The KAC-CSR Model in the Tourism Sector

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Methodology

3.1. Sampling and Data Collection

3.2. Data Analysis

4. Results

5. Discussion

- (i)

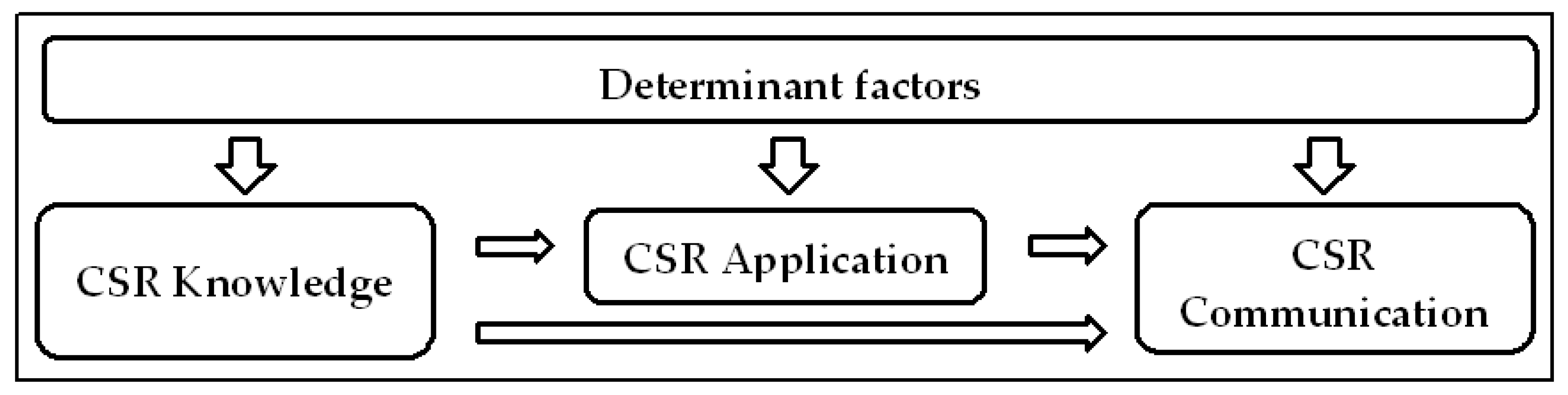

- The characteristics of hotels related to size, age, category, type of contract, financial performance, and the level of investment in innovation influence the levels of CSR knowledge and CSR application. In the case of CSR communication, only size has an influence. In this respect, managers will have to bear in mind that the levels of knowledge and application will increase as the hotel increases its size (application), acquires experience (knowledge and application), improves its category (application), and importantly always maintains good levels of financial performance (knowledge and application) and investment in innovation (knowledge and application). Likewise, the types of hotel contracts that are leased or franchised would improve the degree of knowledge and application. In turn, the levels of communication will increase as the size of the hotel increases.

- (ii)

- With regard to the characteristics related to the manager, decisions aimed at having higher levels of CSR knowledge and CSR application will involve having a relatively young person in the management (application), preferably a woman (knowledge and application), with university studies (knowledge and application), ideally with a postgraduate degree (knowledge and application) and with autonomy for decision making in the area of CSR (application). It is important to remember that these characteristics are not influential in CSR communication.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Font, X.; Lynes, J. Corporate social responsibility in tourism and hospitality. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1027–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moneva, J.; Bonilla-Priego, M.; Ortas, E. Corporate social responsibility and organisational performance in the tourism sector. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 853–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achmad, W.; Yulianah, Y. Corporate social responsibility of the hospitality industry in realizing sustainable tourism development. Jour. of Manag. 2022, 12, 1610–1616. [Google Scholar]

- Paskova, M.; Zelenka, J. How crucial is the social responsibility for tourism sustainability? Soc. Responsib. J. 2019, 15, 534–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peña, D. Responsabilidad Social Empresarial en el Sector Turístico; ECOE Ediciones–Editorial Unimagdalena: Bogotá, Colombia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mihalic, T. Sustainable-responsible tourism discourse–Towards ‘responsustable’ tourism. J. Clean Prod. 2016, 111, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bhatta, K.; Gautam, P.; Tanaka, T. Travel Motivation during COVID-19: A Case from Nepal. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seabra, C.; Bhatt, K. Tourism Sustainability and COVID-19 Pandemic: Is There a Positive Side? Sustainability 2022, 14, 8723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupi, M.; Szemerédi, E. Impact of the COVID-19 on the Destination Choices of Hungarian Tourists: A Comparative Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Travel & Tourism Council-WTTC. Travel & Tourism Economic Impact 2021: Global Economic Impact & Trends 2021; WTTC: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, M.; Choi, Y. Employee perceptions of hotel CSR activities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Cont. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 3355–3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davahli, M.R.; Karwowski, W.; Sonmez, S.; Apostolopoulos, Y. The hospitality industry in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic: Current topics and research methods. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Chi, C.G. Effects of COVID-19 pandemic on hospitality industry: Review of the current situations and a research agenda. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2020, 29, 527–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johann, M. CSR strategy in the hospitality industry: From the COVID-19 pandemic crisis to recovery. Int. J. Cont. Manag. 2022; online first. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johann, M. CSR Strategy in Tourism during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Sharma, A.; Nicolau, J.L.; Kang, J. The impact of hotel CSR for strategic philanthropy on booking behavior and hotel performance during the COVID-19 pandemic. Tour. Manag. 2021, 85, 104322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitfield, J.; Dioko, L. Measuring and Examining the Relevance of Discretionary Corporate Social Responsibility in Tourism: Some Preliminary Evidence from the U.K. Conference Sector. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Rodríguez, M.; Martín-Samper, R.; Ali Köseoglu, M.; Okumus, F. Hotels’ corporate social responsibility practices, organizational culture, firm reputation, and performance. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 398–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilufya, A.; Hughes, E.; Scheyvens, R. Tourists and community development: Corporate social responsibility or tourist social responsibility? J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1513–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiddi, F.E.; Ibenrissoul, A. Mapping 20 Years of Literature on CSR in Tourism Industry: A Bibliometric Analysis. Am. J. of Ind. Bus. Manag. 2020, 10, 1739–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Law, R.; Wei, J.; Li, X. Progress of hotel corporate social responsibility research in terms of theoretical, methodological, and thematic development. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2021, 30, 717–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M. Strategic corporate social responsibility in tourism and hospitality. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 504–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wells, V.; Gregory, D.; Taheri, B.; Manika, D.; McCowlen, K. An exploration of CSR development in heritage tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 58, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, P.; Park, S. An Exploratory Study of Corporate Social Responsibility in the U.S. Travel Industry. J. Travel Res. 2011, 50, 392–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Serra, A.; Peña, D.; Ramón, J.; Martorell, O. Progress in research on CSR and the hotel industry (2006–2015). Corn. Hosp. Quart. 2018, 59, 15–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Votaw, D. ; Sethi. The Corporate Dilemma: Traditional Values versus Contemporary Problems; Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera, J.; de las Heras-Rosas, C. Corporate social responsibility and human resource management: Towards sustainable business organizations. Sustainability 2020, 12, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ettinger, A.; Grabner-Kräuter, S.; Okazaki, S.; Terlutter, R. The Desirability of CSR Communication versus Greenhushing in the Hospitality Industry: The Customers’ Perspective. J. Travel Res. 2020, 60, 618–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostepaniuk, A.; Nasr, E.; Awwad, R.I.; Hamdan, S.; Aljuhmani, H.Y. Managing a Relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainability: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Camacho, C.; Carranza, R.; Martín-Consuegra, D.; Díaz, E. Evolution, trends and future research lines in corporate social responsibility and tourism: A bibliometric analysis and science mapping. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 30, 462–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garriga, E.; Melé, D. Corporate social responsibility theories: Mapping the territory. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 53, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argandoña, A.; Hoivik, H. Corporate social responsibility: One size does not fit all. Collecting evidence from Europe. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 89, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sprinkle, G.; Maines, L. The benefits and costs of corporate social responsibility. Bus. Horiz. 2010, 53, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusyk, S.; Lozano, J.M. Corporate responsibility in small and medium-sized enterprises SME social performance: A four-cell typology of key drivers and barriers on social issues and their implications for stakeholder theory. Corp. Gov. 2007, 7, 502–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, S.; Caroli, M.G.; Cappa, F.; Del Chiappa, G. Are you good enough? CSR, quality management and corporate financial performance in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 88, 102395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Singh, N. Do Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) initiatives boost customer retention in the hotel industry? A moderation-mediation approach. J. Hospit. Mark. Manag. 2021, 30, 459–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, O.; Islam, J. Effect of CSR activities on meaningfulness, compassion, and employee engagement: A sense-making theoretical approach. Int. J. of Hosp. Manag. 2020, 90, 102630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, O.; Islam, J.; Rahman, Z. Effect of CSR participation on employee sense of purpose and experienced meaningfulness: A self-determination theory perspective. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 46, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardona, D.; Hernández, J. La Responsabilidad Social Empresarial desde la perspectiva de los Gerentes de los hoteles pymes de la ciudad de Cartagena. Sab. Cienc. Y Lib. 2011, 6, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martínez, P.; Pérez, A.; Rodríguez Del Bosque, I. Responsabilidad Social Corporativa: Definición y práctica en el sector hotelero. El caso de Meliá Hotels. Rev. Responsab. Soc. Emp. 2013, 13, 141–173. [Google Scholar]

- Melo, T.; Cox Moura-Leite, R.; Carlton Padgett, R. Conceptualization of corporate social responsibility by the luxury hotels in Natal/RN, Brazil. Cad. Virt. De Tur. 2012, 12, 152–166. [Google Scholar]

- Tepelus, C.M. Destination Unknown? The Emergence of Corporate Social Responsibility for Sustainable Development of Tourism. Doctoral Dissertation, Lund University, Lund, Sweden, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, A.; Tsutsui, K. Globalization and commitment in corporate social responsibility: Cross-national analyses of institutional and political-economy effects. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2012, 77, 69–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atehortúa, F. Responsabilidad social empresarial: Entre la ética discursiva y la racionalidad técnica. Rev. EAN 2008, 62, 125–140. [Google Scholar]

- Bohdanowicz, P.; Zientara, P. Hotel companies’ contribution to improving the quality of life of local communities and the well-being of their employees. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2009, 9, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garay, L.; Font, X. Motivaciones, prácticas y resultados del comportamiento responsable en las pequeñas y medianas empresas turísticas. Rev. De Responsab. Soc. De La Empresa 2013, 13, 51–84. [Google Scholar]

- Khunon, S.; Muangasame, K. The differences between local and international chain hotels in CSR management: Empirical findings from a case study in Thailand. Asian Soc. Sci. 2013, 9, 209–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, G.; Xu, H. Impact of Lifestyle-Oriented Motivation on Small Tourism Enterprises’ Social Responsibility and Performance. J. Travel Res. 2019, 58, 1146–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Levy, S.E.; Park, S.-Y. An analysis of CSR activities in the lodging industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2011, 18, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W.; Hsu, L.; Chen, C.; Lin, W.; Chen, S. An integrated approach for selecting corporate social responsibility programs and costs evaluation in the international tourist hotel. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 29, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elijido-Ten, E.; Kloot, L.; Clarkson, P. Extending the application of stakeholder influence strategies to environmental disclosure. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2010, 23, 1032–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingaard, T. Creating a corporate responsibility culture. The approach of Unilever UK. In Corporate Social Responsibility. Reconciling Aspiration with Application; Kakabadse, A., Morsing, M., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2006; pp. 86–104. [Google Scholar]

- Llull, A. Contabilidad Medioambiental y Desarrollo Sostenible en el Sector Turístico. Doctoral Dissertation, University of the Balearic Islands, Palma, Spain, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Van Wijk, J.; Persoon, W. A Long-haul Destination: Sustainability Reporting among Tour Operators. Europ. Manag. J. 2006, 24, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Draft National Review Report CSR for All Croatia; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2013.

- Jeppesen, S.; Kothuis, B.; Ngoc Tran, A. Corporate Social Responsibility and Competitiveness for SMEs in Developing Countries: South Africa and Vietnam; French Development Agency: Paris, France, 2012.

- Wijesinghe, K.N. Current context of disclosure of corporate social responsibility in Sri Lanka. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2012, 2, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peña-Miranda, D.D.; Arteaga-Ortiz, J.; Ramón-Cardona, J. Determinants of CSR application in the hotel industry of the Colombian Caribbean. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luque, T. Técnicas de Análisis de Datos en Investigación de Mercados; Pirámide: Madrid, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Céspedes, J.J.; Sánchez, M. Tendencias y desarrollos recientes en métodos de investigación y análisis de datos en dirección de empresas. Rev. Eur. De Dir. Y Econ. De La Empresa 1996, 5, 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Garrido, A. La Gestión de Relaciones con Clientes (CRM) Como Estrategia de Negocio: Desarrollo de un Modelo de Éxito y Análisis Empírico en el Sector Hotelero Español. Doctoral Dissertation, Malaga University, Malaga, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Vergara, C.; Quesada, V.; Blanco, I. Análisis de la calidad en el servicio y satisfacción de los usuarios en dos hoteles cinco estrellas de la ciudad de Cartagena (Colombia) mediante un modelo de ecuaciones estructurales. Ingeniare Rev. Chil. De Ing. 2011, 19, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bigné, E.; Currás, R. ¿Influye la imagen de responsabilidad social en la intención de compra? El papel de la identificación del consumidor con la empresa. Universia Bus. Rev. 2008, 19, 10–23. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, A.; García, M.; Rodríguez, I. Las dimensiones de la Responsabilidad Social de las Empresas como determinantes de las intenciones de comportamiento del consumidor. RAE Rev. Astur. De Econ. 2008, 41, 127–147. [Google Scholar]

- Tziner, A.; Bar, Y.; Oren, L.; Kadosh, G. Corporate social responsibility, organizational justice and job satisfaction: How do they interrelate, if at all? Rev. De Psicol. Del Trab. Y De Las Organ. 2011, 27, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, Y. Examining the Role of Corporate Social Responsibility in Resident Attitude Formation: A Missing Link? J. Travel Res. 2019, 58, 1105–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Análisis Multivariante; Prentice Hall: Madrid, Spain, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, M.; Pardo, A.; San Martín, R. Modelos de ecuaciones estructurales. Pap. Del Psicólogo 2010, 31, 34–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Will, S. SmartPLS 2.0 (Beta); SmartPLS: Hamburg, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W.; Marcolin, B.L.; Newsted, P.R. A partial least squares latent variable modeling approach for measuring interaction effects: Results from a Monte Carlo simulation study and an electronic mail emotion/adoption study. Inf. Syst. Res. 2003, 14, 189–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reinartz, W.; Haenlein, M.; Henseler, J. An empirical comparison of the efficacy of covariance-based and variance-based SEM. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2009, 26, 332–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassel, C.M.; Hackl, P.; Westlund, A.H. On measurement of intangible assets: A Study of robustness of Partial Least Squares. Total Qual. Manag. 1999, 11, 897–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The Use of Partial Least Squares Path Modeling in International Marketing. In Advances in International Marketing; Sinkovics, R.R., Ghauri, P.N., Eds.; Emerald: Bingley, UK, 2009; pp. 277–320. [Google Scholar]

- Carmines, E.G.; Zeller, R.A. Reliability and Validity Assessment, N. 07–017; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach, L. Essentials of Psychological Testing, 3rd ed.; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Werts, C.E.; Linn, R.L.; Joreskog, K.G. Interclass reliability estimates: Testing structural assumptions. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1974, 34, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Teoría Psicométrica; Trillas: Ciudad de México, México, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. Issues and opinions on structural equation modeling. MIS Q. 1998, 22, 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Davison, A.C.; Hinkley, D.V. Bootstrap Methods and Their Application; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Camisón, C.; Forés, B.; Boronat-Navarro, M.; Puig-Denia, A. The effect of hotel chain affiliation on economic performance: The moderating role of tourist districts. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 87, e102493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melissen, F.; van Ginneken, R.; Wood, R.C. Sustainability challenges and opportunities arising from the owner-operator split in hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 54, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, X.; McCabe, S. Sustainability and marketing in tourism: Its contexts, paradoxes, approaches, challenges and potential. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 869–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Font, X.; Elgammal, I.; Lamond, I. Greenhushing: The deliberate under communicating of sustainability practices by tourism businesses. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 1007–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nicolau, J. Corporate Social Responsibility. Worth-Creating Activities. Ann. Tour. Res. 2008, 35, 990–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- García, F.; Armas, Y. Aproximación a la Incidencia de la Responsabilidad Social-Medioambiental en el rendimiento económico de la empresa hotelera española. Rev. Eur. De Dir. Y Econ. De La Empresa 2007, 16, 47–66. [Google Scholar]

- Calveras, A.; Ganuza, J. Corporate social responsibility and product quality. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 2018, 27, 804–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eme, J.E.; Obal, U.E.U.; Inyang, O.I.; Effiong, C. Corporate social responsibility in small and medium scale enterprises in Nigeria: An example from the hotel industry. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2013, 8, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gao, Y.; Mattila, A. Improving consumer satisfaction in green hotels: The roles of perceived warmth, perceived competence, and CSR motive. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 42, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhou, Y.; Singal, M. A review of the business case for CSR in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 84, e102330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M.A. Advancing the sustainable tourism agenda through strategic CSR perspectives. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2014, 11, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruana, R.; Glozer, S.; Crane, A.; McCabe, S. Tourists’ accounts of responsible tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 46, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmaki, A.; Farmakis, P. A stakeholder approach to CSR in hotels. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 68, 58–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Description |

|---|---|

| BAS-KNOW | Basic CSR knowledge: the main social responsibility of the company revolves around compliance with the economic requirements stipulated by the shareholders |

| ADV-KNOW | Advanced CSR knowledge: CSR is involved with the sustainable development of society |

| ECO-ACT(M/C) | CSR economic activities related to market/competitiveness |

| ECO-ACT(STR) | CSR economic activities related to CSR strategy |

| SOC-ACT(LAB) | CSR social activities related to labor conditions and respect for the local community |

| SOC-ACT(P/S) | CSR social activities related to policy, social action plans and disability |

| ENV-ACT(EA) | CSR environmental activities/environmental actions |

| COMMUNIC. | CSR communication |

| MOTIVATION | Motivations related to the values and the management style, the competitiveness and the image of the hotel, and the pressure from the stakeholders |

| OBSTACLE | Obstacles related to management attitude and style, lack of knowledge and shortage of resources (financial, time, and human), and government support |

| W-000/010 | Hotel with <10 workers |

| W-010/051 | Hotel with 10–50 workers |

| W-051/200 | Hotel with 51–200 workers |

| W-200/MORE | Hotel with >200 workers |

| (00–10) YEARS | Time of operation of the hotel <10 years |

| (10–20) YEARS | Time of operation of the hotel 10–20 years |

| (21–40) YEARS | Time of operation of the hotel 21–40 years |

| (>40) YEARS | Time of operation of the hotel >40 years |

| 0-STARS-H | Hotel without stars |

| 1-STARS-H | Hotel with 1 star |

| 2-STARS-H | Hotel with 2 stars |

| 3-STARS-H | Hotel with 3 stars |

| 4-STARS-H | Hotel with 4 stars |

| 5-STARS-H | Hotel with 5 stars |

| OWNED-H | Hotel owned |

| RENTED-H | Rented hotel |

| FRANCH.-H | Franchised hotel |

| MANAG.-H | Hotel under management |

| POOR-FIN | Poor hotel financial performance |

| REGU-FIN | Regular hotel financial performance |

| GOOD-FIN | Good hotel financial performance |

| POOR-INV | Poor hotel level of investment in innovation |

| REGU-INV | Regular hotel level of investment in innovation |

| GOOD-INV | Good hotel level of investment in innovation |

| MALE | Male gender of the director |

| FEMALE | Female gender of the director |

| (<40) MANAG | Manager <40 years old |

| 40/60 MANAG | Manager 40–60 years old |

| (>60) MANAG | Manager >60 years old |

| UNDERGRAD | Manager with an undergraduate degree |

| POSTGRAD | Manager with a postgraduate degree |

| AUTONOMY | Director’s autonomy for CSR decision making |

| CUSTOMER | Customer pressure for CSR communication |

| COMMUNITY | Local community pressure for CSR communication |

| SUPPLIER | Pressure from trade partners and suppliers for CSR communication |

| COMPETITOR | Pressure from competitors for CSR communication |

| GOVERNMENT | Pressure from government for CSR communication |

| Population (N) | 506 Hotels |

|---|---|

| Geographical scope | Colombian Caribbean region (Barranquilla, Santa Marta, and Cartagena) |

| Confidence interval, as well as error and proportions (p and q) predefined to calculate the sample size | 95.5–5% (with p = q = 0.5) |

| Sample size (n) | 224 hotels |

| Sample unit | Hotel |

| Respondent | Hotel managers |

| Response rate | 99.11% (222 hotels) |

| Sampling error obtained from the response rate with a confidence interval and predefined proportions (p and q) | 95.5–0.64% (with p = q = 0.5) |

| AVE | Composite Reliability | R2 | Cronbach’s Alpha | Redundancy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ENV-ACT(EA) | 0.794 | 0.972 | 0.634 | 0.967 | 0.049 |

| ECO-ACT(STR) | 0.801 | 0.924 | 0.691 | 0.876 | 0.205 |

| ECO-ACT(M/C) | 0.748 | 0.954 | 0.678 | 0.944 | 0.020 |

| SOC-ACT(LAB) | 0.793 | 0.950 | 0.761 | 0.933 | 0.114 |

| SOC-ACT(P/S) | 0.701 | 0.903 | 0.731 | 0.857 | 0.039 |

| ADV-KNOW | 0.850 | 0.944 | 0.627 | 0.912 | 0.199 |

| BAS-KNOW | 0.782 | 0.915 | 0.104 | 0.862 | 0.026 |

| MOTIVATION | 0.706 | 0.878 | 0.831 | ||

| OBSTACLE | 0.802 | 0.924 | 0.875 |

| ENV-ACT(EA) | ECO-ACT(STR) | ECO-ACT(M/C) | SOC-ACT(LAB) | SOC-ACT(P/S) | ADV-KNOW | BAS-KNOW | MOTIVATION | OBSTACLE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ENV-ACT/01 | 0.926 | 0.596 | 0.538 | 0.623 | 0.714 | 0.543 | −0.052 | 0.401 | −0.630 |

| ENV-ACT/02 | 0.923 | 0.611 | 0.485 | 0.568 | 0.699 | 0.507 | −0.054 | 0.383 | −0.638 |

| ENV-ACT/03 | 0.905 | 0.536 | 0.585 | 0.688 | 0.655 | 0.552 | −0.081 | 0.432 | −0.619 |

| ENV-ACT/04 | 0.897 | 0.586 | 0.468 | 0.543 | 0.675 | 0.504 | 0.005 | 0.398 | −0.565 |

| ENV-ACT/05 | 0.894 | 0.535 | 0.544 | 0.673 | 0.635 | 0.539 | −0.074 | 0.455 | −0.599 |

| ENV-ACT/06 | 0.891 | 0.536 | 0.436 | 0.510 | 0.668 | 0.468 | 0.075 | 0.344 | −0.521 |

| ENV-ACT/07 | 0.886 | 0.551 | 0.596 | 0.705 | 0.612 | 0.589 | −0.118 | 0.503 | −0.617 |

| ENV-ACT/08 | 0.885 | 0.528 | 0.602 | 0.714 | 0.631 | 0.572 | −0.085 | 0.448 | −0.625 |

| ENV-ACT/09 | 0.811 | 0.662 | 0.439 | 0.563 | 0.627 | 0.456 | −0.138 | 0.367 | −0.605 |

| ECO-ACT/01 | 0.540 | 0.918 | 0.594 | 0.620 | 0.751 | 0.589 | −0.317 | 0.565 | −0.634 |

| ECO-ACT/02 | 0.597 | 0.901 | 0.493 | 0.544 | 0.746 | 0.518 | −0.172 | 0.459 | −0.550 |

| ECO-ACT/03 | 0.588 | 0.867 | 0.523 | 0.588 | 0.660 | 0.605 | −0.216 | 0.454 | −0.654 |

| ECO-ACT/04 | 0.566 | 0.550 | 0.918 | 0.829 | 0.603 | 0.574 | −0.141 | 0.624 | −0.564 |

| ECO-ACT/05 | 0.574 | 0.612 | 0.905 | 0.821 | 0.623 | 0.635 | −0.208 | 0.613 | −0.676 |

| ECO-ACT/06 | 0.554 | 0.588 | 0.885 | 0.791 | 0.601 | 0.561 | −0.197 | 0.559 | −0.597 |

| ECO-ACT/07 | 0.534 | 0.582 | 0.880 | 0.771 | 0.592 | 0.586 | −0.122 | 0.546 | −0.651 |

| ECO-ACT/08 | 0.521 | 0.468 | 0.870 | 0.722 | 0.565 | 0.554 | −0.079 | 0.580 | −0.521 |

| ECO-ACT/09 | 0.394 | 0.371 | 0.804 | 0.568 | 0.451 | 0.426 | −0.083 | 0.463 | −0.414 |

| ECO-ACT/10 | 0.350 | 0.413 | 0.782 | 0.526 | 0.412 | 0.443 | −0.102 | 0.406 | −0.521 |

| SOC-ACT/01 | 0.678 | 0.599 | 0.772 | 0.946 | 0.686 | 0.650 | −0.174 | 0.595 | −0.642 |

| SOC-ACT/02 | 0.674 | 0.613 | 0.732 | 0.944 | 0.667 | 0.654 | −0.156 | 0.600 | −0.660 |

| SOC-ACT/03 | 0.566 | 0.580 | 0.707 | 0.912 | 0.634 | 0.629 | −0.153 | 0.586 | −0.657 |

| SOC-ACT/04 | 0.675 | 0.608 | 0.742 | 0.850 | 0.700 | 0.559 | −0.168 | 0.586 | −0.626 |

| SOC-ACT/05 | 0.495 | 0.494 | 0.601 | 0.789 | 0.483 | 0.510 | −0.174 | 0.491 | −0.626 |

| SOC-ACT/06 | 0.671 | 0.773 | 0.655 | 0.715 | 0.884 | 0.602 | −0.205 | 0.528 | −0.679 |

| SOC-ACT/07 | 0.590 | 0.825 | 0.551 | 0.611 | 0.854 | 0.557 | −0.186 | 0.529 | −0.561 |

| SOC-ACT/08 | 0.672 | 0.583 | 0.502 | 0.608 | 0.852 | 0.559 | −0.052 | 0.373 | −0.541 |

| SOC-ACT/09 | 0.530 | 0.487 | 0.426 | 0.441 | 0.753 | 0.430 | −0.088 | 0.312 | −0.417 |

| ADV-KNOW/1 | 0.567 | 0.653 | 0.674 | 0.711 | 0.644 | 0.966 | −0.049 | 0.523 | −0.658 |

| ADV-KNOW/2 | 0.598 | 0.670 | 0.623 | 0.675 | 0.662 | 0.949 | −0.109 | 0.491 | −0.679 |

| ADV-KNOW/3 | 0.450 | 0.388 | 0.410 | 0.445 | 0.448 | 0.847 | 0.232 | 0.361 | −0.384 |

| BAS-KNOW/1 | −0.110 | −0.279 | −0.122 | −0.147 | −0.181 | −0.005 | 0.915 | −0.097 | 0.259 |

| BAS-KNOW/2 | 0.015 | −0.204 | −0.178 | −0.196 | −0.103 | −0.017 | 0.914 | −0.143 | 0.273 |

| BAS-KNOW/3 | −0.077 | −0.199 | −0.116 | −0.148 | −0.139 | 0.047 | 0.809 | −0.112 | 0.243 |

| MOTIVATION/1 | 0.620 | 0.668 | 0.700 | 0.760 | 0.646 | 0.664 | −0.101 | 0.889 | −0.685 |

| MOTIVATION/2 | 0.149 | 0.238 | 0.362 | 0.308 | 0.237 | 0.163 | −0.124 | 0.817 | −0.158 |

| MOTIVATION/3 | 0.121 | 0.242 | 0.345 | 0.300 | 0.200 | 0.152 | −0.125 | 0.812 | −0.133 |

| OBSTACLE/1 | −0.667 | −0.645 | −0.644 | −0.693 | −0.645 | −0.600 | 0.274 | −0.461 | 0.950 |

| OBSTACLE/2 | −0.646 | −0.618 | −0.511 | −0.582 | −0.619 | −0.537 | 0.261 | −0.417 | 0.890 |

| OBSTACLE/3 | −0.496 | −0.568 | −0.610 | −0.660 | −0.512 | −0.584 | 0.249 | −0.500 | 0.843 |

| ENV-ACT(EA) | ECO-ACT(STR) | ECO-ACT(M/C) | SOC-ACT(LAB) | SOC-ACT(P/S) | ADV-KNOW | BAS-KNOW | MOTIVATION | OBSTACLE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ENV-ACT(EA) | 1.000 | ||||||||

| ECO-ACT(STR) | 0.641 | 1.000 | |||||||

| ECO-ACT(M/C) | 0.584 | 0.599 | 1.000 | ||||||

| SOC-ACT(LAB) | 0.698 | 0.652 | 0.841 | 1.000 | |||||

| SOC-ACT(P/S) | 0.738 | 0.806 | 0.642 | 0.717 | 1.000 | ||||

| ADV-KNOW | 0.590 | 0.637 | 0.632 | 0.678 | 0.646 | 1.000 | |||

| BAS-KNOW | −0.066 | −0.261 | −0.156 | −0.185 | −0.162 | 0.004 | 1.000 | ||

| MOTIVATION | 0.465 | 0.551 | 0.632 | 0.644 | 0.526 | 0.505 | −0.132 | 1.000 | |

| OBSTACLE | −0.676 | −0.682 | −0.656 | −0.720 | −0.663 | −0.642 | 0.292 | −0.511 | 1.000 |

| 0.891 | 0.895 | 0.865 | 0.890 | 0.837 | 0.922 | 0.884 | 0.840 | 0.895 |

| Item | Abbreviation | Loading |

|---|---|---|

| CSR Environmental Activities: | ||

| We have an established environmental policy and plan. | ENV-ACT/01 | 0.926 |

| We have identified our environmental impacts and carry out concrete actions to minimize them. | ENV-ACT/02 | 0.923 |

| We carry out environmental awareness and training campaigns for stakeholders. | ENV-ACT/03 | 0.905 |

| We have a concrete strategy to tackle climate change. | ENV-ACT/04 | 0.897 |

| We have programs or systems for the reduction, recycling, separation, and/or treatment of waste. | ENV-ACT/05 | 0.894 |

| We have an environmental certificate or we are in the process of certification. | ENV-ACT/06 | 0.891 |

| We have programs or systems for saving energy, water, paper, etc. | ENV-ACT/07 | 0.886 |

| We promote among the clients the care and protection of the destination environment. | ENV-ACT/08 | 0.885 |

| We introduce environmental aspects in the criteria for purchasing and selecting suppliers and business partners. | ENV-ACT/09 | 0.811 |

| CSR Economic Activities (CSR Strategy): | ||

| CSR is integrated into my business strategy (mission, vision, values, policy, and strategic plan). | ECO-ACT/01 | 0.918 |

| We are attached to some international, national, regional, or local CSR initiatives. | ECO-ACT/02 | 0.901 |

| We introduce aspects of social responsibility in the purchasing criteria. | ECO-ACT/03 | 0.867 |

| CSR Economic Activities (Market): | ||

| We pay a decent and fair wage to the workers. | ECO-ACT/04 | 0.918 |

| We encourage customers to use and consume local products and services. | ECO-ACT/05 | 0.905 |

| We hire local personnel at the different levels of hierarchical responsibility of the company. | ECO-ACT/06 | 0.885 |

| We contract local suppliers. | ECO-ACT/07 | 0.880 |

| We know the needs, expectations, and satisfaction of customers. | ECO-ACT/08 | 0.870 |

| We care about providing high-quality products at competitive prices. | ECO-ACT/09 | 0.804 |

| We give clients complete, transparent, and honest information about the commercial offer. | ECO-ACT/10 | 0.782 |

| CSR Social Activities (Labor/Community): | ||

| We have labor flexibility policies that allow family reconciliation. | SOC-ACT/01 | 0.946 |

| We promote the training and professional development of employees. | SOC-ACT/02 | 0.944 |

| We take special care of the health and wellbeing of workers. | SOC-ACT/03 | 0.912 |

| We promote respect for local heritage, values, culture, and language in our clients. | SOC-ACT/04 | 0.850 |

| We promote gender equality in all organizational processes. | SOC-ACT/05 | 0.789 |

| CSR Social Activities (Policy and Social Plan): | ||

| We collaborate directly and/or indirectly in social projects of local communities. | SOC-ACT/06 | 0.884 |

| We have an established policy and social action plan. | SOC-ACT/07 | 0.854 |

| Our facilities are adapted for people with disabilities. | SOC-ACT/08 | 0.852 |

| We have hired people with some kind of disability. | SOC-ACT/09 | 0.753 |

| Advanced CSR Knowledge: | ||

| CSR refers to integrating the triple economic–social–environmental sphere into the company’s strategy. | ADV-KNOW/1 | 0.966 |

| CSR aims to contribute to the wellbeing and improvement of the quality of life in society. | ADV-KNOW/2 | 0.949 |

| CSR refers to the tactical practices carried out by the company above the legal regulations. | ADV-KNOW/3 | 0.847 |

| Basic CSR Knowledge: | ||

| The main social responsibility of the company is the financial requirements stipulated by the shareholders. | BAS-KNOW/1 | 0.915 |

| CSR deals with philanthropic activities that are not related to the company’s business. | BAS-KNOW/2 | 0.914 |

| CSR is identified with compliance with all legal regulations that affect the company. | BAS-KNOW/3 | 0.809 |

| Motivations: | ||

| My personal values and management style drive me to implement CSR measures. | MOTIVATION/1 | 0.889 |

| CSR improves the competitiveness of my hotel. | MOTIVATION/2 | 0.817 |

| CSR improves the image and reputation of the hotel before all stakeholders. | MOTIVATION/3 | 0.812 |

| Obstacles: | ||

| I am not informed about or do not know how to implement CSR measures. | OBSTACLE/1 | 0.950 |

| We do not have the resources to implement CSR activities. | OBSTACLE/2 | 0.890 |

| My attitude and management style do not allow CSR to be integrated into the business. | OBSTACLE/3 | 0.843 |

| Causal Relationship Analyzed | Path Coefficients | Standard Deviation | Standard Error | T Student |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAS-KNOW → ECO-ACT(M/C) (H1.1) | −0.057 * | 0.024 | 0.024 | 2.389 |

| BAS-KNOW → ECO-ACT(STR) (H1.2) | −0.141 *** | 0.024 | 0.024 | 5.866 |

| BAS-KNOW → SOC-ACT(LAB) (H1.3) | −0.075 *** | 0.021 | 0.021 | 3.675 |

| BAS-KNOW → SOC-ACT(P/S) (H1.4) | −0.143 *** | 0.025 | 0.025 | 5.711 |

| ADV-KNOW → ECO-ACT(M/C) (H3.1) | 0.109 *** | 0.027 | 0.027 | 4.057 |

| ADV-KNOW → ECO-ACT(STR) (H3.2) | 0.249 *** | 0.030 | 0.030 | 8.333 |

| ADV-KNOW → SOC-ACT(LAB) (H3.3) | 0.115 *** | 0.029 | 0.029 | 3.996 |

| ADV-KNOW → SOC-ACT(P/S) (H3.4) | 0.150 *** | 0.033 | 0.033 | 4.521 |

| MOTIVATION → ECO-ACT(M/C) (H5.1) | 0.263 *** | 0.024 | 0.024 | 10.869 |

| MOTIVATION → ECO-ACT(STR) (H5.2) | 0.115 *** | 0.022 | 0.022 | 5.182 |

| MOTIVATION → SOC-ACT(LAB) (H5.3) | 0.196 *** | 0.028 | 0.028 | 7.079 |

| OBSTACLE → ECO-ACT(M/C) (H6.1) | −0.229 *** | 0.029 | 0.029 | 7.776 |

| OBSTACLE → ECO-ACT(STR) (H6.2) | −0.238 *** | 0.032 | 0.032 | 7.470 |

| OBSTACLE → SOC-ACT(LAB) (H6.3) | −0.256 *** | 0.033 | 0.033 | 7.782 |

| OBSTACLE → SOC-ACT(P/S) (H6.4) | −0.085 * | 0.041 | 0.041 | 2.101 |

| OBSTACLE → ENV-ACT(EA) (H6.5) | −0.315 *** | 0.037 | 0.037 | 8.626 |

| ECO-ACT(STR) → COMMUNIC. (H7.2) | 0.266 *** | 0.037 | 0.037 | 7.136 |

| SOC-ACT(LAB) → COMMUNIC. (H7.3) | 0.071 ** | 0.027 | 0.027 | 2.664 |

| SOC-ACT(P/S) → COMMUNIC. (H7.4) | 0.439 *** | 0.048 | 0.048 | 9.198 |

| ENV-ACT(EA) → COMMUNIC. (H7.5) | 0.212 *** | 0.035 | 0.035 | 6.135 |

| Causal Relationship Analyzed | Path Coefficients | Standard Deviation | Standard Error | T Student |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic CSR Knowledge: | ||||

| RENTED-H → BAS-KNOW | −0.197 *** | 0.038 | 0.038 | 5.192 |

| (00–10)YEARS → BAS-KNOW | 0.329 *** | 0.081 | 0.081 | 4.077 |

| (10–20)YEARS → BAS-KNOW | 0.271 *** | 0.071 | 0.071 | 3.812 |

| (21–40)YEARS → BAS-KNOW | 0.209 ** | 0.067 | 0.067 | 3.116 |

| FEMALE → BAS-KNOW | −0.166 *** | 0.030 | 0.030 | 5.498 |

| POSTGRAD → BAS-KNOW | −0.143 *** | 0.032 | 0.032 | 4.426 |

| Advanced CSR Knowledge: | ||||

| POOR-FIN → ADV-KNOW | −0.399 *** | 0.050 | 0.050 | 7.929 |

| REGU-FIN → ADV-KNOW | −0.464 *** | 0.041 | 0.041 | 11.436 |

| UNDERGRAD → ADV-KNOW | 0.209 *** | 0.032 | 0.032 | 6.600 |

| POSTGRAD → ADV-KNOW | 0.320 *** | 0.049 | 0.049 | 6.511 |

| POOR-INV → ADV-KNOW | −0.115 ** | 0.045 | 0.045 | 2.582 |

| CSR Economic Activities (Market): | ||||

| AUTONOMY → ECO-ACT(M/C) | 0.098 *** | 0.022 | 0.022 | 4.406 |

| UNDERGRAD → ECO-ACT(M/C) | 0.058 * | 0.023 | 0.023 | 2.511 |

| (00–10)YEARS → ECO-ACT(M/C) | −0.162 *** | 0.024 | 0.024 | 6.666 |

| (10–20)YEARS → ECO-ACT(M/C) | −0.188 *** | 0.025 | 0.025 | 7.492 |

| POOR-INV → ECO-ACT(M/C) | −0.326 *** | 0.038 | 0.038 | 8.613 |

| REGU-INV → ECO-ACT(M/C) | −0.235 *** | 0.024 | 0.024 | 9.752 |

| FEMALE → ECO-ACT(M/C) | 0.139 *** | 0.019 | 0.019 | 7.333 |

| CSR Economic Activities (Strategy): | ||||

| FRANCH.-H → ECO-ACT(STR) | 0.258 *** | 0.028 | 0.028 | 9.287 |

| (<40)MANAG → ECO-ACT(STR) | 0.130 *** | 0.028 | 0.028 | 4.567 |

| REGU-FIN → ECO-ACT(STR) | −0.045 * | 0.021 | 0.021 | 2.188 |

| (00–10)YEARS → ECO-ACT(STR) | −0.169 *** | 0.049 | 0.049 | 3.434 |

| (10–20)YEARS → ECO-ACT(STR) | −0.103 * | 0.045 | 0.045 | 2.303 |

| (21–40)YEARS → ECO-ACT(STR) | −0.165 *** | 0.039 | 0.039 | 4.242 |

| FEMALE → ECO-ACT(STR) | 0.082 *** | 0.021 | 0.021 | 3.910 |

| W-000/010 → ECO-ACT(STR) | −0.298 *** | 0.059 | 0.059 | 5.060 |

| W-010/051 → ECO-ACT(STR) | −0.332 *** | 0.052 | 0.052 | 6.357 |

| W-051/200 → ECO-ACT(STR) | −0.206 *** | 0.039 | 0.039 | 5.272 |

| CSR Social Activities (Labor/Community): | ||||

| REGU-FIN → SOC-ACT(LAB) | −0.187 *** | 0.030 | 0.030 | 6.163 |

| (00–10)YEARS → SOC-ACT(LAB) | −0.143 *** | 0.020 | 0.020 | 7.191 |

| (10–20)YEARS → SOC-ACT(LAB) | −0.194 *** | 0.021 | 0.021 | 9.180 |

| POOR-INV → SOC-ACT(LAB) | −0.261 *** | 0.035 | 0.035 | 7.456 |

| REGU-INV → SOC-ACT(LAB) | −0.199 *** | 0.030 | 0.030 | 6.729 |

| POSTGRAD → SOC-ACT(LAB) | 0.198 *** | 0.034 | 0.034 | 5.876 |

| CSR Social Activities (Policy and Social): | ||||

| 5-STARS-H → SOC-ACT(P/S) | 0.067 ** | 0.026 | 0.026 | 2.633 |

| FRANCH.-H → SOC-ACT(P/S) | 0.121 *** | 0.022 | 0.022 | 5.415 |

| POOR-INV → SOC-ACT(P/S) | −0.106 *** | 0.021 | 0.021 | 5.124 |

| FEMALE → SOC-ACT(P/S) | 0.148 *** | 0.020 | 0.020 | 7.350 |

| POSTGRAD → SOC-ACT(P/S) | 0.323 *** | 0.037 | 0.037 | 8.774 |

| W-000/010 → SOC-ACT(P/S) | −0.592 *** | 0.052 | 0.052 | 11.462 |

| W-010/051 → SOC-ACT(P/S) | −0.466 *** | 0.046 | 0.046 | 10.111 |

| W-051/200 → SOC-ACT(P/S) | −0.167 *** | 0.031 | 0.031 | 5.408 |

| CSR Environmental Activities: | ||||

| 0-STARS-H → ENV-ACT(EA) | −0.143 *** | 0.028 | 0.028 | 5.127 |

| 2-STARS-H → ENV-ACT(EA) | −0.133 *** | 0.030 | 0.030 | 4.463 |

| POOR-INV → ENV-ACT(EA) | −0.204 *** | 0.052 | 0.052 | 3.923 |

| REGU-INV → ENV-ACT(EA) | −0.183 *** | 0.038 | 0.038 | 4.845 |

| FEMALE → ENV-ACT(EA) | 0.044 * | 0.020 | 0.020 | 2.157 |

| POSTGRAD → ENV-ACT(EA) | 0.235 *** | 0.043 | 0.043 | 5.418 |

| CSR Communication: | ||||

| GOVERNMENT → COMMUNIC. | 0.114 *** | 0.019 | 0.019 | 5.908 |

| W-000/010 → COMMUNIC. | −0.051 * | 0.022 | 0.022 | 2.276 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peña-Miranda, D.D.; Serra-Cantallops, A.; Ramón-Cardona, J. The KAC-CSR Model in the Tourism Sector. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1840. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031840

Peña-Miranda DD, Serra-Cantallops A, Ramón-Cardona J. The KAC-CSR Model in the Tourism Sector. Sustainability. 2023; 15(3):1840. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031840

Chicago/Turabian StylePeña-Miranda, David Daniel, Antoni Serra-Cantallops, and José Ramón-Cardona. 2023. "The KAC-CSR Model in the Tourism Sector" Sustainability 15, no. 3: 1840. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031840

APA StylePeña-Miranda, D. D., Serra-Cantallops, A., & Ramón-Cardona, J. (2023). The KAC-CSR Model in the Tourism Sector. Sustainability, 15(3), 1840. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031840