Real-World Evidence Evaluation of Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) Vaccines: Deep Dive into Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Data Source

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Review of Reports

2.4. Ad Hoc Analyses and Review

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

Pregnancy

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anastassopoulou, C.; Medić, S.; Ferous, S.; Boufidou, F.; Tsakris, A. Development, Current Status, and Remaining Challenges for Respiratory Syncytial Virus Vaccines. Vaccines 2025, 13, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, J.M.; Khan, F.; Begier, E.; Swerdlow, D.L.; Jodar, L.; Falsey, A.R. Rates of Medically Attended RSV Among US Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2022, 9, ofac300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfano, F.; Bigoni, T.; Caggiano, F.P.; Papi, A. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in older adults: An update. Drugs Aging 2024, 41, 487–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, H.; Schweitzer, J.W.; Justice, N.A. Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection in Children; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459215/ (accessed on 31 May 2025).

- Kaler, J.; Hussain, A.; Patel, K.; Hernandez, T.; Ray, S. Respiratory syncytial virus: A comprehensive review of transmission, pathophysiology, and manifestation. Cureus 2023, 15, 331–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matias, G.; Taylor, R.; Haguinet, F.; Schuck-Paim, C.; Lustig, R.; Shinde, V. Estimates of hospitalization attributable to influenza and RSV in the US during 1997–2009, by age and risk status. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Blau, D.M.; Caballero, M.T.; Feikin, D.R.; Gill, C.J.; Madhi, S.A.; Omer, S.B.; Simões, E.A.; Campbell, H.; et al. Global, regional, and national disease burden estimates of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in children younger than 5 years in 2019: A systematic analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 2047–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzari, C.; Baraldi, E.; Bonanni, P.; Bozzola, E.; Coscia, A.; Lanari, M.; Manzoni, P.; Mazzone, T.; Sandri, F.; Checcucci Lisi, G.; et al. Epidemiology and prevention of respiratory syncytial virus infections in children in Italy. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2021, 47, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, W.W.; Shay, D.K.; Weintraub, E.; Brammer, L.; Cox, N.; Anderson, L.J.; Fukuda, K. Mortality associated with influenza and respiratory syncytial virus in the United States. JAMA 2003, 289, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lively, J.Y.; Curns, A.T.; Weinberg, G.A.; Edwards, K.M.; Staat, M.A.; Prill, M.M.; Gerber, S.I.; Langley, G.E. Respiratory syncytial virus–associated outpatient visits among children younger than 24 months. J. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. Soc. 2019, 8, 284–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heppe Montero, M.; Gil-Prieto, R.; Walter, S.; Aleixandre Blanquer, F.; Gil De Miguel, A. Burden of severe bronchiolitis in children up to 2 years of age in Spain from 2012 to 2017. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 18, 1883379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairbank, R. RSV wave hammers hospitals—But vaccines and treatments are coming. Nature 2022. epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Drug Administration. AREXVY. 2023. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/arexvy (accessed on 31 May 2025).

- Food and Drug Administration. ABRYSVO. 2023. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/abrysvo (accessed on 31 May 2025).

- Britton, A.; Kotton, C.N.; Hutton, D.W.; Fleming-Dutra, K.E.; Godfrey, M.; Ortega-Sanchez, I.R.; Broder, K.R.; Talbot, H.K.; Long, S.S.; Havers, F.P.; et al. Use of respiratory syncytial virus vaccines in adults aged ≥ 60 years: Updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2024. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2024, 73, 696–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleming-Dutra, K.E. Use of the Pfizer respiratory syncytial virus vaccine during pregnancy for the prevention of respiratory syncytial virus–associated lower respiratory tract disease in infants: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2023. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2023, 72, 1115–1122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Simões, E.A.; Center, K.J.; Tita, A.T.; Swanson, K.A.; Radley, D.; Houghton, J.; McGrory, S.B.; Gomme, E.; Anderson, M.; Roberts, J.P.; et al. Prefusion F protein–based respiratory syncytial virus immunization in pregnancy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 1615–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebia, Z.; Reyes, O.; Jeanfreau, R.; Kantele, A.; De Leon, R.G.; Sánchez, M.G.; Banooni, P.; Gardener, G.J.; Rasero, J.L.B.; Pardilla, M.B.E.; et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an investigational respiratory syncytial virus vaccine (RSVPreF3) in mothers and their infants: A phase 2 randomized trial. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 228, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, D.; Chawla, J.; Blavo, C. Use of the Abrysvo Vaccine in Pregnancy to Prevent Respiratory Syncytial Virus in Infants: A Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e68349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Kong, L.; Liu, X.; Wu, P.; Zhang, L.; Ding, F. Effectiveness of nirsevimab immunization against RSV infection in preterm infants: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1581970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, S.T.; Tuckerman, J.; Barr, I.G.; Crawford, N.W.; Wurzel, D.F. Respiratory syncytial virus preventives for children in Australia: Current landscape and future directions. Med. J. Aust. 2025, 222, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zar, H.J.; Cacho, F.; Kootbodien, T.; Mejias, A.; Ortiz, J.R.; Stein, R.T.; Hartert, T.V. Early-life respiratory syncytial virus disease and long-term respiratory health. Lancet Respir. Med. 2024, 12, 810–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verwey, C.; Ramocha, L.; Laubscher, M.; Baillie, V.; Nunes, M.; Gray, D.; Hantos, Z.; Dangor, Z.; Madhi, S. Pulmonary sequelae in 2-year-old children after hospitalisation for respiratory syncytial virus lower respiratory tract infection during infancy: An observational study. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2023, 10, e001618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, S.A.; Jamieson, D.J. Maternal RSV vaccine—Weighing benefits and risks. Obstet. Anesth. Dig. 2024, 44, 138–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boytchev, H. Maternal RSV vaccine: Further analysis is urged on preterm births. BMJ 2023, 381, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.; Dawes, L.; Huang, Y.A.; Tay, E.; Dymock, M.; O’Moore, M.; King, C.; Macartney, K.; Wood, N.; Deng, L. Short term safety profile of respiratory syncytial virus vaccine in adults aged ≥ 60 years in Australia. Lancet Reg. Health–West. Pac. 2025, 56, 101506. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Branche, A.R. Real-world effectiveness studies of the benefit of RSV vaccines. Lancet 2024, 404, 1498–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alami, A.; Pérez-Lloret, S.; Mattison, D.R. Safety surveillance of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccine among pregnant individuals: A real-world pharmacovigilance study using the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System. BMJ Open 2025, 15, e087850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regan, A.K. Perinatal Outcomes after RSV Vaccination during Pregnancy—Addressing Emerging Concerns. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2419229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hause, A.M. Early safety findings among persons aged ≥ 60 years who received a respiratory syncytial virus vaccine—United States, May 3, 2023–April 14, 2024. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2024, 73, 489–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melgar, M.; Britton, A.; Roper, L.E.; Talbot, H.K.; Long, S.S.; Kotton, C.N.; Havers, F.P. Use of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Vaccines in Older Adults: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2023. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2023, 72, 793–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, P.L. Maternal RSV vaccine safety surveillance. In Proceedings of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices Meeting, Atlanta, GA, USA, 28 June 2024; pp. 26–28. [Google Scholar]

- Shimabukuro, T.T.; Nguyen, M.; Martin, D.; DeStefano, F. Safety monitoring in the vaccine adverse event reporting system (VAERS). Vaccine 2015, 33, 4398–4405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System. VAERS Data Sets. Available online: https://vaers.hhs.gov/data/datasets.html (accessed on 31 May 2025).

- Chen, R.T.; Rastogi, S.C.; Mullen, J.R.; Hayes, S.W.; Cochi, S.L.; Donlon, J.A.; Wassilak, S.G. The vaccine adverse event reporting system (VAERS). Vaccine 1994, 12, 542–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albalawi, O.M.; Alomran, M.I.; Alsagri, G.M.; Althunian, T.A.; Alshammari, T.M. Analyzing the US Post-marketing safety surveillance of COVID-19 vaccines. Saudi Pharm. J. 2022, 30, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System. VAERS DATA USE GUIDE. Available online: https://vaers.hhs.gov/docs/VAERSDataUseGuide_en_September2021.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2025).

- Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities. Available online: https://www.meddra.org/ (accessed on 31 May 2025).

- Fusaroli, M.; Salvo, F.; Begaud, B.; AlShammari, T.M.; Bate, A.; Battini, V.; Brueckner, A.; Candore, G.; Carnovale, C.; Crisafulli, S.; et al. The REporting of A disproportionality analysis for DrUg safety signal detection using individual case safety reports in PharmacoVigilance (READUS-PV): Explanation and elaboration. Drug Saf. 2024, 47, 585–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moro, P.L.; Museru, O.I.; Niu, M.; Lewis, P.; Broder, K. Reports to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System after hepatitis A and hepatitis AB vaccines in pregnant women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 210, 561.e1–561.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alenzi, K.A.; Alsuhaibani, D.; Batarfi, B.; Alshammari, T.M. Pancreatitis with use of new diabetic medications: A real-world data study using the post-marketing FDA adverse event reporting system (FAERS) database. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1364110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thaibah, H.A.; Banji, O.J.; Banji, D.; Alshammari, T.M. Diabetic ketoacidosis and the use of new hypoglycemic groups: Real-world evidence utilizing the food and drug administration adverse event reporting system. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaibah, H.A.; Banji, O.J.; Banji, D.; Almansour, H.A.; Alshammari, T.M. Suicidality Risks Associated with Finasteride, a 5-Alpha Reductase Inhibitor: An Evaluation of Real-World Data from the FDA Adverse Event Reports. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Puijenbroek, E.P.; Bate, A.; Leufkens, H.G.; Lindquist, M.; Orre, R.; Egberts, A.C. A comparison of measures of disproportionality for signal detection in spontaneous reporting systems for adverse drug reactions. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2002, 11, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poluzzi, E.; Raschi, E.; Piccinni, C.; De Ponti, F. Data mining techniques in pharmacovigilance: Analysis of the publicly accessible FDA adverse event reporting system (AERS). In Data Mining Applications in Engineering and Medicine; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Norén, G.N.; Hopstadius, J.; Bate, A. Shrinkage observed-to-expected ratios for robust and transparent large-scale pattern discovery. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2013, 22, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Ye, X.; Guo, X.; Liu, D.; Xu, J.; Hu, F.; Zhai, Y.; Gao, Y.; Xu, X.; Dong, Z.; et al. Safety of SGLT2 inhibitors: A pharmacovigilance study from 2013 to 2021 based on FAERS. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 766125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awosika, A.O.; Patel, P. Respiratory Syncytial Virus Prefusion F (RSVPreF3) Vaccine. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kampmann, B.; Madhi, S.A.; Munjal, I.; Simões, E.A.F.; Pahud, B.A.; Llapur, C.; Baker, J.; Pérez Marc, G.; Radley, D.; Shittu, E.; et al. Bivalent Prefusion F Vaccine in Pregnancy to Prevent RSV Illness in Infants. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 1451–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.; Goswami, J.; Baqui, A.H.; Doreski, P.A.; Perez-Marc, G.; Zaman, K.; Monroy, J.; Duncan, C.J.; Ujiie, M.; Rämet, M.; et al. Efficacy and safety of an mRNA-based RSV PreF vaccine in older adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 2233–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consumer Affairs. Population over 65 by State, U.S. Census Bureau. 2025. Available online: https://www.consumeraffairs.com/homeowners/elderly-population-by-state.html (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- FDA Approves First Vaccine for Pregnant Individuals to Prevent RSV in Infants Food and Drug Administration. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-vaccine-pregnant-individuals-prevent-rsv-infants?ftag=MSF0951a18 (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Dieussaert, I.; Hyung Kim, J.; Luik, S.; Seidl, C.; Pu, W.; Stegmann, J.-U.; Swamy, G.K.; Webster, P.; Dormitzer, P.R. RSV prefusion F protein–based maternal vaccine—Preterm birth and other outcomes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 1009–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Preterm Birth. WHO Fact Sheet. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/preterm-birth (accessed on 31 May 2025).

- Moro, P.L.; Aynalem, G.; Romanson, B.; Marquez, P.L.; Tepper, N.K.; Olson, C.K.; Jones, J.; Nair, N.; Broder, K.R. Safety Monitoring of Pfizer’s Respiratory Syncytial Virus Vaccine in Pregnant Women in the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, 2023-2024, United States. Vaccine 2025, 62, 127497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, J. First RSV vaccine for older adults is approved in Europe. BMJ 2023, 381, 978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falsey, A.R.; Williams, K.; Gymnopoulou, E.; Bart, S.; Ervin, J.; Bastian, A.R.; Menten, J.; De Paepe, E.; Vandenberghe, S.; Chan, E.K.; et al. Efficacy and safety of an Ad26. RSV. preF–RSV preF protein vaccine in older adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 609–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, Y.Y. Respiratory syncytial virus prefusion F subunit vaccine: First approval of a maternal vaccine to protect infants. Pediatr. Drugs 2023, 25, 729–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AusVaxSafety. AusVaxSafety Publishes Australian-First Safety Data for Arexvy RSV Vaccine. 2025. Available online: https://ausvaxsafety.org.au/ausvaxsafety-publishes-australian-first-safety-data-arexvy-rsv-vaccine (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Bach, A.T.; Goad, J.A. The role of community pharmacy-based vaccination in the USA: Current practice and future directions. Integr. Pharm. Res. Pract. 2015, 4, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Event of Interest | Other Events | |

|---|---|---|

| Exposure of interest | a | b |

| Non-exposure | c | d |

| Measures | Formula | Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| ROR | 95%CI/ > 1, N ≥ 2 | |

| PRR | PRR ≥ 2, χ2 ≥ 4, N ≥ 3 | |

| EBGM | EBGM ≥ 2 | |

| IC IC025 IC975 | Log2 IC − 3.3 × (O + 0.5) − 1/2 − 2 × (O + 0.5) − 3/2 IC + 2.4 × (O + 0.5) − 1/2 − 0.5 × (O + 0.5) − 3/2 | Lower limit of 95% CI |

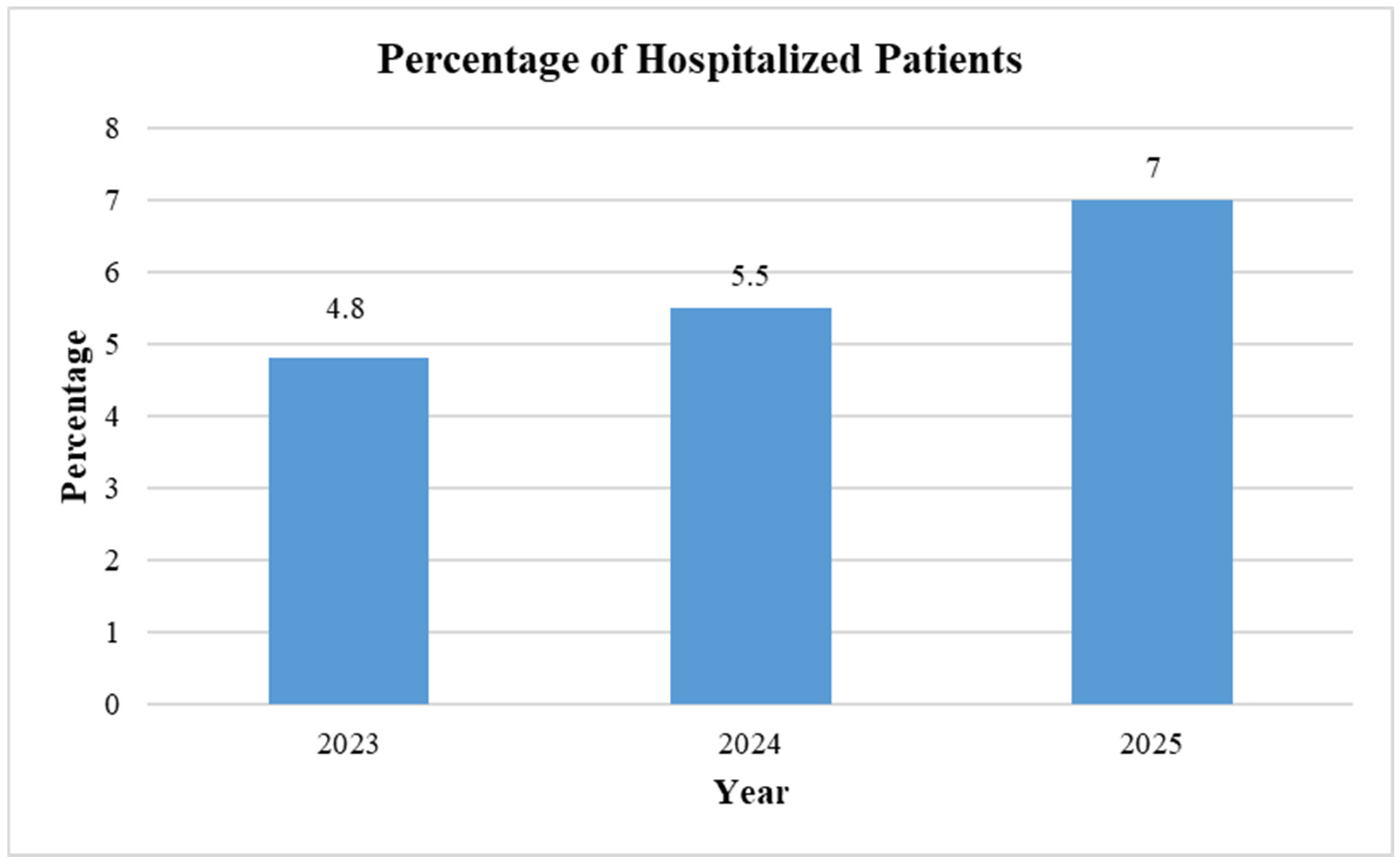

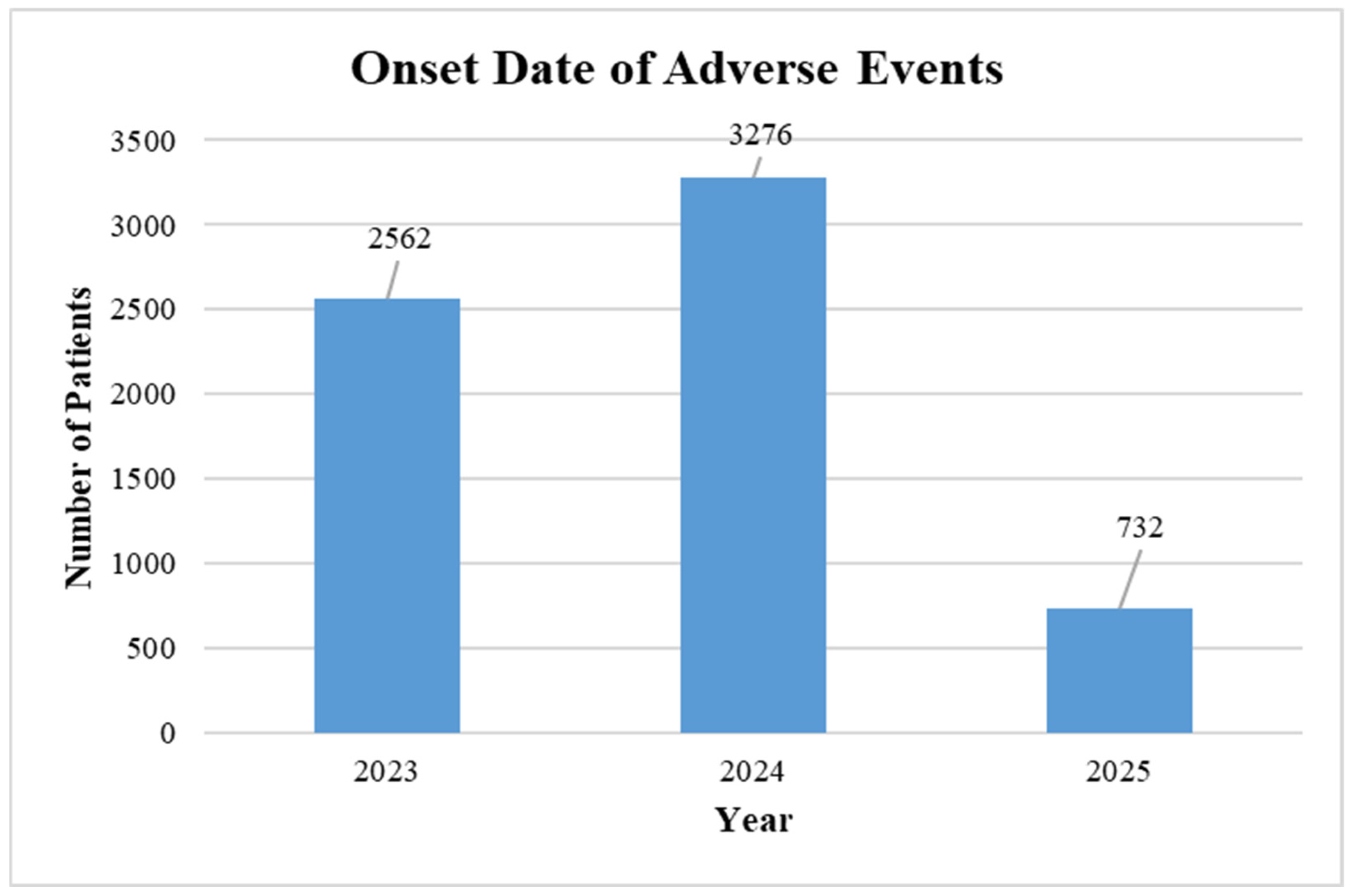

| Variables | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 1715 | 67.0 | 2086 | 63.7 | 459 | 62.7 |

| Male | 647 | 25.3 | 784 | 23.9 | 218 | 29.8 |

| Unknown * | 199 | 7.8 | 406 | 12.4 | 55 | 7.5 |

| Age in Years | ||||||

| <18 | 26 | 1.0 | 56 | 1.7 | 15 | 2.0 |

| ≥18–59 | 185 | 7.2 | 279 | 8.5 | 50 | 6.8 |

| ≥60–75 | 1194 | 46.6 | 1240 | 37.9 | 299 | 40.8 |

| ≥76 | 604 | 23.6 | 759 | 23.2 | 223 | 30.5 |

| NA | 552 | 21.6 | 942 | 28.8 | 145 | 19.8 |

| Total | 2561 | 3276 | 732 | |||

| Injection Site Pain (by Sex) | ||||||

| Gender | 61 | 94 | 18 | |||

| Female | 37 | 60.7 | 63 | 67.0 | 15 | 83.3 |

| Male | 20 | 32.8 | 25 | 26.6 | 3 | 16.7 |

| Unknown | 4 | 6.6 | 6 | 6.4 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Age in Years | ||||||

| 18–59 years | 3 | 5.8 | – | – | – | – |

| 60–75 years | 25 | 48.1 | 55 | 67.9 | 13 | 86.7 |

| >75 years | 24 | 46.2 | 26 | 32.1 | 2 | 13.3 |

| Total Injection Site Pain Reports | 52 | 81 | 15 | |||

| State | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| California | 196 | 7.7 | 246 | 7.5 | 15 | 5.2 |

| Florida | 183 | 7.1 | 262 | 8 | 74 | 25.5 |

| Georgia | – | – | – | – | 31 | 10.7 |

| New York | 143 | 5.6 | 117 | 3.6 | – | – |

| Pennsylvania | 94 | 3.7 | 126 | 3.8 | 11 | 3.8 |

| Tennessee | – | – | – | – | 18 | 6.2 |

| Texas | 115 | 4.5 | 155 | 4.7 | – | – |

| Number of Days | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| 0 | 1208 | 47.2 | 1495 | 45.6 | 400 | 54.6 |

| 1–3 | 1078 | 42.1 | 934 | 28.5 | 160 | 21.9 |

| 4–7 | 203 | 7.9 | 201 | 6.14 | 30 | 4.1 |

| 8–14 | 117 | 4.6 | 117 | 3.57 | 38 | 5.2 |

| 15–30 | 80 | 3.1 | 77 | 2.35 | 25 | 3.4 |

| 31–60 | 20 | 0.8 | 32 | 0.98 | 11 | 1.5 |

| 61–100 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 0.18 | 2 | 0.3 |

| 101–300 | 0 | 0.0 | 10 | 0.31 | 5 | 0.7 |

| >300 | 6 | 0.2 | 5 | 0.15 | 9 | 1.2 |

| NA | 556 | 21.7 | 926 | 28.3 | 175 | 23.9 |

| RSV Vaccine | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Abrysvo | 780 | 30.5 | 927 | 28.3 | 209 | 28.6 |

| Arexvy | 1759 | 68.7 | 2300 | 70.2 | 504 | 68.9 |

| MRESVIA | 0 | 0 | 21 | 0.6 | 12 | 1.6 |

| No Brand Name | 22 | 0.9 | 28 | 0.9 | 7 | 1.0 |

| Total | 2561 | 100 | 3276 | 100 | 732 | 100 |

| Vaccination Center/Facility | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Military | 10 | 0.4 | 11 | 0.3 | 3 | 0.4 |

| Pharmacy | 1619 | 63.2 | 1747 | 53.3 | 442 | 60.4 |

| Public | 19 | 0.7 | 34 | 1.0 | 7 | 1.0 |

| Private | 192 | 7.5 | 306 | 9.3 | 83 | 11.3 |

| School or Student Health Clinic | 1 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Nursing Home or Senior Living Facility | 10 | 0.4 | 41 | 1.3 | 4 | 0.5 |

| Unknown | 665 | 26.0 | 1060 | 32.4 | 174 | 23.8 |

| Workplace Clinic | 6 | 0.2 | 9 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Other * | 39 | 1.5 | 67 | 2.0 | 19 | 2.6 |

| Symptom | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Injection site pain | 735 | 11.2 |

| Pain | 534 | 8.1 |

| Injection site erythema | 381 | 5.8 |

| Fatigue | 316 | 4.8 |

| Pain in extremity | 316 | 4.8 |

| Headache | 285 | 4.3 |

| Injection site swelling | 268 | 4.1 |

| No adverse event | 534 | 8.1 |

| Symptom | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Fatigue | 296 | 11.6 | – | – | 20 | 2.7 |

| Headache | 285 | 11.1 | – | – | – | – |

| Injection site pain | 284 | 11.1 | 408 | 12.5 | 43 | 5.9 |

| Pain in extremity | 283 | 11.1 | – | – | 33 | 4.5 |

| Pain | 269 | 10.5 | 265 | 8.1 | – | – |

| No adverse event | 110 | 4.3 | 280 | 8.5 | 144 | 19.7 |

| Exposure during pregnancy | – | – | 356 | 10.9 | – | – |

| Injection site erythema | – | – | 342 | 10.4 | 39 | 5.3 |

| Injection site swelling | – | – | 268 | 8.2 | – | – |

| Arthralgia | – | – | – | – | 20 | 2.7 |

| Vaccination Error | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Wrong product administered | 68 | 2.7 | 201 | 6.1 | 11 | 1.5 |

| Product administered to patients of inappropriate age | 131 | 5.1 | 182 | 5.6 | 16 | 2.2 |

| Incorrect dose administered | 37 | 1.4 | 22 | 0.7 | 4 | 0.5 |

| Syringe issue | 20 | 0.8 | 61 | 1.9 | 3 | 0.4 |

| Extra dose administered | 61 | 2.4 | 490 | 15 | 265 | 36.2 |

| Product use issue | 81 | 3.2 | 204 | 6.2 | 16 | 2.2 |

| Wrong technique in product usage process | 11 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Incorrect route of product administration | 22 | 0.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Underdose | 33 | 1.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Product preparation issue | 48 | 1.9 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0.5 |

| Exposure during pregnancy | 129 | 5 | 356 | 10.9 | 53 | 7.2 |

| Symptom | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Cesarean section | 7 | 5.4 | 7 | 2.0 | 0 | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 0 | 0 | 5 | 1.4 | 2 | 4 |

| Headache | 0 | 0 | 10 | 2.8 | 1 | 4 |

| Injection site erythema | 7 | 7 | 12 | 3.4 | 2 | 4 |

| Premature delivery/labor | 24 | 18.6 | 26 | 7.3 | 7 | 13 |

| Premature labor | – | – | – | – | 0 | – |

| Premature rupture of membranes | 6 | 4.7 | 5 | 1.4 | 0 | 0 |

| Stillbirth | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.3 | 4 | 7 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 |

| Year | Number of Injection Site Pains AEFIs * | Reported ADEs with the RSV Vaccines | ROR (95% CI) | PRR (95% CI) | EBGM (95% CI) | IC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | 61 | 2934 | 3.80 (2.90–4.85) | 3.74 (2.86–4.88) | 3.40 (2.60–4.44) | 1.77 (1.74–1.79) |

| 2024 | 94 | 3615 | 1.74 (1.40–2.17) | 1.73 (1.40–2.14) | 1.64 (1.32–2.03) | 0.71 (0.69–0.72) |

| 2025 ** | 18 | 806 | 1.69 (1.04–2.77) | 1.67 (1.03–2.74) | 1.59 (1.00–2.60) | 0.67 (0.56–0.73) |

| Year | Number of Pains AEFIs * | Reported ADEs with the RSV Vaccines | ROR | PRR | EBGM | IC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (95% CI) | (95% CI) | |||||

| 2023 | 232 | 2934 | 1.81 (1.58–2.07) | 1.74 (1.52–2.00) | 1.71 (1.49–1.96) | 0.77 (0.76–0.78) |

| 2024 | 177 | 3615 | 1.01 (0.86–1.18) | 1.01 (0.86–1.17) | 1.01 (0.86–1.16) | 0.007 (−0.002–0.014) |

| 2025 ** | 33 | 806 | 0.86 (0.63–1.23) | 0.86 (0.63–1.23) | 0.87 (0.61–1.25) | −0.19 (−0.24–(−0.16)) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Alshammari, T.M.; Alshammari, M.K.; Alosaimi, H.M. Real-World Evidence Evaluation of Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) Vaccines: Deep Dive into Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System. Diseases 2026, 14, 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases14010029

Alshammari TM, Alshammari MK, Alosaimi HM. Real-World Evidence Evaluation of Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) Vaccines: Deep Dive into Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System. Diseases. 2026; 14(1):29. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases14010029

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlshammari, Thamir M., Mohammed K. Alshammari, and Hind M. Alosaimi. 2026. "Real-World Evidence Evaluation of Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) Vaccines: Deep Dive into Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System" Diseases 14, no. 1: 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases14010029

APA StyleAlshammari, T. M., Alshammari, M. K., & Alosaimi, H. M. (2026). Real-World Evidence Evaluation of Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) Vaccines: Deep Dive into Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System. Diseases, 14(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases14010029