RGB Fusion of Multiple Radar Sensors for Deep Learning-Based Traffic Hand Gesture Recognition

Abstract

1. Introduction

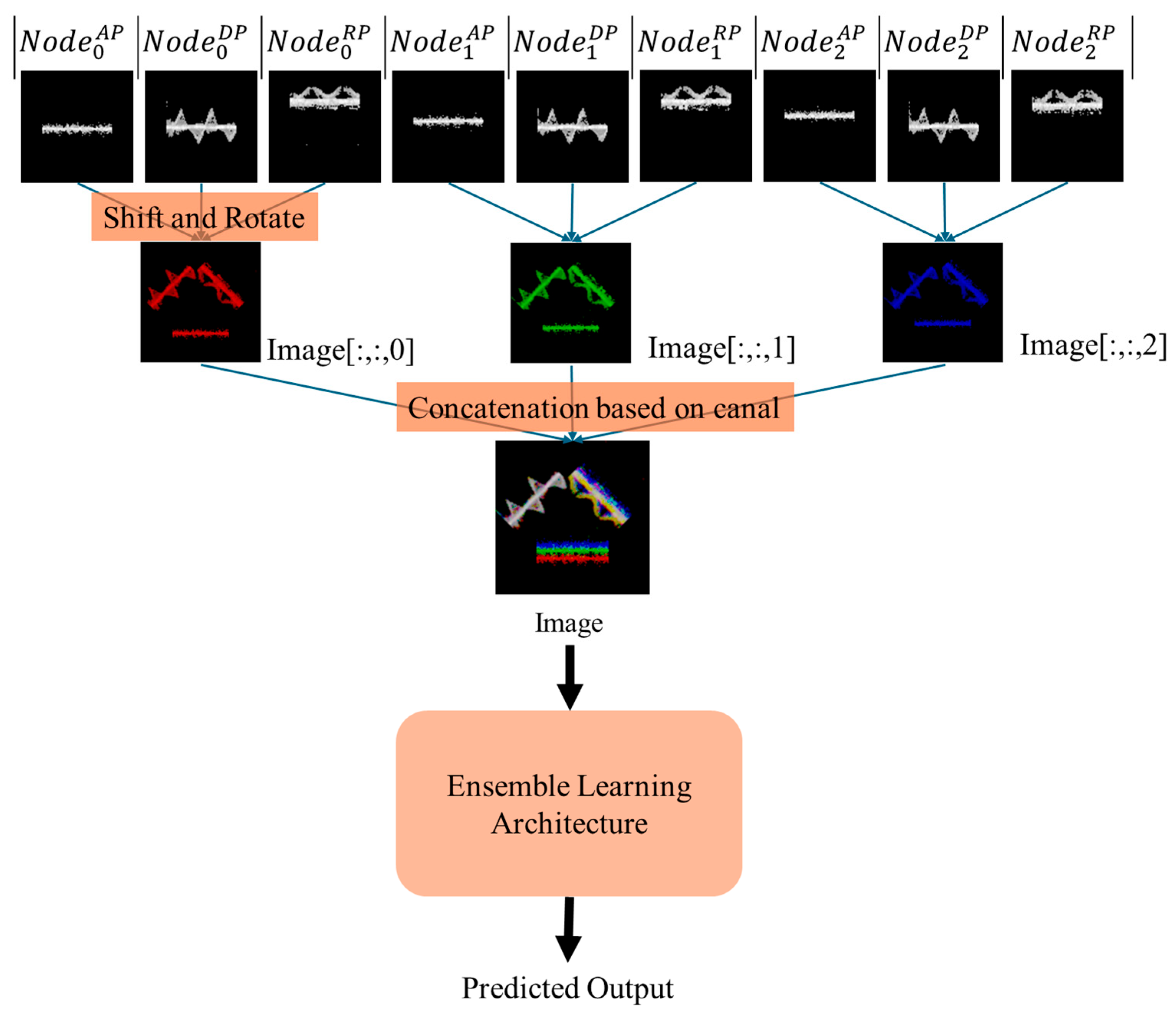

- A novel fusion strategy for the combination of different radar sensors and measured parameters is proposed. In this strategy, nine different grayscale radar images are converted into an RGB image by shifting, rotating, and adding approaches. In this way, data loss is minimized and provides a powerful input image for the deep learning model.

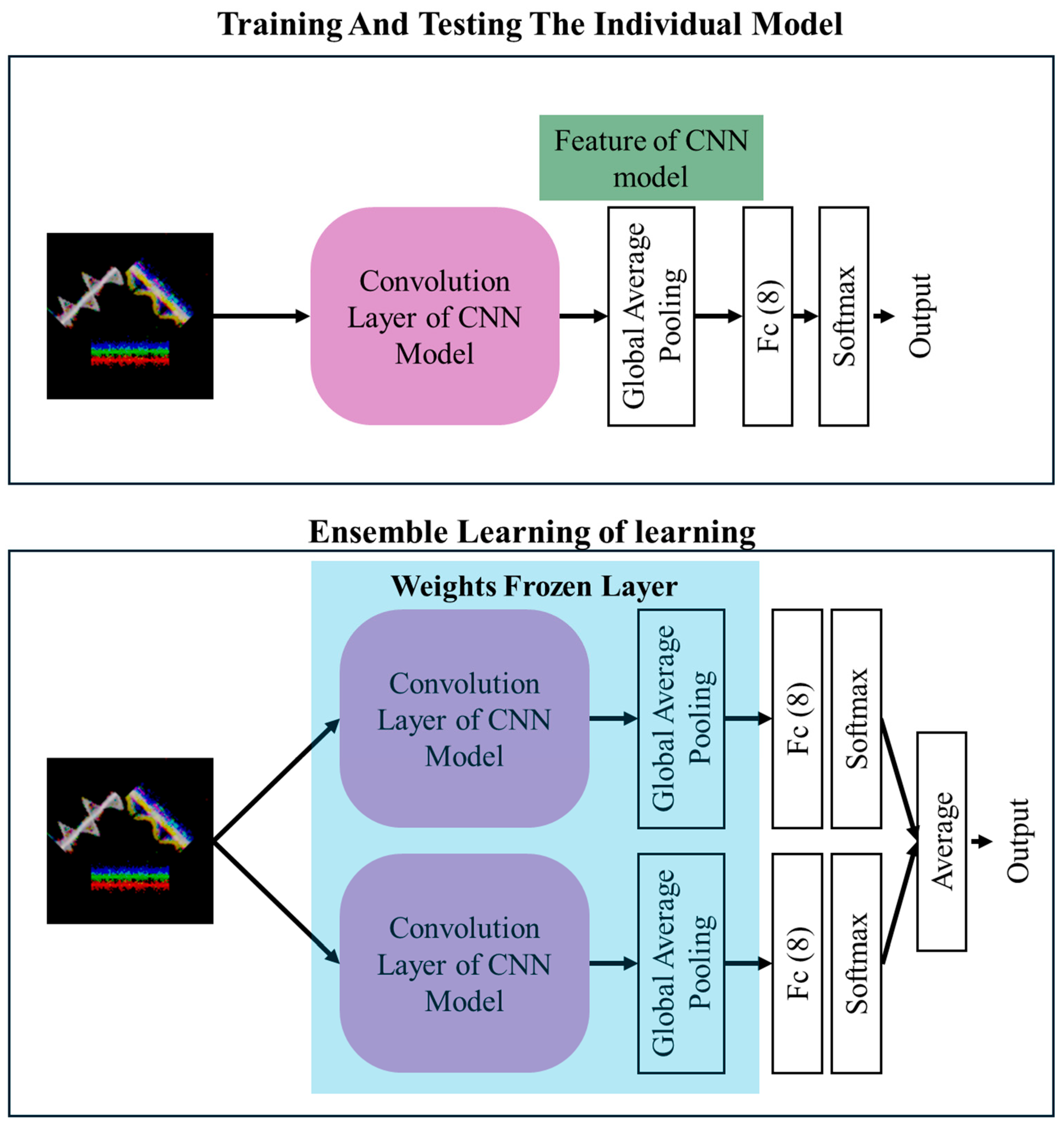

- A simple and effective ensemble learning approach was developed using the synthesized RGB radar image. This approach achieved high performance by combining the strengths of previously proposed deep learning models.

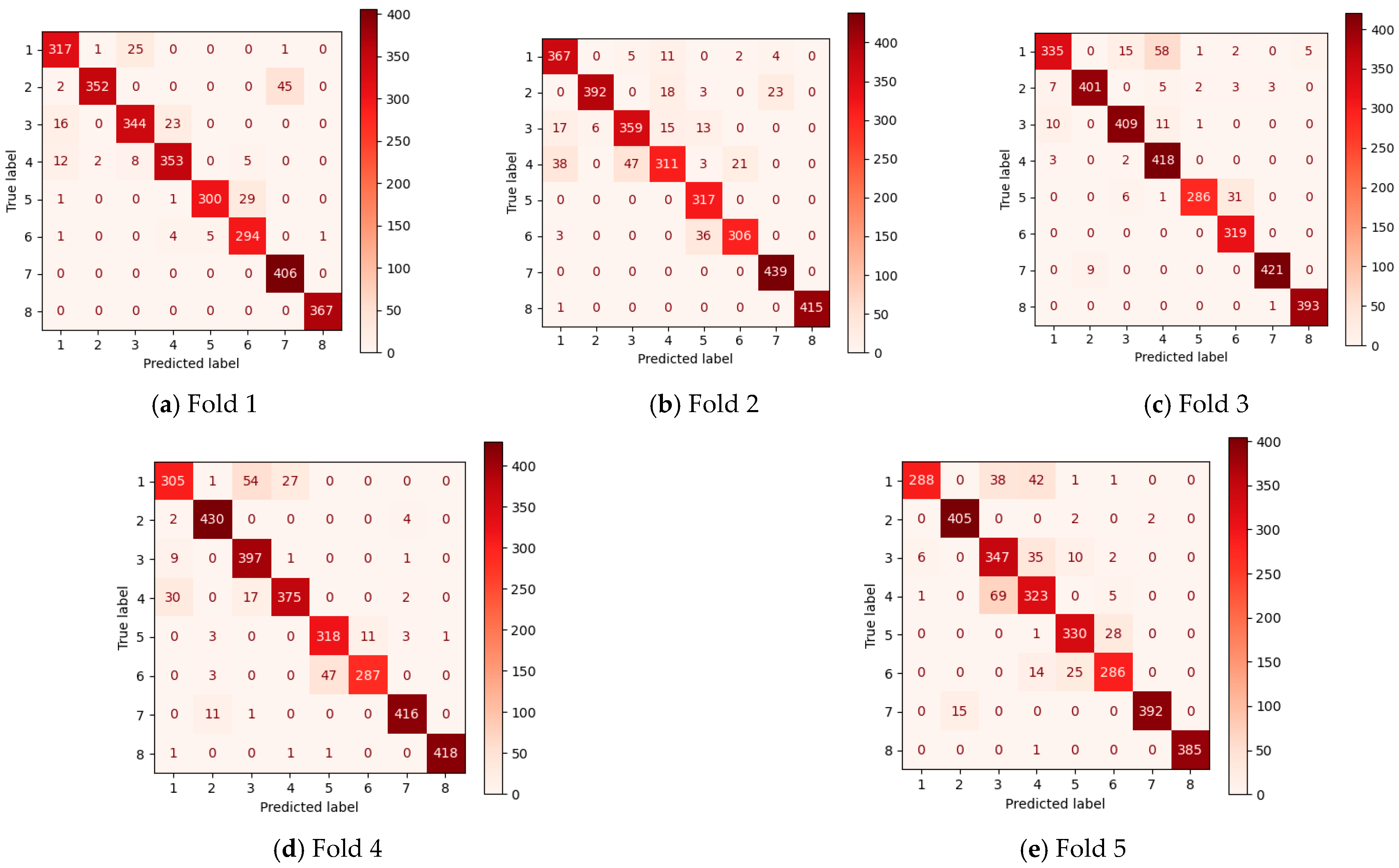

- Comprehensive experimental validation through systematic comparison of individual grayscale radar images, multiple CNN architectures, and ensemble configurations is carried out, demonstrating that the proposed VGG19 + ResNet50 ensemble achieves 92.55% accuracy, surpassing existing literature benchmarks.

2. Proposed Method

2.1. Construction of the Color Radar Images

| Algorithm 1. Proposed Rotation Shift-Based RGB Radar Image Construction Pipeline |

| Input: Nine 64 × 64 grayscale radar images: AP0, DP0, RP0 (Node 0) AP1, DP1, RP1 (Node 1) AP2, DP2, RP2 (Node 2) Output: Single 128 × 128 × 3 RGB radar image Δx = [0,−32,32]; Δy = [32,−16,−32] For each node i ∈ {0,1,2}: 1. Resize APᵢ, DPᵢ, RPᵢ to 128 × 128 using zero-padding 2. Apply fixed shifts to APᵢ to avoid overlap: APshifted = shift(APᵢ, Δx[0], Δy[0]) // empirically Δx, Δy determined 3. Rotate DPᵢ and RPᵢ by predefined angles: DProt = rotate(DPᵢ, 45) DProt_shifted = shift(DProt, Δx[1], Δy[1]) RProt = rotate(RPᵢ,135) RProt_shifted = shift(RProt, Δx[2], Δy[2]) 4. Combine node-wise grayscale image: Grayi = APshifted + DProt_shifted + RProt_shifted 5. Assign to RGB channels (fixed mapping): if i == 0 → R = Gray_0 if i == 1 → G = Gray_1 if i == 2 → B = Gray_2 I_RGB ← Concatenate(R, G, B; axis = 2) |

2.2. Ensemble Learning Paradigm for RGB Image Classification

3. Experimental Works

3.1. Dataset

3.2. Experimental Setup

3.3. Results

3.3.1. Performance Comparison of the Proposed RGB Radar Images with the Standard Radar Images

3.3.2. The Performance Evaluation of Pretrained CNN Models Using RGB Radar Images

3.3.3. Classification Results of Ensemble Learning Models

3.3.4. Ablation Study: Contribution of Each Image Type

4. Discussion

- The RGB image transformation technique used in the proposed model minimizes data loss by merging nine different radar images into a single image. This preserves various features while reducing the processed data volume.

- By consolidating grayscale radar images from multiple nodes into a single-color radar image, we effectively retain diverse radar image features while simplifying subsequent processes. The ensemble learning approach further enhances classification accuracy by leveraging the strengths of multiple pre-trained CNN models.

- An ensemble learning-based approach was employed by combining VGG19 and ResNet50 deep learning models, producing robust and high scores. Additionally, the community learning approach is more cost-efficient compared to other approaches in the literature.

- The RGB fusion process currently uses empirically determined fixed shifts and rotations, making it semi-manual and potentially requiring recalibration if radar node placement or movement protocols change.

- Although the results are promising, strengthening the data calibration used is needed for real-time applications. Furthermore, the model is designed to be adaptable to different radar hardware configurations or new detection features.

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, X.; He, Y.; Jing, X. A Survey of Deep Learning-Based Human Activity Recognition in Radar. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Q.; Li, Y.; Li, C.; Pal, R. Gesture Recognition for Smart Home Applications Using Portable Radar Sensors. In Proceedings of the 2014 36th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, Chicago, IL, USA, 26–30 August 2014; Volume 2014, pp. 6414–6417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulling, A.; Blanke, U.; Schiele, B. A Tutorial on Human Activity Recognition Using Body-Worn Inertial Sensors. ACM Comput. Surv. 2014, 46, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.R.; Kumar, K.A.; Cho, S.H. Novel Time-Distance Parameters Based Hand Gesture Recognition System Using Multi-UWB Radars. IEEE Sens. Lett. 2023, 7, 6002204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.G.; Zhang, Y.D.; Ahmad, F.; Ho, K.C.D. Radar Signal Processing for Elderly Fall Detection: The Future for in-Home Monitoring. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2016, 33, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santra, A.; Ulaganathan, R.V.; Finke, T. Short-Range Millimetric-Wave Radar System for Occupancy Sensing Application. IEEE Sens. Lett. 2018, 2, 7000704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Fioranelli, F.; Yang, S.; Zhang, L.; Romain, O.; He, Q.; Cui, G.; Le Kernec, J. Multi-Domains Based Human Activity Classification in Radar. In Proceedings of the IET Conference Proceedings, Online Conference, 4–6 November 2020; Volume 2020, pp. 1744–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Petropulu, A.P.; Poor, H.V. MIMO Radar for Advanced Driver-Assistance Systems and Autonomous Driving: Advantages and Challenges. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2020, 37, 98–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Kallu, K.D.; Ahmed, S.; Cho, S.H. Hand Gestures Recognition Using Radar Sensors for Human-Computer-Interaction: A Review. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhao, X.; Li, Z. DCS-CTN: Subtle Gesture Recognition Based on TD-CNN-Transformer via Millimeter-Wave Radar. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 17680–17693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, B.; Ma, X.; Zhang, Z.; Lian, Z.; Wang, B. Interference-Robust Millimeter-Wave Radar-Based Dynamic Hand Gesture Recognition Using 2D CNN-Transformer Networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 11, 2741–2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liu, Z. A Multimodal Dynamic Hand Gesture Recognition Based on Radar–Vision Fusion. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 8001715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Zhao, L.; Liu, C.; Ling, M. A Low-Complexity Hand Gesture Recognition Framework via Dual MmWave FMCW Radar System. Sensors 2023, 23, 8551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, N.; Grebner, T.; Waldschmidt, C. PointNet + LSTM for Target List-Based Gesture Recognition with Incoherent Radar Networks. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2022, 58, 5675–5686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Guendel, R.G.; Yarovoy, A.; Fioranelli, F. Point Transformer-Based Human Activity Recognition Using High-Dimensional Radar Point Clouds. In Proceedings of the IEEE Radar Conference, San Antonio, TX, USA, 1–5 May 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Li, C. Automated Violin Bowing Gesture Recognition Using FMCW-Radar and Machine Learning. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 9262–9270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fırat, H.; Üzen, H.; Atila, O.; Şengür, A. Automated Efficient Traffic Gesture Recognition Using Swin Transformer-Based Multi-Input Deep Network with Radar Images. Signal Image Video Process. 2025, 19, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Leu, M.C.; Yin, Z. Real-Time Multi-Modal Human–Robot Collaboration Using Gestures and Speech. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 2022, 144, 101007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; IEEE Computer Society: Los Alamitos, CA, USA, 2016; Volume 2016, pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, L.; Zhang, X.; Yang, T.; Wang, B.; Li, J. The Application of ResNet-34 Model Integrating Transfer Learning in the Recognition and Classification of Overseas Chinese Frescoes. Electronics 2023, 12, 3677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, S.; Kim, Y.J.; Vo, D.M.; Lee, S.W. Colorectal Disease Classification Using Efficiently Scaled Dilation in Convolutional Neural Network. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 99227–99238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Üzen, H.; Altın, M.; Balıkçı Çiçek, İ. Bal Arı Hastalıklarının Sınıflandırılması Için ConvMixer, VGG16 ve ResNet101 Tabanlı Topluluk Öğrenme Yaklaşımı. Fırat Üniversitesi Mühendislik Bilim. Derg. 2024, 36, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2015—Conference Track Proceedings, San Diego, CA, USA, 7–9 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; Van Der Maaten, L.; Weinberger, K.Q. Densely Connected Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the 30th IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; Volume 2017, pp. 2261–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szegedy, C.; Vanhoucke, V.; Ioffe, S.; Shlens, J.; Wojna, Z. Rethinking the Inception Architecture for Computer Vision. In Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; Volume 2016, pp. 2818–2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Üzen, H.; Türkoğlu, M.; Ari, A.; Hanbay, D. InceptionV3 Based Enriched Feature Integration Network Architecture for Pixel-Level Surface Defect Detection. Gazi Üniversitesi Mühendislik-Mimar. Fakültesi Derg. 2022, 2, 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandler, M.; Howard, A.; Zhu, M.; Zhmoginov, A.; Chen, L.C. MobileNetV2: Inverted Residuals and Linear Bottlenecks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 4510–4520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firat, H.; Üzen, H. Detection of Pneumonia Using A Hybrid Approach Consisting of MobileNetV2 and Squeeze- and-Excitation Network. Turk. J. Nat. Sci. 2024, 13, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traffic Gesture Dataset. Available online: https://www.uni-ulm.de/in/mwt/forschung/online-datenbank/traffic-gesture-dataset/ (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Guo, T.; Lu, B.; Wang, F.; Lu, Z. Depth-aware super-resolution via distance-adaptive variational formulation. J. Electron. Imaging 2025, 34, 053018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Yang, J.; Chen, L.; Li, F.; Feng, Z.; Jia, L.; Li, P. RailVoxelDet: An Lightweight 3D Object Detection Method for Railway Transportation Driven by on-Board LiDAR Data. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 37175–37189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | RGB | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ResNet18 | 87.83 | 47.79 | 85.05 | 75.56 | 44.67 | 82.88 | 76.26 | 46.84 | 83.98 | 76.86 |

| Resnet34 | 88.74 | 49.68 | 86.63 | 77.30 | 47.82 | 84.33 | 76.60 | 47.47 | 85.02 | 73.23 |

| Resnet50 | 90.88 | 48.36 | 86.19 | 74.36 | 46.87 | 83.63 | 76.89 | 49.84 | 85.43 | 74.62 |

| Resnet101 | 88.43 | 48.64 | 85.90 | 76.13 | 47.13 | 83.66 | 75.03 | 50.12 | 84.70 | 82.09 |

| Vgg16 | 91.04 | 53.62 | 87.35 | 81.80 | 50.91 | 86.79 | 80.07 | 52.96 | 85.93 | 83.13 |

| Vgg19 | 89.97 | 54.19 | 87.16 | 81.80 | 50.69 | 85.68 | 80.42 | 53.15 | 85.84 | 79.57 |

| Densenet121 | 89.12 | 50.66 | 86.94 | 80.26 | 49.36 | 85.84 | 76.04 | 47.95 | 85.24 | 76.51 |

| Densenet169 | 89.4 | 52.23 | 86.79 | 79.25 | 48.58 | 85.68 | 79.41 | 49.93 | 85.62 | 77.45 |

| InceptionV3 | 90.32 | 50.34 | 86.50 | 78.84 | 47.32 | 85.30 | 76.63 | 54.82 | 84.77 | 70.80 |

| MobileNet | 88.43 | 38.11 | 82.62 | 72.22 | 34.58 | 79.16 | 67.90 | 35.05 | 82.40 | 76.86 |

| Model Name | Accuracy (%) | F1 Score (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ResNet18 | 89.77 | 89.58 | 89.91 | 89.67 |

| ResNet34 | 90.14 | 89.96 | 90.33 | 90.03 |

| ResNet50 | 90.45 | 90.29 | 90.67 | 90.36 |

| ResNet 101 | 90.40 | 90.19 | 90.70 | 90.28 |

| VGG16 | 91.25 | 91.13 | 91.47 | 91.21 |

| VGG19 | 91.35 | 91.20 | 91.56 | 91.29 |

| DenseNet121 | 90.48 | 90.29 | 90.63 | 90.40 |

| DenseNet169 | 90.67 | 90.53 | 90.90 | 90.61 |

| InceptionV3 | 90.81 | 90.66 | 90.97 | 90.72 |

| MobileNet | 88.54 | 88.38 | 88.85 | 88.46 |

| Model | Metric | ResNet34 | ResNet50 | ResNet101 | VGG16 | VGG19 | DenseNet121 | DenseNet169 | InceptionV3 | MobileNet |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ResNet18 | Accuracy | 91.02 | 91.34 | 91.30 | 91.79 | 92.05 | 91.39 | 91.46 | 91.54 | 90.82 |

| F1 score | 90.84 | 91.18 | 91.11 | 91.66 | 91.91 | 91.22 | 91.34 | 91.41 | 90.65 | |

| Precision | 91.17 | 91.50 | 91.50 | 91.94 | 92.19 | 91.52 | 91.66 | 91.70 | 90.99 | |

| Recall | 90.91 | 91.26 | 91.20 | 91.73 | 91.99 | 91.30 | 91.41 | 91.47 | 90.74 | |

| ReSNet34 | Accuracy | 91.45 | 91.32 | 91.95 | 92.09 | 91.44 | 91.32 | 91.61 | 91.06 | |

| F1 score | 91.31 | 91.14 | 91.82 | 91.96 | 91.27 | 91.18 | 91.47 | 90.90 | ||

| Precision | 91.64 | 91.55 | 92.17 | 92.26 | 91.57 | 91.56 | 91.78 | 91.28 | ||

| Recall | 91.37 | 91.21 | 91.88 | 92.03 | 91.34 | 91.25 | 91.53 | 90.98 | ||

| ReSNet50 | Accuracy | 91.41 | 92.39 | 92.55 | 91.70 | 91.57 | 91.96 | 91.50 | ||

| F1 score | 91.25 | 92.27 | 92.44 | 91.56 | 91.44 | 91.84 | 91.36 | |||

| Precision | 91.62 | 92.55 | 92.73 | 91.89 | 91.79 | 92.14 | 91.70 | |||

| Recall | 91.33 | 92.32 | 92.50 | 91.62 | 91.50 | 91.88 | 91.42 | |||

| ReSNnet101 | Accuracy | 91.90 | 92.04 | 91.59 | 91.68 | 91.82 | 91.32 | |||

| F1 score | 91.74 | 91.88 | 91.40 | 91.52 | 91.67 | 91.12 | ||||

| Precision | 92.10 | 92.20 | 91.73 | 91.89 | 92.00 | 91.53 | ||||

| Recall | 91.81 | 91.98 | 91.50 | 91.60 | 91.74 | 91.21 | ||||

| Vgg16 | Accuracy | 91.97 | 91.97 | 92.03 | 92.45 | 92.02 | ||||

| F1 score | 91.84 | 91.83 | 91.90 | 92.35 | 91.93 | |||||

| Precision | 92.16 | 92.13 | 92.25 | 92.61 | 92.22 | |||||

| Recall | 91.92 | 91.92 | 91.97 | 92.39 | 91.98 | |||||

| Vgg19 | Accuracy | 92.19 | 92.16 | 92.30 | 92.05 | |||||

| F1 score | 92.05 | 92.03 | 92.17 | 91.91 | ||||||

| Precision | 92.33 | 92.36 | 92.46 | 92.21 | ||||||

| Recall | 92.12 | 92.10 | 92.23 | 91.97 | ||||||

| Densenet121 | Accuracy | 91.42 | 91.84 | 91.17 | ||||||

| F1 score | 91.26 | 91.70 | 91.02 | |||||||

| Precision | 91.60 | 91.97 | 91.31 | |||||||

| Recall | 91.34 | 91.76 | 91.11 | |||||||

| Densenet169 | Accuracy | 91.93 | 91.07 | |||||||

| F1 score | 91.81 | 90.92 | ||||||||

| Precision | 92.11 | 91.25 | ||||||||

| Recall | 91.87 | 91.00 | ||||||||

| InceptionV3 | Accuracy | 91.44 | ||||||||

| F1 score | 91.31 | |||||||||

| Precision | 91.64 | |||||||||

| Recall | 91.36 |

| Image Used | Accuracy (%) | Drop Rate According to RGB |

|---|---|---|

| Full RGB–AP, DP, and RP | 91.04 | – |

| DP and RP only (all APs removed) | 89.02 | −2.02 |

| AP and RP only (all DPs removed) | 82.05 | −6.99 |

| AP and DP only (all RPs removed) | 87.90 | −3.14 |

| Reference | Features | Classifier | Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kern et al. [14] (2022) | DS, RS | CNN | 88.8 |

| Kern et al. [14] (2022) | DS, RS, and AS | CNN | 89.7 |

| Kern et al. [14] (2022) | PointNet features with R, v, SNR, and in | LSTM | 90.0 |

| Kern et al. [14] (2022) | PointNet features with R, v, SNR, and in without spatial filtering | LSTM | 87.0 |

| Kern et al. [14] (2022) | PointNet features with R, v, θ, SNR, and in | LSTM | 89.5 |

| Kern et al. [14] (2022) | PointNet features with x, y, SNR, and in | LSTM | 80.7 |

| Kern et al. [14] (2022) | PointNet features with R, v, θ, xnorm, ynorm, SNR, and in | LSTM | 92.2 |

| Fırat et al. [17] (2025) | DenseNet121 and Swin transformer | Transformer | 90.54 |

| Proposed | RGB image based on DS, RS, and AS | Ensemble learning based on ResNet50 and VGG19 | 92.55 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Üzen, H. RGB Fusion of Multiple Radar Sensors for Deep Learning-Based Traffic Hand Gesture Recognition. Electronics 2026, 15, 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010140

Üzen H. RGB Fusion of Multiple Radar Sensors for Deep Learning-Based Traffic Hand Gesture Recognition. Electronics. 2026; 15(1):140. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010140

Chicago/Turabian StyleÜzen, Hüseyin. 2026. "RGB Fusion of Multiple Radar Sensors for Deep Learning-Based Traffic Hand Gesture Recognition" Electronics 15, no. 1: 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010140

APA StyleÜzen, H. (2026). RGB Fusion of Multiple Radar Sensors for Deep Learning-Based Traffic Hand Gesture Recognition. Electronics, 15(1), 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010140