Abstract

Climate change and environmental degradation necessitate green innovation (GI) to provide new solutions for sustainable economic growth. As many firms allocate scarce resources to green innovation, researchers, practitioners, and policymakers are keen to understand information disclosure on green innovation, particularly in company financial statements. This study empirically investigates the relationship between GI and conservative financial reporting. Using a dataset of 8945 unique firms, from 2001 to 2024, we discover a negative relationship between GI and conservative financial reporting. We further document that firms with high exposure to climate change exhibit a more pronounced negative relationship between GI and conservative financial reporting. In addition, we find that the presence of regulatory risks and public awareness, particularly after the adoption of the Paris Agreement, weakens the negative association between GI and conservative financial reporting. Our findings shed further light on information disclosure on green innovation, which is crucial for various stakeholders to utilize such information and make relevant decisions.

1. Introduction

Since the 1980s, public pressure has demanded that corporations deal with the existing environmental problems [1]. For example, in June 1989, U.S. President Bush introduced comprehensive revisions to the Clean Air Act to address significant environmental and public health challenges.1 In recent years, the number of concerns related to sustainable development and environmental protection has skyrocketed among organizations and academics, as environmental issues and the limitation of natural resources are now considered a threat to human survival [2,3,4].

International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) require mandatory CSR disclosures to account for climate change risks and their potential effects on firms. In December 2004, the International Financial Reporting Interpretations Committee (IFRIC) released Article 3, Emission Rights, to help firms account for their involvement in emissions trading schemes; firms should disclose relevant policies, transactions, and balances [5]. In addition, according to Article 38, firms should assess the feasibility of emission allowances, the availability of future economic benefits, and the reliability of the expense measure, and implement the necessary measures related to intangible assets and their disclosure [6].

The 2030 Agenda, issued by the United Nations (UN) in 2015, includes 17 sustainable development goals that aim to maintain a sustainable future.2 More recently, as investors have increasingly begun to demand corporations’ assessments on the risks and long-term sustainability of the business, in 2021, the IFRS developed the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB), which established global standards on the disclosure of sustainability-related information. Specifically, the IFRS requires corporations and organizations to disclose business information, such as climate-related risks, which may influence cash flows, financing, and the cost of capital in the short and long term.

These acts and strategies indicate the increasing global pressure on corporations to respond efficiently and effectively to environmental deterioration during their business operations. One of the responses by companies is the adoption of green innovation [7]. Green innovation (GI) is a type of innovation that reduces the negative environmental impacts of business production through corporations’ efforts to achieve environmental goals, including the introduction of new environmentally friendly products and services, and the improvement of current technologies [8]. Corporations can implement GI through the initiation of sustainable activities and the achievement of green business transformation [9]. Duque-Grisales et al. [10] state that corporations with a high level of GI gain competitive advantages by providing customers with environmentally friendly products and services, which have higher economic value in terms of the customers’ opinion.

The rising awareness of the importance of GI motivates researchers to explore the relationships between GI and organizational performance, such as firms’ financial performance [11], financial decision making [3], and corporate social responsibility (CSR) [12]. Building on this line of research, we intend to investigate whether and to what extent GI may affect firms’ financial reporting practices. In particular, we focus on accounting conservatism, which is an accounting practice that demands firms to more quickly recognize bad news than favorable news [13]. Many researchers have shown that the implementation of accounting conservatism leads to a higher level of accounting disclosure [14] and better information environment [15], reduces stock price synchronicity [16] and agency costs [17,18], and increases investment efficiency [19]. However, the evidence is still scant on the relationship between GI and firms’ conservative financial reporting. The relationship between GI and accounting conservatism is of more significance due to the growing emphasis on sustainability and corporate transparency. As firms increasingly engage in GI to address environmental challenges, we are therefore motivated to understand how this initiative may affect conservative accounting practices, which are linked to better financial decision making, improved corporate governance, and more reliable financial reporting. Unraveling this relationship offers valuable insights into how sustainability efforts impact corporate financial transparency and investor expectations, which is particularly relevant for investors seeking to assess the financial quality and future performance of green innovative firms.

In addition, we intend to further investigate the role of external public awareness of sustainability, corporate climate risk exposure, and corporate environmental regulatory risk on the relationship between GI and accounting conservatism.

We construct a panel of data consisting of 8945 unique firms, during the period from 2001 to 2024. To measure accounting conservatism, our dependent variable, we use the C-score, as defined by Khan and Watts [20]. We measure GI, our main independent variable, as the natural logarithm of the yearly green patent counts of firms obtained from the USPTO. The baseline regression indicates that GI is negatively associated with accounting conservatism. Our empirical results are consistent, after we address the endogenous concerns, as suggested by Rosenbaum and Rubin [21], to mitigate potential selection bias. We also perform robustness tests, including (i) using an alternative measure of accounting conservatism, and (ii) focusing on manufacturing firms. When we subsample our dataset based on the degree of climate change exposure, we find that the negative relationships are strengthened among firms with higher than median climate change exposure. However, when we further subsample our dataset based on regulatory risk, we discover a weakened negative relationship between GI and accounting conservatism. The heightened public awareness of climate change risk also weakens the negative relationship between GI and accounting conservatism when we implement the Paris Agreement as an external shock mechanism in terms of generating higher public awareness of climate change risk.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the related literature on GI and accounting conservatism and develops several hypotheses. Section 3 provides details on the data, sample, and measures of the variables used in our research. Section 4 reports on the empirical results, and Section 5 summarizes the results and provides the conclusion.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Green Innovation

Chen et al. [22] define green innovation as innovations related to green products. With the increasing social awareness on environmental protection, GI becomes widely accepted as a viable strategy to achieve economic development by society and to achieve environmental management by firms [23]. The existing literature divides the leading factors of GI into two broad categories, internal and external. The internal factors typically come from inside companies, such as resources and innovation capabilities. For example, Hao et al. [24] found that enterprise scales and firm age have effects on GI, and Li et al. [25] found that large corporations develop GI to enhance their competitiveness in the market.

On the other hand, the external driving factors are mainly related to regulations and public pressure. Stakeholders play important roles in the development of GI. For instance, environmentally conscious customers are more willing to purchase environmentally friendly products [26], and environmentally friendly suppliers provide firms with materials and technologies that help firms promote GI [27]. Tax incentives also encourage firms to invest more in GI [28]. Also, GI helps corporations attract financial support from governments and helps alleviate financial constraints [29].

Researchers have shown that a positive relationship exists between GI and organizational performance using market-based metrics, as GI offers firms the ability to boost their green reputation [30] and secure a competitive advantage [31], and helps firms meet stakeholders’ requirements [4]. In contrast, Yao et al. [32] showed that there was a negative relationship between GI and the market value of manufacturing firms because of the high additional costs. The inconclusive results also left the empirical relationship between GI and organizational performance in regard to market-based perspectives unresolved.

2.2. Accounting Conservatism

Accounting conservatism, also known as conservative financial reporting, is an accounting practice that demands that firms more quickly recognize bad news (i.e., adverse losses) than favorable news (i.e., gains). The purpose of this asymmetric accounting practice is to provide the users of financial statements with a more reliable and realistic assessment of firms’ organizational performance, mainly their financial performance, by intentionally understating the value of gains and overstating the value of losses [13]. Many researchers have shown that the implementation of accounting conservatism leads to a higher level of accounting disclosure [14] and a better information environment [15], reduces stock price declines [16] and agency costs [17,18], and induces investment efficiency [19]. Mainly due to the benefits of accounting conservatism, it has become a widely used attribute in the financial reporting of company earnings.

CSR activities are an important aspect of firms’ organizational performance. The existing literature reports mixed impacts of CSR activities on financial reporting. For example, Petrovits [33] points out a positive relationship between CSR and earnings manipulation, because management may choose to engage in certain CSR activities to achieve its earnings targets. Similarly, Chih et al. [34] discovered that CSR activities induce earning aggressiveness. These results uncover the fact that some management teams engage in CSR activities for the purpose of earnings manipulation. Therefore, there is a negative relationship between organizational performance and accounting conservatism in the context of increasing earnings manipulation. However, Kim et al. [35] challenge this negative relationship by proving that CSR constrains earnings management. To sum up, CSR has mixed effects on accounting conservatism.

CSR disclosure has mixed effects on accounting conservatism. Some researchers have shown positive relationships between CSR disclosure and conservative reporting, as it decreases the probability of managerial opportunism and earnings management [35] and fraud [36]. As CSR disclosures provide more reliable financial information, there is a positive relationship between CSR disclosure and accounting conservatism. However, Guo et al. [37] found that CSR disclosure reduces agency problems, which in turn leads to less demand for conservative reporting from stakeholders. Overall, the relationship between CSR disclosure and accounting conservatism needs to be further investigated.

2.3. Green Innovation and Accounting Conservatism

The main argument in terms of the potential relationship between GI and accounting conservatism heavily relies on stakeholder theory. According to this theory, GI will have a positive impact on stakeholders’ wealth because it prioritizes stakeholders’ interest and enhances the sustainable operations desired by stakeholders [38]. More precisely, GI captures the companies’ capabilities in terms of developing new products and technologies to mitigate environmentally related risks, capabilities that are highly valued in the current business environment. Meeting environmental needs helps firms not only gain competitive advantages [10], but also create value for stakeholders [11] by fulfilling stakeholders’ interests.

In addition to value creation, GI helps build stakeholders’ relationships and, therefore, reduces stakeholders’ concerns with corporate decision making. The existing literature proves that green innovative firms yield profits for shareholders [39], fulfill contracting obligations in regard to creditors [40], and meet customers’ and suppliers’ needs [10]. By fulfilling contracting roles and maintaining long-term relationships with stakeholders, the management of green innovative firms involves managerial opportunism and the potential for earnings management [35] and fraud [36].

The demand for accounting conservatism arises depending on the degree of managerial opportunism and the agency problem [41]. As Harjoto and Laksmana [42] further prove that CSR engagement negatively affects optimal risk taking, GI also reduces managerial opportunism. Goss and Roberts [43] consider CSR engagement as a transformation of shareholders’ value maximization into the fulfillment of stakeholders’ interests, which significantly reduces agency problems. In addition, CSR disclosure provides non-financial information and serves as a substitute mechanism to offset low-quality accounting disclosures, a leading cause of agency problems [44]. In conclusion, we hypothesize that a negative relationship exists between GI and accounting conservatism.

Next, information asymmetry theory also plays a role in explaining the relationship between GI and accounting conservatism. Even though green innovative firms in the U.S. are not subject to mandatory requirements on CSR disclosure, management are still willing to voluntarily disclose their CSR activities as non-financial information [45], and to ensure the credibility of CSR information [46]. In regard to CSR disclosures, green innovative firms offer high-quality financial reporting information, which increases the accuracy of investors’ financial forecasts [47] and mitigates information asymmetry between insiders and outsiders.

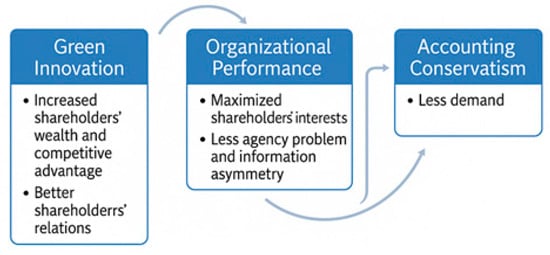

GI also enhances a more transparent information environment as the corporation’s stakeholders can gather and exchange information dynamically and freely, as Cui et al. [48] found that information asymmetry decreases in capital markets because of CSR activities. As a higher level of information asymmetry leads to higher demands for conservative reporting practices [15], we hypothesize that a negative relationship exists between GI and accounting conservatism as we conclude in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

3. Data, Variables, Summary Statistics, and Methodology

3.1. Data and Sample

We identified our sample of public companies using Compustat during the period from 2001 to 2024. We excluded financial institutions and insurance companies from our sample database. We also eliminated firms outside the U.S. mainland, those with missing or those that had non-positive asset values, and those that had a non-positive book value of equity, less than a USD 1 price per share, and those that had non-negative sales revenues [20].

We merged our hand-matched green patent dataset (discussed in Section 3.3) into the identified Compustat dataset. The control variables required for our estimation were also from Compustat. We excluded extreme values including market-to-book ratios (MTB) greater than 10 and sales growth rates greater than 2. The final sample of companies included firms distributed across different sectors, as represented by the four-digit SIC codes that identify a specific industry within a broad industry group. The first two digits represent the major industry group, the third digit indicates the industry group, and the fourth digit signifies the specific industry within that group.

Panel A of Table 1 indicates that there were 8945 unique firms included in Compustat from 2001 to 2024. Next, as we further merged the green patent data into Compustat, our main dataset, we wanted to look for the earliest time at which each green innovative company appeared in Compustat. The purpose of this was to capture each company’s organizational performance as much as possible, so that we generated consistent and robust findings on the relationship between green innovation and accounting conservatism. We further display the firms’ earliest year of appearance in the databased in Panel C of Table 1, which relates to the yearly distribution of the firms in our dataset.

Table 1.

Firm sector and year selection and distribution.

Panel C of Table 1 indicates that 45 percent of the unique firms in our final merged dataset first appeared in or before 2001. However, this finding does not imply that 45% of all the data used in our regressions are drawn exclusively from the year 2001. Rather, these firms have continuous data long before 2001 in Compustat and are included in our panel across multiple years. This finding indicates that over 45 percent of green innovative firms have operated for at least 20 years, revealing an interesting fact that the mature firms with greater years of operation and access to resources, such as more financial resources, tend to adopt green innovative practices at later stages of their business operations. As we obtained the data in our Compustat dataset up until August 2024, the number of firms first observed in the year 2024 is less than that of the other years.

3.2. Accounting Conservatism

To compute the accounting conservatism measure, we gathered company financial data from Compustat and monthly stock return data from the CRSP for the period from 2000 to 2024. Following Basu [13] and Khan and Watts [20], we excluded firms with missing data of variables used in accounting conservatism estimation, excluded firm year observations including negative assets, a negative book value of equity, and negative sales revenues, as well as observations concerning a fiscal year end price of less than USD 1 fiscal per share. We cumulated the CRSP monthly returns starting from the fourth month after the fiscal year end to obtain the corporation’s annual return [13,20]. Using the conditional accounting conservatism measure developed by Khan and Watts, we aimed to examine the empirical relationship between GI and accounting conservatism.

Accounting conservatism places a higher threshold on recognizing gains than losses and leads to an asymmetric timeliness in terms of earnings for gains and losses and a constant and cumulative understatement of book and market values [13]. Conditional conservatism is sensitive to ex post news and income statement-related information [49], so it is responsive to current news and reflects more quickly the recognition of negative earnings [50]. The following linear regression estimates Basu’s [13] measure of accounting conditional conservatism, in regard to the asymmetric timeliness of earnings:

is the net income before an extraordinary item scaled by a lagged market value of equity for firm i in year t. is a dummy equaling one if firm i’s return is negative in year t, and zero otherwise. is the annual return for firm i in year t. The coefficient, , captures the asymmetric timeliness of earnings, reflecting that bad news is recognized earlier than good news. If a company adopts conservative reporting practices, the coefficient value is positive and, the higher the coefficient value, the more conservative the reporting practice.

However, Khan and Watts [20] argue that this single coefficient may not only capture conservatism, but also other firm-specific noise. To address this concern, they propose a refined model in which the sensitivity to bad news is modeled as a function of firm characteristics, firm size, the market-to-book ratio, and leverage. They enable the coefficients in Basu’s model to vary cross-sectionally with these characteristics, which results in a firm–year level estimate of conservatism, known as the C-score. Therefore, following Basu [13], Khan and Watts [20] develop a new accounting conservatism measure, the C-score, by introducing firm size, leverage, and the market-to-book ratio of equity (MTB) into Basu’s [13] model:

Size is the natural log of the market value of equity, MTB is the ratio of the market value of equity to the book value at the end of the year, and leverage is the sum of short- and long-term liabilities scaled by the market value of equity. We regress model (2) to obtain the cross-sectional estimates, to , and calculate the C-score using the following model:

In this framework, the C-score represents the firm-specific responsiveness of earnings to bad news, taking into account how conservatism may vary systematically across firms with different risk and reporting incentives. In other words, when a firm receives bad news, the degree to which its earnings are written down, adjusted according to its size, valuation, and leverage, is interpreted as its degree of accounting conservatism. Therefore, the C-score derived from the interaction terms in Khan and Watts’s [20] model provides a more tailored and reliable measure of conditional conservatism. The C-score, the firm–year incremental bad news timeliness, is our main measure of conditional accounting conservatism. The higher the C-score, the greater the accounting conservatism. In other words, firms with a high C-score report more conservative accounting numbers on their financial statements to their shareholders than those with a low C-score, and vice versa.

3.3. Green Innovation

GI is the main independent variable in our study. Given the fact that GI is a qualitative and intangible factor, the standards of GI vary according to the research purpose. Researchers have used questionnaire surveys, green innovative productivity, green-related R&D and annual reports, and CSR scores to quantify GI [11,12,51,52,53]. However, questionnaires may contain significant deviations and green-related R&D and annual reports are difficult to obtain. An alternative way to measure GI is using green patent data [24,54], as Berrone et al. [55] argue that patents robustly capture the level of GI.

We retrieved patent information from the USPTO. Since the patent dataset from the USPTO contains information of green and non-green patents, to correctly capture green patents, we referred to the Cooperative Patent Classification (CPC) Scheme and Definitions for patent classifications and descriptions, and we then hand-matched the green-related patents according to the classifications. For example, the patent category, D01F 13/00, describes patents related to the recovery of starting materials, waste materials, and solvents during manufacturing, which matches our goal of environmental protection. Most importantly, section Y of the CPC Scheme and Definition categorizes innovations related to climate change protection; therefore, we included all the patents with a Y subclass in our green patent database.

After the hand-matching process, we associated the green patents with the relevant firm making the application. We link the green patents in the USPTO database with the relevant firms using PERMCO numbers, unique permanent identification numbers, assigned by the CRSP to all the companies.3 Next, we merged the green patent dataset with our calculated annual return CRSP dataset, which was further merged with the Compustat dataset for the purpose of our research.

3.4. Control Variables

We incorporated many control variables, discussed in various pieces of existing literature on accounting conservatism. LaFond and Watts [15] argue that firms with noticeable growth prospects are more willing to adopt liberal accounting practices, so we controlled for the firm size measured as the natural logarithm of the total assets. Leverage leads to conflicts in regard to shareholders’ interests and agency problems, as suggested by Ahmed and Henry [50], and, thus, increases the level of conservative reporting practices. As a result, we included leverage as a control variable, measured as the sum of short- and long-term liabilities, scaled according to the total assets. A higher MTB ratio is associated with reduced accounting conservatism [56]; therefore, we controlled for such a factor as the ratio of the market value of equity to the book value of equity.

As greater sales growth rates encourage less conservative reporting [15], we accounted for sales growth as the percentage change in the sales from the previous period to the current period. Francis and Wang [57] provide evidence that firms audited by Big 4 accounting firms tend to display greater accounting conservatism. We then controlled for the effects of Big 4 accounting firms by including two dummies, Big 4 Indicator, equaling 1 if the observed firm was audited by one of the Big 4 accounting firms, and 0 otherwise, and Auditor Opinion equaling 1 if the auditing firm issues anything other than an unqualified opinion, and 0 otherwise. We also controlled for firms’ investment in long-term assets, namely capital expenditure.

3.5. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Matrix

In Table 2, we present descriptive statistics of the variables. The mean and median of the C-score are 0.20 and 0.19, respectively, indicating that firms, in general, adopt conservative accounting practices in regard to their financial reports. The mean and median of GI, the natural logarithm of green patent counts, are 0.13 and 0, respectively, signaling that there are some entities with a significant number of green patents, and that company sustainability still needs improvement.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

The means of the control variables are as follows: size 20.49, capital expenditure 0.04, leverage 0.21, MTB 2.35, sales growth 0.09, Big 4 Indicator 0.66, and Auditor Opinion 0.04. The median and 75th percentile of the Big 4 Indicator values show that over half of the observed firms are audited by Big 4 accounting firms. The median and 75th percentile of the Auditor Opinion dummy values indicate that over 75% of the observed firms fairly represent their accounting numbers. The inclusion of two dummy variables helped ensure that the observed firms in our study did not intentionally practice aggressive accounting, which helped us reduce the probability of less conservative reporting caused by management’s attempts at earning manipulation.

Table 3 presents Pearson’s correlation matrix for the variables. We cautiously checked the correlations to ensure that multicollinearity was not a concern. Moreover, we also performed variance inflation factor (VIF) tests and the test results show that the test scores from the VIF tests are all below 5, indicating that multicollinearity was not a concern.

Table 3.

Pearson’s correlation matrix.

3.6. Methodology

In this subsection, we examine the relationship between GI and accounting conservatism using the following model:

The C-score in model (4) refers to the measure of accounting conservatism. Our main independent variable is Lngreen Patent, which is the natural logarithm of the green patent count. Detailed information on the control variables in the model can be found in Section 3.4. The purpose of our OLS baseline regression is to generally examine whether there is a relationship between GI and accounting conservatism. We used OLS regression for the contingent analysis of the Paris Agreement variable to explore whether public awareness has an impact on the general relationship between GI and accounting conservatism. Similarly, we also conducted supplemental contingent analyses of the firms’ climate risk exposure and the litigatory risks to examine whether the general relationship between GI and accounting conservatism is strengthened or mitigated in regard to a different contingency.

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Baseline Regression

The significant coefficient (−0.0215) in Column (3) of Table 4 supports our hypothesis that when the other factors remain constant, a one-unit increase in GI can negatively influence accounting conservatism. Our regression results also support the understanding that the firm size, sales growth, and market-based financial performance all have negative associations with accounting conservatism [15,20,58].

Table 4.

Baseline regression results.

We implemented a propensity score matching (PSM) approach to affirm that our baseline results were not influenced by the differences in the control variables between the firms. This approach helps address selection bias arising from firm-specific characteristics [21]. To perform PSM, we first set the treatment group as the firms with at least one green patent count and the control group as the firms with no green patent count. Next, we match-treated and controlled the firms in the groups with a caliper of 0.05 in regard to the replacement of the firms based on the control variables used in the baseline regression (Table 4). Note that our sample size was reduced because not every treatment firm had matching firms in the control group. Finally, we regressed accounting conservatism using the matched samples from our PSM approach and report the results in Table 5.

Table 5.

Propensity score matching.

Panel A of Table 5 displays the univariate test results in terms of the mean between the treatment and the control group. In addition, we also report the t-statistics for the corresponding control variables used. The statistical significance results in Panel A indicate that there is no statistically significant difference in the firm characteristics captured in regard to the control variables, proving that the PSM removes the disparities for the two groups. Panel B of Table 5 is an ex post PSM regression used to support the robustness of our baseline results. The statistically significant negative coefficient of the lngreen patent variable shows that our baseline results remain unchanged.

4.2. The Contingent Effect of Climate Change Exposure

Climate change is a major business risk due to recent global environmental disasters [49], causing direct damage to firms’ assets or indirect damage to supply chain networks [59]. The existing literature related to climate change has noted that investors perceive climate change exposure as a business risk and believe that climate change exposure has negative impacts on both the financial and non-financial performance of firms [59,60]. As a result, as stakeholders demand more in terms of corporations’ assessment and disclosure of climate change risks and opportunities [60], there is a positive relationship between climate change exposure and accounting conservatism [49]. Supporting this positive relationship, Wu et al. [61] showed that firms located in highly polluted cities have a higher level of accounting conservatism. As GI helps to reduce the effects of climate change risk on organizational performance, we expect GI to reduce accounting conservatism in the context of firms with high levels of climate change exposure.

Sautner et al. [62] developed a measure of firm-level climate change exposure in regard to predicting the outcomes of organizational performance associated with the transition to net zero. Their measure adopts a machine learning-based keyword discovery algorithm to identify exposures related to climate change, including those related to opportunities and regulatory impacts. They focus on the frequency of terms like ‘risks’ and ‘uncertainties,’ along with their synonyms, in sentences that address climate change-related topics.

We consolidated the firm-level values of climate change exposure provided by Sautner et al. [62] into our sample. To test this notion, we divided our sample into firms with higher than median climate change exposure and firms with lower than median climate change exposure, and generated a dummy equaling 1 if the observed firms were highly climate change-exposed firms, and 0 otherwise. We assessed the interaction between the dummy variable and the lngreen patent variable.

Table 6 presents the regression results. The negative coefficient, −0.0203, of the interaction term illustrates that green innovative firms that have greater climate change exposure tend to report less conservatively. In conclusion, GI has a more pronounced negative effect on accounting conservatism for firms with higher climate change exposure.

Table 6.

The contractual contingency of climate risk exposure.

4.3. The Contingent Effect of Regulatory Risk

GI bears high opportunity costs, as it requires significant inputs of knowledge and resources, and investors often associate it with slow and low returns, as it is a long-term project [11]. Because of the high opportunity costs and the complex nature of GI, CSR disclosure is becoming a mandatory legal requirement in more and more countries. This type of mandatory disclosure is an important mechanism for firm legitimacy as it effectively prevents management from not fulfilling stakeholders’ interests and undermining the company’s legitimacy [35,44]. Researchers suggest that regulatory decisions impose greater conservative bias on conservative reporting practices [49,63]. Therefore, we hypothesize that green innovative firms facing higher regulatory risks report more conservatively in response to mandatory CSR disclosure laws.

Sautner et al. [62] also include in their dataset corporations’ regulatory risk related to climate change. To examine our hypothesis, we divided our sample into firms with above median regulatory risk and those with below median regulatory risk, and create a dummy, high regulated risk, equaling 1 for high regulatory risk firms, and 0 otherwise. Next, we assessed the interaction between the dummy variable for high regulated risk and the lngreen patent variable.

In Table 7, we document a positive coefficient (0.0261, p < 0.05) of the interaction term, which indicates that when firms face high regulatory risk, the negative effect of green innovation on accounting conservatism is reversed, indicating that high regulatory risk mitigates the negative relationship between green innovation and accounting conservatism.

Table 7.

The contingent role of regulatory risk.

4.4. The Contingent Effect of the Paris Agreement

The Paris Agreement, adopted in December 2015, during COP 21, is a legally binding international treaty signed by 196 parties [49]. It aims to raise public awareness about climate changes by strengthening global efforts to combat climate change. Following the existing literature, we treated the Paris Agreement as an external shock factor to examine the contingent effects of public awareness on accounting conservatism.

Ferdous et al. [49] suggest that heightened public awareness will have positive impacts on accounting conservatism because stakeholders with climate risk concerns require firms to report more conservatively. Moreover, Ginglinger and Moreau [64] document that increased public awareness leads companies to disclose more about the long-term climate-related risks faced by the business. Therefore, we predict that increased public awareness weakens the negative relationship between GI and accounting conservatism as stakeholders demand a higher level of disclosure. We focused on the three-year window proceeding the Paris Agreement in 2015 and the time period from 2015 onward. To test our hypothesis, we created a dummy, Paris, equaling 0 for observations from 2012 to 2014, and 1 for observations starting in 2016. Our sample size was reduced due to the inclusion of the dummy constructed from 2012 and onward. We then assessed the interaction between the Paris variable with the lngreen patent variable, the main independent variable, to derive the interaction variable for our analysis.

Our findings, reported in Table 8, suggest that after the Paris Agreement was adopted, firms were more likely to have more conservative reporting practices in response to the increased demand for disclosures. In conclusion, the negative relationship between GI and accounting conservatism is weakened for firms facing greater stakeholder pressure on their climate-related risk disclosures.

Table 8.

The contingent role of the Paris Agreement.

4.5. Robustness Tests

In this section, we supplement the baseline regression in model (4) with an alternative conditional accounting conservatism measure to ensure that the baseline results are not sensitive to the usage of accounting conservative measures. It is worth noting that we focus on manufacturing firms to ensure that our main results hold true for manufacturing firms, and, accordingly, our sample size is reduced, as per Table 9. Column (1) presents the regression results for the alternative conditional accounting conservative measure, and Column (2) displays the results for the limited sample of manufacturing firms.

Table 9.

Alternative measure of green innovation and accounting conservatism.

The findings in Table 9 suggest that although we use a different measure of conditional accounting conservatism and limit our sample to only manufacturing firms, the negative relationship between GI and accounting conservatism still holds, ensuring that our main results are not sensitive to the usage of the conditional accounting conservatism measure and other confounding factors.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we document the negative relationship between GI and accounting conservatism. We also show that regulatory risk and public awareness mitigate the negative relationship or even reverse the relationship between GI and accounting conservatism. For firms exposed to greater than the median climate change exposure, we document that the negative relationship is strengthened between GI and accounting conservatism. Our findings are consistent after conducting a series of robustness tests and the consideration of endogenous concerns using the PSM approach to mitigate selection bias.

We contribute to the existing literature in several ways. Firstly, our exploration informs both researchers and practitioners in the fields of sustainability and financial reporting that understanding the interplay between GI and accounting practices is increasingly critical for long-term organizational success. We also provide practical insight for managers and investors that evaluating green innovative firms solely from accounting-based perspectives may not be sufficient, as accounting numbers may be exaggerated when compared to the reality. Investors should adopt more comprehensive viewpoints and incorporate financial metrics and sustainability-related metrics when investing in environmentally friendly innovative firms.

Secondly, the existing literature has noted that better corporate financial performance and higher profitability reduces accounting conservatism [65,66]. Our research connects two streams of research on GI and accounting conservatism by highlighting the negative relationship between green innovation and accounting conservatism. Also, our research further points out a potential research topic, namely that earnings manipulation may occur in the context of green innovation alongside a reduced level of accounting conservatism.

Thirdly, our study contributes to the existing literature by explaining why companies are increasingly interested in pursuing GI. While prior research has shown that exposure to climate change risk positively influences conservative reporting practices [49], we find that GI mitigates the pressure for conservative reporting from stakeholders, leading to more aggressive reporting practices among firms. These findings shed further light on how sustainability initiatives may influence conservative financial reporting, providing a new perspective on the relationship between environmental management and financial disclosure practices.

Our research also has important managerial implications. Firm managers or analysts can use our findings to better utilize firm financial reports to make informed decisions in regard to product markets and capital markets. For other groups of stakeholders, our findings help them to better assess information disclosures related to green innovation and evaluate the real effects on the environment, economy, community, and society.

To the best of our knowledge, we are the first to explore the relationship between green innovation and accounting conservatism. Nonetheless, we are able to draw a robust link between our study and the existing literature. For example, Burke et al. [67] indicate that better CSR performance can reduce the demand for accounting conservatism for firms. As higher climate change risks lead to greater demand for accounting conservatism by firms [49], green innovation lessens the demand for conservative financial reporting because GI can effectively manage environmental issues and alleviate the firm’s exposure to climate risk. Moreover, the existing literature documents that a firm’s financial performance has a negative relationship with accounting conservatism [17,56]. As green innovation increases firms’ financial performance [11,24], firms may recognize better performance in a timely manner, thus reducing accounting conservatism. Therefore, our findings are consistent with and complement the existing research.

We recognize that our study is not without limitations. For example, our sample primarily focuses on firms in the U.S., where disclosures of climate-related risks and green innovation are not mandatory, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to other sectors or geographic regions with different regulatory environments. In countries with stronger investor protection and more rigorous accounting enforcement (e.g., countries implementing IFRS accounting standards), the pressure to maintain accounting conservatism might be higher, potentially moderating the observed relationships. Conversely, in emerging economies, where regulatory oversight is weaker and stakeholder trust mechanisms differ, green innovation could be more closely linked to strategic signaling, amplifying the potential for less conservative accounting practices. Moreover, cultural dimensions, such as uncertainty avoidance, long-term orientation, and collectivism versus individualism, may influence how firms balance innovation with financial reporting practices. Firms in cultures that emphasize transparency and compliance may exhibit more conservative financial reporting in relation to their green innovation activities. Future research can explore similar research questions in global settings, taking into account different legal systems, enforcement mechanisms, and cultural values, thereby enhancing our understanding of the global relevance of our findings.

For regard to another limitation, although we carefully deal with the endogeneity issue by implementing a PSM approach, our sample is subject to double-selection bias. In this sense, firms choose to engage in green innovation and choose their respective financial reporting practices. The existence of double selection may introduce bias into our estimations. In future investigations, researchers can explore possible exogeneous shocks (e.g., regulatory changes) to further validate our findings. More importantly, our research reveals a robust link between GI and firms’ disclosure of their financial information. Future research could extend this line of research to see how capital markets incorporate such information in regard to stock prices, loan contracts, and bond issuances.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.Y. and H.W.; methodology, X.Q. and Z.J.; software, J.H. and Z.J.; formal analysis, X.Q. and Z.J.; writing—original draft preparation, X.Q. and J.H.; writing—review and editing, D.Y. and H.W.; visualization, X.Q. and J.H.; supervision, D.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because of the license requirements of the vendor.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Zixuan Jiao was employed by the company Morgan Stanley. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1. | https://www.epa.gov/clean-air-act-overview/1990-clean-air-act-amendment-summary (accessed on 1 March 2025). |

| 2. | https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 12 March 2025). |

| 3. | https://www.mikewoeppel.com/data (accessed on 2 July 2024). Refer to their website for more information. |

References

- Sharma, S.; Arago, J.A. Corporate Environmental Strategy and Competitive Advantage: A Review from the Past to the Future; Edward Elgar Publishing: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- European Central Bank (ECB). Guide on Climate-Related and Environmental Risks: Supervisory Expectations Relating to Risk Management and Disclosure. Supervisory report. European Central Bank. 2020. Available online: https://www.bankingsupervision.europa.eu/ecb/pub/pdf/ssm.202011finalguideonclimate-relatedandenvironmentalrisks~58213f6564.en.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2024).

- Siegrist, M.; Bowman, G.; Mervine, E.; Southam, C. Embedding environment and sustainability into corporate financial decision-making. Account. Financ. 2020, 60, 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takalo, S.K.; Tooranloo, H.S.; Parizi, Z.S. Green innovation: A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279, 122474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apergis, N.; Eleftheriou, S.; Payne, J.E. The Relationship Between International Financial Reporting Standards, Carbon Emissions, and R&D Expenditures: Evidence from European Manufacturing Firms. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 88, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasileiou, E.; Georgantzis, N.; Attanasi, G.; Llerena, P. Green Innovation and Financial Performance: A Study on Italian Firms. Res. Policy 2022, 51, 104530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Feng, G.; Jiang, R.; Chang, C. Does Environmental, Social, and Governance Performance Move Together with Corporate Green Innovation in China? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 1670–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Walsh, G.; Lerner, D.; Fitza, M.A.; Li, Q. Green Innovation, Managerial Concern and Firm Performance: An Empirical Study. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbate, S.; Centobelli, P.; Cerchione, R. From Fast to Slow: An Exploratory Analysis of Circular Business Models in the Italian Apparel Industry. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2023, 260, 108824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque-Grisales, E.; Aguilera-Caracuel, J.; Guerrero-Villegas, J.; García-Sánchez, E. Does Green Innovation Affect the Financial Performance of Multilatinas? The Moderating Role of ISO 14001 and R&D Investment. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 3286–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casciello, R.; Santonastaso, R.; Prisco, M.; Martino, I. Green Innovation and Financial Performance: The Role of R&D Investments and ESG Disclosure. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 5372–5390. [Google Scholar]

- Mbanyele, W.; Huang, H.; Li, Y.; Muchenje, L.T.; Wang, F. Corporate Social Responsibility and Green Innovation: Evidence from Mandatory CSR Disclosure Laws. Econ. Lett. 2022, 214, 110322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, S. The conservatism principle and the asymmetric timeliness of earnings. J. Account. Econ. 1997, 24, 3–37. [Google Scholar]

- Iatridis, G.E. Accounting disclosures, accounting quality and conditional and unconditional conservatism. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2011, 20, 88–102. [Google Scholar]

- LaFond, R.; Watts, R.L. The information role of conservatism. Account. Rev. 2008, 83, 447–478. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.B.; Zhang, L. Accounting conservatism and stock price crash risk: Firmlevel evidence. Contemp. Account. Res. 2016, 33, 412–441. [Google Scholar]

- Watts, R.L. Conservatism in accounting part I: Explanations and implications. Account. Horiz. 2003, 17, 207–221. [Google Scholar]

- Watts, R.L. Conservatism in accounting part II: Evidence and research opportunities. Account. Horiz. 2003, 17, 287–301. [Google Scholar]

- Garc, J.M.; Osma, B.G.; Penalva, F. Accounting conservatism and firm investment efficiency. J. Account. Econ. 2016, 61, 221–238. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.; Watts, R.L. Estimation and empirical properties of a firm-year measure of accounting conservatism. J. Account. Econ. 2009, 48, 132–150. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum, P.R.; Rubin, D.B. The Central Role of the Propensity Score in Observational Studies for Causal Effects. Biometrika 1983, 70, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S.; Lai, S.-B.; Wen, C.-T. The Influence of Green Innovation Performance on Corporate Advantage in Taiwan. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 67, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Gong, L.; Wang, S. Large-Scale Assessment of Global Green Innovation Research Trends from 1981 to 2016: A Bibliometric Study. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 197, 827–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Chen, F.; Chen, Z. Does Green Innovation Increase Enterprise Value? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 1232–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Xu, X.; Li, Z.; Du, P.; Ye, J. Can Low-Carbon Technological Innovation Truly Improve Enterprise Performance? The Case of Chinese Manufacturing Companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 293, 125949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Jayaraman, V.; Paulraj, A.; Shang, K.-C. Proactive Environmental Strategies and Performance: Role of Green Supply Chain Processes and Green Product Design in the Chinese High-Tech Industry. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2016, 54, 2136–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Zeng, S.X.; Ma, H.Y.; Qi, G.Y.; Tam, V.W. Can Political Capital Drive Corporate Green Innovation? Lessons from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 64, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Wang, S.; Zhang, H. Could Environmental Regulation and R&D Tax Incentives Affect Green Product Innovation? J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzner, B.; Wagner, M. Linking Levels of Green Innovation with Profitability Under Environmental Uncertainty: An Empirical Study. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 378, 134438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.W.; Li, Y.H. Green Innovation and Performance: The View of Organizational Capability and Social Reciprocity. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 145, 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangelico, R.M. What drives green product development and how do different antecedents affect market performance? A survey of Italian companies with eco-labels. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 1144–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Q.; Liu, J.; Sheng, S.; Fang, H. Does eco-innovation lift firm value? The contingent role of institutions in emerging markets. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2019, 34, 1763–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovits, C.M. Corporate-sponsored foundations and earnings management. J. Account. Econ. 2006, 41, 335–362. [Google Scholar]

- Chih, H.L.; Shen, C.H.; Kang, F.C. Corporate social responsibility, investor protection, and earnings management: Some international evidence. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 79, 179–198. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.; Park, M.S.; Wier, B. Is Earnings Quality Associated with Corporate Social Responsibility? Account. Rev. 2012, 87, 761–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harjoto, M.A. Corporate Social Responsibility and Corporate Fraud. Soc. Responsib. J. 2017, 13, 762–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Huang, P.; Zhang, Y. Accounting conservatism and corporate social responsibility. Adv. Account. 2020, 51, 100501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Kang, J.K.; Low, B.S. Corporate social responsibility and stakeholder value maximization: Evidence from mergers. J. Financ. Econ. 2013, 110, 87–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R.G.; Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. The impact of corporate sustainability on organizational processes and performance. Manag. Sci. 2014, 60, 2835–2857. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, W.; Liu, M. Corporate social responsibility and the cost of corporate bonds. J. Account. Public Policy 2015, 34, 597–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, O.E. Markets and Hierarchies: Analysis and Anti-Trust Implications: A Study in the Economics of Internal Organization; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Harjoto, M.; Laksmana, I. The impact of corporate social responsibility on risk taking and firm value. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 353–373. [Google Scholar]

- Goss, A.; Roberts, G.S. The impact of corporate social responsibility on the cost of bank loans. J. Bank. Financ. 2011, 35, 1794–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsa, S.; Dai, N.; Belal, A.; Li, T.; Tang, G. Corporate social responsibility reporting in China: Political, social and corporate influences. Account. Bus. Res. 2021, 51, 36–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelb, D.S.; Strawser, J. Corporate social responsibility and financial disclosures: An alternative explanation for increased disclosure. J. Bus. Ethics 2001, 33, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ballou, B.; Chen, P.C.; Grenier, J.H.; Heitger, D.L. Corporate social responsibility assurance and reporting quality: Evidence from restatements. J. Account. Public Policy 2018, 37, 167–188. [Google Scholar]

- Dhaliwal, D.S.; Radhakrishnan, S.; Tsang, A.; Yang, Y.G. Nonfinancial disclosure and analyst forecast accuracy: International evidence on corporate social responsibility disclosure. Account. Rev. 2012, 87, 723–759. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, J.; Jo, H.; Na, H. Does corporate social responsibility affect information asymmetry? J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 148, 549–572. [Google Scholar]

- Ferdous, L.T.; Atawnah, N.; Yeboah, R.; Zhou, Y. Firm-level climate risk and accounting conservatism: International evidence. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 95, 103511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, K.; Henry, D. Accounting conservatism and voluntary corporate governance mechanisms by Australian firms. Account. Financ. 2012, 52, 631–662. [Google Scholar]

- Anton, W.R.Q.; Deltas, G.; Khanna, M. Incentives for environmental selfregulation and implications for environmental performance. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2004, 48, 632–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, I.; Migotto, M. Measuring Environmental Innovation Using Patent Data. OECD Environ. Work. Pap. 2015, 89, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneller, R.; Manderson, E. Environmental regulations and innovation activity in UK manufacturing industries. Resour. Energy Econ. 2012, 34, 211–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Song, S.; Jiao, J.; Yang, R. The impacts of government RD subsidies on green innovation: Evidence from Chinese energy-intensive firms. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 233, 819–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrone, P.; Fosfuri, A.; Gelabert, L.; Gomez-Mejia, L.R. Necessity as the mother of ‘green’ inventions: Institutional pressures and environmental innovations. Strateg. Manag. J. 2013, 34, 891–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givoly, D.; Hayn, C. The changing time-series properties of earnings, cash flows and accruals: Has financial reporting become more conservative? J. Account. Econ. 2000, 29, 287–320. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, J.R.; Wang, D. The Joint Effect of Investor Protection and Big 4 Audits on Earnings Quality Around the World. Contemp. Account. Res. 2008, 25, 157–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.; Novoselov, K.E.; Wang, R. Does accounting conservatism mitigate the shortcomings of CEO overconfidence? Account. Rev. 2017, 92, 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.H.; Kerstein, J.; Wang, C. The impact of climate risk on firm performance and financing choices: An international comparison. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2018, 49, 633–656. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger, P.; Sautner, Z.; Starks, L.T. The Importance of Climate Risks for Institutional Investors. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2020, 33, 1067–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Liu, B.; Chang, S.; Chan, K.C. Effects of air pollution on accounting conservatism. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2022, 84, 102380. [Google Scholar]

- Sautner, Z.; VAN Lent, L.; Vilkov, G.; Zhang, R. Firm-Level Climate Change Exposure. J. Financ. 2023, 78, 1449–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, J.; Xue, H. Accounting conservatism and relational contracting. J. Account. Econ. 2023, 76, 101571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginglinger, E.; Moreau, Q. Climate Risk and Capital Structure. Manag. Sci. 2023, 69, 7492–7516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R.G.; Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. Does It Pay to Go Green? The Environmental Innovation Effect on Corporate Financial Performance. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 300, 113695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Azevedo Rezende, L.; Bansi, A.C.; Alves, M.F.R.; Galina, S.V.R. Take Your Time: Examining When Green Innovation Affects Financial Performance in Multinationals. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 233, 993–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, Q.L.; Chen, P.C.; Lobo, G.J. Is Corporate Social Responsibility Performance Related to Conditional Accounting Conservatism? Account. Horiz. 2020, 34, 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).