1. Introduction

Semantic matching constitutes a fundamental computational task within natural language processing, centered on modeling the semantic relationship between two textual units, such as sentences, queries, or phrases, to determine their degree of equivalence, relevance, or entailment. The key challenge lies in constructing models capable of accurately capturing deep semantic and pragmatic relationships, thereby transcending mere lexical overlap to achieve genuine comprehension of meaning. A quintessential and high-stakes application of semantic matching is text retrieval, wherein the goal is to identify, from a large corpus, the texts most semantically relevant to a given query.

As a cornerstone of natural language understanding (NLU), advances in semantic matching have a direct and significant impact on a wide range of downstream applications. These include open-domain question answering, conversational dialogue systems, information retrieval, and machine translation [

1]. In practice, NLU-based semantic matching is commonly implemented through transformer-based encoders (e.g., BERT, RoBERTa) that map input text into dense vector representations, followed by similarity functions such as cosine similarity or learned interaction layers to compute semantic relevance. Fine-tuning pre-trained language models on labeled datasets (e.g., SNLI, Quora Question Pairs, or MS MARCO) enables task-specific alignment of semantic spaces. Additionally, recent approaches incorporate contrastive learning, cross-encoders for pairwise scoring, or knowledge-enhanced architectures that integrate external ontologies or entity linking to improve robustness. The ability to precisely match semantics is crucial for enabling machines to perform tasks that require robust comprehension and reasoning. The growing expanse of digital information has further amplified the demand for accurate and efficient semantic matching models. Consequently, effective solutions not only enhance user experience in critical areas like search and recommendation systems but also facilitate knowledge discovery, information integration, and data-driven decision support across diverse domains such as healthcare (e.g., clinical note matching for patient cohort identification), finance (e.g., matching regulatory documents with compliance queries), and education (e.g., aligning student questions with explanatory resources). Research in this field, therefore, carries substantial theoretical and practical importance, addressing persistent challenges related to linguistic diversity, ambiguity, and computational efficiency.

Over the past decades, semantic matching techniques have evolved from lexical-based methods to latent semantic models, and more recently to neural architectures with contextual embeddings. Early approaches, such as BM25 [

1] and TF-IDF [

2], relied on frequency and co-occurrence statistics, which were computationally efficient but inadequate in handling synonymy, polysemy, and long-range dependencies. Latent semantic models, including LSA, PLSA, and LDA [

3,

4,

5], sought to overcome these shortcomings by projecting texts into low-dimensional semantic spaces, yet they often disregarded syntactic structures and faced scalability issues. The emergence of deep learning and pre-trained language models based on the Transformer architecture (e.g., BERT [

6,

7], RoBERTa, GPT, T5 [

8,

9]) has significantly advanced semantic representation learning. These models, trained on large-scale corpora with masked language modeling, provide dynamic contextualized embeddings and have achieved notable success across NLU tasks. Nonetheless, several challenges persist. Sentence embeddings derived from these models frequently exhibit representational collapse [

10], where semantically distinct sentences converge undesirably, reducing discriminative power. Furthermore, the commonly used random masking strategy in pre-training fails to emphasize contextually important words, limiting the ability to capture fine-grained semantic cues. Finally, task-specific fine-tuning generally requires large amounts of labeled data, which is costly and impractical in specialized domains.

This study adopts a domain-finetuned semantic matching framework, integrating dynamic masking and contrastive learning to enhance semantic matching across diverse domains. The model enhances semantic representation by focusing on contextually significant words and optimizing sentence embeddings with domain-specific data. The main contributions are as follows.

A fully self-supervised, dynamic masking strategy is introduced for semantic matching. Unlike prior methods that rely on external tools or static heuristics, this approach leverages the model’s own cross-entropy loss during masked token recovery to adaptively identify and mask the most semantically salient keywords within sentence pairs. By aligning pre-training with contextual semantics, it directly enhances fine-grained semantic capture for matching tasks.

The framework incorporates a domain-aware contrastive learning component. In contrast to public-domain approaches that often distort specialized terminology through synthetic augmentations (e.g., dropout or back-translation), it utilizes naturally occurring, semantically equivalent sentence pairs from the target domain as positive samples. This preserves semantic authenticity and aligns the learning objective with the core goal of domain-specific semantic matching.

Together, these components form a tightly integrated, end-to-end solution for domain fine-tuning under limited supervision. The synergy between dynamic masking, which focuses the model on critical domain semantics, and subsequent contrastive learning, which structures the embedding space effectively, constitutes a coherent methodology. Experiments demonstrate consistent improvements across both similarity-based and retrieval-based evaluations, confirming its effectiveness in low-resource, domain-sensitive settings.

In sum, this work advances semantic matching by combining dynamic pre-training with contrastive transfer learning. The approach enhances sentence representations while reducing reliance on large-scale annotated corpora, thereby offering a scalable and practical solution for domain-specific applications.

The article’s structure is as follows:

Section 2 introduces the related literature.

Section 3 introduces the semantic matching method employed in this paper.

Section 4 describes the experimental results and provides analyses.

Section 5 further discusses the results, and we conclude in

Section 6.

2. Related Work

The development of semantic matching methods reflects significant trends in natural language processing. This evolution has moved from handcrafted features to data-driven, contextual representations. The advancements can be categorized into three main phases: traditional lexical methods, latent semantic models, and neural architectures with pre-trained contextual embeddings. Each phase introduced important innovations that improved the ability of systems to understand and match semantic content, paving the way for modern semantic technologies.

2.1. Traditional Lexical Methods

Early approaches to semantic matching relied on term-based statistics and exact lexical overlaps. For instance, the BM25 [

1] algorithm used term frequency (TF) and inverse document frequency (IDF) [

2] to assess the importance of words in documents. These models were efficient and easy to interpret. However, they had significant limitations. They struggled with synonyms, polysemy, and semantic relationships beyond shared vocabulary. For example, traditional lexical models would treat “car” and “automobile” as separate entities, despite their semantic similarity. This limitation led researchers to seek methods that could access deeper semantic structures. Other notable approaches in this category include the Vector Space Model (VSM) and TF-IDF [

2] weighting schemes. While these models laid the groundwork for early information retrieval systems and search engines, they operated primarily at a surface level. They lacked mechanisms for conceptual understanding and relational reasoning.

2.2. Latent Semantic Models

To overcome the limitations of lexical methods, researchers developed techniques that could capture implicit semantic relationships. Latent Semantic Analysis (LSA) employed singular value decomposition (SVD) to project the term-document matrix into a lower-dimensional semantic space, revealing latent concepts [

3]. Probabilistic extensions, such as Probabilistic Latent Semantic Analysis (PLSA) [

4] and Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) [

5], refined this idea by modeling documents as mixtures of topics. These models allowed for a more flexible understanding of semantic similarity [

11], capturing relationships between words and documents beyond simple co-occurrence. For instance, they could infer that “journal” and “article” were related, even if they never appeared together in the same document. However, these approaches often required extensive feature engineering and struggled with out-of-vocabulary terms [

8,

9]. They also had limited capacity to model complex semantics, especially in longer texts. Additionally, they typically relied on bag-of-words representations, which ignored word order and syntactic structure, limiting their ability to capture nuanced meanings.

2.3. Neural and Pre-Trained Representation Learning

The rise in deep learning marked a significant shift in the field. It replaced hand-designed features with learned distributed representations [

12]. Fully Connected Neural Networks (FCNNs) [

13], Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [

14], and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) [

15,

16] enabled end-to-end learning of semantic features from raw text [

17,

18]. CNNs excelled at capturing local n-gram information, while RNNs, particularly Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) [

19] and Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) variants, effectively modeled sequential dependencies. These advancements led to more robust sentence and document representations. The development of word embedding techniques, such as Word2Vec [

20] and GloVe, provided dense, low-dimensional vector representations that captured both syntactic and semantic relationships.

Although pre-trained models such as BERT [

6,

7] have significantly enhanced semantic understanding through context-aware dynamic representations, their inherent cross-encoding architecture presents severe efficiency bottlenecks when generating independent sentence vectors [

21]. To compute semantic similarity between N sentences and M sentences, BERT [

22] must process all N × M combinations, rendering computational costs prohibitive for large-scale retrieval tasks [

23,

24]. To address this, Reimers et al. proposed Sentence-BERT, which employs a twin network architecture for independent sentence encoding and generates fixed-size sentence vectors via pooling operations. This enables feasible large-scale sentence semantic similarity calculations based on cosine similarity [

25]. Sentence-BERT has become a widely adopted baseline model for sentence semantic matching tasks. Within the Chinese domain, the Text2vec model has emerged as a formidable contender through targeted optimization. This model undergoes pre-training on large-scale Chinese corpora and is fine-tuned using contrastive learning across vast Chinese sentence pairs, enabling it to generate high-quality, semantically rich Chinese sentence vectors [

26]. Given its state-of-the-art performance on Chinese semantic text similarity benchmarks, Text2vec constitutes another crucial comparative baseline for this study’s cross-domain Chinese text retrieval task.

It is worth noting that such hybrid approaches, while powerful, may introduce discrepancies between the conditions encountered during training and those during inference [

27]. This challenge, akin to the “exposure bias” studied in sequence generation, necessitates careful design to ensure the learned representations generalize robustly to real-world semantic matching tasks.

Existing models, including Sentence-BERT [

28] and Text2vec [

29], typically rely on random masking strategies during pre-training, failing to prioritize semantically critical vocabulary. This limitation constrains their ability to capture fine-grained semantic information. Moreover, generic contrastive learning may introduce semantic distortions in specialized domain texts and fails to account for the unique semantic structures of domain-specific entities. To address these limitations in current state-of-the-art models, this study adopts a novel framework that integrates dynamic masking with contrastive learning, aiming to achieve more effective semantic matching performance in domain-specific fine-tuning scenarios.

3. Methods

This paper adopts a domain-finetuned semantic matching framework that synergistically integrates a fully self-supervised dynamic masking mechanism with a domain-grounded contrastive learning strategy (As shown in

Figure 1). This approach addresses two main challenges: the dependence on static random masking in traditional pre-training and the high cost of obtaining large-scale supervised data. Crucially, our work distinguishes itself by ensuring both components are tailored for domain-specific semantic fidelity: dynamic masking estimates importance directly from the model’s own recovery loss, and contrastive learning leverages naturally occurring, parallel sentence pairs from the target domain, avoiding the semantic distortion risks of synthetic augmentation.

3.1. Model Framework

The proposed model improves key information extraction and supports domain fine-tuning. It does this by using task-specific pre-training and contrastive transfer learning. Specifically, the model consists of the following main modules: Domain-finetuned Pre-training by Dynamic Masking, Transfer Training by Contrastive Learning, Text vectorization by domain fine-tuning, Encoder based on knowledge transfer. The detailed implementation process is described below.

In this component, self-supervised dynamic masking is applied to the input sequence. Unlike prior methods reliant on external tools, our strategy intelligently selects and masks the most semantically salient tokens by evaluating their masked recovery loss using the current model state. The model then works to recover the masked tokens by using surrounding context. A fully connected layer refines the token-level representations. The training objective focuses on predicting tokens, using cross-entropy to measure the difference between predicted and actual tokens. This task-aligned masked language modeling, performed on sentence pairs, helps the model capture essential semantic information, enhancing its performance in downstream sentence-level tasks.

In this part, the input text is transformed into semantic vector representations using a shared text encoder (, , ). A pooling operation compresses variable-length token sequences into fixed-dimensional global sentence embeddings (, , ). These embeddings pass through a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) projection head, which enhances the learned representations. Our contrastive learning framework is then employed to optimize the model. A key distinction from general-domain methods (e.g., SimCSE) is our construction of positive pairs: instead of applying random dropout or back-translation that may corrupt domain terminology, we use naturally occurring, semantically equivalent sentence pairs from the domain corpus. This preserves factual integrity and aligns the contrastive objective directly with authentic semantic matching. By distinguishing between these authentic positive and negative sample pairs, the model learns more discriminative features, supporting effective knowledge transfer from the source domain to the target domain.

In this section, the input text is encoded using a composite embedding representation. Token-level word embeddings , segment embeddings (which represent sentence-level distinctions), and position embeddings (which indicates the position of each token) are generated. These three components are summed and passed through a linear projection layer, creating a unified input representation that captures lexical , semantic, and positional information. This combined embedding serves as the foundational input to the Transformer encoder.

Using the Transformer architecture, the model learns deep contextualized representations of tokens. It captures their semantic, syntactic, and logical relationships. The self-attention mechanism allows for dynamic modeling of global token relationships, while layer normalization stabilizes training and improves convergence. This architecture promotes the transfer of semantic knowledge from the source domain to the target domain, enhancing generalization across diverse input distributions. As a result, the quality of sentence representations improves, benefiting downstream tasks such as semantic matching.

3.2. Dynamic Masking Mechanism

Distinction from Prior Dynamic Masking Methods. Previous dynamic or importance-based masking techniques often utilize external resources (e.g., POS taggers, TF-IDF scores) or pre-defined heuristics to select tokens. In contrast, our strategy is intrinsically self-supervised and model-aware. We dynamically compute the masking recovery loss for each keyword using the current model state during pre-training. Selecting tokens with the highest loss (i.e., the hardest to predict given the context) forces the model to concentrate its capacity on reconstructing the most semantically pivotal units. This process is performed on sentence pairs, ensuring the learned representations are optimized for semantic matching from the pre-training stage.

3.2.1. Semantic Matching-Oriented Pre-Training Strategy

Existing masked language models (e.g., BERT) typically employ a random masking strategy, treating all vocabulary units as equally important, which presents limitations for semantic matching tasks. The core meaning of a sentence is often conveyed by a handful of semantically critical words (e.g., entities, predicates, modifiers). To compel the model to focus more on these pivotal components of sentence meaning and enhance its ability to learn contextual associations for information recovery, we propose a fully self-supervised dynamic masking mechanism.

3.2.2. Core Concept and Procedure

The core idea of this mechanism is to leverage the model’s own performance on the masked token recovery task to dynamically identify and mask the words most critical to the semantics of the current context [

30]. Given an input sentence sequence of length

T:

A keyword, which may consist of multiple tokens, is denoted as .

The procedure consists of three main stages, with the complete algorithm summarized in Algorithm

1 of

Section 3.2.2:

- (1)

Keyword Extraction and Importance Estimation: First,

K candidate keywords are extracted from the input sentence using an external tool (detailed in

Section 3.3). For each candidate keyword

, we mask it individually, feed the masked sentence

into the current model

M, and calculate the cross-entropy loss

for the model’s prediction of that masked keyword. This loss reflects the difficulty of recovering the word under the current model state:

where

is the model’s predicted probability for token

given the masked context

.

- (2)

Dynamic Mask Selection: Based on the importance losses computed in the previous step, all candidate keywords are ranked. We select the top N words with the highest loss values (empirically set N = 3) as the “semantically critical words” to be masked in this training step.

- (3)

Model Optimization: The selected

N keywords are masked simultaneously to form a new input sentence

.The model is then trained with the standard masked language modeling objective to recover these masked words. The overall loss for this step is the sum of the cross-entropy losses at all masked positions:

where

denotes the

m-th selected keyword. By minimizing

, the model is forced to learn how to infer the semantics of these words by leveraging their complete surrounding context, thereby enhancing its ability to capture deep semantic structures and fine-grained semantic relationships within sentences.

Unlike prior dynamic masking techniques that rely on external resources or predefined heuristics, our strategy is intrinsically self-supervised and model-aware. It directly determines the masking strategy based on the model’s current predictive capability, creating a self-enhancing training process.

| Algorithm 1. Dynamic Masking for Pre-training. |

| Inputs: |

| Sentence sequence: |

| Pre-trained BERT model: M |

| Vocabulary size: V |

| Max keywords per sentence: K = 5 |

| Top keywords to mask: N = 3 |

| Output: |

| Masked sentence: |

| Masking recovery loss: |

| 1 Initialization: Extract keywords: ; Initialize loss list: |

| 2 Calculate masking loss for each keyword: |

| for each keyword in keywords: |

| Generate masked sentence: |

| Forward pass: |

| Compute loss according to Equation (2) |

| Append: |

| end for |

| 3 Select top-N keywords for masking: |

| Sort keywords by loss descending: |

|

|

| Select top-N: top_keywords = sorted_keywords [: N] |

| Generate final masked sentence: |

| for each in : |

| end for |

| 4 Model Training: |

| Forward pass to compute final hidden states (Equations (4) and (5)) |

| Compute scores (Equation (6)) and probability distributions (Equation (7)) for masked positions. |

| Compute total loss according to Equations (2) and (3) |

| Backpropagate and update model parameters: |

| |

3.2.3. Multi-Token Handling and Computational Complexity

In our dynamic masking mechanism, “keywords” are not extracted using external tools. Instead, we simply tokenize the input sentence using the standard BERT WordPiece tokenizer and treat all resulting tokens as candidate keywords. For words that are split into multiple sub-tokens, we compute their importance by averaging the MLM loss across all constituent sub-tokens. During masking, all corresponding sub-tokens are replaced with the [MASK] token, consistent with the original BERT design.

The additional computational overhead of our dynamic masking mechanism stems from the initial importance estimation phase. This pre-computation requires one full forward pass per candidate keyword, which is approximately K times more expensive than a single standard MLM pre-training epoch, where K denotes the average number of keywords evaluated per sentence. In terms of time complexity, in the worst-case scenario, the pre-computation cost scales as O (), where C represents the computational cost of a single forward pass for a standard Masked Language Modeling (MLM) step. On average, given that K is a small, fixed constant (set to 5 in our experiments), the total pre-computation overhead corresponds roughly to the cost of running K additional training epochs over the corpus. However, this cost is incurred only once before the main training phase. When amortized over the entire pre-training process, which typically spans hundreds of epochs, the relative overhead is minimal and often accounts for less than 1% of the total training time. This one-time investment is justified by the significant performance gains demonstrated in our experiments. Moreover, the pre-computation is highly parallelizable and can be efficiently scaled in distributed training environments.

3.3. Domain-Finetuned Pre-Training by Dynamic Masking

This section adopts a complete domain-adaptive pre-training framework that integrates the dynamic masking mechanism. The framework aims to bridge the distribution gap between general-purpose pre-trained models and downstream domain-specific semantic matching tasks by leveraging unlabeled text from the target domain through task-oriented pre-training.

3.3.1. Framework Overview and Training Procedure

Our framework is based on a Transformer encoder and adopts a sentence-pair-based pre-training paradigm. For a given sentence pair (

), we apply the dynamic masking mechanism described in

Section 3.2 separately to obtain the masked sentence pair (

).

The forward propagation of the model follows the standard Transformer architecture. Let

denote the hidden vector at position

t in layer

l (

d is the hidden layer dimension), its computation involves multi-head attention and a feed-forward network (FFN):

After L layers of encoding, we obtain the final hidden state sequence .

For a masked position

t, we compute its score distribution over the entire vocabulary V through an output layer:

where

is the weight matrix and

is the bias term. The probability distribution is then obtained via the softmax function:

Here, is the score corresponding to the target word . The final masked language modeling loss is the sum of the negative log-likelihoods at all masked positions (corresponding to the selected N keywords), as defined in Equation (3).

The complete pre-training algorithm flow, which systematically integrates all the above computational steps, is summarized in Algorithm 1.

3.3.2. Hyperparameters and Implementation Details

Candidate Token Processing: We tokenize input sentences using the same BERT WordPiece tokenizer as the model, and each resulting token is treated as a candidate masking unit. For words composed of multiple sub-words, their masking importance loss is computed via Equation (3) (i.e., summing the prediction losses across all sub-word tokens).

Dynamic Masking Parameters: Maximum candidate keywords per sentence, K = 5, number of finally masked keywords, N = 3.

Model Training: The AdamW optimizer is used with a learning rate of and a batch size of 256. The maximum sequence length is limited to 128 tokens.

Computational Cost: The introduction of the dynamic masking mechanism increases the total training time by approximately 15–20% compared to the static random masking baseline.

3.4. Transfer Training by Contrastive Learning

To address the representation collapse problem in sentence embeddings generated by BERT, this paper adopts a transfer training strategy based on contrastive learning [

10]. The core idea is to learn discriminative representations by pulling positive pairs (semantically similar inputs) together and pushing negative pairs (semantically dissimilar inputs) apart in the embedding space. Specifically, we use naturally occurring, semantically parallel sentence pairs as the positive pairs. Our negative sampling strategy treats all other augmented samples from different origins within the same training batch as negative examples. This approach ensures that the contrastive signal is derived from authentic semantic equivalences within the domain, thereby refining the representation space for the actual matching task without introducing synthetic noise.

The proposed contrastive Learning framework for sentence representation learning is built upon a contrastive learning paradigm. These sentences are then passed through a shared BERT encoder, followed by an average pooling layer, to produce fixed-dimensional sentence embeddings.

To guide representation learning, a contrastive loss layer is introduced. This layer is designed to maximize the similarity between embeddings of the two augmented views of the same sentence (positive pairs), while minimizing similarity to embeddings of other sentences in the batch (negative pairs).

During the training process, a batch of text is first extracted from the dataset

D, with a batch size of

N = 256. Each sample is augmented into two versions by the data augmentation module, resulting in a total of 2

N samples. These 2

N samples are then encoded by a shared BERT encoder and processed through an average pooling layer to generate 2

N sentence vectors. The model was trained for 10 epochs using the AdamW optimizer with a learning rate of 2e-5 and a linear warm-up schedule over the first 10% of training steps. Finally, the model is fine-tuned using the NT-Xent loss function, identical to that used in SimCLR.

Here, the function represents the cosine similarity function, r denotes the corresponding sentence vector, and τ is a temperature parameter, set to 0.1 in the experiments. Intuitively, the loss function ensures that each sample within a batch identifies its corresponding augmented version, while the other 2N-2 samples serve as negative samples. The optimization aims to maximize the consistency between the two augmented versions of the same sample in the representation space, while maximizing the distance to the negative samples within the batch.

4. Experiments

4.1. Datasets

This study utilizes the LES Cup dataset [

31], a large-scale Chinese reading comprehension corpus tailored to military application scenarios. The dataset comprises approximately 100,000 annotated passages, each accompanied by a question and five candidate articles. Notably, substantial grammatical and syntactic discrepancies exist between the questions and the evidence sentences, which inherently increases the difficulty of semantic matching. To comprehensively evaluate the model’s semantic matching performance across distinct domains, we construct three domain-specific evaluation subsets: maritime, ground, and airspace. The maritime and airspace subsets each contain 8 entity types, while the ground subset contains 4, totaling 20 distinct entity types. For each entity type, we compile tens to hundreds of descriptive textual instances, ensuring diversity and within-domain variability. To reflect real-world complexity, we intentionally allow cross-domain ambiguity. For example, the same codename (such as

“猎鹰 (Falcon)”) may refer to different entities across domains. For model adaptation, we conduct domain-specific fine-tuning based on the LES corpus. Specifically, we construct a structured training set consisting of synthetic “codename: formal name” pairs (e.g., using person, place, or animal names as codenames) for contrastive learning. Crucially, there is no data leakage: the contrastive learning phase uses only these constructed pairs, while evaluation is performed solely on a consolidated evaluation dataset comprising all three subsets, using held-out descriptive passages that are never exposed during training. All texts were normalized and preprocessed to form a coherent private-domain text base.

4.2. Comparison with Baseline Models

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the proposed model in semantic matching tasks, we selected two representative and state-of-the-art baseline models for comparative experiments. These models demonstrate outstanding capabilities, in general, for semantic embedding and Chinese semantic similarity tasks, providing robust performance benchmarks for this study.

Sentence-BERT (SBERT) [

25]: As a widely employed sentence embedding generation model, SBERT is derived from BERT through fine-tuning using a twin network architecture, specifically designed to compute semantic similarity between sentences. It has become one of the standard benchmarks for semantic text similarity (STS) tasks, exhibiting strong generalization capabilities and stability. We selected SBERT as a robust baseline for general semantic matching.

Text2vec [

26]: This is a state-of-the-art model optimized for Chinese semantic similarity tasks, pre-trained and fine-tuned on large-scale Chinese corpora. It demonstrates outstanding performance across multiple Chinese semantic matching evaluations. Given its specific optimization for Chinese linguistic characteristics, Text2vec serves as an ideal comparison model for assessing semantic matching performance within the Chinese domain.

4.3. Experimental Setup

The model was implemented in PyTorch 1.11 and Hugging Face Transformers. We employed a batch size of 256, utilized an AdamW optimizer with a learning rate of 2 × 10−5 and trained for 10 epochs. The maximum sequence length was set to 128 tokens. All experiments were conducted on high-performance computing nodes equipped with NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 GPUs (24GB VRAM).

4.4. Homogeneous Text Results

4.4.1. Semantic Similarity Results Before and After Private Domain Training

Table 1 presents the semantic similarity among entities within the Maritime Subset, Ground Subset, and Airspace Subset, respectively, computed using different models before and after private domain training.

This table compares the performance of the proposed model against SBERT [

32] and Text2vec [

33] in measuring semantic similarity among same-class entities. The results indicate that private domain training leads to a notable improvement in semantic similarity across all models. However, the proposed model consistently outperforms both baselines across all three categories. Aggregated results show that our model achieves the highest average similarity score, demonstrating its superior capability for semantic matching following private domain training. Further analysis reveals that the proposed model produces more compact and semantically coherent embedding clusters, attributable to the synergistic effect of dynamic masking and contrastive learning. However, performance remains limited on entities with polysemous expressions, suggesting the need for enhanced semantic disambiguation in future work.

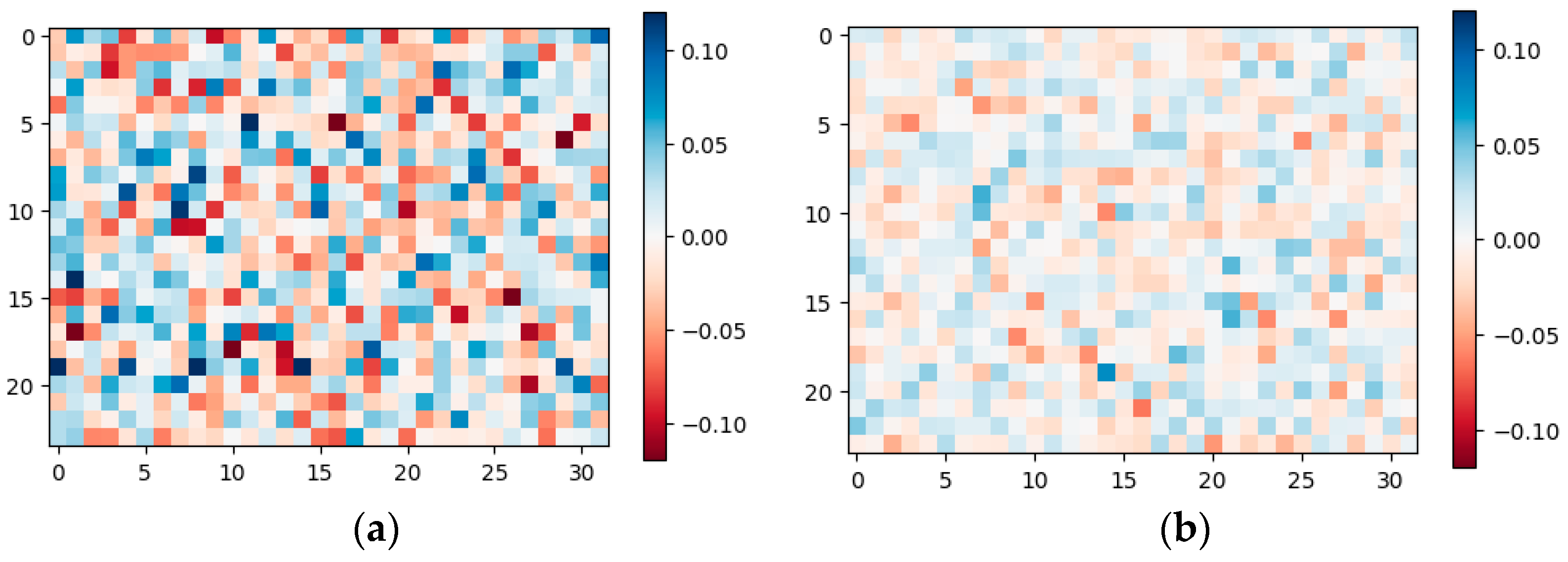

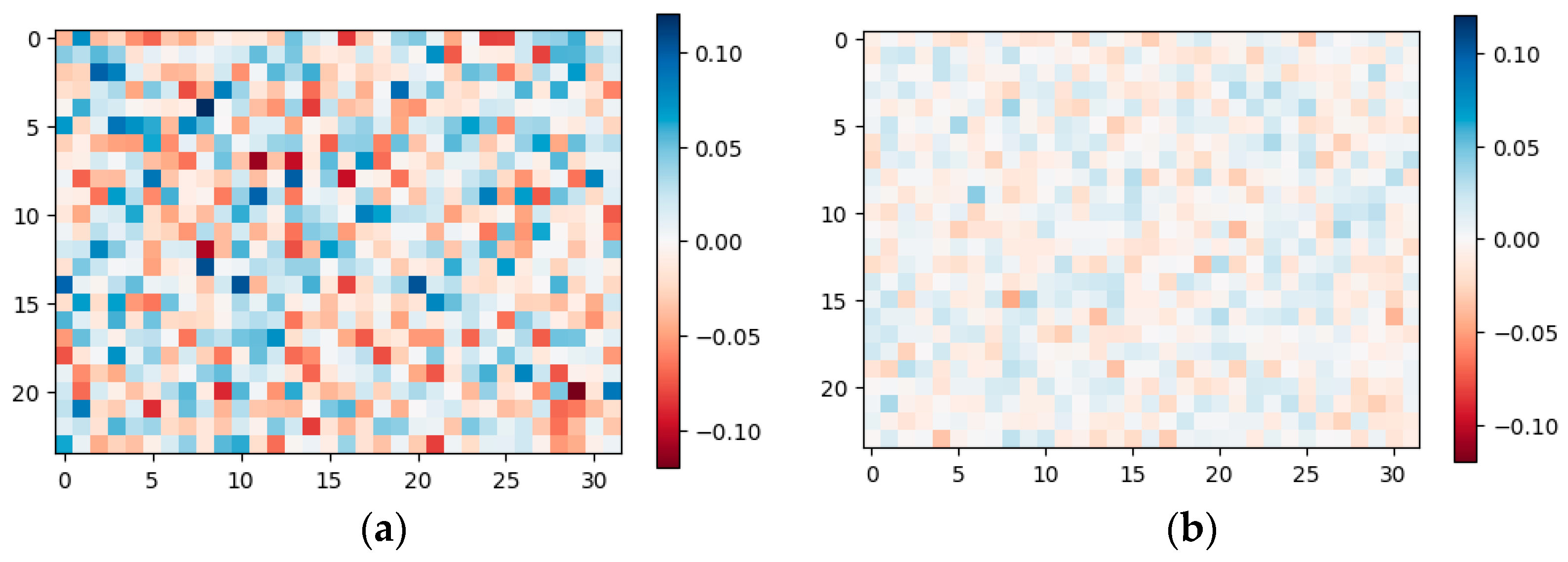

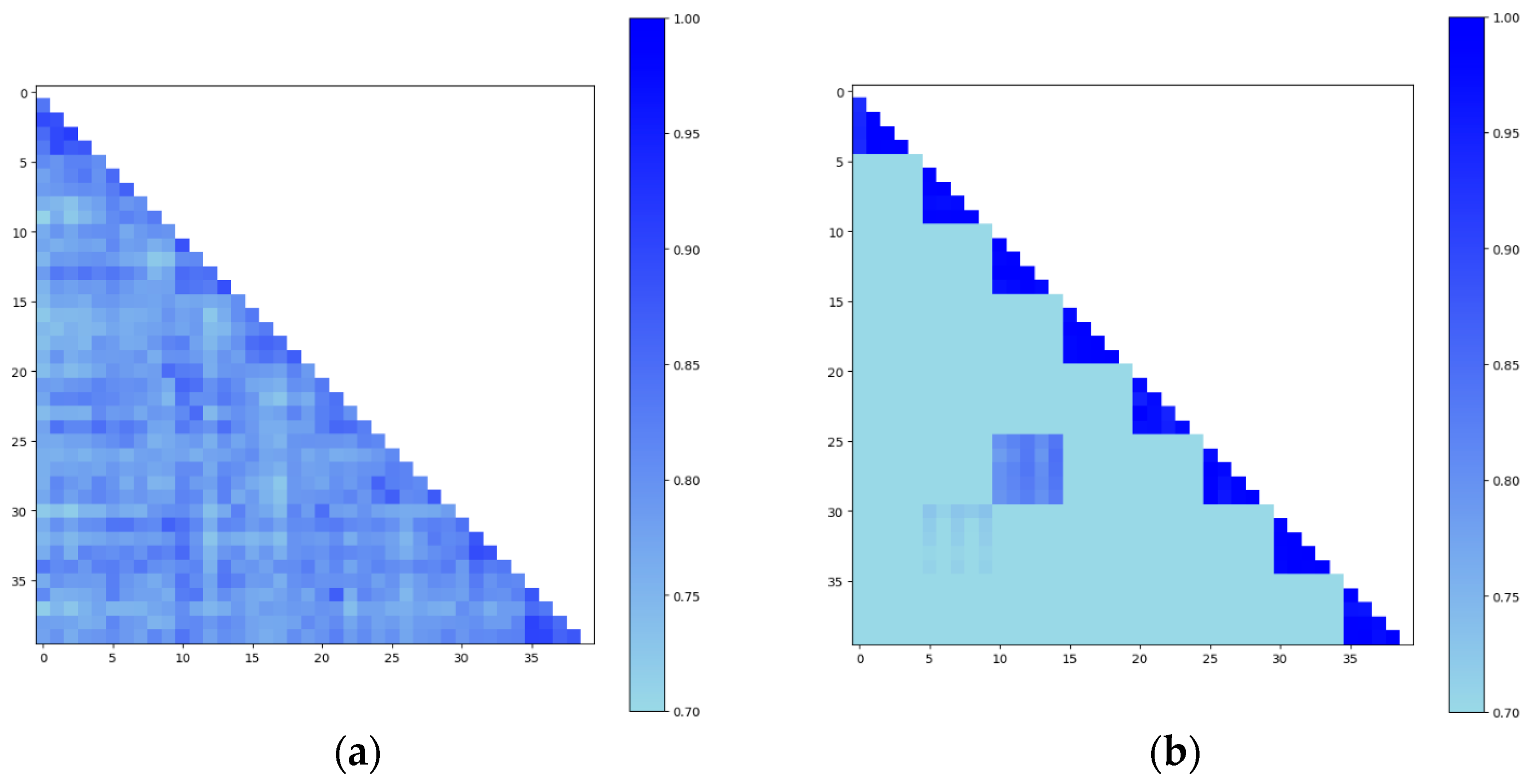

4.4.2. Vector Difference Results Before and After Private Domain Training

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 depict the 2D heat maps of mean vector differences generated by each model before and after private domain training. In these visualizations, positive differences are shown in red and negative differences in blue, with darker shades indicating larger absolute values. For each semantic similarity calculation, entities were divided into two groups: Object One: four identical instances of a given entity. Object Two: the remaining four different entities from the same group. Mean vectors were computed for each object group and differenced to form the basis of the heat maps.

- (1)

Before private domain training (

Figure 2a), the heat map shows darker regions, indicating greater differences between entity vectors and lower similarity. After training (

Figure 2b), the colors lighten, suggesting that private domain training reduces vector differences and improves semantic similarity.

To provide a rigorous quantitative interpretation of the visual trends in the heatmaps, we computed the Mean Absolute Difference (MAD) metric based on vector differences across entity types. As a strong baseline for general-purpose semantic matching, the SBERT model exhibited a decrease in MAD from 0.036 to 0.021 after private domain training, corresponding to a 41.7% reduction. Although its representation space shows some degree of convergence post-training, the modest improvement suggests that SBERT’s capacity for optimizing fine-grained semantic representations in specialized domain tasks remains limited.

- (2)

Similarly,

Figure 3a (pre-training) shows darker areas, reflecting poor alignment between entity representations. Post-training (

Figure 3b), the colors lighten slightly, but some regions remain dark, indicating persistent differences in certain entity pairs.

For Text2Vec, which is a model specifically optimized for Chinese semantic similarity tasks, the MAD decreased from 0.042 to 0.015 after domain adaptation, reflecting a 64.3% reduction. While this demonstrates a certain level of adaptability in Chinese-domain scenarios, its ability to unify and refine the semantic representation space still falls short of achieving high cohesion across diverse entity types.

- (3)

Figure 4b, showing post-training results for our model, displays significantly lighter and more uniform coloration than

Figure 2b and

Figure 3b. This implies a substantial reduction in mean vector differences and improved text similarity across all entity types.

In contrast, our proposed model achieves a substantially greater reduction: the MAD drops from 0.031 before training to 0.011 after private domain training, representing a 64.5% improvement. This significant decline quantitatively confirms that, through the synergistic integration of dynamic masking and contrastive learning, our framework effectively pulls the semantic representations of different entity types closer together while preserving discriminability. The result is a markedly more cohesive and structured semantic space, underscoring the superiority of our approach in domain-specific semantic matching.

A direct comparison of the experiment results reveals that our model achieves the most pronounced improvement, effectively reducing inter-entity variation and enhancing same-class similarity. These results validate the effectiveness of our private domain training strategy in refining domain-specific semantic representations.

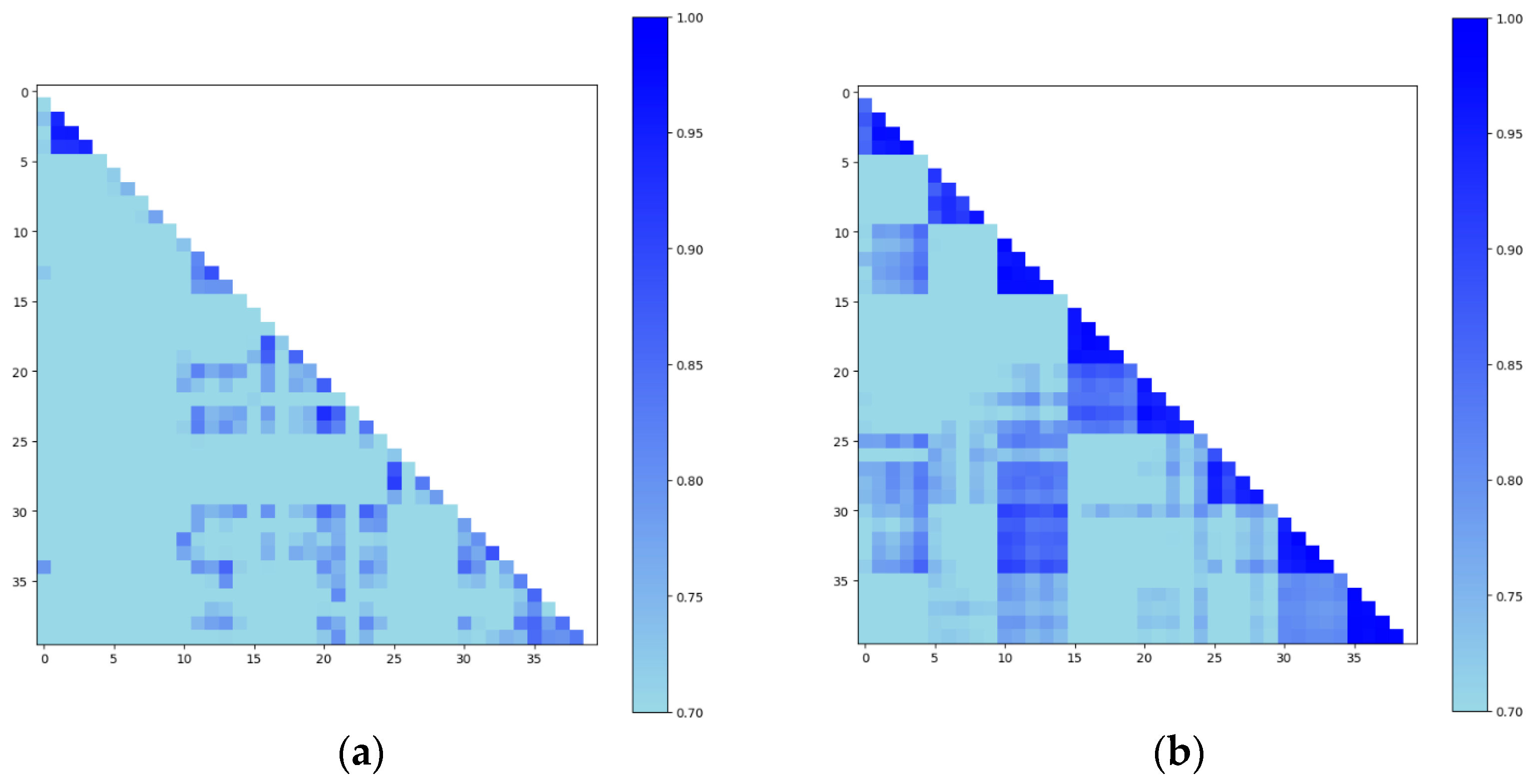

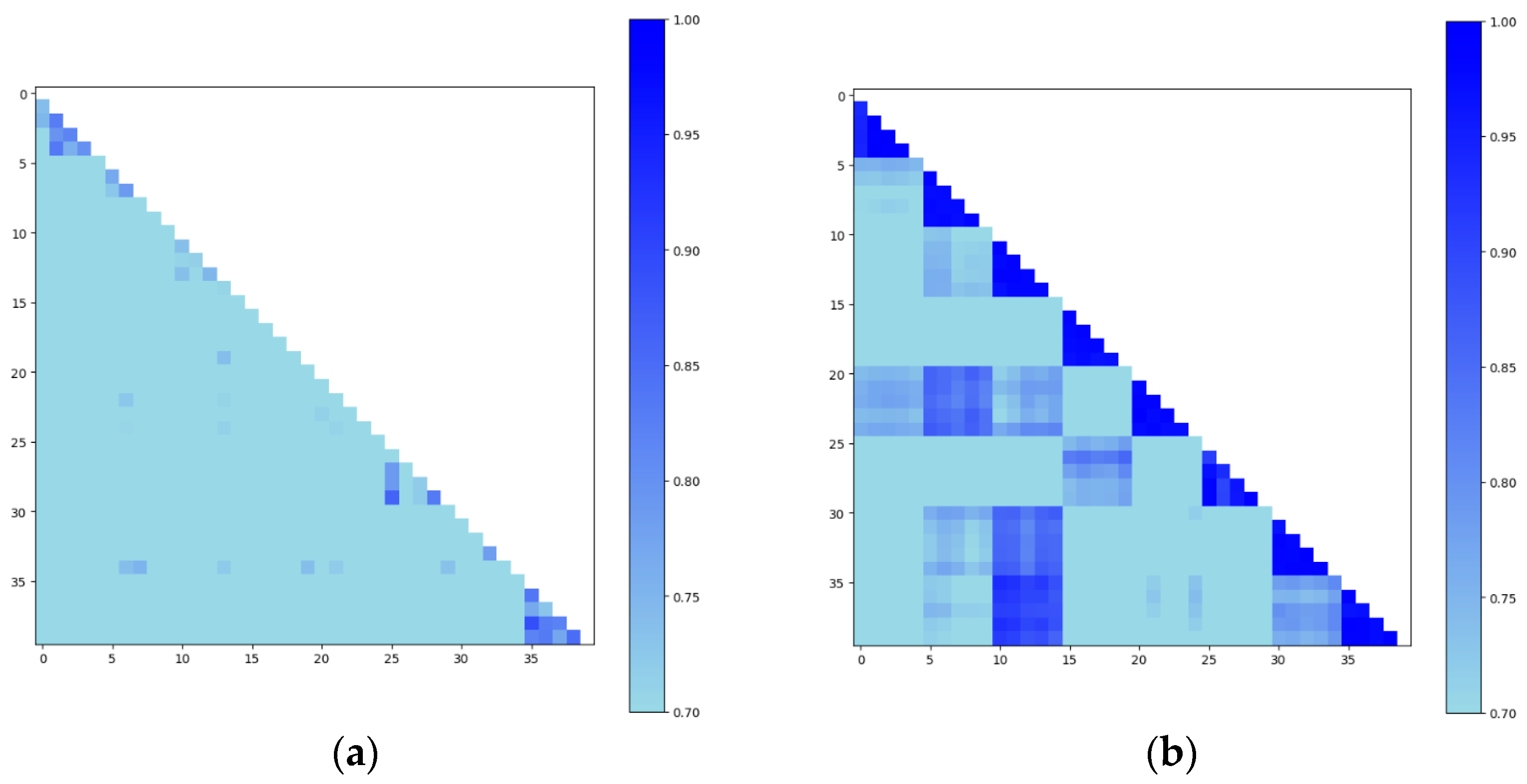

4.4.3. Confusion Matrix of Similarity Before and After Private Domain Training

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 present the 2D heat maps of similarity scores between entities of the same class, computed by the SBERT, Text2vec, and our model, before and after private domain training. In each heat map, the shades of blue represent cosine similarity values in the range of 0.7 to 1.0, with darker shades indicating higher similarity. Each matrix is divided into triangular regions: The lower right triangles (along the diagonal) correspond to similarity scores between entities within the same class; The off-diagonal regions represent similarity scores between entities from different classes.

- (1)

Before private domain training (

Figure 5a), the diagonal similarity scores are unevenly distributed. While some regions show darker shades (indicating high intra-class similarity), others are relatively light, revealing inconsistencies in modeling same-class semantics.

After private domain training (

Figure 5b), the diagonal becomes more uniformly dark, reflecting improved intra-class similarity. However, several darkened points also emerge in off-diagonal areas, suggesting increased similarity across different classes, which may introduce semantic interference in classification or retrieval tasks.

- (2)

The similarity pattern of Text2vec (

Figure 6a) is similar to SBERT: uneven diagonal similarity scores prior to training. After private domain training (

Figure 6b), diagonal values improve moderately, as indicated by deeper blue shades. However, residual dark spots in non-diagonal areas remain, suggesting elevated cross-class similarity, which can adversely affect semantic matching precision.

- (3)

Figure 7a shows the similarity heat map of our model before training. Although some diagonal elements are already darker than the baselines, the overall distribution is less concentrated, and non-diagonal regions still exhibit moderate similarity levels.

After private domain training (

Figure 7b), the diagonal becomes significantly darker, indicating a strong improvement in modeling semantic similarity among same-class entities. Simultaneously, the non-diagonal regions become lighter, demonstrating reduced similarity between different classes. This pattern is more distinct and consistent than in SBERT and Text2vec, showcasing the model’s superior ability to differentiate between intra- and inter-class relationships.

The dynamic token masking strategy enables the model to focus on domain-specific semantic units during pre-training, thereby capturing more relevant features for entity representation. More importantly, the integration of contrastive learning establishes an optimized geometric structure in the vector space, where similar entities are clustered more closely while dissimilar ones are effectively separated. This geometric optimization manifests visually as the distinctive pattern of darkened diagonals and lightened off-diagonals in the heat map.

4.5. Heterogeneous Text Results

4.5.1. Semantic Matching Results for Original Entities

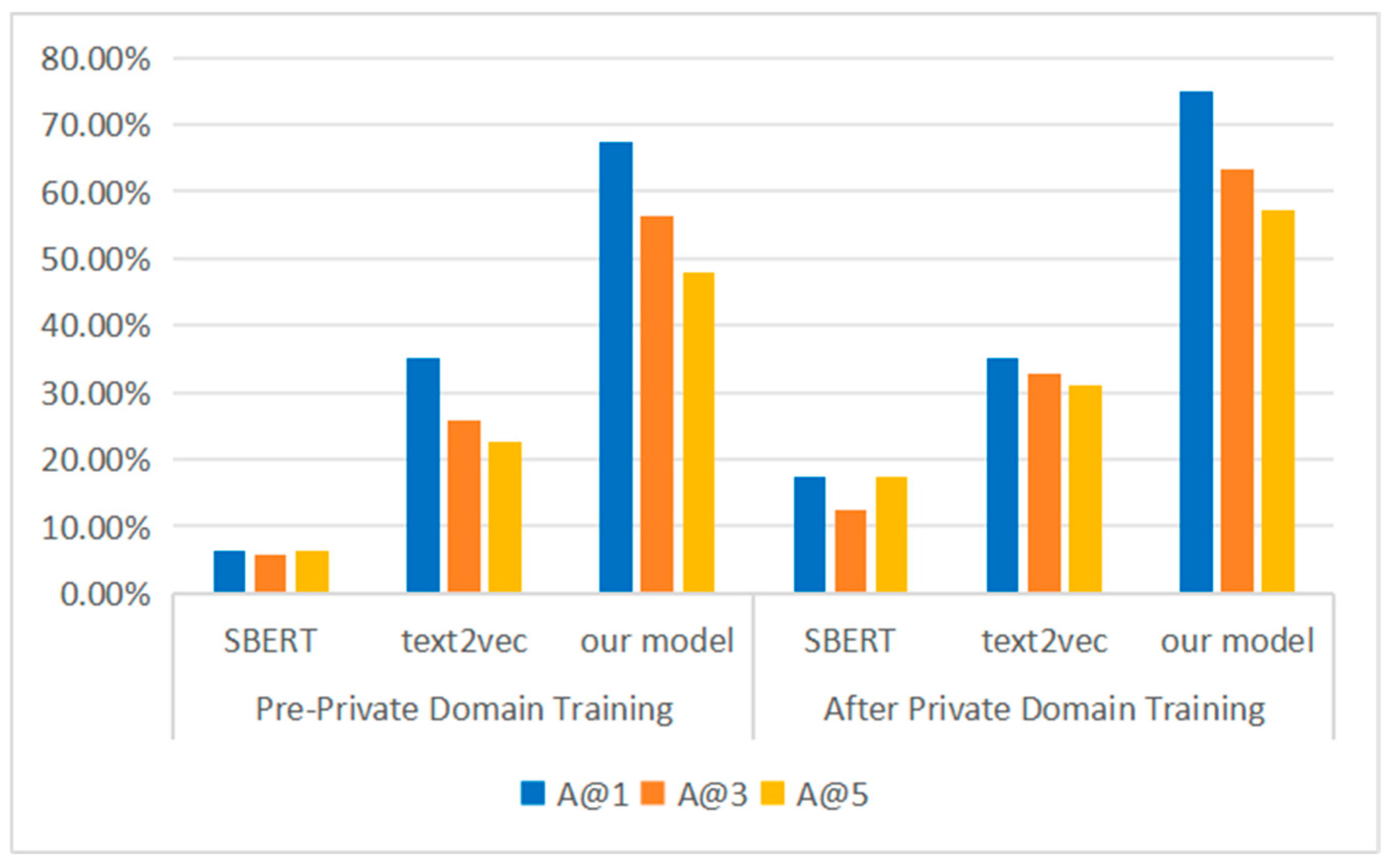

Figure 8 reports the semantic matching accuracy for original entities on heterogeneous text, evaluated using A@1, A@3, and A@5, which represent top-1, top-3, and top-5 retrieval accuracy.

For the SBERT model, all accuracy metrics improve after private domain training. However, the absolute performance remains low, suggesting limited effectiveness in domain-specific heterogeneous scenarios. The Text2vec model exhibits a slight increase in A@3 and A@5 after training, but overall gains are minimal.

In contrast, the proposed model demonstrates significant improvements across all metrics. After private domain training, A@1, A@3, and A@5 all exceed 50%, with each increasing by at least 7 percentage points over the pre-training baseline. These results indicate that the model is more effective in aligning semantic representations with task-specific retrieval goals, outperforming both baselines consistently.

4.5.2. Ablation Study on Contrastive Learning Module

To further verify the impact of different components and fine-tuning strategies within the proposed contrastive learning module on model performance, we conducted an ablation study. The results are presented in

Table 2. The experiment compares the semantic matching performance (evaluated on homogeneous textual pairs) under four settings:

The results show that compared to the no-fine-tuning baseline, fine-tuning only the bias parameters did not lead to performance improvements, indicating that adjusting bias terms alone is insufficient to effectively optimize the semantic representation space. Fine-tuning only the attention parameters yielded significant improvements, with increases of 4.2%, 4.8%, and 7.8% in A@1, A@3, and A@5, respectively. This demonstrates that optimizing the attention mechanism effectively enhances the model’s ability to represent different semantic relationships in sentences. However, the best performance was achieved with the full parameter fine-tuning strategy, which attained the highest scores across all metrics, particularly showing a 9.5% improvement in A@5 over the baseline. This validates that our complete contrastive learning framework, which involves collaboratively optimizing components such as the attention mechanism and projection heads, is crucial for learning discriminative sentence embeddings. By explicitly pulling positive pairs closer and pushing negative pairs apart, it effectively mitigates the “representation collapse” issue in BERT sentence vectors, thereby significantly improving the accuracy of semantic matching.

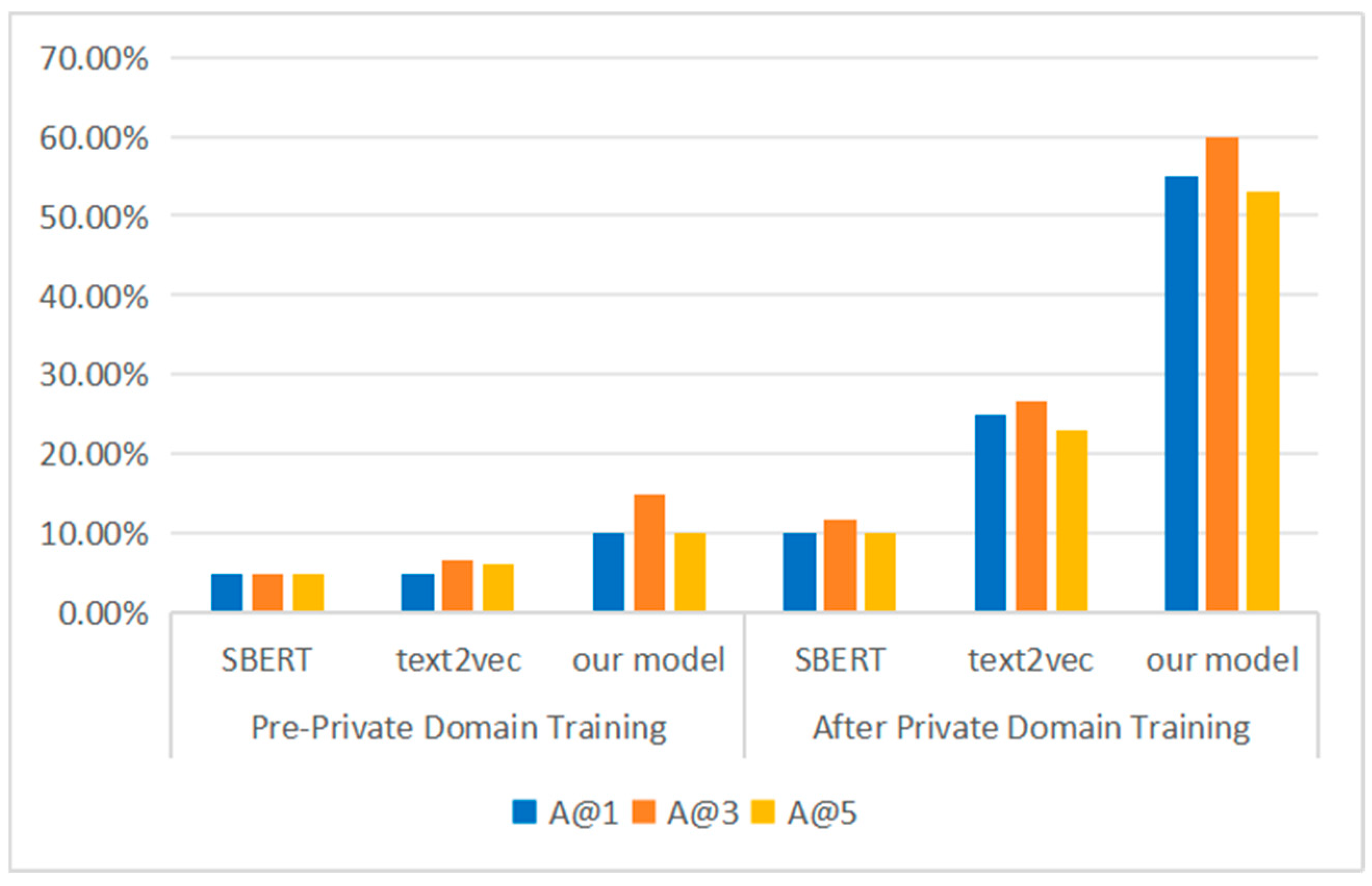

4.5.3. Semantic Matching Results for New Entities

Figure 9 presents the semantic matching results for newly added entities, using the same evaluation metrics: A@1, A@3, and A@5. To rigorously assess generalization to unseen entities, all texts describing the query entities were deliberately excluded from the retrieval corpus, leaving only texts describing other entities within the same category. Consequently, before domain-specific fine-tuning, the models had never learned the similarity relationships between different entities of the same category, which explains the initially low baseline accuracy.

Post-training improvements are observed for both SBERT and Text2vec. However, their accuracy remains suboptimal, failing to surpass the 50% threshold across all evaluation points. In contrast, our model achieves marked improvements, with each metric (A@1, A@3, A@5) increasing by at least 40 percentage points compared to pre-training values. Furthermore, all accuracy scores exceed 50%, confirming the model’s strong generalization capability to previously unseen entities. The substantial relative gain reflects the model’s successful acquisition of category-level semantic relationships through dynamic masking and contrastive learning, rather than mere memorization of seen examples. These findings underscore the robustness of the proposed framework in low-resource, domain-finetuned retrieval scenarios.

4.6. Case Study Results

4.6.1. Case Studies: Semantic Matching of Homogeneous Textual Pairs

This paper demonstrates the effectiveness of the proposed method across different semantic scenarios through both homogeneous and heterogeneous text matching cases. In the homogeneous case (

Table 3), the query “USS New Mexico battleship” and the candidate “Battleship USS New Mexico” achieve a perfect similarity score of 1.00 with a relevance label of 2, confirming their strong semantic equivalence. Other battleship candidates (“USS Pennsylvania” and “USS Missouri”) with a label of 1 obtain high similarity scores of 0.92 and 0.91, respectively, demonstrating precise alignment for entities of the same category. In contrast, the unrelated “USS Chicago cruiser” is correctly assigned a low similarity of 0.75 and a label of 0.

4.6.2. Case Studies: Semantic Matching Across Heterogeneous Textual Sources

In the heterogeneous case (

Table 4), the query “USS New Mexico battleship saw extensive service in numerous conflicts” is matched against descriptive paragraphs. The most relevant candidate, describing New Mexico’s veteran status in two world wars, receives a label of 2.0 and a high similarity of 0.88. Other battleship descriptions (“USS Pennsylvania” and “USS Missouri”) with a label of 1.0 achieve similarities of 0.82 and 0.80, maintaining strong alignment despite structural variations. Meanwhile, the description of “USS Chicago cruiser” with a label of 0.0 obtains the lowest similarity score of 0.71, demonstrating the model’s capability to effectively distinguish irrelevant content in complex textual contexts.

These results confirm that the dynamic masking strategy successfully enhances focus on domain-critical information while filtering weakly relevant content. Combined with contrastive learning, which improves representation discrimination and mitigates sentence vector collapse, the model achieves robust performance across both homogeneous and heterogeneous matching tasks. The synergy between these components enables comprehensive improvement in semantic understanding and cross-scenario generalization.

4.6.3. Error Analysis

To better understand the failure modes and limitations of our model, we conduct a qualitative error analysis on a representative subset of misclassified instances. Our investigation reveals that the primary source of systematic confusion arises when the same codename refers to semantically distinct entities across different operational sub-domains. This cross-domain semantic ambiguity represents a fundamental challenge in codename resolution, as surface forms alone are insufficient to disambiguate referents without explicit contextual grounding. Notably, our domain-specific fine-tuning framework, leveraging dynamic masking and contrastive learning, effectively alleviates this issue. By encouraging the model to learn distinct contextual representations for codenames within each sub-domain (maritime, ground, airspace), our approach significantly reduces cross-domain misinterpretations.

5. Discussion

In summary, the proposed model exhibits superior performance across all evaluation dimensions, highlighting its effectiveness in private domain semantic matching tasks and its strong potential for deployment in specialized, low-supervision NLP applications. This paper systematically evaluates a semantic matching model that incorporates dynamic masking and contrastive learning, using a private domain text base and structured knowledge samples. Experimental results confirm that the proposed model significantly improves semantic representation in specialized domains. The performance gains stem from the synergistic effect between dynamic masking and contrastive learning: the former acts as a semantic salience enhancer by forcing the model to focus on pivotal tokens, while the latter serves as a representation regularizer that explicitly structures the embedding space. This dual mechanism effectively mitigates both embedding collapse and semantic dispersion. However, some limitations persist. The dynamic masking strategy relies on heuristic significance estimation that may not fully capture contextual semantic importance. The contrastive learning component remains vulnerable to uninformative negative samples in data-scarce scenarios. Furthermore, the model’s cross-domain transfer capability requires further verification, as its performance depends on the availability of representative domain-specific corpora.

In summary, the proposed framework provides an effective solution for domain-finetuned semantic matching, though future work should address its limitations through learnable masking policies and more robust negative sampling strategies.

6. Conclusions

This paper presents a novel domain-finetuned semantic matching model that introduces a synergistic integration of a fully self-supervised dynamic masking mechanism and a domain-grounded contrastive learning strategy. This integration addresses key limitations of traditional pre-training approaches in sentence-level semantic matching tasks. Existing models often struggle to effectively model semantic alignment due to static, random masking strategies and the “representation collapse” phenomenon, in which sentence embeddings are compressed into a narrow region of the vector space, thereby limiting discriminative capacity.

To overcome these issues, we employ sentence-pair-based pre-training aligned with the target task distribution and introduce a self-supervised dynamic masking mechanism that adaptively identifies and masks the most semantically critical keywords based on the model’s own recovery difficulty. Furthermore, a contrastive learning framework that utilizes naturally occurring, semantically equivalent sentence pairs from the target domain is incorporated to refine sentence representations using only a small amount of unlabeled data, thereby preserving domain-specific semantic integrity and significantly improving the model’s adaptability to downstream matching tasks. Experimental results demonstrate that private domain training substantially improves the model’s semantic understanding ability, particularly in domain-specific and heterogeneous text matching scenarios. Compared to strong baselines such as SBERT and Text2vec, our model achieves superior performance in both similarity-based and retrieval-based evaluations, confirming its effectiveness in low-resource, domain-sensitive environments.

However, the interaction between our two core components introduces a subtle exposure bias. During the dynamic masking pre-training phase, the model learns to construct representations under artificially masked input conditions. Yet, at inference time for semantic matching, it processes raw, unmasked sentences. This results in a distribution shift between the training data seen by the encoder and the inference data. Although the subsequent contrastive learning phase, which operates without masking, partially mitigates this gap by directly optimizing the inference-time representation space, a fundamental discrepancy remains. This phenomenon bears similarity to, yet is distinct from, the exposure bias known in sequence-to-sequence models [

27]. Future work could explicitly address this limitation by exploring more effective bridging techniques, such as employing imitation learning methods from model distillation as proposed by Pozzi et al. [

27], or adopting a curriculum learning approach to gradually reduce the masking rate during pre-training.

This paper adopts a novel domain-finetuned semantic matching framework that overcomes the limitations of traditional methods through its context-aware masking and authentic-pair contrastive learning. Additionally, while the model exhibits strong performance within the evaluated domains, its cross-domain generalization capability warrants further investigation. In future work, we plan to explore more sophisticated dynamic masking algorithms that better identify and encode sentence-level semantic salience. We also aim to extend the model’s application to a broader range of downstream tasks and domain settings, providing a more comprehensive assessment of its generalization capacity. Moreover, better methods for constructing pre-training corpora and more efficient sentence modeling techniques could be investigated. For example, pre-training could be conducted using more diverse sentence pairs, and enhanced pre-trained models could be utilized to directly extract key information from sentences. These approaches aim to further improve the model’s semantic matching capabilities and its ability to effectively model key information for downstream tasks. Furthermore, we intend to examine end-to-end construction of pre-training corpora, as well as approaches that leverage pre-trained models to automatically extract key semantic information. Such enhancements may further improve the model’s robustness, transferability, and effectiveness in complex semantic matching applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z. (Yiming Zhang) and C.W.; methodology, Y.Z. (Yiming Zhang); software, Z.Z. and P.L.; formal analysis, P.X. and C.W.; resources, Y.Z. (Yong Zhu); data curation, Y.Z. (Yiming Zhang); writing—original draft preparation, Y.Z. (Yiming Zhang) and C.W.; visualization, Y.Z. (Yiming Zhang); supervision, Y.Z. (Yong Zhu) and C.W.; project administration, Y.Z. (Yong Zhu) and C.W.; funding acquisition, Y.Z. (Yong Zhu) and C.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Key Laboratory of Information System Requirements, China, grant number LHZZ202403.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Naveed, H.; Khan, A.U.; Qiu, S.; Saqib, M.; Anwar, S.; Usman, M.; Akhtar, N.; Barnes, N.; Mian, A. A comprehensive overview of large language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.06435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, F. Research on Text Similarity Measurement Hybrid Algorithm with Term Semantic Information and TF-IDF Method. Adv. Multimed. 2022, 2022, 7923262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yang, Y.; Chen, C.; Zhang, X.; Leng, Q.; Zhao, X. Deep learning-based multimodal emotion recognition from audio, visual, and text modalities: A systematic review of recent advancements and future prospects. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 237, 121692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figuera, P.; García Bringas, P. Revisiting Probabilistic Latent Semantic Analysis: Extensions, Challenges and Insights. Technologies 2024, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, U.; Shah, A. Topic modeling using latent Dirichlet allocation: A survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2021, 54, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirunavukarasu, A.J.; Ting, D.S.J.; Elangovan, K.; Gutierrez, L.; Tan, T.F.; Ting, D.S.W. Large language models in medicine. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 1930–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; Volume 1, pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J.; He, D.; Tan, X.; Qin, T.; Wang, L.; Liu, T.-Y. Representation degeneration problem in training natural language generation models. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.12009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Huang, J.; Huang, K.; Hu, Z.; Wang, G.; Gu, Q. Improving neural language generation with spectrum control. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, New Orleans, LA, USA, 6–9 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y.; Li, R.; Wang, S.; Zhang, F.; Wu, W.; Xu, W. Consert: A contrastive framework for self-supervised sentence representation transfer. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2105.11741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Qiu, C.; Liang, L.; Acuna, D.E. Paraphrase identification with deep learning: A review of datasets and methods. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2212.06933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taye, M.M. Understanding of machine learning with deep learning: Architectures, workflow, applications and future directions. Computers 2023, 12, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalchbrenner, N.; Grefenstette, E.; Blunsom, P. A convolutional neural network for modelling sentences. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1404.2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakhlin, A. Convolutional neural networks for sentence classification. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1408.5882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neculoiu, P.; Versteegh, M.; Rotaru, M. Learning text similarity with siamese recurrent networks. In Proceedings of the 1st Workshop on Representation Learning for NLP, Berlin, Germany, 11 August 2016; pp. 148–157. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, S.; Xu, L.; Liu, K.; Zhao, J. Recurrent convolutional neural networks for text classification. In Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, Austin, TX, USA, 25–30 January 2015; Volume 29. [Google Scholar]

- Bahdanau, D. Neural machine translation by jointly learning to align and translate. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.0473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rush, A.M.; Chopra, S.; Weston, J. A neural attention model for abstractive sentence summarization. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1509.00685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, Z.; Gao, J. Chinese Cyber Threat Intelligence Named Entity Recognition via RoBERTa-wwm-RDCNN-CRF. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2023, 77, 299–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikolov, T. Efficient estimation of word representations in vector space. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1301.3781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Sun, T.; Xu, Y.; Shao, Y.; Dai, N.; Huang, X. Pre-trained models for natural language processing: A survey. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2020, 63, 1872–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Song, C.; Li, D.; Qu, X.; Long, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, H. RoBGP: A Chinese Nested Biomedical Named Entity Recognition Model Based on RoBERTa and Global Pointer. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2024, 78, 3603–3618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Cai, X. A Survey of Text-Matching Techniques. Information 2024, 15, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Xu, J.; Shi, H.; Zhao, H. Enhancing Log Anomaly Detection with Semantic Embedding and Integrated Neural Network Innovations. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2024, 80, 3991–4015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.; Lee, S.; Liu, L.; Choi, W. TA-SBERT: Token attention sentence-BERT for improving sentence representation. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 39119–39128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Jiang, W.; Deng, J.; Ren, Q.; Zhang, L. Constructing Knowledge Graph for Electricity Keywords Based on Large Language Model. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 7th Conference on Energy Internet and Energy System Integration (EI2), Hangzhou, China, 15–18 December 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 4844–4849. [Google Scholar]

- Pozzi, A.; Incremona, A.; Tessera, D.; Toti, D. Mitigating exposure bias in large language model distillation: An imitation learning approach. Neural Comput. Appl. 2025, 37, 12013–12029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimers, N. Sentence-BERT: Sentence Embeddings using Siamese BERT-Networks. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1908.10084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Yousuf, O.; Jin, Z. Improving BERTScore for machine translation evaluation through contrastive learning. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 77739–77749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.; Guo, Z.; He, S.; Liu, K.; Zhao, J.; Liu, S. Dynamic word masking based pre-trained model for sentence matching. J. Chin. Inf. Process. 2021, 35, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://github.com/caishiqing/joint-mrc (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Paganelli, M.; Tiano, D.; Guerra, F. A multi-facet analysis of BERT-based entity matching models. VLDB J. 2024, 33, 1039–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Lu, Q.; Fan, H.; Xiao, Y.; Hu, J.; Zhang, S. Intelligent Security Q&A System Based on Large Language Model. In Proceedings of the 2024 3rd International Conference on Robotics, Artificial Intelligence and Intelligent Control (RAIIC), Mianyang, China, 5–7 July 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 271–275. [Google Scholar]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).