1. Introduction

The South Korean government has established the “Digital Twin Activation Strategy” to carry out super-innovative projects of digital twins to transform Korea along with the “Digital New Deal 2.0” [

1].

A digital twin is a virtual representation of a physical system. It has a role of reflecting the dynamics of that physical system. Kim [

2] has introduced the concept of federated digital twins to deal with complex systems, which are related to each other. A federated digital twin is the collection of individual digital twins. Each digital twin, representing a system, comprises the federated digital twins.

The 15 super-innovative projects of digital twins to transform Korea, along with the “Digital New Deal 2.0”, include medical and healthcare, wellness, smart city, transportation and mobility, agriculture and livestock farming, environment, smart manufacturing, maritime and port harbor, construction and civil engineering, distribution and logistics, energy, military applications, disaster recovery and resilience, social disaster prevention, and residential safety [

1]. Among these, healthcare is revolutionized through innovative technologies such as digital twins and artificial intelligence (AI). These new technologies impact patient treatment and management and healthcare services. Mobile following robots are becoming increasingly necessary in modern healthcare systems for alleviating the workload of medical staff, preventing infections, caring for older adults in an aging society, and demonstrating high adaptability to infrequent situations.

Research on surgical robots has advanced significantly, reaching the commercialization stage. Robotic surgery shortens patient recovery times and enhances surgical precision, making it highly valuable in hospitals, with the technology continuing to evolve. However, tasks like handling linens, medications, meals, and specimens are still performed manually, and the application of transport robots remains insufficient. Some studies have explored autonomous robots performing relatively simple tasks like moving cargo or transporting medications. However, robots capable of transporting hospital beds with patients lying on them have yet to appear. Robotic systems for transporting patient beds to wards after surgery or moving emergency room patients are still under research.

Transporting a patient’s bed presents multiple challenges that must be overcome. The most fundamental, common to all autonomous robots, is obstacle avoidance technology for sudden obstacles. Beyond this, safety concerns are paramount for autonomous bed transport robots in hospitals. Such systems must enable real-time monitoring of the patient’s condition and eliminate the risk of collisions or falls. Furthermore, it is necessary to prevent shocks to the patient. To effectively develop transport robots while solving all these complex problems, digital twin technology is required. Using digital twins, strategies can be devised to predict and resolve hazardous situations across multiple virtual environments. In large-scale hospital environments where dozens of robots perform different tasks, a single digital twin has limitations. Therefore, the concept of federated digital twins must be introduced to enable their harmonious operation.

In this context, federated digital twins are a core technology that goes beyond simply remotely controlling robots, enabling all transport robots within a hospital to move as a single, coordinated, intelligent system. Bed robots are needed to minimize infection among medical staff and safely transport patients in infectious disease situations such as COVID-19. Digital twins are necessary to successfully introduce and efficiently operate these robots. In this study, we will design scenarios considering various situations in actual hospitals, implement them as digital twins, and operate them according to each scenario to predict the results. The South Korean government classifies the core component technologies of digital twins into the following five categories: (1) virtualization, (2) synchronization, (3) modeling and simulation, (4) federation, and (5) intelligent services [

1]. In this work, we develop a federated digital twin for a nurse-following medical bed robot with a negative pressure chamber for patient transportation in the hospital. We manifest how core component technologies of digital twins are employed in the development of the previously mentioned medical bed robot. Consequently, command and control of the suggested medical bed robot require two digital twins—one for the patient being carried and the other for the medical bed robot—resulting in a federated digital twin system.

We developed a negative pressure bed robot and implemented elements for creating a digital twin based on the developed negative pressure bed and the actual hospital layout. Specifically, we developed pathfinding, person recognition, vital sign processing algorithms, and modules that transmit data from the control server to the negative pressure bed. The scope of this research was to verify through simulation that these components functioned correctly before developing the actual digital twin.

The remainder of this paper is as follows:

Section 2 summarizes related works, focusing on Industry 4.0, digital twins, and narrowing down to digital twins in the healthcare industry and nurse-following robots.

Section 3 shows the overview of the federated digital twins for a nurse-following medical bed robot with a negative pressure chamber for patient transportation in the hospital by introducing each category of core component technologies of digital twins implemented in the system.

Section 4 aims to present the process modeling and simulation as a basis of a digital twin.

Section 5 contains conclusions and future areas of development.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Symbiotic Relationship Between Industry 4.0, Cyber-Physical Systems, and Digital Twins

Industry 4.0 refers to the Fourth Industrial Revolution. It made paradigm shift in industrial production methods based on digital technology [

3]. The term was first introduced at the 2011 Hannover Messe industrial fair in Germany and later proposed as a national strategy by a high-level research group led by Henning Kagermann in 2013, laying the groundwork for Industry 4.0. Industry 4.0 revolutionized the industry production system through the integration of information and communication technology (ICT) into manufacturing.

Industry 4.0 has a core of cyber-physical systems integrating physical components with digital technology. This cyber-physical system enables real-time data collection, exchange, analysis, and AI-based decision-making across factories and supply chains, thereby characterizing the connectivity and intelligence in Industry 4.0 [

3]. While the Third Industrial Revolution focused on automation technology, the Fourth Industrial Revolution centers on connectivity and intelligence. The core of Industry 4.0 lies in the integration of physical production facilities and digital networks through cyber-physical systems (CPSs), enabling real-time data exchange, analysis, and autonomous decision-making. In CPS, physical equipment such as machines, sensors, actuators, and products related to software. This requires IoT, AI, cloud, and sensor technologies. CPS goes beyond simple automation by enabling individual products to be equipped with smart objects. This transforms the manufacturing environment into a fully connected and intelligent system, driving innovation in the manufacturing industry. Embedded systems are applied to individual machines, sensors, and product units, enabling them to interact with each other in real time.

The Industry 4.0 core technology encompasses the following [

3]:

IIoT is a system that collects and exchanges real-time data by embedding electronic circuits and software in physical equipment such as sensors, devices, and machines. This communication between devices (M2M) vertically integrates everything from production site devices to control systems, forming the core infrastructure for process control and quality management [

4].

To process the large amounts of data collected on production sites, cloud enables big data analysis, predictive maintenance, and enterprise resource planning (ERP) integration, while edge computing performs real-time processing near devices to reduce latency. Siemens’ MindSphere is a representative industrial cloud platform that collects equipment data from around the world and provides predictive maintenance services [

5,

6].

Industry 4.0 systems collect data from various sensors and utilize it for fault prediction, quality improvement, and production schedule optimization through machine learning- and deep learning-based analysis. Industrial AI is artificial intelligence specialized for manufacturing, which enables the realization of cognitive manufacturing in conjunction with CPS [

7,

8].

CPPS is a structure where multiple CPSs interact to control production processes. Digital twins are virtual replicas of physical systems that perform real-time simulation, predictive analysis, and optimization based on sensor data [

9]. The digital twin concept represents the prerequisite for the development of a CPPS [

10].

Industry 4.0 utilizes robots and autonomous mobile robots, which can collaborate with humans or perform tasks independently through sensors and AI [

11,

12]. People could implement smart factory by applying Industry 4.0 strategies to actual manufacturing environments. Smart factories are CPS-based structures in which intelligence is embedded in all production stages, from individual devices to enterprise-wide planning systems. Multiple CPSs jointly manage production processes in real world manufacturing.

Digital twins are virtual replicas of CPS that can simulate and optimize systems based on real-time data. These are used in virtual commissioning, real-time monitoring, and augmented reality-based worker training using collected data from CPS [

13,

14]. The prediction and analysis results from digital twin are fed back to CPS again. The “3D digital twin” highlights its analytical abilities, thus helping more intuitive understanding of the system and fast decision-making. This term implies that the technology can offer a 3D representation that can be utilized for various analyses and to draw valuable information from the data [

15]. While digital twin focuses on machines and manufacturing, human digital twin is a technological concept that replicates the physiological and psychological states, behavioral characteristics, and environmental factors of humans in a virtual space [

16]. Human digital twins integrate data collected over time, such as biological signals, activity levels, psychological states, and environmental changes, enabling real-time monitoring, status prediction, and customized services [

17]. Lauer-Schmaltz et al. developed the human digital twin for patient-tailored rehabilitation. They combined rehabilitation robots and HDT to adjust training in real time according to patient fatigue levels and movement patterns [

18]. Rovati et al. proposed the digital twin for critical care monitoring. Their system performs modeling biosignals of ICU (intensive care unit) patients [

19]. Koopsen et al. used the digital twin for disease prognosis prediction by optimizing treatment strategies [

20].

2.2. Evolution and Application of Digital Twins in Healthcare

Dürr et al. [

21] pointed out the lack of research on digital twins in the healthcare field but emphasized their necessity in healthcare, as they enable the simulation and experience of various situations. Cook and Chen particularly emphasized the digital twin’s necessity in nurse education [

22,

23]. In nursing environments, mixed reality technology can be used to create three-dimensional scenarios similar to real-life situations. This enables self-directed learning without spatial or temporal constraints, allowing users to observe learned skills from multiple angles or repeat practice, thereby supporting personalized training tailored to individual learning speeds [

22].

Despite its potential, the application of the digital twin technology in healthcare, particularly in nursing, remains nascent and fragmented. Dürr et al. [

21] pointed out that digital twins in the nursing field are still in an immature stage, with most studies focusing on virtualization for a single user. They also noted that the current level of technology is limited to visually replicating hospital rooms or parts of a patient’s body on a two-dimensional virtual environment displayed on a computer monitor. A systematic review by Xames et al. [

24] concluded that the majority of current research is conceptual, with a significant number of studies mislabeling their work as digital twins without incorporating the necessary modeling and bidirectional data-flow components.

There have been attempts to connect the virtual and the real worlds. Carlson and Gagnon [

25] placed patient manikins in actual hospital rooms and combined them with augmented reality content to connect virtual clinical scenarios with the real world. Dürr et al. [

21] emphasized the need to establish interaction design principles to enhance educational effectiveness. When classifying digital twin research in the healthcare field from an HCI perspective, it can be evaluated that most studies only partially fulfill elements in four aspects: individual interaction, social interaction and communication, workflow, and physical environment [

26].

For more efficient digital twin implementation, interaction aspects are emphasized, particularly providing natural interaction that allows robots to move their bodies or handle real objects. Araujo et al. [

27] introduced a technique that gives physical substance to virtual objects, allowing users to lift and move virtual patients as if they were real objects. Through such physical implementation, learners can interact with tools and patients in the same way as in reality, even in a virtual environment, which is expected to significantly improve immersion and learning efficiency. Furthermore, it is necessary to actively utilize the context of actual clinical environments when designing MR systems. For example, as in the study by Carlson et al [

25]., introducing real physical environments such as hospital beds and patient manikins into educational scenarios can help transfer knowledge learned in school to clinical settings. Lauer-Schmaltz [

18] presented the design and implementation of a human digital twin (HDT) system for upper limb stroke rehabilitation utilizing an exoskeleton robot and functional games. The proposed system enhances collaboration between medical and non-medical personnel through real-time adjustment of treatment difficulty and exoskeleton assistance based on patient status, data visualization, and decision support mechanisms. It also improves patient engagement through personalized feedback. Koopsen et al. [

20] created imaging-based digital twins for heart failure patients who were treated with cardiac resynchronization therapy. They found that virtual pacing intervention in the digital twin could be used to predict the degree of left ventricular dysfunction.

Based on the literature review, we found that the research on digital twin lacks. Previous studies have emphasized the importance of digital twins in healthcare, particularly in the medical field, but most of these studies have been limited to applying AR/VR to isolated tasks. There have been no attempts to extensively connect the physical space of a hospital with cyberspace, and, in particular, there have been no studies combining digital twins with technology for safely transporting patients in an infectious disease environment.

2.3. Autonomous Mobile Robots Technology

To develop a nurse-following robot, we first investigated line following capabilities and then explored sensing technologies and object recognition algorithms used in autonomous robots as a second step. Pazil et al. [

28] presented the development of an autonomous assistive robot that utilizes an IR sensor and an ultrasonic sensor to deliver medication to patients. The robot is powered by a microcontroller and features an IR sensor that autonomously detects and follows the lines drawn on the floor. The ultrasonic sensor is used to detect obstacles on the robot’s path and stop the robot accordingly. Once the robot has completed the drug delivery, it will send a confirmation message to the medical team to let them know the task is complete. Rahim et al. [

29] proposed the design of a line-following and obstacle-evading robot that can serve as a nursing assistant. The robot detects lines by measuring the infrared radiation reflected from the floor’s surface. At the same time, it uses the information from the ultrasonic sensor to calculate the distance to the obstacle ahead. If the distance to the obstacle is close to the set threshold, the obstacle avoidance module is automatically triggered, allowing the robot to steer clear of the obstacle and then resume its path. Gandhar et al. [

30] proposed a line-following robot equipped with a speech recognition system to safeguard patients and nurses from infectious diseases and create a contact-free environment. The robot employs a total of three IR proximity sensor modules, two of which are for line following and one for obstacle detection. The core function involves adding a speech recognition module, which allows the robot to detect when the patient says “done” and then stop the task and return to the nurse’s station. Ali et al. [

31] developed a multi-functional medical assistant robot by integrating RFID and line-tracking technologies. Using an IR sensor, the device tracks obstacles along the line, while simultaneously monitoring the patient’s vital signs, including body temperature, blood pressure, heart rate, and oxygen saturation, through the onboard sensors. If the measured value exceeds the set threshold, it sends a warning message to the doctor, prompting them to take immediate action.

We reviewed the papers regarding autonomous driving, path planning, and mapping. This research focuses on developing core algorithms that enable robots to autonomously navigate complex and dynamic environments, such as hospitals, by self-localizing (SLAM), avoiding obstacles, and finding the most efficient routes.

Narayanan et al. [

32] designed a smart hospital robot and developed a fuzzy controller system to enable it to navigate around obstacles. The system uses image inputs processed by three ultrasonic sensors and a camera to detect obstacles. Three methods have been proposed for robot path planning: SLAM, which determines the robot’s location; and potential-based approaches, which navigate the robot to the target point while avoiding obstacles. Ultimately, probabilistic models take into account the uncertainty of the environment to calculate the path. The robot also uses wireless Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) beacons to identify the patient’s room and deliver medication. Salinas-Avila et al. [

33] developed an assistive delivery robot that delivers medication to patients in a nursing home, following a schedule set by caregivers through a graphical user interface (GUI). The robot uses its 360° distance sensor to detect its surroundings and provide information on distance and direction. Using SLAM as a core technology, the robot can both localize itself and map its surroundings simultaneously. They also used the ThingSpeak IoT platform to collect the patient’s biometric data, which can be viewed by family members on a web page.

Najim et al. [

34] proposed a mobile robot that can move in any direction using Mecanum wheels. Using input from a depth camera and LiDAR sensor, the robot employs SLAM algorithms to map its surroundings and determine its own location. With this technology, robots can navigate hospital corridors, sidestep both static and dynamic obstacles, and deliver medications safely and efficiently. The robot was tested in previously unexplored hospital corridors, and when obstacles were detected, it slowed down and avoided them by reducing motor power. Kim et al. [

35] (2023) proposed an autonomous patient transport robot that can safely move between locations without external interference. The autonomous driving system is composed of a path planning module and a motion control module. The path planning module combines the A* algorithm for global path planning with the AHP-based algorithm for local path planning to determine the optimal path. The motion control module also employs a linear quadratic regulator (LQR) controller with a Kalman filter to minimize the robot’s oscillations. However, it is worth noting that this system does not have environmental sensors for autonomous driving, so it is not considered fully autonomous. Cheng et al. [

36] explored the scheduling strategy of autonomous mobile robots (AMRs) in the uncertain environment of smart hospitals. To minimize the total cost by taking into account the robot’s service time and travel time, they developed a stochastic programming model. To implement this scheduling strategy, they also proposed a variable neighborhood search (VNS) optimization technique. This study demonstrates that by properly organizing robot charging and service requests, hospitals can achieve substantial cost savings.

2.4. Nurse-Following Robots: A Critical Review of Technological Progression

Initial methods for detecting humans relied on ultrasonic and infrared sensors, but these proved unstable for continuously recognizing specific targets. Subsequently, the widely adopted approach utilized the Kinect sensor, which provided low-cost RGB-D capabilities [

37]. By estimating human skeletons, this enabled robots to distinguish specific individuals from other objects and track their position and distance. The most advanced technology, laser scanner (LiDAR), is used for precise distance measurement and is commonly employed for leg tracking to follow people [

38]. To overcome LiDAR’s difficulty in estimating depth at long distances, recent approaches fuse LiDAR with cameras [

39].

Nurse-following robots require position recognition and navigation within a dynamic environment where the user moves. They must build a map of the surrounding environment and determine their own position within it; this function is performed by Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM). It is utilized in combination with various sensing methods: the vSLAM method is used with low-cost cameras, while other approaches combine it with RGB-D or LiDAR. They are also used in combination with wearable sensors [

40].

From an algorithmic perspective, classical computer vision methods were initially used, but the trend is now shifting towards deep learning. Classical methods detect people based on color contrast, but this approach is highly susceptible to environmental factors like lighting [

37]. Deep learning technology is also increasingly used recently, with techniques being developed to detect and track multiple people. Deep learning goes beyond recognizing people to also identifying who they are and is evolving into technology that predicts human movement [

41]. For example, it can predict that the nurse currently nearby is A and that A will move in this direction. Jiang et al. [

42] proposed a novel classification-lock strategy for target localization. Their method employs positive and negative classifiers to verify the tracker’s results and update the tracking model. An example of developing a follow-up robot for hospital use is as follows: Ilias et al. [

37] constructed a mobile robot for nurses capable of following and carrying medical equipment. They employed ultrasonic sensors for target tracking. Their proposed model has the drawback of being dedicated to a specific person. Thape et al. [

43] designed a nursing robot platform to assist with patient sitter tasks and patient walker tasks. To address the inconvenience of patients having to manually pull heavy IV stands during movement, a patient-following robot was developed. The primary sensor, an RGB camera, is mounted low near the floor. It uses artificial markers to establish reference points, locates the patient through template matching, and targets the subject by comparing color histograms. After detecting the patient, the robot estimates distance using a pinhole camera model and plans its movement trajectory to maintain stable motion.

Previous research included nurse-following robots, but none combined them with negative pressure bed robots. Furthermore, no studies extended to digital twins. Hospital corridors are dynamic spaces constantly bustling with medical staff, patients, visitors, and various mobile equipment. Robots must possess advanced navigation capabilities to detect and safely avoid multiple obstacles exhibiting unpredictable movements in real time [

44]. Thus, the digital twin is required before nurse-following robot adoption, and running the simulation under various scenarios is required. Building a digital twin in the healthcare industry was a research topic, but the federated digital twin concept has never been studied. This research addresses the negative pressure bed robot—a previously unexplored form of nurse-following robot—discusses the elements necessary for its digital twin implementation, and presents a case study of designing simulations to realize the digital twin.

3. Nurse-Following Medical Bed Robots and IoT System

The robot platform that forms the foundation of this system was designed based on an Automated Guided Vehicle (AGV) module. AGVs are widely used in hospitals to transport items such as food, linens, and medications, thereby reducing the workload on the staff [

45]. Siemens developed a new AGV capable of autonomous operation without additional infrastructure by removing the self-navigation functionality to address the high initial costs for its hospital AGV solution. Bleichert Automation GmbH & Co. KG at Osterburken in Germany developed this solution. To meet the strict hygiene standards of hospital environments, the AGV is equipped with Siemens’ SIRIUS ACT (Corporate Headquarters Siemens Aktiengesellschaft Werner-von-Siemens-Straße 1 80333 Munich Germany) push buttons and indicator lights. The entire design is highly compact to operate smoothly even in narrow hospital corridors. Despite its small size of 600 mm width, it can carry up to 500 kg of goods and directly transport items like food, laundry, and sterilized goods containers without additional transport devices [

46]. Maheboob and Landge [

47] developed a linen delivery robot. STEERON AGV has a size of 130 × 68 × 36 cm

3, a maximum speed of 4 m/s, a load capacity of up to 900 kg, and is capable of driving up slopes of up to 7% when loaded to maximum capacity. They used lithium iron phosphate battery to ensure thermal safety, a 360-degree scanning sensor to map the surrounding terrain and safely navigate routes, additional safety sensors equipped with sensors detecting above and below the AGV to protect operations, and signaling devices that alert nearby people to the AGV’s presence and movement via audio and visual signals. They added the function to manually control the AGV via tablet or smartphone without a separate screen. All navigation and route setting communications occur via WIFI. The network is designed to be operated as part of an integrated network connected via WIFI to the hospital’s central server, hospital information system (HIS), elevators, automatic doors, etc.

Previous works indicate that by using various sensors such as LiDAR and 3D cameras, along with SLAM (Simultaneous Localization and Mapping) technology, AGVs can autonomously navigate complex and dynamic hospital environments (narrow corridors, elevators, etc.) and avoid obstacles without requiring prior infrastructure setup. While introducing AGVs may involve high initial costs and potentially limited effectiveness, combining them with various sensor technologies and artificial intelligence can maximize their benefits. They mentioned that AGVs must integrate with automatic doors, elevators, access control systems, fire alarm systems, etc., to move smoothly within the hospital. However, robots designed to directly transport patient beds remain in the early research stages, as they require higher safety standards and the ability to handle patients dedicatedly. We are developing a process for manufacturing follow-up robots and cleanroom equipment. First, we designed and manufactured an automated guided vehicle fixed module connected to a negative pressure bed, with a total weight of 13.2 kg for four sets. Next, we built a prototype multi-adapter compatible with hospitals. For the adapter fixation method, we reviewed options such as a snap lock, knob rotation, and webbing belt, and finally selected a combination of a spring-loaded fixation block and a ball catcher with a webbing belt. For a lightweight design, we used aluminum profiles and angle tubes.

The manufactured components passed electromagnetic compatibility tests and wireless device electromagnetic compatibility tests. Additionally, compatibility tests were conducted with the adapter and negative pressure bed combined while driving on an incline, with no issues identified. In user evaluations, the ease of assembly and locking strength were tested, and improvement needs were identified, including some structural issues, center of gravity imbalance, and assembly time requirements. Proposed improvements include adjusting the center of gravity and wheel position, installing auxiliary wheels, and applying a faster assembly method.

Finally, to prepare for Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) certification, we have entered into a consulting contract with a specialized company and are preparing the necessary documents for the certification application, including manufacturing processes, technical documents, manufacturing facility overview, floor plans, organizational charts, and lists of suppliers and testing equipment. We aim to complete GMP certification by next year and are also reviewing the possibility of obtaining integrated product certification.

Figure 1 illustrates some examples of nurse-following medical bed robot with a negative pressure chamber.

Hanafi et al. showed that utilizing AI wearable devices can enable real-time public health surveillance. This technology has demonstrated the ability to detect disease outbreaks such as influenza or COVID-19 two to six days earlier than conventional methods [

48]. To monitor patient condition, we developed modification and production of wireless wearable biosignal measurement devices. The devices’ size was reduced through circuit optimization of wearable biosignal measurement modules. We added gyro sensors for fall monitoring of infectious disease patients wearing wearables. The left panel in

Figure 2 shows the manufactured biological signal measurement module and the right panel shows the final products.

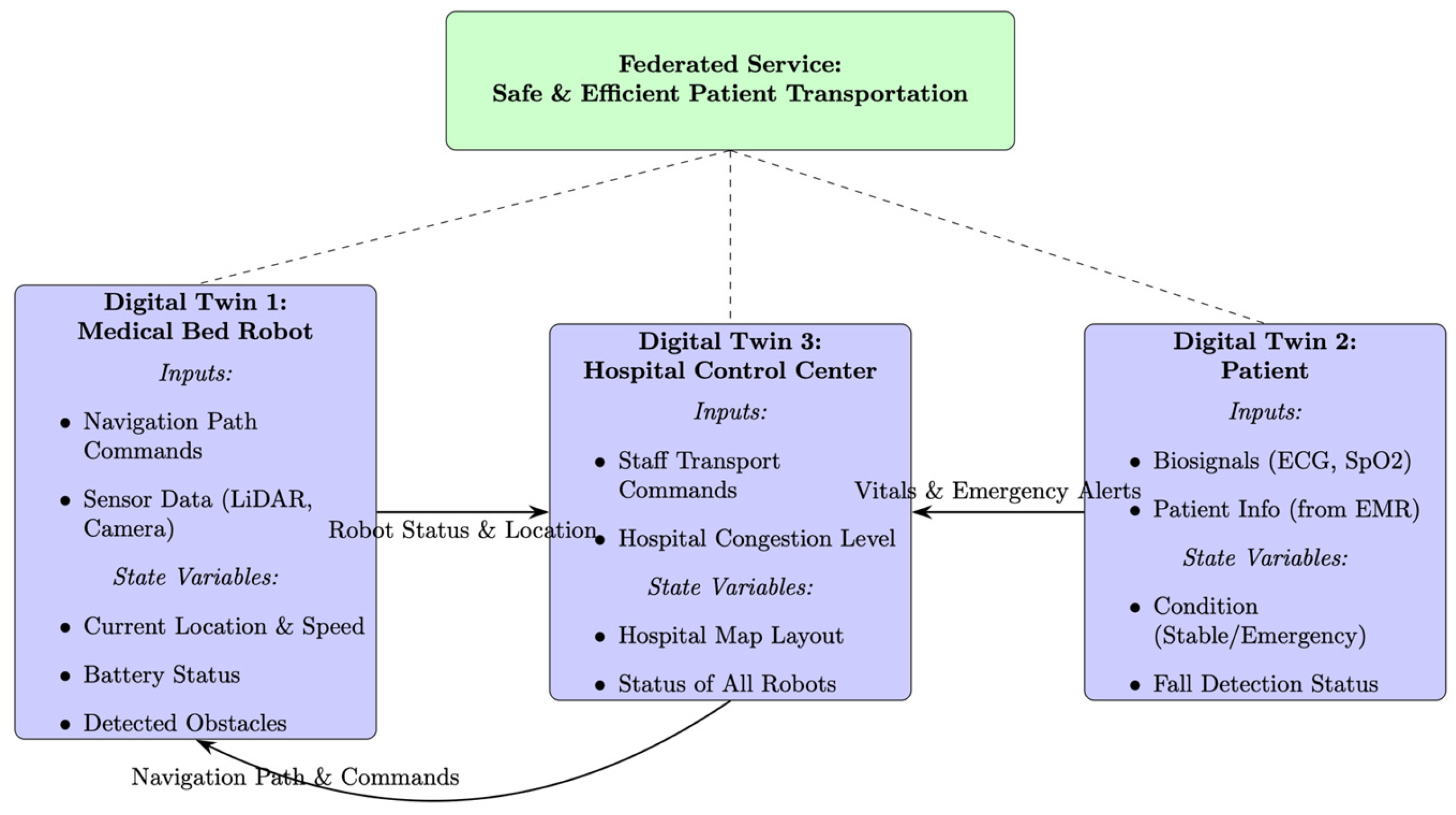

4. Proposed Federated Digital Twins for Patient Transportation

The system’s overall goal is clearly defined as safe and efficient patient transport. The nurse-followed patient transport bed robot (Robot Twin) is a virtual model that receives input on the robot’s physical state (sensor data) and manages information such as its current location, battery status, and obstacle data. It receives navigation commands from the command and control center. Patient (Patient Twin) virtually represents the patient’s current state by receiving vital signs from the patient’s wearable sensors. It sends alerts to the command and control center in case of emergencies. The command and control center acts as a central hub, receiving commands from medical staff, synthesizing the status of all robots and patients, calculating optimal routes, and issuing commands to the robots.

Figure 3 shows the overall framework of the proposed federated digital twins for patient transportation. The arrows clearly specify the types of data exchanged between each twin (robot status, patient alerts, navigation commands) to explicitly show the flow of information.

4.1. Digital Twin Virtualization Technology

Digital Twin Virtualization Technology (DTVT) refers to the digitalization of real-world components including human objects, physical objects, and space. According to the digital twin technology K-roadmap [

1], DTVT consists of eight sub-level technologies including (1) pre-processing real-world data, (2) recognizing objects, (3) visualizing multi-dimensional data and objects, (4) optimizing sensor arrangements, (5) performing correlation analysis and integrating multi-dimensional data, (6) distributed storing, processing, and analyzing digital object data, (7) validating data and extracting patterns, and (8) virtual sensing.

Operation and control of the suggested nurse-following bed robot requires two digital twins—one for the patient being carried and the other for the nurse-following bed robot—and results in the federated digital twins.

Figure 4 shows the overall framework of federated digital twin for medical bed robot operation in the hospital.

The bed robot follows the nurse or medical staff as shown in

Figure 5.

Figure 6 shows the status transmission and recognition process between a patient transport robot and medical staff.

Cognitive Button Input: Medical staff or users press a button on the robot to trigger a specific status or event.

Patient Status Transmission: Monitoring equipment installed on the robot measures the patient’s biosignal in real time. This information is transmitted to a central control system.

Medical Staff Awareness/Standby Mode: Medical staff near the robot’s path or destination can recognize the patient’s arrival through QR codes and switch to standby mode.

Robot: In addition to safely transporting patients, the robot transmits real-time patient condition information and maintains communication channels with medical staff to enable an effective emergency response.

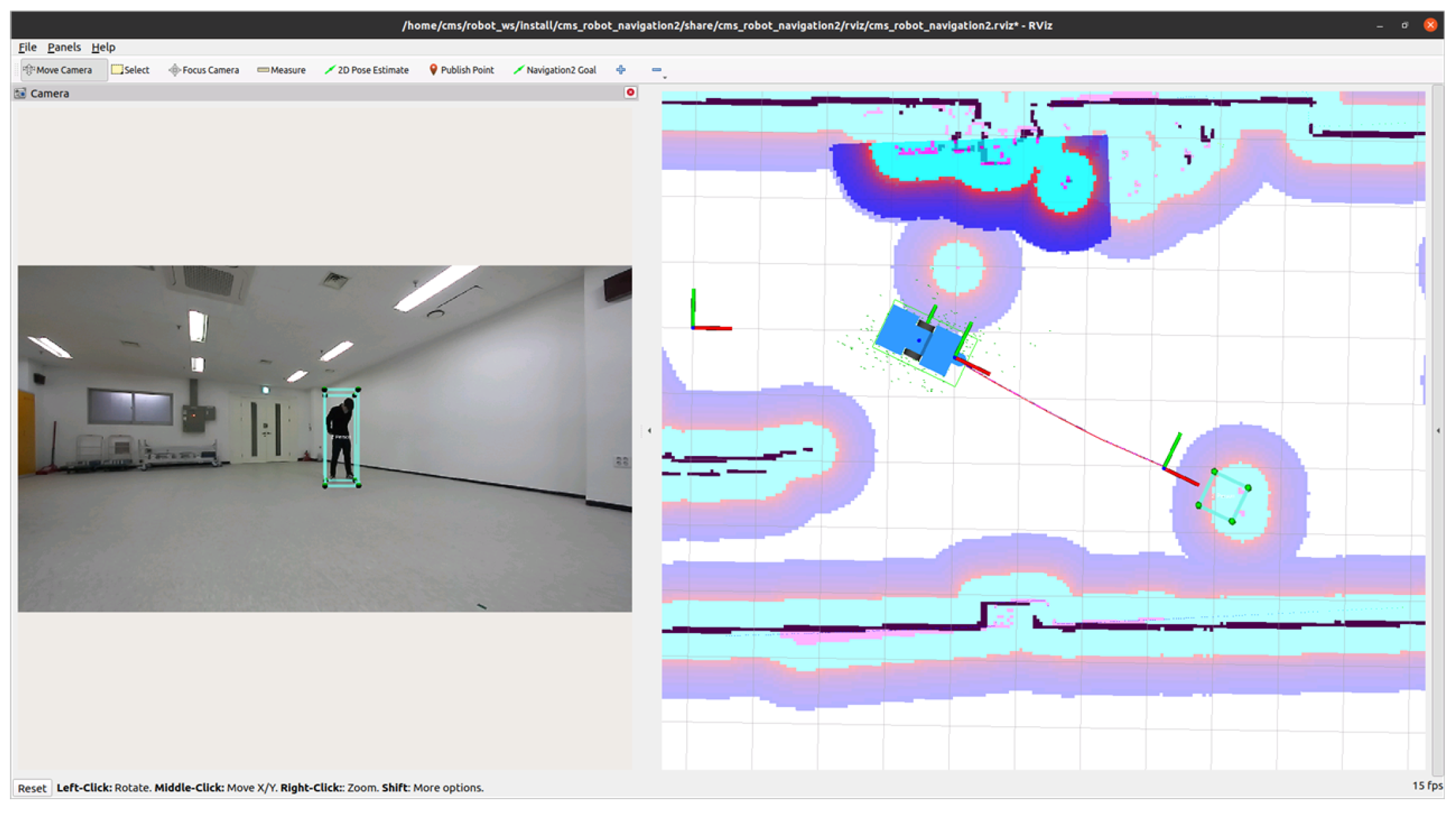

The first step to build a digital twin for the medical bed robot is to identify the terrain where it operates. Two-dimensional pathways of the hospital inpatient ward are pre-processed before the medical bed robot is launched as shown in

Figure 7. This represents the hospital’s inpatient ward. The black lines indicate fixed obstacles such as ward walls and pillars. The light blue areas denote ‘safe zones’, where the robot can move, or open spaces like corridors. The purple area (Costmap) is a buffer zone around obstacles like walls. When planning its path, the robot avoids this purple area as much as possible to reduce collision risk. The map displays the robot itself and the information it perceives in real-time. Green arrows/icons indicate the robot’s current position and direction on the map. Blue and dark blue dots/areas represent obstacles detected in real time by the robot’s sensors (primarily the LiDAR laser scanner). Based on this real-time information, the robot can also avoid sudden obstacles. The red line represents the optimal path calculated from the robot’s current position (green icon) to the target point. This path is intelligently generated to safely reach the destination while avoiding both walls (purple areas) and real-time obstacles (blue areas).

The second step is recognizing human objects, including the nurse to follow and passersby in the ward. The third step is visualizing the multi-dimensional data and objects using vertex and mesh as shown in

Figure 8. The right side of

Figure 8 shows how the AI model interprets the image. The object detection recognizes objects using the bounding boxes and the confidence scores on them. A red line is drawn on the arm portion of the player image on the far right. This visualizes the ‘Pose Estimation’ technology to track key joint positions in humans. Models like PoseNet perform precisely this function. The PoseNet model (TensorFlow.js version 3.20.0) is used to recognize human objects. PoseNet is a deep learning model developed by Google that enables real-time estimation of one or multiple poses within images or videos. PoseNet detects 17 key body parts (keypoints), such as shoulders, elbows, knees, wrists, and ankles, and outputs their coordinates. One of PoseNet’s greatest strengths is its lightweight and fast execution, allowing it to run directly in a web browser. The smartphone screen on the left of

Figure 8 shows an example of how object detection algorithms are ultimately delivered to users.

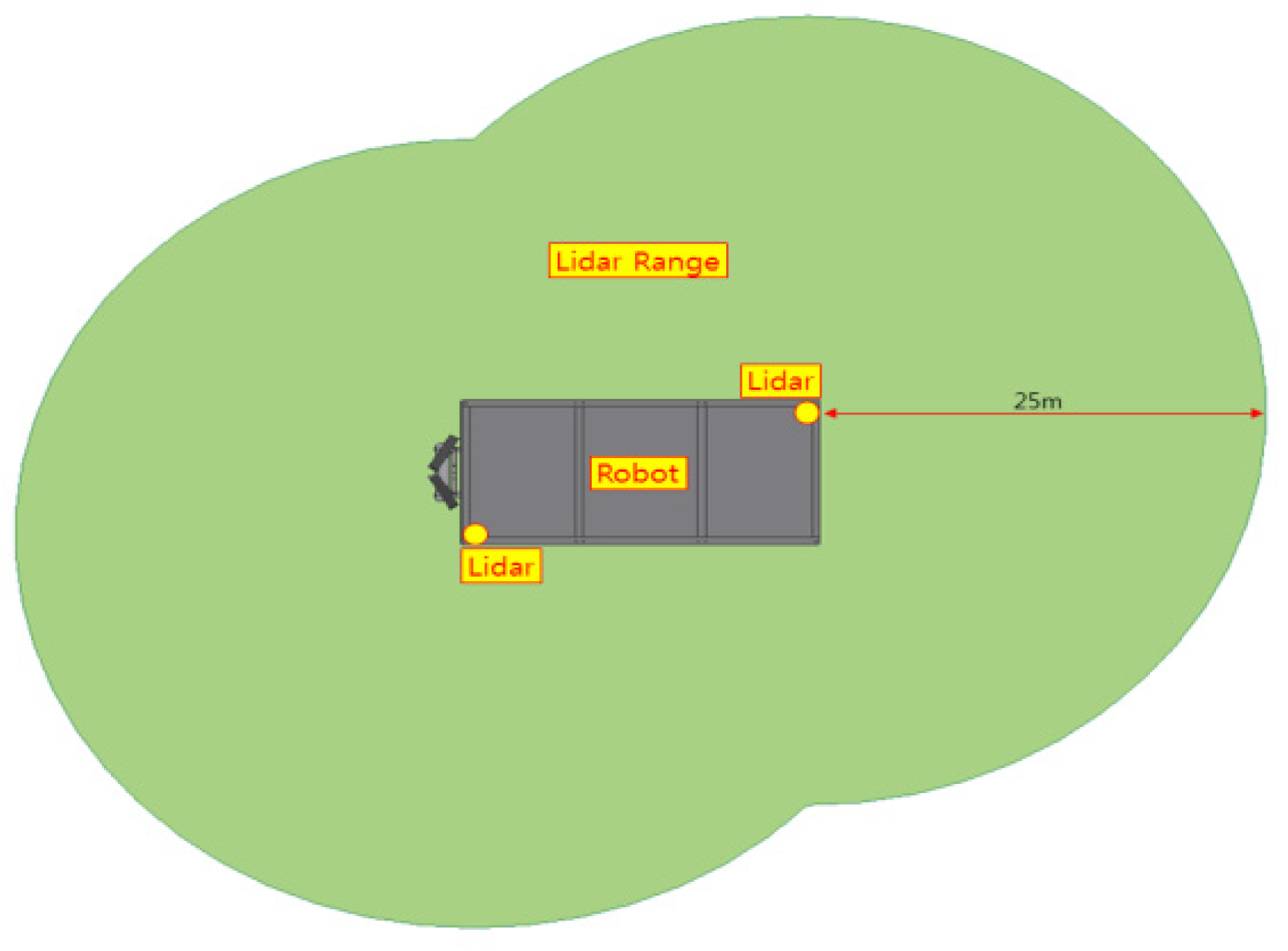

The last step is correlating the medical bed robot and the nurse object to follow, using the optimally arranged sensors, including LiDAR, as shown in

Figure 9. The left figure in

Figure 9 is a schematic showing the placement and detection range of the LiDAR sensors mounted on the robot. It visually illustrates that the robot can detect its surroundings, including the front and rear, up to a maximum of 25 m using two LiDAR sensors. Two depth cameras are installed and used to estimate a person’s posture. The right side appears to be a user interface (UI) screen showing the robot actually recognizing its environment. The left side displays camera footage, while the right side shows a 2D map generated based on sensor data.

4.2. Digital Twin Synchronization Technology

Digital Twin Synchronization Technology (DTST) relates to the real-time inter-reflection between the real-world physical objects and the digital twin virtual object according to the static variable value changes (object, location, time) and dynamic variable value changes (behavior, process, expectation). According to the digital twin technology K-roadmap [

1], DTST consists of seven sub-level technologies including (1) payload reduction and data transmission management, (2) fast and non-lagging data transmission, (3) time and space synchronization, (4) virtualization update, (5) virtual-to-physical actuation, (6) object cleansing, and (7) information validation.

The negative pressure chamber or clean room on top of the medical bed robot collects the patient vital data and relays them to the central control system. Such data include ECG (electrocardiogram), PPG (Photoplethysmography), heart rate, SpO2 (oxygen saturation), motion, negative pressure level of the chamber, GPS location of the medical bed robot, status of the medical bed robot (in-transit, recharge, and return to the base), and status of the emergency situation (cardiac arrest, seizure, and fall).

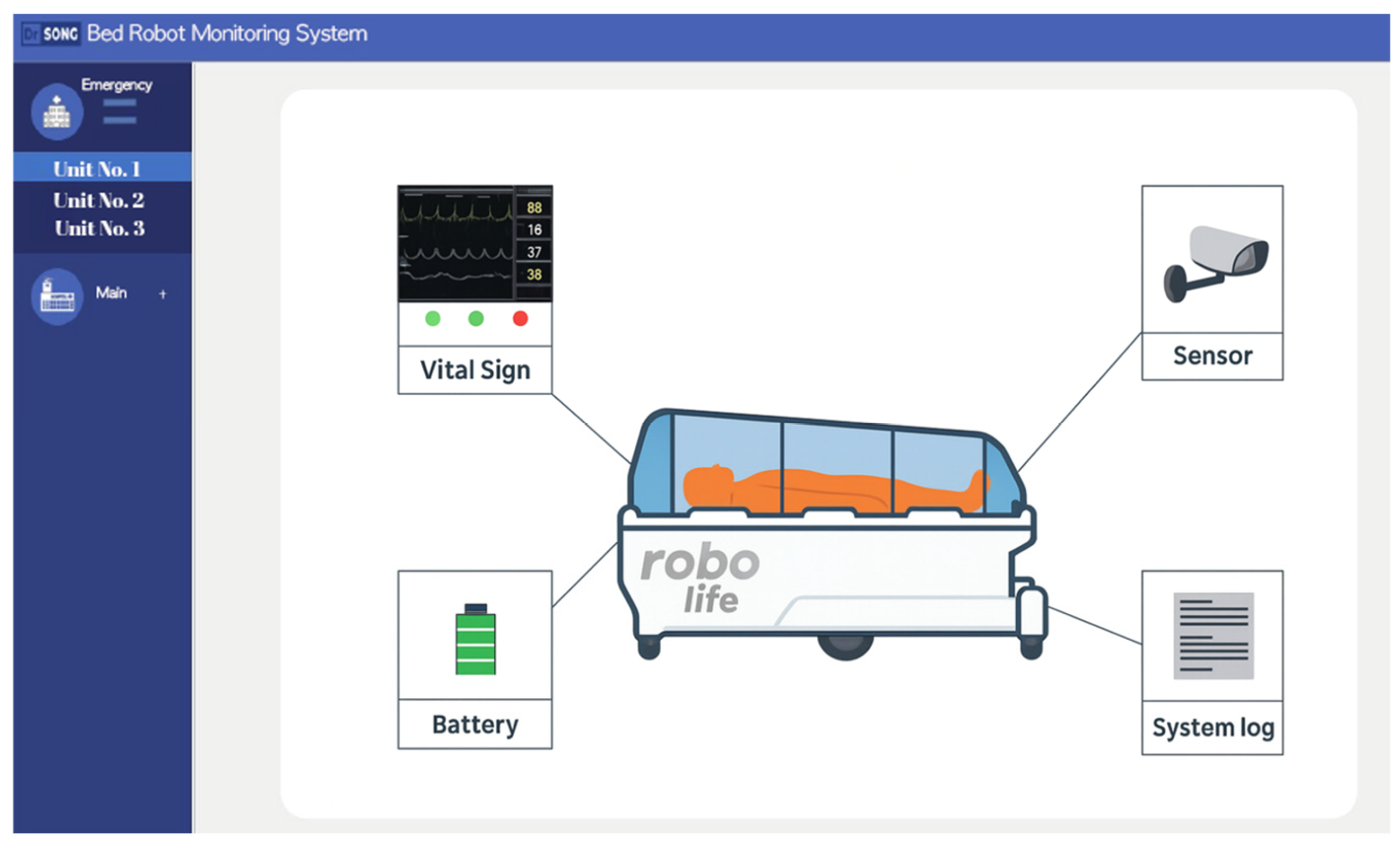

Figure 10 shows the management digital twin system updating and monitoring the patient digital twin.

The first step to build a digital twin for the negative pressure chamber or clean room on top of the medical bed robot is the reduction in the data payload to be transmitted. The ECG and PPG are measured and transmitted by the minute and other sensors are in seconds, thus localized edge control is necessary to reduce the data payload to the command and control center. To enhance interoperability, we abide by the HL7 (Health Level Seven International) FHIR (Fast Health Interoperability Resources) standard. The second step is managing the data transmission to build a digital twin for the patient in the chamber. We use uWSGI (unbit Web Server Gateway Interface) for hosting services. Data flows as follows: The third step is time and space synchronization for the patient digital twin. This system is designed to minimize latency. The uWSGI and Nginx-based server architecture rapidly processes HTTP client requests, ensuring that real-time changes in patient status are accurately reflected in the digital twin model. Furthermore, data processing and synchronization adhere to the HL7 FHIR standard to ensure interoperability of medical data.

Sensor data is processed in real time according to the HL7 FHIR standard and synchronized with the digital patient twin through a uWSGI-based server architecture, following the procedures outlined below. Various sensors (ECG, PPG, SpO2, body temperature, motion detection, robot location GPS, etc.) installed on the negative pressure bed collect data. The sensor data is converted to the HL7 FHIR format to ensure medical data interoperability. The FHIR components for biosignals constitute observation resources including code, valueQuantity, effectiveDateTime, and device. This FHIR structure enables data integration with hospital EMR data. To transmit sensor data to the digital twin server, the Python application server is configured on the uWSGI framework and follows a structure consisting of Nginx ↔ uWSGI ↔ Python App. This quickly receives HTTP client requests and connects them to the Python backend logic to update the digital patient twin object in real time.

The sensor data is passed to various attributes of the digital patient twin. For example, if SpO2 drops suddenly, there will an alarm as an emergency event and triggers virtual-to-physical actuation. This synchronization minimizes latency and ensures that changes in the actual patient’s condition are reflected in real time.

A specially designed gateway platform is developed for the real-time identification of the patient in the negative pressure chamber, as well as the status of the medical bed robot.

Figure 11a shows the gateway platform network. This is the design drawing for the robot’s main control board (PCB, printed circuit board). It precisely shows how various electronic components such as chips, sensors, and connectors will be arranged, along with the board’s overall size and specifications. This board is a core component that acts as a gateway for collecting data from the robot’s various sensors and facilitating communication.

Figure 11b shows the gateway board. This is the actual electronic circuit board manufactured based on the above design drawing. The components from the schematic are physically mounted on the board. The antenna on the right indicates that this board has wireless communication capabilities (Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, etc.), enabling it to transmit the robot’s status or the patient’s vital signs to external systems.

Figure 11c shows the monitoring interface. This is the user interface (UI) screen of the software that visually displays the information collected and processed by the Gateway board above. The top graph shows the patient’s real-time vital signs. This enables continuous monitoring of the patient’s condition even during transport. The bottom status display indicates the robot’s own status such as ‘Battery’ (remaining battery level) and ‘Robot Status’ (robot operational status).

4.3. Digital Twin Federation Technology

Digital Twin Federation Technology (DTFT) refers to federating multiple digital twins for collaboration. A distributed network of digital twins that maintains autonomy while communicating with each other, exchanging data, and performing collaborative simulations through standardized interfaces.

Individual Digital Twins: Each twin collects data from its physical components and represents a virtual model. In our case, each bed robot is an individual digital twin.

Federation Layer: The infrastructure connecting and managing individual digital twins by providing data exchange, security, and access control.

Simulation Engine: Enables users to run simulations on the federated system.

Data Management System: Stores and manages the data generated within the federated digital twin.

User Interface: Provides an intuitive window for users to interact with the federated system by showing the simulation process and results.

According to the digital twin technology K-roadmap [

1], DTFT consists of five sub-level technologies including (1) identification scheme management for digital twin federation, (2) generation, storage, and management of federation metadata, (3) intelligent federation, (4) inter-reliability between digital twins, and (5) federation governance.

Originally, a federated digital twin involves collaboration among multiple institutions. However, in this case, we viewed a single negative pressure bed robot as the primary entity, with a central command and control center that communicates with and manages multiple negative pressure beds as the federated digital twin.

To implement a federated digital twin, we developed a central control system and performed design and development of transmission scenarios and messages for MLLP and HL7 FHIR protocols from many clients. Finally, we performed design and development of a central control server management screen for monitoring semi-autonomous transport robots.

The central server received the following data from robots:

Patient Vital Signs: Electrocardiogram (ECG), photoplethysmography (PPG), heart rate, oxygen saturation (SpO2), etc.

Robot Status Information: Negative pressure function On/Off, GPS location, current status (in transit, charging, etc.).

Emergency alerts: Detection of critical situations like cardiac arrest, seizures, falls.

The central server is designed as the data processing system to process and store transmitted data. For that, we developed software modules to generate and parse collected data into the international standard medical information format HL7/FHIR. This is essential for seamless integration with other hospital information systems. A central control server that supports MLLP (Minimal Lower Layer Protocol) and HL7/FHIR (Health Level 7/Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources) protocols was developed. HL7 (Health Level 7) is an international standard protocol created for exchanging medical information such as patient details, prescriptions, and treatment outcomes between hospitals. MLLP (Minimal Lower Layer Protocol) is a packaging method to reliably transmit the HL7 messages defined above over a network. It is like placing a letter (the HL7 message) inside an envelope (MLLP) for mailing. It plays a role by clearly marking the start and end of the message, ensuring the data is delivered intact without corruption.

Figure 12 shows the diagram showing the overall server structure. It follows a standard web server architecture, where the NGINX web server receives requests from external clients (Clients), forwards them to a Flask-based web application, and stores processed data in a MariaDB database.

Figure 13 shows a system for centrally monitoring and managing the status of multiple robotic beds deployed throughout the hospital in real time. The left screen visually displays the total number of robotic beds assigned to each building within this zone, along with the current status of each robot. The right screen provides more detailed information about specific robotic bed issues and shows the activity logs for all robots in chronological order. In the upper right corner, a message stating “Emergency Unit No. 3 Malfunction” appears alongside a red flashing light icon. This allows the administrator to immediately recognize that a malfunction status occurred with Unit No. 3 through the orange color on the left screen. The Real-time Monitoring System log in the lower right corner sequentially records detailed information such as each robot’s unique ID, the event (status) that occurred, and the time it occurred. Administrators can use this log in identifying the cause of a problem and tracking a robot’s past actions. This system has strengths as follows: This system instantly catches the location and status of all robots with colored indicators. When an issue occurs in a specific robot, it displays warning messages instantly. A single administrator can efficiently manage multiple robots centrally.

4.4. Digital Twin Intelligent Services

Digital Twin Intelligent Services (DTIS) relates with the service lifecycle management. According to the digital twin technology K-roadmap [

1], DTIS consists of six sub-level technologies including (1) service evaluation, (2) service search, (3) intelligent service resource management, (4) service sustainability, (5) anomaly detection, and (6) user friendly representation in VR/AR (virtual reality and augmented reality).

At this stage, only the first step for service evaluation is carried out. We established a multifaceted performance evaluation system by practically applying the GOMS model. GOMS model, a set of Goals, a set of Operators, a set of Methods for achieving the goals, and a set of Selections rules for choosing among competing methods for goals.

The roles of GOMS can be classified into three as follows: First, it structures the complex tasks. Patient transport is not simply the process of moving from point A to point B. It involves numerous intertwined variables, including medical staff judgment, the patient’s condition, and the hospital environment. The GOMS model provided a framework for systematically decomposing this complex task into analyzable units.

Goals: The top-level goal was clearly defined as ‘Delivery’ (patient transfer completion). This became the clear Key Performance Indicator (KPI) measured in the simulation: ‘Total Time Taken’.

Methods: Defined the various approaches used to achieve the goal. For example, the transfer task could be performed by ‘experienced medical staff’ or ‘novice medical staff’. Furthermore, the transfer method and speed also vary depending on the ‘severity of the patient’ being transferred. GOMS identified these ‘user types’ and ‘patient conditions’ as key ‘methods’ affecting performance.

Second, the most crucial role of the GOMS model is converting difficult-to-measure human-centered and environmental factors—such as ‘staff skill level,’ ‘task difficulty,’ or ‘hospital congestion’—into specific parameters that simulations can calculate.

Operators: Defined the basic behavioral units within the transfer process and linked them to measurable values. For example, abstract concepts like ‘Difficulty’ or ‘Effort’ were defined as concrete time values such as ‘Preparation time before/after transfer’ or ‘Average time to reach target speed’.

Selection Rules: Rules determining which method is selected under specific situations were established. The most representative selection rule in this study is ‘Hospital Congestion (Situation)’. By setting the logic ‘If the number of patients in the ward exceeds a specific threshold (Situation)’, ‘The movement speed decreases (Rule)’, the impact of a congested environment on transfer time could be realistically reflected in the simulation.

Third, GOMS analysis provided the theoretical and empirical foundation for deriving the core input variables required for the FlexSim 2023 simulation model. Each element of GOMS is directly linked to specific parameters in the simulation. The GOMS model will serve as an important bridge for analyzing, quantifying, and translating complex real-world transportation tasks into a language that the simulation could understand.

We defined the GOMS model for the usability test of scenarios and simulation results to develop the digital twin as shown in

Table 1.

5. Process Modeling and Simulation as a Basis of Digital Twin

5.1. Process Analysis

First, we analyzed the entire process of transporting infected patients within an actual hospital environment. Using the 4M1E analysis technique, we systematically decomposed each step of the existing manual transport process (pre-triage station, isolation room transfer, CT scan, etc.).

Man (Personnel): Who is involved? (e.g., doctors, nurses).

Machine (Equipment): What equipment is used? (e.g., negative pressure bed robot, standard hospital bed, monitoring equipment).

Material (Supplies): What items are required? (e.g., medical devices, medications, emergency kits).

Method (Procedure): What procedures or methods are followed? (e.g., KTAS consultation, patient transport guidelines).

Environment: Where is it performed? (e.g., emergency room, negative pressure room, isolation ward).

Table 2 was created to provide an at-a-glance understanding of how resources are utilized at each stage. We placed the horizontal axis (Process stages) to arrange chronologically, following the patient’s flow: Consultation → Pre-admission tests → Transfer to isolation ward → Entering isolation ward → Life in isolation ward → Preparing for bed transfer → Bed transfer → Completing inpatient treatment. The vertical is built with 5M analysis elements.

5.2. Scenarios Development

Through the process analysis, we identified six key transport scenarios (e.g., home-to-medical facility, intra-hospital movement) where autonomous robots could be deployed. This phase defines the real-world ‘what’ to model, forming the foundation for the simulation. We developed scenarios such that they systematically organize the entire process from a patient’s arrival at the hospital to the completion of treatment using the 4M1E analysis technique. These simulation scenarios are as follows:

From the process mapping as shown in

Figure 14, we could build the five scenarios.

Scenario 1: Upon the patient’s arrival at the hospital via ambulance. Evaluates proper use of the negative pressure clean room.

Scenario 2: Patient triage before entering the emergency room. Evaluates vital sign measurement, treatment of infected patients, etc.

Scenario 3: Autonomous driving in a crowded environment with multiple people. Evaluates the robot platform’s control capabilities.

Scenarios 4 and 5: Evaluate autonomous navigation in confined spaces and vital sign monitoring.

We identified the sub-tasks for transport performance assessment, as shown in

Table 3.

Table 4 shows the control variables used in the five different scenarios for digital twin simulation. Each scenario is designed to simulate various hospital operations by setting different values for medical staff processing speed and preparation and completion times related to patient transfer.

5.3. Evaluation of Negative Pressure Bed Usage

An empirical evaluation of the infectious patient transport model system was conducted for the scenario depicted in

Figure 12. This evaluation was performed by an assessment panel consisting of 10 experts from eight fields including nursing, infection control, and emergency medicine at Osong Bestian Hospital. The evaluation was conducted using an actual male virtual patient (175 cm, 70 kg) instead of a manikin, based on five real-world scenarios: ambulance arrival, emergency room treatment, navigation in congested and confined environments, and vital sign monitoring.

The final evaluation score for this patient transport system was 92.46 out of 100 points.

Breaking it down by component, the ‘Semi-Autonomous Robot Platform’ scored 28.44 out of 30 points. The target recognition rate was 97.50 points, maintaining excellent recognition even when obstructed by people. However, the ‘error and malfunction response’ category scored only 87.20 points, leading to suggestions such as the need for a quick guide for first-time users. Additionally, there were opinions that the evasive maneuvers during driving were too large, potentially limiting actual entry into hospital wards.

The ‘Negative Pressure Clean Room (Negative Pressure Bed)’ scored 28.37 out of 30 points. Its ‘Infection Factor Control’ performance scored 96.73 points, evaluated as superior to existing negative pressure stretchers. However, ‘Ambulance Compatibility’ scored only 90.00 points, which was deemed insufficient. While loading into an ambulance is possible, equipment interference occurs, and only one port can be used. Other issues noted included difficulty connecting to the stretcher, a rearward shift in the center of gravity, and the absence of a battery-level warning function. The ‘Vital Signs Monitor’ scored 18.78 out of 20 points. Its operating time (96.00 points), enabling 200 h of continuous use, was highly rated, but charging ease (92.50 points) was relatively weak. Key improvement requests included the need for future upgrades to display blood pressure (BP) and electrocardiogram (ECG) readings, as it currently only measures pulse and oxygen saturation. The ‘Infected Patient Treatment and Management’ category scored 9.00 out of 10 points. While ease of emergency treatment (94.00 points) was excellent, ‘Patient Safety Management’ scored only 87.00 points. This was due to evaluations that the robot’s movement was somewhat clumsy and its connection to the stretcher was not sufficiently secure.

Finally, ‘Quality Management and Post-Management’ received the lowest score: 7.87 out of 10 points. Particularly, compliance with the ‘Medical Device Quality Management System (GMP)’ scored only 75.00 points. While the negative pressure clean room obtained GMP certification, the primary reason was that the vital sign monitor failed to receive certification. Furthermore, since it integrates products from three manufacturers, there is a need for integrated warranty services. It was also pointed out that the user manual is difficult for beginners to understand and requires improvement.

Table 5 outlines the main performance indicators, their scoring breakdown, and the methods for quantitative evaluation.

Table 6 shows the final consolidated results of the demonstration test.

5.4. Physical Modeling

Digital Twin Modeling and Simulation (DTMS) refers to analyzing and predicting the information on human objects, physical objects, and the space based on virtualized objects information. According to the digital twin technology K-roadmap [

1], DTMS consists of six sub-level technologies including (1) physical modeling, (2) behavior modeling, (3) rule modeling, (4) scenario generation and tailoring, (5) digital twin simulation, and (6) modeling validation. At first, we selected a COVID-19–dedicated inpatient ward for physical modeling as shown in

Figure 9. The physical model was based on the COVID-19 dedicated ward at the Ilsan Hospital of the National Health Insurance Service. This ward was designed for actual infectious disease response, with clear characteristics such as patient movement routes, bed layout, nursing station locations, and negative pressure isolation zones, making it an ideal environment for digital twin simulation. Based on actual measurements of the ward floor plans and structural information of a hospital, a 3D spatial layout was constructed. Based on Ilsan Hospital’s response system and floor plan, a virtual patient movement path was implemented.

Figure 15 illustrates the floor plans of a COVID-19–dedicated inpatient ward, which was selected as the reference environment for physical modeling in the study. The first-floor layout includes entrance and exit points for patients and medical staff, designated paths for patient movement and medical staff circulation, and key areas such as nurse stations, isolation rooms, and treatment zones. The 11th-floor COVID-19 inpatient ward shows patient rooms and isolation areas. Staff-only zones are designated to reduce cross-contamination risk, with clearly separated contaminated and clean zones. The 13th-floor COVID-19 inpatient ward shows a similar zoning concept with isolation rooms and staff pathways, with red pathways indicating contaminated zones and blue pathways indicating clean circulation areas for medical staff. The floor plan strictly separates clean and contaminated areas (zoning) to emphasize infection control and minimize contact between patients and staff. We verified key concepts and proactively reviewed identified issues. Then, we commenced actual modeling and developed it to reflect the characteristics of emergency wards. We modeled the movement paths, waiting times, and bed occupancy flows of patients and medical staff. This allows us to accurately reproduce various situations that may occur in actual clinical environments.

5.5. Simulation Setup

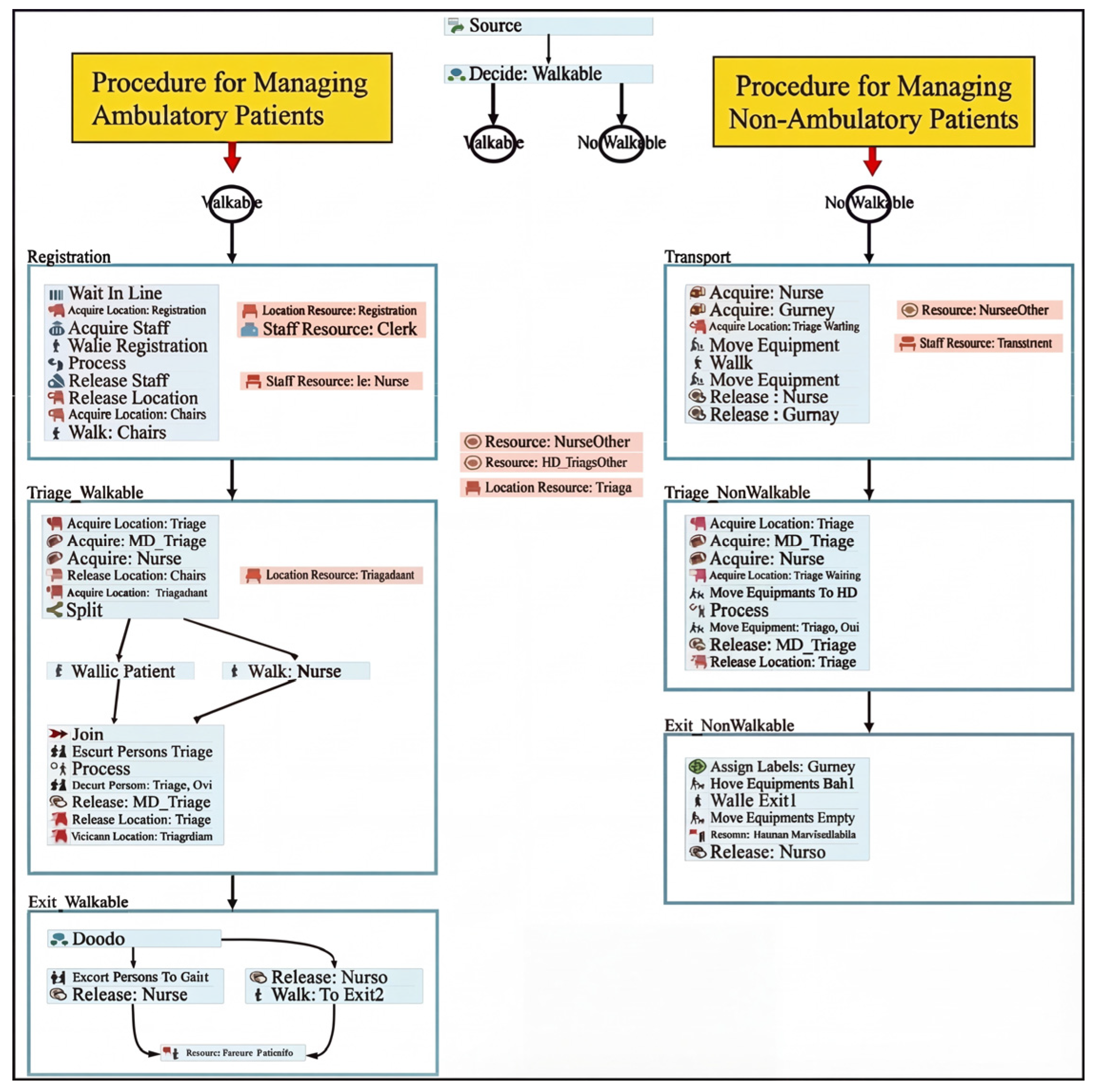

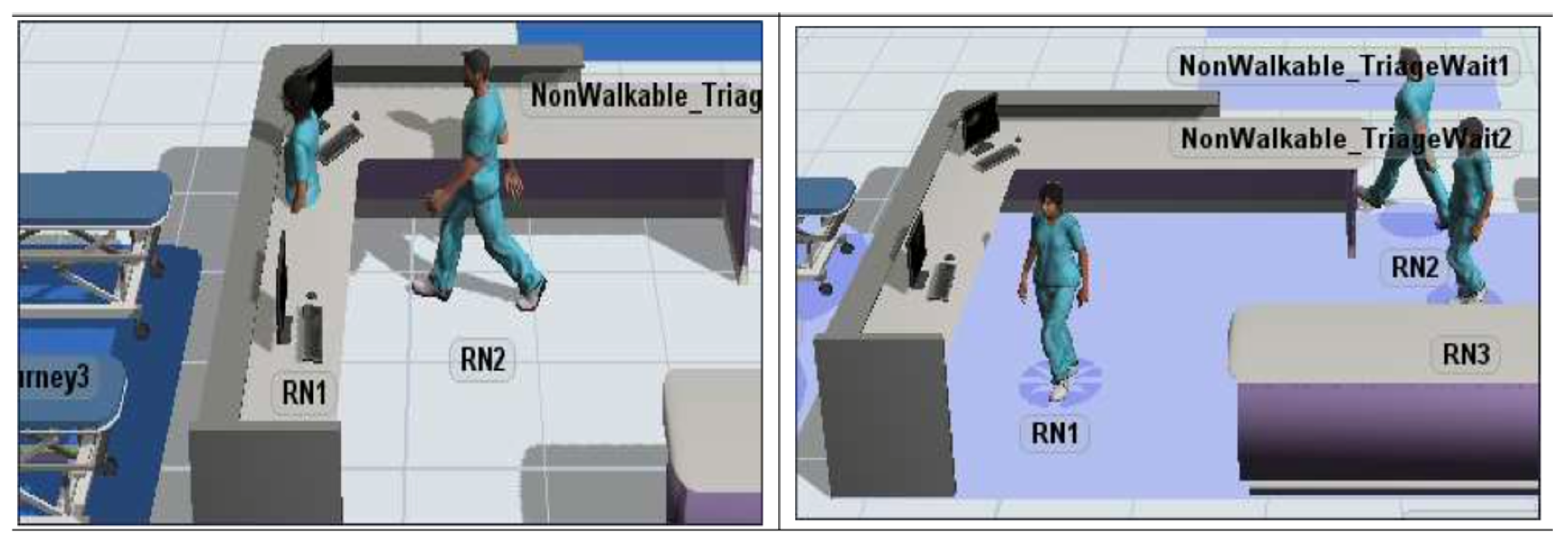

Next, FlexSim simulation is carried out for the patient behavior modeling for registration and transport. FlexSim is a discrete event simulation platform optimized for healthcare logistics.

Figure 16 shows a scenario modeled with the assumption of a dedicated infectious disease ward within a hospital, where the patient registration and transportation processes are branched according to whether the patient is whether able to walk or not. The left panel shows the 3D simulation space reflecting of the actual hospital structure with the following components.

Ambulance1: Ambulance where patients arrive.

Entrance_Ambulatory/Entrance_NonAmbulatory: Separate entrances for patients who can walk and those who cannot.

Chairs1, Registration1, Triage1: Waiting chairs, registration area, and triage (patient severity classification) area.

Nurse Station A1: Nurse station (RN1, RN2, RN3 indicated).

Exit/Exit2: Patient movement termination point.

In this step, processes such as patient arrival, classification (triage), transfer method, and bed assignment were modeled using agents to reflect operating procedures happening in the hospital.

Figure 16 visually illustrates the patient flow simulation structure. The right panel shows that, depending on the patient’s condition, the system determines whether the patient is able to walk or not, and the simulation is divided into two scenarios at the simulation start point. The left panel shows the procedures for walkable patients to register and wait with sequences of Wait in Line, Acquire Location/Acquire Staff, Walk to the registration location, Proceed with the registration procedure, Release resources after registration, and Acquire Location/Walk (Move to the next location). The right block represents the transport procedure for unwalkable patients. It is currently marked as Custom Code: TBD, indicating that it will be implemented later.

The third step relates to rule modeling for medical staff to respond to patients who are capable or incapable of walking, as shown in

Figure 17. We also build scenarios for medical staff, considering the handling speed of the triage nurses, physicians at the emergency room, and general staff, along with the preparation time for transport and the finishing time for transport. The left process shows the three steps to handle the walkable patients. The first step is Registration consisting of Wait in line, Acquire Staff, Acquire Location, Walk to the registration location, Process registration, Release Staff, Release Location, and finally Move to the next area (triage). The second step is Triage consisting of Join the queue, Acquire Nurse, Walk, Process (Evaluate the patient’s condition), and move to the next location with the nurse. The third step is Exit Processing, consisting of Decide the exit direction, Walk to the exit, and Release Nurse.

We ran simulations based on the pilot model and faced a shortest-path problem: mobile resources pass through facilities and items, as shown in

Figure 18. To overcome this problem, we added an A-star module and network node to manage movement paths.

We then modeled the nurse-following robot and reflected parameters related to movement speed to examine the mobility of the people-following robot platform. We finally developed additional concept models and reexamined ways to reflect parameters related to movement speed. The model view of the concept model for parameter verification and the main variables reflected are as follows:

Transport Difficulty: An attribute label assigned to indicate the difficulty of transporting patients (randomly selected from 1 to 10). This is a variable that affects the preparation time before and after transport and is handled in direct proportion.

Area Type: Expresses speed change points as spot objects and subdivides them into straight, curved, and sloped.

Assign attribute labels indicating the type of area to be entered next at each speed change point.

Speed change points are generated separately for each direction.

5.6. Simulation Results

For the simulation, we set up 20 seats in the waiting area, one reception counter, four nurses, one doctor, and eight hospital beds. We set the process parameters according to scenarios as shown in

Table 5. The simulation is carried out 20 times. We set up the KPIs of length of stay (LOS), average movement distance of staff, and average patient handling time of staff.

Table 7 shows the specification of the generated scenarios.

LOS refers to the total time a patient spends in the emergency department, from the moment they arrive until they complete all procedures—including treatment, tests, and transfers. LOS is the most representative indicator of operational efficiency for hospitals, particularly emergency departments. A prolonged LOS lowers bed turnover rates, leading to emergency department overcrowding, which can make it difficult to accommodate new emergency patients. In infectious disease scenarios, the longer a patient stays in the hospital, the greater the risk of cross-infection. Therefore, reducing LOS is a critical goal directly linked to patient safety. By introducing autonomous robots to ensure swift and systematic patient transfers, unnecessary waiting times can be reduced, contributing to an overall decrease in LOS.

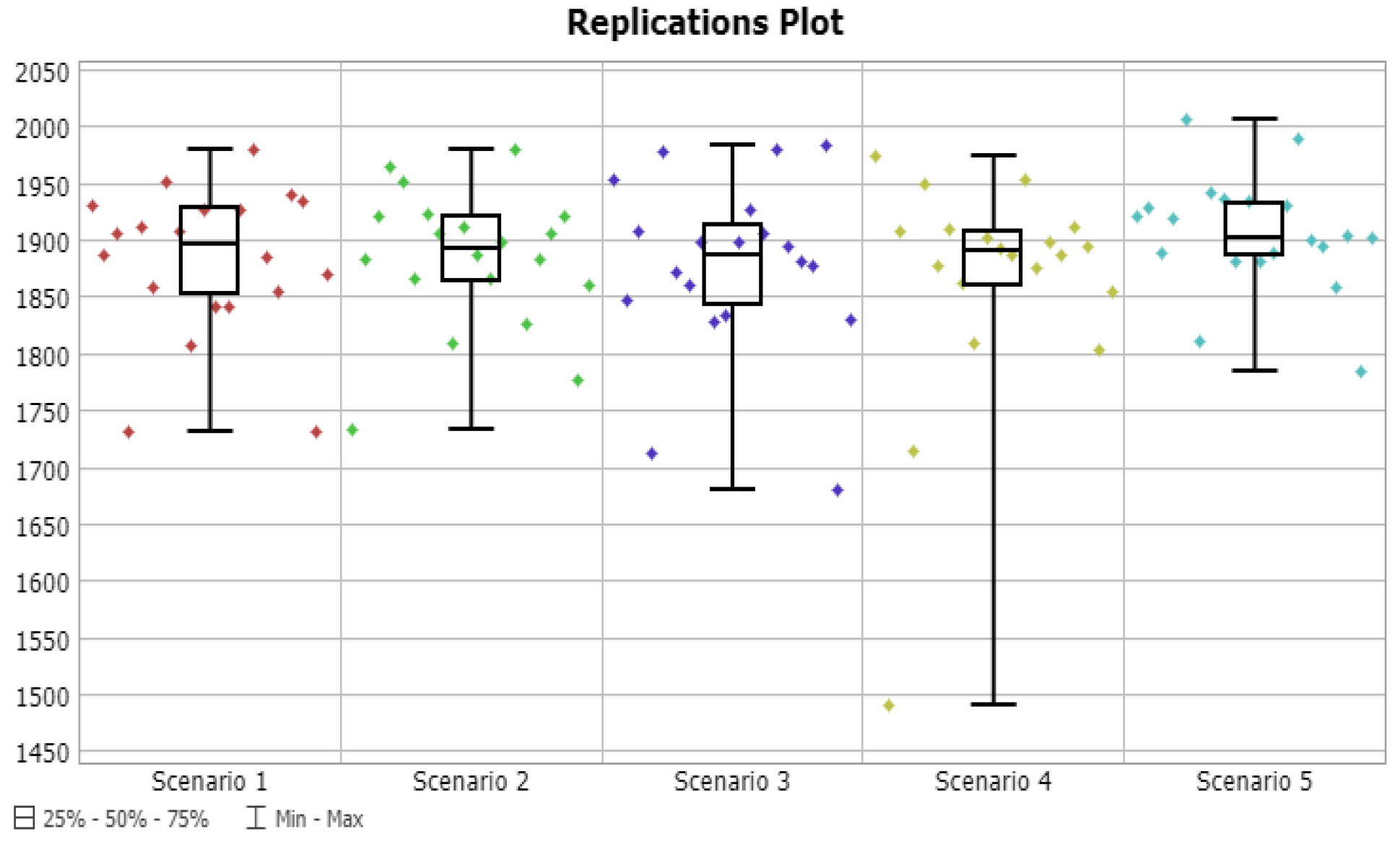

We received the following results from five scenarios.

Table 6 shows the mean and confidence intervals of LOS according to the scenarios. Replication plots are shown in

Figure 19. Analysis results showed that Scenario 4 recorded the lowest average LOS at 1863 s, while Scenario 5 exhibited the highest value at 1905 s. However, the 90% confidence intervals largely overlapped, indicating no statistically significant difference between the scenarios. The details of LOS are shown in

Table 8.

‘Average movement distance of staffs’ metric represents the average total distance traveled within the hospital by medical staff to perform patient transfers and related tasks. Staff travel distance is directly linked to physical workload burden. Transporting infected patients is particularly taxing due to tasks like donning protective gear. Having autonomous robots handle patient transport significantly reduces unnecessary trips between wards for staff. This reduces staff fatigue and allows them to focus more time and energy on patient care, contributing to improved healthcare service quality.

According to

Figure 20 and

Table 9, Scenario 1 showed the shortest average travel distance at 10,387 m, while Scenario 5 had the longest at 11,243 m. This metric also failed to reveal significant differences between the scenarios due to large standard deviations and overlapping confidence intervals.

‘Average patient handling time of staff’ represents the proportion of a healthcare worker’s total working hours spent on actual tasks (diagnosis, treatment, transport preparation, follow-up, etc.). When this metric is too high, it means staff are suffering from excessive workloads, which can increase the risk of burnout or medical errors. One purpose of introducing autonomous robots is to optimize the time spent by medical staff on tasks by delegating patient transport duties to robots. This allows medical staff to shift focus away from labor-intensive patient transport tasks and concentrate more on their core professional medical activities, thereby enhancing the overall efficiency of workforce management within the hospital.

According to

Figure 21 and

Table 10, Scenario 2 showed the lowest utilization rate at an average of 16.8%, while Scenario 4 showed the highest utilization rate at 19.0%. The absolute difference between scenarios was minimal. Simulation results showed no significant differences in performance evaluation metrics across scenarios overall. Parameters related to movement speed did not significantly impact performance evaluation metric values. As the current model itself is not highly complex, no differences in performance evaluation metrics appear to be evident. Therefore, future modifications are considered necessary to increase patient arrival rates or reflect additional task execution by staff. Monthly simulation analysis plan, annual report follow-up, and model modifications will proceed to enable meaningful multi-scenario analysis through comprehensive revisions. Logic for concurrently transferring patients using bed robots and existing personnel will be implemented. Simulation analysis will be conducted in an actual environment applying another hospital emergency room layout. These simulation scenarios and result data will be given upon request.

We efficiently measure routes in terms of dwell time, average staff travel distance, and average patient processing time. Although we set up different scenarios, the workload was not heavy, so the differences between the metrics were minimal. As for future work, we plan to set up scenarios for more complex cases involving a sudden influx of many patients. Since such situations have not actually occurred, we did not conduct experiments for that scenario in the current study. We will investigate other studies to set up complex situations that seem likely to occur in reality. Because the current scenario reflecting the actual situation has a low workload, the simulation time and response time are real-time.

Five scenarios were established by classifying them into groups based on the number of transport personnel and basic movement speed. After executing the models created for each scenario, performance evaluation metrics and statistical aggregates were calculated. Performance evaluation metric statistics for each individual scenario were aggregated weekly. The aggregated performance evaluation metrics—specifically the daily values for average movement distance and average task duration—will be disclosed upon request.

6. Conclusions

In this study, we designed and implemented a nurse-following medical bed robot equipped with a negative pressure bed to support safe and efficient patient transport, even in infectious disease situations. The core feature of this robot system is the application of a federated digital twin (FDT) architecture, which constructs independent digital twins for both the patient and the robot and interconnects them. We proposed a structure that independently configures digital twins for patients, medical staff, and robots while synchronizing data in real time. This enables the implementation of a more flexible and scalable system applicable for various medical institutions. We integrated the five core digital twin technologies of virtualization, synchronization, modeling and simulation, federation, and intelligent service into the actual system. In particular, we added FlexSim-based simulation, GOMS model-based user usability evaluation, and HL7 FHIR-based sensor data integration.

The main contributions of this study are as follows: First, previous studies addressed follow-me robots assisting nurses or digital twin technology in healthcare individually. However, this research is the first attempt to combine a negative pressure bed robot for safely transporting infectious disease patients with nurse-following technology, then implementing this integrated system as a digital twin. Second, a single digital twin has limitations in managing environments like hospitals, where multiple robots and patients interact complexly. This research proposes a federated digital twin architecture that builds independent digital twins for both patients and medical bed robots and links them together. This approach, not attempted in previous digital twin research in the medical field, enables a more flexible and scalable system by synchronizing data from multiple medical devices, patients, and medical staff in real time. Third, unlike previous studies that primarily focused on single-task training using augmented reality (AR) or virtual reality (VR), this research extensively connected the physical space of an actual hospital (COVID-19–dedicated ward blueprint) with cyberspace. Furthermore, it distinguishes itself by analyzing and validating patient movement patterns, medical staff workload, and average length of stay (LOS) through user evaluations using the GOMS model and FlexSim simulations based on specific scenarios, thereby predicting its effectiveness when applied to actual medical settings.

We present the future direction of robot collaboration in the healthcare field. Robot-based patient transport is emerging as a core technology that goes beyond simple automation to reduce the burden on medical personnel and enhance patient safety. This study comprehensively presents the design, implementation, and verification methods necessary for robots to operate in actual medical settings, thereby providing a practical direction for the introduction of medical robots. Although this study is based on cases in South Korea, the proposed system is scalable and universal, as it can be modularized and applied according to the hospital environment, regulations, and infrastructure of each country. In particular, the federated digital twin structure can be applied to collaboration between global healthcare systems, and pilot testing and interoperability verification between multinational hospitals will be necessary in the future. Going beyond the technical implementation applied to a single hospital, subsequent research should focus on establishing a collaborative system between medical staff and robots, and achieving technological advances that enable application in other institutions and even overseas. Once this foundation is established, the clinical application and global spread of autonomous medical robots will become possible.

As a minor issue, this research focuses on the current design and implementation, integrating existing, proven deep learning models such as PoseNet into the system. It does not include considerations for managing the model lifecycle, such as retraining or model update cycles, to prevent performance degradation that may occur during long-term AI model operation. To address this, a continuous MLOp (Machine Learning Operation) pipeline can be established. The key is to create a cyclical structure encompassing monitoring, retraining, validation, and deployment. A robotic camera continuously collects image data in an actual hospital environment. The monitoring system detects that the PoseNet model’s human recognition accuracy is declining (e.g., failing to recognize newly designed uniforms). An automated retraining pipeline activates, updating the model with the newly collected image data. The updated model is first thoroughly simulated in a digital twin environment to verify its stability and performance.

This study focused on the conceptual design and process efficiency verification of the proposed FDT architecture and thus has the following limitations. The simulations in this study (

Section 5) focused on analyzing process efficiency (e.g., patient LOS, staff movement paths) and did not include robustness testing of the actual IT infrastructure. Data latency, node dropout, computational bottlenecks on the central server, and data synchronization errors are critical issues that must be considered when scaling and deploying dozens of robots in a real hospital environment. Although this system considered minimizing latency by design using the Nginx/uWSGI stack and MLLP protocol, stress test simulations setting these factors as variables to test the system’s limits were not performed. Future research must simulate the impact of network failures or sudden robot malfunctions (node detachment) on the entire system and patient safety, and develop a distributed exception-handling protocol capable of responding to such events.

In addition, future research should explore methods to fundamentally prevent personal information leaks by training local models on each robot without sending raw data collected from individual robots to a central server, then integrating only parts of the models (such as weights) at the central server. Developing intuitive digital twin interfaces for medical professionals is also a future research topic.