Four-Features Evaluation of Text to Speech Systems for Three Social Robots

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Relevant TTS Systems in the Market

- Mbrola is an open source artificial voice generation system which allows, at a low level, a great degree of control over the synthesized speech. In this sense, the user can configure various parameters to get precise prosodic control [7].

- Loquendo TTS synthesizes a human-like voice in multiple languages. It became very popular on Internet platforms, like Youtube, since the community employed it to generate tutorials and parodies.

- Pico is a TTS system developed by SVOX that currently is installed by default on most Android devices (at least until the 4.2 version). Note that SVOX and Loquendo were acquired by Nuance in 2011.

- Nuance Real Speak is the flagship product, regarding speech synthesis system, of the Nuance Communications company. It allows generating voices in several languages and it is the official voice of the virtual assistant of Apple, Siri.

- Festival is a general multilingual speech synthesis system originally developed at the Centre for Speech Technology Research (University of Edinburgh). It is distributed under a free software license similar to BSD.

- Ivona: This is the TTS system developed by the Amazon company. It is widely used in Amazon devices, such as the Kindle electronic reader.

- Google: This is the voice system developed by Google and is used in its applications, web services, and in its virtual assistant ‘Google Now’. The generated voice is different in each language (supports over 80 languages and dialects).

- Microsoft: This is the voice system of the Microsoft company, and it is used in its services, applications, operative systems, and in its virtual assistant ‘Cortana’.

- AT&T: This is the system developed by the AT&T company. It generates speech in eight different languages, and it is used in its call centres.

- Verbio: This is the system developed by the Spanish company Verbio. It is mainly used by call-centre services of companies and public institutions.

The TTS Systems Used in Social Robots and Other Electronic Devices

2.2. Previous Comparative Studies of TTS Systems

2.3. Evaluated Features of the TTS Systems

- Adequacy: ‘is the speech adequate for use as a reading machine (in comparison with other media)?’

- Acceptability: ‘is the speech acceptable for use as a reading machine (when is not possible to use other media)?’

- Comprehensibility: ‘is the message easy to understand?’

- Intelligibility: ‘are the individual phonemes/sounds and words easy to recognize (and discriminate one from another)?’

- Choice of pronunciation: ‘is the pronunciation correct?’

- Precision of phonemes: ‘was the articulation of the phonemes/sounds precise?’

- Appropriateness of prosody: ‘was the prosody (music) of the utterance appropriate?’

- Naturalness of phonemes: ‘do the phonemes/sounds sound natural/human?’

- Naturalness of prosody: ‘does the prosody (music) sound natural/human?’

- Expressiveness: ‘was the emotion expressed well?’

- Appropriateness of register: ‘was the register appropriate?’

- Sound quality acceptance: related to the quality of the sound. This requires a yes or no answer.

- Listening effort: related to the effort required to understand the message.

- Comprehension problems: related to the difficulties to understand certain words.

- Articulation: related to the question about if the sounds were distinguishable.

- Pronunciation: related to the possible anomalies detected in pronunciation.

- Speaking rate: related to the average speed of delivery.

- Pleasantness: related to the pleasantness of the voice.

- Overall impression.

3. Experiment

3.1. The Compared Text-To-Speech Systems

- AT&T

- Google

- Ivona

- Microsoft

- Nuance

- Loquendo (v7.7)

- Espeak (v1.48)

- Pico (v2018).

3.2. The Social Robots

3.3. Procedure

- Intelligibility: ‘Can you clearly understand the voice of this robot?’

- Expressiveness: ‘How do you perceive this robot’s voice: monotonous or very expressive?’

- Artificiality: ‘Do you think that this is a robotic voice?’

- Suitability: ‘Do you think that this voice is suitable for this robot?’

3.4. Research Questions

- RQ1: are all TTS systems equally well understood?

- RQ2: do all TTS systems have the same expressiveness?

- RQ3: are all TTS systems equally perceived as robotic?

- RQ4: are all TTS systems equally suitable for each robot?

3.5. Participants

4. Results

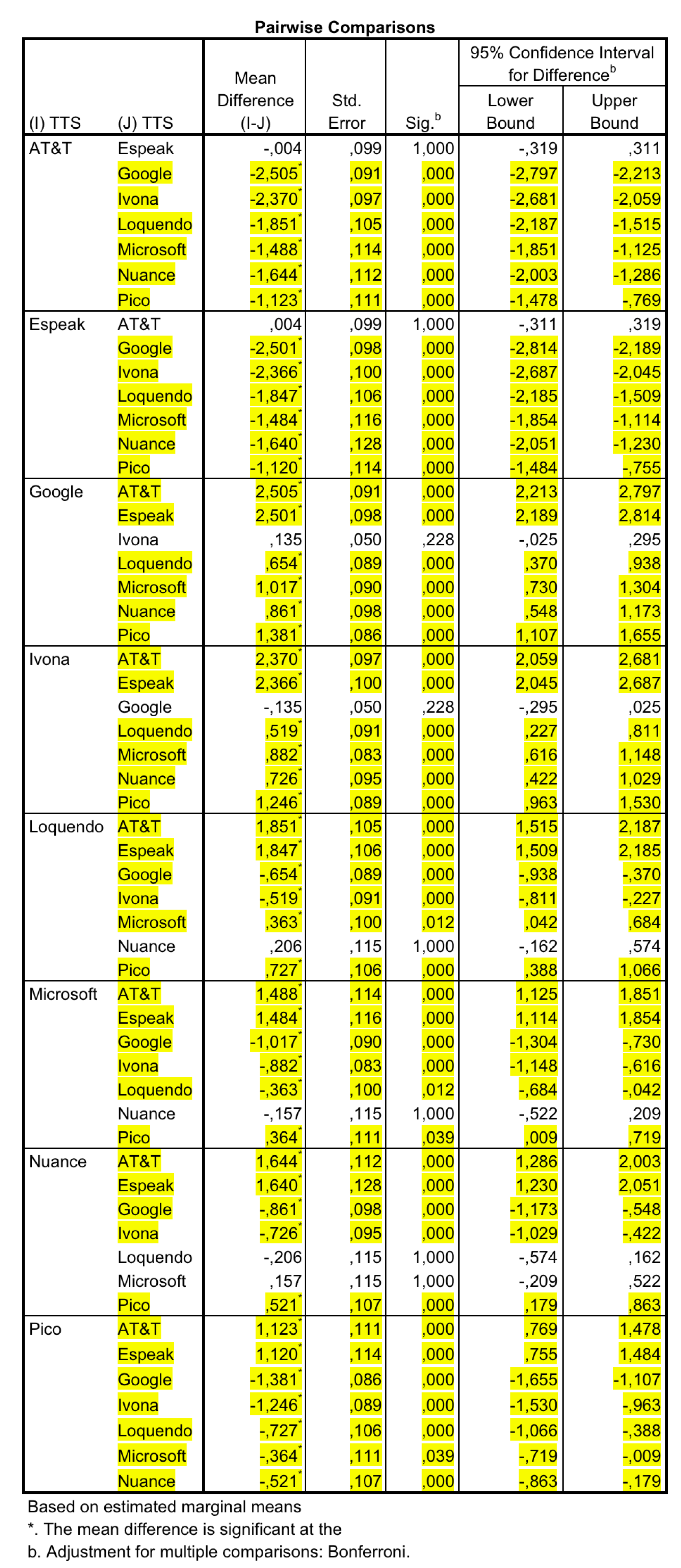

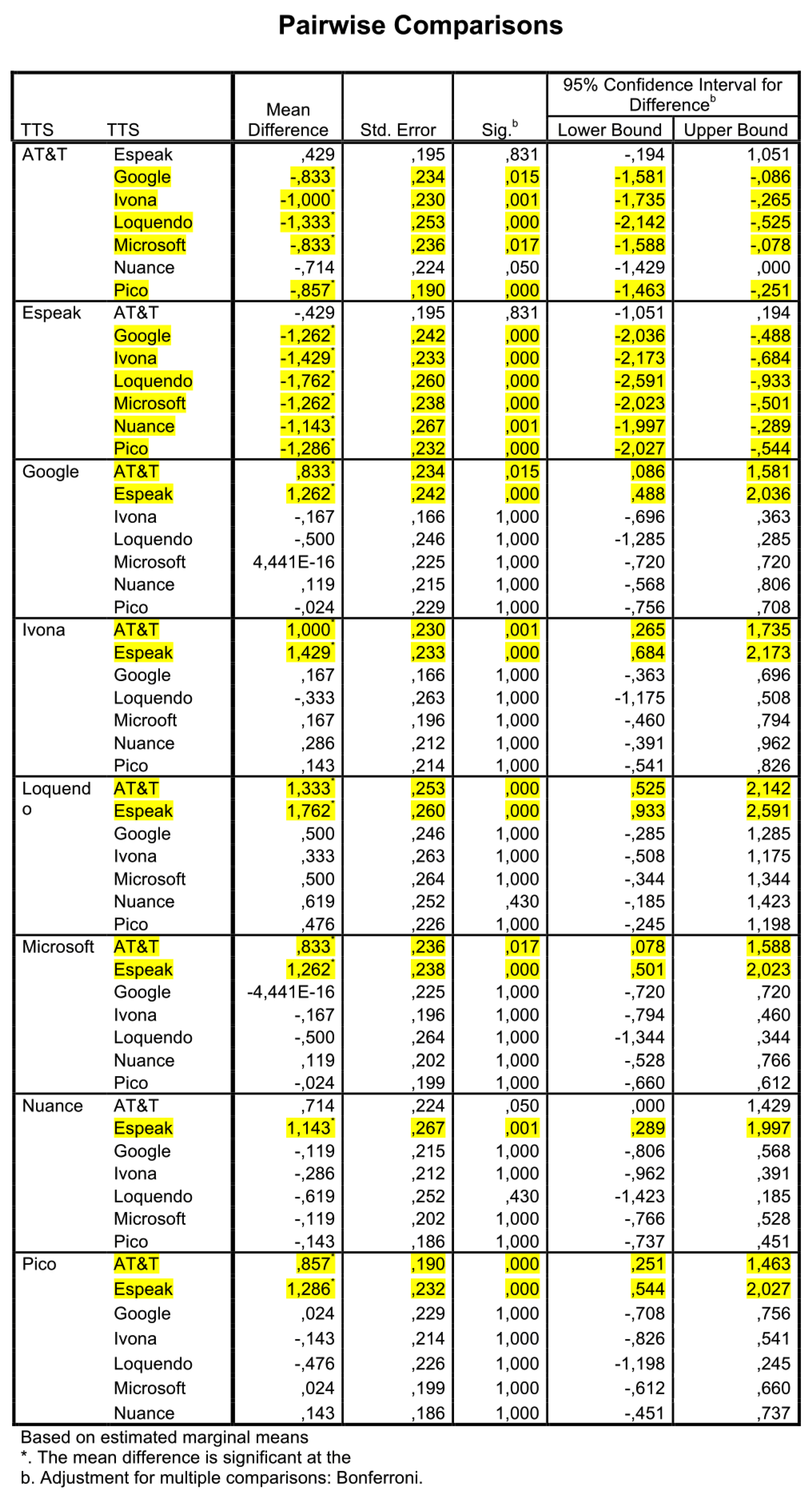

4.1. Intelligibility: Are All TTS Systems Equally Well Understood?

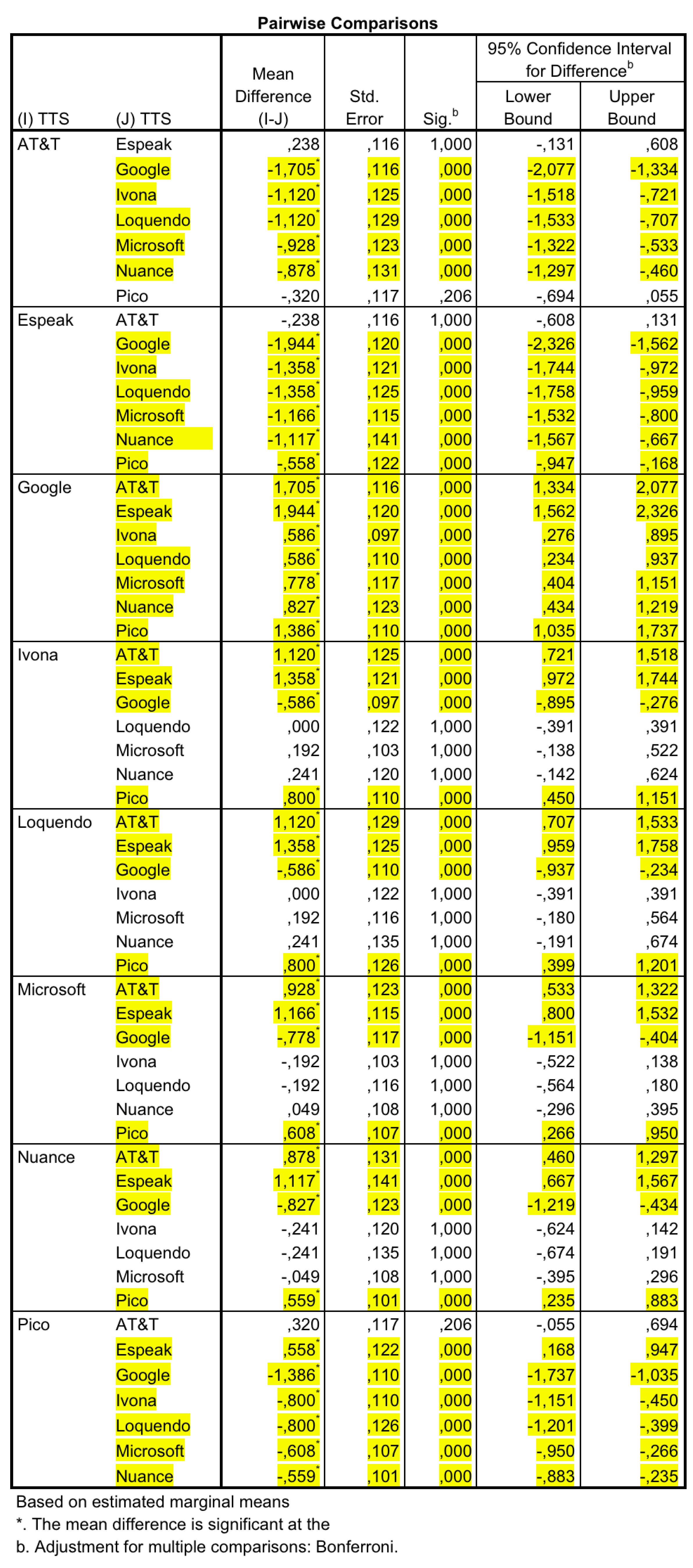

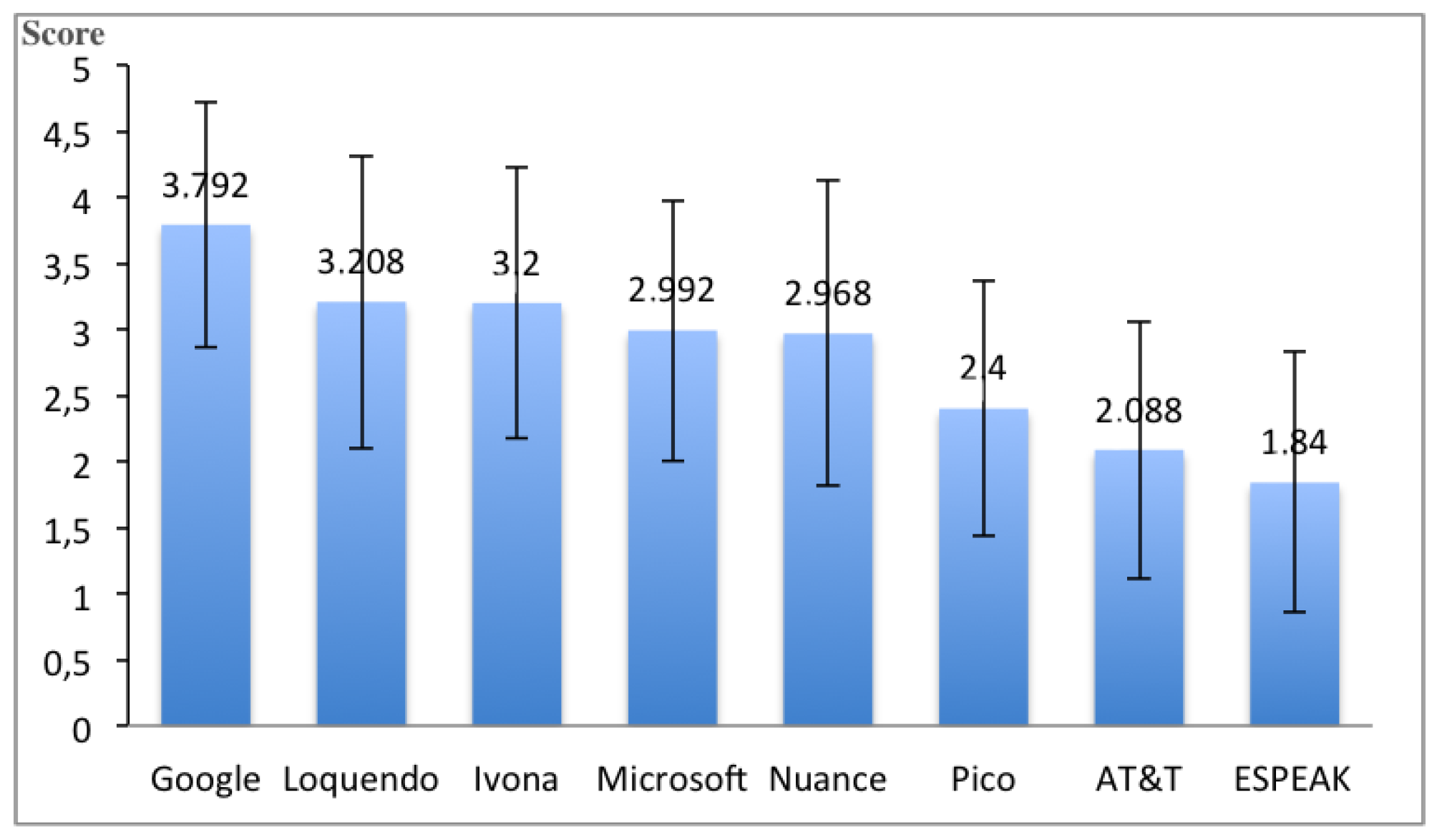

4.2. Expressiveness: Do All TTS Systems Have the Same Expressiveness?

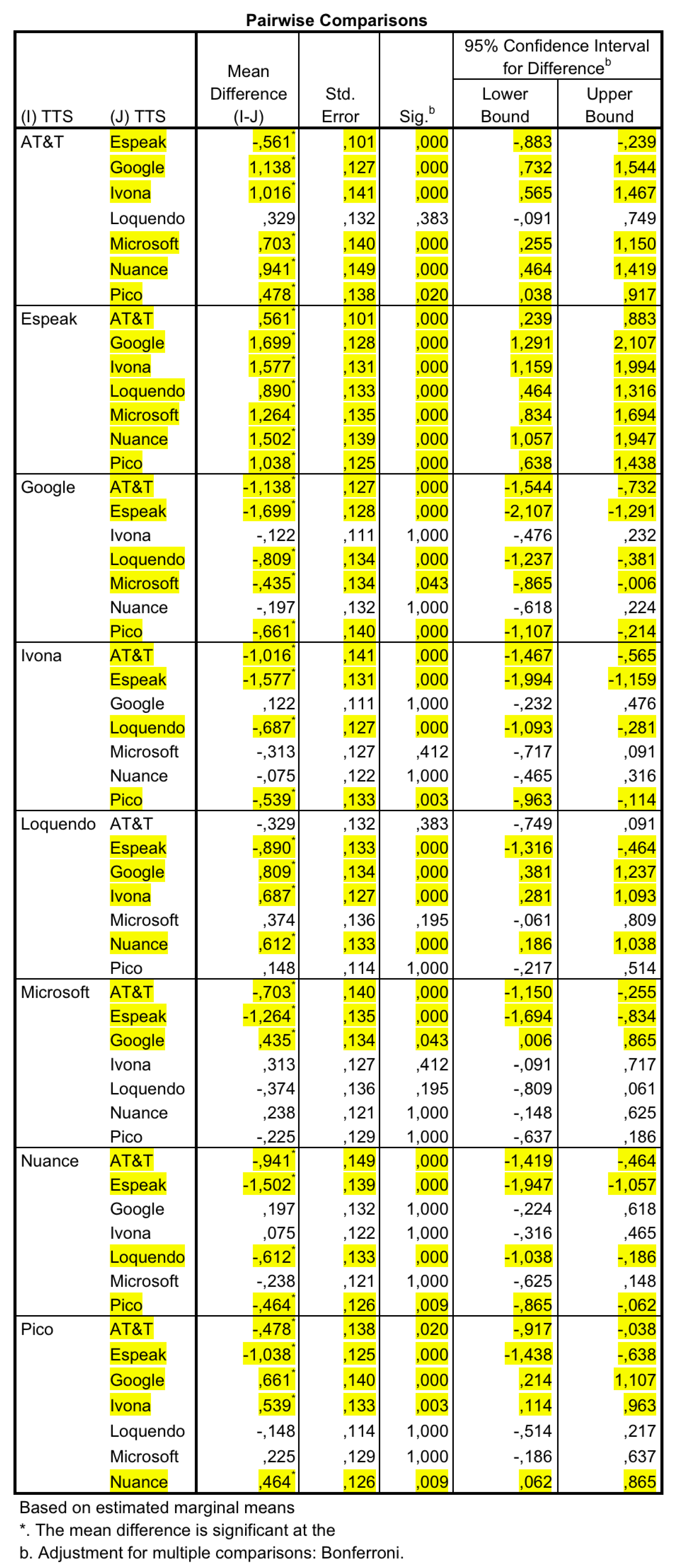

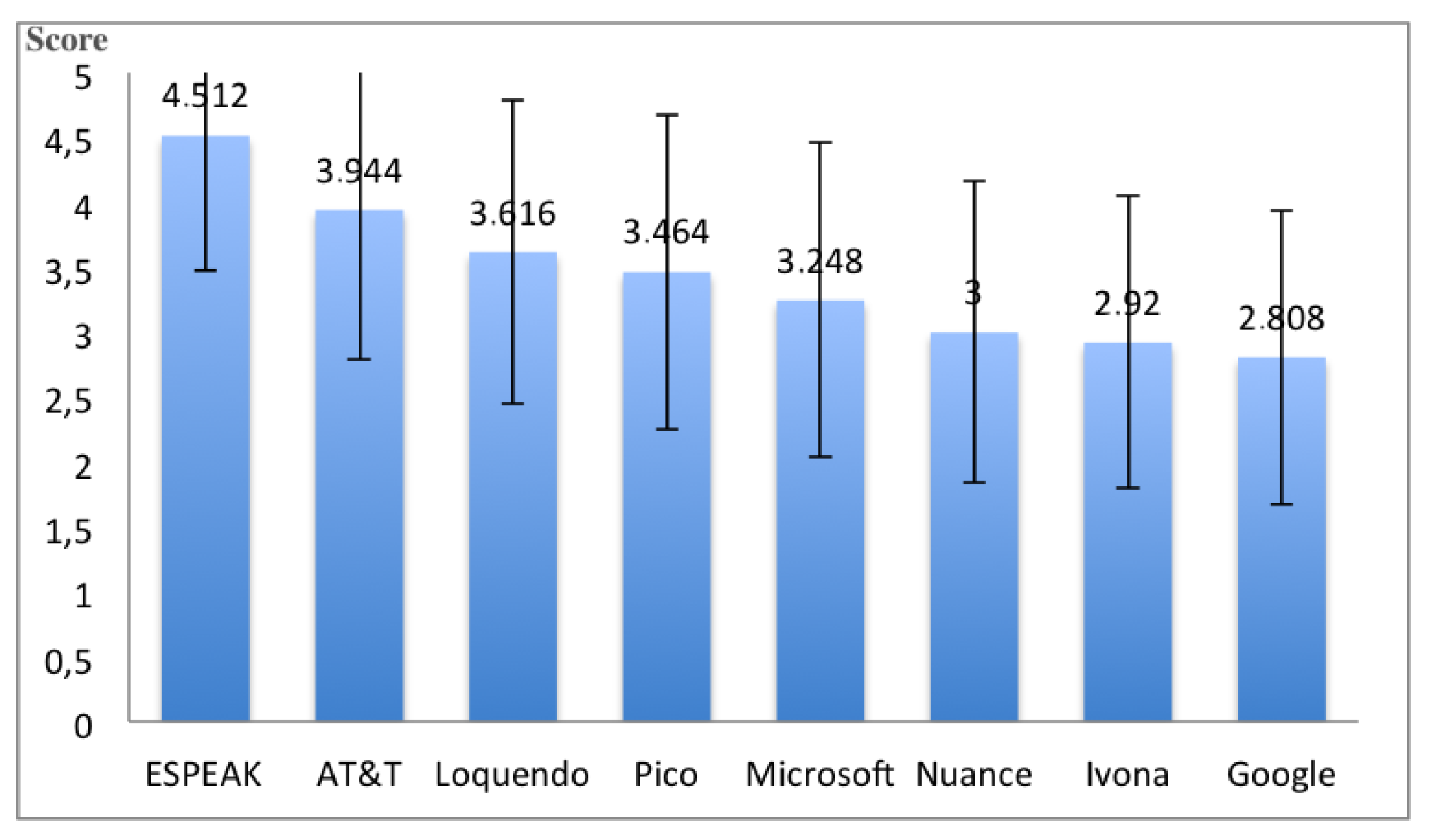

4.3. Artificiality: Are All TTS Systems Equally Perceived as Robotic?

4.4. Suitability: Are All TTS Systems Equally Suitable for Each Robot?

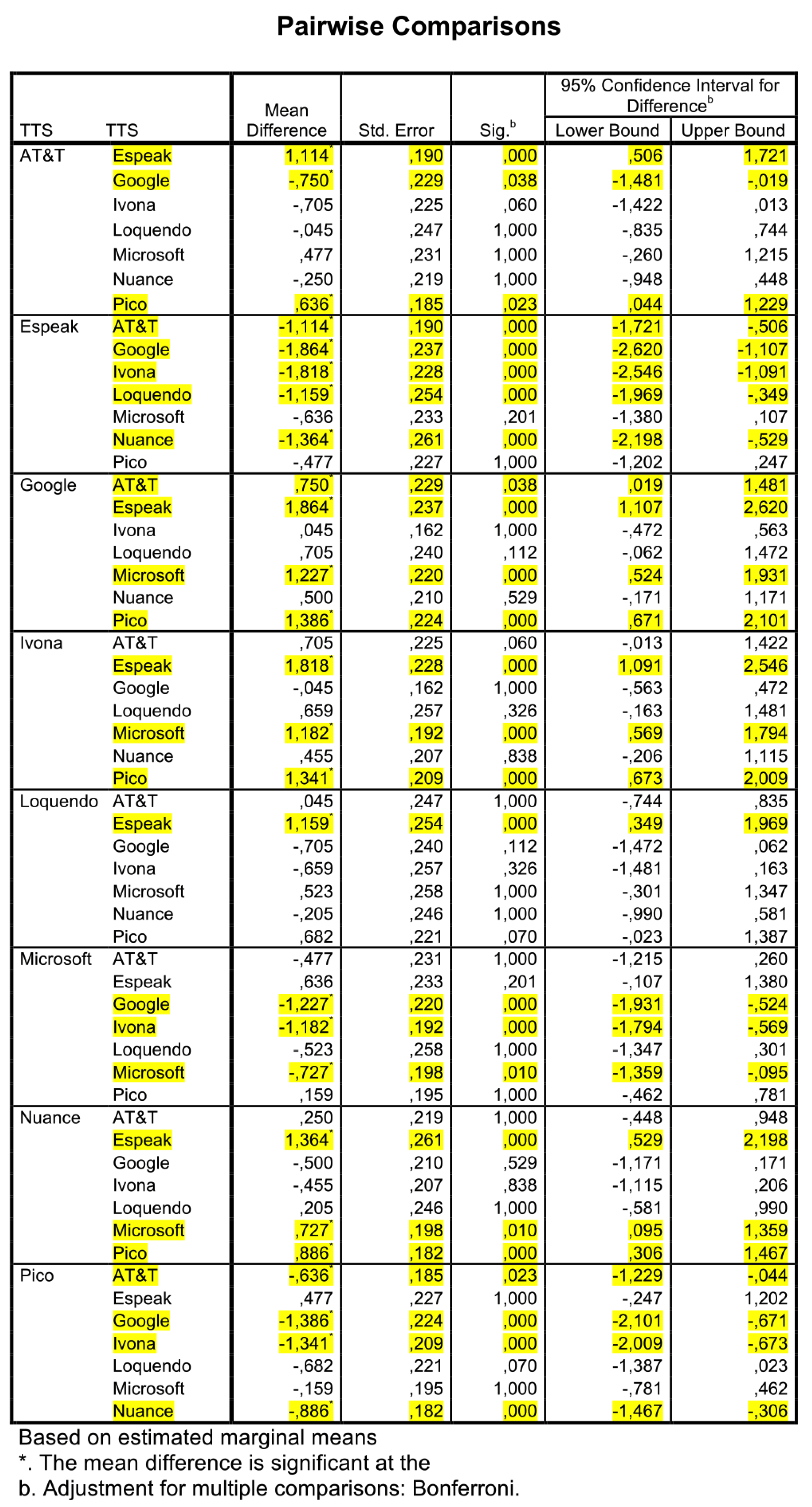

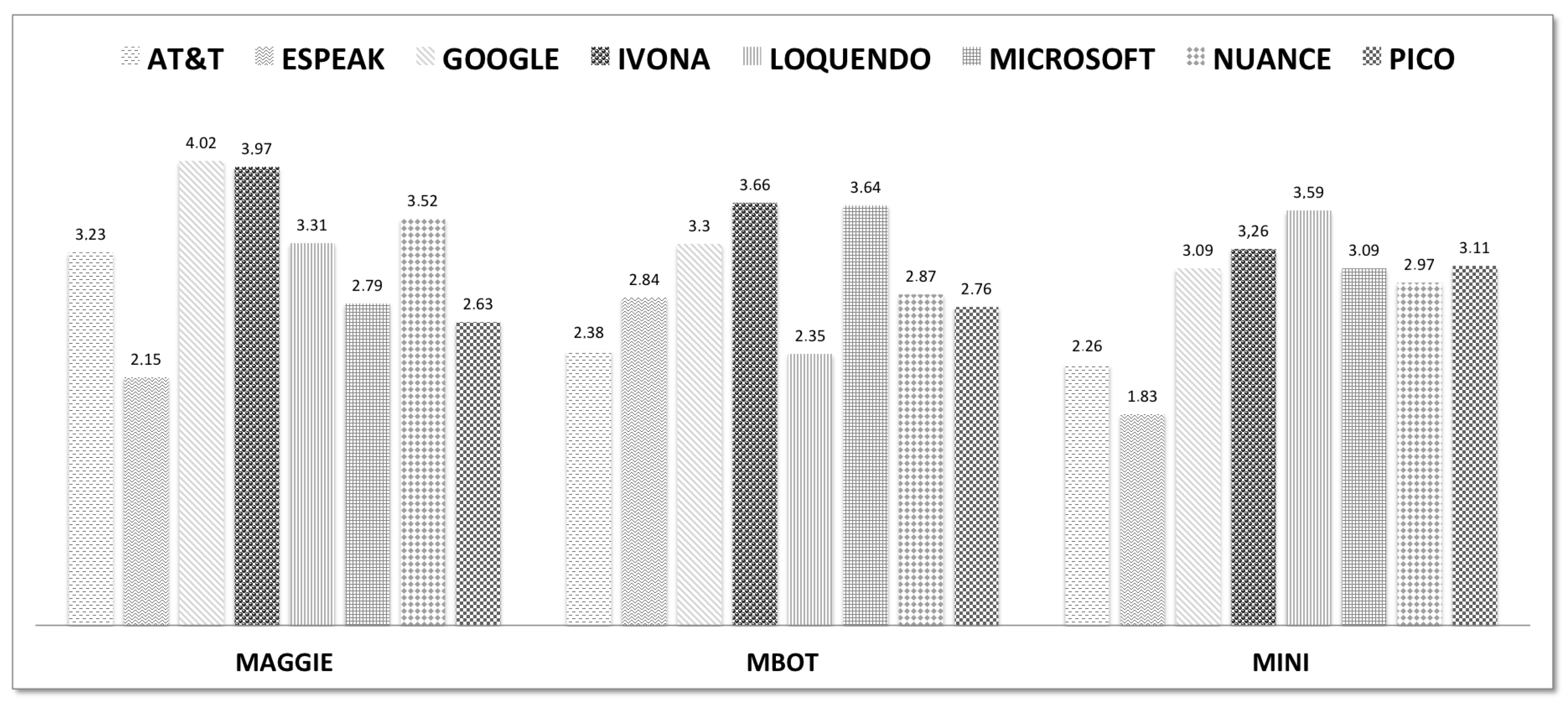

- RQ4.1: are all TTS systems equally suitable for Maggie?

- RQ4.2: are all TTS systems equally suitable for Mbot?

- RQ4.3: are all TTS systems equally suitable for Mini?

4.4.1. Maggie

4.4.2. Mbot

4.4.3. Mini

4.5. Correlations between the Four Features Analyzed

5. Discussion and Conclusions

- For our three social robots, the most suitable TTS systems overall are Google and Ivona. In fact, Ivona has been, in all cases, the second best rated (with no significant differences from the first and the third ones). Therefore, this TTS system can be a good selection for these robots.

- In relation to the less suitable TTS systems, it is interesting to note that, for Maggie and Mini, the worst evaluated system is Espeak (it is significantly different from the most suitable one ()). On the contrary, this TTS system is not perceived as the least suitable one for Mbot.One reason could be that Maggie and Mini have more physical similarities between them (Mini is a small version of Maggie) than with Mbot. Another reason could be related to gender issues. One aspect about the TTS systems that has not been considered until now is the gender of the synthesized voice. This characteristic may seem to be not very relevant at first, but, considering that we give names to the robots, which people can associate with the feminine or masculine gender, this feature must be considered in order to evaluate the suitability of a particular voice with a specific robot. All TTS systems have been tested using a feminine voice except for Espeak, which uses a masculine voice. According to our own experience, people tend to refer to Maggie and Mini as feminine, and to Mbot as masculine. Therefore, it is logical that this TTS system is perceived as less suitable for Maggie and Mini, and not so unsuitable for Mbot.

- In general, the TTS systems that are evaluated as the most ‘robotic’ ones (Espeak, AT&T, and Pico) are also considered as less suitable for the robots. This seems to be a contradiction, but, it must be noted that these TTS systems are also the ones that were evaluated as the less clearly understood by the participants (intelligibility).

Limitations and Lessons Learned

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Van Bezooijen, R.; Pols, L.C. Evaluating text-to-speech systems: Some methodological aspects. Speech Commun. 1990, 9, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handley, Z. Is text-to-speech synthesis ready for use in computer-assisted language learning? Speech Commun. 2009, 51, 906–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Malley, M. Text-to-speech conversion technology. Computer 1990, 23, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klatt, D.H. Review of text-to-speech conversion for English. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1987, 82, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappas, C. Top 10 Text to Speech (TTS) Software for eLearning. 2019. Available online: https://elearningindustry.com/top-10-text-to-speech-tts-software-elearning (accessed on 12 December 2019).

- Comparison of Speech Synthesizers. 2018. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Comparison_of_speech_synthesizers (accessed on 12 December 2019).

- Dutoit, T.; Pagel, V.; Pierret, N.; Bataille, F.; Van der Vrecken, O. The MBROLA project: Towards a set of high quality speech synthesizers free of use for non commercial purposes. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Spoken Language Processing, ICSLP’96, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 3–6 October 1996; Volume 3, pp. 1393–1396. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, H.; de Perre, G.V.; Simut, R. Enhancing My Keepon robot: A simple and low-cost solution for robot platform in Human-Robot Interaction studies. In Proceedings of the 23rd IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (ROMAN), Edinburgh, UK, 25–29 August 2014; pp. 555–560. [Google Scholar]

- Wada, K.; Ikeda, Y.; Inoue, K.; Uehara, R. Development and preliminary evaluation of a caregiver’s manual for robot therapy using the therapeutic seal robot Paro. In Proceedings of the 19th International Symposium in Robot and Human Interactive Communication, Viareggio, Italy, 13–15 September 2010; pp. 533–538. [Google Scholar]

- Fujita, M. On activating human communications with pet-type robot AIBO. Proc. IEEE 2004, 92, 1804–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsuddin, S.; Ismail, L.I.; Yussof, H.; Zahari, N.I.; Bahari, S.; Hafizan, H.; Jaffar, A. Humanoid robot NAO: Review of control and motion exploration. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Conference on Control System, Computing and Engineering, Penang, Malaysia, 25–27 November 2011; pp. 511–516. [Google Scholar]

- Lafaye, J.; Gouaillier, D.; Wieber, P.B. Linear model predictive control of the locomotion of Pepper, a humanoid robot with omnidirectional wheels. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE-RAS International Conference on Humanoid Robots, Madrid, Spain, 18–20 November 2014; pp. 336–341. [Google Scholar]

- Tsagarakis, N.; Metta, G.; Sandini, G. iCub: The design and realization of an open humanoid platform for cognitive and neuroscience research. Adv. Robot. 2007, 21, 1151–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metta, G.; Sandini, G.; Vernon, D. The iCub humanoid robot: An open platform for research in embodied cognition. In Proceedings of the PerMIS ’08, Workshop on Performance Metrics for Intelligent Systems, Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 19–21 August 2008; pp. 50–56. [Google Scholar]

- Group, A. Acapela. 2019. Available online: http://www.acapela-group.com (accessed on 12 December 2019).

- Kenmochi, H.; Ohshita, H. VOCALOID-commercial singing synthesizer based on sample concatenation. In Proceedings of the INTERSPEECH 2007, 8th Annual Conference of the International Speech Communication Association, Antwerp, Belgium, 27–31 August 2007; pp. 4009–4010. [Google Scholar]

- Kenmochi, H. VOCALOID and Hatsune Miku phenomenon in Japan. In Proceedings of the Interdisciplinary Workshop on Singing Voice, Tokyo, Japan, 1–2 October 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tachibana, M.; Nakaoka, S.; Kenmochi, H. A singing robot realized by a collaboration of VOCALOID and Cybernetic Human HRP-4C. In Proceedings of the Interdisciplinary Workshop on Singing Voice (InterSinging 2010), Tokyo, Japan, 1–2 October 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Apple. Siri. 2019. Available online: http://www.apple.com/ios/siri (accessed on 12 December 2019).

- Google. Google Now. 2019. Available online: https://www.google.com/landing/now (accessed on 12 December 2019).

- Amazon. Kindle. 2019. Available online: https://kindle.amazon.com (accessed on 12 December 2019).

- Corporation, M. Cortana. 2019. Available online: http://windows.microsoft.com/es-es/windows-10/getstarted-what-is-cortana (accessed on 12 December 2019).

- Roehling, S.; MacDonald, B.; Watson, C. Towards expressive speech synthesis in english on a robotic platform. In Proceedings of the Australasian International Conference on Speech Science and Technology, Auckland, New Zealand, 6–8 December 2006; pp. 130–135. [Google Scholar]

- Bakhsh, N.K.; Alshomrani, S.; Khan, I. A comparative study of Arabic text-to-speech synthesis systems. Int. J. Inf. Eng. Electron. Bus. 2014, 6, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shruthi, G.; Kumar, P. Comparative study of text to speech system for indian language. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Inf. Technol. 2012, 1, 199–209. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, A.; Nusbaum, H. Evaluating the quality of synthetic speech. In Human Factors and Voice Interactive Systems; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1999; pp. 63–97. [Google Scholar]

- Handley, Z.; Hamel, M. Establishing a methodology for benchmarking speech synthesis for computer-assisted language learning (CALL). Lang. Learn. Technol. 2005, 9, 99–120. [Google Scholar]

- ITU-T. Transmission Quality Subjective Opinion Tests. A Method for Subjective Performance Assessment of the Quality of Speech Voice Output Devices. Available online: https://www.itu.int/rec/dologin_pub.asp?lang=e&id=T-REC-P.85-199406-I!!PDF-E&type=items (accessed on 12 December 2019).

- MOS Scale. 2019. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mean_opinion_score (accessed on 12 December 2019).

- Viswanathan, M. Measuring speech quality for text-to-speech systems: Development and assessment of a modified mean opinion score (MOS) scale. Comput. Speech Lang. 2005, 19, 55–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, S. Measuring a decade of progress in text-to-speech. Loquens 2014, 1, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Martin, F. Sistema de Interacción Humano-Robot Basado en Diálogos Multimodales y Adaptables. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso-Martín, F.; Castro-González, A.; Luengo, F.; Salichs, M. Augmented Robotics Dialog System for Enhancing Human–Robot Interaction. Sensors 2015, 15, 15799–15829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Pacheco, V.; Ramey, A.; Alonso-Martin, F.; Castro-Gonzalez, A.; Salichs, M.A. Maggie: A Social Robot as a Gaming Platform. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2011, 3, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salichs, M.; Barber, R.; Khamis, A.; Malfaz, M.; Gorostiza, J.; Pacheco, R.; Rivas, R.; Corrales, A.; Delgado, E.; Garcia, D. Maggie: A Robotic Platform for Human-Robot Social Interaction. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE Conference on Robotics, Automation and Mechatronics, Bangkok, Thailand, 1–3 June 2006; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Castro-González, Á.; Castillo, J.C.; Alonso-Martín, F.; Olortegui-Ortega, O.V.; González-Pacheco, V.; Malfaz, M.; Salichs, M.A. The Effects of an Impolite vs. a Polite Robot Playing Rock-Paper-Scissors. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Social Robotics, Kansas City, MO, USA, 1–3 November 2016; pp. 306–316. [Google Scholar]

- González-Pacheco, V.; Castro-González, Á.; Malfaz, M.; Salichs, M.A. Human-Robot Interaction in the MOnarCH project. In Proceedings of the 13th Robocity2030 Workshop, Madrid, Spain, 11 December 2015; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Monarch European Project. 2019. Available online: http://monarch-fp7.eu (accessed on 12 December 2019).

- Google. Google Forms. 2019. Available online: https://www.google.es/intl/es/forms/about (accessed on 12 December 2019).

- IBM. SPSS. 2019. Available online: http://www-01.ibm.com/software/es/analytics/spss (accessed on 12 December 2019).

| Maggie | M | SD | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| AT&T | 3.27 | 1.21 | 44 |

| Espeak | 2.16 | 1.16 | 44 |

| 4.02 | 0.90 | 44 | |

| Ivona | 3.98 | 0.85 | 44 |

| Loquendo | 3.32 | 1.23 | 44 |

| Microsoft | 2.79 | 1.25 | 44 |

| Nuance | 3.52 | 0.99 | 44 |

| Pico | 2.64 | 0.99 | 44 |

| Mbot | M | SD | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| AT&T | 2.38 | 1.18 | 39 |

| Espeak | 2.85 | 1.29 | 39 |

| 3.31 | 1.28 | 39 | |

| Ivona | 3.67 | 1.22 | 39 |

| Loquendo | 2.36 | 1.20 | 39 |

| Microsoft | 3.64 | 0.96 | 39 |

| Nuance | 2.87 | 1.13 | 39 |

| Pico | 2.77 | 1.04 | 39 |

| Mini | M | SD | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| AT&T | 2.26 | 0.96 | 42 |

| Espeak | 1.83 | 1.03 | 42 |

| 3.09 | 1.12 | 42 | |

| Ivona | 3.26 | 1.23 | 42 |

| Loquendo | 3.59 | 1.31 | 42 |

| Microsoft | 3.09 | 1.26 | 42 |

| Nuance | 2.98 | 1.35 | 42 |

| Pico | 3.12 | 1.23 | 42 |

| Measures | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Intelligibility | ||||

| (2) Artificiality | −0.301 | |||

| (3) Suitability | 0.476 | −0.225 | ||

| (4) Expressiveness | 0.548 | −0.358 | 0.540 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alonso Martin, F.; Malfaz, M.; Castro-González, Á.; Castillo, J.C.; Salichs, M.Á. Four-Features Evaluation of Text to Speech Systems for Three Social Robots. Electronics 2020, 9, 267. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics9020267

Alonso Martin F, Malfaz M, Castro-González Á, Castillo JC, Salichs MÁ. Four-Features Evaluation of Text to Speech Systems for Three Social Robots. Electronics. 2020; 9(2):267. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics9020267

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlonso Martin, Fernando, María Malfaz, Álvaro Castro-González, José Carlos Castillo, and Miguel Ángel Salichs. 2020. "Four-Features Evaluation of Text to Speech Systems for Three Social Robots" Electronics 9, no. 2: 267. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics9020267

APA StyleAlonso Martin, F., Malfaz, M., Castro-González, Á., Castillo, J. C., & Salichs, M. Á. (2020). Four-Features Evaluation of Text to Speech Systems for Three Social Robots. Electronics, 9(2), 267. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics9020267