The Application of Stepwise Pelvic Devascularisation in the Management of Severe Placenta Accreta Spectrum as Part of the Soleymani and Collins Technique for Caesarean Hysterectomy: Surgical Description and Evaluation of Short- and Long-Term Outcomes

Abstract

1. Introduction

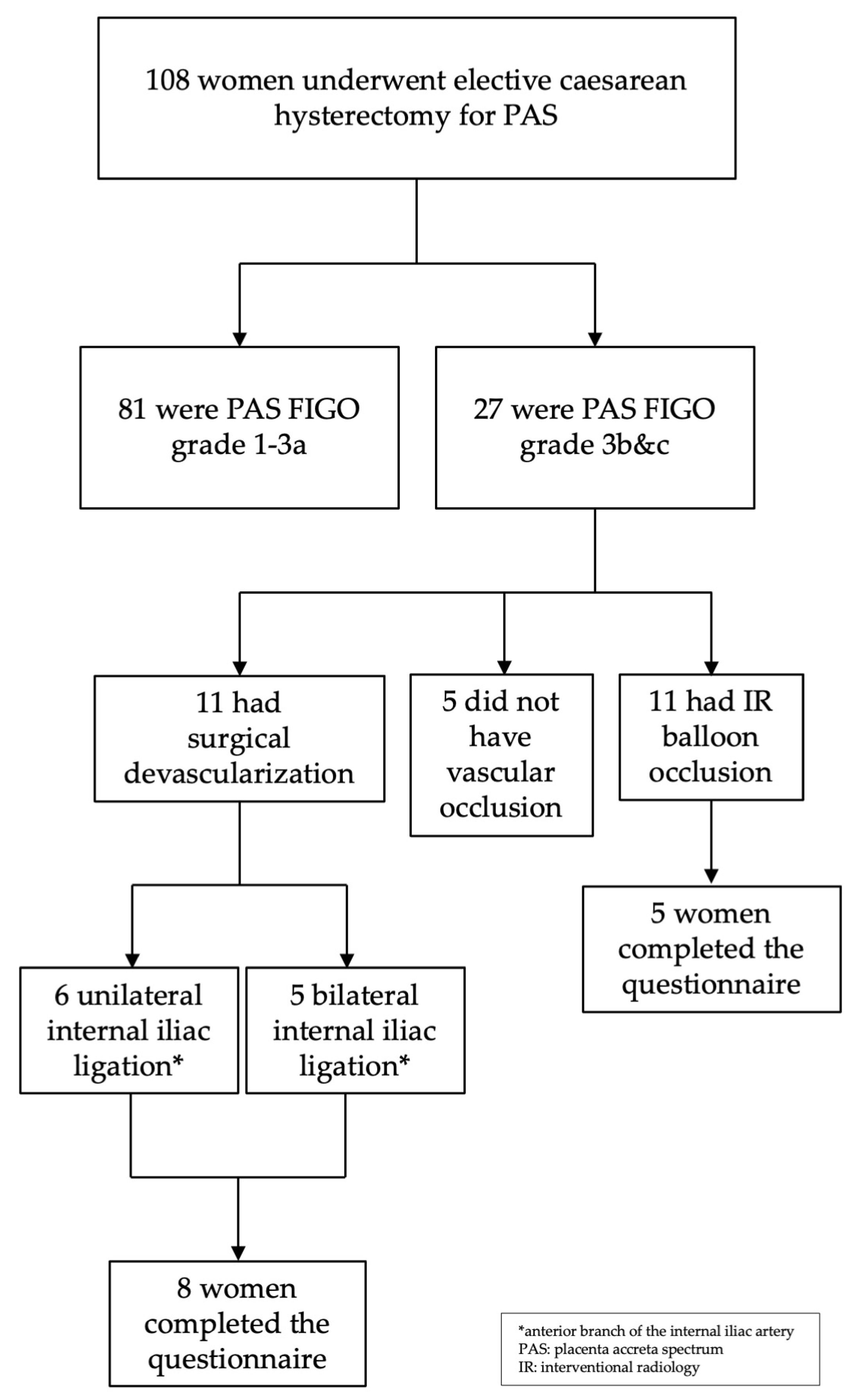

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Method for Reducing Pelvic Blood Flow

2.1.1. Surgical Devascularisation

2.1.2. IR Balloon Occlusion

2.2. Study of Short- and Long-Term Complications

3. Results

3.1. Short-Term Complications

3.2. Long-Term Complications

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PAS | Placenta Accreta Spectrum |

| SAC | Soleymani and Collins |

| IR | Interventional Radiology |

| CIA | Common Iliac Artery |

| IIA | Internal Iliac Artery |

References

- Einerson, B.D.; Gilner, J.B.; Zuckerwise, L.C. Placenta Accreta Spectrum. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 142, 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sentilhes, L.; Kayem, G.; Chandraharan, E.; Palacios-Jaraquemada, J.; Jauniaux, E.; The FIGO Placenta Accreta Diagnosis and Management Expert Consensus Panel. FIGO consensus guidelines on placenta accreta spectrum disorders: Conservative management. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2018, 140, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieto-Calvache, A.J.; Palacios-Jaraquemada, J.M.; Osanan, G.; Cortes-Charry, R.; Aryananda, R.A.; Bangal, V.B.; Slaoui, A.; Abbas, A.M.; Akaba, G.O.; Joshua, Z.N.; et al. Lack of experience is a main cause of maternal death in placenta accreta spectrum patients. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2021, 100, 1445–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamshirsaz, A.A.; Fox, K.A.; Salmanian, B.; Diaz-Arrastia, C.R.; Lee, W.; Baker, B.W.; Ballas, J.; Chen, Q.; Van Veen, T.R.; Javadian, P.; et al. Maternal morbidity in patients with morbidly adherent placenta treated with and without a standardized multidisciplinary approach. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 212, 218.e1–218.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrov, D.A.; Karlberg, B.; Singh, K.; Hartman, M.; Mittal, P.K. Perioperative Internal Iliac Artery Balloon Occlusion, in the Setting of Placenta Accreta and Its Variants: The Role of the Interventional Radiologist. Curr. Probl. Diagn. Radiol. 2018, 47, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, T.K.; Stewart, J.K. Placenta Accreta Spectrum: The Role of Interventional Radiology in Multidisciplinary Management. Semin. Interv. Radiol. 2023, 40, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salim, R.; Chulski, A.; Romano, S.; Garmi, G.; Rudin, M.; Shalev, E. Precesarean prophylactic balloon catheters for suspected placenta accreta: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 126, 1022–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enste, R.; Cricchio, P.; Dewandre, P.-Y.; Braun, T.; Leonards, C.O.; Niggemann, P.; Spies, C.; Henrich, W.; Kaufner, L. Placenta Accreta Spectrum Part I: Anesthesia considerations based on an extended review of the literature. J. Perinat. Med. 2022, 51, 439–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, S.; Zhi, Y.; Cheng, G.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, L.; Shen, L. Retrospective analysis of placenta previa with abnormal placentation with and without prophylactic use of abdominal aorta balloon occlusion. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2017, 137, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soyer, P.; Barat, M.; Loffroy, R.; Barral, M.; Dautry, R.; Vidal, V.; Pellerin, O.; Cornelis, F.; Kohi, M.P.; Dohan, A. The role of interventional radiology in the management of abnormally invasive placenta: A systematic review of current evidences. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2020, 10, 1370–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamil, H.; Tariq, W.; Ameer, M.A.; Asghar, M.S.; Mahmood, H.; Tahir, M.J.; Yousaf, Z. Interventional radiology in low- and middle-income countries. Ann. Med. Surg. 2022, 77, 103594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teare, J.; Evans, E.; Belli, A.; Wendler, R. Sciatic nerve ischaemia after iliac artery occlusion balloon catheter placement for placenta percreta. Int. J. Obstet. Anesth. 2014, 23, 178–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, S.; Maturana, R.; Spitzer, Y.; Bernstein, J. Thrombosis and compartment syndrome requiring fasciotomy: Complications of internal iliac artery balloon catheters for morbidly adherent placenta. J. Clin. Anesth. 2018, 49, 67–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabhan, A.E.; AbdelQadir, Y.H.; Abdelghafar, Y.A.; Kashbour, M.O.; Salem, N.; Abdelkhalek, A.N.; Nourelden, A.Z.; Eshag, M.M.E.; Shah, J. Therapeutic effect of Internal iliac artery ligation and uterine artery ligation techniques for bleeding control in placenta accreta spectrum patients: A meta-analysis of 795 patients. Front. Surg. 2022, 9, 983297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tozzi, R.; Hardern, K.; Gubbala, K.; Campanile, R.G.; Majd, H.S. En-bloc resection of the pelvis (EnBRP) in patients with stage IIIC–IV ovarian cancer: A 10 steps standardised technique. Surgical and survival outcomes of primary vs. interval surgery. Gynecol. Oncol. 2017, 144, 564–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majd, H.S.; Collins, S.L.; Addley, S.; Weeks, E.; Chakravarti, S.; Halder, S.; Alazzam, M. The modified radical peripartum cesarean hysterectomy (Soleymani-Alazzam-Collins technique): A systematic, safe procedure for the management of severe placenta accreta spectrum. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 225, 175.e1–175.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schellenberg, M.; Gallegos, H.; Owattanapanich, N.; Wong, M.D.; Bardes, J.M.; Joos, E.; Vogt, K.N.; Inaba, K. Complications Following Temporary Bilateral Internal Iliac Artery Ligation for Pelvic Hemorrhage Control in Trauma. Am. Surg. 2022, 88, 2475–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Step | Description of the SAC Surgical Devascularisation Technique |

|---|---|

| 1 | Fundal caesarean delivery with placenta left in situ and hysterotomy closed |

| 2 | Access to the abdominal aorta below the inferior mesenteric artery, with exposure of the aorto-caval region |

| 3 | Exposure and identification of the right common iliac artery and bifurcation, IVC, and right ureter |

| 4 | Identification of the aorta-caval space, followed by slinging the right common iliac artery |

| 5 | Suture double-tied but left loose enough not to occlude blood flow, placed at the correct position on the right internal iliac artery (ligation can then instantly be performed by tightening the knots) |

| 6 | Ligation of the right uterine artery at its origin |

| 7 | Exposure and identification of the left common iliac artery, left common iliac vein and left ureter |

| 8 | Identification and slinging of the left common iliac artery |

| 9 | Suture double-tied but left loose enough not to occlude blood flow, placed at the correct position on the left internal iliac artery (ligation can then instantly be performed by tightening the knots) |

| 10 | Ligation of the left uterine artery from the origin |

| Patient Demographics | Surgical Devascularisation (n = 11) | IR (n = 11) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at the time of surgery | 33 (5.7) | 35 (3.1) | 0.24 * |

| Body mass index at the time of surgery | 26.1 (5.6) | 25.8 (8.5) | 0.28 * |

| Gestation at delivery (completed weeks) | 35.5 (1.7) | 35 (0.8) | 1 * |

| Devascularisation Technique | |||

| Internal iliac artery ligation (unilateral) | 6 (55%) | 0 | |

| Internal iliac artery ligation (bilateral) | 5 (45%) | 0 | |

| Pelvic arterial balloon placement (IR) | 0 | 11 | |

| Maternal Morbidity | |||

| Median estimated blood loss (with interquartile range) | 1600 (1135) mL | 2500 (2050) mL | 0.04 * (rb = 0.45) |

| Received blood products | 2 (18%) | 7 (63.6%) | 0.08 † |

| Significant transfusion (>5 units red cells) | 0 | 3 | 0.21 † |

| Massive transfusion (>10 units red cells) | 0 | 1 | 0.59 † |

| Intensive care unit admission with adult respiratory distress syndrome | 0 | 1 | 0.59 † |

| Surgical Devascularisation | IR | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients contacted | 11 | 11 | - |

| Number of patients responded | 8 | 9 | - |

| Number of patients who declined to participate | 0 | 4 | - |

| Number of study participants | 8 (73%) | 5 (45%) | - |

| n = 8 | n = 5 | ||

| Time since surgery in years | 2.5 (4) | 11 (2.5) | 0.02 * |

| Ischaemic leg pain | 0 | 0 | - |

| Transient tingling/numbness in leg | 1 (12.5%) | 1 (20%) | 0.64 |

| Buttock claudication | 0 | 0 | - |

| Other leg symptoms (see text) | 2 (25%) | 0 | 0.36 |

| Inability to open bowels/pass wind | 0 | 0 | - |

| Bladder symptoms requiring urodynamic testing | 0 | 1 | 0.38 |

| Satisfaction with the results of the surgery | 7 (88%) | 4 (80%) | 1.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Soleymani majd, H.; Ismail, L.; Supramaniam, P.; Aggarwal, A.; Collins, A.E.; Lim, L.; Addley, S.; Hunter, A.; Pert, L.; Adu-Bredu, T.; et al. The Application of Stepwise Pelvic Devascularisation in the Management of Severe Placenta Accreta Spectrum as Part of the Soleymani and Collins Technique for Caesarean Hysterectomy: Surgical Description and Evaluation of Short- and Long-Term Outcomes. Diseases 2025, 13, 400. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13120400

Soleymani majd H, Ismail L, Supramaniam P, Aggarwal A, Collins AE, Lim L, Addley S, Hunter A, Pert L, Adu-Bredu T, et al. The Application of Stepwise Pelvic Devascularisation in the Management of Severe Placenta Accreta Spectrum as Part of the Soleymani and Collins Technique for Caesarean Hysterectomy: Surgical Description and Evaluation of Short- and Long-Term Outcomes. Diseases. 2025; 13(12):400. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13120400

Chicago/Turabian StyleSoleymani majd, Hooman, Lamiese Ismail, Prasanna Supramaniam, Aakriti Aggarwal, Annie E. Collins, Lee Lim, Susan Addley, Alicia Hunter, Lexie Pert, Theophilus Adu-Bredu, and et al. 2025. "The Application of Stepwise Pelvic Devascularisation in the Management of Severe Placenta Accreta Spectrum as Part of the Soleymani and Collins Technique for Caesarean Hysterectomy: Surgical Description and Evaluation of Short- and Long-Term Outcomes" Diseases 13, no. 12: 400. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13120400

APA StyleSoleymani majd, H., Ismail, L., Supramaniam, P., Aggarwal, A., Collins, A. E., Lim, L., Addley, S., Hunter, A., Pert, L., Adu-Bredu, T., Pinto, P., Al Naimi, A., Conforti, J., Fox, K., & Collins, S. L. (2025). The Application of Stepwise Pelvic Devascularisation in the Management of Severe Placenta Accreta Spectrum as Part of the Soleymani and Collins Technique for Caesarean Hysterectomy: Surgical Description and Evaluation of Short- and Long-Term Outcomes. Diseases, 13(12), 400. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13120400