External Carotid Artery Entrapment by the Hyoid Bone Associated with an Atherosclerotic Stenosis of the Internal Carotid Artery

Abstract

1. Introduction

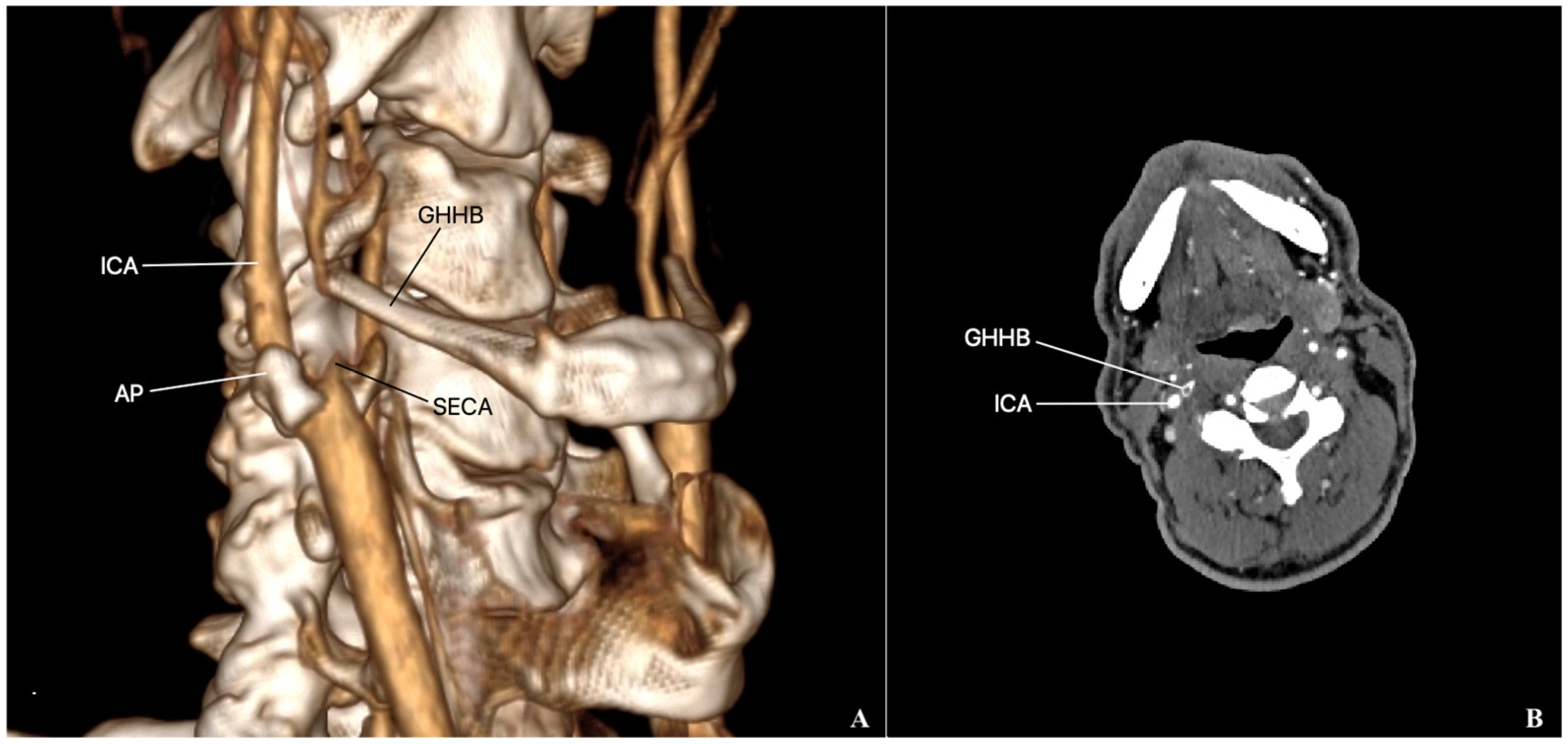

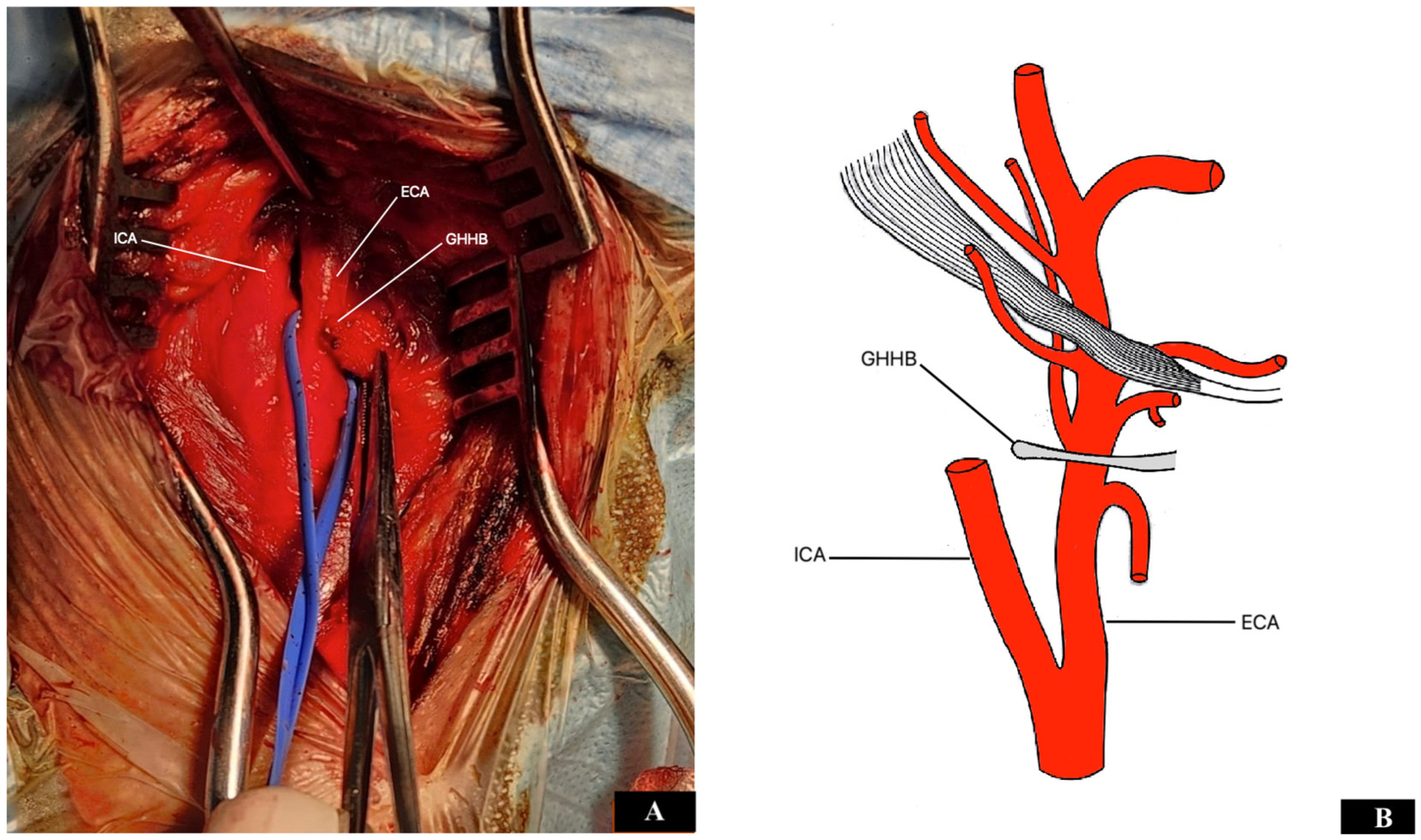

2. Case Presentation

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Keshelava, G.; Nachkepia, M.; Arabidze, G.; Janashia, G.; Beselia, K. Unusual positional compression of the internal carotid artery causes carotid thrombosis and cerebral ischemia. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2012, 26, 572.e15–572.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Wang, Y.; Chu, C.; Ren, Y.; Hua, Y.; Ji, X.; Song, H. Hyoid elongation may be a rare cause of recurrent ischemic stroke in youth—A case report and literature review. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 653471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keshelava, G.; Robakidze, Z. Cervical vagal schwannoma causing asymptomatic internal carotid artery compression. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2020, 63, 460.e9–460.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.G.; Kortmann, H. Pseudoaneurysm of the common carotid artery due to ongoing trauma from the hyoid bone. J. Vasc. Surg. 2007, 45, 186–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelaziz, O.S.; Ogilvy, C.S.; Lev, M. Is there a potential role for hyoid bone compression in pathogenesis of carotid artery stenosis? Surg. Neurol. 1999, 51, 650–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukawa, S.; Yamamoto, S.; Hara, H. Carotid artery dissection associated with an elongated hyoid bone. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2014, 23, e411–e412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopuz, C.; Ortug, G. Variable morphology of the hyoid bone in Anatolian population: Clinical implications—A cadaveric study. Int. J. Morphol. 2016, 34, 1396–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paz, F.J.; Rueda, C.; Barbosa, M.; Garcia, M.; Pastor, J.F. Biometry and statistical analysis of the styloid process. Anat. Rec. 2012, 295, 742–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plotkin, A.; Bartley, M.G.; Bowser, K.E.; Yi, J.A.; Magee, G.A. Carotid artery entrapment by the hyoid bone—A rare cause of recurrent strokes in a young patient. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2019, 57, 48.e7–48.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshelava, G.; Robakidze, Z. Iternal carotid artery stenosis and entrapment by the hyoid bone. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2024, 68, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludt, C.; Leppert, M.; Jones, A.; Song, J.; Kuwayama, D.; Pastula, D.M.; Poisson, S. Multiple strokes associated with elongation of the hyoid bone. Neurohospitalist 2018, 8, 35–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bakker, B.S.; de Bakker, H.M.; Soerdjbalie-Maikoe, V.; Dikkers, F.G. The development of the human hyoid-larynx complex revisited. Laryngoscope 2018, 128, 1829–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fakhry, N.; Puymerail, L.; Michel, J.; Santini, L.; Lebreton-Chakour, C.; Robert, D.; Giovanni, A.; Adalian, P.; Dessi, P. Analysis of hyoid bone using 3D geometric morphometrics: An anatomical study and dissection of potential clinical implications. Dysphagia 2013, 28, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.; Kohli, A.; Aggarwal, N.K.; Banerjee, K.K. Study of age of fusion of hyoid bone. Leg. Med. 2008, 10, 253–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, K.C.; Wang, X.R. Anatomic study on the syndrome of greater-hyoid horn. Chin. Clin. Anat. 1995, 13, 286–288. [Google Scholar]

- Manta, M.D.; Rusu, M.C.; Hostiuc, S.; Vrapciu, A.D.; Manta, B.A.; Jianu, A.M. The carotid-hyoid topography is variable. Medicina 2023, 59, 1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolbel, T.; Holst, J.; Lindh, M.; Matzsch, T. Carotid artery entrapment by the hyoid bone. J. Vasc. Surg. 2008, 48, 1022–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Liu, Y.; Tang, H.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, H.; Liu, H. Hyoid bone compression—Induced carotid dissecting aneurysm: A case report. Exp. Ther. Med. 2023, 26, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Nezami, N.; Dardik, A.; Nassiri, N. Hyoid bone impingement contributing to symptomatic atherosclerosis of the carotid bifurcation. J. Vasc. Surg. Cases Innov. Tech. 2020, 6, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, O.; Fresilli, M.; Jabbour, J.; Di Girolamo, A.; Irace, L. Internal carotid stenosis associated with compression by hyoid bone. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2019, 58, 379.e1–379.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, T.; Moribe, K.; Ito, K.; Kabeya, R. Carotid endarterectomy requiring removal of the superior horn of thyroid cartilage: Case report and literature review. NMC Case Rep. J. 2021, 8, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, L.K.; Bates, T.R.; Thompson, A.; Dharsono, F.; Prentice, D. Cerebral embolism and carotid-hyoid impingement syndrome. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2019, 64, 27–29. [Google Scholar]

- Dao, A.; Karnezis, S.; Lan III, J.S.; Fujitani, R.M.; Saremi, F. Eagle syndrome presenting with external carotid artery pseudoaneurysm. Emerg. Radiol. 2011, 18, 263–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, M.; Yamamoto, H.; Koga, M.; Okatsu, H.; Shono, Y.; Toyoda, K.; Fukuda, K.; Lihara, K.; Yamada, N.; Minematsu, K. Hyoid bone compression—Induced repetitive occlusion and recanalization of the internal carotid artery in a patient with ipsilateral brain and retinal ischemia. Arch. Neurol. 2011, 68, 258–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Campos, F.P.F.; Kanegae, M.; Aiello, V.D.; Dos Santos Neto, P.J.; Gratao, T.C.; Silva, E.S. Traumatic injury to the internal carotid artery by the hyoid bone: A rare cause of ischemic stroke. Autops. Case Rep. 2018, 8, e2018010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handa, J.; Matsuda, M.; Handa, H. Lateral position of the external carotid artery. Report of a case. Radiology 1972, 102, 361–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teal, J.S.; Rumbaugh, C.L.; Bergeron, R.T.; Segall, H.D. Lateral position of the external carotid artery: A rare anomaly? Radiology 1973, 108, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamide, T.; Nomura, M.; Tamase, A.; Mori, K.; Seki, S.; Kitamura, Y.; Nakada, M. Simple classification of carotid bifurcation: Is it possible to predict twisted carotid artery during carotid endarterectomy? Acta Neurochir. 2016, 158, 2393–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katano, H.; Yamada, K. Carotid endarterectomy for stenosis of twisted carotid bifurcations. World Neurosurg. 2010, 73, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathuria, S.; Gregg, L.; Chen, J.; Gandhi, D. Normal cerebral arterial development and variations. Semin. Ultrasound CT MRI 2011, 32, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menshawi, K.; Mohr, J.; Gutierrez, J. A functional perspective on the embryology and anatomy of the cerebral blood supply. J. Stroke 2015, 17, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadler, T.W. Langman’s Medical Embryology, 14th ed.; Wolters Luwer Health: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cairney, J. Tortuosity of the cervical segment of the internal carotid artery. J. Anat. 1924, 59, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, Y.; Kanetaka, H.; Kim, Y.H.; Okayama, K.; Kano, M.; Kikuchi, M. Age-related morphological changes in the human hyoid bone. Cells Tissues Organs 2005, 180, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamensky, A.V.; Pipinos, I.I.; Carson, J.S.; MacTaggart, J.N.; Baxter, B.T. Age and disease-related geometric and structural remodeling of the carotid artery. J. Vasc. Surg. 2015, 62, 1521–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.W.; Walker, P.L.; O’Halloran, R.L. Age and sex-related variation in hyoid bone morphology. J. Forensic Sci. 1998, 43, 1138–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abruzzo, T.A.; Geller, J.I.; Kimbrough, D.A.; Michaels, S.; Correa, Z.; Cornall, K.; Augsburger, J.J. Adjunctive techniques for optimization of ocular hemodynamics in children undergoing ophthalmic artery infusion chemotherapy. J. Neurointerv. Surg. 2015, 7, 770–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Keshelava, G.; Robakidze, Z.; Tsiklauri, D. External Carotid Artery Entrapment by the Hyoid Bone Associated with an Atherosclerotic Stenosis of the Internal Carotid Artery. Diseases 2024, 12, 258. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases12100258

Keshelava G, Robakidze Z, Tsiklauri D. External Carotid Artery Entrapment by the Hyoid Bone Associated with an Atherosclerotic Stenosis of the Internal Carotid Artery. Diseases. 2024; 12(10):258. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases12100258

Chicago/Turabian StyleKeshelava, Grigol, Zurab Robakidze, and Devi Tsiklauri. 2024. "External Carotid Artery Entrapment by the Hyoid Bone Associated with an Atherosclerotic Stenosis of the Internal Carotid Artery" Diseases 12, no. 10: 258. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases12100258

APA StyleKeshelava, G., Robakidze, Z., & Tsiklauri, D. (2024). External Carotid Artery Entrapment by the Hyoid Bone Associated with an Atherosclerotic Stenosis of the Internal Carotid Artery. Diseases, 12(10), 258. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases12100258