The Coordinated Relationship Between the Tourism Economy System and the Tourism Governance System: Empirical Evidence from China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

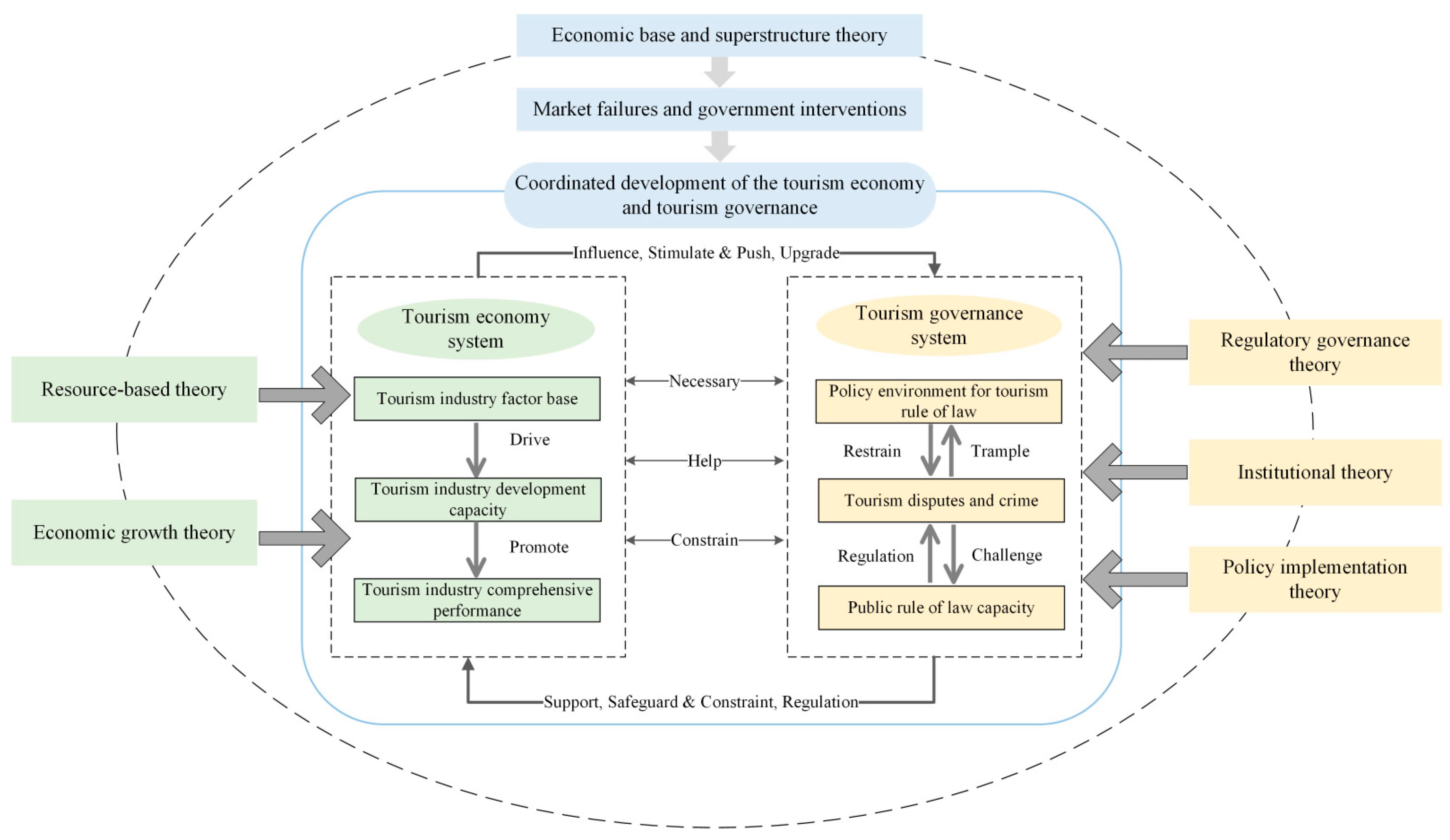

2. Theoretical Framework for Coordinated Interaction Between the Tourism Economic System and the Tourism Governance System

3. Research Design and Methodology

3.1. Research Design and Logical Ideas

3.2. Building the Indicator System

3.2.1. Tourism Economy System

3.2.2. Tourism Governance System

3.3. Methodology

3.3.1. Vertical and Horizontal Differentiation Method

3.3.2. Panel Vector Auto-Regression (PVAR) Model

3.3.3. Modified Coupling Coordination Model

3.3.4. Kernel Density Estimation

3.3.5. Markov Chain Model

- (1)

- Traditional Markov Chains

- (2)

- Spatial Markov Chains

3.4. Data Sources

4. Results

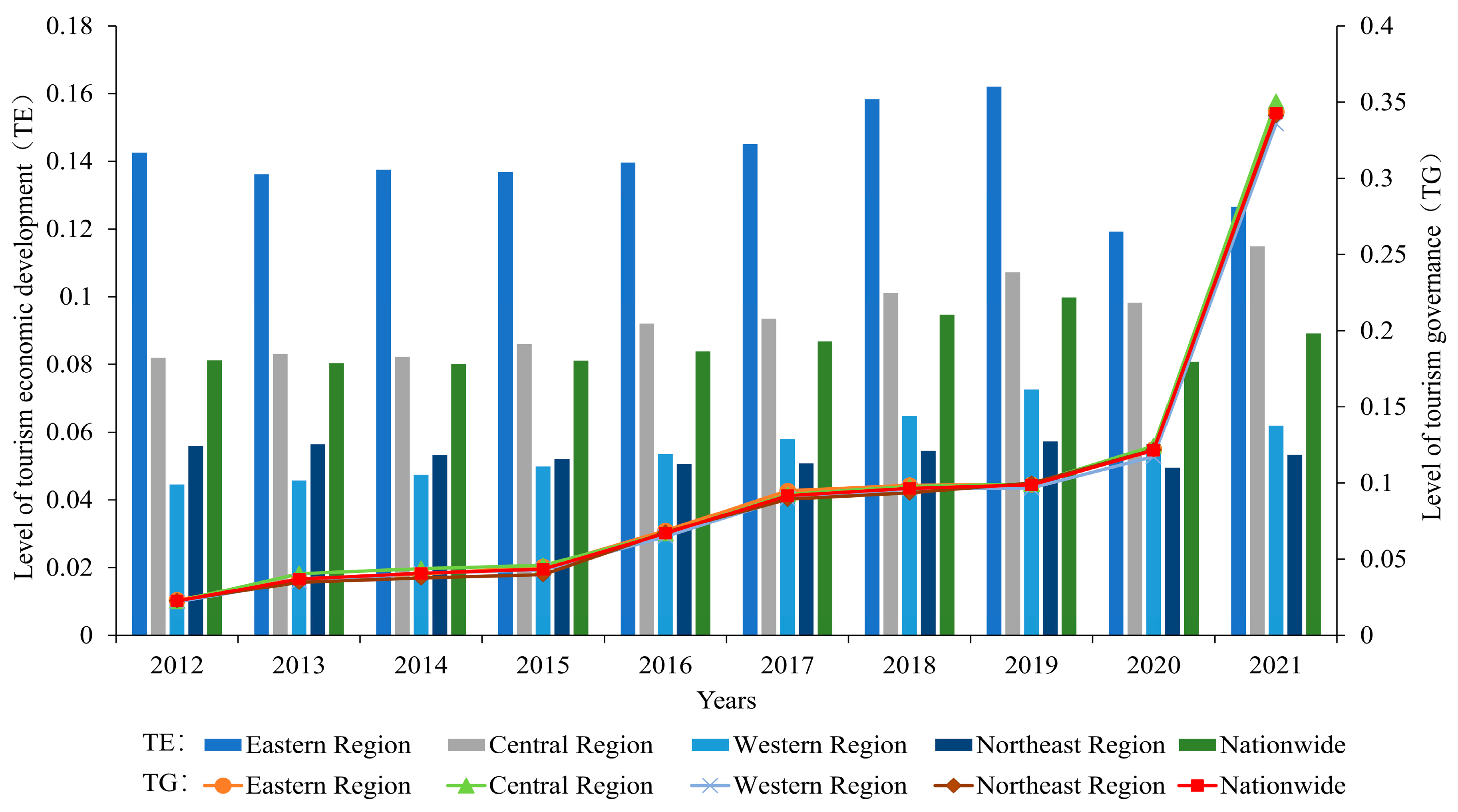

4.1. Analysis of the Temporal and Spatial Evolution of TE and TG

4.1.1. Characteristics of Temporal Distribution

4.1.2. Characteristics of Spatial Distribution

4.2. Analysis of Causal Interactions Between TE and TG

4.2.1. Variable Stability Test

4.2.2. Optimal Lag Order Selection and Cointegration Test

4.2.3. Granger Causality Test

4.2.4. Impulse Response Analysis

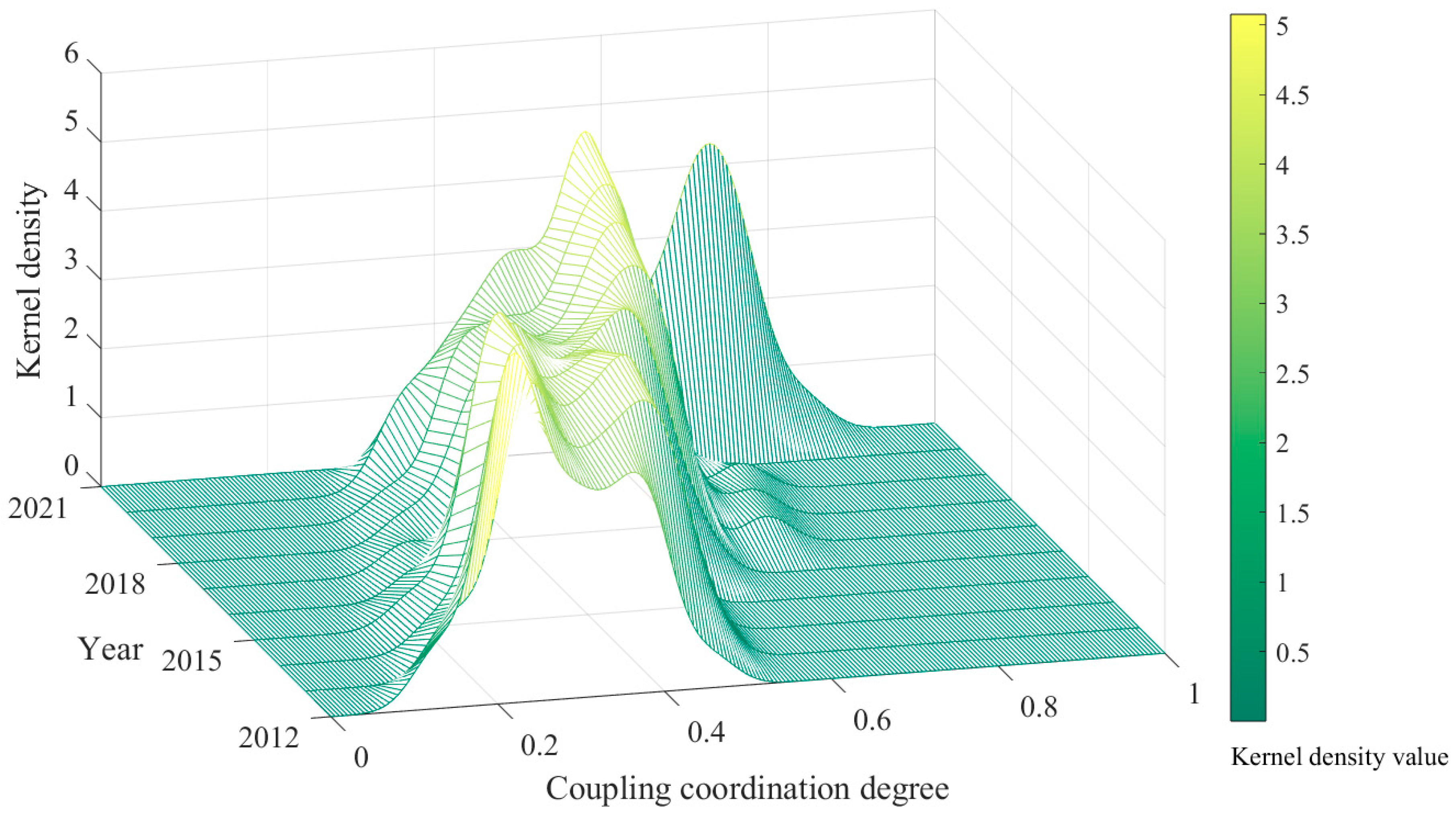

4.3. Analysis of the Coordinated Development of TE and TG

4.3.1. Characteristics of Temporal Evolution

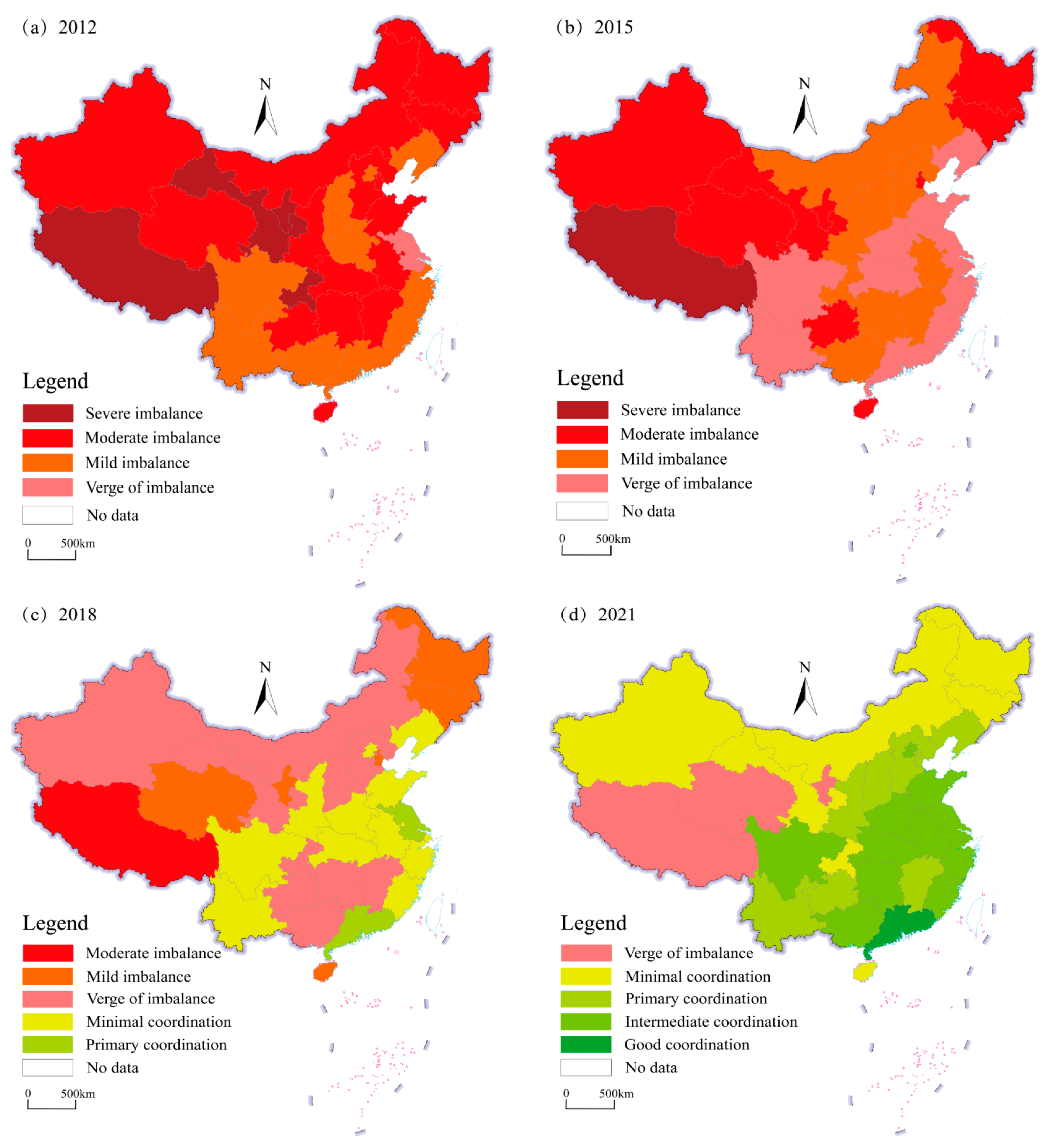

4.3.2. Characteristics of Spatial Evolution

4.3.3. Characteristics of Coupling Coordination Types

4.3.4. Markov Analysis of Coupled Coordination Types

Traditional Markov Analysis

Spatial Markov Analysis

4.4. Robustness Analysis

4.4.1. Adding Evaluation Indicators

Internal Variable Validation

External Variable Validation

4.4.2. Changing the Measurement of Variables

4.4.3. Shortening the Sample Study Period

5. Discussion

6. Conclusion

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, Y.Y.; McGehee, N.G. Tour guides under zero-fare mode: Evidence from China. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 1088–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.Y. The historical evolution of China's tourism development policies (1949–2013)—A quantitative research approach. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido-Fernández, J.I.; Pulido-Fernández, M.D. Proposal for an Indicators System of Tourism Governance at Tourism Destination Level. Soc. Indic. Res. 2018, 137, 695–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Kraus, S.; Pocek, J.; Meyer, N.; Jensen, S.H. The why, h.0ow, and what of public policy implications of tourism and hospitality research. Tour. Manag. 2023, 97, 104720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsalobre-Lorente, D.; Driha, O.M.; Bekun, F.V.; Adedoyin, F.F. The asymmetric impact of air transport on economic growth in Spain: Fresh evidence from the tourism-led growth hypothesis. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 503–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidi, M.; Guardiancich, I.; Levi-Faur, D. Modes of regulatory governance: A political economy perspective. Gov. Int. J. Policy Adm. Inst. 2020, 33, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, A.M.; Lu, J.Y.; Zhao, Z.Y. Rural destination revitalization in China: Applying evolutionary economic geography in tourism governance. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 26, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofield, T.; Li, S. Tourism governance and sustainable national development in China: A macro-level synthesis. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 501–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bichler, B.F. Designing tourism governance: The role of local residents. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 19, 100389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.X.; Shi, P.H. The evolutionary characteristics, driving mechanism, and optimization path of China's tourism support policies under COVID-19: A quantitative analysis based on policy texts. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 1169–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earl, A.; Hall, C.M. Institutional Theory in Tourism and Hospitality; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Soares, A.L.V.; Mendes, L.; Gretzel, U. Technology adoption in hotels: Applying institutional theory to tourism. Tour. Rev. 2021, 76, 669–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, J.; Page, S.J.; Bentley, T. Towards sustainable tourism planning in New Zealand: Monitoring local government planning under the Resource Management Act. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 867–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.F.; Chang, Y.; Pearce, P.L. China’s first Tourism Law: Representations of stakeholders' responses. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2018, 16, 309–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khater, M.; Ibrahim, O.; Sayed, M.N.E.; Faik, M. Legal frameworks for sustainable tourism: Balancing environmental conservation and economic development. Curr. Issues Tour. Early Access. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coban, M.K.; Apaydin, F. Navigating financial cycles: Economic growth, bureaucratic autonomy, and regulatory governance in emerging markets. Regul. Gov. 2025, 19, 126–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Ap, J. Factors affecting tourism policy implementation: A conceptual framework and a case study in China. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinica, V. Tourism on Curacao: Explaining the Shortage of Sustainability Legislation from Game Theory Perspective. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2012, 14, 161–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, K. A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy; lnternational Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta, N.; Kar, S. Relating rule of law and budgetary allocation for tourism: Does per capita income growth make a difference for Indian states? Econ. Model. 2018, 71, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; Wang, M. Tourism law, labor supply and corporate performance in tourism listed firms. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 68, 105971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asongu, S.A.; Rahman, M.; Nnanna, J. Law, political stability, tourism management and economic development in sub-Saharan Africa. Curr. Issues Tour. 2023, 26, 2678–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.X.; Cheng, Z.H.; Tong, Y.; He, B.A. The Interaction Mechanism of Tourism Carbon Emission Efficiency and Tourism Economy High-Quality Development in the Yellow River Basin. Energies 2022, 15, 6975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Zhou, Q.; Cheng, Y.F.; Zhang, Y.T.; Li, T.; Yan, X.Y.; Alimov, A.; Farmanov, E.; David, L.D. Regional sustainability: Pressures and responses of tourism economy and ecological environment in the Yangtze River basin, China. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 11, 1148868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.S. Management Model of the Coordinated Development of the Coastal Ecological Environment and Rural Tourism Economy. J. Coast. Res. 2020, 106, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.H.; He, X.R.; Cai, C.Y. Does the Digital Economy Promote Tourism Eco-Efficiency? - An Empirical Study Based on Chinese Cities. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2025, 34, 2063–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.N.; Jiang, G.L.; Merajuddin, S.S.; Zhao, F. Urbanization and tourism economic development. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 73, 106632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Zhan, L.X.; Li, S.B. Is sustainable development reasonable for tourism destinations? An empirical study of the relationship between environmental competitiveness and tourism growth. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, P.; Zheng, X.R.; Duan, L.; Xu, X.B.; He, M. A Study of the Contribution of Information Technology on the Growth of Tourism Economy Using Cross-Sectional Data. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2019, 27, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Z.Z.; Ge, D.M.; Xia, H.B.; Yue, Y.L.; Wang, Z. Coupling coordination between environment, economy and tourism: A case study of China. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.Y.; Sang, S.Y.; Zhu, Y.R. Analysis of coupled coordination and spatial interaction effects between digital and tourism economy in the Yangtze River Delta region. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0307756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Mei, X.H.; Xiao, Z.Q. Spatio-temporal evolution of sports tourism industry integration: A empirical analysis of Xinjiang in China. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0300959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Huang, X.K.; Shi, J.L.; Zheng, Y.M.; Wang, J.H. Connections and Spatial Network Structure of the Tourism Economy in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei: A Social Network Perspective. Land 2024, 13, 1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Peng, B.F.; Zhou, L.L.; Lu, C.Y.; Wang, Y.L.; Liu, R.; Xiang, H. Tourism development potential and obstacle factors of cultural heritage: Evidence from traditional music in Xiangxi. J. Geogr. Sci. 2024, 34, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.C.; Wu, X.F.; Zheng, Q.Q.; Lyu, N. Ecological security evaluations of the tourism industry in Ecological Conservation Development Areas: A case study of Beijing's ECDA. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 197, 999–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.K.; Lin, F.Y.; Chu, D.P.; Wang, L.L.; Liao, J.W.; Wu, J.Q. Coupling Relationship and Interactive Response between Intensive Land Use and Tourism Industry Development in China's Major Tourist Cities. Land 2021, 10, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Peng, Q.; Chen, M.H.; Su, C.H. Understanding the evolution of China's tourism industry performance: An internal-external framework. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 22, 479–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wu, S.F. Efficiency Evaluation and Spatio-Temporal Differentiation Analysis of tourism Industry in Cities Along the Beijing Hangzhou Grand Canal Based on Three-Stage DEA. Sage Open 2024, 14, 21582440241300557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X. Challenges and potential improvements in the policy and regulatory framework for sustainable tourism planning in China: The case of Shanxi Province. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 455–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, S.O.; Tumer, M.; Ozturen, A.; Kilic, H. Mediating role of legal services in tourism development: A necessity for sustainable tourism destinations. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 2866–2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.X.; Yao, Y.B.; Fan, D.X.F. Evaluating Tourism Market Regulation from Tourists' Perspective: Scale Development and Validation. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 975–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.J.; Li, Z.J.; Hou, B. The Influencing Effect of Tourism Economy on Green Development Efficiency in the Yangtze River Delta. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.F.; Zhai, D.X.; Zhao, X.F.; Wu, D.L. The Impact of Property Rights Structure on High-Quality Development of Enterprises Based on Integrated Machine Learning-A Case Study of State-Owned Enterprises in China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, B.W. Density Estimation for Statistics and Data Analysis; Chapman and Hall: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.P.; Liu, L.L.; Wang, X.Y.; Niu, J.; Zhang, X.B. Spatio-temporal Evolution of Tourism Development Quality under the New Development Pattern of “Double Circulation”. Appl. Spat. Anal. Policy 2023, 16, 647–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.C. Accelerating domestic and international dual circulation in the Chinese shipping industry-An assessment from the aspect of participating RCEP. Mar. Policy 2022, 135, 104862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuscer, K.; Eichelberger, S.; Peters, M. Tourism organizations’ responses to the COVID-19 pandemic: An investigation of the lockdown period. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.C.; Liu, S.; Zhang, X. The construction of Global Maritime Capital-Current development in China. Mar. Policy 2023, 151, 105576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porto, N.; Ciaschi, M. Reformulating the tourism-extended environmental Kuznets curve: A quantile regression analysis under environmental legal conditions. Tour. Econ. 2021, 27, 991–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.Y.; Lin, W.Y.; Sun, M.Y.; Chen, P. Spatiotemporal Evolution and Driving Forces of Tourism Economic Resilience in Chinese Provinces. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.G.; Gao, L.; Zhu, Y.L.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.Y.; He, J.C. Urban-Rural Integration Empowers High-Quality Development of Tourism Economy: Mechanism and Empirical Evidence. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.C. Maritime clusters: What can be learnt from the South West of England. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2011, 54, 488–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.F.; Liu, H.Y. How tourism industry agglomeration improves tourism economic efficiency? Tour. Econ. 2022, 28, 1724–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Subsystem | Dimensions | Indicators (Unit) | References | Attributes | Weights |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level of development of the tourism economy (TE) | Tourism industry factor base | Number of travel agencies | [1,30,31,32] | + | 0.0424 |

| Number of A-grade scenic spots | + | 0.0397 | |||

| Number of catering enterprises | + | 0.0669 | |||

| Number of accommodation enterprises | + | 0.0500 | |||

| Number of star-rated hotels | + | 0.0336 | |||

| Passenger transport capacity (104 person-times) | + | 0.0464 | |||

| Tourism industry development capacity | Number of employees in travel agencies | [33,34,35] | + | 0.0861 | |

| Number of employees in tourist attractions | + | 0.0585 | |||

| Number of employees in the catering industry | + | 0.0831 | |||

| Number of employees in the accommodation industry | + | 0.0542 | |||

| Number of employees in star-rated hotels | + | 0.0888 | |||

| Tourism industry comprehensive performance | Tourism consumption capacity of residents (104 yuan) | [36,37,38] | + | 0.0287 | |

| Number of international tourists (104 person-times) | + | 0.1378 | |||

| Domestic tourist arrivals (104 person-times) | + | 0.0451 | |||

| International tourism income (104 dollars) | + | 0.0777 | |||

| Domestic tourism income (108 yuan) | + | 0.0609 |

| Subsystem | Dimensions | Indicators (Unit) | References | Attributes | Weights |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level of development of tourism governance (TG) | The policy environment for tourism governance | Tourism-related laws (Number) | [3,14,21] | + | 0.0424 |

| Administrative laws and regulations on tourism (Number) | + | 0.0397 | |||

| Local laws and regulations on tourism (Number) | + | 0.0669 | |||

| Judicial interpretation on tourism (Number) | + | 0.0500 | |||

| Departmental regulations on tourism (Number) | + | 0.0336 | |||

| Local government regulations on tourism (Number) | + | 0.0464 | |||

| Tourism disputes and crimes | Litigation disputes of travel agencies (Number) | [22,39,40] | - | 0.0861 | |

| Litigation disputes in scenic spots (Number) | - | 0.0585 | |||

| Catering litigation disputes (Number) | - | 0.0831 | |||

| Hotel litigation disputes (Number) | - | 0.0542 | |||

| Litigation disputes on passenger transportation (Number) | - | 0.0888 | |||

| Public governance capacity | Regional level of governance (/) | [2,3,41] | + | 0.0287 | |

| Number of lawyers | + | 0.1378 | |||

| Public crime rate (%) | - | 0.0451 | |||

| Judicial efficiency (/) | + | 0.0777 | |||

| Judicial civility index (/) | + | 0.0609 |

| D-Value of Coordination | Degree of Coordination | Relationship | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| [0.0~0.1) | Extreme imbalance | TE < TG | Type of TE lag |

| TE ≈ TG | Type of synchronization between TE and TG | ||

| TE > TG | Type of TG lag | ||

| [0.1~0.2) | Severe imbalance | TE < TG | Type of TE lag |

| TE ≈ TG | Type of synchronization between TE and TG | ||

| TE > TG | Type of TG lag | ||

| [0.2~0.3) | Moderate imbalance | TE < TG | Type of TE lag |

| TE ≈ TG | Type of synchronization between TE and TG | ||

| TE > TG | Type of TG lag | ||

| [0.3~0.4) | Mild imbalance | TE < TG | Type of TE lag |

| TE ≈ TG | Type of synchronization between TE and TG | ||

| TE > TG | Type of TG lag | ||

| [0.4~0.5) | Verge of imbalance | TE < TG | Type of TE lag |

| TE ≈ TG | Type of synchronization between TE and TG | ||

| TE > TG | Type of TG lag | ||

| [0.5~0.6) | Minimal coordination | TE < TG | Type of TE lag |

| TE ≈ TG | Type of synchronization between TE and TG | ||

| TE > TG | Type of TG lag | ||

| [0.6~0.7) | Primary coordination | TE < TG | Type of TE lag |

| TE ≈ TG | Type of synchronization between TE and TG | ||

| TE > TG | Type of TG lag | ||

| [0.7~0.8) | Intermediate coordination | TE < TG | Type of TE lag |

| TE ≈ TG | Type of synchronization between TE and TG | ||

| TE > TG | Type of TG lag | ||

| [0.8~0.9) | Good coordination | TE < TG | Type of TE lag |

| TE ≈ TG | Type of synchronization between TE and TG | ||

| TE > TG | Type of TG lag | ||

| [0.9~1.0] | Quality coordination | TE < TG | Type of TE lag |

| TE ≈ TG | Type of synchronization between TE and TG | ||

| TE > TG | Type of TG lag |

| Variables | LLC Testing | IPS Testing | Test Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| TE | −6.6481 (0.0000) *** | −6.4041 (0.0000) *** | smooth |

| TG | −9.0116 (0.0000) *** | −5.5336 (0.0000) *** | smooth |

| Lag Order | AIC | BIC | HQIC |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 25.25682 | −8.587356 * | 11.58885 |

| 2 | 16.19392 * | −6.368334 | 7.828682 * |

| 3 | 18.72026 | 7.439136 | 14.1376 |

| Testing Methods | Testing Statistics | Statistical Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kao testing | Modified Dickey–Fuller t | −9.3915 | 0.0000 *** |

| Dickey–Fuller t | −11.9303 | 0.0000 *** | |

| Augmented Dickey–Fuller t | −6.1115 | 0.0000 *** | |

| Unadjusted modified Dickey–Fuller t | −9.4240 | 0.0000 *** | |

| Unadjusted Dickey–Fuller t | −11.9367 | 0.0000 *** | |

| Pedroni testing | Modified Phillips–Perron t | 3.4429 | 0.0003 *** |

| Augmented Dickey–Fuller t | −8.2281 | 0.0000 *** | |

| Phillips–Perron t | −7.8539 | 0.0000 *** | |

| Westerlund testing | Variance ratio | 1.6839 | 0.0461 ** |

| Original Hypothesis | Chi2 Statistic | Lag Order | p-Value | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TG is not the Granger cause of TE | 16.149 | 2 | 0.000 *** | reject |

| None of the variables are the Granger cause of TE | 16.149 | 2 | 0.000 *** | reject |

| TE is not the Granger cause of TG | 15.516 | 2 | 0.000 *** | reject |

| None of the variables are the Granger cause of TG | 15.516 | 2 | 0.000 *** | reject |

| Year | TE Lag | TE-TG synchronization | TG Lag |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | Qinghai | Hainan, Yunnan, Tibet, Ningxia | Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Shanxi, Inner Mongolia, Liaoning, Jilin, Heilongjiang, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Anhui, Fujian, Jiangxi, Shandong, Henan, Hubei, Hunan, Guangdong, Guangxi, Chongqing, Sichuan, Guizhou, Shaanxi, Gansu, Xinjiang |

| 2015 | Hainan, Tibet, Qinghai, Ningxia | Tianjin, Shanxi, Jilin, Heilongjiang, Fujian, Yunnan, Gansu, Xinjiang | Beijing, Hebei, Inner Mongolia, Liaoning, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Anhui, Jiangxi, Shandong, Henan, Hubei, Hunan, Guangdong, Guangxi, Chongqing, Sichuan, Guizhou, Shaanxi |

| 2018 | Tianjin, Shanxi, Inner Mongolia, Liaoning, Jilin, Heilongjiang, Fujian, Hainan, Guizhou, Yunnan, Tibet, Gansu, Xinjiang, Qinghai, Xinjiang | Hebei, Jiangxi, Henan, Guangxi, Chongqing, Shaanxi | Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Anhui, Shandong, Hubei, Hunan, Guangdong, Sichuan |

| 2021 | / | / | Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Shanxi, Inner Mongolia, Liaoning, Jilin, Heilongjiang, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Anhui, Fujian, Jiangxi, Shandong, Henan, Hubei, Hunan, Guangdong, Guangxi, Hainan, Chongqing, Sichuan, Guizhou, Yunnan, Tibet, Shaanxi, Gansu, Qinghai, Ningxia, Xinjiang |

| Type of Spatial Lag | t/t + 1 | n | I | II | III | IV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No lag | I | 12 | 0.3333 | 0.6667 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| II | 149 | 0.0000 | 0.7919 | 0.2081 | 0.0000 | |

| III | 114 | 0.0000 | 0.0088 | 0.8333 | 0.1579 | |

| IV | 4 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 |

| Type of Spatial Lag | Situation of The Regions | n | I | II | III | IV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | I | 2 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| II | 2 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | |

| III | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | |

| IV | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | |

| II | I | 10 | 0.4000 | 0.6000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| II | 120 | 0.0000 | 0.8500 | 0.1500 | 0.0000 | |

| III | 28 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.9286 | 0.0714 | |

| IV | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | |

| III | I | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| II | 27 | 0.0000 | 0.5185 | 0.4815 | 0.0000 | |

| III | 86 | 0.0000 | 0.0116 | 0.8023 | 0.1860 | |

| IV | 4 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | |

| IV | I | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| II | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | |

| III | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | |

| IV | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| Methods | Variant | LLC Testing | IPS Testing | Test Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adding evaluation indicators (internal variable validation) | TE | −6.6481 (0.0000) *** | −6.4041 (0.0000) *** | smooth |

| TG | −22.0833 (0.0000) *** | −6.2655 (0.0000) *** | smooth |

| Methods | Lag Order | AIC | BIC | HQIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adding evaluation indicators (internal variable validation) | 1 | −7.71381 * | −6.68582 * | −7.29855 * |

| 2 | −7.40311 | −6.18912 | −6.91115 | |

| 3 | −7.05289 | −5.5999 | −6.46272 |

| Methods | Test Method | Test Statistics | Statistical Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adding evaluation indicators (internal variable validation) | Kao test | Modified Dickey–Fuller t | −6.8909 | 0.0000 *** |

| Dickey–Fuller t | −12.4409 | 0.0000 *** | ||

| Augmented Dickey–Fuller t | −5.0898 | 0.0000 *** | ||

| Unadjusted modified Dickey–Fuller t | −10.4647 | 0.0000 *** | ||

| Unadjusted Dickey–Fuller t | −13.4724 | 0.0000 *** | ||

| Pedroni test | Modified Phillips–Perron t | 1.5824 | 0.0568 * | |

| Augmented Dickey–Fuller t | −11.3552 | 0.0000 *** | ||

| Phillips–Perron t | −14.4859 | 0.0000 *** | ||

| Westerlund test | Variance ratio | −1.8184 | 0.0345 ** |

| Methods | Original Hypothesis | Chi2 Statistic | Lag Order | p-Value | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adding evaluation indicators (internal variable validation) | TG is not the Granger cause of TE | 11.204 | 1 | 0.001 *** | reject |

| None of the variables are the Granger cause of TE | 11.204 | 1 | 0.001 *** | reject | |

| TE is not a Granger cause of TG | 357.31 | 1 | 0.000 *** | reject | |

| None of the variables are the Granger cause of TG | 357.31 | 1 | 0.000 *** | reject |

| Methods | Variant | LLC Testing | IPS Testing | Test Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adding evaluation indicators (external variable validation) | TE | −21.8969 (0.0000) *** | −10.5720 (0.0000) *** | smooth |

| TG | −23.4587 (0.0000) *** | −9.8062 (0.0000) *** | smooth |

| Methods | Lag Order | AIC | BIC | HQIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adding evaluation indicators (external variable validation) | 1 | −6.5847 * | −5.55671 * | −6.16943 * |

| 2 | −6.26126 | −5.04727 | −5.76931 | |

| 3 | −5.80539 | −4.3524 | −5.21522 |

| Methods | Test Method | Test Statistics | Statistical Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adding evaluation indicators (external variable validation) | Kao test | Modified Dickey–Fuller t | −6.2351 | 0.0000 *** |

| Dickey–Fuller t | −12.2127 | 0.0000 *** | ||

| Augmented Dickey–Fuller t | −4.5356 | 0.0000 *** | ||

| Unadjusted modified Dickey–Fuller t | −10.537 | 0.0000 *** | ||

| Unadjusted Dickey–Fuller t | −13.5667 | 0.0000 *** | ||

| Pedroni test | Modified Phillips–Perron t | 1.4371 | 0.0753 * | |

| Augmented Dickey–Fuller t | −11.5214 | 0.0000 *** | ||

| Phillips–Perron t | −14.2437 | 0.0000 *** | ||

| Westerlund test | Variance ratio | −1.9248 | 0.0271 ** |

| Methods | Original Hypothesis | Chi2 Statistic | Lag Order | p-Value | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adding evaluation indicators (external variable validation) | TG is not the Granger cause of TE | 5.7668 | 1 | 0.056 * | reject |

| None of the variables are the Granger cause of TE | 5.7668 | 1 | 0.056 * | reject | |

| TE is not a Granger cause of TG | 14.554 | 1 | 0.001 *** | reject | |

| None of the variables are the Granger cause of TG | 14.554 | 1 | 0.001 *** | reject |

| Methods | Variant | LLC Testing | IPS Testing | Test Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Changing the measurement of variables | TE | −21.8969 (0.0000) *** | −10.5720 (0.0000) *** | smooth |

| TG | −18.8040 (0.0000) *** | −6.2655 (0.0000) *** | smooth |

| Methods | Lag Order | AIC | BIC | HQIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Changing the measurement of variables | 1 | −7.55115 * | −6.52316 * | −7.13589 * |

| 2 | −7.01668 | −5.80269 | −6.52473 | |

| 3 | −7.06705 | −5.61406 | −6.47688 |

| Methods | Test Method | Test Statistics | Statistical Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Changing the measurement of variables | Kao test | Modified Dickey–Fuller t | −9.1767 | 0.0000 *** |

| Dickey–Fuller t | −11.8865 | 0.0000 *** | ||

| Augmented Dickey–Fuller t | −6.055 | 0.0000 *** | ||

| Unadjusted modified Dickey–Fuller t | −9.424 | 0.0000 *** | ||

| Unadjusted Dickey–Fuller t | −11.9367 | 0.0000 *** | ||

| Pedroni test | Modified Phillips–Perron t | 1.6368 | 0.0508 * | |

| Augmented Dickey–Fuller t | −11.6856 | 0.0000 *** | ||

| Phillips–Perron t | −11.731 | 0.0000 *** | ||

| Westerlund test | Variance ratio | −1.5493 | 0.0606 * |

| Methods | Original Hypothesis | Chi2 Statistic | Lag Order | p-Value | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Changing the measurement of variables | TG is not the Granger cause of TE | 9.0169 | 1 | 0.003 *** | reject |

| None of the variables are the Granger cause of TE | 9.0169 | 1 | 0.003 *** | reject | |

| TE is not a Granger cause of TG | 8.3025 | 1 | 0.004 *** | reject | |

| None of the variables are the Granger cause of TG | 8.3025 | 1 | 0.004 *** | reject |

| Methods | Variant | LLC Testing | IPS Testing | Test Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shortening the sample study period | TE | −27.0843 (0.0000) *** | −18.5368 (0.0000) *** | smooth |

| TG | −22.4453 (0.0000) *** | −15.4881 (0.0000) *** | smooth |

| Methods | Lag order | AIC | BIC | HQIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shortening the sample study period | 1 | −12.1535 * | −10.8576 * | −11.6272 * |

| 2 | −11.8658 | −10.2737 | −11.2191 | |

| 3 | −11.1211 | −9.10591 | −10.3074 |

| Methods | Test Method | Test Statistics | Statistical Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shortening the sample study period | Kao test | Modified Dickey–Fuller t | −0.0127 | 0.4949 |

| Dickey–Fuller t | −4.3309 | 0.0000 *** | ||

| Augmented Dickey–Fuller t | 0.6188 | 0.268 | ||

| Unadjusted modified Dickey–Fuller t | −4.6545 | 0.0000 *** | ||

| Unadjusted Dickey–Fuller t | −7.2596 | 0.0000 *** | ||

| Pedroni test | Modified Phillips–Perron t | 3.399 | 0.0003 *** | |

| Augmented Dickey–Fuller t | −7.3616 | 0.0000 *** | ||

| Phillips–Perron t | −15.4064 | 0.0000 *** | ||

| Westerlund test | Variance ratio | 2.5294 | 0.0057 *** |

| Methods | Original Hypothesis | Chi2 Statistic | Lag Order | p-Value | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shortening the sample study period | TG is not the Granger cause of TE | 8.3492 | 1 | 0.004 *** | reject |

| None of the variables are the Granger cause of TE | 8.3492 | 1 | 0.004 *** | reject | |

| TE is not a Granger cause of TG | 8.2178 | 1 | 0.004 *** | reject | |

| None of the variables are the Granger cause of TG | 8.2178 | 1 | 0.004 *** | reject |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, N.; Weng, G. The Coordinated Relationship Between the Tourism Economy System and the Tourism Governance System: Empirical Evidence from China. Systems 2025, 13, 301. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13040301

Wang N, Weng G. The Coordinated Relationship Between the Tourism Economy System and the Tourism Governance System: Empirical Evidence from China. Systems. 2025; 13(4):301. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13040301

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Ning, and Gangmin Weng. 2025. "The Coordinated Relationship Between the Tourism Economy System and the Tourism Governance System: Empirical Evidence from China" Systems 13, no. 4: 301. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13040301

APA StyleWang, N., & Weng, G. (2025). The Coordinated Relationship Between the Tourism Economy System and the Tourism Governance System: Empirical Evidence from China. Systems, 13(4), 301. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13040301