Disposal of Personal Protective Equipment during the COVID-19 Pandemic Is a Challenge for Waste Collection Companies and Society: A Case Study in Poland

Abstract

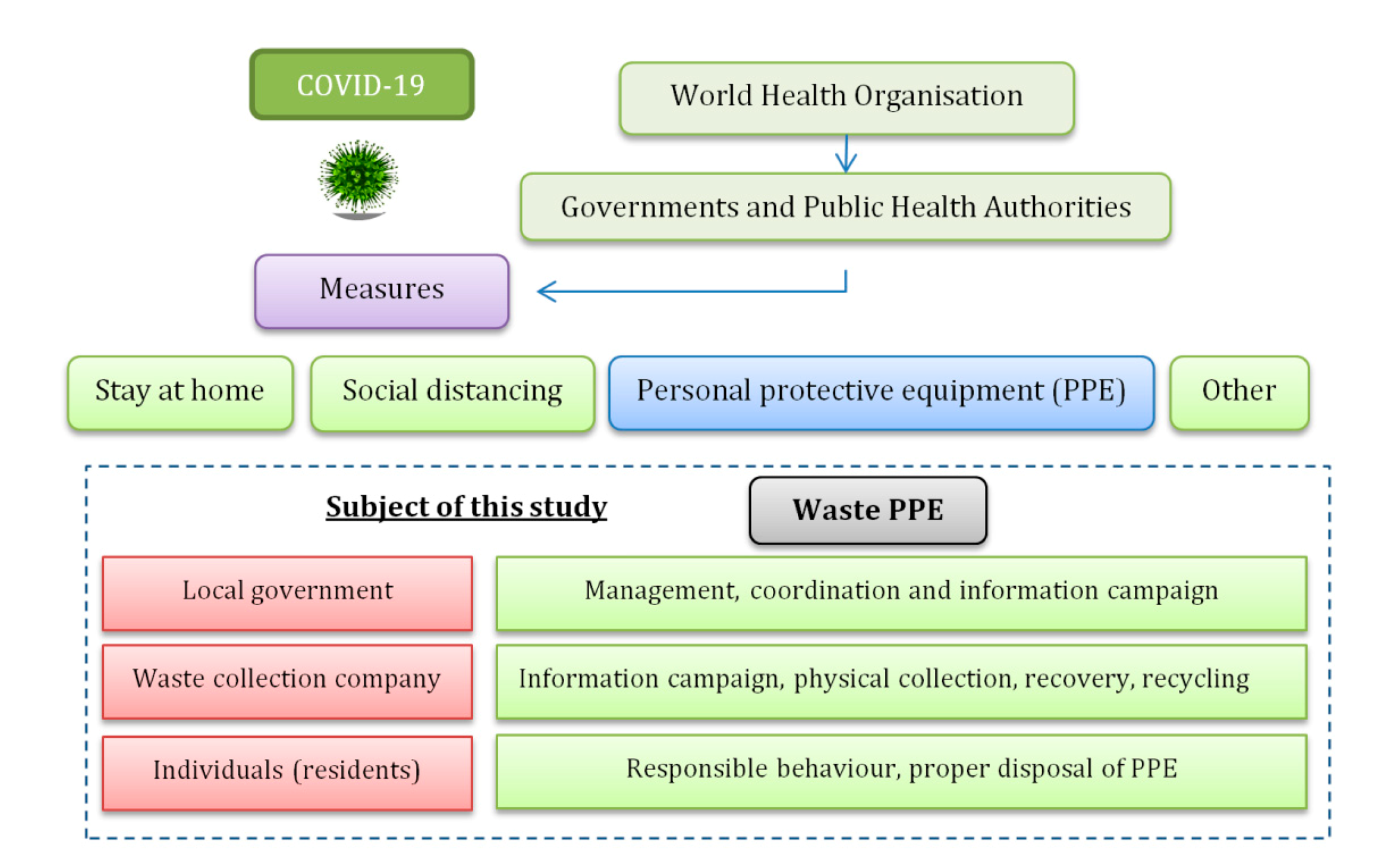

1. Introduction

- providing bags assigned with a “C” label or of a designated color,

- collecting waste at least every seven days,

- providing direct transportation from collection points to the incineration plant or treatment facility for proper treatment of the waste, and

- disinfecting the containers or waste bins.

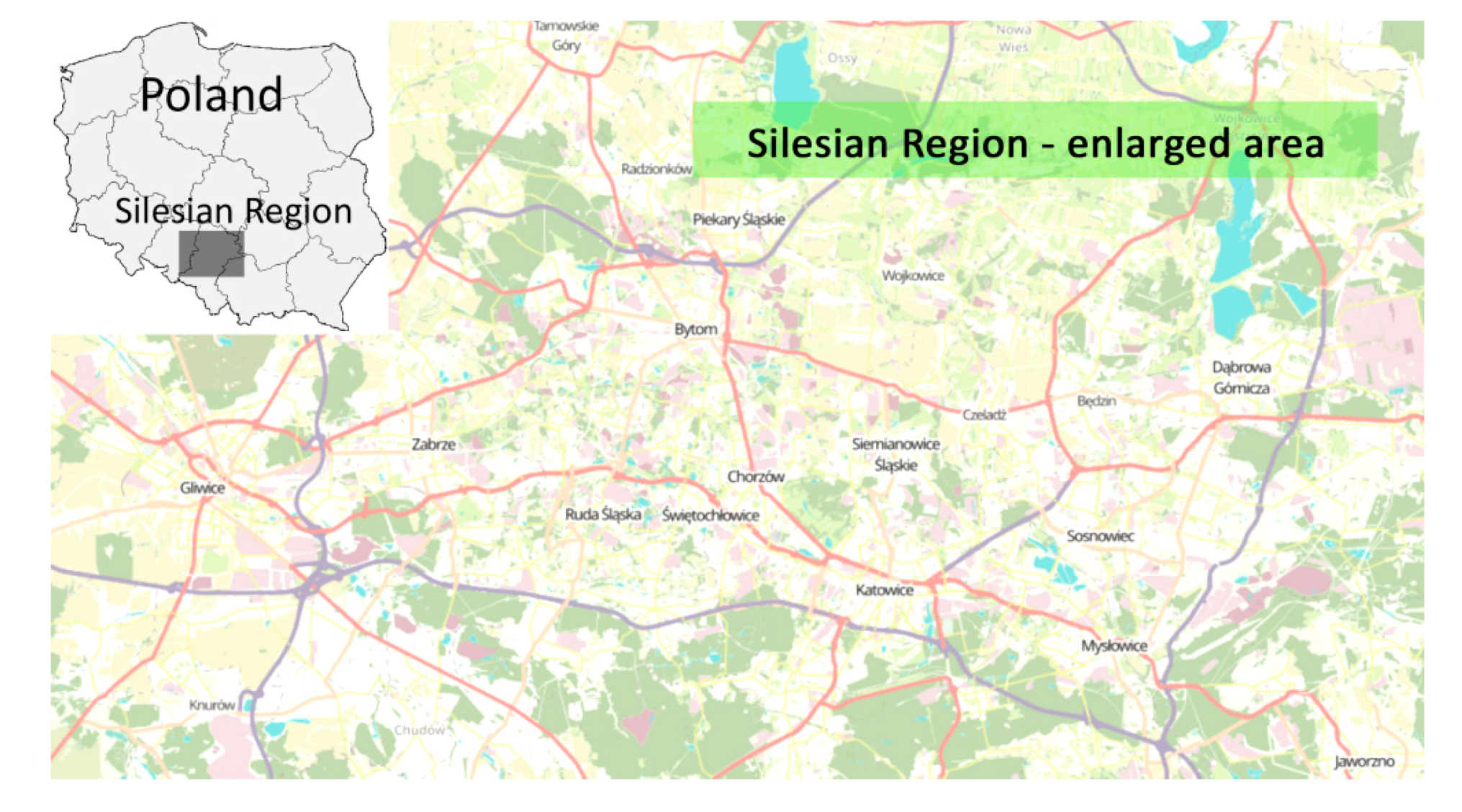

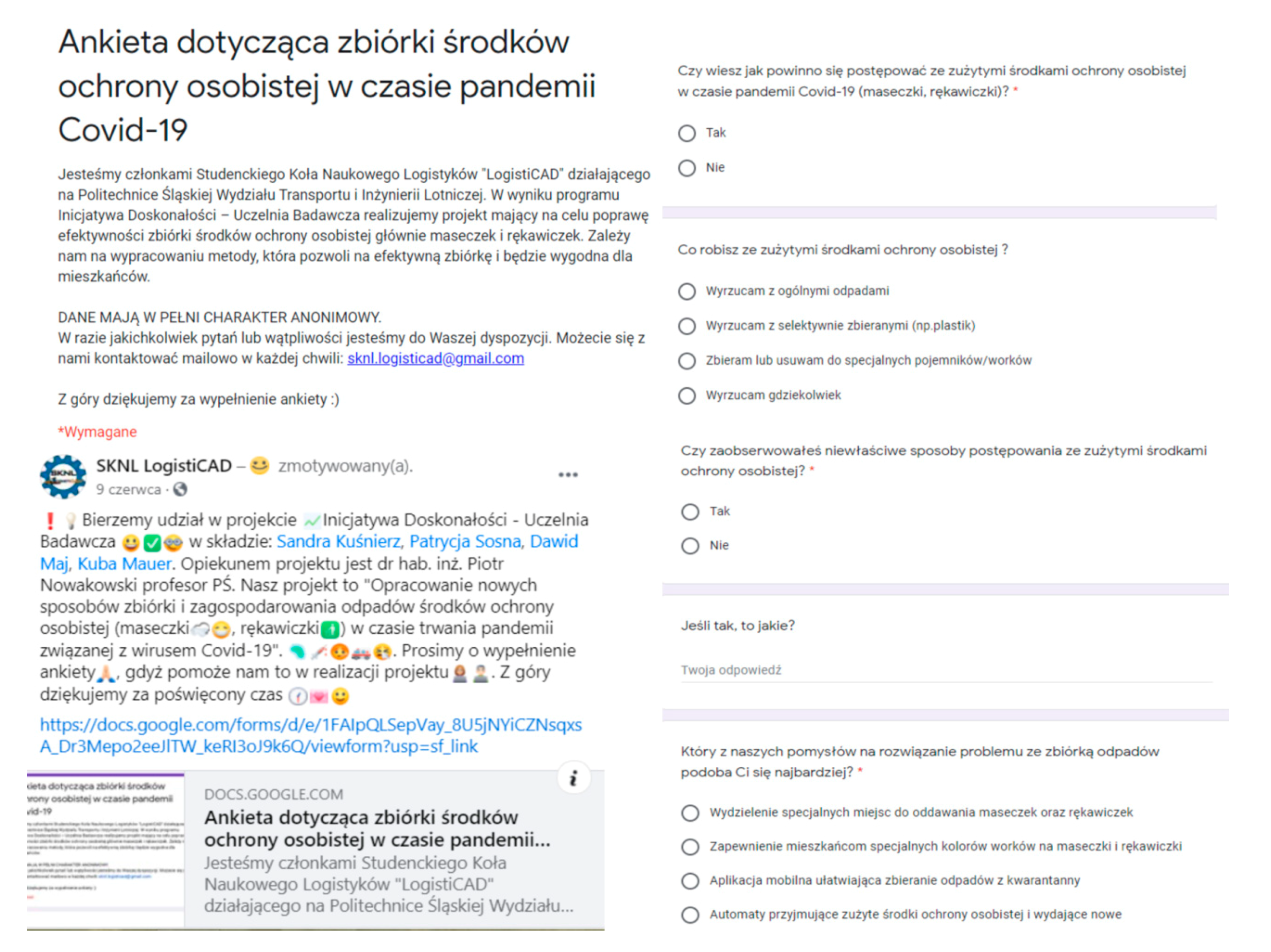

2. Materials and Methods

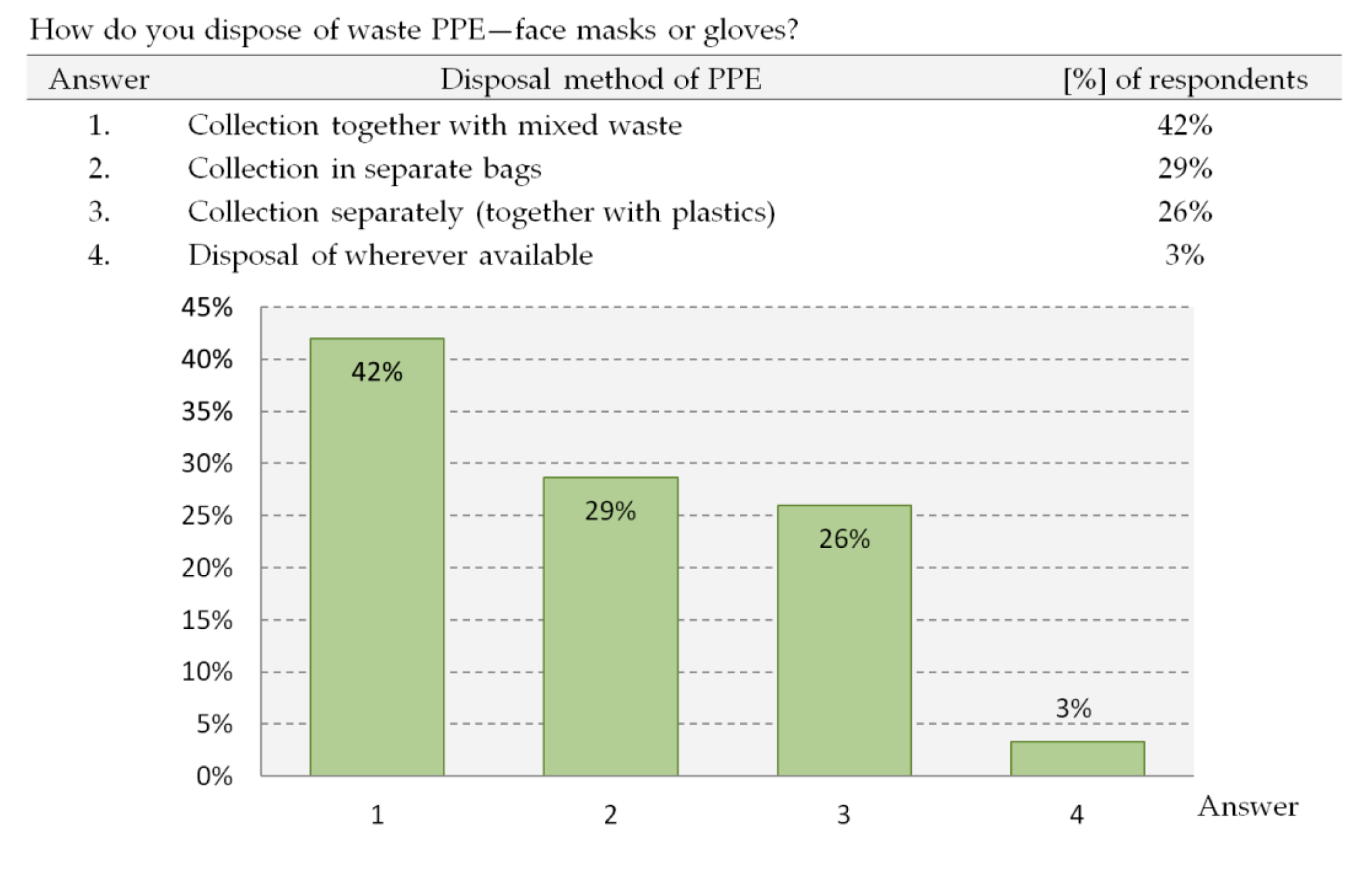

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Time. The WHO Just Declared Coronavirus COVID-19 a Pandemic. Available online: https://time.com/5791661/who-coronavirus-pandemic-declaration/ (accessed on 21 July 2020).

- BBC. The World in Lockdown in Maps and Charts. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-52103747 (accessed on 21 July 2020).

- Kingsland, J.; Widespread Face Mask Use Can Control COVID-19 Outbreak, Study Suggests. Medical News Today, 15 June 2020. Available online: https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/widespread-face-mask-use-can-control-covid-19-outbreak-study-suggests (accessed on 21 July 2020).

- CFR Council of Foreign Relations. Which Countries Are Requiring Face Masks? Available online: https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/which-countries-are-requiring-face-masks (accessed on 10 August 2020).

- WHO World Health Organization. Q&A: Masks and COVID-19. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/q-a-on-covid-19-and-masks (accessed on 11 August 2020).

- WHO World Health Organization. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Advice for the Public: When and How to Use Masks. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public/when-and-how-to-use-masks (accessed on 11 August 2020).

- European Commission. Directive 2008/98/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 November 2008 on Waste and Repealing Certain Directives. EUR-Lex-32008L0098-EN-EUR-Lex. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32008L0098 (accessed on 21 August 2020).

- Di Maria, F.; Beccaloni, E.; Bonadonna, L.; Cini, C.; Confalonieri, E.; La Rosa, G.; Milana, M.R.; Testai, E.; Scaini, F. Minimization of spreading of SARS-CoV-2 via household waste produced by subjects affected by COVID-19 or in quarantine. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 743, 140803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kargar, S.; Pourmehdi, M.; Paydar, M.M. Reverse logistics network design for medical waste management in the epidemic outbreak of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19). Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 746, 141183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ECDC European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Infection Prevention and Control in the Household Management of People with Suspected or Confirmed Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19). Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/infection-prevention-control-household-management-covid-19 (accessed on 20 August 2020).

- European Commission. Waste Management in the Context of the Coronavirus Crisis. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/waste_management_guidance_dg-env.pdf (accessed on 21 July 2020).

- Republic of Poland. The Act of 2 March 2020 on Special Solutions Related to the Prevention, and Combating of COVID-19, Other Infectious Diseases and Crisis Situations Caused by Them. (Ustawa z Dnia 2 Marca 2020 r. o Szczególnych Rozwiązaniach Związanych z Zapobieganiem, Przeciwdziałaniem i Zwalczaniem COVID-19, Innych Chorób Zakaźnych Oraz Wywołanych Nimi Sytuacji Kryzysowych). J. Laws 2020, poz. 374. (In Polish). Available online: http://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20200000374/T/D20200374L.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2020).

- Mol, M.P.G.; Caldas, S. Can the human coronavirus epidemic also spread through solid waste? Waste Manag. Res. 2020, 38, 485–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health of Poland. Organizational Standard of Care in the Isolation Room in Relation to the Prevention of SARS-CoV-2 Infection; Standard Organizacyjny Opieki w Izolatorium w Związku z Przeciwdziałaniem Zakażeniu Wirusem SARS-CoV-2; Ministry of Health Decree; Ministry of Health of Poland: Warsaw, Poland, 2020. (In Polish)

- Ministry of Climate. Guidelines of Ministry of Climate and Head of Public Sanitary Office Concerning Handling the Waste during SARS-CoV-2 Epidemics and Illness COVID-19. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/klimat/wytyczne-ws-postepowania-z-odpadami-w-czasie-wystepowania-zakazen-koronawirusem-sars-cov-2 (accessed on 30 July 2020).

- Tukker, A. Plastics Waste: Feedstock Recycling, Chemical Recycling and Incineration; RAPRA review reports; RAPRA Technology Limited: Shrewsbury, UK, 2002; ISBN 978-1-85957-331-0. [Google Scholar]

- Windfeld, E.S.; Brooks, M.S.-L. Medical waste management—A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 163, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajmohan, K.V.S.; Ramya, C.; Viswanathan, M.R.; Varjani, S. Plastic pollutants: Effective waste management for pollution control and abatement. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2019, 12, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rist, S.; Almroth, B.C.; Hartmann, N.B.; Karlsson, T.M. A critical perspective on early communications concerning human health aspects of microplastics. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 626, 720–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalina, M.; Tilley, E. “This is our next problem”: Cleaning up from the COVID-19 response. Waste Manag. 2020, 108, 202–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistics Poland. Population. Size and Structure and Vital Statistics in Poland by Territorial Division in 2019; Statistics Poland: Warsaw, Poland, 2020. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/download/gfx/portalinformacyjny/en/defaultaktualnosci/3286/3/27/1/population._size_and_structure_and_vital_statistics_in_poland_by_territorial_division_in_31.12.2019.pdf (accessed on 21 July 2020).

- Statistics Katowice. Population, Vital Statistics and Migrations in Śląskie Voivodship in 2019. Available online: https://katowice.stat.gov.pl/files/gfx/katowice/pl/defaultaktualnosci/756/2/18/1/ludnosc_2020.pdf (accessed on 27 June 2020).

- Saadat, S.; Rawtani, D.; Hussain, C.M. Environmental perspective of COVID-19. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 728, 138870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patrício Silva, A.L.; Prata, J.C.; Walker, T.R.; Campos, D.; Duarte, A.C.; Soares, A.M.V.M.; Barcelò, D.; Rocha-Santos, T. Rethinking and optimising plastic waste management under COVID-19 pandemic: Policy solutions based on redesign and reduction of single-use plastics and personal protective equipment. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 742, 140565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klemeš, J.J.; Fan, Y.V.; Tan, R.R.; Jiang, P. Minimising the present and future plastic waste, energy and environmental footprints related to COVID-19. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 127, 109883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanapalli, K.R.; Samal, B.; Dubey, B.K.; Bhattacharya, J. 12—Emissions and Environmental Burdens Associated with Plastic Solid Waste Management. In Plastics to Energy; Plastics Design Library; Al-Salem, S.M., Ed.; William Andrew Publishing: Norwich, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 313–342. ISBN 978-0-12-813140-4. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.; Sun, X.; Solvang, W.D.; Zhao, X. Reverse logistics network design for effective management of medical waste in epidemic outbreaks: Insights from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in Wuhan (China). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trivedi, A.; Singh, A.; Chauhan, A. Analysis of key factors for waste management in humanitarian response: An interpretive structural modelling approach. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2015, 14, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Local Government Office | Waste Collection Company | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Municipality | Population | Municipality | Population |

| Kalety | 8600 | Bełsznica | 1000 |

| Lubliniec | 23,000 | Mszana | 3600 |

| Pszczyna | 26,000 | Chybie | 4000 |

| Zawiercie | 50,000 | Marklowice | 5000 |

| Będzin | 53,000 | Godów | 14,000 |

| Piekary Śląskie | 55,000 | Pawłowice | 18,000 |

| Tarnowskie Góry | 60,000 | Myszków | 32,000 |

| Żory | 62,000 | Jastrzebie-Zdrój | 48,000 |

| Mysłowice | 73,000 | Racibórz | 55,000 |

| Bytom | 160,000 | Siemianowice Śląskie | 65,000 |

| Katowice | 300,000 | Wodzisław Śląski | 90,000 |

| Rybnik | 138,000 | ||

| Zabrze | 170,000 | ||

| Gliwice | 180,000 | ||

| Częstochowa | 220,000 | ||

| Katowice | 300,000 | ||

| Question | Answers |

|---|---|

| Do you know what is correct method for disposal of waste personal protective equipment (PPE)? | Yes/No |

| How do you dispose of PPE—face masks or gloves? | Collection together with mixed waste Collection in other separated bags Collection separately (together with plastics) Disposal of wherever available |

| Which method is correct for the disposal of waste PPE? | They can be disposed wherever possible They should be placed in a separated waste They should be placed in mixed waste Special bags or containers should be provided Not sure |

| Have you noticed any improper methods of waste PPE disposal? | Yes/No |

| Are there any improper methods of PPE disposal? | Disposal of wherever available Wrong category of waste selection Not sure |

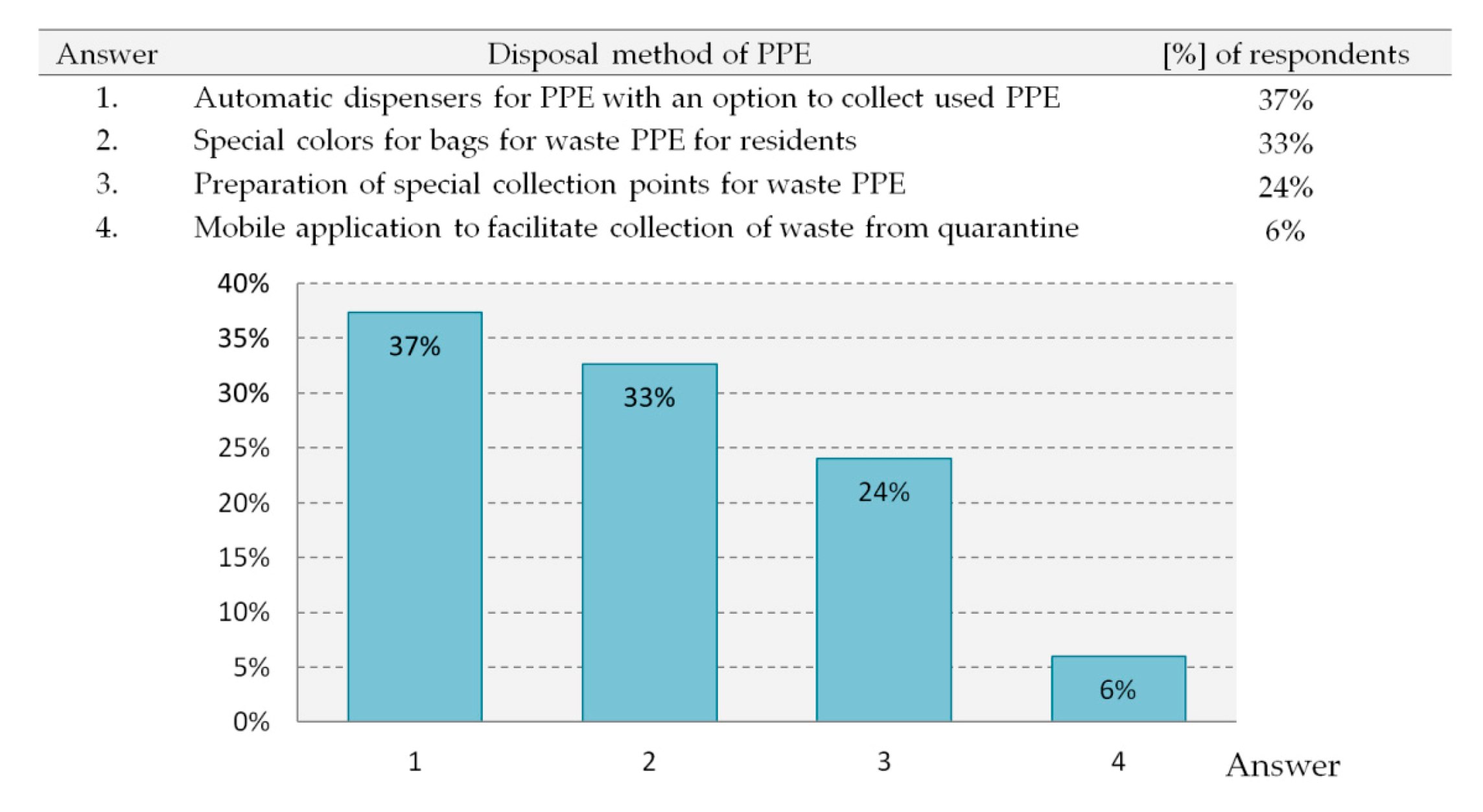

| Have you any idea how to support waste PPE collection? | Automatic dispensers for PPE with an option to collect used PPE Special colors for bags for waste PPE for residents Preparation of special collection points for waste PPE Mobile application to facilitate collection of waste from quarantine |

| Factor | Value | Number of Responses |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 99 |

| Female | 51 | |

| Age | 18–25 | 84 |

| 26–35 | 39 | |

| 36–45 | 11 | |

| 46–55 | 11 | |

| >55 | 5 | |

| Type of habitation | Urban | 87 |

| Rural | 63 | |

| Population of municipality | <5000 | 54 |

| 5000–50,000 | 24 | |

| 50,000–200,000 | 27 | |

| >200,000 | 45 |

| Entity | Measures Taken | Number of Municipalities/Number of Inhabitants in Municipalities | Process Type Waste Collection from Quarantine Points | Process Type Waste Transportation and Processing from Quarantine Points |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local government environmental department | None or minor | 2/100,000 | The collection is in accordance with the regular schedule, with the same timeline | No additional vehicles or routes required, processing is conducted with separated or mixed waste |

| Major or significant | 9/700,000 | The residents are required to use additional bags for PPE; the collection is postponed up to nine days; in some cases, local administration delivers special bags or containers | The local authorities require additional routes or use of special vehicles for medical waste. If the routing is conducted on an ordinary schedule, the quarantine points must be the last visited | |

| Waste collection company | None or minor | 14/950,000 | The collection is in accordance with the previously assigned schedule, the same containers, waste bins or bags used | The same collection vehicles and processing as for normal operation—the employees in the waste processing plants are equipped with protective gloves and glasses |

| Major or significant | 2/365,000 | Additional bags provided to quarantine points; if available red color of bag required, the bags remain quarantined additional 48 h in the waste collection company warehouse. | Transportation by additional vehicles, if available—vehicles for medical waste are used, the waste after collection is directed to incineration plant |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nowakowski, P.; Kuśnierz, S.; Sosna, P.; Mauer, J.; Maj, D. Disposal of Personal Protective Equipment during the COVID-19 Pandemic Is a Challenge for Waste Collection Companies and Society: A Case Study in Poland. Resources 2020, 9, 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources9100116

Nowakowski P, Kuśnierz S, Sosna P, Mauer J, Maj D. Disposal of Personal Protective Equipment during the COVID-19 Pandemic Is a Challenge for Waste Collection Companies and Society: A Case Study in Poland. Resources. 2020; 9(10):116. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources9100116

Chicago/Turabian StyleNowakowski, Piotr, Sandra Kuśnierz, Patrycja Sosna, Jakub Mauer, and Dawid Maj. 2020. "Disposal of Personal Protective Equipment during the COVID-19 Pandemic Is a Challenge for Waste Collection Companies and Society: A Case Study in Poland" Resources 9, no. 10: 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources9100116

APA StyleNowakowski, P., Kuśnierz, S., Sosna, P., Mauer, J., & Maj, D. (2020). Disposal of Personal Protective Equipment during the COVID-19 Pandemic Is a Challenge for Waste Collection Companies and Society: A Case Study in Poland. Resources, 9(10), 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources9100116