1. Introduction

Consumers are key participants with the potential to foster a circular transition even on an individual basis [

1,

2,

3]. This transitional shift is referred to as circular consumption behavior, which adheres to circular economy principles and is based on consumers’ decisions and activities [

4,

5,

6]. Accordingly, through their consumption behavior, consumers address their needs through product acquisition, usage, and post-use activities. These activities must be circularly integrated to achieve substantial benefits. Most importantly, the consumption of electronic products (e-products) requires circular transformation, as consumers are the starting point of electronic waste (e-waste) and can determine its destination [

7,

8].

Consumers have dual functional roles concerning product consumption, involving acquisition from circular sources and ensuring proper disposal at their end of life (EoL) [

9]. Both polar phases reflect upstream and downstream activities, making circular consumption an intricate phenomenon with increasing importance and a growing research area [

6,

10,

11,

12]. Recently, Jourdain and Lamah [

12] elaborated on such a perspective in terms of addressing and reducing product demand and disposal, examining a quintessential scenario with circularly integrated activities. The extant literature draws attention to the hierarchical R-strategies used to extend products’ lifespan and materials’ circulation based on knowledge-based and attitudinal aspects [

13,

14,

15,

16]. Thus, the connection of upstream and downstream activities will yield a circular transition based on the intersection of product consumption phases.

Consumer behavior research has progressed significantly, yet limited attention is paid to consumer-centric aspects of the circular economy [

17,

18]. Despite being at the center of the circular economy framework, consumers’ decision making and consumption behavior is largely overlooked [

3,

17]. Furthermore, their engagement across the full consumption cycle is still not addressed, especially considering the menace of e-waste [

19]. Specific R-imperatives have been adopted, with higher circular strategies having been addressed least, making consumers’ adoption of them a relatively new and underexamined area of research [

5,

9]. Developing awareness from such a perspective is the first step [

20,

21], as this perception leads to positive attitudinal factors and subsequently transforms consumption behavior by encouraging the adoption of R-strategies [

22,

23]. However, the literature highlights that inadequate circular economy knowledge impedes this transition due to a lack of awareness and disposal practices [

24,

25], especially limited knowledge and comprehension of circular economy processes regarding e-waste management [

1,

26]. Such inhibitory factors yield a lax attitude followed by deviant behavior including extravagant purchasing and consumption [

27], revealing the role of circular economy knowledge and attitudinal factors as foundational antecedents for circular consumption behavior.

Additionally, the attitude–behavior link manifests variation over the consumption phases. The literature documents a gap where individuals fail to consistently translate their attitudes into targeted behavior despite having a predisposition towards environmental protection [

10,

28]. This pattern of behavior may arise due to a lack of specific knowledge, established habits [

10], and/or concern about environmental issues [

29]. However, a combination of social and contextual factors and established habits plays a key role in its transformation [

2,

10,

30]. These habits are incrementally developed, exhibiting a propensity to change behavior [

31]. Routine practices or habits are essential elements, especially due to their connection with the attitude–behavior link. The emphasis should not only be on the attitude–behavior link but also on how practices are formed [

5], which is often overlooked in shaping a routinized behavior [

31]. Consumers engaging in a particular circular behavior typically demonstrate other behavioral characteristics [

4]. To conclude, it is pivotal to explore consumer’s consumption behavior in relation to their knowledge level, attitudes, concern for the environment, social responsibility, and habits, as these factors can provide important insights.

This transformation is driven by a transitional process that moves from knowledge to attitude and, subsequently, to circular behavior. Consumer engagement is pivotal to successful circular economy processes and is contingent upon awareness and motivation for active participation in circular practices [

17]. A critical and emerging challenge is consumers’ reluctance toward circular consumption, which warrants further investigation [

21]. To address this, we explore consumption behavior [

17,

32], particularly with respect to e-waste management [

7,

8,

19]. This paper’s novel contribution is the theoretical integration of circular economy knowledge, attitude–behavior–context theory, and practice theory. This study posits three research questions. (1) What is the influence of circular economy knowledge on contextual factor, attitude and circular consumption behavior? (2) What is the direct and mediating impact of contextual factor and attitude? (3) What is the moderating influence of habit? Accordingly, the research objective is to explore circular consumption behavior by examining consumers’ upstream and downstream circular activities, based on 8R-strategies, such as refuse, rethink, reduce, reuse, repair, refurbish, repurpose, and recycle.

This study makes several contributions by focusing on two categories of e-products: laptops and mobile phones. First, it provides a broader conceptualization of circular consumption behavior that encompasses consumers’ upstream and downstream activities and the underlying 8R-strategies. This conceptualization integrates four phases, based on the conjunction of these strategies that both foster and slow down product demand and disposal [

12]. Second, this research views the consumption process as more than a single act; it is a comprehensive set of choices and decisions, from purchasing an e-product to its usage and proper disposal [

10]. Consequently, a consumer is seen as both a purchaser and a resource supplier. Third, this study specifically focuses on consumers’ consumption practices, an aspect that few studies have explored [

3]. Fourth, the role of consumers in the circular supply chain remains unclear, as extant studies have often focused on specific R-strategies [

5,

9]. Finally, this research investigates the moderating impact of habit on the relationship between activating variables and circular consumption behavior, with a specific focus on its influence on the attitude–behavior link.

The rest of the article is structured as follows:

Section 2 presents the theoretical framework, conceptualization of circular consumption behavior, and the research model. Following that,

Section 3 outlines the research hypotheses. The research method is detailed in

Section 4. Subsequently, the analysis and findings are provided in

Section 5. The discussion is presented in

Section 6, which also includes the theoretical and practical implications, limitations and future directions. Finally, the paper is concluded in

Section 7.

6. Discussion and Implications

Consumers play an important role in driving circular consumption [

3,

13]. This is a cyclic approach that starts with an e-product purchase decision, functional consumption, and proper disposal at its EoL [

4,

32]. We explored circular consumption behavior by connecting downstream and upstream activities, based on four circular activities: fostering demand, slowing down demand, slowing down disposal, and fostering disposal in terms of 8R-strategies, as detailed in

Section 2.2. This study conceptualizes a circular supply chain where individuals can simultaneously act as consumers and resource providers.

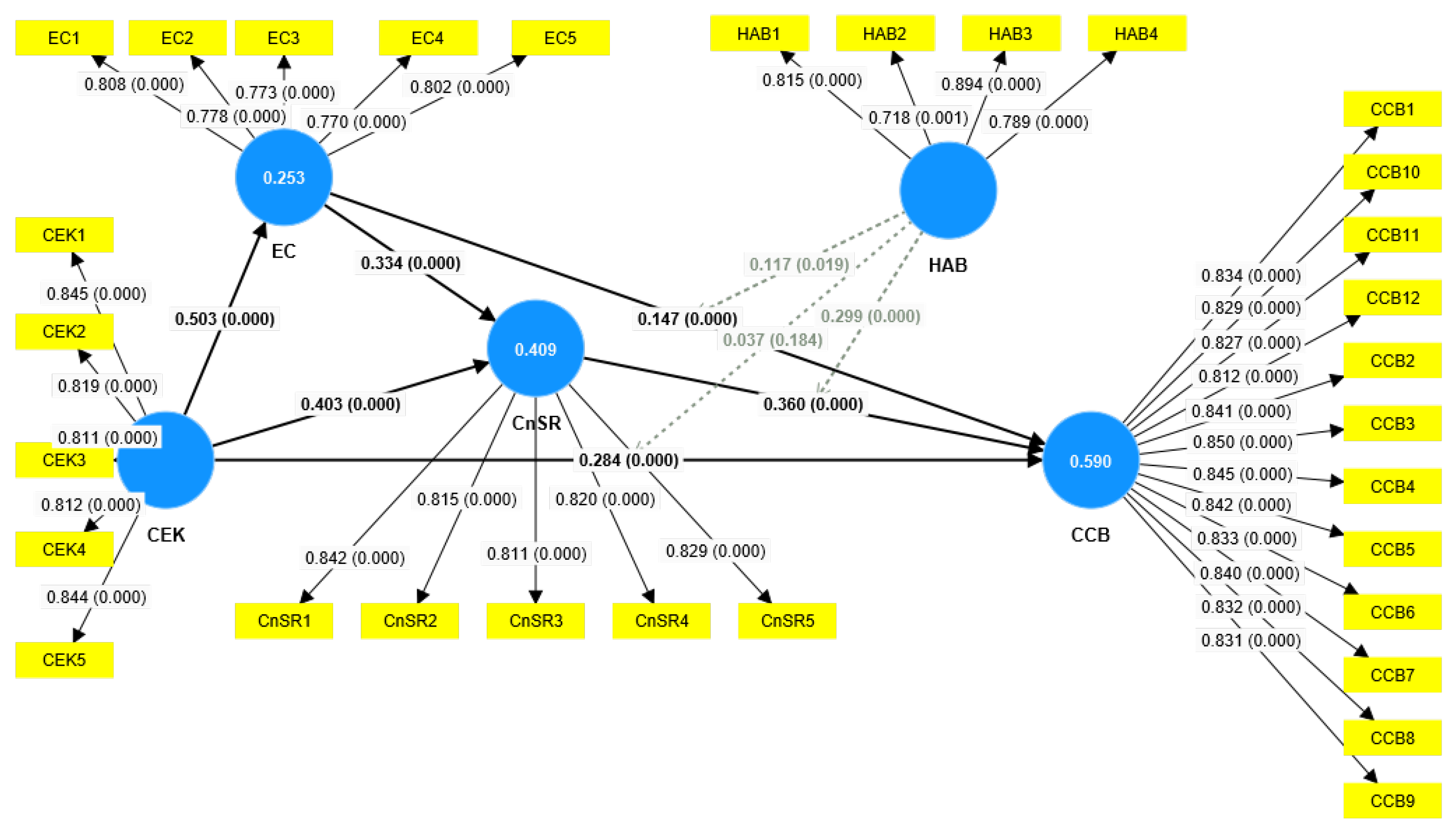

Hypotheses 1, 2, and 3 empirically confirm the theoretical role of circular economy knowledge as a driving factor in circular consumption behavior [

3,

84]. This finding is further supported by several research studies [

23,

39,

51,

96]. Our results also validate the linear directional pervasive model, which describes the learning behavioral transformational phases from knowledge to attitude and, subsequently, to behavior [

97]. Because the results are positive and significant, they align with [

98], who argue that a certain level of knowledge shapes positive attitudes, leading to behavioral transformation. Furthermore, when consumers gain circular economy knowledge, they exhibit more concern, show greater social responsibility, and engage in circular consumption behavior. This process begins with acquiring an e-product, using it, and ensuring its proper disposal, thereby replacing traditional consumption practices. These changes include purchasing refurbished smartphones [

99], remanufactured smartphones [

90], opting for eco-labeled products [

32,

49,

50], and focusing on product longevity [

50]. Other behaviors include avoiding hibernation [

12,

63], proper maintenance [

55,

61], disposal [

12,

50], engaging in return policy [

12], and recycling [

21,

100].

Hypotheses 4 and 5 are based on attitude–behavior–context theory [

34], with the assumption that contextual factors are imperative for influencing individuals’ attitudes and behavior [

30,

37]. Hypothesis 4 indicates that environmental concern directly and positively impacts circular consumption behavior. This validates the importance of environmental concern in promoting circular practices [

23,

30,

32]. Extant literature also reports similar results [

23,

24,

32,

73]. Finally, as hypothesized in Hypothesis 5, consumer social responsibility directly influences circular consumption behavior. This is because consumers feel the social and environmental impact of their actions. This notion is consistent with the perception that consumers with responsible attitudes tend to exhibit the same behavior [

41]. This development is guiding consumers toward a shared social and ethical responsibility [

40], making them mindful of their purchasing and consumption choices.

On the contrary, some studies have acknowledged a weak link where knowledge has no direct impact on behavior [

29,

101]. This has led to the counterargument that knowledge does not always directly elicit consumer behavior but may be indirectly influenced by a mediator. Furthermore, attitude–behavior–context theory also predicts direct and mediating relationships. The theory suggests that contextual factors directly impact consumption behavior and indirectly influence it through their interaction with attitudes [

30]. However, the results from Ertz et al. [

30] showed an insignificant direct path of contextual factors on behavior. To explore this in more detail, we analyze the proposed mediating hypotheses based on our framework. This study proposed two mediation relationships (Hypotheses 6 and 7) where environmental concern acts as a mediator between all antecedents and circular consumption behavior. Our study, however, reported partial mediation, where environmental concern positively mediates two distinct relationships. These results are in line with other studies that have identified the mediating impact of environmental concern on factors such as circular and sustainable consumption behavior [

23,

67,

73,

78].

Moreover, Hypotheses 9 and 10 partially mediate the relationship between all antecedents and the dependent variable through consumer social responsibility. These results corroborate findings from past research [

23,

30,

39,

78]. Hypothesis 11 proposed a serial mediating path, confirming previous results that found mediation by attitudinal factors [

23,

78]. This study characterizes social responsibility in terms of an “effective responsibility”, where consumers enhance the environmental situation through responsible actions while enjoying the benefits of nature. This positive change is driven by social responsibility and behavioral transformation [

41].

The results demonstrate the strong impact of circular economy knowledge on all criterion variables. Furthermore, the mediating role of environmental concern and consumer social responsibility is also significant. This signifies the functional role of these key factors, indicating that greater knowledge leads to increased awareness, concern and responsibility in consumption patterns. Our findings suggest that consumers have a strong connection and social responsibility in relation to the circular ecosystem. Furthermore, such a connection fosters greater awareness, leading individuals to prefer eco-friendly e-products over traditional ones to prolong their life span and ensure proper disposal at their EoL.

Finally, based on Hypotheses 12 and 13, habit positively moderates the relationship of both environmental concern and consumer social responsibility with circular consumption behavior. Additionally, an insignificant relationship was observed between circular economy knowledge and circular consumption behavior, as per Hypothesis 14. Consumers who are concerned about the environment and behave responsibly tend to engage in circular consumption practices. This relationship strengthens when individuals are acting on a routine basis [

32]. This is based on the notion that adopting one practice can lead to the adoption of another. For instance, reusing can lead to repairing [

5]. Furthermore, habits and routines can influence daily behavior or lead to long-term transformation. From a broader perspective, habits and routines align behavioral transition with attitudes, which, to some extent, reinforce this relationship [

2]. Therefore, it can be inferred that when the attitude–behavior link is routinely strengthened, behavioral responses related to circular consumption practices are automatically activated.

6.1. Theoretical Implications

This research study makes several theoretical contributions to the conceptualization of circular consumption behavior. To our knowledge, most extant studies have only focused on a limited scope of consumers’ participation and role based on specific R-strategies, e.g., [

6,

21,

67,

71]. In contrast, this study adopts a circular consumption behavior model based on 8R-strategies to develop a full consumption cycle by examining consumer participation in four circular activities: (1) fostering demand, (2) slowing down demand, (3) slowing down disposal, and (4) fostering disposal.

Furthermore, this research integrates downstream and upstream activities by focusing on purchasing, usage, and disposal. Through this integrated model, a consumer acts as both an e-product user and a resource provider of EoL products and components. This study, therefore, offers a new perspective on the literature by conceptualizing consumers in this dual role.

Third, extant studies show that a key barrier to successful circular economy implementation is the lack of adequate circular economy knowledge [

1,

3,

27]. Therefore, circular economy knowledge is a pertinent and appropriate driver. Merely abstract knowledge is insufficient; instead, its practical utilization is what leads to better evaluations and practices.

Finally, we explored circular consumption behavior as a dependent variable encompassing the 8R-strategies of refuse, rethink, reduce, reuse/resell, repair, refurbish, repurpose, and recycle. In doing so, our research provides significant theoretical advancements to the conceptualization of circular consumption. Our findings suggest that consumers exhibit circular behavior when provided with proper circular economy knowledge. This knowledge augments their ability to develop environmental concern and social responsibility. This behavioral transformation facilitates and confirms the attitude–behavior–context theory, indicating that contextual factors and attitudes induce behavior. The study also discusses the attitude–behavior link by employing a moderating factor, namely habit, which was found to strengthen this relationship.

6.2. Practical Contributions

For consumers to engage in circular consumption behavior, they must first be aware of its applications. The literature suggests that consumer reluctance toward circular consumption behavior is a novel challenge [

102], especially in developing countries, where circular consumption practices are still in their nascent stages [

21]. Consumers can be influenced by addressing their issues with perception and awareness. Thus, it is essential to disseminate circular economy knowledge as a foundational tool. A noncoercive approach appears more beneficial because consumers value their self-determination and the freedom to make circular choices. Therefore, a simple-to-integrate model can facilitate their engagement.

There is a strong link between consumer awareness, behavioral transition and participation in circular practices, which suggests that circular economy policies should be widely disseminated to enhance consumers’ awareness and perception. One effective approach is the promotion and dissemination of eco-friendly and pro-environmental information about e-products. This is based on the dual notion of consumers first understanding what a circular e-product is, and then developing the capabilities and intentions of how to perform the necessary circular skills. Companies can engage consumers by first identifying and then addressing barriers. This can be achieved through promotional campaigns, “do-it-yourself” skills workshops, and offering refurbished e-products at reasonable prices under warranties. This process can also be influenced by the availability and variety of e-product offerings.

As discussed in

Section 2.2, consumers can play a crucial role in the downstream perspective. However, their participation is more effective when supported by reverse logistics, recycling systems, and return policies that include incentives. Such facilities can significantly enhance consumer convenience and encourage social responsibility and circular consumption behavior. Specifically, the availability of return policies and convenient collection facilities promotes consumer participation in post-use e-waste management.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

A key limitation of this study is the use of the cross-sectional data collection method. Future research should, therefore, adopt a longitudinal approach to obtain more compelling empirical evidence. Additionally, while this study used a convenience-based sampling method, future research could adopt a probabilistic or purposive sampling technique. Furthermore, focusing on specific age groups, such as 18–24 years and 55 and above, could yield new insights, as these groups represent only a small portion of our sample, as presented in

Table 2.

Another avenue for the future is to consider a broader range for the dependent variable, as circular consumption behavior in our model accounted for an -value of 0.590. Furthermore, a formative model could be conceptualized to uniquely contribute to the behavioral model. This study has specifically focused on circular consumption behavior from the e-product perspective. Future research could apply a similar consumption model to other sectors like food and clothing sectors, as both are major sources of waste through overconsumption. Finally, while this study employed habit as a moderator, future research could, based on attitude–behavior–context theory, explore habit as a predictor or mediator.