The Effectiveness of Patient Education Interventions to Oncological Entero-Urostomy Patients and Caregivers: A Small Sample Size Pilot Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Patient Education Intervention Methodology

2.3. Patient Recruitment

2.4. Data Collection and Assessment Tools

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Ethical Considerations

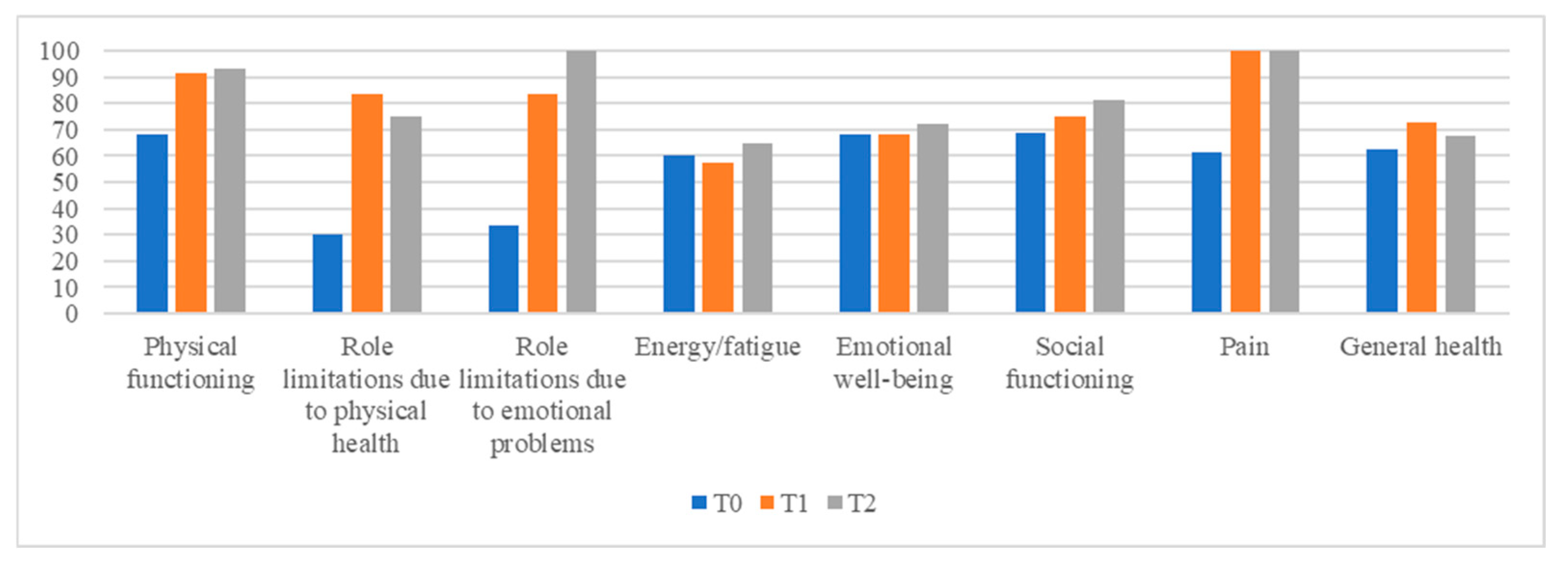

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Erwin-Toth, P. Ostomy pearls: A concise guide to stoma siting, pouching systems, patient education and more. Adv. Skin. Wound Care 2003, 16, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wulff-Burchfield, E.M.; Potts, M.; Glavin, K.; Mirza, M. A qualitative evaluation of a nurse-led pre-operative stoma education program for bladder cancer patients. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 5711–5719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsujinaka, S.; Tan, K.; Miyakura, Y.; Fukano, R.; Oshima, M.; Konishi, F.; Rikiyama, T. Current Management of Intestinal Stomas and Their Complications. J. Anus Rectum Colon. 2020, 4, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalilzadeh Ganjalikhani, M.; Tirgari, B.; Roudi Rashtabadi, O.; Shahesmaeili, A. Studying the effect of structured ostomy care training on quality of life and anxiety of patients with permanent ostomy. Int. Wound J. 2019, 16, 1383–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacorossi, L.; Petrone, F.; Gambalunga, F.; Bolgeo, T.; Lavalle, T.; Cacciato, D.; Canofari, E.; Ciacci, A.; De Leo, A.; Hossu, T.; et al. Patient education in oncology: Training project for nurses of the “Regina Elena” National Cancer Institute of Rome (Italy). Teach. Learn. Nurs. 2023, 18, e13–e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panattoni, N.; Mariani, R.; Spano, A.; De Leo, A.; Iacorossi, L.; Petrone, F.; Di Simone, E. Nurse specialist and ostomy patient: Competence and skills in the care pathway. A scoping review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2023, 32, 5959–5973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzer, B.; Matzel, K.; Schiedeck, T.; Christiansen, J.; Christensen, P.; Rius, J.; Richter, P.; Lehur, P.A.; Masin, A.; Kuzu, M.A.; et al. Do geographic and educational factors influence the quality of life in rectal cancer patients with a permanent colostomy? Dis. Colon. Rectum 2005, 48, 2209–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilden, V.P.; Tilden, S. Benner, P. (1984). From novice to expert, excellence and power in clinical nursing practice. Menlo Park, CA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, 307 pp. Res. Nurs. Health 1985, 9, 95–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redman, B.K. The Practice of Patient Education; Mosby Inc.: St. Louis, MI, USA, 1997; ISBN 978-0323012799. [Google Scholar]

- Clement, S.; Ibrahim, S.; Crichton, N.; Wolf, M.; Rowlands, G. Complex interventions to improve the health of people with limited literacy: A systematic review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2009, 75, 340–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, E.; Dieckmann, N.; Dixon, A.; Hibbard, J.H.; Mertz, C.K. Less is more in presenting quality information to consumers. Med. Care Res. Rev. 2007, 64, 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserman, M.A.; McGee, M.F. Preoperative Considerations for the Ostomate. Clin. Colon. Rectal Surg. 2017, 30, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretto, B. Educazione terapeutica del paziente tra competenze e contesti di cura: Riflessioni sul ruolo dell’educatore professionale. J. Health Care Educ. Pract. 2019, 1/2, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Thabane, L.; Ma, J.; Chu, R.; Cheng, J.; Ismaila, A.; Rios, L.P.; Robson, R.; Thabane, M.; Giangregorio, L.; Goldsmith, C.H. A tutorial on pilot studies: The what, why and how. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2010, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenbroucke, J.P.; von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Pocock, S.J.; Poole, C.; Schlesselman, J.J.; Egger, M. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): Explanation and elaboration. Int. J. Surg. 2014, 12, 1500–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidelines Workgroup Patient Education Practice Guidelines for Health Care Professionals. Available online: https://www.hcea-info.org/patient-education-practice-guidelines-for-health-care-professionals (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Ghafoor, E.; Riaz, M.; Eichorst, B.; Fawwad, A.; Basit, A. Evaluation of Diabetes Conversation Map™ Education Tools for Diabetes Self-Management Education. Diabetes Spectr. 2015, 28, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamburini, M.; Gangeri, L.; Brunelli, C.; Beltrami, E.; Boeri, P.; Borreani, C.; Fusco Karmann, C.; Greco, M.; Miccinesi, G.; Murru, L.; et al. Assessment of hospitalised cancer patients’ needs by the Needs Evaluation Questionnaire. Ann. Oncol. 2000, 11, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, J.E.; Sherbourne, C.D. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med. Care 1992, 30, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, G.; Vellone, E.; Sciara, S.; Stievano, A.; Proietti, M.G.; Manara, D.F.; Marzo, E.; Panataleo, G. Two new tools for self-care in ostomy patients and their informal caregivers: Psychosocial, clinical, and operative aspects. Int. J. Urol. Nur 2019, 13, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroni, L.; Sguazzin, C.; Filipponi, L.; Bruletti, G.; Callegari, S.; Galante, E.; Giorgi, I.; Majani, G.; Bertolotti, G. Caregiver Need Assessment: A questionnaire for caregiver demand. G. Ital. Med. Lav. Ergon. 2008, 30, 84. [Google Scholar]

- Chattat, R.; Cortesi, V.; Izzicupo, F.; Del Re, M.L.; Sgarbi, C.; Fabbo, A.; Bergonzini, E. The Italian version of the Zarit Burden interview: A validation study. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2011, 23, 797–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thariat, J.; Creisson, A.; Chamignon, B.; Dejode, M.; Gastineau, M.; Hébert, C.; Boissin, F.; Topfer, C.; Gilbert, E.; Grondin, B.; et al. Integrating patient education in your oncology practice. Bull. Cancer 2016, 103, 674–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, D.; Patel, S.; Yum, K.; Smith, C.B.; Tsao, C.; Kim, S. Impact of Pharmacist-Led Patient Education in an Ambulatory Cancer Center: A Pilot Quality Improvement Project. J. Pharm. Pract. 2022, 35, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaupp, K.; Scott, S.; Minard, L.V.; Lambourne, T. Optimizing patient education of oncology medications: A quantitative analysis of the patient perspective. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 2019, 25, 1445–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, S.; Shortell, S.M. Implementing accountable care organizations: Ten potential mistakes and how to learn from them. JAMA 2011, 306, 758–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, J.; Harrison, J.D.; Young, J.M.; Butow, P.N.; Solomon, M.J.; Masya, L. What are the current barriers to effective cancer care coordination? A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2010, 10, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundstrøm, L.H.; Johnsen, A.T.; Ross, L.; Petersen, M.A.; Groenvold, M. Cross-sectorial cooperation and supportive care in general practice: Cancer patients’ experiences. Fam. Pract. 2011, 28, 532–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahay, T.B.; Gray, R.E.; Fitch, M. A qualitative study of patient perspectives on colorectal cancer. Cancer Pract. 2000, 8, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, J.D. Building Concept Maps. Strategies and Methods for Using Them in Research; Erickson: Central Point, OR, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-99957-0-309-7. [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen, K.; Buswell, L.; Fadelu, T. A Systematic Review of Patient Education Strategies for Oncology Patients in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Oncologist 2023, 28, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, M.; Migneco, A.; Mansueto, P.; Tringali, G.; DI Lorenzo, G.; Rini, G.B. Therapeutic patient education in oncology: Pedagogical notions for women’s health and prevention. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2007, 16, 9–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

| Patients N (%) | Caregivers N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 5 (100%) | 5 (100%) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 3 (60%) | 2 (40%) |

| Female | 1 (20%) | 3 (60%) |

| Unknown | 1 (20%) | 0 |

| Education | ||

| Primary | 1 (20%) | 0 |

| Secondary | 1 (20%) | 3 (60%) |

| Higher | 2 (40%) | 2 (40%) |

| Degree | 1 (20%) | 0 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 5 (100%) | 5 (100%) |

| Unmarried | 0 | 0 |

| Job | ||

| Worker | 1 (20%) | 1 (20%) |

| Housewife | 1 (20%) | 2 (40%) |

| Retired | 2 (40%) | 2 (40%) |

| Undeclared | 1 (20%) | 0 |

| Living alone | ||

| Yes | 0 | 0 |

| No | 5 (100%) | 5 (100%) |

| Children | ||

| Yes | 4 (80%) | 5 (100%) |

| No | 1 (20%) | 0 |

| Surgery | ||

| Yes | 5 (100%) | / |

| No | 0 | / |

| Chemotherapy | ||

| Yes | 4 (80%) | / |

| No | 1 (20%) | / |

| Radiotherapy | ||

| Yes | 3 (60%) | / |

| No | 2 (40%) | / |

| T0 | T1 | T2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pz 1 | 134 | 135 | 147 |

| Pz 2 | 153 | 123 | 145 |

| Pz 3 | 143 | 136 | 152 |

| Pz 4 | 142 | 126 | 144 |

| Pz 5 | 151 | 128 | 148 |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Overall | 144.6 (±0.4) | 129.6(±0.1) | 147.7 (±0.1) |

| Question n° | T0 | T1 | T2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| 1 | 3.20 (±1.30) | 2.60 (±1.14) | 3.60 (±0.55) |

| 2 | 2.80 (±1.64) | 2.80 (±1.10) | 3.20 (±0.45) |

| 3 | 2.80 (±1.64) | 2.20 (±1.30) | 3.60 (±0.55) |

| 4 | 1.80 (±1.30) | 2.00 (±1.22) | 1.80 (±1.30) |

| 5 | 2.20 (±1.10) | 2.40 (±0.55) | 3.20 (±0.45) |

| 6 | 2.20 (±1.64) | 1.60 (±0.55) | 1.40 (±0.55) |

| 7 | 2.00 (±1.00) | 3.40 (±0.55) | 3.80 (±0.45) |

| 8 | 2.20 (±1.64) | 2.60 (±0.55) | 3.40 (±0.55) |

| 9 | 2.40 (±1.34) | 1.60 (±0.89) | 1.60 (±0.89) |

| 10 | 2.80 (±1.30) | 2.60 (±1.14) | 3.40 (±0.55) |

| 11 | 2.00 (±1.00) | 1.60 (±0.55) | 1.40 (±0.55) |

| 12 | 2.20 (±1.10) | 3.40 (±0.89) | 3.80 (±0.45) |

| 13 | 1.80 (±0.84) | 2.60 (±1.14) | 3.40 (±0.55) |

| 14 | 1.00 (±0) | 1.60 (±1.34) | 1.80 (±1.30) |

| 15 | 1.40 (±0.55) | 2.80 (±1.30) | 3.00 (±1.00) |

| 16 | 1.00 (±0) | 1.00 (±0) | 2.20 (±0.84) |

| 17 | 1.00 (±0) | 1.40 (±0.55) | 1.40 (±0.55) |

| Question N° | T0 | T1 | T2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| 1 | 0.20 (±0.45) | 0.60 (±0.55) | 0 (±0) |

| 2 | 1.00 (±0.71) | 0.60 (±0.55) | 1.20 (±0.84) |

| 3 | 1.60 (±0.89) | 0 (±0) | 0 (±0) |

| 4 | 0.20 (±0.45) | 0 (±0) | 0 (±0) |

| 5 | 0 (±0) | 0 (±0) | 0 (±0) |

| 6 | 0.80 (±0.84) | 0 (±0) | 0 (±0) |

| 7 | 1.80 (±1.10) | 1.40 (±0.55) | 2.20 (±0.84) |

| 8 | 0.60 (±0.89) | 0 (±0) | 0.60 (±0.89) |

| 9 | 1.20 (±1.10) | 0.40 (±0.55) | 0.40 (±0.55) |

| 10 | 0.80 (±0.84) | 0.40 (±0.55) | 0.80 (±0.84) |

| 11 | 0 (±0) | 0 (±0) | 0 (±0) |

| 12 | 1.40 (±1.67) | 0.40 (±0.55) | 0.40 (±0.55) |

| 13 | 0.60 (±0.55) | 0 (±0) | 0 (±0) |

| 14 | 0.80 (±1.30) | 0 (±0) | 0.40 (±0.55) |

| 15 | 0.40 (±0.89) | 0.60 (±0.55) | 0.60 (±0.55) |

| 16 | 0 (±0) | 0.40 (±0.55) | 0.20 (±0.45) |

| 17 | 0.40 (±0.55) | 0.60 (±0.55) | 0.40 (±0.55) |

| 18 | 0 (±0) | 0 (±0) | 0 (±0) |

| 19 | 0.40 (±0.55) | 0.60 (±0.55) | 0 (±0) |

| 20 | 1.40 (±1.14) | 1.00 (±1.00) | 0.40 (±0.55) |

| 21 | 1.00 (±1.41) | 0 (±0) | 0 (±0) |

| 22 | 1.40 (±0.55) | 0 (±0) | 0 (±0) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Spano, A.; Petrone, F.; Di Simone, E.; De Leo, A.; Basili, P.; Terrenato, I.; Picano, M.A.; Piergentili, M.; Paterniani, A.; Iacorossi, L.; et al. The Effectiveness of Patient Education Interventions to Oncological Entero-Urostomy Patients and Caregivers: A Small Sample Size Pilot Study. Diseases 2025, 13, 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13060164

Spano A, Petrone F, Di Simone E, De Leo A, Basili P, Terrenato I, Picano MA, Piergentili M, Paterniani A, Iacorossi L, et al. The Effectiveness of Patient Education Interventions to Oncological Entero-Urostomy Patients and Caregivers: A Small Sample Size Pilot Study. Diseases. 2025; 13(6):164. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13060164

Chicago/Turabian StyleSpano, Alessandro, Fabrizio Petrone, Emanuele Di Simone, Aurora De Leo, Paolo Basili, Irene Terrenato, Maria Antonietta Picano, Marco Piergentili, Albina Paterniani, Laura Iacorossi, and et al. 2025. "The Effectiveness of Patient Education Interventions to Oncological Entero-Urostomy Patients and Caregivers: A Small Sample Size Pilot Study" Diseases 13, no. 6: 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13060164

APA StyleSpano, A., Petrone, F., Di Simone, E., De Leo, A., Basili, P., Terrenato, I., Picano, M. A., Piergentili, M., Paterniani, A., Iacorossi, L., & Panattoni, N. (2025). The Effectiveness of Patient Education Interventions to Oncological Entero-Urostomy Patients and Caregivers: A Small Sample Size Pilot Study. Diseases, 13(6), 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13060164