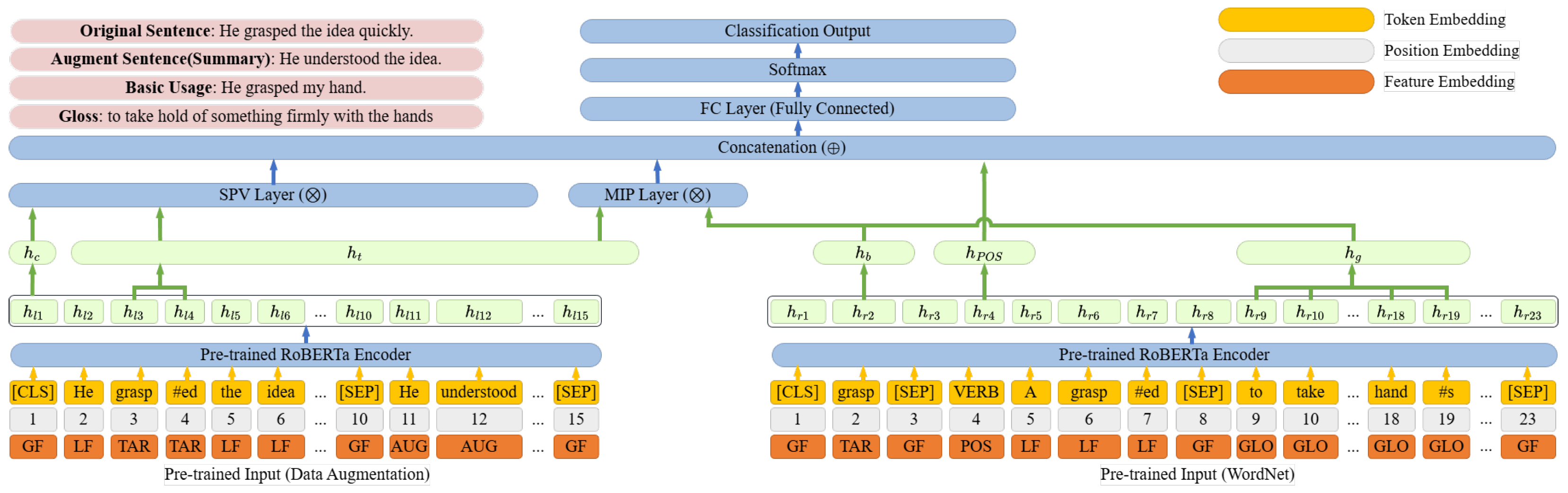

3.1. Data Augmentation

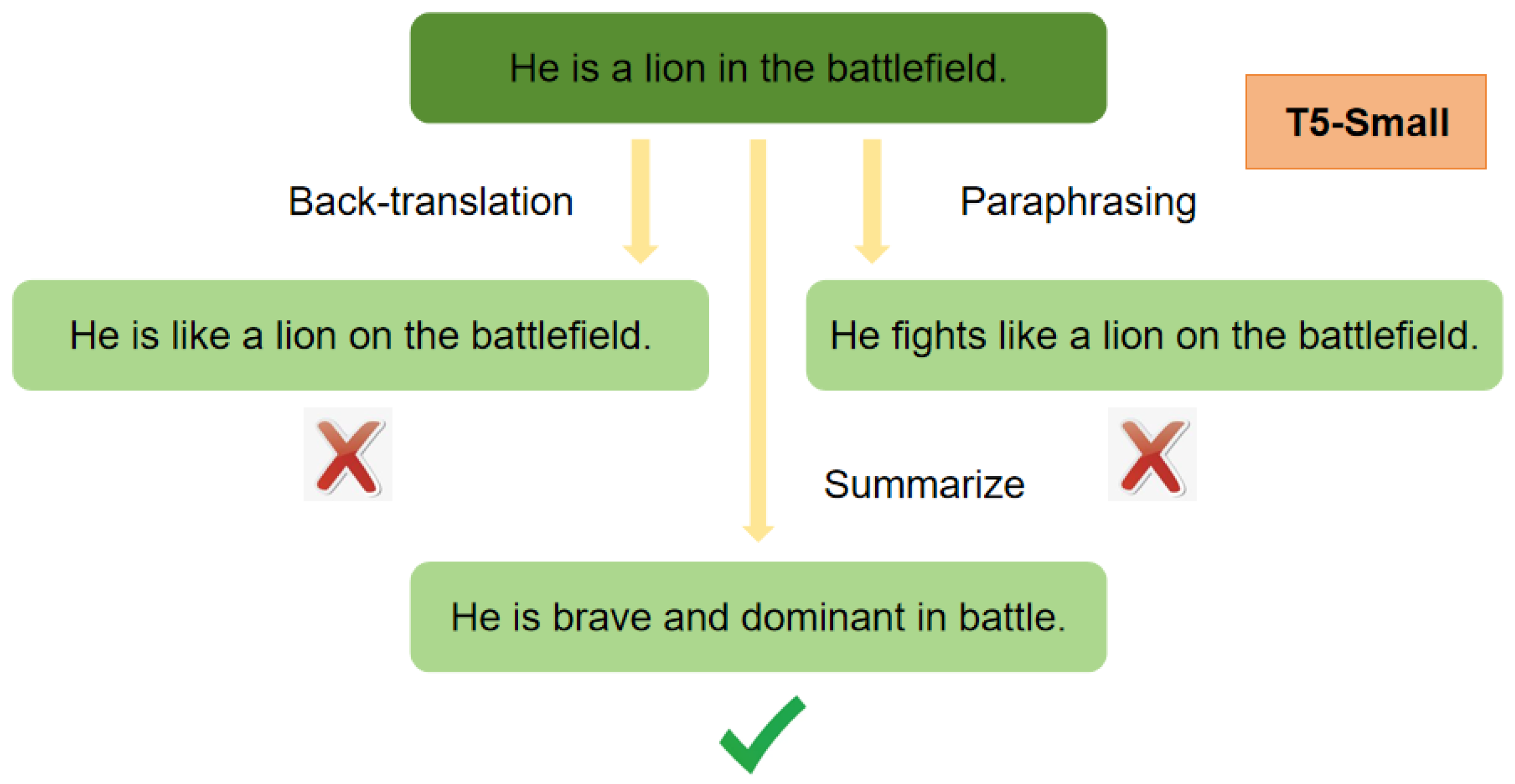

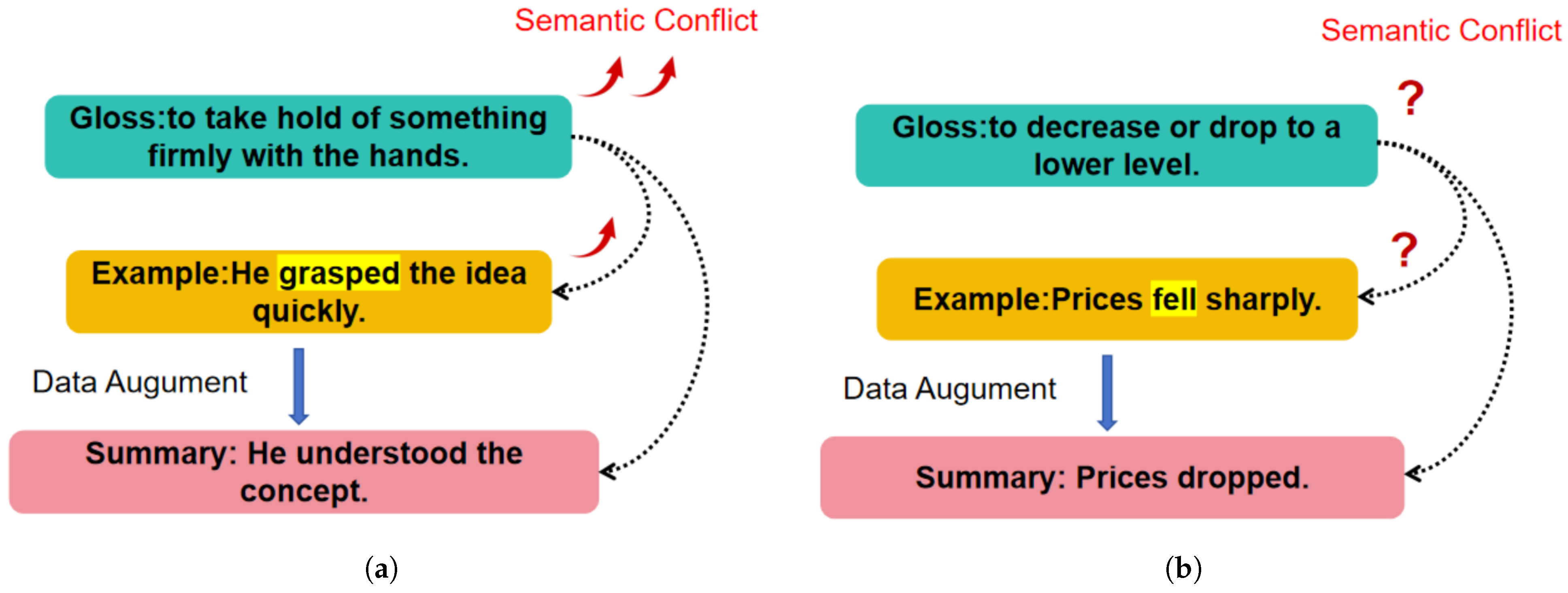

Since metaphors in the original sentences used for metaphor recognition are often highly conventionalized, they fail to explicitly reveal the semantic conflict between the contextual meaning of a metaphorical word and its original or literal meaning. For this reason, we adopt summary generation as the core form of data augmentation, as it directly targets the key semantic property required for metaphor recognition—namely, the actual meaning of the target word in context. Unlike surface-level data augmentation techniques, abstractive summarization preserves the global event structure while filtering out peripheral lexical details, thereby recovering the true meaning of the target word within the context. This property is particularly important for metaphor recognition, which relies on detecting semantic conflicts between a word’s contextual meaning and its conventional or literal sense. By generating a concise summary of the original sentence and concatenating it with the original input, the summary serves as a form of semantic anchoring, enabling the SPV layer to focus more on the conflict between the conventional semantics of the target word and its context, and allowing the MIP layer to concentrate more on the conflict between conventional semantics and contextual semantics. While other data augmentation techniques can enrich the context, the sentences they generate still retain metaphorical usage and lack this semantic anchoring effect, thus failing to deepen the semantic conflict. For example, synonym replacement or back-translation merely rephrase the sentence at the surface level and cannot explicitly reveal the true contextual meaning of the target word in the original context, as illustrated in

Figure 3.

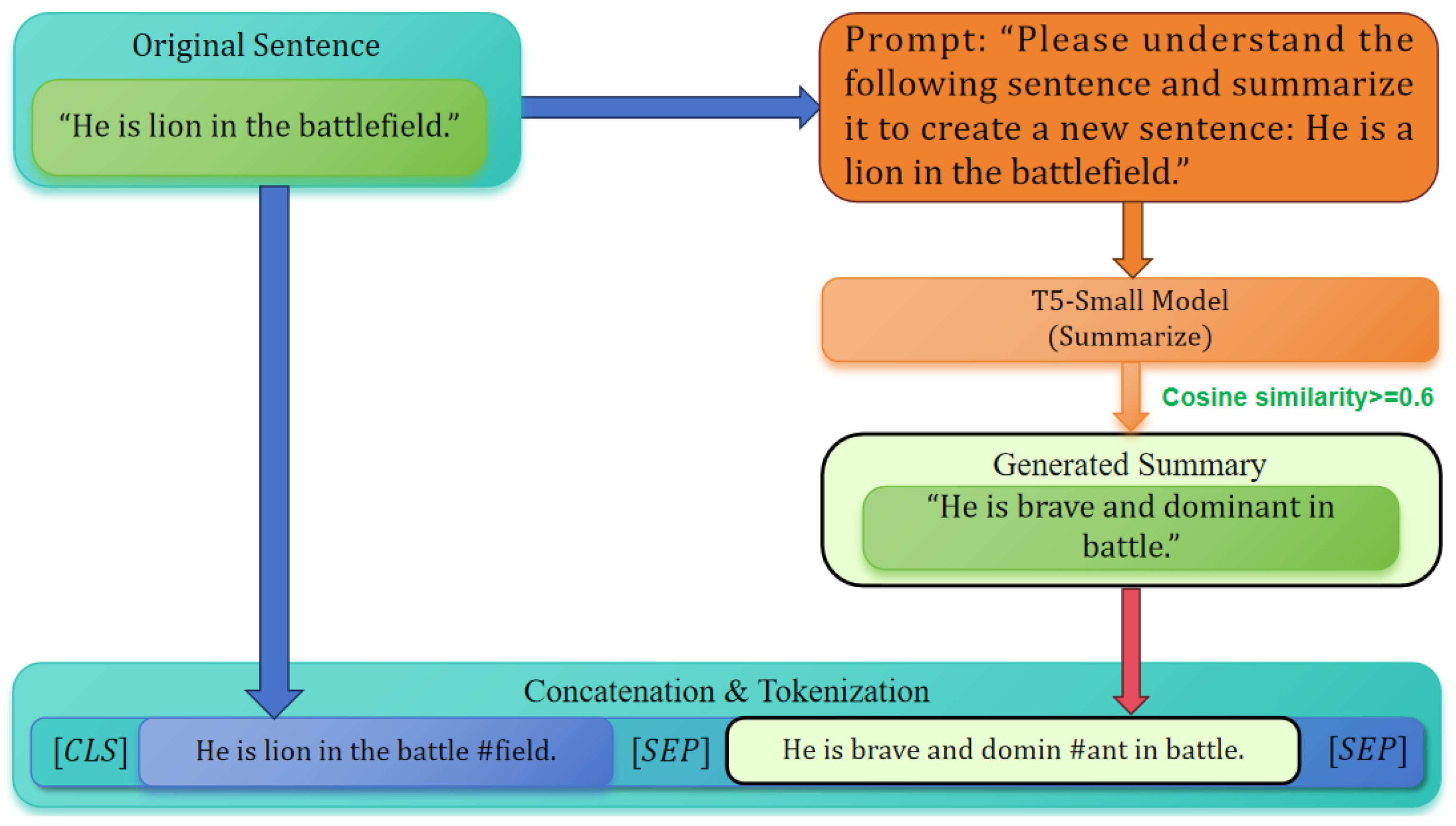

We choose T5-small as the summarization model for data augmentation based on a balanced consideration of effectiveness and efficiency. In terms of summarization quality, T5-small is a pretrained text-to-text transformation model that has been shown to generate coherent and semantically faithful summaries despite its relatively small scale. For the purpose of data augmentation, the goal is not to produce linguistically sophisticated or highly abstractive summaries, but rather to generate stable and semantically aligned paraphrases that capture the core event meaning, which is desirable for maintaining label consistency in metaphor recognition. From an efficiency perspective, T5-small has clear advantages over larger variants such as T5-base or T5-large. Its smaller number of parameters results in substantially lower computational cost, faster inference speed, and reduced memory consumption. This is particularly important because summary-based augmentation is applied to the entire training corpus and is performed during offline preprocessing. Using larger summarization models would significantly increase preprocessing time and resource consumption without yielding commensurate improvements in downstream metaphor recognition performance.

Figure 4 illustrates the workflow of generating summaries with T5-small and concatenating them with the original sentences. The figure provides a complete data augmentation example, including the specific sentence–summary pair, the prompt, and the concatenation strategy. It is important to note that after concatenation, the original contextual information of the sentence is fully preserved. The role of the summary is not to introduce additional context, but to provide a clearer and more explicit form of semantic anchoring. To ensure summary quality, we measure the semantic similarity between the original sentence and its generated summary, and retain only summaries with a cosine similarity of at least 0.6. If the similarity score falls below this threshold, the original sentence is used as the summary for concatenation. Finally, we randomly sample 1000 generated summaries, whose average sentence length is 17.8 words. Taking the VUA Verb

tr dataset (For relevant information about the dataset, please refer to

Section 4.1), which has the longest average sentence length among the evaluated datasets, as an example, the original sentences have an average length of 25 words, while the concatenated sentence–summary pairs have an average length of 42.8 words. After BERT WordPiece tokenization, this corresponds to approximately 47–56 tokens, which is well below BERT’s maximum input length of 512 tokens. Therefore, input length constraints do not pose a concern for the proposed data augmentation strategy. In addition, we generate enhanced data at a 1:1 ratio, which means that each sample in the training or testing set generates an enhanced data.

3.2. Semantic Matching Based on SPV and MIP

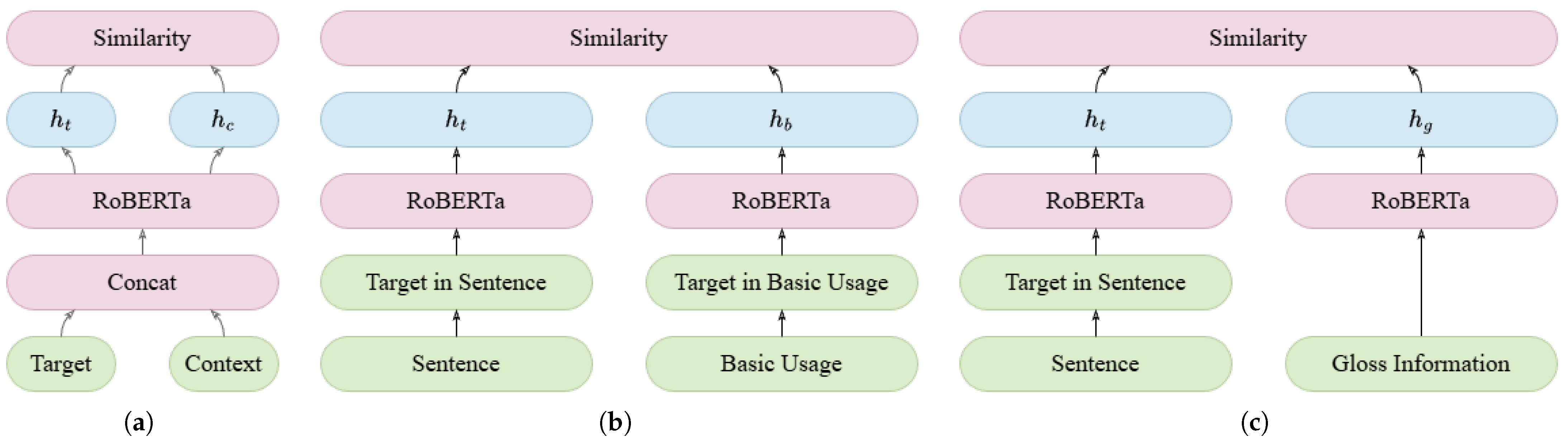

Semantic matching aims to measure the similarity between two given texts, with Interaction-based models and Representation-based models being the two main approaches. In this paper, we employ the above two semantic matching models to implement SPV and MIP. Unlike MisNet [

5], we choose RoBERTa [

16] as the encoder for both semantic matching models. Compared to BERT [

15], RoBERTa enhances the pre-training process and improves robustness.

Interaction-based SPV model: For interaction-based models (IM), two texts are concatenated as input, allowing every token in the input to fully interact with all other tokens [

19,

20]. The SPV mechanism emphasizes the inconsistency between the target word and its surrounding context, which can be measured through the semantic similarity between them. By concatenating the contextual information, the semantic discrepancy between the target word and its context is further amplified. As illustrated in

Figure 5a, we adopt an interaction-based model to implement SPV, since the target word and its context originate from the same sequence and are naturally concatenated. In our approach, they are treated as two textual components to be matched. Consequently, within RoBERTa, they can fully interact through multi-head self-attention [

21]. Finally, we extract the contextualized embedding of the target word

and the contextual representation

to compute their semantic similarity. Representation-based model for MIP: For representation-based models (RM), the two input texts are encoded independently by separate encoders, such that no interaction occurs between them during encoding [

22,

23]. The MIP mechanism aims to determine whether a target word has a more basic meaning. Accordingly, we compute the semantic similarity between the target word in the given sentence and its basic meaning representation. As shown in

Figure 5b, we model MIP using an RM framework, where the sentence containing the target word and its basic usage are encoded by two independent encoders to avoid unnecessary interaction. This design allows the model to better capture the contextual meaning of the target word and its basic meaning. As shown in

Figure 5c, after incorporating gloss information, we further compare the semantic similarity between the target word and its gloss, thereby strengthening the modeling of semantic incongruity. Finally, we obtain the contextual target embedding

, the basic meaning embedding

, and the gloss embedding

, and compute their respective semantic similarities.

3.3. EGSNet Architecture

Combining MIP and SPV: The use of SPV for metaphor detection relies on identifying semantic incongruity between a target word and its surrounding context. However, a conventional metaphorical target often does not occur in a conflicting context, as the surrounding context is usually shared with the target word itself. In such cases, SPV may become ineffective [

24,

25]. To address this issue, we introduce a data augmentation strategy that generates a summary and appends it to the original sentence. The summary partially restores the literal meaning of the target word, thereby amplifying the semantic discrepancy between the metaphorical usage and its context.

MIP, on the other hand, relies on comparing the basic meaning of a target word with its contextualized meaning. MisNet [

5] employs the basic usage of a word to represent its literal meaning in order to handle novel metaphors. However, for conventional metaphors, the usage of the word often does not differ significantly from its basic meaning. Therefore, a more abstract and conceptual representation of the target word is required to better distinguish it from its contextual usage. To address this limitation, we extend MisNet by incorporating gloss information, which provides a more abstract and conceptual description than basic usage, enabling the model to better capture conventional metaphors.

Finally, we integrate both MIP and SPV to achieve more effective metaphor detection. As illustrated in

Figure 2, EGSNet adopts a Siamese architecture to combine MIP and SPV. The left branch encodes the input sentence together with its generated summary, while the right branch encodes the target word along with its part-of-speech tag, basic usage, and gloss information. MIP is implemented across the two encoders, whereas SPV operates within the left encoder.

The input of the left encoder: the left RoBERTa encoder input is the processed given sentence and its summary.

where [CLS] and [SEP] are the two special tokens of RoBERTa.

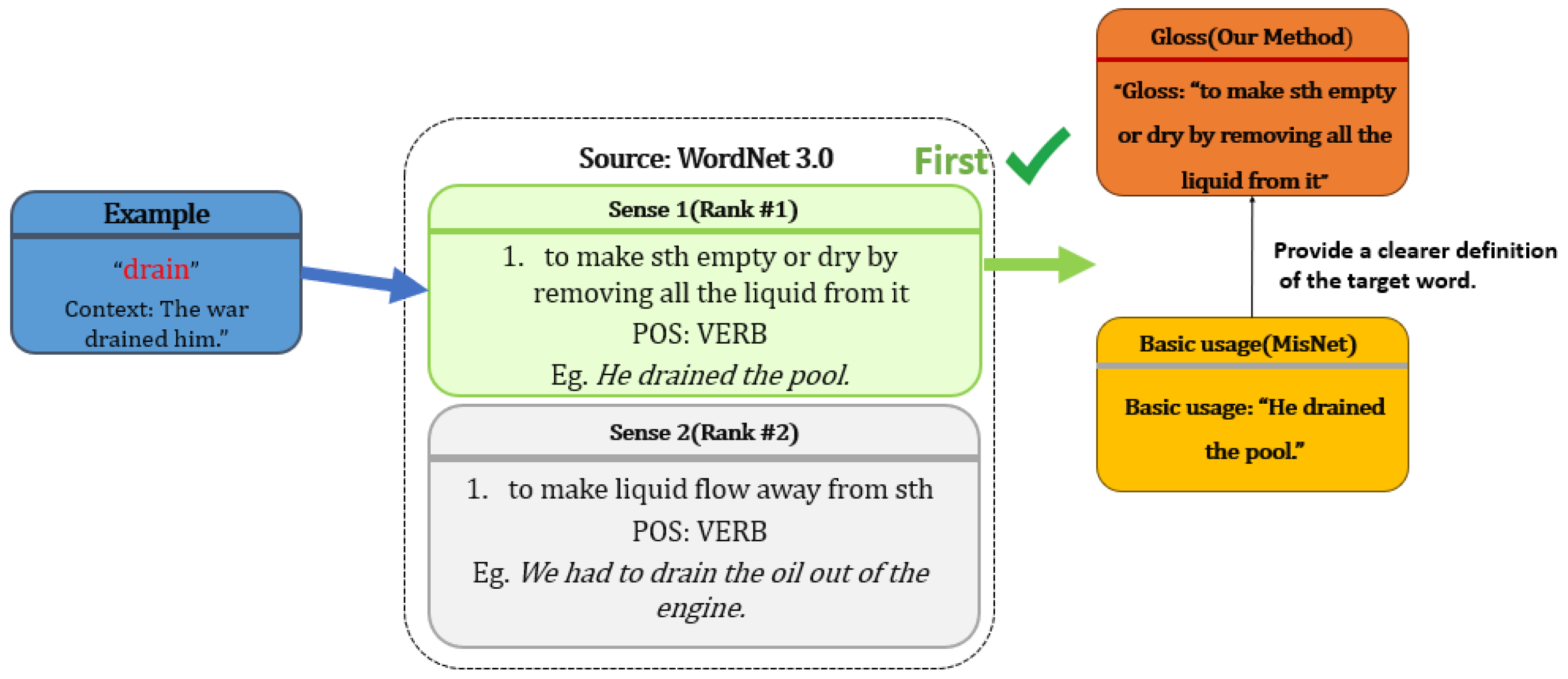

The input of the right encoder: The input for the right encoder is constructed by concatenating the target word, its Part-of-Speech (POS) tag, its basic usage and its gloss. The basic usage and gloss (representing the direct or most fundamental meaning of the target word) are retrieved from WordNet using the retrieval method we have established, as shown in

Figure 6. Formally, the input sequence

is defined as:

In instances where the basic usage and gloss cannot be successfully retrieved, the sequence is reduced to utilizing only the target word and its POS tag.

Input Features: Distinct components of the input sequence exert varying influences on metaphor detection. While the Self-Attention mechanism in BERT enhances semantic representations for input tokens [

21], it may not be sufficient to fully distinguish the functional roles of heterogeneous input parts. To address this limitation, we introduce input type feature embeddings to the BERT input layer for both the left and right encoders. We design four specific features, which are embedded into fixed-length vectors:

POS Feature: Represents the POS tag of the target word. This feature is exclusive to the right encoder input.

Target Feature: Represents the target word itself. This feature is shared and identical across both the left and right inputs.

Augment Feature: Represents the feature of enhanced data (summary), which only appears in the left encoder.

Gloss Feature: Represents the feature of gloss, which only appears in the right encoder.

Local Feature: Following [

8,

9], we define the clause containing the target word as the local context. For simplicity, clauses are separated by punctuation such as commas, periods, exclamation marks, and question marks. Since a basic usage is typically brief, we treat the entire basic usage as a local feature.

Global Feature: Encompasses all tokens that are not categorized as POS tags, target words, summary, gloss, or local features.

Following tokenization via the Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE) algorithm [

26], the left input

is segmented into

n tokens, while the right input

comprises

m tokens. The final input representation for BERT is composed of the sum of token embeddings, positional embeddings, and the aforementioned feature embeddings. We utilize RoBERTa to generate contextualized representations:

where

and

denote the embedding matrices of

and

, respectively, with

d representing the hidden dimension size of RoBERTa.

From

, we derive the contextual meaning of the target word, denoted as

. If the target word is fragmented into

k sub-tokens by BPE starting at index

u,

is calculated by averaging these token embeddings:

where

u indicates the starting position of the target word in the left input.

Similarly, based on

, we obtain the basic meaning of the target word, denoted as

. Note that it is difficult to determine the exact position of the target word within the basic usage, as it may not be presented in its original form, and the basic usage is not always precise. However, we do not need to know the precise position of the target word in the basic usage. We simply anchor the target word at the first position of the right encoder (as shown in the input section of the right encoder in

Figure 2), because the Transformer encoder applies a self-attention mechanism, allowing the target word in

to automatically focus on relevant parts of the basic usage and gloss [

21]. So,

is calculated by averaging these token embeddings:

in the input to the right encoder, the starting position of the target word is fixed at 1.

If the gloss is decomposed into

p sub-tokens by BPE, with a starting position of

o, then

is calculated by averaging these token embeddings:

where

o indicates the starting position of the target word in the left input.

For the left input, we compute the average of the entire embedding matrix

to obtain the global context embedding:

The

layer contrasts the basic meaning vector

with the contextual target meaning vector

. The

layer contrasts the gloss vector

with the contextual target meaning vector

. We employ a linear transformation to implement the MIP interaction:

where

denotes a readout function. Here,

represents the absolute difference, ; denotes concatenation, and * signifies the Hadamard product. These operations are combined to extract multi-faceted representations.

and

correspond to the weight matrix and bias of

, while

and

correspond to the weight matrix and bias of

.

Similarly, we perform the SPV operation on the context vector

and the contextual target meaning vector

:

where

and

are the weight and bias parameters of the SPV layer.

Given the significance of Part-of-Speech (POS) information in metaphor detection, we explicitly extract the POS vector

from the right encoder. Finally, we integrate the information from

,

, SPV, and POS to determine the metaphoricity of the target word:

where

W and

b represent the weight and bias, respectively.

denotes the softmax function, and

indicates the predicted label distribution.