Silent Burden of Urinary Tract Infections in Intermittent Catheter Users with Neurological Disorders: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Data Extraction and Data Analysis

3. Results

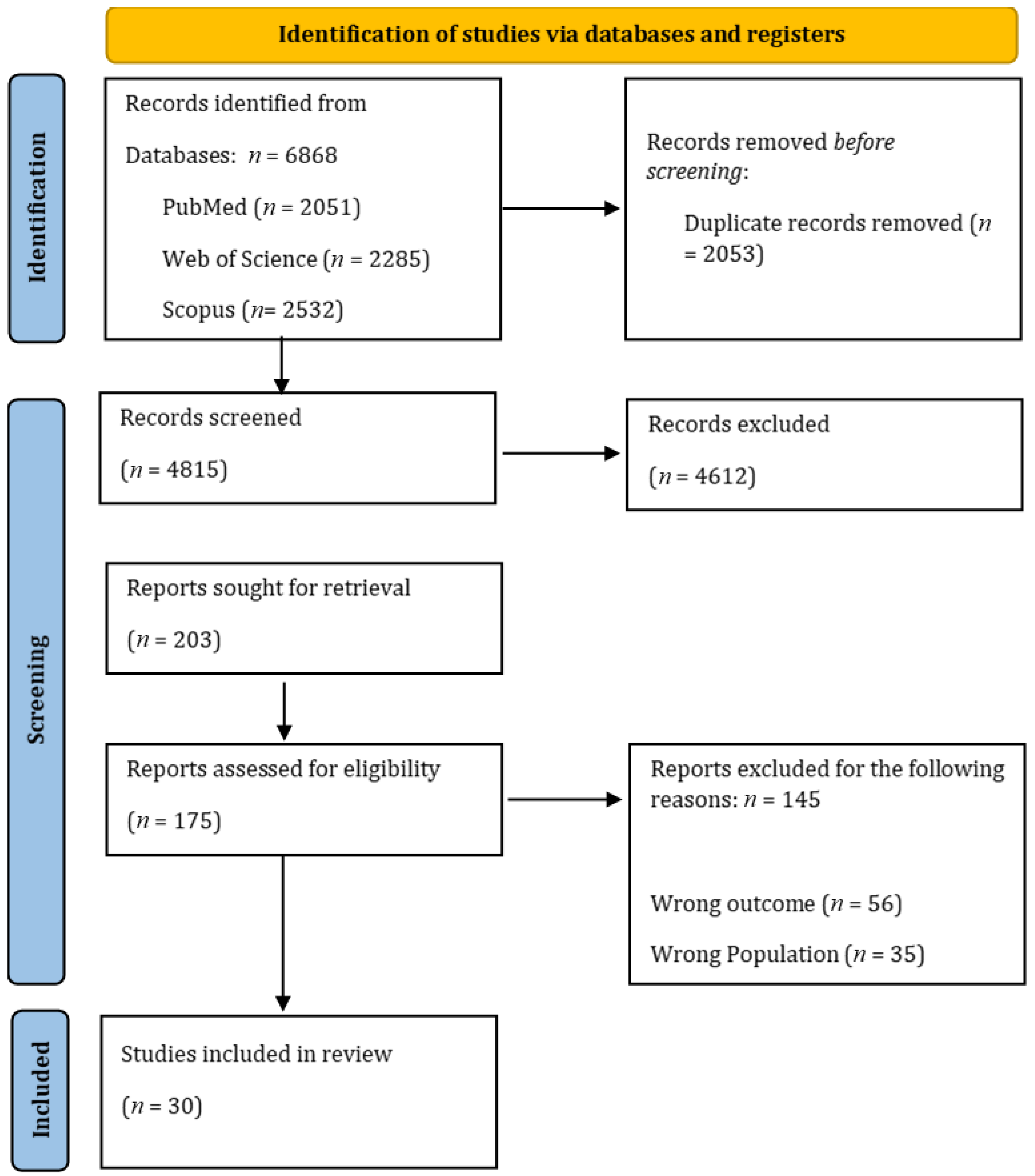

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Epidemiological Burden of UTIs

3.3.1. SCI Patients

3.3.2. Impact of Catheter Type, Hygiene, and Education

3.3.3. Multiple Sclerosis Patients

3.4. Risk Factors

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings of This Study

4.2. What Is Already Known on This Topic

4.3. What This Study Adds

4.4. Strengths and Limitations of This Study

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bolinger, R.; Engberg, S. Barriers, complications, adherence, and self-reported quality of life for people using clean intermittent catheterization. J. Wound Ostomy Cont. Nurs. 2013, 40, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.E.; Birkhäuser, V.; Jordan, X.; Liechti, M.D.; Luca, E.; Möhr, S.; Pannek, J.; Kessler, T.M.; Brinkhof, M.W.G. Urological Management at Discharge from Acute Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation: A Descriptive Analysis from a Popula-tion-Based Prospective Cohort. Eur. Urol. Open Sci. 2022, 38, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yilmaz, B.; Yavuz, F.; Adiguzel, E. Retrospective Analysis of Nosocomial Urinary Tract Infections with Spinal Cord Injury Patients in a Rehabilitation Setting. Türkiye Fiz. Tip. Ve Rehabil. Derg. 2014, 60, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyndaele, J.J.; Maes, D. Clean intermittent self-catheterization: A 12-year followup. J. Urol. 1990, 143, 906–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manack, A.; Motsko, S.P.; Haag-Molkenteller, C.; Dmochowski, R.R.; Goehring, E.L.; Nguyen-Khoa, B.A.; Jones, J.K. Epidemiology and healthcare utilization of neurogenic bladder patients in a US claims database. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2011, 30, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adriaansen, J.J.E.; van Asbeck, F.W.A.; Tepper, M.; Faber, W.X.; Visser-Meily, J.M.A.; de Kort, L.M.O.; Post, M.W.M. Bladder-emptying methods, neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction and impact on quality of life in people with long-term spinal cord injury. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2017, 40, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchter, M.L.; Kjellberg, J.; Ibsen, R.; Sternhufvud, C.; Petersen, B. Burden of illness the first year after diagnosed bladder dysfunction among people with spinal cord injury or multiple sclerosis—A Danish register study. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 2022, 22, 919–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennelly, M.; Thiruchelvam, N.; Averbeck, M.A.; Konstatinidis, C.; Chartier-Kastler, E.; Trøjgaard, P.; Vaabengaard, R.; Krassioukov, A.; Jakobsen, B.P. Adult Neurogenic Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction and Intermittent Catheterisation in a Community Setting: Risk Factors Model for Urinary Tract Infections. Adv. Urol. 2019, 2019, 2757862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, R. State of the Globe: Rising Antimicrobial Resistance of Pathogens in Urinary Tract Infection. J. Glob. Infect. Dis. 2018, 10, 117–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClurg, D.; Bugge, C.; Elders, A.; Irshad, T.; Hagen, S.; Moore, K.N.; Buckley, B.; Fader, M. Factors affecting continuation of clean intermittent catheterisation in people with multiple sclerosis: Results of the COSMOS mixed-methods study. Mult. Scler. J. 2019, 25, 727–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, D.P.; Herrick, J.S.; Stoffel, J.T.; Elliott, S.P.; Lenherr, S.M.; Presson, A.P.; Welk, B.; Jha, A.; Myers, J.B.; Neurogenic Bladder Research Group. Reasons for cessation of clean intermittent catheterization after spinal cord injury: Results from the Neurogenic Bladder Research Group spinal cord injury registry. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2020, 39, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stillman, M.D.; Hoffman, J.M.; Barber, J.K.; Williams, S.R.; Burns, S.P. Urinary tract infections and bladder management over the first year after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. Spinal Cord Ser. Cases 2018, 4, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yıldız, N.; Akkoç, Y.; Erhan, B.; Gündüz, B.; Yılmaz, B.; Alaca, R.; Gök, H.; Köklü, K.; Ersöz, M.; Cınar, E.; et al. Neurogenic bladder in patients with traumatic spinal cord injury: Treatment and follow-up. Spinal Cord 2014, 52, 462–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.F.; Jiang, Y.H.; Jhang, J.F.; Lee, C.L.; Kuo, H.C. Bladder management and urological complications in patients with chronic spinal cord injuries in Taiwan. Tzu Chi Med. J. 2014, 26, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nade, E.S.; Andriessen, M.V.E.; Rimoy, F.; Maendeleo, M.; Saria, V.; Moshi, H.I.; Dekker, M.C.J. Intermittent catheterisation for individuals with disability related to spinal cord injury in Tanzania. Spinal Cord Ser. Cases 2020, 6, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, M.; Ruiz, I.; Squair, J.W.; Rios, L.A.S.; Averbeck, M.A.; Krassioukov, A.V. Prevalence of self-reported complications associated with intermittent catheterization in wheelchair athletes with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2021, 59, 1018–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Luo, C.; Xiao, W.; Xu, T. Urinary tract infections and intermittent catheterization among patients with spinal cord injury in Chinese community. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 17683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekido, N.; Matsuoka, M.; Takahashi, R.; Sengoku, A.; Nomi, M.; Matsuyama, F.; Murata, T.; Kitta, T.; Mitsui, T. Cross-sectional internet survey exploring symptomatic urinary tract infection by type of urinary catheter in persons with spinal cord lesion in Japan. Spinal Cord Ser. Cases 2023, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavinia, S.M.; Omidvar, M.; Farahani, F.; Bayley, M.; Zee, J.; Craven, B.C. Enhancing quality practice for prevention and diagnosis of urinary tract infection during inpatient spinal cord rehabilitation. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2017, 40, 803–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, J.D.; Pariser, J.J.; Stoffel, J.T.; Lenherr, S.M.; Myers, J.B.; Welk, B.; Elliott, S.P. Patient subjective assessment of urinary tract infection frequency and severity is associated with bladder management method in spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2019, 57, 700–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crescenze, I.M.; Myers, J.B.; Lenherr, S.M.; Elliott, S.P.; Welk, B.; Mph, D.O.; Qin, Y.; Presson, A.P.; Stoffel, J.T.; Neurogenic Bladder Research Group. Predictors of low urinary quality of life in spinal cord injury patients on clean intermittent catheterization. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2019, 38, 1332–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.E.; Chamberlain, J.D.; Jordan, X.; Kessler, T.M.; Luca, E.; Möhr, S.; Pannek, J.; Schubert, M.; Brinkhof, M.W.G.; SwiSCI Study Group; et al. Bladder emptying method is the primary determinant of urinary tract infections in patients with spinal cord injury: Results from a prospective rehabilitation cohort study. BJU Int. 2019, 123, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennessey, D.B.; Kinnear, N.; MacLellan, L.; Byrne, C.E.; Gani, J.; Nunn, A.K. The effect of appropriate bladder management on urinary tract infection rate in patients with a new spinal cord injury: A prospective observational study. World J. Urol. 2019, 37, 2183–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neyaz, O.; Srikumar, V.; Equebal, A.; Biswas, A. Change in urodynamic pattern and incidence of urinary tract infection in patients with traumatic spinal cord injury practicing clean self-intermittent catheterization. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2020, 43, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrelly, E.; Lindbo, L.; Wijkström, H.; Seiger, Å. The Stockholm Spinal Cord Uro Study: 2. Urinary tract infections in a regional prevalence group: Frequency, symptoms and treatment strategies. Scand. J. Urol. 2020, 54, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theisen, K.M.; Mann, R.; Roth, J.D.; Pariser, J.J.; Stoffel, J.T.; Lenherr, S.M.; Myers, J.B.; Welk, B.; Elliott, S.P. Frequency of patient-reported UTIs is associated with poor quality of life after spinal cord injury: A prospective observational study. Spinal Cord 2020, 58, 1274–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukai, S.; Shigemura, K.; Nomi, M.; Sengoku, A.; Yamamichi, F.; Fujisawa, M.; Arakawa, S. Retrospective study for risk factors for febrile UTI in spinal cord injury patients with routine concomitant intermittent catheterization in outpatient settings. Spinal Cord 2016, 54, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, H.; Dai, H.; Li, B.; Yuan, X.; Liu, X.; Cui, G.; Liu, N.; Biering-Sørensen, F. Factors associated with urinary tract infection in the early phase after performing intermittent catheterization in individuals with spinal cord injury: A retrospective study. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1257523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabadi, M.H.; Aston, C. Complications and urologic risks of neurogenic bladder in veterans with traumatic spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2015, 53, 200–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, A.; Goldstine, J.; Hofstad, C.; Inglese, G.W.; Kirschner-Hermanns, R.; MacLachlan, S.; Shah, S.; der Hulst, M.V.-V.; Weiss, J. Incidence of urinary tract infection following initiation of intermittent catheterization among patients with recent spinal cord injury in Germany and the Netherlands. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2022, 45, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Cho, M.H.; Do, K.; Kang, H.J.; Mok, J.J.; Kim, M.K.; Kim, G.S. Incidence and risk factors of urinary tract infections in hospitalised patients with spinal cord injury. J. Clin. Nurs. 2021, 30, 2068–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.L. Effects of Quality Control Circle on Patients with Neurogenic Urination Disorder After Spinal Cord Injury and Intermittent Catheterization | Semantic Scholar. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Effects-of-quality-control-circle-on-patients-with-Huang-Hu/7d1c21e7d379c86a9b8fcbc7b7e311746057f346 (accessed on 30 June 2023).

- Milicevic, S.; Sekulic, A.; Nikolic, D.; Tomasevic-Todorovic, S.; Lazarevic, K.; Pelemis, S.; Petrovic, M.; Mitrovic, S.Z. Urinary Tract Infections in Relation to Bladder Emptying in Patients with Spinal Cord Injury. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.; Khan, O.S.; Youssef, A.M.; Saba, I.; Alfedaih, D. Hydrophilic catheters for intermittent catheterization and occurrence of urinary tract infections. A retrospective comparative study in patients with spinal cord Injury. BMC Urol. 2024, 24, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Xie, N.; Wang, J.; An, X.; Yang, T. Effect of Nurse-Led Clean Intermittent Catheterization Synchronous Health Education on Patients with Urinary Dysfunction after Spinal Cord Injury. Arch. Esp. Urol. 2024, 77, 811–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.C.; Tseng, W.C.; Chou, C.L.; Pan, S.L. Complications of different methods of urological management in people with neurogenic bladder secondary to spinal cord injury. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2024, 47, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.F.; Lee, Y.K.; Kuo, H.C. Satisfaction with Urinary Incontinence Treatments in Patients with Chronic Spinal Cord Injury. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 5864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krassioukov, A.; Cragg, J.J.; West, C.; Voss, C.; Krassioukov-Enns, D. The good, the bad and the ugly of catheterization practices among elite athletes with spinal cord injury: A global perspective. Spinal Cord 2015, 53, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.C.; Zeng, S.; Tsai, S.J. Outcome of Different Approaches to Reduce Urinary Tract Infection in Patients With Spinal Cord Lesions: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2020, 99, 1056–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, T.T.; Leonard, G.R.; Cepela, D.J. Classifications In Brief: American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) Impairment Scale. Clin. Orthop. 2017, 475, 1499–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Chen, H.; Zheng, Y.; Qu, S.; Wang, H.; Yi, F. Disease burden and long-term trends of urinary tract infections: A worldwide report. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 888205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginsberg, D.A.; Boone, T.B.; Cameron, A.P.; Gousse, A.; Kaufman, M.R.; Keays, E.; Kennelly, M.J.; Lemack, G.E.; Rovner, E.S.; Souter, L.H.; et al. The AUA/SUFU Guideline on Adult Neurogenic Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction: Diagnosis and Evaluation. J. Urol. 2021, 206, 1097–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groen, J.; Pannek, J.; Castro Diaz, D.; Del Popolo, G.; Gross, T.; Hamid, R.; Karsenty, G.; Kessler, T.M.; Schneider, M.; Hoen, L.T.; et al. Summary of European Association of Urology (EAU) Guidelines on Neuro-Urology. Eur. Urol. 2016, 69, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyndaele, J.J. Intermittent catheterization: Which is the optimal technique? Spinal Cord 2002, 40, 432–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skountrianos, G.; Markiewicz, A.; Goldstine, J.; Nichols, T. WHAT’S INSURANCE GOT TO DO WITH IT: INTERMITTENT CATHETERIZATION PRACTICE. Value Health 2019, 22, S385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faleiros, F.; Toledo, C.; Gomide, M.; Faleiros, R.; Käppler, C. Right to health care and materials required for intermittent catheterization: A comparison between Germany and Brazil. Qual. Prim. Care 2015, 23, 127–133. [Google Scholar]

- Calabrò, G.E.; D’Ambrosio, F.; Orsini, F.; Pappalardo, C.; Scardigno, A.; Rumi, F.; Fiore, A.; Ricciardi, R.; Cicchetti, A. Feasibility study on a new enhanced device for patients with intermittent catheterization (LUJA). J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2023, 64, E1–E89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Arguello, L.Y.; O’Horo, J.C.; Farrell, A.; Blakney, R.; Sohail, M.R.; Evans, C.T.; Safdar, N. Infections in the spinal cord-injured population: A systematic review. Spinal Cord 2017, 55, 526–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Lasquetty Blanc, B.; Hernández Martínez, A.; Lorenzo García, C.; Baixauli Puig, M.; Estudillo González, F.; Martin Bermejo, M.V.; Checa, M.A.O.; Zomeño, E.A.; Bacete, A.T.; Franco, G.F.; et al. Evolution of Quality of Life and Treatment Adherence after One Year of Intermittent Bladder Catheterisation in Functional Urology Unit Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rognoni, C.; Tarricone, R. Healthcare resource consumption for intermittent urinary catheterisation: Cost-effectiveness of hydrophilic catheters and budget impact analyses. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e012360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilsen, M.P.; Jongeneel, R.M.H.; Schneeberger, C.; Platteel, T.N.; van Nieuwkoop, C.; Mody, L.; Caterino, J.M.; Geerlings, S.E.; Köves, B.; Wagenlehner, F.; et al. Definitions of Urinary Tract Infection in Current Research: A Systematic Review. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2024, 10, ofad332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, J.A.; Murphy, C.L.; Stewart, F.; Fader, M. Intermittent catheter techniques, strategies and designs for managing long-term bladder conditions. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, CD006008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P.; RELISHConsortium Zhou, Y. Large expert-curated database for benchmarking document similarity detection in biomedical literature search. Database 2019, 2019, baz085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA. Uncomplicated Urinary Tract Infections: Developing Drugs for Treatment Guidance for Industry—FDA. 2020. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/uncomplicated-urinary-tract-infections-developing-drugs-treatment-guidance-industry (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Evaluation of Medicinal Products Indicated for Treatment of Bacterial Infections—Scientific Guideline | European Medicines Agency. 2024. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/evaluation-medicinal-products-indicated-treatment-bacterial-infections-scientific-guideline (accessed on 5 September 2025).

| P (population): | Adults (≥18 years) with NLUTD due to SCI or MS who use IC. |

| I (intervention): | Intermittent catheterization (particularly clean intermittent catheterization, CIC), and exposure to various user-dependent, technique-related, and catheter-specific factors. |

| C (comparator): | The comparison varies by study and includes the absence of a specific risk factor or the use of an alternative catheterization practice (e.g., single-use vs. reusable, self-IC vs. assisted-IC, and educated caregiver vs. standard care). |

| O (outcomes): |

|

| First Author. Year and Country | Study Design | Underlying Pathology | Target Population | IC Type/Managment | IC Frequency | IC Related Burden of Disease |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen S.F., 2014 Taiwan [15] | Cross-sectional survey | SCI | Clean Intermittent Catheterization (CIC) group: 163 patients (18.2) | CIC/Self-CIC | N.A. | Prevalence of (Patient Reported Urinary Tract Infections) PRUTIs during the previous 3 years: 31 patients (41.3% of the CIC group that underwent urinalysis) |

| Yıldız N., 2014 Turkey [14] | Cross-sectional observational study | SCI | IC group: 243 M: 178 (73.2%) F: 65 (26.8%) | Aseptic IC | N.A. | Prevalence of UTIs related to aseptic IC: 51 patients (21.9% of the observed aseptic IC users) |

| Yilmaz B., 2014 Turkey [3] | Retrospective observational study | Acute SCI: 88 patients Chronic SCI: 119 patients | CIC group: 207 | CIC | N.A. | UTIs prevalence: Symptomatic UTIs: 76/207 patients (36.7%) |

| Krassioukov A., 2015 Canada [39] | Cross-sectional observational study | SCI | TOT: 61 patients Mean Age (SD): 35 ± 7.7 M: 53 (87%) F: 8 (13%) | CIC | Mean number of ICs: 6 ± 2 times per day (ranging from 1 to 10 per day). Re-use (19 patients). Mean number of IC using: 34 ± 50 times | UTI frequency: Single use IC: 1 ± 1 UTI/year Re-use IC: 4 ± 3 UTI/year UTIs in developing countries: 3.5 ± 2.8/year UTIs in developed countries: 1.6 ± 2/year |

| Rabadi M.H., 2015 USA [30] | Retrospective observational study | SCI with NB | CIC group: 40 patients | CIC | N.A. | UTI prevalence: 14 (35.0%) |

| Mukai S., 2016 Japan [28] | Retrospective observational study | SCI | TOT: 259 patients Median age: 47 (range 12–90 years) M: 220 (84.9%) F: 39 (15.1%) | CIC | Median number of CIC per day: 7 (Range: 1–20) | UTI prevalence: 129 (49.8%) Febrile UTIs during follow-up period: 67 (25.8%) |

| Alavinia S.M., 2017 Canada [20] | Prospective observational study | Subacute SCI | CIC group 40 (72.70%) | Self CIC: 25 Assisted CIC: 15 | N.A. | UTI incidence in CIC: 26 (65.0%) |

| Stillman M.D., 2018 USA [13] | Secondary analysis of data from a prospective clinical trial | Traumatic SCI | IC group At baseline: 35 3 months: 31 6 months: 35 9 months: 38 12 months: 39 | IC | N.A. | UTI incidence rate: At baseline: IC: 13/35 (37%) 3 months: IC: 19/31 (61%) 6 months: IC: 16/35 (46%) 9 months: IC: 13/38 (34%) 12 months: IC: 12/39 (31%) |

| Crescenze I., 2019 USA [22] | Prospective cohort study | SCI | CIC: 753 Non-self: 82 (10.9%) M: 67.1% F: 32.9% Mean age 43.2 (18–86) | Self CIC:671 Assisted CIC: 82 (10.9%) | Mean duration of CIC 9.5 years (0–44) | PRUTI reported per year >4: 209 patients (27.8%) |

| McClurg D., 2019 UK [10] | Three-part mixed-method study: Prospective observational study, qualitative interviews, retrospective survey. | MS | TOT CIC: 56 Continuers group (at 1 year follow up): 43 patients M: 12 (28%) F: 31 (72%) Mean Age (SD): 49.9 (12.5) Discontinuers: 13 patients M: 2 (15%) F: 11 (85%) Mean Age (SD): 51.3 (10.1) | Self-CIC | N.A. | Prevalence At baseline: Discontinuers (n = 13) reported UTIs: 3 (23%) Continuers (n = 43) reported UTIs: 22 (51%) At 8 months: Discontinuers: No UTI: 6 (46%) Same number of UTIs: 0 (0%) Increased UTIs: 7 (54%) Decreased UTIs: 0 (0%) Continuers: No UTIs: 6 (46%) Same number of UTIs: 11 (26%) Increased UTIs: 7 (54%) Decreased UTIs reported: 3 (7%) |

| Huang X. 2019 China [33] | Randomized clinical trial | SCI with NB | TOT: 80 patients M: 49 F: 31 Quality Control Circle group: 40 patients M: 25 F: 15 Mean Age (SD): 56.7 ± 4.3 years CG: 40 patients M: 24 F: 16 Mean (SD): 57.3 ± 4.8 Age years | Self-CIC | N.A. | UTI incidence Quality Control Circle Group: 4 patients (10%) Control Group: 13 patients (32.5%) |

| Roth J.D. 2019 USA [21] | Retrospective survey | SCI | CIC group: 753 Mean age (SD): 43.7 (13.1) years M: 504 (66.9%) | CIC | Mean number of daily catheterizations: 5.94 (SD 1.81). | PRUTI during the previous year: 0: 172 (22.8%) 1–3: 372 (49.4%) 4–6: 117 (15.5%) 6: 92 (12.2%) Adjusted odds of increased UTI frequency 3.42 (2.25–5.18) for CIC (reference spontaneous voiding) |

| Anderson C.E., 2019 Switzerland [23] | Prospective cohort study | SCI | IC group: 73 (19.8%) | Assisted-IC: 41 patients (11.1%) Self-IC: 32 patients (8.7%) | N.A. | UTI prevalence 28 days after admission Assisted IC Patients with 1 UTI: 12/41 patients (29.3%) Patients with ≥2 UTIs: 13/41 (31.7%) Self-IC Patients with 1 UTI: 8/32 (25.0%) Patients with ≥2 UTIs: 6/32 (18.8%) UTIs IR and IRR (reference Spontaneous Voiding): IC-assisted: Crude IR per 100 person-days (95% CI): 0.68 (0.52–0.90) Unadjusted IRR (95% CI): 6.16 (3.04–12.50) Adjusted IRR (95% CI): 6.05 (2.63–13.94) IC-self: Crude IR per 100 person-days (95% CI): 0.53 (0.39–0.71) Unadjusted IRR (95% CI): 4.50 (2.25–9.01) Adjusted IRR (95% CI): 5.16 (2.31–11.52) |

| Hennessey D., 2019 Australia [24] | Prospective observational study | SCI | ISC group: 45 | ISC | N.A. | UTIs/1000 days: 6.84 |

| Farrelly E., 2020 Sweden [26] | Prospective cohort study | Post-traumatic SCI | CIC group: 157 (38%) | CIC | N.A. | Mean number of UTIs during the previous year: 2.5 UTIs/year: 0: 58 (36.9%) 1–3: 57 (36.3%) 4–6: 26 (16.5%) >6: 16 (10.2%) |

| Nade E.S. 2020 Tanzania [16] | Cross-sectional pilot study | SCI | CIC patients: 23 | Self -IC: 8 (16%). Family member assisted IC: 15 (31.3%) | N.A. | Incidence of Febrile UTIs: 9 (39.2% of all patients performing CIC) Inpatients: 4 (25%) Outpatients: 5 (71%). |

| Patel D.P., 2020 USA [11] | Cross-sectional observational study nested within a registry-based observational study | SCI | TOT: 176 patients M: 110 (63%) F: 66 (37%) Mean age (SD): 45.3 (12.8) years | CIC | N.A. | PRUTI frequency during previous year (in 176 patients that discontinued CIC): 0: 17 (26%) 1–3: 79 patients (45%) ≥4: 60 patients (34%) Hospitalization for UTI during the previous year: 29 (16%) |

| Neyaz O., 2020 India [25] | Prospective observational study | SCI | TOT: 31 patients M: 29 (93%) F: 2 (7%) Mean Age (SD): 28.6 ± 9.2 years | Self-CIC | N.A. | Incidence of Symptomatic UTIs: 2.29 episodes per patient per year |

| Theisen K.M., 2020 USA [27] | Prospective observational study | SCI | CIC group: 780 | CIC | N.A. | PRUTI frequency during previous year: 0: 178 (46%) 1–3: 381 (49%) 4–6: 127 (16.7%) 6: 94 (12.4%) |

| Kim Y., 2021 South Korea [32] | Retrospective descriptive study | SCI | TOT: 964 M: 742 (77.0%) F: 222 (23.0%) Mean Age 46.1 (15.6) | Self CIC: 54 (5.6%) Caregiver assisted CIC: 64 (6.6%) | N.A. | UTI prevalence in Self CIC group: 12 (22.2%) UTI prevalence Caregiver assisted CIC: 13 (20.3%) |

| Walter M., 2021 Canada [17] | Cross sectional survey | SCI | IC group: 109 (84%) | IC | Median duration of IC: 10 years (IQR 6–15, range 1–28). Median frequency of catheterizations per day: 5 (IQR 4.5–6, range 1–10). | PRUTI incidence during previous year: 69 (63% of IC patients) Median number of PRUTIs per year: 1 (IQR 0–2, range 0–12). |

| Berger A., 2022 Multicentric (Germany, Netherlands) [31] | Retrospective Chart Review | SCI | IC patients 23 (31.5%) | Caregiver assisted IC | N.A. | UTI incidence at 3 months follow-up: 42 patients (57.5%) UTI incidence per 100 person-month: 31.46 |

| Chen S.F., 2022 Taiwan [38] | Retrospective observational study | SCI | CIC group: 81 patients | CIC/Self-CIC | N.A. | Recurrent UTI incidence: 57 (70.4%) |

| Xing H., 2023 China [29] | Retrospective Chart review | SCI | TOT 183 patients M: 123 (67.2%) F: 60 (32.8%) Median Age: 49.0 Years (37–59 range) | CIC: 56 (30.6%) Self-CIC: 27 (69.4%) | IC performed 4–6 times/day with disposable catheters | UTI incidence: 44 (24.0%) Occurrence rate of UTI: 1.31 (95% Cis, 0.96–1.77) events per 100 person-days |

| Liu J., 2023 China [18] | Cross-sectional observational study | SCI | CIC group: 623 | CIC | Frequency of CIC use (times per day): <1: 116 (18.6%) 1–6: 478 (76.7%) >6: 29 (4.7%) | Incidence UTIs: 525 (84.3%) Recurrent UTIs: 333 (53.5%) Number of outpatient visits for UTIs:3 (0.4% of total CIC users) Number of hospitalizations for UTIs:12 (1.9%) CIC use < 1/day (N = 116): UTIs: 107 (20.4%) OR (reference 1–6): 1.333 (95% CI: 0.595–2.988, p = 0.485) CIC use 1–6/day (N = 478): UTIs: 391 (74.5%) OR: 1 (Reference) CIC use > 6/day (N = 29): UTIs: 27 (93.1%) OR (reference 1–6): 2.378 (95% CI: 0.532–10.626, p = 0.257) |

| Sekido N. 2023 Japan [19] | Cross Sectional Internet Survey | SCI | ISC group: 247 M: 185 (74.9%) F: 62 (25.1%) Mean Age (SD): 47.8 ± 14.9 years | Reusable silicone catheter: 136 (55.1) Single-use catheter: 111 (44.9) | N.A. | UTI incidence ISC (247) Symptomatic UTI 129 (52.2%) Febrile UTI 82 (33.2%) Hcp-sUTI 96 (38.9%) Re-usable (136) Symptomatic UTI 75 (55.1%) Febrile UTI 46 (33.8%) Hcp-sUTI 58 (42.6%) Single Use (111) Symptomatic UTI 54 (48.6%) Febrile UTI 36 (32.4%) Hcp-sUTI 18 (34.2%) UTI episodes ISC (SD) Symptomatic UTI 2.8 (4.95) Febrile UTI 0.9 (2.14) Hcp-sUTI 1.5 (2.83) Re-usable (SD) Symptomatic UTI 2.8 (4.18) Febrile UTI 0.8 (1.43) Hcp-sUTI 1.5 (2.45) Single use (SD) Symptomatic UTI 2.8 (5.77) Febrile UTI 1.0 (2.77) Hcp-sUTI 1.4 (3.26) |

| Milicevic s., 2024; Serbia [34] | Retrospective study | SCI | TOT: 369 | Self IC: 287 Assisted IC: 72 | N.A. | UTI incidence: 252 (62.7%) Self IC 69 (17.2%) Assisted IC |

| Ali S., 2024; Saudi Arabia [35] | Retrospective cohort study | SCI | TOT: 1000 Gender: M: 87.2% F:12.8% F Mean age: 34.07y (13.19) | 524 (52.4%) hydrophilic coated catheters (HCC), 476 (47.6%) PVC uncoated catheters (PUC) | N.A. | Symptomatic UTI incidence HCC 46.60% PUC 79.40% |

| Luo J., 2024; China [36] | Retrospective Case Control study | SCI | TOT: 84 Control group 40 Observation group 44 | Self-CIC | N.A. | UTI prevalence: Control Group: 20 (50%) Observation Group: 11 (25%) |

| Cheng T.C., 2024; Taiwan [37] | Retrospective cohort study | SCI | TOT: 47 M 38 (80.9%) F 9 (19.1%) Mean age: 47y | CIC | N.A. | UTI incidence per month: 0.03 UTIs/month |

| Study | General Conditions | Intermittent Catheterization | User Compliance/Adherence | Local Urinary Tract Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Krassioukov A., 2015 [39] | - | - | Procedure-related (catheter reuse) | - |

| Mukai S., 2016 [28] | Gender (male); neurological status (ASIA scale C or worse) | - | - | - |

| McClurg D., 2019 [10] | - | - | CIC Compliance (continuation use, discontinuation use) | - |

| Anderson C.E., 2019 [23] | - | - | Hygienic Procedure (intermittent self catheterization, assisted catheterization) | - |

| Kim Y., 2021 [32] | - | Catheter type (indwelling, suprapubic catheters) | - | - |

| Liu J., 2023 [18] | Gender (male); disease duration; urinary incontinence | Change in catheterization method | Difficulty with insertion; infrequent CIC; catheter reuse (borderline) | - |

| Sekido N., 2023 [19] | Catheter type (indwelling catheters) | Procedure-related (catheter reuse) | - | |

| Milicevic S., 2024 [30] | Impaired Bladder Compliance (reflex voiding, and spontaneous voiding) | Catheter type (indwelling catheters) | Hygienic Procedure (intermittent self catheterization, assisted catheterization) | - |

| Ali S., 2024 [35] | - | Catheter type (hydrophilic-coated catheters, PVC catheters) | - | - |

| Luo J., 2024 [36] | - | - | Lack of caregiver education and support | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

D’Ambrosio, F.; Pappalardo, C.; Scardigno, A.; Medico, M.D.; Risuleo, P.E.; Orsini, F.; Ricciardi, R.; De Vito, E.; Ricciardi, W.; Calabrò, G.E. Silent Burden of Urinary Tract Infections in Intermittent Catheter Users with Neurological Disorders: A Scoping Review. Diseases 2026, 14, 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases14020058

D’Ambrosio F, Pappalardo C, Scardigno A, Medico MD, Risuleo PE, Orsini F, Ricciardi R, De Vito E, Ricciardi W, Calabrò GE. Silent Burden of Urinary Tract Infections in Intermittent Catheter Users with Neurological Disorders: A Scoping Review. Diseases. 2026; 14(2):58. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases14020058

Chicago/Turabian StyleD’Ambrosio, Floriana, Ciro Pappalardo, Anna Scardigno, Manuel Del Medico, Pietro Eric Risuleo, Francesca Orsini, Roberto Ricciardi, Elisabetta De Vito, Walter Ricciardi, and Giovanna Elisa Calabrò. 2026. "Silent Burden of Urinary Tract Infections in Intermittent Catheter Users with Neurological Disorders: A Scoping Review" Diseases 14, no. 2: 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases14020058

APA StyleD’Ambrosio, F., Pappalardo, C., Scardigno, A., Medico, M. D., Risuleo, P. E., Orsini, F., Ricciardi, R., De Vito, E., Ricciardi, W., & Calabrò, G. E. (2026). Silent Burden of Urinary Tract Infections in Intermittent Catheter Users with Neurological Disorders: A Scoping Review. Diseases, 14(2), 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases14020058