Effects of Short-Term (20-Day) Alternate-Day Modified Fasting and Time-Restricted Feeding on Fasting Glucose and IGF-1 in Obese Young Women

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Subject Characteristics

2.3. Intermittent Fasting Protocol

2.4. Outcomes Measurement

2.4.1. Body Composition Assessment

2.4.2. Blood Sampling and Biochemical Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Subject Baseline Characteristics

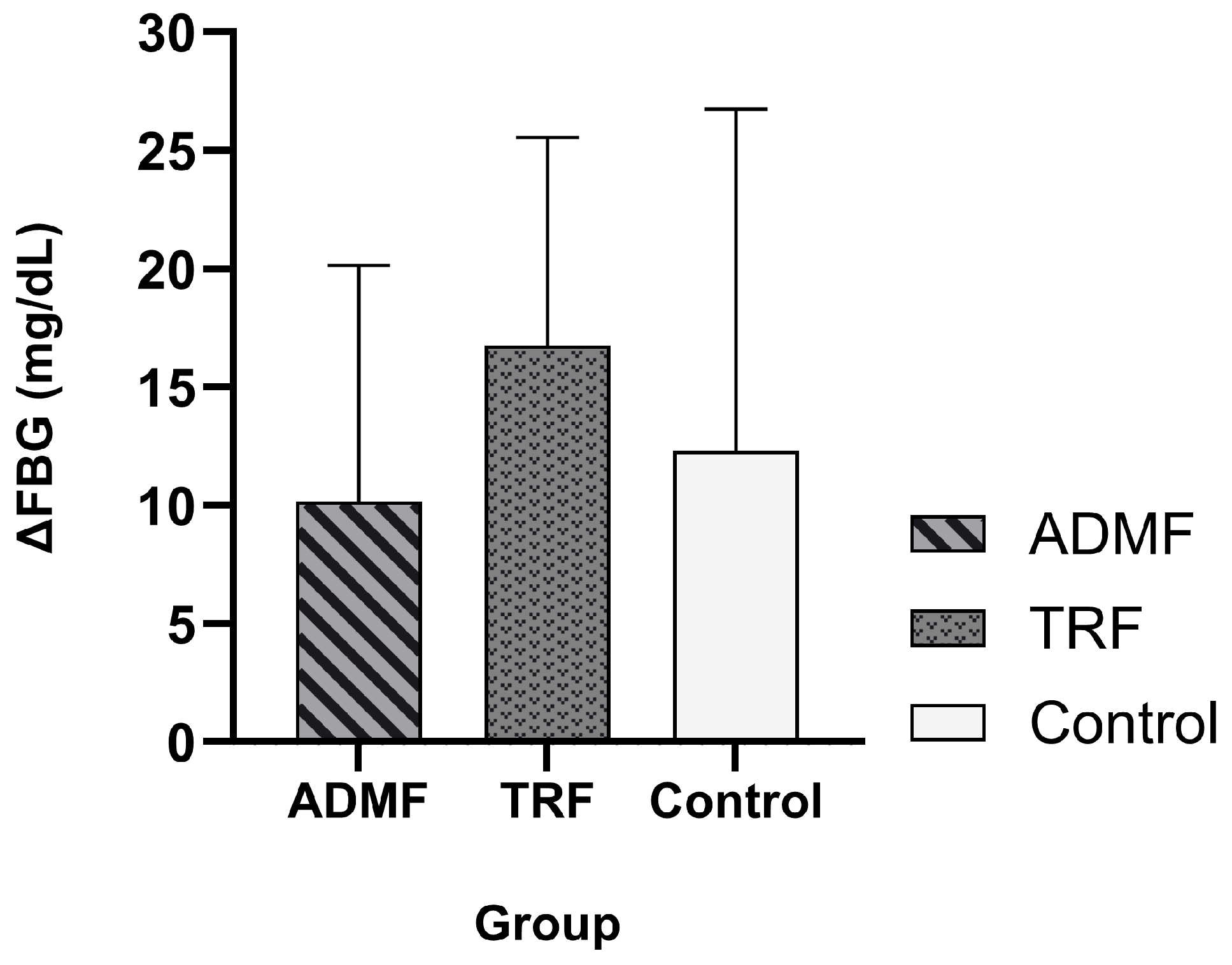

3.2. The Effect of Intermittent Fasting on Fasting Blood Glucose

3.3. The Intermittent Fasting Effect on IGF-1 Serum

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Oragnization, Regional Office for the Western Pacific. The Asia Pacific Perspective: Redefining Obesity and Its Treatment; WHO: Manila, Philippines, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, M.; Gakidou, E.; Lo, J.; Abate, Y.H.; Abbafati, C.; Abbas, N.; Abbasian, M.; Abd ElHafeez, S.; Abdel-Rahman, W.M.; Abd-Elsalam, S.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Prevalence of Adult Overweight and Obesity, 1990–2021, with Forecasts to 2050: A Forecasting Study for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2025, 405, 813–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Oragnization. Obesity and Overweight; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekaran, P.; Weiskirchen, R. The Role of Obesity in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus—An Overview. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabák, A.G.; Herder, C.; Rathmann, W.; Brunner, E.J.; Kivimäki, M. Prediabetes: A High-Risk State for Diabetes Development. Lancet 2012, 379, 2279–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, K.C.J.; Hjortebjerg, R.; Ganeshalingam, A.A.; Clemmons, D.R.; Frystyk, J. Growth Hormone/Insulin-like Growth Factor I Axis in Health and Disease States: An Update on the Role of Intra-Portal Insulin. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1456195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooney, M.R.; Fang, M.; Ogurtsova, K.; Ozkan, B.; Echouffo-Tcheugui, J.B.; Boyko, E.J.; Magliano, D.J.; Selvin, E. Global Prevalence of Prediabetes. Diabetes Care 2023, 46, 1388–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Ballantyne, C.M. Metabolic Inflammation and Insulin Resistance in Obesity. Circ. Res. 2020, 126, 1549–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, X.; Qiu, T.; Li, L.; Yu, R.; Chen, X.; Li, C.; Proud, C.G.; Jiang, T. Pathophysiology of Obesity and Its Associated Diseases. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2023, 13, 2403–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Huang, L.; Waters, M.J.; Chen, C. Insulin and Growth Hormone Balance: Implications for Obesity. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 31, 642–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasprzak, A. Molecular Sciences Insulin-Like Growth Factor 1 (IGF-1) Signaling in Glucose Metabolism in Colorectal Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, A.; Speakman, J.R.; Soltani, S.; Djafarian, K. Effect of Calorie Restriction or Protein Intake on Circulating Levels of Insulin like Growth Factor I in Humans: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 39, 1705–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, M.E.; Suarez, J.A.; Brandhorst, S.; Balasubramanian, P.; Cheng, C.W.; Madia, F.; Fontana, L.; Mirisola, M.G.; Guevara-Aguirre, J.; Wan, J.; et al. Low Protein Intake Is Associated with a Major Reduction in IGF-1, Cancer, and Overall Mortality in the 65 and Younger but Not Older Population. Cell Metab. 2014, 19, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, J.A.M.J.L. Hyperinsulinemia and Its Pivotal Role in Aging, Obesity, Type 2 Diabetes, Cardiovascular Disease and Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lega, I.C.; Lipscombe, L.L. Review: Diabetes, Obesity, and Cancer-Pathophysiology and Clinical Implications. Endocr. Rev. 2020, 41, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, R.E.; Laughlin, G.A.; LaCroix, A.Z.; Hartman, S.J.; Natarajan, L.; Senger, C.M.; Martínez, M.E.; Villaseñor, A.; Sears, D.D.; Marinac, C.R.; et al. Intermittent Fasting and Human Metabolic Health. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 115, 1203–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nencioni, A.; Caffa, I.; Cortellino, S.; Longo, V.D. Fasting and Cancer: Molecular Mechanisms and Clinical Application. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2018, 18, 707–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patikorn, C.; Roubal, K.; Veettil, S.K.; Chandran, V.; Pham, T.; Lee, Y.Y.; Giovannucci, E.L.; Varady, K.A.; Chaiyakunapruk, N. Intermittent Fasting and Obesity-Related Health Outcomes: An Umbrella Review of Meta-Analyses of Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2139558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowosad, K.; Sujka, M. Effect of Various Types of Intermittent Fasting (IF) on Weight Loss and Improvement of Diabetic Parameters in Human. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2021, 10, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, V.D.; Mattson, M.P. Fasting: Molecular Mechanisms and Clinical Applications. Cell Metab. 2014, 19, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuppelius, B.; Peters, B.; Ottawa, A.; Pivovarova-Ramich, O. Time Restricted Eating: A Dietary Strategy to Prevent and Treat Metabolic Disturbances. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 683140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, H.O.; Genario, R.; Tinsley, G.M.; Ribeiro, P.; Carteri, R.B.; Coelho-Ravagnani, C.D.F.; Mota, J.F. A Scoping Review of Intermittent Fasting, Chronobiology, and Metabolism. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 115, 991–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeb, F.; Wu, X.; Fatima, S.; Zaman, M.H.; Khan, S.A.; Safdar, M.; Alam, I.; Feng, Q. Time-Restricted Feeding Regulates Molecular Mechanisms with Involvement of Circadian Rhythm to Prevent Metabolic Diseases. Nutrition 2021, 89, 111244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, S.D.; Moehl, K.; Donahoo, W.T.; Marosi, K.; Lee, S.A.; Mainous, A.G.; Leeuwenburgh, C.; Mattson, M.P. Flipping the Metabolic Switch: Understanding and Applying the Health Benefits of Fasting. Obesity 2018, 26, 254–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dote-Montero, M.; Sanchez-Delgado, G.; Ravussin, E. Effects of Intermittent Fasting on Cardiometabolic Health: An Energy Metabolism Perspective. Nutrients 2022, 14, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Seo, Y.G.; Paek, Y.J.; Song, H.J.; Park, K.H.; Noh, H.M. Effect of Alternate-Day Fasting on Obesity and Cardiometabolic Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Metabolism 2020, 111, 154336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvie, M.; Howell, A. Potential Benefits and Harms of Intermittent Energy Restriction and Intermittent Fasting amongst Obese, Overweight and Normal Weight Subjects-A Narrative Review of Human and Animal Evidence. Behav. Sci. 2017, 7, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, Y.; Xu, S.; Huang, L.; Chen, C. Obesity and Insulin Resistance: Pathophysiology and Treatment. Drug Discov. Today 2022, 27, 822–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, R. The Effect of Fasting on Human Metabolism and Psychological Health. Dis. Markers 2022, 2022, 5653739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson, O.; Martin, B.; Stote, K.S.; Golden, E.; Maudsley, S.; Najjar, S.S.; Ferrucci, L.; Ingram, D.K.; Longo, D.L.; Rumpler, W.V.; et al. Impact of Reduced Meal Frequency without Caloric Restriction on Glucose Regulation in Healthy, Normal-Weight Middle-Aged Men and Women. Metabolism 2007, 56, 1729–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezpeleta, M.; Gabel, K.; Cienfuegos, S.; Kalam, F.; Lin, S.; Pavlou, V.; Song, Z.; Haus, J.M.; Koppe, S.; Alexandria, S.J.; et al. Effect of Alternate Day Fasting Combined with Aerobic Exercise on Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Cell Metab. 2023, 35, 56–70.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamshed, H.; Beyl, R.A.; Manna, D.L.D.; Yang, E.S.; Ravussin, E.; Peterson, C.M. Early Time-Restricted Feeding Improves 24-Hour Glucose Levels and Affects Markers of the Circadian Clock, Aging, and Autophagy in Humans. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johari, M.I.; Yusoff, K.; Haron, J.; Nadarajan, C.; Ibrahim, K.N.; Wong, M.S.; Hafidz, M.I.A.; Chua, B.E.; Hamid, N.; Arifin, W.N.; et al. A Randomised Controlled Trial on the Effectiveness and Adherence of Modified Alternate-Day Calorie Restriction in Improving Activity of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 11232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciniak, M.; Sato, M.; Rutkowski, R.; Zawada, A.; Juchacz, A.; Mahadea, D.; Grzymisławski, M.; Dobrowolska, A.; Kawka, E.; Korybalska, K.; et al. Effect of the One-Day Fasting on Cortisol and DHEA Daily Rhythm Regarding Sex, Chronotype, and Age among Obese Adults. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1078508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Y.; Walker, B.R.; Ikuta, T. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Reveals Acutely Elevated Plasma Cortisol Following Fasting but Not Less Severe Calorie Restriction. Stress 2016, 19, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, E.F.; Beyl, R.; Early, K.S.; Cefalu, W.T.; Ravussin, E.; Peterson, C.M. Early Time-Restricted Feeding Improves Insulin Sensitivity, Blood Pressure, and Oxidative Stress Even without Weight Loss in Men with Prediabetes. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 1212–1221.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moller, L.; Dalman, L.; Norrelund, H.; Billestrup, N.; Frystyk, J.; Moller, N.; Jorgensen, J.O.L. Impact of Fasting on Growth Hormone Signaling and Action in Muscle and Fat. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 94, 965–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijenhuis-Noort, E.C.; Berk, K.A.; Neggers, S.J.C.M.M.; van der Lely, A.J. The Fascinating Interplay between Growth Hormone, Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1, and Insulin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 39, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straus, D.S.; Takemoto, C.D. Effect of Fasting on Insulin-Like Growth Factor-I (IGF-I) and Growth Hormone Receptor MRNA Levels and IGF-I Gene Transcription in Rat Liver. Mol. Endocrinol. 1990, 4, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, H.; Qin, Y.L.; Shi, Z.Y.; Chen, J.H.; Zeng, M.J.; Zhou, W.; Chen, R.Q.; Chen, Z.Y. Effects of Alternate-Day Fasting on Body Weight and Dyslipidaemia in Patients with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Randomised Controlled Trial. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019, 19, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnosky, A.; Kroeger, C.M.; Trepanowski, J.F.; Klempel, M.C.; Bhutani, S.; Hoddy, K.K.; Gabel, K.; Shapses, S.A.; Varady, K.A. Effect of Alternate Day Fasting on Markers of Bone Metabolism: An Exploratory Analysis of a 6-Month Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutr. Healthy Aging 2017, 4, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trepanowski, J.F.; Kroeger, C.M.; Barnosky, A.; Klempel, M.C.; Bhutani, S.; Hoddy, K.K.; Gabel, K.; Freels, S.; Rigdon, J.; Rood, J.; et al. Effect of Alternate-Day Fasting on Weight Loss, Weight Maintenance, and Cardioprotection among Metabolically Healthy Obese Adults: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2017, 177, 930–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratton, M.T.; Albracht-Schulte, K.; Harty, P.S.; Siedler, M.R.; Rodriguez, C.; Tinsley, G.M. Physiological Responses to Acute Fasting: Implications for Intermittent Fasting Programs. Nutr. Rev. 2022, 80, 439–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cienfuegos, S.; Gabel, K.; Kalam, F.; Ezpeleta, M.; Wiseman, E.; Pavlou, V.; Lin, S.; Oliveira, M.L.; Varady, K.A. Effects of 4- and 6-h Time-Restricted Feeding on Weight and Cardiometabolic Health: A Randomized Controlled Trial in Adults with Obesity. Cell Metab. 2020, 32, 366–378.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attinà, A.; Leggeri, C.; Paroni, R.; Pivari, F.; Cas, M.D.; Mingione, A.; Dri, M.; Marchetti, M.; Di Renzo, L. Fasting: How to Guide. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlidou, E.; Papadopoulou, S.K.; Seroglou, K.; Giaginis, C. Revised Harris–Benedict Equation: New Human Resting Metabolic Rate Equation. Metabolites 2023, 13, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koppold, D.A.; Breinlinger, C.; Hanslian, E.; Kessler, C.; Cramer, H.; Khokhar, A.R.; Peterson, C.M.; Tinsley, G.; Vernieri, C.; Bloomer, R.J.; et al. International Consensus on Fasting Terminology. Cell Metab. 2024, 36, 1779–1794.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jendrike, N.; Baumstark, A.; Kamecke, U.; Haug, C.; Freckmann, G. ISO 15197: 2013 Evaluation of a Blood Glucose Monitoring System’s Measurement Accuracy. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2017, 11, 1275–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, K.S.; Tai, D.Y.; Ho, P.; Chen, C.C.; Peng, W.C.; Chen, S.T.; Hsu, C.C.; Liu, Y.P.; Hsieh, H.C.; Yang, C.C.; et al. Accuracy of the EasyTouch Blood Glucose Self-Monitoring System: A Study of 516 Cases. Clin. Chim. Acta 2004, 349, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bioassay Technology Laboratory. Human Insulin-Like Growth Factor 1 (IGF-1) ELISA Kit. Available online: https://www.bt-laboratory.com/index.php/Shop/Index/productShijiheDetail/p_id/263.html (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Saifi, B.; Majd, D.; Meshkat, N.; Amali, M. The Comparison of Serum Levels of IGF1 before and After Fasting in Healthy Adults. J. Nutr. Fast Health 2023, 11, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, A.; Kiefer, M. Comparison of Different Response Time Outlier Exclusion Methods: A Simulation Study. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 675558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, R.; Tsaih, S.W.; Petkova, S.B.; de Evsikova, C.M.; Xing, S.; Marion, M.A.; Bogue, M.A.; Mills, K.D.; Peters, L.L.; Bult, C.J.; et al. Aging in Inbred Strains of Mice: Study Design and Interim Report on Median Lifespans and Circulating IGF1 Levels. Aging Cell 2009, 8, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutchison, A.T.; Regmi, P.; Manoogian, E.N.C.; Fleischer, J.G.; Wittert, G.A.; Panda, S.; Heilbronn, L.K. Time-Restricted Feeding Improves Glucose Tolerance in Men at Risk for Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Crossover Trial. Obesity 2019, 27, 724–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnason, T.G.; Bowen, M.W.; Mansell, K.D. Effects of Intermittent Fasting on Health Markers in Those with Type 2 Diabetes: A Pilot Study. World J. Diabetes 2017, 8, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuliyanasari, N.; Zamri, E.N.; Rejeki, P.S.; Miftahussurur, M. The Impact of Ten Days of Periodic Fasting on the Modulation of the Longevity Gene in Overweight and Obese Individuals: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, S.; Ncube, M.; Zeiler, E.; Thompson, N.; Karlsen, M.C.; Goldman, D.M.; Glavas, Z.; Beauchesne, A.; Scharf, E.; Goldhamer, A.C.; et al. A Six-Week Follow-Up Study on the Sustained Effects of Prolonged Water-Only Fasting and Refeeding on Markers of Cardiometabolic Risk. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, R.; Yanovich, A.; Elbarbry, F.; Cleven, A. Adaptive Effects of Endocrine Hormones on Metabolism of Macronutrients during Fasting and Starvation: A Scoping R. eview. Metabolites 2024, 14, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Yi, P.; Liu, F. The Effect of Early Time-Restricted Eating vs Later Time-Restricted Eating on Weight Loss and Metabolic Health. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, 108, 1824–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Brereton, N.; Schweitzer, A.; Cotter, M.; Duan, D.; Børsheim, E.; Wolfe, R.R.; Pham, L.V.; Polotsky, V.Y.; Jun, J.C. Metabolic Effects of Late Dinner in Healthy Volunteers—A Randomized Crossover Clinical Trial. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 105, 2789–2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, S.; Kajiyama, S.; Hashimoto, Y.; Yamane, C.; Miyawaki, T.; Ozasa, N.; Tanaka, M.; Fukui, M. Divided Consumption of Late-Night-Dinner Improves Glycemic Excursions in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Cross-over Clinical Trial. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2017, 129, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caumo, A.; Luzi, L. First-Phase Insulin Secretion: Does It Exist in Real Life? Considerations on Shape and Function. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 287, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, S.W.; Hjort, L.; Gillberg, L.; Justesen, L.; Madsbad, S.; Brøns, C.; Vaag, A.A. Impact of Prolonged Fasting on Insulin Secretion, Insulin Action, and Hepatic versus Whole Body Insulin Secretion Disposition Indices in Healthy Young Males. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 320, E281–E290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heilbronn, L.K.; Civitarese, A.E.; Bogacka, I.; Smith, S.R.; Hulver, M.; Ravussin, E. Glucose Tolerance and Skeletal Muscle Gene Expression in Response to Alternate Day Fasting. Obes. Res. 2005, 13, 574–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemmons, D.R. Metabolic Actions of Insulin-Like Growth Factor-I in Normal Physiology and Diabetes. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. 2012, 41, 425–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.H.; Joo, Y.; Kim, M.S.; Choe, H.K.; Tong, Q.; Kwon, O. Effects of Intermittent Fasting on the Circulating Levels and Circadian Rhythms of Hormones. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 36, 745–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellinger Mendel, L.V.; Moberg, G. Circadian Insulin, GH, Prolactin, Corticosterone and Glucose Rhythms in Fed and Fasted Rats. Horm. Metab. Res. 1975, 7, 132–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, Y.; Arisue, K.; Yamamura, Y. Relationship between Circadian Rhythm of Food Intake and that of Plasma Corticosterone and Effect of Food Restriction on Circadian Adrenocortical Rhythm in the Rat. Neuroendocrinology 1977, 23, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, C.W.; Shinsako, J.; Dallman^, M.F. Daily Rhythms in Adrenal Responsiveness to Adrenocorticotropin Are Determined Primarily by the Time of Feeding in the Rat*. Endocrinology 1979, 104, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Højlund, K.; Wildner-christensen, M.; Eshøj, O.; Skjaerbaek, C.; Juul Holst, J.; Koldkjaer, O.; Møller Jensen, D.; Beck-nielsen, H.; Wildner-Christensen, M.; Es-høj, O.; et al. Reference Intervals for Glucose, β-Cell Polypeptides, and Counterregulatory Factors during Prolonged Fasting. Am. J. Physiol. Metab. 2001, 280, E50–E58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riat, A.; Suwandi, A.; Ghashang, S.K.; Buettner, M.; Eljurnazi, L.; Grassl, G.A.; Gutenbrunner, C.; Nugraha, B. Ramadan Fasting in Germany (17–18 h/Day): Effect on Cortisol and Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor in Association with Mood and Body Composition Parameters. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 697920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anemoulis, M.; Vlastos, A.; Kachtsidis, V.; Karras, S.N. Intermittent Fasting in Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review and Critical Update of Available Studies. Nutrients 2023, 15, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, J.; Kord Varkaneh, H.; Clark, C.; Zand, H.; Bawadi, H.; Ryand, P.M.; Fatahi, S.; Zhang, Y. The Influence of Fasting and Energy Restricting Diets on IGF-1 Levels in Humans: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2019, 53, 100910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakadia, J.H.; Khalid, M.U.; Heinemann, I.U.; Han, V.K. AMPK–MTORC1 Pathway Mediates Hepatic IGFBP-1 Phosphorylation in Glucose Deprivation: A Potential Molecular Mechanism of Hypoglycemia-Induced Impaired Fetal Growth. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2024, 72, e230137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, K.C.; Johannsson, G.; Leong, G.M.; Ho, K.K.Y. Estrogen Regulation of Growth Hormone Action. Endocr. Rev. 2004, 25, 693–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nørrelund, H. The Metabolic Role of Growth Hormone in Humans with Particular Reference to Fasting. Growth Horm. IGF Res. 2005, 15, 95–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, N.M.T.; Kabisch, S.; Dambeck, U.; Honsek, C.; Kemper, M.; Gerbracht, C.; Arafat, A.M.; Birkenfeld, A.L.; Schwarz, P.E.H.; Machann, J.; et al. IGF-1 and IGFBP-1 as Possible Predictors of Response to Lifestyle Intervention—Results from Randomized Controlled Trials. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.J.; Underwood, L.E.; Clemmons, D.R. Effects of Caloric or Protein Growth Factor-I (IGF-I) and Children and Adults* Restriction on Insulin-Like IGF-Binding Proteins In. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1995, 80, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Musey, V.C.; Goldstein, S.; Farmer, P.K.; Moore, P.B.; Phillips, L.S. Differential Regulation of IGF-1 and IGF-Binding Protein-1 by Dietary Composition in Humans. Am. J. Med. Sci. 1993, 305, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvie, M.N.; Pegington, M.; Mattson, M.P.; Frystyk, J.; Dillon, B.; Evans, G.; Cuzick, J.; Jebb, S.A.; Martin, B.; Cutler, R.G.; et al. The Effects of Intermittent or Continuous Energy Restriction on Weight Loss and Metabolic Disease Risk Markers: A Randomized Trial in Young Overweight Women. Int. J. Obes. 2011, 35, 714–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, K.-C.; Doyle, N.; Ballesteros, M.; Waters, M.J.; Ho, K.K.Y. Insulin Regulation of Human Hepatic Growth Hormone Receptors: Divergent Effects on Biosynthesis and Surface Translocation*. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2000, 85, 4712–4720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caputo, M.; Pigni, S.; Agosti, E.; Daffara, T.; Ferrero, A.; Filigheddu, N.; Prodam, F. Regulation of Gh and Gh Signaling by Nutrients. Cells 2021, 10, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Réda, A.; Wassil, M.; Mériem, M.; Alexia, P.; Abdelmalik, H.; Sabine, B.; Nassir, M. Food Timing, Circadian Rhythm and Chrononutrition: A Systematic Review of Time-Restricted Eating’s Effects on Human Health. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3770. [Google Scholar]

- Varady, K.A.; Bhutani, S.; Church, E.C.; Klempel, M.C. Short-Term Modified Alternate-Day Fasting: A Novel Dietary Strategy for Weight Loss and Cardioprotection in Obese Adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 90, 1138–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatzinikolaou, A.; Fatouros, I.; Petridou, A.; Jamurtas, A.; Avloniti, A.; Douroudos, I.; Mastorakos, G.; Lazaropoulou, C.; Papassotiriou, I.; Tournis, S.; et al. Adipose Tissue Lipolysis Is Upregulated in Lean and Obese Men during Acute Resistance Exercise. Diabetes Care 2008, 31, 1397–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jocken, J.W.E.; Blaak, E.E. Catecholamine-Induced Lipolysis in Adipose Tissue and Skeletal Muscle in Obesity. Physiol. Behav. 2008, 94, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriessen, C.; Doligkeit, D.; Moonen-Kornips, E.; Mensink, M.; Hesselink, M.K.C.; Hoeks, J.; Schrauwen, P. The Impact of Prolonged Fasting on 24h Energy Metabolism and Its 24h Rhythmicity in Healthy, Lean Males: A Randomized Cross-over Trial. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 42, 2353–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, T.; Khiyami, A.; Latif, T.; Fazeli, P.K. Neuroendocrine Adaptations to Starvation. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2023, 157, 106365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeke, P.M.; Greenway, F.L.; Billes, S.K.; Zhang, D.; Fujioka, K. Effect of Time Restricted Eating on Body Weight and Fasting Glucose in Participants with Obesity: Results of a Randomized, Controlled, Virtual Clinical Trial. Nutr. Diabetes 2021, 11, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, K.L.; Clifton, P.M.; Keogh, J.B.; Keogh, J.B. The Effect of Intermittent Energy Restriction on Weight Loss and Diabetes Risk Markers in Women with a History of Gestational Diabetes: A 12-Month Randomized Control Trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 114, 794–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | ADMF (n = 7) | TRF (n = 8) | Control (n = 7) | -Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, year a | 21.14 ± 1.95 | 22.25 ± 1.98 | 21.28 ± 1.6 | 0.664 |

| Systolic BP, mmHg a | 111 ± 10.53 | 119.85 ± 9.45 | 114.66 ± 8.71 | 0.585 |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg a | 78 ± 3.80 | 81.42 ± 7.74 | 82.66 ± 8.14 | 0.564 |

| hemoglobin, g/dL a | 12.62 ± 1.59 | 12.37 ± 1.33 | 12.50 ± 1.44 | 0.947 |

| Weight, kg a | 75.24 ± 9.33 | 76.4 ± 10.43 | 72.81 ± 12.27 | 0.809 |

| BMI, kg/m2 b | 31.4 (27–33.2) | 30.7 (27.2–32.07) | 28.2 (25.2–30) | 0.429 |

| Body Fat, % b | 38 (34.6–39.4) | 38.05 (34.85–39.2) | 36.5 (36.2–38.2) | 0.936 |

| Visceral fat rating b | 11 (7–13.5) | 10.5 (7.62–12.12) | 8 (6–10) | 0.337 |

| Skeletal muscle, kg b | 22.8 (22.4–24) | 23 (22.55–25.1) | 23.3 (22.1–24.7) | 0.697 |

| FBG, mg/dL a | 102 ± 10.81 | 98.62 ± 11.21 | 101 ± 6.48 | 0.792 |

| IGF-1, ng/mL c | 207.38 ± 104.55 | 209.4 ± 40.92 | 131.62 ± 32.9 | 0.098 |

| Variable | Group | Pretest | Posttest | -Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight, kg | ADMF (n = 7) b | 75.24 ± 9.33 | 74.29 ± 9.61 | 0.047 * |

| TRF (n = 8) b | 76.4 ± 10.43 | 75.72 ± 10.47 | 0.222 | |

| Control (n = 7) b | 72.81 ±12.27 | 73.4 ± 11.66 | 0.349 | |

| Body Fat, % | ADMF (n = 7) b | 38 (34.6–39.4) | 37.4 (34.4–39.2) | 0.370 |

| TRF (n = 8) b | 38.05 (34.85–39.2) | 38.35 (35.7–38.92) | 0.351 | |

| Control (n = 7) a | 36.5 (36.2–38.2) | 35.7 (35.1–39.4) | 0.765 | |

| Visceral fat rating | ADMF (n = 7) b | 11 (7–13.5) | 10.5 (7–13) | 0.017 * |

| TRF (n = 8) a | 10.5 (7.62–12.12) | 10.5 (7.45–11.87) | 0.739 | |

| Control (n = 7) a | 8 (6–10) | 8 (6–10) | 0.785 | |

| Skeletal muscle, kg | ADMF (n = 7) b | 22.8 (22.4–24) | 22.7 (20.6–24) | 0.498 |

| TRF (n = 8) b | 23 (22.55–25.1) | 22.95 (22.75–23.32) | 0.161 | |

| Control (n = 7) a | 23.3 (22.1–24.7) | 23.5 (22.1–24.3) | 0.463 |

| Variable | Group | Pretest | Posttest | -Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FBG (mg/dL) | ADMF (n = 7) | 102 ± 10.81 | 112.14 ± 6.06 | 0.036 * |

| TRF (n = 8) | 98.42 ± 12.09 | 113.71 ± 11.3 | 0.001 * | |

| Control (n = 7) | 101.5 ± 6.16 | 108.37 ± 8.37 | 0.066 |

| Variable | Group | Pretest | Posttest | -Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IGF-1 (ng/mL) | ADMF (n = 7) b | 205.12 (97.19–312.48) | 196.33 (182.45–217.38) | 0.995 |

| TRF (n = 8) b | 199.10 (183.32–220.12) | 103.94 (83.36–112.27) | <0.001 * | |

| Control (n = 7) a | 120.81 (92.50–164.20) | 172.66 (158.49–211.01) | 0.043 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rachmayanti, D.A.; Rejeki, P.S.; Argarini, R.; Novida, H.; Soenarti, S.; Halim, S.; Permataputri, C.D.A.; Purnomo, S.P. Effects of Short-Term (20-Day) Alternate-Day Modified Fasting and Time-Restricted Feeding on Fasting Glucose and IGF-1 in Obese Young Women. Diseases 2025, 13, 390. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13120390

Rachmayanti DA, Rejeki PS, Argarini R, Novida H, Soenarti S, Halim S, Permataputri CDA, Purnomo SP. Effects of Short-Term (20-Day) Alternate-Day Modified Fasting and Time-Restricted Feeding on Fasting Glucose and IGF-1 in Obese Young Women. Diseases. 2025; 13(12):390. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13120390

Chicago/Turabian StyleRachmayanti, Dian Aristia, Purwo Sri Rejeki, Raden Argarini, Hermina Novida, Sri Soenarti, Shariff Halim, Chy’as Diuranil Astrid Permataputri, and Sheeny Priska Purnomo. 2025. "Effects of Short-Term (20-Day) Alternate-Day Modified Fasting and Time-Restricted Feeding on Fasting Glucose and IGF-1 in Obese Young Women" Diseases 13, no. 12: 390. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13120390

APA StyleRachmayanti, D. A., Rejeki, P. S., Argarini, R., Novida, H., Soenarti, S., Halim, S., Permataputri, C. D. A., & Purnomo, S. P. (2025). Effects of Short-Term (20-Day) Alternate-Day Modified Fasting and Time-Restricted Feeding on Fasting Glucose and IGF-1 in Obese Young Women. Diseases, 13(12), 390. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13120390