1. Introduction

Since the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC), we have upheld the central role of innovation in China’s overall modernization drive, emphasized that innovation is the primary driving force, fully implemented an innovation-driven development strategy, and strived to build a world-class scientific and technological power. In 2024, the “Implementation Opinions on Promoting the Innovation and Development of Future Industries”, jointly issued by seven departments, including the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, proposed that major national science and technology projects and major science and technology research projects should be implemented, and 100 cutting-edge key core technologies should achieve breakthroughs to form 100 iconic products. On the one hand, innovation policies can inject new momentum into economic growth. Innovation can promote the transformation of traditional industries toward high-end, intelligent, and green development, improving the production and operational efficiency of enterprises. Moreover, it can promote the optimization and upgrading of the industrial structure. On the other hand, innovation is key to enhancing international competitiveness. We need to address key and core technologies and promote integrated innovation among midstream, downstream, and large-, small-, and medium-sized enterprises along the industrial chain. To support the innovation strategy, ensure the safety and integrity of the industrial chain, and enhance its resilience and risk resistance capacity, China has pledged to cultivate specialized and special new enterprises.

Specialized and special new enterprises refer to those with specialization, refinement, and novelty. Most of them focus on a specific segment of the industrial chain, with a clear business focus, relatively strong innovation ability, innovation vitality, and risk resilience. Specialized and special new “little giant” enterprises are selected leaders of small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) [

1], representing a higher-level category of specialized and special new enterprises. In 2023, the total revenue of state-level “little giant” listed enterprises reached CNY 1.26 trillion, accounting for approximately 1% of China’s GDP. “Little giant” enterprises have far-reaching significance in promoting China’s economic development and scientific and technological innovation. They are characterized by high innovation and R&D costs, long investment recovery cycles, and high risks of investment returns. They also face financing difficulties and need very patient capital investment. “Little giant” enterprises usually take human capital as their core asset, and many of their intangible assets cannot be easily measured. External financiers are often reluctant to provide financing to them because of the agency costs caused by information asymmetry and moral hazard. Relying only on the market for resource allocation will lead to a large credit rationing problem, making it difficult to support the innovation of “little giant” enterprises [

2,

3,

4].

Government venture capital is a policy instrument used by the government to guide private capital investment in innovation and entrepreneurship, high and new technology, and other fields. It is a policy fund provided by the government and established with the participation of local governments, financial institutions, and private capital. Government venture capital uses fewer funds to leverage the influx of social capital, plays a financial leverage role, jointly helps the development of science and technology innovation SMEs with venture capital, and plays a powerful role in improving the supply of venture capital and overcoming market failures [

5]. The exertion of this leverage effect enhances the attractiveness of the project by transmitting signals to the market. In addition, setting up a risk compensation mechanism can help reduce investor risk. For “little giant” enterprises, in addition to the credit endorsement of their own “Little Giant” recognition, the financing constraints they face also require government support to be addressed. Government venture capital can effectively encourage market investors to flow into these fields and promote the upgrading of the whole industry. Meanwhile, government venture capital, as a form of “patient capital”, supports long-term innovation. Compared to venture capital, which has a longer duration and weaker assessment of profitability, it is more suitable for the innovative development of “little giant” enterprises. However, government venture capital still faces a contradiction between government goals and market-oriented operations. Excessive government intervention in investment decisions and the setting of counter-investment ratios have led to their inability to effectively support the development of specialized, refined, distinctive, and innovative “little giants.” Therefore, their specific impacts still need further verification.

On the basis of the functions and objectives of government venture capital, this study focused on their investment behavior and effect, and multiple linear regression was used to conduct empirical research. First, this paper explores the investment effect of government venture capital and verifies whether its intervention can effectively improve the innovation of “little giant” enterprises. It also studies its mechanism of action, whether it influences the output of innovation results through the intermediary effect of R&D input, and discusses its regional heterogeneity and industry heterogeneity, as well as its synergistic effect with traditional policy measures such as government subsidies. Finally, this study proposes corresponding policy recommendations to improve the policy system to support the innovation and development of “little giants”. This article helps to clarify the mechanism through which government venture capital promotes the development of “little giant” enterprises and identifies the specific conditions for the exertion of its effect, such as industries and regions. It also provides valuable suggestions for state support of small- and medium-sized enterprises, which have both theoretical and practical significance.

2. Literature Review

Many scholars have confirmed the driving effect and policy guidance effect of government venture capital on the innovation of new technology enterprises. When assessing its policy guidance effect, the ability to attract finance is often used as a key metric. For instance, Mazhar Islam et al. [

6] found that clean energy start-ups receiving GVC are significantly more likely to secure subsequent venture capital (VC) funding compared to those without such subsidies. Massimiliano Guerini and Anita Quas [

7] demonstrated that GVC increases the possibility of obtaining private venture capital. Some scholars have conducted further research about the specific manifestations of this policy guidance effect. Minli Yang et al. [

8], based on provincial-level venture capital data from 2000 to 2011, reported that in provinces with less-developed VC markets, GVC plays a guiding role in attracting social capital. Xiaomin Ni [

9], focusing on the mechanisms of policy effects, found that subsidies provided by government venture capital substantially enhance investment returns and mitigate the risks for social capital investing in start-ups, thereby promoting follow-on financing.

Research on the impact of government venture capital on enterprises includes both financing improvements and the allocation of internal resources [

10]. This is reflected in the subsequent governance of the enterprises receiving such funding. Yuchen Li [

11] argued that GVC can attract more private and other public funds, consequently promoting green innovation within firms. Bertoni’s [

12] research on joint venture investments revealed that while the innovation performance of firms receiving only GVC support does not show significant improvement, firms receiving both GVC and private VC exhibit superior innovation performance compared to firms receiving no investment. This highlights the conditional nature of GVC’s effectiveness. Yael Alperovitch et al. [

13] explored factors influencing the achievement of innovation objectives by European GVC-backed firms, finding significant impacts from location selection, co-working arrangements, and joint investment. Research on specialized and special new “little giant” enterprises—a concept originating from Germany’s “Hidden Champions” and serving a crucial strategic role in “strengthening and supplementing industrial chains”—includes findings that the “Little Giant” certification itself stimulates enterprise innovation [

14]. This certification promotes innovative performance by alleviating financing constraints [

15]. Furthermore, scholars have combined government venture capital with “little giant” enterprises. Zihan Yang [

16], employing a difference-in-differences regression model, indicated that participation by GVC stimulates innovation within “little giant” enterprises.

However, some scholars hold different views about the policy guidance and innovation-driving effects of government venture capital. Cumming and MacIntosh [

17] believe that government venture capital is often motivated by non-market-oriented objectives, leading to deviations from the optimal allocation of market resources. Such distorted investment behavior exerts a “crowding-out effect” on social capital. Yuejia Zhang [

18] found that start-ups receiving backing from hybrid syndicates (including government-backed entities) in their initial financing rounds are significantly less likely to secure follow-up financing in subsequent rounds compared to those funded solely by private VC syndicates. Discussions also address practical reasons for the emergence of such inhibiting effects. Yuchen Li [

19] pointed out that government funds suffer from regional development imbalances, excessive government-led investment, and a failure to adhere to market-oriented operational principles. Additionally, government venture capital can restrict the role of strategic limited partners (LPs) on investment committees, thereby intervening in decision-making.

Compared to other investment funds, there is still some controversy in the existing research and discussion on whether government venture capital plays a positive role in guiding and promoting the innovation of new technology enterprises, and the actual effect of government venture capital on the innovation of new technology enterprises needs further investigation. Moreover, there are few studies on the investment strategy of government venture capital, and research on investment behavior and the investment effect has not been organically combined. The existing research literature from the perspective of specialized and special new “little giant” innovation ecology is also relatively insufficient, as is the research mechanism. Therefore, in this study, specialized and special new “little giant” enterprises were taken as samples, focusing on their investment behavior and effects, and an empirical study on the impact of government venture capital on the innovation of specialized and special new “little giant” enterprises was conducted to supplement the empirical evidence in this field.

3. Theoretical Basis and Hypothesis

For “little giant” enterprises, their relatively small scale, the inherent characteristics of their scientific and technological innovation activities, and the lack of traditional mortgages contribute to a serious problem of information asymmetry between these enterprises and market investors. This leads to corresponding market failures, resulting in enterprises falling into financing difficulties and limiting their further sustainable development [

20]. Due to information asymmetry, enterprises cannot obtain sufficient external financing sources to support their professional and refined development path, and their production and operation are constrained by cash flow, which may lead to a return to traditional inefficient diversified operations or the crisis of bankruptcy. At the same time, the state has positioned “little giant” enterprises as the policy focus of supply-side structural reform, an important stabilizer of the new development pattern, and a new force to build an innovative country, which is necessary for macro-control. At present, “little giant” enterprises are generally highly concentrated in the main business, which is a double-edged sword that can not only concentrate the advantages of resource endowment but also fully realize the exchange of innovation resources, which greatly improves the possibility of breakthrough innovation. However, it can also increase the risk of failure, and early innovation investment may be wasted. In addition, in the principal–agent corporate structure, the information asymmetry between executives and shareholders affects the innovation activities of enterprises. The absence of a reasonable corporate governance mechanism is likely to lead to principal–agent problems, causing executives to ignore the long-term interests of enterprises and focus on the modification of financial indicators.

The theory of government intervention directly aims at the market failure caused by information asymmetry. It proposes exerting influence on resource allocation through government venture capital and other government intervention methods to encourage the sustainable development of “little giant” enterprises. According to signal transmission theory, government venture capital is a policy fund, which is funded by the government and endorsed by credit, and the development potential of the enterprise is screened by professional fund management institutions, which invest in specialized and special new “little giant” enterprises in the form of equity participation in sub-funds or follow-up investment. Based on the resource-based view, agency theory, and the institution-based view, by shedding light on how the different characteristics of government venture capital affect alternative energy production innovation, policymakers need to strike a balance between government intervention and market mechanisms [

21]. Investment behavior serves as evidence that “little giant” enterprises have room for value-added profitability, moving beyond policy documents to leverage social capital. Government venture capital helps enterprises obtain credit financing, benefit from implicit credit endorsement, and receive policy guidance. It also plays a role in signal transmission, alleviates information asymmetry, and guides social capital investment to support “financing hematopoiesis,” thereby alleviating the practical dilemmas of financing difficulties and high costs faced by specialized and new “little giant” enterprises. Government venture capital can also play a positive role in helping investee companies improve their social identity and transform their reputation into a reduction in transaction costs and expansion of the sales market, which is conducive to alleviating the internal financing problem.

In addition, by relying on national policy guidance, government venture capital attracts technology, human resources, and other factors to invest in enterprises, thus promoting their spatial aggregation. In a highly uncertain market environment, the positive guiding effect of government venture capital on entrepreneurs’ mentality and behavior can help entrepreneurs cope with various uncertainties and reduce their cognitive pressure to some extent. Government venture capital can help enterprises establish good relationships with the government. A good government–enterprise relationship makes it convenient for enterprises to obtain the policy support they need to help them better realize cross-industry and cross-regional development of entrepreneurial projects and make diversified investments. Government venture capital can guide social capital to form a capital pool with high resilience to risk and rich factor endowment, and the nonfinancial resources formed have a certain positive pulling effect on financial support and transaction flow opportunities. The advantages of heterogeneous resources are that they can help enterprises carry out innovative reforms on productivity factors such as the labor force and labor objects, and they can improve the innovation of enterprises.

Therefore, this paper proposes Hypothesis 1.

H1. Government venture capital intervention can improve the innovation of “little giant” enterprises.

Compared to market-oriented venture capital funds, government venture capital is characterized by higher risk tolerance and weaker profit-target orientation. With lower short-term capital recovery requirements, it can tolerate enterprises conducting high-risk R&D projects. This fosters a corporate culture of innovation and experimentation, eases managers’ short-term performance pressure, and encourages long-term R&D investment.

Moreover, government venture capital assists “little giant” enterprises in establishing a scientific and comprehensive management model. This enables enterprises to allocate resources more efficiently and pay closer attention to the proportion of R&D expenditure during budget formulation and implementation. Aligned with the government’s macro-policy vision, the central financial fund supports “little giant” enterprises in increasing R&D investment centered on the “three innovations” (generating new drivers, tackling new technologies, and developing new products). Government venture capital, in turn, prompts enterprises to strengthen investment in these areas, ensuring policy implementation at the enterprise level.

Statistics show that the R&D intensity of “little giant” listed companies is 1.66 times that of the market average. Their innovation is manifested in product or service innovation, as well as in new technologies, processes, concepts, and models. “Little giant” enterprises either invest in preliminary basic research, focusing on cutting-edge theories to achieve scientific and technological breakthroughs and become “individual champions”, or pursue the transformation of scientific and technological achievements. They collaborate with universities, research institutions, and upstream and downstream enterprises in the industrial chain for joint R&D, jointly resolving bottlenecks in the industrial chain, and capitalizing on the rapid-iteration advantage of SMEs in new business forms.

By increasing R&D investment and allocating R&D expenditure to factors of production like labor, labor objects, and labor tools, these enterprises enhance their innovations through independent or joint innovation. This promotes the breakthrough of key bottlenecks in the industrial chain, achieving a healthy cycle and a strengthened chain.

Based on this, this paper proposes Hypothesis 2.

H2. Government venture capital will enhance the innovation of specialized and special new “little giant” enterprises by increasing R&D expenditure.

6. Research Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

6.1. Research Conclusions

Empirical research was conducted using sample data from the first through sixth batches of specialized and special new “little giant” enterprises listed on A-share and NEEQ from 2013 to 2023, and the following conclusions were drawn.

Government venture capital tends to be invested in “little giants” specializing in strategic emerging industries. In allocating government venture capital, the government considers both policy orientation and investment efficiency in its investment decision-making, which is in line with the strategic goal of national industrial structure adjustment, transformation, and upgrading.

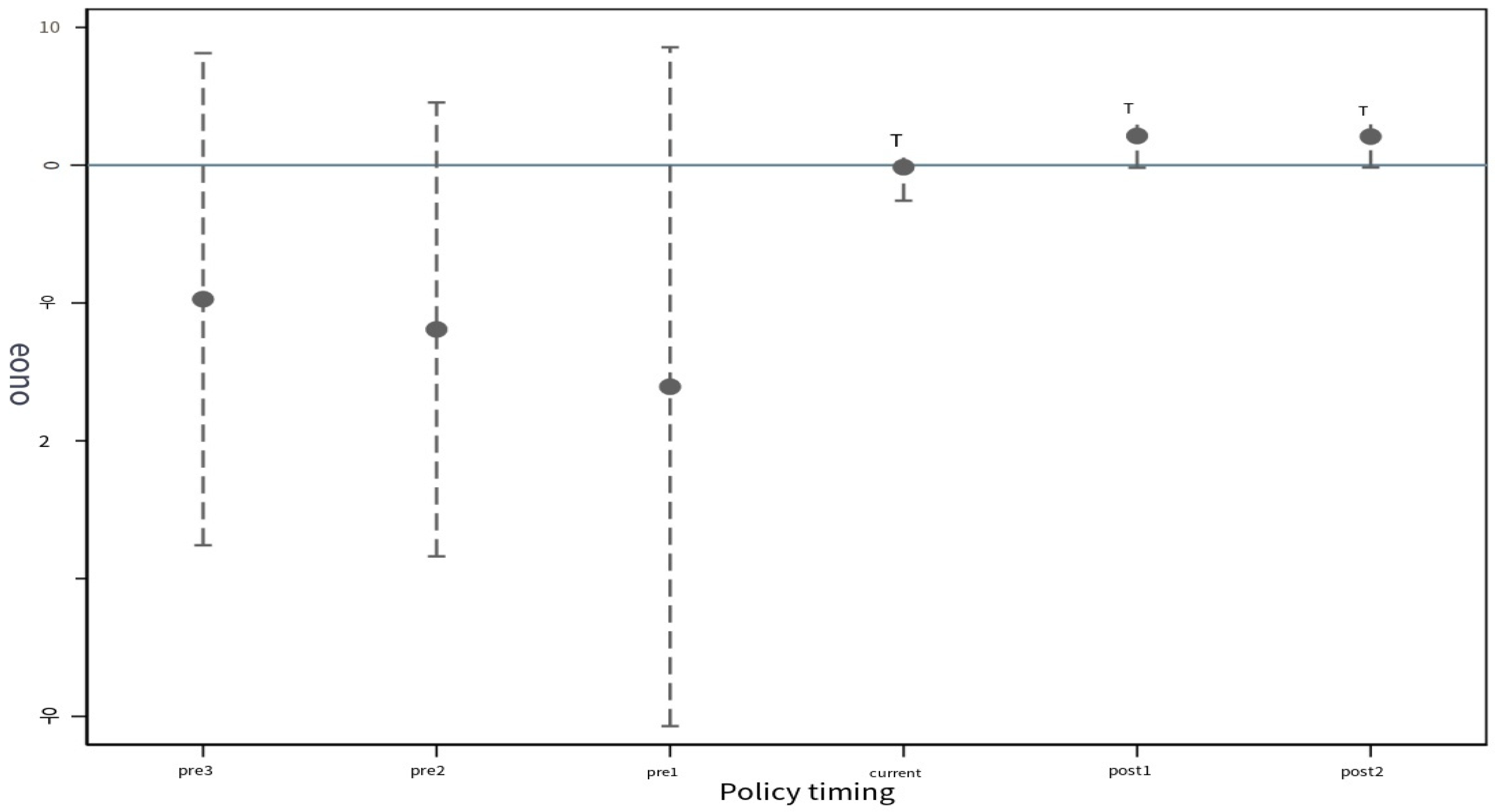

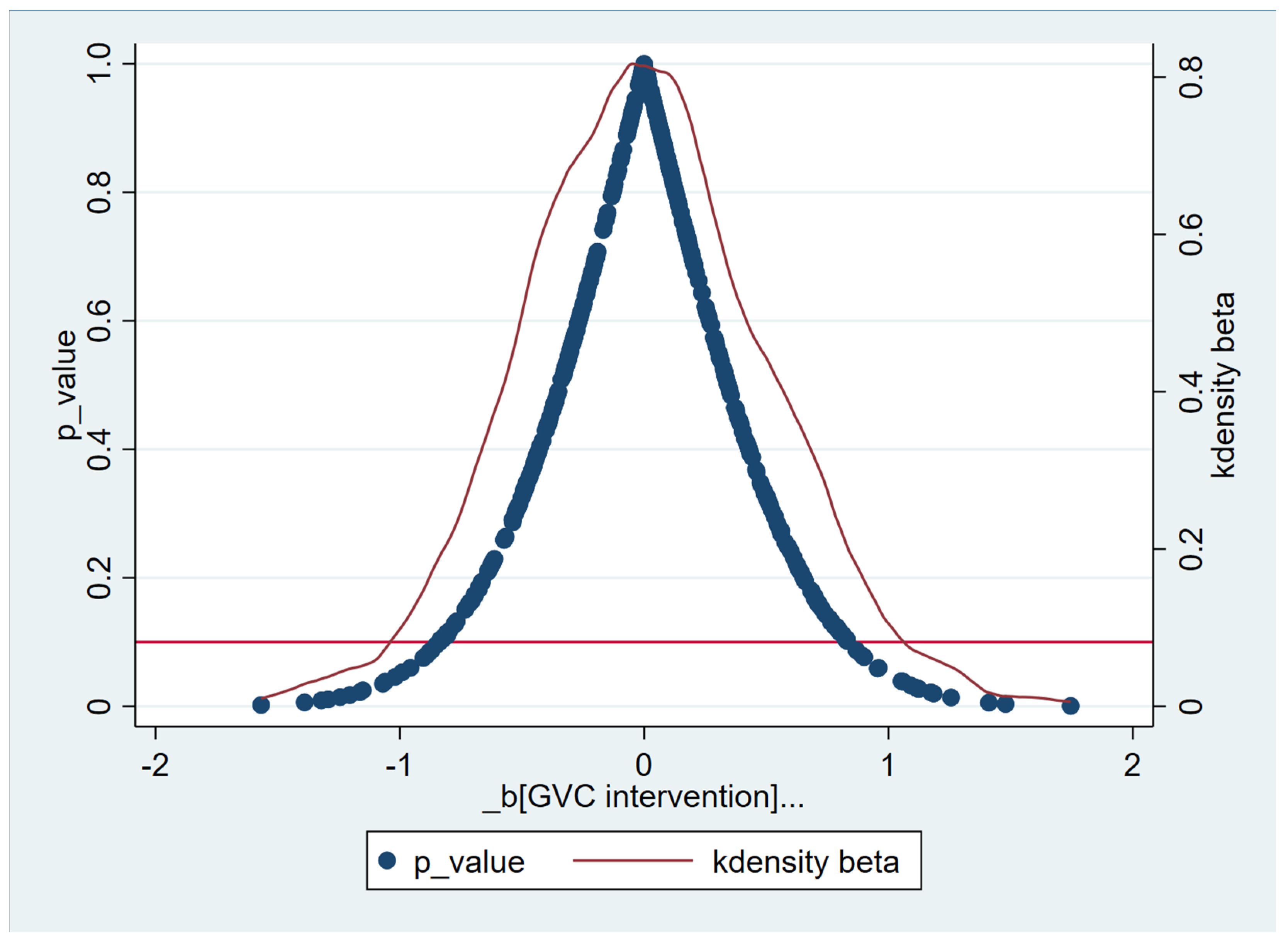

Government venture capital intervention can improve the innovation of “little giant” enterprises. It has a significant role in promoting enterprise innovation. Government venture capital can effectively alleviate the financing constraints of enterprises by means of signal transmission, resource aggregation, and policy support, and it can improve the ability and willingness of enterprises to improve their innovation. This is achieved through the mediating mechanism of R&D investment. Government venture capital intervention helps the invested “little giant” enterprises form a culture of innovation and trial and error, encouraging them to invest more resources in research and development activities and pay more attention to long-term input and output to achieve innovative breakthroughs.

The promotion effect of government venture capital on “little giant” enterprises is greatest in the central region, followed by the eastern region, and it is not significant in the western region. From the perspective of industry heterogeneity, this promotion effect is more notable in strategic emerging industries because enterprises in this industry face more serious information asymmetry problems, and government venture capital has a more significant mitigating effect on this effect. There is a synergistic effect between government venture capital and government subsidies. The combination of the two can play a positive role in the joint regulation of policies and can jointly promote the innovation and development of “little giant” enterprises.

6.2. Policy Suggestions

6.2.1. Strengthen Support for Strategic Emerging Industries

Continuously enhance support through government venture capital for strategic emerging industries. Strategic emerging industries are a vital cornerstone of China’s innovation drive, playing a crucial role in breaking through domestic circulation bottlenecks, ensuring the security of China’s industrial chain, and promoting industrial structure upgrading. Given the serious information asymmetry they face, further policy inclination is necessary.

Clearly define the investment direction of industrial investment funds. Focus on improving the modern industrial system, support the transformation and upgrading of traditional industries, cultivate and expand emerging industries, plan and construct future industries, concentrate on investing in key links of the industrial chain and projects for chain extension, supplementation, and strengthening, and boost the resilience and security levels of industrial and supply chains.

Regularly arrange for authoritative figures to communicate with general partners (GPs) on industrial trends and pain points, interpret the outline and goals of the national industrial development plan, and guide them to focus on specialized and special new enterprises and strategic emerging industries.

6.2.2. Enhance the Governance Role of Government Venture Capital

Strengthen the governance role of government venture capital for “little giant” enterprises and increase support through various resources. To start, ensure long-term investment in “little giant” enterprises. Reasonably determine the duration of government investment funds, give full play to the cross-cyclical and counter-cyclical adjustment functions of funds as long-term and patient capital, and actively guide the participation of long-term capital, such as the National Social Security Fund and insurance funds.

Optimize post-investment management. Provide professional non-capital value-added services, such as board supervision, joint investment, market connections, and core team training, to assist enterprises in improving corporate governance, obtaining long-term funding, unblocking market channels, and enhancing the team level.

6.2.3. Improve the Coordination Mechanism

Improve the coordination mechanism between government venture capital and government subsidies. The government should further refine the synergy mechanism between them and clarify their functional positioning and complementary relationships. Government venture capital should focus on supporting enterprises’ long-term innovation and market-oriented projects, while government subsidies should target enterprises’ short-term innovation needs.

Government venture capital should pay more attention to strategically important industries that lack government subsidy support to fill the policy gap. When selecting investment projects, guided fund management institutions should have some flexibility in the innovation achievement output requirements, attach more importance to the long-term sustainability and growth of innovation, as well as its macro-economic impact, and balance the two principles of policy objectives and market-oriented operation during investment.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study has several limitations that warrant further investigation in subsequent research.

First, while we focus on firm-level indicators, other factors—such as investment scale, financing rounds, and social networks—may also influence the innovation performance of specialized and sophisticated “little giant” enterprises supported by government venture capital. These variables were not included in the current analysis but should be explored in future work.

Second, due to data constraints in the Zero2IPO database, certain funds—such as those solely owned by local governments—may not be fully captured, even though their policy effects are similar. Given the challenges in obtaining comprehensive data, our sample was restricted to funds explicitly classified as “government-guided” in the database, which may have affected the robustness of our findings. Future studies should seek to incorporate a more representative sample.