1. Introduction

Green Human Resource Management (GHRM) has increasingly gained significant global attention. It has become a focal point in organisational strategies worldwide, reflecting organisations’ growing emphasis on sustainability and environmental stewardship [

1]. GHRM involves integrating environmental management principles into human resource policies and practices to promote sustainable behaviour among employees and support the organisation’s overall environmental goals [

2]. As businesses are increasingly held accountable for their environmental impact, GHRM implementation has become a key driver for achieving corporate sustainability. GHRM works as a subsystem embedded within wider organisational and institutional systems, which includes interactions with strategy, operations, leadership, supply chain, and national sustainability frameworks [

3]. In the existing GHRM research area, Tang’s five-dimensional model of green HR practices has gained widespread recognition [

3]. These five dimensions include green recruitment and selection, green training, green performance management, green reward and compensation, and green empowerment and involvement [

4].

The global push for sustainable development, such as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) places an imperative on all regions to adopt more sustainable business practices, which also includes Africa. As a region characterised by unique cultural, socio-economic, and environmental dynamics [

5], Africa’s rapid population growth, urbanisation, and economic development are accompanied by stern environmental challenges, including deforestation, water scarcity, and climate change impacts [

6]. These challenges necessitate implementing sustainable business practices, including GHRM practices, to mitigate environmental degradation and promote sustainable development. Furthermore, Africa’s diverse cultural landscape plays a crucial role in shaping organisational practices [

7]. Cultural values, beliefs, and norms influence organisations’ perceptions of environmental issues. For instance, communal values and respect for nature are deeply ingrained in some African societies, potentially supporting GHRM implementation [

8].

African countries such as Ghana, Nigeria, and Kenya are heavily reliant on natural resources, with sectors such as agriculture, mining, and oil and gas playing a critical role in economic development [

9]. However, these sectors are also major contributors to environmental degradation. GHRM implementation can help these industries balance economic growth with environmental sustainability by fostering a culture of environmental responsibility within organisations [

10]. Moreover, the business model in Africa is characterized by a high prevalence of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), informal sector activities, and varying levels of institutional development [

11]. These factors can either facilitate or hinder the implementation of GHRM practices. For instance, SMEs might face resource constraints that limit their ability to implement GHRM due to their limited budget, while organisations in more developed institutional environments may benefit from stronger regulatory frameworks and incentives for sustainability [

12]. Understanding these contextual factors is essential for developing strategies to adopt GHRM practices across the continent.

Given the increased research interest in GHRM and the growing body of literature, a number of systematic literature reviews on GHRM have been conducted at a global level [

1,

3,

10,

13,

14], which could limit the development of context-sensitive theoretical models that reflect the continent’s institutional diversity and unique environmental challenges. The extent to which African organisations have embraced GHRM, and the specific challenges they face in doing so, are not well-documented in the existing GHRM literature [

10]. The reliance on frameworks developed from the global perspectives could risk misalignment with Africa’s distinct realities, such as its high prevalence of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), informal sectors, and strong socio-cultural influences, and which ultimately fail to capture the continent’s unique drivers, implementation, barriers to GHRM practices. Apart from that, this misalignment also prevents policymakers, HR practitioners, and development agencies from understanding how GHRM can be best mobilised to support sustainable development on the continent. As such, given the uniqueness of the African context as discussed above, the recent development of GHRM research in Africa necessitates a systematic review of the current state of GHRM in Africa. This paper undertakes this review, taking stock of the relevant research and developing a conceptual framework to take account of the existing research. This framework not only provides a comprehensive understanding of how GHRM is being implemented across the continent, the challenges and opportunities, and how GHRM has been adapted to local socio-cultural and economic contexts, but also helps to identify gaps in knowledge and areas where further research is needed. This knowledge is essential for advancing both theory and practice in the GHRM area, ultimately contributing to the broader goal of sustainable development in Africa. This review is guided by the following research questions:

RQ1. What green human resource management issues/topics have been explored in the African context?

RQ2. What theories and methodologies are used in these studies and in what context (in terms of countries and industries)?

RQ3. What more can be done in future research on green human resource management in Africa?

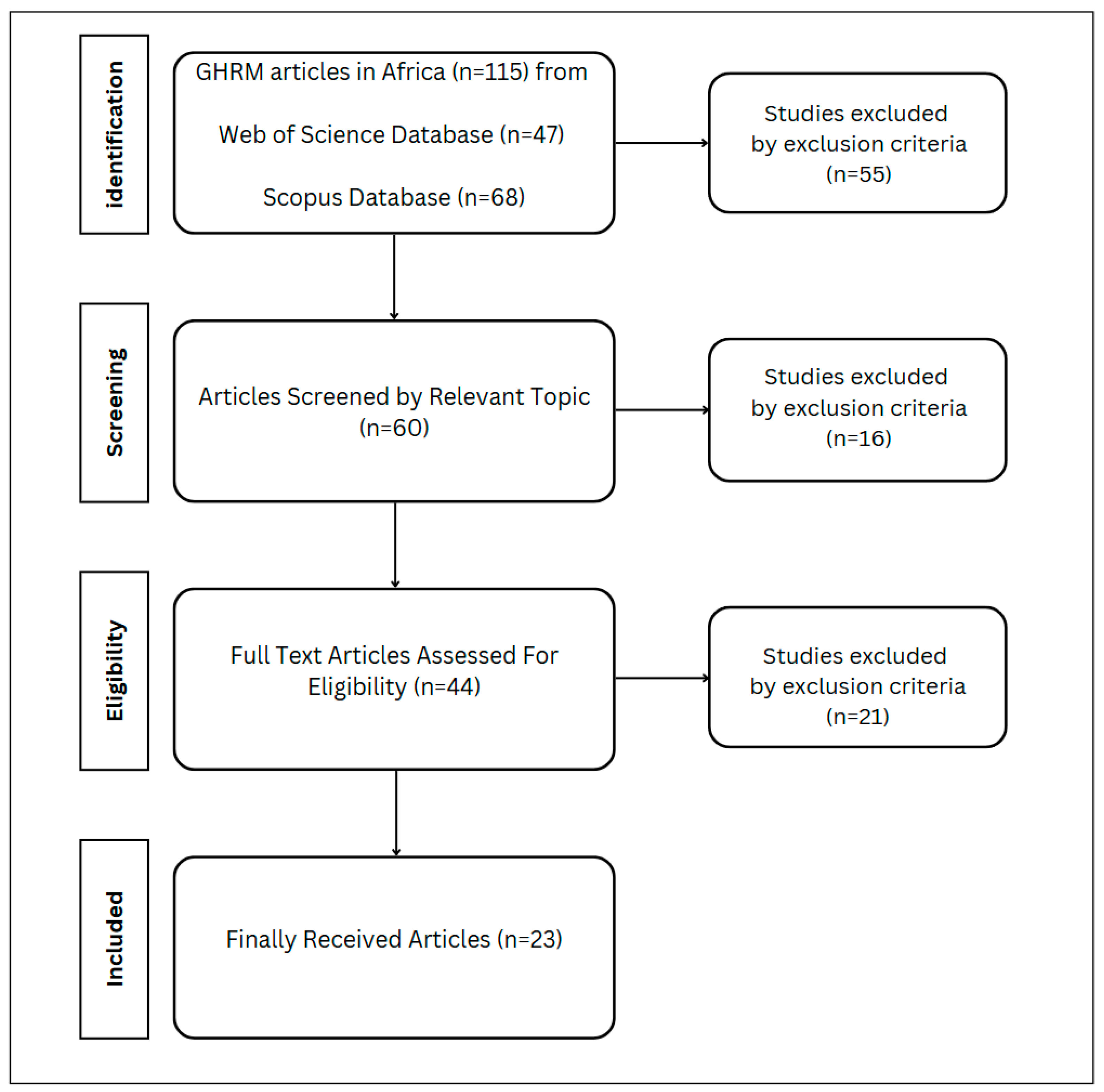

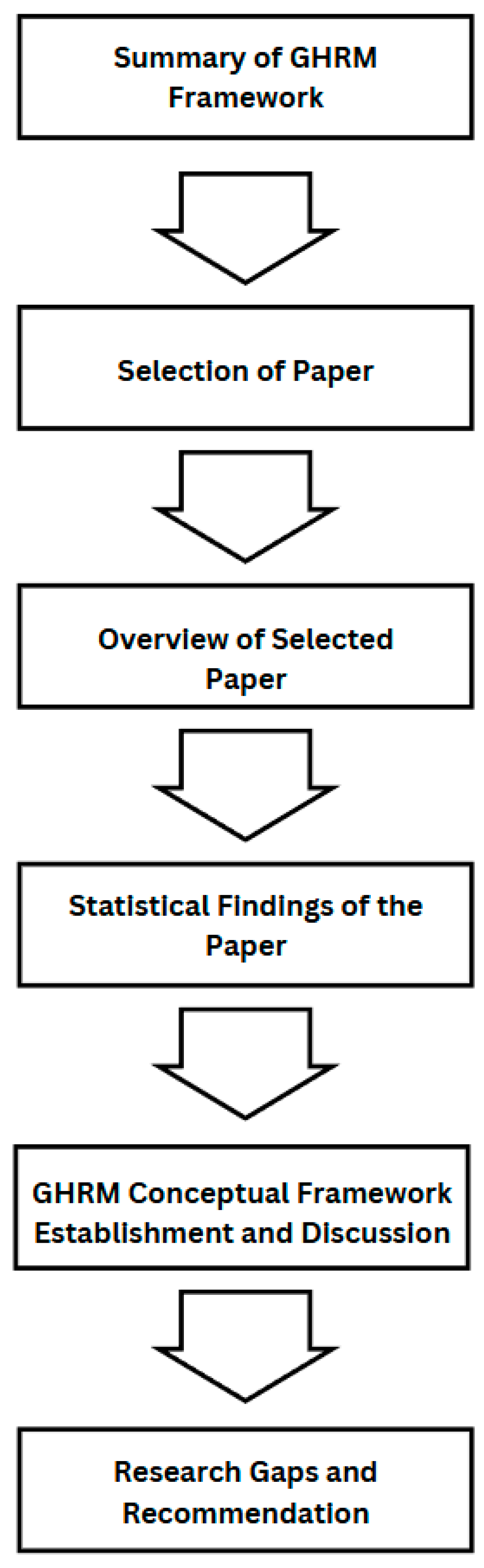

Finally, the structure of this paper is outlined as follows:

Section 2 introduces three GHRM frameworks that have been established by other researchers.

Section 3 presents the methodology, including the information sources and article search strategy, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and the research process.

Section 4 comprises a content analysis of the selected studies, including their research focus, theoretical underpinnings, and empirical findings.

Section 5 offers statistical and visual analyses of the selected studies, highlighting key trends across countries, industries, and research methods.

Section 6 develops the conceptual framework based on the analysis results from

Section 4 and

Section 5 and provides the detailed discussions. Finally,

Section 7 concludes the selected paper with theoretical and practical implications, limitations, and directions for future research.

4. Overview of the Selected Studies

This section reports the research findings from the 23 studies included in this review, which helps to determine the current state of GHRM research in Africa and lays the foundation for the development of the conceptual framework established later in this review. It lists out the empirical findings of these studies. The antecedents of GHRM, the types of GHRM practices, the mediating and moderating factors and the outcomes of GHRM are identified as well, with the results shown in

Table 1.

Four papers from this systematic literature review consider the antecedents of GHRM, Zhou [

22] asserts that corporate social responsibility (CSR) rules need all the functional departments to take part in the green initiatives, especially the green sensitivity in the human resource management department. Based on that, their quantitative research in Ethiopia shown a positive relationship between CSR and GHRM implementation. Mtembu [

23]’s mixed method research in three South African higher education institutions to find out two prerequisites for the successful GHRM implementation which are to have enough knowledge of GHRM practices and to have relevant GHRM policies. In contrast to GHRM knowledge, Ogbeibu [

24]’s research is focused on technical knowledge’s role in GHRM implementation. The research result shows that the organisation’s capability in smart technology, artificial intelligence, robotics, and algorithms positively correlates with GHRM implementation. Finally, Sokro [

25]’s research on the antecedent of one of the GHRM practices: green participation and empowerment is conducted from the top management commitment perspective, their research shows that an inclusive leader who is willing to share information, cooperate and cultivate positive relationships with employees can make it easier for the employees feel empowered.

Suleman [

26]’s research adopts an inductive research method, which, through interviews with managers from five manufacturing companies in Ghana, identifies five Green Human Resource Management (GHRM) practices currently implemented in Ghana’s manufacturing sector: green recruitment, green training, green performance management, green rewards, and green participation. The findings are consistent with the five GHRM dimensions proposed by Tang [

4]. However, it is noteworthy that, based on the interview results, the green recruitment and green performance management practices currently implemented by these manufacturing companies remain at the level of digitalized processes, rather than being based on the candidates’ environmental friendliness when making hiring decisions or conducting performance evaluations [

26]. Emmanuel [

27]’s research adopts a literature review method to raise the conceptual viewpoint on the importance of implementing GHRM practices such as green training, green reward and green performance management in the Nigerian hotel industry.

Currently, two studies on GHRM in Africa have explored the barriers to GHRM implementation. One of these is a study from Egypt’s tourism industry [

28], where the researcher identified the GHRM practice’s application level by analysing 237 questionnaires completed by travel agency managers. They found the constraints for implementing GHRM practice in two categories: managerial and employee constraints. From the managerial perspective, there are four elements which are the failure to provide full support, the high cost of implementing GHRM practice, the weak incentive for implementing green initiatives and the lack of environmental policy among agencies. From the employee perspective, three elements are found out: insufficient awareness of environmental sustainability, lack of skill to adapt to green technology, and difficulty in changing the culture of the current staff. Tweneboa [

29]’s study on GHRM barriers was conducted in Ghana. The researchers first reviewed the barriers identified in the existing GHRM literature. Based on the literature review results, they designed a questionnaire and, combined with interviews with managers, finally identified five dimensions of GHRM barriers. These barriers were then ranked in order of significance, from most significant to least. The order is as follows: (1) economic barrier, (2) political and regulatory barrier, (3) technical barrier, (4) management barrier and (5) culture and education.

Research on GHRM outcomes still dominates the GHRM research area. This part of the content analysis of the research paper divides the GHRM practice outcomes into organisational and individual levels. Several studies found that GHRM can directly help increase organisational green performance [

22,

24,

26,

30]. The GHRM practices are regarded as a collection of HRM techniques that reduce the polluting effect to increase the organisation’s green performance.

Two studies discussed the mediating role that corporate reputation plays [

31,

32], Afum [

31]’s research in 164 Ghanaian firms showed that corporate reputation can play a mediating role between GHRM and organisational environmental performance as well as financial performance through RBV theory. Mensah [

32] found out that green corporate reputation mediates the relationship between GHRM practices and environmental performance, as green corporate citizenship mediates the relationship between GHRM practices and financial performance.

Another mediating role that has been used from the organisational perspective is the green innovation, two studies have found out that green innovation can play a mediating role between GHRM practices and organisational non-green performance [

33,

34]. Suleman [

34]’s research was conducted in five Ghanian mining firms, which found out that green innovation can mediate the role between GHRM practices and financial performance as well as social performance, but not environmental performance. Obeng [

33]’s study shown that green innovation can mediate the role between GHRM practices and organisational competitiveness among 231 Ghanian manufacturing multinational firms through NRBV theory. Apart from that, Obeng [

33] also found that organisational learning can positively moderate the relationship between GHRM practices and the organizational competitiveness.

Al Kerdawy [

30]’s survey study in Egyptian firms found that corporate support for employee volunteering can moderate the relationship between GHRM practices and the firm’s economic performance, environmental performance and social performance.

Like some studies in other countries [

35,

36], the GHRM study is sometimes intersected with other green management practices, the most common being Green Supply Chain Management (GSCM) [

35,

36]. In the African GHRM research context, two studies have mentioned the relationship between GHRM practices and GSCM [

37,

38]. Acquah [

37]’s research in Ghanian manufacturing and hospitality firms found out that GSCM can mediate the role between GHRM practices and both organisational and environmental performance. Gelagay [

38]’s research found that two GSCM practices internal environmental management and eco-design plays a mediating role between GHRM practices and operational performance.

Three studies in this review analyse the GHRM outcome from both organisational and individual levels [

39,

40]. Suleman [

40]’s research found that GHRM practices are positively related to employee environmental commitment, which leads to the improvement of environmental sustainability and employee turnover intention. Muisyo [

39] found out that GHRM practices can foster a green culture in Kenyan hotels, which enables both collective and individual green creativities. Moreover, environmentally specific servant leadership can moderate the relationship between GHRM practices and organisational green culture [

39]. The research surveys the views of 215 job-seeking students on whether adopting green recruitment practices can influence their job pursuit intention. The results show that the degree of green recruitment implementation can increase the organisation’s attractiveness and prestige, finally positively increasing the organisation’s job pursuit intention.

Finally, six studies were conducted on the GHRM outcome from individual perspectives [

25,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45]. Five studies focused on how GHRM practice can increase employee green behaviour. Nurul [

43]’s research is based on the social exchange theory, and their research shows that four GHRM practices green training, green reward, green performance management appraisal and green empowerment can increase employee green commitment and finally increase their pro-environmental behaviour in Nigerian hotels, employee’s green self-efficacy can help to moderate the relationship between GHRM practices and employee green commitment. Another study conducted in Nigerian construction firms shows that eco-spirituality plays a mediating role between green training and voluntary workplace green behaviour [

45]. Andoh [

41]’s research is also only focused on green training; their research in the hotel industry shows that green training moderates the relationship between green knowledge sharing and employee green behaviour. Ogiemwonyi [

44]’s research found out the three GHRM practices GRS, GT, GPM can help the firm to transform their employee into green human capital and finally increase the employee’s green behaviour. Aly [

46]’s research is focused on both employee green and non-green factors, their study testify the mediating role that employee green behaviour plays between GHRM practices and employee subject wellbeing in small-to-medium-sized enterprises (SMES) in Ghana. Besides that, the more resource commitment the organisation has, the higher the relationship between GHRM practices and employee’s subjective well-being. Finally, Sokro [

25]’s survey conducted in 500 public sectors found that green empowerment and participation positively correlate with employee engagement.

Table 1.

Antecedents, practices, mediating roles, moderators and outcomes of the quantitative studies among selected studies.

Table 1.

Antecedents, practices, mediating roles, moderators and outcomes of the quantitative studies among selected studies.

| Paper | Theory | Antecedent | GHRM Practice | Mediator | Moderator | Outcome | Industry | Country | Year |

|---|

| [30] | SET | - | GRS, GT, GPM, GCR | - | CSEV | FP, SP, EP | Not mentioned | Egypt | 2018 |

| [37] | - | - | GRS, GT, GEI, GPM, GCR | GSPM | - | EP, SP | Manufacturing/Hospitality | Ghana | 2020 |

| [31] | RBV | - | GRS, GT, GEI, GPM, GCR | CR | - | EP | Oil & Gas/Manufacturing | Ghana | 2021 |

| [32] | - | - | GRS, GT, GR, GPM | GCC | - | OP, EP, GCR | Oil & Gas | Ghana | 2021 |

| [39] | LT | - | GT, GPM, GPR | GWC | ESSL | GC | Hospitality | Kenya | 2022 |

| [33] | NRBV | - | GT, GPM, GEI | GI | OL | OP | Manufacturing | Ghana | 2023 |

| [22] | AMO RBV | CSR | Not mentioned | - | - | EP | Manufacturing | Ethiopia | 2023 |

| [44] | SCT | - | GRS, GT, GPM | GHC | - | EGB | Hospitality | Nigeria | 2023 |

| [40] | LT SET | - | GRS, GT, GEI, GPM, GCR | EGC | - | ETI, EP | Manufacturing | Ghana | 2023 |

| [43] | SET | - | GT/GCR/GPM/GEI | EGC | GSE | EGB | Hospitality | Nigeria | 2023 |

| [39] | LT | - | GT, GPM, GPR | GWC | ESSL | GC | Hospitality | Kenya | 2022 |

| [25] | LME | IL | GEI | - | - | EE | Public Factor | Ghana | 2023 |

| [24] | STT DCT | OSC | GRS, GPM(-), GT | - | OSC | EP | Manufacturing | Nigeria | 2024 |

| [42] | Not Mentioned | - | GT, GPM, GCR | EGB | RC | EW | Manufacturing | Ghana | 2024 |

| [41] | SLT | GKS | GTD | GKS | GTD | OCEB | Hospitality | Ghana | 2024 |

| [47] | ST | - | GRS | OR, OA | - | JPI | University | Ghana | 2024 |

| [34] | NRBV | - | GRS, GT, GEI, GPM, GCR | GI | - | FP, SP | Mining | Ghana | 2024 |

| [45] | SET AMO | - | GT | ECOS | - | EGB | Construction | Nigeria | 2024 |

| [38] | RBV | - | GRS, GT, GEI, GPM, GCR | ED, GSCM | - | OP | Manufacturing | Ethiopia | 2024 |

5. Statistical Findings of the Paper

This section provides a summary of the statistics related to the reviewed articles.

First, the word cloud, which shows the most repeated words, is shown in

Figure 3. In order to ensure accuracy, before loading the files into Python 3.11.13 programming, only the title, abstract, keywords, and main content were retained from all the research papers considered in this study. Through “PyPDF2”, “wordcloud”, “matplotlib”, “nltk”, “pillow”, and “numpy” libraries and relevant coding, words like “and”, “yes”, “is” which are irrelevant to the main themes of the study were excluded and the word cloud figure was generated after that. The result of the word cloud shows that the words or phrases “green human resource”, “employee”, “environmental management”, “manufacturing”, “green practice”, and “green innovation” repeatedly occur.

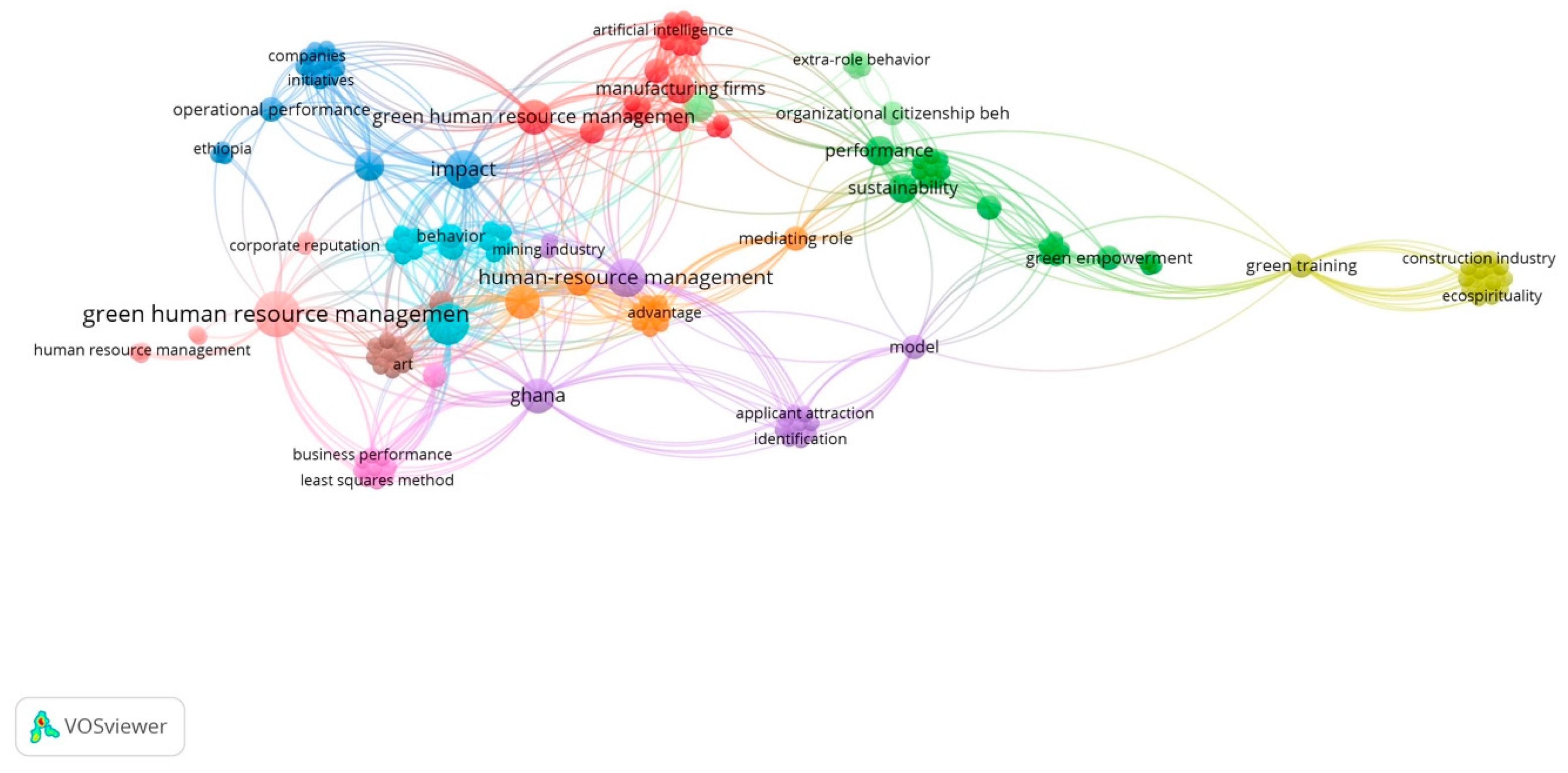

Furthermore, both the network visualisation and density visualisation of the keywords for all the studies have been shown through the software VOSviewer 1.6.20 [

48]. Network visualisation (

Figure 4) shows the relationships and connections between items in the network and, finally, identifies the main themes and trends in a research field. Density visualisation is used to provide an overview of the distribution and density of items in a network [

48].

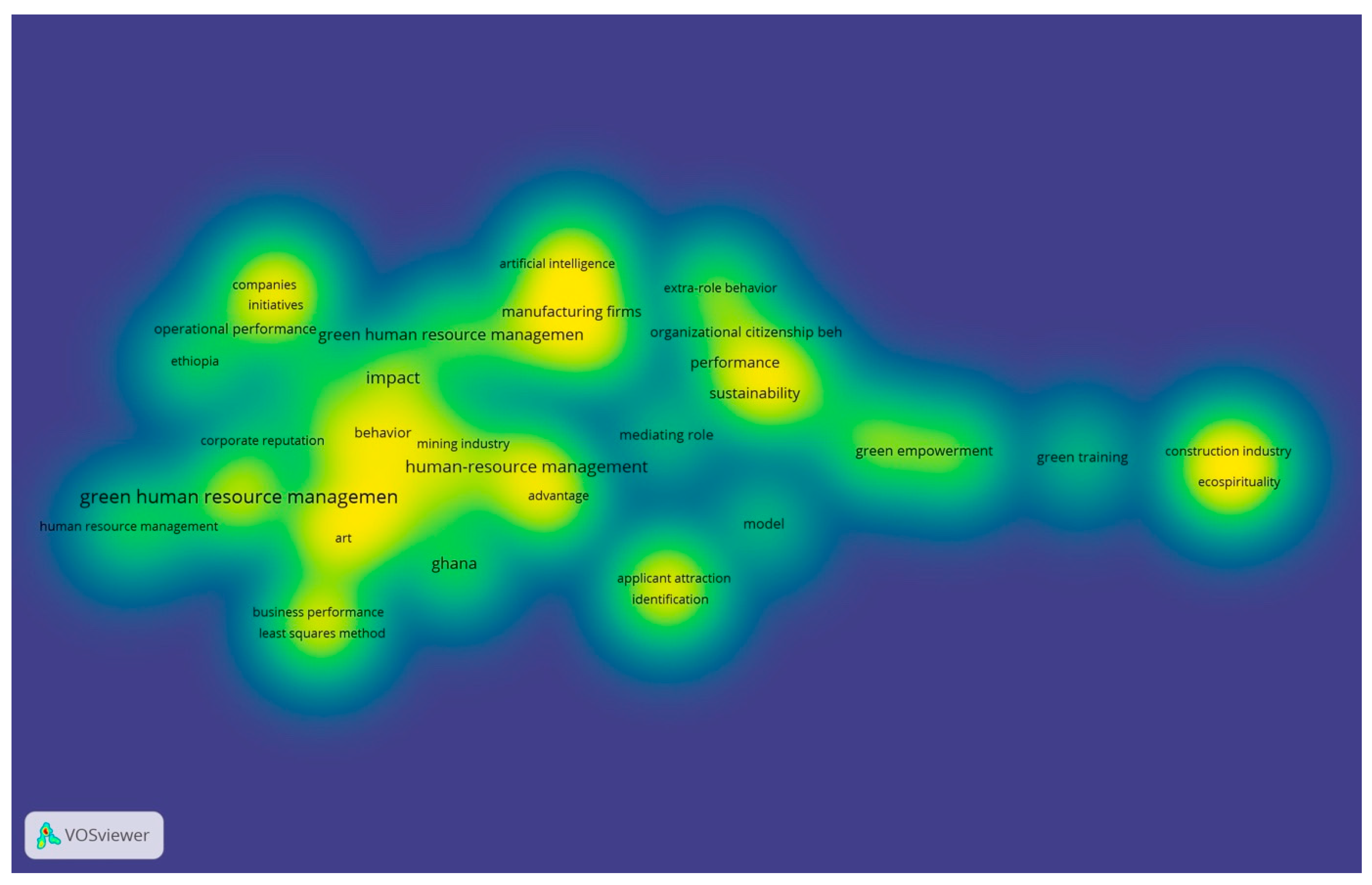

Different colours in the density visualisation of GHRM (

Figure 5) mean different density values. The higher density colour (normally prone to yellow) shows the more frequently used themes [

48]. For instance, themes like “green human resource management” and “sustainability” have the highest yellow colour density, which means they are the main keywords in this literature review. Apart from these, the other words have higher density colours like “manufacturing”, “Ghana”, and “organisational citizenship behaviour” also show the trend of the existing GHRM study in Africa, which means that Ghana and the manufacturing industry have conducted the most research previously.

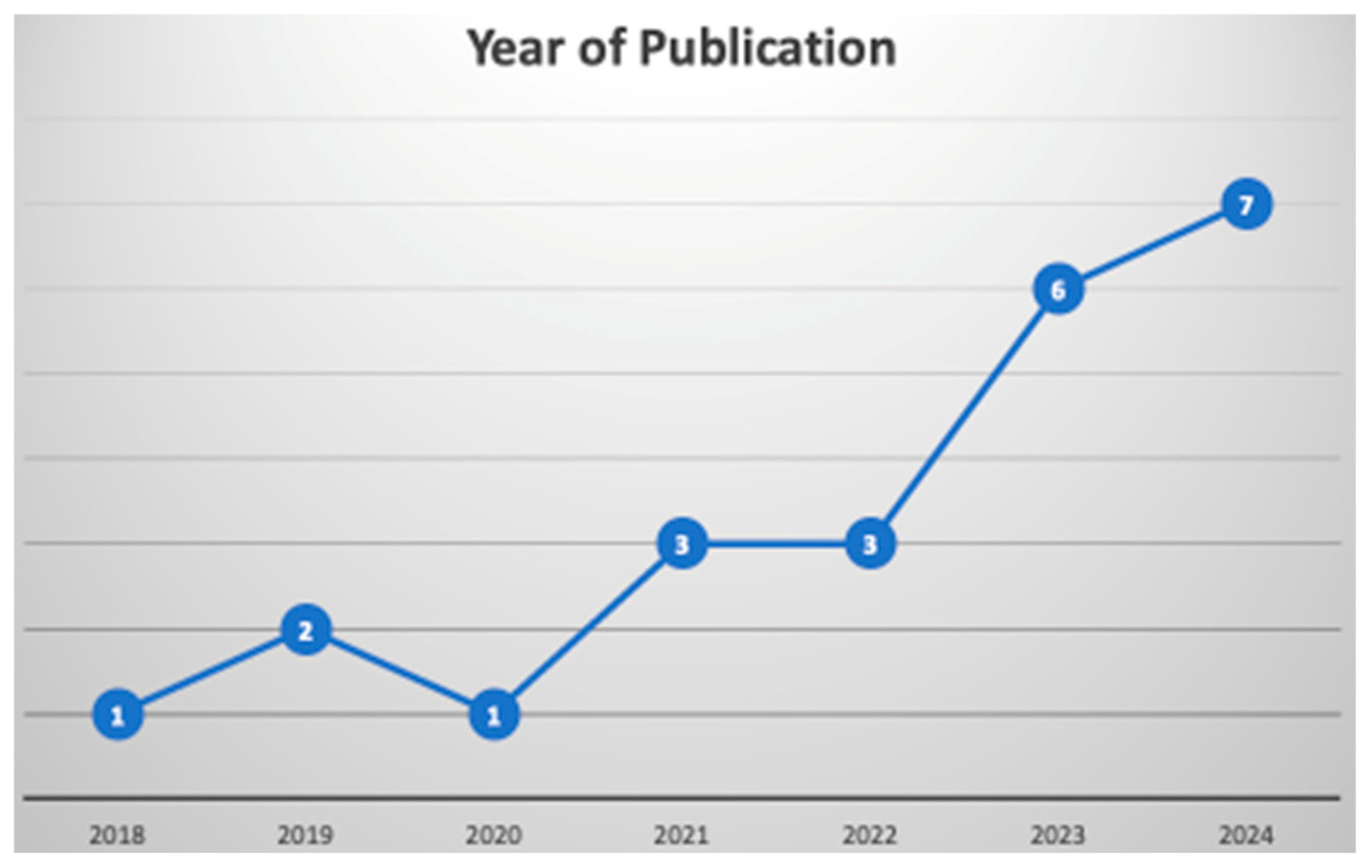

The year of publication of the papers is shown in

Figure 6. The result shows that all papers appeared between 2018 and 2024, with a significant number of them being published after 2022.

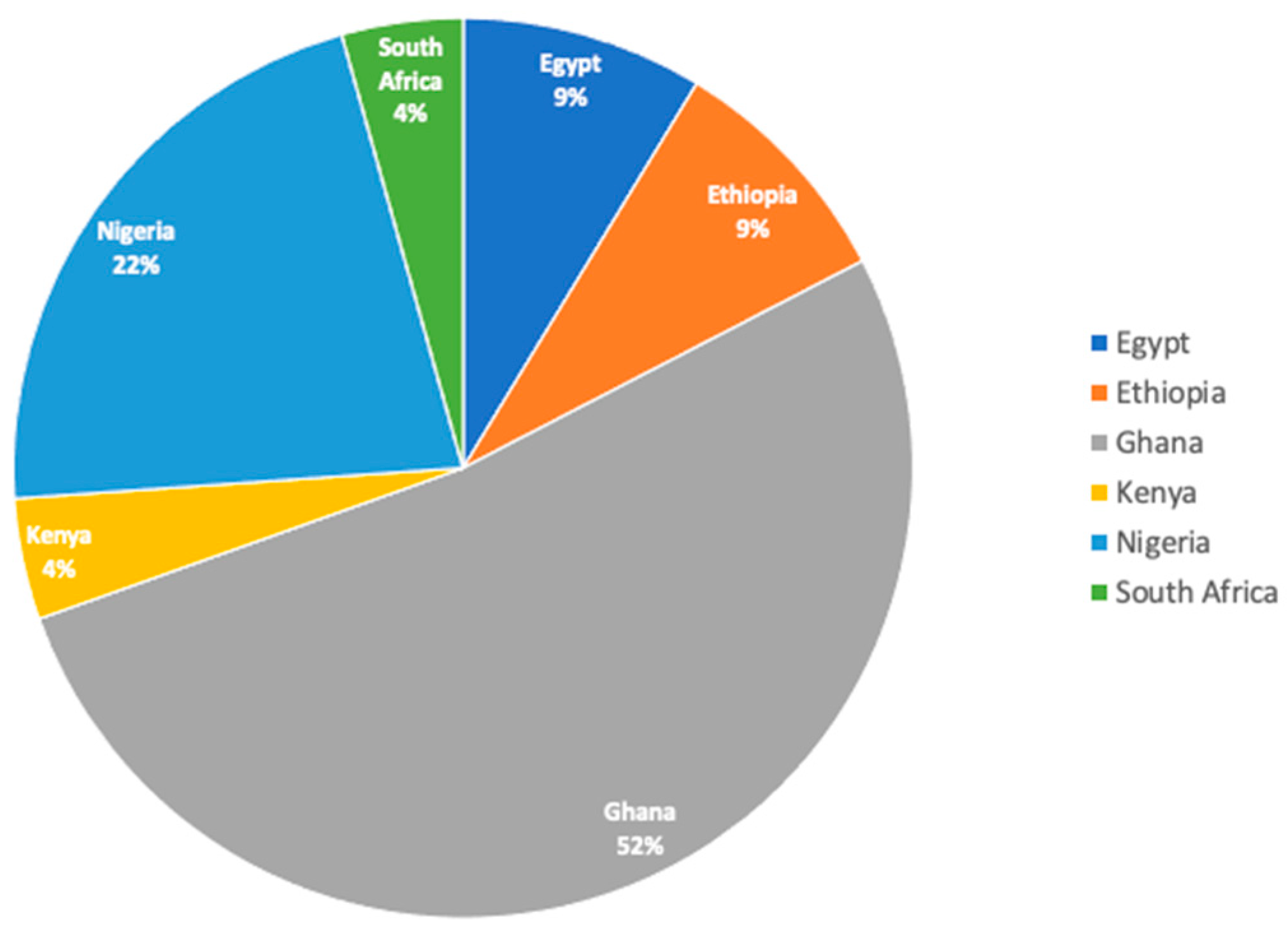

The reviewed studies were conducted in six African countries (

Figure 7). More than half (52%) of the research has been conducted in Ghana, followed by Nigeria, Ethiopia, and Egypt respectively. Only one study has been done in Kenya and South Africa.

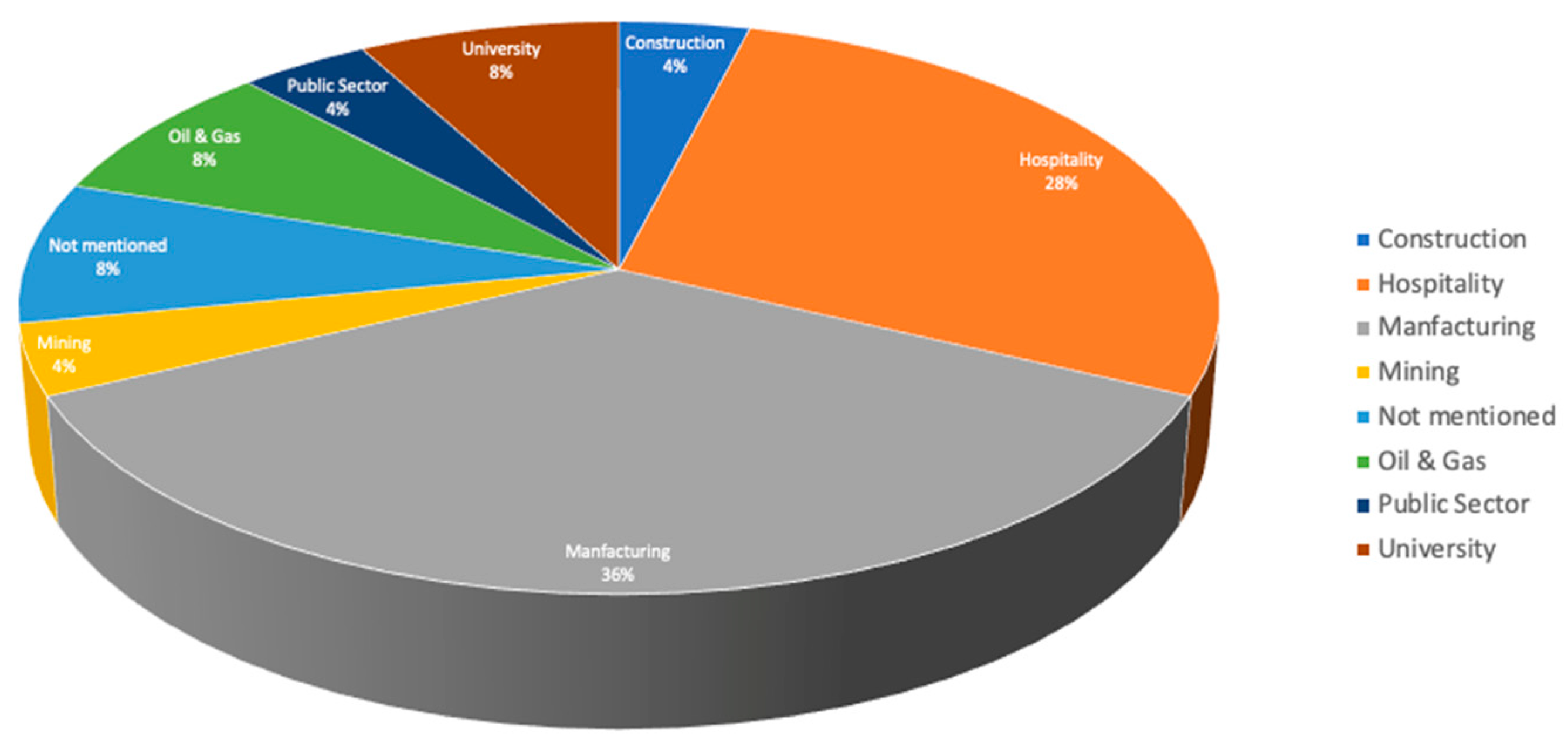

Seven industries involved in the studies are presented in

Figure 8. With respect to industry distribution, there have been seven different industries involved in the studies. From

Figure 8, it can be seen that 36% of the studies were conducted in the manufacturing sector, followed by hospitality, with 28%. Two studies were conducted in the oil and gas industry and in universities. Two studies did not mention the industry in which they were conducted. Only one study was conducted in each of the remaining industries.

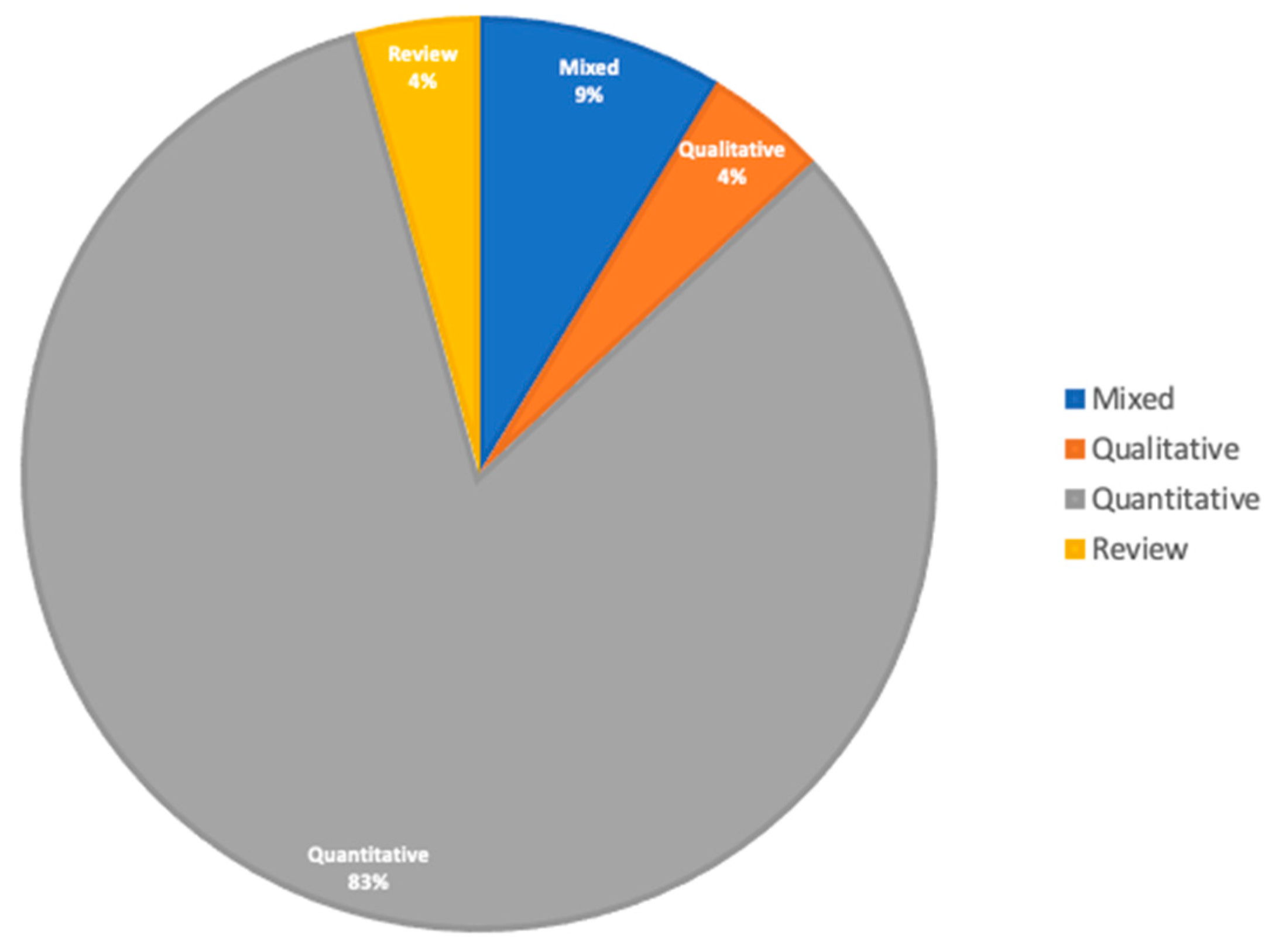

The research method of the papers in this review is shown in

Figure 9. Most of the studies (83%) adopted quantitative methods, followed by mixed studies, representing 9%. There was only one qualitative study and one review study. For the quantitative studies, several theories have been used as the theoretical framework to study the relationship between GHRM’s antecedent, practices and outcomes.

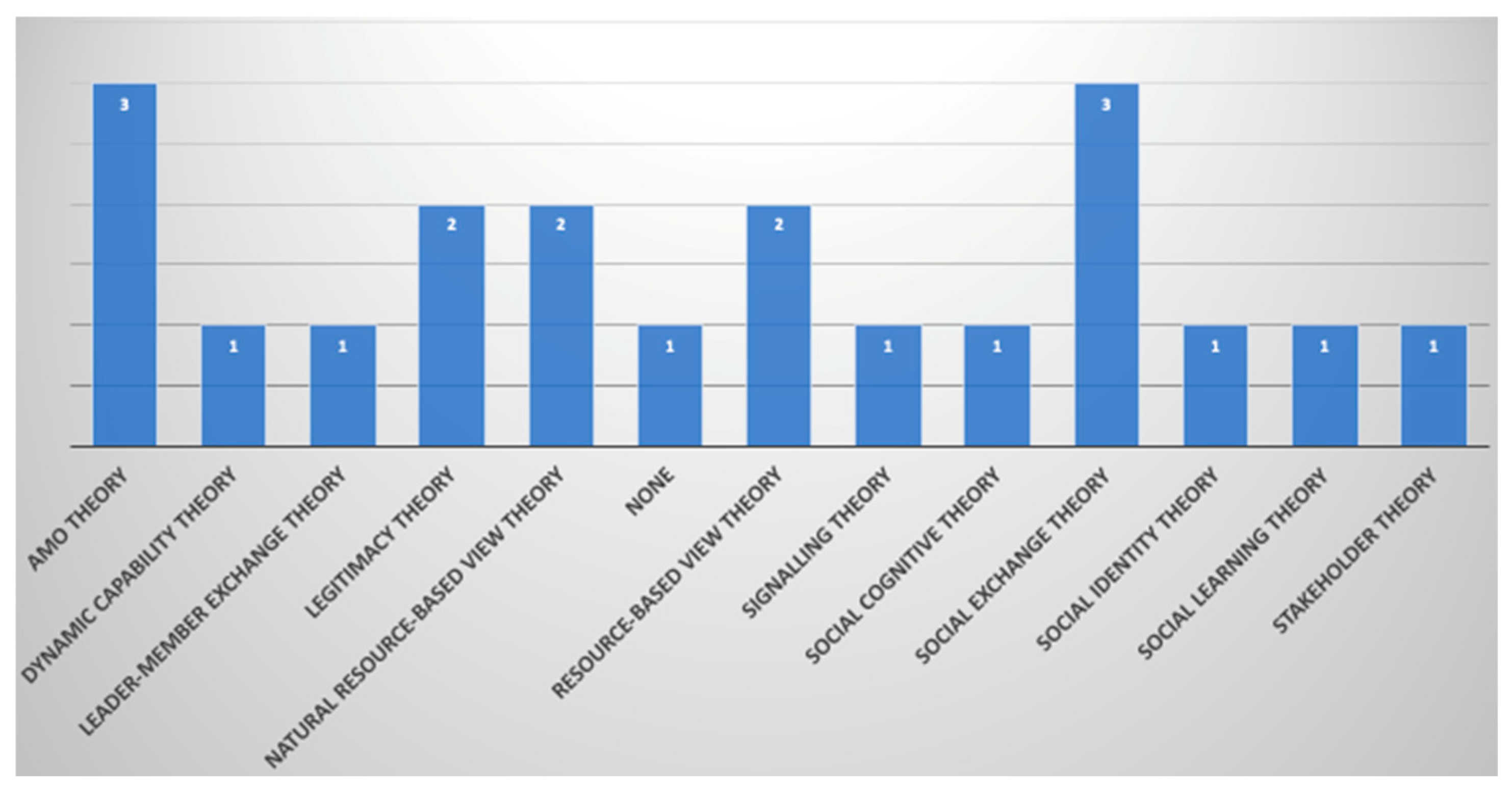

Figure 10 shows the underpinning theories that have been used in each study. Three studies deployed either AMO theory or social exchange theory (SET), followed by legitimacy theory (LT), natural resource-based view theory (NRBV) and resource-based view theory (RBV) which have two studies each. One study did not deploy any theory, while other theories were used by only one study. Finally,

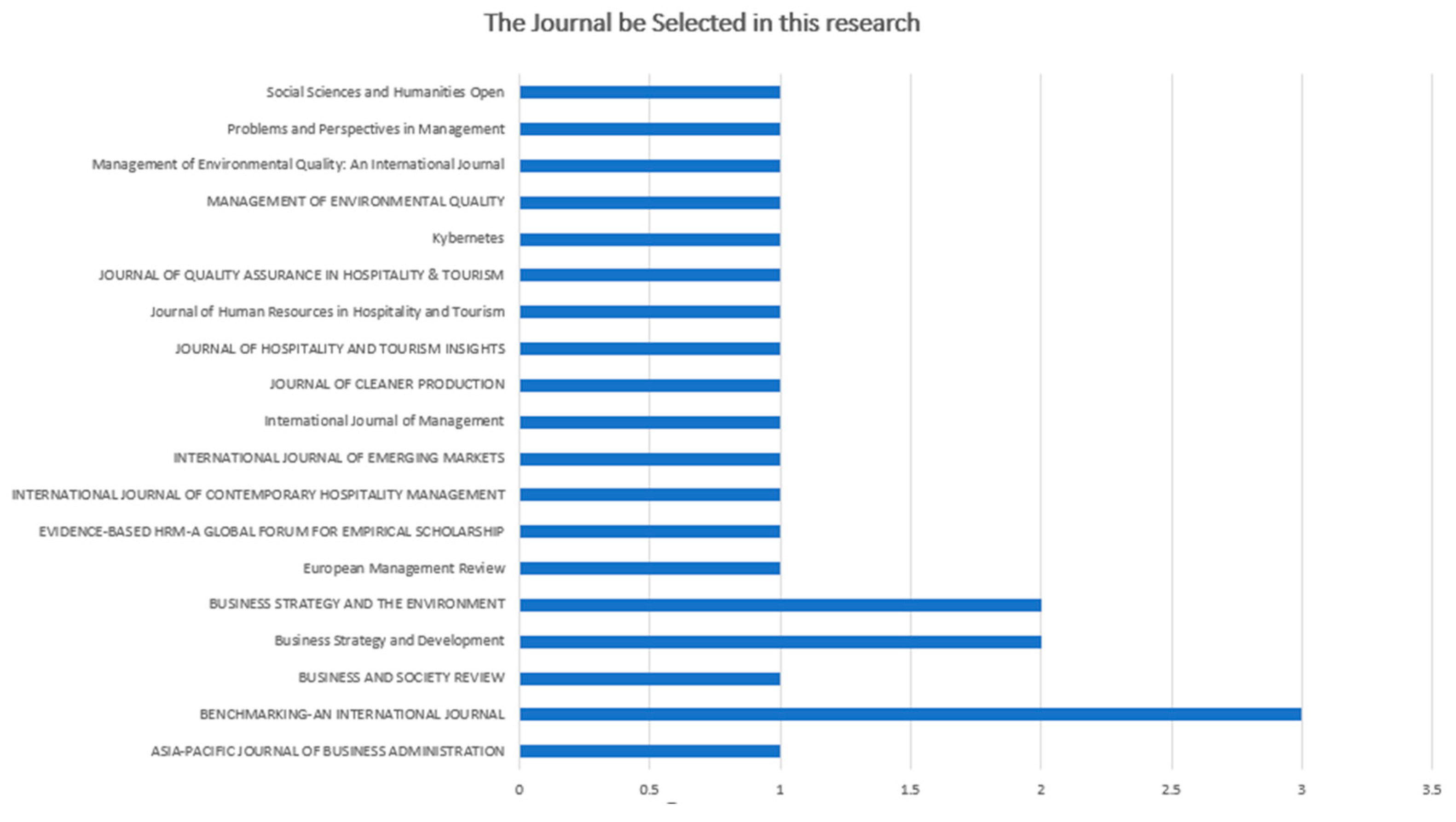

Figure 11 shows the academic journal being selected in this literature review.

6. Discussion and Recommendation for the Selected Studies

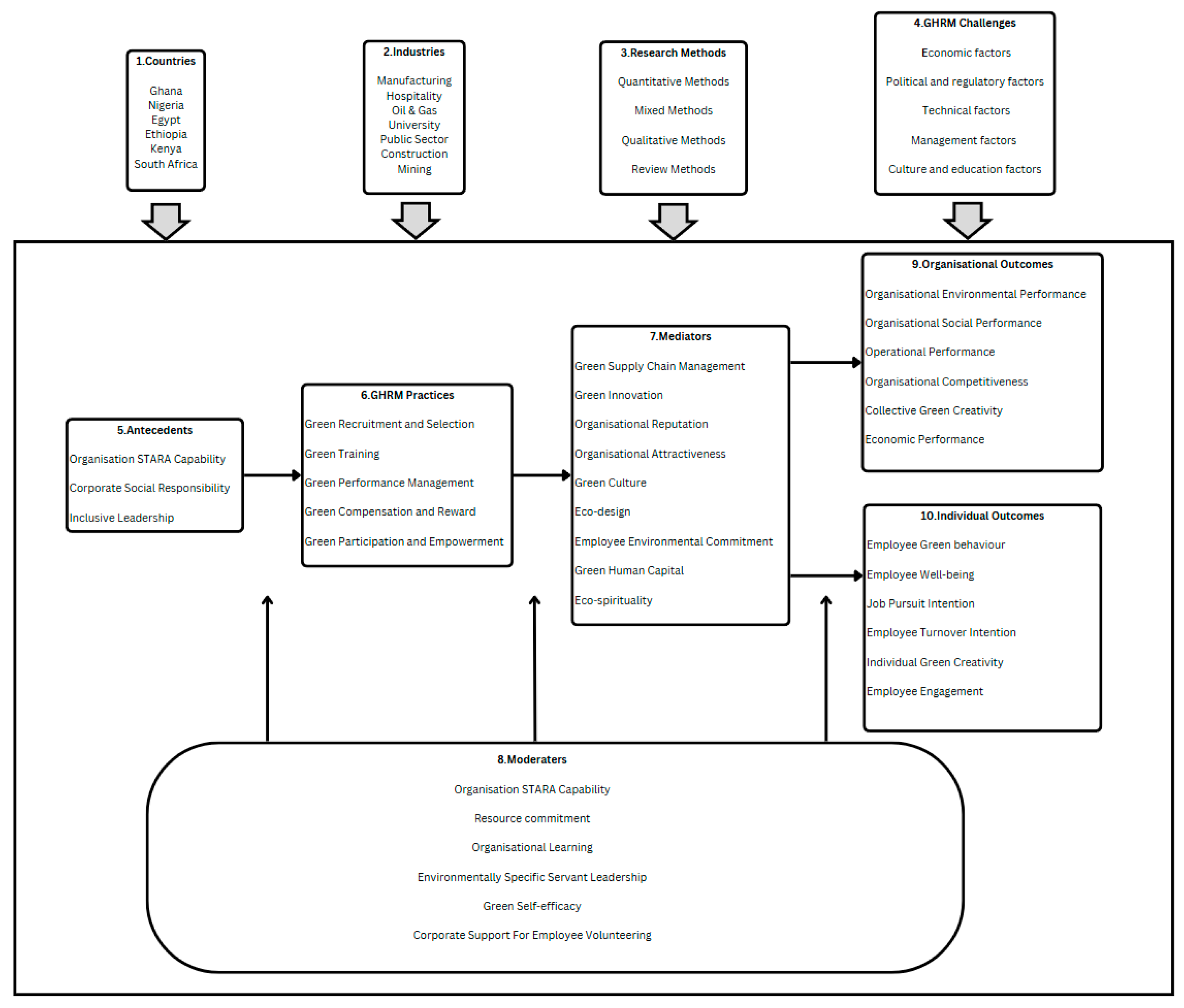

The framework related to Africa GHRM implementation is shown in

Figure 12, which contains ten different categories. The new finding from the African GHRM framework is that the inclusion of organisational capabilities in smart technologies, such as artificial intelligence, robotics, and algorithmic systems has been found as a factor that influences GHRM implementation. This aligns with the broader global trend of digital transformation and offers insights on how this integration of digital capabilities can influence GHRM implementation. The finding highlights the need to establish theoretical models to reflect how these new technological developments can influence GHRM implementation from other national contexts.

Nevertheless, this framework still remains relatively simple compared to other established GHRM frameworks. Comparing this framework with others can allow the researchers to identify the research gaps and future research directions within African GHRM studies.

Recommendation 1: Future GHRM studies in other national context should explore the role organisational capabilities in smart technologies, such as artificial intelligence, robotics, and algorithmic systems play in GHRM implementation.

First, the existing GHRM research in Africa is heavily concentrated in only a few countries and industries, particularly Ghana and Nigeria, with a primary focus on manufacturing and hospitality sectors.

Figure 7 shows that over half of the included studies were conducted in Ghana, followed by Nigeria, with industries primarily centred around manufacturing and tourism As shown in

Figure 8, 36% of the research focused on manufacturing industry, and 28% on hospitality industry. However, other important sectors such as agriculture, education, and non-profit organisations should also receive academic attention in future research. In Ghana, about 40% of the workforce was employed in agriculture [

49]. Agricultural enterprises have unique characteristics compared to those in other sectors. The natural environment heavily influences agricultural production, and the processing of agricultural products can significantly impact the environment, often resulting in pollution [

50]. With increasing consumer awareness around environmental protection and a growing demand for eco-friendly food products such as organic food, the need for environmentally sustainable and safe practices in agricultural enterprises has risen. The “green” and “sustainable” nature of agricultural businesses has become not just a national priority, but a global one. Additionally, most of the research (80%) has been conducted in for-profit organisations, with only one study conducted in the public sector [

25], and two studies conducted in universities [

23,

47], and neither of these two studies discussed the environmental outcome that GHRM practices can bring. Non-profit organisations are typically mission-driven, aiming to advance social, environmental, or community causes. Implementing GHRM may support their broader objectives of fostering sustainability and environmental stewardship, further strengthening their commitment to creating a positive societal impact [

51]. Therefore, future research on GHRM in Africa should broaden its scope beyond the hospitality and manufacturing industries.

Recommendation 2: Future GHRM studies in Africa should explore industries beyond hospitality and manufacturing.

From this literature review, studies on GHRM in Africa were primarily concentrated in individual countries. Future studies could consider conducting cross-country comparisons within the same industry. Ghana and Nigeria are the two countries with the most GHRM studies, many of which focus on similar industries but yield different results. For instance, Gyensare [

42] found that green performance management can increase employee green behaviour, while Ogbeibu [

24]’s study showed that green performance management did not improve environmental performance in Nigerian manufacturing firms. These inconsistencies highlight the importance of national context in finding out how GHRM practices are implemented and perceived. Cross-country comparative research could provide new findings and determine the context-specific influences. As such, future research could explore manufacturing in both countries simultaneously, potentially uncovering new insights.

Recommendation 3: Future GHRM African studies could compare the implementation and impact of GHRM across different countries.

The review also revealed that there has been a lack of methodological diversity in the existing African GHRM studies. When comparing the framework used in this paper with those from previous studies [

3,

10,

14], very few new factors were identified. This is mainly because of the predominance of quantitative research in African GHRM studies, which mostly rely on surveys and hypotheses drawn from the previous studies. However, Africa, with its unique cultural, socio-economic, and environmental dynamics, may have distinct phenomena in GHRM areas that remain unexplored. Future studies can adopt inductive approaches. For instance, two studies on GHRM barriers from this review are both quantitative. The barriers they mentioned were mainly obtained from the previous studies in other national contexts before they designed and conducted their surveys in African firms. As such, some challenges unique to African businesses might be neglected. Suleman [

26] found that Ghanaian manufacturing firms are still implementing GHRM practices at a digital process level rather than considering environmental friendliness when hiring or evaluating employees. Future research can use interviews with HR managers to fill these gaps. Another gap which inductive research can address is to redefine the GHRM practices. Nearly all studies in Africa currently adopt Tang [

4]’s five dimensions of GHRM practices, while other GHRM review frameworks have found that there have been some other GHRM practices that have been adopted in other national contexts. It is suggested that some case studies could reveal other practices, such as green work-life balance, green grievance handling, or green health and safety.

Recommendation 4: Qualitative or mixed-method research should be considered in future GHRM studies in Africa.

Furthermore, the drivers and antecedents of GHRM adoption were underexplored in African research. Compared to Ren [

3]’s framework which has several GHRM drivers and antecedents, significant potential has been remained for research on GHRM drivers. Existing GHRM studies in African context have rarely explored external drivers like regulations, external stakeholders, national cultural values, or the role of labour unions in GHRM implementation. Additionally, individual drivers, such as employee attitudes and perceptions toward GHRM policies, which can determine whether GHRM is successfully implemented, are also under-researched. The effectiveness of GHRM systems sometimes depends on their alignment with external institutions, including government policy, educational systems, and industry norms, suggesting that GHRM cannot be treated in isolation from broader environmental governance frameworks. Thus, future African GHRM studies should investigate the reasons why companies implement GHRM practices.

Recommendation 5: More research is needed to investigate the drivers and antecedents of GHRM implementation in future African GHRM studies.

The reviews shows that the potential negative effects from GHRM implementation are still rarely addressed in African studies. Compared to drivers, there is already considerable research on GHRM outcomes and all are associated with positive GHRM outcomes. However, recent studies have started to explore the “dark side” of GHRM. For instance, Yuan [

52]’s research in China found that GHRM can lead to employee emotional exhaustion. Pham [

53] found that green performance management in Malaysian hotels led to increased stress, especially among less motivated employees. Increasingly, studies have shown that GHRM can have negative outcomes as well as positive. Future African GHRM research should also consider these negative aspects.

Recommendation 6: Future studies should investigate the potential negative outcomes of GHRM implementation in Africa.

Finally, the review also shows that there is still limited research on the role of leadership in GHRM. Ren’s review framework has emphasised the importance of finding how different types of leadership can influence GHRM implementation [

3]. While in the African GHRM studies, only two leadership styles: inclusive and environmentally specific leadership have been mentioned [

25,

39]. Top management commitment has consistently been identified as a critical factor for the success of GHRM implementation. Leadership plays a pivotal role in driving organisational change [

54], influencing employee behaviour, and fostering a green culture. Understanding how different leadership styles impact the effectiveness of GHRM practices can provide insights into promoting sustainability and enhancing environmental performance in organisations [

3]. Future research could explore other leadership styles that have been found to influence GHRM in other regions, such as ethical leadership [

55], responsible leadership [

56], transformational leadership [

57], visionary leadership [

58], and exploitative leadership [

59].

Recommendation 7: Future research should explore how other leadership styles influence GHRM implementation in Africa.

7. Conclusions and Limitation

This review aims to identify research gaps, provide recommendations and propose a research framework for future studies in the GHRM field in Africa. This work reviews 23 GHRM-related publications in Africa, which have been systematised into the conceptual framework and categorised by countries, industries, research methods, GHRM challenges, antecedents, GHRM practices, mediators, moderators and outcomes.

Based on that, this study provides a pathway for future research in the GHRM area. First, future studies should broaden their industry focus beyond hospitality and manufacturing to include underrepresented sectors such as agriculture, education, and non-profit organisations, where GHRM can play a significant role in promoting its organisation’s environmental performance. Second, researchers are encouraged to conduct cross-country comparisons within similar industries to explore how national context shapes the implementation and outcomes of GHRM practices. From a methodology perspective, qualitative and mixed-method studies are encouraged to be carried out in the future GHRM studies to find out the context-specific practices and challenges that may be overlooked in the predominantly quantitative studies. Moreover, more attention should be given to the drivers and antecedents of GHRM implementation, including regulatory frameworks, cultural values, and employee perceptions. Furthermore, future studies should also consider the potential negative effects of GHRM like emotional exhaustion which have been underexplored in the African context. Another potential research gap occurs in how different types of leadership can influence GHRM implementation in the African context. Finally, future GHRM studies within Africa and globally should find out how organisational capabilities in smart technologies, such as AI and automation, influence GHRM adoption and integration.

7.1. Theoretical Implications

This review extends existing GHRM studies by developing a region-specific framework based on African empirical studies, incorporating ten key categories that reflect the local realities. From this framework, this review highlights some theoretical gaps in the African GHRM research area. First, the overreliance on quantitative methods and narrow the scope of adopted frameworks, chiefly that of Tang [

4]’s five GHRM dimensions, have limited African context-specific theory’s development. Hence, there is a need for inductive, qualitative approaches to design and find out the Africa-specific constructs and drivers. Furthermore, the emergence of organisational capabilities in smart technologies have been found out as a new factor in the African GHRM framework. This finding reflects the global trend of digital transformation and highlights the need to extend the existing GHRM theories to incorporate technological capability as a contextual factor. Finally, the geographic and industrial concentration also underscores the need to contextualise existing GHRM theories to Africa’s unique social background. This suggests a need for more interdisciplinary and context-sensitive theoretical models for the future research in the African GHRM research area.

7.2. Practical Implications

For practical implications, based on empirical studies, this review reveals all five GHRM practices [

4] have become essential factors in helping the firms increase their organisational performance from both green and non-green perspectives. Therefore, these GHRM practices may be beneficial for companies that implement them. Apart from that, GHRM practices can also increase the performance of other green management, such as green supply chain management, which can have additional beneficial effects for the firms who have already implemented GSCM [

38]. Policymakers and businesses are encouraged to prioritise underrepresented industries like agriculture. Organisations should keep their eyes on the negative effects that GHRM may bring when they are implementing those GHRM practices. Also, leadership development should not be neglected as well; managers require certain training to be equipped with those types of leadership to help establish the green business culture. Finally, it is advised that integrating AI programs can enhance the effectiveness of the organisation’s sustainable development strategy. For instance, Ogbeibu [

24]’s research showed that an organisation’s capability in smart technology, artificial intelligence, robotics, and algorithms can increase the success of GHRM implementation.

7.3. Limitations

It is important to acknowledge this study is not without limitations. First, relying on keyword searches may not guarantee completely comprehensive results. While efforts were made to address this by reviewing additional GHRM-related works in Africa from reputable sources, we cannot claim that this method is the most effective for identifying all relevant publications. Second, this paper only includes English-language studies. Considering that French is widely spoken in several African nations, future research could incorporate studies in other languages to provide a broader context.