Quality of Life and Stress-Related Psychological Distress Among Patients with Cervical Cancer: A Cross-Sectional Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethical Considerations

2.2. Participant Selection and Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Collection Instruments

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Literature Findings

4.2. Study Limitations and Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Small, W., Jr.; Bacon, M.A.; Bajaj, A.; Chuang, L.T.; Fisher, B.J.; Harkenrider, M.M.; Jhingran, A.; Kitchener, H.C.; Mileshkin, L.R.; Viswanathan, A.N.; et al. Cervical cancer: A global health crisis. Cancer 2017, 123, 2404–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbyn, M.; Weiderpass, E.; Bruni, L.; de Sanjosé, S.; Saraiya, M.; Ferlay, J.; Bray, F. Estimates of incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in 2018: A worldwide analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e191–e203, Erratum in Lancet Glob. Health 2022, 10, e41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pearman, T. Quality of life and psychosocial adjustment in gynecologic cancer survivors. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2003, 1, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ware, J.E., Jr.; Sherbourne, C.D. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med. Care 1992, 30, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Whoqol Group. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF Quality of Life Assessment. Psychol. Med. 1998, 28, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A Global Measure of Perceived Stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aaronson, N.K.; Ahmedzai, S.; Bergman, B.; Bullinger, M.; Cull, A.; Duez, N.J.; Filiberti, A.; Flechtner, H.; Fleishman, S.B.; De Haes, J.C.J.M.; et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A Quality-of-Life Instrument for Use in International Clinical Trials in Oncology. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1993, 85, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, A.-L. Recent Developments in Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccinology. Viruses 2023, 15, 1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hermann, M.; Goerling, U.; Hearing, C.; Mehnert-Theuerkauf, A.; Hornemann, B.; Hövel, P.; Reinicke, S.; Zingler, H.; Zimmermann, T.; Ernst, J. Social Support, Depression and Anxiety in Cancer Patient-Relative Dyads in Early Survivorship: An Actor-Partner Interdependence Modeling Approach. Psycho-Oncology 2024, 33, e70038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chase, D.M.; Watanabe, T.; Monk, B.J. Assessment and Significance of Quality of Life in Women with Gynecologic Cancer. Futur. Oncol. 2010, 6, 1279–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luckett, T.; King, M.; Butow, P.; Friedlander, M.; Paris, T. Assessing Health-Related Quality of Life in Gynecologic Oncology: A sys-tematic review of questionnaires and their ability to detect clinically important differences and change. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2010, 20, 664–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jónsdóttir, B.; Wikman, A.; Sundström Poromaa, I.; Stålberg, K. Advanced Gynecological Cancer: Quality of Life One Year after Diagnosis. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0287562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Li, L.; Wang, M.; Wei, L.; Li, J.; Zou, W.; Lv, Y.; Zhang, H.; Liu, S. Health-related quality of life in locally advanced cervical cancer patients treated with neoadjuvant therapy followed by radical surgery: A single-institutional retrospective study from a prospective database. Gynecol. Oncol. 2019, 154, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, B.L.; DeRubeis, R.J.; Berman, B.S.; Gruman, J.; Champion, V.L.; Massie, M.J.; Holland, J.C.; Partridge, A.H.; Bak, K.; Somerfield, M.R.; et al. Screening, Assessment, and Care of Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms in Adults With Cancer: An American Society of Clinical Oncology Guideline Adaptation. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 1605–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cillessen, L.; Johannsen, M.; Speckens, A.E.; Zachariae, R. Mindfulness-based interventions for psychological and physical health outcomes in cancer patients and survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psycho-Oncol. 2019, 28, 2257–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Xie, Y.; Zhao, F.-H.; Lu, S.-H.; Huang, H.; Pan, X.-F.; Yang, C.-X.; Qiao, Y.-L. Assessment of quality of life for the patients with cervical cancer at different clinical stages. Chin. J. Cancer 2013, 32, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Khalil, J.; Bellefqih, S.; Sahli, N.; Afif, M.; Elkacemi, H.; Elmajjaoui, S.; Kebdani, T.; Benjaafar, N. Impact of cervical cancer on quality of life: Beyond the short term (Results from a single institution). Gynecol. Oncol. Res. Pract. 2015, 2, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Prasongvej, P.; Nanthakomon, T.; Jaisin, K.; Chanthasenanont, A.; Lertvutivivat, S.; Tanprasertkul, C.; Bhamarapravatana, K.K.; Suwannarurk, K. Quality of Life in Cervical Cancer Survivors and Healthy Women: Thai Urban Population Study. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2017, 18, 385–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.C.; Ching, S.S.; Loke, A.Y. Quality of life measurement in women with cervical cancer: Implications for Chinese cervical cancer survivors. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2010, 8, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Korfage, I.J.; Essink-Bot, M.-L.; Mols, F.; van de Poll-Franse, L.; Kruitwagen, R.; van Ballegooijen, M. Health-Related Quality of Life in Cervical Cancer Survivors: A Population-Based Survey. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2009, 73, 1501–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osann, K.; Hsieh, S.; Nelson, E.L.; Monk, B.J.; Chase, D.; Cella, D.; Wenzel, L. Factors associated with poor quality of life among cervical cancer survivors: Implications for clinical care and clinical trials. Gynecol. Oncol. 2014, 135, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Membrilla-Beltran, L.; Cardona, D.; Camara-Roca, L.; Aparicio-Mota, A.; Roman, P.; Rueda-Ruzafa, L. Impact of Cervical Cancer on Quality of Life and Sexuality in Female Survivors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mvunta, D.H.; August, F.; Dharsee, N.; Mvunta, M.H.; Wangwe, P.; Ngarina, M.; Simba, B.M.; Kidanto, H. Quality of life among cervical cancer patients following completion of chemoradiotherapy at Ocean Road Cancer Institute (ORCI) in Tanzania. BMC Women’s Health 2022, 22, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen, Q.; Zhao, J.; Xue, X.; Xie, X. Effect of marital status on the survival outcomes of cervical cancer: A retrospective cohort study based on SEER database. BMC Women’s Health 2024, 24, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhou, D.; Yang, Y.-J.; Niu, C.-C.; Yu, Y.-J.; Diao, J.-D. Marital status is an independent prognostic factor for cervical adenocarcinoma: A population-based study. Medicine 2023, 102, e33597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (years, mean ± SD) | 48.3 ± 7.4 (range: 32–68) |

| Marital Status | Married: 64 (66.7%) |

| Unmarried: 32 (33.3%) | |

| Stage Classification | Early (IA–IB2): 44 (45.8%) |

| Advanced (IIA–IVA): 52 (54.2%) | |

| Primary Treatment | Surgery: 39 (40.6%) |

| Chemoradiation: 57 (59.4%) | |

| Comorbidities | Diabetes: 16 (16.7%) |

| Hypertension: 24 (25.0%) | |

| Other: 11 (11.5%) | |

| Smoking Status | Current: 18 (18.8%) |

| Former: 29 (30.2%) | |

| Nonsmoker: 49 (51.0%) |

| Domain | Baseline Mean (SD) | Follow-Up Mean (SD) | p-Value | Effect Size (Cohen’s d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Functioning | 61.9 (11.6) | 66.7 (12.3) | 0.015 | 0.41 |

| Role-Physical | 59.2 (13.1) | 62.9 (13.4) | 0.084 | – |

| Bodily Pain | 62.7 (11.8) | 66.2 (12.6) | 0.039 | 0.29 |

| General Health | 57.3 (10.7) | 60.5 (11.3) | 0.046 | 0.29 |

| Vitality | 60.4 (12.7) | 64.6 (13.1) | 0.031 | 0.33 |

| Social Functioning | 66.8 (10.9) | 69.8 (11.5) | 0.068 | – |

| Role-Emotional | 61.5 (12.4) | 64.7 (12.9) | 0.052 | – |

| Mental Health | 63.4 (12.2) | 68.1 (12.4) | 0.022 | 0.38 |

| Measure | Baseline Mean (SD) | Follow-Up Mean (SD) | p-Value | Effect Size (Cohen’s d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

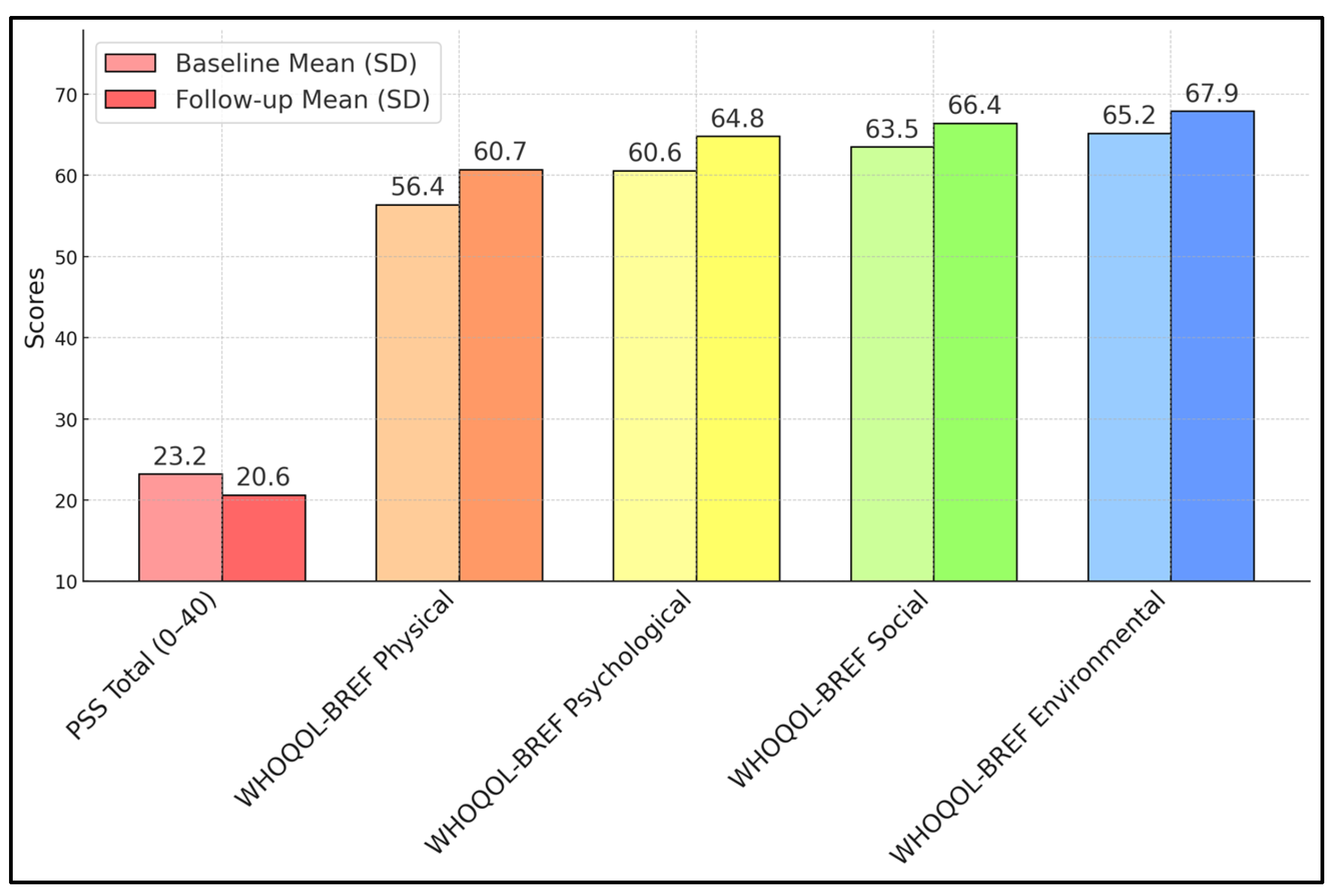

| PSS Total (0–40) | 23.2 (5.7) | 20.6 (5.5) | 0.001 | 0.46 |

| WHOQOL-BREF Physical | 56.4 (12.0) | 60.7 (12.5) | 0.032 | 0.35 |

| WHOQOL-BREF Psychological | 60.6 (13.1) | 64.8 (13.4) | 0.04 | 0.32 |

| WHOQOL-BREF Social | 63.5 (14.5) | 66.4 (15.1) | 0.089 | – |

| WHOQOL-BREF Environmental | 65.2 (13.2) | 67.9 (13.7) | 0.074 | – |

| Scale/Domain | Baseline Mean (SD) | Follow-Up Mean (SD) | p-Value | Effect Size (Cohen’s d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global Health | 61.4 (13.8) | 66.3 (14.2) | 0.014 | 0.36 |

| Physical Functioning | 63.7 (13.5) | 68.4 (13.7) | 0.022 | 0.34 |

| Role Functioning | 58.6 (14.1) | 62.8 (14.8) | 0.051 | – |

| Emotional Functioning | 63.2 (14.2) | 67.1 (14.4) | 0.045 | 0.27 |

| Cognitive Functioning | 65.3 (13.2) | 68.8 (12.9) | 0.058 | – |

| Social Functioning | 60.9 (15.0) | 64.2 (15.8) | 0.092 | – |

| Symptom Scales | ||||

| Fatigue | 53.7 (16.4) | 48.2 (15.9) | 0.02 | 0.34 |

| Pain | 46.8 (15.6) | 42.1 (14.9) | 0.037 | 0.31 |

| Nausea/Vomiting | 22.7 (11.3) | 19.4 (10.7) | 0.042 | 0.3 |

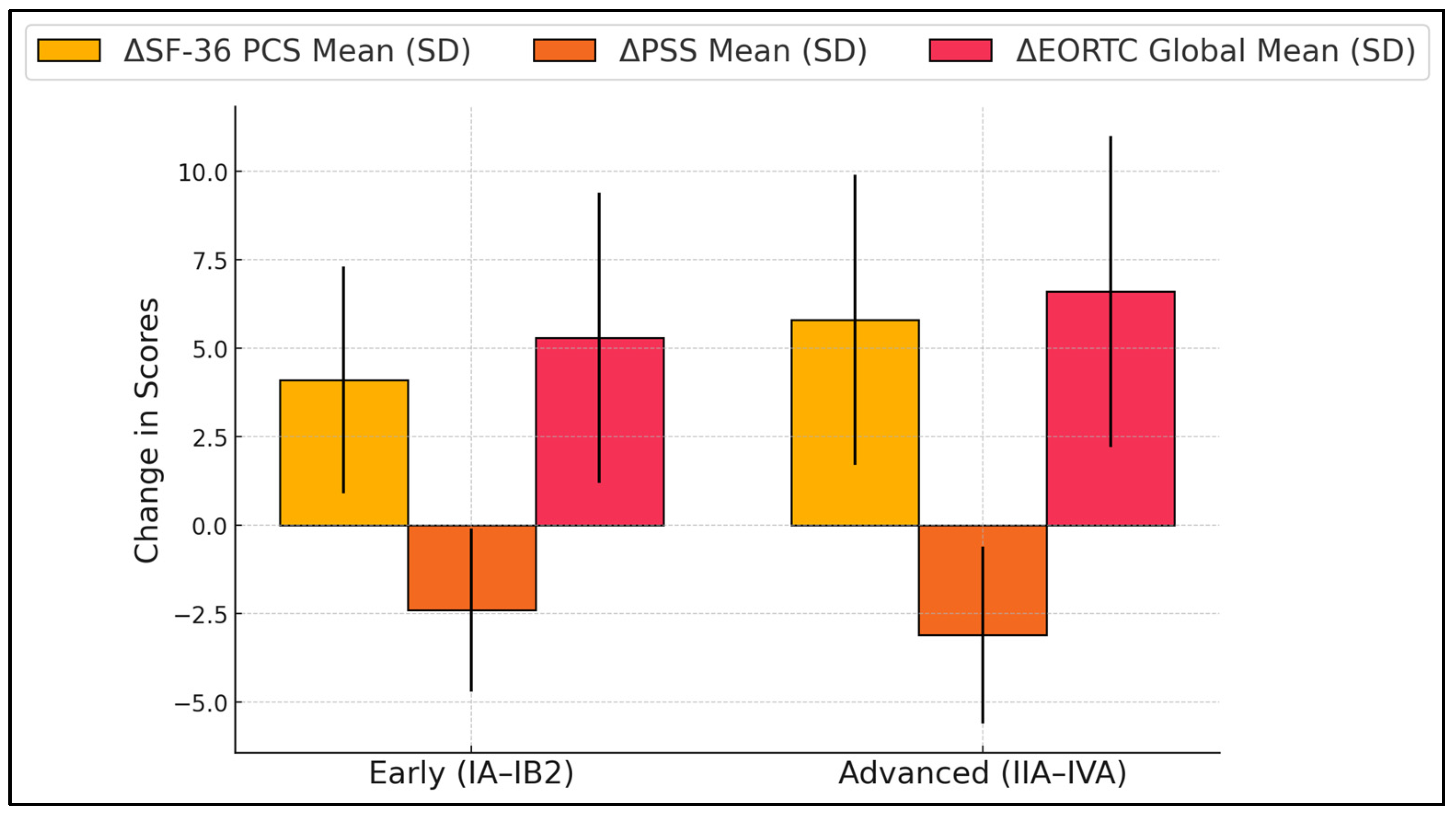

| Stage | n | ΔSF-36 PCS Mean (SD) | ΔPSS Mean (SD) | ΔEORTC Global Mean (SD) | p-Values (PCS/PSS/EORTC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early (IA–IB2) | 44 | +4.1 (3.2) | −2.4 (2.3) | +5.3 (4.1) | 0.042/0.039/0.021 |

| Advanced (IIA–IVA) | 52 | +5.8 (4.1) | −3.1 (2.5) | +6.6 (4.4) | 0.3 |

| Variable | ΔPSS | ΔSF-36 Mental Health | ΔWHOQOL-BREF Psych. | ΔQLQ-C30 Global | Effect Size (Cohen’s d) (PCS/PSS/EORTC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔPSS | 1 | –0.52 ** | –0.55 ** | –0.42 ** | |

| ΔSF-36 Mental Health | –0.52 ** | 1 | 0.48 ** | 0.45 ** | - |

| ΔWHOQOL-BREF Psychological | –0.55 ** | 0.48 ** | 1 | 0.52 ** | |

| ΔQLQ-C30 Global | –0.42 ** | 0.45 ** | 0.52 ** | 1 | 0.41/0.33/0.36 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Betea, R.; Dima, M.; Chiriac, V.D. Quality of Life and Stress-Related Psychological Distress Among Patients with Cervical Cancer: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Diseases 2025, 13, 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13030070

Betea R, Dima M, Chiriac VD. Quality of Life and Stress-Related Psychological Distress Among Patients with Cervical Cancer: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Diseases. 2025; 13(3):70. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13030070

Chicago/Turabian StyleBetea, Razvan, Mirabela Dima, and Veronica Daniela Chiriac. 2025. "Quality of Life and Stress-Related Psychological Distress Among Patients with Cervical Cancer: A Cross-Sectional Analysis" Diseases 13, no. 3: 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13030070

APA StyleBetea, R., Dima, M., & Chiriac, V. D. (2025). Quality of Life and Stress-Related Psychological Distress Among Patients with Cervical Cancer: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Diseases, 13(3), 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13030070