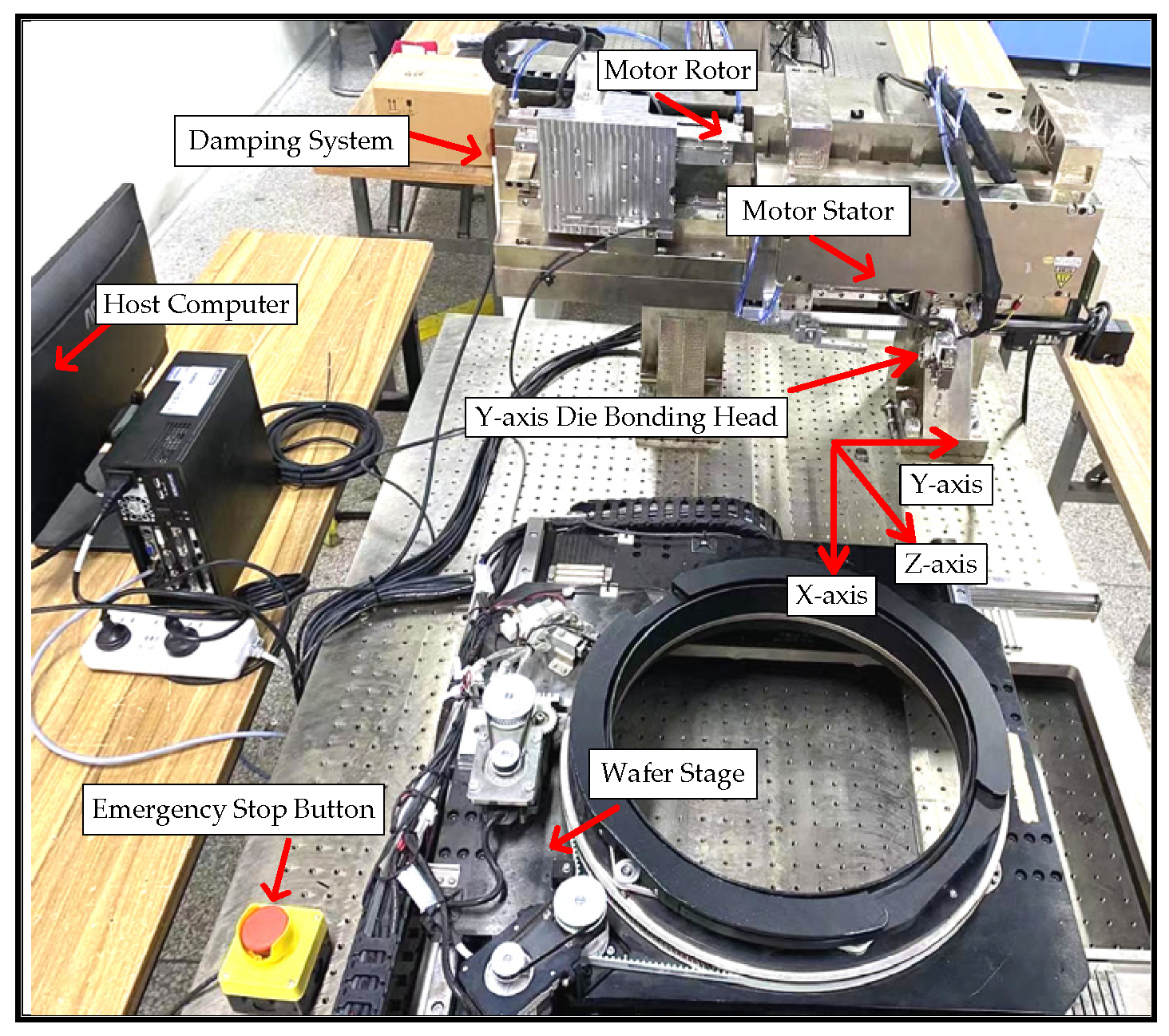

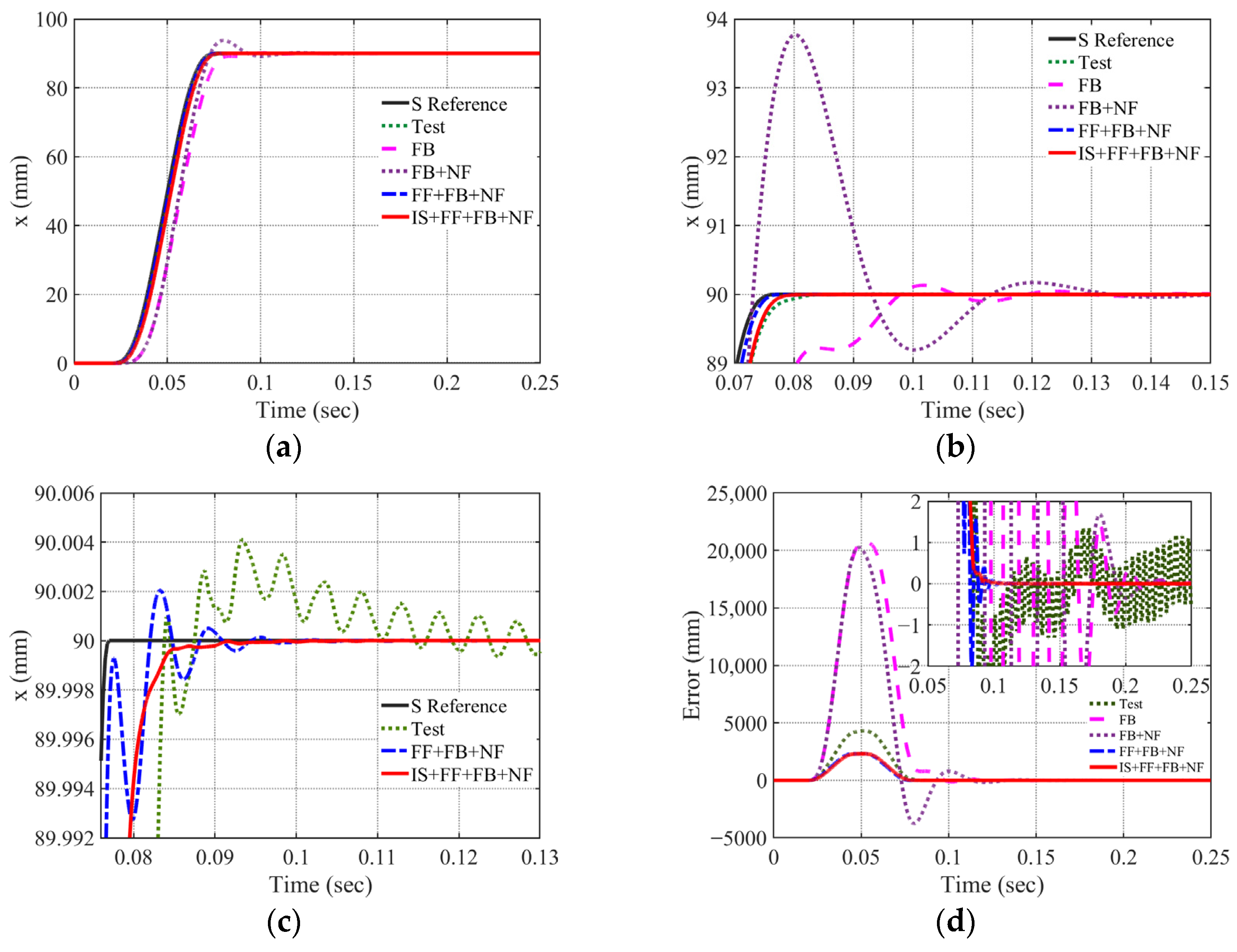

3.2. Implementation on the Linear Motion Stage

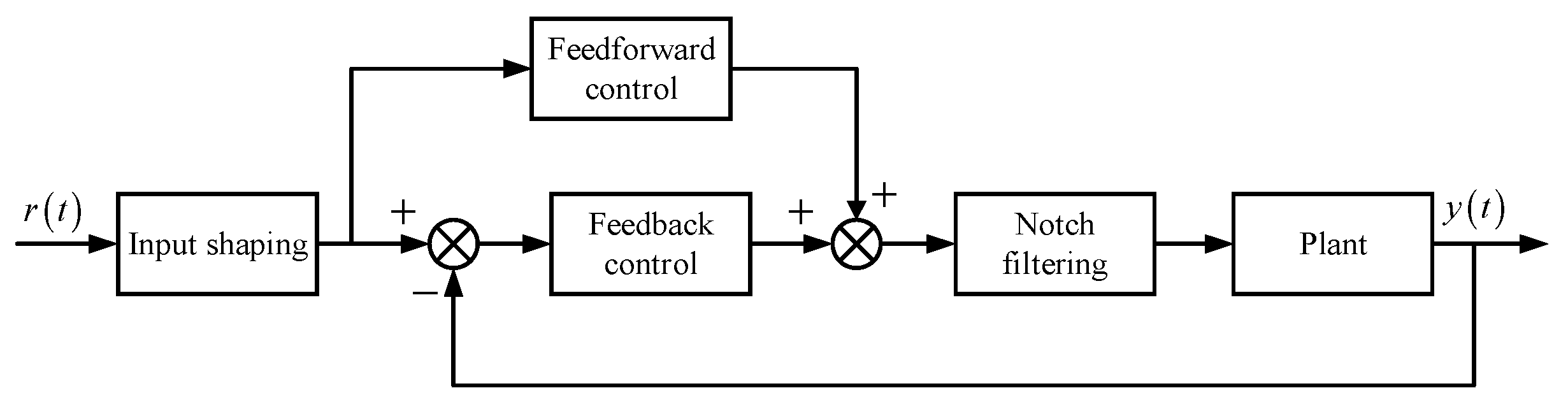

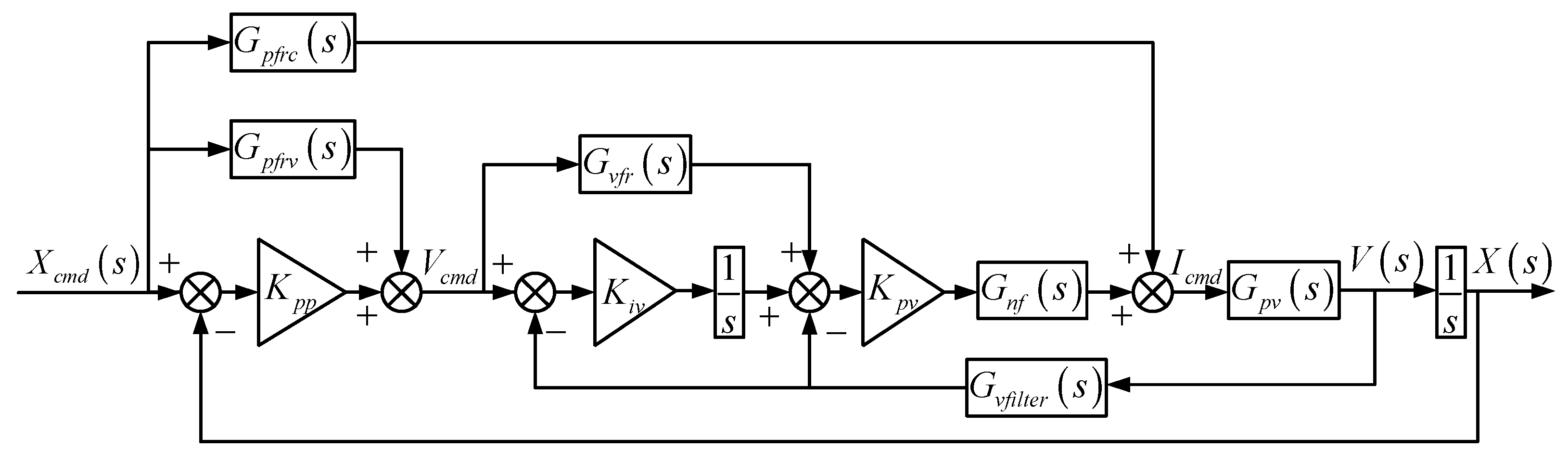

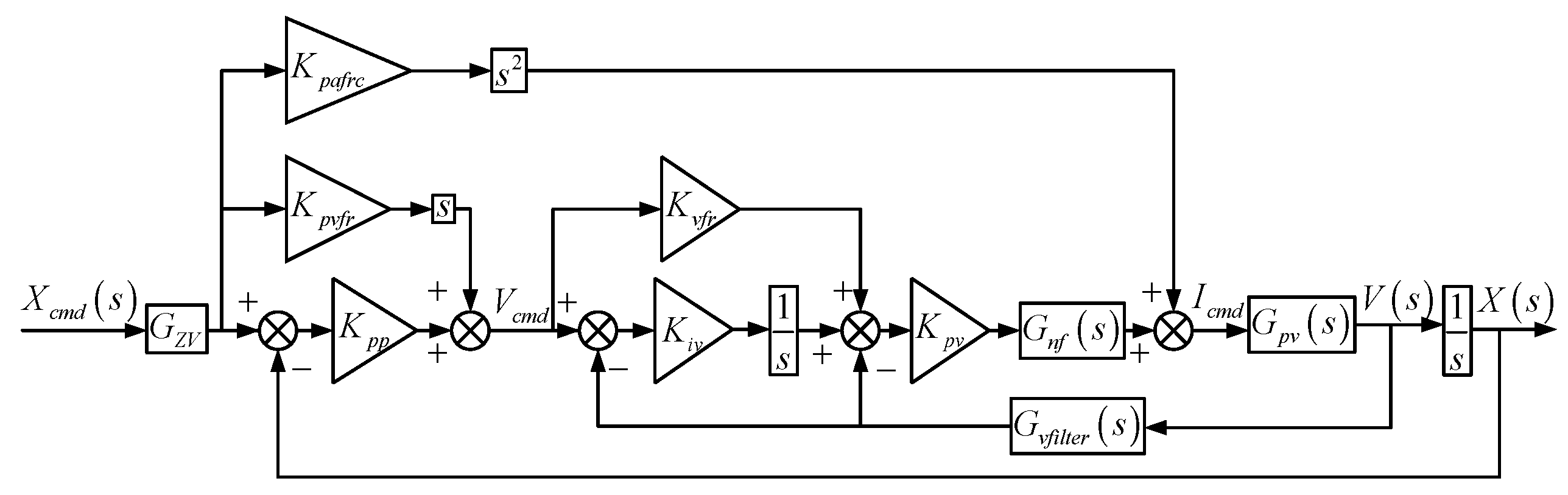

The proposed architecture is applied to the linear motion stage in a manner fully consistent with industrial three-loop servo structures. A cascaded hierarchy is adopted: the outer position loop generates the reference for the inner velocity loop.

The velocity loop utilizes an I–P regulation scheme, which removes the closed-loop zero to improve damping and eliminate overshoot but inherently reduces tracking bandwidth. To mitigate this drawback, FF is incorporated to offset dynamic lag, and an NF is inserted into the control-output path to attenuate dominant mechanical resonances. This coordinated design achieves faster transient response while preserving smooth motion profiles.

The position loop, modeled as a type-I system, is regulated by a proportional controller with gain

. To further enhance dynamic performance, a dual-path feedforward structure is adopted: one path injects compensation into the velocity reference (

), and the other directly into the current command (

). The resulting control architecture is summarized in

Figure 4.

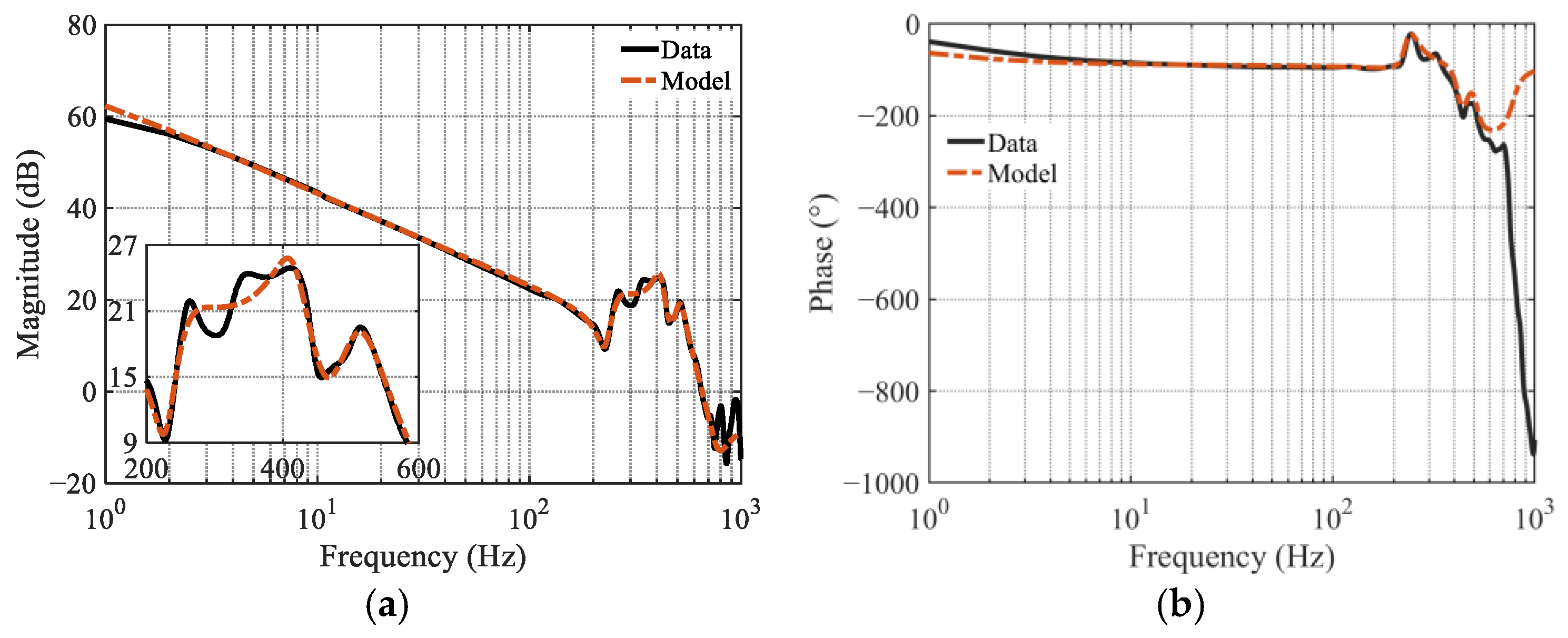

3.2.1. Velocity-Loop Analysis

The closed-loop transfer function of the velocity loop is

where

denotes the velocity-feedback filter, implemented as a first-order filter in this study.

Accordingly, the velocity loop tracking error is

Letting

, the ideal velocity-loop feedforward term becomes

Substituting Equation (7) into Equation (5) yields

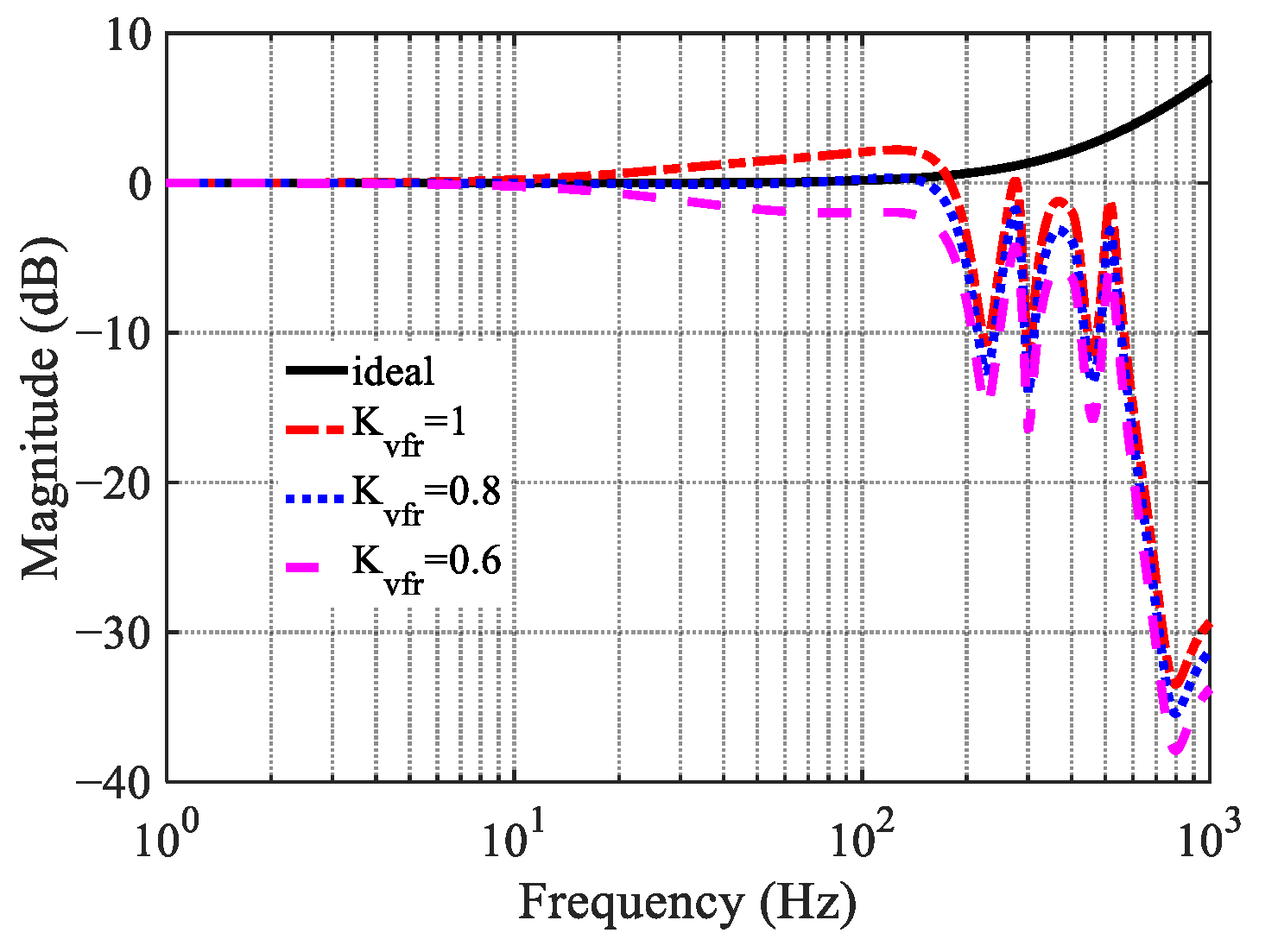

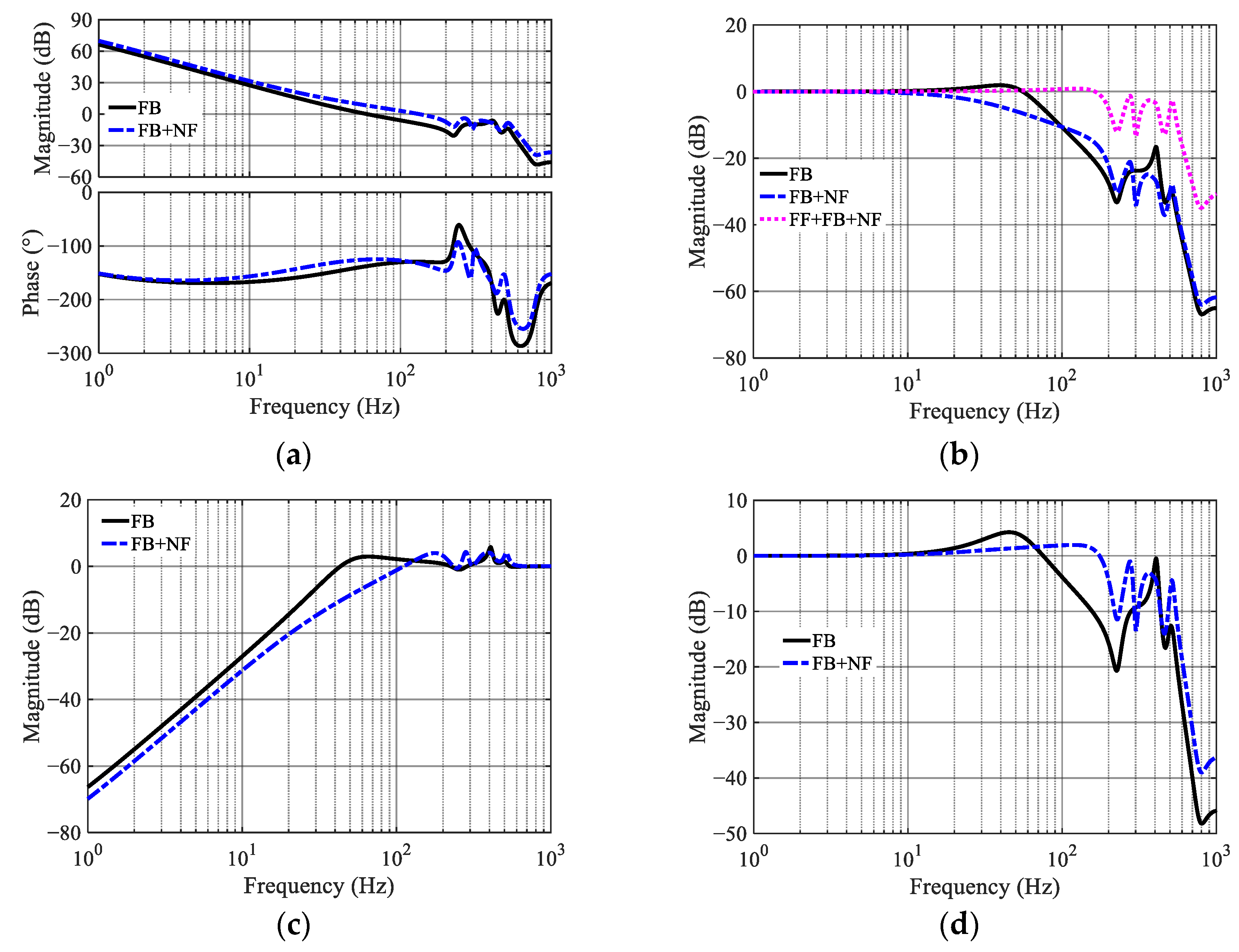

whose closed-loop magnitude response corresponds to the solid black curve in

Figure 5.

However, because the embedded velocity filter prevents the compensated closed-loop from achieving unity gain, the high-frequency magnitude response exceeds 0 dB, which may excite structural modes. To avoid this effect, the feedforward compensator is simplified to a scalar gain

. As shown in

Figure 5, choosing an appropriate

suppresses resonant peaks below 0 dB while maintaining design flexibility. The combined effect of I–P control, proportional FF, and NF expands the control bandwidth and attenuates high-frequency resonances.

3.2.2. Position-Loop Analysis

The closed-loop transfer function from the position reference to output is

yielding the position-loop error

Setting

yields the ideal feedforward terms

Although these ideal expressions ensure unity closed-loop tracking, they depend explicitly on the velocity-loop I–P parameters and the embedded filter, thereby restricting controller-design flexibility. Considering the natural kinematic relations among position, velocity, and current in linear motors, these two feedforward terms are simplified to

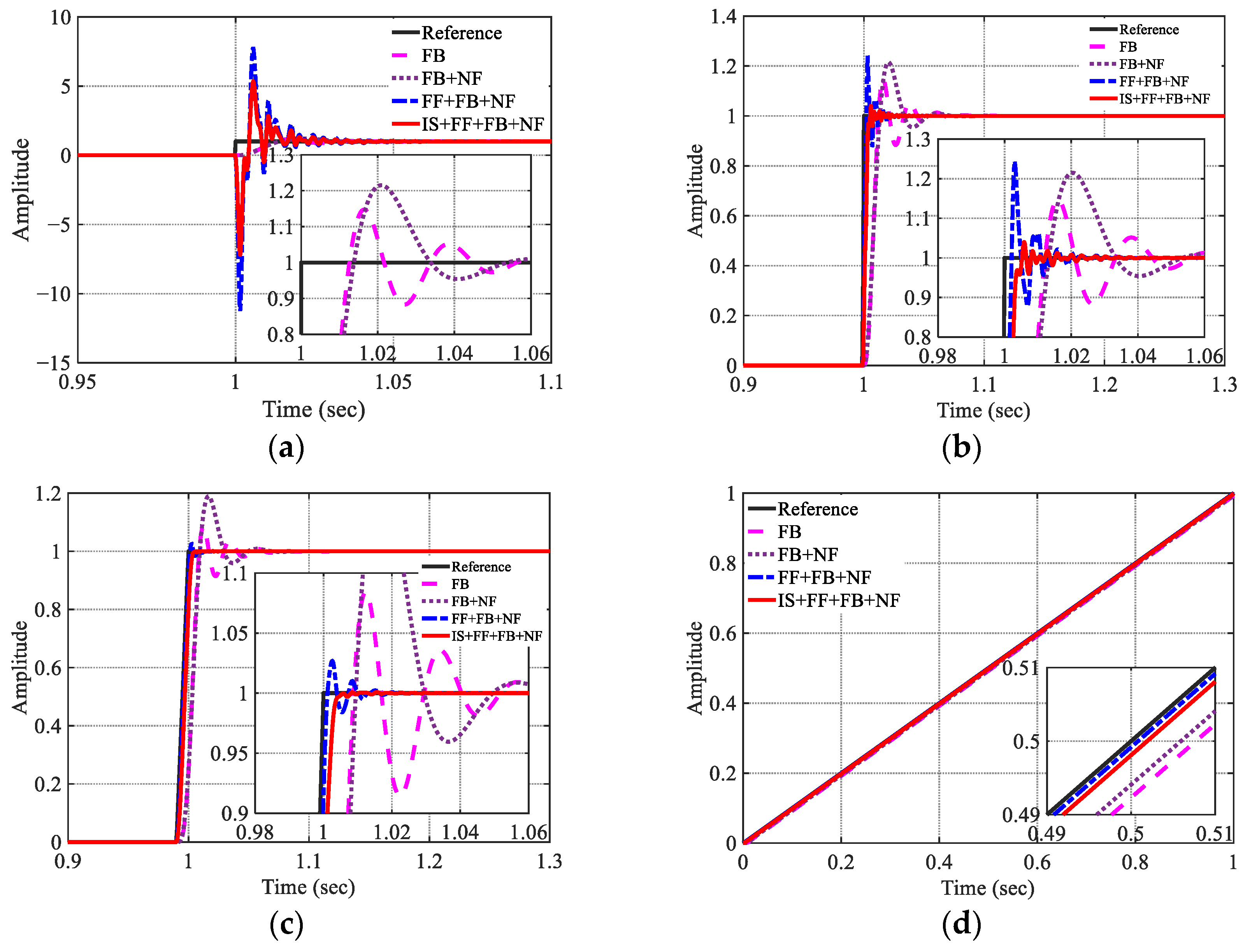

where velocity feedforward is applied to the velocity reference and acceleration feedforward to the current reference. This simplification improves tuning flexibility and supports practical implementation. Integrating IS into this scheme yields the complete synergistic architecture shown in

Figure 6.

To meet the positioning requirements of shorter settling time while suppressing resonances, a ZV input shaper is adopted, whose analytical form is

3.3. Frequency-Domain Parameter Synthesis

The presence of high-frequency flexible modes renders root-locus design unsuitable; therefore, all controller parameters for both velocity and position loops are synthesized in the frequency domain. The design procedure consists of identifying the target gain crossover frequency satisfying the phase margin (PM) requirement on the uncompensated Bode plot, and adjusting controller gains such that the compensated open loop crosses 0 dB exactly at .

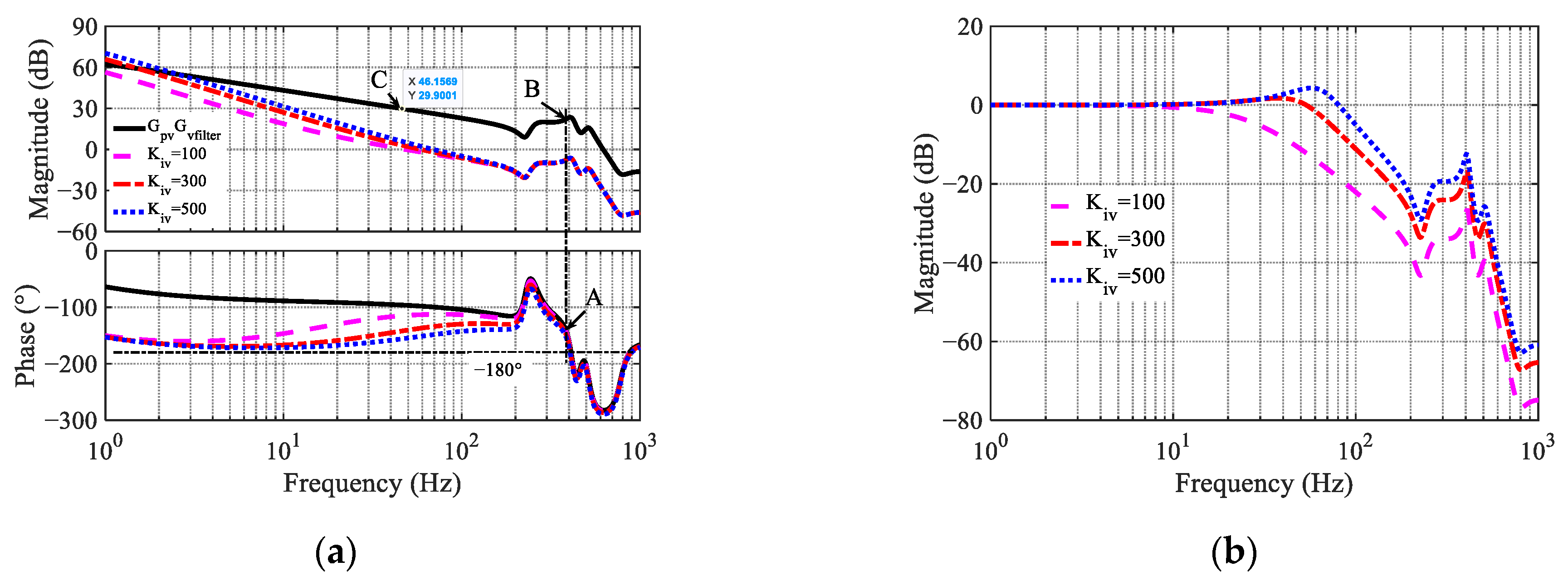

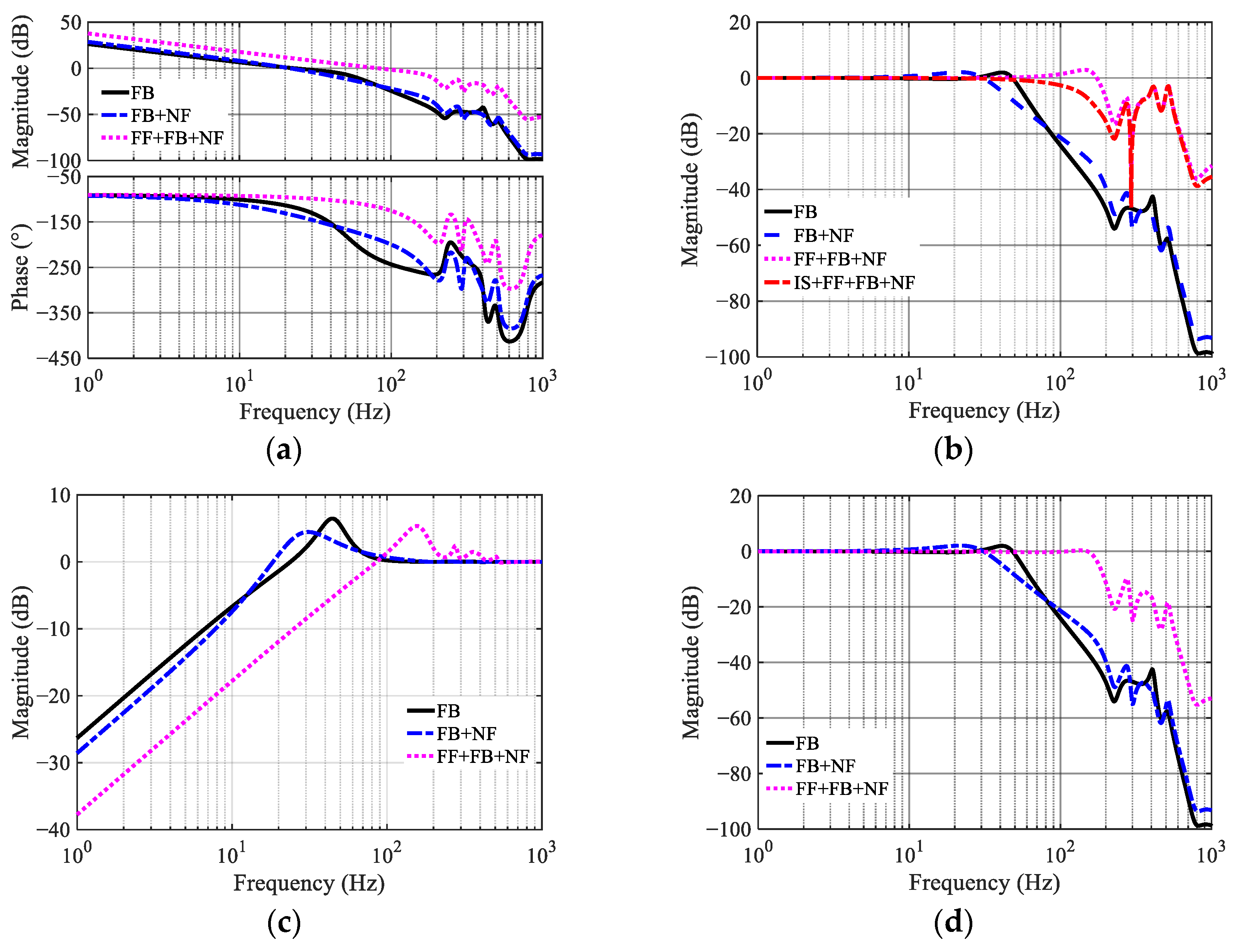

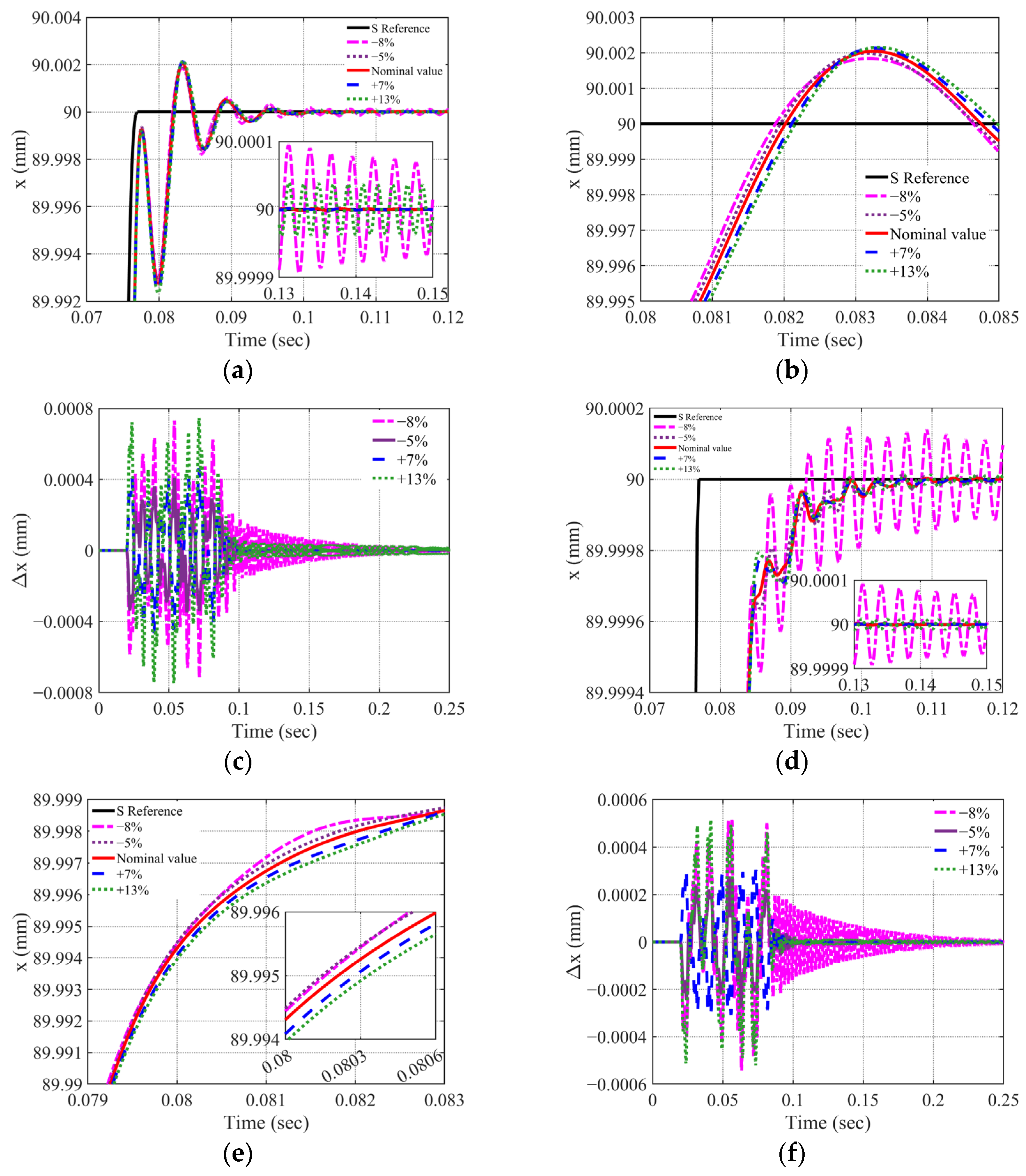

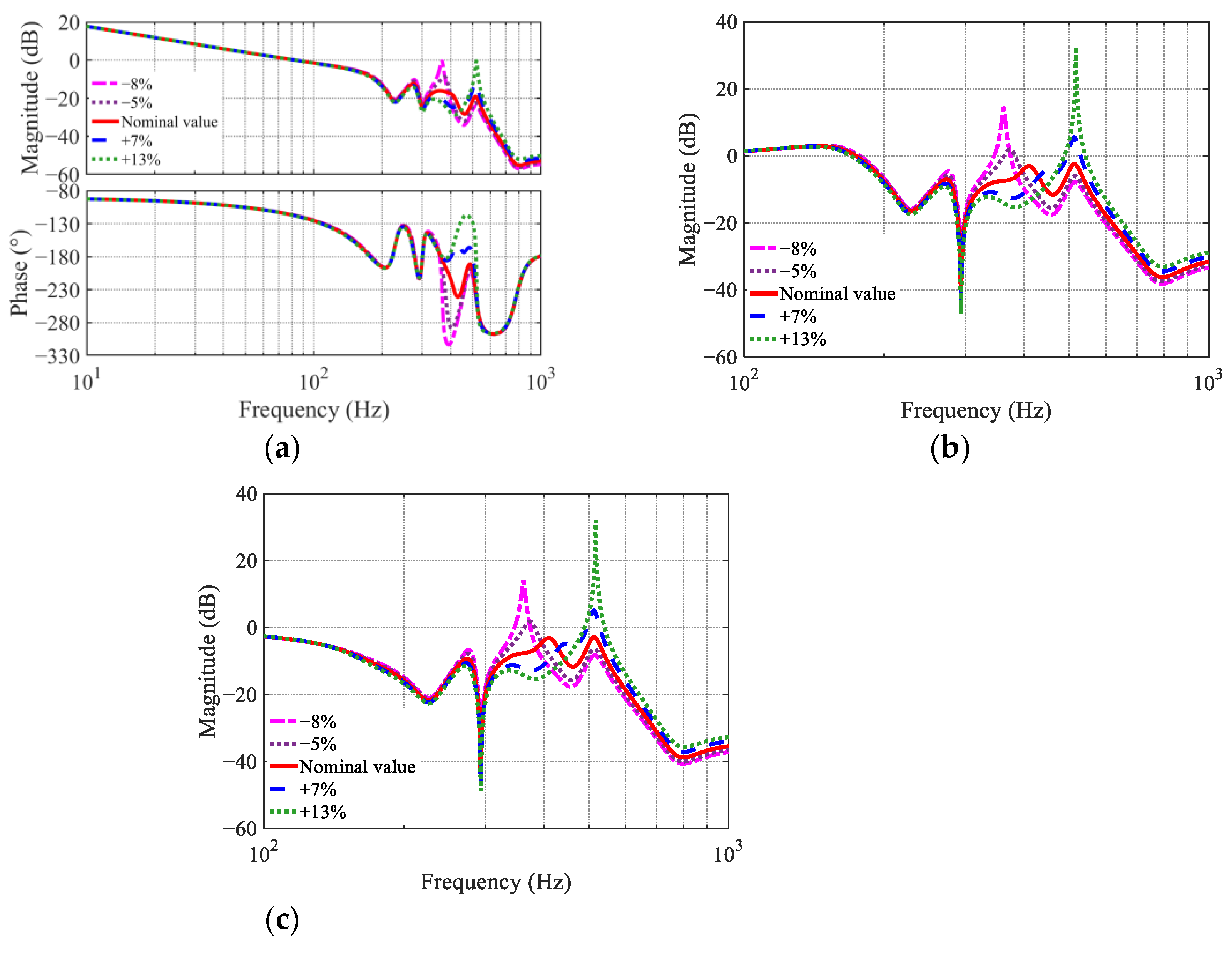

For the velocity loop, ignoring NF dynamics, the uncompensated forward path exhibits a resonant peak at (406.309 Hz, 23.582 dB), as shown in

Figure 7. Point A in

Figure 7 satisfies the PM requirement, and the corresponding Point B defines

. However, the resonant peak remains above 0 dB at this frequency, risking excitation of structural modes. Because the high-frequency resonance has not yet been compensated, a PI-based design that only satisfies the phase-margin criterion fails to stabilize the system.

To resolve this issue, the gain margin (GM) requirement is used to determine

. Point C (46.1569 Hz, 29.9001 dB) on the magnitude plot satisfies the GM specification, yielding the I–P proportional gain:

The integral gain strongly affects the PM, resonant peak (

), and control bandwidth

. Comparative Bode analyses for

= {100, 300, 500} are shown in

Figure 7, and the corresponding frequency-domain performance metrics are summarized in

Table 2.

Table 2 reveals a clear trade-off between system stability and responsiveness. Small integral gains ensure adequate stability margins but restrict the achievable control bandwidth, while excessively large gains reduce the PM to unsafe levels. An intermediate gain value is found to achieve a balanced performance (e.g., PM = 43.16°, GM = 6.27 dB) while effectively suppressing the mechanical resonant peak to −16.94 dB.

To generalize this empirical observation into a systematic and reproducible design methodology, a frequency-domain synthesis procedure is formulated to explicitly resolve conflicts between performance enhancement and stability preservation. The controller synthesis follows a constrained optimization logic, in which the primary objective is to maximize the (and hence the control bandwidth), subject to predefined stability margin constraints.

In practice, a fundamental conflict often arises: increasing improves tracking speed but requires a higher loop gain, which may either elevate the resonant peak above the 0 dB stability limit (violating the GM constraint) or necessitate a wider NF. However, an excessively wide NF introduces additional phase lag at , potentially violating the PM requirement. When such conflicts occur, a priority-based selection rule is applied as follows:

Step 1: Determine the minimum notch depth and bandwidth required to attenuate the dominant resonant peak below a safety threshold (e.g., −6 dB) in the open-loop frequency response.

Step 2: Evaluate the resulting phase lag introduced by the NF at the trial .

Step 3: If the remaining PM does not satisfy the design specification, is iteratively reduced until both PM and GM constraints are simultaneously met.

Final Selection: The final crossover frequency is selected at the “knee point” of the sensitivity peak curve, where further increases in lead to a rapid growth of sensitivity amplification. The point represents the optimal compromise between transient responsiveness and vibration robustness.

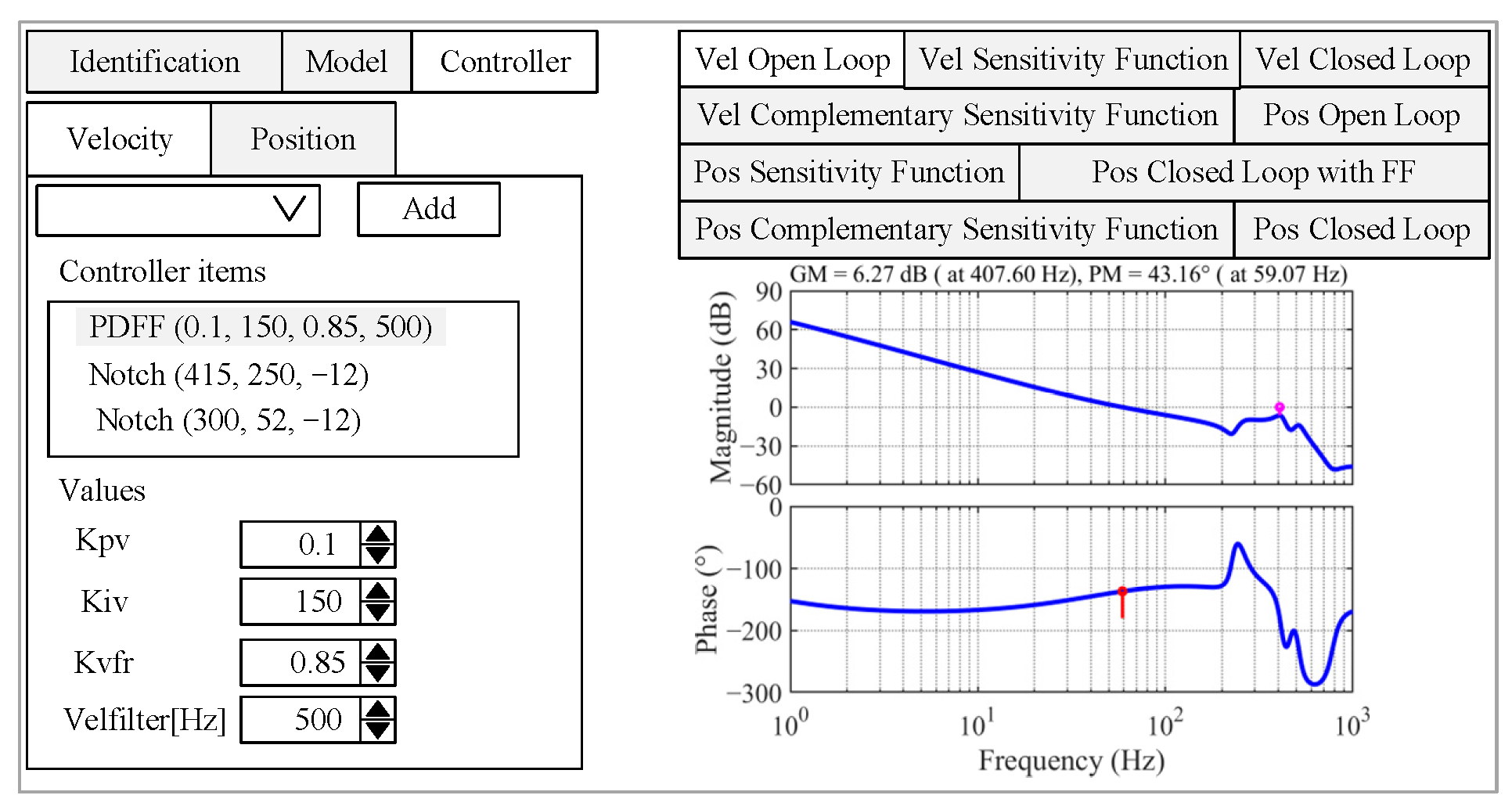

To facilitate the integrated design of IS, FF, FB, and NF—whose interactions critically influence loop stability, an interactive graphical user interface (GUI) (

Figure 8) is employed, where the blue curve represents the open-loop Bode response, and the red line represents the stability margin. This environment enables a systematic exploration of the stability–performance trade-offs and ensures that all resonant peaks remain rigorously below the 0 dB stability limit throughout the design process. Notably, although the current implementation employs a GUI for visualization and interactive analysis, the underlying three-step synthesis procedure is strictly algorithmic rather than heuristic. Specifically, the PM, GM, and sensitivity peak are formulated as explicit quantitative constraints, while the crossover frequency is treated as the optimization variable. Under this formulation, the design process can be fully automated using iterative or search-based algorithms, without reliance on manual trial-and-error or subjective tuning by experienced engineers. The GUI therefore serves primarily as a diagnostic and visualization tool, rather than a prerequisite for controller synthesis.