Spatiotemporal Evolution of and Regional Differences in Consumer Disputes in the Tourism System: Empirical Evidence from the Yangtze River Economic Belt, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

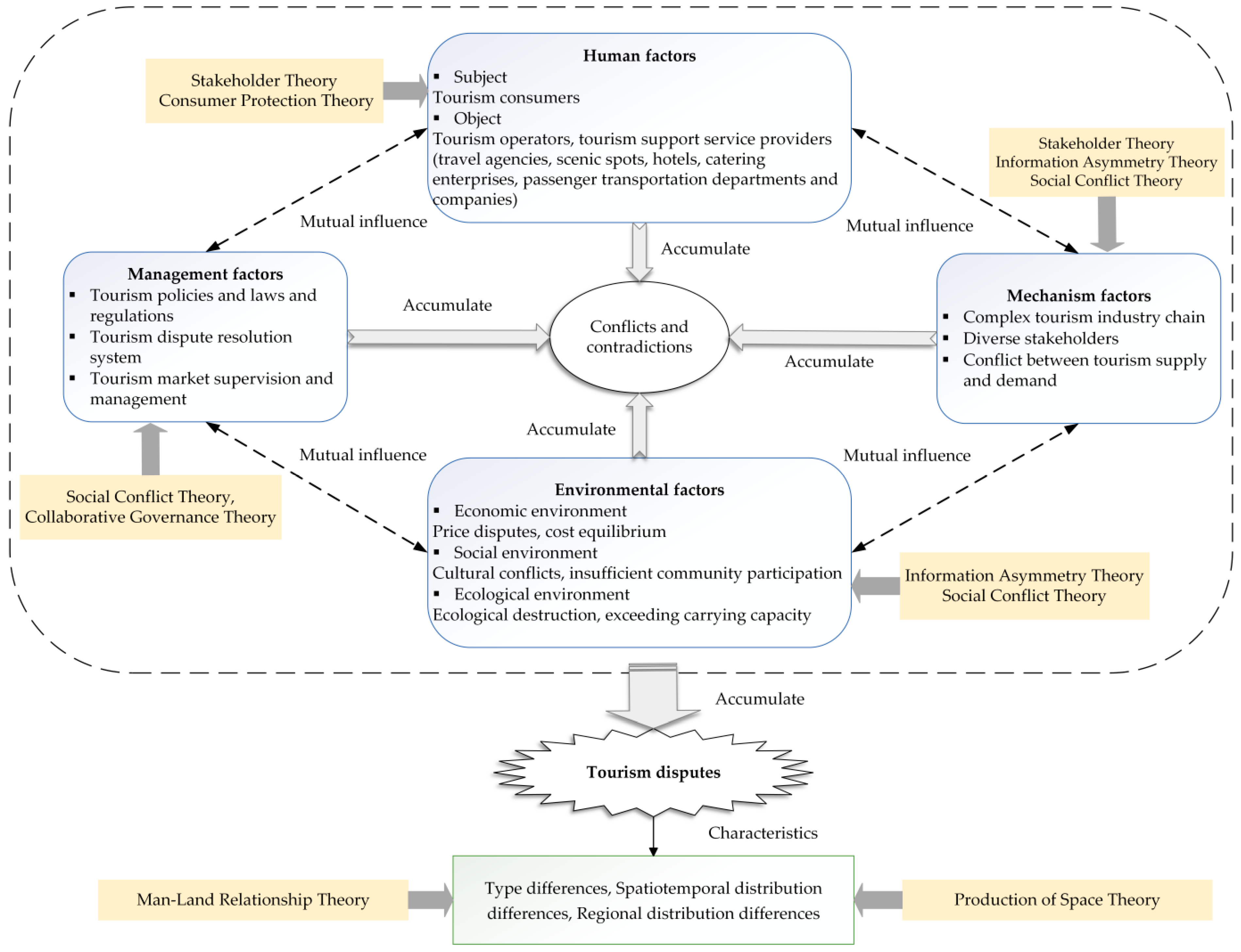

2. Theoretical Framework and Research Logic of Tourism Disputes

2.1. Mechanisms and Theoretical Framework of Tourism Disputes

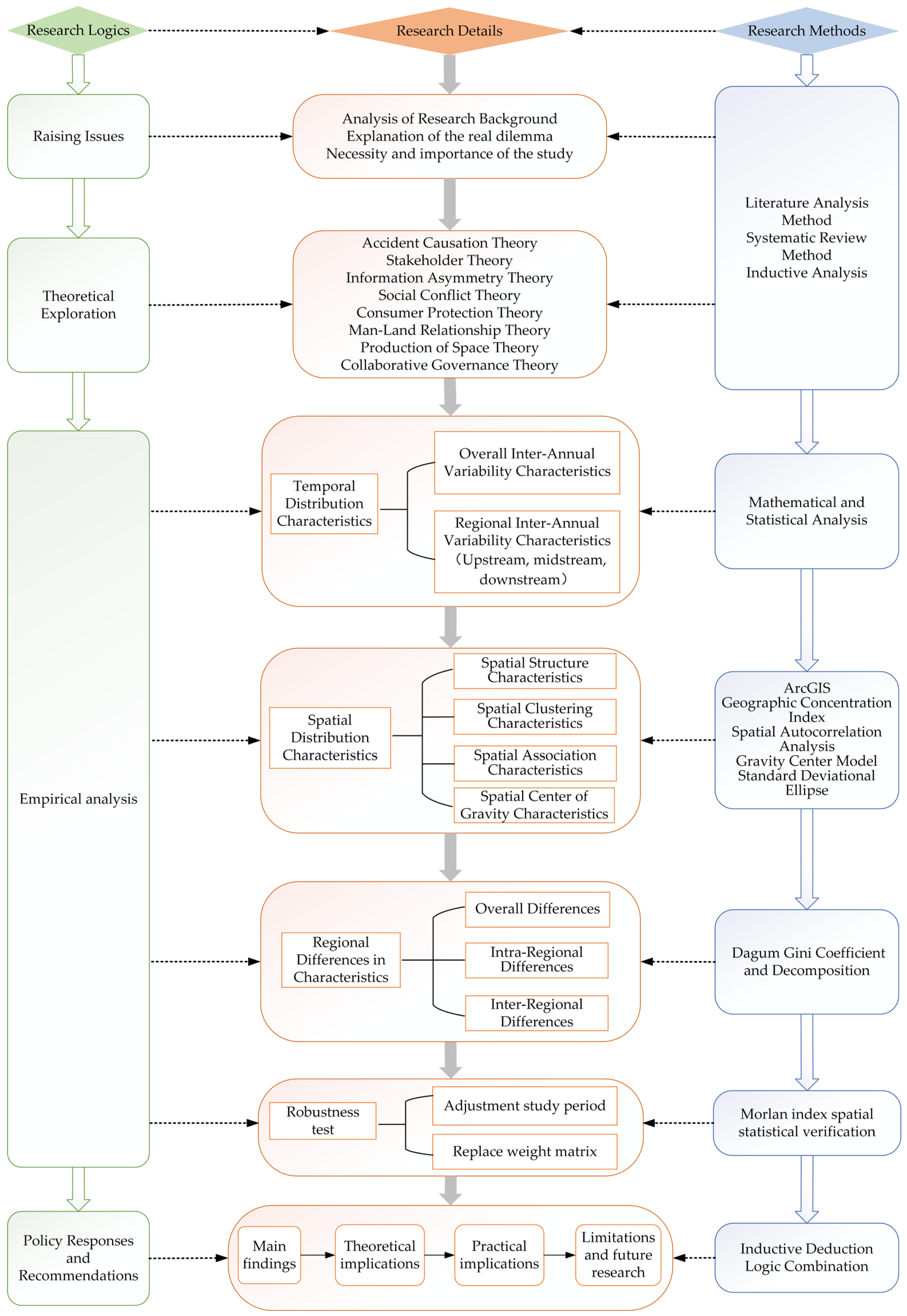

2.2. Research Ideas and Logic

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Methods

3.2.1. Geographic Concentration Index

3.2.2. Spatial Autocorrelation Analysis

3.2.3. Gravity Center Model

3.2.4. Standard Deviational Ellipse

3.2.5. Dagum Gini Coefficient and Decomposition

3.3. Data Sources

4. Results

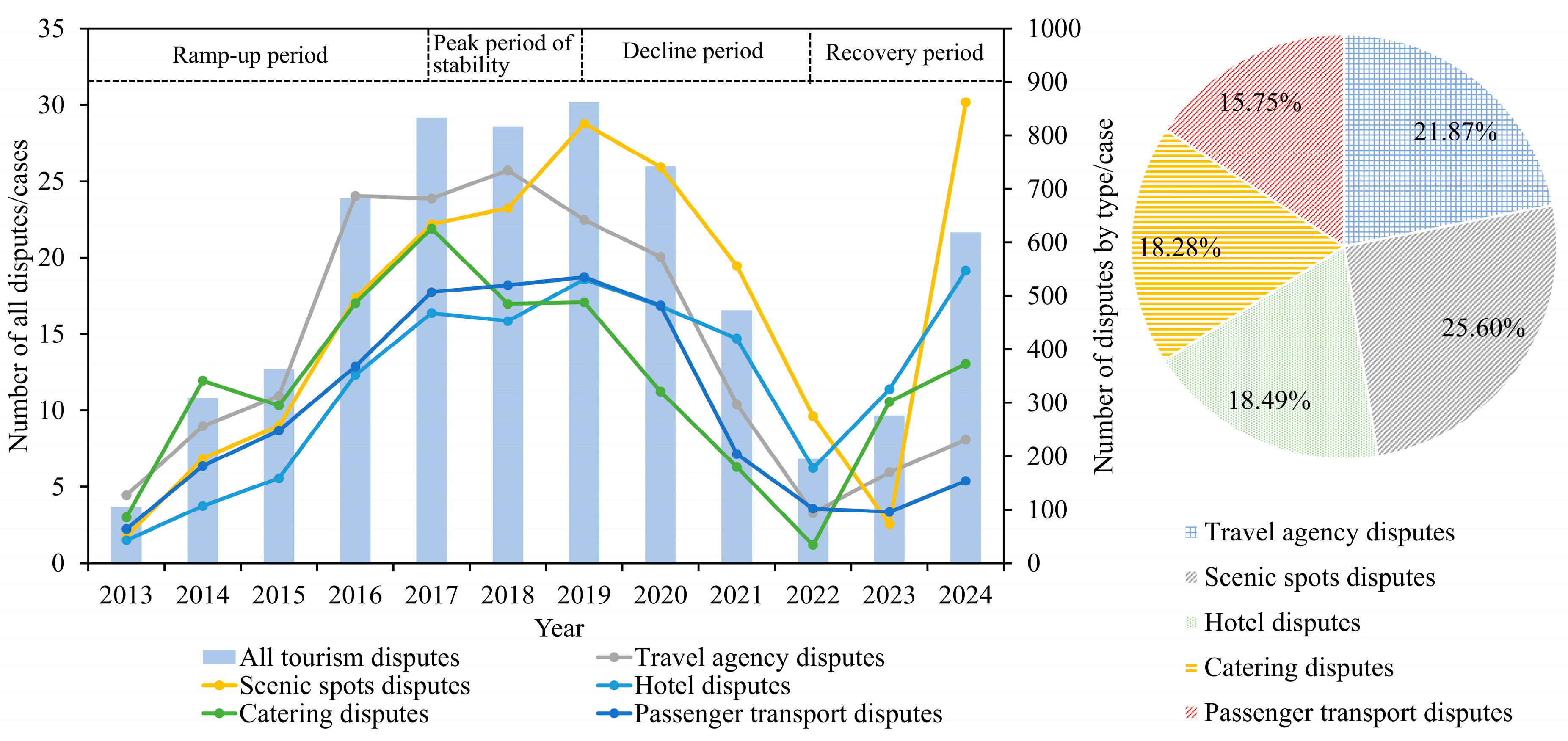

4.1. Temporal Distribution Characteristics

4.1.1. Overall Inter-Annual Variability Characteristics

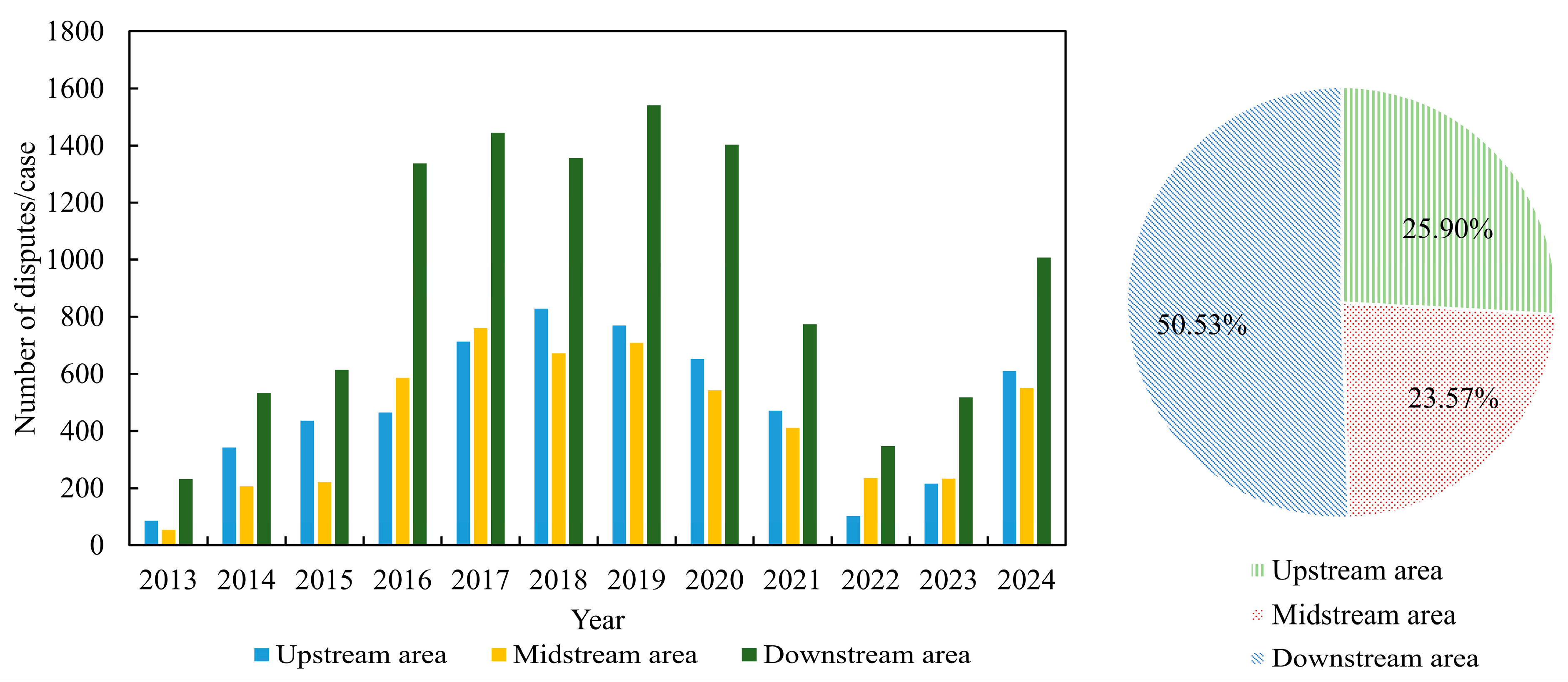

4.1.2. Regional Inter-Annual Variability Characteristics

4.2. Spatial Distribution Characteristics

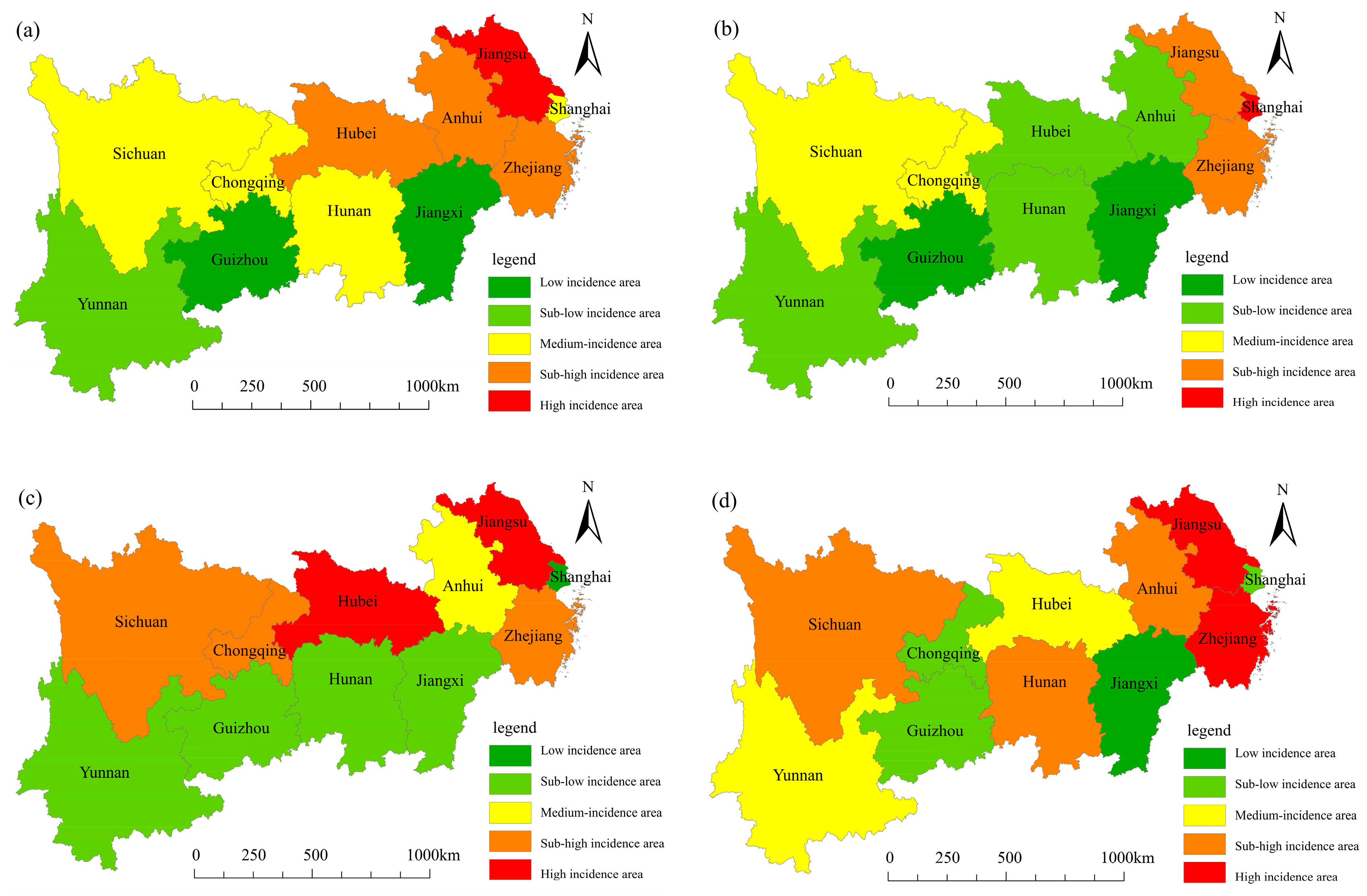

4.2.1. Spatial Structure Characteristics

4.2.2. Spatial Clustering Characteristics

4.2.3. Spatial Association Characteristics

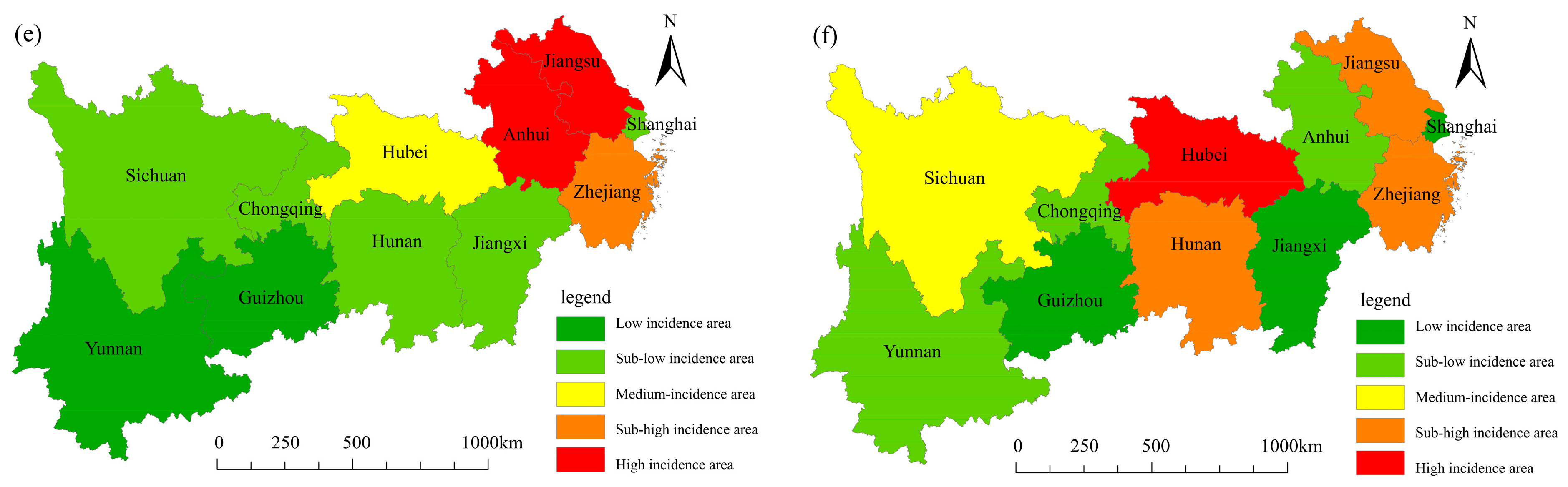

4.2.4. Spatial Gravity Center Characteristics

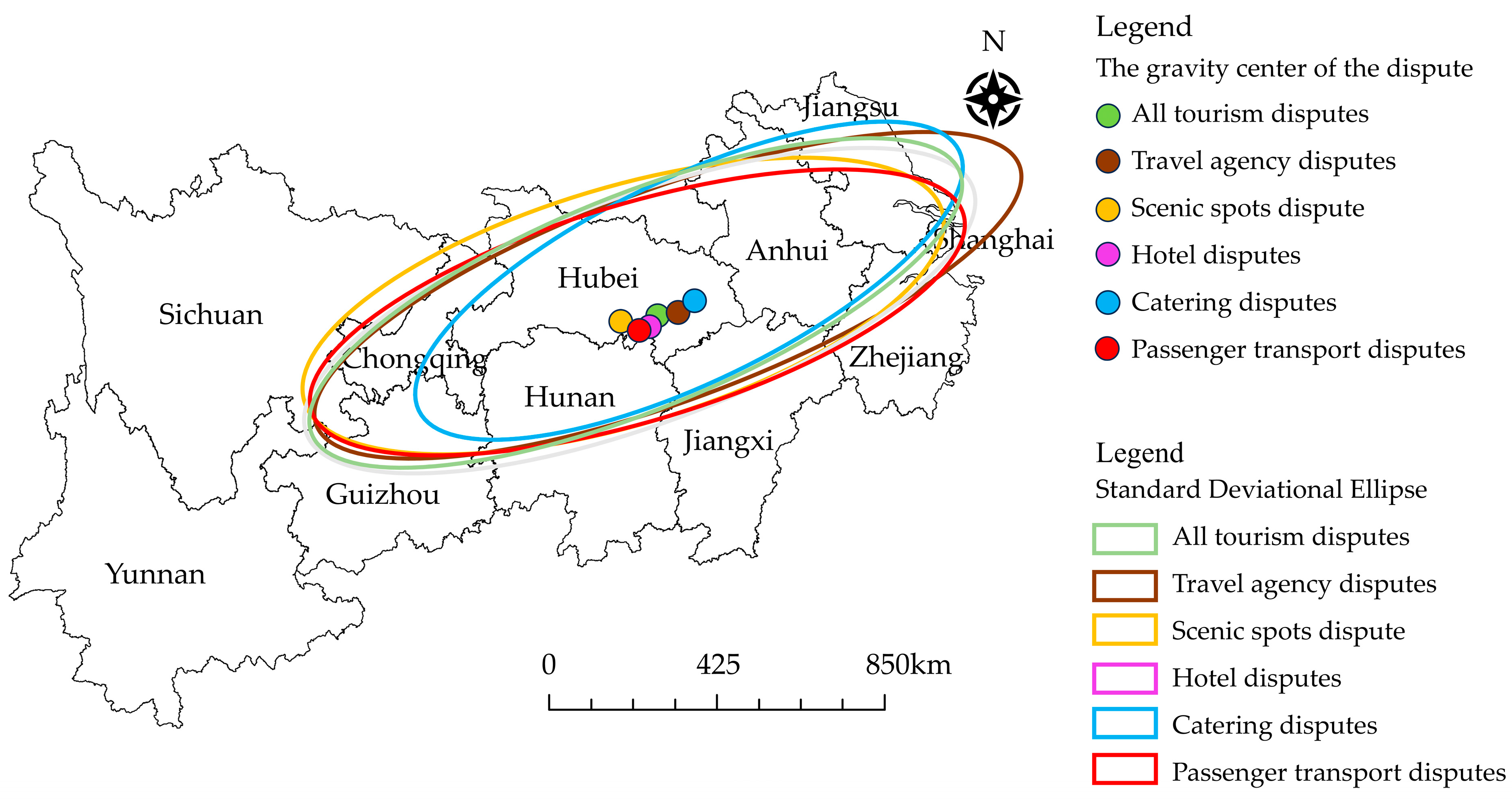

4.3. Regional Differences in Characteristics

4.3.1. Overall Differences

4.3.2. Intra-Regional Differences

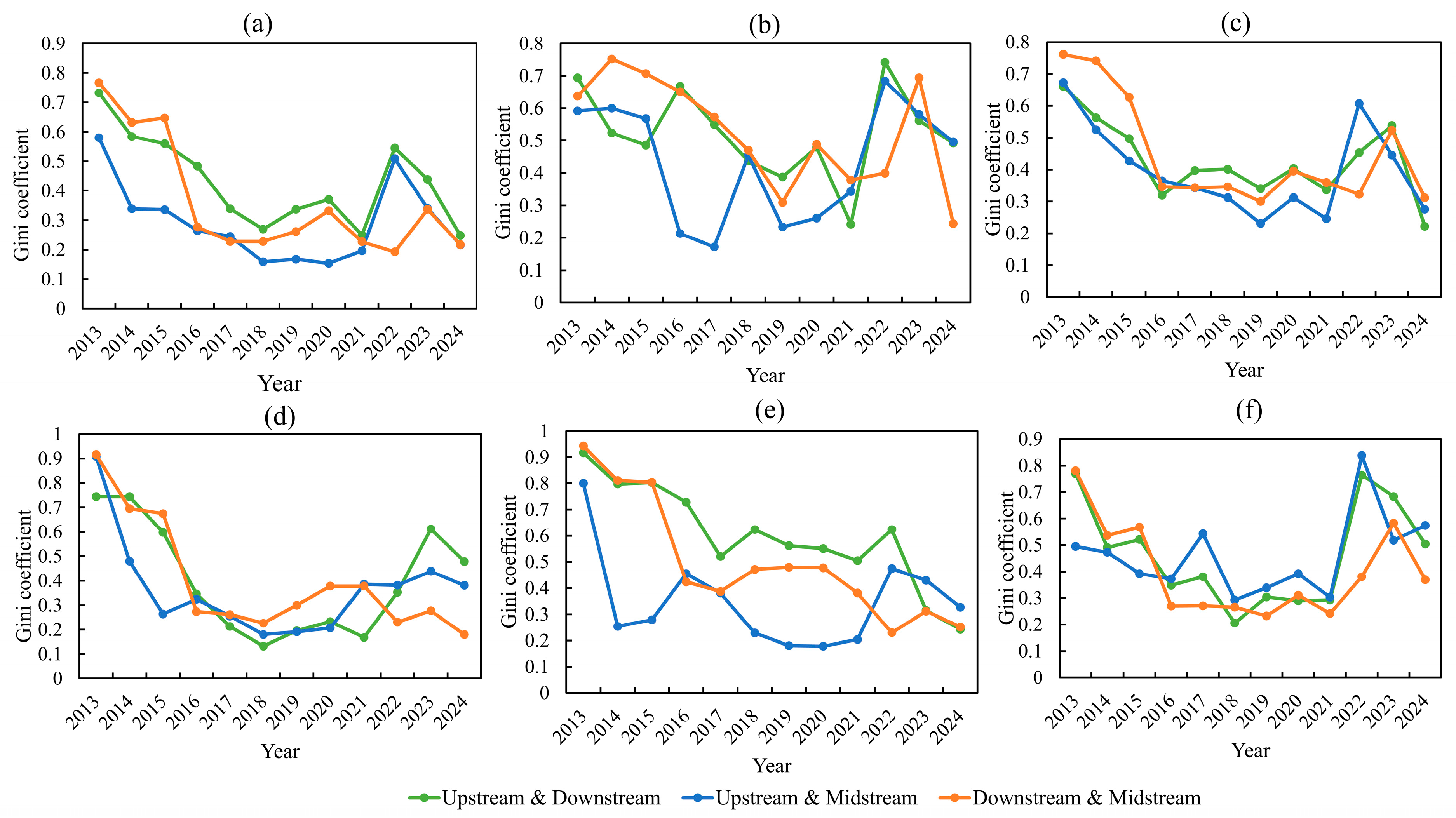

4.3.3. Inter-Regional Differences

4.4. Robustness Test

5. Discussion

5.1. Main Findings

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Practical Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- Xu, Y.Y.; McGehee, N.G. Tour guides under zero-fare mode: Evidence from China. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 1088–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X. Challenges and potential improvements in the policy and regulatory framework for sustainable tourism planning in China: The case of Shanxi Province. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 455–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, S.O.; Tumer, M.; Ozturen, A.; Kilic, H. Mediating role of legal services in tourism development: A necessity for sustainable tourism destinations. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 2866–2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoulidis, B.; Diaz, D.; Crotto, F.; Rancati, E. Exploring corporate social responsibility and financial performance through stakeholder theory in the tourism industries. Tour. Manag. 2017, 62, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.M.; Zhu, C.S.; Fong, L.H.N. Exploring Residents’ Perceptions and Attitudes towards Sustainable Tourism Development in Traditional Villages: The Lens of Stakeholder Theory. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.S.; Sharma, A.; Pan, B.; Quadri-Felitti, D. Information asymmetry in the innovation adoption decision of tourism and hospitality SMEs in emerging markets: A mixed-method analysis. Tour. Manag. 2023, 99, 104793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.D.; Li, H. Information Asymmetry in Tourism Market: The Bilateral Effects of ESG Practices on Firm Profitability. J. Travel Res. 2025, 00472875251332950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedelea, A.; Balan, A. E-TOURISM AND TOURISM SERVICES CONSUMER PROTECTION. Amfiteatru Econ. 2010, 12, 492–503. [Google Scholar]

- Petrovic, J.; Milicevic, S. Consumer Protection as a Factor of Destination Competitiveness in the European Union. Amfiteatru Econ. 2017, 19, 432–446. [Google Scholar]

- Zmyslony, P.; Kowalczyk-Aniol, J.; Dembinska, M. Deconstructing the Overtourism-Related Social Conflicts. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.B.; Xie, A.L.; Cheng, K. Research on Spatio-Temporal Evolution Characteristics and Driving Factors of Tourism Destination Environmental System Resilience in Yangtze River Economic Belt. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2024, 33, 5429–5441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Bao, J.; Huang, J.F.; Zhu, Q.J.; Mu, C.L.; Chu, X.L.; Xu, Y.; Zha, X.L. Recent research progress and prospects in tourism geography of China. J. Geogr. Sci. 2016, 26, 1197–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Zhu, C.G.; Pu, J.; Wen, B.; Si, W.T. Study on the Influence Mechanism of Intangible Cultural Heritage Distribution from Man-Land Relationship Perspective: A Case Study in Shandong Province. Land 2022, 11, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, F.; Moyle, B.D.; Bao, J.G.; Zhong, Y.D. The role of institutions in the production of space for tourism: National Forest Parks China. For. Policy Econ. 2016, 70, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulusjärvi, O. Towards just production of tourism space via dialogical everyday politics in destination communities. Environ. Plan. C-Politics Space 2020, 38, 751–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, G.H.; Yang, Q.Y. The spatial production of rural settlements as rural homestays in the context of rural revitalization: Evidence from a rural tourism experiment in a Chinese village. Land Use Policy 2023, 128, 106600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barandiarán, X.; Restrepo, N.; Luna, A. Collaborative governance in tourism: Lessons from Etorkizuna Eraikiz in the Basque Country, Spain. Tour. Rev. 2019, 74, 902–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valderrama, E.L.; Polanco, J.A.; Hernandez-Diaz, P.M. Does collaborative governance mediate rural tourism to achieve sustainable territory development? Evidence of stakeholders’ perceptions in Colombia. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 33, 493–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bichler, B.F.; Lösch, M. Collaborative Governance in Tourism: Empirical Insights into a Community-Oriented Destination. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.S.; Zhang, H.Y.; Luo, Y.; Li, Y.P. Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) measurement in the tourism and hospitality industry: Views from a developing country. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2024, 41, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, S.W.T.; Tung, V.W.S. Advocating Sustainable Tourism in China: A Transitory, Top-Down Stakeholder Engagement Perspective. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2025, 27, e70034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sontag, K.; Roux, F. Sporting and tourist activities: Legal aspects What legal framework for sports, leisure and tourism activities? Rev. Geogr. Alp.-J. Alp. Res. 2013, 101, 548–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Khater, M.; Ibrahim, O.; Sayed, M.N.E.; Faik, M. Legal frameworks for sustainable tourism: Balancing environmental conservation and economic development. Curr. Issues Tour. 2024, 27, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobe, S. The legal regime for private space tourism activities-An overview. Acta Astronaut. 2010, 66, 1593–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.F.; Chang, Y.; Pearce, P.L. China’s first Tourism Law: Representations of stakeholders’ responses. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2018, 16, 309–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrat, J.M.B. Quality of hotel service and consumer protection: A European contract law approach. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newlands, G.; Lutz, C. Fairness, legitimacy and the regulation of home-sharing platforms. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 3177–3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seta, M. Compulsory insurance for cruise vessels as a preparation for the next pandemic: Law of the sea perspective. Mar. Policy 2023, 152, 105586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y.Z.; Han, X.P. Research on consumers’ protection in advantageous operation of big data brokers. Clust. Comput.-J. Netw. Softw. Tools Appl. 2019, 22, S8387–S8400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.X.; Yao, Y.B.; Fan, D.X.F. Evaluating Tourism Market Regulation from Tourists’ Perspective: Scale Development and Validation. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 975–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; Wang, M. Tourism law, labor supply and corporate performance in tourism listed firms. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 68, 105971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.P.; Xu, H.G. The role of local government and the private sector in China’s tourism industry. Tour. Manag. 2014, 45, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randle, E.J.; Hoye, R. Stakeholder perception of regulating commercial tourism in Victorian National Parks, Australia. Tour. Manag. 2016, 54, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinica, V. Tourism on Curacao: Explaining the Shortage of Sustainability Legislation from Game Theory Perspective. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2012, 14, 161–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asongu, S.A.; Rahman, M.; Nnanna, J. Law, political stability, tourism management and economic development in sub-Saharan Africa. Curr. Issues Tour. 2023, 26, 2678–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, N.; Kar, S. Relating rule of law and budgetary allocation for tourism: Does per capita income growth make a difference for Indian states? Econ. Model. 2018, 71, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozgor, G.; Lau, C.K.M.; Zeng, Y.; Lin, Z.B. The effectiveness of the legal system and inbound tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 76, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayar, Y.; Gavriletea, M.D.; Remeikiene, R. Impact of the rule of law, corruption and terrorism on tourism: Empirical evidence from Mediterranean countries. Oeconomia Copernic. 2023, 14, 1009–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.K.; Zou, S.J.; Zhao, Y.; He, Q.S.; Zhang, M.M. Research on the Manifestation and Formation Mechanism of New Characteristics of Land Disputes: Evidence from the Yangtze River Economic Belt, China. Land 2024, 13, 1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Chen, W.X.; Wu, D.; Zheng, L.; Li, J.F. Spatiotemporal evolution and influencing factors of tourism development efficiency in the Yangtze River Economic Belt, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 379, 134722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waligo, V.M.; Clarke, J.; Hawkins, R. Implementing sustainable tourism: A multi-stakeholder involvement management framework. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 342–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, A.; Pearson, L.J. Examining stakeholder group specificity: An innovative sustainable tourism approach. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 8, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuemei, L.; Wang, F.; Huili, C.; Jingwen, T. Development of an Indicator System for Evaluating Risks in Trekking Tourism. Leis. Sci. 2024, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.Y.; Li, D.D. Spatial Distribution Characteristics of Fringe Villages of Archipelagic City: A Case Study of Zhoushan. J. Coast. Res. 2020, 103, 469–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Jiang, X.M.; Xie, L.; Zhang, L.F.; He, Z.H. Study on the Spatiotemporal Differentiation of Traditional Villages and the Factors Influencing Tourism Responsiveness: A Case of Three Provinces and One Municipality in the Yangtze River Delta Region of China. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2025, 34, 1771–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.X.; Lv, X.Y.; Tian, Y.X.; Li, Z.; Xue, J.Y.; Chen, Y.L. A study on the spatial differences between the tourism network attention and tourism flow in Shanghai, China. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.D.; Liu, J.M.; Zhang, S.Y.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, X. Spatial pattern and micro-location rules of tourism businesses in historic towns: A case study of Pingyao, China. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2022, 25, 100721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.Y.; Wang, D.F. Regional differences, dynamic evolution, and driving factors of tourism development in Chinese coastal cities. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2022, 226, 106262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.Y. The historical evolution of China’s tourism development policies (1949-2013)-A quantitative research approach. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Y.; Feng, X.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, Z.B. Perceived tourism implicit conflict among community residents and its spatial variation. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | All Travel Disputes | Travel Agency Disputes | Scenic Spots Disputes | Hotel Disputes | Catering Disputes | Passenger Transport Disputes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 43.85 | 58.59 | 41.59 | 34.09 | 36.76 | 48.21 |

| 2014 | 43.96 | 48.64 | 41.01 | 31.45 | 42.56 | 56.14 |

| 2015 | 44.44 | 49.61 | 44.16 | 35.36 | 44.95 | 48.16 |

| 2016 | 44.39 | 53.63 | 39.25 | 38.39 | 45.57 | 45.10 |

| 2017 | 44.61 | 48.35 | 41.69 | 40.05 | 46.62 | 46.33 |

| 2018 | 44.52 | 50.72 | 42.66 | 39.82 | 48.21 | 41.20 |

| 2019 | 44.51 | 46.12 | 42.10 | 41.95 | 52.19 | 40.21 |

| 2020 | 44.32 | 46.96 | 43.07 | 43.03 | 53.41 | 35.15 |

| 2021 | 43.73 | 42.34 | 35.09 | 50.35 | 57.93 | 32.96 |

| 2022 | 42.51 | 37.10 | 38.64 | 51.05 | 63.45 | 22.31 |

| 2023 | 42.98 | 41.95 | 27.49 | 58.00 | 55.91 | 31.52 |

| 2024 | 42.82 | 32.65 | 63.07 | 50.24 | 41.49 | 26.66 |

| Type of Tourism Dispute | Moran Index (I) | Expected Value E (I) | Standard Deviation sd (I) | Z Value | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Travel Disputes | 0.415 | −0.1 | 0.187 | 2.699 | 0.003 |

| Travel Agency Disputes | 0.362 | −0.1 | 0.187 | 2.423 | 0.008 |

| Scenic Spots Disputes | 0.398 | −0.1 | 0.182 | 2.609 | 0.005 |

| Hotel Disputes | 0.410 | −0.1 | 0.165 | 2.671 | 0.004 |

| Catering Disputes | 0.541 | −0.1 | 0.188 | 3.361 | 0.000 |

| Passenger Transport Disputes | 0.527 | −0.1 | 0.192 | 3.285 | 0.001 |

| Type of Tourism Dispute | High–High Clustering | Low–High Clustering | Low–Low Clustering | High–Low Clustering |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Travel Disputes | Chongqing, Sichuan, Guizhou, Yunnan | Hunan | Jiangxi, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Anhui | Hubei |

| Travel Agency Disputes | Chongqing, Sichuan, Guizhou | Yunnan, Hubei, Hunan | Jiangxi, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Anhui | Shanghai |

| Scenic Spots Disputes | / | Chongqing, Yunnan, Anhui | Jiangxi, Hunan, Shanghai, Zhejiang | Sichuan, Guizhou, Hubei, Jiangsu |

| Hotel Disputes | Sichuan, Guizhou, Yunnan, Hunan | Chongqing | Jiangxi, Hubei, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Anhui | / |

| Catering Disputes | Sichuan, Guizhou, Yunnan | Chongqing | Jiangxi, Hubei, Hunan, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Anhui | / |

| Passenger Transport Disputes | Sichuan, Guizhou, Hunan | Chongqing, Yunnan, Jiangxi | Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Anhui | Hubei |

| Testing Method | Type of Tourism Dispute | Moran Index (I) | Expected Value E (I) | Standard Deviation sd (I) | Z Value | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjustment period for research | All Travel Disputes | 0.438 | −0.1 | 0.176 | 2.820 | 0.002 *** |

| Travel Agency Disputes | 0.273 | −0.1 | 0.165 | 1.954 | 0.025 *** | |

| Scenic Spots Disputes | 0.301 | −0.1 | 0.132 | 2.102 | 0.018 *** | |

| Hotel Disputes | 0.441 | −0.1 | 0.182 | 2.832 | 0.002 *** | |

| Catering Disputes | 0.316 | −0.1 | 0.194 | 2.181 | 0.015 *** | |

| Passenger Transport Disputes | 0.339 | −0.1 | 0.184 | 2.301 | 0.011 *** | |

| Replace the weight matrix | All Travel Disputes | 0.475 | −0.1 | 0.202 | 3.010 | 0.001 *** |

| Travel Agency Disputes | 0.354 | −0.1 | 0.198 | 2.377 | 0.009 *** | |

| Scenic Spots Disputes | 0.261 | −0.1 | 0.134 | 1.890 | 0.029 *** | |

| Hotel Disputes | 0.300 | −0.1 | 0.156 | 2.094 | 0.018 *** | |

| Catering Disputes | 0.276 | −0.1 | 0.176 | 1.968 | 0.025 *** | |

| Passenger Transport Disputes | 0.550 | −0.1 | 0.178 | 3.404 | 0.000 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, N.; Weng, G. Spatiotemporal Evolution of and Regional Differences in Consumer Disputes in the Tourism System: Empirical Evidence from the Yangtze River Economic Belt, China. Systems 2025, 13, 473. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13060473

Wang N, Weng G. Spatiotemporal Evolution of and Regional Differences in Consumer Disputes in the Tourism System: Empirical Evidence from the Yangtze River Economic Belt, China. Systems. 2025; 13(6):473. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13060473

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Ning, and Gangmin Weng. 2025. "Spatiotemporal Evolution of and Regional Differences in Consumer Disputes in the Tourism System: Empirical Evidence from the Yangtze River Economic Belt, China" Systems 13, no. 6: 473. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13060473

APA StyleWang, N., & Weng, G. (2025). Spatiotemporal Evolution of and Regional Differences in Consumer Disputes in the Tourism System: Empirical Evidence from the Yangtze River Economic Belt, China. Systems, 13(6), 473. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13060473