DPAF-SA: A Formation Control Algorithm for Dynamic Allocation and Fusion of Potential Fields for UAV Swarms

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Related Works

1.1.1. Consensus-Based Formation Control

1.1.2. Obstacle Avoidance for Formations

1.1.3. Formation Configuration and Optimization

1.2. Motivations and Contributions

- Lack of Assignment Optimization for Convergence: Existing research generally lacks a dynamic position assignment mechanism. Specifically, it fails to dynamically optimize which UAV should fly to which formation position point during the formation convergence process based on the global position distribution—a combinatorial optimization problem. This deficiency leads to the aforementioned inefficiency in convergence.

- Decoupling of Obstacle Avoidance and Formation Optimization: As demonstrated in [12,13], existing obstacle avoidance methods based on consensus algorithms and APF address safety concerns but generate repulsive fields that are often localized and reactive. These approaches lack tight coupling with higher-level formation-optimization objectives, making it difficult for UAVs to efficiently recover from or dynamically adjust to globally optimal formations after obstacle avoidance.

- Insufficient Real-time Intra-Formation Optimization: As noted in [16,17,20], existing formation optimization methods predominantly rely on offline planning or focus on steady-state maintenance. In high-speed, dense obstacle-avoidance scenarios with strong disturbances, these approaches lack the capability to dynamically adjust positions within the formation in real time. Consequently, they struggle to rapidly reconfigure and restore optimal formations while ensuring safety.

- A DPAF-SA hybrid formation obstacle avoidance algorithm is proposed: integrating the global search capability of the simulated annealing algorithm (SA) into the artificial potential field (APF) to optimize the consensus control input. This addresses the issue of traditional APF algorithms easily getting stuck in local optima in complex obstacle environments, thereby significantly improving the formation’s obstacle-avoidance efficiency.

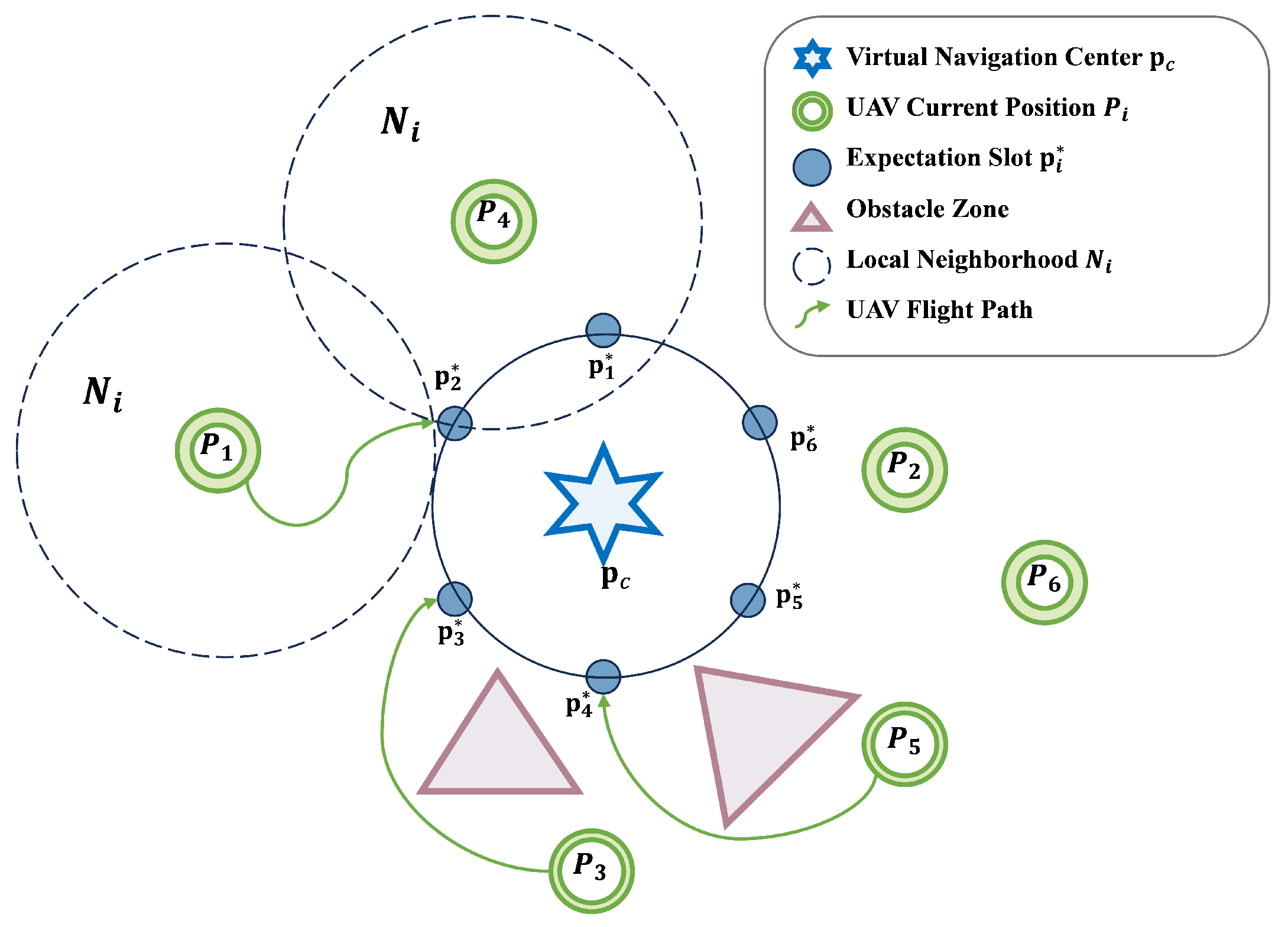

- Designed a dynamic position allocation and virtual center framework: Employing a virtual center-follower architecture, an annealing simulation algorithm is introduced to solve online for the optimal drone position mapping under the current state. This enables each UAV to be dynamically assigned to the most advantageous position at any given moment (rather than through pre-fixed allocation). Concurrently, a dynamic virtual center—adjusted in real time based on the cluster’s current center of mass—is proposed. This provides a dynamic reference for position allocation, thereby achieving rapid formation convergence.

- A Hardware-in-the-Loop (HIL) verification architecture was established: To address the limitations of traditional numerical simulation in practical application validation, a virtual combat platform was developed using the Unity3D engine. This architecture integrates real control loops with a virtual environment, enabling closed-loop testing of algorithms in simulated real-world scenarios and significantly enhancing the credibility of verification results.

2. Problem Description

3. Methods

3.1. Formation Consistency Algorithm Design

3.2. Position Optimization and Obstacle Avoidance Mechanism Algorithm Design

4. Simulation Verification

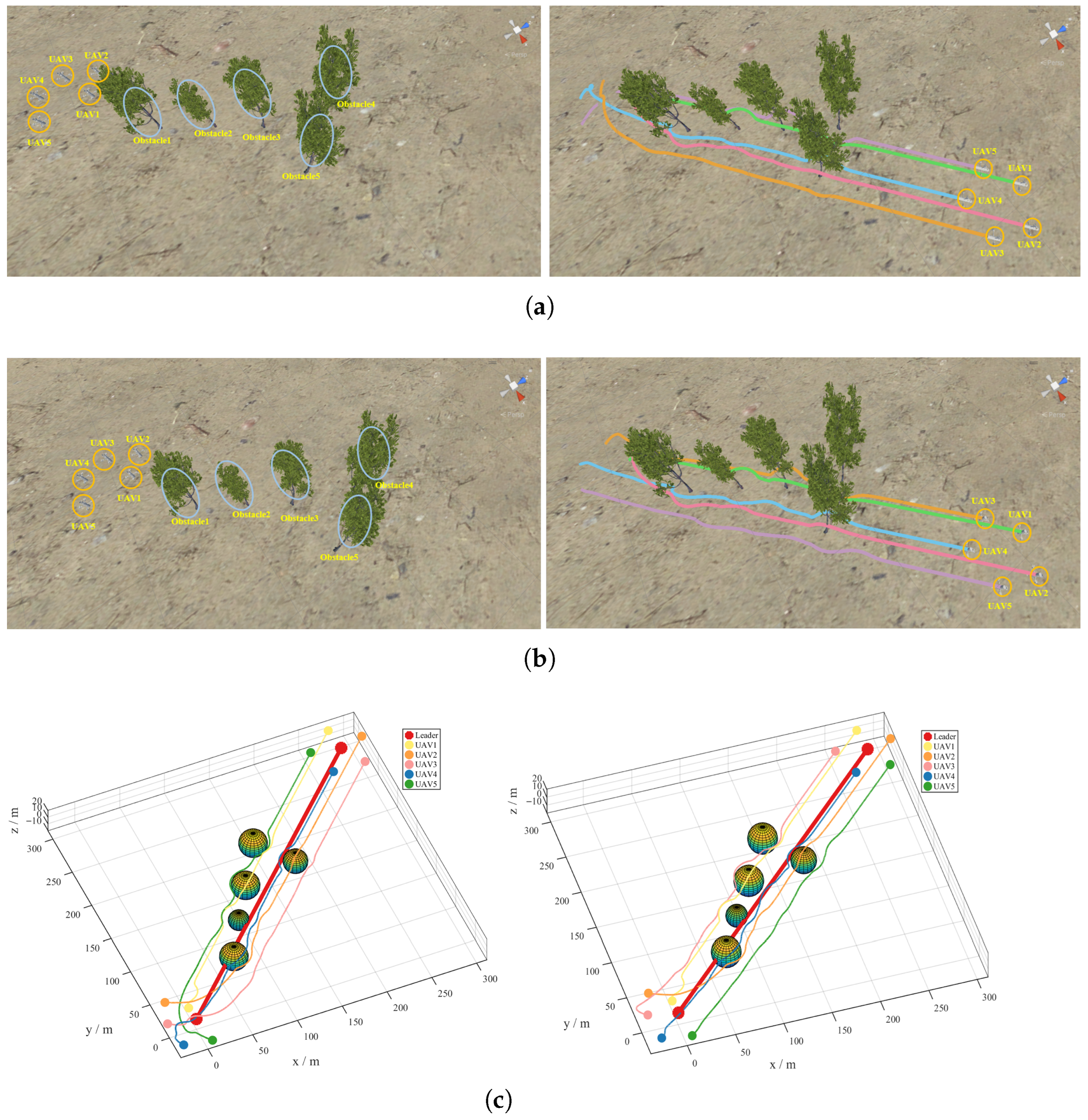

4.1. Rapid Formation and Obstacle Avoidance Performance Verification

4.2. HIL Experimental Validation

- Unity Simulation Environment: Real-time simulation of drone status, generating high-frequency simulated sensor data such as IMU and GPS readings.

- Sensor data is transmitted via UDP to the onboard RK3588 computer.

- The DPAF-SA algorithm on the onboard computer (functioning as both planner and advanced controller) receives and processes this data, calculating control commands (Control: setpoint/command velocity) in real time.

- Control commands are relayed back to the Unity host, driving updates to the drone’s state within the simulation environment, thereby forming a complete decision-perception-control closed-loop system.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Quero, C.O.; Martinez-Carranza, J. Unmanned aerial systems in search and rescue: A global perspective on current challenges and future applications. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2025, 118, 105199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Guo, Y.; Li, N.; Hu, S.; Wang, M. Autonomous collaborative combat strategy of unmanned system group in continuous dynamic environment based on PD-MADDPG. Comput. Commun. 2023, 200, 182–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, A.; Xiang, Z.; Chang, W.-J.; Aslam, M.S. Recent Advancement in Formation Control of Multi-Agent Systems A Review. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2025, 83, 3623–3674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Huang, K.; Liu, H.; Wang, R.; Cheng, G. Multi-Domain Collaborative Task Allocation and Conflict Resolution in Unmanned Systems under Complex Constraints. Unmanned Syst. 2025, 13, 579–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Bai, P.; Liang, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, W. Feedback formation control of UAV swarm with multiple implicit leaders. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2018, 72, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, K.; Wu, T. Distributed Consensus of USVs under Heterogeneous UAV-USV Multi-Agent Systems Cooperative Control Scheme. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, Z.; Tao, G.; Xu, Y.; Song, G. Multivariable adaptive control based consensus flight control system for UAVs formation. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2019, 93, 105336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Chi, H.; Jiang, G.P.; Wang, M.; Ren, Z. UAV Formation Cooperative Control Based on Consistency Theory. In Proceedings of the 2023 7th Chinese Conference on Swarm Intelligence and Cooperative Control, Nanjing, China, 24–27 November 2023; pp. 330–340. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, B.; Ji, Y.; Liyong, F. A Multi-UAV Formation Obstacle Avoidance Method Combined with Improved Simulated Annealing and an Adaptive Artificial Potential Field. Drones 2025, 9, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, X.; Wang, G.; Wu, S.; Li, W. Formation Obstacle Avoidance Control Method for Multi-Intelligent Firefighting Robots. Robotics 2024, 46, 81–93. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.; Ning, L. Coordinated Obstacle Avoidance of Multi-AUV Based on Improved Artificial Potential Field Method and Consistency Protocol. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Wang, Y.; Yan, Z.; Li, X.; Ren, Z. Event-triggered formation control with obstacle avoidance for multi-agent systems applied to multi-UAV formation flying. Control Eng. Pract. 2024, 153, 106105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Dai, J.; Ying, J. UAV Formation Obstacle Avoidance Control Algorithm Based on Improved Artificial Potential Field and Consensus. Int. J. Aeronaut. Space Sci. 2021, 22, 1413–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabsari, N.; Saif, A.W.A.; El-Ferik, S.; Duffuaa, S.; Derbel, N. Cooperative Flight Control of a Fleet of Quadrotors Using Fractional Sliding Mode With Potential Field Algorithms. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 24525–24543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saif, A.; Saif, A.-W.; Alabsari, N.; El Ferik, S.; Elshafei, M. Formation control of quadrotors via potential field and geometric techniques. Int. J. Adv. Appl. Sci. 2020, 7, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wang, X.; Yao, L.; Ren, Z. Formation configuration and communication topology optimization for fixed-wing UAVs. Syst. Eng. Electron. 2022, 44, 2936–2946. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Yan, J.; Zhang, P. Multi-UAV Formation Control Based on a Novel Back-Stepping Approach. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2020, 69, 2437–2448. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.; Liu, X. UAV Collision Avoidance Using Mixed-Integer Second-Order Cone Programming. J. Guid. Control Dyn. 2022, 45, 1732–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; He, H.; Wang, S.; Nie, C.; Jiao, Y. Joint Trajectory Planning for Multiple UAVs Target Tracking and Obstacle Avoidance in a Complicated Environment. Acta Armamentarii 2023, 44, 2685–2696. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Shan, M.; Wang, D. Motion Capability Analysis for Multiple Fixed-Wing UAV Formations With Speed and Heading Rate Constraints. IEEE Trans. Control Netw. Syst. 2020, 7, 977–989. [Google Scholar]

- Wrat, G.; Ranjan, P.; Mishra, S.K.; Jose, J.T.; Das, J. Neural network-enhanced internal leakage analysis for efficient fault detection in heavy machinery hydraulic actuator cylinders. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 2024, 239, 1021–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, R.; Beard, R.W. Distributed Consensus in Multi-Vehicle Cooperative Control; Springer: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, X.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, S. Multi-UAV simultaneous target assignment and path planning based on deep reinforcement learning in dynamic multiple obstacles environments. Front. Neurorobot. 2023, 17, 1302898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Wu, Y.L.; Xu, T.W. Application of improved genetic simulated annealing algorithm in TSP optimization. Control Decis. 2018, 33, 7. [Google Scholar]

| Symbol | Definitions |

|---|---|

| N | Number of UAVs |

| Position vector of the i-th UAV | |

| Velocity Vector for the i-th UAV | |

| Communication Adjacency Matrix | |

| Minimum Safe Distance | |

| Maximum Velocity | |

| Maximum Acceleration | |

| Control Input for UAV i | |

| Upper Bound of Position Error | |

| S | Expected Formation Slot Grouping |

| UAV-Slot Allocation Mapping | |

| Obstacle Set | |

| Virtual Pilot Center Position | |

| Safe Distance for UAV Obstacle Avoidance | |

| UAV radius |

| Symbol | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| N | 8 | Number of UAVs |

| (3, 3, 0) m/s | Navigator Speed | |

| 1 m | Minimum Safe Distance | |

| 0.06 m | UAV radius | |

| 100 | Inner loop iteration count | |

| 500 | Initial temperature | |

| k | 0.95 | Annealing coefficient |

| Serial Number | Start Point (m) |

|---|---|

| UAV1 | 20, −50, 20 |

| UAV2 | 70, −50, 40 |

| UAV3 | −60, −10, 60 |

| UAV4 | −60, −60, 20 |

| UAV5 | −10, 70, 10 |

| UAV6 | −60, 60, 50 |

| UAV7 | 80, 25, 60 |

| UAV8 | 30, 30, 70 |

| Serial Number | Start Point (m) |

|---|---|

| UAV1 | 0, 30, 20 |

| UAV2 | −30, 30, 40 |

| UAV3 | −30, −0, 60 |

| UAV4 | −30, 30, 20 |

| UAV5 | 0, 30, 10 |

| UAV6 | 30, −30, 50 |

| UAV7 | 30, 0, 6 |

| UAV8 | 30, 30, 70 |

| Metric | Method | Sample Mean | Standard Deviation | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F_RMSE | DPAF-SA | 0.812 | 0.243 | [0.721, 0.903] |

| F_RMSE | HD | 1.492 | 1.492 | [1.312, 1.672] |

| D_Min | DPAF-SA | 3.139 | 0.622 | [2.906, 3.372] |

| D_Min | HD | 2.268 | 0.852 | [1.949, 2.587] |

| T_Conv | DPAF-SA | 39.785 | 1.341 | [39.290, 40.290] |

| T_Conv | HD | 37.750 | 1.748 | [37.090, 38.410] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, M.; Hao, Y.; Yang, L. DPAF-SA: A Formation Control Algorithm for Dynamic Allocation and Fusion of Potential Fields for UAV Swarms. Electronics 2026, 15, 257. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020257

Li M, Hao Y, Yang L. DPAF-SA: A Formation Control Algorithm for Dynamic Allocation and Fusion of Potential Fields for UAV Swarms. Electronics. 2026; 15(2):257. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020257

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Meixuan, Yongping Hao, and Liyuan Yang. 2026. "DPAF-SA: A Formation Control Algorithm for Dynamic Allocation and Fusion of Potential Fields for UAV Swarms" Electronics 15, no. 2: 257. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020257

APA StyleLi, M., Hao, Y., & Yang, L. (2026). DPAF-SA: A Formation Control Algorithm for Dynamic Allocation and Fusion of Potential Fields for UAV Swarms. Electronics, 15(2), 257. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020257