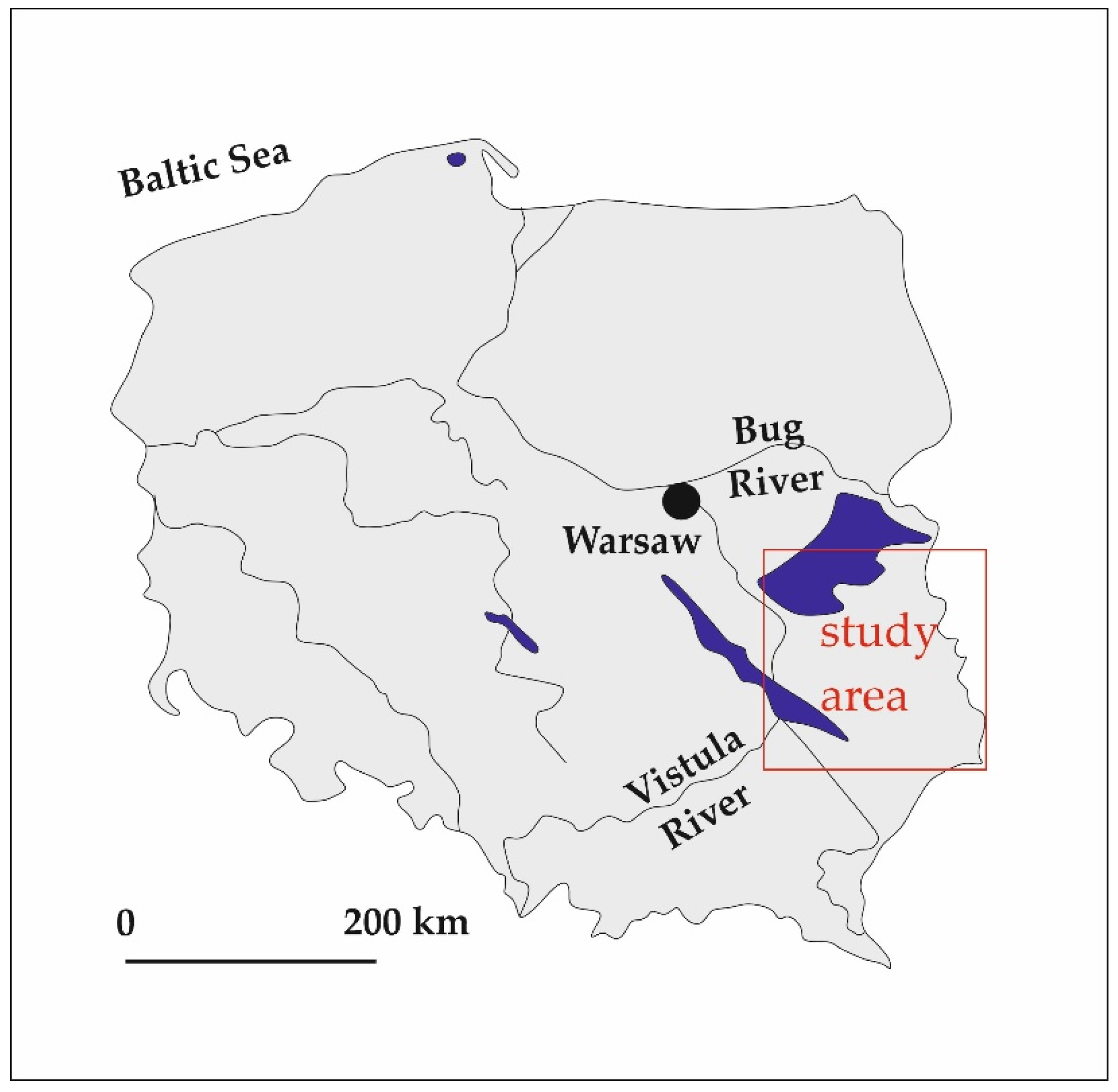

The Potential of the Vistula–Bug Interfluve Resources in the Context of the Sustainable Management of Non-Renewable Phosphorus Resources in Poland

Abstract

1. Introduction

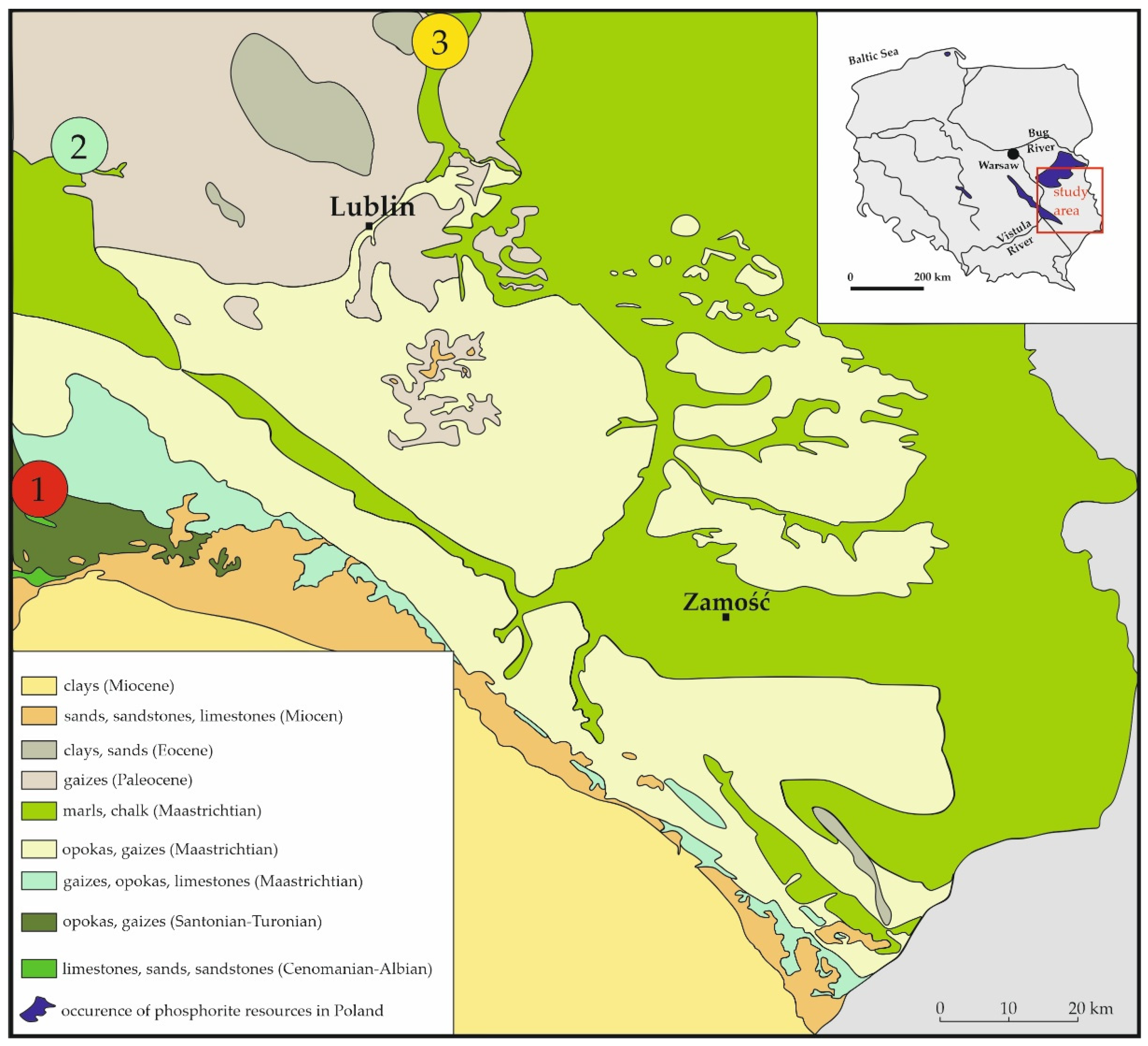

- Annopol—situated at the easternmost part of the so-called Mesozoic Border of the Holy Cross Mountains);

- Bochotnica—western part of the Nałęczów Plateau, in the Lublin Upland;

- Niedźwiada and adjacent areas—located in the Lubartów Upland, Lublin Voivodeship.

- (i)

- Our objective is to briefly present the geological and petrological characteristics of phosphorites found in the Bug–Vistula interfluve area;

- (ii)

- Our objective is to provide a geochemical and mineralogical description of phosphorites from the study area;

- (iii)

- Our objective is to discuss the potential for exploitation and use of phosphorites from the study area in the context of sustainable phosphorus management in Poland. In addition, the issue of sustainable management of P non-renewable resources at both the local and global scale is discussed in this paper.

Phosphorites in Poland: Occurrence and Exploitation

2. Study Area: Vistula–Bug Interfluve

- Annopol—numerous phosphate nodules in Upper Cretaceous glauconite sandstones;

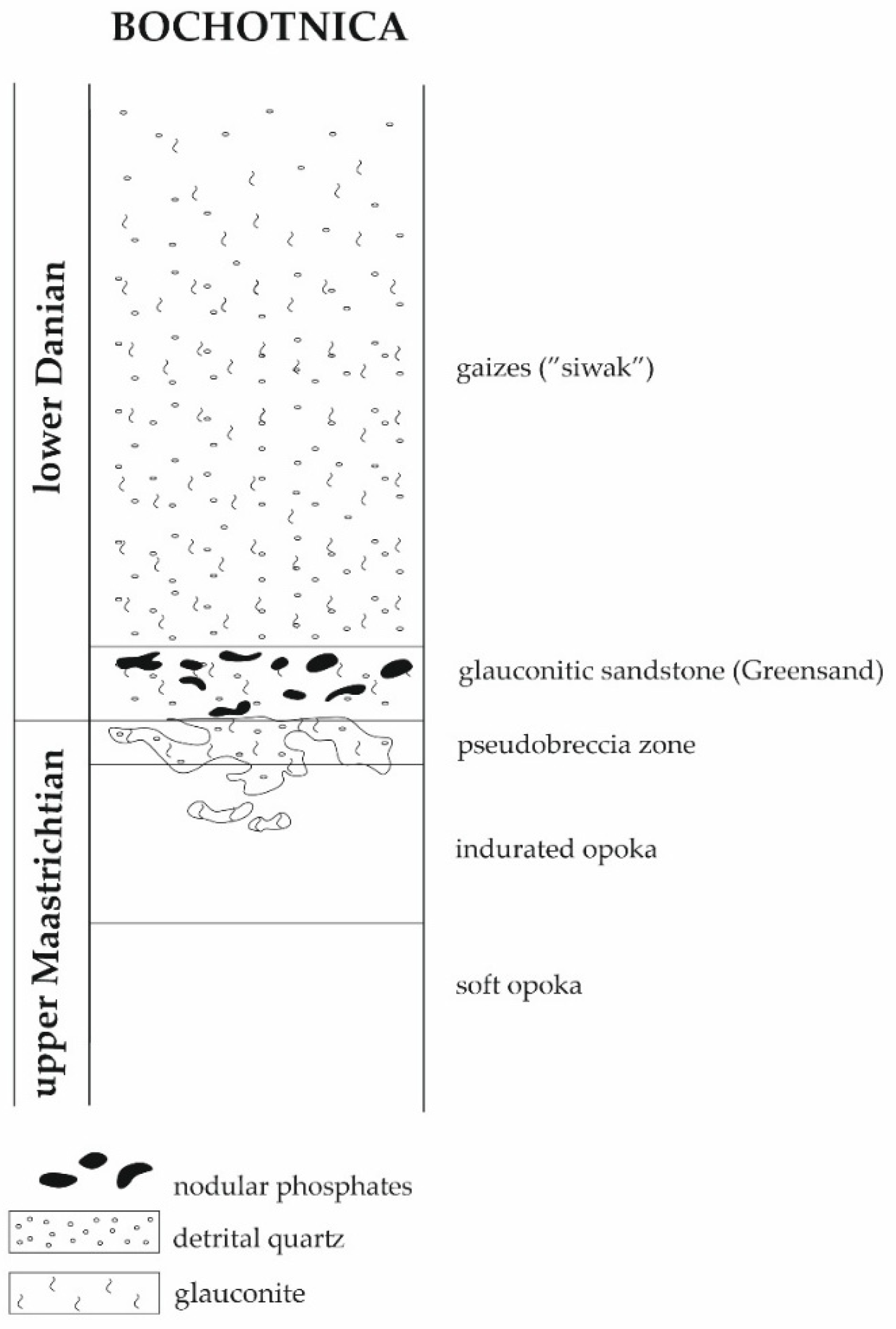

- Bochotnica—phosphate nodules associated with Danian glauconite sandstones;

- Niedźwiada—phosphate resources documented in recent years through detailed exploration of the Niedźwiada II glauconite-bearing sediment deposit, with an average P2O5 content of close to 23% [24].

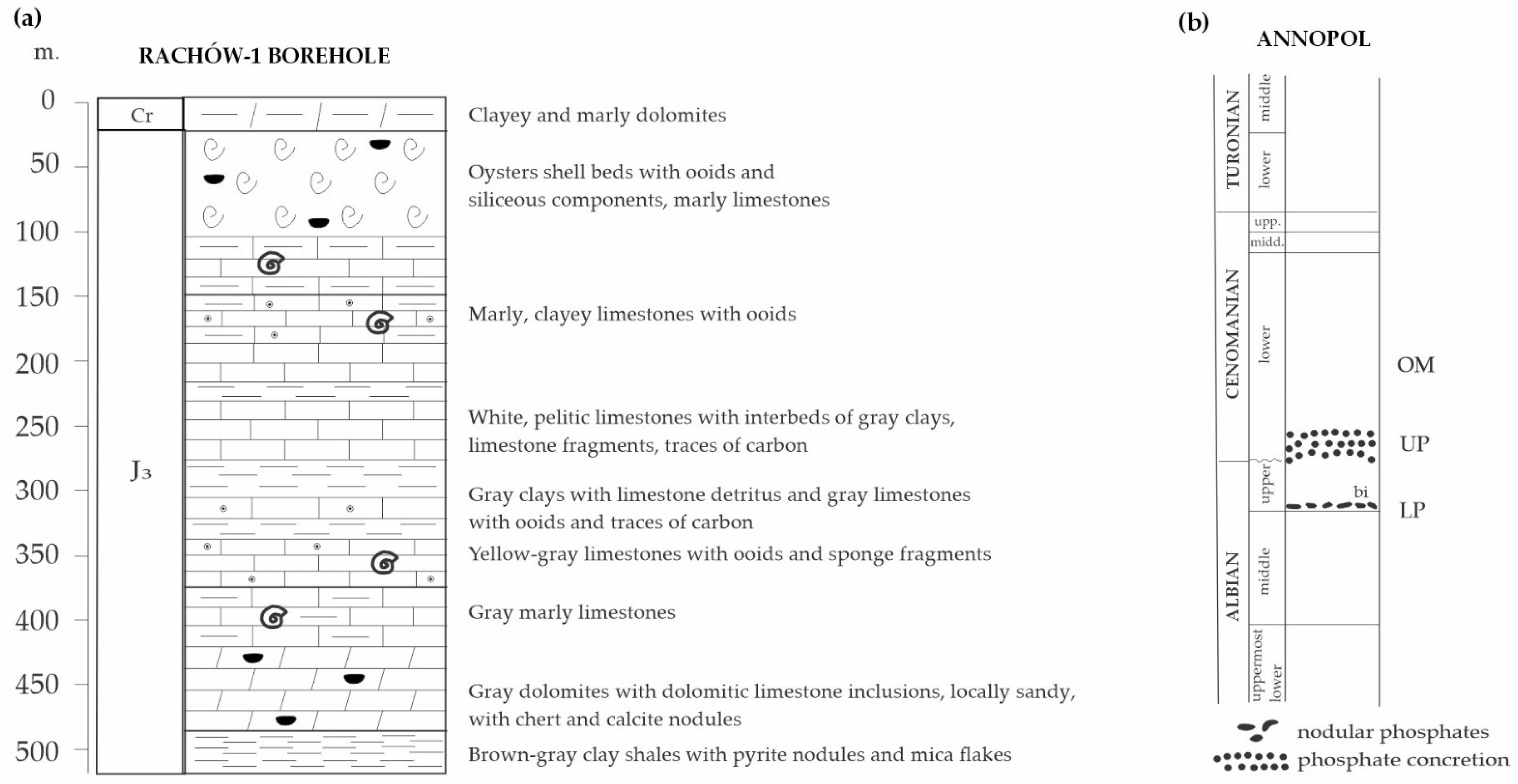

2.1. Annopol

- Albian—sandstones and sands containing glauconite were deposited in the Annopol area.

- Cenomanian—sandy glauconitic marls were formed.

- Early Turonian—limestones with minor glauconite content were deposited with the Annopol area located on a submarine elevation.

2.2. Bochotnica

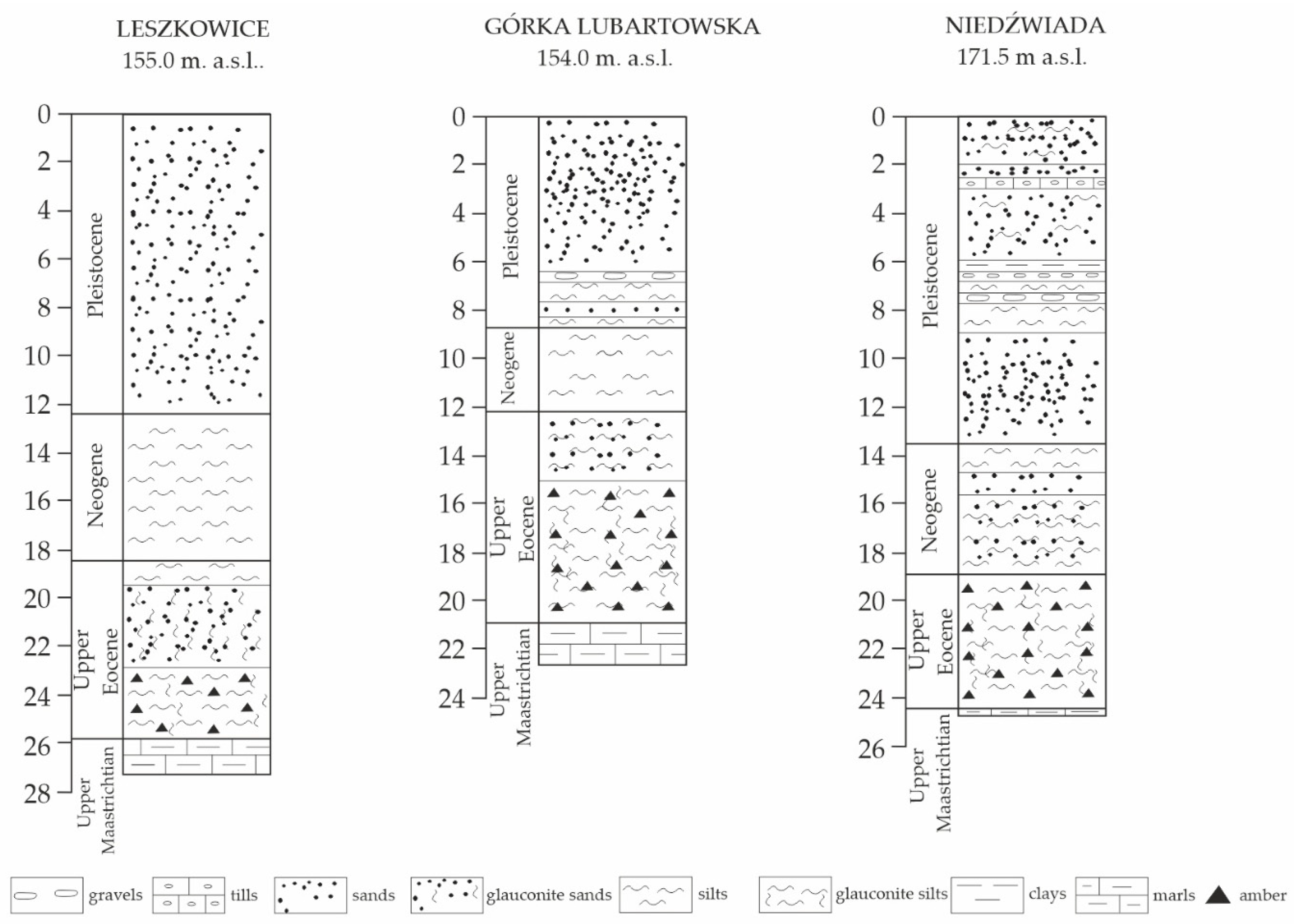

2.3. Niedźwiada and Adjacent Areas

3. Materials and Methods

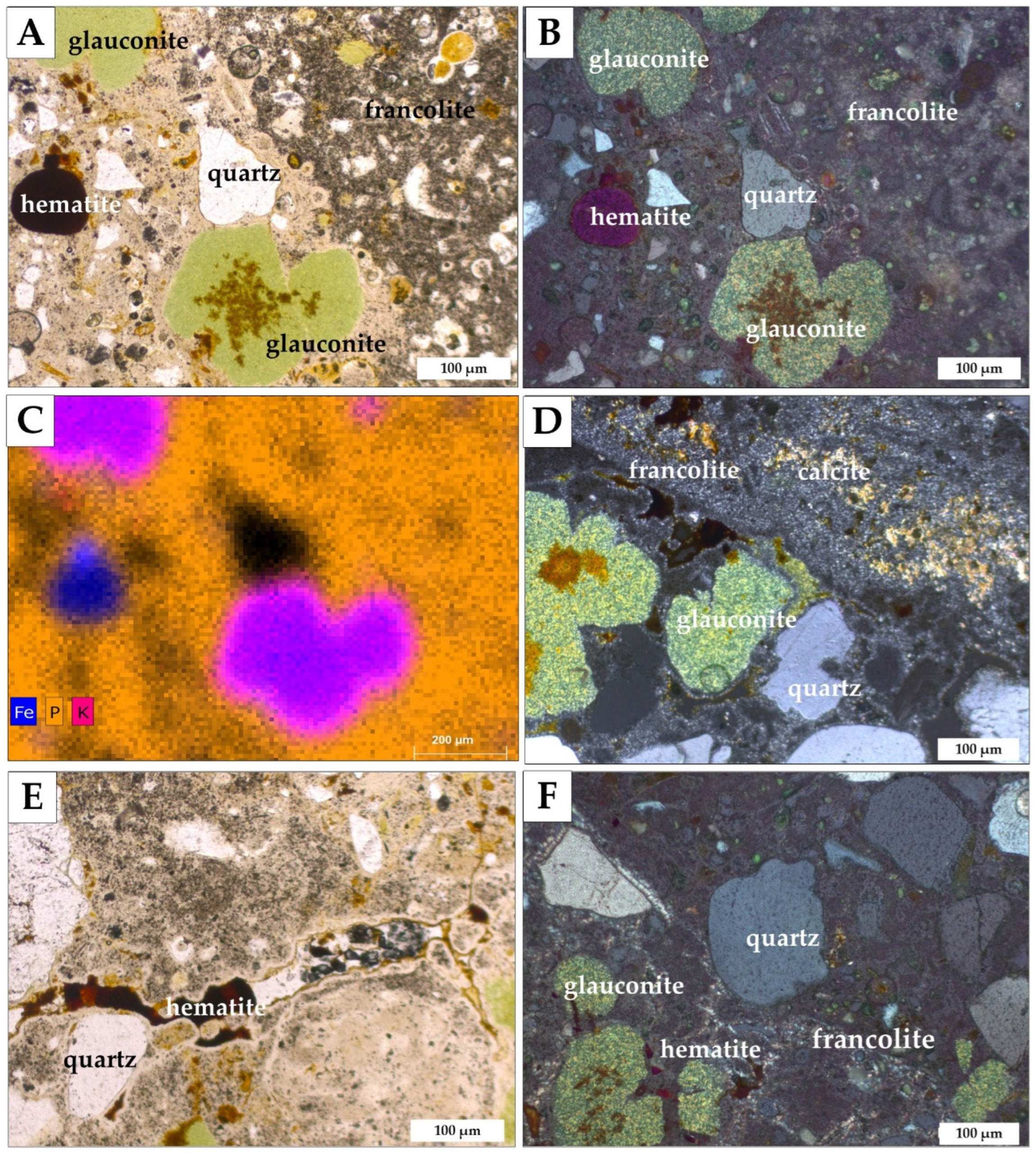

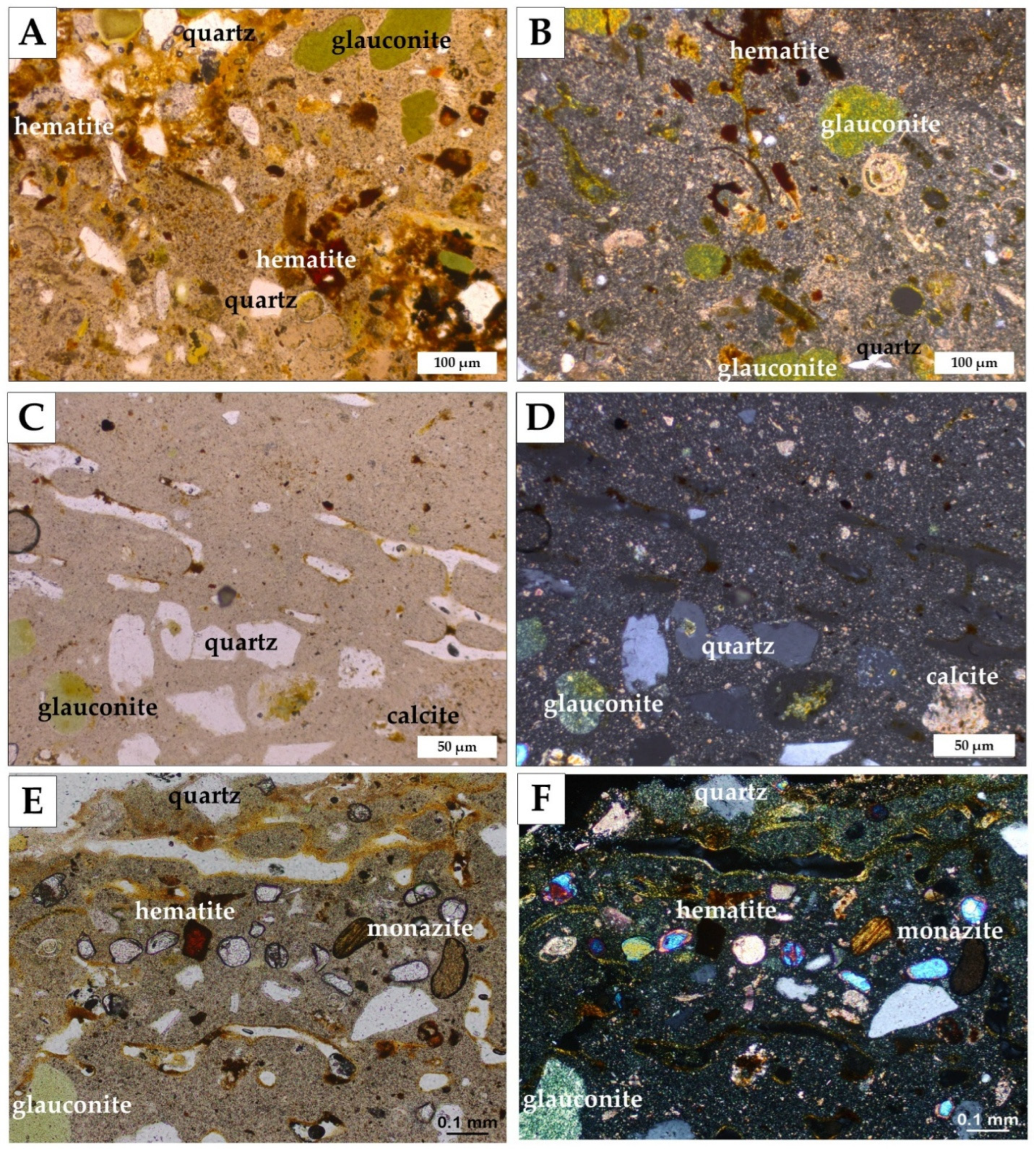

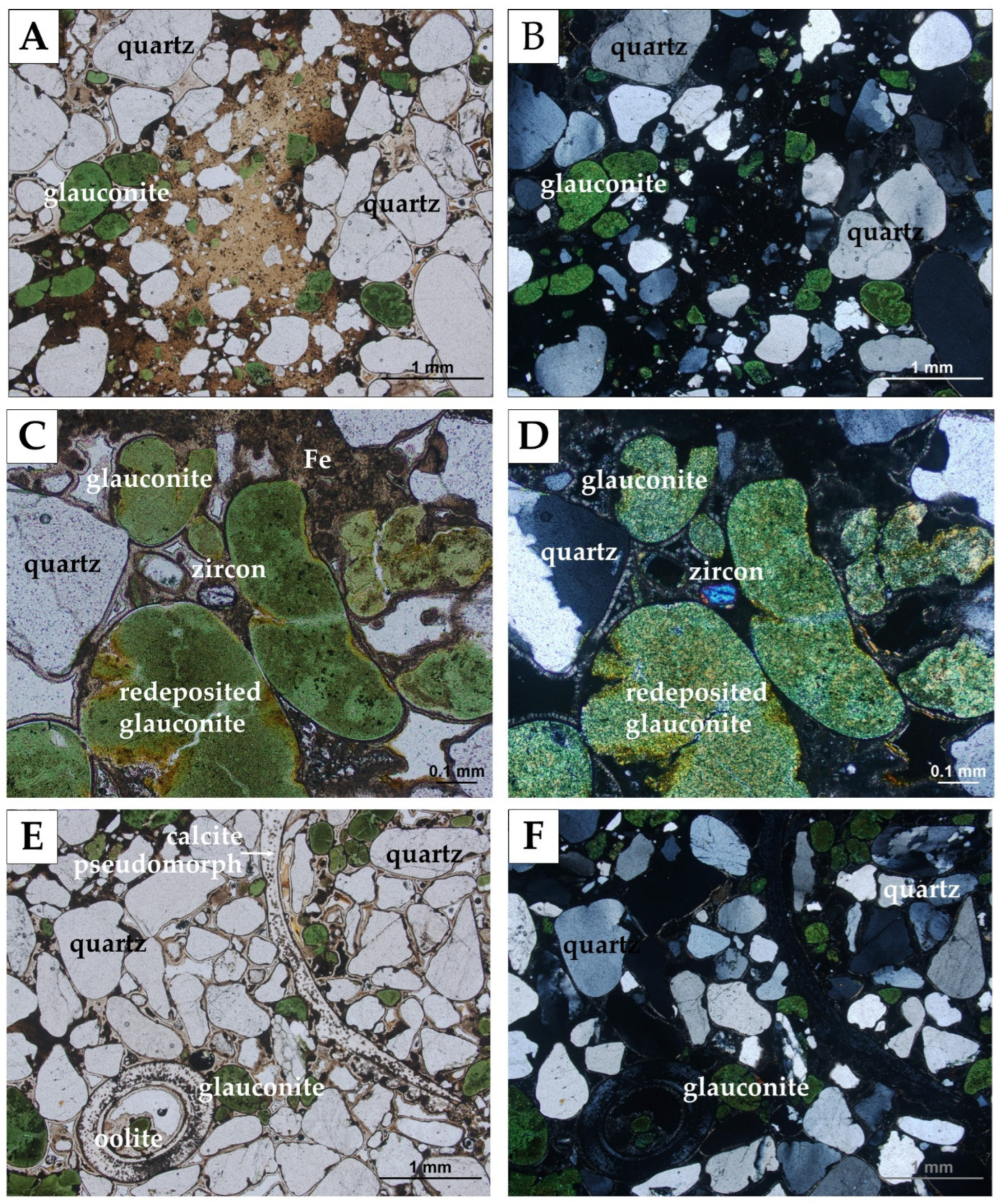

3.1. Petrography

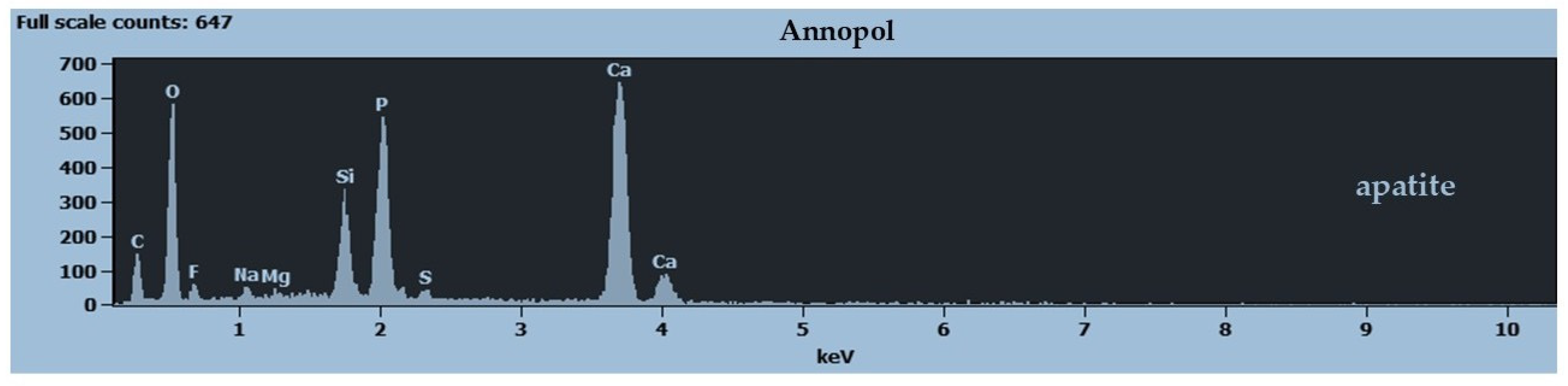

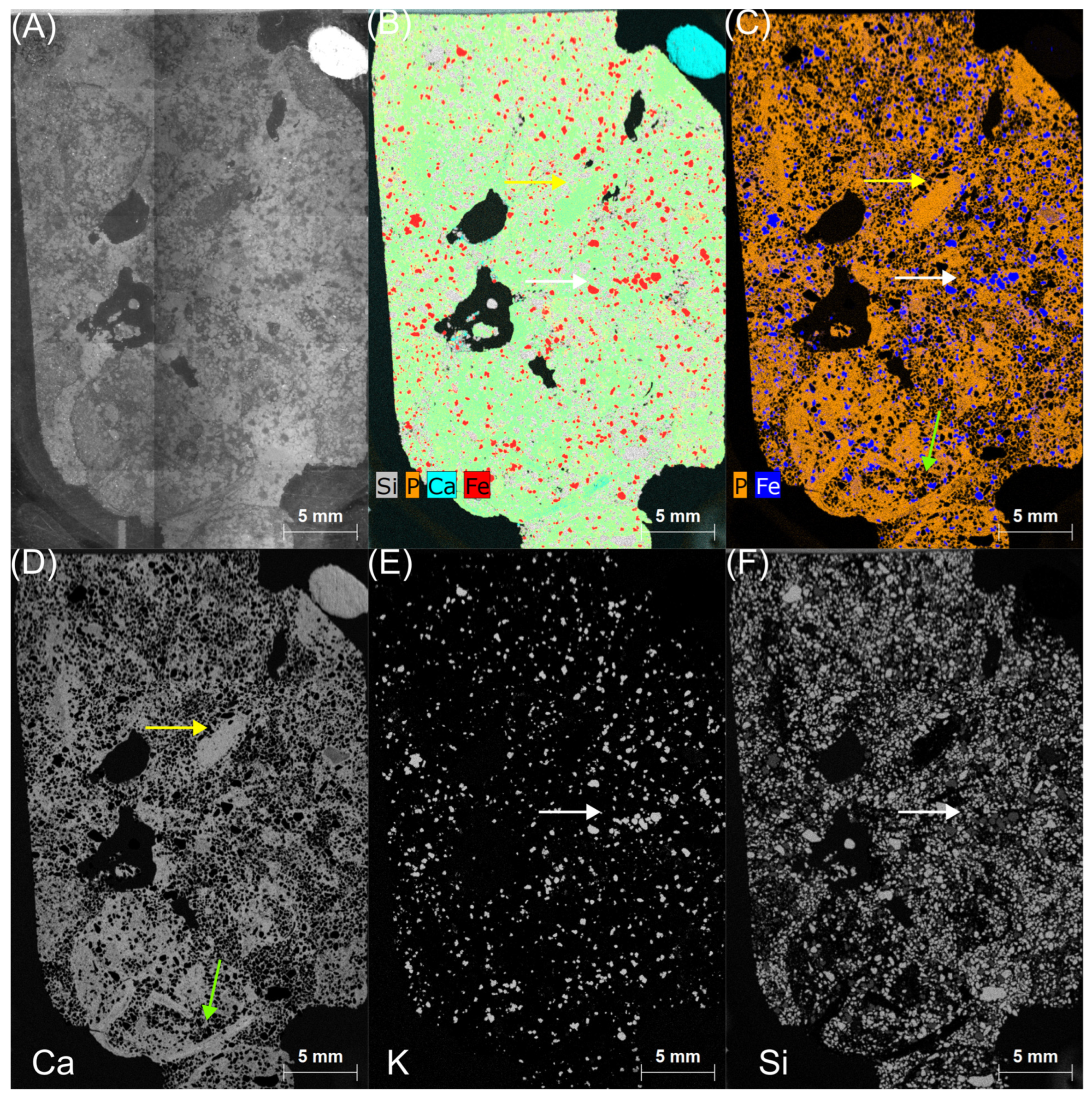

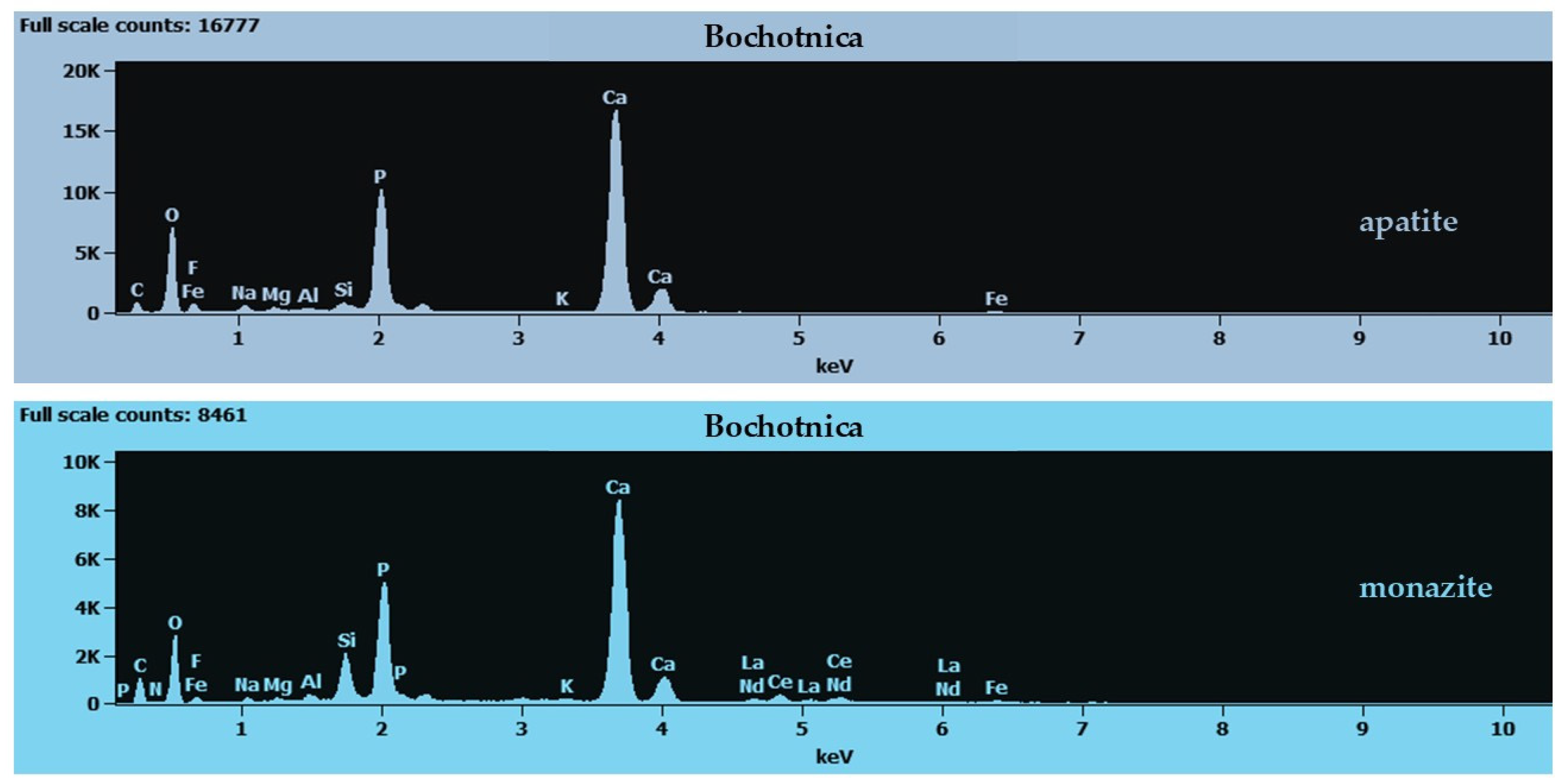

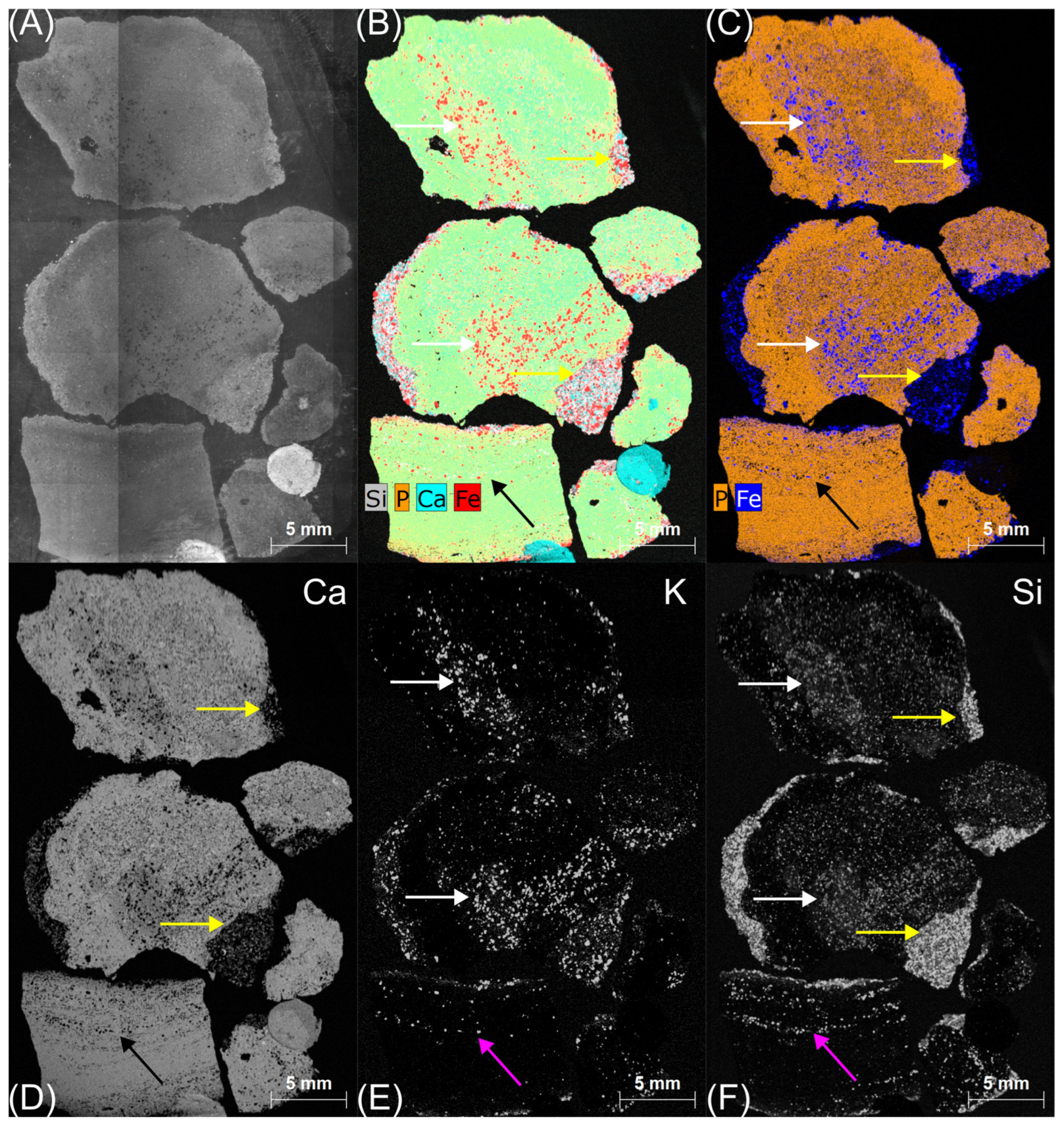

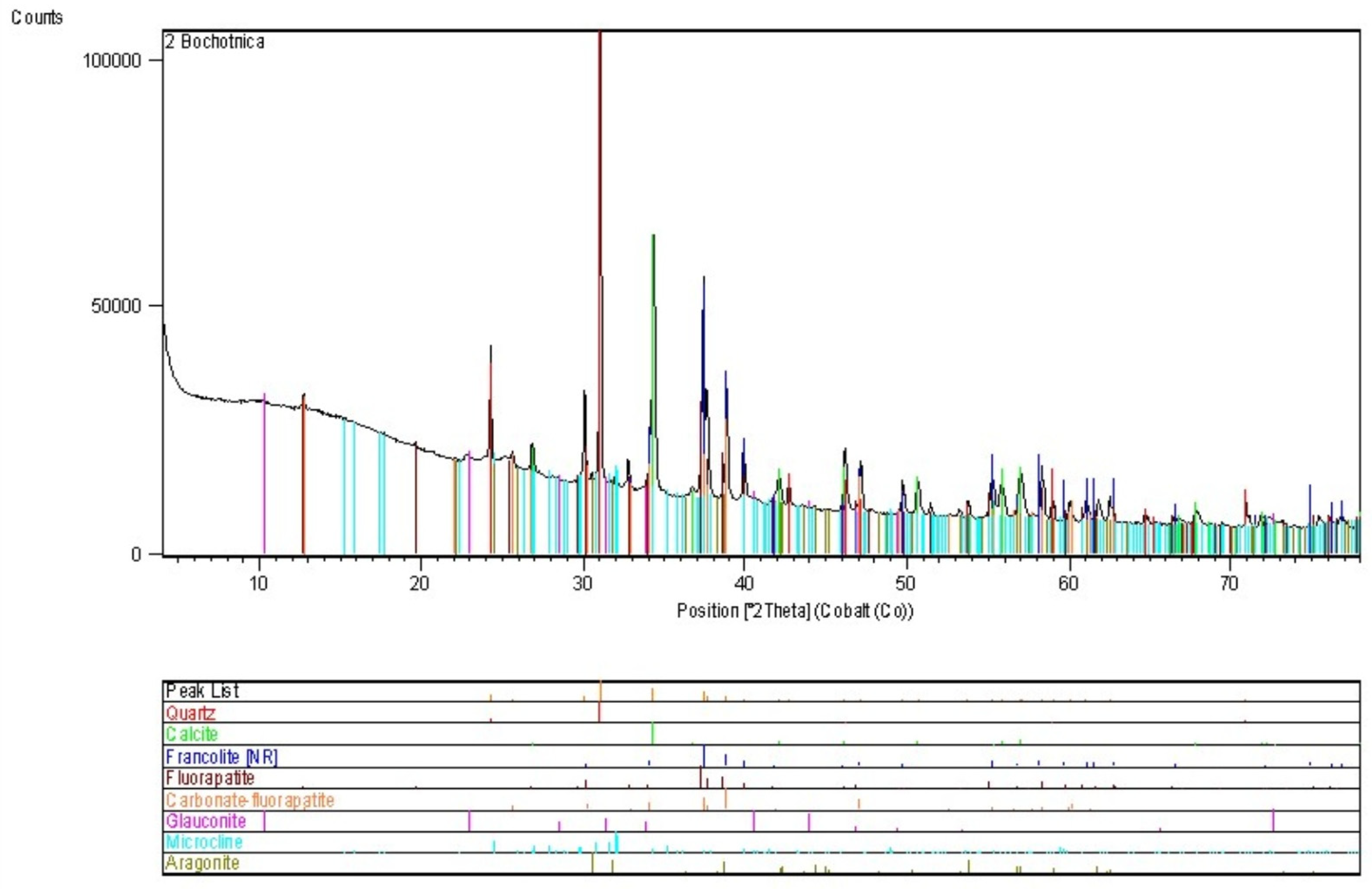

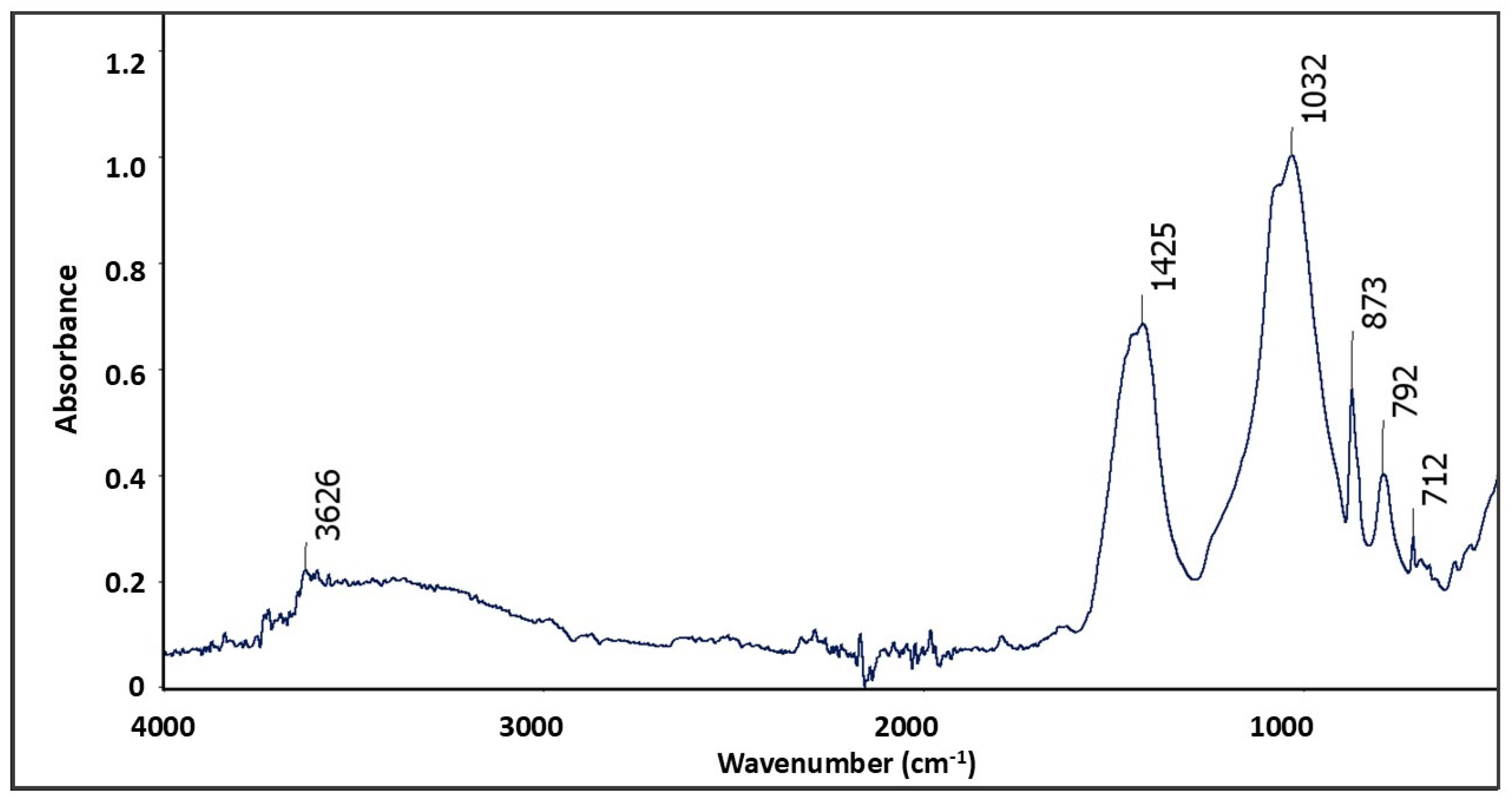

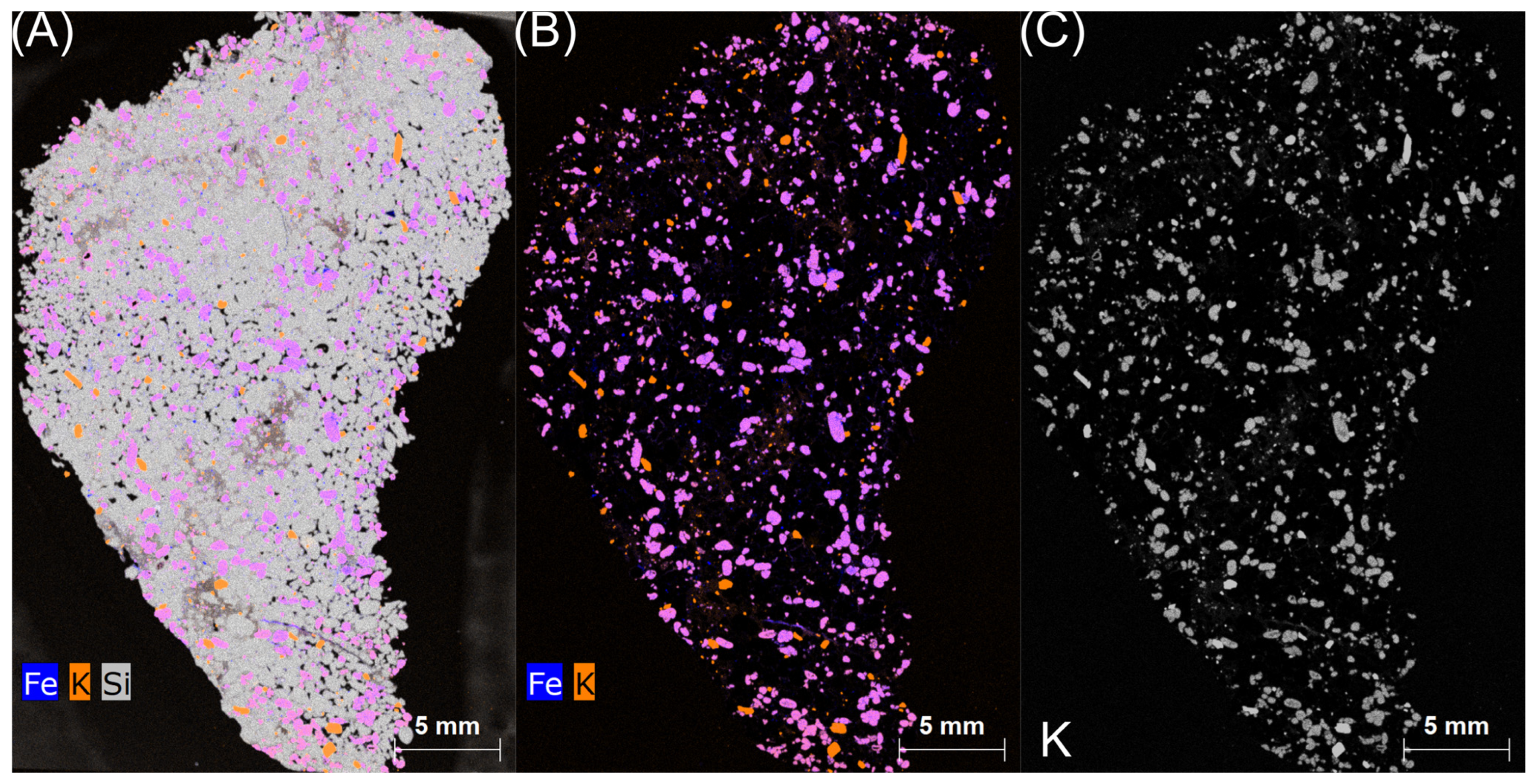

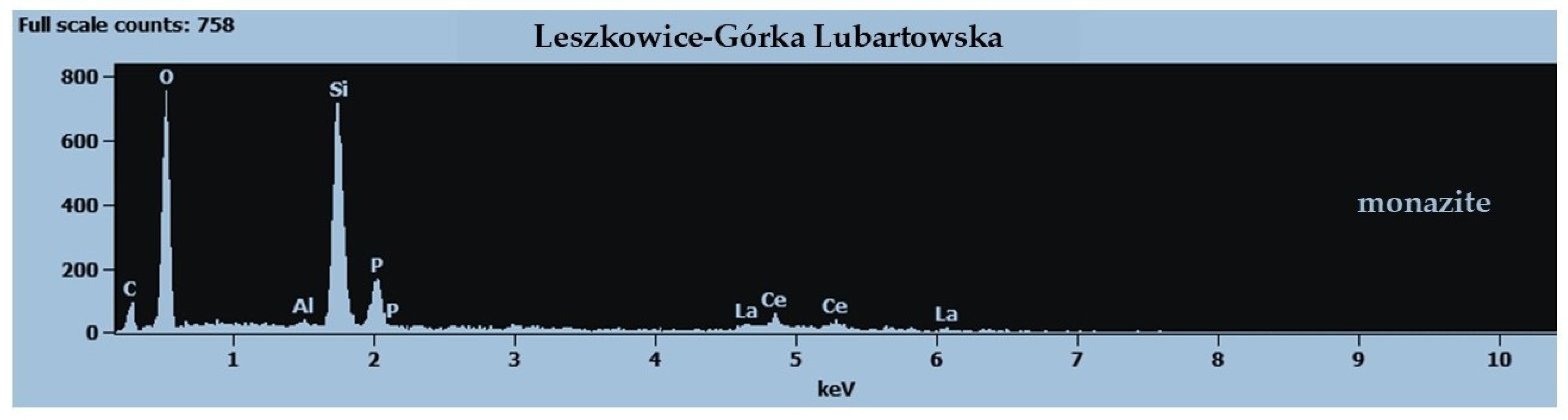

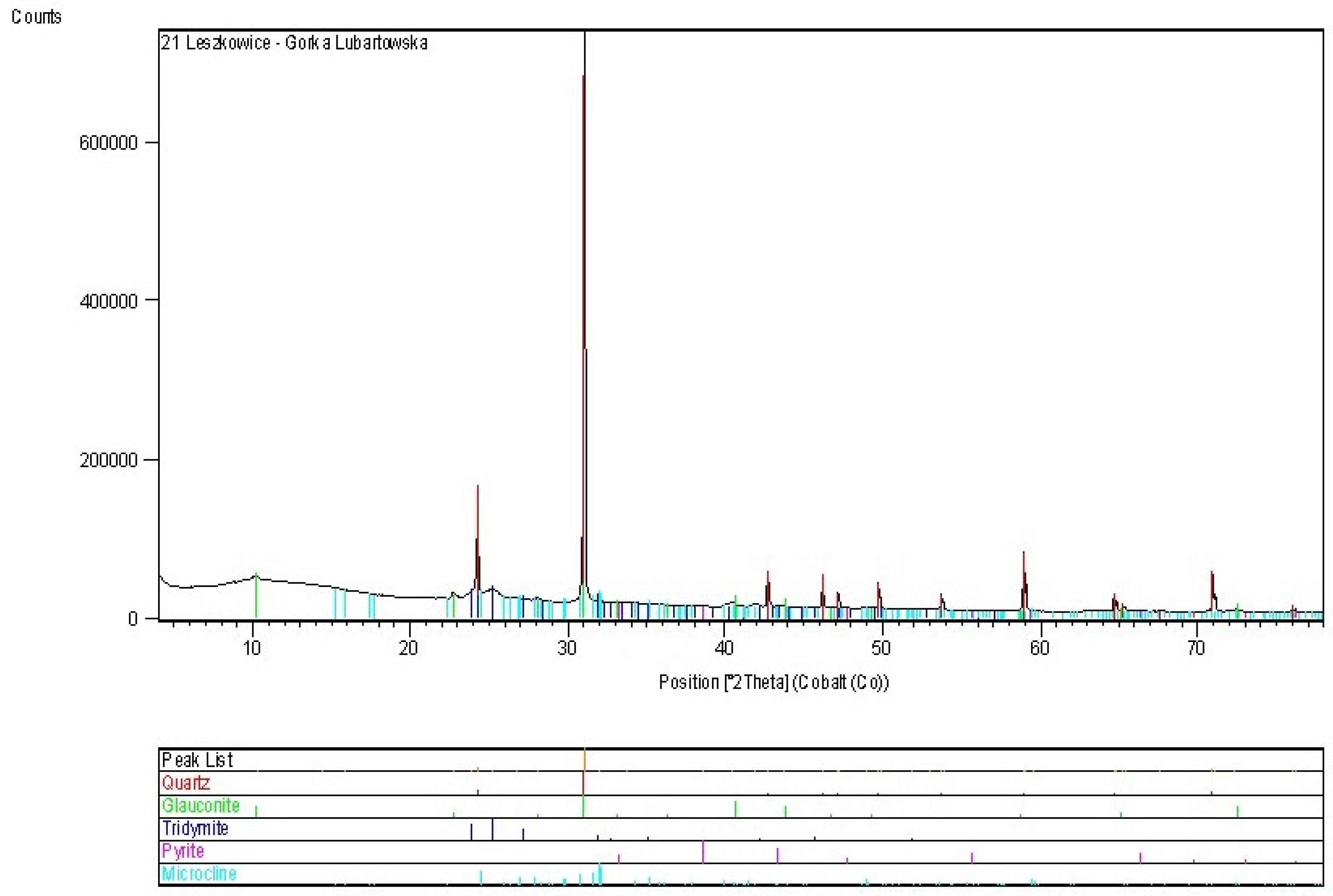

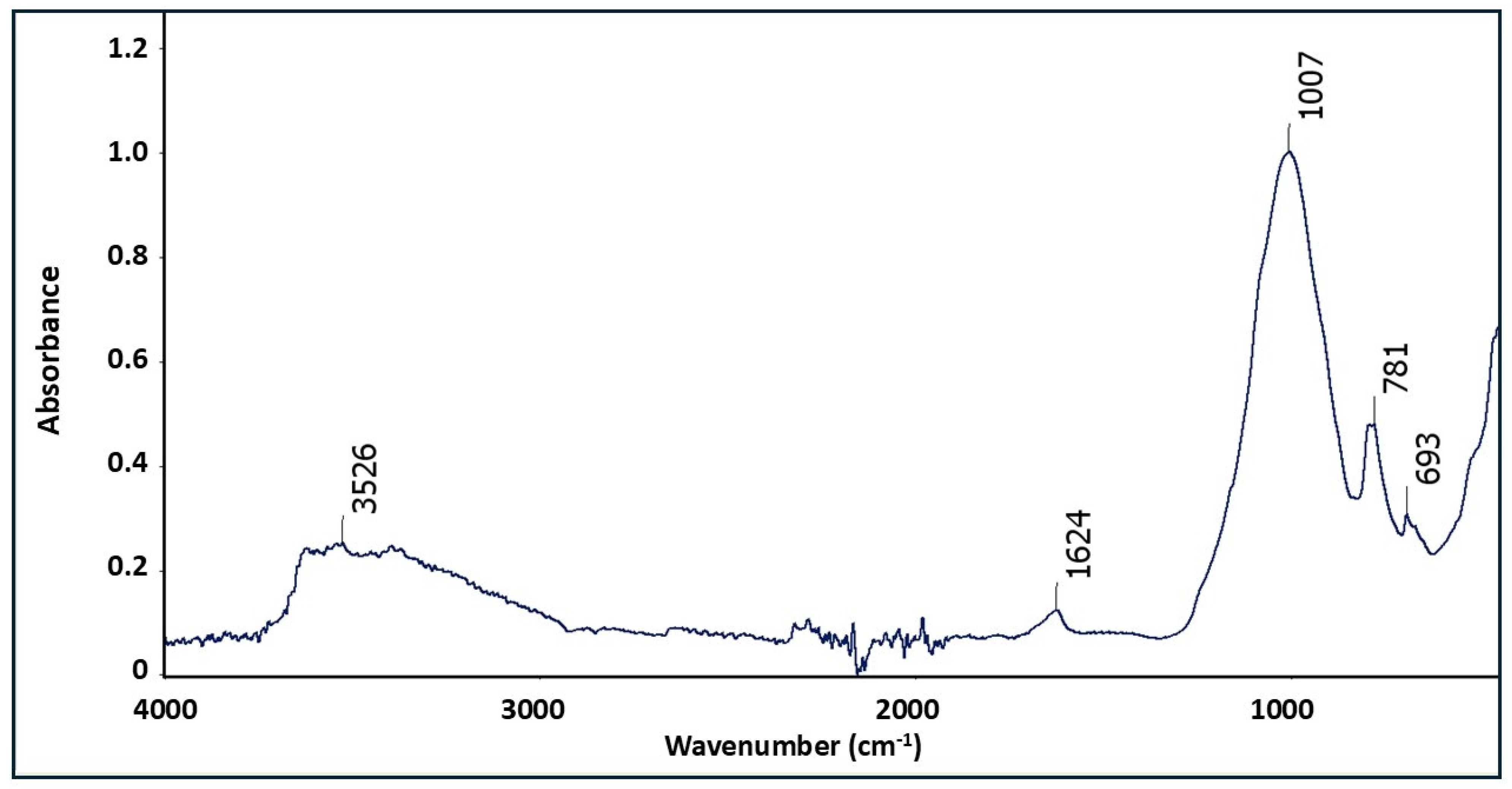

3.2. Morphology and Mineralogy

3.3. Geochemistry

4. Results

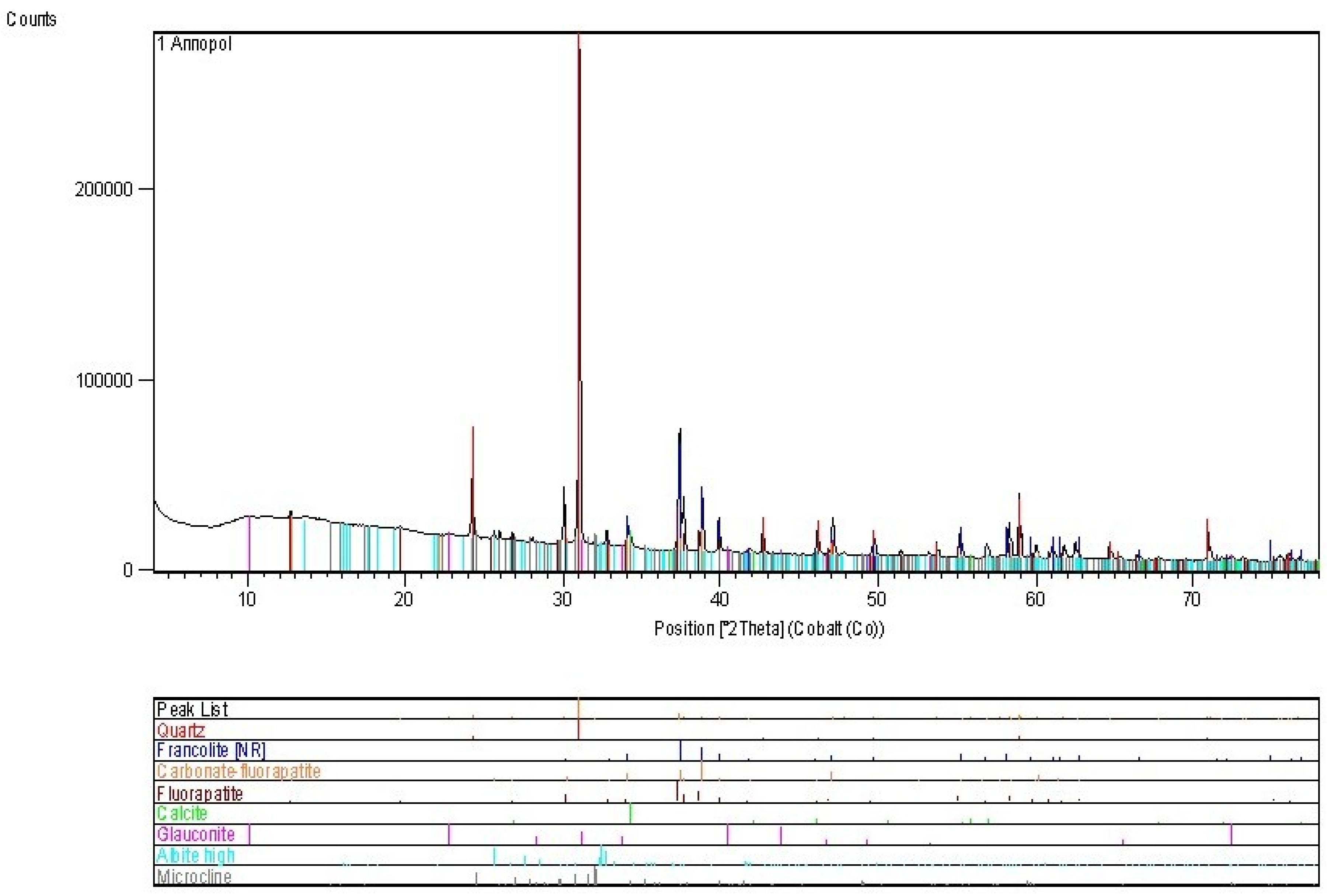

4.1. Annopol

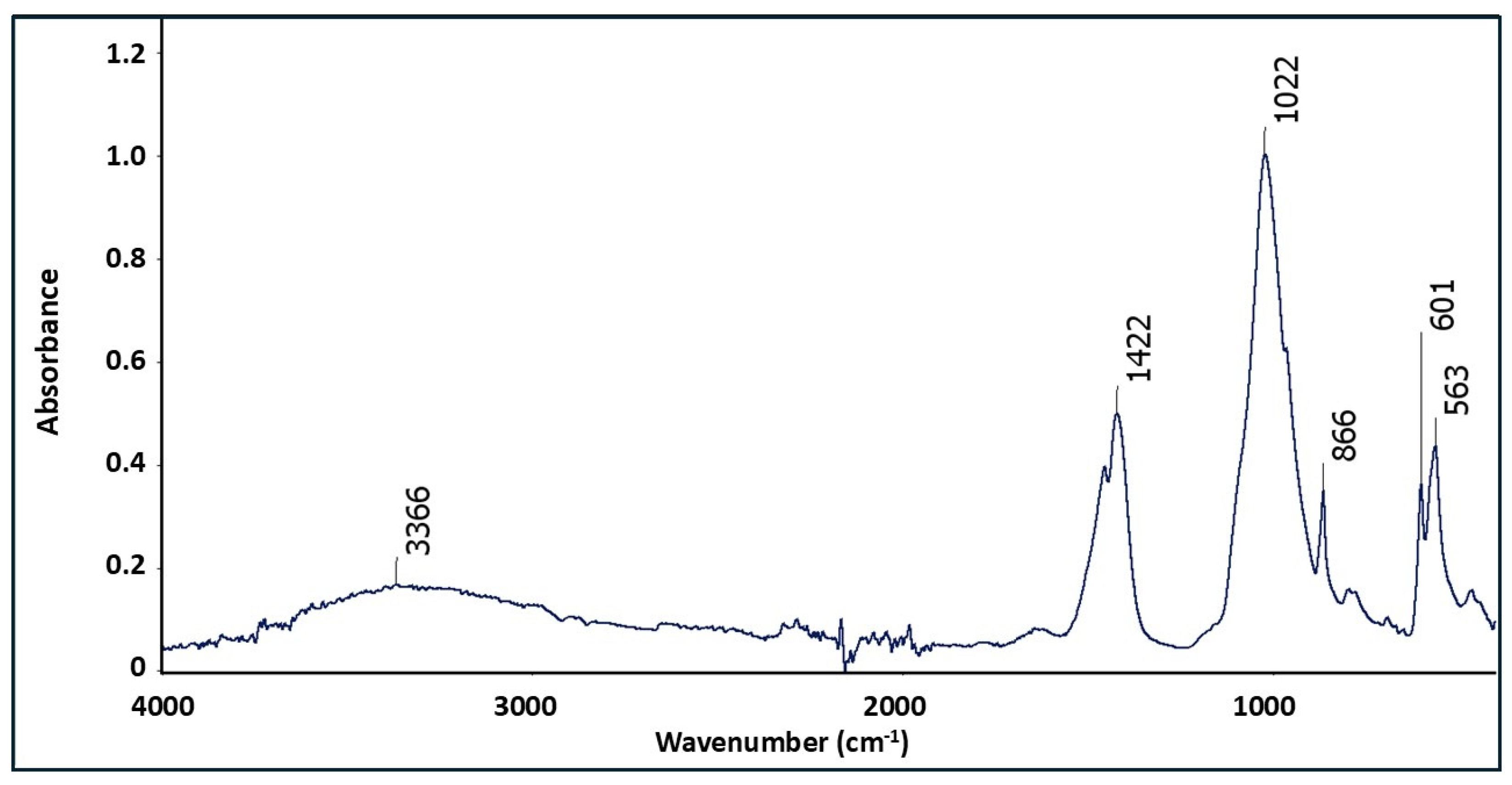

4.2. Bochotnica

4.3. Niedźwiada and Adjacent Area

5. Discussion

5.1. The Exploitation Potential of the Vistula–Bug Interfluve Phosphorite Resources

5.2. Phosphorite Resources from the Vistula–Bug Interfluve vs. Sustainable Management of P Resources in Poland

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mackey, K.R.M.; Paytan, A. Phosphorus Cycle. In Encyclopedia of Microbiology, 3rd ed.; Schaechter., M., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009; pp. 322–334. [Google Scholar]

- Ruttenberg, K.C. Phosphorus Cycle. In Encyclopedia of Ocean Sciences, 2nd ed.; Steele, J.H., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001; pp. 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitousek, P.M.; Porder, S.; Houlton, B.Z.; Chadwick, O.A. Terrestrial phosphorus limitation: Mechanisms, implications, and nitrogen–phosphorus interactions. Ecol. Appl. 2010, 20, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, B.G.; Hansen, N.C. Phosphorus Management in High-Yield Systems. J. Environ. Qual. 2019, 48, 1265–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapsalis, V.C.; Kalavrouziotis, I.K. Eutrophication—A Worldwide Water Quality Issue. In Chemical Lake Restoration; Zamparas, M.G., Kyriakopoulos, G.L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, P. Environmental Chemistry, 2nd ed.; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1993; pp. 121–126. [Google Scholar]

- Tiessen, H. Phosphorus in the global environment. In The Ecophysiology of Plant-Phosphorus Interactions: Plant Ecophysiology; White, P.J., Hammond., J.P., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008; Volume 7, pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Filippelli, G.M. The Global Phosphorus Cycle: Past, Present, and Future. Elements 2008, 4, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwick, A.E. Phosphorus mobility in perspective. In News & Views; The Potash & Phosphate Institute (PPI) and the Potash & Phosphate Institute of Canada: Saskatoon, SK, Canada, 1998; (PPIC 1–2). [Google Scholar]

- Penn, C.J.; Camberato, J.J. A Critical Review on Soil Chemical Processes that Control How Soil pH Affects Phosphorus Availability to Plants. Agriculture 2019, 9, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ptáček, P. Phosphate rocks. In Apatites and Their Synthetic Analogues-Synthesis, Structure, Properties and Applications; InTech: London, UK; Brno University of Technology: Brno, Czech Republic, 2016; pp. 335–382. [Google Scholar]

- Mullen, M.D. Phosphorus in Soils: Biological Interactions. In Encyclopedia of Soils in the Environment; Hillel, D., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruand, E.; Fowler, M.; Storey, C.; Darling, J. Apatite trace element and isotope applications to petrogenesis and provenance. Am. Mineral. 2017, 102, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, G.; Chew, D.; Kenny, G.; Henrichs, I.; Mulligan., D. The trace element composition of apatite and its application to detrital provenance studies. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2020, 201, 103044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoder, C.H.; Stepien, K.R.; Dudrick, R.N. The distribution of carbonate in apatite: The environment model. Am. Mineral. 2023, 108, 1072–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gąsiewicz, A. Phosphorites. In The Balance of Mineral Resources Deposits in Poland as of 31 December 2018; Szamałek, K., Szuflicki, M., Mizerski, W., Eds.; Państwowy Instytut Geologiczny;Państwowy Instytut Badawczy: Warszawa, Poland, 2020; pp. 233–236. [Google Scholar]

- Rutkowska, A.; Kopiński, J. Possibility of limiting phosphorus fertilization on arable land (Możliwość ograniczenia nawożenia fosforem na gruntach ornych). Stud. I Rap. JUNG-PIB 51 2022, 69, 51–61. (In Polish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmiel, S.; Głowacki, S.; Michalczyk, Z.; Sposób, J. Some issues in the assessment of eutrophication of river waters as a consequence of the construction of a storage reservoir (on the example of the Bystrzyca River). Ecohydrol. Hydrobiol. 2009, 9, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmiel, S.; Sposób, J.; Mięsiak-Wójcik, K.; Michalczyk, Z.; Głowacki, S. The Effect of a Dam Reservoir on Water Trophic Status and Forms of River Transport of Nutrients. In The Handbook of Environmental Chemistry 86, Polish River Basins and Lakes—Part I. Hydrology and Hydrochemistry; Korzeniewska, E., Harnisz, M., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmiel, S. Rola zasilania podziemnego i spływu powierzchniowego w kształtowaniu cech fizykochemicznych wód rzecznych Wyżyny Lubelskiej i Roztocza. In W: Badania Hydrograficzne w Poznawaniu Środowiska. T. 7. (The Role of Groundwater Supply and Surface Runoff in the Development of Physico-Chemical Features of River Waters in the Lublin Upland and Roztocze); UMCS: Lublin, Poland, 2005; Volume 82. [Google Scholar]

- Gebus-Czupyt, B.; Chmiel, S.; Kończak, M.; Huber, M.; Stienss, J.; Radzikowska, M.; Stępniewski, K.; Pliżga, M.; Zielińska, B. The Isotopic Composition of Selected Phosphate Sources (δ18O-PO4) from the Area of the Vistula and Bug Interfluve (Poland). Water 2024, 16, 2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amar, H.; Benzaazoua, M.; Elghali, A.; Hakkou, R.; Taha, Y. Waste rock reprocessing to enhance the sustainability of phosphate reserves: A critical review. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 381, 135151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurek, S.; Roszkowska-Remin, J.; Bieńko, T. New geological criteria for domestic phosphorite deposits—A discussion. Gospod. Surowcami Miner.—Miner. Resour. Manag. 2024, 40, 63–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bońda, R. Phosphorites. In The Balance of Mineral Resources Deposits in Poland as of 31 December 2024; Szuflicki, M., Malon, A., Tymiński, M., Eds.; Państwowy Instytut Geologiczny—Państwowy Instytut Badawczy: Warszawa, Poland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Uberna, J. Phosphorite Occurrences in Poland with Raw Technical Assessment of the Possibility of Their Use and Determination of Geological Prospecting (Występowanie Fosforytów w Polsce z Surowcowo-Techniczną Oceną Możliwości ich Wykorzystania Oraz Określeniem Perspektyw Poszukiwawczych); ObO/1820 Arch; CAG PIG: Warszawa, Poland, 1982. (In Polish)

- Dobrowolski, R.; Harasimiuk, M.; Brzezińska-Wójcik, T. Structural control on the relief in the Lublin Upland and the Roztocze region. Przegląd Geol. 2014, 62, 51–56. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Kucharska, M.; Krawczyk, M. Explanations to the Detailed Geological Map of Poland, Lubartów Sheet (713) (Objaśnienia do Szczegółowej Mapy Geologicznej Polski, Arkusz Lubartów (713)); Państwowy Instytut Geologiczny—Państwowy Instytut Badawczy: Warsaw, Poland, 2023.

- Harasimiuk, M. Structural Relief of the Lublin Upland and Roztocze. Habilitation’s Thesis, UMCS, Lublin, Poland, 1980; pp. 1–136. (In Polish). [Google Scholar]

- Michalczyk, Z.; Chmiel, S.; Głowacki, S.; Zielińska, B. Monitoring research on the springs of the Lublin Upland and Roztocze Region. Przegląd Geol. 2015, 63, 935–939. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Michalczyk, Z. (Ed.) The Springs of the Lublin Upland and Roztocze (Źródła Wyżyny Lubelskiej i Roztocza); UMCS: Lublin, Poland, 2001; pp. 1–298. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Michalczyk, Z.; Chmiel, S.; Głowacki, S.; Zielińska, B. Changes of springs’ yield of Lublin Upland and Roztocze Region in 1998–2008. J. Water Land Dev. 2008, 12, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcinowski, R.; Radwański, A. The mid-Cretaceous transgression onto the Central Polish Uplands (marginal part of the Central European Basin). Zitteliana 1983, 10, 65–96. [Google Scholar]

- Samsonowicz, J. Report on geological research in the vicinity of Rachów on the Vistula River (Sprawozdanie z badań geologicznych w okolicach Rachowa nad Wisłą). Posiedzenia Nauk. Państwowego Inst. Geol. 1924, 7, 6–7. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Pożaryski, W. Phosphorite deposit on the northeastern edge of the Holy Cross Mountains (Złoże fosforytów na północno-wschodnim obrzeżeniu Gór Świętokrzyskich). Biul. Państwowego Inst. Geol. 1947, 27, 1–56. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Cieśliński, S. Albian and Cenomanian of the northern margin of the Holy Cross Mountains (stratigraphy based on cephalopods) (Alb i cenoman północnego obrzeżenia Gór Świętokrzyskich (stratygrafia na podstawie głowonogów)). Pr. Inst. Geol. 1959, 28, 1–95. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Uberna, J. Development of the phosphorite-bearing series of the northern margin of the Świętokrzyskie Mountains in the context of Albian and Cenomanian sedimentological issues (Rozwój serii fosforytonośnej północnego obrzeżenia Gór Świętokrzyskich na tle zagadnień sedymentologicznych albu i cenomanu). Biul. Inst. Geol. 1967, 206, 5–114. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Walaszczyk, I. Mid-Cretaceous events at the marginal part of the Central European Basin (Annopol-on-Vistula section, Central Poland). Acta Geol. Pol. 1987, 37, 61–74. [Google Scholar]

- Włodek, M.; Gaździcka, E. Explanations to the Detailed Geological Map of Poland. 1:50,000. In Annopol Sheet (Objaśnienia do Szczegółowej Mapy Geologicznej Polski. 1:50,000. Arkusz Annopol); Państwowy Instytut Geologiczny—Państwowy Instytut Badawczy: Warszawa, Poland, 2009; pp. 1–51. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Machalski, M.; Olszewska-Nejbert, D.; Wilmsen, M. Stratigraphy of the Albian-Cenomanian (Cretaceous) phosphorite interval in central Poland: A reappraisal. Acta Geol. Pol. 2023, 73, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machalski, M.; Komorowski, A.; Harasimiuk, M. New perspectives for the search for marine vertebrates in the closed phosphate mine in Annopol nad Wisłą (Nowe perspektywy poszukiwań morskich kręgowców w nieczynnej kopalni fosforytów w Annopolu nad Wisłą). Przegląd Geol. 2009, 57, 638–641. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Bardet, N.; Fischer, V.; Machalski, M. Large predatory marine reptiles from the Albian–Cenomanian of Annopol, Poland. Geol. Mag. 2016, 153, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machalski, M.; Wilmsen, M. Taxonomy and taphonomy of Cenomanian (Upper Cretaceous) nautilids from Annopol, Poland. Acta Geol. Pol. 2015, 65, 495–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dubicka, Z.; Machalski, M. Foraminiferal record in a condensed marine succession: A case study from the Albian and Cenomanian (mid-Cretaceous) of Annopol, Poland. Geol. Mag. 2016, 154, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siversson, M.; Machalski, M. Late late Albian (Early Cretaceous) shark teeth from Annopol, Poland. Alcheringa Australas. J. Palaeontol. 2017, 41, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulski, S.; Brański, P.; Pienkowski, G.; Małek, R.; Zglinicki, K.; Chmielewski, A. REE enrichment of sedimentary formations in selected regions of the Mesozoic margin of the Holy Cross Mountains—Promising preliminary data and more research needed (Wzbogacenie w REE utworów osadowych w wybranych rejonach obrzeżenia mezozoicznego Gór Świętokrzyskich—Obiecujące dane wstępne i potrzeba dalszych badań). Przegląd Geol. 2021, 69, 379–385, (In Polish with English abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machowiak, K.; Huber, M.; Jastrzębski, M.; Stawikowski, W. Phosphates from Annopol (East Poland)—Preliminary results of rare earth elements analysis. Mineral. Spec. Pap. 2015, 44, 67–69. [Google Scholar]

- Dybkowska, M. Geological documentation site „Ścianka Krystyna i Władysława Pożaryskich” in Bochotnica near Kazimierz Dolny, (Geologiczne stanowisko dokumentacyjne „Ścianka Krystyny i Władysława Pożaryskich” w Bochotnicy koło Kazimierza Dolnego). Chrońmy Przyr. Ojczystą 1993, 49, 30–38, (In Polish with English Summary). [Google Scholar]

- Machalski, M. Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary in the Vistula gorge (Granica kreda-trzeciorzęd w przełomie Wisły). Przegląd Geol. 1998, 46, 1153–1161, (In Polish with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Machalski, M.; Świerczewska-Gładysz, E.; Olszewska-Nejbert, D. The end of an era: A record of events across the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary in Poland. In Cretaceous of Poland and of Adjacent Areas. Field Trip Guides; Walaszczyk, I., Todes, J., Eds.; Faculty of Geology, University of Warsaw: Warsaw, Poland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Machalski, M.; Duda, P. The influence of burrow-generated pseudobreccia on the preservation of fossil concentrations. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 18893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walaszczyk, I.; Cieśliński, S.; Sylwestrzak, H. Selected geosites of Cretaceous deposits in Central and Eastern Poland. Pol. Geol. Inst. Spec. Pap. 1999, 2, 71–76. [Google Scholar]

- Lublin Landscape Parks Unit. Available online: https://parki.lubelskie.pl/lublin-landscape-parks-unit#park-15 (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- KDG: Kamieniołom (nieczynny) w Bochotnicy. Available online: https://geostanowiska.pgi.gov.pl/gsapp_v2/2642 (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Radwanek-Bąk, B.; Bąk, B. The Middle Vistula River Section as a geotourist attraction. Przegląd Geol. 2008, 56, 639–646, (In Polish with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Natkaniec-Nowak, L.; Piestrzyński, A.; Wagner, M.; Heflik, W.; Naglik, B.; Paluch, J.; Pałasz, K.; Milovská, S.; Stach, P. “Górka Lubartowska-Niedźwiada” deposit (E Poland) as a potential source of glauconite raw material. Gospod. Surowcami Miner. 2019, 35, 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Słodkowska, B.; Kasiński, J.R.; Żarski, M. Stratigraphic and environmental conditions of the occurrence of amber-bearing deposits in the northern Lublin region (Uwarunkowania stratygraficzno-środowiskowe występowania nagromadzeń złożowych bursztynu na północnej Lubelszczyźnie). Przegląd Geol. 2022, 70, 50–60, (In Polish with English Abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Słodkowska, B.; Kasiński, J.R. Climatic and environmental conditions of Baltic amber formation (Uwarunkowania klima tyczne i środowiskowe powstawania bursztynu bałtyckiego). In Lublin Amber—Finds, Geology, Deposits, Prospects; Państwowa Wyższa Szkoła Zawodowa w Chełmie; Wydawnictwo Stellarium: Krakow, Poland, 2016; pp. 22–39. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Karnkowski, P.; Kasiński, J.; Słodkowska, B.; Czuryłowicz, K.; Żarski, M. A new approach to analysing the origin and occurrence of amber-bearing deposits of the Upper Eocene, northern Lublin area, SE Poland. Geol. Q. 2024, 68, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, P.; Fröhlich, F. Temperature dependent crystallographic transformations in chalcedony, SiO2, assessed in mid infrared spectroscopy. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2011, 78, 1476–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonakos, A.; Liarokapis, E.; Leventouri, T. Micro-Raman and FTIR studies of synthetic and natural apatites. Biomaterials 2007, 28, 3043–3054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargar, J.; Kubicki, J.; Reitmeyer, R.; Davis, J. ATR-FTIR spectroscopic characterization of coexisting carbonate surface complexes on hematite. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2005, 69, 1527–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattoraj, S.L.; Banerjee, S.; van der Meer, F.; Champati Ray, P.K. Application of visible and infrared spectroscopy for the evaluation of evolved glauconite. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2018, 64, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, M. Występowanie i charakterystyka mioceńskich piaskowców na obszarze Wyniosłości Giełczewskiej i Pagórów Chełmskich (Lubelszczyzna) (Occurrence and characteristics of the Miocene sandstones from the area of Giełczew Elevation and Chełm Hills (Lublin Region)). Ann. UMCS Geogr. Geol. Mineral. Petrogr. 2013, 68, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

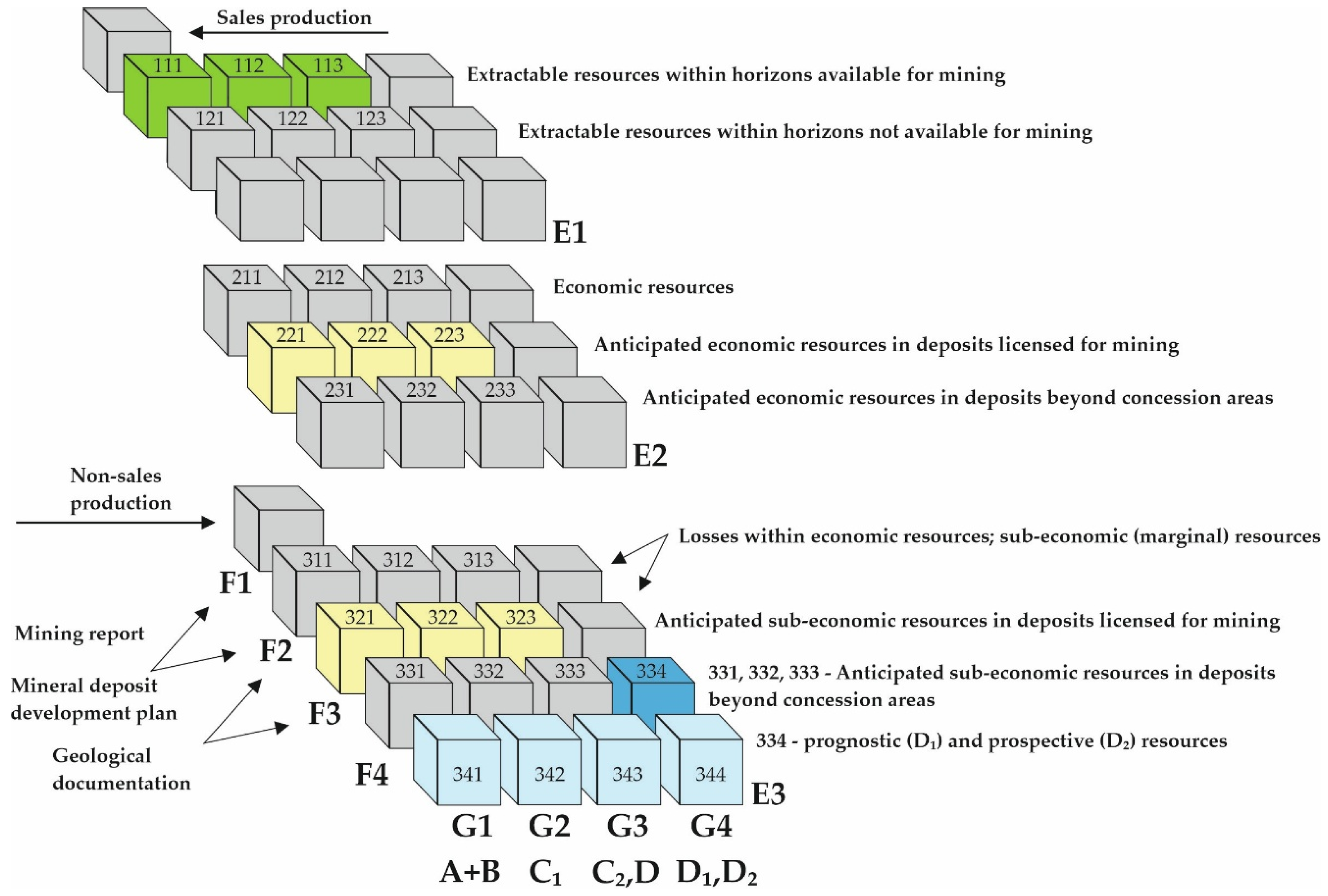

- Nieć, M. International classifications of mineral resource deposits (Międzynarodowe klasyfikacje zasobów złóż kopalin). Górnictwo I Geoinżynieria 2010, 34, 33–49. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Definitions and Explanations—PGI—NRI. Available online: https://www.pgi.gov.pl/en/mineral-resources/about-the-balance-of-mineral-resources/definitions-and-explanations.html#definitions (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Definitions and Explanations—PGI—NRI. Available online: https://www.pgi.gov.pl/en/mineral-resources/about-the-balance-of-mineral-resources/definitions-and-explanations.html#resources-categories (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Malon, A.; Tymiński, M. Classification of mineral resources. In Mineral Resources of Poland; Mazurek, S., Tymiński, M., Malon, A., Szuflicki, M., Eds.; Państwowy Instytut Geologiczny—Państwowy Instytut Badawczy: Warszawa, Poland, 2022; pp. 31–49. [Google Scholar]

- Samsonowicz, J. About the phosphate rock deposit in Rachów on the Vistula River (O złożu fosforytów w Rachowie nad Wisłą). Przegląd Górniczo-Hut. 1924, 12, 785–786. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Ptáček, P. Mining and Beneficiation of Phosphate Ore. In Apatites and Their Synthetic Analogues-Synthesis, Structure, Properties and Applications; InTech: London, UK; Brno University of Technology: Brno, Czech Republic, 2016; pp. 383–416. [Google Scholar]

- Lamghari, K.; Taha, Y.; Ait-Khouia, Y.; Elghali, A.; Hakkou, R.; Benzaazoua, M. Sustainable phosphate mining: Enhancing efficiency in mining and pre-beneficiation processes. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 358, 120833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putrym, D. Geological Documentation of Phosphorite Deposit in Krzyżanowice, Kielce Voivodeship, Iłża County (Dokumentacja Geologiczna Złoża Fosforytów w Krzyżanowicach, woj. Kieleckie, pow. Iłża); 4432/429 Arch; CAG PIG: Warszawa, Poland, 1954; Volume 43. (In Polish)

- First Phosphate Reports Initial Mineral Resource Estimate on its Bégin-Lamarche Phosphate Deposit in the Saguenay–Lac-Saint-Jean Region of Québec, Canada—First Phosphate Corp. Available online: https://firstphosphate.com/first-phosphate-reports-initial-mineral-resource-estimate-on-its-begin-lamarche-phosphate-deposit-in-the-saguenaylac-saint-jean-region-of-quebec-canada/ (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Korzeniowska, J.; Stanisławska-Glubiak, E. New trends in the use of phosphorites in agriculture (Nowe trendy w wykorzystaniu fosforytów w rolnictwie). Postępy Nauk. Rol. 2011, 3, 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Regulation 2015—Regulation of the Minister of the Environment of 1 July 2015 on the Geological Documentation of a Mineral Deposit, Excluding the Hydrocarbon Deposit (Rozporządzenie Ministra Środowiska z dnia 1 lipca 2015 r. w Sprawie Dokumentacji Geologicznej złoża Kopaliny, z Wyłączeniem złoża Węglowodorów) Journal of Laws, item 987. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20150000987 (accessed on 22 June 2025). (In Polish)

- Dar, S.A.; Balaram, V.; Roy, P.; Mir, A.R.; Javed, M.; Teja, M.S. Phosphorite deposits: A promising unconventional resource for rare earth elements. Geosci. Front. 2025, 16, 102044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, J.R.; Koschinsky, A.; Mikesell, M.; Mizell, K.; Glenn, C.R.; Wood, R. Marine Phosphorites as Potential Resources for Heavy Rare Earth Elements and Yttrium. Minerals 2016, 6, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zglinicki, K.; Szamałek, K.; Salwa, S.; Górska, I. Lower Cretaceous phosphorites from the NE margin of the Holy Cross Mountains as a potential source of REE—Preliminary studies (Dolnokredowe fosforyty z NE obrzeżenia Gór Świętokrzyskich jako potencjalne źródło REE—Badania wstępne). Przegląd Geol. 2020, 68, 566–576. (In Polish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, Y.; Fujinaga, K.; Nakamura, K.; Takaya, Y.; Kitamura, K.; Ohta, J.; Toda, R.; Nakashima, T.; Iwamori, H. Deep-sea mud in the Pacific Ocean as a potential resource for rare-earth elements. Nat. Geosci. 2011, 4, 535–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emsbo, P.; McLaughlin, P.I.; Breit, G.N.; du Bray, E.A.; Koenig, A.E. Rare earth elements in sedimentary phosphate deposits: Solution to the global REE crisis? Gondwana Res. 2015, 27, 776–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalba, G.; Liu, Y.; Schrøder, H.; Ayres, R. Global Phosphorus Flows in the Industrial Economy from a Production Perspective. J. Ind. Ecol. 2008, 12, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRae, S.G. Glauconite. Earth-Sci. Rev. 1972, 8, 397–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tribovillard, N.; Bout-Roumazeilles, V.; Abraham, R.; Ventalon, S.; Delattre, M.; Baudin, F. The contrasting origins of glauconite in the shallow marine environment highlight this mineral as a marker of paleoenvironmental conditions. Comptes Rendus Géoscience 2023, 355, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinina, N.; Maximov, P.; Makarov, B.; Dasi, E.; Rudmin, M. Characterisation and Environmental Significance of Glauconite from Mining Waste of the Egorievsk Phosphorite Deposit. Minerals 2023, 13, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, Y. The Mineralogy and Geochemistry of Phosphorites. In Phosphate Minerals; Nriagu, J.O., Moore, P.B., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godet, A.; Föllmi, K.B. Sedimentary Phosphate Deposits. In Encyclopedia of Geology, 2nd ed.; Alderton, D., Elias, S.A., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 922–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, H.J. Dating and Tracing the History of Ore Formation. In Treatise on Geochemistry, 2nd ed.; Holland, H.D., Turekian, K.K., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 87–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshino, M.; Sanematsu, K.; Watanabe, Y. Chapter: REE Mineralogy and Resources. In Handbook on the Physics and Chemistry of Rare Earths; Bünzli, J.-C., Pecharsky, V.K., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; Volume 49, pp. 129–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzowski, Z. Glaukonit z Osadów Trzeciorzędowych Regionu Lubelskiego i Możliwości Jego Wykorzystania do Analiz Geochronologicznych (Glauconite from Tertiary Sediments of the Lublin Region and the Possibilities of Its Use for Geochronological Analyses); Wydawnictwo Uczelniane Politechniki Lubelskiej: Lublin, Poland, 1995; pp. 1–130. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Wrzaszcz, W.; Zalewski, A. Economic Conditions of Fertilization in Agriculture (Ekonomiczne Uwarunkowania Nawożenia w Rolnictwie). 2024. Available online: https://www.cdr.gov.pl/images/Brwinow/aktualnosci/2024/broszura_Ekon_uwar_nawozenia.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Statistica Poland. 2022. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/wyszukiwarka/?query=tag:nawozy+mineralne (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Lewicka, E.; Burkowicz, A. (Eds.) Mineral Resources Management in Poland in 2014–2023; IGSMiE PAN: Krakow, Poland, 2024; pp. 87–90. [Google Scholar]

- Makowska, J.; Jędrzejczak, M. Historical outline of geological investigations and phosphorite mining in Annopol. Biul. Pańśtwowego Inst. Geol. 1975, 286, 65–87, (In Polish with English Summary). [Google Scholar]

- Garske, B.; Ekardt, F. Economic policy instruments for sustainable phosphorus management: Taking into account climate and biodiversity targets. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2021, 33, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, A.N.; Daniel, T.C.; Gibson, G.; Bundy, L.; Cabrera, M.; Sims, T.; Stevens, R.; Lemunyon, J.; Kleinman, P.J.A.; Parry, R. Best Management Practices to Minimize Agricultural Phosphorus Impacts on Water Quality. In USDA-ARS Publication; U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; Volume 163. [Google Scholar]

- Randall, G.; Vetsch, J. Optimum placement of phosphorus for corn/soybean rotations in a strip-tillage system. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2008, 63, 152A–153A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, R.W.; Roy, A.H.; Brand, F.S.; Hellums, D.T.; Ulrich, A.E. (Eds.) Sustainable Phosphorus Management A Global Transdisciplinary Roadmap; Springer Science+Business Media: Dordrecht, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Liu, J.; Li, G.; Shen, J.; Bergström, L.; Zhang, F. Past, present, and future use of phosphorus in Chinese agriculture and its influence on phosphorus losses. AMBIO 2015, 44 (Suppl. 2), 274–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, T.L.; Johnston, A.E. Phosphorus use efficiency and management in agriculture. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 105 Pt B, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoumans, O.F.; Bouraoui, F.; Kabbe, C.; Oene, O.; Van Dijk, K. Phosphorus management in Europe in a changing world. AMBIO 2015, 44 (Suppl. 2), 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smol, M.; Marcinek, P.; Šimková, Z.; Bakalár, T.; Hemzal, M.; Klemeš, J.J.; Fan, Y.V.; Lorencz, K.; Koda, E.; Podlasek, A. Inventory of Good Practices of Sustainable and Circular Phosphorus Management in the Visegrad Group (V4). Resources 2023, 12, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorazda, K.; Tarko, B.; Wzorek, Z.; Kominko, H.; Nowak, A.; Kulczycka, J.; Henclik, A.; Smol, M. Fertilisers production from ashes after sewage sludge combustion—A strategy towards sustainable development. Environ. Res. 2017, 154, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorazda, K.; Tarko, B.; Wzorek, Z.; Nowak, A.K.; Kulczycka, J.; Henclik, A. Characteristic of wet method of phosphorus recovery from polish sewage sludge ash with nitric acid. Open Chem. 2016, 14, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorazda, K.; Wzorek, Z.; Tarko, B.; Nowak, A.; Kulczycka, J.; Henclik, A. Phosphorus cycle—Possibilities for its rebuilding. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2013, 60, 725–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witek-Krowiak, A.; Gorazda, K.; Szopa, D.; Trzaska, K.; Moustakas, K.; Chojnacka, K. Phosphorus recovery from wastewater and bio-based waste: An overview. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 13474–13506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Helfenstein, J.; Ringeval, B.; Tamburini, F.; Mulder, V.L.; Goll, D.S.; He, X.; Alblas, E.; Wang, Y.; Mollier, A.; Frossard, E. Understanding soil phosphorus cycling for sustainable development: A review. One Earth 2024, 7, 1727–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, J.; Abraham, M.; Amelung, W.; Baum, C.; Bol, R.; Kühn, O.; Lewandowski, H.; Niederberger, J.; Oelmann, Y.; Rüger, C.; et al. Innovative methods in soil phosphorus research: A review. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2015, 178, 43–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogwu, M.; Patterson, M.; Senchak, P. Phosphorus mining and bioavailability for plant acquisition: Environmental sustainability perspectives. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2025, 197, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.B.; Sayyed, R.Z.; Trivedi, M.H.; Gobi, T.A. Phosphate solubilizing microbes: Sustainable approach for managing phosphorus deficiency in agricultural soils. SpringerPlus 2013, 2, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrow, N.J.; Lambers, H. Role of microorganisms in phosphorus uptake. Plant Soil 2022, 476, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantigoso, H.A.; Newberger, D.; Vivanco, J.M. The rhizosphere microbiome: Plant-microbial inter actions for resource acquisition. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 133, 2864–2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steidinger, B.; Crowther, T.W.; Liang, J.; Nuland, M.E.; Werner, G.D.A.; Reich, P.; Nabuurs, G.-J.; de-Miguel, S.; Zhou, M.; Picard, N.; et al. Climatic controls of decomposition drive the global biogeography of forest-tree symbioses. Nature 2019, 569, 404–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Zhou, L.; Chen, Y.; Liu, R.; Guo, L.; Li, N.; Kang, A.; Zhai, K.; Zhou, G.; Zhou, X. Ectomycorrhizal fungi explain more variation in rhizosphere nutrient availability than root traits in temperate forests. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2025, 207, 105923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samreen, S.; Kausar, S. Phosphorus Fertilizer: The Original and Commercial Sources. Phosphorus Recovery Recycl. 2019, 81, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annis, P.C. Chemicals for Grain Production and Protection, Reference Module in Food Science; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, A. Chapter 5: Changing Environmental Condition and Phosphorus-Use Efficiency in Plants. In Changing Climate and Resource Use Efficiency in Plants; Bhattacharya, A., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 241–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkaczyk, P.; Bednarek, W. Assessment of soil pH in the Lublin region (Ocena odczynu gleb Lubelszczyzny). Acta Agrophysica 2011, 18, 173–186. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Rutkowska, A.; Skowron, P. Productive and environmental consequences of sixteen years of unbalanced fertilization with nitrogen and phosphorus—Trials in Poland with oilseed rape, wheat, maize and barley. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochal, P. Current status and changes in soil fertility in Poland (Aktualny stan i zmiany żyzności gleb w Polsce). Stud. I Rap. JUNG-PIB 2015, 45, 9–25. [Google Scholar]

- Gorlach, E. Soil and its role in plant nutrition and fertilization (Gleba i jej rola w odżywianiu roślin i nawożeniu). In Chemia rolna; Gorlach, E., Mazur, T., Eds.; Wydawnictwa Naukowe PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2002; pp. 73–127. [Google Scholar]

- Sapek, B. Accumulation and release of phosphorus in soils—Sources, processes, causes (Nagromadzanie i uwalnianie fosforu w glebach—źródła, procesy, przyczyny). Woda-Sr.-Obsz. Wiej. 2014, 14, 77–100. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Tujaka, A.; Gosek, S. Phosphorus utilization depending on the dose size and form of phosphorus fertilizer (Wykorzystanie fosforu w zależności od wielkości dawki i formy nawozu fosforowego). Fragm. Agron. 2009, 26, 158–164. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, M. Explanations to the Geo-Environmental Map of Poland. 1:50,000. Annopol Sheet (Objaśnienia do Mapy Geośrodowiskowej Polski. 1:50,000. Arkusz Annopol); Państwowy Instytut Geologiczny—Państwowy Instytut Badawczy: Warszawa, Poland, 2006; pp. 1–51. (In Polish)

- Dasi, E.; Rudmin, M.; Banerjee, S. Glauconite applications in agriculture: A review of recent advances. Appl. Clay Sci. 2024, 253, 107368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Deposit | Economic Geological Resources [Thousand Tonnes] | Sub-Economic Resources [Thousand Tonnes] | Thickness [m] | Phosphorite Concretion Diameter [mm] | P2O5 Content [%] | Affluence of Phosphorite Concretions [kg/m2] | Affluence in Relation to Actual Limiting Parameters [%] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | A + B | C1 | C2 | |||||||

| Annopol | 7600 1030 | 4600 630 | 2980 400 | - | - | 0.3 | >10 | 13.5 | 568 | 32 |

| Burzenin | - | - | - | - | 2740 490 | 0.7 | >2 | 18.1 | 385 | 21 |

| Chałupki | 3170 440 | 150 20 | 3020 420 | - | - | 0.4 | >10 | 14.9 | 354 | 21 |

| Gościeradów | 1420 210 | - | - | 1420 210 | - | no data | >2 | 15.2 | 496 | 28 |

| Iłża–Krzyżanowice | 1860 390 | - | - | 1860 390 | 860 115 | 1.3 | >2 | 18.6 | 791 | 44 |

| Iłża–Chwałowice | 620 140 | - | - | 620 140 | 625 90 | 0.4 | >2 | 22.3 | 891 | 50 |

| Iłża–Łęczany | 10,230 1900 | - | - | 10,230 1900 | 1340 257 | 0.6 | >2 | 18.6 | 654 | 36 |

| Iłża–Walentynów | 1690 330 | - | - | 1690 330 | - | 0.7 | >2 | 19.9 | 470 | 26 |

| Radom– Dąbrówka Warszawska | 6760 1210 | - | - | 6760 1210 | - | 1.8 | >2 | 16.5 | upper series—317 lower series—460 | upper series—18 lower series—26 |

| Radom– Krogulcza | 8470 1610 | - | - | 8470 1610 | 3114 592 | 0.5 | >2 | 19.1 | upper series—218 lower series—504 | upper series—12 lower series—28 |

| Radom– Wolanów | 590 90 | - | - | 590 90 | 98 19 | 0.7 | >2 | 15.4 | upper series—170 lower series—447 | upper series—9 lower series—25 |

| Name of Deposit | The State of Development | Geological Resources in Place [Thousand Tonnes] | Economic Resources in Place as a Part of Anticipated Economic Resources | Output | Localization | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anticipated Economic | Anticipated Sub-Economic | |||||||||

| Total | A + B | C1 | C2 | D | ||||||

| Total number of deposits: 1 | 8.04 | - | 8.04 | - | - | - | - | - | Lublin Voivodeship, Lubartów County | |

| Niedźwiada II | R | 8.04 | - | 8.04 | - | - | - | - | - | Lublin Voivodeship, Lubartów County |

| Management of Natural Calcium Phosphates in Poland [in 106 kg] | ||||||||||

| Year | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

| Import | 1265.2 | 1249.7 | 1313.2 | 1213.1 | 1172.6 | 1324.6 | 1175 | 148.1 | 162.9 | 107.7 |

| Export | 0.6 | 1.6 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 1.5 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 |

| Management of elemental phosphorus in Poland [in 106 kg] | ||||||||||

| Year | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

| Import | 27.4 | 22.8 | 20.7 | 26.3 | 30.3 | 24.9 | 28 | 29.5 | 22.3 | 14.2 |

| Export | 9.3 | 8.2 | 8 | 9.8 | 9.9 | 9.9 | 8.4 | 10.8 | 10.4 | 5.9 |

| Value of trade in natural calcium phosphates in Poland [in thousands of PLN *] | ||||||||||

| Year | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

| Import | 1000 | 1225 | 575 | 25 | 32 | 110 | 301 | 29 | 55 | 1 |

| Export | 391,794 | 463,617 | 448,897 | 358,319 | 343,879 | 44,295 | 359,319 | 58,540 | 126,181 | 70,003 |

| Value of trade in elemental phosphorus in Poland [in thousands of PLN *] | ||||||||||

| Year | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

| Import | 99,041 | 104,360 | 96,354 | 113,623 | 104,445 | 113,173 | 100,055 | 132,101 | 243,133 | 122,575 |

| Export | 269,613 | 267,941 | 227,907 | 255,779 | 279,710 | 255,390 | 287,628 | 297,722 | 475,679 | 216,187 |

| Average unit values of import of natural calcium phosphates to Poland [in PLN */t] | ||||||||||

| Year | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

| Natural calcium phosphates, unground | 308 | 370 | 340 | 293 | 292 | 335 | 316 | 369 | 827 | 655 |

| Natural calcium phosphates, ground | 325 | 376 | 368 | 323 | 303 | 407 | 219 | 418 | 748 | 647 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gebus-Czupyt, B.; Huber, M.; Stienss, J.; Brancaleoni, G.; Hryciuk, J.; Maciołek, U.; Siwek, K.; Chmiel, S. The Potential of the Vistula–Bug Interfluve Resources in the Context of the Sustainable Management of Non-Renewable Phosphorus Resources in Poland. Resources 2025, 14, 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources14120182

Gebus-Czupyt B, Huber M, Stienss J, Brancaleoni G, Hryciuk J, Maciołek U, Siwek K, Chmiel S. The Potential of the Vistula–Bug Interfluve Resources in the Context of the Sustainable Management of Non-Renewable Phosphorus Resources in Poland. Resources. 2025; 14(12):182. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources14120182

Chicago/Turabian StyleGebus-Czupyt, Beata, Miłosz Huber, Jacek Stienss, Greta Brancaleoni, Joanna Hryciuk, Urszula Maciołek, Krzysztof Siwek, and Stanisław Chmiel. 2025. "The Potential of the Vistula–Bug Interfluve Resources in the Context of the Sustainable Management of Non-Renewable Phosphorus Resources in Poland" Resources 14, no. 12: 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources14120182

APA StyleGebus-Czupyt, B., Huber, M., Stienss, J., Brancaleoni, G., Hryciuk, J., Maciołek, U., Siwek, K., & Chmiel, S. (2025). The Potential of the Vistula–Bug Interfluve Resources in the Context of the Sustainable Management of Non-Renewable Phosphorus Resources in Poland. Resources, 14(12), 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources14120182