Feature Selection and Fault Detection Under Dynamic Conditions of Chiller Systems

Abstract

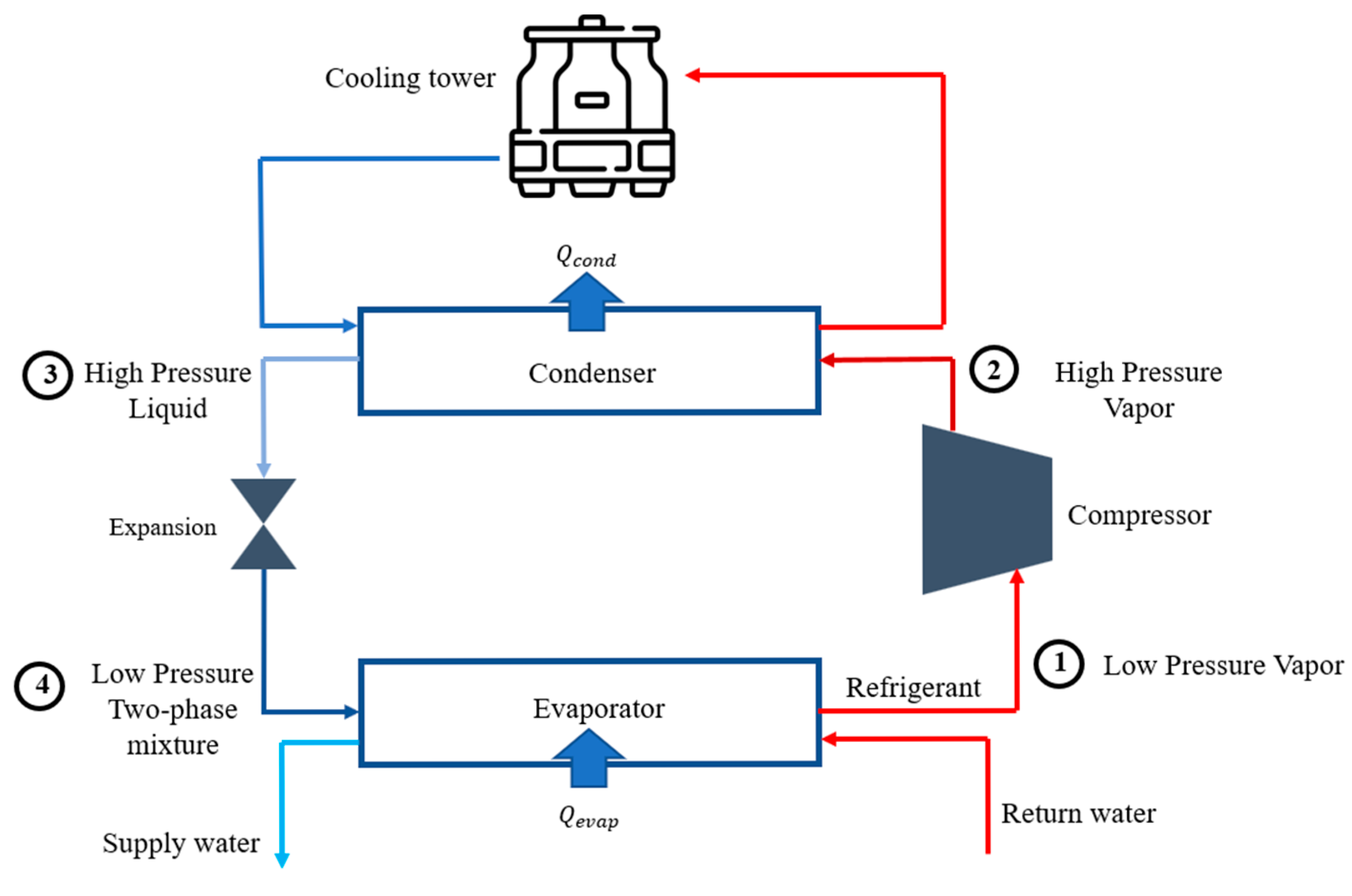

1. Introduction

- (1)

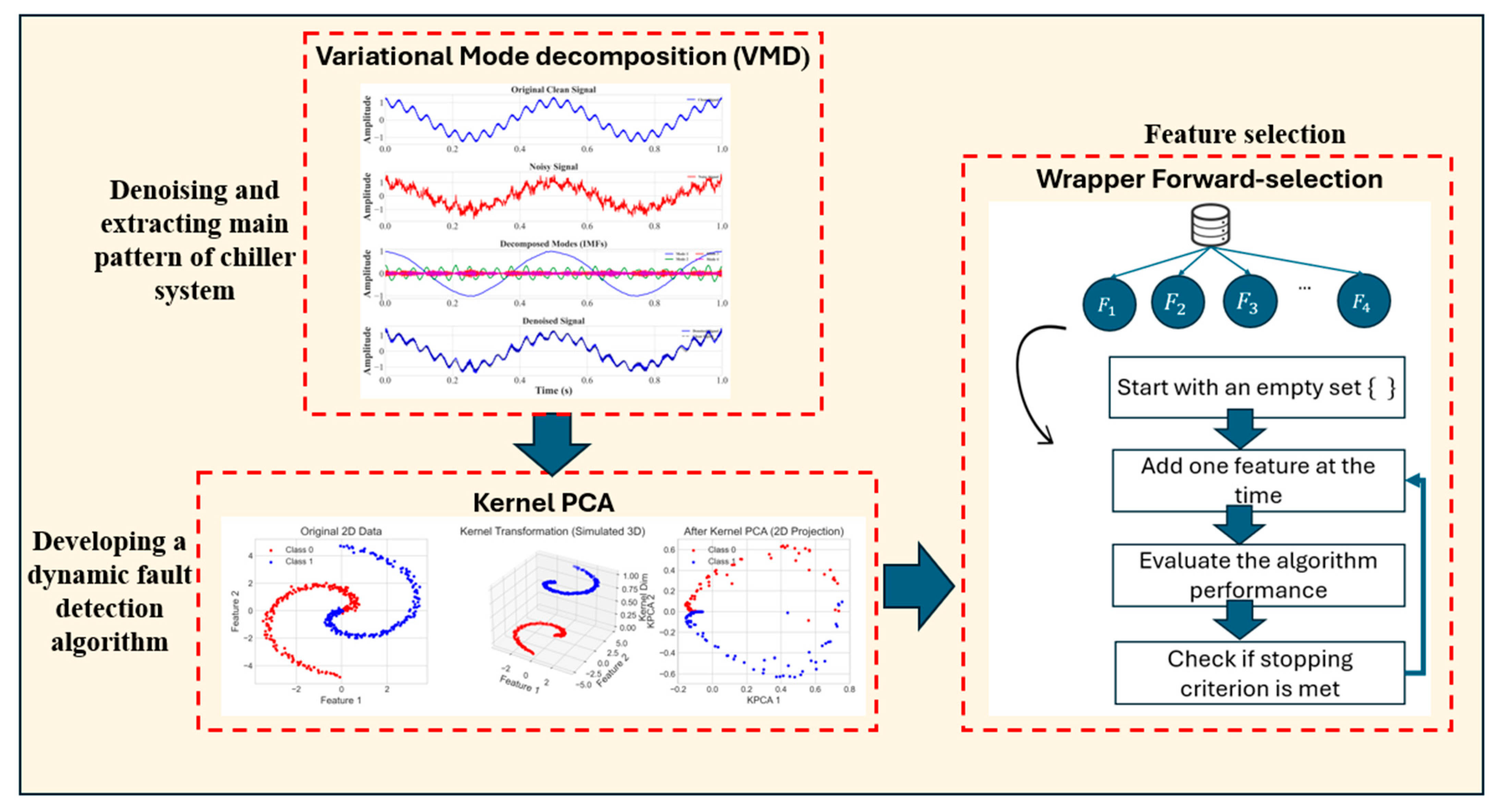

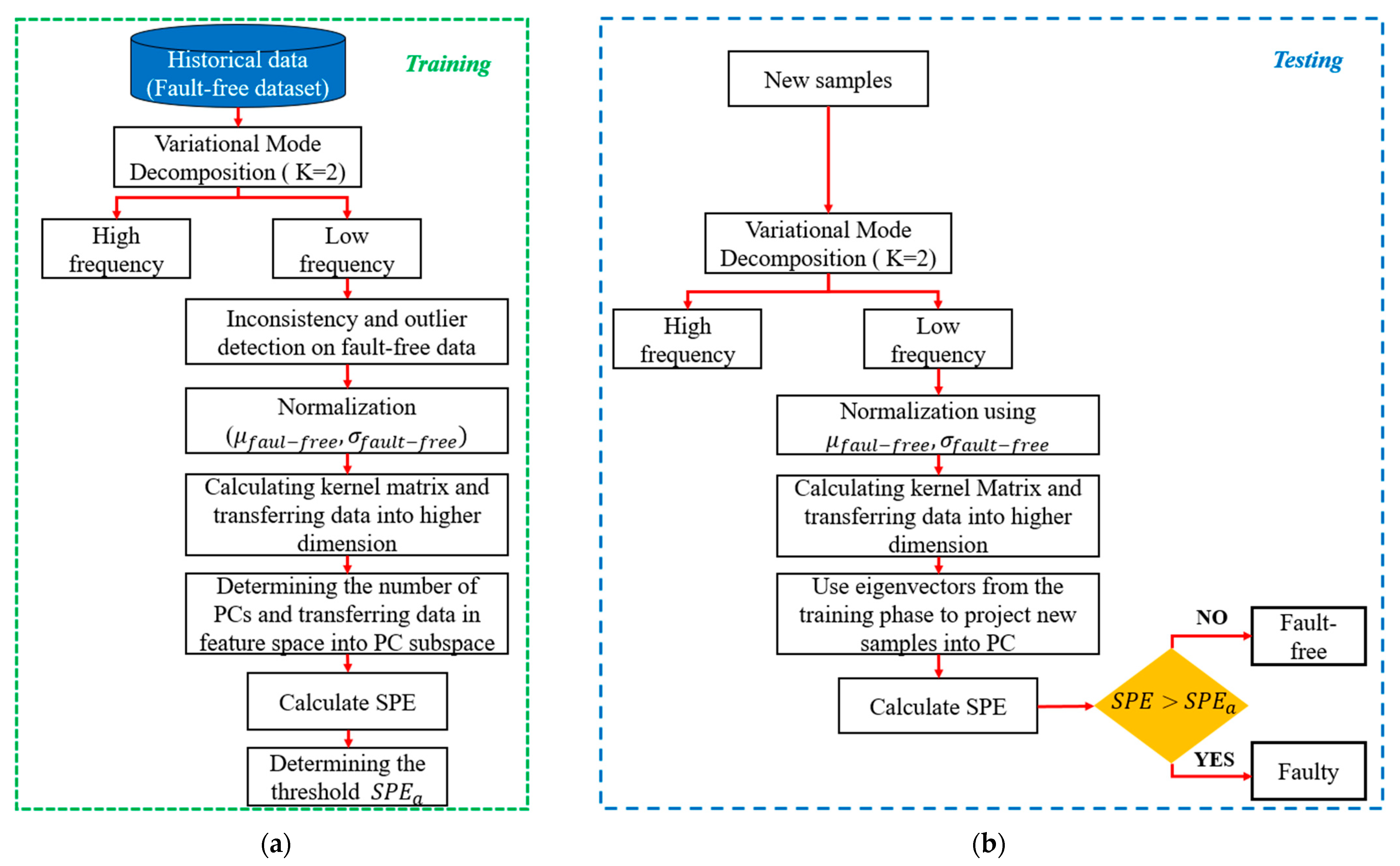

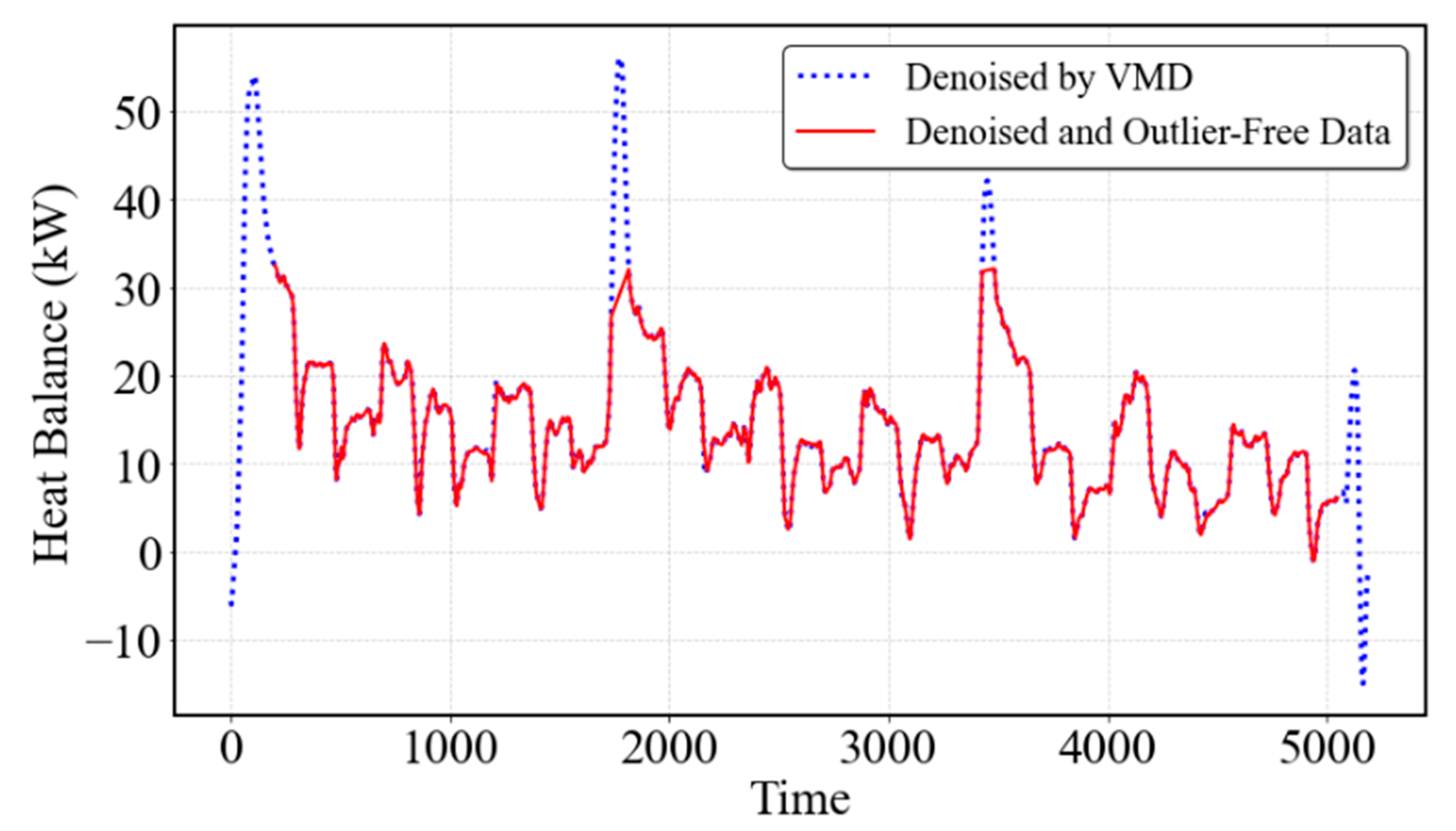

- An unsupervised fault detection algorithm is developed for chiller systems operating under dynamic conditions. The approach consists of two main components: (i) a denoising stage using Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD) to isolate dominant signal modes and (ii) a detection stage using Kernel Principal Component Analysis (KPCA) to capture nonlinear system behavior and identify deviations indicative of faults under both steady-state and transient operating conditions.

- (2)

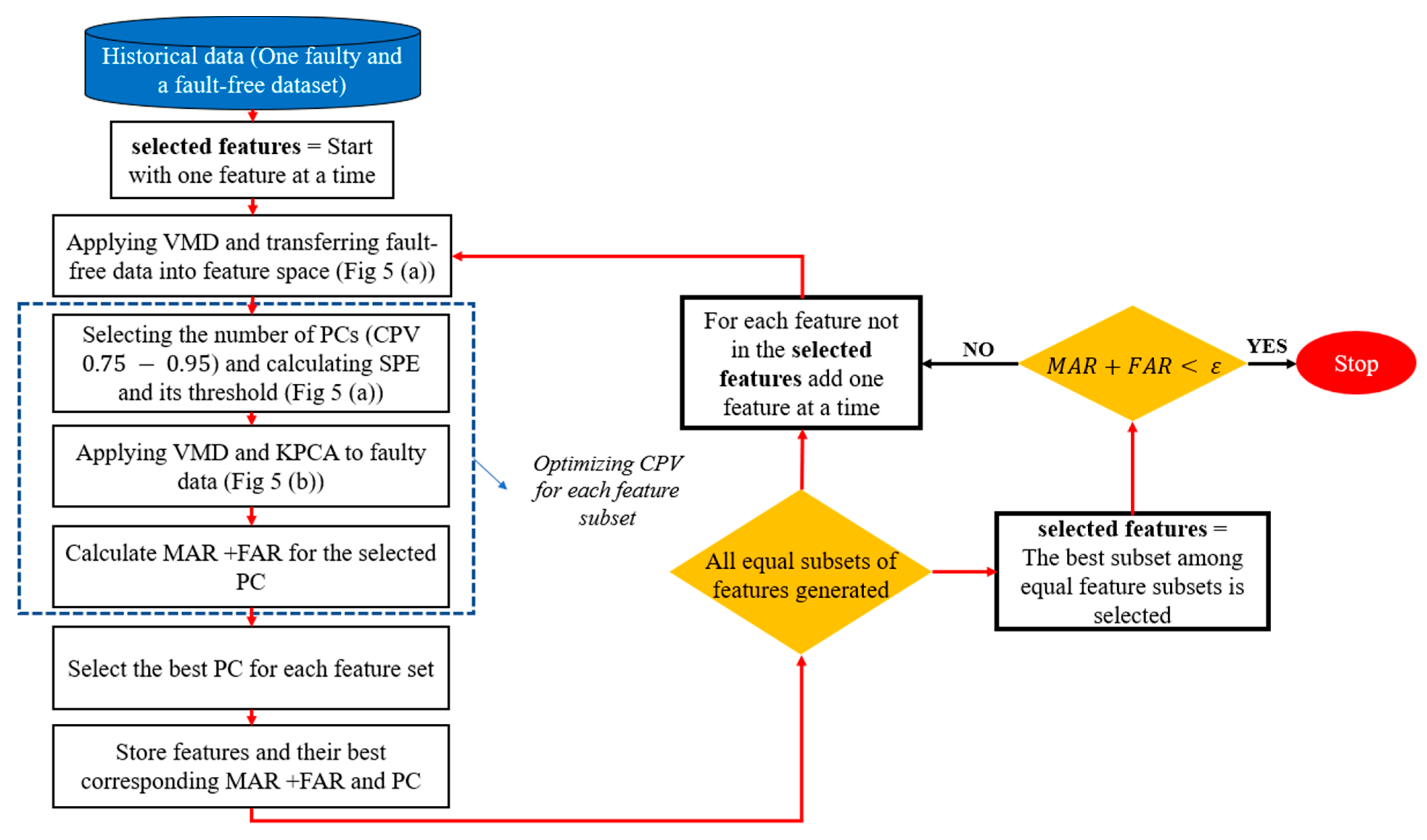

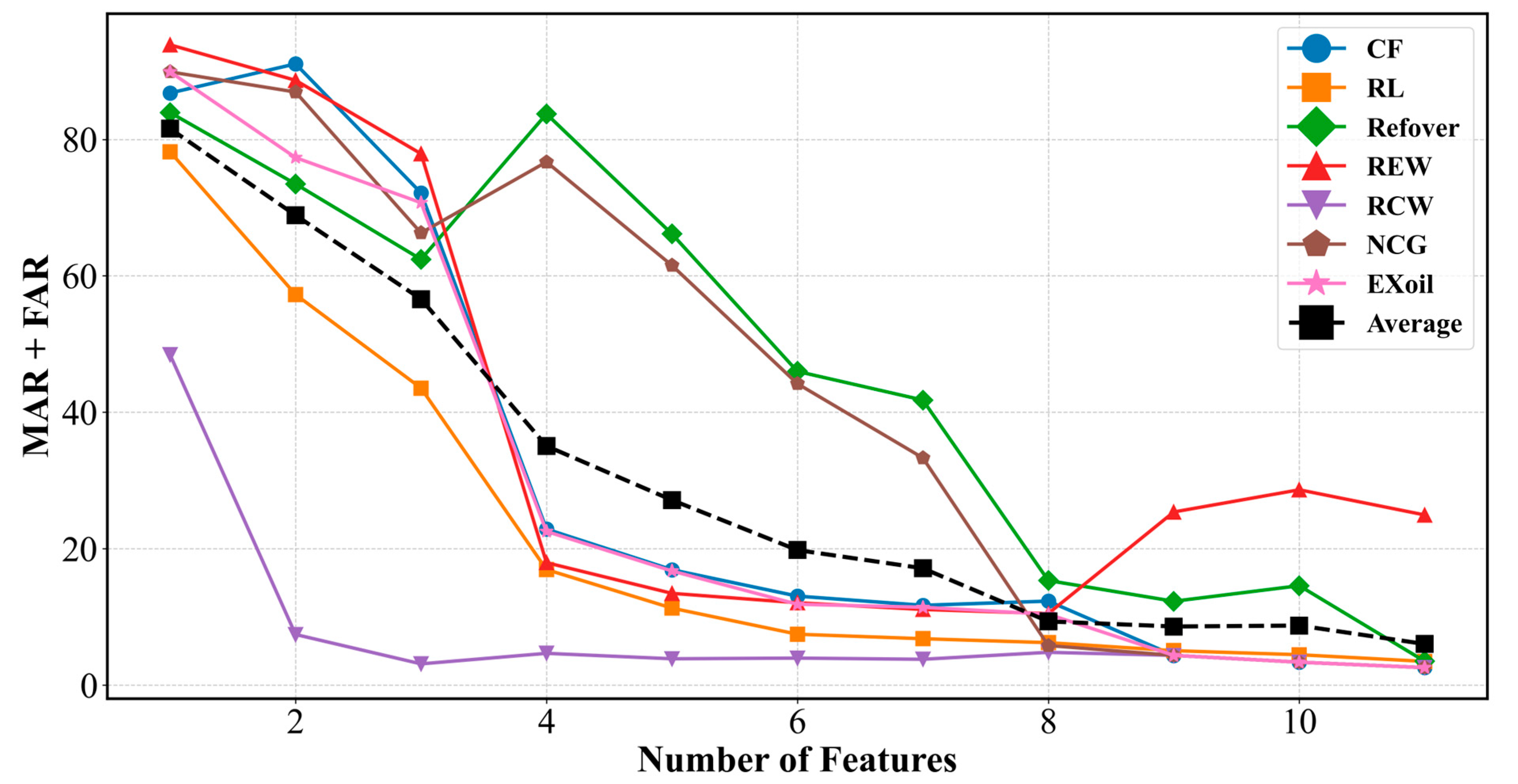

- A wrapper-based forward selection (FS) method is employed to identify the key variables that remain sensitive to faults under dynamic operating conditions for the unsupervised VMD-KPCA framework, improving detection accuracy and reducing false alarm rates while enabling the use of a reduced sensor subset when certain measurements are missing or unavailable in the chiller systems.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Denoising Data Through Signal Decomposition Methods for FDD Using PCA

2.2. PCA and Hybrid of PCA Methods for Steady-State FDD

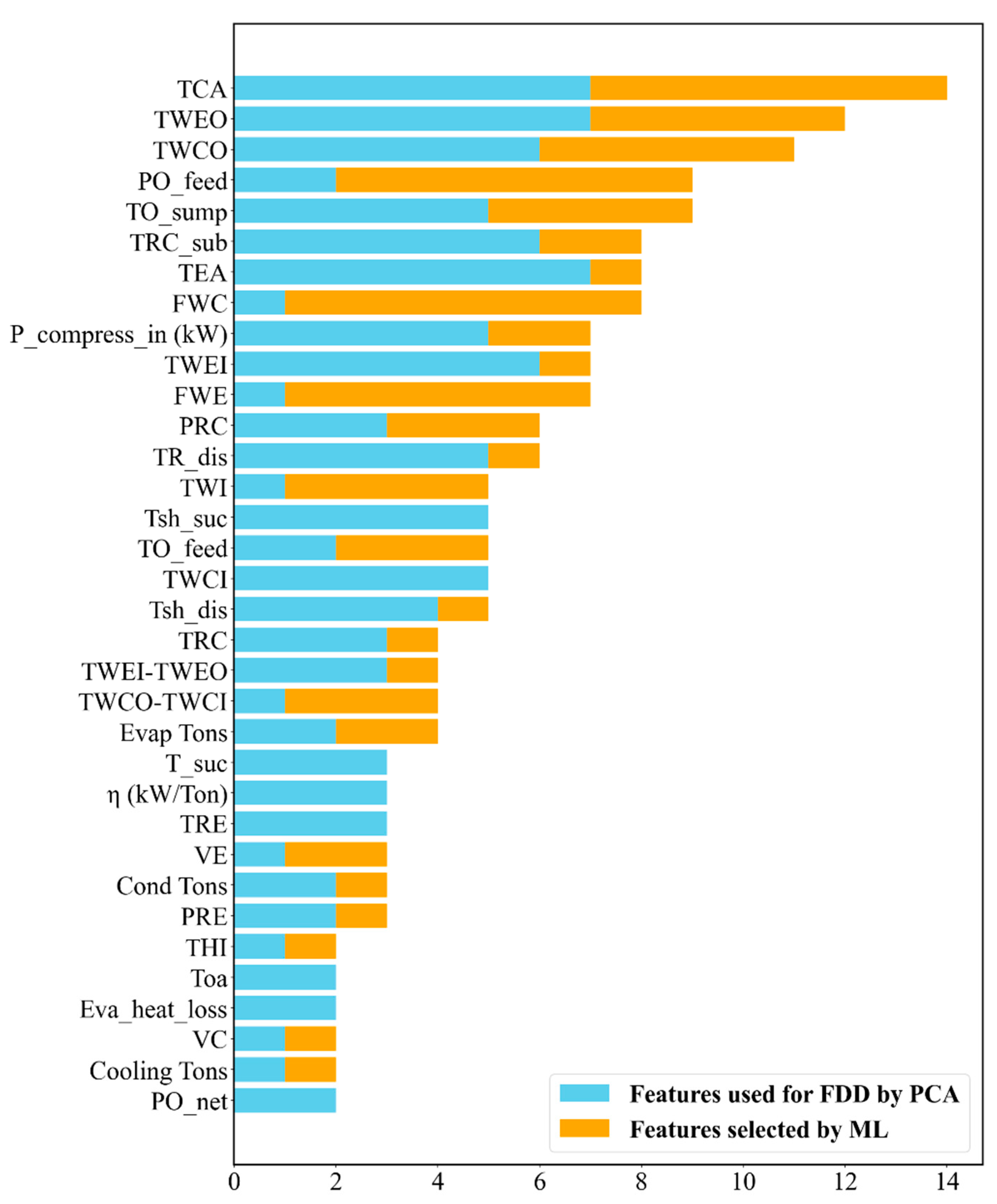

2.3. Feature Selection Using Machine Learning Models for Chiller FDD

- Most existing filtering methods have focused on sensor fault detection and air handling units (AHUs), while the applicability of denoising techniques for detecting component-level faults in chillers has been far less explored.

- While some studies have acknowledged the nonlinear behavior of chillers, the emphasis has primarily been on steady-state operation. The transient behavior, which introduces stronger nonlinearities, has largely been overlooked.

- Although unsupervised techniques such as PCA have been widely used, the selection of sensitive and relevant variables to enhance their fault detection performance has received less attention. Most prior work has instead focused on identifying key variables for supervised fault detection and diagnosis.

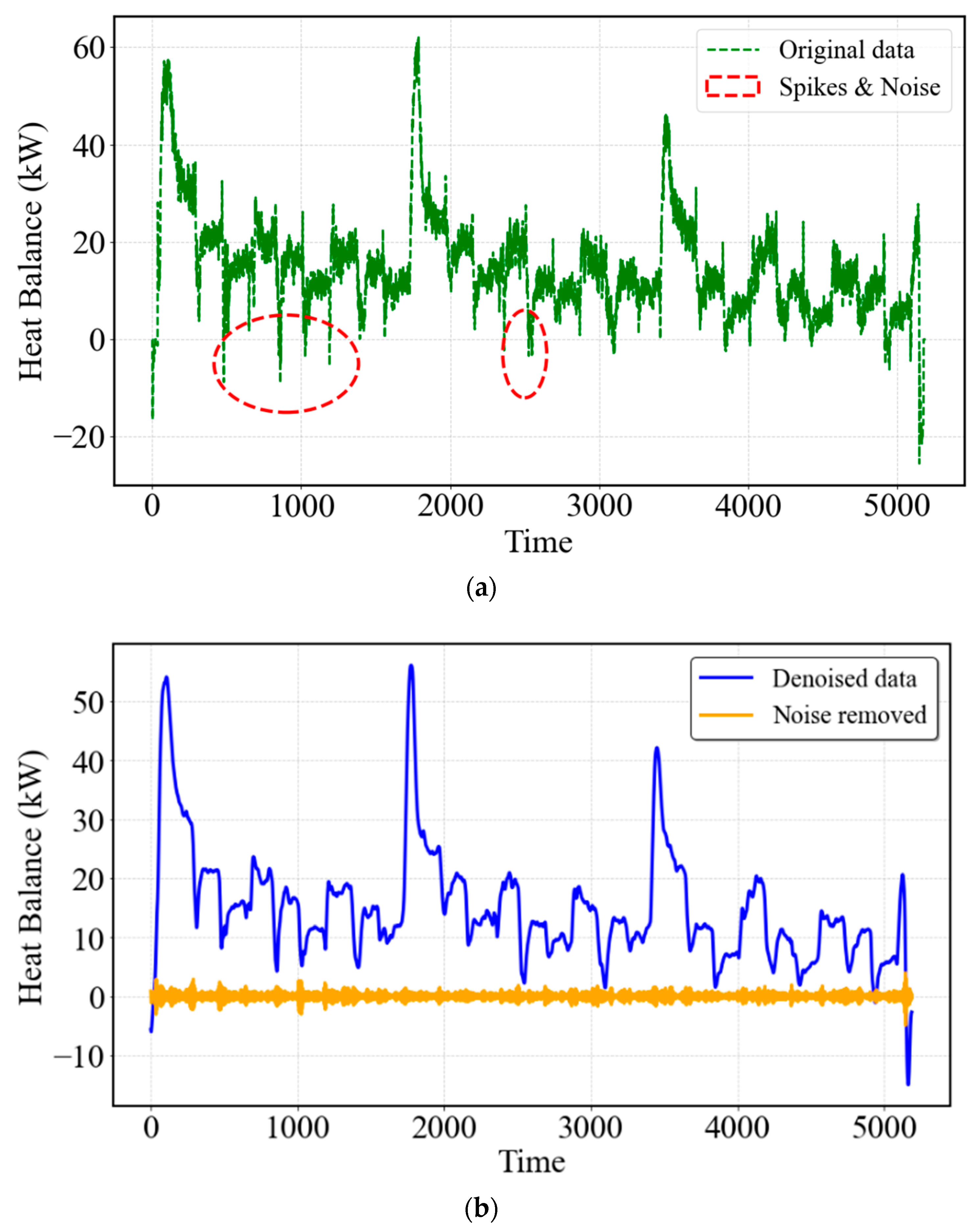

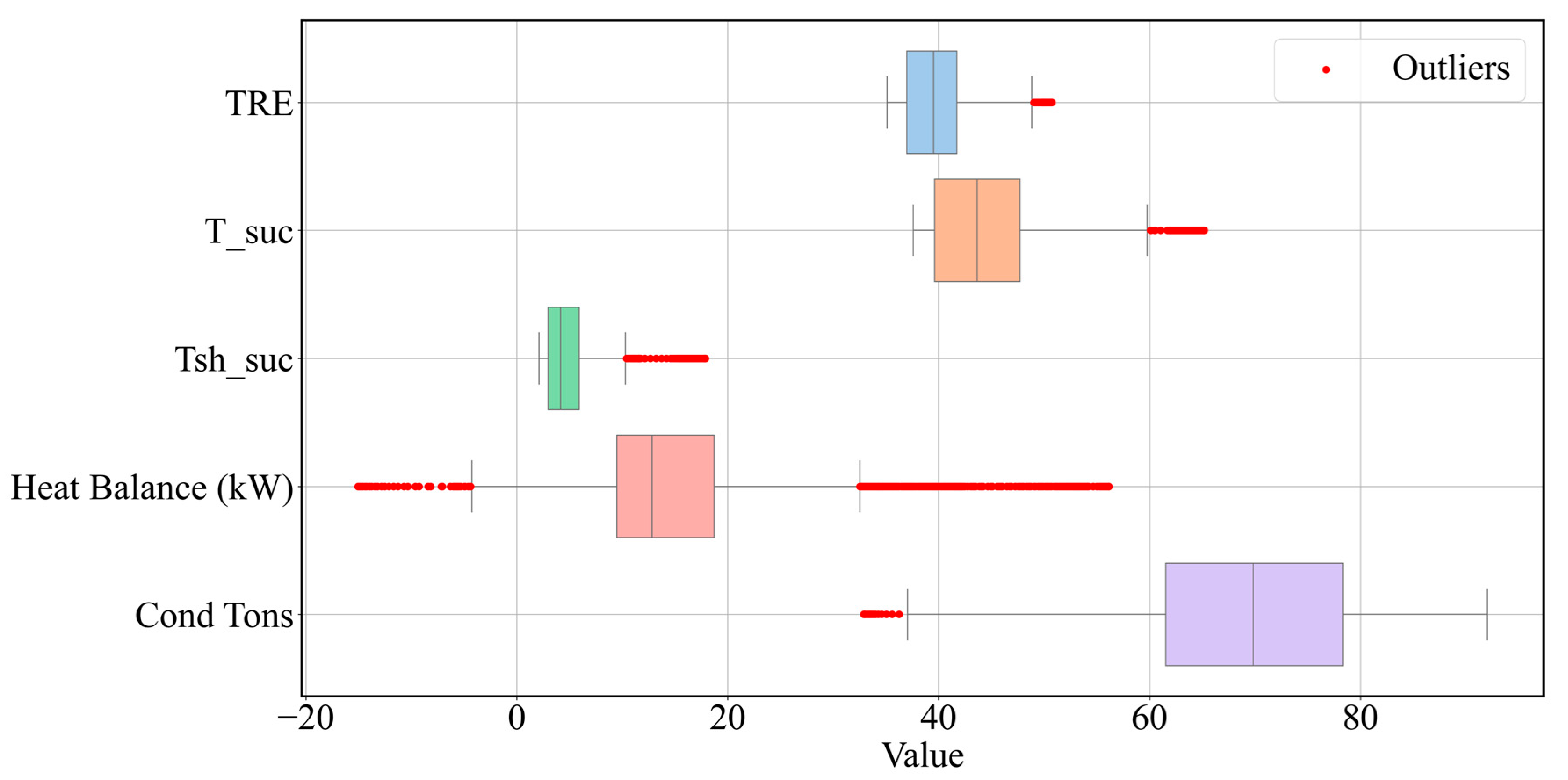

3. Methodology

3.1. Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD)

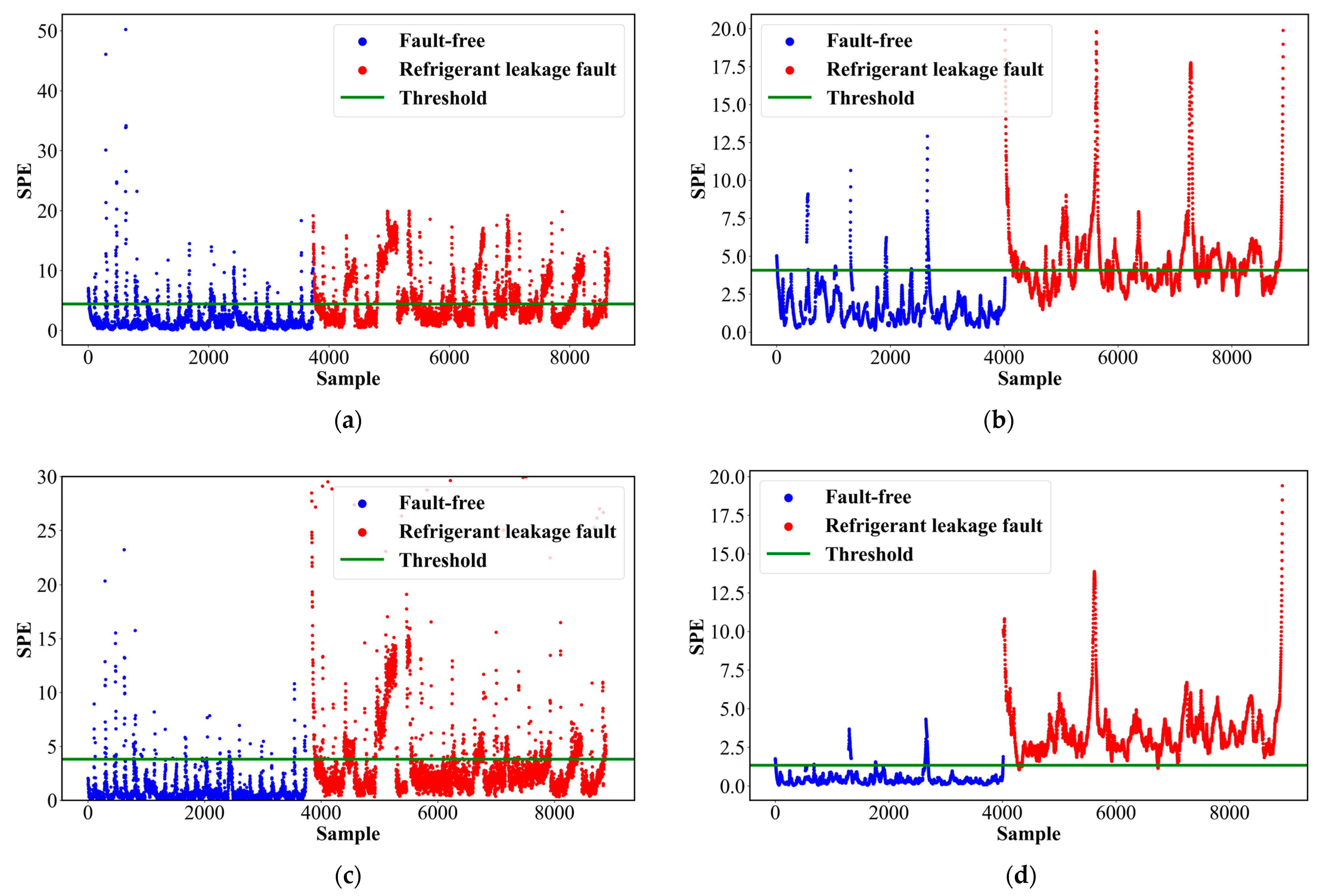

3.2. Kernel PCA

3.3. Fault Detection

3.4. Feature Selection

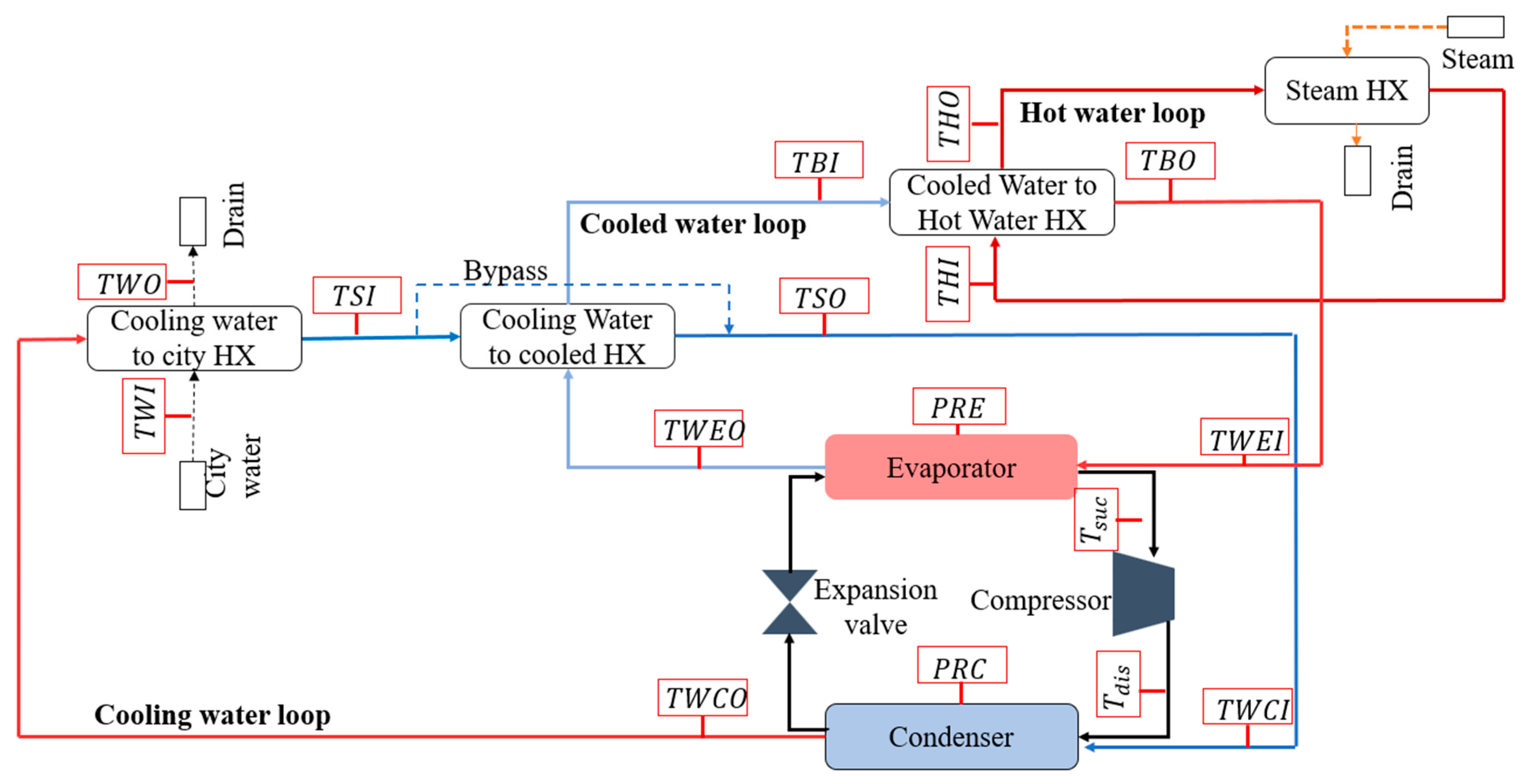

4. Case Study

5. Model Implementation

6. Results and Discussion

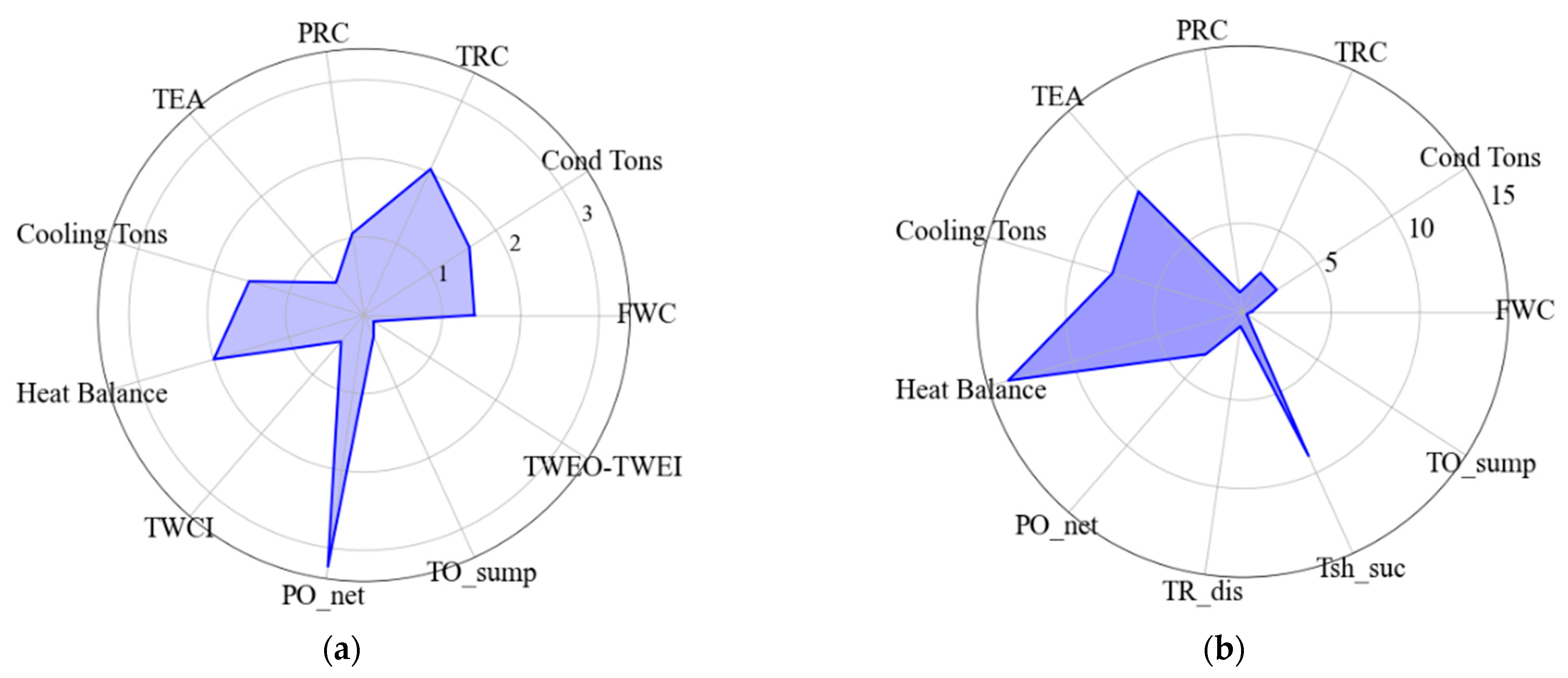

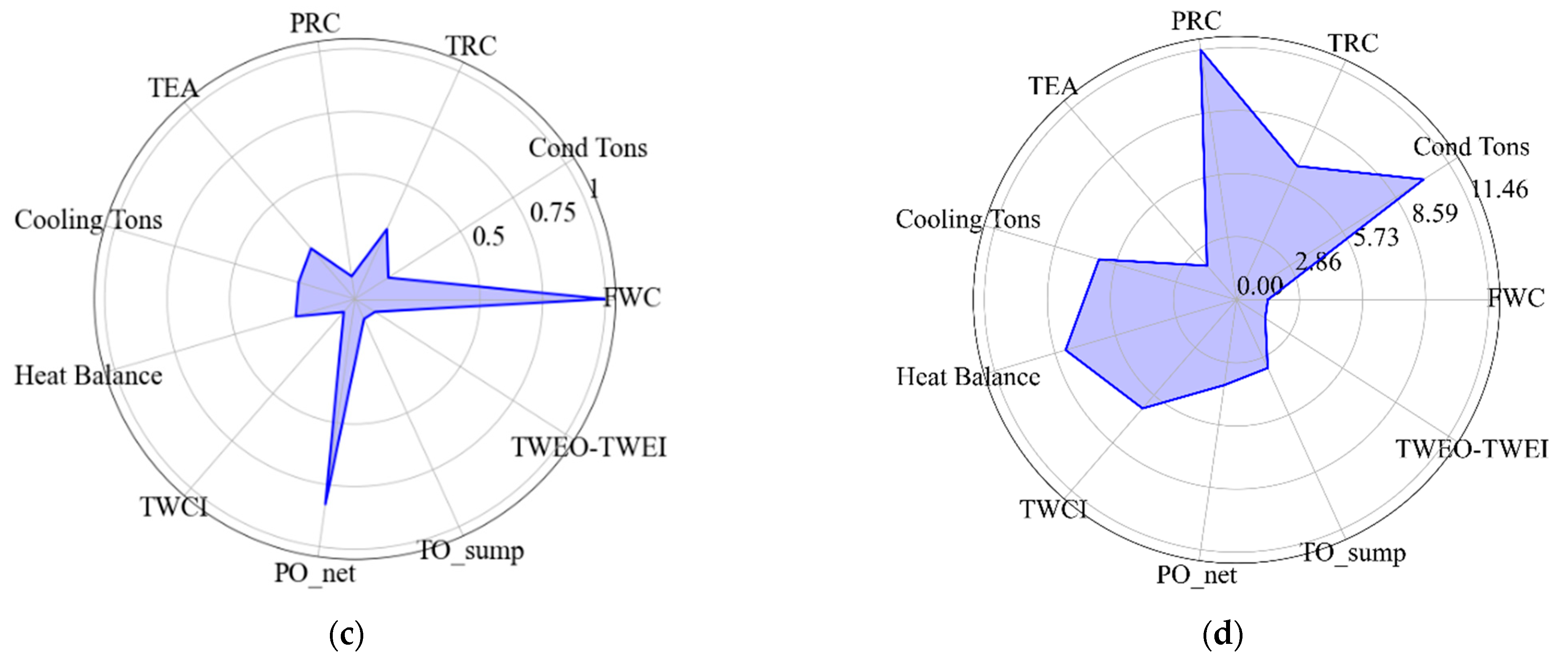

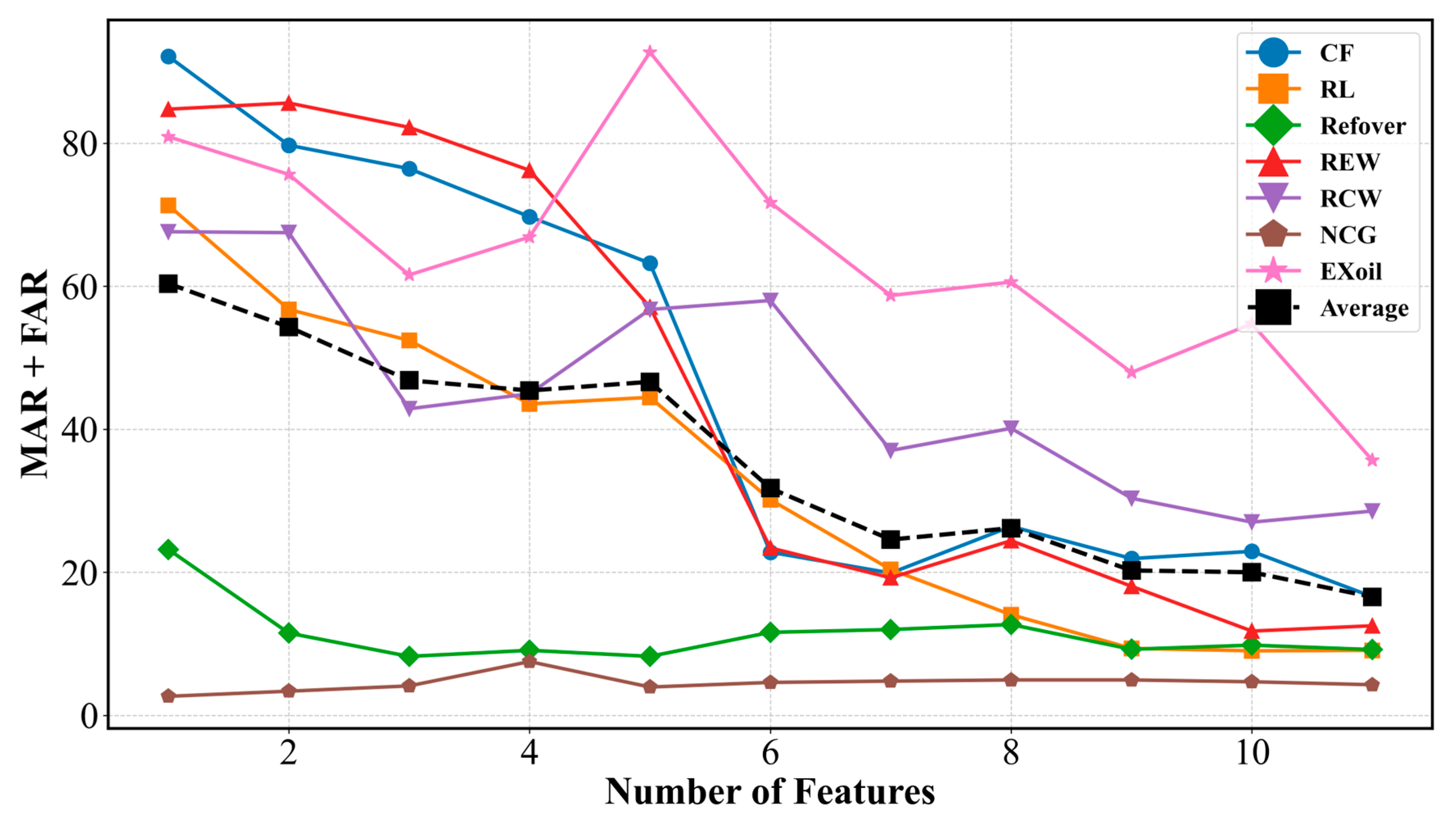

6.1. Case 1—Variables Used and Selected in the Literature

6.2. Case 2—Field-Installed Sensors and Thermodynamic Variables

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Abbreviations | Description |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| CF | Condenser fouling |

| Exoil | Excess oil |

| DNN | Deep Neural Network |

| FDD | Fault Detection and Diagnosis |

| HVAC | Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning |

| KPCA | Kernel PCA |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| RCW | Reduced condenser water flow rate |

| REW | Reduced evaporator water flow rate |

| RL | Refrigerant leakage |

| Refover | Refrigerant overcharge |

| SEER | Seasonal Energy Efficiency Ratio |

| VCS | Vapor Compression System |

| VMD | Variational Mode Decomposition |

| Variables | |

| a | Penalty term coefficient |

| Covariance matrix in the feature space | |

| Expansion valve blockage coefficient | |

| Cond Tons | Calculated Condenser Heat Rejection Rate |

| Cooling Tons | Calculated City Water Cooling Rate |

| Cooling tower fan VFD signal | |

| EEV | Expansion valve opening degree |

| Energy Balance | Calculated 1st Law Energy Balance for Evaporator Water Loop |

| Evap Tons | Calculated Evaporator Cooling Rate |

| Original input signal | |

| Fourier transform of the input signal | |

| FWC | Flow Rate of Condenser Water |

| FWE | Flow Rate of Evaporator Water |

| K | Kernel matrix |

| Number of principal components | |

| Condenser Log Mean Temperature Difference | |

| Evaporator Log Mean Temperature Difference | |

| (kW) | Instantaneous Compressor Power |

| Principal components in the feature space | |

| Residual loading matrix in the feature space | |

| Pressure of Oil Feed | |

| Oil Feed minus Oil Vent Pressure | |

| PRC | Pressure of Refrigerant in Condenser |

| PRE | Pressure of Refrigerant in Evaporator |

| Score of a new measurement in the feature space | |

| Scores in the residual space | |

| Supply cooling tower water temperature | |

| Outdoor air temperature | |

| TACI | Condenser air inlet temperature |

| TACO | Condenser air outlet temperature |

| TCA | Condenser Approach Temperature (TRC-TWCO) |

| TEA | Evaporator Approach Temperature (TWEO-TRE) |

| THI | Temperature of Hot Water In |

| Temperature of Oil Feed | |

| Temperature of Oil in Sump | |

| Refrigerant Discharge Temperature | |

| TRC | Saturated Refrigerant Temperature in Condenser |

| Liquid-line Refrigerant Subcooling from Condenser | |

| TRE | Saturated Refrigerant Temperature in Evaporator |

| TREI | Evaporator refrigerant inlet temperature |

| TREO | Evaporator refrigerant outlet temperature |

| Refrigerant Discharge Superheat Temperature | |

| Refrigerant Suction Superheat Temperature | |

| TWCI | Temperature of Condenser Water In |

| TWCO | Temperature of Condenser Water Out |

| TWEI | Temperature of Evaporator Water In |

| TWEO | Temperature of Evaporator Water Out |

| TWI | Temperature of City Water In |

| Fourier transform of | |

| The k-th intrinsic mode function (IMF) | |

| Eigenvector of the covariance matrix | |

| V | Variance of SPE values |

| VC | Condenser Valve Position |

| VE | Evaporator Valve Position |

| VL | Ventilation Level |

| Data matrix | |

| Dirac delta function | |

| Pressure loss of the cooling water in condenser | |

| Condenser water temperature difference (TWCO-TWCI) | |

| Evaporator water temperature difference (TWEI-TWEO) | |

| Heat transfer efficiency in saturation section of condenser | |

| Heat transfer efficiency in saturation section of evaporator | |

| Heat transfer efficiency in superheat section of condenser | |

| Heat transfer efficiency in superheat section of evaporator | |

| Heat transfer efficiency in subcooling section of condenser | |

| Calculated compressor efficiency | |

| Isentropic efficiency of the compressor | |

| Polytropic efficiency of the compressor | |

| Lagrange multiplier | |

| Diagonal matrix of eigenvalues | |

| μ | Mean of SPE values |

| Matrix of mapped data points in the feature space | |

| i-th mapped data point in the feature space | |

| Chi-squared statistic | |

| The central frequency of the k-th mode | |

| ℷ | Eigenvalue of the covariance matrix or kernel matrix |

References

- Ssembatya, M.; Claridge, D.E. Quantitative Fault Detection and Diagnosis Methods for Vapour Compression Chillers: Exploring the Potential for Field-Implementation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 197, 114418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Wang, Z.; Gu, X.; Wang, Z. Multicondition Operation Fault Detection for Chillers Based on Global Density-Weighted Support Vector Data Description. Appl. Soft Comput. 2021, 112, 107795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dincer, I. Refrigeration Systems and Applications; Third Edition; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; ISBN 9781119230755. [Google Scholar]

- ASHRAE. ASHRAE Handbook—HVAC Systems and Equipment; ASHRAE: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen, B.P. Dynamic Modeling for Vapor Compression Systems-Part I: Literature Review. HVAC R Res. 2012, 18, 934–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Reddy, T.A. Characteristic Physical Parameter Approach to Modeling Chillers Suitable for Fault Detection, Diagnosis, and Evaluation. J. Sol. Energy Eng. Trans. ASME 2003, 125, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Q.; Guo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Du, C.; Liu, X. Optimization Study of Energy Saving Control Strategy of Carbon Dioxide Heat Pump Water Heater System under the Perspective of Energy Storage. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2026, 283, 129030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, T.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, C. Artificial Intelligence-Based Fault Detection and Diagnosis Methods for Building Energy Systems: Advantages, Challenges and the Future. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 109, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagpal, R. Computer-Aided Evaluation of HVAC System Performance, Technical Report; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2002; p. 60. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, W.; Katipamula, S. A Review of Fault Detection and Diagnostics Methods for Building Systems. Sci. Technol. Built Environ. 2018, 24, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afroz, Z.; Shafiullah, G.M.; Urmee, T.; Higgins, G. Modeling Techniques Used in Building HVAC Control Systems: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 83, 64–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; O’Brien, W. Development and Implementation of Automated Fault Detection and Diagnostics for Building Systems: A Review. Autom. Constr. 2019, 104, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezyan, B.; Zmeureanu, R. Detection and Diagnosis of Dependent Faults That Trigger False Symptoms of Heating and Mechanical Ventilation Systems Using Combined Machine Learning and Rule-Based Techniques. Energies 2022, 15, 1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Xiao, F.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, J. Analytical Investigation of Autoencoder-Based Methods for Unsupervised Anomaly Detection in Building Energy Data. Appl. Energy 2018, 211, 1123–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babadi Soultanzadeh, M.; Nik-Bakht, M.; Ouf, M.M.; Paquette, P.; Lupien, S. Unsupervised Automated Fault Detection and Diagnosis for Light Commercial Buildings’ HVAC Systems. Build Environ 2025, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, K.; Huang, J.; Shen, W.; Ji, Z. Unsupervised Learning for Fault Detection and Diagnosis of Air Handling Units. Energy Build. 2020, 210, 109689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Tian, Z.; Ye, C.; Wang, M.; Cao, Y. A Study on Source Domain Selection for Cross-Domain Fault Diagnosis in HVAC Systems. Build Environ 2025, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tra, V.; Amayri, M.; Bouguila, N. Unsupervised Fault Detection for Building Air Handling Unit Systems Using Deep Variational Mixture of Principal Component Analyzers. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2023, 21, 6787–6803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; O’Neill, Z.; Wen, J.; Pradhan, O.; Yang, T.; Lu, X.; Lin, G.; Miyata, S.; Lee, S.; Shen, C.; et al. A Review of Data-Driven Fault Detection and Diagnostics for Building HVAC Systems. Appl Energy 2023, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Li, D.; Liang, N. Genetic Algorithm-Aided Ensemble Model for Sensor Fault Detection and Diagnosis of Air-Cooled Chiller System. Build. Environ. 2023, 233, 110089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lan, L. A Fault Detection Technique for Air-Source Heat Pump Water Chiller/Heaters. Energy Build. 2009, 41, 881–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beghi, A.; Brignoli, R.; Cecchinato, L.; Menegazzo, G.; Rampazzo, M.; Simmini, F. Data-Driven Fault Detection and Diagnosis for HVAC Water Chillers. Control Eng. Pract. 2016, 53, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Ding, Q.; Li, Z.; Jiang, A. Fault Detection for Centrifugal Chillers Using a Kernel Entropy Component Analysis (KECA) Method. Build. Simul. 2021, 14, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Esbrí, J.; Torrella, E.; Cabello, R. A Vapour Compression Chiller Fault Detection Technique Based on Adaptative Algorithms. Application to on-Line Refrigerant Leakage Detection. Int. J. Refrig. 2006, 29, 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keir, M.C. Dynamic Modeling, Control, and Fault Detection in Vapor Compression Systems. Master Thesis, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Champaign, IL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Braun, J.E. Decoupling Features for Diagnosis of Reversing and Check Valve Faults in Heat Pumps. Int. J. Refrig. 2009, 32, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuwono, M.; Guo, Y.; Wall, J.; Li, J.; West, S.; Platt, G.; Su, S.W. Unsupervised Feature Selection Using Swarm Intelligence and Consensus Clustering for Automatic Fault Detection and Diagnosis in Heating Ventilation and Air Conditioning Systems. Appl. Soft Comput. J. 2015, 34, 402–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, K.; Ma, L.; Dai, Y.; Shen, W.; Ji, Z.; Xie, D. Cost-Sensitive and Sequential Feature Selection for Chiller Fault Detection and Diagnosis. Int. J. Refrig. 2018, 86, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezyan, Y.; Nik-Bakht, M.; Nasiri, F. Fault Detection and Diagnosis of Chillers under Transient Conditions. In Proceedings of the Canadian Society for Civil Engineering Annual Conference, Moncton, NB, Canada, 24–27 May 2023; pp. 369–381. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Xiao, F.; Wang, S. Enhanced Chiller Sensor Fault Detection, Diagnosis and Estimation Using Wavelet Analysis and Principal Component Analysis Methods. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2008, 28, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wen, J. A Model-Based Fault Detection and Diagnostic Methodology Based on PCA Method and Wavelet Transform. Energy Build. 2014, 68, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Q.; Fang, X.; Hu, Y.; Li, G. Chiller Sensor Fault Detection Based on Empirical Mode Decomposition Threshold Denoising and Principal Component Analysis. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2018, 144, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Hu, Y. An Enhanced PCA-Based Chiller Sensor Fault Detection Method Using Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition Based Denoising. Energy Build. 2019, 183, 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komaty, A.; Boudraa, A.O.; Augier, B.; Dare-Emzivat, D. EMD-Based Filtering Using Similarity Measure between Probability Density Functions of IMFs. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2014, 63, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Chen, J.; Lang, X.; Xie, L.; Rehman, N.; Su, H. Self-Tuning Variational Mode Decomposition. J. Franklin Inst. 2021, 358, 7825–7862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotrufo, N.; Zmeureanu, R. PCA-Based Method of Soft Fault Detection and Identification for the Ongoing Commissioning of Chillers. Energy Build. 2016, 130, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmini, F.; Rampazzo, M.; Beghi, A.; Peterle, F. Local Principal Component Analysis for Fault Detection in Air-Condensed Water Chillers. In Proceedings of the IEEE 23rd International Conference on Emerging Technologies and Factory Automation (ETFA), Turin, Italy, 4–7 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Y.; Ding, Q.; Jing, N.; Tang, Y.; Jiang, A.; Jiangzhou, S. An Enhanced Fault Detection Method for Centrifugal Chillers Using Kernel Density Estimation Based Kernel Entropy Component Analysis. Int. J. Refrig. 2021, 129, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmini, F.; Rampazzo, M.; Peterle, F.; Susto, G.A.; Beghi, A. A Self-Tuning KPCA-Based Approach to Fault Detection in Chiller Systems. IEEE Trans. Control. Syst. Technol. 2022, 30, 1359–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Shang, L.; Yan, H.; Chen, W.; Zhu, J.; Zhao, F. Multi-Condition Incipient Fault Detection for Chillers Based on Local Anomaly Kernel Entropy Component Analysis. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Hu, Y.; Chen, H.; Shen, L.; Li, H.; Hu, M.; Liu, J.; Sun, K. An Improved Fault Detection Method for Incipient Centrifugal Chiller Faults Using the PCA-R-SVDD Algorithm. Energy Build. 2016, 116, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, L.; Liang, K.; Tan, Y. Enhanced Chiller Fault Detection Using Bayesian Network and Principal Component Analysis. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2018, 141, 898–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Li, D.; Liu, X.; Liu, G. Enhanced Chiller Faults Detection and Isolation Method Based on Independent Component Analysis and K-Nearest Neighbors Classifier. Build Environ 2022, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Hu, Y.; Liu, J.; Fang, X.; Kang, J. Review on Fault Detection and Diagnosis Feature Engineering in Building Heating, Ventilation, Air Conditioning and Refrigeration Systems. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 2153–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, M.; Johnson, K. Feature Engineering and Selection; A Practical Approach for Predictive Models, 1st ed.; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H.; Gu, B.; Wang, T.; Li, Z.R. Important Sensors for Chiller Fault Detection and Diagnosis (FDD) from the Perspective of Feature Selection and Machine Learning. Int. J. Refrig. 2011, 34, 586–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Han, H.; Ren, Z.X.; Gao, J.Q.; Jiang, S.X.; Yang, Y.T. Comprehensive Study on Sensitive Parameters for Chiller Fault Diagnosis. Energy Build. 2021, 251, 111318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Guo, J.; Xia, P.; Wang, L.; Zhang, C.; Leng, Q.; Zheng, K. Feature Selection for Chillers Fault Diagnosis from the Perspectives of Machine Learning and Field Application. Energy Build. 2024, 307, 113937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, J.; Wang, H.; Hua, M.; Yan, K. An Interpretable Feature Selection Method Integrating Ensemble Models for Chiller Fault Diagnosis. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 87, 109029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezyan, Y.; Nasiri, F.; Nik-Bakht, M. A Feature Selection Approach for Unsupervised Steady-State Chiller Fault Detection. In International Association of Building Physics, Proceedings of the Multiphysics and Multiscale Building Physics, Toronto, ON, Canada, 25–27 July 2024; Berardi, U., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2024; Volume 3, pp. 148–153. [Google Scholar]

- Dragomiretskiy, K.; Zosso, D. Variational Mode Decomposition. IEEE Trans. Signal Process 2013, 62, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazzini, P.; La Tona, G.; Diez, M.; Di Piazza, M.C. Enhanced Forecasting of Shipboard Electrical Power Demand Using Multivariate Input and Variational Mode Decomposition with Mode Selection. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebreton, C.; Kbidi, F.; Graillet, A.; Jegado, T.; Alicalapa, F.; Benne, M.; Damour, C. PV System Failures Diagnosis Based on Multiscale Dispersion Entropy. Entropy 2022, 24, 1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schölkopf, B.; Smola, A.; Müller, K.-R. Nonlinear Component Analysis as a Kernel Eigenvalue Problem. Neural Comput. 1998, 10, 1299–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.M.; Yoo, C.K.; Lee, I.B. Fault Detection of Batch Processes Using Multiway Kernel Principal Component Analysis. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2004, 28, 1837–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comstock, M.C.; Braun, J.E. Development of Analysis Tools for the Evaluation of Fault Detection and Diagnostics for Chillers, ASHRAE Research Project 1043; American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers, Inc.: Peachtree Corners, GA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

| FDD Method | Reference | PCA Type/Detection/Diagnosis Method | Variables |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional PCA | Chen and Lan [21] | PCA/SPE/- | TWEO, TWEI, TREO, TREI, TRCI, TRCO, TACI, TACO |

| Beghi et al. (2016) [22] | PCA/SPE, /Reconstruction based contribution | TWEO-TWEI, , TCA, TEA, Overall evaporator heat loss coefficients,, , , | |

| Cotrufo and Zmeureanu [36] | PCA/score values out of ellipsoid threshold on normal data/- | , (kW), TWEO, TWEI, TWCO, , | |

| PCA variants | Simmini et al. [37] | Local PCA/(combined of SPE and )/- | TWEO-TWEI, , VL, PRC, EEV, , |

| Xia et al. [38] | KECA/Cauchy–Schwarz (CS) divergence/- | All 64 variables reported in ASHARE RP-1043 | |

| Simmini et al. [39] | KPCA/SPE/- | Cond Tons, Evap Tons, (kW), (kW/ton), TEA, TCA, PRE, PRC, , , , , , TWCO-TWCI, TWEO-TWEI, Overall condenser heat loss coefficients, Overall evaporator heat loss coefficients | |

| Lu et al. (2024) [40] | KECA/LOF/- | TWEI, TWEO, TWCI, TWCO, (kW), TEA, TCA, TRE, TRC, , , , , , , | |

| Hybrid of PCA and other techniques | Li et al. (2016) [41] | PCA and SVDD/Distance based statistics | TWEO, TWCI, TWCO, TEA, TCA, , , |

| Wang et al. [42] | PCA-BNN/Posterior probabilities | TWEI, TWEO, TWCI, TWCO, TEA, TCA, , , | |

| Gao et al. [43] | ICA/ and dynamic thresholding using EWMA/KNN on residual vectors | TWEO, TWCI, TWCO, TEA, TCA, , , , TWEI, (kW), TRE, TRC, , , , |

| Ref | Machine Learning Models | Features |

|---|---|---|

| Han et al. [46] | GA-SVM | TWEO, TWCO, TRC, , TWI, FWC, VE |

| Yan et al. [28] | SVM | , TWCO, Evap Tons, TWEI, TCA,, PRE, THI, TWEO, FWC, PRC, FWE, |

| Gao et al. [47] | RF, KNN, SVM | , TWI, TWEO, TCA, (kW), PRC, , FWC, FWE, (Cond Tons, Evap Tons, Energy Balance, Heat Balance, Cooling Tons) |

| Wang et al. [48] | GA-BN, BPNN, RF, CNN, SVM, RNN, AE | (kW), TWCO, TEA, TCA, , TCA, Tsh_dis, , , , FWC, FWE, TWCO, TCA, ,, , FWC, FWE, , , |

| Bi et al. [49] | SVM, DT, KNN, RF, XGBoost, CatBoost, LightGBM, DNN, CNN, DBN | TWI, , VE, VC, TCA, FWC, , , FWE, TWEO |

| Variables | Case 1 (Features Used and Selected in the Literature) | Case 2 (Variables and Sensors Commonly Installed in the Field) |

|---|---|---|

| TCA | ✓ | ✓ |

| TWEO | ✓ | ✓ |

| TWCO | ✓ | ✓ |

| ✓ | ||

| ✓ | ||

| FWC | ✓ | |

| TEA | ✓ | ✓ |

| FWE | ✓ | |

| (kW) | ✓ | ✓ |

| TWEI | ✓ | ✓ |

| ✓ | ✓ | |

| ✓ | ✓ | |

| PRC | ✓ | ✓ |

| ✓ | ✓ | |

| ✓ | ✓ | |

| TWCI | ✓ | ✓ |

| ✓ | ||

| TRC | ✓ | ✓ |

| TWCO-TWCI | ✓ | ✓ |

| Evap Tons | ✓ | |

| TWEO-TWEI | ✓ | ✓ |

| PRE | ✓ | ✓ |

| Cond Tons | ✓ | |

| TRE | ✓ | ✓ |

| (kW/Ton) | ✓ | ✓ |

| ✓ | ✓ | |

| VE | ✓ | |

| Cooling Tons | ✓ | |

| ✓ | ||

| VC | ✓ | |

| COP | ✓ | ✓ |

| ✓ | ✓ | |

| Heat Balance (kW) | ✓ | |

| ✓ | ||

| ✓ | ||

| ✓ | ||

| ✓ | ||

| ✓ | ||

| ✓ | ||

| ✓ |

| No | Features | Number of PC | FDA of Each Fault | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CF | RL | Refover | REW | RCW | NCG | Exoil | |||

| 1 | FWC | 1 | 61.6 | 70.2 | 64.4 | 54.55 | 100 | 58.52 | 58.52 |

| 2 | FWC, Cond Tons | 2 | 16.3 | 50.1 | 33.9 | 18.76 | 100 | 20.48 | 30.09 |

| 3 | FWC, Cond Tons, TRC | 5 | 30.9 | 59.5 | 40.6 | 25.21 | 100 | 36.83 | 32.4 |

| 4 | FWC, Cond Tons, TRC, PRC | 4 | 81.7 | 87.7 | 20.9 | 86.71 | 100 | 27.96 | 82.13 |

| 5 | FWC, Cond Tons, TRC, PRC, TEA | 5 | 86.9 | 92.5 | 37.7 | 90.41 | 100 | 42.33 | 87.13 |

| 6 | FWC, Cond Tons, TRC, PRC, TEA, Cooling Tons | 8 | 90.9 | 96.5 | 57.9 | 91.89 | 100 | 59.77 | 92.11 |

| 7 | FWC, Cond Tons, TRC, PRC, TEA, Cooling Tons, Heat Balance | 9 | 92 | 96.9 | 62 | 92.7 | 100 | 70.48 | 92.37 |

| 8 | FWC, Cond Tons, TRC, PRC, TEA, Cooling Tons, Heat Balance, TWCI | 9 | 92.4 | 97.05 | 89 | 94.31 | 100 | 99.01 | 94.42 |

| 9 | FWC, Cond Tons, TRC, PRC, TEA, Cooling Tons, Heat Balance, TWCI, | 9 | 100 | 97.8 | 92 | 78.98 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 10 | FWC, Cond Tons, TRC, PRC, TEA, Cooling Tons, Heat Balance, TWCI, , | 10 | 100 | 96.9 | 88.7 | 74.73 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 11 | FWC, Cond Tons, TRC, PRC, TEA, Cooling Tons, Heat Balance, TWCI, , , TWEO-TWEI | 7 | 100 | 97.1 | 98.9 | 77.62 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| No | Features | Number of PC | FDA for Each Fault | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RL | Refover | RCW | REW | CF | NCG | Exoil | |||

| 1 | 1 | 31.35 | 79.47 | 35.04 | 17.9 | 10.53 | 100 | 21.76 | |

| 2 | , TWCO | 3 | 46.62 | 91.88 | 35.89 | 17.76 | 23.66 | 100 | 27.75 |

| 3 | , TWCO, | 5 | 51.7 | 95.88 | 61.25 | 21.9 | 27.68 | 100 | 42.54 |

| 4 | , TWCO, , TEA | 6 | 63.97 | 98.43 | 62.56 | 31.31 | 37.8 | 100 | 40.63 |

| 5 | , TWCO, , TEA, | 7 | 59.49 | 95.71 | 47.2 | 46.89 | 40.74 | 100 | 11.23 |

| 6 | , TWCO, , TEA, , (kW/Ton) | 7 | 74.45 | 93 | 46.6 | 81.19 | 81.79 | 100 | 32.91 |

| 7 | , TWCO, , TEA, , (kW/Ton), | 9 | 84.4 | 92.79 | 67.76 | 85.56 | 84.89 | 100 | 46.08 |

| 8 | , TWCO, , TEA, , (kW/Ton), , | 10 | 90.88 | 92.25 | 64.82 | 80.52 | 78.53 | 100 | 44.36 |

| 9 | , TWCO, , TEA, , (kW/Ton), , , (kW) | 9 | 95.59 | 95.71 | 74.6 | 86.9 | 83.03 | 100 | 57 |

| 10 | , TWCO, , TEA, , (kW/Ton), , , (kW), PRC | 10 | 95.67 | 94.88 | 77.68 | 92.91 | 81.77 | 100 | 49.94 |

| 11 | , TWCO, , TEA, , (kW/Ton), , , (kW), PRC, TRC | 10 | 95.19 | 95.09 | 75.71 | 91.75 | 87.69 | 100 | 68.61 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bezyan, Y.; Nasiri, F.; Nik-Bakht, M. Feature Selection and Fault Detection Under Dynamic Conditions of Chiller Systems. Electronics 2026, 15, 208. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010208

Bezyan Y, Nasiri F, Nik-Bakht M. Feature Selection and Fault Detection Under Dynamic Conditions of Chiller Systems. Electronics. 2026; 15(1):208. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010208

Chicago/Turabian StyleBezyan, Yashar, Fuzhan Nasiri, and Mazdak Nik-Bakht. 2026. "Feature Selection and Fault Detection Under Dynamic Conditions of Chiller Systems" Electronics 15, no. 1: 208. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010208

APA StyleBezyan, Y., Nasiri, F., & Nik-Bakht, M. (2026). Feature Selection and Fault Detection Under Dynamic Conditions of Chiller Systems. Electronics, 15(1), 208. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010208