Surgery Versus Chemoradiation Therapy for Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Multidimensional Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Procedures

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AJCC | American Joint Committee of Cancer |

| CRT | ChemoRadiation Therapy |

| DT | Distress Thermometer |

| EORTC | European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer |

| ESS | Epworth Sleepiness Scale |

| HADS | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale |

| HPV | Human PapillomaVirus |

| IMRT | Intensity Modulated Radiotherapy |

| IQR | InterQuartile Range |

| MDADI | MD Anderson Dysphagia Inventory |

| MUST | Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool |

| OPSCC | OroPharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma |

| OSAS | Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome |

| PSQI | Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index |

| QoL | Quality of Life |

| RT | Radiation Therapy |

| SHI | Speech Handicap Index |

| SRT | Surgery and adjuvant Radiation Therapy |

| TNM | Tumor Node Metastasis |

| TORS | TransOral Robotic Surgery |

References

- Riva, G.; Pecorari, G.; Biolatti, M.; Pautasso, S.; Cigno, I.L.; Garzaro, M.; Dell’oste, V.; Landolfo, S. PYHIN genes as potential biomarkers for prognosis of human papillomavirus-positive or -negative head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2019, 46, 3333–3347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arboleda, L.P.A.; de Carvalho, G.B.; Santos-Silva, A.R.; Fernandes, G.A.; Vartanian, J.G.; Conway, D.I.; Virani, S.; Brennan, P.; Kowalski, L.P.; Curado, M.P. Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Oral Cavity, Oropharynx, and Larynx: A Scoping Review of Treatment Guidelines Worldwide. Cancers 2023, 15, 4405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meccariello, G.; Cammaroto, G.; Iannella, G.; De Vito, A.; Ciorba, A.; Bianchini, C.; Corazzi, V.; Pelucchi, S.; Vicini, C.; Capaccio, P. Transoral robotic surgery for oropharyngeal cancer in the era of chemoradiation therapy. Auris Nasus Larynx 2022, 49, 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, J.; Masterson, L.; Dwivedi, R.C.; Riffat, F.; Benson, R.; Jefferies, S.; Jani, P.; Tysome, J.R.; Nutting, C. Minimally invasive surgery versus radiotherapy/chemoradiotherapy for small-volume primary oropharyngeal carcinoma. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 2016, CD010963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, A.C.; Theurer, J.; Prisman, E.; Read, N.; Berthelet, E.; Tran, E.; Fung, K.; de Almeida, J.R.; Bayley, A.; Goldstein, D.P.; et al. Radiotherapy Versus Transoral Robotic Surgery for Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Final Results of the ORATOR Randomized Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 4023–4028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roets, E.; Tukanova, K.; Govarts, A.; Specenier, P. Quality of life in oropharyngeal cancer: A structured review of the literature. Support. Care Cancer 2018, 26, 2511–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choby, G.W.; Kim, J.; Ling, D.C.; Abberbock, S.; Mandal, R.; Kim, S.; Ferris, R.L.; Duvvuri, U. Transoral robotic surgery alone for oropharyngeal cancer: Quality-of-life outcomes. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 2015, 141, 499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeman, J.E.; Li, J.-G.; Pei, X.; Venigalla, P.; Zumsteg, Z.S.; Katsoulakis, E.; Lupovitch, E.; McBride, S.M.; Tsai, C.J.; Boyle, J.O.; et al. Patterns of Treatment Failure and Postrecurrence Outcomes Among Patients With Locally Advanced Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma After Chemoradiotherapy Using Modern Radiation Techniques. JAMA Oncol. 2017, 3, 1487–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsou, Y.A.; Chang, W.D.; Meng, N.H.; Hua, C.H. Analysis of Swallowing Functional Preservation by Surgical Versus CRT After Induction Chemotherapy for Oropharyngeal Cancer. Cancers 2024, 16, 3658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baude, J.; Guigou, C.; Thibouw, D.; Vulquin, N.; Folia, M.; Constantin, G.; Boustani, J.; Duvillard, C.; Ladoire, S.; Truc, G.; et al. Definitive radio(chemo)therapy versus upfront surgery in the treatment of HPV-related localized or locally advanced oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0307658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilz, M.J.; Gamper, E.-M.; Efficace, F.; Arraras, J.I.; Nolte, S.; Liegl, G.; Rose, M.; Giesinger, J.M.; EORTC Quality of Life Group. EORTC QLQ-C30 general population normative data for Italy by sex, age and health condition: An analysis of 1036 individuals. BMC Public Health 2021, 22, 1040. [Google Scholar]

- Bjordal, K.; Hammerlid, E.; Ahlner-Elmqvist, M.; De Graeff, A.; Boysen, M.; Evensen, J.F.; Biorklund, A.; De Leeuw, J.R.; Fayers, P.M.; Jannert, M.; et al. Quality of life in head and neck cancer patients: Validation of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-H&N35. J. Clin. Oncol. 1999, 17, 1008–1019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Curcio, G.; Tempesta, D.; Scarlata, S.; Marzano, C.; Moroni, F.; Rossini, P.M.; Ferrara, M.; De Gennaro, L. Validity of the Italian version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). Neurol. Sci. 2013, 34, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pecorari, G.; Moglio, S.; Gamba, D.; Briguglio, M.; Cravero, E.; Baduel, E.S.; Riva, G. Sleep Quality in Head and Neck Cancer. Curr. Oncol. 2024, 31, 7000–7013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, H.Y.; Chen, P.Y.; Chuang, L.P.; Chen, N.H.; Tu, Y.K.; Hsieh, Y.J.; Wang, Y.C.; Guilleminault, C. Diagnostic accuracy of the Berlin questionnaire, STOP-BANG, STOP, and Epworth sleepiness scale in detecting obstructive sleep apnea: A bivariate meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 2017, 36, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, M.T.; Malafaia, S.; Moutinho Dos Santos, J.; Roth, T.; Marques, D.R. Epworth sleepiness scale: A meta-analytic study on the internal consistency. Sleep Med. 2023, 109, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ownby, K.K. Use of the Distress Thermometer in Clinical Practice. J. Adv. Pract. Oncol. 2019, 10, 175–179. [Google Scholar]

- Snaith, R.P. The Hospital Anxiety And Depression Scale. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2003, 1, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, A.Y.; Frankowski, R.; Bishop-Leone, J.; Hebert, T.; Leyk, S.; Lewin, J.; Goepfert, H. The Development and Validation of a Dysphagia-Specific Quality-of-Life Questionnaire for Patients With Head and Neck Cancer. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 2001, 127, 870–876. [Google Scholar]

- Riva, G.; Elia, G.; Sapino, S.; Ravera, M.; Pecorari, G. Validation and Reliability of the Italian Version of the Speech Handicap Index. Folia Phoniatr. Logop. 2020, 72, 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Boléo-Tomé, C.; Monteiro-Grillo, I.; Camilo, M.; Ravasco, P. Validation of the Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST) in cancer. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 108, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iorio, G.C.; Arcadipane, F.; Martini, S.; Ricardi, U.; Franco, P. Decreasing treatment burden in HPV-related OPSCC: A systematic review of clinical trials. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2021, 160, 103243. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Santo, B.; Bertini, N.; Cattaneo, C.G.; De Matteis, S.; De Franco, P.; Grassi, R.; Iorio, G.C.; Longo, S.; Boldrini, L.; Piras, A.; et al. Nutritional counselling for head and neck cancer patients treated with (chemo)radiation therapy: Why, how, when, and what? Front. Oncol. 2024, 13, 1240913. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, P.; Potenza, I.; Schena, M.; Riva, G.; Pecorari, G.; Demo, P.G.; Fasolis, M.; Moretto, F.; Garzaro, M.; Di Muzio, J.; et al. Induction Chemotherapy and Sequential Concomitant Chemo-radiation in Locally Advanced Head and Neck Cancers: How Induction-phase Intensity and Treatment Breaks May Impact on Clinical Outcomes. Anticancer. Res. 2015, 35, 6247–6254. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, P.H.; Stuut, M.; Wuerdemann, N.; Möllenhoff, K.; Suchan, M.; Eckel, H.; Wolber, P.; Sharma, S.J.; Kämmerer, F.; Langer, C.; et al. Upfront Surgery vs. Primary Chemoradiation in an Unselected, Bicentric Patient Cohort with Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma-A Matched-Pair Analysis. Cancers 2021, 13, 5265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harari, P.M.; Harris, J.; Kies, M.S.; Myers, J.N.; Jordan, R.C.; Gillison, M.L.; Foote, R.L.; Machtay, M.; Rotman, M.; Khuntia, D.; et al. Postoperative Chemoradiotherapy and Cetuximab for High-Risk Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck: Radiation Therapy Oncology Group RTOG-0234. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 2486–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehanna, H.; Paleri, V.; West, C.M.L.; Nutting, C. Head and neck cancer–Part 1: Epidemiology, presentation, and prevention. BMJ 2010, 341, c4684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pasquale, G.; Mancin, S.; Matteucci, S.; Cattani, D.; Pastore, M.; Franzese, C.; Scorsetti, M.; Mazzoleni, B. Nutritional prehabilitation in head and neck cancer: A systematic review of literature. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2023, 58, 326–334. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristics | Group A n (%) | Group B n (%) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.705 | ||

| Male | 9 (60.0) | 10 (66.7) | |

| Female | 6 (40.0) | 5 (33.3) | |

| Smoking | 0.593 | ||

| Never | 3 (20.0) | 3 (20.0) | |

| Former | 11 (73.3) | 12 (80.0) | |

| Active | 1 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Alcohol assumption (>2 drinks for men, >1 drink for women) | 0.283 | ||

| Never | 14 (93.3) | 12 (80.0) | |

| Active | 1 (6.7) | 3 (20.0) | |

| Tumor site | 0.179 | ||

| Tonsillar lodge | 7 (46.7) | 8 (53.4) | |

| Tongue base | 3 (20.0) | 5 (33.3) | |

| Soft palate | 4 (26.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Posterior wall | 1 (6.6) | 2 (13.4) | |

| Tumor stage * | 0.220 | ||

| I | 8 (53.4) | 3 (20.0) | |

| II | 2 (13.3) | 2 (13.3) | |

| III | 3 (20.0) | 4 (26.7) | |

| IV | 2 (13.4) | 6 (40.0) | |

| HPV | 0.705 | ||

| Positive | 9 (60.0) | 10 (66.7) | |

| Negative | 6 (40.0) | 5 (33.3) |

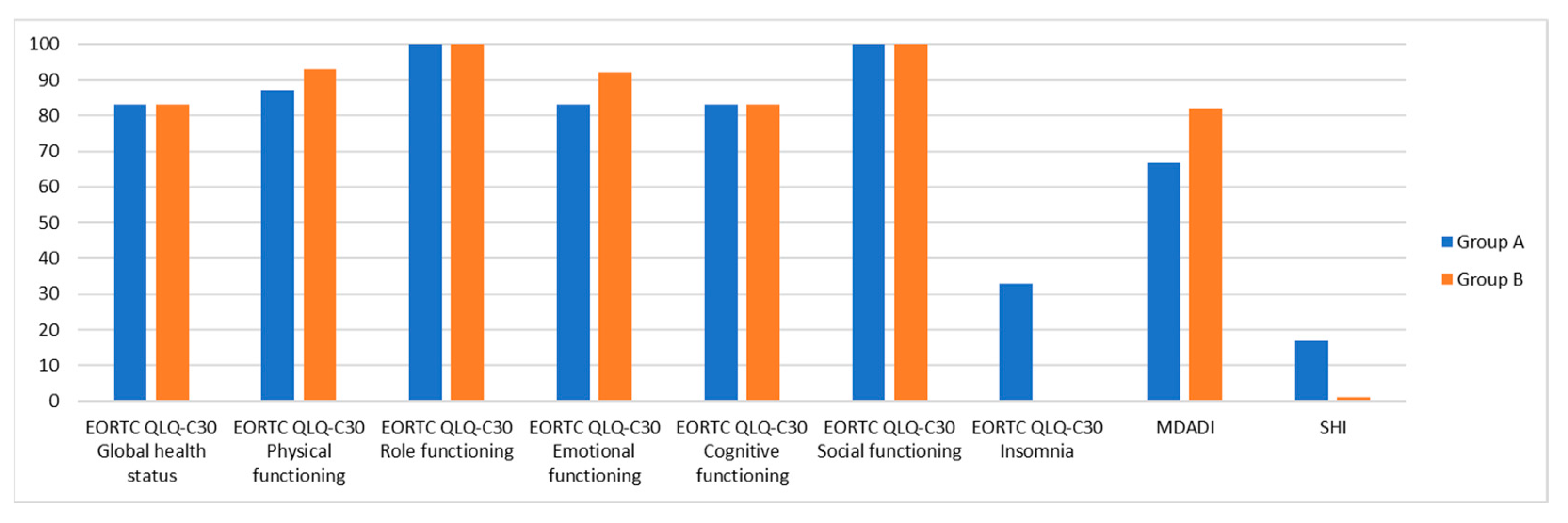

| Scores | Group A Median (IQR) | Group B Median (IQR) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| EORTC QLQ-C30 | |||

| Global health status | 83.33 (33.3) | 83.33 (8.33) | 0.461 |

| Physical functioning | 86.67 (20.00) | 93.33 (20.00) | 0.567 |

| Role functioning | 100.00 (33.33) | 100.00 (33.33) | 0.683 |

| Emotional functioning | 83.33 (33.33) | 91.67 (33.33) | 0.870 |

| Cognitive functioning | 83.33 (16.67) | 83.33 (16.67) | 0.838 |

| Social functioning | 100.00 (33.33) | 100.00 (33.33) | 0.486 |

| Fatigue | 22.22 (33.33) | 22.22 (33.33) | 0.713 |

| Nausea and vomiting | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.744 |

| Pain | 0.00 (16.67) | 0.00 (33.33) | 0.624 |

| Dyspnea | 0.00 (33.33) | 0.00 (33.33) | 0.935 |

| Insomnia | 33.33 (33.33) | 0.00 (33.33) | 0.217 |

| Appetite loss | 0.00 (33.33) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.624 |

| Constipation | 0.00 (33.33) | 0.00 (33.33) | 0.935 |

| Diarrhea | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.744 |

| Financial difficulties | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (66.67) | 0.116 |

| EORTC H&N35 | |||

| Pain in the mouth | 0.00 (25.00) | 8.33 (25.00) | 0.806 |

| Swallowing | 8.33 (33.33) | 8.33 (16.67) | 0.902 |

| Senses | 0.00 (33.33) | 0.00 (16.67) | 0.567 |

| Speech | 22.22 (22.22) | 0.00 (22.22) | 0.567 |

| Social eating | 8.33 (16.67) | 0.00 (16.67) | 0.305 |

| Social contact | 0.00 (13.33) | 0.00 (6.67) | 0.389 |

| Sexuality | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (33.33) | 0.250 |

| Problems with teeth | 0.00 (33.33) | 0.00 (33.33) | 0.870 |

| Problems opening mouth | 0.00 (66.67) | 0.00 (33.33) | 0.935 |

| Dry mouth | 0.00 (66.67) | 33.33 (66.67) | 0.567 |

| Sticky saliva | 33.33 (66.67) | 33.33 (33.33) | 0.683 |

| Cough | 0.00 (33.33) | 0.00 (33.33) | 0.436 |

| Felt ill | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.512 |

| Painkillers | 0.00 (100.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.775 |

| Nutritional supplements | 0.00 (100.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.217 |

| Feeding tube | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | 1.000 |

| Weight loss | 0.00 (100.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.367 |

| Weight gain | 0.00 (100.00) | 0.00 (100.00) | 1.000 |

| Scores | Group A Median (IQR) | Group B Median (IQR) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESS | 2 (10) | 1 (3) | 0.233 |

| PSQI | |||

| Global score | 7 (6) | 5 (5) | 0.325 |

| Sleep quality | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 0.595 |

| Sleep latency | 1 (2) | 1 (1) | 0.539 |

| Sleep duration | 1 (3) | 0 (1) | 0.217 |

| Habitual sleep efficiency | 1 (3) | 0 (3) | 0.624 |

| Sleep disturbances | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0.595 |

| Use of sleeping medications | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Daytime dysfunction | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 0.595 |

| Scores | Group A Median (IQR) | Group B Median (IQR) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| MDADI | 67 (21) | 82 (18) | 0.089 |

| SHI | 17 (36) | 1 (7) | 0.161 |

| DT | 2 (4) | 1 (5) | 0.870 |

| HADS | |||

| Anxiety | 5 (4) | 5 (4) | 1.000 |

| Depression | 5 (7) | 2 (5) | 0.116 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Riva, G.; Gamba, D.; Moglio, S.; Iorio, G.C.; Cavallin, C.; Ricardi, U.; Airoldi, M.; Canale, A.; Albera, A.; Pecorari, G. Surgery Versus Chemoradiation Therapy for Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Multidimensional Cross-Sectional Study. Diseases 2025, 13, 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13040106

Riva G, Gamba D, Moglio S, Iorio GC, Cavallin C, Ricardi U, Airoldi M, Canale A, Albera A, Pecorari G. Surgery Versus Chemoradiation Therapy for Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Multidimensional Cross-Sectional Study. Diseases. 2025; 13(4):106. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13040106

Chicago/Turabian StyleRiva, Giuseppe, Dario Gamba, Simone Moglio, Giuseppe Carlo Iorio, Chiara Cavallin, Umberto Ricardi, Mario Airoldi, Andrea Canale, Andrea Albera, and Giancarlo Pecorari. 2025. "Surgery Versus Chemoradiation Therapy for Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Multidimensional Cross-Sectional Study" Diseases 13, no. 4: 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13040106

APA StyleRiva, G., Gamba, D., Moglio, S., Iorio, G. C., Cavallin, C., Ricardi, U., Airoldi, M., Canale, A., Albera, A., & Pecorari, G. (2025). Surgery Versus Chemoradiation Therapy for Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Multidimensional Cross-Sectional Study. Diseases, 13(4), 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13040106