Risk Management Practices in the Purchasing System of an Automotive Company

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Understand the current state of the long-term procurement planning process and characterize the current approach to risk management;

- Identify the main risks associated with the current risk management approach;

- Define premises based on Bosch guidelines and risk management principles;

- Create a risk management strategy to support the department;

- Develop a strategy/manual of good practices, which incorporates a solution based on the defined premises and allows for better decision making;

- Weave a future action plan with potential improvements.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Risk and Risk Management

2.2. Risk Management Processes

2.3. The Importance of Risk Management

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Philosophy and Design

3.2. Data Collection Methods

- Document Analysis: Internal documents, procedural manuals, and project reports were reviewed to understand current risk protocols and trace past risk-related events;

- Direct Observation: Researchers conducted structured observations of team meetings, risk assessments, and procurement workflows. Observation protocols were used to ensure consistency and reduce bias;

- Semi-Structured Interviews: All six members of the department were interviewed individually. The interviews, conducted between February and March 2024, followed a guide structured around key risk management themes (e.g., identification, evaluation, communication, and mitigation). Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using thematic coding to uncover patterns and discrepancies across perspectives;

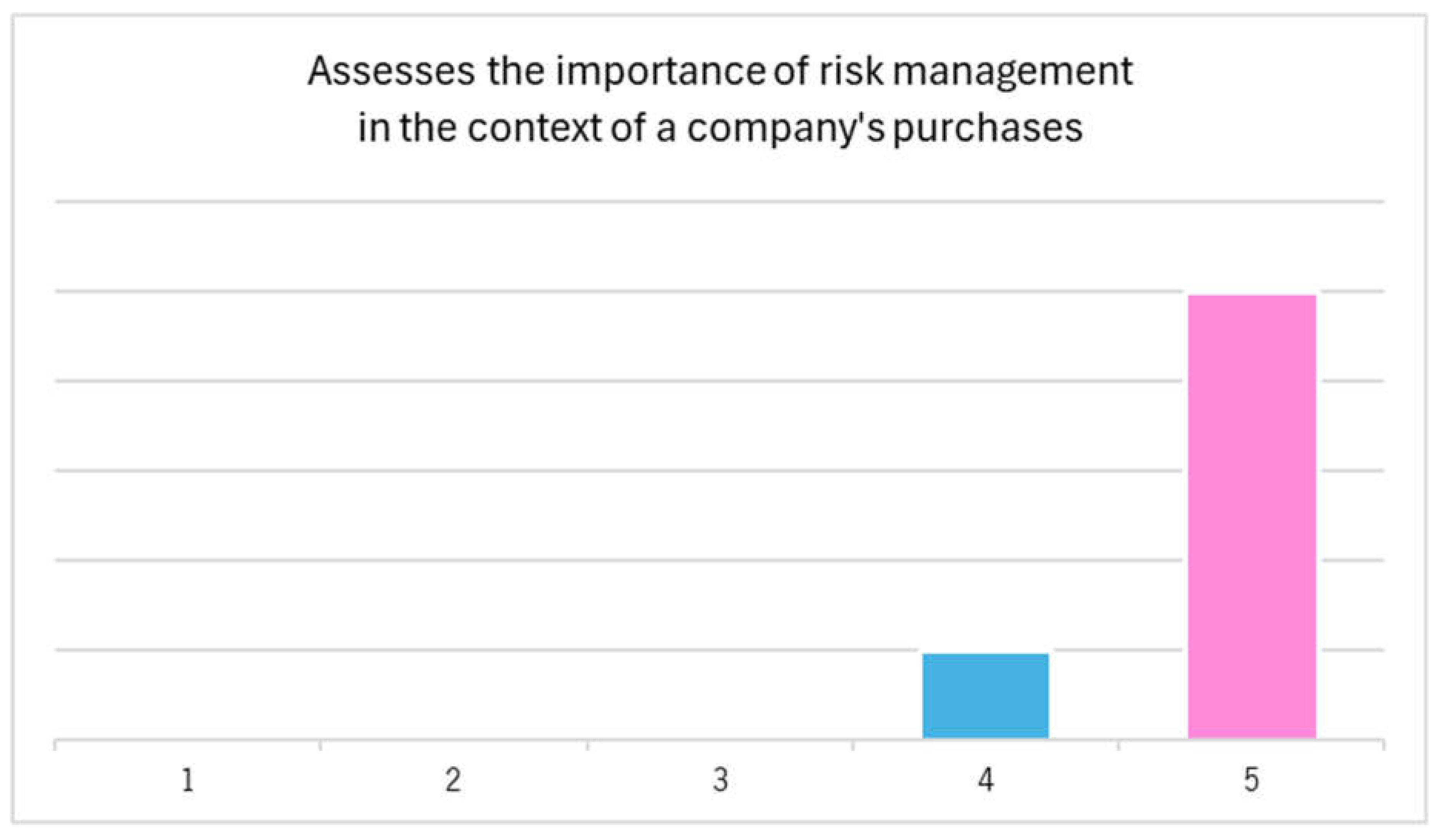

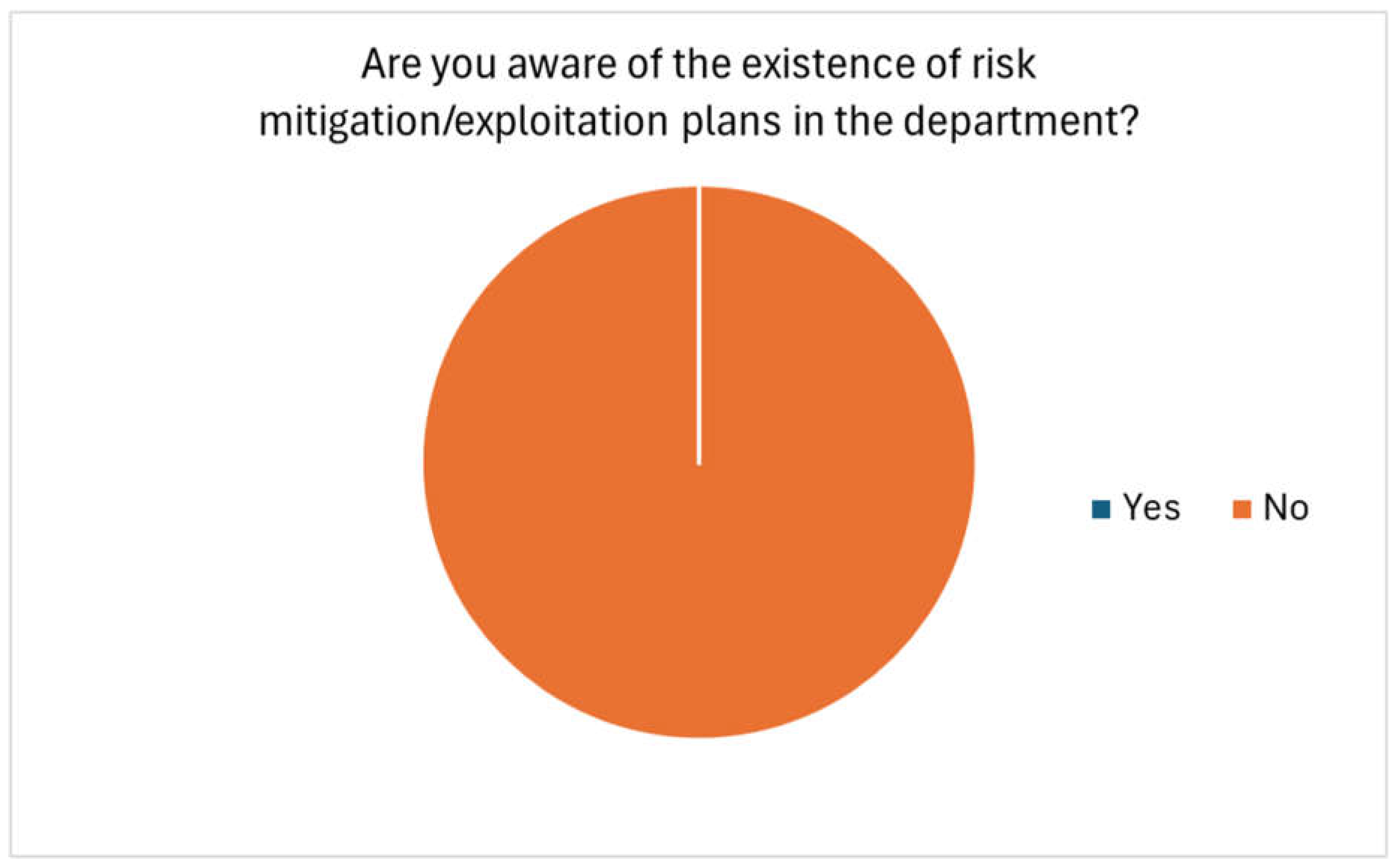

- Questionnaire Survey: A structured questionnaire was administered to all team members in March 2024. The questionnaire covered personal and professional profiles, conceptual understanding of risk management, identification and assessment capabilities, familiarity with tools and techniques, and perception of internal risk culture and communication. It included Likert-scale and open-ended questions. The questionnaire was pilot tested with two external project managers for clarity and relevance, and adjusted accordingly before final deployment.

3.3. Participants

3.4. Validity, Reliability, and Rigor

- Triangulation of data sources (documents, interviews, observations, and questionnaires) strengthened internal validity;

- Member checking was conducted by sharing preliminary findings with participants to validate interpretations;

- Audit trails documented analytical steps and coding decisions;

- Thematic saturation was observed during qualitative analysis, indicating sufficient depth of data collection.

3.5. Scope and Limitations

4. Case Study

5. Results of the Data Collection

5.1. Results

5.2. Thematic Analysis of Interview Data

- Theme 1: Conceptual Confusion and Lack of Training

“Sometimes I think of risks as things that are already happening. Like, if we’re already late, that’s a risk, right?”—Team Member A

“I’ve never had training in this area. I just use common sense most of the time.”—Team Member D

- Theme 2: Procedural Inconsistencies

“I usually talk to the team, but I don’t know if that’s the right way. Others might just write it in Excel and move on.”—Team Member B

“There’s no clear process. If something serious comes up, I go to my manager, but otherwise we just deal with it.”—Team Member E

- Theme 3: Openness to Improvement

“If we had clearer guidelines, I think everyone would follow them. It’s not that people don’t care—it’s just not well structured.”—Team Member C

“I’d definitely attend a workshop or training if it helped us make better decisions.”—Team Member F

5.3. Summary

6. Proposal to Improve Risk Management

6.1. Department Culture

6.2. LPS5 Project Improvement

- Risk identification: It was quickly realized that there were no measures or tools to identify the Risks (R) inherent to a project. There was also no relevant past documentation relating to risk management. In order to collect which risks need to be considered, a SWOT analysis was carried out. Through this analysis, the project’s Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats were collected. To be used as a complement to the analysis carried out previously, an Ishikawa diagram was created. A cost–benefit analysis was also carried out to evaluate the following possible actions: development and implementation of new forecasting models, improvement of data collection and analysis, improvement in communication of internal processes, and continuous monitoring and feedback. After risk collection, the team was advised to register the risks in the Super OPL tool.

- Risk analysis: After identifying the risks inherent to the project, it becomes necessary to define their prioritization with the aim of ordering their treatment in the most appropriate way. There are two types of analysis: quantitative and qualitative. Both analyses use numbers, but their approaches differ in how they assess risks. Only the most important risks from the qualitative analysis should proceed to the quantitative analysis. In order to analyze the collected data, the most relevant risks were divided into categories and listed in Table 1. The probability and impact of each risk were then qualitatively assessed, and the probability–impact matrix represented in Table 2 was prepared. According to the color system, warmer tones represent more urgent risks to be addressed, since, according to its assessment, they have a high probability and a great impact if they occur. In this case, risks R8 and R18 should be prioritized, followed by risks R16, R1, and R10. On the other hand, cooler tones should be last on the list of action priorities, since the combination of their probability and impact are lower than the others. In this case, we are talking about risks R17, R5, R12, R3, R14, and R15. Risks with the lowest scores, R7, R2, R11, R13, R9, and R4, must be monitored to ensure the correct assessment of their evolution. In case of change, the matrix must be updated. In addition to this method, the use of the Super OPL tool is also proposed.

- 3.

- Quantitative risk analysis: Quantitative risk analysis is a process considered more difficult and, therefore, less practical and left aside, justified by its non-applicability to the vast majority of risks. This analysis requires sensitive information that, due to the size of the company, becomes difficult to obtain, in addition to the fact that, often, the information is not provided due to the lack of appreciation of risk management. However, this analysis is considered important. Therefore, it is recommended that, in the initial phase, the analysis focus exclusively on risks numbered 1, 8, 10, 16, and 18. Once again, Super OPL appears to help in this risk assessment step. When the probabilities and impacts are filled in, the tool calculates the Expected Monetary Value (EMV). It is worth noting that, normally, the values used in this analysis represent mere estimates.

- 4.

- Risk response planning: Once there is a clear understanding of which risks are considered threats and which are considered opportunities, it is important to take steps to minimize the former and maximize the latter. It is up to the project team leader to delegate responsibilities for each risk. The person responsible for the risk in question must prioritize organizing meetings and discussion moments so that information can be gathered in order to follow the most appropriate treatment plan. According to the literature review, the risk management plan must include a description of the activities that will be carried out and how they will be structured. The tools to be used, the individuals responsible, and the guidelines for the approaches to be applied in managing the project’s risks must also be clearly defined and documented. It is still necessary (mandatory) to define the project life cycle periods and its contingency limits [32]. To assist in this step of risk management, the use of Super OPL was once again recommended, as it allows for effective support and detailed monitoring of the project. One of the points to be filled in is the strategy to be adopted, which should be aligned with the bibliographic review. Possible threat response strategies are avoidance, mitigation, transfer, and acceptance. Regarding opportunities, we can explore, improve, share, and accept. The topics “type” and “owner” are filled in by the tool automatically. These two topics define the measure and the person responsible for the project. The topic priority is defined by the user based on the graph in Table 3. It is also possible to add more detailed information regarding the strategy chosen to respond to the risk in consideration. The other fields such as categories, identification labels, costs, responsible parties. and people involved must also be filled in, in order to ensure transparency and the rapid flow of information through automatic emails from the tool itself.

- 5.

- Implementation of risk responses: Once risk responses have been planned, it is time for implementation. Despite being a case study, it is important to consider the practical application of the proposed measures, ensuring that the defined strategies are viable in the real context. The monitoring of implementations must be done using Super OPL. It is important to understand that one of the key points at this time is finding the so-called “right moment” to implement new measures. As experience shows, when a process is not given due importance, the right moment to implement it will never truly emerge. This results from a combination of several factors, including the availability of resources, their suitability for addressing the specific problem, and—most importantly—the ability to anticipate the potential consequences of not mitigating the risk. The mentioned tool should be used to register the risk responses, as an open point list, and as a complement; the project manager must then dynamize and always seek the involvement of those responsible for these actions, through periodic meetings and updating the status of this list.

- 6.

- Risk monitoring: As mentioned previously, project risk management is an ongoing process that spans the entire project life cycle, and it is essential to monitor both threats and opportunities. The measures adopted to manage these risks may need to be adjusted over time, as they may be unreliable or not have the expected effects. In the purchasing department, risk monitoring involves actions such as creating a risk map, with regular categorization and updates, as well as developing Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), such as delivery delays or cost variations. The use of automated indicators and alerts facilitates the early detection of changes in risk severity, while systematic incident logging enables timely adjustments to mitigation strategies. Integrating the mitigation plan into the overall project schedule and resource allocation ensures efficient execution. Therefore, it is recommended that the first weekly meeting of the project team, in the case of LPS5, be dedicated to updating the status of the actions taken for each identified risk, monitored by the Super OPL Risk Management Tool. The status of the most critical risks and the review of the risk list should be constant topics in meetings, so as not to be forgotten. If new risks arise, they must be included in the open points list, restarting the risk management cycle presented. These periodic review measures and the guarantee of recording lessons learned are essential to ensure continuous monitoring and the promotion of adjustments whenever necessary. This cycle ensures the evolution of each decision taken in a positive direction and, consequently, the exponential growth of the business unit involved.

7. Discussion

7.1. Organizational Culture and Risk Maturity

7.2. Process Structuring at the Project Level

7.3. Tool Utilization and Practical Limitations

7.4. Continuous Monitoring and Lessons Learned

8. Conclusions

8.1. Summary of Contributions

- Theoretical Validation: By applying PMBOK-based risk management frameworks to an industrial setting, the study confirms the practical applicability of established models in the automotive sector [32].

- Practical Outputs: The development of a Risk Management Manual, implementation of the Super OPL tool, and design of a replicable workshop format offer concrete, scalable solutions for similar project-based environments in manufacturing.

- Cultural Evolution: The study emphasizes the critical role of cultural transformation in risk management—an aspect often underestimated in project literature [58]. By fostering shared understanding and internal engagement, the groundwork for long-term change has been established.

8.2. Challenges and Considerations

8.3. Study Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EMV | Expected Monetary Value |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| KPI | Key Performance Indicator |

| LPS | Low Pressure Sensor |

| M/PPV-VDS1 | Purchasing Project Management Vehicle Motion |

| MFG | Manufacturing Global |

| MRP | Material Requirements Planning |

| OPL | Open Points List |

| P-I Matrix | Probability and Impact Matrix |

| PMI | Project Management Institute |

| PVA | Plant Volume Allocation |

| R | Risk |

| RQ | Research Question |

| SWOT | Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats |

References

- Vassolo, R.S.; Weisz, N.; Laker, B. Survival of the Fittest: Decoding Competition and Its Evolution. In Advanced Strategic Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Pilar Barrera, A.; Jimenez-Hernandez, P.R.; Medina-Ricaurte, G.F. Dynamic Capabilities to Drive Innovation and Competitivenss in a Changing Business World. In Models, Strategies, and Tools for Competitive SMEs; Perez-Uribe, R., Ocampo-Guzman, D., Lozano-Correa, L., Eds.; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 95–116. ISBN 9798369340479. [Google Scholar]

- Dinis-Carvalho, J.; Santos, D.; Menezes, M.; Sá, M.; Almeida, J. Process Mapping in a Prototype Development Case. Lect. Notes Electr. Eng. 2019, 505, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, G.; Domingues, J.; Tereso, A.; Micán, C.; Araújo, M. Risk Management in University–Industry R&D Collaboration Programs: A Stakeholder Perspective. Sustainability 2023, 15, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koen, P.A.; Bertels, H.M.J.; Elsum, I.R. The Three Faces of Business Model Innovation: Challenges for Established Firms. Res. Technol. Manag. 2011, 54, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boghani, A.; Brown, A. Meeting the Technology Management Challenges in the Automotive Industry; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2000; ISBN 0768005329. [Google Scholar]

- Baluch, N.; Sobry Abdullah, C.; Mohtar, S. Evaluating Effective Spare-Parts Inventory Management for Equipment Reliability in Manufacturing Industries. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2013, 5, 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, K.S.; Yeung, I.K.; Pun, K.F. Development of an Assessment System for Supplier Quality Management. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2006, 23, 743–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.D. Component Part Quality Assurance Concerns and Standards: Comparison of World-Class Manufacturers. Benchmarking 2011, 18, 128–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganhão, F.N.; Pereira, A. A Gestão Da Qualidade—Como Implementá-La Na Empresa, 1st ed.; Editorial Presença: Lisboa, Portugal, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Luko, S.N. Risk Management Principles and Guidelines. Qual. Eng. 2013, 25, 451–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, M.H.; Tereso, A.P.; Costa, H.R. Project Risk Management in an Automotive Company. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Quality Engineering and Management, Braga, Portugal, 21–22 September 2020; pp. 275–292. [Google Scholar]

- Klassen, R.D.; Vereecke, A. Social Issues in Supply Chains: Capabilities Link Responsibility, Risk (Opportunity), and Performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 140, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleindorfer, P.R.; Saad, G.H. Managing Disruption Risks in Supply Chains. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2005, 14, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brook, J.W.; Pagnanelli, F. Integrating Sustainability into Innovation Project Portfolio Management—A Strategic Perspective. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 2014, 34, 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harland, C.; Knight, L.; Lamming, R.; Walker, H. Outsourcing: Assessing the Risks and Benefits for Organisations, Sectors and Nations. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2005, 25, 831–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FERMA—Federation of European Risk Management Associations. Norma de Gestão de Riscos. Available online: https://www.ferma.eu/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/a-risk-management-standard-portuguese-version.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- ISO 31000; Risk Management–Principles and Guidelines. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- De Wulf, L.; Sokol, J.B. Customs Modernization Initiatives: Case Studies; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; ISBN 0821383736. [Google Scholar]

- Mizrak, K.C. Crisis Management and Risk Mitigation: Strategies for Effective Response and Resilience. In Trends, Challenges, and Practices in Contemporary Strategic Management; IGI Global: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 254–278. [Google Scholar]

- Raz, T.; Hillson, D. A Comparative Review of Risk Management Standards. Risk Manag. 2005, 7, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerzner, H. Project Management: A Systems Approach to Planning, Scheduling, and Controlling; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; ISBN 9781119165354. [Google Scholar]

- PMI. A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide), 7th ed.; Project Management Institute, Inc.: Newton Square, PA, USA, 2021; ISBN 9781628256642. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H. A Redefinition of the Project Risk Process: Using Vulnerability to Open up the Event-Consequence Link. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2007, 25, 694–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leveson, N. A Systems Approach to Risk Management through Leading Safety Indicators. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2015, 136, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardichvili, A.; Cardozo, R.; Ray, S. A Theory of Entrepreneurial Opportunity Identification and Development. J. Bus. Ventur. 2003, 18, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoneburner, G.; Goguen, A.; Feringa, A. Risk Management Guide for Information Technology Systems. NIST Spec. Publ. 2002, 800, 800–830. [Google Scholar]

- Zuccaro, G.; De Gregorio, D.; Leone, M.F. Theoretical Model for Cascading Effects Analyses. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2018, 30, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haimes, Y.Y. Risk Modeling, Assessment, and Management; Wiley Series in Systems Engineering and Management; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; ISBN 111901798X. [Google Scholar]

- Greiman, V.A. Megaproject Management: Lessons on Risk and Project Management from the Big Dig; PMI Project Management Institute; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; ISBN 9781118115473. [Google Scholar]

- Acebes, F.; González-Varona, J.M.; López-Paredes, A.; Pajares, J. Beyond Probability-Impact Matrices in Project Risk Management: A Quantitative Methodology for Risk Prioritisation. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PMI. A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide), 6th ed.; Project Management Institute, Inc.: Newton Square, PA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hugo, F.D.; Pretorius, L.; Benade, S.J. Some Aspects of the Use and Usefulness of Quantitative Risk Analysis Tools in Project Management. S. Afr. J. Ind. Eng. 2018, 29, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aven, T. Risk Analysis; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; ISBN 9781119057796. [Google Scholar]

- Vose, D. Risk Anaysis—A Quantitative Guide; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; p. 729. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, V.K.; Thakkar, J.J. A Quantitative Risk Assessment Methodology for Construction Project. Sadhana—Acad. Proc. Eng. Sci. 2018, 43, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, G.; Derr, R. Threat Assessment and Risk Analysis: An Applied Approach; Butterworth-Heinemann: Waltham, MA, USA, 2015; ISBN 9780128024935. [Google Scholar]

- Peixoto, J.; Tereso, A.; Fernandes, G.; Almeida, R. Project Risk Management Methodology: A Case Study of an Electric Energy Organization. Procedia Technol. 2014, 16, 1096–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hillson, D. Extending the Risk Process to Manage Opportunities. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2002, 20, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- António Miguel Gestão Moderna de Projetos Melhores Técnicas e Práticas; FCA: London, UK, 2024.

- Hiebl, M.R. The Integration of Risk into Management Control Systems: Towards a Deeper Understanding across Multiple Levels of Analysis. J. Manag. Control 2024, 35, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutsch, E.; Hall, M. Intervening Conditions on the Management of Project Risk: Dealing with Uncertainty in Information Technology Projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2005, 23, 591–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loosemore, M.; Raftery, J.; Reilly, C.; Higgon, D. Risk Management in Projects, 2nd ed.; Taylor and Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2012; ISBN 9780203963708. [Google Scholar]

- Zwikael, O.; Ahn, M. The Effectiveness of Risk Management: An Analysis of Project Risk Planning Across Industries and Countries. Risk Anal. 2011, 31, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bockius, H.; Gatzert, N. Organizational Risk Culture: A Literature Review on Dimensions, Assessment, Value Relevance, and Improvement Levers. Eur. Manag. J. 2024, 42, 539–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WSJ. Supply Chain Woes Carry High Risks, Big Rewards for Some Companies. The Wall Street Journal, 30 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkinson, M. The Project Risk Maturity Model: Measuring and Improving Risk Management Capability; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2017; ISBN 9781351883467. [Google Scholar]

- Olsson, R. In Search of Opportunity Management: Is the Risk Management Process Enough? Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2007, 25, 745–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kour, R.; Karim, R.; Dersin, P.; Venkatesh, N. Cybersecurity for Industry 5.0: Trends and Gaps. Front. Comput. Sci. 2024, 6, 1434436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, P.; Jack, S. Qualitative Case Study Methodology: Study Design and Implementation for Novice Researchers. Qual. Rep. 2008, 13, 544–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018; ISBN 9781506336176. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students, 8th ed.; Pearson: Harlow, UK, 2019; ISBN 978-1292208787. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch. Company|Bosch Global. Available online: https://www.bosch.com/company/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Bosch. A Nossa Empresa|Bosch Em Portugal. Available online: https://www.bosch.pt/a-nossa-empresa/bosch-em-portugal/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Bosch. Bosch Internal Documentation; Bosch’s Private Portal: Braga, Portugal, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, K.; Smidt, M. A Risk Perspective on Human Resource Management: A Review and Directions for Future Research. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2016, 26, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qazi, A.; Dikmen, I.; Birgonul, M.T. Mapping Uncertainty for Risk and Opportunity Assessment in Projects. Eng. Manag. J. 2020, 32, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillson, D.; Murray-Webster, R. Understanding and Managing Risk Attitude, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2007; ISBN 9781315235448. [Google Scholar]

| Type of Risks | Risk Description | Risk Number |

|---|---|---|

| Financial | Overly optimistic sales forecasts resulting in lower-than-expected revenue. | R1 |

| Higher-than-anticipated production costs that may lead to reduced profit margins. | R2 | |

| Investing in a large amount of inventory and equipment that ties up capital that could be used for other investment opportunities. | R3 | |

| Possible fluctuations in the exchange rate may impact production costs and revenues if there are imported components or exports. | R4 | |

| Operational | The possibility that production capacity is not sufficient to manufacture the sensors efficiently. | R5 |

| Product quality issues that may result in returns, repairs, or replacements. | R6 | |

| Difficulties in storing and transporting sensors. | R7 | |

| Market | The risk that actual demand will differ from forecast demand, resulting in excess or shortfalls in inventory. | R8 |

| Competitor actions that may affect market share and demand for sensors. | R9 | |

| New technologies or changes in consumer preferences that may make the product obsolete. | R10 | |

| Regulatory | Changes in regulations that may impact the production or sale of sensors. | R11 |

| Risk of non-compliance with standards and regulations, resulting in fines or sanctions. | R12 | |

| Reputational | Problems with product quality or customer service that could damage the company’s reputation. | R13 |

| Negative impact on brand image due to problems with project management. | R14 | |

| Human | Difficulties in attracting and retaining qualified talent necessary for the company’s strategy. | R15 |

| Failures in marketing and sales strategies that may not be able to reach the target audience effectively. | R16 | |

| Possibility of human error when reading forecasts, due to the use of an easily fallible tool. | R17 | |

| Possibility of human errors when making decisions about the volumes of the product to be produced. | R18 |

| Probability | Impact | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 1 | R4 | ||||

| 2 | R2, R11, R13 | R9 | |||

| 3 | R7 | R14, R15 | R5, R12 | ||

| 4 | R3 | R17 | R1, R10 | ||

| 5 | R16 | R8, R18 | |||

| High Impact | Plan Important but not urgent | Immediate The best action, take it as soon as possible |

| Low Impact | Postpone To do, but not to waste time | Consider Urgent but not important |

| Low Urgency | High Urgency | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tereso, A.; Santos, C.; Faria, J. Risk Management Practices in the Purchasing System of an Automotive Company. Systems 2025, 13, 444. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13060444

Tereso A, Santos C, Faria J. Risk Management Practices in the Purchasing System of an Automotive Company. Systems. 2025; 13(6):444. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13060444

Chicago/Turabian StyleTereso, Anabela, Cláudia Santos, and João Faria. 2025. "Risk Management Practices in the Purchasing System of an Automotive Company" Systems 13, no. 6: 444. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13060444

APA StyleTereso, A., Santos, C., & Faria, J. (2025). Risk Management Practices in the Purchasing System of an Automotive Company. Systems, 13(6), 444. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13060444