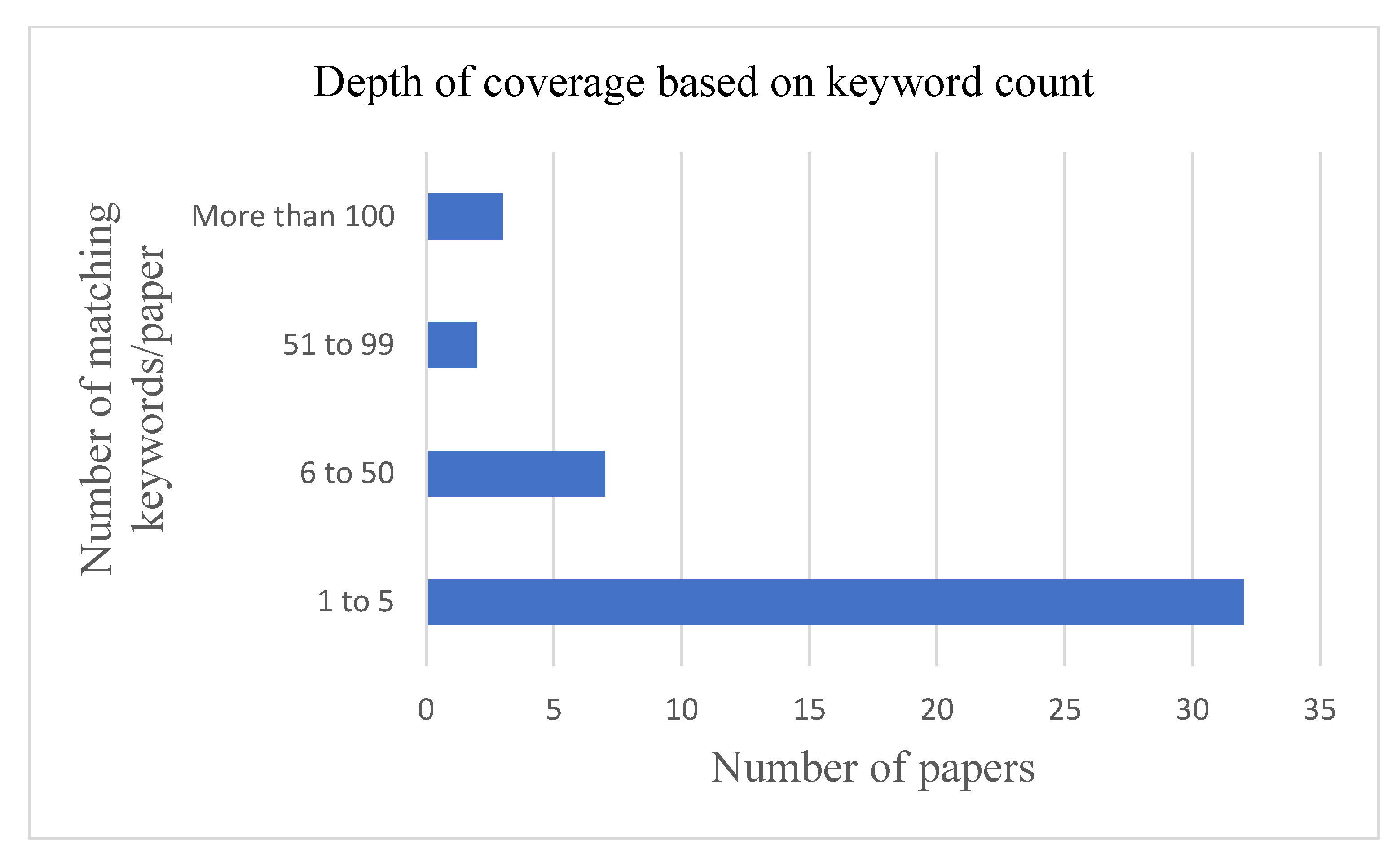

4.1. Depth of Coverage of Commons in the KM Literature

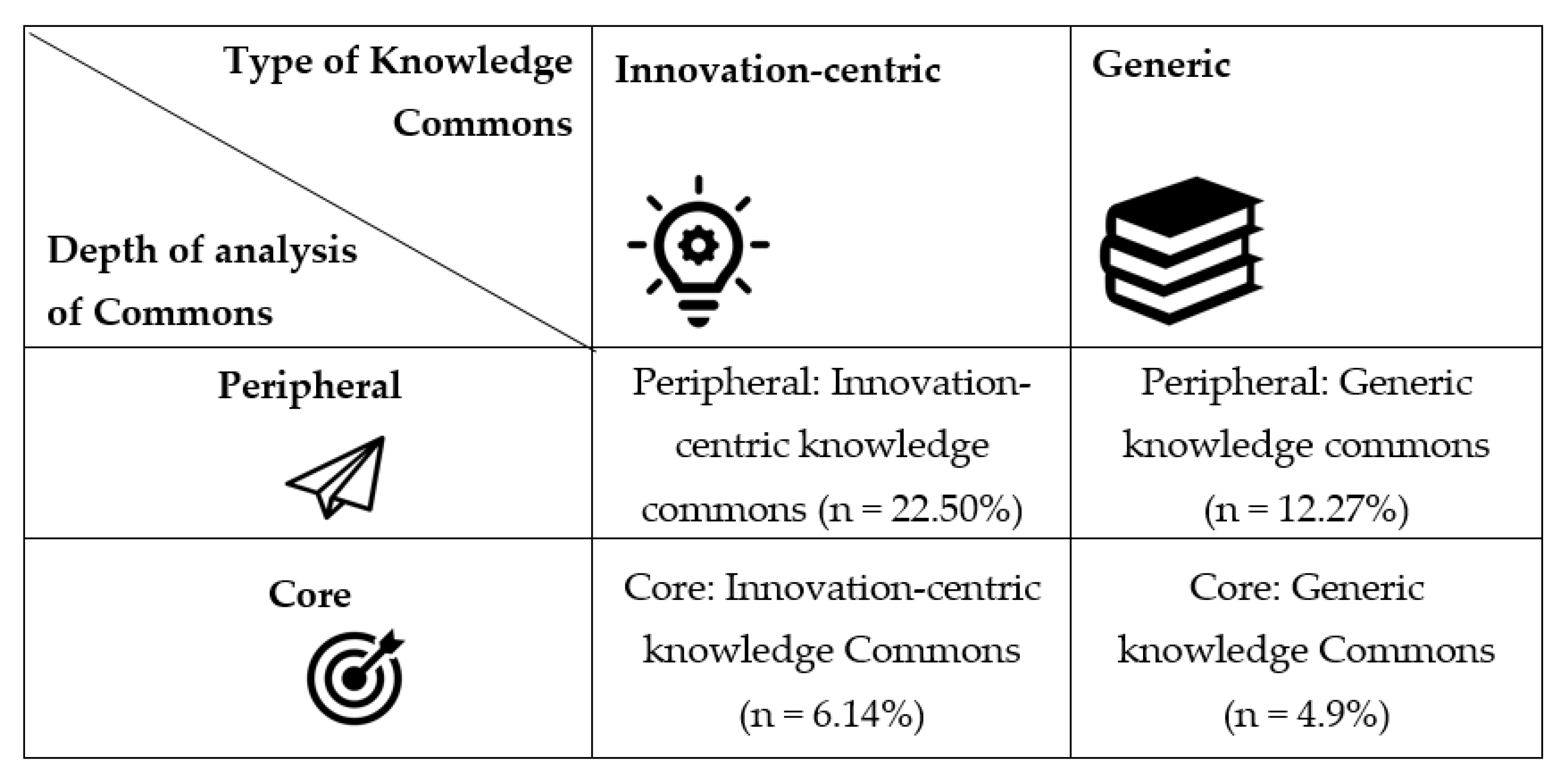

4.2. Literature Mapping

4.3. Core: Innovation-Centric Knowledge Commons

4.4. Core: Generic Knowledge Commons

4.5. Peripheral: Innovation-Centric Knowledge Commons

4.6. Core: Generic Knowledge Commons

5. Discussion

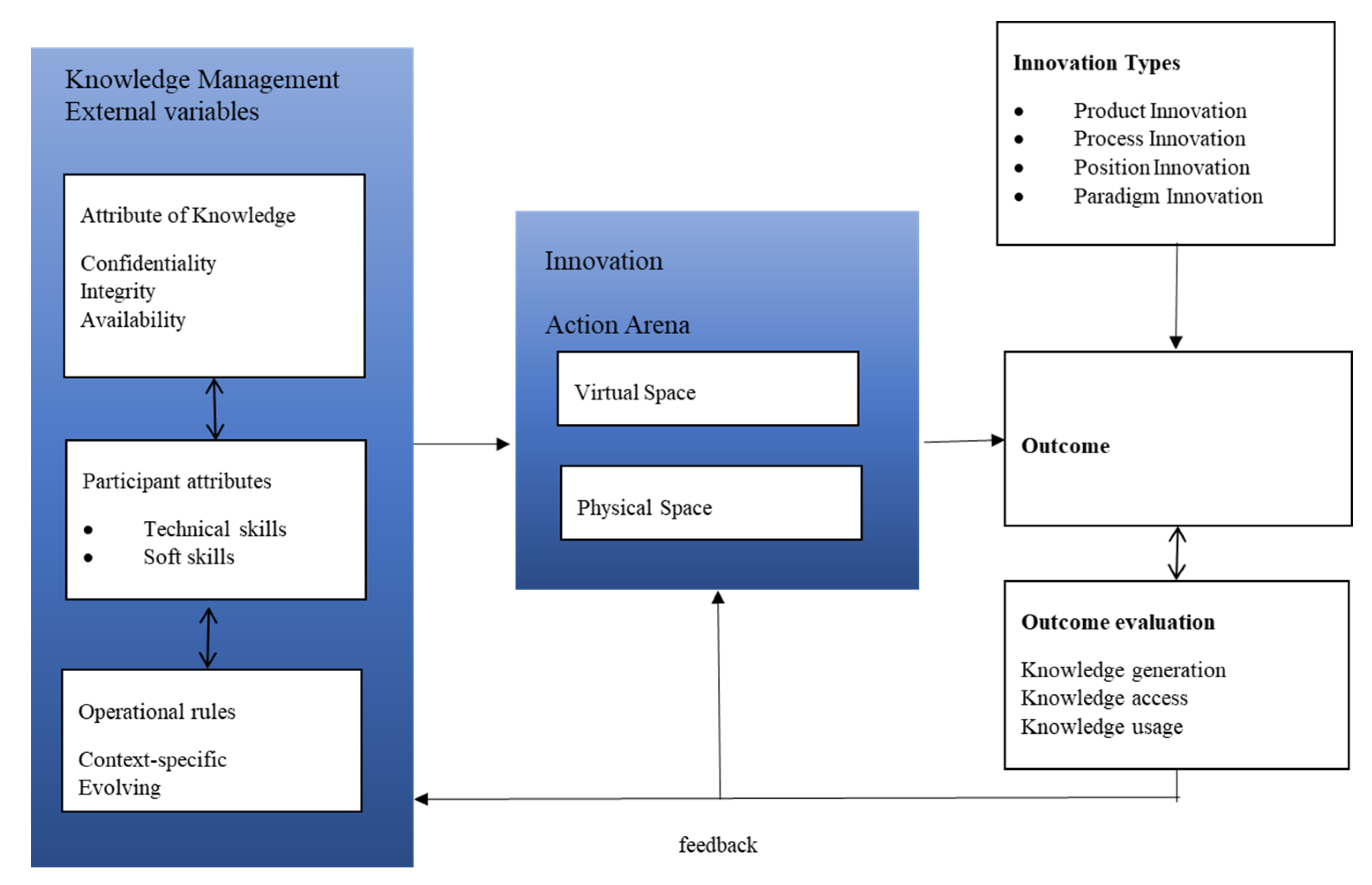

Conceptual Model for Open Innovation Commons

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ferroni, M. World Development Report 1998—Knowledge for Development; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hadad, S. Knowledge economy: Characteristics and dimensions. Manag. Dyn. Knowl. Econ. 2017, 5, 203–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unger, R.M. The Knowledge Economy; Verso Books: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, T. The knowledge economy. Educ. Train. 2001, 43, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H. To recover faster from Covid-19, open up: Managerial implications from an open innovation perspective. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 88, 410–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camisón, C.; Monfort-Mir, V.M. Measuring innovation in tourism from the Schumpeterian and the dynamic-capabilities perspectives. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 776–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śledzik, K. Schumpeter’s View on Innovation and Entrepreneurship. In Management Trends in Theory and Practice; Hittmar, S., Ed.; University of Zilina: Zilina, Slovakia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Schumpeter, J.A. The Theory of Economic Development, 7th ed.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, D.; Potts, J. How innovation commons contribute to discovering and developing new technologies. Int. J. Commons 2016, 10, 1035–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potts, J. Innovation Commons: The Origin of Economic Growth; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Acharya, R.; Gundi, M.; Ngo, T.; Pandey, N.; Patel, S.K.; Pinchoff, J.; Rampal, S.; Saggurti, N.; Santhya, K.; White, C. COVID-19-Related Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices among Adolescents and Young People in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, India; The Population Council, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Du Plessis, M. The role of knowledge management in innovation. J. Knowl. Manag. 2007, 11, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.; Al-Hakim, L.A.Y. The relationships among critical success factors of knowledge management, innovation and organizational performance: A conceptual framework. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Management and Artificial Intelligence, Bali, Indonesia, 1–3 April 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Taherparvar, N.; Esmaeilpour, R.; Dostar, M. Customer knowledge management, innovation capability and business performance: A case study of the banking industry. J. Knowl. Manag. 2014, 18, 591–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frischmann, B.M.; Madison, M.J.; Strandburg, K.J. Governing Knowledge Commons; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hardin, G. The tragedy of the commons. Science 1968, 162, 1243–1248. [Google Scholar]

- Laerhoven, F.V.; Ostrom, E. Traditions and Trends in the Study of the Commons. Int. J. Commons 2007, 1, 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Coping with tragedies of the commons. Annu. Rev. Political Sci. 1999, 2, 493–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, C.; Ostrom, E. Understanding Knowledge as a Commons; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; London, England, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough, H. Open innovation: A new paradigm for understanding industrial innovation. In Proceedings of the 10th Anniversary Summer Conference on Dynamics of Industry and Innovation: Organizations, Networks and Systems, Copenhagen, Denmark, 27–29 June 2005; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Forte, A.; Larco, V.; Bruckman, A. Decentralization in Wikipedia Governance. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2009, 26, 49–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safner, R. Institutional entrepreneurship, wikipedia, and the opportunity of the commons. J. Inst. Econ. 2016, 12, 743–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viégas, F.B.; Wattenberg, M.; McKeon, M.M. The hidden order of Wikipedia. In International Conference on Online Communities and Social Computing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 445–454. [Google Scholar]

- Santoro, G.; Vrontis, D.; Thrassou, A.; Dezi, L.J.T.F.; Change, S. The Internet of Things: Building a knowledge management system for open innovation and knowledge management capacity. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2018, 136, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.J.; Jung, W.; Yang, J. Knowledge strategy and business model conditions for sustainable growth of SMEs. J. Sci. Technol. Policy Manag. 2015, 6, 246–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.J.; Zhao, X.; Park, K.; Shi, L. Sustainability Condition of Open Innovation: Dynamic Growth of Alibaba from SME to Large Enterprise. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, P. Regionally asymmetric knowledge capabilities and open innovation: Exploring ‘Globalisation 2’—A new model of industry organisation. Res. Policy 2005, 34, 1128–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.J.; Won, D.; Jeong, E.; Park, K.; Lee, D.; Yigitcanlar, T. Dismantling of the inverted U-curve of open innovation. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchenham, B.; Brereton, O.P.; Budgen, D.; Turner, M.; Bailey, J.; Linkman, S. Systematic literature reviews in software engineering–a systematic literature review. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2009, 51, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a Methodology for Developing Evidence-Informed Management Knowledge by Means of Systematic Review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, H.M. Organizing knowledge syntheses: A taxonomy of literature reviews. Knowl. Soc. 1988, 1, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serenko, A.; Bontis, N. Global ranking of knowledge management and intellectual capital academic journals: 2017 update. J. Knowl. Manag. 2017, 21, 675–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocke, J.v.; Simons, A.; Niehaves, B.; Niehaves, B.; Reimer, K.; Plattfaut, R.; Cleven, A. Reconstructing the Giant: On the Importance of Rigour in Documenting the Literature Search Process. In Proceedings of the 17th European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS), Verona, Italy, 8–10 June 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, W.H. Information sources and indicators for the assessment of journal reputation and impact. Ref. Libr. 2016, 57, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, F.J. Capital systems: Implications for a global knowledge agenda. J. Knowl. Manag. 2002, 6, 379–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazeley, P.; Jackson, K. Qualitative Data Analysis with NVivo; Sage Publications Limited: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Syed, R.; Collins-Thompson, K. Optimizing Search Results for Educational Goals: Incorporating Keyword Density as a Retrieval Objective. In Proceedings of the SIGIR 2016, Pisa, Italy, 17–21 July 2016; Available online: http://ceur-ws.org/Vol-1647/SAL2016_paper_21.pdf (accessed on 4 June 2020).

- Orlandi, L.B.; Ricciardi, F.; Rossignoli, C.; De Marco, M. Scholarly work in the Internet age: Co-evolving technologies, institutions and workflows. J. Innov. Knowl. 2019, 4, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, F.; Cantino, V.; Rossignoli, C. Organisational learning for the common good: An emerging model. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2019, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, C.C.; Choi, C.J. Development and knowledge resources: A conceptual analysis. J. Knowl. Manag. 2010, 14, 759–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S. Evolution and future of the knowledge commons: Emerging opportunities and challenges for less developed societies. Knowl. Manag. Dev. J. 2012, 8, 141–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corazza, L.; Cisi, M.; Dumay, J. Formal networks: The influence of social learning in meta-organisations from commons protection to commons governance. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2019, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Costa, R.; Ribeiro-Navarrete, S. Paradoxical effects of local regulation practices on common resources: Evidence from spatial econometrics. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2019, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mas-Tur, A.; Roig-Tierno, N.; Ribeiro-Navarrete, B. Successful entrepreneurial learning: Success factors of adaptive governance of the commons. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2019, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantino, V.; Devalle, A.; Cortese, D.; Ricciardi, F.; Longo, M. Place-based network organizations and embedded entrepreneurial learning. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2017, 23, 504–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bernardi, P.; Bertello, A.; Venuti, F.; Zardini, A. Knowledge transfer driving community-based business models towards sustainable food-related behaviours: A commons perspective. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2019, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dameri, R.P.; Moggi, S. Emerging business models for the cultural commons. Empirical evidence from creative cultural firms. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2019, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, F.; Stern, S. Do formal intellectual property rights hinder the free flow of scientific knowledge?: An empirical test of the anti-commons hypothesis. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2007, 63, 648–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zeebroeck, N.; De La Potterie, B.V.P.; Guellec, D. Patents and academic research: A state of the art. J. Intellect. Cap. 2008, 9, 246–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Chou, P.; Passerini, K. Intellectual property rights and knowledge sharing across countries. J. Knowl. Manag. 2009, 13, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, S.; Regeer, B.J.; Ho, W.W.; Zweekhorst, M.B. Proposing a fifth generation of knowledge management for development: Investigating convergence between knowledge management for development and transdisciplinary research. Knowl. Manag. Dev. J. 2013, 9, 10–36. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, U. The Austrian national knowledge report. J. Knowl. Manag. 2007, 11, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.S.; Ng, E.W.; Dharmawirya, M.; Lee, C.K. Beyond the digital divide: A conceptual framework for analyzing knowledge societies. J. Knowl. Manag. 2008, 12, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R. Narratives of knowledge and intelligence… beyond the tacit and explicit. J. Knowl. Manag. 2006, 10, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R. The epistemology of knowledge and the knowledge process cycle: Beyond the “objectivist” vs “interpretivist”. J. Knowl. Manag. 2008, 12, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebisi, E.M.; Arua, G.N. Knowledge Management in Libraries in the 21st Century. J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. 2018, 9, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, A.; Attahir, I.S. Innovative and creative skills for the 21st Century librarian: Benefits and challenges in Nigerian academic libraries. J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. 2018, 9, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Attahir, I.S. Digital literacy: Survival skill for librarians in the Digital Era. J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. 2018, 9, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, F.J. Capital cities: A taxonomy of capital accounts for knowledge cities. J. Knowl. Manag. 2004, 8, 28–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, K.A.; Taibah, A.A. Knowledge cities through ‘open design studio’educational projects: The case study of Jeddah City. Int. J. Knowl. Based Dev. 2011, 2, 295–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P.; Choi, C.J.; Chen, S.; Eldomiaty, T.I.; Millar, C.C. Knowledge repositories in knowledge cities: Institutions, conventions and knowledge subnetworks. J. Knowl. Manag. 2004, 8, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, A.; Du, K.; Roos, G. The intellectual capital needs of a transitioning economy. J. Intellect. Cap. 2015, 16, 466–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzotto, M.; Corò, G.; Volpe, M. Territorial capital as a company intangible. J. Intellect. Cap. 2016, 17, 148–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evers, H.D.; Gerke, S.; Menkhoff, T. Knowledge clusters and knowledge hubs: Designing epistemic landscapes for development. J. Knowl. Manag. 2010, 14, 678–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, N.; Cardone, R.; de Moor, A. Learning 3.0: Collaborating for impact in large development organizations. Knowl. Manag. Dev. J. 2014, 10, 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Meloche, J.A.; Hasan, H.; Willis, D.; Pfaff, C.C.; Qi, Y. Cocreating corporate knowledge with a Wiki. Int. J. Knowl. Manag. 2009, 5, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Martinez, J.M.G.; de Castro-Pardo, M.; Pérez-Rodríguez, F.; Martín, J.M.M. Innovation and multi-level knowledge transfer using a multi-criteria decision making method for the planning of protected areas. J. Innov. Knowl. 2019, 4, 256–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.S.; Bhattacharya, S. Knowledge dilemmas within organizations: Resolutions from game theory. Knowl. Based Syst. 2013, 45, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Ding, C.; Xia, C. Impact of individual difference and investment heterogeneity on the collective cooperation in the spatial public goods game. Knowl. Based Syst. 2017, 136, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambe, P. The unacknowledged parentage of knowledge management. J. Knowl. Manag. 2011, 15, 175–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, L.; Holsapple, C.W. Understanding computer-mediated interorganizational collaboration: A model and framework. J. Knowl. Manag. 2005, 9, 53–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäkimattila, M.; Saunila, M.; Salminen, J. Interaction and innovation-reframing innovation activities for a matrix organization. Interdiscip. J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. 2014, 9, 131–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, A.; Porter, T. Sustainability, complexity and learning: Insights from complex systems approaches. Learn. Organ. 2011, 18, 54–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, P. Explaining and developing social capital for knowledge management purposes. J. Knowl. Manag. 2010, 14, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z. Knowledge, knowing, knower: What is to be managed and does it matter? Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2008, 6, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.Y.Y.; Edvinsson, L. National intellectual capital: Comparison of the Nordic countries. J. Intellect. Cap. 2008, 9, 525–545. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, P.A. Elements of Organizational Sustainability. Learn. Organ. 2011, 18, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razmerita, L.; Kirchner, K.; Nielsen, P. What factors influence knowledge sharing in organizations? A social dilemma perspective of social media communication. J. Knowl. Manag. 2016, 20, 1225–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, C.J.; Cheng, P.; Hilton, B.; Russell, E. Knowledge governance. J. Knowl. Manag. 2005, 9, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, P.H. Knowledge sharing: Moving away from the obsession with best practices. J. Knowl. Manag. 2007, 11, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Mahoney, J.T. Appropriating economic rents from resources: An integrative property rights and resource-based approach. Int. J. Learn. Intellect. Cap. 2007, 4, 11–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeung, C.-W.; Yoon, H.J.; Choi, M. Exploring the affective mechanism linking perceived organizational support and knowledge sharing intention: A moderated mediation model. J. Knowl. Manag. 2017, 21, 946–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E.; Ahn, T.-K. The meaning of social capital and its link to collective action. In Handbook of Social Capital; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2009; pp. 17–35. [Google Scholar]

- Soroos, M.S. Garrett Hardin and tragedies of global commons. In Handbook of Global Environmental Politics; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2005; pp. 35–50. [Google Scholar]

- Wall, D. The Sustainable Economics of Elinor Ostrom: Commons, Contestation and Craft; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. An Assessment of the Institutional Analysis and Development Framework; Theories of the Policy Process: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 35–72. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Background on the institutional analysis and development framework. Policy Stud. J. 2011, 39, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H. The future of open innovation: The future of open innovation is more extensive, more collaborative, and more engaged with a wider variety of participants. Res. Technol. Manag. 2017, 60, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, K. Understanding decentralized forest governance: An application of the institutional analysis and development framework. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2006, 2, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imperial, M.T. Institutional analysis and ecosystem-based management: The institutional analysis and development framework. Environ. Manag. 1999, 24, 449–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clement, F. Analysing decentralised natural resource governance: Proposition for a “politicised” institutional analysis and development framework. Policy Sci. 2010, 43, 129–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allarakhia, M.; Walsh, S. Analyzing and organizing nanotechnology development: Application of the institutional analysis development framework to nanotechnology consortia. Technovation 2012, 32, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darroch, J.; McNaughton, R. Examining the link between knowledge management practices and types of innovation. J. Intellect. Cap. 2002, 3, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, J.; Baregheh, A.; Sambrook, S. Towards an Innovation-Type Mapping Tool. Manag. Decis. 2011, 49, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeley, L.; Walters, H.; Pikkel, R.; Quinn, B. Ten Types of Innovation: The Discipline of Building Breakthroughs; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, J.J.; Liu, Z. Micro-and macro-dynamics of open innovation with a quadruple-helix model. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No | Journal Name and Publisher | SCImago Quartile 2019 | Quality Tier [33] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Journal of Innovation and Knowledge (Elsevier) | Q1 | Not Assessed |

| 2 | Knowledge-Based Systems (Elsevier) | Q1 | Not Assessed |

| 3 | Journal of Knowledge Management (Emerald) | Q1 | A+ |

| 4 | Journal of Intellectual Capital (Emerald) | Q1 | A+ |

| 5 | Learning Organization (Emerald) | Q2 | A |

| 6 | Knowledge Management Research and Practice (Palgrave Macmillan) | Q2 | A |

| 7 | Knowledge and Process Management: The Journal of Corporate Transformation (Wiley) | Q3 | A |

| 8 | VINE: Journal of Information and Knowledge Management Systems (Emerald) | Q2 | A |

| 9 | International Journal of Knowledge Management (IGI) | Q3 | A |

| 10 | Journal of Information and Knowledge Management (World Scientific) | Q3 | B |

| 11 | International Journal of Learning and Intellectual Capital (Inderscience) | Q3 | B |

| 12 | International Journal of Knowledge and Learning (Inderscience) | Q4 | B |

| 13 | Electronic Journal of Knowledge Management (Academic Conferences and Publishing International) | Q3 | B |

| 14 | International Journal of Knowledge Management Studies (Inderscience) | Q3 | B |

| 15 | Interdisciplinary Journal of Information, Knowledge, and Management (Informing Science) | Q3 | B |

| 16 | International Journal of Knowledge-Based Development (Inderscience) | Q2 | B |

| 17 | Knowledge Management and E-Learning: An International Journal (University of Hong Kong) | Q4 | B |

| 18 | International Journal of Knowledge-Based Organizations (IGI) | Not Assessed | B |

| 19 | International Journal of Knowledge, Culture, and Change Management: Annual Review (Common Ground Publishing) | Q4 | B |

| 20 | International Journal of Knowledge and Systems Science (IGI) | Q3 | B |

| 21 | Knowledge Management for Development Journal (Foundation for the Support of KM4DJ) | Not Assessed | B |

| Commons Type | References | Title |

|---|---|---|

| Core: Innovation-Centric Knowledge Commons (n = 6) | ||

| Academic Commons | [39] | Scholarly work in the Internet age: Co-evolving technologies, institutions and workflows |

| Commons-Generic | [40] | Organizational learning for the common good: an emerging model |

| Tragedy of Commons | [41] | Development and knowledge resources: a conceptual analysis |

| Knowledge Management for development | [42] | Evolution and future of the knowledge commons: emerging opportunities and challenges for less developed societies |

| Knowledge Commons-Development | [52] | Proposing a fifth generation of knowledge management for development: investigating convergence between knowledge management for development and transdisciplinary research |

| Commons-Generic | [43] | Formal networks: the influence of social learning in meta-organizations from commons protection to commons governance |

| Core: Generic Knowledge Commons (n = 4) | ||

| Commons-Generic | [44] | Paradoxical effects of local regulation practices on common resources: evidence from spatial econometrics |

| Commons-Generic | [45] | Successful entrepreneurial learning: success factors of adaptive governance of the commons |

| AFN Commons | [47] | Knowledge transfer driving community-based business models towards sustainable food-related behaviours: A commons perspective |

| Cultural Commons | [48] | Emerging business models for the cultural commons. Empirical evidence from creative cultural firms |

| Peripheral: Innovation-Centric Knowledge Commons (n = 22) | ||

| Industrial Commons | [63] | The intellectual capital needs of a transitioning economy |

| Intellectual Commons | [57] | Knowledge Management in Libraries in the 21st Century |

| Knowledge Commons | [71] | The unacknowledged parentage of knowledge management |

| Knowledge Commons-Cities | [62] | Knowledge repositories in knowledge cities: institutions, conventions and knowledge subnetworks |

| Knowledge Commons-Cities | [61] | Knowledge cities through “open design studio” educational projects: the case study of Jeddah City |

| Commons-Generic | [72] | Understanding computer-mediated inter-organizational collaboration: a model and framework |

| Commons-Generic | [65] | Knowledge clusters and knowledge hubs: designing epistemic landscapes for development |

| Commons-Generic | [73] | Interaction and innovation-reframing innovation activities for a matrix organization |

| Learning Commons | [58] | Innovative and creative skills for the 21st Century librarian: benefits and challenges in Nigerian academic libraries |

| Scientific anti-commons | [50] | Patents and academic research: a state of the art |

| Commons-Generic | [66] | Learning 3.0: collaborating for impact in large development organizations |

| Tragedy of Commons | [74] | Sustainability, complexity and learning: insights from complex systems approaches |

| Tragedy of Commons | [75] | Explaining and developing social capital for knowledge management purposes |

| Creative Commons | [53] | The Austrian national knowledge report |

| Creative Commons | [54] | Beyond the digital divide: a conceptual framework for analyzing knowledge societies |

| Creative Commons | [55] | Narratives of knowledge and intelligence… beyond the tacit and explicit |

| Creative Commons | [56] | The epistemology of knowledge and the knowledge process cycle: beyond the “objectivist” vs. “interpretivist” |

| Tragedy of Commons | [76] | Knowledge, knowing, knower: what is to be managed and does it matter? |

| Global Commons | [36] | Capital systems: implications for a global knowledge agenda |

| Global Commons | [77] | National intellectual capital: comparison of the Nordic countries |

| Industrial Commons | [64] | Territorial capital as a company intangible |

| Industrial Commons | [51] | Intellectual property rights and knowledge sharing across countries |

| Peripheral: Generic Knowledge Commons (n = 12) | ||

| Tragedy of Commons | [70] | Impact of individual difference and investment heterogeneity on the collective cooperation in the spatial public goods game |

| Learning Commons | [59] | Digital literacy: Survival skill for librarians in the Digital Era |

| Tragedy of Commons | [69] | Knowledge dilemmas within organizations: Resolutions from game theory |

| Commons-Generic | [68] | Innovation and multi-level knowledge transfer using a multi-criteria decision-making method for the planning of protected areas |

| Tragedy of Commons | [78] | Elements of organizational sustainability |

| Knowledge Commons-Cities | [60] | Capital cities: a taxonomy of capital accounts for knowledge cities |

| Tragedy of Commons | [79] | What factors influence knowledge sharing in organizations? A social dilemma perspective of social media communication |

| Commons-Generic | [80] | Knowledge governance |

| Tragedy of Commons | [81] | Knowledge sharing: moving away from the obsession with best practices |

| Information Commons | [67] | Cocreating corporate knowledge with a Wiki |

| Tragedy of Commons | [82] | Appropriating economic rents from resources: an integrative property rights and resource-based approach |

| Tragedy of Commons | [83] | Exploring the affective mechanism linking perceived organizational support and knowledge sharing intention: a moderated mediation model |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ramakrishnan, M.; Shrestha, A.; Soar, J. Innovation Centric Knowledge Commons—A Systematic Literature Review and Conceptual Model. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc7010035

Ramakrishnan M, Shrestha A, Soar J. Innovation Centric Knowledge Commons—A Systematic Literature Review and Conceptual Model. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity. 2021; 7(1):35. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc7010035

Chicago/Turabian StyleRamakrishnan, Muralidharan, Anup Shrestha, and Jeffrey Soar. 2021. "Innovation Centric Knowledge Commons—A Systematic Literature Review and Conceptual Model" Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 7, no. 1: 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc7010035

APA StyleRamakrishnan, M., Shrestha, A., & Soar, J. (2021). Innovation Centric Knowledge Commons—A Systematic Literature Review and Conceptual Model. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 7(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc7010035