Determining the Origin of Multi Socket Fires Using YOLO Image Detection

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We create a novel dataset with annotations in PASCAL VOC of post-fire multi-socket outlets with 3300 images, including three categories: “socket”, “burnt-in”, and “burnt-out”.

- We verify the feasibility of YOLO-based deep learning models, i.e., YOLOv4-csp, YOLOv5n, YOLOR-csp, YOLOv6n, and YOLOv7-Tiny for the classification task of identifying fire-causing reasons (internal as “burnt-in” versus external as “burnt-out” sources) in multi-socket outlets.

- We propose an improved version of the conventional YOLOv5n by adding squeeze-and-excitation networks (SENet) into the existing YOLOv5 backbone, following a two-stage detector architecture instead of a one-stage detector, including a first stage of socket detection and a second stage of fire-causing classification into either the burnt-in or burnt-out categories.

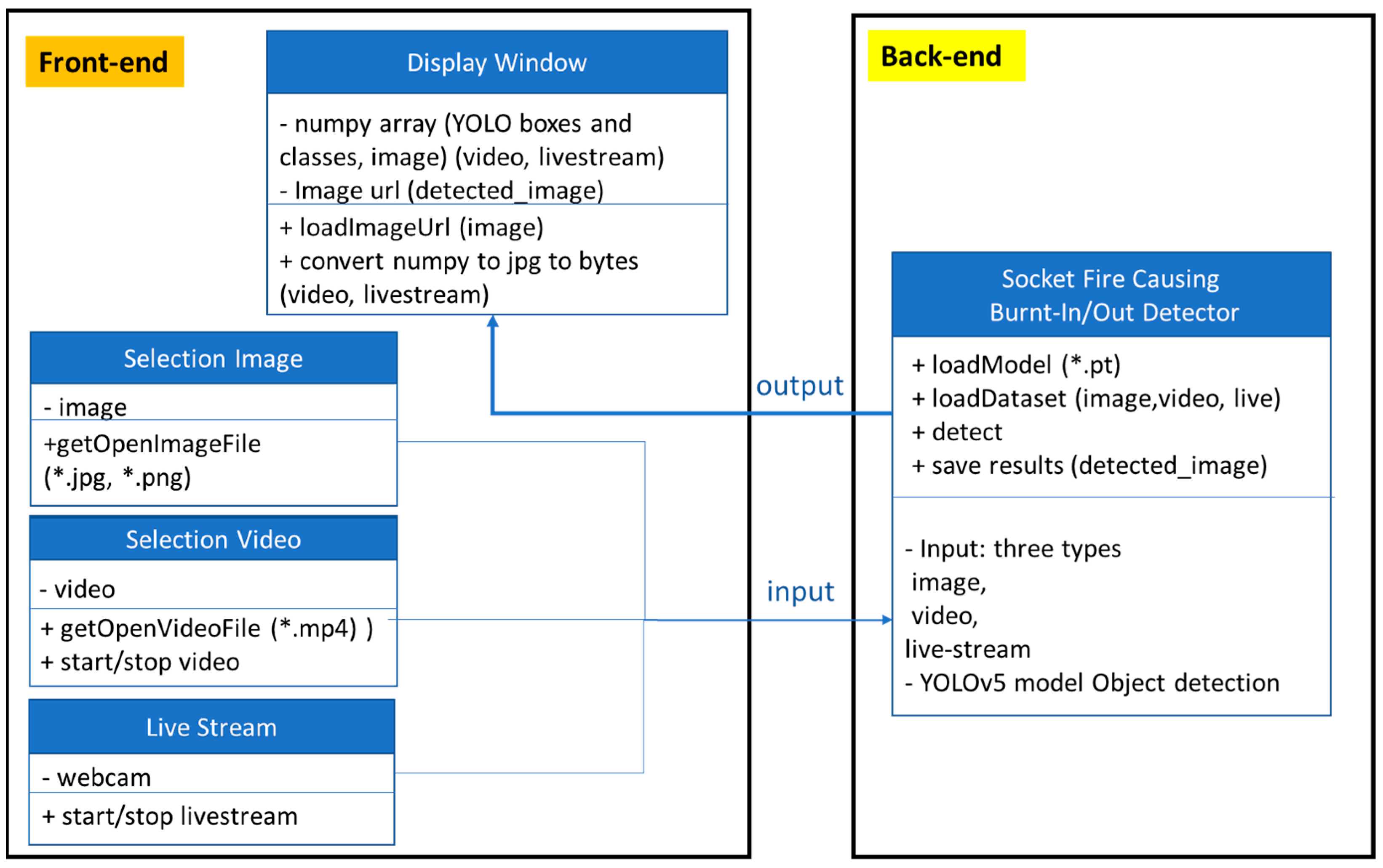

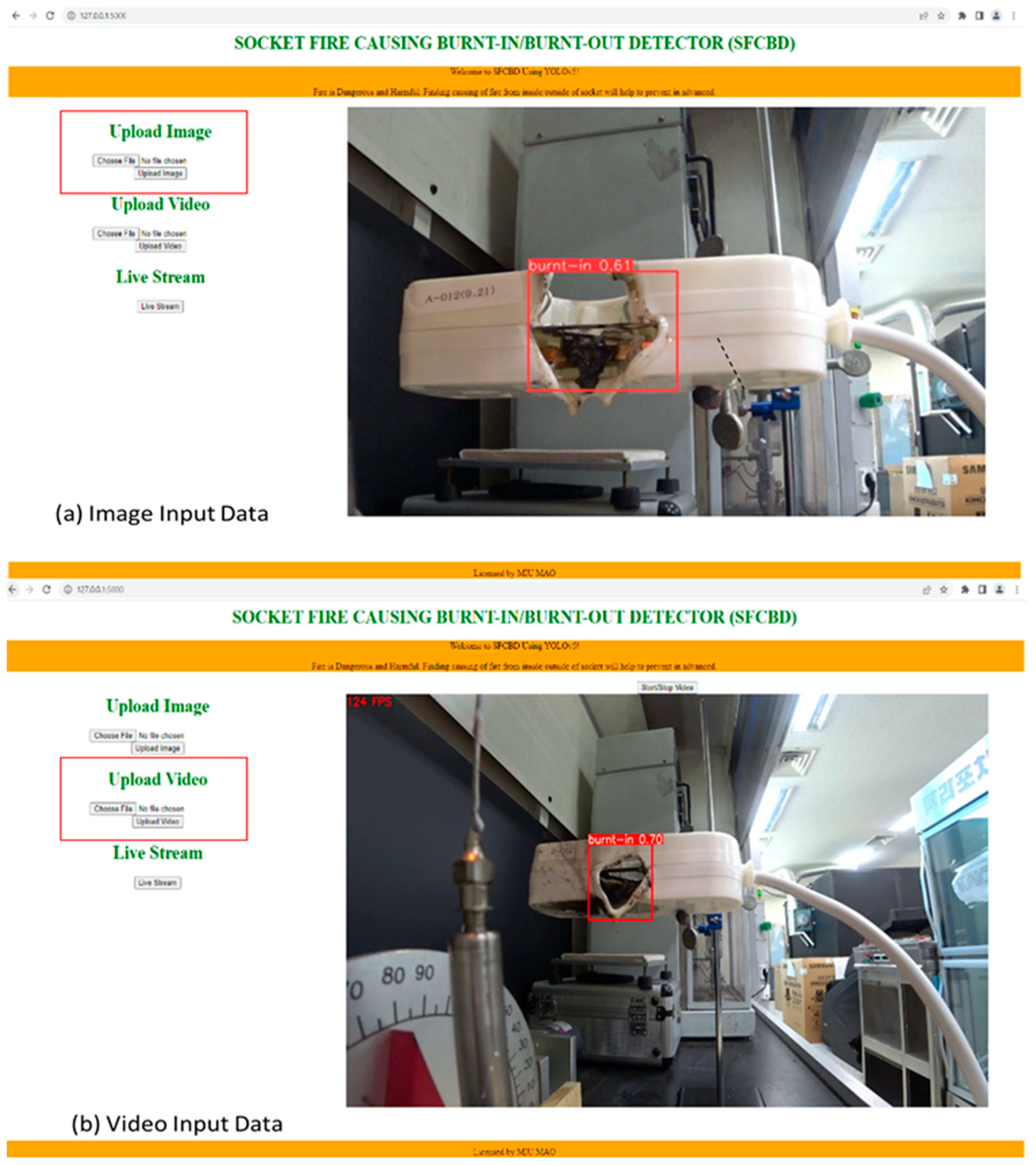

- We deploy trained YOLO weights on stand-alone web browser applications.

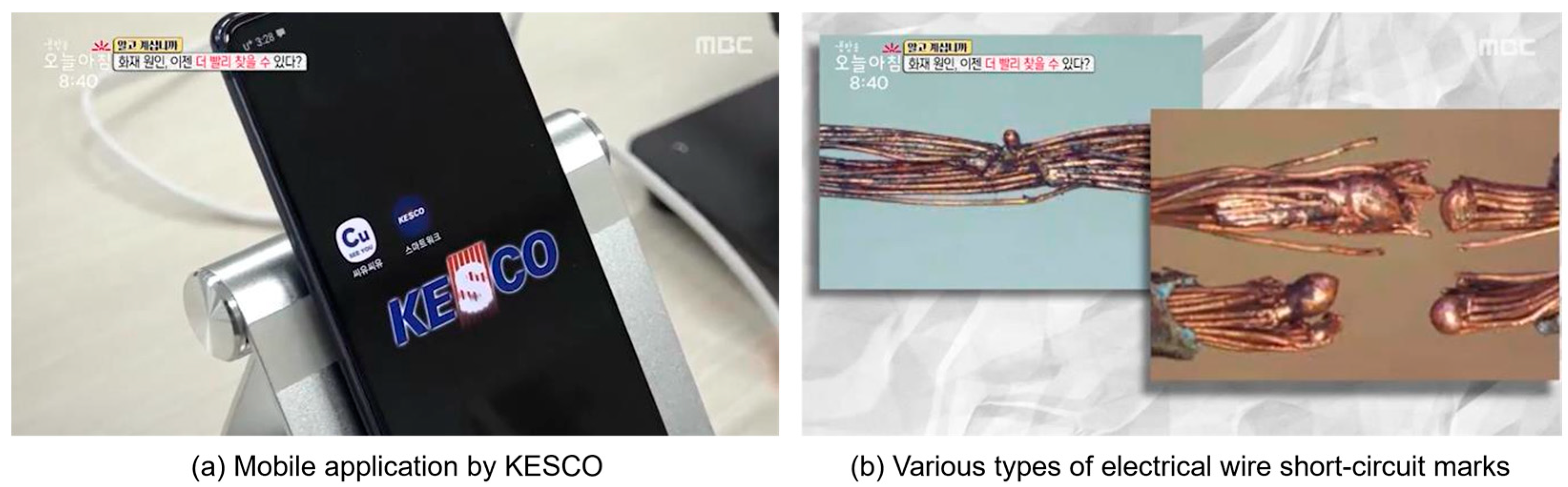

2. Related Research

3. Research Methodology

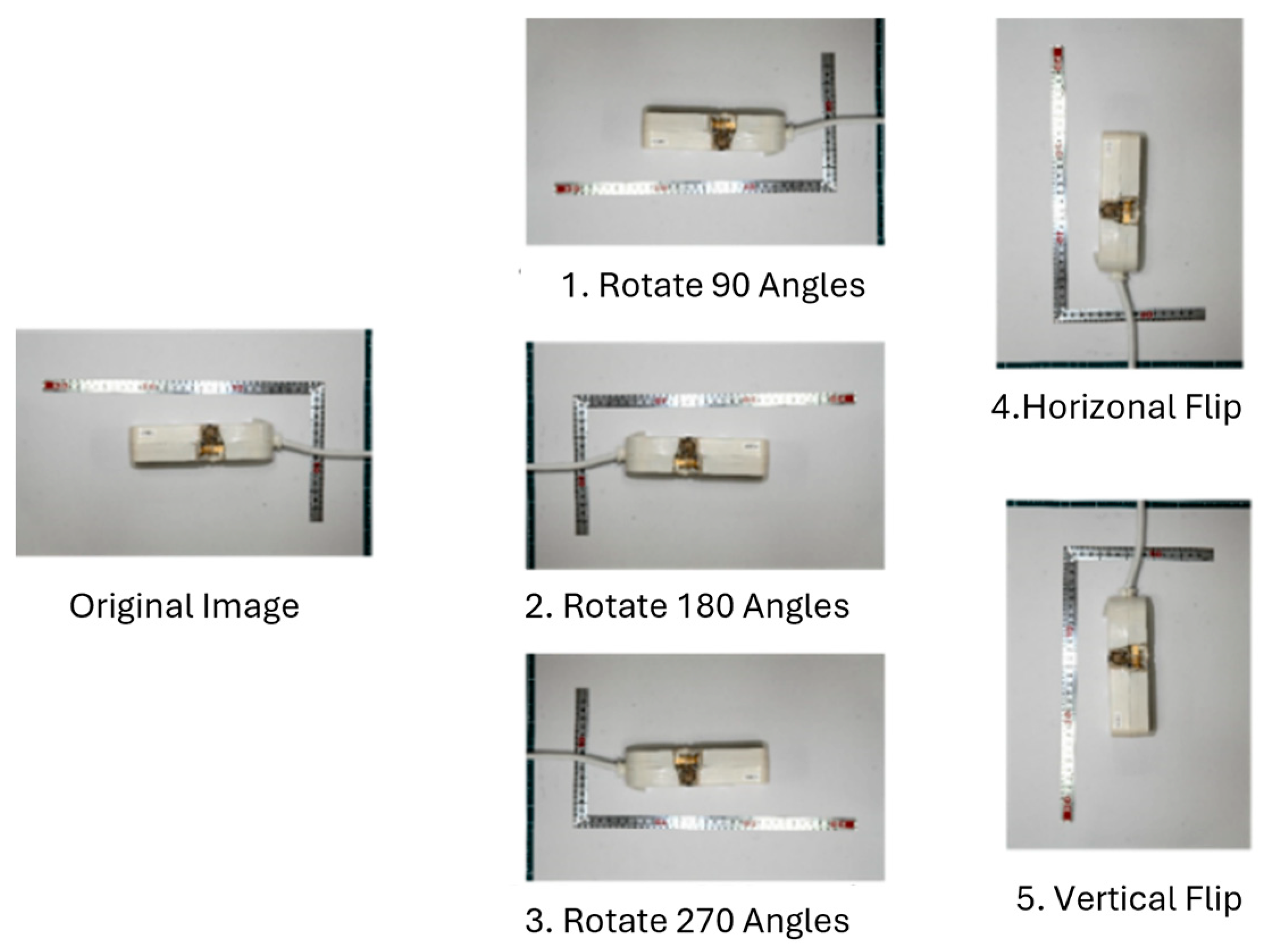

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. YOLO-Based Deep Learning Models

3.2.1. Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks (SENet)

3.2.2. Two-Stage Detector

| Algorithm 1: Two-stage detection |

| In: input source (images, videos), : YOLOv5-SE model weights Out: : prediction of socket (S), burnt-in (I) and burnt-out (O)bounding boxes

|

3.3. Web-Browser Application Deployment

4. Experiment and Analysis

4.1. Experiment Setup

4.2. Experiment Results

4.3. Ablation Study

4.4. Analysis

4.4.1. Epochs Versus Overfitting

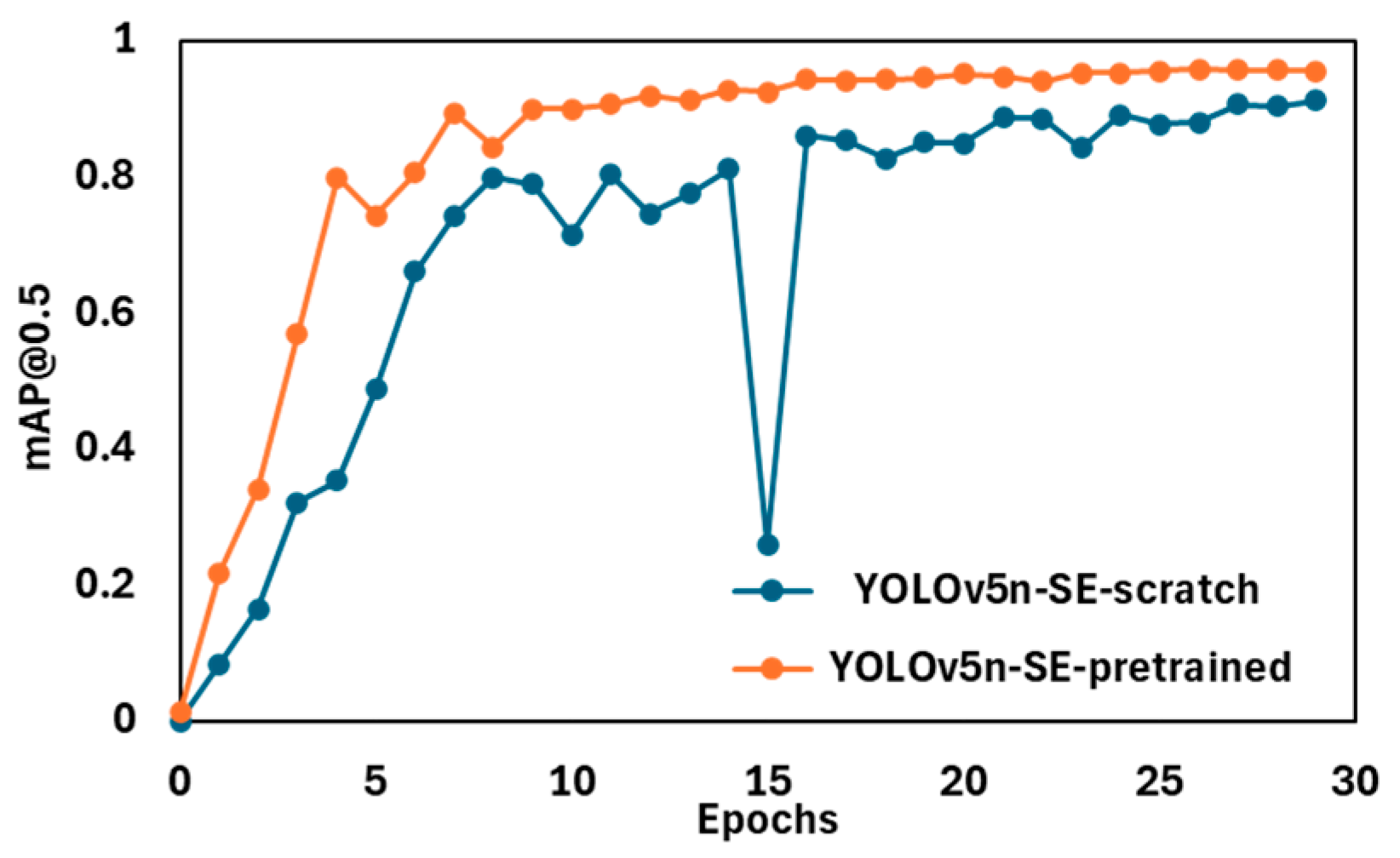

4.4.2. Transfer Learning with a Pre-Trained Model Versus Training from Scratch

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, H.-G.; Lee, J.-H.; Pham, T.-N.; Huh, J.-H. A Study on the Deposition Removal Technique Based on the Carbonization Morphology of Injection Molding Residue (Fundamental); Research Report; National Fire Research Institute of Korea, Fire Safety Research Division, Fire Research Institute of Korea: Hwaseong-si, Republic of Korea, 2023; pp. 1–118. (In Korean)

- Jo, J.H.; Bang, J.; Yoo, J.; Sun, R.; Hong, S.; Bang, S.B. A CNN Algorithm Suitable for the Classification of Primary and Secondary Arc-bead and Molten Mark Using Laboratory Data for Cause Analysis of Electric Fires. Trans. Korean Inst. Electr. Eng. 2021, 70, 1750–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Bang, J.; Kim, J.H.; So, B.M.; Song, J.H.; Park, K.M. A Study on the Comparative Analysis of the Performance of CNN-Based Algorithms for the Determination of Arc Beads and Molten Mark by Model. J. Next-Gener. Converg. Technol. Assoc. 2023, 7, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Kim, S.; Kim, G. Analysis of Thermal Characteristics of Electrical Outlets Due to Overcurrent. J. Korean Soc. Saf. 2019, 34, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, Z.; Chen, K.; Shi, Z.; Guo, Y.; Ye, J. Object Detection in 20 Years: A Survey. Proc. IEEE 2023, 111, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You Only Look Once: Unified Real-Time Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 26 June–1 July 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Bochkovskiy, A.; Wang, C.Y.; Liao, H.Y.M. YOLOv4: Optimal Speed and Accuracy of Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Virtual Event, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.Y.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Liao, H. Scaled-YOLOv4: Scaling Cross Stage Partial Network. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 13024–13033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Yeh, I.H.; Liao, H.Y.M. You Only Learn One Representation: Unified Network for Multiple Tasks. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2105.04206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jocher, G. YOLOv5. 2020. Available online: https://github.com/ultralytics/yolov5 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Li, C.; Li, L.; Jiang, H.; Weng, K.; Geng, Y.; Li, L.; Ke, Z.; Li, Q.; Cheng, M.; Nie, W.; et al. YOLOv6: A Single-Stage Object Detection Framework for Industrial Applications. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.02976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Liao, H.Y.M. YOLOv7: Trainable Bag-of-Freebies Sets New State-of-the-Art for Real-Time Object Detectors. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 7464–7475. [Google Scholar]

- Girshick, R.; Donahue, J.; Darrell, T.; Malik, J. Rich Feature Hierarchies for Accurate Object Detection and Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; pp. 580–587. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Hopkins, B.; Wang, H.; O’nEill, L.; Afghah, F.; Razi, A.; Fulé, P.; Coen, J.; Rowell, E.; Watts, A. Wildland Fire Detection and Monitoring Using a Drone-Collected RGB/IR Image Dataset. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 121301–121317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, K.; Ahmad, J.; Lv, Z.; Bellavista, P.; Yang, P.; Baik, S.W. Efficient Deep CNN-Based Fire Detection and Localization in Video Surveillance Applications. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2019, 49, 1419–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NtHppN7YmZM (accessed on 1 November 2025). (In Korean).

- Szegedy, C.; Liu, W.; Jia, Y.; Sermanet, P.; Reed, S.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Vanhoucke, V.; Rabinovich, A.; Liu, W.; et al. Going Deeper with Convolutions. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Szegedy, C.; Ioffe, S.; Vanhoucke, V.; Alemi, A.A. Inception-v4, Inception-ResNet and the Impact of Residual Connections on Learning. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2019, 30, 2354–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://github.com/tzutalin/labelImg/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 7132–7141. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://imgaug.readthedocs.io/en/latest/index.html (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Lin, T.Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Dollár, P.; Zitnick, C.L. Microsoft COCO: Common Objects in Context. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2014: 13th European Conference, Zurich, Switzerland, 6–12 September 2014; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 740–755. [Google Scholar]

- YOLOv4-csp. Available online: https://github.com/WongKinYiu/ScaledYOLOv4 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- YOLOR-csp. Available online: https://github.com/WongKinYiu/yolor (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- YOLOv6n. Available online: https://github.com/meituan/YOLOv6 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- YOLOv7-Tiny. Available online: https://github.com/WongKinYiu/yolov7 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Hou, Q.; Zhou, D.; Feng, J. Coordinate Attention for Efficient Mobile Network Design. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 13708–13717. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kweon, I.S. CBAM: Convolutional Block Attention Module. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Wu, B.; Zhu, P.; Li, P.; Zuo, W.; Hu, Q. ECA-Net: Efficient Channel Attention for Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 11531–11539. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, D.; Liu, Y.; Liu, G.; Wang, N.; Chen, P.; Yu, J.; Liang, G. YOLOv7scb: A Small-Target Object Detection Method for Fire Smoke Inspection. Fire 2025, 8, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Xu, Z.; Yue, Q.; Lin, J.; Zhang, N.; Zhao, Y.; Gu, D. A multi-object detection method for building fire warnings through artificial intelligence generated content. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 18434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Fu, X.; Yu, Z.; Zeng, Z. DSS-YOLO: An improved lightweight real-time fire detection model based on YOLOv8. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Z.; Xu, H.; Xing, Y.; Zhu, C.; Jiao, Z.; Cui, C. YOLO-UFS: A Novel Detection Model for UAVs to Detect Early Forest Fires. Forests 2025, 16, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Cao, Y.; Sun, Y.; Tang, T. Railway Automatic Switch Stationary Contacts Wear Detection Under Few-Shot Occasions. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 14893–14907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dataset | Images | Labels | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burnt-in | Burnt-Out | Socket | |||

| EIFCD | 3300 | Training: 2640 | 963 | 1017 | 2640 |

| (our dataset) | Validation: 660 | 357 | 303 | 660 | |

| Models | Paras(M) | FLOPs(G) | AP@0.5 | mAP @0.5 | mAP @0.5:0.95 | P | R | F1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socket | Burnt-in | Burnt-Out | ||||||||

| YOLOv4-csp | 2.29 | 5.4 | 88.1 | 44.4 | 62.9 | 65.4 | 33.6 | 64.3 | 67.4 | 65 |

| YOLOv5n | 1.76 | 4.1 | 99.0 | 64.1 | 85.6 | 82.9 | 46.0 | 82.8 | 79.0 | 81 |

| YOLOR-cps | 2.29 | 11.3 | 98.6 | 61.7 | 83.7 | 81.3 | 46.6 | 79.9 | 81.0 | 80 |

| YOLOv6n | 4.63 | 11.3 | 99.3 | 73.4 | 90.7 | 87.8 | 55.4 | 86.3 | 82.3 | 84 |

| YOLOv7-Tiny | 6.02 | 13.2 | 99.1 | 91.7 | 74.8 | 88.5 | 52.6 | 88.3 | 87.6 | 88 |

| This work | 1.80 | 4.2 | 98.7 | 80.7 | 94.4 | 91.3 | 55.5 | 91.2 | 87.0 | 89 |

| Models | Paras (M) | FLOPs (G) | mAP @0.5 | P | R | F1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv5n | 1.76 | 4.1 | 82.9 | 82.8 | 79.0 | 81 |

| w/two-stage detector | 1.76 | 4.1 | 90.4 | 90.1 | 86.9 | 88 |

| w/CA+ two-stage detector | 1.81 | 4.2 | 91.0 | 90.4 | 87.0 | 89 |

| w/CBAM+ two-stage detector | 1.81 | 4.2 | 91.0 | 91.8 | 87.1 | 89 |

| w/ECA+ two-stage detector | 1.80 | 4.2 | 89.9 | 90.3 | 87.0 | 89 |

| w/SE+ two-stage detector | 1.80 | 4.2 | 91.3 | 91.2 | 87.0 | 89 |

| w/SE+ two-stage detector + transfer learning | 1.80 | 4.2 | 95.6 | 95.5 | 91.9 | 94 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lee, H.-G.; Pham, T.-N.; Nguyen, V.-H.; Kwon, K.-R.; Huh, J.-H.; Lee, J.-H.; Liu, Y. Determining the Origin of Multi Socket Fires Using YOLO Image Detection. Electronics 2026, 15, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010022

Lee H-G, Pham T-N, Nguyen V-H, Kwon K-R, Huh J-H, Lee J-H, Liu Y. Determining the Origin of Multi Socket Fires Using YOLO Image Detection. Electronics. 2026; 15(1):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010022

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Hoon-Gi, Thi-Ngot Pham, Viet-Hoan Nguyen, Ki-Ryong Kwon, Jun-Ho Huh, Jae-Hun Lee, and YuanYuan Liu. 2026. "Determining the Origin of Multi Socket Fires Using YOLO Image Detection" Electronics 15, no. 1: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010022

APA StyleLee, H.-G., Pham, T.-N., Nguyen, V.-H., Kwon, K.-R., Huh, J.-H., Lee, J.-H., & Liu, Y. (2026). Determining the Origin of Multi Socket Fires Using YOLO Image Detection. Electronics, 15(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010022