From Understanding to Impactful Action: Systems Thinking for Systems Change in Chronic Disease Prevention Research

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Background

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The ABLe Change Framework (ACF)

2.2. The Prevention Systems Change Framework (PSCF)

3. Results

3.1. Reflections on the HE2 Project Derived from Applying the PSCF

3.1.1. Component 1: Building a Systemic Lens for Prevention

3.1.2. Component 2: Continual Implementation Focus

3.1.3. Component 3: Bringing Together the Systemic Lens and Implementation Focus

3.1.4. Component 4: Developing a Theory of Systems Change

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Haynes, A.; Rowbotham, S.; Grunseit, A.; Bohn-Goldbaum, E.; Slaytor, E.; Wilson, A.; Lee, K.; Davidson, S.; Wutzke, S. Knowledge mobilisation in practice: An evaluation of the Australian Prevention Partnership Centre. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2020, 18, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, A.; Rychetnik, L.; Finegood, D.; Irving, M.; Freebairn, L.; Hawe, P. Applying systems thinking to knowledge mobilisation in public health. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2020, 18, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rychetnik, L.; Bauman, A.; Laws, R.; King, L.; Rissel, C.; Nutbeam, D.; Colagiuri, S.; Caterson, I. Translating research for evidence-based public health: Key concepts and future directions. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2012, 66, 1187–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfenden, L.; Reilly, K.; Kingsland, M.; Grady, A.; Williams, C.M.; Nathan, N.; Sutherland, R.; Wiggers, J.; Jones, J.; Hodder, R.; et al. Identifying opportunities to develop the science of implementation for community-based non-communicable disease prevention: A review of implementation trials. Prev. Med. 2019, 118, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carey, G.; Malbon, E.; Carey, N.; Joyce, A.; Crammond, B.; Carey, A. Systems science and systems thinking for public health: A systematic review of the field. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e009002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rusoja, E.; Haynie, D.; Sievers, J.; Mustafee, N.; Nelson, F.; Reynolds, M.; Sarriot, E.; Swanson, R.C.; Williams, B. Thinking about complexity in health: A systematic review of the key systems thinking and complexity ideas in health. J. Eval. Clin. Prac. 2018, 24, 600–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, J.A.; Knowles, D.; Wiggers, J.; Livingston, M.; Room, R.; Prodan, A.; McDonnell, G.; O’Donnell, E.; Jones, S.; Haber, P.S.; et al. Harnessing advances in computer simulation to inform policy and planning to reduce alcohol-related harms. Int. J. Publ. Health 2018, 63, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Allender, S.; Brown, A.D.; Bolton, K.A.; Fraser, P.; Lowe, J.; Hovmand, P. Translating systems thinking into practice for community action on childhood obesity. Obes. Rev. 2019, 20, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Baker, P.; Brown, A.D.; Wingrove, K.; Allender, S.; Walls, H.; Cullerton, K.; Lee, A.; Demaio, A.; Lawrence, M. Generating political commitment for ending malnutrition in all its forms: A system dynamics approach for strengthening nutrition actor networks. Obes. Rev. 2019, 20, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Friel, S.; Pescud, M.; Malbon, E.; Lee, A.; Carter, R.; Greenfield, J.; Cobcroft, M.; Potter, J.; Rychetnik, L.; Meertens, B. Using systems science to understand the determinants of inequities in healthy eating. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0188872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Behrens, T.R.; Foster-Fishman, P.G. Developing operating principles for systems change. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2007, 39, 411–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster-Fishman, P.G.; Nowell, B.; Yang, H. Putting the system back into systems change: A framework for understanding and changing organizational and community systems. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2007, 39, 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster-Fishman, P.G.; Watson, E.R. The ABLe change framework: A conceptual and methodological tool for promoting systems change. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2012, 49, 503–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenhalgh, T. Bridging the ‘Two Cultures’ of Research and Service: Can Complexity Theory Help?: Comment on Experience of Health Leadership in Partnering With University-Based Researchers in Canada–A Call to ‘Re-imagine’Research. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2020, 9, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Fahy, N. Research impact in the community-based health sciences: An analysis of 162 case studies from the 2014 UK Research Excellence Framework. BMC Med. 2015, 13, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johnston, L.; Finegood, D. Cross-sector partnerships and public health: Challenges and opportunities with the private sector. Front. Publ. Health Serv. Syst. Res. 2015, 4, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter, H.; Savona, N.; Glonti, K.; Bibby, J.; Cummins, S.; Finegood, D.T.; Greaves, F.; Harper, L.; Hawe, P.; Moore, L.; et al. The need for a complex systems model of evidence for public health. Lancet 2017, 390, 2602–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pescud, M.; Friel, S.; Lee, A.; Sacks, G.; Meertens, E.; Carter, R.; Cobcroft, M.; Munn, E.; Greenfield, J. Extending the paradigm: A policy framework for healthy and equitable eating (HE2). Publ. Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 3477–3481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pescud, M.; Sargent, G.; Kelly, P.; Friel, S. How does whole of government action address inequities in obesity? A case study from Australia. Int. J. Equity Health 2019, 18, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Riley, T.; Hopkins, L.; Gomez, M.; Davidson, S.; Chamberlain, D.; Jacob, J.; Wutzke, S. A Systems Thinking Methodology for Studying Prevention Efforts in Communities. Syst. Prac. Act. Res. 2020, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt-Abbey, B.; Reynolds, M.; Ison, R. Towards systemic evaluation in turbulent times–Second-order practice shift. Evaluation 2020, 26, 205–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rychetnik, L.; Nutbeam, D.; Hawe, P. Lessons from a review of publications in three health promotion journals from 1989 to 1994. Health Educ. Res. 1997, 12, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Allender, S.; Millar, L.; Hovmand, P.; Bell, C.; Moodie, M.; Carter, R.; Swinburn, B.; Strugnell, C.; Lowe, J.; De la Haye, K.; et al. Whole of systems trial of prevention strategies for childhood obesity: WHO STOPS childhood obesity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health 2016, 13, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, A.; Garvey, K.; Davidson, S.; Milat, A. What can policy-makers get out of systems thinking? Policy partners’ experiences of a systems-focused research collaboration in preventive health. Int. J. Heath Policy Manag. 2020, 9, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, J.; Morton, S.; Johnstone, M.; Creighton, D.; Allender, S. Tools and analytic techniques to synthesise community knowledge in CBPR using computer-mediated participatory system modelling. NPJ Dig. Med. 2020, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Leykum, L.K.; Pugh, J.; Lawrence, V.; Parchman, M.; Noël, P.H.; Cornell, J.; McDaniel, R.R. Organizational interventions employing principles of complexity science have improved outcomes for patients with Type II diabetes. Implement. Sci. 2007, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fazey, I. Resilience and higher order thinking. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.C.; Stroink, M.L. The relationship between systems thinking and the new ecological paradigm. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2016, 33, 575–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allender, S.; Owen, B.; Kuhlberg, J.; Lowe, J.; Nagorcka-Smith, P.; Whelan, J.; Bell, C. A community based systems diagram of obesity causes. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bellew, W.; Smith, B.J.; Nau, T.; Lee, K.; Reece, L.; Bauman, A. Whole of Systems approaches to physical activity policy and practice in Australia: The ASAPa Project overview and initial systems map. J. Phys. Act. Health 2020, 17, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freebairn, L.; Atkinson, J.A.; Qin, Y.; Nolan, C.J.; Kent, A.L.; Kelly, P.M.; Penza, L.; Prodan, A.; Safarishahrbijari, A.; Qian, W.; et al. ‘Turning the tide’on hyperglycemia in pregnancy: Insights from multiscale dynamic simulation modeling. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2020, 8, e000975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, N.; Li, V.; Atkinson, J.A.; Heffernan, M.; McDonnell, G.; Prodan, A.; Freebairn, L.; Lloyd, B.; Nieuwenhuizen, S.; Mitchell, J.; et al. Can the target set for reducing childhood overweight and obesity be met? A system dynamics modelling study in New South Wales, Australia. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2019, 36, 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Swinburn, B.A.; Kraak, V.I.; Allender, S.; Atkins, V.J.; Baker, P.I.; Bogard, J.R.; Brinsden, H.; Calvillo, A.; De Schutter, O.; Devarajan, R.; et al. The global syndemic of obesity, undernutrition, and climate change: The Lancet Commission report. Lancet 2019, 393, 791–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster-Fishman, P.G.; Watson, E.R. Action research as systems change. Handb. Engaged Scholarsh. Contemp. Landscape 2010, 2, 235–256. [Google Scholar]

- Durlak, J.A.; DuPre, E.P. Implementation matters: A review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2008, 41, 327–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- By, R.T. Organisational change management: A critical review. J. Chang. Manag. 2005, 5, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, R. Change management--or change leadership? J. Chang. Manag. 2002, 3, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Developmental Evaluation: Applying Complexity Concepts to Enhance Innovation and Use; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, D.H. Thinking in Systems: A Primer; Chelsea Green Publishing: Hardford, VT, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kislov, R.; Pope, C.; Martin, G.P.; Wilson, P.M. Harnessing the power of theorising in implementation science. Implement. Sci. 2019, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rogers, P. Theory of Change: Methodological Briefs-Impact Evaluation; UNICEF Office of Research: Florence, Spain, 2014; Volume 2, pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Maru, Y.T.; Sparrow, A.; Butler, J.R.; Banerjee, O.; Ison, R.; Hall, A.; Carberry, P. Towards appropriate mainstreaming of “Theory of Change” approaches into agricultural research for development: Challenges and opportunities. Agricult. Syst. 2018, 165, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, H.S. The epistemology of qualitative research. In Ethnography and Human Development: Context and Meaning in Social Inquiry; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1996; Volume 27, pp. 53–71. [Google Scholar]

- Foster-Fishman, P.; Watson, E. Creating habits for inclusive change. Found. Rev. 2018, 10, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bagnall, A.M.; Radley, D.; Jones, R.; Gately, P.; Nobles, J.; Van Dijk, M.; Blackshaw, J.; Montel, S.; Sahota, P. Whole systems approaches to obesity and other complex public health challenges: A systematic review. BMC Publ. Health 2019, 19, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovmand, P. Community Based System Dynamics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, A.; Wutzke, S.; Overs, M. The Australian Prevention Partnership Centre: Systems thinking to prevent lifestyle-related chronic illness. Public Health Res. Pract. 2014, 25, e2511401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Freebairn, L.; Rychetnik, L.; Atkinson, J.A.; Kelly, P.; McDonnell, G.; Roberts, N.; Whittall, C.; Redman, S. Knowledge mobilisation for policy development: Implementing systems approaches through participatory dynamic simulation modelling. Health Res.Policy Syst. 2017, 15, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Productivity Commission. Innovations in Care for Chronic Health Conditions, Productivity Reform Case Study; Productivity Commission: Canberra, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Checkland, P.; Poulter, J. Learning for Action: A Short Definitive Account of Soft Systems Methodology and Its Use for Practitioner, Teachers, and Students; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Howick, J.; Maskrey, N. Evidence based medicine: A movement in crisis? BMJ 2014, 348, g3725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. Evidence-based medicine: A new approach to teaching the practice of medicine. JAMA 1992, 268, 2420–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster-Fishman, P.G.; Behrens, T.R. Systems change reborn: Rethinking our theories, methods, and efforts in human services reform and community-based change. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2007, 39, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Framework Location | Locate a framework that was relevant to our circumstances and characterised by a deep and comprehensive set of questions to guide transformative systems change. The ACF was chosen and studied given its theoretical underpinnings and previous usage. It was also discussed in terms of its applicability to prevention. |

| Initially, the ACF was used in its original form to evaluate the HE2 Project, but it became apparent that many of the questions needed to be adapted to fit the prevention research context as opposed to the community psychology context. | |

| Framework Adaption | The three components from the ACF and the related questions were imported verbatim into a Word document, as a table with the three ACF components (column 1) and related questions (column 2). |

Two additional columns were then added:

| |

| The reflective notes in column 4, once discussed and written, were then divided into two sections to allow more nuance to be revealed relating to: (i) understanding the problem, and (ii) focusing on the systems change implications to gain a deeper understanding where the emphasis was placed within the HE2 Project. | |

| New Framework Application | Each component and its accompanying questions were reviewed and adapted as required for a prevention research context, with reference to the HE2 Project. Through an iterative process, the questions for each component were either modified, removed, or remained the same, and a handful of new questions were added to create the PSCF. |

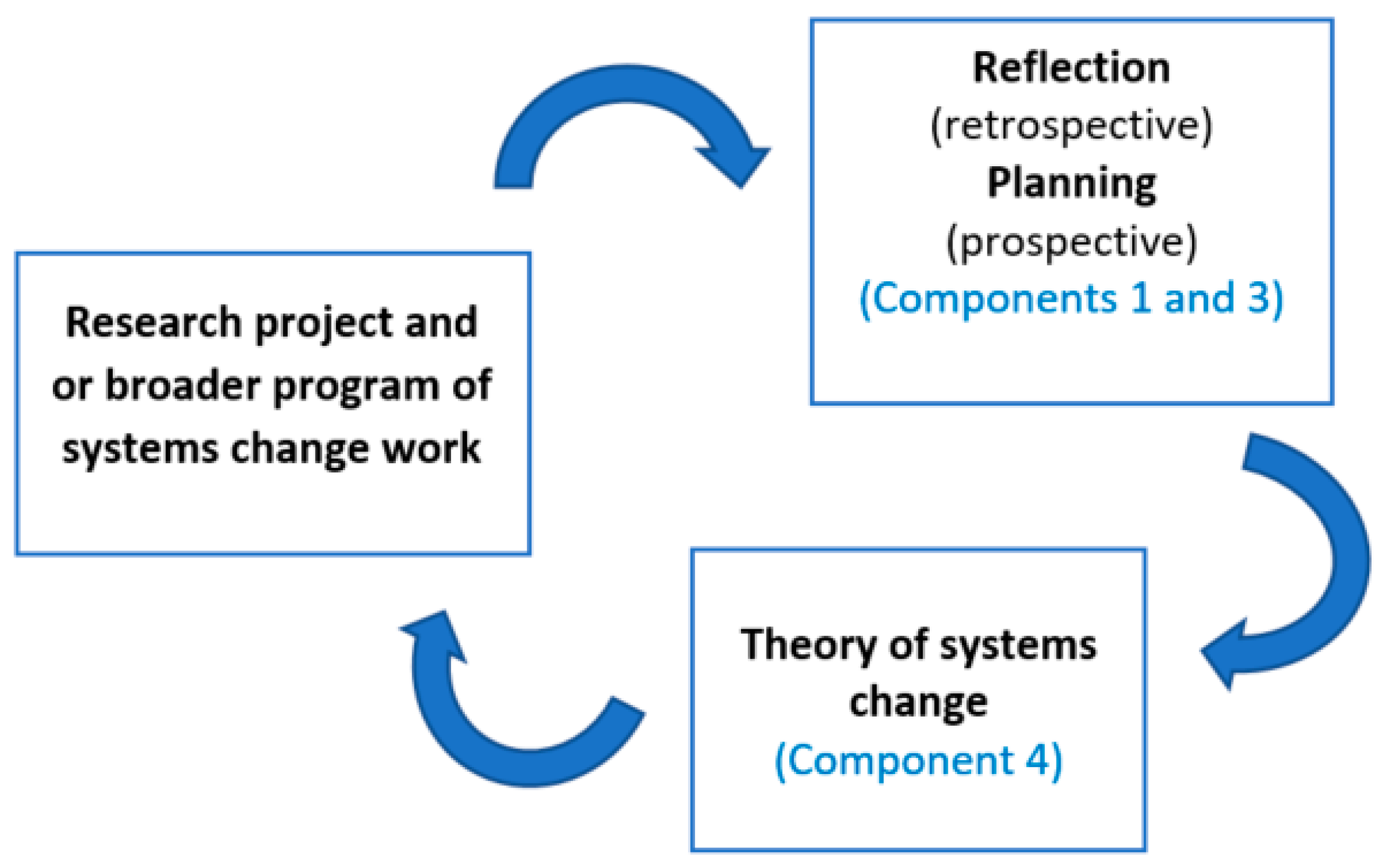

| A fourth component was added to the PSCF to focus on the process of creating a theory of systems change. This component took the form of some short sentences, informed by the reflections made using the first three components of the PSCF, to explain how a series of events will have impact within the HE2 system to create change. |

| Example Changes | Original ACF Question | Adapted PSCF Question |

|---|---|---|

| More focus on policy | Do targeted constituents (adults and youth) have real influence over service delivery decisions, processes, plans and options? Does their voice really matter? If not, why not? | Do the different policy actors within the policy community (government departments, non-government organisations, and technical experts, researchers) have real influence over intersectoral policy decisions, processes, plans, and options? |

| Change of language to suit prevention context | What gaps in service exist to build a continuum of care? What additional programs/supports are needed? | What gaps in policy exist to build a healthy and equitable eating system? What additional policies and programs are needed? |

| Removal of questions that did not seem to apply | Where are current programs located? How does this location affect access and use of services? | |

| Addition of questions to add more depth to the exploration | What are the key leverage points for addressing healthy and equitable eating? |

| Systemic Lens | |

|---|---|

| Systems Characteristics | Questions and Key Elements |

| Policies | What gaps in policy exist to build the system? What additional policies and programs are needed? Are the current policies evidence-based and relevant to the system? |

| Connections and boundaries | Are government departments, NGOs, industry, and community groups working in siloed or well-connected ways? Do government stakeholders, non-government organisations, industry, and community groups trust each other and share information, data, and resources? |

| Power and control dynamics | Do the different policy actors within the policy community (government departments, non-government organisations, technical experts, and researchers) have real influence over intersectoral policy decisions, processes, plans, and options? Do different government departments share decision making power around policies? Is decision-making power shared across all levels (federal, state, and local) of government? |

| System regulations | Do any current policies or procedures get in the way of the overall goal of working towards achieving chronic disease prevention? If so, which ones need to change? What new policies and procedures are needed to support the overall goal? Does the current policy context motivate intersectoral action to create changes in order to facilitate the systems changes? |

| Values and norms | What attitudes and values held by policy makers might get in the way of the proposed changes? |

| System interdependencies | To what extent and how do system variables interact with each other and provide each other with feedback? What are the key leverage points for addressing the issue? |

| Implementation Focus | |

| Component and Definition | Key Elements |

| Readiness | Policy actors’ (i.e., government departments, non-government organisations, technical experts, and researchers) perceptions of: Awareness: general awareness of the targeted change. Valence: change would provide personal or system benefits. Management support: local leaders are committed to the change. Discrepancy: change is necessary. Self-efficacy: change is feasible and system actors can implement the new behaviours. Contextual and structural factors: change is supported by the institutional context. |

| Contingent capacities | Knowledge of the system: |

| |

| Relational capacity: | |

| |

| Change capability: | |

| |

| Innovative specific capacity: | |

| |

| Diffusion | Promoting broad scale awareness of change effort across system actors. Encouraging the adoption of the innovation. Ensuring the actual and appropriate use of the new information about the chronic disease prevention system. Expanding the use of chronic disease prevention study findings across system sectors. |

| Sustainability | Maintaining effective new policies and procedures. Institutionalisation of new mindsets and practices. Sustaining capacities and supports needed to ensure that successful intersectoral collaborations are kept in the long run. |

| Integrating a Systemic Lens and Implementation Focus | |

| Key Components | Key Elements |

| Simple rules | Engaging diverse perspectives. Thinking systemically. Incubating change. Effectively implementing change. Adapting quickly. Pursuing social justice. |

| Systemic action learning teams | Using systemic action learning. |

| Small wins | Identifying small wins. |

| Theory of Systems Change | |

| Prospective theory of systems change | For planning purposes. Articulating actions and reactions to create systems change (e.g., who will do what, who that will impact on and what else will occur, and what is going to change with what outcomes). |

| Retrospective theory of systems change | For reflection and future planning purposes. Articulating your systems change hypothesis and assumptions. |

| Systems Characteristics | Example Questions–Prevention Research (HE2 Project) | Reflections on the HE2 Project–Understanding the System | Reflections on the HE2 Project–Creating Systems Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Policies | What gaps in policy exist to build a healthy and equitable eating system? What additional policies and programs are needed? | This content was covered as part of our published HE2 Framework which provided an organising framework for exploring where gaps in policies and programs exist. | The identified gaps in policy will need to be addressed as part of future systems change efforts. |

| Are the current policies evidence-based and relevant to HE2? | The use of evidence in informing current policies relating to HE2 is mixed. In terms of the HE2 Project, the HE2 Diagram and Framework were focused on the population level within Australia, using a combination of published scientific evidence, practice wisdom, and subject matter expertise. We found this mix to be most aligned with systems practice in terms of using multiple sources of evidence. | Using a combination of published scientific evidence, practice wisdom, and subject matter expertise will be key to shifting the system, as multiple forms of evidence are required within different contexts. | |

| Connections and boundaries | Are government departments, NGOs, industry, and community groups working in siloed or well-connected ways? | In HE2 we focused only on government policy makers, technical experts and non-government organisations. A boundary was established within the system of the actors that we were seeking to influence, and this did not include industry or community groups. Upon reflection, having included these groups would have added to the richness of the data; however, our resources did not allow all groups to be included. | Moving forward, widening the boundaries in terms of actor involvement will be key to influencing systems change. We recognise the need to include communities with a lived experience of nutrition-related inequities, service providers and support services, and key decision makers. |

| Do government stakeholders, non-government organisations, industry, and community groups trust each other and share information, data, and resources? | We did not explicitly ask this question, but we did uncover related data through the interview process. | In future iterations of this work, we could be more explicit with seeking out answers to this question as a way of exploring barriers and enablers to creating systems change. | |

| Power and control dynamics | Do the different policy actors within the policy community have real influence over intersectoral policy decisions, processes, plans and options? | Covered in qualitative study interviews (e.g., were those within the social inclusion group influential in health policy work, and, conversely, were those within the health group engaged in the social inclusion policy work?). | Systems change efforts will need to involve those with intersectoral influence within the system. |

| Do different government departments share decision making power around HE2 related policies? | No, the departments don’t currently share decision making power, and in fact work in quite siloed ways; this is more the case currently, following a restructure. This clearly acted as a blockage to creating change in terms of intersectoral working. | Exploring the possibility for shared decision-making power as a way of improving intersectoral working will be key for systems change efforts. | |

| Is decision-making power shared across all levels (federal, state, and local) of government? | Decision-making power is shared across all levels of government. The key learning here is that it would have been valuable to explore the decision-making power with respect to a focus on longer term changes in relation to HE2. | A next step towards systems change could involve examining the decision-making points of potential leverage, and the relevant distributions of power at those points. We could take the view that the key to successful systems change is viewing everyone as an actor of change, and helping individuals leverage change within their sphere of influence. We also know that power is about shifting these dynamics. In future iterations of this work, it would be important to include the voices of community members who are experiencing inequities. | |

| System regulations | Do any current policies or procedures get in the way of the overall goal of working towards achieving healthy and equitable eating? If so, which ones need to change? | Our qualitative study shows some of the institutional mechanisms for promoting intersectoral collaboration that were positive, where it was possible. We had intended to do a policy analysis; however, another piece of work was exploring similar questions. | Policy siloes are an organisational practice; if we want to improve intersectoral collaboration (and thus create systems change), then the policy siloes are problematic, as well as the lack of institutional mechanisms to enable intersectoral collaboration. |

| What new policies and procedures are needed to support the overall goal? | We addressed this at a high level in terms of policies (but not procedures) in the HE2 Framework. This was also addressed through interviews in terms of exploring barriers and enablers to implementation of intersectoral actions. | Systems change will come about when policies and procedures supporting the improvement of inequities in healthy eating are implemented successfully. | |

| Does the current policy context motivate intersectoral action to create changes in order to facilitate a healthier and more equitable eating system? | This was covered in our HE2 diagramming workshops as part of the qualitative study; people were able to draw connections between areas (e.g., linking the health sector with the education and transport sectors) but restrained, because politically they were not able to do it; thus, we implicitly illuminated this, but did not explicitly explore the policy context; perhaps we could have. | Given that actors are saying that intersectoral work is impossible or difficult, moving forward, it would be necessary to bring them together as a collective to discuss the system, creating shared understanding where possible, and start from there. | |

| Values and norms | What attitudes and values held by policy makers might get in the way of the proposed changes to HE2? | Equity is a value—we had a strong normative starting point that made equity very explicit. In the first HE2 diagram workshop, people within the group were all self-selected and interested in addressing equity goals as part of their work and research, but within the diagramming workshops at the level of the qualitative study, many participants were not focused on equity at all; so, we had a diversity of views. We did not however explicitly ask them about attitudes and values, but we saw it play out in diagramming workshop. | Moving forward, it will be important to distinguish between implicit and explicit theories of systems change around equity, and where and how to achieve it. While people publicly agree that equity matters, when doing the work, this may be forgotten or not prioritised. Providing opportunities for those involved in the systems change efforts to pause and discuss the kinds of procedures and policies needed to ensure that equity is front and centre. |

| System interdependencies | To what extent, and how, do system variables interact with each other and provide each other with feedback? | This is precisely what our HE2 Diagram shows. | The key is to now continue to use this visual depiction in order to progress the agenda with respect to policies that better support healthy and equitable eating. |

| What are the key leverage points for addressing HE2? | We established key leverage points within our HE2 diagram. | A key feedback loop and leverage point within the food supply and environment sub-system within the HE2 Diagram was one between food labelling and the impact food labelling has on food reformulation and marketing. This would thus be a key focus area for creating systems change. All leverage points should be explored and prioritised as part of the change effort. |

| Component and Definition | Key Elements—Prevention Research (HE2 Project) | Reflections on the HE2 Project—Understanding the System | Reflections on the HE2 Project—Creating Systems Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Readiness | The extent to which system actors believe that change is necessary, feasible, and desirable within the broader structural context. | In terms of policy actors, we can only speak to the perceptions of those included within our study as opposed to the broader system of healthy and equitable eating. Awareness: Those policy actors involved in the creation of the HE2 Diagram were of the view that change is necessary; those included as part of the qualitative interviews had mixed opinions. Valence: Little was discussed in relation to personal benefits of change; in terms of the system, however, the discussion always centred on the broad topic of inequities. Management support: Leadership in this space varied in terms of supporting changes. Discrepancy: The belief that change was necessary was held within the core group of HE2 diagramming participants; broader than this, however, views were mixed, because change was not a high priority for all actors. Self-efficacy: The broader system in its current form is constraining the desired change due to institutional constraints because some leaders are either unable or unwilling to promote change. Contextual and structural factors: The feasibility of creating a healthy and equitable eating system is constrained due to blocks around intersectoral working. | The notion of readiness points to the need to include those actors with a remit to enact change in future work of this kind, and who understand the benefits of and will advocate for intersectoral working. |

| Contingent capacities | The skills and knowledge sets system actors need to effectively respond to the shifting demands of the systemic change work. | Knowledge of the system: The HE2 diagram facilitated a strong knowledge of the system from the groups’ perspectives, including important feedback loops. Relational capacity: In general, ties were weak when it came to intersectoral working. Change capability: Within the qualitative study, this was explored but without any depth; the findings that did emerge mainly indicated a lack of resources. Within the study we interviewed people with a remit to implement desired changes and explored this in terms of barriers and enablers. Many qualitative study participants were able to assimilate new knowledge regarding HE2, but many were not, as it was not a priority for them to engage in this topic area and thus our traction was limited. Innovative specific capacity: While the skills and knowledge set of those involved in our study were appropriate, only a small handful were equipped to implement changes. | Longer term, in order to make changes, more focus upon engaging with those with a remit and desire for implementing desired changes would be required. While our study identified some capacity concerns, an intentional assessment of these specific implementation capacities helped us to understand the challenges more fully that we faced, and, therefore, it will be essential that these are addressed in future systems change efforts. |

| Diffusion | An intentional focus on the adoption, use, and spread of the targeted change. | Across the broader system, the findings and recommendations emerging from the HE2 Project have been shared in multiple forums both locally, within Australia, and more broadly at the international level through avenues such as conference presentations, meetings, and discussions with policy makers. | In terms of ensuring that changes in mindset and practices occur, without some sort of accountability mechanisms in place, this is not a possibility. In future, we could take a more explicit approach to strategizing as to how to begin to shift to move beyond increasing awareness, knowledge, and sensitisation to beginning to focus on mindsets and practices of those from other sectors with a remit to make change. This would form a useful second stage for the HE2 Project, moving forward. |

| Sustainability | Maintaining policies, practices, and changes brought about by the change effort. | In terms of new policies and procedures, new mindsets and practice, and sustaining capacities and supports, this is not something that we explored as part of our study, and, thus, we cannot speak to the concept of maintenance. | Being mindful of the sustainability of policies and practices throughout the HE2 system will be a key feature of systems change in future iterations of this work. |

| Key Components | Complex Systems Change Framework Features | Reflections on the HE2 Project—Understanding the System | Reflections on the HE2 Project—Creating Systems Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simple rules | Engaging diverse perspectives is arguably one of the most important aspects of defining a problem and identifying and understanding its root causes, as well as defining and setting the boundaries around a system. A powerful learning process occurs when multiple perspectives are shared in an open, receptive, and transparent manner. The Framework explicitly calls for the inclusion of diverse perspectives from vertical (e.g., leaders, managers, and staff at the coal face) and horizontal (e.g., non-government organisations, government organisations, and industry) system layers, and those affected by problems within the system (e.g., community members at risk for or experiencing chronic disease). | While we did include a diverse group of people, our perspectives were more convergent than divergent overall, except within the qualitative study, where there was more of a diversity of perspectives. | Future research would need to include a more diverse disciplinary and sectoral mix, as well as include insights from a representative range of communities experiencing nutrition-related inequities. |

| The ability to think systemically, is key to identifying root causes of problems, thus leading to more potent and sustainable solutions. Without honing this ability, problems will be seen only in terms of proximal causes, rather than addressing the core driving force of the problem. | Thinking systemically was one of our strengths. We did this mainly through our HE2 Diagram work whereby our language was more around ‘causes’ than ‘root causes’. It’s important to note here that the social determinants of health (SDOH) literature is focused on the systemic drivers of chronic disease. In reality, however, SDOH work is very siloed and often not carried out from a systems perspective. | Thinking systemically must continue to be the overarching paradigm from which to view SDOH work and work as researchers, moving forward; this must be emphasized at all stages of future work that seeks to address inequities in healthy eating. | |

| In working towards transformative change, it is essential that small changes across multiple levels of the community are taken in an ongoing manner, thus acting to incubate change. Further changes can be observed when key feedback loops are identified and leveraged upon accordingly. | Across various data collections points throughout the study, we discussed the different levels of awareness, knowledge, and sensitisation in those taking part in the study. In terms of the bigger picture work required to create a more healthy and equitable eating system, we identified key feedback loops at a high level across the system, and at a lower level within sub systems. We did not have discussions nor plan for small changes across multiple levels. In retrospect, there may have been benefit in doing so to help us navigate our way through smaller changes on the pathway toward more transformative changes, in terms of shifting mindsets and policy making practices. We did raise awareness, knowledge, and sensitisation in an implicit way throughout the course of the study. | Incubating change must be emphasized moving forward, with this work occurring both within research teams in terms of learning and practice but also with respect to changes happening externally, relating to addressing nutrition-related inequities. | |

| When it comes to effectively implementing change, it is essential that efforts are focused on building a supportive climate that facilitates ongoing implementation of change actions (e.g., mindsets and practices) across the system. These aspects are the focus of the implementation component of the Adapted Framework, namely readiness, capacity, diffusion, and sustainability. | As noted above, we had less of a focus on readiness, capacity, diffusion, and sustainability within this piece of work and, thus, this is something that would likely facilitate greater impact when it comes to our change goals on a longer-term basis. We did think about the readiness and capacity implicitly, but what we did not do was build in any monitoring, evaluation, and learning mechanisms; so, we were not sure if it was effective. | Monitoring, evaluation, and learning will be a key feature of future work. Thus, we will have the ability to learn and respond from an evidence informed place when it comes to the implementation of changes. | |

| When working within a complex adaptive system, and acting to foster change, the emphasis must be on understanding, learning, and adapting rather than rigidly planning. Being nimble, with the ability to adapt quickly to changing information, actions, and circumstances, will enable appropriate responses to opportunities or problems that may arise. | Across the study, there were several changes that were required to be made in order to adapt to the changing needs of stakeholders and study participants, especially in relation to the timing of data collection within the context of political and policy changes. These adaptations, however, were not in response to the change goals. | As noted above, having good monitoring and evaluation mechanisms and a focus on learning will be helpful for allowing us to swiftly adapt to new information, as it emerges. | |

| Pursuing social justice as not only a simple rule, but as an overarching value underpinning the work, will place a sharp focus on understanding inequities and their root causes. | Equity was the main value underpinning this piece of work from the perspective of the research team. The HE2 diagram unearthed many of the root causes driving nutrition-related inequities. There was a problem, however, whereby some qualitative study participants didn’t hold equity front and centre in their minds and work. | As noted in an earlier reflection, providing opportunities for those involved in the systems change efforts to pause and discuss the kinds of procedures and policies needed to ensure equity is front and centre will be essential. | |

| Systemic action learning teams | Systemic action learning provides a way of simultaneously addressing the need to bring together the systemic lens and implementation focus, because an iterative problem-solving cycle is inherent to this method of working (Stringer 2013). Teams are engaged in an ongoing cycle of inquiry, whereby context is studied, solutions are devised, designed, and actioned. These actions are then analysed for their level of efficacy, followed by a reanalysis of the current situation, thus repeating the cycle of inquiry again (Foster-Fishman and Watson 2010). Systemic action learning teams operate individually at different levels within the system, but collectively, the teams’ efforts integrate into a cohesive effort that creates change across the system (Burns 2007). Teams each need to adhere to the simple rule of adapting quickly in order to address emergent issues and opportunities within the system. | We did not engage in this way as part of the HE2 study; however, it is apparent how this level of detailed focus and ongoing analysis can have benefits in terms of maintaining a focus on learning and creating desired changes. | We would ideally design systemic action teams at multiple levels of government, as well as spanning industry, the not-for-profit sector, academic, and community level, as work in this area expanded over time and across the system. |

| Small wins | Identifying small wins across the duration of a body of work fosters momentum, motivation, and a recognition that change, even is small or emergent, is occurring. Tackling smaller issues that will accumulate to produce larger overall changes renders those responsible within the system to experience a sense of empowerment and commitment, that what seems insurmountable can be overcome. An awareness of small wins, as they occur, has the added benefit of feedback about what is and is not working and how the system is reacting to actions as they are implemented. | We did not implement the use of small wins within our project. It is something that may provide a useful indicator and, thus, continued focus on the mindset and practice shifts we were aiming to achieve in future work of this kind. In retrospect, we could have celebrated small wins such as having all the directorates within our qualitative study in one room to draw a causal loop diagram. This would count as a short-term win. | As small wins are an effective way of incubating change over time, future systems change work would benefit by incorporating these. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pescud, M.; Rychetnik, L.; Allender, S.; Irving, M.J.; Finegood, D.T.; Riley, T.; Ison, R.; Rutter, H.; Friel, S. From Understanding to Impactful Action: Systems Thinking for Systems Change in Chronic Disease Prevention Research. Systems 2021, 9, 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems9030061

Pescud M, Rychetnik L, Allender S, Irving MJ, Finegood DT, Riley T, Ison R, Rutter H, Friel S. From Understanding to Impactful Action: Systems Thinking for Systems Change in Chronic Disease Prevention Research. Systems. 2021; 9(3):61. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems9030061

Chicago/Turabian StylePescud, Melanie, Lucie Rychetnik, Steven Allender, Michelle J. Irving, Diane T. Finegood, Therese Riley, Ray Ison, Harry Rutter, and Sharon Friel. 2021. "From Understanding to Impactful Action: Systems Thinking for Systems Change in Chronic Disease Prevention Research" Systems 9, no. 3: 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems9030061

APA StylePescud, M., Rychetnik, L., Allender, S., Irving, M. J., Finegood, D. T., Riley, T., Ison, R., Rutter, H., & Friel, S. (2021). From Understanding to Impactful Action: Systems Thinking for Systems Change in Chronic Disease Prevention Research. Systems, 9(3), 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems9030061