A Cost-Efficient Software Based Router and Traffic Generator for Simulation and Testing of IP Network

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Related Research on Software-Based Router

2.2. Related Research on Network Simulator and Software Traffic Generators

- stochastic generation,

- replication of production network traffic,

- using list of instructions (communication scenario) for applications in the tested network.

- Application-level traffic generators: they emulate the behaviour of specific network applications in terms of the traffic they produce.

- Flow-level traffic generators: they are used when the replication of a realistic traffic is requested only at the flow level (e.g., number of packets and bytes transferred, flow duration). For example, Bit-Twist [28] is representative of this group.

- Packet-level traffic generators: with this term we refer to generators based on packet’s Inter departure time (IDT) and packet size (PS). The size of each packet sent, as well as the time elapsed between subsequent packets, are chosen by the user, typically by setting a statistical distribution for both variables. Most current packet generators belong to this group.

2.3. Related Research on Problems of Model Adequacy Assessment and Experimental Investigations of Infocommunications System

- -

- Conducting a meaningful analysis of the system under study and the specific conditions of its operation;

- -

- Building a simulation model of the system functioning process, which should reflect all those events in the information-computing process, which cause the change of measured parameters;

- -

- Development of measurement algorithms for selected parameters of the system functioning process on the basis of simulation model;

- -

- Performance of measurement algorithms in the system under study with the help of appropriate hardware and software measuring instruments.

3. Development of Software-Based Router and Traffic Generator

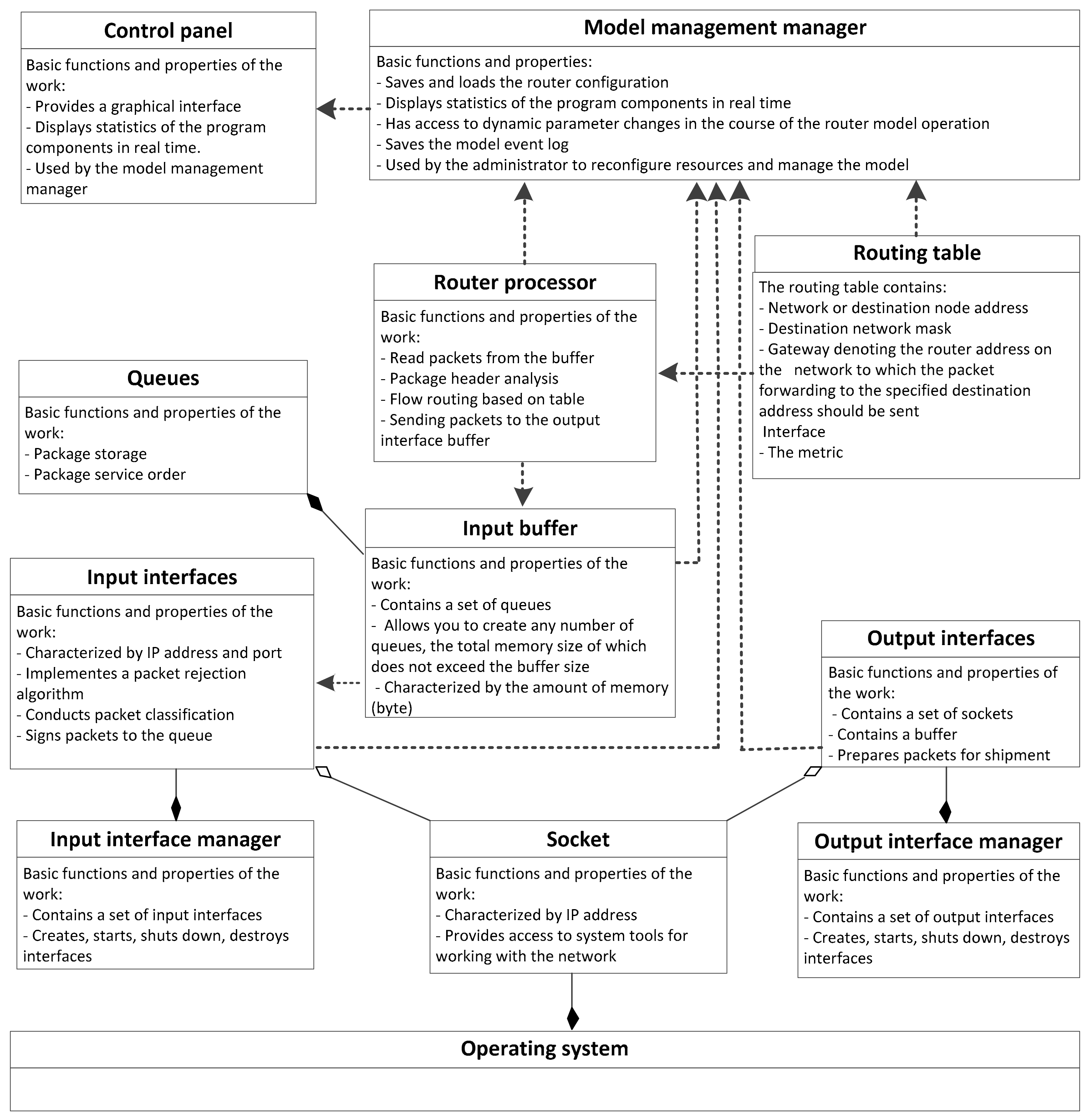

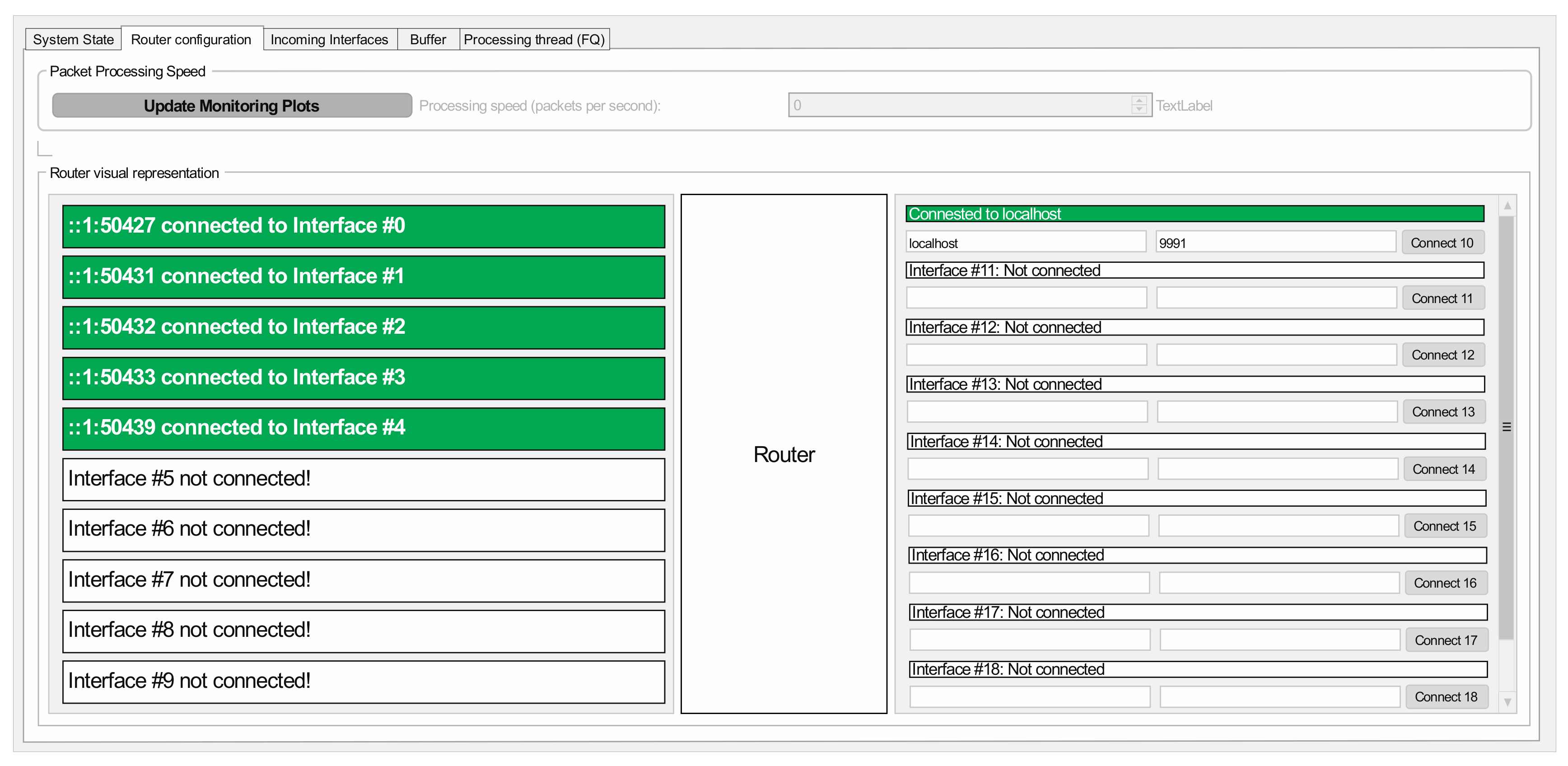

3.1. Development of Software-Based Router

- -

- Each component of the model is implemented in the form of a separate application and has its own IP-address and port, which allows you to select and connect components depending on the specific conditions;

- -

- The simulation model of the router can be as close as possible to the specific model of the manufacturer;

- -

- Distribution of components of the data network model is possible both on one and on several computers (servers) for the purpose of maximum approximation to real conditions and modelling networks with an unlimited number of nodes, not limiting the resources of one computer.

- (1)

- Aggregated multiservice traffic arrives at the ports of incoming interfaces.

- (2)

- Packets of streams arrive in the input queue

- (3)

- The processor of the router on the basis of the classifier, taking into account the discipline of queuing, selects the packet and analyzes its header type of service (ToS), differentiated services code point(DSCP);

- (4)

- The processor which realizes the report of routing, defines a direction for message transfer and supports an urgency of tables of routing by an exchange of service packages with other knots (at construction of a network from several program routers)

- (5)

- After processing the packet header and selecting the output interface port, the packet is queued in the output channel waiting list.

- (6)

- The next step is to transfer the packets to another network device defined by the routing protocol.

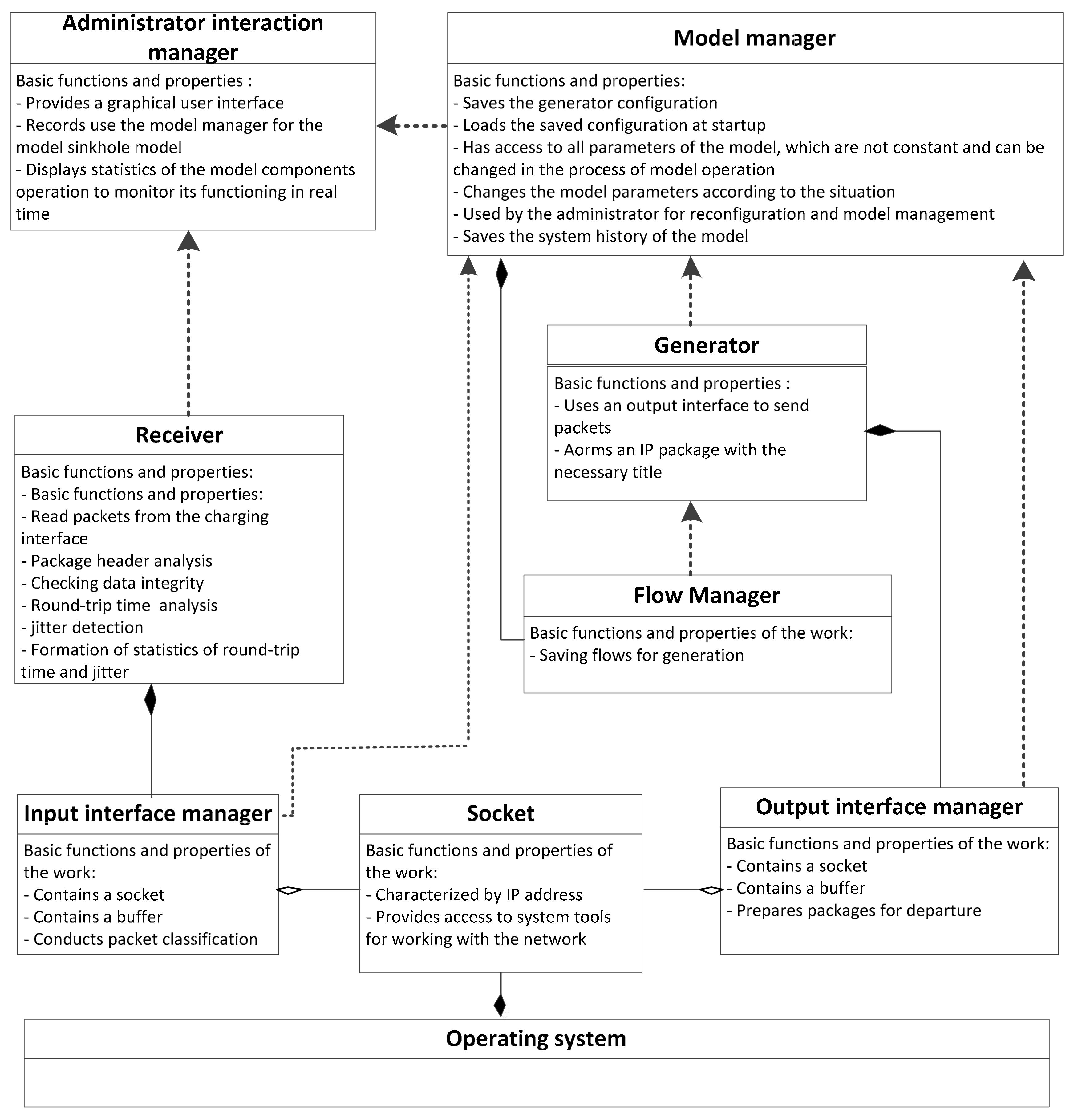

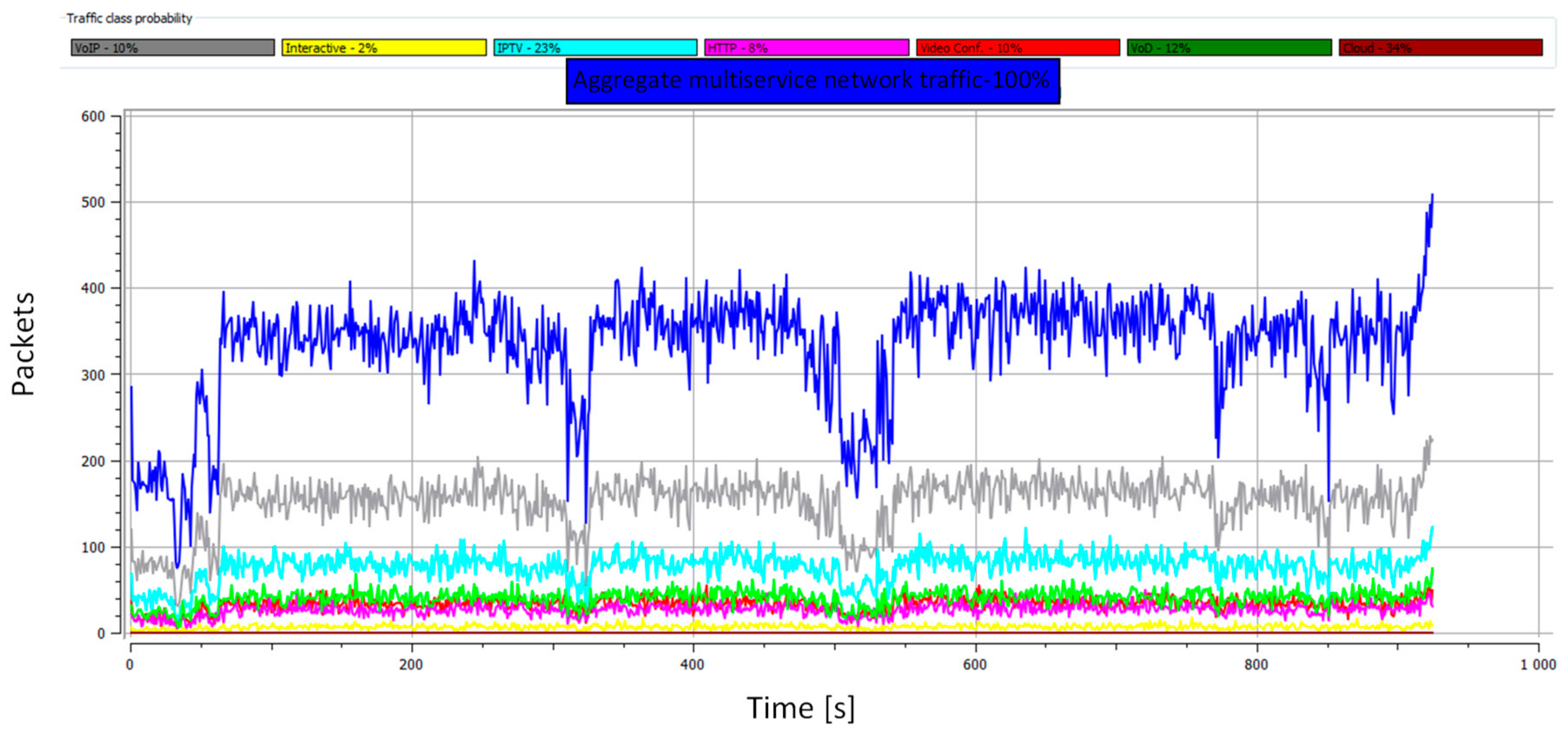

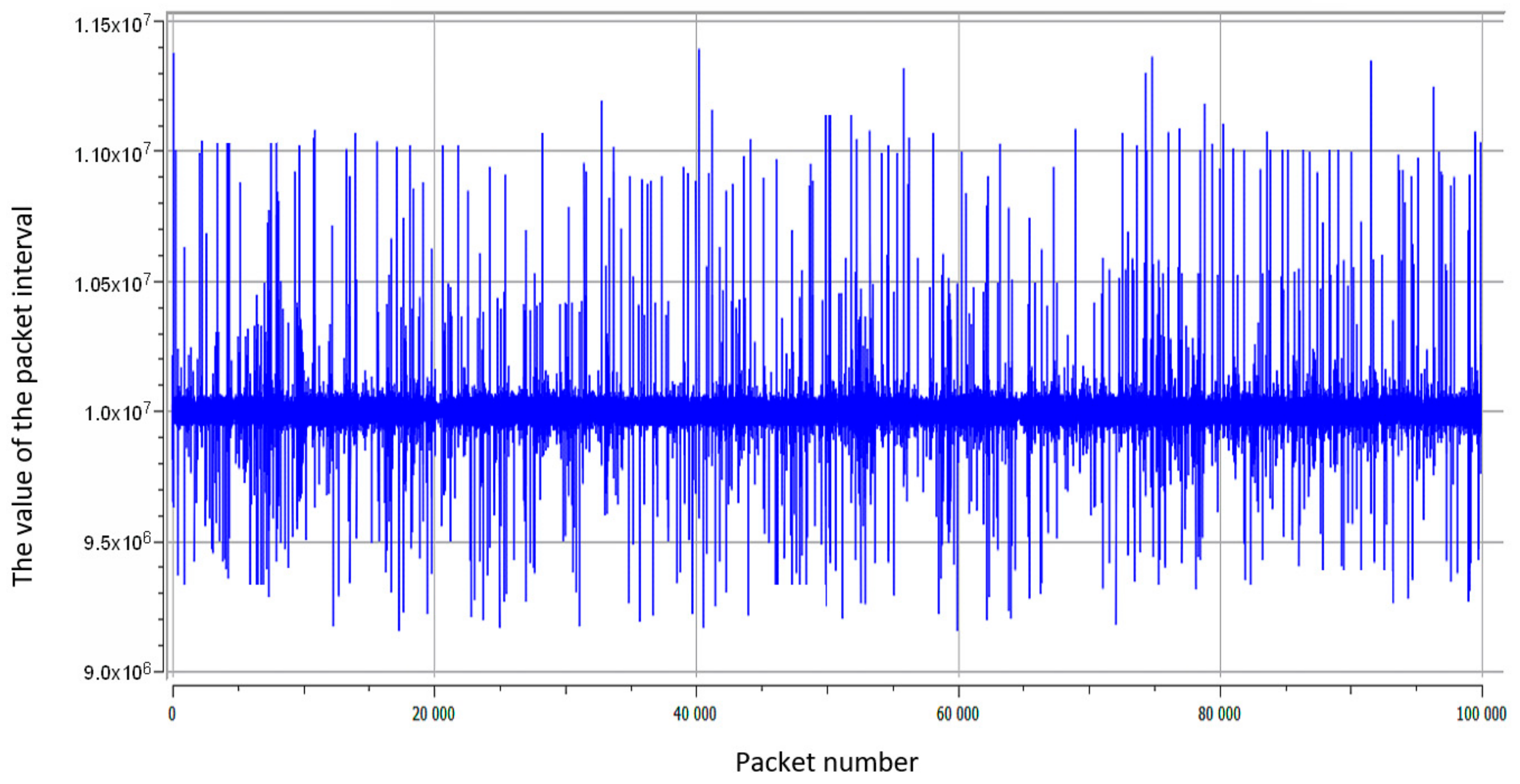

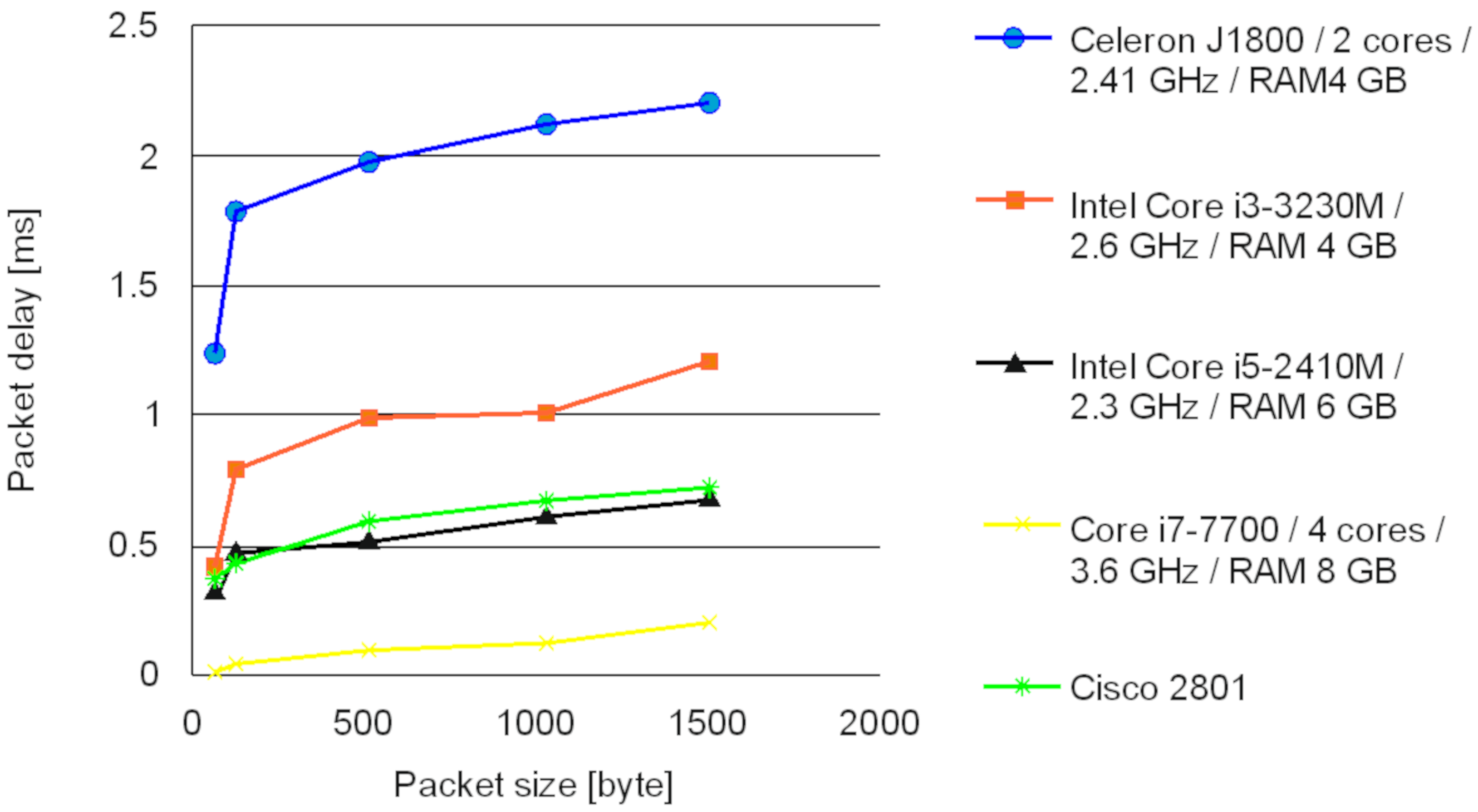

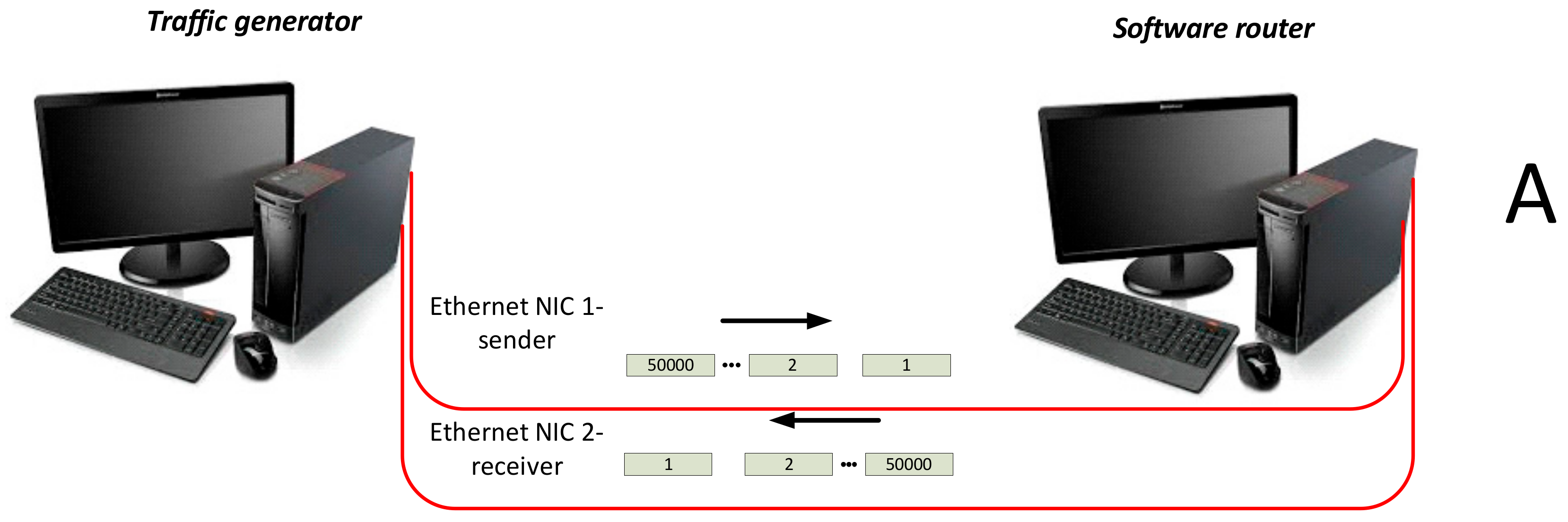

3.2. Performance Analysis of The Software-Based Router Using the Designed Network Traffic Generator

4. Results and Discussions

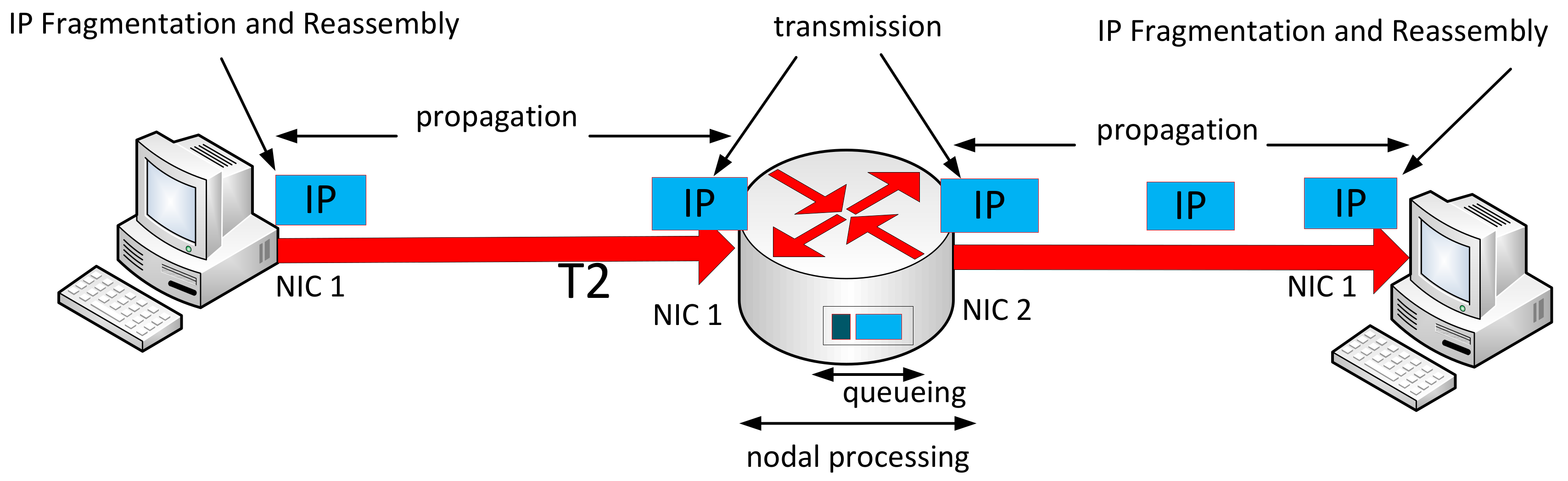

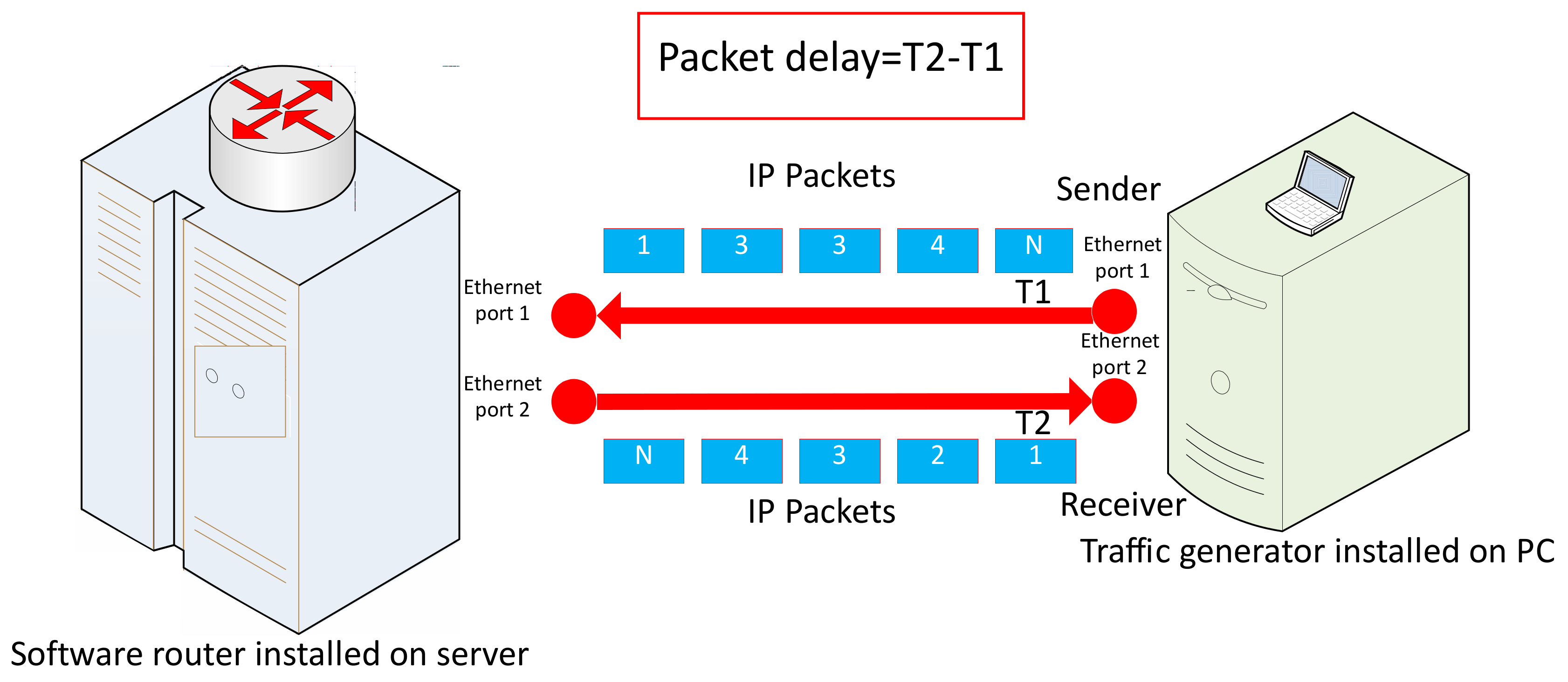

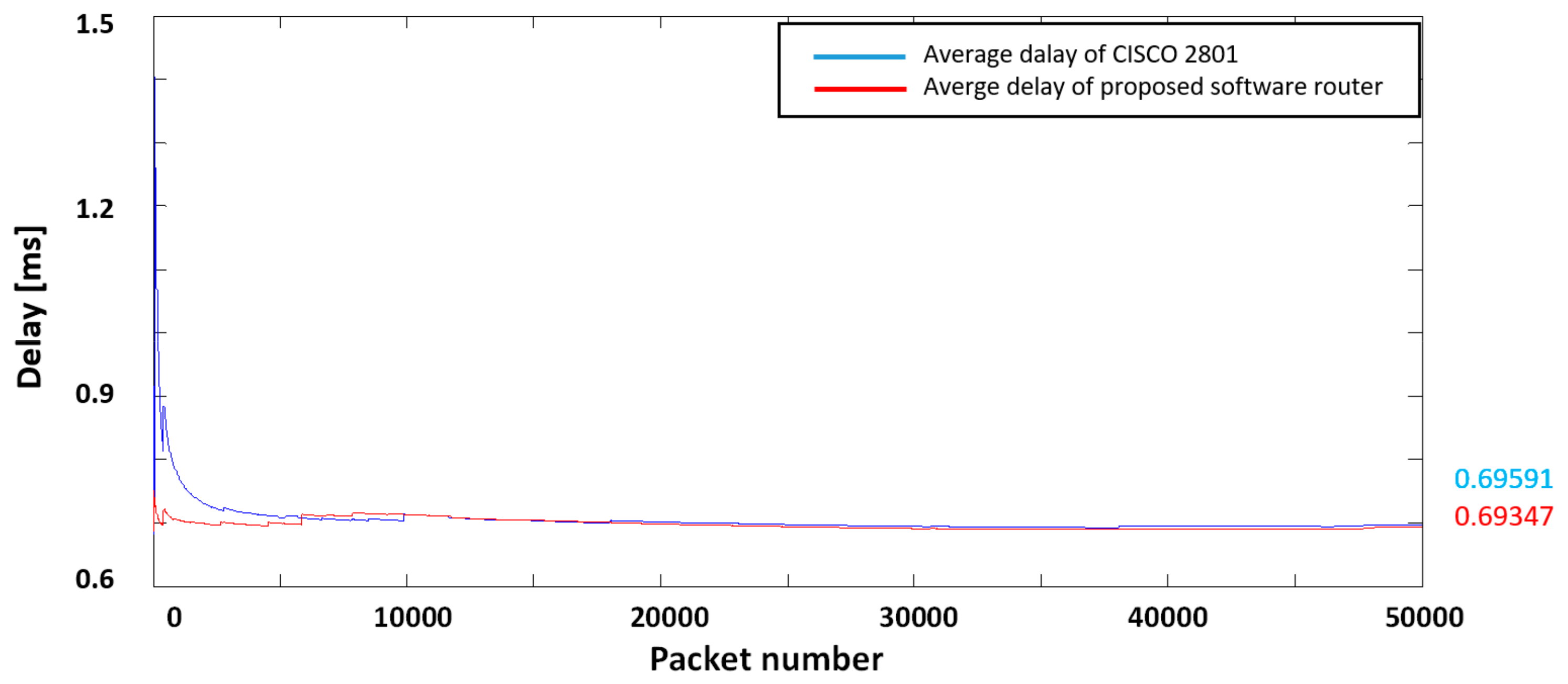

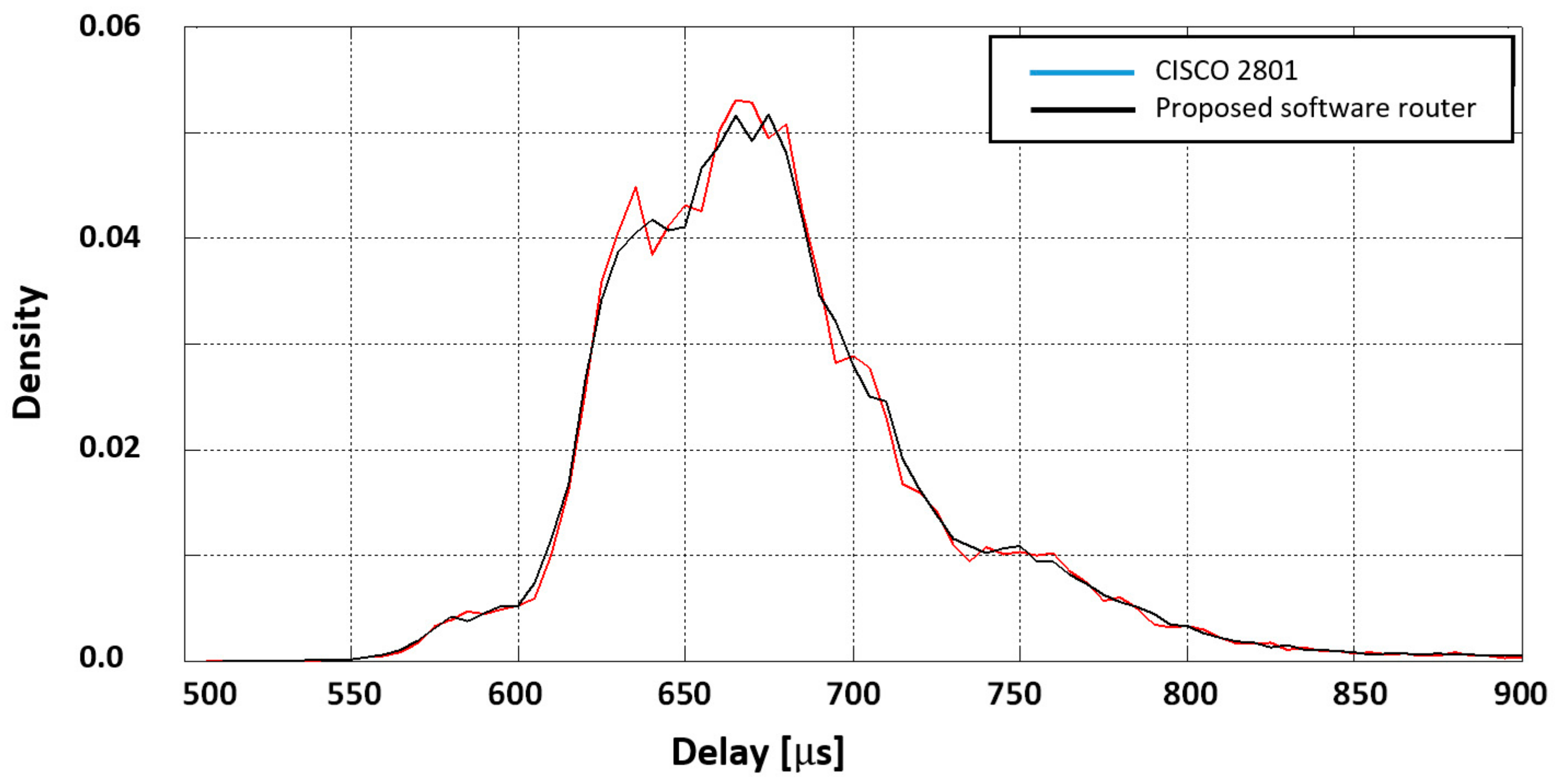

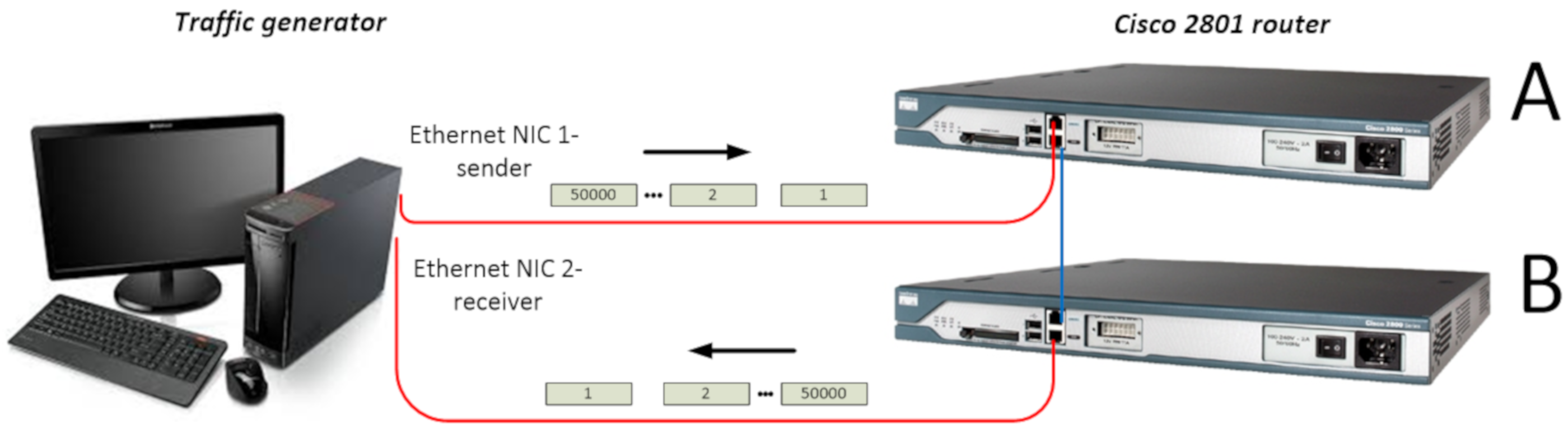

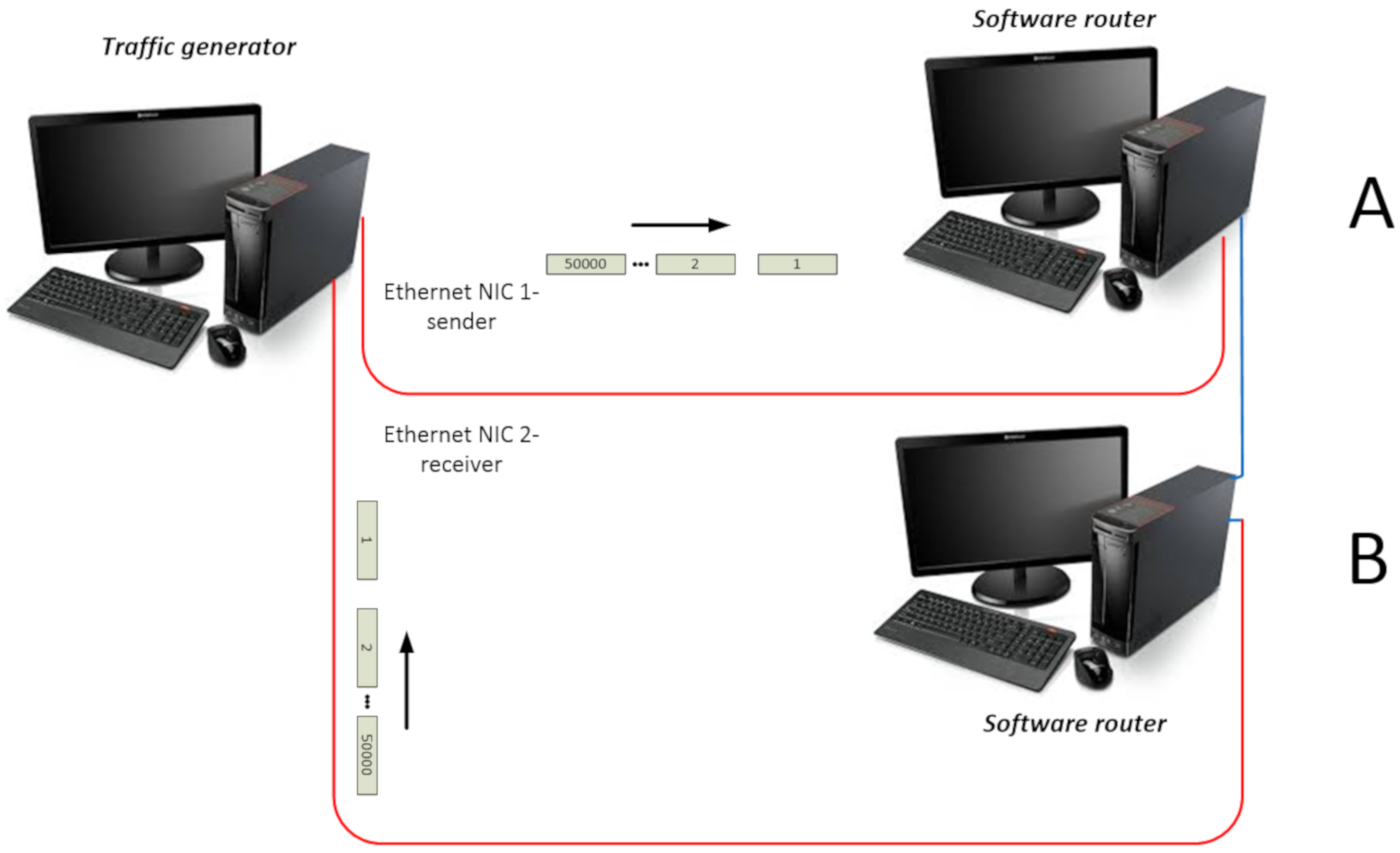

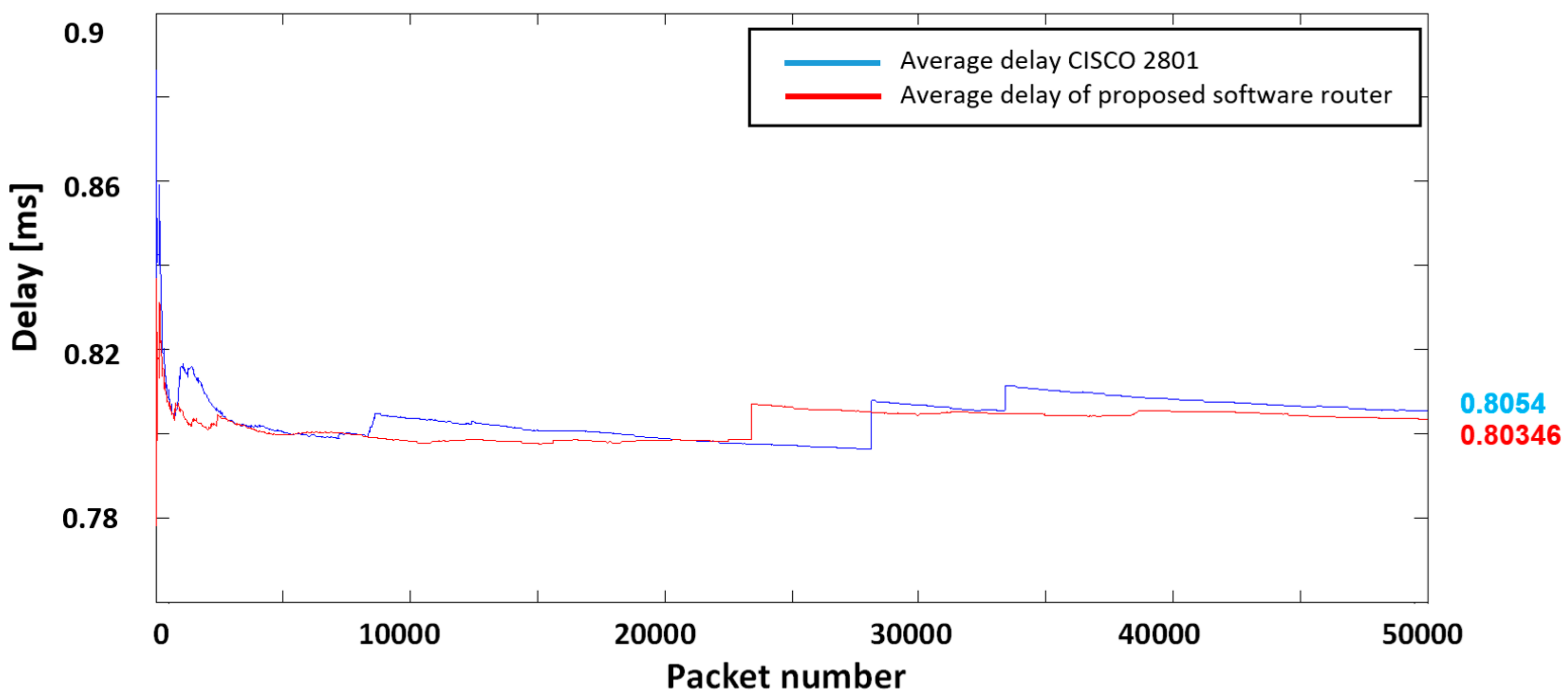

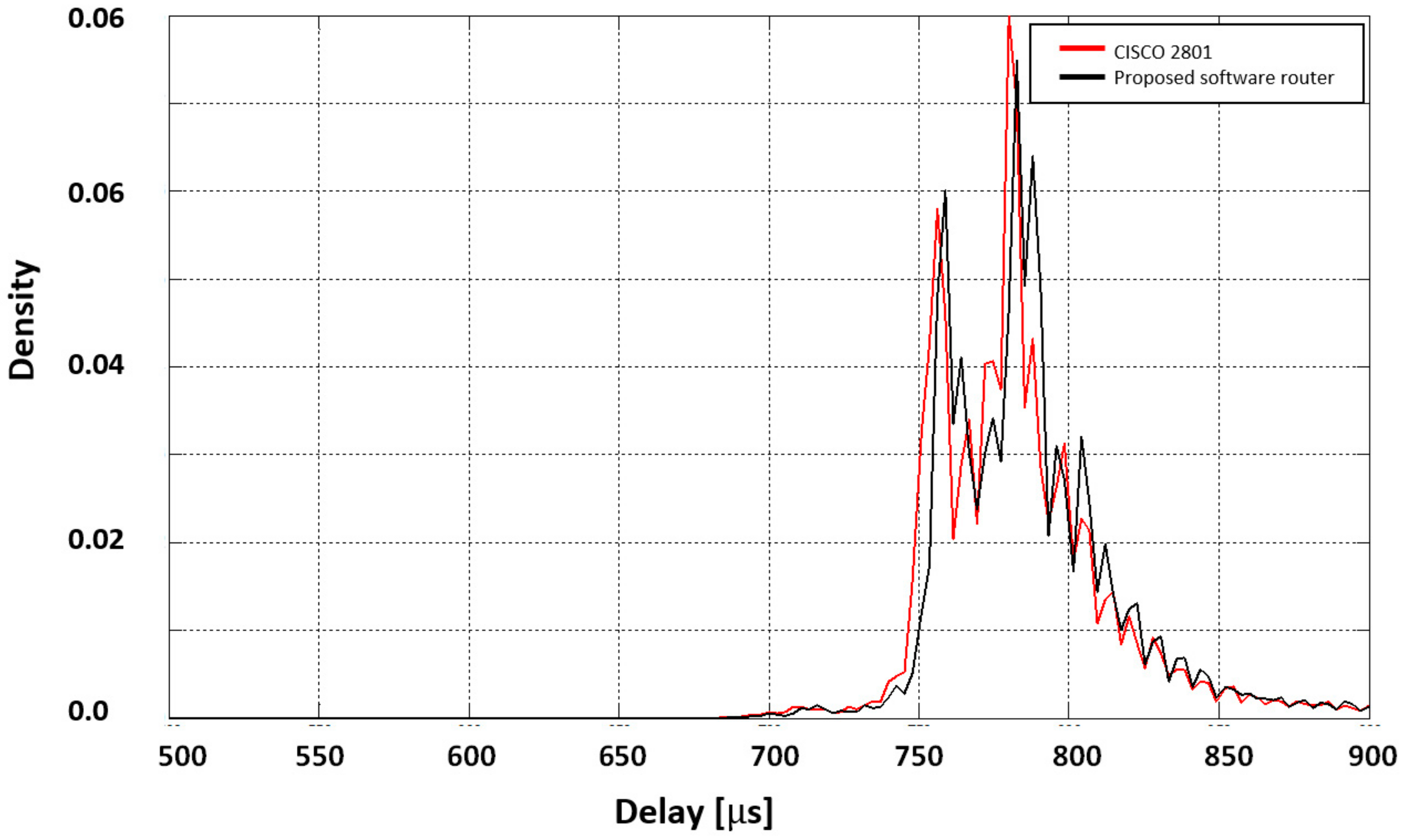

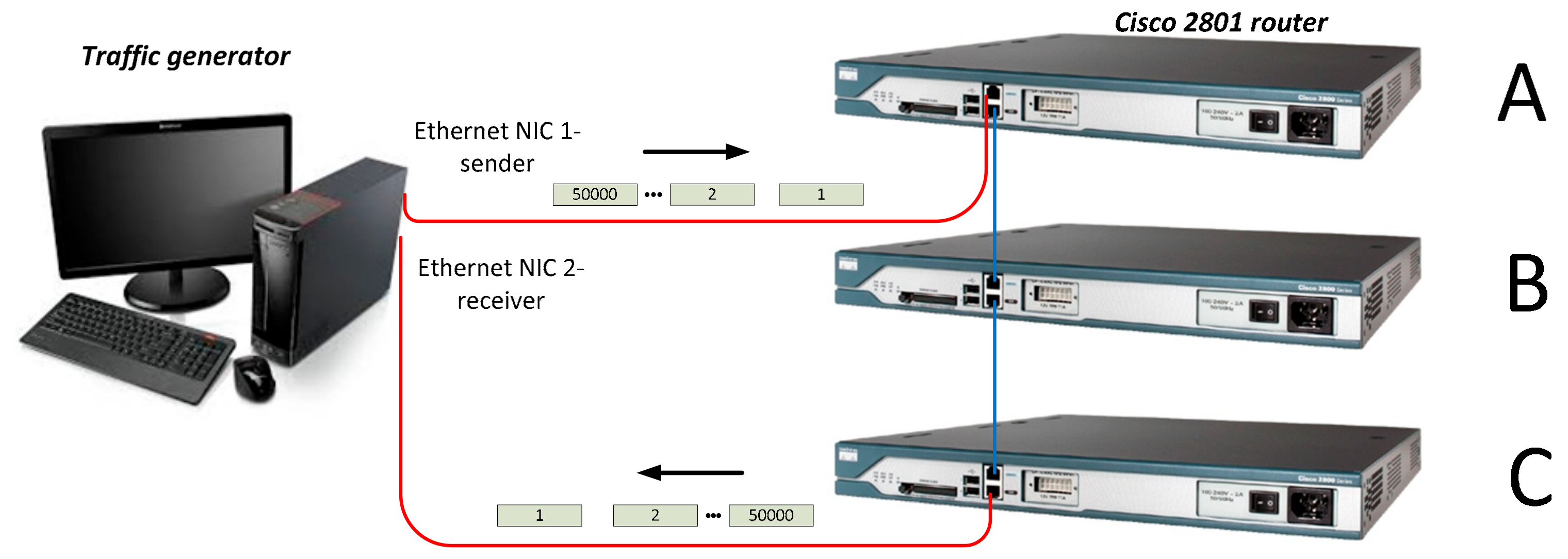

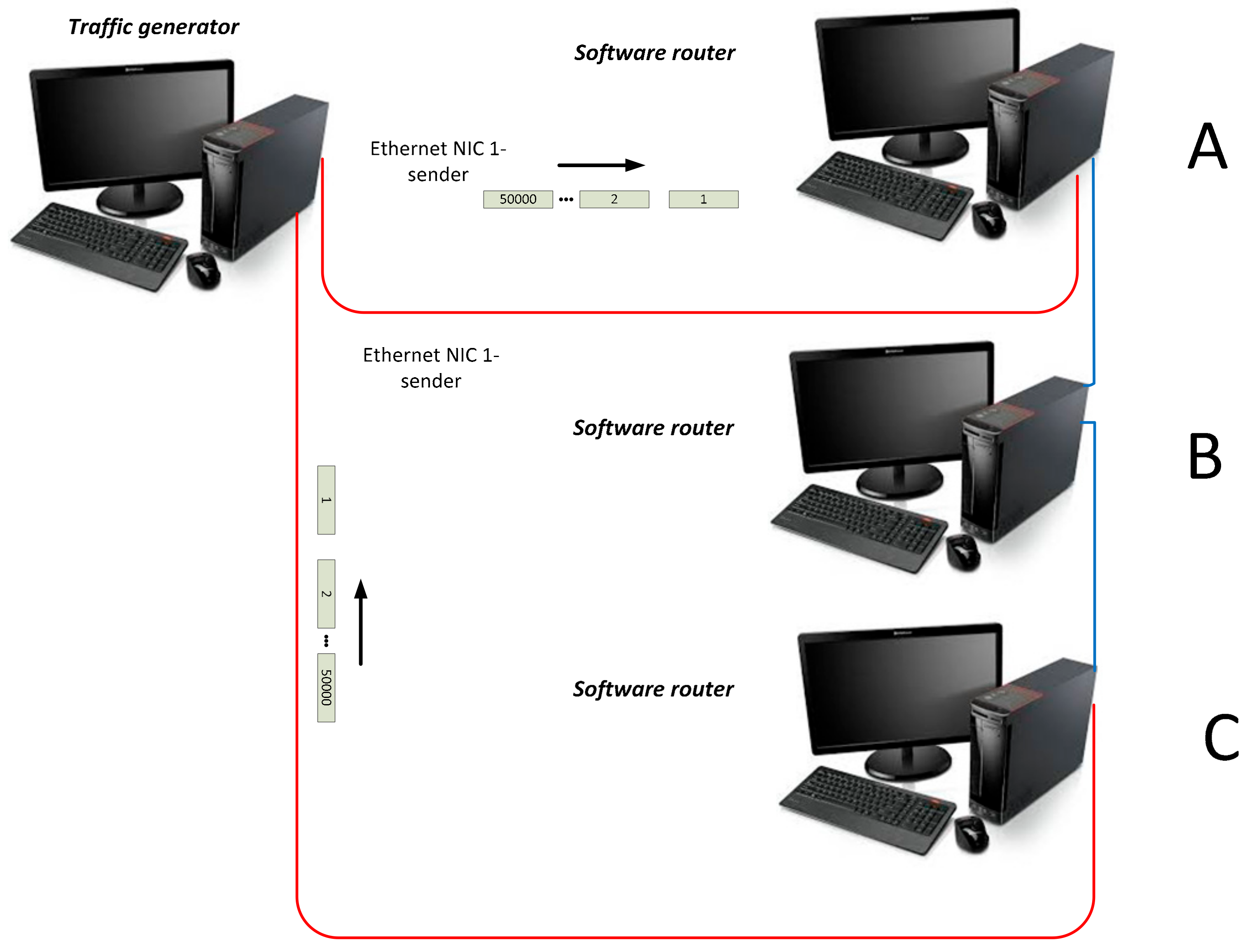

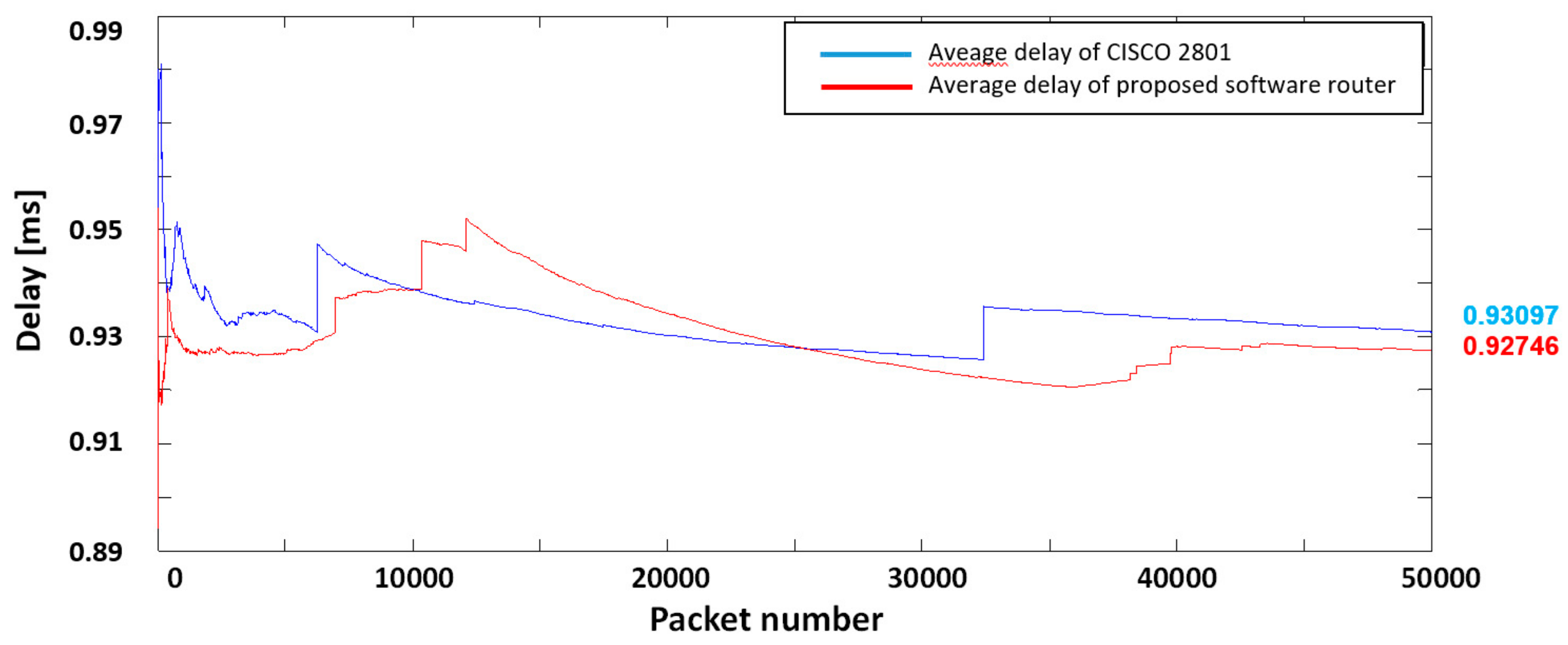

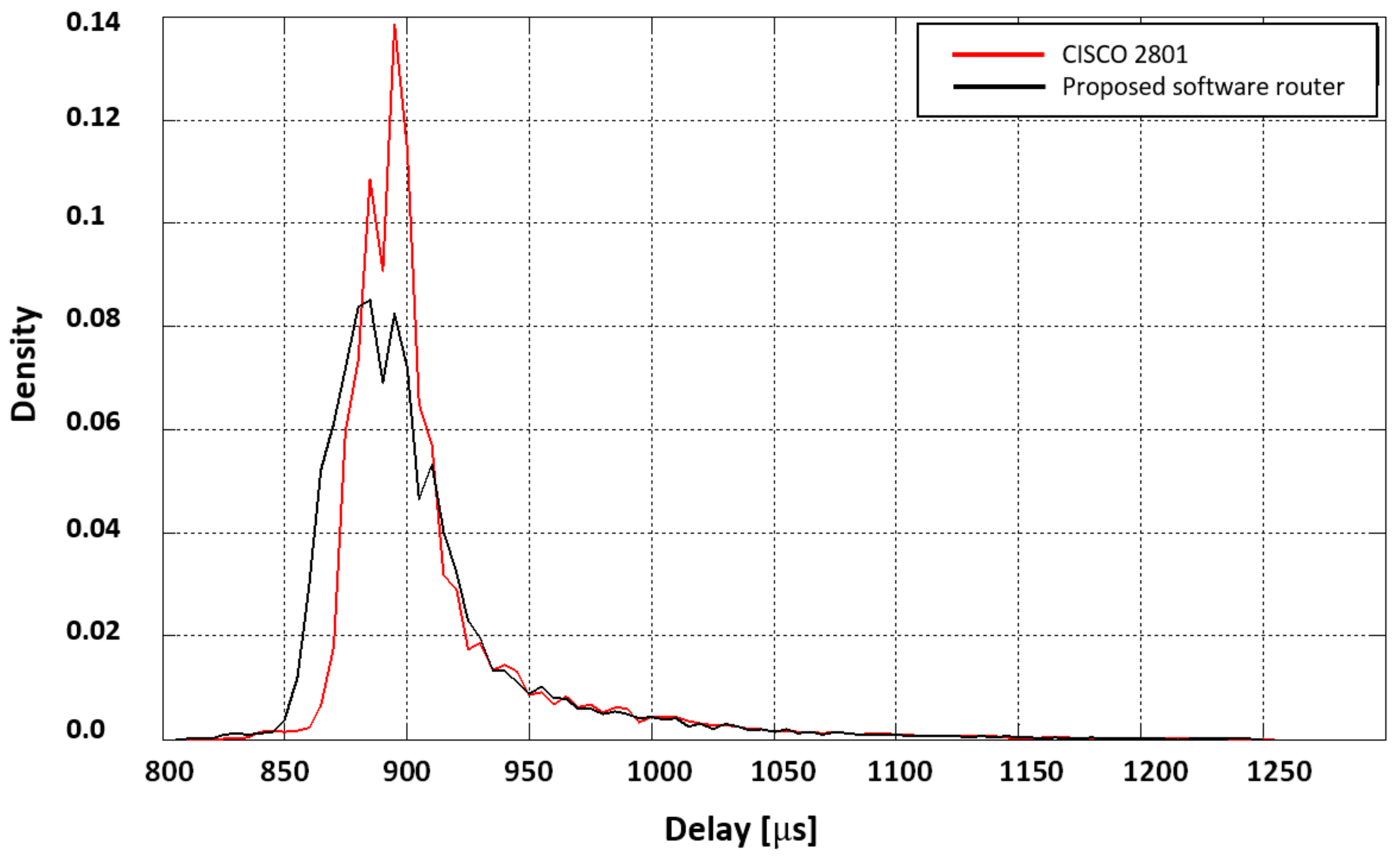

4.1. Method to Measure and Compare Packet Processing Time of Software Router with Prototype Hardware Router CISCO 2801

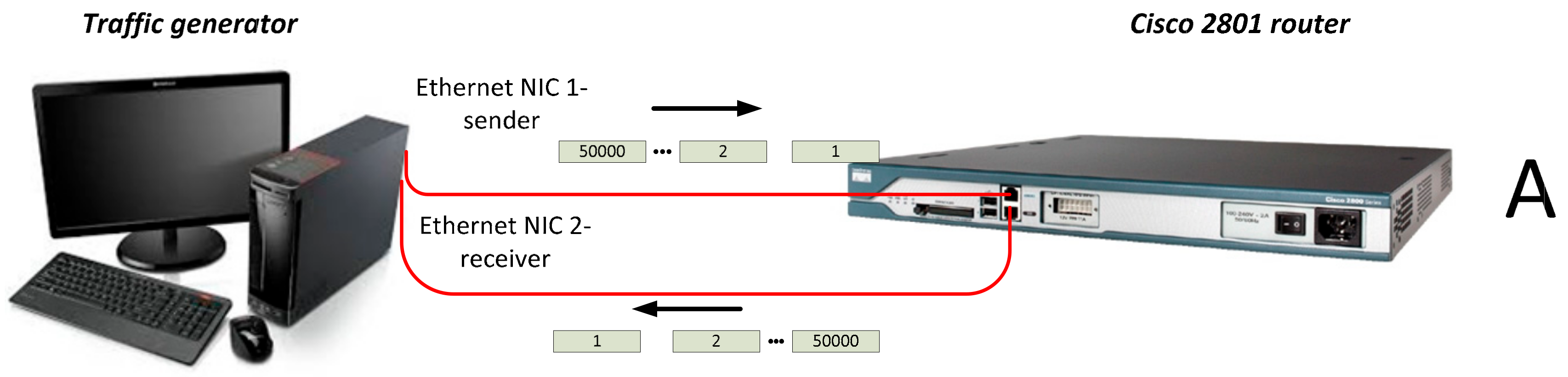

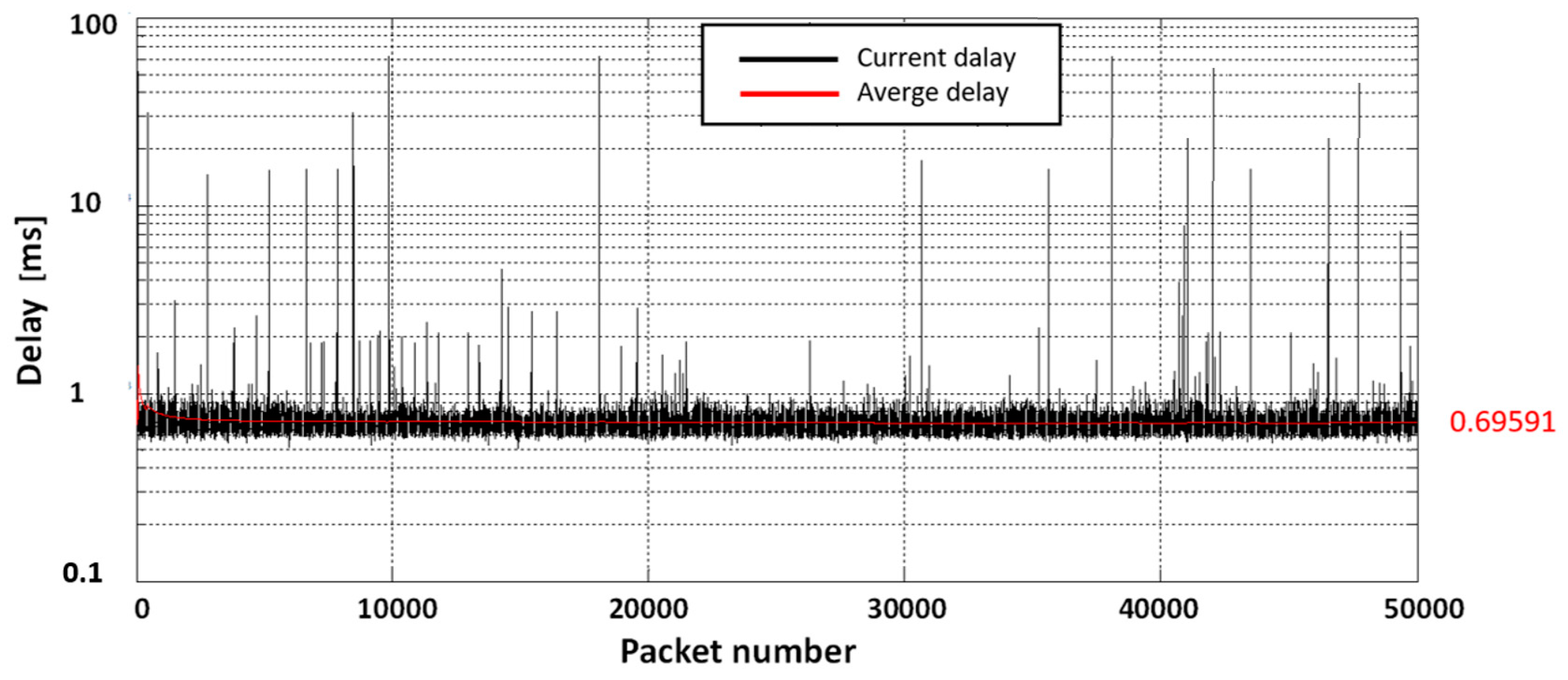

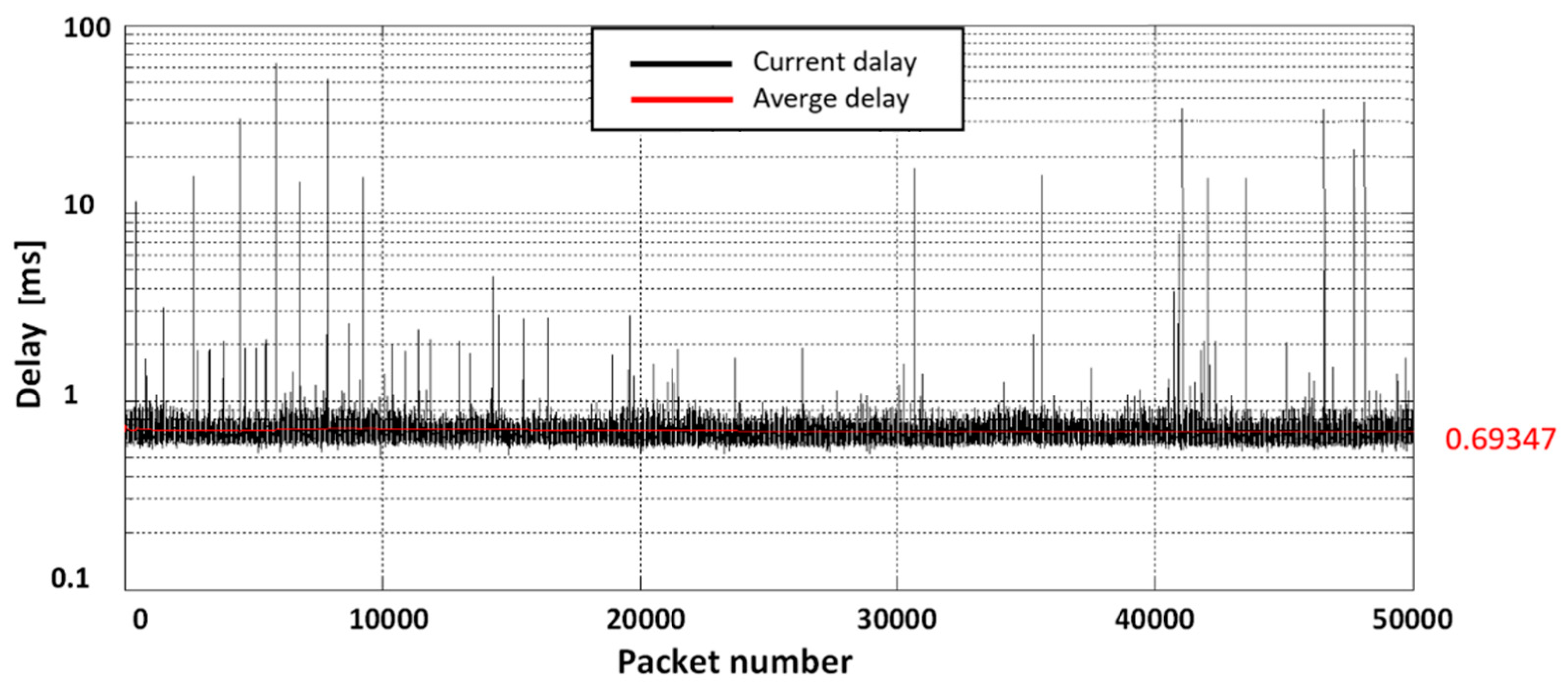

4.1.1. Experiment with 1 Hardware and 1 Software Router

4.1.2. Experiment with 2 Hardware and 2 Software Routers

4.1.3. Experiment with Three Hardware and Three Software Routers

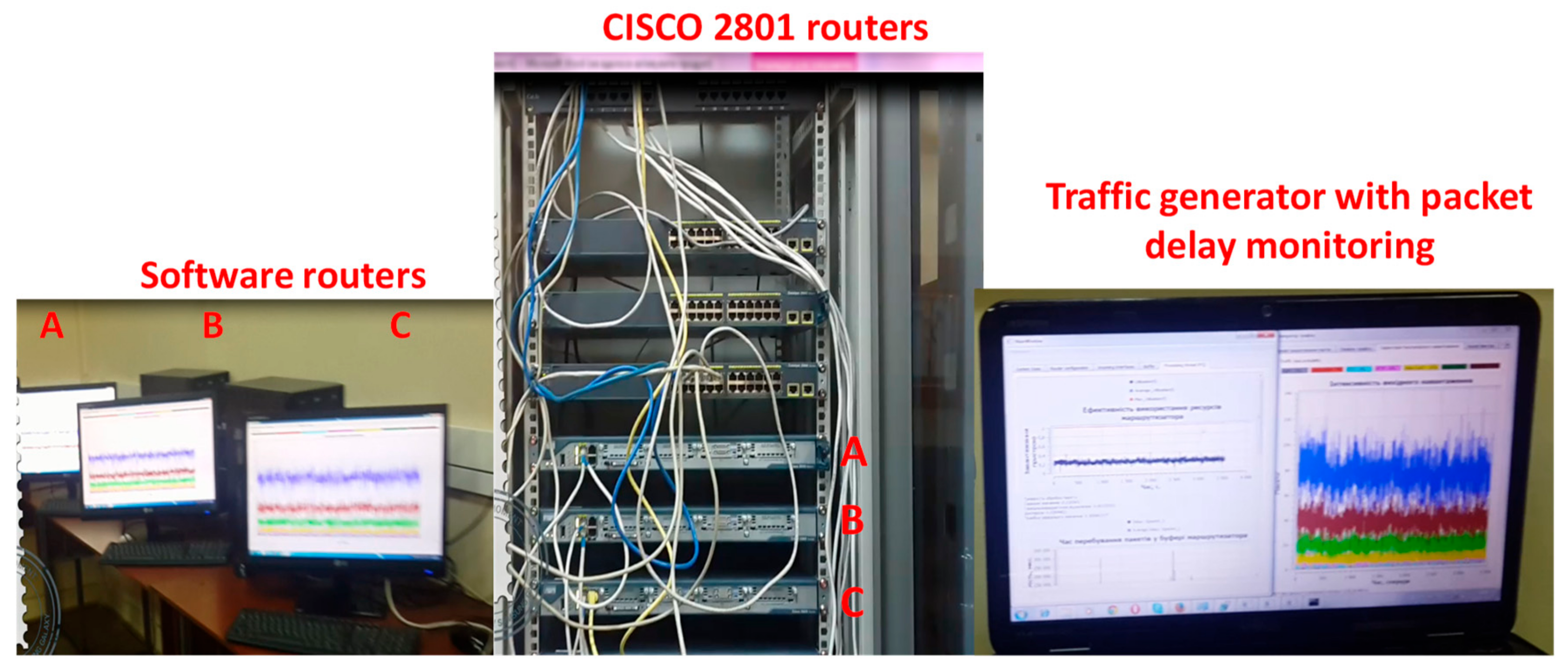

4.1.4. Experimental Test Bed

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Parane, K.; Prabhu Prasad, B.M.; Talawar, B. Design of an Adaptive and Reliable Network on Chip Router Architecture Using FPGA. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Symposium on VLSI Design, Automation and Test (VLSI-DAT), Hsinchu, Taiwan, 22–25 April 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, T.; Raumer, D.; Wohlfart, F.; Wolfinger, B.E.; Carle, G. Low Latency Packet Processing in Software Routers. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Performance Evaluation of Computer and Telecommunication Systems (SPECTS 2014), Monterey, CA, USA, 6–10 July 2014; pp. 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Lan, J. A Novel Router Software Architecture Supporting Reconfiguration. In Proceedings of the 2010 2nd International Workshop on Intelligent Systems and Applications, Wuhan, China, 22–23 May 2010; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas-Benítez, N.; Aquino-Santos, R.; Magaña-Espinoza, P.; Aguilar-Velazco, J.; Edwards-Block, A.; Medina Cass, A. Traffic Congestion Detection System through Connected Vehicles and Big Data. Sensors 2016, 16, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botta, A.; Dainotti, A.; Pescapé, A. Do You Trust Your Software-Based Traffic Generator? IEEE Commun. Mag. 2010, 48, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmerich, P.; Gallenmüller, S.; Antichi, G.; Moore, A.W.; Carle, G. Mind the Gap—A Comparison of Software Packet Generators. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM/IEEE Symposium on Architectures for Networking and Communications Systems (ANCS), Beijing, China, 18–19 May 2017; pp. 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.; Vajpeyee, M.; Kar, S.; Kumar, T.R.N. Performance Analysis and Redundancy Implementation of Open Source Embedded Router. In Proceedings of the 2012 National Conference on Communications (NCC), Kharagpur, India, 3–5 February 2012; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, H.; Qin, Y.; Xu, H.; Hao, C.; Cao, J. Robust Control Method for DC Microgrids and Energy Routers to Improve Voltage Stability in Energy Internet. Energies 2019, 12, 1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina Zarca, A.; Garcia-Carrillo, D.; Bernal Bernabe, J.; Ortiz, J.; Marin-Perez, R.; Skarmeta, A. Enabling Virtual AAA Management in SDN-Based IoT Networks. Sensors 2019, 19, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohler, E.; Morris, R.; Chen, B.; Jannotti, J.; Kaashoek, M.F. The Click Modular Router. ACM Trans. Comput. Syst. 2000, 18, 263–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, C.-H.; Lee, K.; Hwang, J.; Park, H.; Yoo, C. Kafe: Can OS Kernels Forward Packets Fast Enough for Software Routers? IEEE/ACM Trans. Netw. 2018, 26, 2734–2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Nakao, A. Improving Routing Table Lookup in Software Routers. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2015, 19, 957–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, A.G.; Birke, R.; Botto, G.; Chiaberge, M.; Finochietto, J.M.; Galante, G.; Mellia, M.; Neri, F.; Petracca, M. Boosting the Performance of PC-Based Software Routers with FPGA-Enhanced Network Interface Cards. In Proceedings of the 2006 Workshop on High Performance Switching and Routing 2006, 6-NaN, Poznan, Poland, 7–9 June 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryslupskyi, A.; Panchenko, O.; Beshley, M.; Seliuchenko, M. Improvement of Multiprotocol Label Switching Network Performance Using Software-Defined Controller. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 15th International Conference on the Experience of Designing and Application of CAD Systems (CADSM), Polyana, Ukraine, 26 February–2 March 2019; pp. 106–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolla, R.; Bruschi, R. The IP Lookup Mechanism in a Linux Software Router: Performance Evaluation and Optimizations. In Proceedings of the 2007 Workshop on High Performance Switching and Routing, Brooklyn, NY, USA, 30 May–1 June 2007; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, T.; Wohlfart, F.; Raumer, D.; Wolfinger, B.E.; Carle, G. Validated Model-Based Performance Prediction of Multi-Core Software Routers. Prax. Inf. Kommun. 2014, 37, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Agrawal, N.; Mishra, N. RTT Based Wormhole Detection Using NS-3. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Communication Networks, Bhopal, India, 14–16 November 2014; pp. 861–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Zuo, Y.; Zhang, F. Research on Comprehensive Performance Simulation of Communication IP Network Based on OPNET. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Intelligent Transportation, Big Data Smart City (ICITBS), Xiamen, China, 25–26 January 2018; pp. 195–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozi, N.N.H.; Ghafar, A.S.A.; Nordin, N.M.; Saparudin, F.A. Performance Evaluation of Multihop Device to Device (D2D) Communication Using Network Simulator and Emulator (NetSim). In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 10th Control and System Graduate Research Colloquium (ICSGRC), Shah Alam, Malaysia, 2–3 August 2019; pp. 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oujezsky, V.; Horvath, T. Case Study and Comparison of SimPy 3 and OMNeT++ Simulation. In Proceedings of the 2016 39th International Conference on Telecommunications and Signal Processing (TSP), Vienna, Austria, 27–29 June 2016; pp. 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dronyuk, I.; Fedevych, O.; Lipinski, P. Ateb-Prediction Simulation of Traffic Using OMNeT++ Modeling Tools. In Proceedings of the 2016 XIth International Scientific and Technical Conference Computer Sciences and Information Technologies (CSIT), Lviv, Ukraine, 6–10 September 2016; pp. 96–98. [Google Scholar]

- Bu, G.; Xie, D.; Chen, H.; Gao, M. Impacts on High Frequency Communications Based on OPNET. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Virtual Reality and Intelligent Systems (ICVRIS), Hunan, China, 10–11 August 2018; pp. 524–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigle, M.; Adurthi, P.; Hernández-Campos, F.; Jeffay, K.; Smith, F. Tmix: A Tool for Generating Realistic TCP Application Workloads in Ns-2. Comput. Commun. Rev. 2006, 36, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barford, P.; Crovella, M. Generating Representative Web Workloads for Network and Server Performance Evaluation. In Proceedings of the 1998 ACM SIGMETRICS Joint International Conference on Measurement and Modeling of Computer Systems, SIGMETRICS’98/PERFORMANCE’98, Madison, WI, USA, 22–26 June 1998; pp. 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemian, R.; Krishnamurthy, D.; Arlitt, M. Web Workload Generation Challenges—An Empirical Investigation. Softw. Pract. Exp. 2012, 42, 629–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Silvester, J.; Kim, H. Analyzing and Modeling Workload Characteristics in a Multiservice IP Network. IEEE Internet Comput. 2011, 15, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abhari, A.; Soraya, M. Workload Generation for YouTube. Multimed Tools Appl. 2009, 46, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veloso, E.; Almeida, V.; Meira, W.; Bestavros, A.; Jin, S. A Hierarchical Characterization of a Live Streaming Media Workload. IEEE/ACM Trans. Netw. 2006, 14, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best Network Traffic Generator Software & Tools for WAN & LAN Testing! Available online: https://www.ittsystems.com/network-traffic-generator/ (accessed on 9 November 2019).

- Patil, A.G.; Surve, A.R.; Gupta, A.K.; Sharma, A.; Anmulwar, S. Survey of Synthetic Traffic Generators. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Inventive Computation Technologies (ICICT), Coimbatore, India, 26–27 August 2016; Volume 1, pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Anmulwar, S.; Sapkal, A.M.; Batra, T.; Gupta, A.K.; Kumar, V. Comparative Study of Various Traffic Generator Tools. In Proceedings of the 2014 Recent Advances in Engineering and Computational Sciences (RAECS), Chandigarh, India, 6–8 March 2014; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolahi, S.S.; Narayan, S.; Nguyen, D.D.T.; Sunarto, Y. Performance Monitoring of Various Network Traffic Generators. In Proceedings of the 2011 UkSim 13th International Conference on Computer Modelling and Simulation, Cambridge, UK, 30 March–1 April 2011; pp. 501–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostinato Packet Generator. Available online: https://ostinato.org/ (accessed on 9 November 2019).

- iPerf-The TCP, UDP and SCTP Network Bandwidth Measurement Tool. Available online: https://iperf.fr/ (accessed on 9 November 2019).

- Packeth. Available online: http://packeth.sourceforge.net/packeth/Home.html (accessed on 9 November 2019).

- Goldstein, M.; Seheult, A.; Vernon, I. Assessing Model Adequacy. In Environmental Modelling; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: London, UK, 2013; pp. 435–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przystupa, K. Reliability Assessment Method of Device Under Incomplete Observation of Failure. In Proceedings of the 2018 18th International Conference on Mechatronics-Mechatronika (ME), Brno, Czechia, 5–7 December 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Przystupa, K.; Kozieł, J. Analysis of the Quality of Uninterruptible Power Supply Using a UPS. In Proceedings of the 2018 Applications of Electromagnetics in Modern Techniques and Medicine (PTZE), Raclawice, Poland, 9–12 September 2018; pp. 191–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojciechowski, S.; Wiackiewicz, M.; Krolczyk, G.M. Study on Metrological Relations Between Instant Tool Displacements and Surface Roughness During Precise Ball End Milling. Measurement 2018, 129, 686–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glowacz, A. Acoustic-Based Fault Diagnosis of Commutator Motor. Electronics 2018, 7, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, C.; Kochan, O. Method of Thermocouples Self Verification on Operation Place. Sens. Transducers 2013, 160, 55–61. [Google Scholar]

- Vasylkiv, N.; Kochan, O.; Kochan, R.; Chyrka, M. The Control System of the Profile of Temperature Field. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE International Workshop on Intelligent Data Acquisition and Advanced Computing Systems: Technology and Applications, Rende, Italy, 21–23 September 2009; pp. 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, M.; Kominami, D.; Leibnitz, K.; Murata, M. Reliable Design for a Network of Networks with Inspiration from Brain Functional Networks. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przystupa, K. Selected methods for improving power reliability. Przegląd Elektrotechniczny 2018, 94, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargent, R. Verification and Validation of Simulation Models. In Proceedings of the 2010 Winter Simulation Conference, Baltimore, MD, USA, 5–8 December 2010; Volume 37, pp. 166–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beisbart, C.; Saam, N.J. Computer Simulation Validation-Fundamental Concepts, Methodological Frameworks, and Philosophical Perspectives; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Beshley, M.; Pryslupskyi, A.; Panchenko, O.; Beshley, H. SDN/Cloud Solutions for Intent-Based Networking. In Proceedings of the 2019 3rd International Conference on Advanced Information and Communications Technologies (AICT), Lviv, Ukraine, 2–6 July 2019; pp. 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klymash, M.; Romanchuk, V.; Beshley, M.; Arthur, P. Investigation and Simulation of System for Data Flow Processing in Multiservice Nodes Using Virtualization Mechanisms. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE First Ukraine Conference on Electrical and Computer Engineering (UKRCON), Kiev, Ukraine, 29 May–2 June 2017; pp. 989–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanchuk, V.; Beshley, M.; Polishuk, A.; Seliuchenko, M. Method for Processing Multiservice Traffic in Network Node Based on Adaptive Management of Buffer Resource. In Proceedings of the 2018 14th International Conference on Advanced Trends in Radioelecrtronics, Telecommunications and Computer Engineering (TCSET), Slavske, Ukraine, 20–24 February 2018; pp. 1118–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aweya, J. Software Requirements for Switch/Routers. In Switch/Router Architectures: Shared-Bus and Shared-Memory Based Systems; Aweya, J., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 61–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanchuk, V.; Beshley, M.; Panchenko, O.; Arthur, P. Design of Software Router with a Modular Structure and Automatic Deployment at Virtual Nodes. In Proceedings of the 2017 2nd International Conference on Advanced Information and Communication Technologies (AICT), Lviv, Ukraine, 4–7 July 2017; pp. 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lifu, F.; Dongming, Y.; Bihua, T.; Yuanan, L.; Hefei, H. Technique for Network Performance Measurement Based on RFC 2544. In Proceedings of the 2012 Fourth International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Communication Networks, Phuket, Thailand, 24–26 July 2012; pp. 200–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seliuchenko, M.; Beshley, M.; Panchenko, O.; Klymash, M. Development of Monitoring System for End-to-End Packet Delay Measurement in Software-Defined Networks. In Proceedings of the 2016 13th International Conference on Modern Problems of Radio Engineering, Telecommunications and Computer Science (TCSET), Lviv, Ukraine, 23–26 February 2016; pp. 667–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klymash, M.; Beshley, H.; Seliuchenko, M.; Beshley, M. Algorithm for Clusterization, Aggregation and Prioritization of M2M Devices in Heterogeneous 4G/5G Network. In Proceedings of the 2017 4th International Scientific-Practical Conference Problems of Infocommunications. Science and Technology (PIC S T), Kharkov, Ukraine, 10–13 October 2017; pp. 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beshley, M.; Seliuchenko, M.; Panchenko, O.; Polishuk, A. Adaptive Flow Routing Model in SDN. In Proceedings of the 2017 14th International Conference The Experience of Designing and Application of CAD Systems in Microelectronics (CADSM), Lviv, Ukraine, 21–25 February 2017; pp. 298–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renteria-Cedano, J.; Rivera, J.; Sandoval-Ibarra, F.; Ortega-Cisneros, S.; Loo-Yau, R. SoC Design Based on a FPGA for a Configurable Neural Network Trained by Means of an EKF. Electronics 2019, 8, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frances-Villora, J.V.; Rosado-Muñoz, A.; Bataller-Mompean, M.; Barrios-Aviles, J.; Guerrero-Martinez, J.F. Moving Learning Machine towards Fast Real-Time Applications: A High-Speed FPGA-Based Implementation of the OS-ELM Training Algorithm. Electronics 2018, 7, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michałowska, J.; Tofil, A.; Józwik, J.; Pytka, J.; Budzyński, P.; Korzeniewska, E. Measurement of high-frequency electromagnetic fields in CNC machine tools area. In Proceedings of the 4th International Symposium on Wireless Systems within the International Conferences on Intelligent Data Acquisition and Advanced Computing Systems (IDAACS-SWS) IEEE 2018, Lviv, Ukraine, 20–21 September 2018; pp. 162–165. [Google Scholar]

- Mazurek, P.; Michałowska, J.; Kozieł, J.; Gad, R.; Wdowiak, A. The intensity of electromagnetic fields in the range of GSM 188 DECT, UMTS, WLAN inbuilt-up areas. Przegląd Elektrotechniczny 2018, 94, 202–205. [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson, P.; Constantinescu, D.; Popescu, A.; Fiedler, M.; Nilsson, A.A. Delay performance in IP routers. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Working Conference (HET-NETs’ 04), West Yorkshire, UK, 26–28 July 2004; pp. 15/1–15/10. [Google Scholar]

| Celeron J1800|2 Cores|2.41 GHz|RAM 4 GB | ||

| Series | Packet Size [byte] | Average delay [ms] |

| 1 | 64 | 1.24 |

| 2 | 128 | 1.79 |

| 3 | 512 | 1.98 |

| 4 | 1024 | 2.12 |

| 5 | 1500 | 2.2 |

| Intel Core i3-3230M|2.6 GHz| RAM 4 GB | ||

| Series | Packet size [byte] | Average delay [ms] |

| 1 | 64 | 0.42 |

| 2 | 128 | 0.79 |

| 3 | 512 | 0.98 |

| 4 | 1024 | 1.01 |

| 5 | 1500 | 1.21 |

| Intel Core i5-2410M|2.3 GHz|RAM 6 GB | ||

| Series | Packet size [byte] | Average delay [ms] |

| 1 | 64 | 0.33 |

| 2 | 128 | 0.48 |

| 3 | 512 | 0.52 |

| 4 | 1024 | 0.62 |

| 5 | 1500 | 0.68 |

| Core i7-7700|4 cores|3.6 GHz|RAM 8 GB | ||

| Series | Packet size [byte] | Average delay [ms] |

| 1 | 64 | 0.01 |

| 2 | 128 | 0.04 |

| 3 | 512 | 0.09 |

| 4 | 1024 | 0.12 |

| 5 | 1500 | 0.2 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jun, S.; Przystupa, K.; Beshley, M.; Kochan, O.; Beshley, H.; Klymash, M.; Wang, J.; Pieniak, D. A Cost-Efficient Software Based Router and Traffic Generator for Simulation and Testing of IP Network. Electronics 2020, 9, 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics9010040

Jun S, Przystupa K, Beshley M, Kochan O, Beshley H, Klymash M, Wang J, Pieniak D. A Cost-Efficient Software Based Router and Traffic Generator for Simulation and Testing of IP Network. Electronics. 2020; 9(1):40. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics9010040

Chicago/Turabian StyleJun, Su, Krzysztof Przystupa, Mykola Beshley, Orest Kochan, Halyna Beshley, Mykhailo Klymash, Jinfei Wang, and Daniel Pieniak. 2020. "A Cost-Efficient Software Based Router and Traffic Generator for Simulation and Testing of IP Network" Electronics 9, no. 1: 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics9010040

APA StyleJun, S., Przystupa, K., Beshley, M., Kochan, O., Beshley, H., Klymash, M., Wang, J., & Pieniak, D. (2020). A Cost-Efficient Software Based Router and Traffic Generator for Simulation and Testing of IP Network. Electronics, 9(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics9010040