1. Introduction

Over the past few decades, cities have undergone significant changes, such as rapid urbanization, socio-economic crises, and governance issues, etc., which pose severe challenges to the sustainability of city systems [

1]. Take the built-up environment of a city as an example. The car-oriented development model has led many cities to expand to a rather unreasonable size. However, at the same time, some core areas have witnessed problems such as population shrinkage and density decline [

2]. The social systems of cities are also confronted with problems such as unequal rights [

3], widening wealth gaps [

4], and reduced enthusiasm for political participation [

5], which have become even more severe after the COVID-19 pandemic [

6]. These are all results that government officials and other stakeholders do not want to see. Scholars and institutions from around the world are calling for more effective and resilient urban planning to promote the transformation of cities into sustainable ones [

7]. Also, nowadays, the public has higher requirements for a happy and prosperous living place [

8]. Against this backdrop, it is crucial to understand the dynamic evolution of cities. We distinguish between two main urban change models: urban development, which usually refers to a relatively orderly and controllable process aimed at improving urban functions, infrastructure, and quality of life through planning and policy guidance within the existing framework, and urban transformation, which is a more profound and sometimes even disruptive change, aiming to overcome social, environmental, and economic problems through thorough and systematic changes and ultimately moving towards sustainable and livable cities [

9]. These two modes are not separate but are often intertwined. Some goals and plans have been set to guide urban transformation, such as “sustainable urban development” (SUD) [

10]. Now, this can only be achieved in sufficient way with urban vitality. A city with full vibrancy is now believed to be able to attract investment and high-end talents, enhance the happiness of residents, and maintain the sustainability of the economic and social system [

11]. Studies from different disciplines, such as urban planning and human geography, have discovered that urban vitality can enhance residents’ interactions and happiness, as well as improve social capital community engagement [

12]. The importance of urban vitality has been widely shared. The World Bank Institute (WBI), the United Nations New Urban Agenda, and other institutions and planners worldwide have proposed to take urban vitality as an important part of their own urban development planning [

13,

14,

15]. As one of the largest emerging economies at present, in the process of urbanization transformation, China’s urban communities and villages have been demolished and rebuilt on a large scale. In the process of urban physical space reconstruction, problems such as social isolation, population loss, and social capital decline are constantly emerging [

16,

17]. China’s latest national urbanization plan emphasizes a people-centered orientation, sustainability, and urban vitality to meet the above challenges [

18].

Since Jane Jacobs creatively proposed the concept of urban vitality in the 1960s, the conceptualization, evaluation, and influence mechanisms of urban vitality have been a central focus of scholarly research. To understand and enhance the system-level phenomenon of urban vitality, it is necessary to deeply explore its driving mechanism. Urban vitality is not determined by a single factor but can be regarded as a dynamic socio-spatial system which is the result of complex interactions between the urban physical environment (the built environment subsystem) and human activities (the social subsystem). Jacobs advocates for understanding urban vitality in terms of the social interactions, activities, and livable streets of residents [

19]. Montgomery conceptualized urban vitality as the “liveliness of a place”, including the number of people on the streets at different times of day and the diversity of street life [

13]. Kevin Lynch, from the perspective of system resilience, regards vitality as the ability of urban systems to support the survival, development, and continuation of their internal elements [

20]. With the development of urban vitality theory, scholars have refined the concept based on their respective national contexts. Based on the practice of urbanization in developing countries, Jin compares urban vitality to the course of life, including three components: urban form, urban function, and urban society [

21]. Yue considered the specific characteristics of urban transformation and population flow and defined urban vitality as the ability of urban physical environment to promote urban social activities [

22]. Correspondingly, the measurement of urban vitality has developed along two distinct dimensions. The human activity-oriented conceptualization of urban vitality requires location-based datasets, such as transportation records [

23], mobile phone data [

24], and geotagged social media data (e.g., Twitter, Facebook) [

25,

26]. For urban form, urban vitality encompasses multifaceted aspects of urban systems, including political, economic, and cultural dimensions, typically employing entropy weight methods for comprehensive multi-indicator evaluation. For example, Demet’s assessment of Istanbul’s urban vitality includes the number of homes, the number of people, the proportion of commercial areas, and the price per square meter of land [

27]. Zeng uses a “DALD” framework to evaluate urban vitality, specifically including population density, road density, building density, mixed land use, the number of service facilities and so on [

28].

With the maturation of urban vitality theory, a growing number of scholars have explored the determinant factors of urban vitality as to provide scientific guidance for the construction of healthy, vibrant, and livable cities. Among them, the most classic model is the 3D model proposed by Cervero and his colleagues This model attempts to explain how the key elements of the built environment subsystem (Density, Diversity, Design) systematically affect resident behavior and spatial vitality [

29]. Subsequent research has expanded the 3D model by incorporating two additional dimensions, distance to transit and destination accessibility, resulting in a more comprehensive 5D model [

30]. The “nD” model has rich connotations and strong applicability and has been widely used to explore the influence mechanism of urban vitality. Sung took Seoul, South Korea, as a case study to explore the relationship between the degree of mixed land use, density, block size, building age, and urban vitality [

31]. Deng took a county in New York State to study the impact of housing years, distance from bus stops, and various public service facilities on urban vitality [

32]. Zhang’s study examined the impact of factors such as the number of intersections, block density, building density, building height, accessibility to public services, and the degree of mixed land use on urban vitality in 15 Chinese metropolises. His research has confirmed that street accessibility, architectural arrangement, and mixed land use are important factors affecting urban vitality [

33].

Among the many elements of the built environment, land use mix (LUM) is a basic urban planning concept and is closely related with urban vitality. When we talk about residents’ activities, it is inevitable to think of two basic and predominant land use strategies, that is, land use density and land use mix. There are numerous studies on the relationship between these two strategies and residents’ behaviors, including walking, traveling, and leisure [

34]. In response to the declining vitality during urban transformation, scholars and government officials have committed to promoting sustainable urbanization through high-density land use and land use mix [

34]. Land use density is straightforward to define and measure. The impact of high-density land use strategy, such as high land use intensity and building density, on urban vitality has been confirmed by scholars, and many useful conclusions have been provided [

35,

36]. However, only a limited number of studies have specifically examined how land use mix affects urban vitality. For instance, Dong’s research employed a coupling coordination model to preliminarily explore the relationship between land use mix and urban vitality, revealing that China’s major cities generally maintain coordination between these two factors [

37]. Ma’s study primarily focused on how park land use mix influences vitality [

38]. However, the specific influence mechanism of LUM on urban vitality remains a challenge in the study of complex systems. The difficulty in conceptualizing and measuring LUM is the main reason for the insufficient research on its relationship with urban vitality. Existing studies often simplify LUM to a single ‘diversity’ indicator when measuring it, which ignores the inherent complexity of LUM as a multi-dimensional concept. This simplification may lead to an insufficient understanding of the non-linear and spatially heterogeneous relationships between LUM and vitality. Also, this simplification has led to ambiguity as to the relationship between LUM and urban vitality, which may be positive, negative, or have no impact at all [

39,

40]. Therefore, it is necessary to systematically conceptualize and measure LUM, which will help us better understand urban vitality and introduce more insightful urban planning schemes. Nowadays, an important transformation in urban planning lies in fully encouraging the grassroots participation of people, which is regarded as closely related to building a resilient and vibrant socio-economic order [

6]. Existing studies have failed to fully capture the spatial proximity relationships of different functions and the compatibility or coordination of interactions, as well as how these configurations match the needs and perceptions of residents—the system’s agents and the main body of the system. In the post-pandemic era, LUM should be given more attention by planners because it not only helps to make the urban form more compact but also promotes community cohesion and interaction among residents [

41]. Paying more attention to the daily needs of residents is the most important aspect of improving the LUM concept, and it is also a direct requirement of the urban design concept after the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, it helps answer the question of how to enable residents to maintain their physical and mental health and carry out normal outdoor activities within a lockdown and control area [

42]. However, current studies about LUM and urban vitality have largely neglected these critical dimensions. To gain a more systematic understanding (systematically) of the impact of LUM on urban vitality, this study aims to address two key deficiencies in existing research. The first is to construct a more comprehensive LUM measurement framework. We not only consider the traditional diversity (quantitative relationship) and proximity (distance relationship) but also innovatively introduce the ‘Coordination Degree’ index based on public perception. These structural configurations affect the overall functional performance of the urban system by influencing people’s activity patterns, and urban vitality is the measure of this functional performance, especially the emergent properties of the system’s ability to attract and maintain human activities. Therefore, the systematic approach of this study aims to reveal how the system structure of LUM ultimately affects the system output (urban vitality) by influencing the system process (human activities), which is more in line with the requirements of the new, people-oriented urbanization for the coordinated development of the social–technological system. The second aim is to capture the temporal dynamics of urban vitality. Distinguishing between daytime and nighttime vitality helps reveal the operational status and response mechanisms of urban systems at different time scales [

43]. The urban system presents different activity patterns and functional requirements during the day and night, and the influence of LUM may also change accordingly.

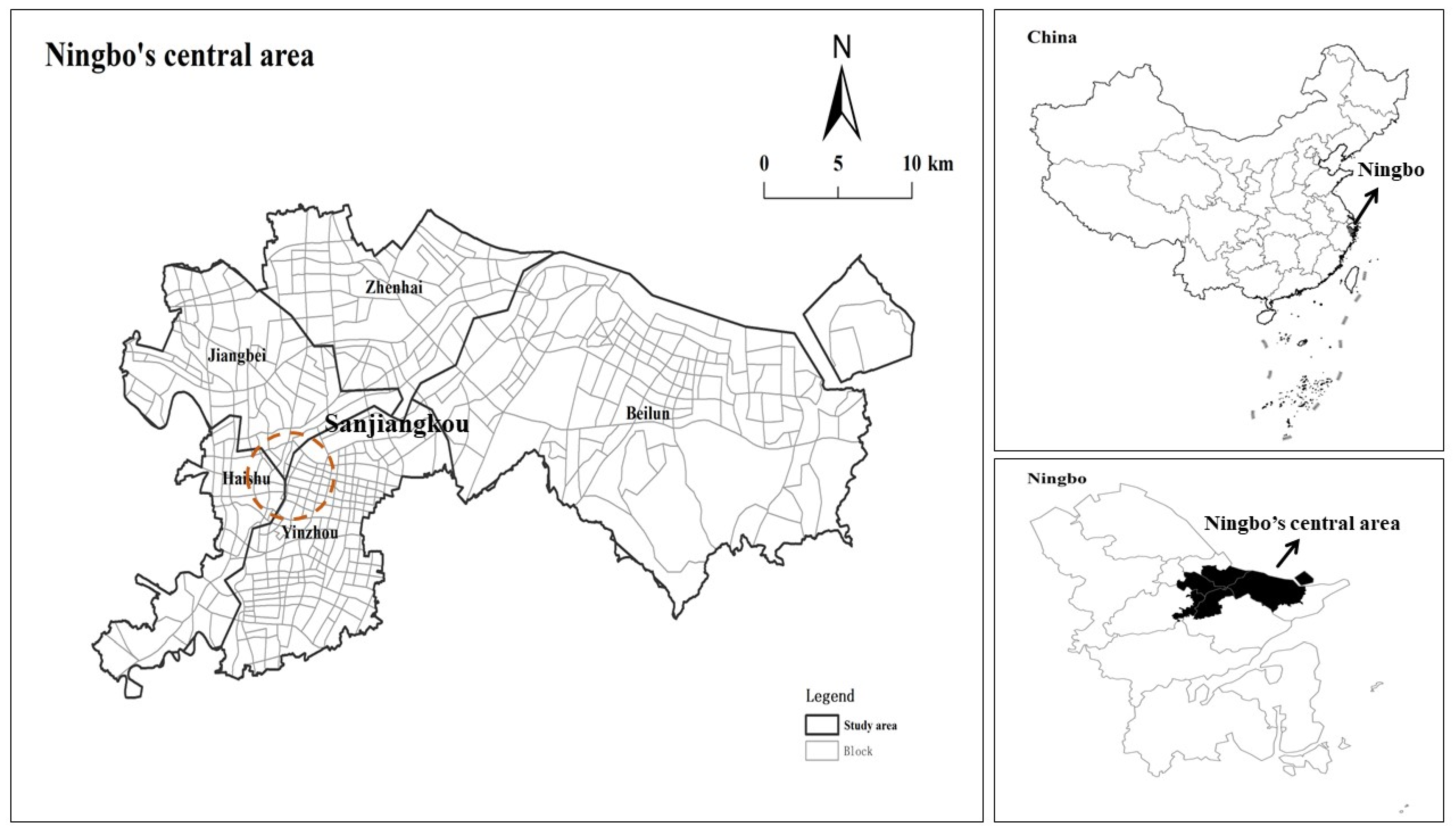

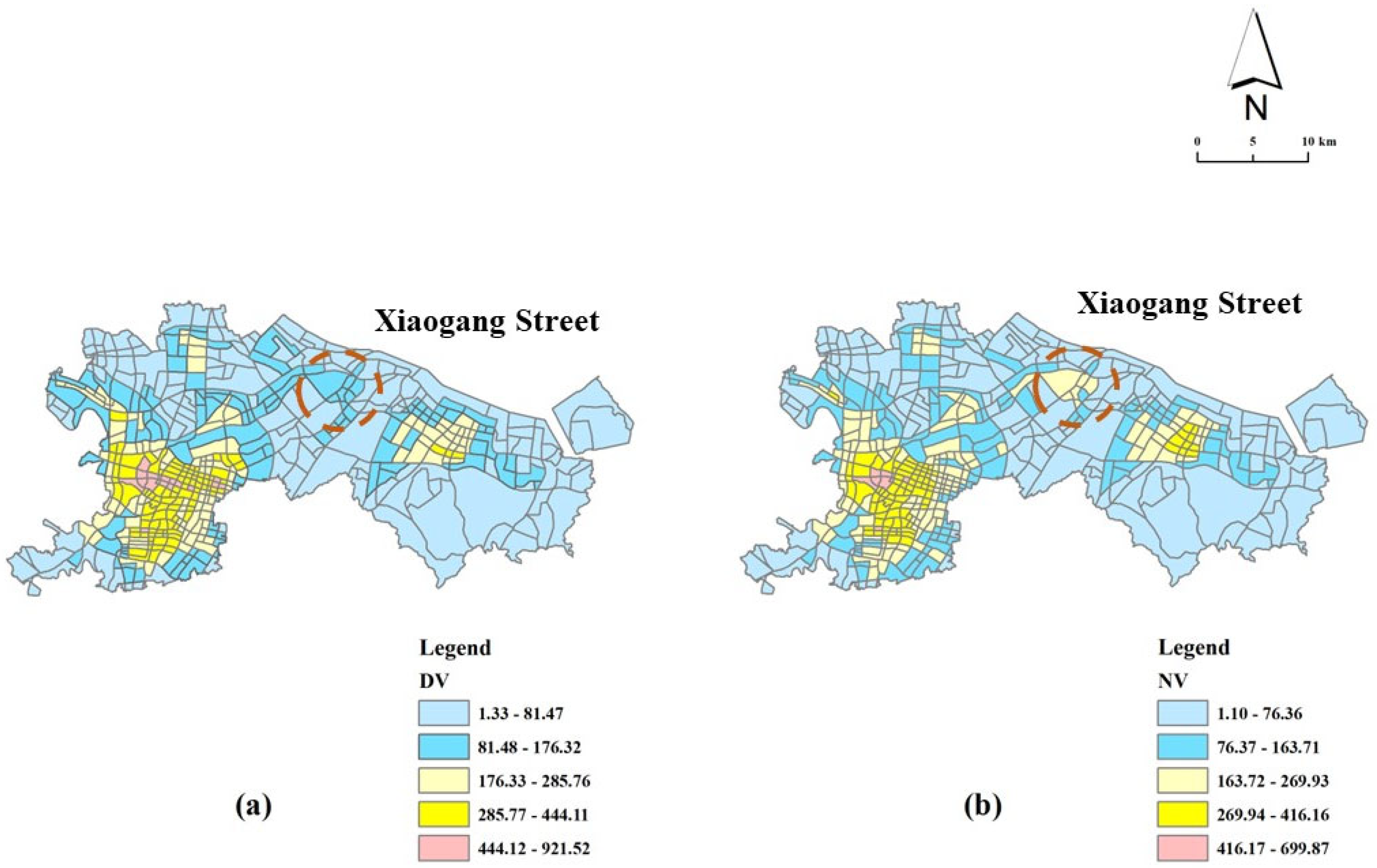

Based on this, this study selects the central urban area of Ningbo, China, as a case study. The rich land use practices in this area provide an ideal scenario for testing the effect of LUM in complex urban systems. We will integrate multi-source geospatial data to construct a multi-dimensional LUM index system that includes diversity, proximity, and coordination and measure urban vitality during the day and at night. By using the geographically weighted regression (GWR) model, we will deeply explore the internal mechanism of the multi-dimensional LUM’s influence on the spatially heterogeneous effects of urban vitality. This study aims to provide a more integrated and dynamic systems perspective to understand the relationship between LUM and urban vitality. Its findings can not only be beneficial to Ningbo City; they can also provide systematic and nuanced strategies for optimizing and revitalizing land use to other cities facing similar challenges, thereby promoting the sustainability and resilience of the urban social–spatial system.

4. Discussion

Urban vitality and land use mix are both important and traditional urban research topics. Among them, urban vitality is the goal of high-quality urbanization all over the world, and the mixed use of land is one of the basic principles of contemporary urban planning. Since the publication of Jacobs’ book The Death and Life of Great American Cities in the 1960s, scholars have called for land use mix strategies to improve vitality. However, whether and how land use mix can improve urban vitality is still a theoretical proposition to be tested. To this end, this study combines multiple sources of data to conduct a preliminary test of the theoretical proposition and finds many valuable research results.

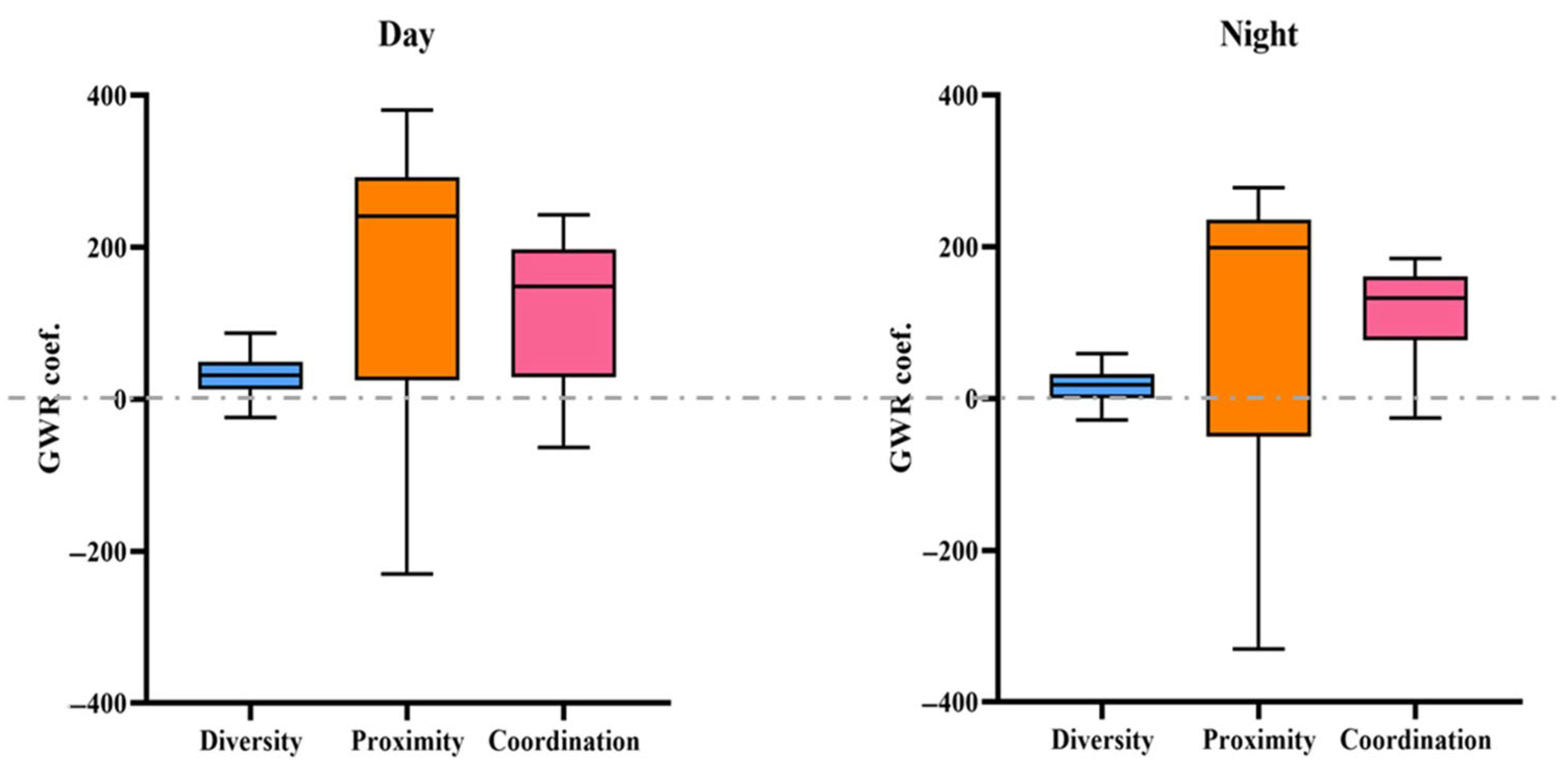

Our research shows that the key point of land use mix is not “mixed” or “diverse” but that it focuses on the interrelationship between the land mix system. This is basically consistent with the connotations of the evolution of the idea of land use mix, from focusing on the quantitative relationship of land use to the distance and attribute relationships of land use systems [

55]. In fact, focusing on land use diversity alone may not stimulate urban vitality. As scholars have said, mixed land use projects usually include residential, commercial, industrial, recreational, and agricultural land, but not all land use types are common destinations for residents’ activities [

77]. Our research emphasizes constructing walk-friendly and attractive land use mix (LUM) spaces from the perspective of residents’ daily lives, thereby activating 24 h urban vitality. This study’s expansion on previous studies is mainly reflected in two aspects: (1) it places greater emphasis on residents’ life experiences; (2) it highlights the round-the-clock nature of urban vitality. Regarding the first point, past urban studies have predominantly focused on the physical layout of urban infrastructure, which is inherently linked to China’s institutional context. China’s unique land finance system and GDP-driven system have strongly influenced local government behavior, prompting them to prioritize large-scale infrastructure projects for high economic growth, thus overlooking residents’ interests. For instance, the 4 trillion plan in the 21st century encouraged local governments to heavily invest in transportation, urban infrastructure, and real estate [

78]. Although China’s current emphasis on new-type urbanization highlights citizen participation in national strategies, urban residents still primarily engage in urban life as passive “subjects of management” [

79]. By integrating “coordination” into the LUM framework, our study has demonstrated its positive impact on enhancing urban vitality, illustrating that considering residents’ subjective preferences is crucial for constructing dynamic and livable cities. Regarding the second point, we reaffirm the significance of time for daily life. Existing studies predominantly focus on the static vitality of cities, overlooking the temporal attributes of vitality. Time is crucial for daily life as it constitutes an integral part of social institutions. For example, work commuting hours—a social and institutional arrangement—largely determine people’s life rhythms [

80]. Past research has largely ignored this aspect; hence, there has been minimal exploration of nighttime vitality. In fact, cities worldwide, such as the “24 Hour London” concept introduced by Sadiq Aman Khan in 2016 and Shanghai’s nighttime economy, are now advocating for the importance of nighttime periods. From the perspective of enhancing nighttime vitality, this study has demonstrated the need to pay special attention to coordination in land use mix (LUM). The primary reason for this phenomenon lies in the particularity of time under social institutional arrangements: daytime vitality relies on the “passive aggregation” of commuter flows, while nighttime vitality depends on residents’ “active choices”, requiring mutual coordination among residential, recreational, and leisure functions. This research conclusion aligns with Pan’s case survey, showing that nighttime vitality does not depend on the number of facilities but on whether these facilities can meet residents’ needs. One example is the formation of attractive spaces by combining shops, parks, residential buildings, and entertainment streets, etc. [

81].

Secondly, it is necessary to avoid one-size-fits-all spatial planning policies, and LUM implementation plans must be formulated in combination with the status of each region. By comparing the proximity with high-vitality areas, we find that there is a certain degree of mismatching between them. The area with high proximity is mainly located in Yongjiang Science and Innovation Park (the street-like area above the Sanjiangkou); correspondingly, the block vitality of this area is basically at a medium or low–medium level. Yongjiang Science and Innovation Park is a comprehensive innovation park started in Ningbo City in 2022. Its main function is scientific and technological innovation and the integration of production and research. Since the park is in the early stage of construction and lacks infrastructure, the continuous introduction of medical, educational, and transportation facilities can form scale effects and better meet the needs of local enterprises and staff. Correspondingly, mixed diversity plays a significant role in promoting the vitality of blocks in this area. This means that in the early stage of development, the intensity of regional infrastructure construction is more important to enhance the attractiveness of the place. Correspondingly, it can be observed that LUM coordination has the most significant effect on enhancing the vitality of old urban areas, as coordination particularly emphasizes the balance of organizational structures within the LUM system. This mirrors China’s urbanization path at the regional level: an initial pursuit of quantitative growth followed by a later focus on readjusting internal structures [

18].

Our research findings also resonate strongly with important contemporary urban planning principles. First, the research findings seem to indicate that, compared with the monocentric urban organizational form, polycentricity is more conducive to urban vitality. Urban expansion, accompanied by the negative externalities of agglomeration, has brought unprecedented pressures and challenges to cities. Reshaping urban spatial structures to improve urban quality of life is regarded as a beneficial attempt, in which the polycentric city, as a planning concept, has gained attention. It is considered to possess positive agglomeration externalities and is also socially, economically, and environmentally friendly [

82]. Overall, the urban spatial structure of Ningbo still bears the distinct characteristics of a monocentric model, and the Sanjiangkou area maintains an absolute competitive edge over other parts of the city. However, it is undeniable that the city’s sub-centers have started to take shape and function; examples include Beilun New Town, in our study, and Xiaogang Street, reported in other research papers (a satellite town, though it has not been officially recognized by municipal authorities). It should be noted that sub-centers are essentially different from urban centers under traditional functional zoning (such as employment centers, residential centers, etc.), as sub-centers must implement LUM schemes. Escamilla has particularly emphasized the importance of LUM for an urban center to attract crowds, encourage human mobility, and retain it [

83]. Our research has preliminarily confirmed this: while some urban sub-centers (such as Beilun and Xiaogang Street) lack optimal LUM diversity, proximity, and coordination, they have begun to significantly influence the vitality of these areas. Thus, for urban vitality, a polycentric spatial organization may be preferable, as it provides the conditions for the positive externalities of the urban built environment, such as LUM, to come into play.

This study also resonates with another contemporary urban planning concept, namely the 15 min city. Compared to the polycentric model, 15 min city planning addresses a smaller scale, which is closely associated with blocks and neighborhoods and thus has a closer connection with people. The concept of the 15 min city was proposed by Carlos Moreno, who presented an ideal for urban planning: constructing more human-centered urban structures through rational spatial planning while maintaining urban resilience, vitality, and sustainability. He particularly emphasized a planning principle based on proximity, meaning that people should be able to access public services, leisure, entertainment, and various daily necessities within a 15 min walk or bicycle ride [

58]. This design idea shares a high degree of consistency with LUM at the block level and is both rooted in humanism and oriented toward residents’ daily needs. This study finds that the LUM model, which emphasizes resident preferences, land use system balance, and proximity, significantly enhances urban vitality—a finding that demonstrates deep resonance with the 15 min city concept. The 15 min city advocates for proximal layouts of residential, commercial, and public services at micro-scales like blocks and neighborhoods to meet residents’ daily needs. Its planning logic, centered on walkability, essentially optimizes residents’ daily activity networks, reduces commuting costs, and thereby enhances block vitality, which is highly consistent with the objectives of LUM. Furthermore, the 15 min city’s close connection to residents verifies this study’s finding that “meeting resident preferences is key to enhancing vitality”—by creating convenient and human-centered living scenarios, it stimulates residents’ enthusiasm for participating in various activities. Moreover, this planning concept can be deeply integrated with the polycentric model. Future urban planning could adopt a nested system of “macro-structure (polycentric city)–meso-network (15 min city)–micro-unit (block)” to achieve a systematic enhancement of overall urban vitality [

84].

The three-dimensional evaluation system of LUM proposed in this study, especially the “coordination” indicator, provides a quantitative tool for the “people-oriented” planning concept and may provide the following useful references for urban managers: Firstly, in terms of cultivating urban vitality, urban managers should pay attention to the use of mixed land use strategies and the design of reasonable urban forms, including the size of residential areas, the layout of roads, and the collocation of green spaces. Secondly, in terms of changes in the land management concept, although land use mix is considered by many planners to be an important strategy to improve vitality, mixed land use is not simply the diversification of land use. Urban designers should pay more attention to the accessibility of various facilities and their importance to residents’ lives. Finally, it is important to design land use mix schemes according to local conditions. For new areas that are yet to be developed, it is still an effective strategy to increase investment in facilities, including the construction of industrial and residential spaces, public services, land, and commercial facilities, so as to provide a more solid environment foundation for region’s vitality. For old towns with complete facilities, more attention should be paid to the coordination between facilities. Walking behavior can be promoted through a well-designed network of blocks. At the same time, old facilities can be replaced according to public preference, so as to improve the utilization rate of facilities in the block and finally improve the vitality of the city [

85]. The influence of LUM degree on urban vitality discovered in this study can provide strategies for guiding urban development and adapting to urban transformation. Therefore, in future urban development planning, in cities in developing countries with rapid urbanization, the planning of new districts can draw on the conclusions of this study and focus on the construction of the diversity and proximity foundation of LUM. In cities in developed countries that are facing contraction or transformation, specific areas can be activated by optimizing the LUM ‘coordination’ of the existing built environment.

However, due to the limitations of the study data and the ability of the researchers, there is a lot of room for improvement. First of all, under the permission of data conditions, the full-cycle dynamic data, including urban vitality, POIs, roads and buildings, should be collected to achieve a dynamic monitoring and management of urban vitality. Second, this study is based on Ningbo, a newly designated first-tier city in China with a population exceeding 9 million and an extensive infrastructure, yet many cities in China—particularly those in Central and Western regions—remain underdeveloped, and urban vitality may exhibit distinct responses to LUM. A notable example is the heterogeneity in the LUM–urban vitality relationship observed in Ningbo’s Sanjiangkou (a well-developed area with complete facilities) and Yongjiang Science and Innovation Park (a newly emerging underdeveloped zone), implying that this nexus varies across cities—though multi-case comparisons were not incorporated in this study. It is particularly noteworthy that future research could classify cities by integrating urban resource endowments and human living habits (e.g., preferences for comfortable climates). For instance, in tourism-dependent cities, population dynamics are substantially governed by seasonal patterns: many residents of Southern China migrate to northern regions in summer to escape the heat, while northern cities like Harbin and those in Liaoning Province, enabled by their cold climates, develop ice–snow industries [

86]. The summer influx of southern visitors triggers pronounced seasonal fluctuations in urban vitality, which, moreover, highlights the importance of LUM types. Future studies with robust data support could explore how specific LUM types (e.g., ice–snow land uses) influence urban vitality. Such analyses would undoubtedly foster a more comprehensive understanding of urban vitality and inform tailored LUM strategies, yet data constraints and research scope precluded this inquiry in the present study. Third, although this study attempts to introduce public awareness of land use mix to build a bridge between urban land and residents, it is only a preliminary attempt. Future research should consider establishing a comprehensive indicator system for human–land coordination in terms of multiple dimensions, including urban characteristics, individual resident traits, and even economic, social, and political institutions to deepen the understanding between LUM and urban vitality. Forth, our study preliminarily found that the vitality of different urban areas, such as new and old urban areas, cemetery areas, and science and innovation areas, has different responses to the mixed use of land. Future studies can further diagnose the deep mechanisms affecting urban vitality by taking the idea of zoning research and combining it with field research.