Establishment of a Flow Cytometry Protocol for Binarily Detecting Circulating Tumor Cells with EGFR Mutation

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Antibodies

2.2. Laboratory-Based Evaluation of CTCs

2.2.1. Cell Lines

2.2.2. Immunostaining

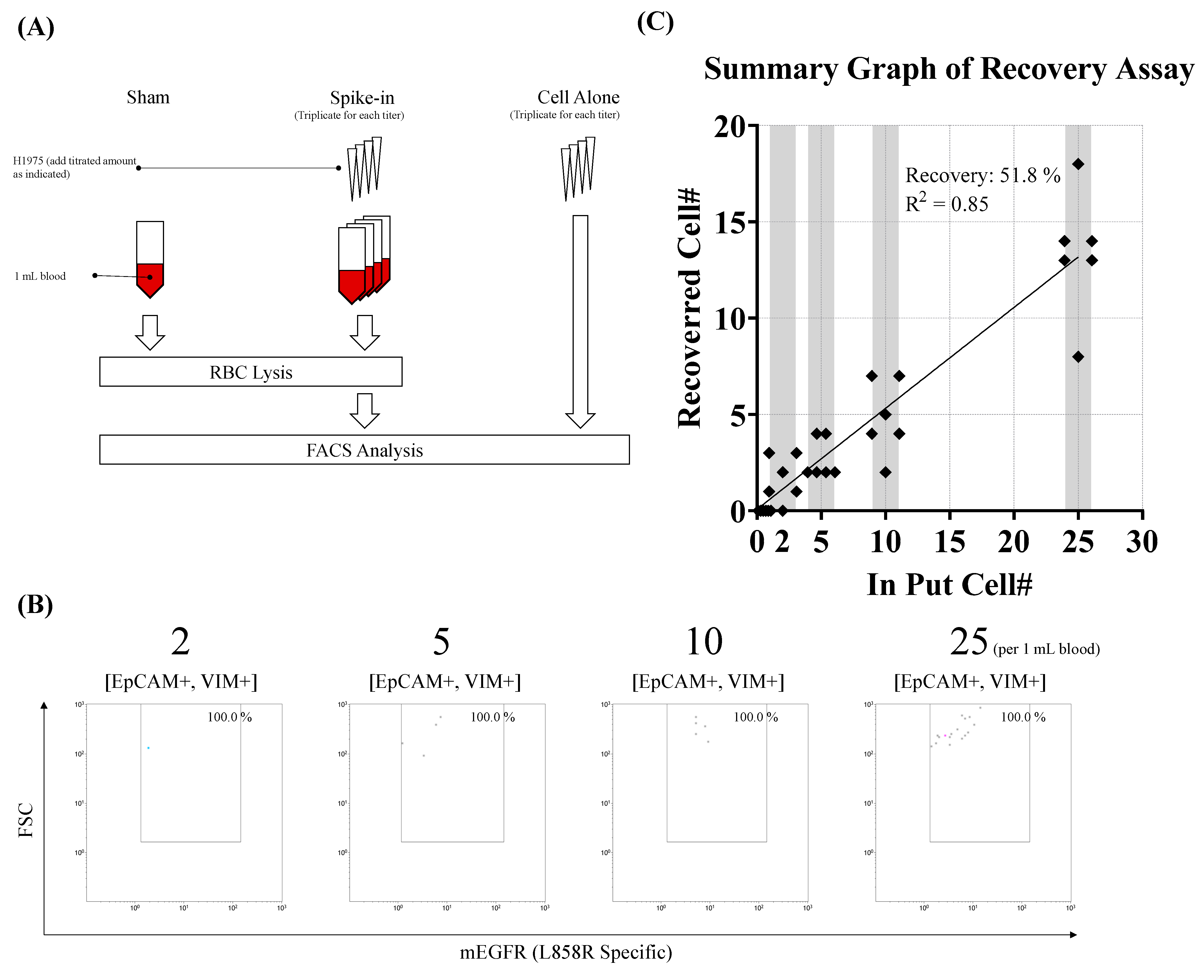

2.2.3. Tumor Cell Spike-In Assay

2.3. Clinical Evaluation of CTCs

Ethical Considerations and Analysis of CTCs

2.4. Data Acquisition and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Establishment of a Pedigree to Identify EGFRL858R-Bearing CTCs in Peripheral Blood Through Flow Cytometry

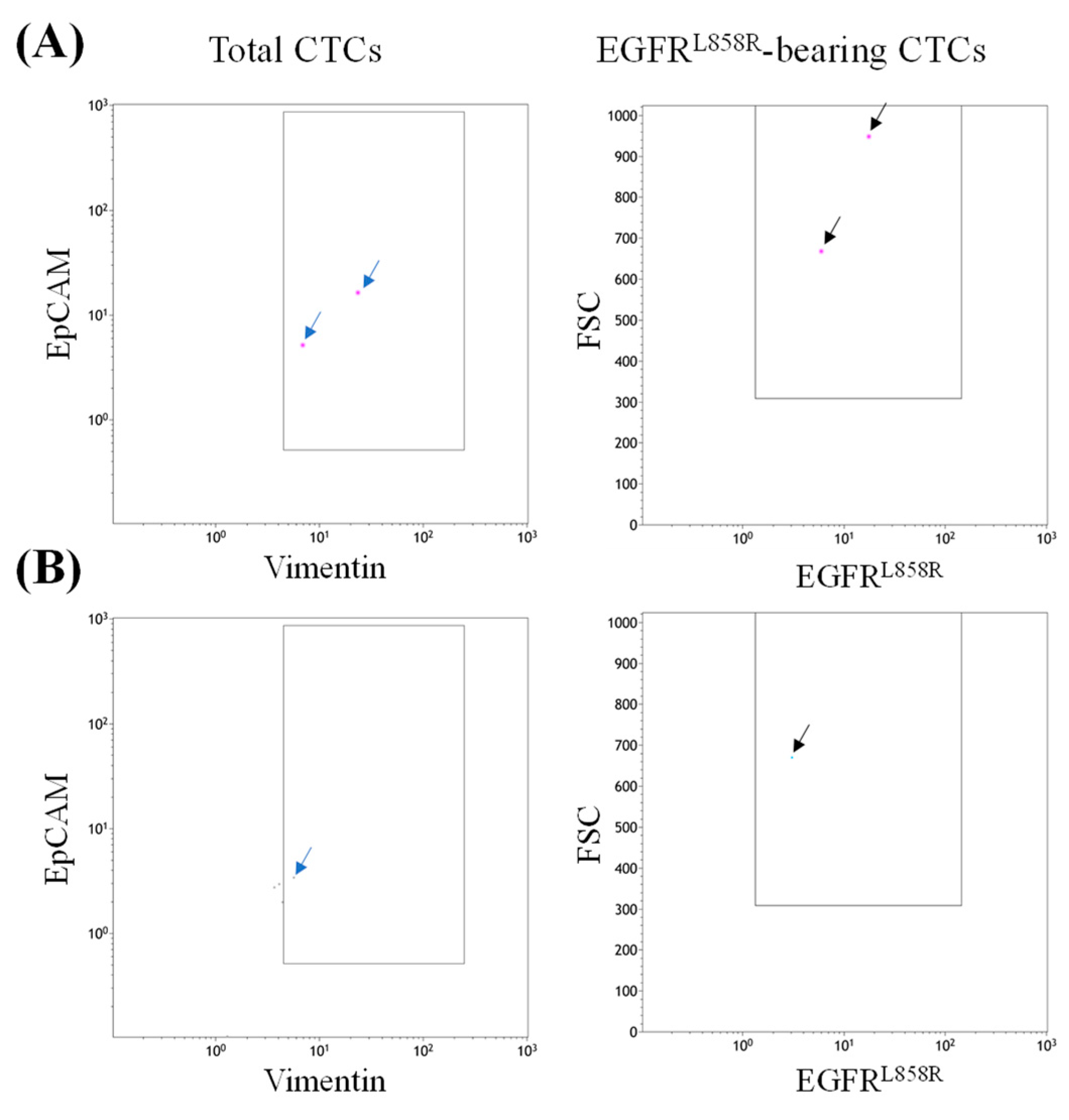

3.2. Detection of EGFRL858R-Bearing CTCs in Blood Samples from Patients with NSCLC

3.3. Case Presentation 1

3.4. Case 2 Presentation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| cfDNA | Cell-free DNA |

| CDx | Companion diagnostics |

| CNP | Cancer-naïve participant |

| CTC | Circulating tumor cell |

| EGFR | Epidermal growth factor receptor |

| NGS | Next-generation sequencing |

| NSCLC | Non-small-cell lung cancer |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| TKI | Tyrosine kinase inhibitor |

References

- Soo, R.A.; Reungwetwattana, T.; Perroud, H.A.; Batra, U.; Kilickap, S.; Tejado Gallegos, L.F.; Donner, N.; Alsayed, M.; Huggenberger, R.; Van Tu, D. Prevalence of EGFR Mutations in Patients With Resected Stages I to III NSCLC: Results From the EARLY-EGFR Study. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2024, 19, 1449–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melosky, B.; Kambartel, K.; Hantschel, M.; Bennetts, M.; Nickens, D.J.; Brinkmann, J.; Kayser, A.; Moran, M.; Cappuzzo, F. Worldwide Prevalence of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Mutations in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Mol. Diagn. Ther. 2022, 26, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Leary, C.; Gasper, H.; Sahin, K.B.; Tang, M.; Kulasinghe, A.; Adams, M.N.; Richard, D.J.; O’Byrne, K.J. Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR)-Mutated Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC). Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goss, G.; Tsai, C.M.; Shepherd, F.A.; Bazhenova, L.; Lee, J.S.; Chang, G.C.; Crino, L.; Satouchi, M.; Chu, Q.; Hida, T.; et al. Osimertinib for pretreated EGFR Thr790Met-positive advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (AURA2): A multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, 1643–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Zhao, K.; Hu, S.; Dong, W.; Gong, Y.; Li, M.; Xie, C. Clinical outcomes of gefitinib and erlotinib in patients with NSCLC harboring uncommon EGFR mutations: A pooled analysis of 438 patients. Lung Cancer 2022, 172, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, L.E.L.; Cortiula, F.; Martins-Branco, D.; Mariamidze, E.; Popat, S.; Reck, M.; Committee, E.G. Updated treatment recommendation for systemic treatment: From the ESMO oncogene-addicted metastatic NSCLC Living Guideline(dagger). Ann. Oncol. 2025, 36, 1227–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, S.; Gonzalez, A.; Cunquero Tomas, A.J.; Calabuig Farinas, S.; Ferrero, M.; Mirda, D.; Sirera, R.; Jantus-Lewintre, E.; Camps, C. A profile on cobas(R) EGFR Mutation Test v2 as companion diagnostic for first-line treatment of patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2020, 20, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciardiello, D.; Boscolo Bielo, L.; Napolitano, S.; Cioli, E.; Latiano, T.P.; De Stefano, A.; Tamburini, E.; Ramundo, M.; Bordonaro, R.; Russo, A.E.; et al. Integrating tissue and liquid biopsy comprehensive genomic profiling to predict efficacy of anti-EGFR therapies in metastatic colorectal cancer: Findings from the CAPRI-2 GOIM study. Eur. J. Cancer 2025, 226, 115642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malapelle, U.; Sirera, R.; Jantus-Lewintre, E.; Reclusa, P.; Calabuig-Farinas, S.; Blasco, A.; Pisapia, P.; Rolfo, C.; Camps, C. Profile of the Roche cobas(R) EGFR mutation test v2 for non-small cell lung cancer. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2017, 17, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, C.; Mao, X.; Wang, Z.; Sun, K.; Ma, R.; Wu, J.; Cao, H. Next-generation sequencing-based detection of EGFR, KRAS, BRAF, NRAS, PIK3CA, Her-2 and TP53 mutations in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 18, 2191–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, H.S.; Chung, J.H.; Kim, L.; Chang, S.; Kim, W.S.; Lee, G.K.; Jung, S.H.; Jang, S.J. Guideline Recommendations for EGFR Mutation Testing in Lung Cancer: Proposal of the Korean Cardiopulmonary Pathology Study Group. Korean J. Pathol. 2013, 47, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudziński, S.; Szpechciński, A.; Moes-Sosnowska, J.; Duk, K.; Zdral, A.; Lechowicz, U.; Rudziński, P.; Kupis, W.; Szczepulska-Wójcik, E.; Langfort, R.; et al. The EGFR mutation detection in NSCLC by Next Generation Sequencing (NGS): Cons and pros. Eur. Respir. J. 2019, 54, PA4059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quandt, D.; Dieter Zucht, H.; Amann, A.; Wulf-Goldenberg, A.; Borrebaeck, C.; Cannarile, M.; Lambrechts, D.; Oberacher, H.; Garrett, J.; Nayak, T.; et al. Implementing liquid biopsies into clinical decision making for cancer immunotherapy. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 48507–48520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, C.I.; Chiang, C.L.; Shiao, T.H.; Luo, Y.H.; Chao, H.S.; Huang, H.C.; Chiu, C.H. Real-world evidence of the intrinsic limitations of PCR-based EGFR mutation assay in non-small cell lung cancer. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 13566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnero-Gregorio, M.; Perera-Gordo, E.; de-la-Pena-Castro, V.; Gonzalez-Martin, J.M.; Delgado-Sanchez, J.J.; Rodriguez-Cerdeira, C. High Incidence of False Positives in EGFR S768I Mutation Detection Using the Idylla qPCR System in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagakubo, Y.; Hirotsu, Y.; Yoshino, M.; Amemiya, K.; Saito, R.; Kakizaki, Y.; Tsutsui, T.; Miyashita, Y.; Goto, T.; Omata, M. Comparison of diagnostic performance between Oncomine Dx target test and AmoyDx panel for detecting actionable mutations in lung cancer. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 12480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.C.; Yeh, Y.C.; Chen, Y.L.; Chiu, C.H. Economic Analysis of Exclusionary EGFR Test Versus Up-Front NGS for Lung Adenocarcinoma in High EGFR Mutation Prevalence Areas. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2022, 20, 774–782.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, Y. Clinical utility of liquid biopsy-based companion diagnostics in the non-small-cell lung cancer treatment. Explor. Target. Antitumor Ther. 2022, 3, 630–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Shen, L.; Luo, M.; Zhang, K.; Li, J.; Yang, Q.; Zhu, F.; Zhou, D.; Zheng, S.; Chen, Y.; et al. Circulating tumor cells: Biology and clinical significance. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieckmann, L.M.; Spohn, M.; Ruff, L.; Agorku, D.; Becker, L.; Borchers, A.; Krause, J.; O’Reilly, R.; Hille, J.; Velthaus-Rusik, J.L.; et al. Diagnostic leukapheresis reveals distinct phenotypes of NSCLC circulating tumor cells. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habli, Z.; AlChamaa, W.; Saab, R.; Kadara, H.; Khraiche, M.L. Circulating Tumor Cell Detection Technologies and Clinical Utility: Challenges and Opportunities. Cancers 2020, 12, 1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sassi, A.; You, L. Microfluidics-Based Technologies for the Assessment of Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Cells 2024, 13, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Zapata, C.; Leman, J.K.H.; Priller, J.; Bottcher, C. The use and limitations of single-cell mass cytometry for studying human microglia function. Brain Pathol. 2020, 30, 1178–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopresti, A.; Malergue, F.; Bertucci, F.; Liberatoscioli, M.L.; Garnier, S.; DaCosta, Q.; Finetti, P.; Gilabert, M.; Raoul, J.L.; Birnbaum, D.; et al. Sensitive and easy screening for circulating tumor cells by flow cytometry. JCI Insight 2019, 4, e128180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, L.J.; Tsai, C.C.; Li, P.Y.; Lee, C.Y.; Lin, S.R.; Lai, W.Y.; Chen, I.Y.; Chang, C.F.; Lee, J.M.; Chiu, Y.L. Characterization of unique pattern of immune cell profile in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma through flow cytometry and machine learning. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2024, 28, e18404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, A.; Piairo, P.; Matos, B.; Santos, D.A.R.; Palmeira, C.; Santos, L.L.; Lima, L.; Dieguez, L. Minimizing false positives for CTC identification. Anal. Chim. Acta 2024, 1288, 342165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.X.; Wang, J.; Song, B.; Wei, H.; Lv, W.P.; Tian, L.M.; Li, M.; Lv, S. Establishment and biological characteristics of acquired gefitinib resistance in cell line NCI-H1975/gefinitib-resistant with epidermal growth factor receptor T790M mutation. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 11, 2767–2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zuo, Y.; Gao, S.; Liu, Y.; Liu, T.; He, S.; Wang, M.; Hu, L.; Li, C.; Yu, Y. Circulating Tumor Cell Phenotype Detection and Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition Tracking Based on Dual Biomarker Co-Recognition in an Integrated PDMS Chip. Small 2024, 20, e2310360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moerkens, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wester, L.; van de Water, B.; Meerman, J.H. Epidermal growth factor receptor signalling in human breast cancer cells operates parallel to estrogen receptor alpha signalling and results in tamoxifen insensitive proliferation. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanssen, A.; Loges, S.; Pantel, K.; Wikman, H. Detection of Circulating Tumor Cells in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2015, 5, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanssen, A.; Wagner, J.; Gorges, T.M.; Taenzer, A.; Uzunoglu, F.G.; Driemel, C.; Stoecklein, N.H.; Knoefel, W.T.; Angenendt, S.; Hauch, S.; et al. Characterization of different CTC subpopulations in non-small cell lung cancer. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, X.R.; Zhu, L.Y.; Qian, K.; Feng, Y.G.; Zhou, J.H.; Wang, R.W.; Bai, L.; Deng, B.; Liang, N.; Tan, Q.Y. Circulating tumor cells in early stage lung adenocarcinoma: A case series report and literature review. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 23130–23141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.H.; Menis, J.; Kim, T.M.; Kim, H.R.; Zhou, C.; Kurniawati, S.A.; Prabhash, K.; Hayashi, H.; Lee, D.D.; Imasa, M.S.; et al. Pan-Asian adapted ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of patients with oncogene-addicted metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. ESMO Open 2024, 9, 103996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, J.; Wang, W.; Zhang, W. A meta-analysis of liquid biopsy versus tumor histology for detecting EGFR mutations in non-small cell lung cancer. Transl. Oncol. 2024, 47, 102022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magbanua, M.J.; Sosa, E.V.; Roy, R.; Eisenbud, L.E.; Scott, J.H.; Olshen, A.; Pinkel, D.; Rugo, H.S.; Park, J.W. Genomic profiling of isolated circulating tumor cells from metastatic breast cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheswaran, S.; Sequist, L.V.; Nagrath, S.; Ulkus, L.; Brannigan, B.; Collura, C.V.; Inserra, E.; Diederichs, S.; Iafrate, A.J.; Bell, D.W.; et al. Detection of mutations in EGFR in circulating lung-cancer cells. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 359, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosti, I.; Jain, N.; Aran, D.; Butte, A.J.; Sirota, M. Cross-tissue Analysis of Gene and Protein Expression in Normal and Cancer Tissues. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Liu, C.; Qi, M.; Cheng, L.; Wang, L.; Li, C.; Dong, B. Recent progress of nanostructure-based enrichment of circulating tumor cells and downstream analysis. Lab. Chip 2023, 23, 1493–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenta, R.; Richert, J.; Muchlinska, A.; Senkus, E.; Suchodolska, G.; Lapinska-Szumczyk, S.; Domzalski, P.; Miszewski, K.; Matuszewski, M.; Dziadziuszko, R.; et al. Measurable morphological features of single circulating tumor cells in selected solid tumors-A pilot study. Cytometry A 2024, 105, 883–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riely, G.J.; Wood, D.E.; Ettinger, D.S.; Aisner, D.L.; Akerley, W.; Bauman, J.R.; Bharat, A.; Bruno, D.S.; Chang, J.Y.; Chirieac, L.R.; et al. Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Version 4.2024, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw. 2024, 22, 249–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Yang, M.; Liang, N.; Li, S. Determining EGFR-TKI sensitivity of G719X and other uncommon EGFR mutations in non-small cell lung cancer: Perplexity and solution (Review). Oncol. Rep. 2017, 37, 1347–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contreras-Sanz, A.; Negri, G.L.; Reike, M.J.; Oo, H.Z.; Scurll, J.M.; Spencer, S.E.; Nielsen, K.; Ikeda, K.; Wang, G.; Jackson, C.L.; et al. Proteomic profiling identifies muscle-invasive bladder cancers with distinct biology and responses to platinum-based chemotherapy. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Y.; Liu, X.; Zheng, L.; Wang, S.; Zhang, J.; Xiong, S.; Zhang, P.; Jiao, Z.; Zhao, G.; Zhou, C.; et al. Comprehensive profiling of EGFR mutation subtypes reveals genomic-clinical associations in non-small-cell lung cancer patients on first-generation EGFR inhibitors. Neoplasia 2023, 38, 100888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treue, D.; Bockmayr, M.; Stenzinger, A.; Heim, D.; Hester, S.; Klauschen, F. Proteogenomic systems analysis identifies targeted therapy resistance mechanisms in EGFR-mutated lung cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 144, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitthirak, S.; Roytrakul, S.; Wangwiwatsin, A.; Namwat, N.; Klanrit, P.; Dokduang, H.; Sa-Ngiamwibool, P.; Titapan, A.; Jareanrat, A.; Thanasukarn, V.; et al. Proteomic profiling reveals common and region-specific protein signatures underlying tumor heterogeneity in cholangiocarcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQuerry, J.A.; Chang, J.T.; Bowtell, D.D.L.; Cohen, A.; Bild, A.H. Mechanisms and clinical implications of tumor heterogeneity and convergence on recurrent phenotypes. J. Mol. Med. 2017, 95, 1167–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Chen, H. Tumor heterogeneity and resistance to EGFR-targeted therapy in advanced nonsmall cell lung cancer: Challenges and perspectives. Onco Targets Ther. 2014, 7, 1689–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passaro, A.; Malapelle, U.; Del Re, M.; Attili, I.; Russo, A.; Guerini-Rocco, E.; Fumagalli, C.; Pisapia, P.; Pepe, F.; De Luca, C.; et al. Understanding EGFR heterogeneity in lung cancer. ESMO Open 2020, 5, e000919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaed, B.; Lin, L.; Son, J.; Li, J.; Smolander, J.; Lopez, T.; Eser, P.O.; Ogino, A.; Ambrogio, C.; Eum, Y.; et al. Intratumor heterogeneity of EGFR expression mediates targeted therapy resistance and formation of drug tolerant microenvironment. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, S.K.; Galgadas, I.; Clarke, D.T.; Zanetti-Domingues, L.C.; Gervasio, F.L.; Martin-Fernandez, M.L. Targeting mutant EGFR in non-small cell lung cancer in the context of cell adaptation and resistance. Drug Discov. Today 2025, 30, 104407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name | Manufacture |

|---|---|

| For cell culture | |

| EMEM | Thermo-Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA |

| Fetal bovine serum | Thermo-Fisher |

| Ham’s F-12K (Kaighn’s) Medium | Thermo-Fisher |

| Penicillin/Streptomycin | Thermo-Fisher |

| RPMI1640 | Thermo-Fisher |

| TrypLE select | Thermo-Fisher |

| For Immunostaining | |

| Cell staining buffer | BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA |

| Foxp3 Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set | eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA |

| For Spike-in assay | |

| RBC lysis buffer | Biolegend |

| Target | Clone | Host | Fluorophore | Manufacture | Catalogue No. | Dilution Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface markers | ||||||

| CD45 | J33 | Mouse | ECD | Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA | A07784 | 1:10 |

| EGFRL858R | 43B2 | Rabbit | PE | Cell signaling Technology, Denvers, MA, USA | 64716S | 1:12.5 |

| CD326 (EpCAM) | 9C4 | Mouse | BV510 | BioLegend | 324236 | 1:10 |

| Intracellular markers | ||||||

| Cytokeratin 7/8 | CAM5.2 | Mouse | FITC | BD Pharmingen, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA | 347653 | 1:20 |

| Cytokeratin 14/15/16/19 | KA4 | Mouse | AF647 | BD Pharmingen | 563648 | 1:80 |

| Vimentin | EPR3776 | Rabbit | AF405 | Abcam, Cambridge, UK | ab210152 | 1:125 |

| Isotype control | ||||||

| Rabbit mAb IgG XP® Isotype Control | DA1E | Rabbit | PE | Cell Signaling Technology | 5742S | 1:50 |

| NSCLC N = 21 | HC N = 10 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male, N (%) | 8 (38%) | 6 (60%) | |

| Median age, year | 66 (46–86) | 61.5 (50–74) | 0.06 |

| Stage, N (%) | |||

| IIIb | 1 (5%) | ||

| IV | 20 (95%) | ||

| EGFR mutation, N (%) | |||

| Wildtype | 8 (38%) | ||

| L858R | 7 (33%) | ||

| Other Mutation | 6 (29%) |

| Agreement Type | Subject Number (N) | Agreement Percentage (%) | Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall agreement (CTC+/PCR+ & CTC−/PCR−) | 17 | 81 | 0.6000–0.9233 |

| Positive agreement (CTC+/PCR+) | 7 | 100 | 0.6457–1.0000 |

| Negative agreement (CTC−/PCR−) | 10 | 71 | 0.4535–1.0000 |

| Disagreement (CTC+/PCR− & CTC−/PCR+) | 4 | 19 | |

| Total | 21 | 100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chang, C.-Y.; Tu, C.-C.; Lin, S.-R.; Fang, C.-H.; Tseng, P.-W.; Liao, W.-E.; Huang, L.-Y.; Wang, S.-L.; Lai, W.-Y.; Chao, Y.; et al. Establishment of a Flow Cytometry Protocol for Binarily Detecting Circulating Tumor Cells with EGFR Mutation. Diseases 2025, 13, 406. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13120406

Chang C-Y, Tu C-C, Lin S-R, Fang C-H, Tseng P-W, Liao W-E, Huang L-Y, Wang S-L, Lai W-Y, Chao Y, et al. Establishment of a Flow Cytometry Protocol for Binarily Detecting Circulating Tumor Cells with EGFR Mutation. Diseases. 2025; 13(12):406. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13120406

Chicago/Turabian StyleChang, Cheng-Yu, Chia-Chun Tu, Shian-Ren Lin, Chih-Hao Fang, Po-Wei Tseng, Wan-En Liao, Li-Yun Huang, Shiu-Lan Wang, Wan-Yu Lai, Yee Chao, and et al. 2025. "Establishment of a Flow Cytometry Protocol for Binarily Detecting Circulating Tumor Cells with EGFR Mutation" Diseases 13, no. 12: 406. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13120406

APA StyleChang, C.-Y., Tu, C.-C., Lin, S.-R., Fang, C.-H., Tseng, P.-W., Liao, W.-E., Huang, L.-Y., Wang, S.-L., Lai, W.-Y., Chao, Y., Chiu, Y.-L., & Lee, J.-M. (2025). Establishment of a Flow Cytometry Protocol for Binarily Detecting Circulating Tumor Cells with EGFR Mutation. Diseases, 13(12), 406. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13120406