Investigation of Ring-Shaped TENG for Optoelectronic Information Communication

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experiment

2.1. Fabrication of Ring-Shaped TENG

2.2. Fabrication of Silicon PIN Photodetectors

2.3. Self-Powered Silicon PIN Detector System

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, S.; Xu, L.D.; Zhao, S. The internet of things: A survey. Inf. Syst. Front. 2015, 17, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.S.; Park, J.M.; Yoon, Y.S.; Koo, J.G.; Kim, B.W.; Yoon, C.J.; No, K.S. Effects of the resistivity and crystal orientation of the silicon PIN detector on the dark current and radiation response characteristics. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE Nuclear Science Symposium Conference Record, San Diego, CA, USA, 29 October–4 November 2006; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2006; Volume 2, pp. 1068–1072. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Yu, M.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, H.; Huang, Y.; Jin, Y. Fabrication of 1.5 mm thickness silicon pin fast neutron detector with guard ring structure. In Proceedings of the 2016 China Semiconductor Technology International Conference (CSTIC), Shanghai, China, 13–14 March 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; Volume 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld, A.B.; Yudelev, M.; Lerch, M.L.F.; Cornelius, I.; Griffin, P.; Perevertailo, V.L.; Anokhin, I.E.; Zinets, O.S.; Khivrich, V.I.; Pinkovskaya, M.; et al. Neutron dosimetry with planar silicon pin diodes. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2003, 50, 2367–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.C.; Yu, M.; Fan, C.; Yang, F.D.; Zhou, C.Z.; Wang, J.Y.; Jin, Y.F. New PIN diode structure for neutron dose measurement. J. Instrum. 2012, 7, 08019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Zhao, J.; Xiao, W. PIN silicon diode fast neutron detector. Radiat. Prot. Dosim. 2005, 117, 365–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Tian, D.; Wang, S.; Yu, M.; Jin, Y. Research on the structure of ultrathin Si PIN detector. In Proceedings of the 8th Annual IEEE International Conference on Nano/Micro Engineered and Molecular Systems, Suzhou, China, 7–10 April 2013; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 629–632. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.-Z.; Yu, M.; Shi, B.-H.; Qi, L.; Wang, S.-N.; Hu, A.-Q.; Du, H.; Wang, J.-Y.; Jin, Y.-F.; Yang, B. Study on geometry of silicon PIN radiation detector for breakdown voltage improvement. Int. J. Nanotechnol. 2015, 12, 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soref, R.A. Silicon-based optoelectronics. Proc. IEEE 1993, 81, 1687–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalali, B.; Yegnanarayanan, S.; Yoon, T.; Yoshimoto, T.; Rendina, I.; Coppinger, F. Advances in silicon-on-insulator optoelectronics. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 1998, 4, 938–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canham, L.T.; Cox, T.I.; Loni, A.; Simons, A.J. Progress towards silicon optoelectronics using porous silicon technology. Appl. Surf. Sci. 1996, 102, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Camacho-Aguilera, R.; Bessette, J.T.; Sun, X.C.; Wang, X.X.; Cai, Y.; Kimerling, L.C.; Michel, J. Ge-on-Si optoelectronics. Thin Solid Film. 2012, 520, 3354–3360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youngblood, N.; Li, M. Integration of 2D materials on a silicon photonics platform for optoelectronics applications. Nanophotonics 2017, 6, 1205–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douhan, R.; Lozovoy, K.; Kokhanenko, A.; DeebORCID, H.; Dirko, V.; Khomyakova, K. Recent advances in Si-compatible nanostructured photodetectors. Technologies 2023, 11, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Wang, M.; Fu, J.; Li, Z.; Shaikh, M.S.; Li, Y.; Nie, C.; Sun, F.; Tang, L.; Yang, J.; et al. Ultrahigh photogain short-wave infrared detectors enabled by integrating graphene and hyperdoped silicon. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 12777–12785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Wei, J.; Sun, F.; Nie, C.; Fu, J.; Shi, H.; Sun, J.; Wei, X.; Qiu, C. Enhanced photogating effect in graphene photodetectors via potential fluctuation engineering. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 4458–4466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, J.; Guo, Z.; Nie, C.; Sun, F.; Li, G.; Feng, S.; Wei, X. Schottky infrared detectors with optically tunable barriers beyond the internal photoemission limit. Innovation 2024, 5, 100600. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, J.; Nie, C.; Sun, F.; Li, G.; Shi, H.; Wei, X. Bionic visual-audio photodetectors with in-sensor perception and preprocessing. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadk8199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.; Shao, J.; Wang, Z.L. Triboelectric nanogenerators. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2023, 3, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, P.; Sahay, K.; Verma, A.; Maurya, D.K.; Yadav, B.C. Applications of multifunctional triboelectric nanogenerator (TENG) devices: Materials and prospects. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2023, 7, 3796–3831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.L.; Lin, L.; Chen, J.; Niu, S.M.; Zi, Y.L. Triboelectric nanogenerator: Vertical contact-separation mode. In Triboelectric Nanogenerators; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 23–47. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, F.-R.; Tian, Z.-Q.; Wang, Z.L. Flexible triboelectric generator. Nano Energy 2012, 1, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Lin, L.; Wang, Z.L. Nanoscale triboelectric-effect-enabled energy conversion for sustainably powering portable electronics. Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 6339–6346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Lin, L.; Zhang, Y.; Jing, Q.; Hou, T.-C.; Wang, Z. Self-powered magnetic sensor based on a triboelectric nanogenerator. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 10378–10383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bairagi, S.; Islam, S.; Kumar, C.; Babu, A.; Aliyana, A.; Stylios, G.; Pillai, S.C.; Mulvihill, D.M. Wearable nanocomposite textile-based piezoelectric and triboelectric nanogenerators: Progress and perspectives. Nano Energy 2023, 118, 108962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Lü, C.; Luo, J.; Shen, L. A real-time quantitative acceleration monitoring method based on triboelectric nanogenerator for bridge cable vibration. Nano Energy 2023, 118, 108960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wang, C.; Zeng, Q.; Gu, G.; Wang, X.; Cheng, G.; Du, Z. A real-time, self-powered wireless pressure sensing system with efficient coupling energy harvester, sensing, and communication modules. Nano Energy 2024, 125, 109533. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Gu, G.; Qin, H.; Li, S.; Shang, W.; Wang, T.; Zhang, B.; Cui, P.; Guo, J.; Yang, F.; et al. Measuring the actual voltage of a triboelectric nanogenerator using the non-grounded method. Nano Energy 2020, 77, 105108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, H.; Zhou, W.; Tuo, L.; Liang, C.; Chen, C.; Li, S.; Qu, H.; Wan, L.; Liu, G. Tensegrity triboelectric nanogenerator for broadband-blue energy harvesting in all-sea areas. Nano Energy 2023, 117, 108906. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Zhou, L.; Gao, Y.; Yang, P.; Liu, D.; Qiao, W.; Zhang, B.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J. Achieving Ultra-High Voltage (≈10 kV) Triboelectric Nanogenerators. Adv. Energy Mater. 2023, 13, 2300410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, B.; Gao, Y.; Yuan, W.; Li, X.; Zhou, L.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J. A high-output silk-based triboelectric nanogenerator with durability and humidity resistance. Nano Energy 2023, 108, 108244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Zhou, Z.; Shang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zi, Y. Metallic glass-based triboelectric nanogenerators. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Gao, Y.; Zhou, L.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z. Recent advances in high-performance triboelectric nanogenerators. Nano Res. 2023, 16, 11698–117179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Guo, X.; Zhu, M.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, Z.; He, T.; Lee, C. Triboelectric nanogenerator enabled wearable sensors and electronics for sustainable internet of things integrated green earth. Adv. Energy Mater. 2023, 13, 2203040. [Google Scholar]

- Gai, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Li, Z. Advances in health rehabilitation devices based on triboelectric nanogenerators. Nano Energy 2023, 116, 108787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Kim, D.-S.; Lee, D.-W. On-vehicle triboelectric nanogenerator enabled self-powered sensor for tire pressure monitoring. Nano Energy 2018, 49, 126–136. [Google Scholar]

- Rasel, M.S.; Maharjan, P.; Salauddin, M.; Rahman, M.T.; Cho, H.O.; Kim, J.W.; Park, J.Y. An impedance tunable and highly efficient triboelectric nanogenerator for large-scale, ultra-sensitive pressure sensing applications. Nano Energy 2018, 49, 603–613. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.; Huang, M.; Zou, G.; Li, X.; Wang, Y. Self-powered vibration sensor based on the coupling of dual-mode triboelectric nanogenerator and non-contact electromagnetic generator. Nano Energy 2023, 111, 108356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Zheng, Q.; Hou, W.; Zheng, L.; Li, H. A self-powered vibration sensor based on the coupling of triboelectric nanogenerator and electromagnetic generator. Nano Energy 2022, 97, 107164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, K.; Liu, Y.; Lu, X.; Cheng, T. Arc-shaped flutter-driven wind speed sensor based on triboelectric nanogenerator for unmanned aerial vehicle. Nano Energy 2022, 104, 107871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Fu, S.; Zuo, X.; Zeng, J.; Shan, C.; He, W.; Li, W.; Hu, C. Moisture resistant and stable wireless wind speed sensing system based on triboelectric nanogenerator with charge-excitation strategy. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2207498. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, K.; Gu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Yang, F.; Zhao, L.; Zheng, M.; Cheng, G.; Du, Z. The self-powered CO2 gas sensor based on gas discharge induced by triboelectric nanogenerator. Nano Energy 2018, 53, 898–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Cui, J.; Zheng, Y.; Bai, S.; Hao, C.; Xue, C. A self-powered inert-gas sensor based on gas ionization driven by a triboelectric nanogenerator. Nano Energy 2023, 106, 108083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Shi, B.; Li, Z.; Wang, Z. Recent progress on piezoelectric and triboelectric energy harvesters in biomedical systems. Adv. Sci. 2017, 4, 1700029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Gu, G.; Shang, W.; Gan, J.; Zhang, W.; Luo, H.; Zhang, B.; Cui, P.; Guo, J.; Yang, F.; et al. A self-powered photodetector using a pulsed triboelectric nanogenerator for actual working environments with random mechanical stimuli. Nano Energy 2021, 90, 106518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.M.; Crispin, X. The past, present, and future of piezoelectric fluoropolymers: Towards efficient and robust wearable nanogenerators. Nano Res. Energy 2023, 2, e9120076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; He, J.; Zheng, Y.; Wu, J.; Pan, C.; Zi, Y.; Cui, H.; Li, X. High-performance triboelectric nanogenerator based on theoretical analysis and ferroelectric nanocomposites and its high-voltage applications. Nano Res. Energy 2023, 2, e9120074. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Guo, X.; Lee, C. Promoting smart cities into the 5G era with multi-field internet of things (IoT) applications powered with advanced mechanical energy harvesters. Nano Energy 2021, 88, 106304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xia, K.; Liu, J.; Li, T.; Zhao, X.; Shu, B.; Li, H.; Guo, J.; Yu, M.; Tang, W.; et al. Self-powered silicon PIN photoelectric detection system based on triboelectric nanogenerator. Nano Energy 2020, 69, 104461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Lu, Y.; Zhao, S.; Hu, L.; Jiang, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Gao, H.; Li, Y.; Yuan, M.; et al. A wind vector detecting system based on triboelectric and photoelectric sensors for simultaneously monitoring wind speed and direction. Nano Energy 2021, 89, 106382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wang, X.; Song, Y.; Cao, R.; Wang, L.; Yan, Z.; Shan, G. Self-powered forest fire alarm system based on impedance matching effect between triboelectric nanogenerator and thermosensitive sensor. Nano Energy 2020, 73, 104843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, G.; Gu, G.; Shang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Wang, C.; Fang, D.; Cheng, G.; Du, Z. The self-powered agricultural sensing system with 1.7 km wireless multichannel signal transmission using a pulsed triboelectric nanogenerator of corn husk composite film. Nano Energy 2022, 102, 107699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Wu, C.; Zi, Y.; Zou, H.; Wang, J.; Cheng, J.; Wang, A.C.; Wang, Z. Self-powered wireless optical transmission of mechanical agitation signals. Nano Energy 2018, 47, 566–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.; Thapa, K.; Ojha, G.P.; Seo, M.K.; Shin, K.H.; Kim, S.H.; Sohn, J.I. Metal-organic frameworks-based triboelectric nanogenerator powered visible light communication system for wireless human machine interactions. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 452, 139209. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.L. From contact electrification to triboelectric nanogenerators. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2021, 84, 096502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Liu, L.; Yin, D.; Su, Y.; Hu, T.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, T.; Shi, Q.; Tao, K. A vehicle-to-everything (V2X) interaction system for intelligent transportation based on energy harvesting–sensing cooperation triboelectric nanogenerator. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2025, 7, 7419–7431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhao, X.; Hu, T.; Liang, F.; Guo, B.; Tao, K. Deep-learning-assisted self-powered wireless environmental monitoring system based on triboelectric nanogenerators with multiple sensing capabilities. Nano Energy 2024, 132, 110301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Yin, D.; Zhao, X.; Hu, T.; Liu, L. Exploration of advanced applications of triboelectric nanogenerator-based self-powered sensors in the era of artificial intelligence. Sensors 2025, 25, 2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Hu, T.; Zhao, X.; Su, Y.; Yin, D.; Lee, C.; Wang, Z. Innovative smart gloves with phalanges-based triboelectric sensors as a dexterous teaching interface for embodied artificial intelligence. Nano Energy 2025, 133, 110491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

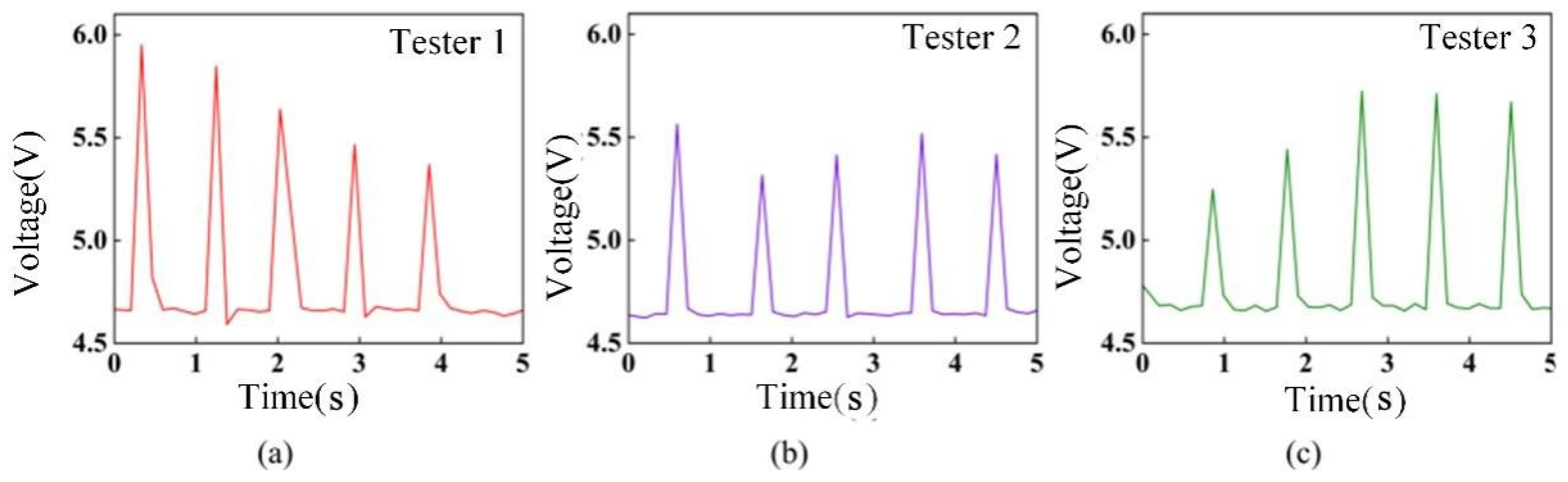

| TENG’s Serial Number | The Range of the Peak Signal’s Magnitude | Corresponding Logical Signal |

|---|---|---|

| TENG 1 | 6.0∼7.0 | 1 |

| TENG 2 | 5.0∼6.0 | 0 |

| TENG 3 | 4.7∼5.0 | pause |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yang, D.; Wang, J.; Zhang, M.; Li, H.; Wang, L.; Yuan, R.; Zhu, Z. Investigation of Ring-Shaped TENG for Optoelectronic Information Communication. Electronics 2026, 15, 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010142

Yang D, Wang J, Zhang M, Li H, Wang L, Yuan R, Zhu Z. Investigation of Ring-Shaped TENG for Optoelectronic Information Communication. Electronics. 2026; 15(1):142. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010142

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Dongxin, Jingming Wang, Manyun Zhang, Hao Li, Liu Wang, Rui Yuan, and Zhiyuan Zhu. 2026. "Investigation of Ring-Shaped TENG for Optoelectronic Information Communication" Electronics 15, no. 1: 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010142

APA StyleYang, D., Wang, J., Zhang, M., Li, H., Wang, L., Yuan, R., & Zhu, Z. (2026). Investigation of Ring-Shaped TENG for Optoelectronic Information Communication. Electronics, 15(1), 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010142