Adaptive Fault Diagnosis of DC-DC Boost Converters in Photovoltaic Systems Based on Sliding Mode Observers with Dynamic Thresholds

Abstract

1. Introduction

- The development of an ASMO for robust state and parameter estimation in the presence of model uncertainties and external disturbances.

- The design of an adaptive threshold mechanism that dynamically adjusts to operating conditions, significantly reducing false alarms, and improving detection reliability.

- A comprehensive stability analysis using Lyapunov theory to guarantee the convergence and performance of the proposed observer.

- The validation under multiple fault scenarios and varying environmental conditions.

2. System Modeling

2.1. PV Generator Model

2.2. DC-DC Boost Converter Model

2.2.1. Fault Free Model

2.2.2. Faulty Model

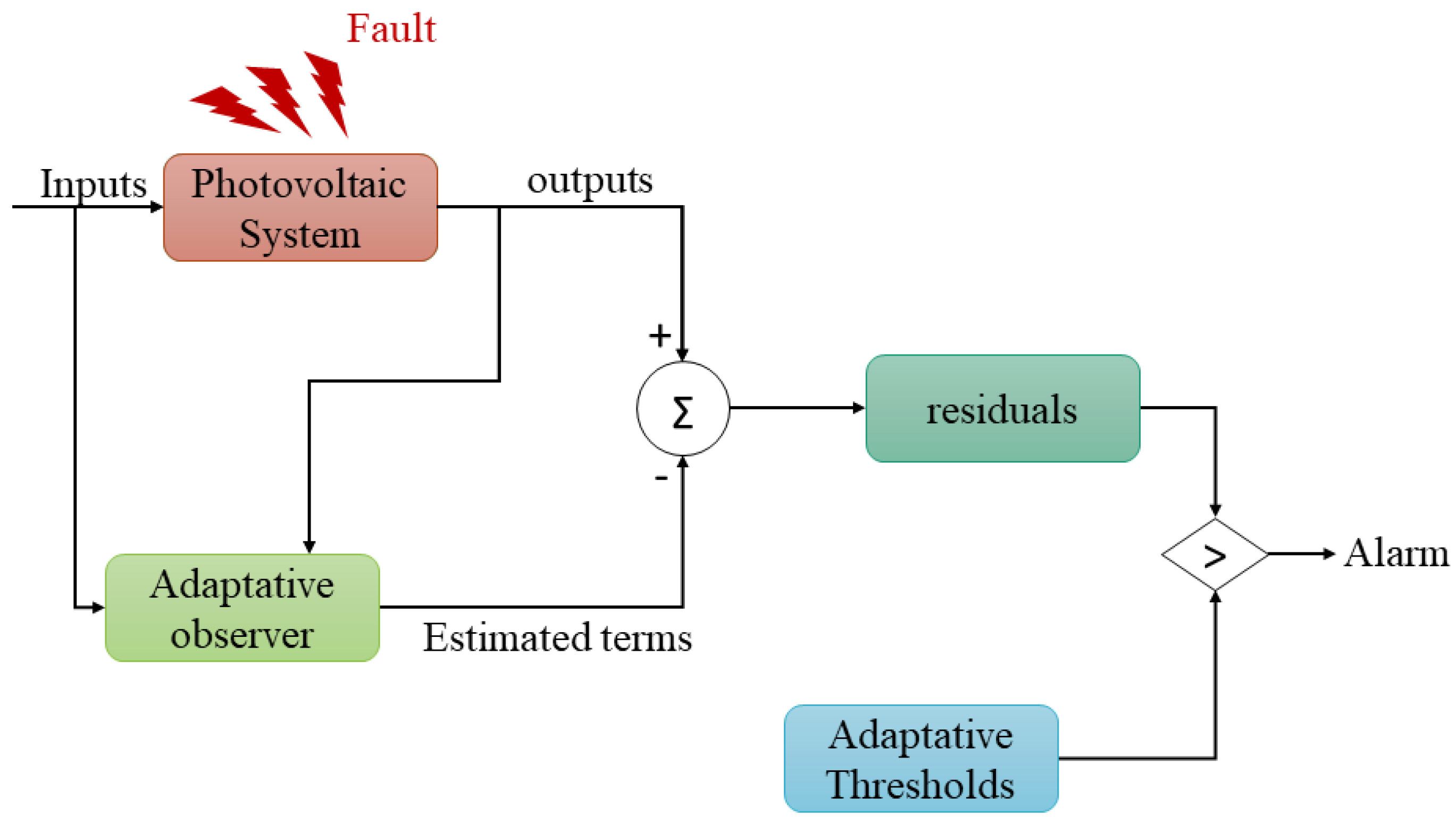

3. Design of the Fault Diagnostic Scheme

3.1. Adaptive Sliding Mode Observer Design

3.2. Stability Analysis

4. Adaptive Thresholds

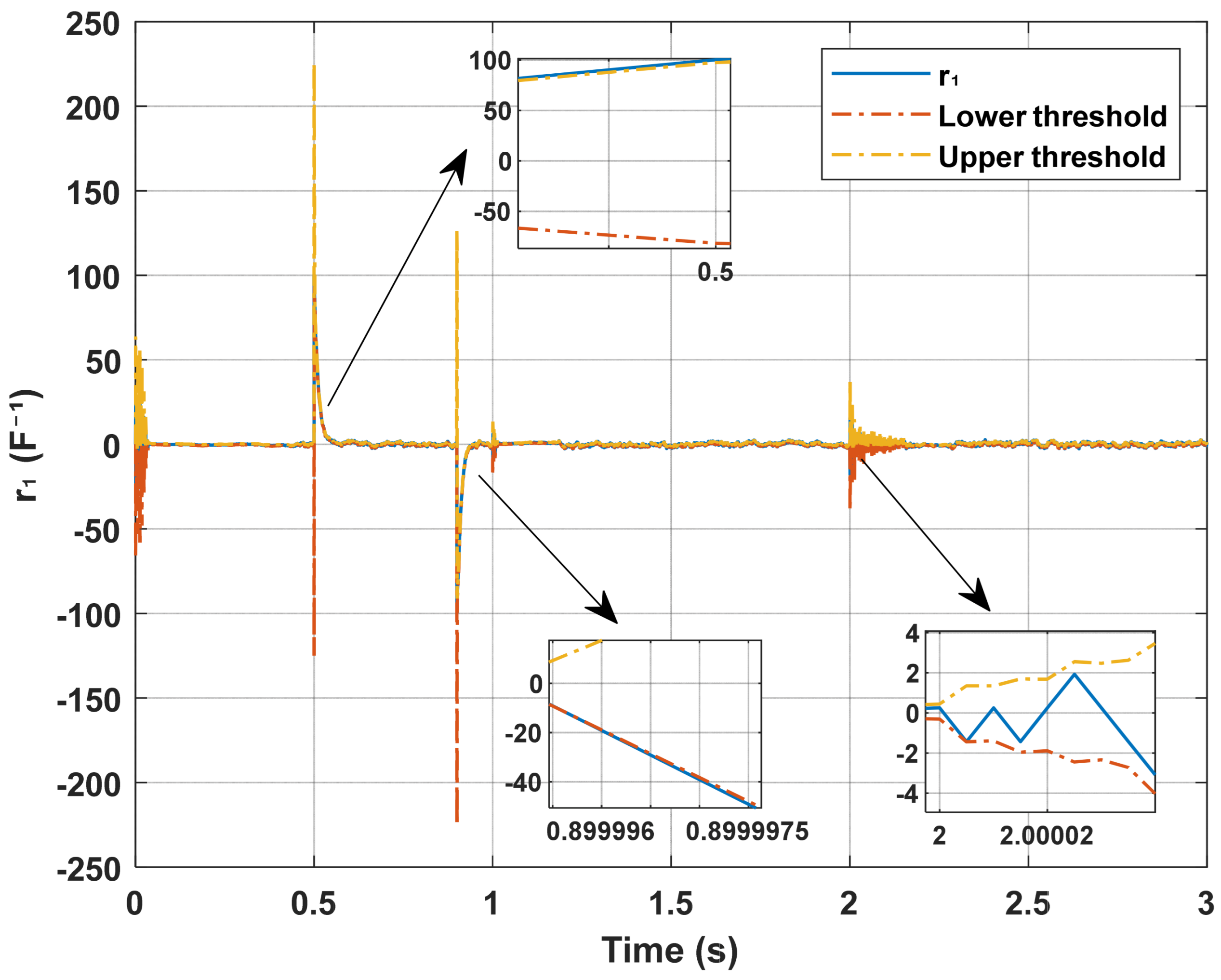

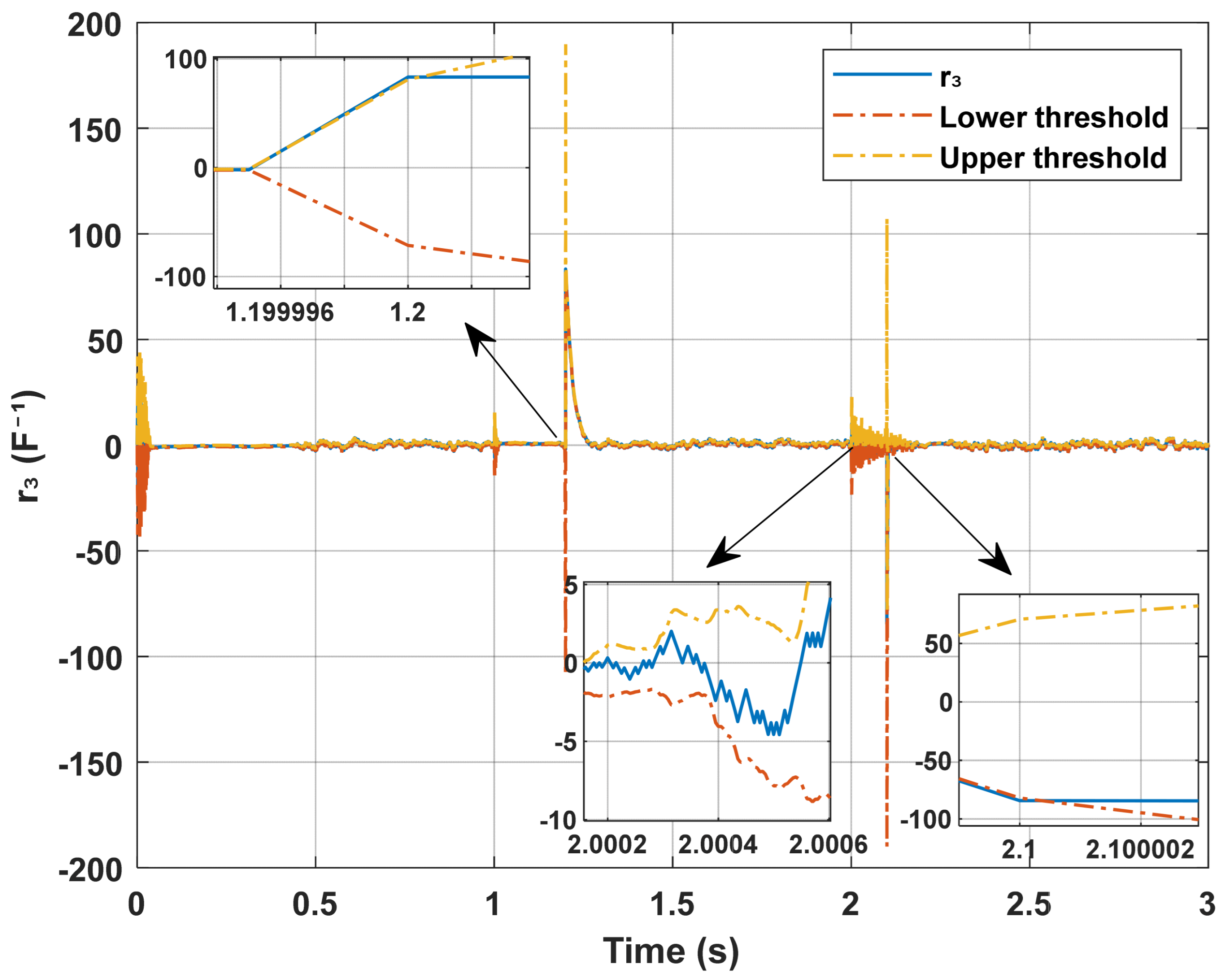

5. Simulation Results and Analysis

5.1. Comparative Analysis with a Standard Sliding Mode Observer

5.2. Analysis of Observer Gains

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mariani, V.; Adinolfi, G.; Buonanno, A.; Ciavarella, R.; Ricca, A.; Sorrentino, V.; Graditi, G.; Valenti, M. A Survey on Anomalies and Faults That May Impact the Reliability of Renewable-Based Power Systems. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molęda, M.; Małysiak-Mrozek, B.; Ding, W.; Sunderam, V.; Mrozek, D. From Corrective to Predictive Maintenance—A Review of Maintenance Approaches for the Power Industry. Sensors 2023, 23, 5970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pourshahbaz, N.; Eskandari, A.; Milimonfared, J.; Aghaei, M. Current-Based Fault Detection of Photovoltaic Systems. In Proceedings of the 2023 14th Power Electronics, Drive Systems, and Technologies Conference (PEDSTC), Babol, Iran, 31 January–2 February 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Briceño, C.; Ponce, P.; Mei, Q.; Fayek, A.R. A Type-2 Fuzzy Logic Expert System for AI Selection in Solar Photovoltaic Applications Based on Data and Literature-Driven Decision Framework. Processes 2025, 13, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.S.; Wen, H. A Comprehensive Review of Fault Diagnosis and Tolerant Control in DC-DC Converters for DC Microgrids. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 80100–80127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipu, M.S.H.; Faisal, M.; Ansari, S.; Hannan, M.A.; Karim, T.F.; Ayob, A.; Hussain, A.; Miah, M.S.; Saad, M.H.M. Review of Electric Vehicle Converter Configurations, Control Schemes and Optimizations: Challenges and Suggestions. Electronics 2021, 10, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarig, E.; Evzelman, M.; Peretz, M.M. Analog Frontend for Big Data Compression and Instantaneous Failure Prediction in Power Management Systems. Electronics 2025, 14, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhang, L. A Deploying Method for Predicting the Size and Optimizing the Location of an Electric Vehicle Charging Stations. Information 2018, 9, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokoohi, S.; Moshtagh, J. Beyond Signal Processing: A Model-Based Luenberger Observer Approach for Accurate Bearing Fault Diagnosis. AUT J. Electr. Eng. 2024, 57, 163–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arena, F.; Collotta, M.; Luca, L.; Ruggieri, M.; Termine, F.G. Predictive Maintenance in the Automotive Sector: A Literature Review. MCA 2021, 27, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givi, H.; Farjah, E.; Ghanbari, T. A Comprehensive Monitoring System for Online Fault Diagnosis and Aging Detection of Non-Isolated DC–DC Converters’ Components. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2019, 34, 6858–6875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Chen, S.; Lin, C.-M. Parametric Fault Diagnosis Based on Fuzzy Cerebellar Model Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2019, 66, 8104–8115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkateswaran, M.; Govindaraju, C.; Santhosh, T.K. Integrated Predictive Control and Fault Diagnosis Algorithm for Single Inductor-Based DC-DC Converters for Photovoltaic Systems. Circuit World 2020, 47, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalina, B.S.; Kamaraj, V.; Babu, M.R. Fault Detection and Identification Strategy Based on Luenberger Observer for Bidirectional Interleaved Switched—Capacitor DC–DC Converter Interfaced Microgrids. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2022, 17, 2329–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, T.; Maruta, H. Parameter Estimation of DC-DC Converters for Failure Detection Based on Linear Approximation Model. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 30th International Symposium on Industrial Electronics (ISIE), Kyoto, Japan, 20 June 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Vinod; Kumar, R.; Singh, S.K. Solar Photovoltaic Modeling and Simulation: As a Renewable Energy Solution. Energy Rep. 2018, 4, 701–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borja-Jaimes, V.; Adam-Medina, M.; López-Zapata, B.Y.; Vela Valdés, L.G.; Claudio Pachecano, L.; Sánchez Coronado, E.M. Sliding Mode Observer-Based Fault Detection and Isolation Approach for a Wind Turbine Benchmark. Processes 2021, 10, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahraoui, H.; Mellah, H.; Mouassa, S.; Jurado, F.; Bessaad, T. Lyapunov-Based Adaptive Sliding Mode Control of DC–DC Boost Converters Under Parametric Uncertainties. Machines 2025, 13, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Yang, J.; Liang, F.; Li, M.; Wang, F. An Adaptive Threshold Strategy Based on Empirical Distribution Functions and Information Entropy for Battery Abnormal Diagnosis and Fault Alarm. Energy 2025, 332, 135980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lyu, M.; Gao, X.; Yuan, C.; Zhen, D. An Adaptive Threshold Method for Multi-Faults Diagnosis of Lithium-Ion Batteries Based on Electro-Thermal Model. Measurement 2023, 222, 113671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attar, A.A.; Fabarisov, T.; Hagenmeyer, V.; Morozov, A. Improving Anomaly Detection with Adaptive Dynamic Threshold: A Review and Enhanced Method. In Proceedings of the 2024 8th International Conference on System Reliability and Safety (ICSRS), Sicily, Italy, 20–22 November 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, H.; Ismail, M.; Saeed, N. New Extended Exponentially Weighted Moving Average Control Chart for Monitoring Process Mean. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameters | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Voltage at the maximum power point | Vmax | 27 V |

| current at the maximum power point | Imax | 7.6 A |

| Maximum power | Pmax | 210 W |

| Open circuit voltage | Voc | 32.9 V |

| Short circuit current | Isc | 8.21 A |

| Input capacitor | C1 | 10−3 F |

| Output capacitor | C2 | 10−3 F |

| Inductor | L | 1.21 × 10−3 H |

| Load | R | 25 Ω |

| Symbol | Value |

|---|---|

| K1 | 50 V/s |

| K2 | 100 A/s |

| K3 | 500 V/s |

| Γ1 | 106 1/F.A.s |

| Γ2 | 106 1/H.V.s |

| Γ3 | 106 1/F.A.s |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ismail, M.; Dahech, K.; Tadeo, F.; Damak, T.; Chaabane, M. Adaptive Fault Diagnosis of DC-DC Boost Converters in Photovoltaic Systems Based on Sliding Mode Observers with Dynamic Thresholds. Electronics 2026, 15, 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010040

Ismail M, Dahech K, Tadeo F, Damak T, Chaabane M. Adaptive Fault Diagnosis of DC-DC Boost Converters in Photovoltaic Systems Based on Sliding Mode Observers with Dynamic Thresholds. Electronics. 2026; 15(1):40. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010040

Chicago/Turabian StyleIsmail, Maouadda, Karim Dahech, Fernando Tadeo, Tarak Damak, and Mohamed Chaabane. 2026. "Adaptive Fault Diagnosis of DC-DC Boost Converters in Photovoltaic Systems Based on Sliding Mode Observers with Dynamic Thresholds" Electronics 15, no. 1: 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010040

APA StyleIsmail, M., Dahech, K., Tadeo, F., Damak, T., & Chaabane, M. (2026). Adaptive Fault Diagnosis of DC-DC Boost Converters in Photovoltaic Systems Based on Sliding Mode Observers with Dynamic Thresholds. Electronics, 15(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010040