Ocular Manifestations of Pediatric Rhinosinusitis: A Comprehensive Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Study Selection and Data Extraction

2.3. Data Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. What Are the Most Commonly Reported Ocular Manifestations Associated with Pediatric Rhinosinusitis and What Is Their Prevalence?

3.2. Are There Any Specific Risk Factors or Predictors for Developing Ocular Complications in Children with Rhinosinusitis?

3.3. How Do the Types and Severity of Ocular Manifestations Vary Based on the Age of the Pediatric Patient or the Duration of Rhinosinusitis?

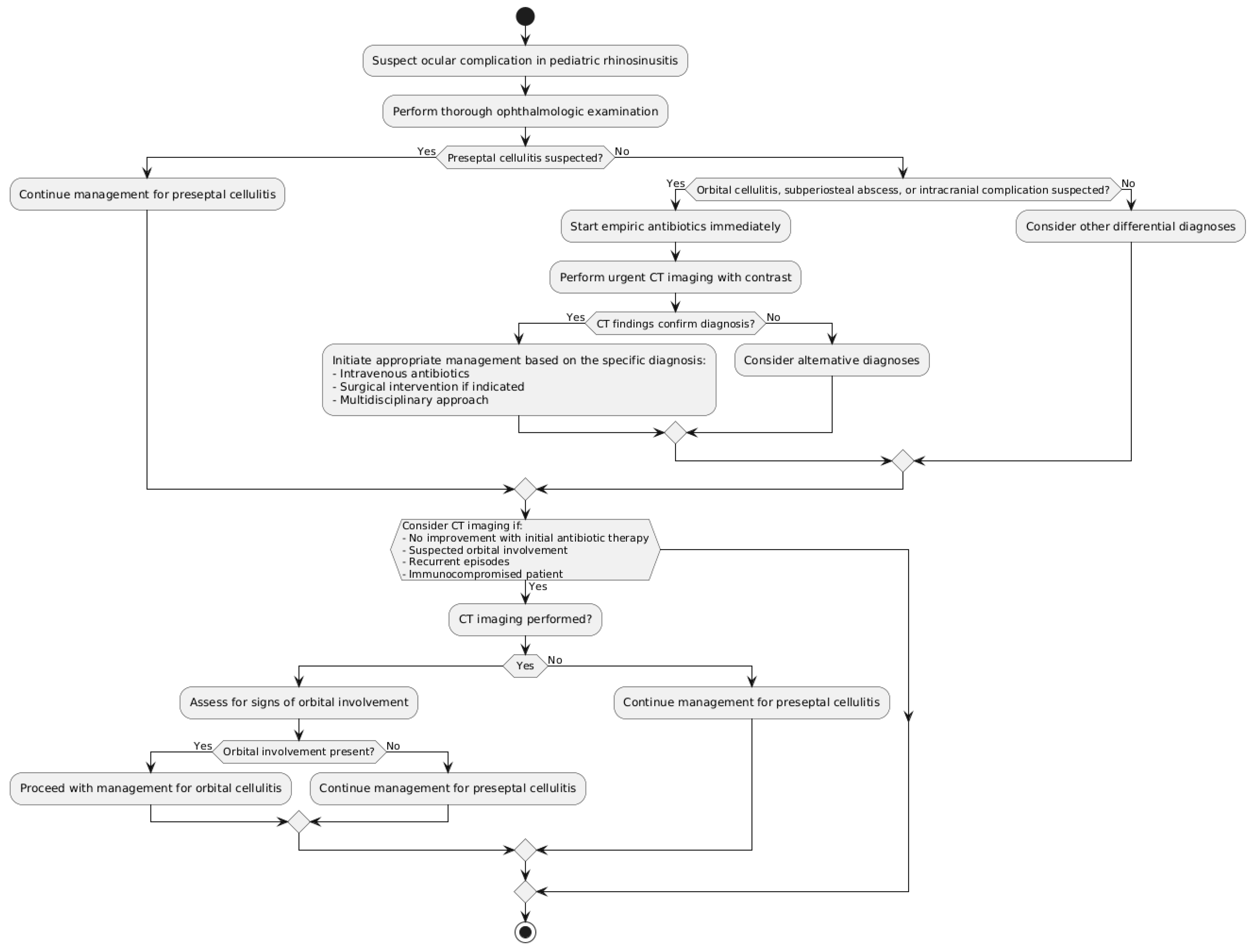

3.4. What Are the Most Effective Diagnostic Tools and Imaging Modalities for Identifying and Assessing Ocular Complications in Children with Rhinosinusitis?

3.5. What Are the Current Treatment Approaches (Medical and Surgical) for Managing Different Types of Ocular Manifestations in Pediatric Rhinosinusitis and How Do They Compare in Terms of Outcomes?

3.6. Are There Any Long-Term Visual or Ophthalmologic Sequelae Associated with Ocular Complications of Pediatric Rhinosinusitis and How Can They Be Prevented or Managed?

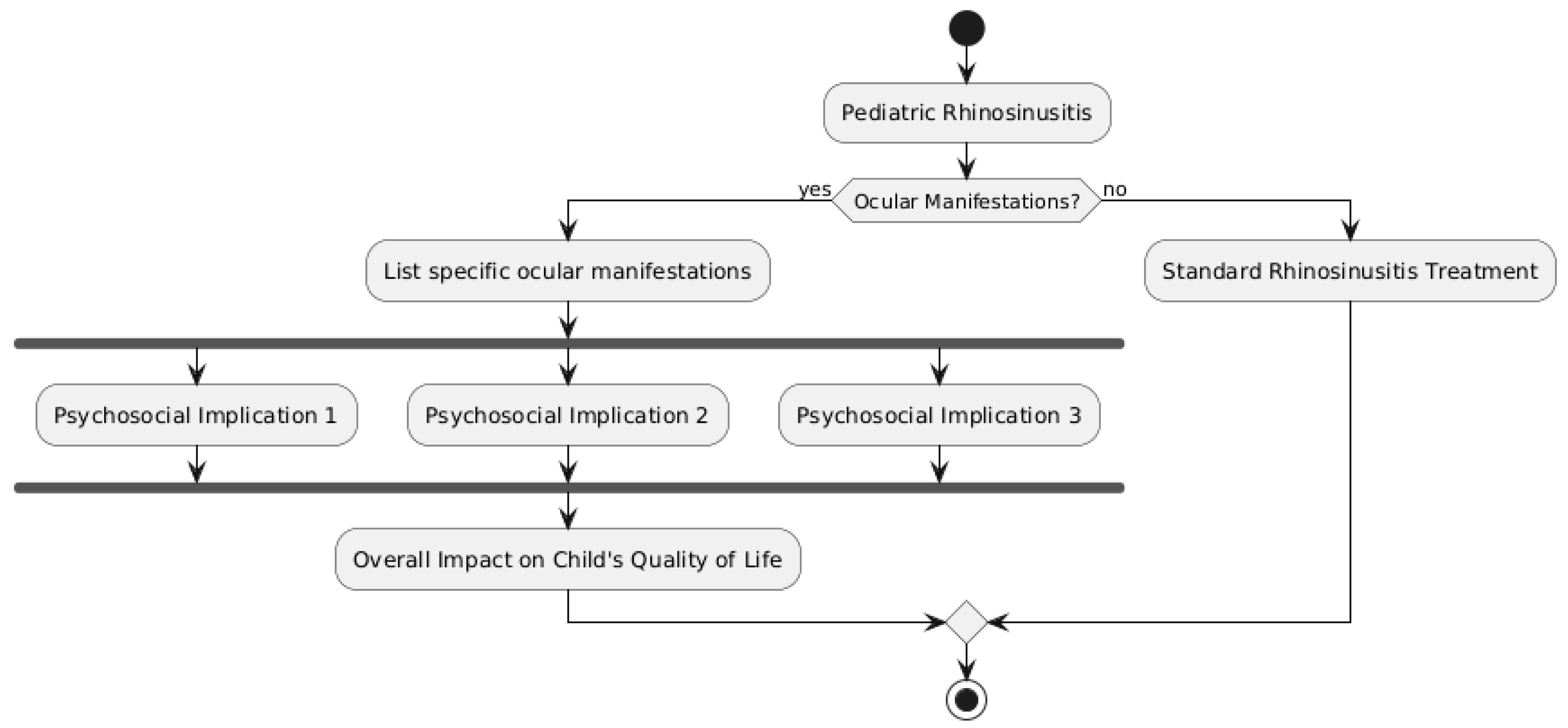

3.7. How Do Ocular Manifestations Impact the Quality of Life and Daily Functioning of Children with Rhinosinusitis and What Are the Psychosocial Implications for Patients and Their Families?

3.8. Are There Any Disparities in the Incidence, Diagnosis, or Management of Ocular Complications Based on Factors Such as Geographic Location, Socioeconomic Status, or Healthcare Access?

3.9. What Are the Current Gaps in Knowledge and Understanding of Ocular Manifestations in Pediatric Rhinosinusitis and What Areas Require Further Research to Improve Patient Outcomes?

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions/Future Directions

Study Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wald, E.R.; Applegate, K.E.; Bordley, C.; Darrow, D.H.; Glode, M.P.; Marcy, S.M.; Nelson, C.E.; Rosenfeld, R.M.; Shaikh, N.; Smith, M.J.; et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Acute Bacterial Sinusitis in Children Aged 1 to 18 Years. Pediatrics 2013, 132, e262–e280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garbutt, J.; Goldstein, M. Acute Sinusitis in Children. BMJ Best Practice. 2021. Available online: https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-us/672 (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Siedek, V.; Kremer, A.; Betz, C.S. Sinusitis and orbital complications. HNO 2019, 67, 427–436. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, Y.; Shi, G.; Wang, H. Treatment of Orbital Complications Following Acute Rhinosinusitis in Children. Balk. Med. J. 2016, 33, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eviatar, E.; Gavriel, H.; Pitaro, K.; Vaiman, M.; Goldman, M.; Kessler, A. Conservative treatment in rhinosinusitis orbital complications in children aged 2 years and younger. Rhinology 2008, 46, 334–337. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Botting, A.M.; McIntosh, D.; Mahadevan, M. Paediatric pre- and post-septal peri-orbital infections are different diseases: A retrospective review of 262 cases. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2008, 72, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinis, V.; Ozbay, M.; Bakir, S.; Yorgancilar, E.; Gun, R.; Akdag, M.; Sahin, M.; Topcu, I. Management of Orbital Complications of Sinusitis in Pediatric Patients. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2013, 24, 1706–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedwell, J.; Bauman, N.M. Management of pediatric orbital cellulitis and abscess. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2011, 19, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todman, M.S.; Enzer, Y.R. Medical Management Versus Surgical Intervention of Pediatric Orbital Cellulitis: The Importance of Subperiosteal Abscess Volume as a New Criterion. Ophthalmic Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2011, 27, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayonne, E.; Kania, R.; Tran, P.; Huy, B.; Herman, P. Intracranial complications of rhinosinusitis. A review, typical imaging data and algorithm of management. Rhinology 2009, 47, 59–65. [Google Scholar]

- Rudloe, T.F.; Harper, M.B.; Prabhu, S.P.; Rahbar, R.; VanderVeen, D.; Kimia, A.A. Acute periorbital infections: Who needs emergent imaging? Pediatrics 2010, 125, e719–e726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsch, C.F.; Byrne, P.J. Imaging of orbital infections and inflammations. Neuroimaging Clin. 2014, 24, 467–489. [Google Scholar]

- Jabarin, B.; Mahajna, M.; Abuali, N.; Taha, A.; Imtanis, K.; Abu-Snieneh, H.; Masalha, M.; Bachner-Hinenzon, N.; Bilavsky, E.; Omet, D. Orbital complications of rhinosinusitis in the adult population: Analysis of cases presenting to a tertiary medical center over a 13-year period. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2021, 11, 676–684. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.; Meng, X.; Lou, H. Progress on diagnosis and treatment of pediatric acute rhinosinusitis orbital complications. Lin Chuang Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi=J. Clin. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2019, 33, 446–449. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler, J.R.; Langenbrunner, D.J.; Stevens, E.R. The pathogenesis of orbital complications in acute sinusitis. Laryngoscope 1970, 80, 1414–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younis, R.T.; Anand, V.K.; Davidson, B. The Role of Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Patients with Sinusitis with Complications. Laryngoscope 2002, 112, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobol, S.E.; Marchand, J.; Tewfik, T.L.; Manoukian, J.J.; Schloss, M.D. Orbital Complications of Sinusitis in Children. J. Otolaryngol. 2002, 31, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seltz, L.B.; Smith, J.; Durairaj, V.D.; Enzenauer, R.; Todd, J. Microbiology and Antibiotic Management of Orbital Cellulitis. Pediatrics 2011, 127, e566–e572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torretta, S.; Guastella, C.; Marchisio, P.; Marom, T.; Bosis, S.; Ibba, T.; Drago, L.; Pignataro, L. Sinonasal-Related Orbital Infections in Children: A Clinical and Therapeutic Overview. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, M.P.; McNab, A.A. Current treatment and outcome in orbital cellulitis. Aust. N. Z. J. Ophthalmol. 1999, 27, 375–379. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhry, I.A.; Shamsi, F.A.; Elzaridi, E.; Al-Rashed, W.; Al-Amri, A.; Al-Anezi, F.; Arat, Y.O.; Holck, D.E. Outcome of Treated Orbital Cellulitis in a Tertiary Eye Care Center in the Middle East. Ophthalmology 2007, 114, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgakopoulos, C.D.; Eliopoulou, M.I.; Stasinos, S.; Exarchou, A.; Pharmakakis, N.; Varvarigou, A. Periorbital and Orbital Cellulitis: A 10-Year Review of Hospitalized Children. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2010, 20, 1066–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenberg, M.F.; Pollard, Z.F. Nonsurgical management of subperiosteal abscess of the orbit: A computerized tomography scan/magnetic resonance imaging-based study. J. AAPOS 1998, 2, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erickson, B.P.; Lee, W.W. Orbital Cellulitis and Subperiosteal Abscess: A 5-year Outcomes Analysis. Orbit 2015, 34, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayman, G.L.; Adams, G.L.; Paugh, D.R.; Koopmann, C.F. Intracranial complications of paranasal sinusitis: A combined institutional review. Laryngoscope 1991, 101, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weakley, D.R. Complications of pediatric paranasal sinusitis. Pediatr. Ann. 1991, 20, 632–638. [Google Scholar]

- Filips, A.; Jain, S. Pediatric orbital cellulitis. J. Am. Acad. Physician Assist. 2021, 34, 30–34. [Google Scholar]

- Dewan, M.A.; Meyer, D.R.M.; Wladis, E.J. Orbital Cellulitis with Subperiosteal Abscess: Demographics and Management Outcomes. Ophthalmic Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2011, 27, 330–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eviatar, E.; Sandbank, J.; Kleid, S.; Gavriel, H. The role of osteitis in pediatric rhinosinusitis and its complications. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2016, 87, 104–107. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, S.; Durand, M.L.; Cunningham, M.J. Sinogenic orbital and subperiosteal abscesses: Microbiology and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus incidence. Otolaryngol. Neck Surg. 2010, 143, 392–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brook, I. Microbiology and antimicrobial treatment of orbital and intracranial complications of sinusitis in children and their management. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2009, 73, 1183–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, G.J. Subperiosteal abscess of the orbit: Age as a factor in the bacteriology and response to treatment. Ophthalmology 1996, 103, 205–206. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, C.F.; Huang, Y.C.; Wang, C.J.; Chiu, C.H.; Lin, T.Y. Clinical analysis of computed tomography-staged orbital cellulitis in children. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2007, 40, 518–524. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Neto, L.M.; Pignatari, S.; Mitsuda, S.; Fava, A.S.; Stamm, A. Acute Sinusitis in Children—A retrospective study of orbital complications. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2007, 73, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Liu, E.S.; Le, T.D.; Adatia, F.A.; Buncic, J.R.; Blaser, S.; Richardson, S. Pediatric orbital cellulitis in the Haemophilus influenzae vaccine era. J. Am. Assoc. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Strabismus 2015, 19, 206–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambati, B.K.; Ambati, J.; Azar, N.; Stratton, L.; Schmidt, E.V. Periorbital and orbital cellulitis before and after the advent of Haemophilus influenzae type B vaccination. Ophthalmology 2000, 107, 1450–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vu, B.L.L.; Dick, P.T.; Levin, A.V.; Pirie, J. Development of a clinical severity score for preseptal cellulitis in children. Ophthalmology 2003, 19, 302–307. [Google Scholar]

- Nageswaran, S.; Woods, C.R.; Benjamin, D.K.J.; Givner, L.B.; Shetty, A.K. Orbital Cellulitis in Children. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2006, 25, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxford, L.E.; McClay, J. Complications of Acute Sinusitis in Children. Otolaryngol. Neck Surg. 2005, 133, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosbie, R.A.; Nairn, J.; Kubba, H. Management of paediatric periorbital cellulitis: Our experience of 243 children managed according to a standardised protocol 2012–2015. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2016, 87, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welkoborsky, H.J.; Graß, S.; Deichmüller, C.; Bertram, O.; Hinni, M.L. Orbital complications in children: Differential diagnosis of a challenging disease. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2015, 272, 1157–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsirouki, T.; Dastiridou, A.I.; Ibánez Flores, N.; Cerpa, J.C.; Moschos, M.M.; Brazitikos, P.; Androudi, S. Orbital cellulitis. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2018, 63, 534–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabarin, B.; Eviatar, E.; Israel, O.; Marom, T.; Gavriel, H. Indicators for imaging in periorbital cellulitis secondary to rhinosinusitis. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2018, 275, 943–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrmann, B.W.; Forsen, J.W., Jr.; Milstein, J.M.; Winn, H.R. Intracranial complications of pediatric frontal rhinosinusitis. Am. J. Rhinol. 2004, 18, 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepahdari, A.R.; Aakalu, V.K.; Kapur, R.; Michals, E.A.; Saran, N.; French, A.; Mafee, M.F. MRI of Orbital Cellulitis and Orbital Abscess: The Role of Diffusion-Weighted Imaging. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2009, 193, W244–W250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Zhao, G.; Yang, S.; Lin, J.; Hu, L.; Che, C.; Wang, Q.; Xu, Q. A retrospective analysis of eleven cases of invasive rhino-orbito-cerebral mucormycosis presented with orbital apex syndrome initially. BMC Ophthalmol. 2016, 16, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarabishy, A.B.; Khatib, B.; Nocero, J.; Behrens, A. The use of ultrasound biomicroscopy in the diagnosis of orbital sarcoid granuloma with extraocular muscle involvement. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2015, 23, 86–89. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, J.R.; Michelson, M.A. Diagnosing and treating pediatric orbital cellulitis. Rev. Ophthalmol. 2008, 15, 76–79. [Google Scholar]

- Skedros, D.G.; Haddad, J. Preseptal and orbital cellulitis. Pediatr. Rev. 2014, 35, 408–409. [Google Scholar]

- Babar, T.F.; Zaman, M.; Khan, M.N.; Khan, M.D. Risk factors of preseptal and orbital cellulitis. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 2009, 19, 39–42. [Google Scholar]

- Yen, M.T.; Yen, K.G. Effect of Corticosteroids in the Acute Management of Pediatric Orbital Cellulitis with Subperiosteal Abscess. Ophthalmic Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2005, 21, 363–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, G.H.; Harris, G.J.; Criteria, S.T. Criteria for nonsurgical management of subperiosteal abscess of the orbit: Analysis of outcomes 1988–1998. Ophthalmology 2000, 107, 1454–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahbar, R.; Robson, C.D.; Petersen, R.A.; DiCanzio, J.; Rosbe, K.W.; McGill, T.J.; Healy, G.B. Management of Orbital Subperiosteal Abscess in Children. Arch. Otolaryngol. Neck Surg. 2001, 127, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, T.O.; Wort, R.; Fang, T.; Marcellus, D.; Bawden, L. Endoscopic orbital abscess decompression: 10-year case series. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2019, 133, 777–781. [Google Scholar]

- Benoit, M.M.; Silvera, V.M.; Nichollas, R.; Jones, D.; McGill, T.; Rahbar, R. Image guidance systems for minimally invasive sinus and skull base surgery in children. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2009, 73, 1452–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxford, L.E.; McClay, J. Medical and surgical management of subperiosteal orbital abscess secondary to acute sinusitis in children. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2006, 70, 1853–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavriel, H.; Yeheskeli, E.; Aviram, E.; Yehoshua, L.; Eviatar, E. Dimension of Subperiosteal Orbital Abscess as an Indication for Surgical Management in Children. Otolaryngol. Neck Surg. 2011, 145, 823–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moloney, J.R.; Badham, N.J. The acute orbit. Preseptal (periorbital) cellulitis, subperiosteal abscess and orbital cellulitis due to sinusitis. J. Laryngol. Otol. 1989, 103 (Suppl. 12), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skedros, D.G.; Bluestone, C.D.; Curtin, H.D.; Haddad, J. Subperiosteal orbital abscess in children: Diagnosis, microbiology, and management. Laryngoscope 1993, 103, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patt, B.S.; Manning, S.C. Blindness resulting from orbital complications of sinusitis. Otolaryngol. Neck Surg. 1991, 104, 789–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, R.T.; Lazar, R.H.; Anand, V.K. Intracranial Complications of Sinusitis: A 15-Year Review of 39 Cases. Ear Nose Throat J. 2002, 81, 636–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vairaktaris, E.; Moschos, M.M.; Vassiliou, S.; Baltatzis, S.; Kalimeras, E.; Avgoustidis, D.; Moschos, M.N.; Pappas, Z. Orbital cellulitis, orbital subperiosteal and intraorbital abscess: Report of three cases and review of the literature. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2009, 37, 132–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, C.T.; Cheng, C.Y.; Lin, C.J.; Hsu, W.C.; Lee, S.M. Dacryocystorhinostomy for the treatment of epiphora in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis and paranasal sinus mucocele. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2020, 119, 1252–1257. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen, A.G.; Mansour, K.; Bos, J.J.; Manoliu, R.A. Abscess of the orbit and paranasal sinuses: A case series and a review of the literature. Acta Ophthalmol. 2001, 79, 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Howe, L.; Jones, N. Guidelines for the management of periorbital cellulitis/abscess. Clin. Otolaryngol. 2004, 29, 725–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoem, S.R.; Wenger, D.E.; Thompson, D.M. Management of pediatric orbital cellulitis. Otolaryngol. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 53, 103–112. [Google Scholar]

- Kastner, J.; Taudy, M.; Lisy, J.; Grabec, P.; Betka, J. Orbital and intracranial complications after acute rhinosinusitis. Rhinology 2010, 48, 457–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoxworth, J.M.; Glastonbury, C.M. Orbital and Intracranial Complications of Acute Sinusitis. Neuroimaging Clin. N. Am. 2010, 20, 511–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magliocca, K.R.; Vivas, E.X.; Grundfast, K.M. Pediatric orbital cellulitis: Clinical course and management. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2012, 33, 395–399. [Google Scholar]

- Ozkaya, E.; Çakir, F.Ç.; Yildiz, Y.; Gencer, Z.K. Psychosocial aspects of mothers of children with orbital cellulitis. J. Psychiatry Neurol. Sci. 2015, 28, 328–334. [Google Scholar]

- Teke, T.; Tanir, G.; Ozdemir, M.; Bayhan, G.İ.; Duman, M.; Unal, O. Quality of life in children with chronic suppurative otitis media and impact of treatment on the quality of life. Turk. J. Pediatr. 2014, 56, 506–511. [Google Scholar]

- Fokkens, W.J.; Lund, V.J.; Hopkins, C.; Hellings, P.W.; Kern, R.; Reitsma, S.; Toppila-Salmi, S.; Bernal-Sprekelsen, M.; Mullol, J.; Alobid, I. European position paper on rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps 2020. Rhinology 2020, 58 (Suppl. 29), 1–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higginbotham, L.; Tuli, S.; Horton, P. The evaluation and management of pediatric orbital cellulitis: A systematic review. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2019, 33, 462–468. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, D.J.; Gonzales, R.; Cabana, M.D.; Hersh, A.L. National Trends in Visit Rates and Antibiotic Prescribing for Children with Acute Sinusitis. Pediatrics 2011, 127, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piatt, J.H. Intracranial suppuration complicating sinusitis among children: An epidemiological and clinical study. J. Neurosurg. Pediatr. 2011, 7, 567–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedaghat, A.R.; Wilke, C.O.; Cunningham, M.J.; Ishman, S.L. Socioeconomic disparities in the presentation of acute bacterial sinusitis complications in children. Laryngoscope 2013, 124, 1700–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.S.; Hsu, C.Y.; Jang, J.W. Bacteriology of chronic sinusitis in relation to sinusitis-associated intracranial suppuration. Laryngoscope 1999, 109, 1328–1331. [Google Scholar]

- Lal, D.; Rounds, A.B.; Dodick, D.W.; Djalilian, H.; Pynnonen, M.A.; Hwang, P.H.; Shahangian, A.; Kirsch, C.F.E.; Scott, B.L.; Horesh, E. Multi-institutional study of orbital and intracranial complications of acute rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope 2022, 132, 518–523. [Google Scholar]

- Crock, C.; Ting, S.; Wormald, P.J. Multidisciplinary management of paediatric orbital cellulitis. Aust. J. Otolaryngol. 2011, 4, 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Radovani, P.; Vasili, D.; Xhelili, M.; Dervishi, J. Orbital Complications of Sinusitis. Balk. Med. J. 2013, 30, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study/Year | Study Type | Sample Size | Age Range | Ocular Manifestations (Prevalence) | Identified Risk Factors | Diagnostic Methods | Management Strategies | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chandler et al., 1970 [15] | Case series | 54 | 0–18 years | Orbital cellulitis (100%) | Not specified | Clinical exam | Antibiotics, Surgery | Full recovery (85%) |

| Younis et al., 2002 [16] | Retrospective review | 43 | 2–14 years | Subperiosteal abscess (100%) | Ethmoid sinusitis | CT scan | Surgery (100%), Antibiotics | Full recovery (100%) |

| Sobol et al., 2005 [17] | Retrospective review | 104 | 0–18 years | Preseptal cellulitis (83%), Orbital cellulitis (17%) | Age < 5 years, S. aureus | CT scan, Clinical exam | Antibiotics, Surgery (9%) | Full recovery (100%) |

| Siedek et al., 2008 [3] | Retrospective review | 262 | 0–16 years | Preseptal cellulitis (76%), Orbital cellulitis (24%) | Age < 5 years | CT scan, MRI | Antibiotics, Surgery (19%) | Full recovery (98%) |

| Eviatar et al., 2008 [5] | Retrospective review | 76 | 0–2 years | Preseptal cellulitis (100%) | Age < 2 years | CT scan | Conservative treatment | Full recovery (100%) |

| Rudloe et al., 2010 [11] | Retrospective cohort | 918 | 0–18 years | Preseptal cellulitis (97%), Orbital cellulitis (3%) | Age < 3 years | CT scan (selective) | Antibiotics, Surgery (1%) | Full recovery (99%) |

| Seltz et al., 2011 [18] | Retrospective review | 41 | 0–18 years | Orbital cellulitis (100%) | MRSA prevalence | CT scan, Culture | Antibiotics, Surgery (54%) | Full recovery (98%) |

| Wan et al., 2016 [4] | Systematic review | 1192 | 0–18 years | Preseptal/Orbital cellulitis (85%), Subperiosteal abscess (11%), Intracranial complications (3%) | Age, Prolonged symptoms | CT scan, MRI | Antibiotics, Surgery (variable) | Full recovery (97%) |

| Torretta et al., 2019 [19] | Systematic review | 2945 | 0–18 years | Preseptal cellulitis (72%), Orbital cellulitis (24%), Subperiosteal abscess (4%) | Age, Ethmoid sinusitis | CT scan, MRI | Antibiotics, Surgery (variable) | Full recovery (95%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maniaci, A.; Gagliano, C.; Lavalle, S.; van der Poel, N.; La Via, L.; Longo, A.; Russo, A.; Zeppieri, M. Ocular Manifestations of Pediatric Rhinosinusitis: A Comprehensive Review. Diseases 2024, 12, 239. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases12100239

Maniaci A, Gagliano C, Lavalle S, van der Poel N, La Via L, Longo A, Russo A, Zeppieri M. Ocular Manifestations of Pediatric Rhinosinusitis: A Comprehensive Review. Diseases. 2024; 12(10):239. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases12100239

Chicago/Turabian StyleManiaci, Antonino, Caterina Gagliano, Salvatore Lavalle, Nicolien van der Poel, Luigi La Via, Antonio Longo, Andrea Russo, and Marco Zeppieri. 2024. "Ocular Manifestations of Pediatric Rhinosinusitis: A Comprehensive Review" Diseases 12, no. 10: 239. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases12100239

APA StyleManiaci, A., Gagliano, C., Lavalle, S., van der Poel, N., La Via, L., Longo, A., Russo, A., & Zeppieri, M. (2024). Ocular Manifestations of Pediatric Rhinosinusitis: A Comprehensive Review. Diseases, 12(10), 239. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases12100239