Artificial Sweeteners: A Double-Edged Sword for Gut Microbiome

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Current Status of Knowledge

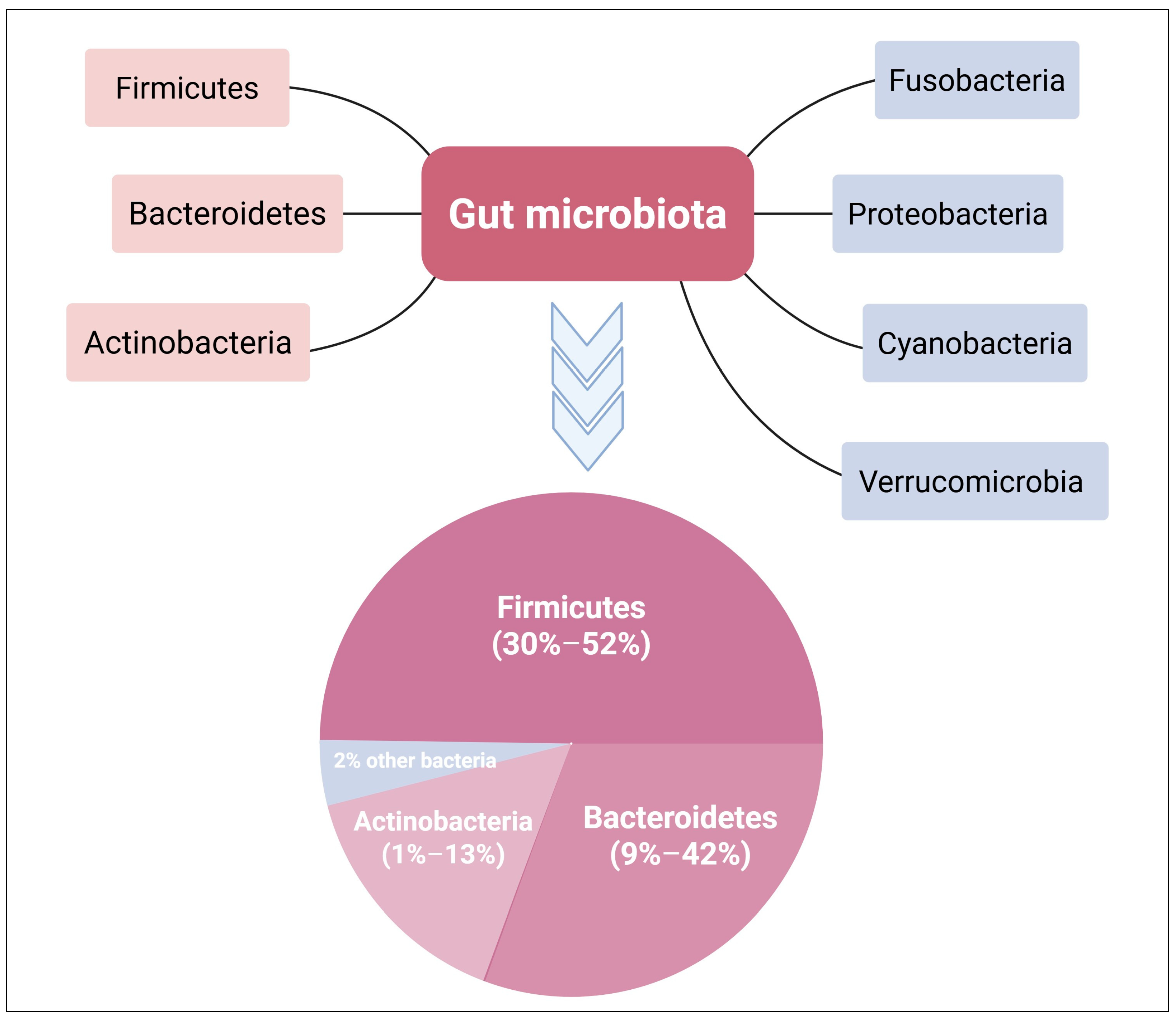

2.1. Gut Microbiome Community

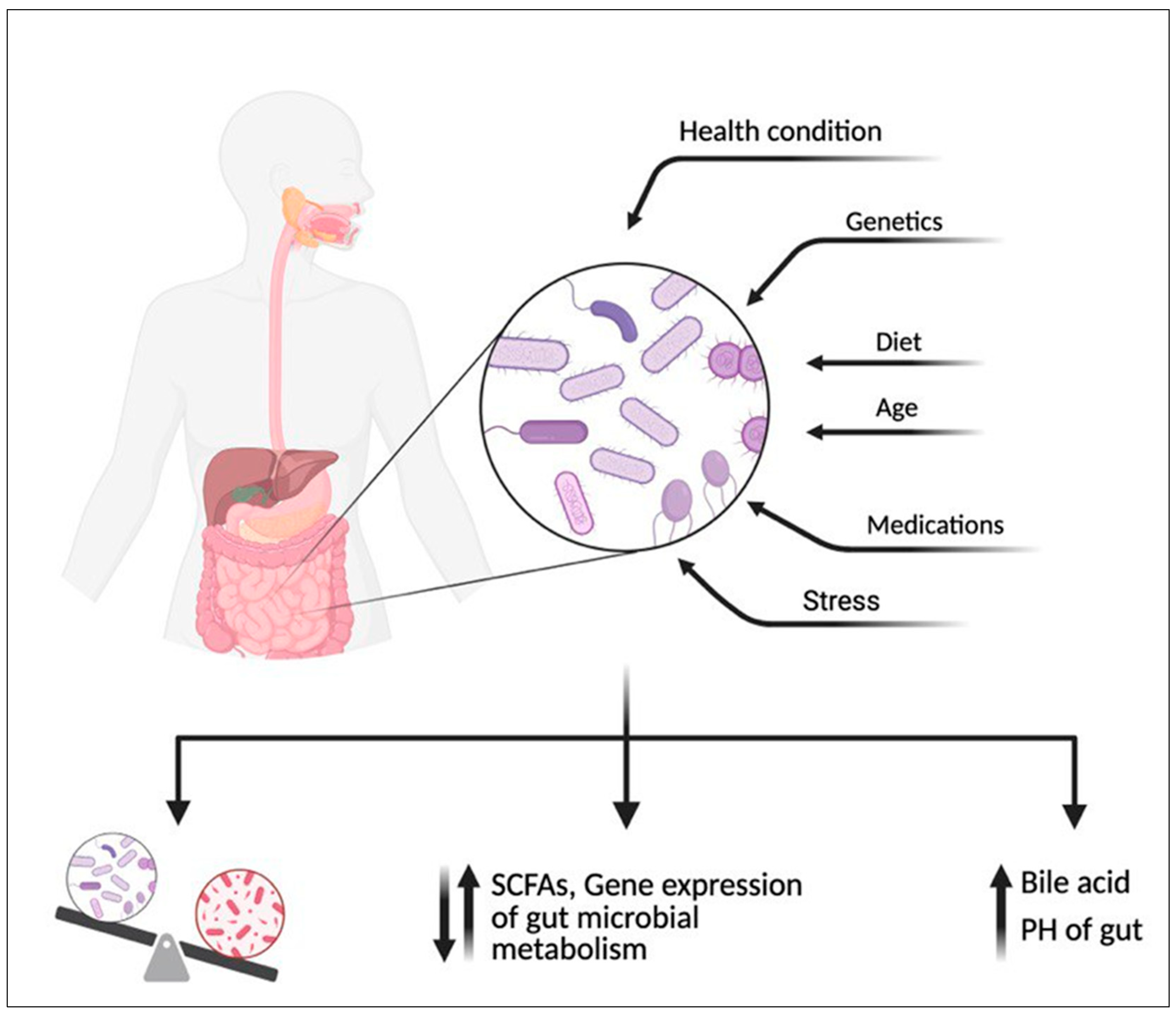

2.2. Effect of Diet on Gut Microbiome Community

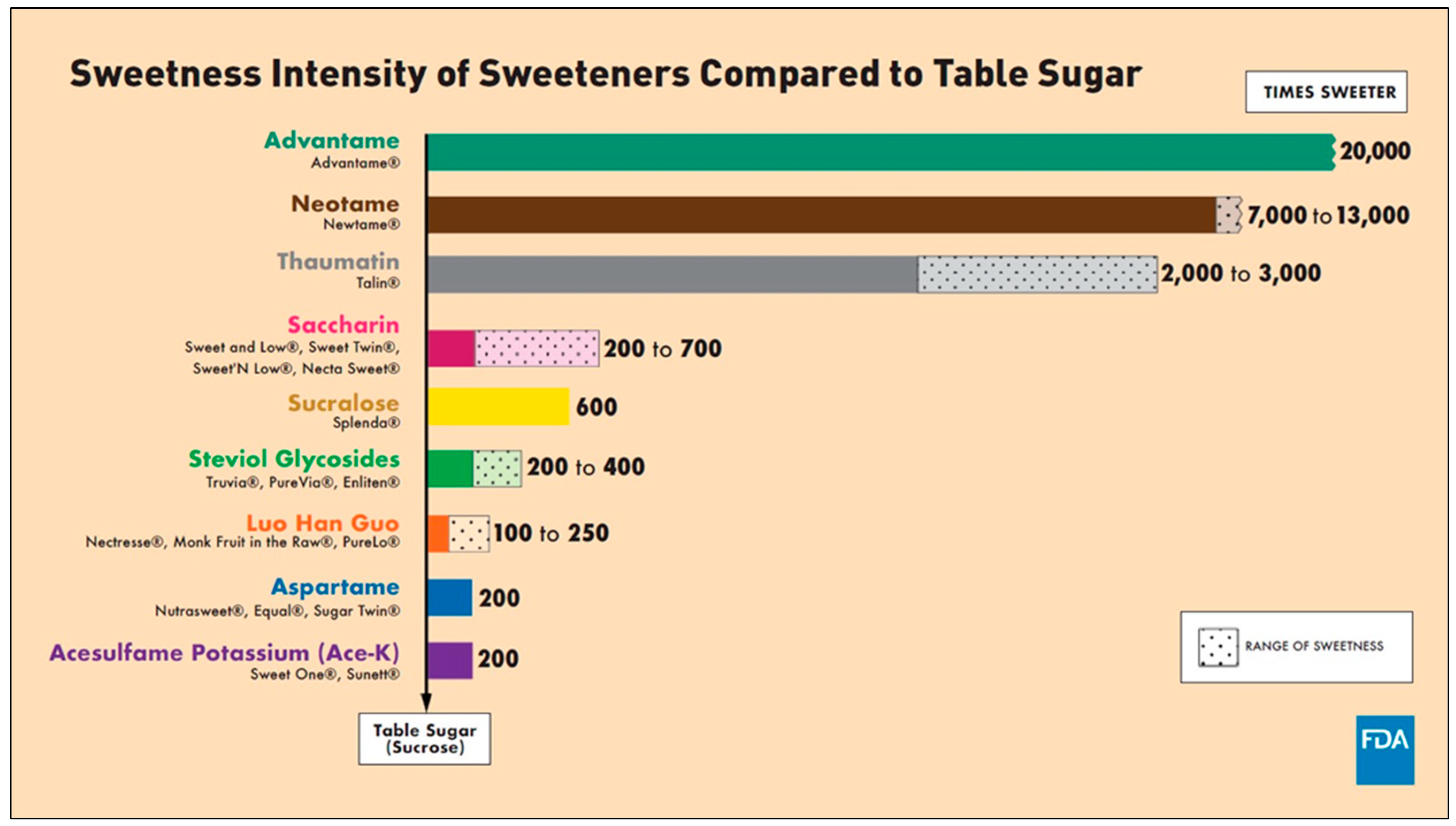

2.3. The History of NNS

3. Interactions Between NNS and Gut Microbiome

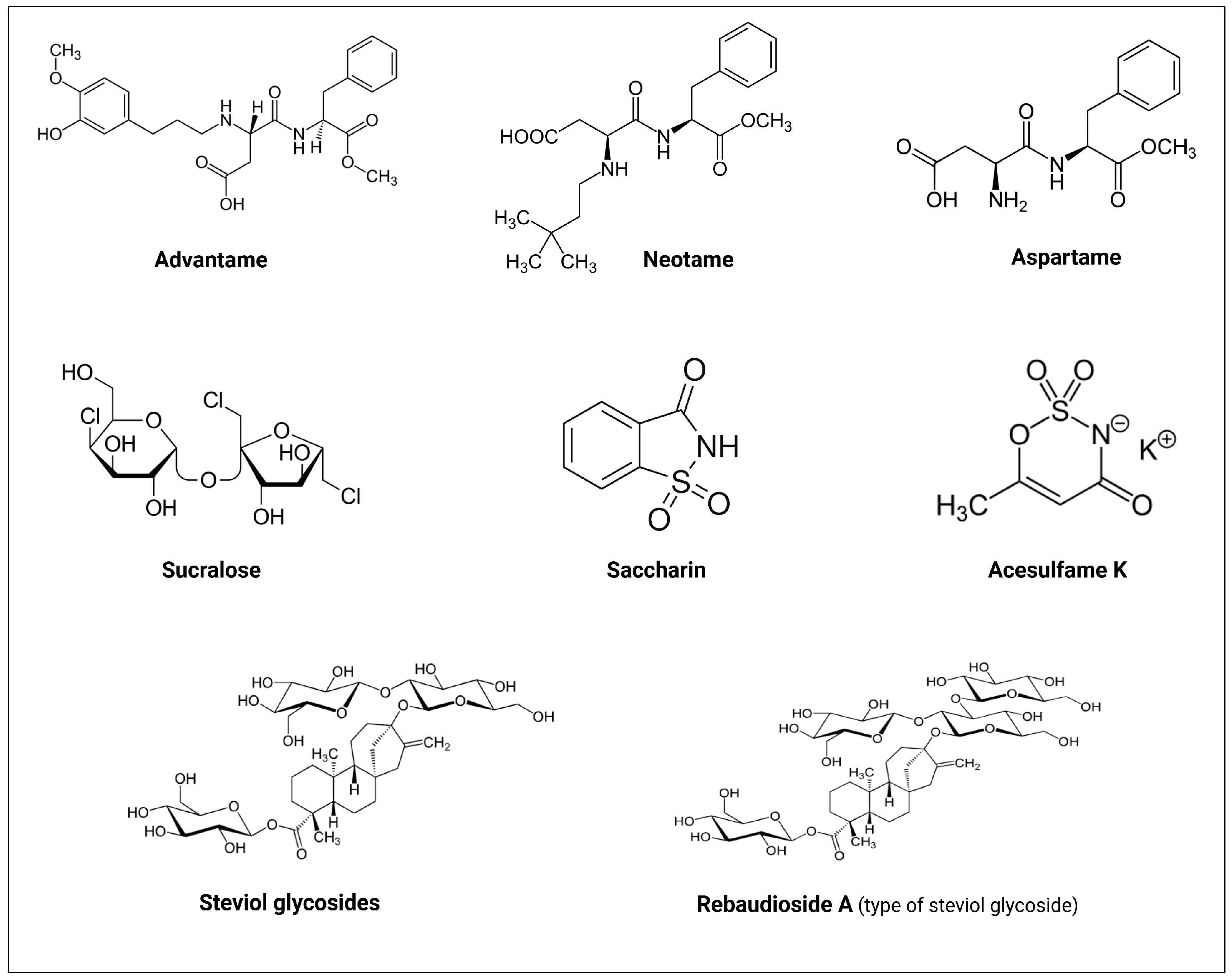

3.1. Acesulfame K (Ace-K)

3.2. Aspartame

3.3. Sucralose

3.4. Saccharin

3.5. Neotame

3.6. Stevia

| NNS | Study Type/Model | Dose and Exposure Time | Outcome(s) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acesulfame K (Ace-K) | Mice | 37.5 mg/kg bw/day for 4 weeks | 1. Altered the gut microbiome:

↑ Mucispirillum 2. Increased body weight gain of male mice. | [66] |

| Female mice | 0.1 or 0.2 mg Ace-K together with sucralose for 6 weeks | 1. Altered the gut microbiome of newborns: ↑ firmicutes ↓ Akkermansia muciniphila 2. Drastic metabolic change in newborns | [67] | |

| C57BL/6J mice | 150 mg/kg bw/day for 8 weeks | 1. Altered the gut microbiome ↓ Clostridiaceae, Ruminococcaceae, and Lachnospiraceae 2. Intestinal injury with enhanced lymphocyte migration to the intestinal mucosa. | [68] | |

| Male mice | 15 mg/kg bw/day for 8 weeks | No significant effects | [69] | |

| Mice | 40 or 120 mg/kg bw/day for 4 weeks | No significant effects | [70] | |

| Human | 1.7–33.2 mg/kg bw/day for 4 days | No significant effects | [71] | |

| Aspartame | Obese rat | High-fat diet + 5–7 mg/kg bw/day aspartame (in drinking water) for 8 weeks | 1. Altered the gut microbiome ↑ total bacteria, Enterobacteriaceae, and Clostridium leptum 2. Reduced caloric intake, weight gain, and body composition in the high-fat diet group. 3. Increased fasting glucose levels and impaired insulin-stimulated glucose elimination in the high-fat diet group. | [63] |

| Pregnant rats and their newborns | High fat/sucrose (HFS) diet + 5–7 mg/kg bw/day aspartame for 18 weeks | 1. ↑ Akkermansia muciniphila and Enterobacteriaceae in mother than their newborns. 2. ↓ Enterococcaceae, Enterococcus, and Parasutterella, as well as ↑ Clostridium cluster IV, in cecal matter from newborns. 3. ↑ Porphyromonadaceae in the guts of both male and female newborns. | [72] | |

| Human | 0.24 g/day | 1. Altered the gut microbiome. 2. ↓ Porphyromonas and Prevotella nanceiensis in oral microbiome. | [15] | |

| Human | 62.7 mg/day for 4 days | 1. No significant difference in bacterial abundance. 2. ↓ diversity of bacteria (from 24 to 7 phyla). | [71] | |

| Human | 0.425 g/day for 2 weeks | Little influence on gut microbiome composition or SCFA production | [73] | |

| Sucralose | SAMP1/YitFc mice | 3.5 mg/mL of Splenda® (sucralose maltodextrin, 1:99 w/w) | 1. Splenda® induced dysbiosis in all mice:

| [2] |

| C57BL/6J male mice | 5 mg/kg bw/day for 3 and 6 months | 1. Alterations in bacterial genera

↓ Lachnospiraceae, Dehalobacteriaceae, Anaerostipes, Staphylococcus, Peptostreptococcaceae, and Bacillus.

↓ Streptococcus, Lachnospiraceae, Dehalobacteriaceae, and Erysipelotrichaceae. 2. Following six months, ↑ expression of hepatic pro-inflammatory genes | [3] | |

| Mice |

|

| [75] | |

| Pregnant mice | Sucralose + 0.1- 0.2 mg Ace-K for 6 weeks | ↑ Firmicutes and ↓ Akkermansia muciniphila in newborns. | [67] | |

| Male mice | 15 mg/kg bw/day sucralose for 8 weeks | ↓ Clostridium cluster XIVa in the fecal microbiota | [69] | |

| Pregnant mice | Sucralose solution of 0.1 mg/mL for 6 weeks | 1. Maternal sucralose intake led to (in 3-weeks-old newborns):

| [76] | |

| Mice | 0.0003–0.3 mg/mL of sucralose | ↑ Tenacibaculum, Ruegeria, and Staphylococcus in the jejunum, ileum, and colon (mainly at 0.3 mg/mL dose). ↑ Allobaculum (at 0.3 mg/mL dose), which was found to have a positive association with diabetes. ↓ Lachnoclostridium and Lachnospiraceae present in cecum | [77] | |

| Human | 780 mg/day of sucralose for 7 days | No changes in glycemic control, insulin resistance, or intestinal microbiome at the phylum level in the sucralose-treated group | [78] | |

| Human | 0.136 g/day sucralose for 2 weeks | No significant effects | [73] | |

| Human | 48 mg/day sucralose for 10 weeks | 1. Gut microbiome dysbiosis

| [16] | |

| Saccharin | Mice | 5 mg/kg bw of saccharin for 5 weeks | 1. Gut microbiome dysbiosis

| [60] |

| Human | 5 mg/kg bw/day of saccharin for 6 days |

| [60] | |

| C57BL/6J male mice | 0.3 mg saccharin per mL in drinking water over 6 months | 1. Alterations in bacterial genera

↓ Anaerostipes and Ruminococcus

↓ Ruminococcus, Adlercreutzia, and Dorea 2. Following six months, ↑ expression of hepatic pro-inflammatory genes | [3] | |

| Human | 180 mg/day saccharin + 5820 mg/day glucose for 2 weeks | 1. Altered the gut microbiome. 2. ↓ Porphyromonas and Prevotella nanceiensis in oral microbiome. | [15] | |

| Piglets | Basal diet + 0.015% (w/w) saccharin for 2 weeks | ↑ Lactobacillus population, particularly Lactobacillus OTU4228 | [79,80] | |

| Dog | 0.02% of saccharin + eugenol for 10 days | No significant effects | [81] | |

| Mice | 250 mg/kg bw/day saccharin | No significant effects | [82] | |

| Mice | 20–100 mg/kg bw/day saccharin for 4 weeks | No significant effects | [70] | |

| Human | 400 mg/day saccharin for 2 weeks | No significant effects | [82] | |

| Neotame | Mice | 0.75 mg/kg bw/day neotame for 4 weeks | 1. ↑ two genera from the phylum Bacteroidetes—Bacteroides and an undefined genus in S24-7. 2. ↓ in three genera of the family Ruminococcaceae (Oscillospira, Ruminococcus, and one undefined genus) and five genera of Lachnospiraceae, including Blautia, Dorea, Ruminococcus, and two undefined genera. | [83] |

4. Possible Mechanisms for Interactions Between Gut Microbiome and NNS

5. Recommendations

6. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sylvetsky, A.C.; Rother, K.I. Trends in the consumption of low-calorie sweeteners. Physiol. Behav. 2016, 164, 446–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Palacios, A.; Harding, A.; Menghini, P.; Himmelman, C.; Retuerto, M.; Nickerson, K.P.; Lam, M.; Croniger, C.M.; McLean, M.H.; Durum, S.K.; et al. The artificial sweetener splenda promotes gut proteobacteria, dysbiosis, and myeloperoxidase reactivity in crohn’s disease-like ileitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2018, 24, 1005–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bian, X.; Chi, L.; Gao, B.; Tu, P.; Ru, H.; Lu, K. Gut microbiome response to sucralose and its potential role in inducing liver inflammation in mice. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debras, C.; Chazelas, E.; Srour, B.; Druesne-Pecollo, N.; Esseddik, Y.; Szabo de Edelenyi, F.; Agaësse, C.; De Sa, A.; Lutchia, R.; Gigandet, S.; et al. Artificial sweeteners and cancer risk: Results from the nutrinet-santé population-based cohort study. PLoS Med. 2022, 19, e1003950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramadan, M.; Hetta, H.F.; Saleh, M.M.; Ali, M.E.; Ahmed, A.A.; Salah, M. Alterations in skin microbiome mediated by radiotherapy and their potential roles in the prognosis of radiotherapy-induced dermatitis: A pilot study. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 5179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsherbiny, N.M.; Ramadan, M.; Faddan, N.H.A.; Hassan, E.A.; Ali, M.E.; El-Rehim, A.S.E.-D.A.; Abbas, W.A.; Abozaid, M.A.A.; Hassanin, E.; Mohamed, G.A.; et al. Impact of geographical location on the gut microbiota profile in egyptian children with type 1 diabetes mellitus: A pilot study. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2022, 15, 6173–6187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelin, M.; Kumar, J.; Vajravelu, L.K.; Satheesan, A.; Chaithanya, V.; Murugesan, R. Artificial sweeteners and their implications in diabetes: A review. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1411560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, Y.N.; Kamel, A.M.; Medhat, M.A.; Hetta, H.F. MicroRNA signatures in the pathogenesis and therapy of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin. Exp. Med. 2024, 24, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetta, H.F.; Ramadan, Y.N.; Alharbi, A.A.; Alsharef, S.; Alkindy, T.T.; Alkhamali, A.; Albalawi, A.S.; El Amin, H. Gut microbiome as a target of intervention in inflammatory bowel disease pathogenesis and therapy. Immuno 2024, 4, 400–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljabri, A.; Soliman, G.M.; Ramadan, Y.N.; Medhat, M.A.; Hetta, H.F. Biosimilars versus biological therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: Challenges and targeting strategies using drug delivery systems. Clin. Exp. Med. 2025, 25, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsherbiny, N.M.; Rammadan, M.; Hassan, E.A.; Ali, M.E.; El-Rehim, A.S.A.; Abbas, W.A.; Abozaid, M.A.A.; Hassanin, E.; Hetta, H.F. Autoimmune hepatitis: Shifts in gut microbiota and metabolic pathways among egyptian patients. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conz, A.; Salmona, M.; Diomede, L. Effect of non-nutritive sweeteners on the gut microbiota. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, A.M.; Ashwell, M.; Halford, J.C.G.; Hardman, C.A.; Maloney, N.G.; Raben, A. Low-calorie sweeteners in the human diet: Scientific evidence, recommendations, challenges and future needs. A symposium report from the FENS 2019 conference. J. Nutr. Sci. 2021, 10, e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, A.; Barlow, G.M.; Leite, G.; Rashid, M.; Parodi, G.; Wang, J.; Morales, W.; Weitsman, S.; Rezaie, A.; Pimentel, M.; et al. Consuming artificial sweeteners may alter the structure and function of duodenal microbial communities. iScience 2023, 26, 108530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suez, J.; Cohen, Y.; Valdés-Mas, R.; Mor, U.; Dori-Bachash, M.; Federici, S.; Zmora, N.; Leshem, A.; Heinemann, M.; Linevsky, R.; et al. Personalized microbiome-driven effects of non-nutritive sweeteners on human glucose tolerance. Cell 2022, 185, 3307–3328.e3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Méndez-García, L.A.; Bueno-Hernández, N.; Cid-Soto, M.A.; De León, K.L.; Mendoza-Martínez, V.M.; Espinosa-Flores, A.J.; Carrero-Aguirre, M.; Esquivel-Velázquez, M.; León-Hernández, M.; Viurcos-Sanabria, R.; et al. Ten-week sucralose consumption induces gut dysbiosis and altered glucose and insulin levels in healthy young adults. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, J.; Peng, J.; Hsiao, Y.-C.; Liu, C.-W.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Teitelbaum, T.; Wang, X.; Lu, K. Non/low-caloric artificial sweeteners and gut microbiome: From perturbed species to mechanisms. Metabolites 2024, 14, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozupone, C.A.; Stombaugh, J.I.; Gordon, J.I.; Jansson, J.K.; Knight, R. Diversity, stability and resilience of the human gut microbiota. Nature 2012, 489, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ley, R.E.; Turnbaugh, P.J.; Klein, S.; Gordon, J.I. Microbial ecology: Human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nature 2006, 444, 1022–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouskra, D.; Brézillon, C.; Bérard, M.; Werts, C.; Varona, R.; Boneca, I.G.; Eberl, G. Lymphoid tissue genesis induced by commensals through NOD1 regulates intestinal homeostasis. Nature 2008, 456, 507–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iebba, V.; Totino, V.; Gagliardi, A.; Santangelo, F.; Cacciotti, F.; Trancassini, M.; Mancini, C.; Cicerone, C.; Corazziari, E.; Pantanella, F.; et al. Eubiosis and dysbiosis: The two sides of the microbiota. New Microbiol. 2016, 39, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bäckhed, F.; Ley, R.E.; Sonnenburg, J.L.; Peterson, D.A.; Gordon, J.I. Host-bacterial mutualism in the human intestine. Science 2005, 307, 1915–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göker, M.; Oren, A. Valid publication of names of two domains and seven kingdoms of prokaryotes. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2024, 74, 006242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collado, M.C.; Cernada, M.; Baüerl, C.; Vento, M.; Pérez-Martínez, G. Microbial ecology and host-microbiota interactions during early life stages. Gut Microbes 2012, 3, 352–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasso, J.M.; Ammar, R.M.; Tenchov, R.; Lemmel, S.; Kelber, O.; Grieswelle, M.; Zhou, Q.A. Gut Microbiome-Brain Alliance: A Landscape View into Mental and Gastrointestinal Health and Disorders. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2023, 10, 1717–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arumugam, M.; Raes, J.; Pelletier, E.; Le Paslier, D.; Yamada, T.; Mende, D.R.; Fernandes, G.R.; Tap, J.; Bruls, T.; Batto, J.M.; et al. Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature 2011, 473, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanov, S.; Berlec, A.; Štrukelj, B. The influence of probiotics on the firmicutes/bacteroidetes ratio in the treatment of obesity and inflammatory bowel disease. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariat, D.; Firmesse, O.; Levenez, F.; Guimarăes, V.; Sokol, H.; Doré, J.; Corthier, G.; Furet, J.P. The firmicutes/bacteroidetes ratio of the human microbiota changes with age. BMC Microbiol. 2009, 9, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmas, V.; Pisanu, S.; Madau, V.; Casula, E.; Deledda, A.; Cusano, R.; Uva, P.; Vascellari, S.; Loviselli, A.; Manzin, A.; et al. Gut microbiota markers associated with obesity and overweight in Italian adults. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 5532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbaugh, P.J.; Ley, R.E.; Mahowald, M.A.; Magrini, V.; Mardis, E.R.; Gordon, J.I. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature 2006, 444, 1027–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberfroid, M.B.; Bornet, F.; Bouley, C.; Cummings, J.H. Colonic microflora: Nutrition and health. Summary and conclusions of an International Life Sciences Institute (ILSI) [Europe] workshop held in Barcelona, Spain. Nutr. Rev. 1995, 53, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hills, R.D., Jr.; Pontefract, B.A.; Mishcon, H.R.; Black, C.A.; Sutton, S.C.; Theberge, C.R. Gut microbiome: Profound implications for diet and disease. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäckhed, F.; Roswall, J.; Peng, Y.; Feng, Q.; Jia, H.; Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; Li, Y.; Xia, Y.; Xie, H.; Zhong, H.; et al. Dynamics and stabilization of the human gut microbiome during the first year of life. Cell Host Microbe 2015, 17, 690–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, N.; Yang, H. Factors affecting the composition of the gut microbiota, and its modulation. PeerJ 2019, 7, e7502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomova, A.; Bukovsky, I.; Rembert, E.; Yonas, W.; Alwarith, J.; Barnard, N.D.; Kahleova, H. The effects of vegetarian and vegan diets on gut microbiota. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, K. Gut microbiota: Filling up on fibre for a healthy gut. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 15, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, L.A.; Maurice, C.F.; Carmody, R.N.; Gootenberg, D.B.; Button, J.E.; Wolfe, B.E.; Ling, A.V.; Devlin, A.S.; Varma, Y.; Fischbach, M.A.; et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature 2014, 505, 559–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekirov, I.; Russell, S.L.; Antunes, L.C.; Finlay, B.B. Gut microbiota in health and disease. Physiol. Rev. 2010, 90, 859–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, K.; Wu, Z.-X.; Chen, X.-Y.; Wang, J.-Q.; Zhang, D.; Xiao, C.; Zhu, D.; Koya, J.B.; Wei, L.; Li, J.; et al. Microbiota in health and diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, K.B.; Leone, V.; Chang, E.B. Western diets, gut dysbiosis, and metabolic diseases: Are they linked? Gut Microbes 2017, 8, 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, C.; Hui, S.; Lu, W.; Cowan, A.J.; Morscher, R.J.; Lee, G.; Liu, W.; Tesz, G.J.; Birnbaum, M.J.; Rabinowitz, J.D. The small intestine converts dietary fructose into glucose and organic acids. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 351–361.e353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turnbaugh, P.J.; Bäckhed, F.; Fulton, L.; Gordon, J.I. Diet-induced obesity is linked to marked but reversible alterations in the mouse distal gut microbiome. Cell Host Microbe 2008, 3, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fava, F.; Gitau, R.; Griffin, B.A.; Gibson, G.R.; Tuohy, K.M.; Lovegrove, J.A. The type and quantity of dietary fat and carbohydrate alter faecal microbiome and short-chain fatty acid excretion in a metabolic syndrome ‘at-risk’ population. Int. J. Obes. 2013, 37, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosas-Villegas, A.; Sánchez-Tapia, M.; Avila-Nava, A.; Ramírez, V.; Tovar, A.R.; Torres, N. Differential effect of sucrose and fructose in combination with a high fat diet on intestinal microbiota and kidney oxidative stress. Nutrients 2017, 9, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, X.; Heeney, D.D.; Srisengfa, Y.T.; Chen, S.Y.; Slupsky, C.M.; Marco, M.L. Sucrose metabolism alters lactobacillus plantarum survival and interactions with the microbiota in the digestive tract. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2018, 94, fiy084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shwide-Slavin, C.; Swift, C.; Ross, T. Nonnutritive sweeteners: Where are we today? Diabetes Spectr. 2012, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, C.; Wylie-Rosett, J.; Gidding, S.S.; Steffen, L.M.; Johnson, R.K.; Reader, D.; Lichtenstein, A.H. Nonnutritive sweeteners: Current use and health perspectives: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 1798–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA. Sweetness Intensity of Sweeteners. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/168345/download (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Miller, P.E.; Perez, V. Low-calorie sweeteners and body weight and composition: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and prospective cohort studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 100, 765–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raben, A.; Vasilaras, T.H.; Møller, A.C.; Astrup, A. Sucrose compared with artificial sweeteners: Different effects on ad libitum food intake and body weight after 10 wk of supplementation in overweight subjects. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002, 76, 721–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA. High-Intensity Sweeteners. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/food-additives-petitions/high-intensity-sweeteners (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- FDA. Safe Levels of Sweeteners. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/168517/download (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Mooradian, A.D.; Smith, M.; Tokuda, M. The role of artificial and natural sweeteners in reducing the consumption of table sugar: A narrative review. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2017, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soejima, A.; Tanabe, A.S.; Takayama, I.; Kawahara, T.; Watanabe, K.; Nakazawa, M.; Mishima, M.; Yahara, T. Erratum to: Phylogeny and biogeography of the genus Stevia (Asteraceae: Eupatorieae): An example of diversification in the Asteraceae in the new world. J. Plant Res. 2017, 130, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneeman, B.O. Gastrointestinal physiology and functions. Br. J. Nutr. 2002, 88 (Suppl. S2), S159–S163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suez, J.; Korem, T.; Zilberman-Schapira, G.; Segal, E.; Elinav, E. Non-caloric artificial sweeteners and the microbiome: Findings and challenges. Gut Microbes 2015, 6, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Croom, E. Metabolism of xenobiotics of human environments. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2012, 112, 31–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calatayud Arroyo, M.; García Barrera, T.; Callejón Leblic, B.; Arias Borrego, A.; Collado, M.C. A review of the impact of xenobiotics from dietary sources on infant health: Early life exposures and the role of the microbiota. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 269, 115994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Ojeda, F.J.; Plaza-Díaz, J.; Sáez-Lara, M.J.; Gil, A. Effects of sweeteners on the gut microbiota: A review of experimental studies and clinical trials. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, S31–S48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suez, J.; Korem, T.; Zeevi, D.; Zilberman-Schapira, G.; Thaiss, C.A.; Maza, O.; Israeli, D.; Zmora, N.; Gilad, S.; Weinberger, A.; et al. Artificial sweeteners induce glucose intolerance by altering the gut microbiota. Nature 2014, 514, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhill, C. Gut microbiota: Not so sweet—Artificial sweeteners can cause glucose intolerance by affecting the gut microbiota. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2014, 10, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-López, Z.; Olvera-Hernández, V.; Ramos-García, M.; Méndez, J.D.; Guzmán-Priego, C.G.; Martínez-López, M.C.; García-Vázquez, C.; Alvarez-Villagomez, C.S.; Juárez-Rojop, I.E.; Díaz-Zagoya, J.C.; et al. Effects of sucralose supplementation on glycemic response, appetite, and gut microbiota in subjects with overweight or obesity: A randomized crossover study protocol. Methods Protoc. 2024, 7, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmnäs, M.S.; Cowan, T.E.; Bomhof, M.R.; Su, J.; Reimer, R.A.; Vogel, H.J.; Hittel, D.S.; Shearer, J. Low-dose aspartame consumption differentially affects gut microbiota-host metabolic interactions in the diet-induced obese rat. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e109841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walbolt, J.; Koh, Y. Non-nutritive sweeteners and their associations with obesity and type 2 diabetes. J. Obes. Metab. Syndr. 2020, 29, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, I.L.; Frese, S.A. Non-nutritive sweeteners and their impacts on the gut microbiome and host physiology. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 988144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bian, X.; Chi, L.; Gao, B.; Tu, P.; Ru, H.; Lu, K. The artificial sweetener acesulfame potassium affects the gut microbiome and body weight gain in CD-1 mice. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0178426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivier-Van Stichelen, S.; Rother, K.I.; Hanover, J.A. Maternal exposure to non-nutritive sweeteners impacts progeny’s metabolism and microbiome. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanawa, Y.; Higashiyama, M.; Kurihara, C.; Tanemoto, R.; Ito, S.; Mizoguchi, A.; Nishii, S.; Wada, A.; Inaba, K.; Sugihara, N.; et al. Acesulfame potassium induces dysbiosis and intestinal injury with enhanced lymphocyte migration to intestinal mucosa. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 36, 3140–3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uebanso, T.; Ohnishi, A.; Kitayama, R.; Yoshimoto, A.; Nakahashi, M.; Shimohata, T.; Mawatari, K.; Takahashi, A. Effects of low-dose non-caloric sweetener consumption on gut microbiota in mice. Nutrients 2017, 9, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murali, A.; Giri, V.; Cameron, H.J.; Sperber, S.; Zickgraf, F.M.; Haake, V.; Driemert, P.; Walk, T.; Kamp, H.; Rietjens, I.M.; et al. Investigating the gut microbiome and metabolome following treatment with artificial sweeteners acesulfame potassium and saccharin in young adult Wistar rats. Food Chem. Toxicol. Int. J. Publ. Br. Ind. Biol. Res. Assoc. 2022, 165, 113123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankenfeld, C.L.; Sikaroodi, M.; Lamb, E.; Shoemaker, S.; Gillevet, P.M. High-intensity sweetener consumption and gut microbiome content and predicted gene function in a cross-sectional study of adults in the United States. Ann. Epidemiol. 2015, 25, 736–742.e734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nettleton, J.E.; Cho, N.A.; Klancic, T.; Nicolucci, A.C.; Shearer, J.; Borgland, S.L.; Johnston, L.A.; Ramay, H.R.; Noye Tuplin, E.; Chleilat, F.; et al. Maternal low-dose aspartame and stevia consumption with an obesogenic diet alters metabolism, gut microbiota and mesolimbic reward system in rat dams and their offspring. Gut 2020, 69, 1807–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.Y.; Friel, J.; Mackay, D. The effects of non-nutritive artificial sweeteners, aspartame and sucralose, on the gut microbiome in healthy adults: Secondary outcomes of a randomized double-blinded crossover clinical trial. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobach, A.R.; Roberts, A.; Rowland, I.R. Assessing the in vivo data on low/no-calorie sweeteners and the gut microbiota. Food Chem. Toxicol. Int. J. Publ. Br. Ind. Biol. Res. Assoc. 2019, 124, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.P.; Browman, D.; Herzog, H.; Neely, G.G. Non-nutritive sweeteners possess a bacteriostatic effect and alter gut microbiota in mice. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0199080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Guo, Z.; Chen, D.; Li, L.; Song, X.; Liu, T.; Jin, G.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ajiguli, A.; et al. Maternal sucralose intake alters gut microbiota of offspring and exacerbates hepatic steatosis in adulthood. Gut Microbes 2020, 11, 1043–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Ma, L.; Lyu, W.; Peng, H.; Wang, X.; Ren, Y.; Li, J. Low dose of sucralose alter gut microbiome in mice. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 848392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomson, P.; Santibañez, R.; Aguirre, C.; Galgani, J.E.; Garrido, D. Short-term impact of sucralose consumption on the metabolic response and gut microbiome of healthy adults. Br. J. Nutr. 2019, 122, 856–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daly, K.; Darby, A.C.; Hall, N.; Nau, A.; Bravo, D.; Shirazi-Beechey, S.P. Dietary supplementation with lactose or artificial sweetener enhances swine gut Lactobacillus population abundance. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 111 (Suppl. S1), S30–S35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, K.; Darby, A.C.; Hall, N.; Wilkinson, M.C.; Pongchaikul, P.; Bravo, D.; Shirazi-Beechey, S.P. Bacterial sensing underlies artificial sweetener-induced growth of gut Lactobacillus. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 18, 2159–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, J.P.S.; He, F.; Mangian, H.F.; Oba, P.M.; De Godoy, M.R.C. Dietary supplementation of a fiber-prebiotic and saccharin-eugenol blend in extruded diets fed to dogs. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 97, 4519–4531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, J.; Smith, K.R.; Crouch, A.L.; Sharma, V.; Yi, F.; Vargova, V.; LaMoia, T.E.; Dupont, L.M.; Serna, V.; Tang, F.; et al. High-dose saccharin supplementation does not induce gut microbiota changes or glucose intolerance in healthy humans and mice. Microbiome 2021, 9, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, L.; Bian, X.; Gao, B.; Tu, P.; Lai, Y.; Ru, H.; Lu, K. Effects of the artificial sweetener neotame on the gut microbiome and fecal metabolites in mice. Molecules 2018, 23, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; McBain, A.J.; McLaughlin, J.T.; Stamataki, N.S. Consumption of the non-nutritive sweetener stevia for 12 weeks does not alter the composition of the human gut microbiota. Nutrients 2024, 16, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasti, A.N.; Nikolaki, M.D.; Synodinou, K.D.; Katsas, K.N.; Petsis, K.; Lambrinou, S.; Pyrousis, I.A.; Triantafyllou, K. The effects of stevia consumption on gut bacteria: Friend or foe? Microorganisms 2022, 10, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakr, E.A.E.; Massoud, M.I. Impact of prebiotic potential of stevia sweeteners-sugar used as synbiotic preparation on antimicrobial, antibiofilm, and antioxidant activities. LWT 2021, 144, 111260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, S.L.; Chiang, E.; Plantinga, A.; Carey, H.V.; Suen, G.; Swoap, S.J. Effect of stevia on the gut microbiota and glucose tolerance in a murine model of diet-induced obesity. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2020, 96, fiaa079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deniņa, I.; Semjonovs, P.; Fomina, A.; Treimane, R.; Linde, R. The influence of stevia glycosides on the growth of lactobacillus reuteri strains. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 58, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nettleton, J.E.; Klancic, T.; Schick, A.; Choo, A.C.; Shearer, J.; Borgland, S.L.; Chleilat, F.; Mayengbam, S.; Reimer, R.A. Low-dose stevia (rebaudioside A) consumption perturbs gut microbiota and the mesolimbic dopamine reward system. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepino, M.Y.; Bourne, C. Non-nutritive sweeteners, energy balance, and glucose homeostasis. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2011, 14, 391–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullicin, A.J.; Glendinning, J.I.; Lim, J. Cephalic phase insulin release: A review of its mechanistic basis and variability in humans. Physiol. Behav. 2021, 239, 113514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagne, L.; Piel, C.; Lallès, J.P. Effect of diet on mucin kinetics and composition: Nutrition and health implications. Nutr. Rev. 2004, 62, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, P.S.; Caria, C.R.P.; Gotardo, E.M.F.; Ribeiro, M.L.; Pedrazzoli, J.; Gambero, A. Artificial sweetener saccharin disrupts intestinal epithelial cells’ barrier function in vitro. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 3815–3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shil, A.; Olusanya, O.; Ghufoor, Z.; Forson, B.; Marks, J.; Chichger, H. Artificial sweeteners disrupt tight junctions and barrier function in the intestinal epithelium through activation of the sweet taste receptor, T1R3. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tailford, L.E.; Crost, E.H.; Kavanaugh, D.; Juge, N. Mucin glycan foraging in the human gut microbiome. Front. Genet. 2015, 6, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plovier, H.; Everard, A.; Druart, C.; Depommier, C.; Van Hul, M.; Geurts, L.; Chilloux, J.; Ottman, N.; Duparc, T.; Lichtenstein, L.; et al. A purified membrane protein from Akkermansia muciniphila or the pasteurized bacterium improves metabolism in obese and diabetic mice. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Lu, J.; Bond, P.L.; Guo, J. Nonnutritive sweeteners can promote the dissemination of antibiotic resistance through conjugative gene transfer. ISME J. 2021, 15, 2117–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eyk, A.D. The effect of five artificial sweeteners on Caco-2, HT-29 and HEK-293 cells. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 2015, 38, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swithers, S.E. Artificial sweeteners produce the counterintuitive effect of inducing metabolic derangements. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. TEM 2013, 24, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, M.V.; Small, D.M. Physiological mechanisms by which non-nutritive sweeteners may impact body weight and metabolism. Physiol. Behav. 2015, 152, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Pozo, S.; Gómez-Martínez, S.; Díaz, L.E.; Nova, E.; Urrialde, R.; Marcos, A. Potential effects of sucralose and saccharin on gut microbiota: A review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Nettleton, J.E.; Gänzle, M.G.; Reimer, R.A. A metagenomics investigation of intergenerational effects of non-nutritive sweeteners on gut microbiome. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 795848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Vitetta, L. The role of butyrate in attenuating pathobiont-induced hyperinflammation. Immune Netw. 2020, 20, e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cholan, P.M.; Han, A.; Woodie, B.R.; Watchon, M.; Kurz, A.R.; Laird, A.S.; Britton, W.J.; Ye, L.; Holmes, Z.C.; McCann, J.R.; et al. Conserved anti-inflammatory effects and sensing of butyrate in zebrafish. Gut Microbes 2020, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otten, B.M.J.; Sthijns, M.; Troost, F.J. A combination of acetate, propionate, and butyrate increases glucose uptake in C2C12 myotubes. Nutrients 2023, 15, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Callaghan, A.; van Sinderen, D. Bifidobacteria and their role as members of the human gut microbiota. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azad, M.A.K.; Sarker, M.; Li, T.; Yin, J. Probiotic species in the modulation of gut microbiota: An overview. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 9478630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bien, J.; Palagani, V.; Bozko, P. The intestinal microbiota dysbiosis and clostridium difficile infection: Is there a relationship with inflammatory bowel disease? Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2013, 6, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirsepasi-Lauridsen, H.C.; Vallance, B.A.; Krogfelt, K.A.; Petersen, A.M. Escherichia coli pathobionts associated with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2019, 32, e00060-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Yang, M.; Dong, W.; Liu, T.; Song, X.; Gu, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y.; Abla, Z.; Qiao, X.; et al. Gut dysbiosis and abnormal bile acid metabolism in colitis-associated cancer. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2021, 2021, 6645970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuei, J.; Chau, T.; Mills, D.; Wan, Y.J. Bile acid dysregulation, gut dysbiosis, and gastrointestinal cancer. Exp. Biol. Med. 2014, 239, 1489–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppel, N.; Maini Rekdal, V.; Balskus, E.P. Chemical transformation of xenobiotics by the human gut microbiota. Science 2017, 356, eaag2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanogiannopoulos, P.; Bess, E.N.; Carmody, R.N.; Turnbaugh, P.J. The microbial pharmacists within us: A metagenomic view of xenobiotic metabolism. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 14, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHO Advises Not to Use Non-Sugar Sweeteners for Weight Control in Newly Released Guideline. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/15-05-2023-who-advises-not-to-use-non-sugar-sweeteners-for-weight-control-in-newly-released-guideline (accessed on 1 May 2024).

| NNS | FDA Approval Year | Acceptable Daily Intake (ADI) | Daily Sweetener Packet Limit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Advantame | 2014 | 32.8 mg/kg bw/d | 4920 |

| Neotame | 2002 | 0.3 mg/kg bw/d | 23 |

| Sucralose | 1998 | 5 mg/kg bw/d | 23 |

| Saccharin | 1977 | 15 mg/kg bw/d | 45 |

| Aspartame | 1981 | 50 mg/kg bw/d | 75 |

| Acesulfame K | 1988 | 15 mg/kg bw/d | 23 |

| Steviol glycosides | 2008 | 4 mg/kg bw/d | 9 |

| Rebaudioside A (type of steviol glycoside) | 2008 | 12 mg/kg bw/d | 27 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hetta, H.F.; Sirag, N.; Elfadil, H.; Salama, A.; Aljadrawi, S.F.; Alfaifi, A.J.; Alwabisi, A.N.; AbuAlhasan, B.M.; Alanazi, L.S.; Aljohani, Y.A.; et al. Artificial Sweeteners: A Double-Edged Sword for Gut Microbiome. Diseases 2025, 13, 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13040115

Hetta HF, Sirag N, Elfadil H, Salama A, Aljadrawi SF, Alfaifi AJ, Alwabisi AN, AbuAlhasan BM, Alanazi LS, Aljohani YA, et al. Artificial Sweeteners: A Double-Edged Sword for Gut Microbiome. Diseases. 2025; 13(4):115. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13040115

Chicago/Turabian StyleHetta, Helal F., Nizar Sirag, Hassabelrasoul Elfadil, Ayman Salama, Sara F. Aljadrawi, Amani J. Alfaifi, Asma N. Alwabisi, Bothinah M. AbuAlhasan, Layan S. Alanazi, Yara A. Aljohani, and et al. 2025. "Artificial Sweeteners: A Double-Edged Sword for Gut Microbiome" Diseases 13, no. 4: 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13040115

APA StyleHetta, H. F., Sirag, N., Elfadil, H., Salama, A., Aljadrawi, S. F., Alfaifi, A. J., Alwabisi, A. N., AbuAlhasan, B. M., Alanazi, L. S., Aljohani, Y. A., Ramadan, Y. N., Abd Ellah, N. H., & Algammal, A. M. (2025). Artificial Sweeteners: A Double-Edged Sword for Gut Microbiome. Diseases, 13(4), 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13040115