Inside Out: Organizations as Service Systems Equipped with Relational Boundaries

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Boundaries of Organizations

Identification Criteria of Organizational Boundaries

2.2. Systemic Conception of Organizational Boundaries

Viable System Approach as a Lens for Interpreting Boundaries

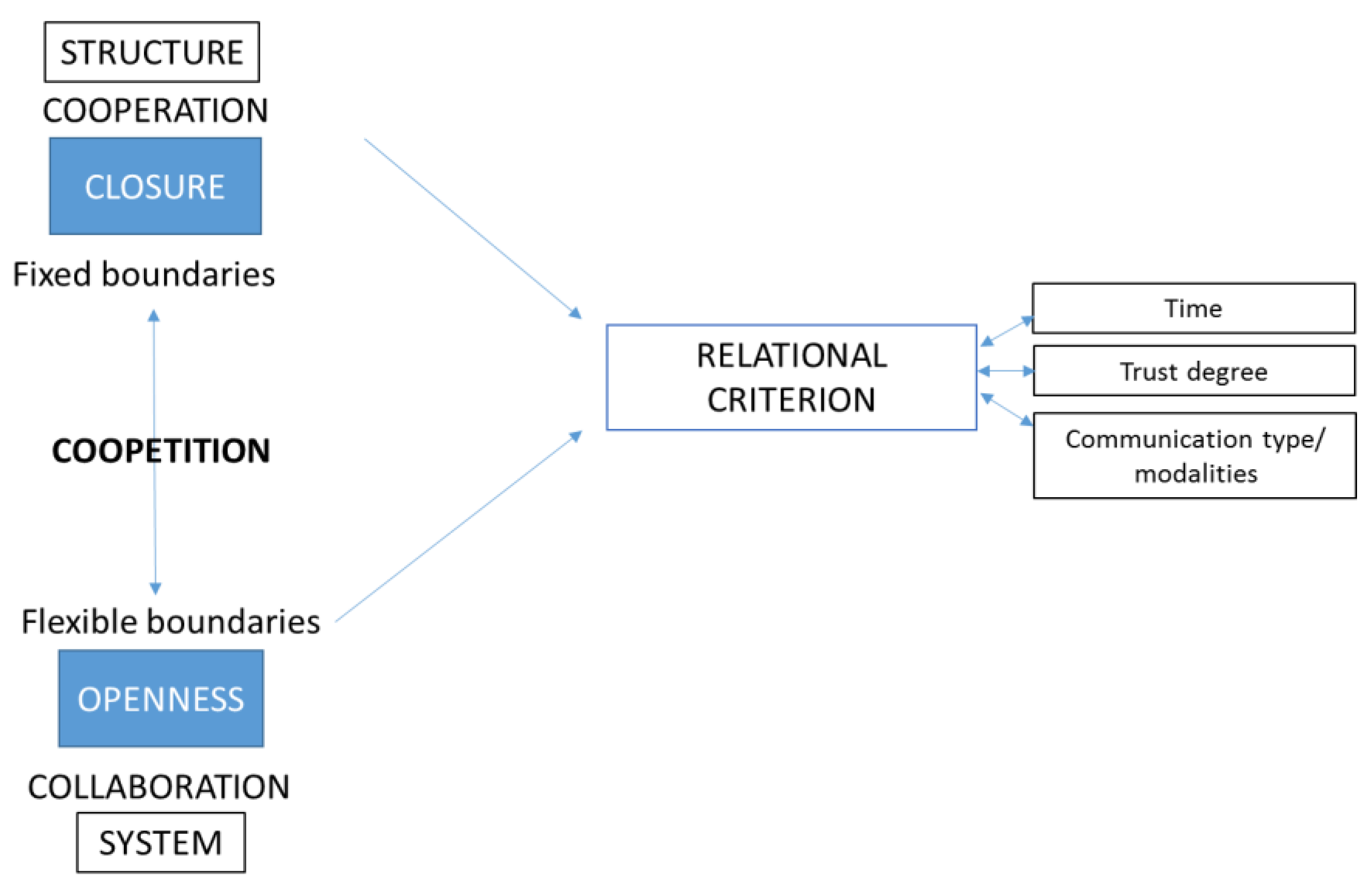

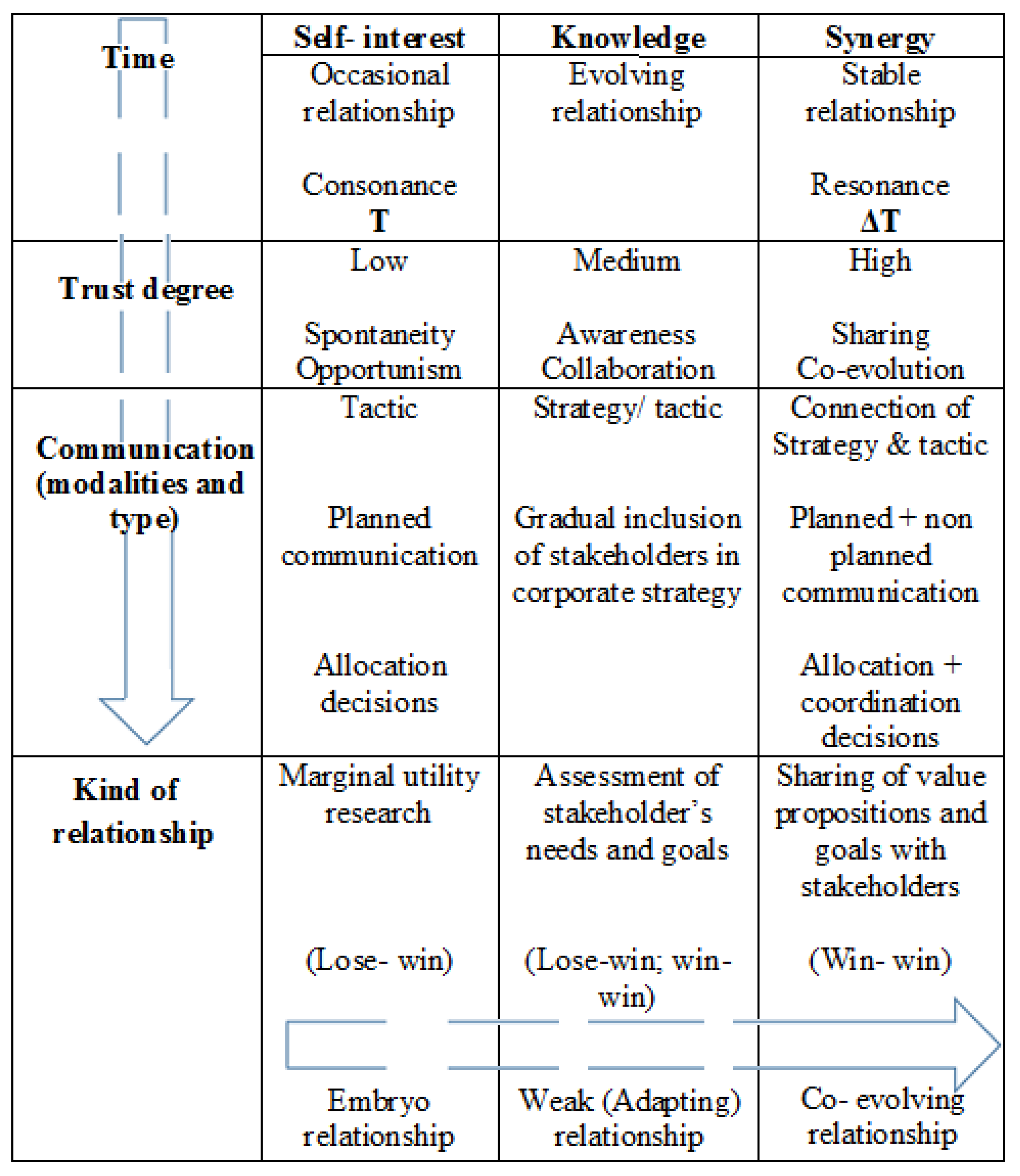

3. Redesigning Boundaries in a Systemic-Relational Service Perspective

3.1. Systemic Conception of Organizational Boundaries

3.2. The Relational Criterion: From Self-Interest to Synergic Relationships

4. Implications and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shipilov, A.; Godart, F.; Clement, J. What boundaries? How mobility networks across countries and status groups affect the creative performance of organizations. Strateg. Manag. J. 2016, 38, 1232–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Yang, J. Production of boundaries by social service organizations: Based on the study of family integrated service centers in Guangzhou. J. Chin. Sociol. 2016, 3, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilden, A. System and Structure: Essays in Communication and Exchange Second Edition; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Paulsen, N.; Hernes, T. Managing Boundaries in Organizations; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lamont, M.; Molnár, V. The study of boundaries in the social sciences. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2002, 28, 167–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyatt, D.G.; Johnson, J.L. Expanding boundaries: Nongovernmental organizations as supply chain members. Elementa 2016, 4, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W.R.; Davis, G.F. Organizations and Organizing: Rational, Natural and Open Systems Perspectives; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Coase, R.H. The nature of the firm. Econ. New Ser. 1937, 4, 386–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmqvist, M. Learning in imaginary organizations: Creating interorganizational knowledge. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 1999, 12, 419–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schotter, A.; Abdelzaher, D. The boundary spanning effects of the Muslim diaspora on the internationalization processes of firms from organization of Islamic conference countries. J. Int. Manag. 2013, 19, 82–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenza, G.; Loia, V.; Orciuoli, F. Providing Smart Objects with Intelligent Tutoring Capabilities by Semantic Technologies. In Proceedings of the Intelligent Networking and Collaborative Systems (INCoS) Conference, Ostrava, CZ, USA, 7–9 September 2016; pp. 103–109. [Google Scholar]

- Loia, V.; Maione, G.; Tommasetti, A.; Torre, C.; Troisi, O.; Botti, A. Toward smart value co-education. In Smart Education and E-Learning 2016; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2016; pp. 61–71. [Google Scholar]

- Ciasullo, M.V.; Polese, F.; Troisi, O.; Carrubbo, L. How Service Innovation Contributes to Co-Create Value in Service Networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Exploring Services Science, Bucharest, Romania, 19 May 2016; pp. 170–183. [Google Scholar]

- Troisi, O.; Tuccillo, C. A re-conceptualization of port supply chain management according to the service dominant logic perspective: A case study approach. Esper. D’impresa 2014, 2, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciasullo, M.; Troisi, O. Sustainable value creation in SMEs: A case study. TQM J. 2013, 25, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barile, S.; Polese, F. Smart service systems and viable service systems: Applying systems theory to service science. Serv. Sci. 2010, 2, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troisi, O.; Carrubbo, L.; Maione, G.; Torre, C. What’s ahead in service research: New perspectives for business and Society. In Proceedings of the XXVI RESER Conference, Naples, Italy, 8–10 September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschhorn, L.; Gilmore, T. The new boundaries of the “boundaryless” company. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1992, 70, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Teece, D. Profiting from technological innovation: Implications for integration, collaboration and public policy. Res. Policy 1986, 15, 285–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galeotti, M.; Garzella, S. Governo Strategico Dell’azienda; Giappichelli: Torino, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ashkenas, R. The Boundaryless Organization: Breaking the Chains of Organizational Structure. In The Jossey-Bass Management Series; Jossey-Bass Inc. Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Abbott, A. Things of Boundaries. Soc. Res. 1995, 857–882. [Google Scholar]

- Gadde, L.E. Moving corporate boundaries: Consequences for innovative redesign. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2013, 49, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heracleous, L. Boundaries in the study of organization. Hum. Relat. 2004, 57, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butera, F. Il Campo di Fragole: Reti di Imprese e Reti di Persone Nelle Imprese Sociali Italiane; Angeli: Milano, Italy, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzoni, G.; Lomi, A. Impresa Guida e Organizzazione a Rete. Accordi Fra Imprese, Reti e Vantaggio Competitivo; Etas: Milano, Italy, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Von Bertalanffy, L.V. General System Theory: Foundations, Development, Applications; George Braziller: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Grandori, A. Impigliati nella rete. Svilupp. Organ. 1998, 170, 97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Castells, M. The Network Society; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Penrose, E.T. The Theory of the Growth of the Firm; Sharpe: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Browne, J.; Zhang, J. Extended and Virtual Enterprises—Similarities and Differences’. Int. J. Agile Manag. Syst. 1999, 1, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantwell, J.A. Blurred boundaries between firms, and new boundaries within (large multinational) firms: The impact of decentralized networks for innovation. Seoul J. Econ. 2013, 26, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Schilling, M.A.; Steensma, H.K. Disentangling the theories of firm boundaries: A path model and empirical test. Organ. Sci. 2002, 13, 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billinger, S.; Jacobides, M.G. Changing the firm’s digital backbone: How information technology shapes the boundaries of the firm. In Proceedings of the BLED 2006, Bled, Slovenia, 5–7 June 2006; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Haak, R. Theory and Management of Collective Strategies in International Business: The Impact of Globalization on Japanese German Business Cooperations in Asia; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ashkenas, R. Management: How to loosen organizational boundaries. J. Bus. Strateg. 2000, 21, 11–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vang-Lauridsen, J. Boundaries of the firm and intellectual production-wrestling with Transaction Costs Economics. In Proceedings of the DRUID Academy Conference, Frederiksberg, Denmark, 6–8 January 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Abelow, D.H. Continuous dynamic boundaries. U.S. Patent Application No. 14/808,100, 24 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dubois, A. Organizing Industrial Activities across Firm Boundaries; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobides, M.G.; Winter, S.G. Entrepreneurship and firm boundaries: The theory of a firm. J. Manag. Stud. 2007, 44, 1213–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, F.M.; Eisenhardt, K.M. Organizational boundaries and theories of organization. Organ. Sci. 2005, 16, 491–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiblein, M.J.; Miller, D.J. An empirical examination of transaction-and firm-level influences on the vertical boundaries of the firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 2003, 24, 839–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanin, M.N.; Shapiro, H.J. Dialectical inquiry in strategic planning: Extending the boundaries. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1985, 10, 663–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacey, R.D. Managing the Unknowable: Strategic Boundaries between order and Chaos in Organizations; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman, H.J.; Schultz, R. Open boundaries: Creating Business Innovation through Complexity; Da Capo Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, O.E. Transaction-cost economics: The governance of contractual relations. J. Law Econ. 1979, 22, 233–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, R.; Winter, S. An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Hamel, G. Leading the Revolution; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Foss, N.J. Knowledge-based approaches to the theory of the firm: Some critical comments. Organ. Sci. 1996, 7, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, L.; Dubois, A.; Gadde, L.-E. The Multiple Boundaries of Firms. J. Manag. Stud. 2003, 40, 1255–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, S.J.; Hart, O.D. The costs and benefits of ownership: A theory of vertical and lateral integration. J. Political Econ. 1986, 94, 691–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W.R. Le Organizzazioni; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Rocchi, F. Conoscenza E Impresa: Un modello Interpretativo; Cedam: Padova, Italy, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Helper, S.; MacDuffie, J.P.; Sabel, C. Pragmatic collaborations: Advancing knowledge while controlling opportunism. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2000, 9, 443–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrero, G. Impresa E Management; Giuffrè: Milano, Italy, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, G.B. The organisation of industry. Econ. J. 1972, 82, 883–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Normann, R.; Ramirez, R. Designing Interactive Strategy: From Value Chain to Value Constellation; Wiley: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Granstrand, O.; Patel, P.; Pavitt, K. Multi-technology corporations: Why they have “distributed” rather than “distinctive core” competencies. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1997, 39, 8–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.; Pavitt, K. How technological competencies help define the core (not the boundaries) of the firm. In The Nature and Dynamics of Organizational Capabilities; Dosi, G., Nelson, R., Winter, S., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 313–333. [Google Scholar]

- Loasby, B.J. The organisation of capabilities. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 1998, 35, 139–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rullani, E. Economia delle reti: I linguaggi come mezzi di produzione. Econ. Politica Ind. 1989, 64, 125–164. [Google Scholar]

- Coda, V. L’orientamento Strategico Dell’impresa; Utet: Torino, Italy, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Garzella, S. I Confini Dell’azienda. Un Approccio Strategico; Giuffrè: Milano, Italy, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Capra, F. The Web of Life; Flamingo: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Laszlo, E. The Systems View of the World a Holistic Vision for Our Time; Hampton Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Mele, C.; Pels, J.; Polese, F. A brief review of systems theories and their managerial applications. Serv. Sci. 2010, 2, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maglio, P.P.; Spohrer, J. Fundamentals of service science. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 2008, 36, 18–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, D.; Kahn, R. The Social Psychology of Organizations; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Golinelli, G.M. Viable Systems Approach (VSA). In Governing Business Dynamics; Cedam: Padova, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Barile, S. Management Sistemico Vitale; Giappichelli: Torino, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Golinelli, G.M. L’approccio Sistemico Al Governo Dell’impresa. L’impresa Sistema Vitale, 1st ed.; Cedam: Padova, Italy, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Barile, S. Contributi Sul Pensiero Sistemico In Economia D’impresa; Arnia: Salerno, Italy, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Barile, S.; Pels, J.; Polese, F.; Saviano, M. An introduction to the viable systems approach and its contribution to marketing. J. Bus. Mark. Manag. 2012, 5, 54–78. [Google Scholar]

- Barile, S.; Polese, F. Linking the viable system and many-to-many network approaches to service-dominant logic and service science. Int. J. Qual. Serv. Sci. 2010, 2, 23–42. [Google Scholar]

- Barile, S.; Saviano, M. Foundations of systems thinking: The structure-system paradigm. In Contributions to Theoretical and Practical Advances in Management. A Viable Systems Approach (VSA); ASVSA, Associazione per la Ricerca Sui Sistemi Vitali; International Printing: Avellino, Italy, 2011; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Barlett, C.A.; Ghoshal, S. Matrix management: Not a structure, a frame of mind. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1989, 68, 138–145. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, I.C.L.; Parry, G.; Maull, R.; McFarlane, D. Complex engineering service systems: A grand challenge. In Complex Engineering Service Systems; Ng, I.C.L., Parry, G., Wild, P., McFarlane, D., Tasker, P., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sunder, S. Regulatory competition among accounting standards within and across international boundaries. J. Account. Public Policy 2002, 21, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, J.V. Boundaries: A relational perspective. Psychother. Forum 1995, 1, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Wieland, H.; Polese, F.; Vargo, S.; Lusch, R. Toward a service (eco) systems perspective on value creation. Int. J. Serv. Sci. Manag. Eng. Tech. 2012, 3, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Reducing the fear of crime in a community: A logic of systems & system of logics perspective. In Proceedings of the Grand Challenge in Service Week: Understanding Complex Service Systems Through Different Lens, Cambridge, UK, 20–23 September 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Maglio, P.; Vargo, S.L.; Caswell, N.; Spohrer, J. The service system is the basic abstraction of service science. Inf. Syst. E-Bus. Manag. 2009, 7, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellicano, M.; Ciasullo, M.V. La Visione Strategica Dell’impresa.; Giappichelli: Torino, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Spigel, B. The relational organization of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2015, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barile, S.; Saviano, M.; Polese, F.; Di Nauta, P. Il rapporto impresa-territorio tra efficienza locale, efficacia di contesto e sostenibilità ambientale. Sinergie Rivista di Studi E Ricerche. 2013, 90, 25–49. [Google Scholar]

- Håkansson, H. International Marketing and Purchasing of Industrial Goods; Wiley: London, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Dyer, J.H.; Singh, H. The relational view: Cooperative strategy and sources of interorganizational competitive advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 660–679. [Google Scholar]

- Nahapiet, J.; Ghoshal, S. Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 242–266. [Google Scholar]

- Pellicano, M.; Ciasullo, M.V.; Monetta, G.; Galvin, M. An In-Depth Study of Public Administrations: The Shift from Citizen Relationship Management to Stakeholder Relationship Governance. In Proceedings of the Toulon-Verona Conference “Excellence in Services”, Palermo, PA, Italy, 31 August–1 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fenza, G.; De Maio, C.; Loia, V.; Tommasetti, A.; Troisi, O.; Vesci, M. Contextual fuzzy- based decision support system through opinion analysis: A case study at University of Salerno. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Decis. Mak. 2016, 15, 923–948. [Google Scholar]

- Velotti, L.; Botti, A.; Vesci, M. Public-Private Partnerships and Network Governance: What Are the Challenges? Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2012, 36, 340–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, B.; Pickton, D. Integrated marketing communications requires a new way of thinking. J. Mark. Commun. 1999, 5, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Santo, M.; Pietrosanto, A.; Napoletano, P.; Carrubbo, L. Knowledge based service systems. In System Theory and Service Science: Integrating Three Perspectives in a New Service Agenda; Gummesson, E., Mele, C., Polese, F., Eds.; IGI Global: Naples, Italy, 9–12 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Flint, D.J.; Lusch, R.F.; Vargo, S.L. The supply chain management of shopper marketing as viewed through a service ecosystem lens. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2014, 44, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breidbach, C.; Brodie, R.; Hollebeek, L. Beyond virtuality: from engagement platforms to engagement ecosystems. Manag. Serv. Qual. 2014, 24, 592–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brander, L.M.; Wagtendonk, A.J.; Hussain, S.S.; McVittie, A.; Verburg, P.H.; de Groot, R.S.; van der Ploeg, S. Ecosystem service values for mangroves in Southeast Asia: A meta-analysis and value transfer application. Ecosyst. Serv. 2012, 1, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, M.; Hinttu, S.; Kock, S. Relationships of cooperation and competition between competitors. In Proceedings of the 19th Annual IMP Conference, Lugano, Switzerland, 4–6 September 2003; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Agranoff, R.; McGuire, M. Collaborative Public Management: New Strategies for Local Governments; Georgetown University Press: Georgetown, WA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hallahan, K.; Holtzhausen, D.; van Ruler, B.; Verčič, D.; Sriramesh, K. Defining strategic communication. Int. J. Strateg. Commun. 2007, 1, 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriramesh, K.; Verčič, D. The mass media and public relations. In Global Public Relations Handbook, Revised and Expanded Edition: Theory, Research, and Practice; Routledge: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Golinelli, G.M.; Gatti, M. L’impresa sistema vitale. II governo dei rapporti intersistemici. Emerg. Issues Manag. 2001, 2, 53–81. [Google Scholar]

- Ballantyne, D.; Varey, R.J. Creating value-in-use through marketing interaction: The exchange logic of relating, communicating and knowing. Mark. Theory 2006, 6, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Concept | Assumption |

|---|---|

| Society | Society can be understood as a network of more or less extensive and structured relations |

| Social structure is taken as a persistent pattern of relationships among all social positions | |

| Social structure is configured through networks, that is, sets of nodes and links that indicate their interconnections | |

| Social structure can be conceptualized in terms of durable patterns of relationship among multiple social actors | |

| Actors | Each actor interacts with others influencing their behaviour |

| Actors move among the social spaces generated by the intersection of different relational fields, in which every person plays a different social role and assumes a different position | |

| Actors and their actions are autonomous and interdependent (but not independent) units | |

| Network | Network models are structural environments that provide opportunities or constraints to individual actions |

| The pattern of social ties in which actors are inserted produces consequences determinant for them | |

| Relational links among actors allow for the transfer or the flow of material and immaterial resources |

| Criterion | Description | Limits |

|---|---|---|

| Transaction costs | Organizational boundaries depend on the level of transactions and the responsiveness of performed transactions | Static orientation due to the idea according to which transactions depend on lots of complex dynamics, often difficult to predict |

| Contractual-legal | Organizational boundaries are influenced by the type and entity of formal agreements reached with other parties | No consideration of the circumstances in which an organization engages relationships based on informal characteristics |

| Ownership | A resource is understood as internal only whether it is owned by organization or is linked to it by a legal relationship comparable to the property right | Interpretive distortions in evaluating human resources |

| Space-time barriers | A resource is internal whether it is within the spatial (e.g., in stock) or time (e.g., at a certain hour) scope of organization | Not adequate with intangible resources (services) |

| Interest sharing | Resources having interests in common or pursuing shared objectives are considerable as internal | Organization is a syncretic system in which there are many different interests and goals |

| Job sharing | Organizational boundaries depend on the type of the undertaken activities and on how these ones fit together | The progressive trend towards the dematerialization of activities complicates to establish whether they are essential or marginal for organization’s existence and development |

| Specific competences | The specific competences (direct knowledge) of an organization allow defining its size | Although the organization’s know-how spins mainly around distinctive skills, it includes not only them, but also indirect competences |

| Communication | Only the resources capable of communicating with each other should be understood as internal | Distinct entities could be able to communicate with each other through the use of the same language without necessarily belonging to the same system |

| Governance action and autonomy | Boundaries are understood as a transition zone between inside and outside, which circumscribes resources and activities on which organization is able to exercise its discretionary power and extend its influence and control | Excessive discretion in the identification of boundaries |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Crespo Garrido, M.J.; Grimaldi, M.; Maione, G.; Vesci, M. Inside Out: Organizations as Service Systems Equipped with Relational Boundaries. Systems 2017, 5, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems5020036

Crespo Garrido MJ, Grimaldi M, Maione G, Vesci M. Inside Out: Organizations as Service Systems Equipped with Relational Boundaries. Systems. 2017; 5(2):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems5020036

Chicago/Turabian StyleCrespo Garrido, María Jimena, Mara Grimaldi, Gennaro Maione, and Massimiliano Vesci. 2017. "Inside Out: Organizations as Service Systems Equipped with Relational Boundaries" Systems 5, no. 2: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems5020036

APA StyleCrespo Garrido, M. J., Grimaldi, M., Maione, G., & Vesci, M. (2017). Inside Out: Organizations as Service Systems Equipped with Relational Boundaries. Systems, 5(2), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems5020036