Using Outsourcing Services in Manufacturing Companies

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Restorative—used by economic entities threatened with liquidation or in crisis,

- adaptive—used by economic entities that want to develop, be competitive and become market leaders,

- developmental—includes strategic decisions and activities of a developmental or innovative nature; in its essence, it favours the use of the company’s market capabilities and opportunities while limiting all threats.

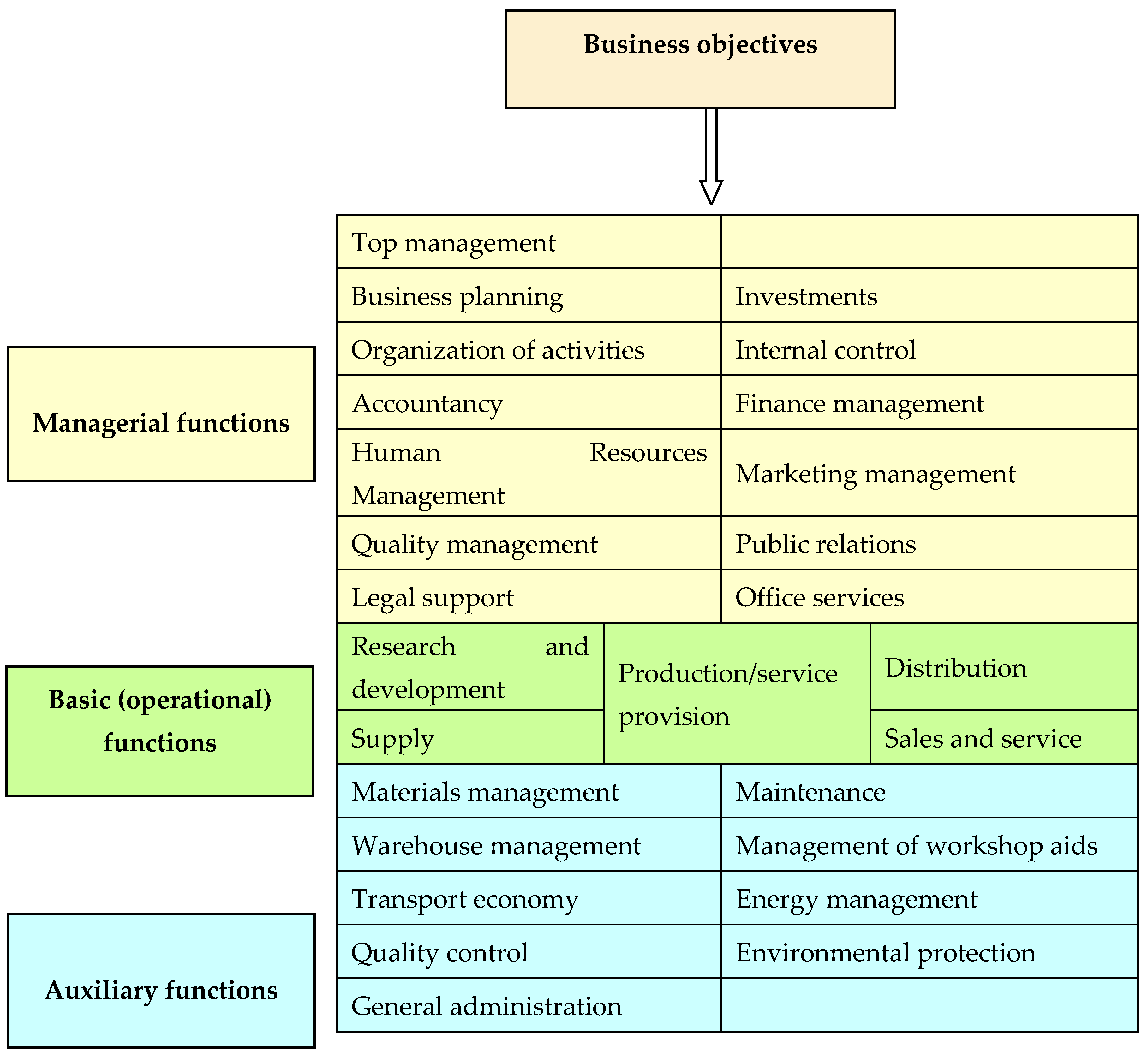

- basic;

- auxiliary (complementary);

- managerial.

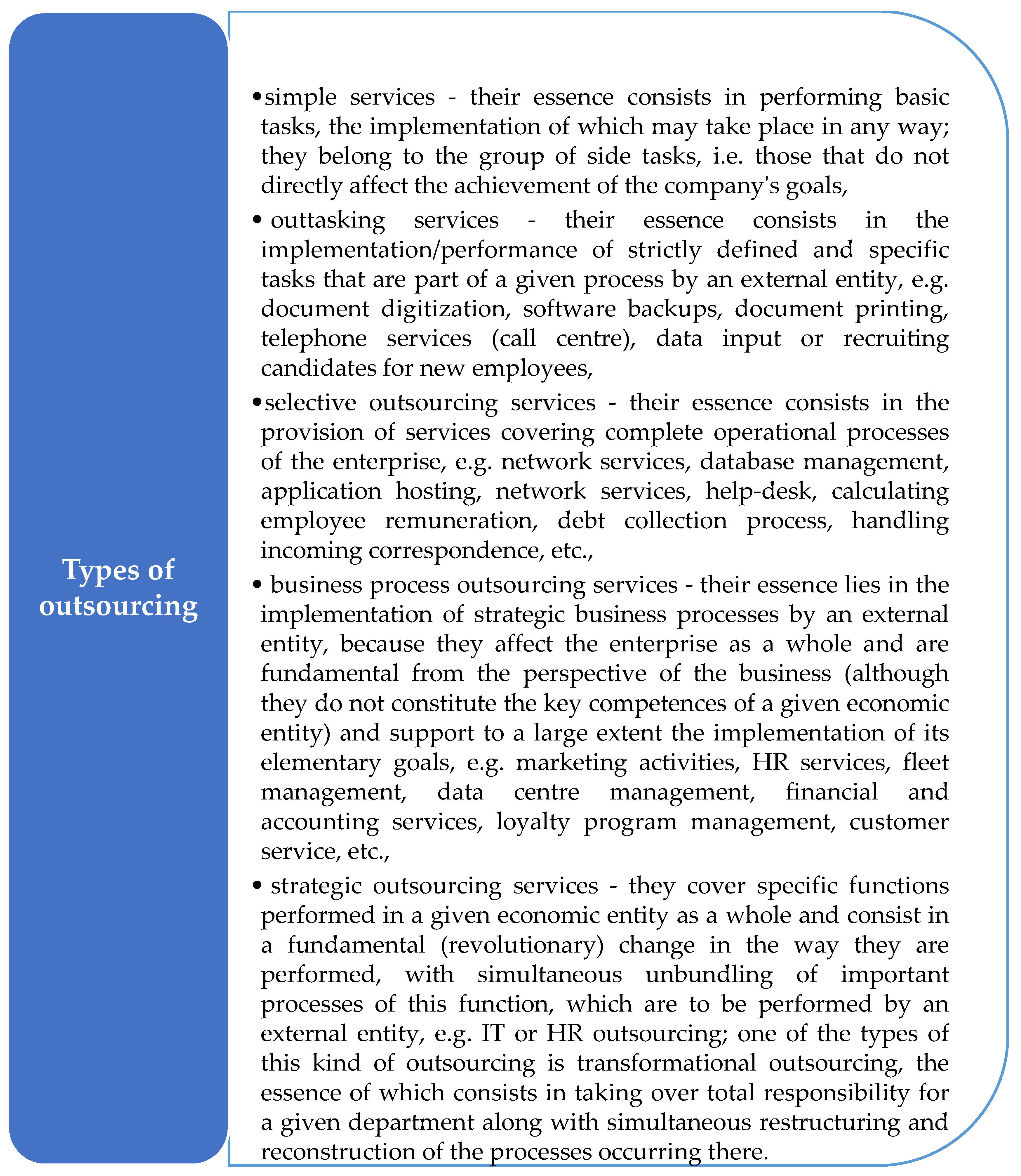

- location;

- depth;

- work.

- individual—includes individual workstations,

- functional—includes specific functions/fields of activity,

- competence—includes outsourcing activities with simultaneous decision-making by an external entity (contractor).

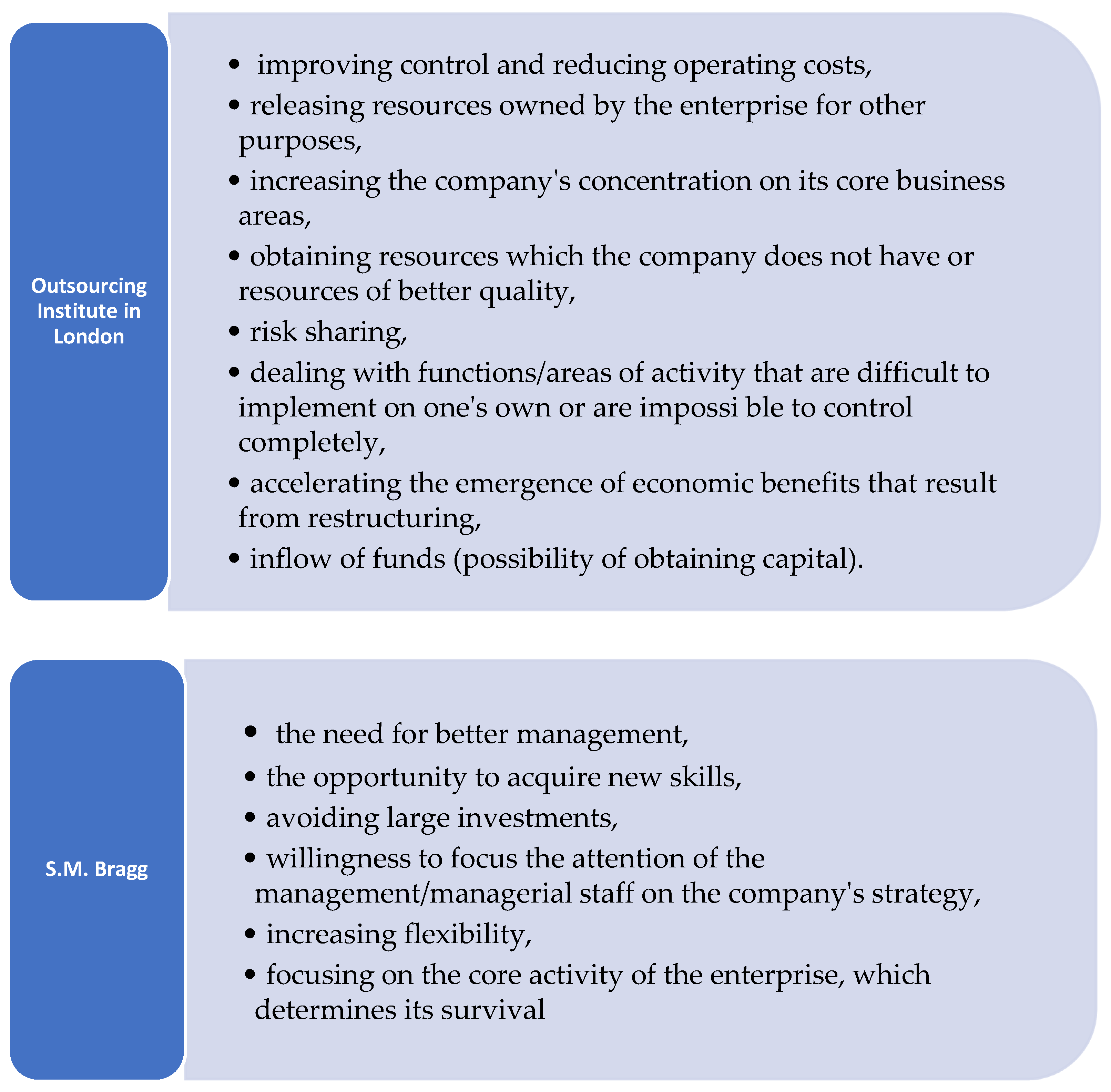

2. The Review of Literature

- business benefits that include an analysis of the key competences of a given economic entity (they constitute a component of products and/or services produced/offered by a given enterprise and distinguish them from market competitors); supplementary competences are, in turn, necessary to conduct the current activity of the enterprise and have an indirect impact on the products and services it provides;

- operational assessment—essentially consists in diagnosing whether a given enterprise has scenarios that can support outsourcing projects, and whether it has appropriate comparative data and measurement methods that can be used to assess the condition of the economic entity and the competitiveness of the offer presented;

- financial assessment, which should show a direct link with the prerequisites for the use of outsourcing in a given economic entity; in a situation where the basic reason for the use of outsourcing are the costs of fulfilling a function or the costs of implementing selected areas of the company’s operations, then it is necessary to conduct a cost analysis;

- risk analysis regarding possible interactions between a given company and an external entity (potential supplier); it is necessary in this case to conduct a risk analysis in the financial, operational and technological context.

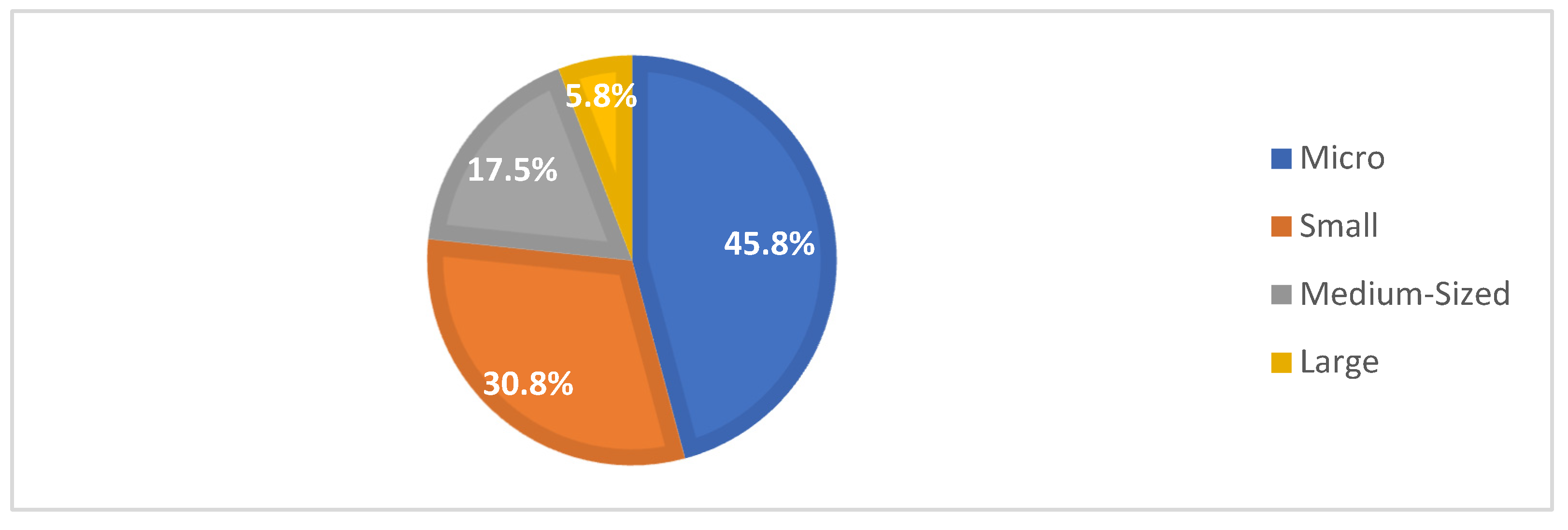

3. Research Methodology

- a preparatory stage consisting of activities related to the determination of the subject, problem, goal and hypotheses of the study, including the development of questions for the questionnaire;

- the stage of the research implementation, including acquiring subjects as well as conducting the study itself;

- the stage of analysis of the obtained research results and their interpretation.

- The survey questionnaire included the following parts:

- introduction, in which there was a request to participate in the study along with the presentation of the purpose of the study plus ensuring anonymity;

- the proper part intended for enterprises using outsourcing services, in which there were six closed questions;

- a certificate with four closed questions.

4. Discussion

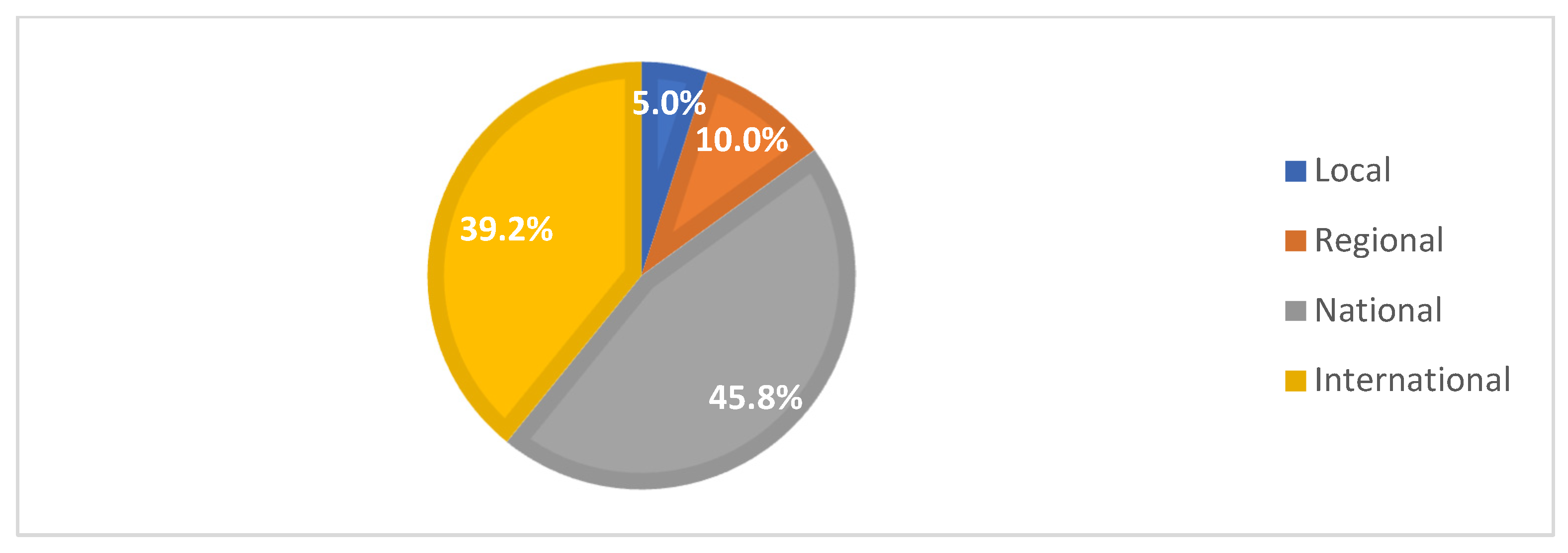

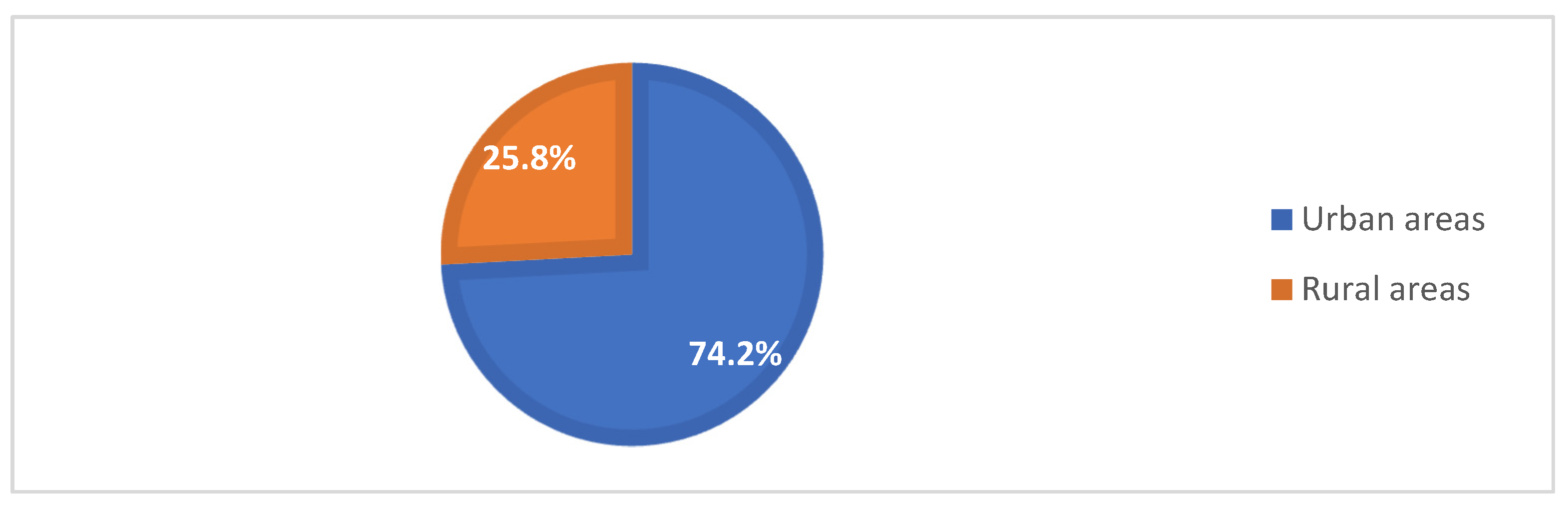

- geographical criteria (country of the ordering party, country belonging to the European Union, country located on another continent);

- the supplier’s scale of operation (small—local, medium—regional/national, large—international, very large—global);

- specialization (process work or performing tasks in the form of projects, implementations);

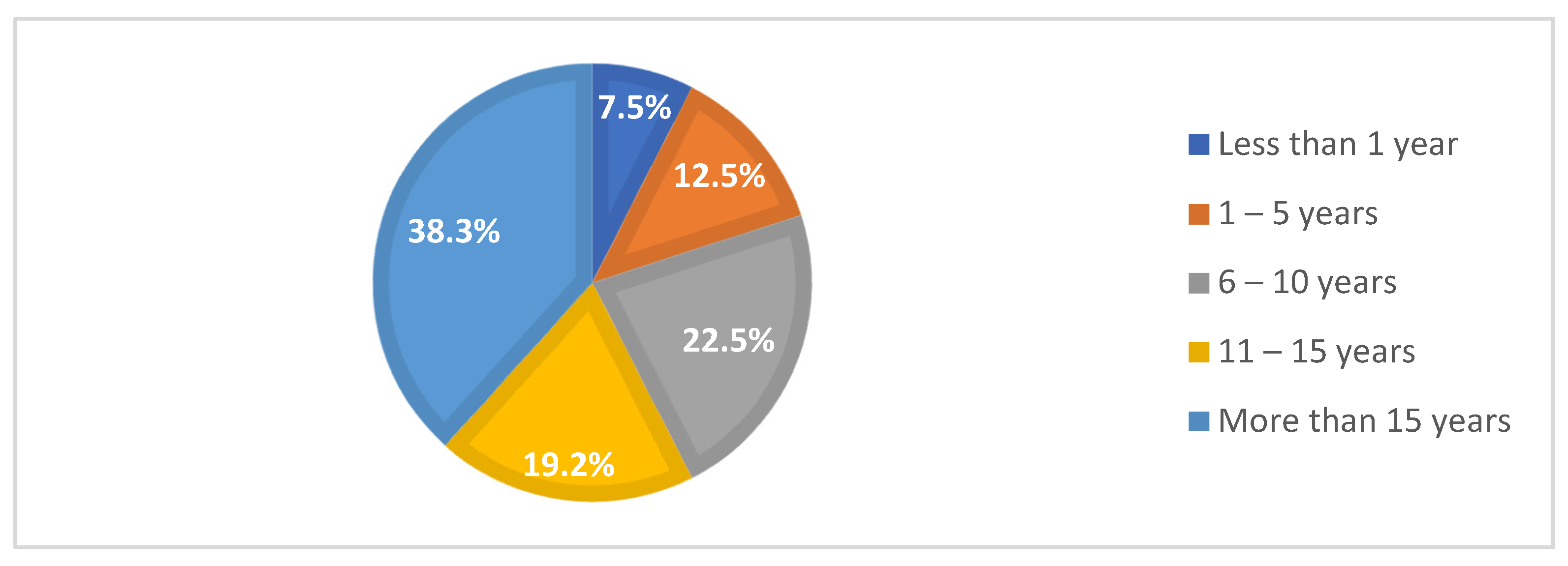

- experience in providing outsourcing services;

- resources owned by the supplier (production or service capacity, necessary knowledge for the implementation of outsourcing projects).

- selection of adequate indicators (economic, financial and other) so that they reflect the studied phenomenon/area as accurately as possible;

- determining threshold and optimal values of individual indicators;

- determining the frequency of developing individual indicators;

- determining the manner in which individual indicators will be calculated;

- development of an IT system that will be used to calculate the indicators;

- establishing the procedures used to interpret the level (value) of individual indicators; benchmarking can also be used in this case;

- definition of source (primary) information with the methods of obtaining it; it is necessary in order to calculate individual reflecting indicators;

- establishing scenarios of conduct in the case of different levels (values) of indicators (positive and negative).

- the company–client should receive compensation for the external entity–contractor’s failure to meet the specified terms of the contract (e.g., the date and method of delivery or quality) on the delivery of the outsourcing service;

- the penalty for the external entity–outsourcing service provider is aimed at persuading them to pay more attention and care to the proper quality of services in the future.

- establishing the criteria on the basis of which the outsourcing agreement with the service provider-contractor will be extended;

- establishing the criteria on the basis of which the outsourcing contract may be terminated.

5. Research Results

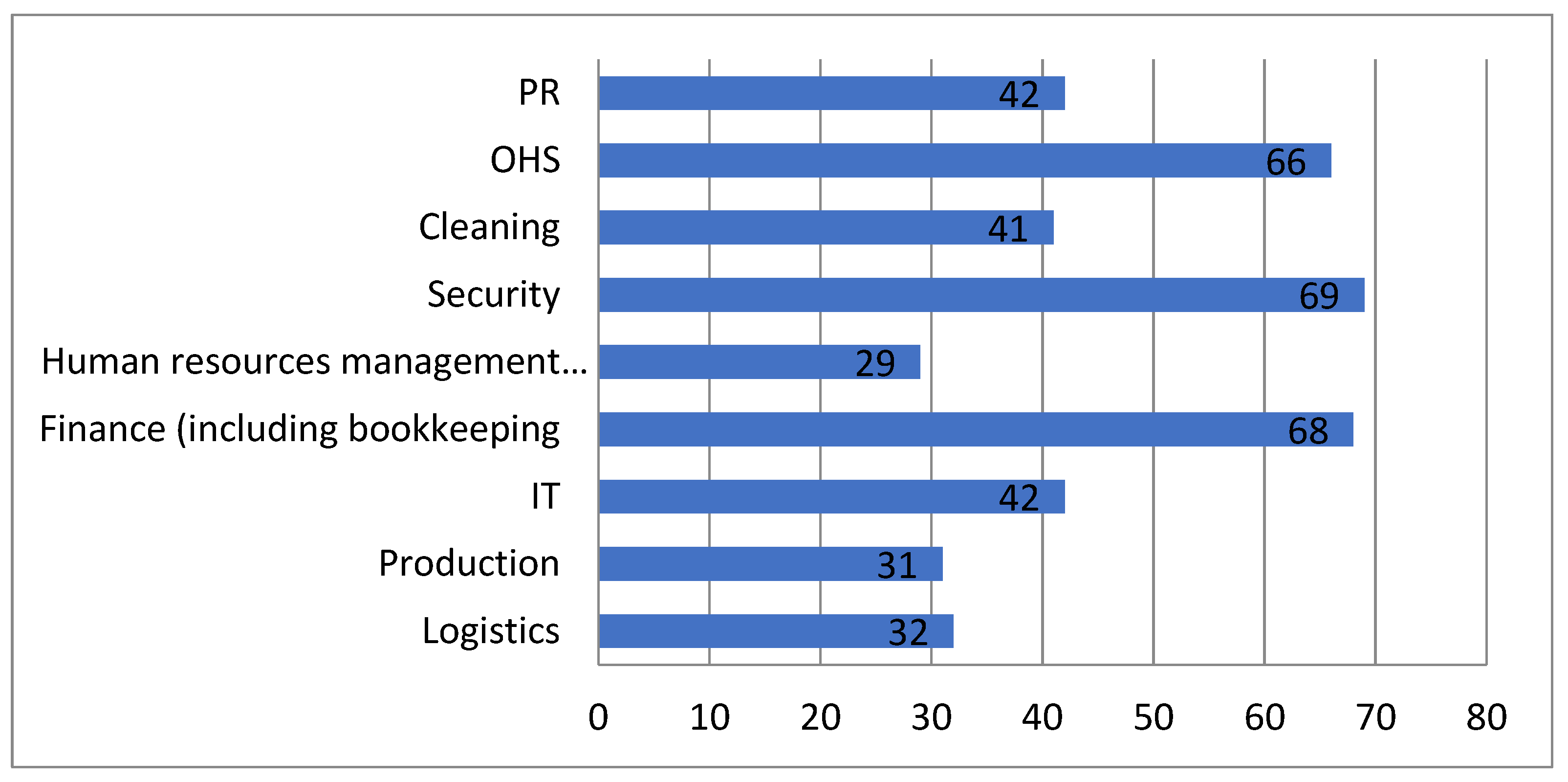

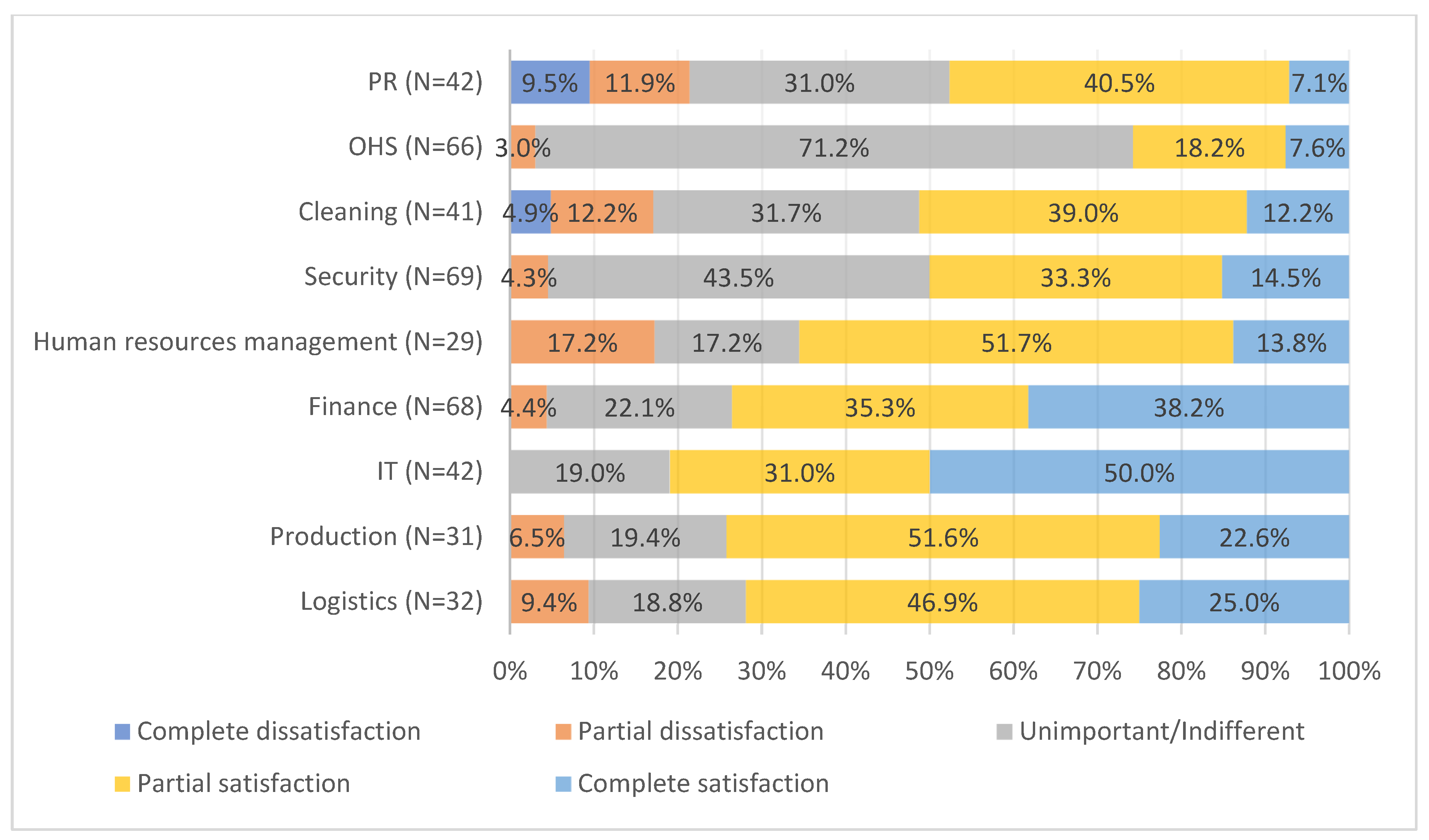

- security, which is outsourced to external entities by 88.5% of companies using outsourcing (69 entities);

- finances (including bookkeeping), which are outsourced to external entities by 87.2 percent enterprises using outsourcing (68 entities);

- OHS, which is outsourced by 84,6% of companies using outsourcing (66 entities).

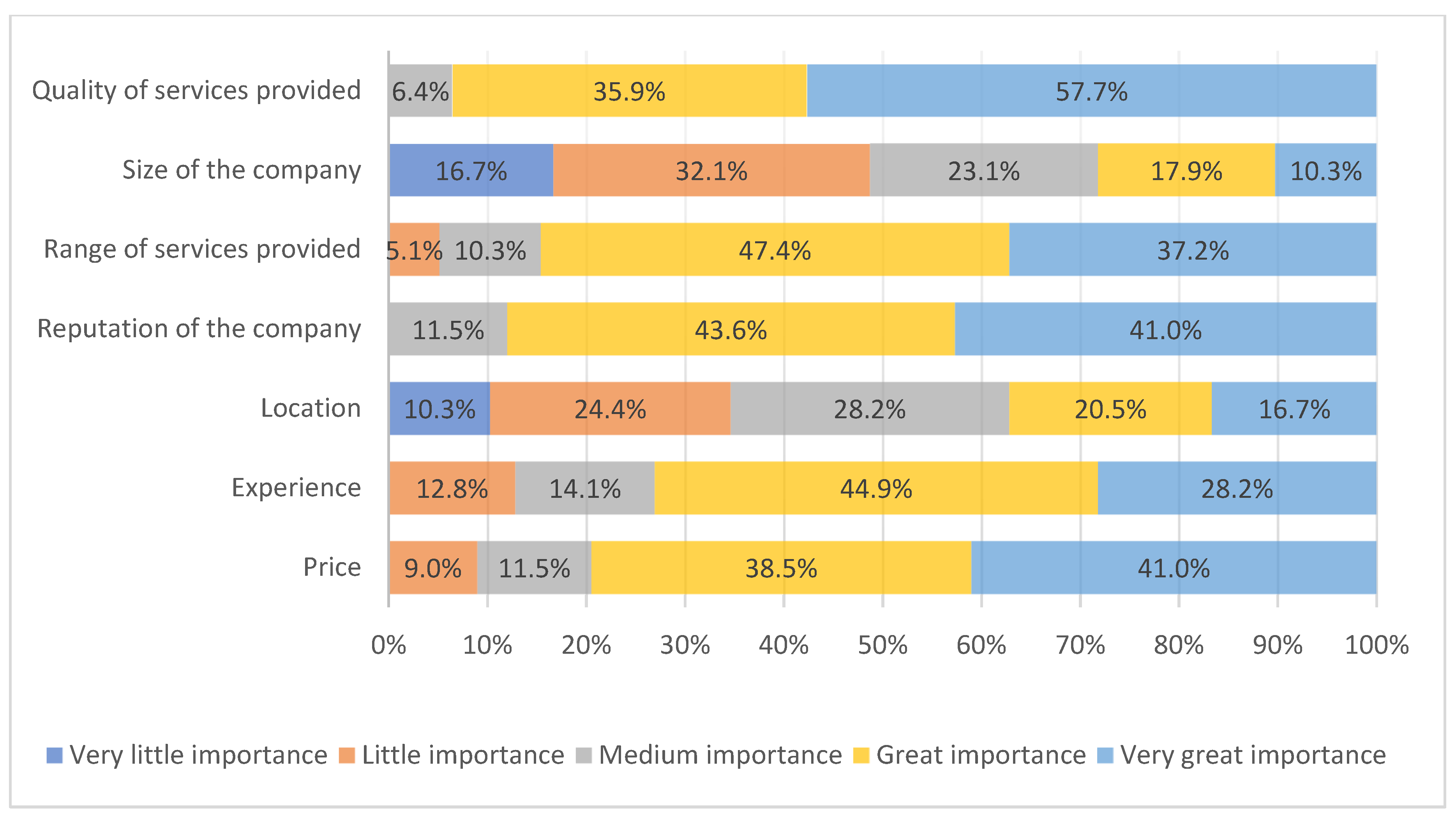

- quality of services provided (average answer—4.51, mode 5);

- range of services provided (average answer—4.17, mode 4);

- reputation of the outsourcing company (average answer—4.14, mode 4);

- price (average answer—4.12, mode 5).

6. Conclusions

- the most frequently used outsourcing services are financial and security services;

- the choice of an outsourcing service provider is influenced by the price and quality of the services provided.

- on the theoretical level:

- ○

- broadening and systematising the knowledge of outsourcing business activities to external entities;

- on the empirical level:

- ○

- identification of key determinants affecting the choice of the outsourcing service provider

- ○

- verification of the relationship between the choice of the service provider and the price and quality of services provided

- on the practical level:

- ○

- supporting entrepreneurs in conscious and effective planning and implementation of outsourcing services by disseminating research findings (final conclusions).

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Halim, H.A.; Ahmad, N.H.; Ho, T.C.F.; Ramayah, T. The Outsourcing Dilemma on Decision to Outsource Among Small and Medium Enterprises in Malaysia. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2017, 18, 348–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilley, K.M.; Rasheed, A.A. Making more by doing less: An analyzing of outsourcing and its effects on firm performance. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 763–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysons, K.; Farrington, B. Purhasing and Supply Chain Management; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bilan, Y.; Nitsenko, V.; Ushkarenko, I.; Chmut, A.; Sharapa, O. Outsourcing in International Economic Relations. Montenegrin J. Econ. 2017, 13, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, M. Logistics outsourcing: A structured literature review. Benchmarking Int. J. 2018, 25, 1548–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens-Schmid, K. Coaching als Beratungssystem—Grundlagen, Konzepte, Methoden; Economia Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Harkins, P.J.; Brown, S.M.; Sullivan, R. Outsourcing and Human Resources: Trends, Models, and Guidelines; LER Press: Lexington, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Romero, M.; Sandefur, J.; Sandholtz, W.A. Outsourcing Education: Experimental Evidence from Liberia. Am. Econ. Rev. 2020, 110, 364–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damanpour, F.; Magelssen, C.; Walker, R.M. Outsourcing and insourcing of organizational activities: The role of outsourcing process mechanisms. Public Manag. Rev. 2019, 22, 767–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, M.E.; Hefetz, A. Insourcing and outsourcing. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2012, 78, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Bary, B.; Westner, M. Information Systems Backsourcing. A Literature Review. J. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2018, 29, 62–78. [Google Scholar]

- Veltri, N.F.; Saunders, C.S.; Kavan, C.B. Information Systems Backsourcing: Correcting Problems and Responding to Opportunities. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2008, 51, 50–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chongvilaivan, A.; Hur, J.; Riyanto, Y.E. Outsourcing types, relative wages, and the demand for skilled workers: New evidence from U.S. manufacturing. Econ. Inq. 2009, 47, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asatiani, A.; Apte, U.; Penttinen, E.; Rönkkö, M.; Saarinen, T. Impact of accounting process characteristics on accounting outsourcing—Comparison of users and non-users of cloud-based accounting information systems. Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2019, 34, 100419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drezner, D.W. The Outsourcing Bogeyman. Foreign Aff. 2004, 83, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, G.M.; Helpman, E. Outsourcing in a Global Economy. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2005, 72, 135–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trocki, M. Outsourcing Metoda Restrukturyzacji Działalności Gospodarczej; PWE: Warsaw, Poland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, J.; Hirschheim, R.; Jacobs, R. Understanding the outsourcing learning curve: A longitudinal analysis of a large Australian company. Inf. Syst. Front. 2008, 10, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earl, M.J. Experiences in Strategic Information Systems Planning. MIS Q. 1993, 17, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Holcomb, T.R.; Hitt, M.A. Toward a model of strategic outsourcing. J. Oper. Manag. 2006, 25, 464–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brecher, R.A.; Chen, Z. Unemployment of Skilled and Unskilled Labor in an Open Economy: International Trade, Migration, and Outsourcing. Rev. Int. Econ. 2010, 18, 990–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Power, M.J.; Desouza, K.C.; Bonifazi, C. The Outsourcing Handbook: How to Implement a Successful Outsourcing Process; Kogan Page: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker, J.; Mithas, S.; Krishnan, M.S. Organizational Learning and Capabilities for Onshore and Offshore Business Process Outsourcing. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2010, 27, 11–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, A.K.; Basu, S. Offshore technology outsourcing: Overview of management and legal issues. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2007, 13, 21–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, K. Global HR Outsourcing Industry Trends in 2013. Available online: http://www.enterprisecioforum.com/en/blogs/kaushalshah/global-hr-outsourcing-industry-trends-20 (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- Grossman, G.M.; Rossi-Hansberg, E. Trading Tasks: A Simple Theory of Offshoring. Am. Econ. Rev. 2008, 98, 1978–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- König, J.; Koskela, E. Does International Outsourcing Really Lower Workers’ Income? J. Labor Res. 2011, 32, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kłosińska, O. Ewolucja Outsourcingu: Od Sposobu na Obniżenie Kosztów do Narzędzia Realizacji Strategii. Harv. Bus. Rev. Pol. 2007, 11, 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Marqués, D.P.; Simón, F.J.G. The effect of knowledge management practices on firm performance. J. Knowl. Manag. 2006, 10, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Gualdrón, S.T.; Roig, S. The New Venture Decision: An Analysis Based on the GEM Project Database. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2005, 1, 479–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unicorn HRO. Five Benefits of Human Resource Outsourcing—Great Advantages. 2020. Available online: http://www.unicornhro.com/articles/five-benefits-of-human-resource-outsourcing--great-advantages (accessed on 3 January 2021).

- Gospel, H.; Sako, M. The Re-bundling of Corporate Functions: The Evolution of Shared Services and Outsourcing. Hum. Resour. Manag. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2010, 19, 1367–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotzamani, K.; Longinidis, P.; Vouzas, F. The logistics services outsourcing dilemma: Quality management and financial performance perspectives. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2010, 15, 438–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardhan, I.; Whitaker, J.; Mithas, S. Information Technology, Production Process Outsourcing, and Manufacturing Plant Performance. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2006, 23, 13–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, J.; Cha, H. IT certifications, outsourcing and information systems personnel turnover. Inf. Technol. People 2010, 23, 330–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, N.; Levina, N. Global Multisourcing Strategy: Integrating Learning from Manufacturing into IT Service Outsourcing. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2011, 58, 717–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gay, C.L.; Essinger, J. Inside Outsourcing; Nicholas Brealey Publishing: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hsiaoa, H.I.; Kempb, R.G.M.; van der Vorstc, J.G.A.J.; Omtab, S.O. A classification of logistic outsourcing levels and their impact on service performance: Evidence from the food processing industry international. J. Prod. Econ. 2010, 124, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragg, S.M. Outsourcing. A Guide to Selecting the Correct Business Unit, Negotiating the Contact, Maintaining Control of the Process; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtsson, L.; Dabhilkar, M. Manufacturing outsourcing and its effect on plant performance—Lessons for KIBS outsourcing. J. Evol. Econ. 2008, 19, 231–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenemeier, L. Business-Process Outsourcing Grows. InformationWeek 2002, 14, 49–50. [Google Scholar]

- Hawrysz, L.; Foltys, J. Environmental Aspects of Social Responsibility of Public Sector Organizations. Sustainability 2015, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kolodiziev, O.M.; Boyko, N.O. Formation of customer capital management strategies at engineering enterprise. Actual Probl. Econ. 2015, 174, 168–180. [Google Scholar]

- Mussapirov, K.; Jalkibaeyev, J.; Kurenkeyeva, G.; Kadirbergenova, A.; Petrova, M.; Zhakypbek, L. Business scaling through outsourcing and networking: Selected case studies. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2019, 7, 1480–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Object Management Group (OMG). Business Process Model and Notation (BPMN), Version 2.0.2. 2013. Available online: http://www.omg.org/spec/BPMN/2.0.2/ (accessed on 4 May 2020).

- Stanger, A.; Williams, M.E. Private military corporations: Benefits and costs of outsourcing security. Yale J. Int. Aff. 2006, 2, 4–19. [Google Scholar]

- Adebayo, A.; Aderinto, A. Challenges of Outsourcing Security Services in Selected Educational Institutions in Ogun State, Nigeria. J. Appl. Secur. Res. 2018, 13, 285–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Castro, R.; Francoeur, C. When more is not better: Complementarities, costs and contingencies in stakeholder management. Strat. Manag. J. 2014, 37, 406–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddelani, O.; Idrissi, N.E.A.E.; Monni, S. Territorialized forms of production in Morocco: Provisional assessment for an own model in gestation. Insights Reg. Dev. 2019, 1, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoiroh, A. Peran Kecerdasan Emosi terhadap Resiliensi Pekerja pada Masa Pandemi COVID-19. Psisula Pros. Berk. Psikol. 2021, 3, 24–33. [Google Scholar]

- Siregar, H.; Rahayu, A.; Wibowo, L.A. Manajemen Strategi di Masa Pandemi COVID-19. Komitmen J. Ilm. Manaj. 2020, 1, 40–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiri, D. Menyelamatkan Usaha Mikro, Kecil dan Menengah dari Dampak Pandemi Covid-19. Fokus Bisnis Media Pengkaj. Manaj. Dan Akunt. 2020, 19, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorska, A.D. Outsourcing and relocation of services around the world. Conclusions for Poland. Pol. J. Econ. 2020, 213, 33–57. [Google Scholar]

- Dzwigol, H.; Dzwigol-Barosz, M.; Kwilinski, A. Formation of global competitive Enterprise environment based on industry 4.0 concept. Int. J. Entrep. 2020, 24, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, A.; Lan, J. The role of outsourcing in driving global carbon emissions. Econ. Syst. Res. 2016, 28, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radlo, M.J. Offshoring and Outsourcing. Implications for the Economy and Enterprises; Warsaw School of Economics Publishing House: Warsaw, Russia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, E.; Riezman, R.; Wang, P. Outsourcing of innovation. Econ. Theory 2009, 38, 485–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymaniak, A. Globalization of Services: Outsourcing, Offshoring and Shared Services Centers; WAiP: Warsaw, Russia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Outsourcing of Services in Poland. Report on the Survey of Companies. 2019. Available online: https://hrl.pl/outsourcing-uslug-w-polsce-raport-z-badania-firm/ (accessed on 4 February 2022).

- Corbett, M.F. Outsourcing Revolution. In Why It Makes Sense and How to Do It Right; Dearbon Trade Publishing: Chicago, IL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.J.-F.; Ngai, E.; Cho, V. Examining the determinants of outsourcing partnership quality in Chinese small- and medium-sized enterprises. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2009, 48, 453–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matejun, M. Outsourcing of Accounting and Tax Consultancy Improving Management Systems in the Information Society; Stabryła, A., Ed.; Publishing House of AE in Kraków: Kraków, Poland, 2006; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Jarka, S. Status and development prospects of outsourcing in Poland. Scientific Papers of the Warsaw University of Life Sciences. In Economics and Organization of Food Economy; SGGW: Warsaw, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Skoczylas, P. Outsourcing—As an Effective Restructuring Tool in Medical Facilities, Entrepreneurship and Management; SAN Publishing House: Warsaw, Poland, 2016; Volume 17, pp. 143–159. [Google Scholar]

- Foogooa, R. IS outsourcing—A strategic perspective. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2008, 14, 858–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschini, F.; Galetto, M.; Pignatelli, A.; Varetto, M. Outsourcing: Guidelines for a structured approach. Benchmarking Int. J. 2003, 10, 246–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carter, J.R.; Yan, T. The procurement function’s role in strategic outsourcing from a process perspective. Int. J. Procure. Manag. 2007, 1, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosar, F. Strategic outsourcing and optimal procurement. Int. J. Ind. Organ. 2017, 50, 91–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothaermel, F.T.; Hitt, M.A.; Jobe, L.A. Balancing vertical integration and strategic outsourcing: Effects on product portfolio, product success, and firm performance. Strat. Manag. J. 2006, 27, 1033–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, M.A.; Shamsuzzoha, A.; Helo, P. Does outsourcing always work? A critical evaluation for project business success. Benchmarking Int. J. 2018, 25, 2198–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagwati, J.; Panagariya, A.; Srinivasan, T.N. The Muddles over Outsourcing. J. Econ. Perspect. 2004, 18, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Foltys, J. Outsourcing w Przedsiębiorstwach Sektora MŚP. Scenariusz Aplikacyjny; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego: Kraków, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gay, C.L.; Essinger, J. Strategic Outsourcing; Przegląd Organizacji: Krakow, Poland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kuzminski, L.; Jalowiec, T.; Masloch, P.; Wojtaszek, H.; Miciula, I. Analysis of Factors Influencing the Competitiveness of Manufacturing Companies. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2020, 23, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miciuła, I. Methods of Creating Innovation Indices Versus Determinants of Their Values. Eurasian Econ. Perspect. 2018, 87, 357–366. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, R.; Prifling, M.; Beck, R. The role of cultural intelligence for the emergence of negotiated culture in IT offshore outsourcing projects. Inf. Technol. People 2009, 22, 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtaszek, H.; Miciuła, I. Analysis of Factors Giving the Opportunity for Implementation of Innovations on the Example of Manufacturing Enterprises in the Silesian Province. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maśloch, P.; Maśloch, G.; Kuźmiński, Ł.; Wojtaszek, H.; Miciuła, I. Autonomous Energy Regions as a Proposed Choice of Selecting Selected EU Regions—Aspects of Their Creation and Management. Energies 2020, 13, 6444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartner Report, Outsourcing HR Business Processes: Key Trends and Success Factors. 2014. Available online: http://www.gartner.com/5_about/news/outsourcing_sample.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2021).

| Criteria for Selecting an Outsourcing Operator | N | Marginal Response Values | Average | Mode | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum | Maximum | ||||

| Price | 78 | 2 | 5 | 4.12 | 5 |

| Experience | 78 | 2 | 5 | 3.88 | 4 |

| Location | 78 | 1 | 5 | 3.09 | 3 |

| Company’s reputation | 78 | 3 | 5 | 4.14 | 4 |

| Range of services | 78 | 2 | 5 | 4.17 | 4 |

| Size of the company | 78 | 1 | 5 | 2.73 | 2 |

| Quality of services | 78 | 3 | 5 | 4.51 | 5 |

| Area of Outsourcing | N | Marginal Response Values | Average | Mode | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum | Maximum | ||||

| Logistics | 32 | 2 | 5 | 3.88 | 4 |

| Production | 31 | 2 | 5 | 3.90 | 4 |

| IT | 42 | 3 | 5 | 4.31 | 5 |

| Finances | 68 | 2 | 5 | 4.07 | 5 |

| HR | 29 | 2 | 5 | 3.62 | 4 |

| Security | 69 | 2 | 5 | 3.45 | 3 |

| Cleaning | 41 | 1 | 5 | 3.41 | 4 |

| OHS | 66 | 2 | 5 | 3.30 | 3 |

| PR | 42 | 1 | 5 | 3.24 | 4 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kabus, J.; Dziadkiewicz, M.; Miciuła, I.; Mastalerz, M. Using Outsourcing Services in Manufacturing Companies. Resources 2022, 11, 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources11030034

Kabus J, Dziadkiewicz M, Miciuła I, Mastalerz M. Using Outsourcing Services in Manufacturing Companies. Resources. 2022; 11(3):34. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources11030034

Chicago/Turabian StyleKabus, Judyta, Michał Dziadkiewicz, Ireneusz Miciuła, and Marcin Mastalerz. 2022. "Using Outsourcing Services in Manufacturing Companies" Resources 11, no. 3: 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources11030034

APA StyleKabus, J., Dziadkiewicz, M., Miciuła, I., & Mastalerz, M. (2022). Using Outsourcing Services in Manufacturing Companies. Resources, 11(3), 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources11030034