Synergistic Rewards for Proactive Behaviors: A Study on the Differentiated Incentive Mechanism for a New Generation of Knowledge Employees Using Mixed fsQCA and NCA Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Design

2.1. Theoretical Foundation and Model Construction

2.1.1. Outcome Variables

2.1.2. Selection of Antecedent Conditions

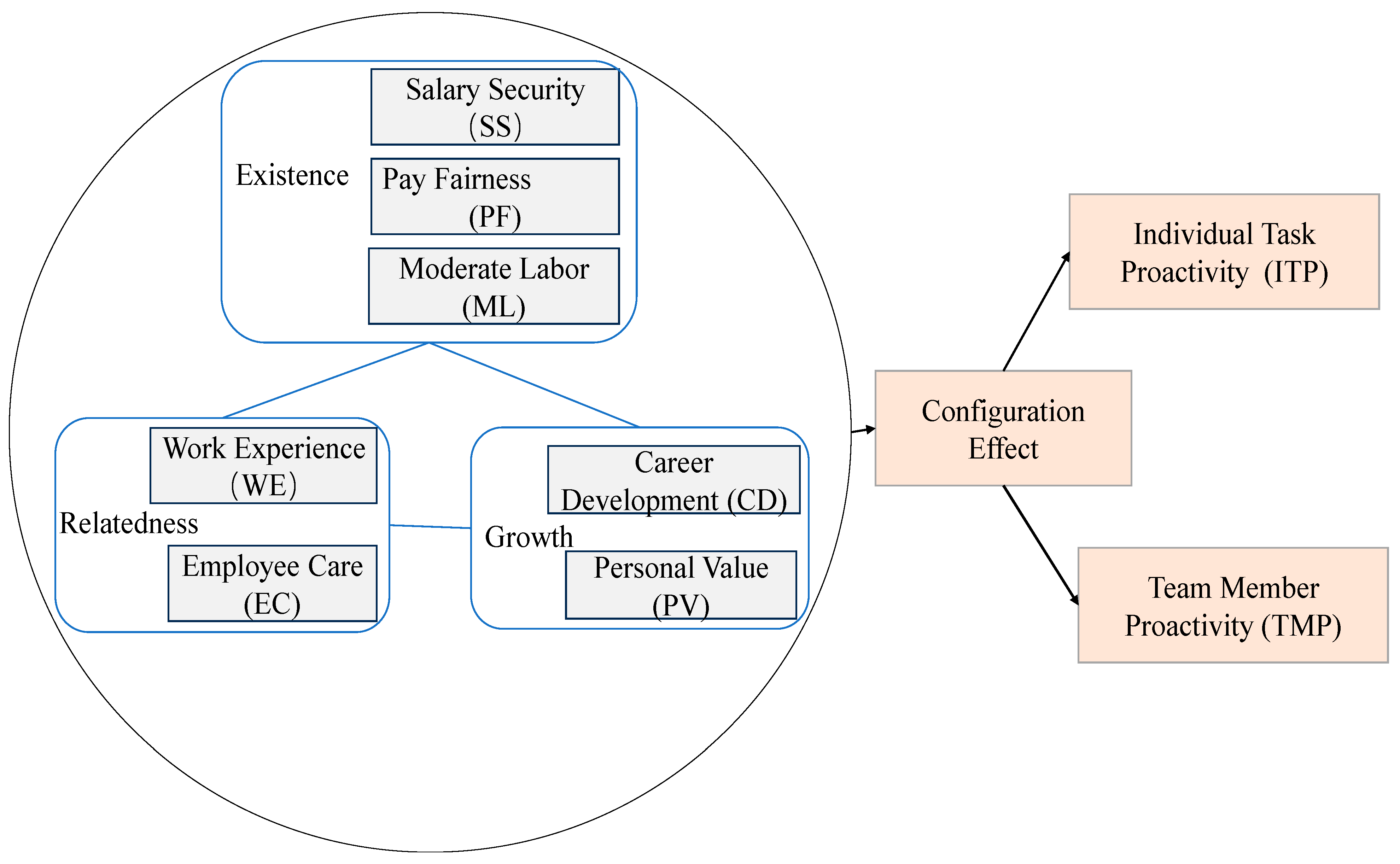

2.1.3. Model Construction

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Variable Measurement and Reliability and Validity Testing

3.3. Selection Method

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Variable Calibration

4.2. Necessity Analysis of Single Conditions

4.3. Construction of Truth Tables and Configuration Generation

4.4. Configuration Result Analysis

4.4.1. Analysis of Configuration Paths Leading to High Individual Task Proactivity

4.4.2. Analysis of Configuration Paths Leading to High Team-Member Proactivity

4.5. Robustness Test

5. Conclusions and Implications

5.1. Conclusions

- (1)

- There is no single reward tool that acts as a necessary condition for generating high proactive behavior; different reward tools need to work in synergy to create effective motivation.

- (2)

- Three patterns drive employees to demonstrate high individual task proactivity, namely: the “Dual-Drive Salary Security and Moderate Labor Dominant” pattern, the “Moderate Labor Dominant” structure, and the “Salary Security Dominant” structure. Two patterns drive employees to demonstrate high team-member proactivity, namely the “Employee Care Dominant High-Investment” pattern and the “Pay Fairness Dominant High-Investment” pattern.

- (3)

- There are significant differences in the motivational factors for individual task proactivity and team-member proactivity. Salary security and moderate labor are key to motivating individual task proactivity, while motivating team-member proactivity requires not only the synergy of multiple reward tools but also the indispensable core practices of employee care and pay fairness.

- (4)

- Work experience, based on good colleague relationships, plays an important role in promoting both forms of proactivity.

- (5)

- A substitution effect exists both within and between the demand elements of total rewards that drive proactive behavior. The study further reveals that career development and personal value exhibit a substitution effect when driving high individual task proactivity, proving that both external growth paths (such as job promotions) and intrinsic growth paths (such as task significance) can yield equivalent outcomes. It also confirms that within the same need (e.g., Growth needs), compensation and incentive tools are interchangeable. The substitution effect between compensation security and career development in driving high team-member proactivity aligns with the dynamic adjustment theory of the needs hierarchy.

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

5.3. Managerial Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Garrido-Moreno, A.; Martín-Rojas, R.; García-Morales, V.J. The key role of innovation and organizational resilience in improving business performance: A mixed-methods approach. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2024, 77, 102777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Yang, D.; Sun, W.; Xu, L. Building a Resilient Organization Through Informal Networks: Examining the Role of Individual, Structural, and Attitudinal Factors in Advice-Seeking Tie Formation. Systems 2025, 13, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyfoudi, M.; Kwon, B.; Wilkinson, A. Employee voice in times of crisis: A conceptual framework exploring the role of Human Resource practices and Human Resource system strength. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2024, 63, 537–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Guo, M.; Han, Z.; Gavurova, B.; Bresciani, S.; Wang, T. Effects of digital orientation on organizational resilience: A dynamic capabilities perspective. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2024, 35, 268–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, C.; Van Gils, S.; Van Quaquebeke, N.; Grover, S.L.; Eckloff, T. Proactivity at work: The roles of respectful leadership and leader group prototypicality. J. Pers. Psychol. 2021, 20, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulmer, I.S.; Li, J. Compensation, Benefits, and Total Rewards: A Bird’s-Eye (Re)View. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2022, 9, 147–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cafaro, D. The WorldatWork Handbook of Total Rewards: A Comprehensive Guide to Compensation, Benefits, HR & Employee Engagement; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; p. 388. Available online: https://www.wiley.com/en-hk/The+WorldatWork+Handbook+of+Total+Rewards%3A+A+Comprehensive+Guide+to+Compensation%2C+Benefits%2C+HR+&+Employee+Engagement%2C+2nd+Edition-p-9781119682448 (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Zhao, S.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, Y. Human Resource Management in a Century: Evolution and Development. Foreign Econ. Manag. 2019, 41, 50–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandhu, D.; Mohan, M.M.; Nittala, N.A.P.; Jadhav, P.; Bhadauria, A.; Saxena, K.K. Theories of motivation: A comprehensive analysis of human behavior drivers. Acta Psychol. 2024, 244, 104177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Zhao, H. The Impact of Digital Transformation on Organizational Resilience: The Role of Innovation Capability and Agile Response. Systems 2025, 13, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sima, V.; Gheorghe, I.G.; Subić, J.; Nancu, D. Influences of the Industry 4.0 Revolution on the Human Capital Development and Consumer Behavior: A Systematic Review. Sustainablity 2020, 12, 4035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, R.P.; Bishop, N.C.; Taylor, I.M. The Relationship Between Multidimensional Motivation and Endocrine-Related Responses: A Systematic Review. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2021, 16, 614–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Yang, J.; Faye, B. Addressing the “Lying Flat” Challenge in China: Incentive Mechanisms for New-Generation Employees through a Moderated Mediation Model. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tessema, S.A.; Yang, S.; Chen, C. The Effect of Human Resource Analytics on Organizational Performance: Insights from Ethiopia. Systems 2025, 13, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, M.A.; Neal, A.; Parker, S.K. A New Model of Work Role Performance: Positive Behavior in Uncertain and Interdependent Contexts. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; El Baroudi, S.; Khapova, S.N.; Xu, B.; Kraimer, M.L. Career calling and team member proactivity: The roles of living out a calling and mentoring. Appl. Psychol. 2022, 71, 587–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.K.; Wang, Y.; Liao, J. When Is Proactivity Wise? A Review of Factors That Influence the Individual Outcomes of Proactive Behavior. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2019, 6, 221–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnolds, C.A.; Boshoff, C. Compensation, esteem valence and job performance: An empirical assessment of Alderfer’s ERG theory. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2002, 13, 697–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twemlow, M.; Tims, M.; Khapova, S.N. A process model of peer reactions to team member proactivity. Hum. Relations 2023, 76, 1317–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carraro, M.; Furlan, A.; Netland, T. Unlocking team performance: How shared mental models drive proactive problem-solving. Hum. Relat. 2024, 78, 407–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potrich, L.N.; Selig, P.M.; Matos, F.; Giugliani, E. Organisational Resilience in the Digital Age: Management Strategies and Practices. In Resilience in a Digital Age; Contributions to Management Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segarra-Ciprés, M.; Escrig-Tena, A.; García-Juan, B. Employees’ proactive behavior and innovation performance. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2019, 22, 866–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Duan, X.; Chu, X.; Qiu, Y. Total reward satisfaction profiles and work performance: A person-centered approach. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Oljaca, M.; Firdousi, S.F.; Akram, U. Managing Diversity in the Chinese Organizational Context: The Impact of Workforce Diversity Management on Employee Job Performance. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 733429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan Chunping, J.Y.A.S. Literature Review and Prospects of Total Rewards: Factor Evolution, Theoretical Basis and Research Perspectives. 2019. Available online: https://qks.sufe.edu.cn/mv_html/j00002/201905/dfd98716-285f-4400-93b9-d330f4ffc3c1_WEB.htm (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- McClean, E.; Collins, C.J. Expanding the concept of fit in strategic human resource management: An examination of the relationship between human resource practices and charismatic leadership on organizational outcomes. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2019, 58, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.C.; Hsu, C.L. Understanding Users’ Urge to Post Online Reviews: A Study Based on Existence, Relatedness, and Growth Theory. SAGE Open 2022, 12, 21582440221129851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Impact of Work-Life Programs on Firm Productivity. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/a/bla/stratm/v21y2000i12p1225-1237.html (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Mowbray, P.K.; Gu, J.; Chen, Z.; Tse, H.H.M.; Wilkinson, A. How do tangible and intangible rewards encourage employee voice? The perspective of dual proactive motivational pathways. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2024, 35, 2569–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brav, A.; Andersson, K.; Lantz, A. Group initiative and self-organizational activities in industrial work groups. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2009, 18, 347–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, A.K.; Kauffeld, S. Proactive verbal behavior in team meetings: Effects of supportive and critical responses on satisfaction and performance. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 20640–20654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.Y.; Wu, C.H.; Bartram, A.; Parker, S.K.; Lee, C. Is leader proactivity enough: Importance of leader competency in shaping team role breadth efficacy and proactive performance. J. Vocat. Behav. 2023, 143, 103865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wei, H.; Xin, H.; Cheng, P. Task conflict and team creativity: The role of team mindfulness, experiencing tensions, and information elaboration. Asia Pacific J. Manag. 2022, 39, 1367–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Parker, S.K.; Chen, Z.; Lam, W. How does the social context fuel the proactive fire? A mult-level review and theoretical synthesis. J. Organ. Behav. 2019, 40, 209–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahlert, A.; Grote, G. “Why should I care?”: Understanding technology developers’ design mindsets in relation to prospective work design. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2024, 33, 230–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhart, B.; Fang, M. Pay, Intrinsic Motivation, Extrinsic Motivation, Performance, and Creativity in the Workplace: Revisiting Long-Held Beliefs. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2015, 2, 489–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belschak, F.D.; Den Hartog, D.N.D. Pro-self, prosocial, and pro-organizational foci of proactive behaviour: Differential antecedents and consequences. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 475–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, S.; Chen, K. Configuration Theory and QCA Methods from a Complex Dynamic Perspective: Research Progress and Future Directions. 2021. Available online: https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/periodical/Ch9QZXJpb2RpY2FsQ0hJTmV3UzIwMjUwMTE2MTYzNjE0Eg1nbHNqMjAyMTAzMDEyGghtZ2x3cHQ3Nw%253D%253D (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Fischer, C.; Malycha, C.P.; Schafmann, E. The influence of intrinsic motivation and synergistic extrinsic motivators on creativity and innovation. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 416995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Long, J.; von Schaewen, A.M.E. How Does Digital Transformation Improve Organizational Resilience?—Findings from PLS-SEM and fsQCA. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faye, B.; Du, G.; Li, Y.; Li, Q.; Diène, J.C.; Mbaye, E.; Kama, R. Connecting the farmers’ knowledge and behaviors: Detection of influencing factors to sustainable cultivated land protection in Thiès Region, Senegal. J. Rural Stud. 2025, 116, 103634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faye, B.; Du, G.; Li, Q.; Véronique, H.; Faye, M.T.; Coleee Diéne, J.; Mbaye, E.; Seck, H.M. Lessons Learnt from the Influencing Factors of Forested Areas’ Vulnerability Under Climatic Change and Human Pressure in Arid Areas: A Case Study of the Thiès Region, Senegal. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woehr, D.J. Understanding Frame-of-Reference Training: The Impact of Training on the Recall of Performance Information. J. Appl. Psychol. 1994, 79, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohi Ud Din, Q.; Zhang, L. Unveiling the Mechanisms through Which Leader Integrity Shapes Ethical Leadership Behavior: Theory of Planned Behavior Perspective. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, S.; Cambré, B. Designers’ road(s) to success: Balancing exploration and exploitation. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 115, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, I.O.; Woodside, A.G. Fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA): Guidelines for research practice in Information Systems and marketing. Int. J. Inf. Manage. 2021, 58, 102310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W.-H.; Tortia, E.C.; Aldieri, L.; Du, H.; Teng, Y.; Ma, Z.; Guo, X. Value Creation in Platform Enterprises: A Fuzzy-Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis. Sustainablity 2022, 14, 5331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiss, P.C. Building Better Causal Theories: A Fuzzy Set Approach to Typologies in Organization Research. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 393–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Liu, Q.; Cheng, J. What Kind of Business Environment Ecosystem Generates High Entrepreneurial Activity in Cities?—An Analysis Based on Institutional Configuration. J. Manag. World 2020, 36, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, N.; Zhen, D.; Guan, J. Work values of Chinese generational cohorts. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2024, 56, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, J.L.; Bureau, J.; Guay, F.; Chong, J.X.Y.; Ryan, R.M. Student Motivation and Associated Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis From Self-Determination Theory. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2021, 16, 1300–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Tahir, S.H.; Khan, K.B.; Sajid, M.A.; Safdar, M.A. Beyond regression: Unpacking research of human complex systems with qualitative comparative analysis. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition Variables | Existence | SS | 0.747 | 0.807 | 0.515 |

| PF | 0.896 | 0.841 | 0.516 | ||

| ML | 0.931 | 0.919 | 0.655 | ||

| Relatedness | WE | 0.897 | 0.873 | 0.697 | |

| EC | 0.910 | 0.828 | 0.503 | ||

| Growth | CD | 0.892 | 0.847 | 0.513 | |

| PV | 0.845 | 0.866 | 0.527 | ||

| Outcome Variables | ITP | 0.864 | 0.866 | 0.683 | |

| TMP | 0.825 | 0.771 | 0.529 | ||

| Set | Mean | Standard Deviation | Maximum Value | Minimum Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SS | 4.436 | 0.821 | 6.000 | 1.333 |

| PF | 3.988 | 0.913 | 5.800 | 1.000 |

| ML | 4.437 | 0.998 | 6.000 | 1.000 |

| WE | 4.762 | 0.911 | 6.000 | 1.333 |

| EC | 4.136 | 0.913 | 6.000 | 1.600 |

| CD | 4.225 | 0.820 | 6.000 | 1.833 |

| PV | 4.415 | 0.723 | 6.000 | 1.750 |

| ITP | 4.394 | 0.793 | 6.000 | 1.000 |

| TMP | 4.221 | 0.807 | 6.000 | 1.000 |

| Condition Variables | Outcome Variables | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High ITP | High TMP | |||

| Consistency | Coverage | Consistency | Coverage | |

| SS | 0.856 | 0.833 | 0.891 | 0.812 |

| ~SS | 0.509 | 0.889 | 0.508 | 0.831 |

| PF | 0.764 | 0.848 | 0.814 | 0.845 |

| ~PF | 0.596 | 0.855 | 0.586 | 0.785 |

| ML | 0.835 | 0.812 | 0.857 | 0.780 |

| ~ML | 0.488 | 0.853 | 0.489 | 0.799 |

| WE | 0.887 | 0.776 | 0.893 | 0.749 |

| ~WE | 0.409 | 0.896 | 0.421 | 0.862 |

| EC | 0.662 | 0.913 | 0.707 | 0.912 |

| ~EC | 0.715 | 0.817 | 0.709 | 0.758 |

| CD | 0.808 | 0.855 | 0.847 | 0.838 |

| ~CD | 0.562 | 0.860 | 0.567 | 0.811 |

| PV | 0.849 | 0.834 | 0.888 | 0.816 |

| ~PV | 0.524 | 0.900 | 0.528 | 0.849 |

| Conditions | Accuracy | Ceiling Zone | Range (ITP/TMP) | Effect Size (d) | p Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITP | TMP | ITP | TMP | ITP | TMP | ITP | TMP | ||

| SS | 99.00% | 99.00% | 0.031 | 0.036 | 0.690 | 0.045 | 0.052 | 0.224 | 0.304 |

| PF | 97.10% | 99.00% | 0.049 | 0.038 | 0.720 | 0.067 | 0.052 | 0.015 | 0.180 |

| ML | 97.60% | 99.50% | 0.049 | 0.034 | 0.750 | 0.065 | 0.045 | 0.076 | 0.389 |

| WE | 98.60% | 99.00% | 0.067 | 0.072 | 0.740 | 0.090 | 0.098 | 0.118 | 0.197 |

| EC | 99.00% | 97.60% | 0.021 | 0.048 | 0.740 | 0.029 | 0.065 | 0.236 | 0.026 |

| CD | 98.60% | 99.00% | 0.044 | 0.033 | 0.710 | 0.063 | 0.046 | 0.017 | 0.181 |

| PV | 100% | 100% | 0.011 | 0.056 | 0.710 | 0.016 | 0.079 | 0.803 | 0.286 |

| ITP | SS | PF | ML | WE | EC | CD | PV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN |

| 10 | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN |

| 20 | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN |

| 30 | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN |

| 40 | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN |

| 50 | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | 0.4 |

| 60 | NN | NN | 4.8 | 2.3 | 1.7 | NN | 1.5 |

| 70 | 0.1 | 7.6 | 10.3 | 12.4 | 4.4 | 7.6 | 2.6 |

| 80 | 10.1 | 16.8 | 15.9 | 22.5 | 7.0 | 15.6 | 3.7 |

| 90 | 20.1 | 26.0 | 21.4 | 32.6 | 9.7 | 23.6 | 4.8 |

| 100 | 30.1 | 35.2 | 26.9 | 42.8 | 12.4 | 31.6 | 5.9 |

| TMP | SS | PF | ML | WE | EC | CD | PV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN |

| 10 | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN |

| 20 | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN |

| 30 | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN |

| 40 | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN |

| 50 | NN | NN | NN | NN | 2.0 | NN | 2.0 |

| 60 | NN | 1.7 | NN | 2.9 | 6.4 | NN | 7.5 |

| 70 | NN | 7.3 | NN | 13.6 | 10.8 | NN | 13.0 |

| 80 | 10.5 | 12.9 | 7.8 | 24.4 | 15.2 | 9.1 | 18.5 |

| 90 | 23.9 | 18.6 | 21.5 | 35.2 | 19.5 | 21.5 | 24.0 |

| 100 | 37.3 | 24.2 | 35.2 | 45.9 | 23.9 | 33.9 | 29.5 |

| Conditions | ITP | TMP | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | H1b | H1c | H1d | H2 | H3 | S1 | S2a | S2b | ||

| Existence | SS | ⬤ | ⬤ | ⬤ | ⬤ | ⬤ | • | • | ||

| PF | ⊗ | ⊗ | • | ⊗ | ⬤ | ⬤ | ||||

| ML | ⬤ | ⬤ | ⬤ | ⬤ | ⬤ | ⊗ | • | • | • | |

| Relatedness | WE | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | |

| EC | ⊗ | ⊗ | ⊗ | ⊗ | ⊗ | ⬤ | ⊗ | ⊗ | ||

| Growth | CD | • | • | ⊗ | • | ⊗ | • | • | ||

| PV | • | • | • | • | ⊗ | • | • | • | ||

| Raw Coverage | 0.678 | 0.538 | 0.424 | 0.397 | 0.497 | 0.372 | 0.648 | 0.526 | 0.531 | |

| Unique Coverage | 0.164 | 0.003 | 0.005 | 0.011 | 0.007 | 0.028 | 0.177 | 0.006 | 0.011 | |

| Consistency | 0.929 | 0.949 | 0.972 | 0.963 | 0.972 | 0.973 | 0.958 | 0.961 | 0.961 | |

| Overall Consistency of the Solution | 0.916 | 0.942 | ||||||||

| Overall Coverage of the Solution | 0.754 | 0.713 | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, J.; Yang, J.; Faye, B. Synergistic Rewards for Proactive Behaviors: A Study on the Differentiated Incentive Mechanism for a New Generation of Knowledge Employees Using Mixed fsQCA and NCA Analysis. Systems 2025, 13, 500. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13070500

Zhou J, Yang J, Faye B. Synergistic Rewards for Proactive Behaviors: A Study on the Differentiated Incentive Mechanism for a New Generation of Knowledge Employees Using Mixed fsQCA and NCA Analysis. Systems. 2025; 13(7):500. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13070500

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Jie, Junqing Yang, and Bonoua Faye. 2025. "Synergistic Rewards for Proactive Behaviors: A Study on the Differentiated Incentive Mechanism for a New Generation of Knowledge Employees Using Mixed fsQCA and NCA Analysis" Systems 13, no. 7: 500. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13070500

APA StyleZhou, J., Yang, J., & Faye, B. (2025). Synergistic Rewards for Proactive Behaviors: A Study on the Differentiated Incentive Mechanism for a New Generation of Knowledge Employees Using Mixed fsQCA and NCA Analysis. Systems, 13(7), 500. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13070500