Abstract

From the perspective of the talent supply chain, this paper employs evolutionary game theory to study the decision-making behaviors of university graduates’ employment-related participants, establishes a tripartite evolutionary game model of enterprises, graduates, and universities based on prospect theory, and analyzes the main factors affecting the system game strategy by combining numerical simulation. The evolutionary game theory is a theory that integrates game theory with the analysis of dynamic evolutionary processes, studying the strategy selection and dynamic equilibrium of bounded rational participants in complex environments. The findings are as follows: (1) The decision-makers influence and promote each other, and universities play a very important role in promoting the employment of graduates. (2) In the case of random initial probability, when the additional profit of each decision-maker is greater than their cost, enterprises, graduates, and universities can realize the ideal model of “recruitment, participation in recruitment, active employment assistance”. The higher the initial probability, the faster the system reaches a steady state. (3) Enhancing the risk perception of enterprises, graduates, and universities has a dual effect on the employment ecosystem. (4) The behavioral strategies of enterprises, graduates, and universities are affected by many factors, such as the initial probability, loss aversion degree, profit and loss sensitivity degree, talent loss risk, cost, and unemployment risk.

1. Introduction

Employment stands as the most fundamental component of people’s livelihood. University graduates are a precious talent resource for countries and the key group for stabilizing employment. The employment of university graduates is a systematic project that concerns the national economy and people’s livelihood, as well as national stability. In recent years, the number of university graduates in China has repeatedly reached new highs, posing significant pressure on overall employment. At the same time, structural employment contradictions are prominent, with mismatches between the supply of human resources and job demands. On the one hand, issues such as difficulties in employment, decreased employment intention, and reduced employment rates of university graduates have become increasingly prominent, leading to phenomena like “slow employment” and “waiting for employment”. For instance, according to the “2024 University Students’ Employability Research Report” released by Zhaopin Limited (a leading career platform in China), the proportion of “slow employment” among the 2024 graduating university students has increased from 18.9% in 2023 to 19.1%. On the other hand, as the economic downward pressure increases, the demand for university graduates by enterprises continues to decline, and the number of recruitment plans has been significantly reduced. However, some industries are facing significant labor shortages, highlighting structural labor issues such as difficulties in recruiting and retaining workers [1,2,3,4]. Simultaneously, as the main front for talent cultivation, universities also play a crucial role in promoting high-quality and full employment for university graduates (hereinafter referred to as “graduates”). They should analyze the situation with clarity, study employment measures, strengthen employment priority policies, adjust the mechanism for cultivating employment abilities, improve the career guidance system for graduates, and enhance the fundamental support and assistance for the graduates’ employment [5,6]. In view of this, under the current severe employment situation, it is urgent to conduct a systematic study on the employment issue of university graduates so as to contribute to the promotion of high-quality full employment and economic and social stability.

It is necessary to achieve the efficient allocation and utilization of talent, enhance corporate performance, elevate human resource management standards, and boost competitiveness, thereby addressing structural employment contradictions. In 2008, Professor Peter Cappelli from the Wharton School combined supply chain ideas with human resource management and first proposed the concept of the talent supply chain [7,8]. The talent supply chain refers to the network chain structure formed by upstream and downstream enterprises involved in the activities of providing talents to end-users in the process of talent flow. After this concept was proposed, scholars also carried out further research. For instance, Makarius and Srinivasan (2017) developed a comprehensive model of talent supply chain management (TSCM) that applies concepts from the field of supply chain management to manage the development and flow of talent, further describing how organizations can use TSCM to strengthen ties with talent suppliers and thus meet their workforce needs through individuals with the skills needed to succeed [9]. Based on the research of Makarius and Srinivasan, Birou and Van Hoek (2022) aimed to focus on efforts within companies to develop supply chain talent, with a particular focus on the role executives can play in this process. The findings show the critical impact of the personal and broad engagement of senior executives and their leadership teams on talent development in the supply chain [10]. Universities, graduates, and enterprises, as the supply and demand sides in the talent market, can also introduce the concept of talent supply chain management. By operating the talent supply process in a chain-like manner, they can achieve dynamic optimization of talent supply, rapidly complete the matching of talents to positions, and maximize the value of existing human resources, ultimately solving the employment issue for graduates. Therefore, taking the talent supply chain as an entry point to study the employment problem of graduates is of great significance for improving the quality of talent cultivation in universities, enhancing the employment level of graduates and the operational level of enterprises, and promoting high-quality and full employment.

The literature research related to this paper mainly focuses on two aspects: the evolutionary game of different employment groups and the application of prospect theory. Current research on the evolutionary game of different employment groups primarily targets groups such as governments, migrant workers, online employment platform enterprises, people with disabilities, and graduate students. It centrally discusses issues such as government skills training strategies, employment promotion policies for people with disabilities, the collaborative governance of online platform employment, anti-collusion and anti-monopoly measures in the employment market, and employment choice strategies for graduates. For example, in the area of rural labor migration, Liu et al. (2015) built an evolutionary game prediction model for rural labor migration, taking into account both economic and social factors, to analyze the long-term trends of rural labor migration [11]. For the employment situation of graduates and the recruitment policy of enterprises, Dong (2018) conducted research on the difficult employment situation of university students using an evolutionary game model and concluded that when the signing probability of fresh graduates exceeds a specific value, universities tend to provide information platforms and venues for enterprises and fresh graduates [12]. Focusing on the employment situation of disabled individuals, Li et al. (2020) established a dynamic evolutionary model of the interaction process between disabled individuals and employers based on evolutionary game theory and policies promoting the employment of disabled individuals [13]. In order to broaden the employment channel and standardize the employment form of the network platform, Peng and Hou (2023) constructed an evolutionary game model for the “platform organization–platform enterprise” system in network platform employment, analyzing the control of platform organizations over platform enterprises and employment governance under the new employment forms by introducing laborers as a third party [14]. Based on Dong and Peng, Ma and Yang (2024) utilized evolutionary game theory to construct a cooperation matrix for talent cultivation among governments, enterprises, and university research institutions. They systematically explained and analyzed the decision-making and strategic reversal processes in tripartite cooperation for talent cultivation [15]. From the perspective of balancing the interests of supply and demand entities in work-related injury insurance coverage, Xiao and Li (2024) targeted crowdsourcing riders, a group characterized by high occupational injury risks and weak subordination, and constructed a tripartite evolutionary game model involving instant delivery platforms, crowdsourcing riders, and the government. They explored the inherent mechanisms behind the incomplete coverage dilemma of work-related injury insurance for crowdsourcing riders and proposed specific measures to facilitate their participation in insurance coverage [16]. To conclude, we can acknowledge the contributions of Liu, Dong, Li, Peng, and other researchers in the field of evolutionary game theory applied to the employment issues of various groups, including governments, migrant workers, platform enterprises, individuals with disabilities, etc. However, there is still a notable lack of studies that analyze the employment issue of university graduates from the perspective of the talent supply chain using a tripartite evolutionary game framework involving enterprises, graduates, and universities. Therefore, building on previous studies, this paper adopts the evolutionary game theory approach from the talent supply chain perspective, incorporates universities into the employment decision-making support system, and further enriches the dimensions of the employment decision-making model. It explores the evolutionary game paths and decision-making behaviors, such as employment and recruitment, etc., of different decision-makers under various scenarios.

Furthermore, studies on the employment issue of university graduates have largely rested on the presumption of complete rationality among all participating entities, neglecting the inherent bounded rationality of decision-makers involved in the employment and recruitment process. In actuality, decision-makers often exhibit bounded rather than complete rationality. From the perspective of the talent supply chain, the employment game of graduates is composed of the risk perceptions and behavioral decisions of enterprises, graduates, and universities. Each participating party exhibits subjective perceptions of benefits, risks, and information when facing environmental uncertainties and information asymmetries, leading to deviations in behavioral decisions and thus preventing the achievement of optimal decision-making outcomes [17]. In light of this, this paper introduces the prospect theory proposed by Kahneman and Tversky in 1979 into the field of employment decision-making, effectively explaining how decision-makers often base their employment, recruitment, and other related behaviors on subjective judgments in uncertain environments [18]. Currently, prospect theory has been applied in various fields such as supply chain optimization, risk management, and decision analysis. For instance, in the context of improving the inland shipping environment, Lang et al. (2021) developed an evolutionary game model based on prospect theory to study the interactive mechanism of behavioral strategy choices among upstream and downstream governments and shipping companies [19]. Considering the impact of decision-makers’ subjective preferences on energy structure transformation, Xin-Ping et al. (2023) incorporated prospect theory into evolutionary game analysis to build an evolutionary game model involving government regulators and energy consumers, analyzing the dynamic evolution of various game participants [20]. Based on the research of Lang and Xin-Ping, focusing on the field of information-sensitive e-waste recycling, Wang et al. (2024) combined evolutionary game theory with prospect theory to analyze the evolutionary game process between consumers and recyclers [21]. In terms of enterprise green technology innovation research, Wu et al. (2025) constructed a complex network evolution model based on prospect theory to investigate the impact of subjective factors such as risk preference and loss aversion on the adoption of green technology innovation in different network environments [22].

In summary, despite significant achievements in existing research, studies on the employment of university graduates remain inadequate in several aspects. First, most research on employment issues is grounded in expected utility theory, failing to fully capture the limited rationality and decision-making biases of decision-makers. Second, current research has not incorporated enterprises, graduates, and universities into an employment decision-support system, nor has it systematically analyzed the issue from the perspective of the talent supply chain to achieve optimal evolutionary strategies for the supply chain system. Addressing these deficiencies, this paper, from the perspective of the talent supply chain and based on the premise of the bounded rationality of decision-makers, conducts a systematic study on the decision-making behaviors of relevant stakeholders in the employment of university graduates and constructs an evolutionary game model involving enterprises, graduates, and universities. Furthermore, this study examines the impact of factors such as loss aversion, profit and loss sensitivity, talent loss risk, unemployment risk, and the risk of reduced social recognition on the evolutionary strategies of decision-makers combined with numerical simulation analysis. The research findings contribute to elucidating the underlying mechanisms and evolutionary patterns of related decisions of enterprise recruitment, university employment assistance, and student active participation in job applications from multiple perspectives. These insights provide decision-making support for promoting the high-quality and full employment of graduates and the healthy development of enterprises.

Compared with previous research, this paper makes two primary contributions. First, based on prospect theory, this paper constructs a tripartite evolutionary game model involving enterprises, graduates, and universities. This model not only considers game players’ decision-making behaviors in the face of risks and uncertainties, such as loss aversion and cognitive biases, but also deeply analyzes the evolutionary paths of these factors on the behavior of different stakeholders in employment decisions. It explores the psychological motivations and subjective emotions behind the decision-making behaviors of stakeholders in the employment of university graduates, filling a gap in the literature on the application of prospect theory in the field of evolutionary game theory concerning employment issues. Second, from the perspective of the talent supply chain, this paper incorporates universities into the employment decision-support system, further enriching the dimensions of the model. It analyzes the evolutionary game paths of various decision-makers under different scenarios, identifies the factors influencing game outcomes through numerical simulations, and derives relevant suggestions and management implications.

2. Assumptions and Notation

2.1. Model Assumptions

From the perspective of the talent supply chain, this paper investigates the dynamic evolutionary process of enterprise recruitment policies, graduate job application decisions, and university employment assistance policies based on prospect theory. The following assumptions are proposed in this paper:

Assumption 1.

The employment game of university graduates primarily involves three types of entities, i.e., enterprises, graduates, and universities, from the perspective of the talent supply chain. In this group game, enterprises, as the demand side for talent, seek employees who match their job positions via recruitment, and they can choose between the strategies of “recruitment” and “non-recruitment”. Graduates, as the supply side of talent, look for ideal jobs that align with their educational background and abilities by participating in recruitment, and they have the options of “participation in recruitment” and “non-participation in recruitment”. Universities, as talent cultivation bases and participants in the supply chain, provide support and guidance to enterprises and graduates in aspects such as recruitment and job applications through various employment assistance policies, aiming to improve their employment levels, reputation, and the quality of incoming students. They can choose between the strategies of “active employment assistance” and “passive employment assistance”.

Assumption 2.

Due to the inherent uncertainty and complexity of the employment environment, various decision-making entities in the game exhibit significant differences in information acquisition and analysis, knowledge levels, capabilities, risk perception, and preferences. These disparities influence their subjective judgments of profits and losses, subsequently affecting their strategic choices and system stability. Decision-makers “assign” new values to objective profits and losses based on their psychological cognitions and risk preferences, continuously adjusting their decision-making behaviors. This aligns with the concept of evolutionary game theory, where behavioral decisions influence each other, and actors continuously adjust their strategies. However, traditional evolutionary game models construct payment functions based on objective profits and losses, neglecting the psychological characteristics of decision-makers. Prospect theory, premised on bounded rationality, emphasizes that decision-makers’ strategic choices are primarily based on their subjective evaluations and perceived values of profits and losses, rather than actual outcomes, thereby addressing the shortcomings of traditional models [17,18,19,20,21]. Therefore, this paper integrates prospect theory with evolutionary game theory to more objectively describe the decision-making tendencies and behavioral evolution of enterprises, graduates, and universities under the influence of psychological perceptions. This integration aims to explain issues such as “slow employment, unemployment, low recruitment willingness, and decreased recruitment numbers” faced by graduates during the employment process.

Let represent the decision-maker’s perceived value of profits and losses, which is determined by the value function and the weighting function and reflects how employment participants, including enterprises, graduates, and universities, continuously adjust their employment or recruitment behaviors based on their psychological cognitions and risk preferences during the employment game process.

Specifically, denotes the decision-maker’s perception of profits and losses, which is the relative value of their actual worth compared to a reference point, namely , where serves as the reference point. The value function is expressed as the following equation, indicating that for participants in the employment game, the perceptions of losses and profits are different, and people tend to be more averse to loss, such as unemployment risk, talent loss risk, recruitment cost, etc., which is consistent with the objective world.

In Equation (2), reflects the loss of outcome relative to the reference point , while reflects the relative profit. and are used to measure the decision-maker’s perceived sensitivity to profits and losses, respectively, with larger values indicating greater sensitivity. These coefficients determine the slopes of the value function in the profit and loss regions, thereby reflecting the decision-maker’s psychological reaction intensity to different outcomes. represents the loss aversion degree of the decision-maker, and referring to the research of Lang, Xin-Ping, and Wang et al., it is commonly assumed that , indicating that the decision-maker is more sensitive to losses than to profits [19,20,21]. This parameter setting aims to capture the widespread loss aversion psychology of decision-makers in the real world, ensuring that the model accurately describes the psychological and behavioral characteristics of decision-makers when facing employment-related decisions. This psychological phenomenon is widely manifested in various domains, such as financial investment and consumer behavior.

The weighting function is expressed as follows:

represents the objective probability of the occurrence of event outcome , denotes the curvature of the decision weight function curve, and .

This paper introduces prospect theory to characterize the mechanism of subjective factors such as perceived value sensitivity and loss aversion on game strategies. Following the approach of references [21,22,23,24,25], the reference point is adopted to measure the perceived value of objective profits and losses. The subjective probability of event occurrence for the employment-related actors is set to to make the model more clearly reflect the reaction mechanism of decision-makers to profits and losses. Thus, and . Choosing as the reference point means that decision-makers consider any positive outcome as a profit and any negative outcome as a loss. This setting simplifies the model, making the definition of profits and losses clear and straightforward. At the same time, it also reflects that in the absence of specific expectations or goals, decision-makers tend to use the current status (i.e., the point) as a benchmark for evaluating future outcomes.

Assumption 3.

The normal profit of enterprises in the absence of any specific circumstances is . If the enterprises adopt the recruitment strategy, the additional profit obtained is , primarily including benefits such as acquiring high-quality talent and enhancing the corporate image. The matching rate of graduates who fit the required job positions and are found by the enterprises through recruitment is . When universities adopt the active employment assistance strategy, the change in the matching rate of graduates recruited by the enterprises is , where , , and . Therefore, when universities take the active employment assistance strategy and graduates participate in recruitment, the additional profit for the enterprises is . When graduates do not participate in recruitment, the additional profit for the enterprises is . When universities take the passive employment assistance strategy and graduates participate in recruitment, the additional profit for the enterprises is . When graduates do not participate in recruitment, the additional profit for the enterprises is . The recruitment cost of enterprises is . When universities adopt the active employment assistance strategy, the change in the recruitment cost of enterprises is , . The talent loss risk incurred by the enterprise when graduates participate in recruitment but the enterprise chooses not to recruit is .

Assumption 4.

The normal profit of graduates without any special circumstances is . The additional profit of graduates when participating in enterprise recruitment is , which mainly includes the employment opportunities, value realization, social status improvement, and other benefits they obtain via participating in recruitment. The matching rate of graduates finding ideal positions that match their educational background and abilities through recruitment is . When universities adopt the active employment assistance strategy, the change in the matching rate of graduates’ ideal positions through recruitment is , where , , and . Therefore, when universities provide active employment assistance, the additional profit of graduates under enterprise recruitment is , and the additional profit of graduates without enterprise recruitment is . When universities provide passive employment assistance, the additional profit of graduates under enterprise recruitment is , and the additional profit of graduates without enterprise recruitment is . The cost of graduates participating in enterprise recruitment is . When universities adopt the active employment assistance strategy, the change in the cost of graduates participating in recruitment is , . The unemployment risk faced by graduates when they do not participate in enterprise recruitment is .

Assumption 5.

The normal profit of universities without any special circumstances is denoted as . The additional profit obtained by universities when adopting active employment assistance is , which primarily includes benefits such as enhanced school reputation and improved student quality. When universities adopt the active employment assistance strategy, the improved employment level coefficient of graduates is , and the improved recruitment level coefficient of enterprises is , where and . Therefore, when both enterprises and graduates participate, the additional profit of universities is denoted as . When enterprises do not conduct recruitment, the additional profit of universities is denoted as . And when graduates do not participate in recruitment, the additional profit of universities is denoted as . The basic input cost of universities is , and the additional input cost incurred when universities adopt the active employment assistance is , . The risk of reduced social recognition faced by universities when adopting passive employment assistance is .

2.2. Notation

Based on the above assumptions, the relevant parameters and their descriptions are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Notation.

3. Construction of the Tripartite Evolutionary Game Model and Stability Analysis of Unilateral Behavior Strategies

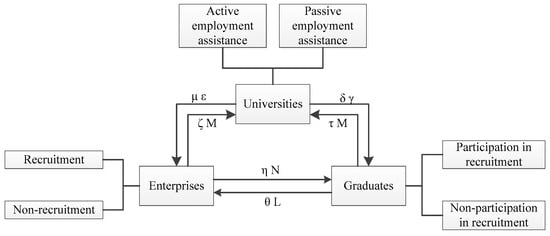

3.1. Construction of the Tripartite Evolutionary Game Model

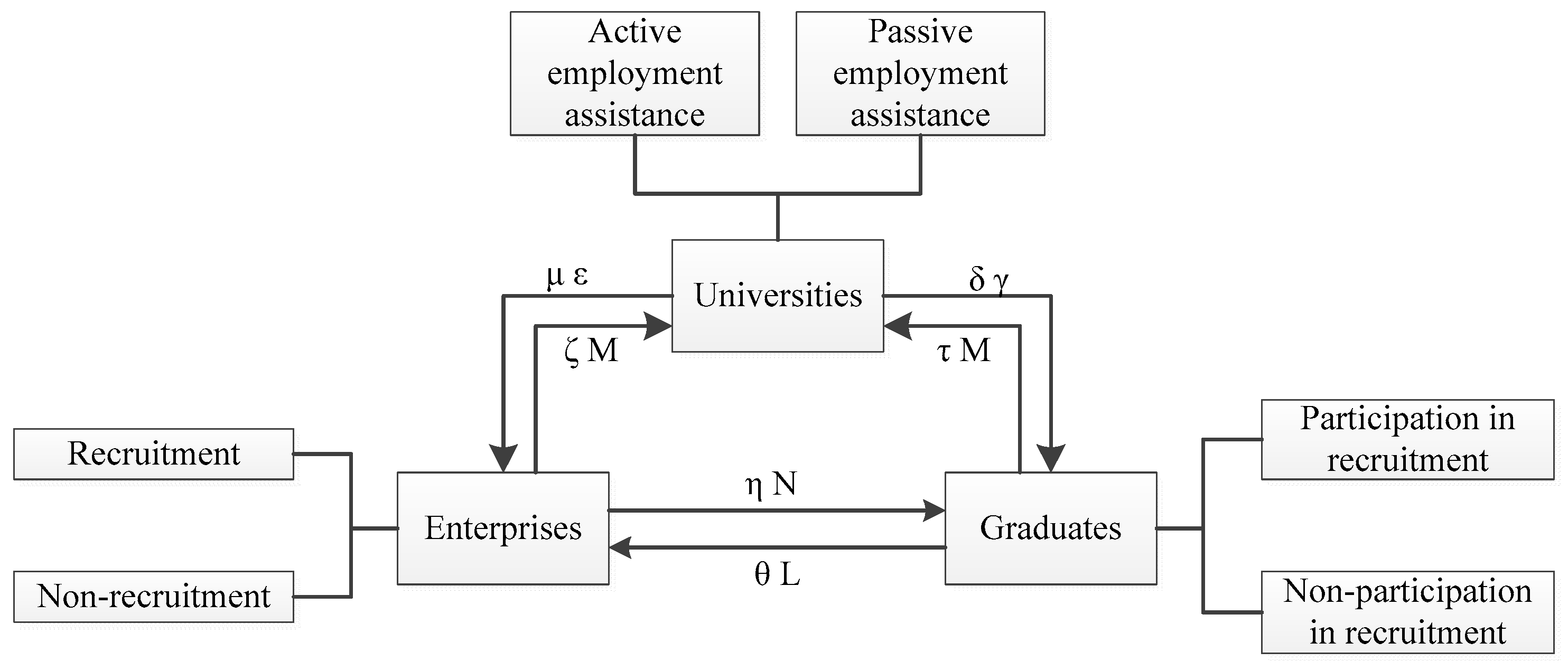

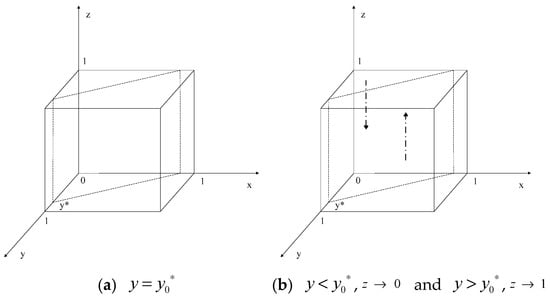

According to the above model assumptions and parameter settings, this paper constructs the behavioral strategy relationship diagram of each decision-making body in the talent supply chain, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Behavioral strategy relationship of each decision-maker in the talent supply chain.

Based on the behavioral definitions and explanations of the game players in the previous section, this paper assumes that the probabilities of the enterprise group choosing the “recruitment” and “non-recruitment” strategies are and , respectively. The probabilities of the graduate group choosing the “participation in recruitment” and “non-participation in recruitment” strategies are and , respectively. And the probabilities of the university group choosing the “active employment assistance” and “passive employment assistance” strategies are and , respectively. The determined profit and loss parameters, which are only related to the game players themselves, remain unchanged, including , , , , , and [23,24,25,26]. The uncertain profit and loss are represented using prospect theory to indicate the perceived value of profit and loss, including , , , , and for enterprises, , , , , and for graduates, and , , , , and for universities. Based on this, the payment matrix for this evolutionary game is constructed, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Strategy combination and payment matrix of evolutionary game.

3.2. Stability Analysis of Enterprises’ Behavior Strategy

From the payment matrix, the expected revenue of enterprises choosing the recruitment strategy is , and the expected revenue of enterprises choosing the non-recruitment strategy is . The expected revenue refers to the average amount of profits an individual anticipates obtaining under a specific strategy. It serves as one of the key drivers for individual strategy selection, with individuals typically inclined to choose strategies that offer higher expected revenues.

By combining Equation (1) with Equation (5), the average revenue of enterprises can be obtained, as shown in Equation (6). Average revenue reflects the mean earnings of individuals in a group, serving as a benchmark for assessing overall group profitability and strategy effectiveness.

According to the Malthusian equation, we can derive the replicator dynamic equation of enterprises. The replicator dynamic equation quantifies the difference between the payoff received by individuals adopting a specific strategy and the average expected payoff of all strategies in the group. It outlines how the prevalence of different strategies within a group changes over time under specific conditions.

Based on the stability theorem of differential equations and the properties of the Evolutionary Stable Strategy (ESS), the ESS point must be robust to small perturbations [26], meaning that to achieve the ESS point, conditions and must be satisfied. Similarly, this property also applies to graduates and universities. On this basis, we first analyze the evolutionary path and stability of enterprises’ behavioral strategies and propose Proposition 1.

Proposition 1.

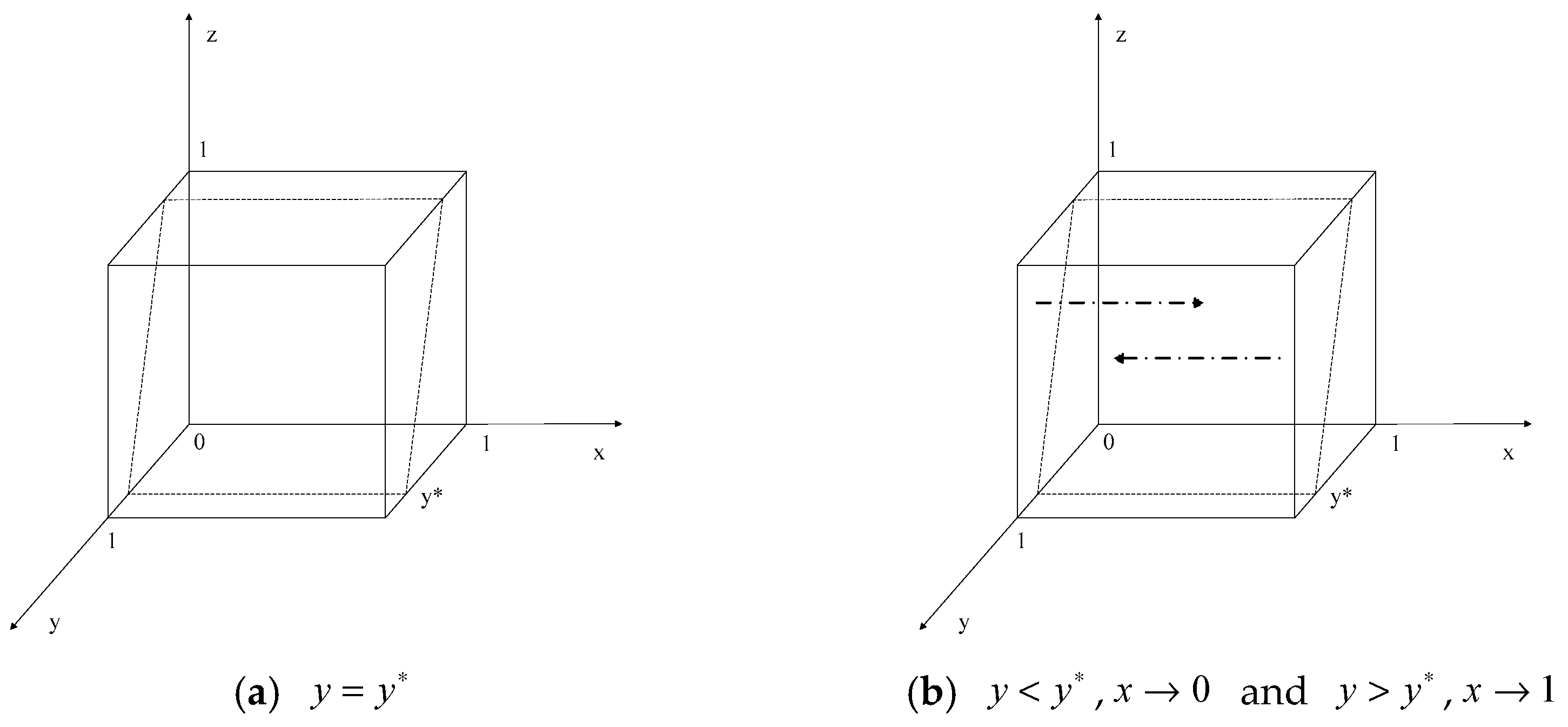

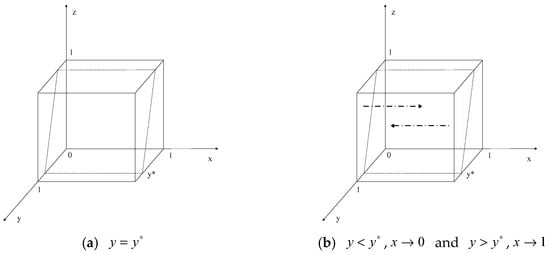

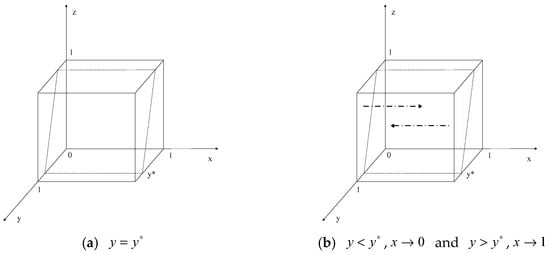

When the probability of graduates choosing the “participation in recruitment” strategy is , then , and at this time, lies within the range of , and the enterprises’ behavioral strategies are all in a stable state. When the probability of graduates choosing the “participation in recruitment” strategy is , only and are stable points, where . The phase diagram of enterprises’ evolution strategies is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The phase diagram of enterprises’ evolution strategies.

Proof of Proposition 1.

Let , and we can obtain . Because , .

Let , and we can derive , , and .

The outcome is as follows:

(1) If , meaning that it is in a stable state for all , the probability of enterprises choosing the “recruitment” strategy versus the “non-recruitment” strategy will remain unchanged.

(2) If , two stable points and are obtained. Furthermore, can be divided into two scenarios:

(a) When , , , and . Therefore, is the ESS.

(b) When , , , and . Therefore, is the ESS. □

From Figure 2, we can observe that when , all are in a stable state. This means that when the proportion of graduates participating in recruitment reaches a certain critical threshold, the recruitment strategy of enterprises will not be significantly influenced by the strategic choices of the graduate group. Enterprises can choose any recruitment strategy (ranging from no recruitment to full recruitment) while maintaining stability. When , is the stable point, indicating that enterprises tend to adopt the “non-recruitment” strategy. This is because the proportion of graduates participating in recruitment is relatively low, and enterprises may perceive the cost of recruitment to outweigh the benefits, making the choice of no recruitment a more stable strategy. When , is the stable point, meaning that enterprises tend to adopt the “recruitment” strategy. At this point, the proportion of graduates participating in recruitment is relatively high, and the benefits of recruitment outweigh the costs, making recruitment a more stable strategy.

Therefore, from Proposition 1, we can derive that enterprises should closely monitor whether the proportion of graduates participating in recruitment reaches the critical threshold. This threshold serves as a watershed for changes in recruitment strategies. Exceeding or falling below this threshold will lead to significant changes in recruitment strategies. When the proportion of graduates participating in recruitment is below the threshold, enterprises should carefully evaluate the necessity of recruitment and dynamically adjust their recruitment strategies to avoid resource waste caused by excessive recruitment costs. Conversely, when the participation proportion exceeds the threshold, enterprises should actively expand their recruitment scale to meet talent demands and seize market opportunities. Additionally, the proportion of graduates participating in recruitment may be influenced by various factors such as economic conditions and industry trends. Enterprises should maintain flexibility and adjust their recruitment strategies in a timely manner based on changes in the external environment to remain competitive.

3.3. Stability Analysis of Graduates’ Behavior Strategy

The expected revenue of graduates choosing the “participation in recruitment” strategy is , and the expected revenue of graduates choosing the “non-participation in recruitment” strategy is .

By combining Equation (8) with Equation (9), we can derive the average revenue of graduates.

According to the Malthusian equation, we can obtain the replicator dynamic equation of graduates.

Based on the stability theorem of differential equations and the properties of the ESS, to achieve the ESS point, conditions and must be satisfied. On this basis, we analyze the evolutionary path and stability of graduates’ behavioral strategies and propose Proposition 2.

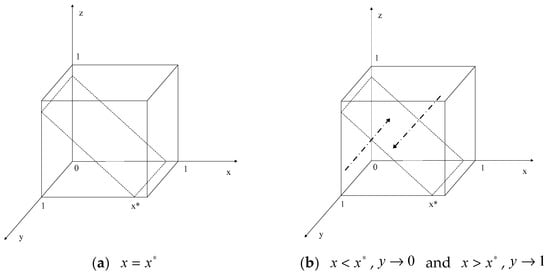

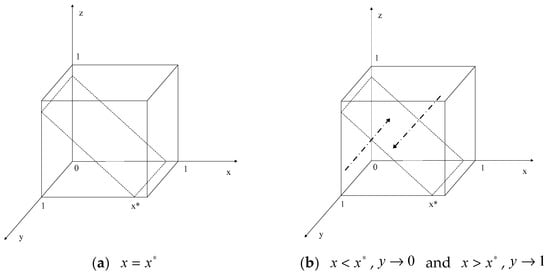

Proposition 2.

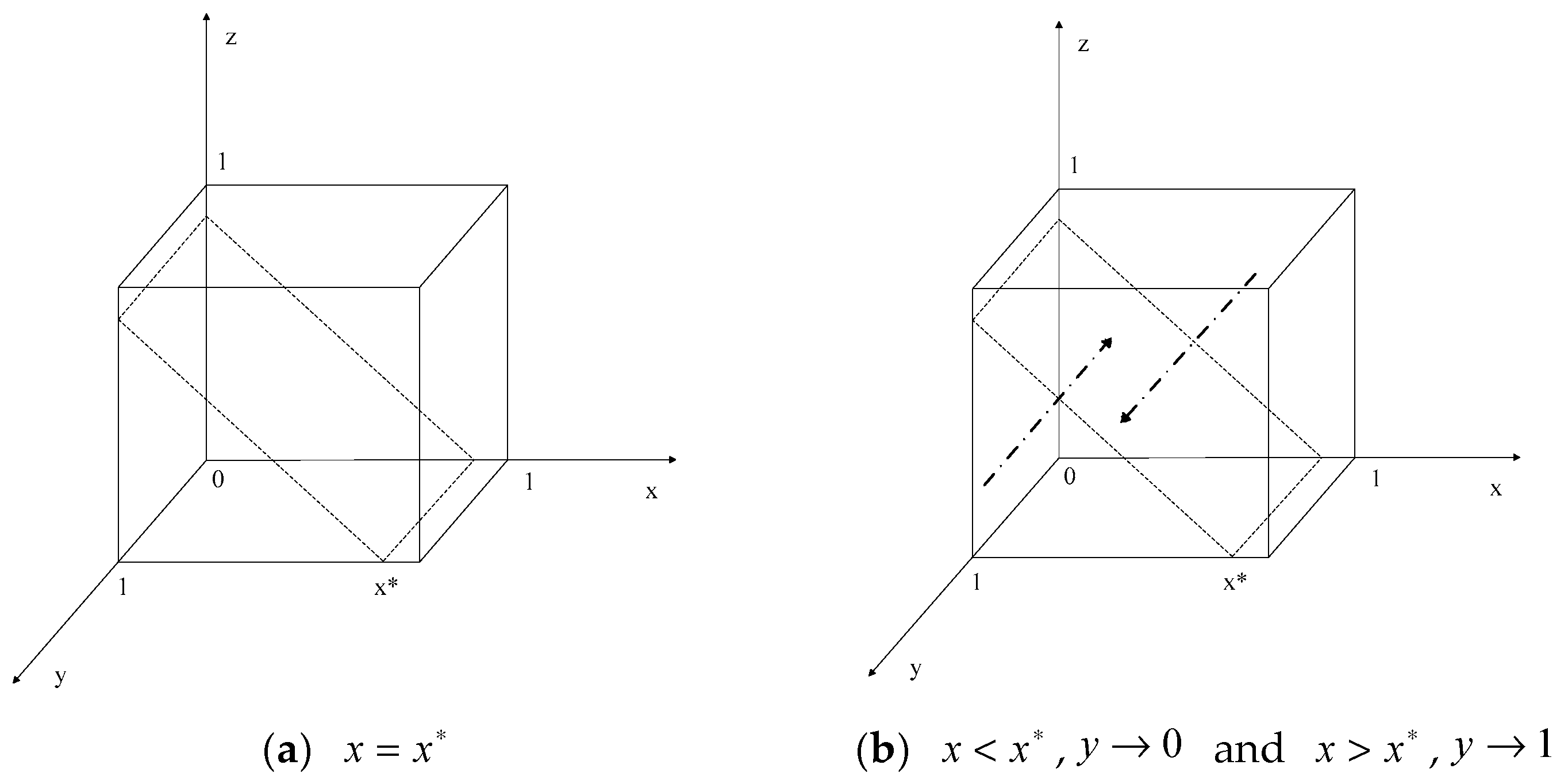

When the probability of enterprises choosing the recruitment strategy is , then , and at this time, lies within the range of , and the graduates’ behavioral strategies are all in a stable state. When the probability of enterprises choosing the recruitment strategy is , only and are stable points, where . The phase diagram of graduates’ evolution strategies is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The phase diagram of graduates’ evolution strategies.

Proof of Proposition 2.

Let , and we can obtain . Because , .

Let , and we can derive , , and .

The outcome is as follows:

(1) If , meaning that it is in a stable state for all , the probability of graduates choosing the “participation in recruitment” strategy versus the “non-participation in recruitment” strategy will remain unchanged.

(2) If , two stable points and are obtained. Furthermore, can be divided into two scenarios:

(a) When , , , and . Therefore, is the ESS.

(b) When , , , and . Therefore, is the ESS. □

From Figure 3, it can be seen that when , all are in a stable state. This means that when the probability of recruitment strategy selection by enterprises reaches a certain critical threshold, the graduates’ strategy selection will not be significantly affected by the enterprises’ behavior, and graduates can choose any strategy (ranging from complete non-participation to full participation in recruitment) to maintain stability. When , is the stable point, indicating that graduates tend to choose the “non-participation in recruitment” strategy. This is because the probability of enterprise recruitment is low, and graduates may believe that the expected benefits of participating in recruitment (such as job opportunities) do not outweigh the costs (such as time and energy). Therefore, choosing not to participate in recruitment is a more stable strategy. Conversely, is the stable point, indicating that graduates tend to choose the “participation in recruitment” strategy. At this point, the probability of enterprise recruitment is high, and graduates believe that the expected benefits of participating in recruitment outweigh the costs. Thus, choosing to fully participate in recruitment is a more stable strategy.

From Proposition 2, it is known that the enterprise’s recruitment strategy directly affects graduates’ willingness to participate. Enterprises should adjust their recruitment strategies to guide the behavior of graduate groups. For example, when enterprises wish to attract more graduates to participate in recruitment, they can increase recruitment positions and frequency, making the recruitment probability exceed the threshold, thereby motivating graduates to actively participate. In addition, enterprises need to pay attention to the external effects of their recruitment strategies. Not only do they impact their own talent acquisition, but they also have external effects on the behavior of graduate groups. Enterprises should be aware that when the recruitment probability is below the threshold, it may lead to a decrease in graduates’ confidence in the recruitment market, further reducing their willingness to participate. Therefore, when formulating recruitment strategies, enterprises should consider their impact on the entire recruitment ecosystem. And graduates need to rationally assess the probability of enterprise recruitment and adjust their strategies accordingly. When the probability of enterprise recruitment is low, graduates should rationally evaluate the costs and benefits of participating in recruitment to avoid blindly investing resources. When the probability of enterprise recruitment is high, graduates should actively prepare and seize employment opportunities. At the same time, enterprises should focus on the long-term stability of their recruitment strategies and avoid frequent fluctuations. Frequently changing recruitment strategies may lead to a decrease in graduates’ trust in enterprises, further affecting their willingness to participate in recruitment. By formulating long-term recruitment plans, enterprises can maintain the stability of their recruitment strategies and provide graduates with clearer expectations.

3.4. Stability Analysis of Universities’ Behavior Strategy

The expected revenue of universities choosing the “active employment assistance” strategy is , and the expected revenue of universities choosing the “passive employment assistance” strategy is .

By combining Equation (12) with Equation (13), we can derive the average revenue of universities.

According to the Malthusian equation, we can obtain the replicator dynamic equation of universities.

Based on the stability theorem of differential equations and the properties of the ESS, to achieve the ESS point, conditions and must be satisfied. On this basis, we analyze the evolutionary path and stability of universities’ behavioral strategies and propose Proposition 3.

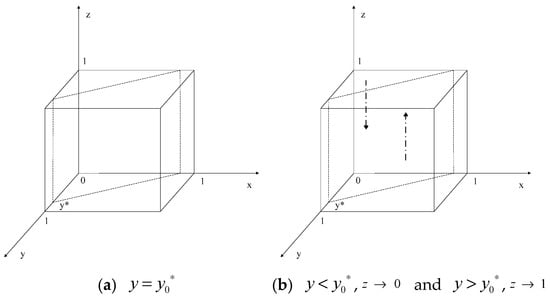

Proposition 3.

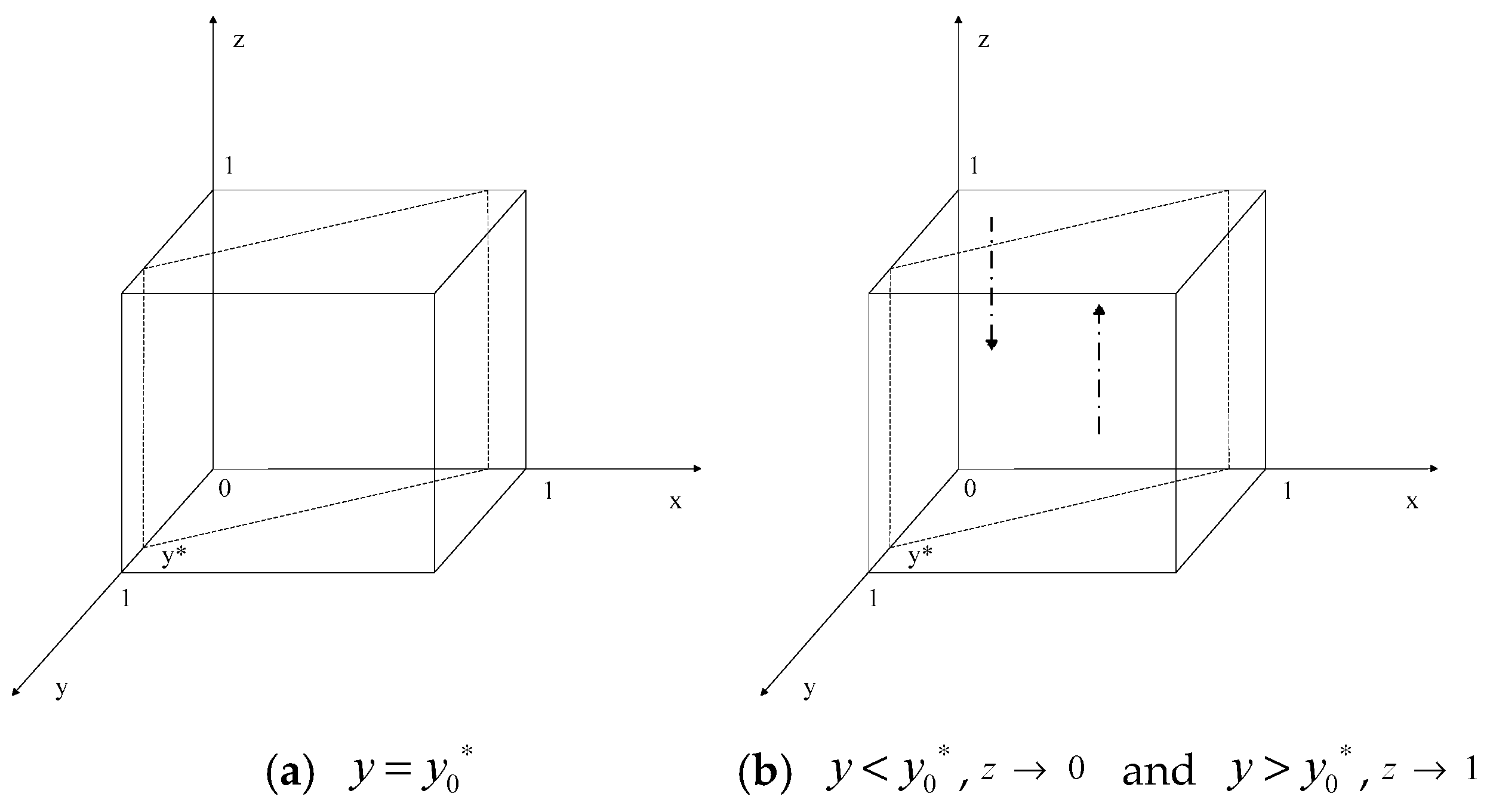

When the probability of graduates choosing the “participation in recruitment” strategy is , then , and at this time, lies within the range of , and the universities’ behavioral strategies are all in a stable state. When the probability of graduates choosing the “participation in recruitment” strategy is , only and are stable points, where . The phase diagram of universities’ evolution strategies is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The phase diagram of universities’ evolution strategies.

Proof of Proposition 3.

Let , and we can obtain . Because , .

Let , and we can derive , , and .

The outcome is as follows:

(1) If , meaning that it is in a stable state for all , the probability of universities choosing the “active employment assistance” strategy versus the “passive employment assistance” strategy will remain unchanged.

(2) If , two stable points and are obtained. Furthermore, can be divided into two scenarios:

(a) When , , , and . Therefore, is the ESS.

(b) When , , , and . Therefore, is the ESS. □

From Figure 4, it can be observed that when , all remain stable. This implies that when the proportion of graduates participating in recruitment reaches a certain critical threshold, the “active employment assistance” strategies of universities are not significantly influenced by the strategic choices of the graduate population. Universities can choose any support strategy (ranging from active employment assistance to passive employment assistance) and maintain stability. When , represents the stable point, indicating that universities tend to adopt the “passive employment assistance” strategy. This is because the proportion of graduates participating in recruitment is low, and universities may believe that the benefits of investing resources in employment support (such as improving employment rates) do not outweigh the costs (such as manpower and material resources). Therefore, choosing to provide passive employment assistance is the more stable strategy. It is specifically noted that when universities adopt the “passive employment assistance” strategy, it refers to providing only basic employment services for graduates, rather than not providing any employment services at all. In this context, universities are considered as participants in the game, and their objective in providing employment assistance to improve graduates’ employment levels is to enhance their overall benefits, primarily including benefits such as school reputation and an improvement in student source quality. Hence, when graduates’ willingness and proportion to participate in recruitment are low, universities will also adjust their level of investment in employment support to mitigate risks. When , is the stable point, indicating that universities tend to adopt the “active employment assistance” strategy. At this point, the proportion of graduates participating in recruitment is high, and universities believe that the benefits of employment assistance outweigh the costs. Thus, choosing to provide active assistance is a stable strategy.

According to Proposition 3, universities should dynamically adjust their employment assistance strategies based on the proportion of graduates participating in recruitment. Additionally, universities should optimize the allocation of employment support resources based on the participation rate of graduates. When the participation rate is low, universities can concentrate resources on solving key issues (such as improving graduate skills and expanding employment channels). When the participation rate is high, universities can expand the scope of support and provide more comprehensive assistance (such as interview training and job information push notifications). Meanwhile, the proportion of graduates participating in recruitment may be affected by various factors such as the economic environment, industry trends, etc. Universities should maintain flexibility and adjust their assistance strategies in time according to changes in the external environment. For example, during economic downturns, universities can help graduates cope with employment pressure by strengthening employment psychological counseling and providing support for entrepreneurship.

4. Stability Analysis of Tripartite Evolutionary Game System

In order to obtain the stability strategy of the dynamic system, this paper assumes that the replicator dynamic equation of the three participants is , i.e.,

We can derive fourteen local equilibrium points, where there are eight pure strategies, i.e., , , , , , , , and , and six mixed strategies, i.e., . According to the theory proposed by Friedman [27], the ESS only emerges in pure strategies, and mixed strategies are inherently unstable in dynamic evolutionary systems. Therefore, we first exclude the six mixed strategies from the equilibrium analysis, and the conditions of these mixed strategies are explained in the subsequent analysis of local equilibrium points. However, while mixed strategies may theoretically exist under certain parameter combinations (e.g., when participants’ perceived costs and profits are perfectly balanced), their practical relevance in real-world employment contexts is limited. This is because employment-related decisions (e.g., recruitment, job-seeking, and employment assistance) are typically driven by bounded rationality and observable market pressures, which push participants toward deterministic choices (pure strategies) rather than probabilistic mixtures. For instance, enterprises facing financial constraints are unlikely to randomly alternate between “recruitment” and “non-recruitment”; instead, they tend to adopt stable strategies based on cost–benefit calculations. Similarly, universities are institutionally incentivized to maintain consistent employment assistance policies. These practical considerations justify the exclusion of mixed strategies in the stability analysis.

This paper employs the Lyapunov indirect method to analyze the stability of the system and derives the Jacobian matrix for the replicator dynamic Equations (7), (11), and (15). Each element of the Jacobian matrix is the first partial derivative of the corresponding replicator dynamic equation with respect to one of the variables. The result is shown in Equation (17). In evolutionary game theory, the Jacobian matrix is a crucial tool that enables researchers to better comprehend and analyze the equilibrium states of games. By utilizing the Jacobian matrix, one can accurately solve for the evolutionarily stable equilibrium points, which represent the long-term stable states of strategy selection in the game. During the process of evolutionary gaming, individuals choose strategies based on their own interests and the decisions of other individuals, while the elements of the Jacobian matrix reflect the payoffs for individuals under different strategy combinations. Through multiple rounds of evolution, individuals gradually learn and adjust their strategies, ultimately reaching a stable equilibrium state, which can be solved using the Jacobian matrix.

where .

The obtained equilibrium points are substituted into the Jacobian matrix , and then, the corresponding eigenvalues of the matrix are solved. The eigenvalues of this Jacobian matrix at different equilibrium points are presented in Table 3, where represents the eigenvalue at the equilibrium point , where and .

Table 3.

The eigenvalues of the Jacobian matrix.

Based on the local stability criterion of the Jacobian matrix, for the tripartite evolutionary game, when all the eigenvalues of the Jacobian matrix are negative, the equilibrium point is the ESS; when all the eigenvalues are positive, the equilibrium point is unstable; and when one or two eigenvalues are positive, the equilibrium point is a saddle point [20]. Any initial point and its evolved point are meaningful only within the three-dimensional space . Furthermore, under mixed strategies, the Jacobian matrix has eigenvalues with different signs, which make the mixed strategies saddle points [19,26]. Therefore, depending on the different ranges of values for the profits, costs, and risks of each participant, the situations can be classified into the following four scenarios:

Scenario 1.

When the additional profits obtained by each participant under different circumstances exceed their costs, and the perceived risks of universities are greater than their perceived costs, i.e., when , , , , , and are satisfied, are not within the three-dimensional space . The stability analysis of the equilibrium points is presented in Table 4, where is the ESS. In this case, due to the high additional benefits and the significant risk perceived by universities, enterprises, graduates, and universities will all adopt active behavior strategies to achieve a win–win–win situation for all three parties.

Table 4.

Local stability analysis of equilibrium points in Scenario 1 and Scenario 2.

For universities, they can establish resource-sharing and cooperation mechanisms, seek financial subsidies and tax incentives to reduce the costs of employment assistance, and also enhance the benefits of such assistance by strengthening university–enterprise cooperation and improving the effectiveness and influence of their support efforts, thereby meeting the conditions of Scenario 1 and achieving a stable strategy of universities adopting positive actions. For example, universities can be encouraged to establish resource-sharing and cooperation mechanisms with enterprises, other universities, and social organizations, reducing their investment in employment assistance through sharing employment information and jointly organizing job fairs. By deepening university–enterprise cooperation through joint training, internships, industry–academia–research collaboration, and other means, the employment quality and employment rate of graduates can be improved, thereby enhancing the benefits of universities’ employment assistance. Additionally, universities should strengthen the promotion and publicity of their support work to enhance its visibility and influence, attracting more enterprises and social resources to participate and create a virtuous cycle.

Scenario 2.

When the additional profits obtained by each participant under various circumstances exceed their costs, and the perceived risks of universities are less than their perceived costs, namely when , , , , , and are satisfied, are still not within the three-dimensional space . The stability analysis of the equilibrium points is shown in Table 4, and remains the ESS. At this point, despite the risks of universities being lower than their costs, all game entities, including enterprises, graduates, and universities, will adopt positive behavioral strategies due to the significant additional profits. It is worth mentioning that the unstable point at this time is , indicating that when the risks of universities are lower than their costs, if both enterprises and graduates choose negative strategies, universities will also not choose the positive behavioral strategies. Therefore, universities can reduce risks by establishing risk-sharing mechanisms and enhancing information sharing and transparency, thereby meeting the conditions of Scenario 2 and enabling universities to adopt proactive employment assistance strategies. For instance, universities can collaborate with enterprises to clarify the responsibilities and obligations of both parties during the recruitment and employment process, as well as the methods and proportions for risk-sharing. This can effectively alleviate the economic and reputational risks that universities may face in the process of employment assistance. By increasing the degree of information sharing in employment assistance work, including the employment status of graduates and the recruitment needs of enterprises, risks arising from information asymmetry can be reduced. Additionally, by increasing the transparency of assistance work and allowing all sectors of society to understand the efforts and achievements of universities in employment assistance, it helps to enhance the credibility and social recognition of universities, thereby achieving harmonious and stable social development.

Scenario 3.

When the additional profits obtained by each participant under various circumstances are less than their costs, and the perceived risks of universities exceed their perceived costs, namely when , , , , , and are satisfied, and are within the three-dimensional space , while , , , and are not within the three-dimensional space . The stability analysis of the equilibrium points , , and is shown in Table 5. At this point, based on the relationship among the additional profits, costs, and risks of enterprises and graduates, Scenario 3 is divided into two sub-scenarios: (a) , , , and and (b) , , , and .

Table 5.

Local stability analysis of equilibrium points in Scenario 3.

From Table 5, it can be concluded that when Scenario 3(a) is satisfied, is the ESS. At this point, due to the high costs of all game entities and the low perceived risks of enterprises and graduates, they tend to choose not to conduct (participate in) recruitment. However, because of the high perceived risks, universities adopt the active employment assistance strategy, providing as much assistance and guidance as possible for graduates and enterprises. When Scenario 3(b) is satisfied, both and are the ESS. Although the additional profits for universities are low, they will still adopt the active employment assistance strategy considering the high risks. Enterprises and graduates, on the other hand, can reach a stable state under both behavior decisions of conducting (participating in) recruitment or not conducting (not participating in) recruitment, based on the relationship among profits, risks, and costs.

In the real world, such scenarios may also emerge. For instance, during significant economic downturns, enterprise recruitment costs increase, graduates face difficulties in finding employment, and universities may also confront heightened risks, primarily encompassing lower employment rates and social recognition. At this juncture, the additional profits of various participants may fall below their costs. Due to the high risks, universities will proactively offer more aggressive employment assistance measures, whereas enterprises and graduate groups may opt not to participate in recruitment, aligning with Scenario 3(a). Conversely, when the economy improves, the costs of all participants decrease or their profits increase, causing the game system to shift towards proactive behavioral strategies, such as the ideal state in Scenario 1. Additionally, policy changes can also alter the equilibrium. For example, government subsidies can reduce enterprise costs or increase employment incentives and subsidies for graduates, which will affect the costs and benefits of all parties. That is, additional profits may exceed costs, leading them to be more willing to participate in recruitment activities and thereby altering their equilibrium state.

Scenario 4.

When the additional profits obtained by each participant under various circumstances are less than their costs, and the perceived risks of universities are less than their perceived costs, namely when , , , , , and are satisfied, the stability analysis of the equilibrium points is conducted, as shown in Table 6. At this point, based on the relationship among the additional profits, costs, and risks of enterprises, graduates, and universities, Scenario 4 is divided into two sub-scenarios: (a) , , , , , , and and (b) , , , , , , and .

Table 6.

Local stability analysis of equilibrium points in Scenario 4.

From Table 6, we can derive that when Scenario 4(b) is satisfied, are within the three-dimensional space , and both and are the ESS. Since the costs of all game entities are higher than their additional profits but lower than the sum of additional profits and risks, the relevant parties will reach a stable state under both behavior decisions of (recruitment, participation in recruitment, active employment assistance) and (non-recruitment, non-participation in recruitment, passive employment assistance), based on the relationship among profits, risks, and costs. When Scenario 4(a) is satisfied, are within the three-dimensional space , and is the ESS. The costs of all game entities are higher than the sum of their additional benefits and risks, leading the relevant parties to choose passive behavior decisions to avoid losses.

5. Numerical Simulation of the Tripartite Evolutionary Game

In order to intuitively observe the asymptotic stability of the ESS in the game model and the influence of parameter changes (including initial probability, prospect theory-related parameters, other parameters, etc.) on the tripartite behavior in the employment process of graduates, the evolution path of the decision-making process of stakeholders is simulated. In this paper, Python 3.9 is used to simulate the game of Scenario 1.

According to the prospect theory, and . Parameters and are set based on the relevant literature [21,23,25]. In addition, three different parameter sets are used to test the stability of the model. Please refer to Table 7 for the setting of parameter sets.

Table 7.

Parameter sets for the simulation analysis.

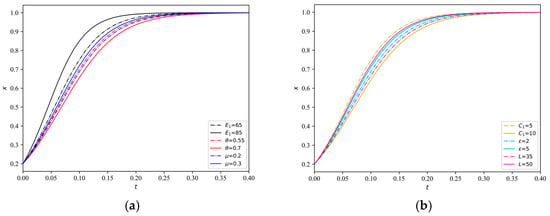

5.1. Simulation Analysis of System Evolution Process Under Different Parameter Sets

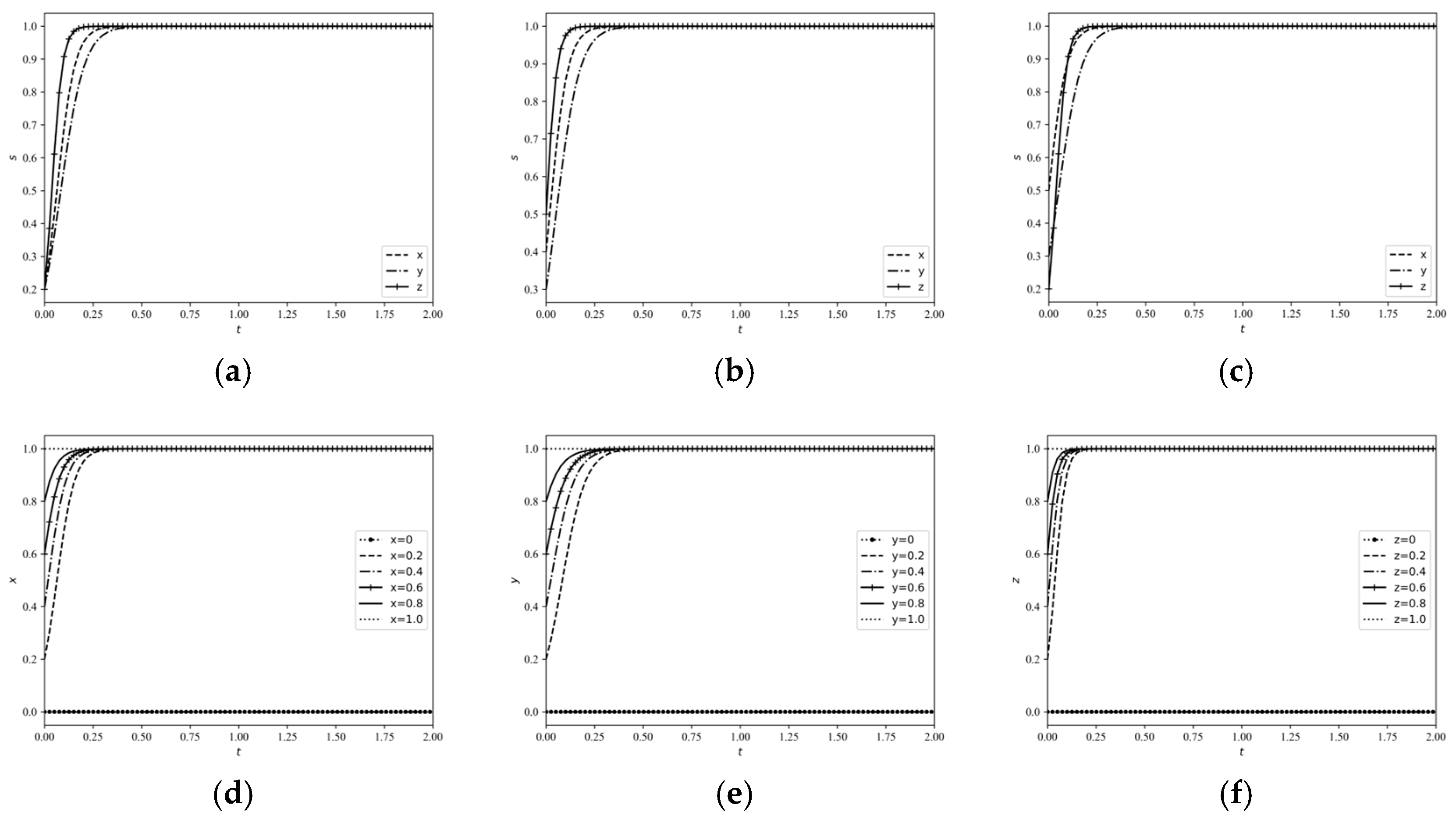

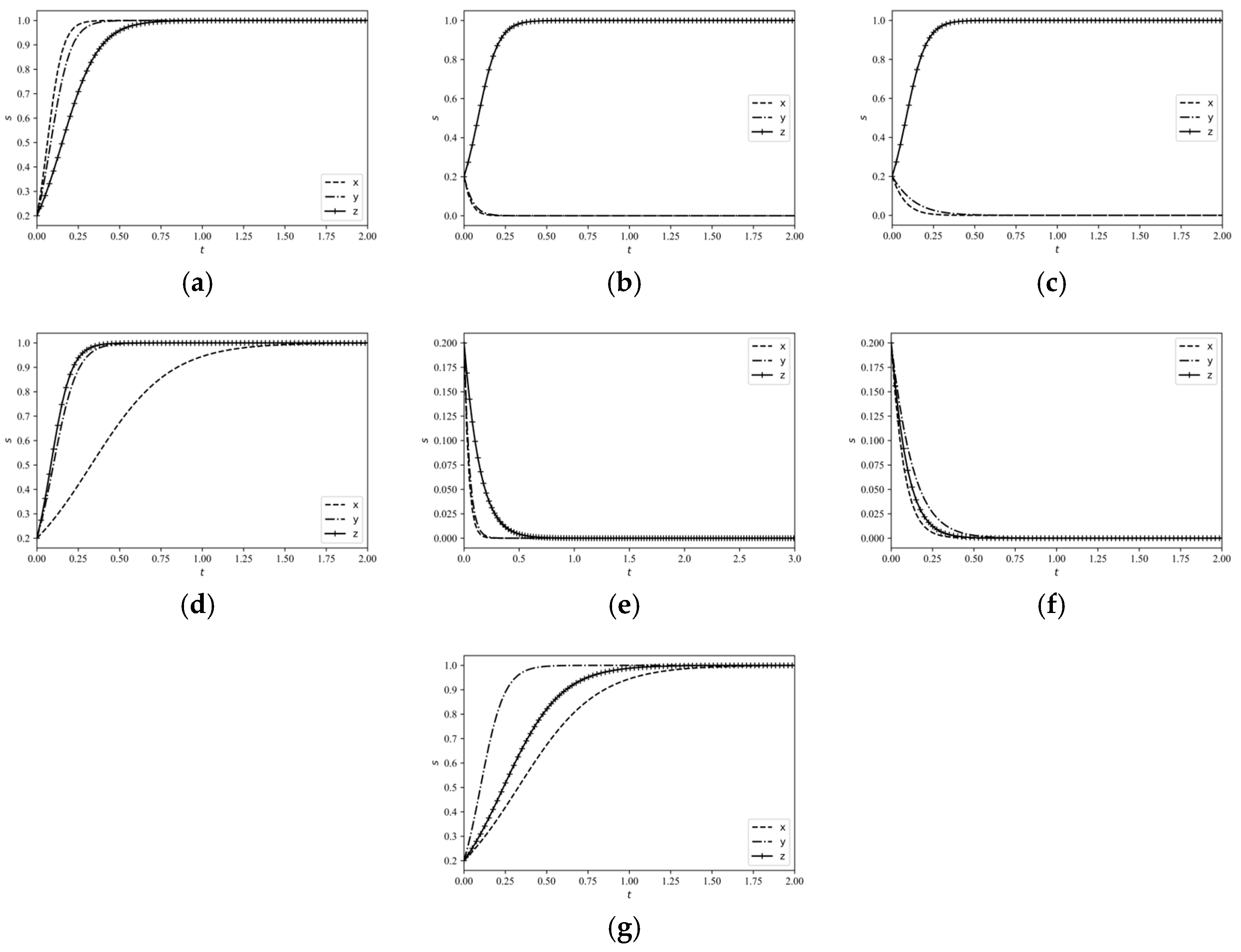

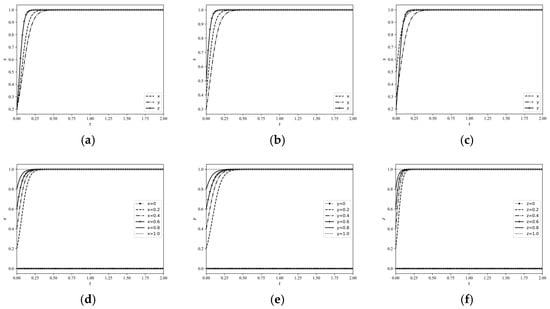

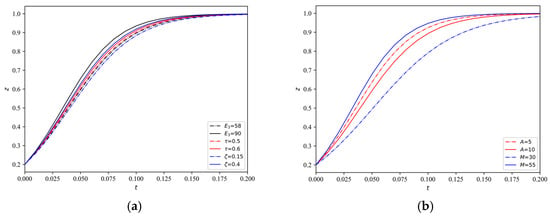

Since the initial probabilities of the three-party game players , , and are randomly distributed in , we use the first parameter set to analyze the path evolution of the three-party game system with different initial probabilities in this paper, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

(a) The influence of the same initial probability on the evolutionary path of each participant under the first parameter set; (b,c) the influence of the different initial probability on the evolutionary path of each participant under the first parameter set; (d) the influence of the different initial probability on the evolutionary path of enterprises under the first parameter set; (e) the influence of the different initial probability on the evolutionary path of graduates under the first parameter set; (f) the influence of the different initial probability on the evolutionary path of universities under the first parameter set.

From Figure 5a–c, it can be observed that when the additional profits for all parties involved exceed the costs, the initial probabilities (, , ) of the three entities, enterprises, graduates, and universities, adopting positive behavioral strategies, regardless of whether they are equal or not (except for the probability ), will gradually increase and ultimately converge to . This aligns with the conclusion of ESS in Scenario 1, which is “recruitment, participation in recruitment, active employment assistance”. As illustrated in Figure 5d–f, as the initial probabilities gradually increase, the convergence rate of the three groups adopting positive behavioral strategies will accelerate, and they will remain in a stable state over the long term. This demonstrates that for enterprises, graduates, and universities, their willingness to actively engage in (or participate in) recruitment activities intensifies as they obtain sufficient profits. Additionally, universities should strive to actively carry out various forms of employment assistance, leveraging methods such as university–enterprise cooperation to enhance graduates’ employability and provide necessary assistance to enterprises during the recruitment process. By doing so, more graduates and enterprises can be encouraged to participate in campus recruitment, which not only reduces the proportions of slow employment among students and recruitment difficulties for enterprises but also enhances the reputation and social recognition of universities. This approach simultaneously achieves the dynamic optimization of talent supply and contributes to social stability and development.

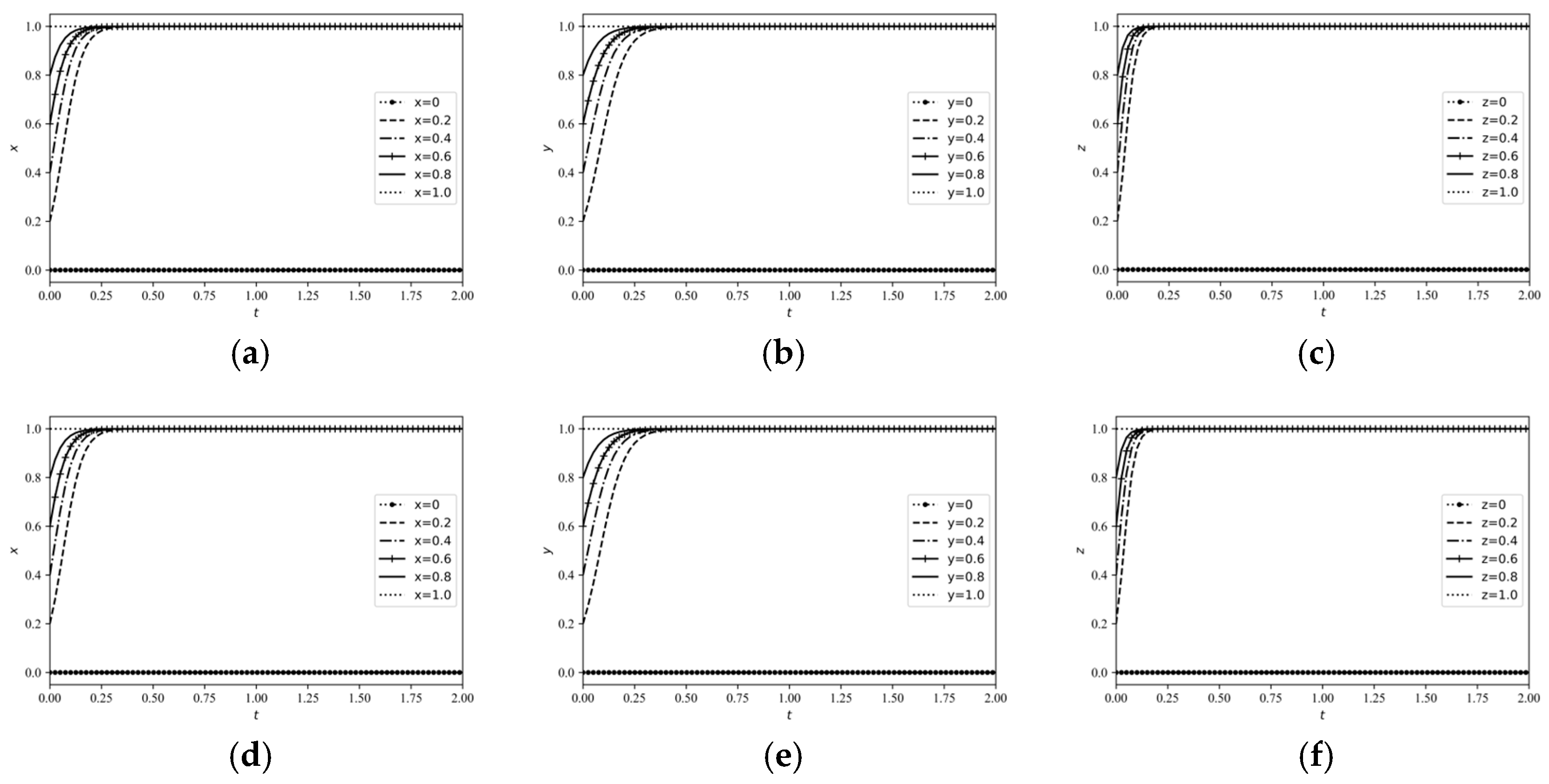

Then, we use the second parameter set and the third parameter set to analyze the path evolution of the three-party game system with different initial probabilities, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

(a–c) The influence of initial probability on evolutionary path under the second parameter set; (d–f) the influence of initial probability on evolutionary path under the third parameter set.

As can be seen from Figure 6a–f, under the second and third parameter sets, with the gradual increase in the initial probability, the convergence rate of enterprises, graduates, and universities adopting positive behavior strategies speeds up and maintains a stable state for a long time. This is consistent with the conclusion of Scenario 1, which also shows that the model in this paper is stable.

It is important to note that, although the evolutionary game model primarily focuses on the pure strategy equilibrium proposition put forward by Friedman [27], excluding the equilibrium of mixed strategies, the transient oscillatory changes observed in the evolutionary path (as shown in Figure 5c) deserve further explanation. These oscillations reflect a period of transitional adaptation rather than a stable mixed equilibrium. In the real-world labor market, such changes may correspond to temporary behavioral ambiguity caused by exogenous labor market or economic shocks. For example, during an economic downturn, enterprises may temporarily suspend recruitment (decreasing the probability of the pure “recruit” strategy) while awaiting market signals. However, the data on employment cycles from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) indicate that once external uncertainties are resolved, organizations ultimately reconverge on deterministic strategies (such as a sustained recruitment freeze or expansion). This phenomenon aligns with our sensitivity analysis (Section 5.4). Crucially, mixed strategies require a continuous balance of benefit probabilities, which, due to institutional inertia (commitment to employment policies by universities) and behavioral anchoring (risk aversion thresholds of graduates), etc., rarely persist in practice. For instance, the German Vocational Education and Training Act reform (2019) initially triggered mixed strategies (enterprises partially hiring while upskilling), but the mandatory 30% practical training quota forced a shift to pure strategies (stable recruitment). Similarly, Tsinghua University’s AI-driven platform reduced mixed strategy duration by 40% through real-time curriculum adjustments, proving that information transparency accelerates pure strategy convergence. Therefore, while mixed strategies may mathematically exist under perfect benefit symmetry, their empirical manifestations remain fleeting and context-specific, rather than evolutionarily stable.

5.2. Simulation and Sensitivity Analysis of Relevant Parameters of Prospect Theory

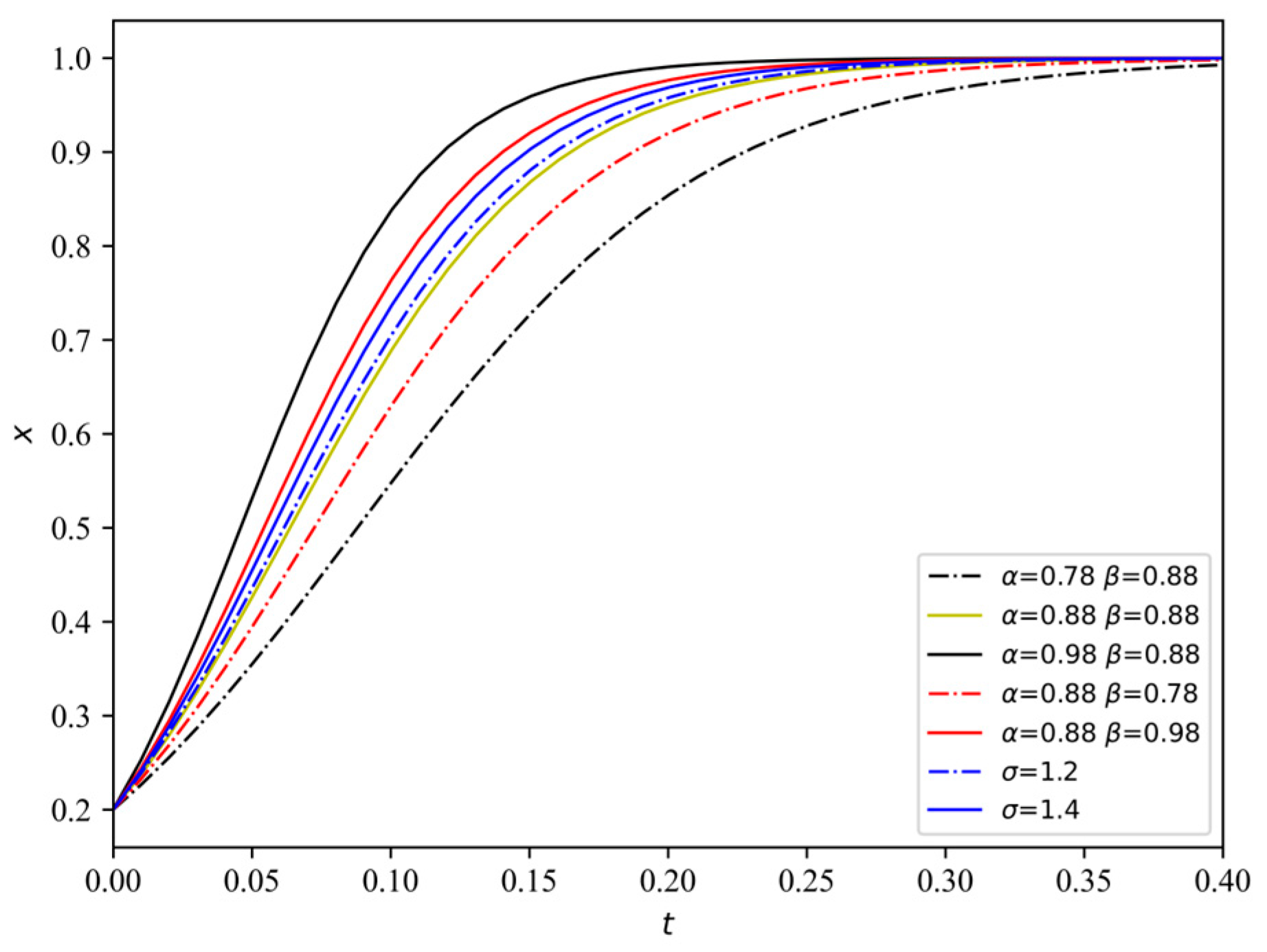

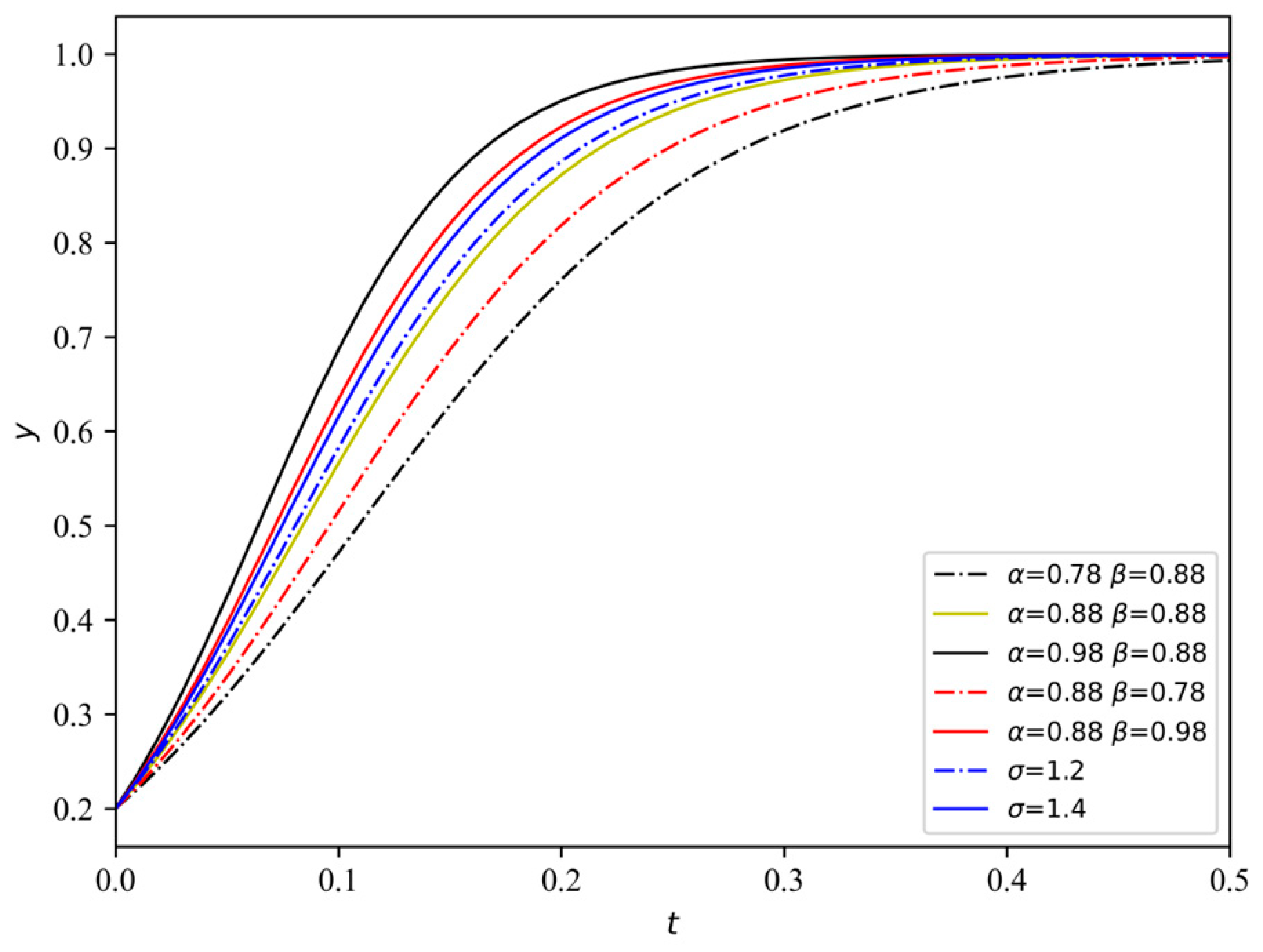

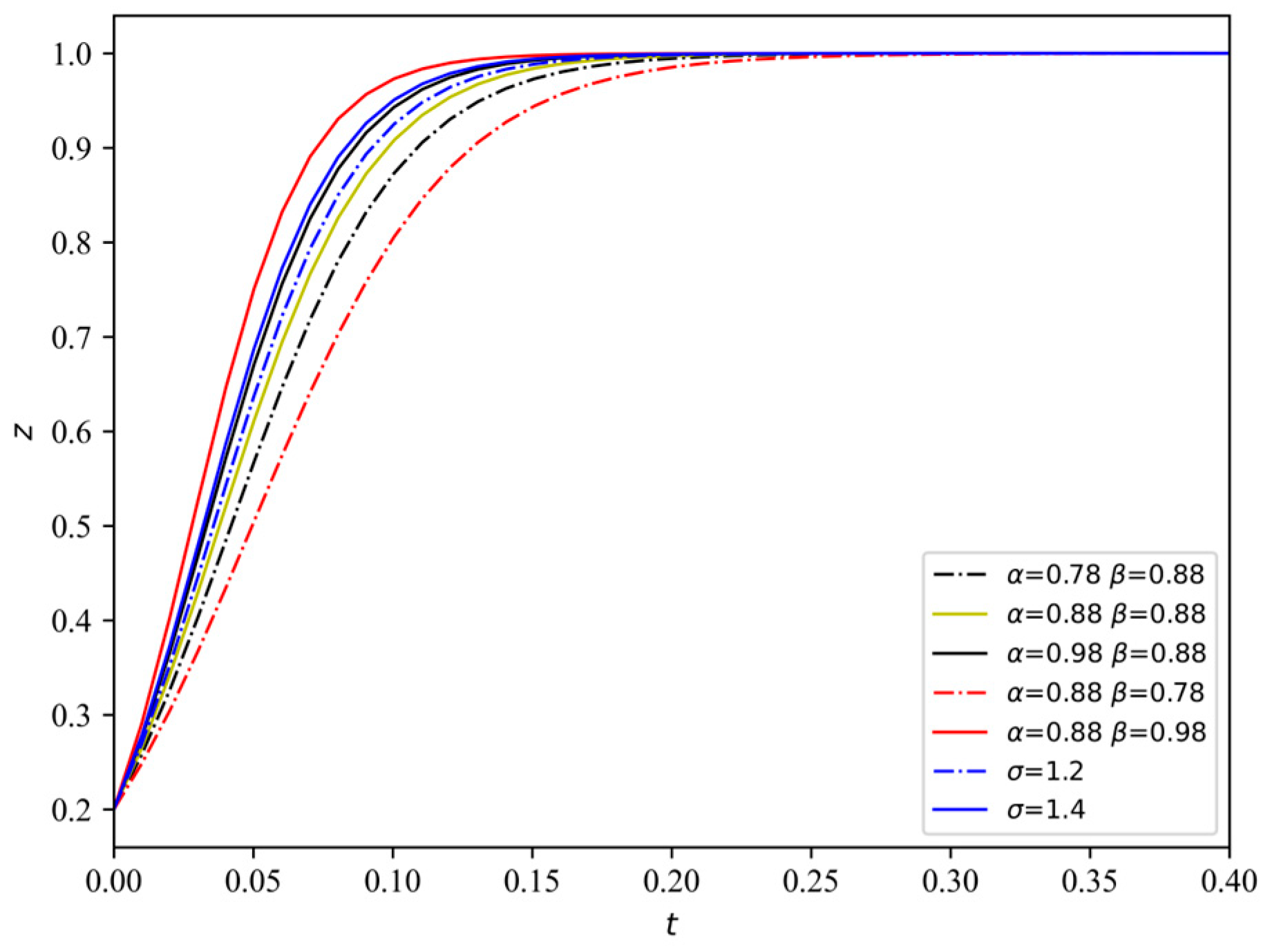

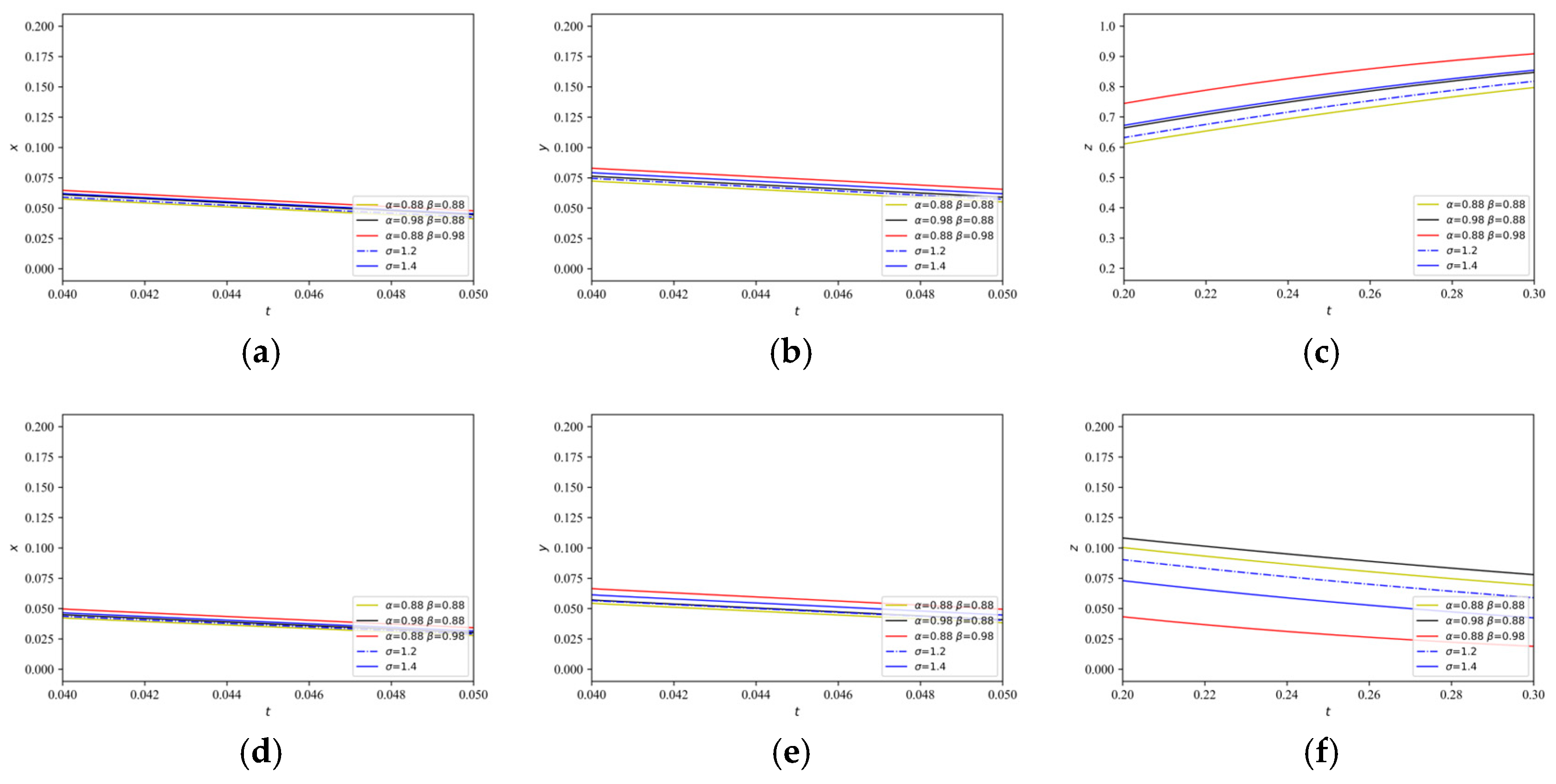

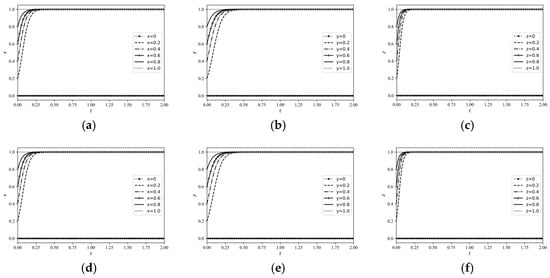

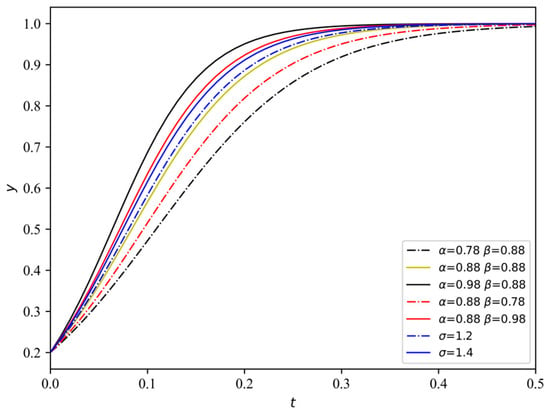

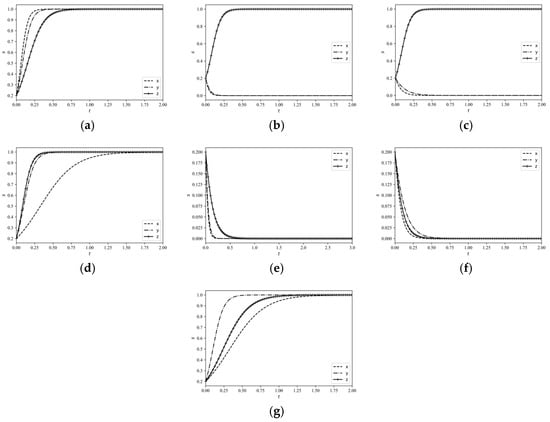

In order to analyze the influence of the relevant parameters of prospect theory on the strategy selection of stakeholders, this paper analyzes the influence of the profit sensitivity coefficient , loss sensitivity coefficient , and loss aversion coefficient on the behavioral strategy of enterprises, graduates, and universities, respectively, in order to reveal the influence mechanism of relevant factors such as psychological perception on the decision-making evolution, as shown in Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9.

Figure 7.

The influence of , , and on enterprises’ strategy.

Figure 8.

The influence of , , and on graduates’ strategy.

Figure 9.

The influence of , , and on universities’ strategy.

As shown in Figure 7, as the profit sensitivity coefficient , loss sensitivity coefficient , or loss aversion coefficient increases (i.e., , , and ), the speed at which enterprises converge towards implementing recruitment strategies accelerates. This indicates that when enterprises are more sensitive to either profits or losses, or have a higher degree of aversion to losses, they tend to actively engage in recruitment activities to mitigate the talent loss risk. The convergence speed of enterprises at is greater than that at , primarily because the scale of profits at this time is larger (profits exceed costs), making enterprises more inclined to adopt proactive strategies when they are more sensitive to profits. Under the current economic downturn, enterprises are becoming increasingly sensitive to profits and losses. Therefore, for enterprise entities, an increase in profit sensitivity accelerates the convergence of recruitment strategies, particularly in knowledge-intensive industries (such as artificial intelligence and semiconductors) where the scarcity of talent amplifies the perceived opportunity cost. However, in cyclical industries (like construction), excessive sensitivity may lead to over-recruitment during boom times and sudden recruitment freezes during downturns, mirroring the “bullwhip effect” in supply chains. Additionally, loss sensitivity dominates in risk mitigation. Firms with higher loss sensitivity exhibit “preemptive recruitment” behaviors, hiring ahead of demand to prevent poaching by competitors, akin to a precautionary inventory strategy prevalent in industries with high employee turnover rates (such as retail). Moreover, a strong aversion to losses compresses the strategic adjustment cycle. For instance, technology giants swiftly escalate countermeasures (such as retention bonuses) in response to talent loss (like the departure of key engineers), reflecting the hyperbolic discounting of short-term retention costs versus long-term innovation risks.

The evolution process of graduates in Figure 8 is similar to that of enterprises. As , , and increase (i.e., , , and ), the speed at which graduates converge towards participating in recruitment strategies accelerates. This indicates that graduates, like enterprises, tend to actively engage in recruitment activities when they are more sensitive to profits or losses, in order to avoid unemployment risk. The convergence speed of graduates at is greater than that at , primarily because when the profits for graduates outweigh the costs, they are more inclined to adopt proactive strategies as graduates become more sensitive to profits. Overall, for the group of graduates in emerging fields such as ESG careers, the increase in profit sensitivity drives a first-mover advantage. However, in saturated markets like civil service examinations, it may lead to a “bandwagon effect”, where overcrowding reduces individual success rates. In these markets, excessive competition diminishes personal prospects. Meanwhile, graduates with high loss sensitivity adopt the “portfolio diversification” strategy, preparing for employment exams, internships, and entrepreneurship simultaneously. This reflects behavioral finance strategies to hedge against unemployment risks, albeit often at the cost of resource dilution. Additionally, heightened loss aversion results in “anchoring bias”, where graduates continue to target historically stable employers (such as state-owned enterprises) despite declining return rates, analogous to the status quo bias in retirement investment decisions. Therefore, in the face of a severe employment situation, graduates should actively adjust their employment mindset, understand and analyze enterprise and job information through various channels, achieve precise job applications, summarize interview and exam experiences, and enhance employment quality while reducing unemployment risk.

As shown in Figure 9, similar to the evolution process of enterprises and graduates, as , , or increase (i.e., , , and ), universities converge towards adopting proactive employment assistance strategies more rapidly to avoid risks. The difference lies in the fact that the convergence speed at is slower than that at , indicating that the risks faced by universities at this time exceed the costs (Scenario 1 ). For university entities, higher profit sensitivity (framed by employment rate incentives) prompts universities to align their curricula with industry trends (for example, by increasing courses in artificial intelligence). However, excessive emphasis may neglect foundational disciplines, analogous to “short-termism” in corporate R&D allocation. High loss sensitivity can trigger institutional overcompensation, such as universities in industrially declining regions excessively promoting vocational training, potentially locking graduates into outdated skill sets. Loss aversion, on the other hand, manifests as reputational conservatism. Top-tier universities maintain aggressive employment support policies to avoid ranking declines, while lower-tier universities exhibit “policy mimicry”, replicating strategies from elite institutions despite mismatched student demographics. Therefore, as a talent cultivation hub, the employment level of universities not only serves as an important benchmark for measuring the quality of higher education but also directly impacts university admissions and social recognition. This demonstrates that universities should further strengthen their employment services, provide targeted support, and guide students in employment and entrepreneurship to improve the employment level of graduates.

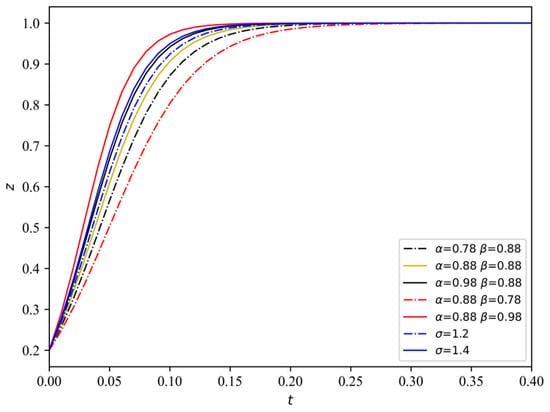

5.3. Simulation Analysis of Other Parameters

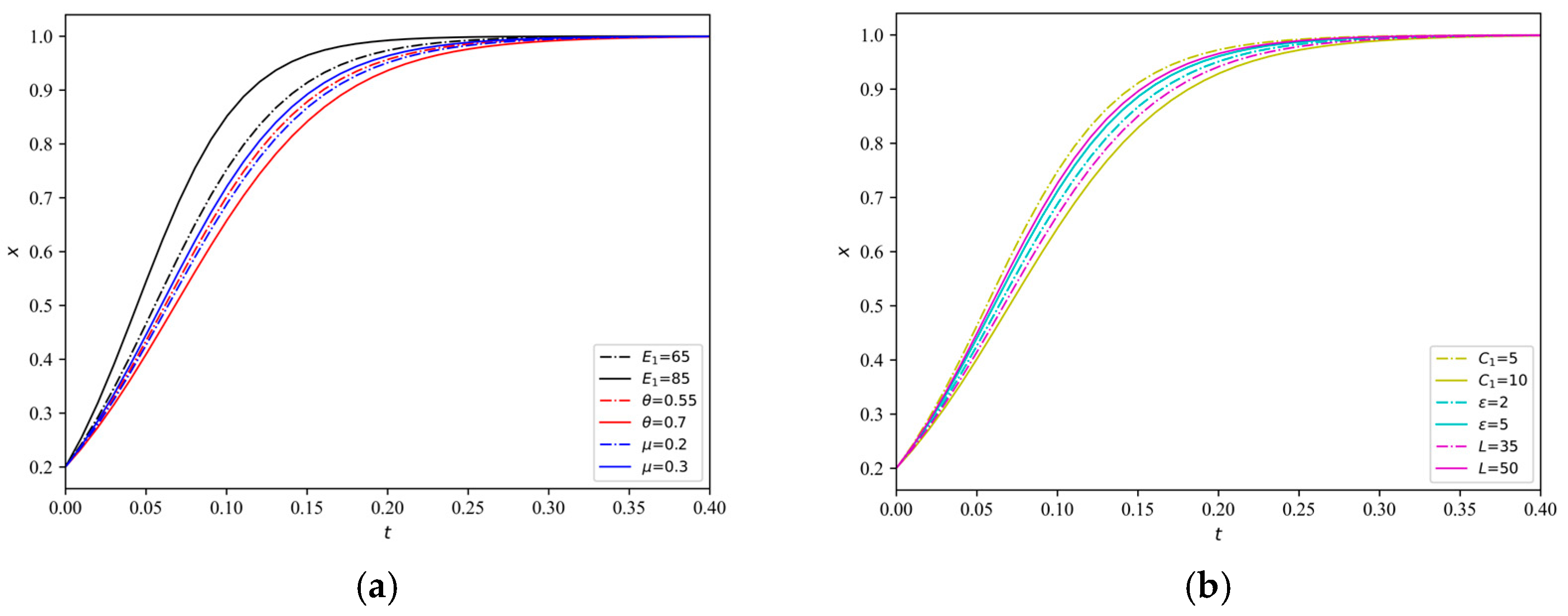

To further explore the conditions of system evolution, this paper analyzes the influence of , , , , , and on the group evolution strategy of enterprises, the influence of , , , , , and on the group evolution strategy of graduates, and the influence of , , , , and on the group evolution strategy of universities.

5.3.1. The Influence of Relevant Parameters on Enterprises’ Evolution Strategy

As shown in Figure 10a, as the additional profit and the change in the matching rate of graduates increase, the speed at which enterprises converge towards implementing recruitment strategies accelerates, while the graduate matching rate exhibits an opposite trend. When universities provide employment assistance, the efficiency of talent selection by enterprises improves, leading to increased additional profits and subsequently enhancing their willingness to recruit graduates. However, when the graduate matching rate of enterprises improves, indicating higher recruitment efficiency and capability, their willingness to conduct recruitment decreases accordingly. From Figure 10b, it can be observed that as the talent loss risk and the change in recruitment cost faced by enterprises increase, the convergence speed of enterprises in implementing recruitment strategies accelerates, whereas the recruitment cost shows an opposite trend. This is primarily because enterprises tend to adopt proactive strategies to avoid risks when facing high risks, while they often scale back their operations to reduce costs when confronted with high costs. Meanwhile, various employment support measures provided by universities can significantly increase enterprises’ willingness and scale of recruitment, thereby boosting recruitment demand and providing more job opportunities for graduates.

Figure 10.

(a) The influence of , , and on enterprises’ strategy; (b) the influence of , , and on enterprises’ strategy.

5.3.2. The Influence of Relevant Parameters on Graduates’ Evolution Strategy

As shown in Figure 11a, as the additional profit and the change in the matching rate of graduates’ ideal positions increase, the speed at which graduates converge towards participating in recruitment strategies accelerates, while the matching rate of graduates finding ideal positions exhibits an opposite trend. When graduates have strong employability, they tend to have higher employment expectations and neglect entry-level positions, resulting in a decreased probability of participating in recruitment. However, when universities provide various employment guidance and support to graduates, their employment success rate improves, leading to increased additional profits and subsequently boosting the proportion and willingness of graduates to actively participate in recruitment.

Figure 11.

(a) The influence of , , and on graduates’ strategy; (b) the influence of , , and on graduates’ strategy.

From Figure 11b, it can be observed that as the unemployment risk and the change in job search cost faced by graduates increase, the convergence speed of graduates in choosing to participate in recruitment strategies accelerates, while the job search cost shows an opposite trend. This indicates that graduates should actively enhance their employability to better seize career opportunities and reduce the risk of unemployment. In this context, universities should adopt various effective measures, including career planning guidance, skills training, and university–enterprise cooperation, to provide necessary support and assistance to graduates, thereby enhancing their market competitiveness. Through proactive employment support measures, universities can not only help students improve their employability but also effectively reduce the unemployment risk they face, thus facilitating graduates’ smooth entry into the workplace and the achievement of their personal career development goals.

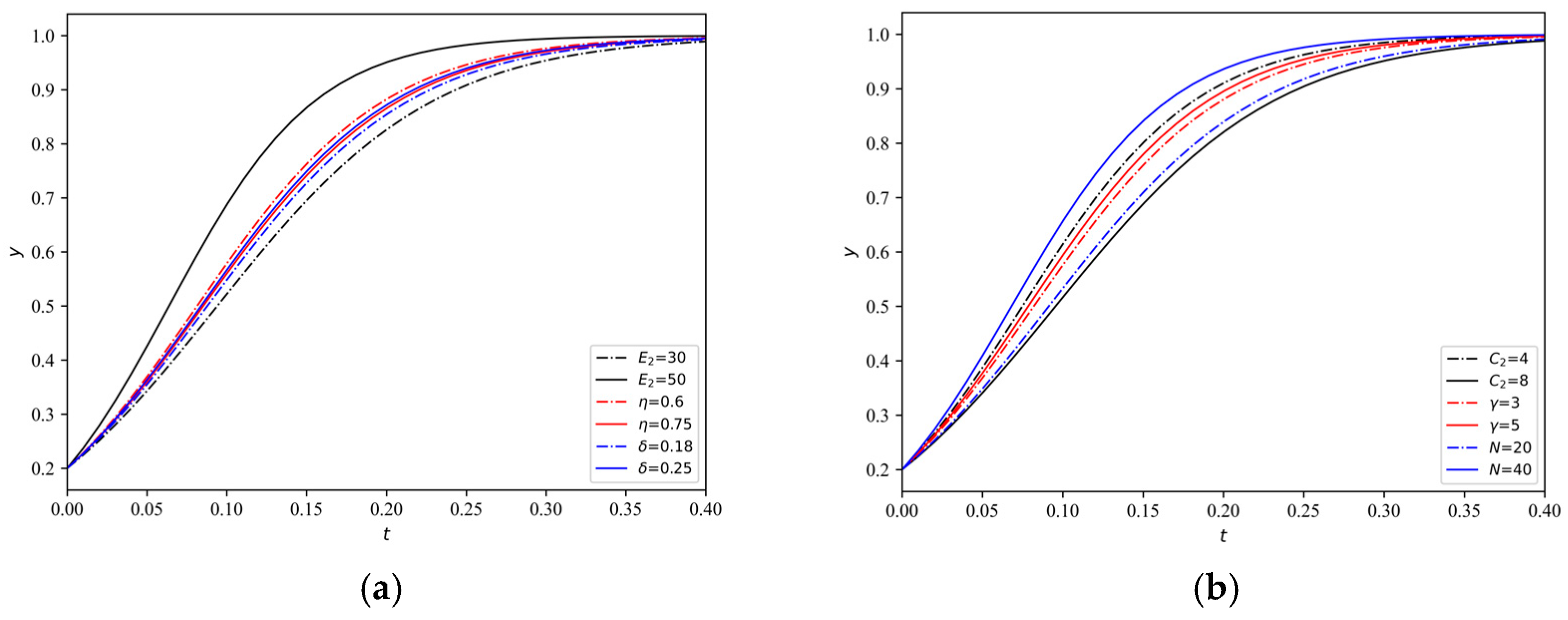

5.3.3. The Influence of Relevant Parameters on Universities’ Evolution Strategy

As shown in Figure 12a, with the increase in additional profits , employment level coefficient , and recruitment level coefficient , the convergence speed of universities in implementing proactive employment assistance strategies significantly accelerates. This phenomenon occurs because, as these influencing factors increase, universities can more clearly identify potential opportunities and challenges in the job market, thereby adjusting their employment support strategies more rapidly to meet the needs of graduates and employers. The increase in additional profits implies that universities’ investments in employment support can yield higher returns, while the elevation in the employment level coefficient and recruitment level coefficient indicates an increasing demand for graduates in the market, prompting universities to respond more swiftly to enhance their social responsibility and competitiveness.

Figure 12.

(a) The influence of , , and on universities’ strategy; (b) the influence of and on universities’ strategy.

From Figure 12b, it can be observed that as the risk of decreased social recognition faced by universities increases, the convergence speed of universities in choosing proactive employment assistance strategies also accelerates, while the additional input cost for employment support shows an opposite trend. This suggests that when universities face higher risks of decreased social recognition, they are more inclined to swiftly adopt proactive employment support measures to maintain their reputation and social responsibility. At the same time, universities will exercise greater caution in controlling the additional input costs for employment assistance to ensure effective resource utilization.

5.4. Simulation Analysis of System Evolution Process Under Other Scenarios

In order to simulate the stability and reliability of the model in other scenarios, this section analyzes the system evolution process under Scenario 2, Scenario 3, and Scenario 4, and the parameter settings are shown in Table 8.

Table 8.

Parameter sets for the simulation analysis under other scenarios.

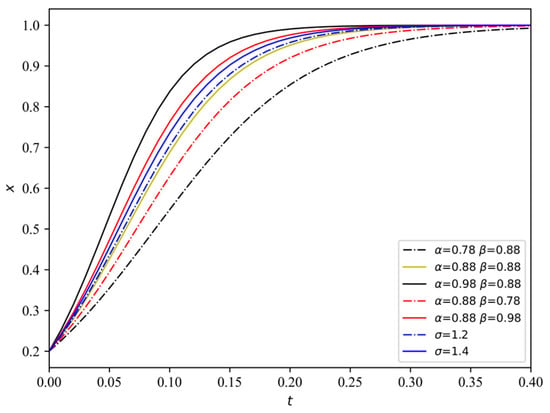

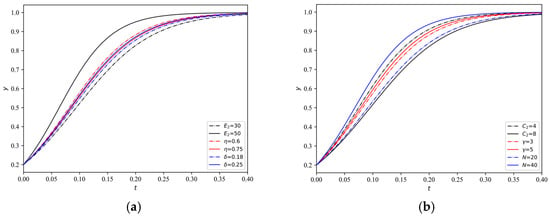

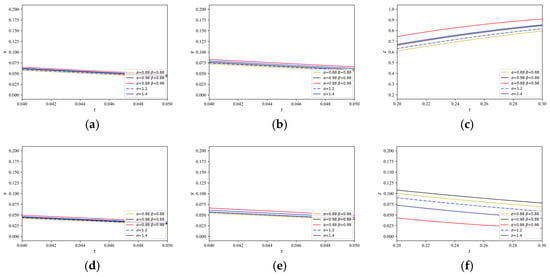

According to the above parameter sets in different scenarios, we obtain the evolutionary path of the three-party game system under Scenarios 2–4, as shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

(a) The evolutionary path under Scenario 2; (b) the evolutionary path under Scenario 3(a); (c,d) the evolutionary path under Scenario 3(b); (e) the evolutionary path under Scenario 4(a); (f,g) the evolutionary path under Scenario 4(b).

From Figure 13a, it is evident that when the additional profits for enterprises, graduates, and universities all exceed their costs, and universities perceive relatively low risks, the three parties quickly converge on active behavioral strategies (i.e., ), aligning with the model conclusion of Scenario 2. This validates the positive incentive effect of “high returns–low risk” during economic prosperity on collaborative behavior. Figure 13b reveals a typical dilemma during economic downturns: although universities are forced to adopt active strategies (i.e., ) due to high risks, enterprises and graduates choose passive strategies due to cost–profit mismatches, forming a fragile equilibrium of “unilateral efforts by universities”, which is consistent with the conclusion of Scenario 3(a). Scenario 3(b) (i.e., Figure 13c,d) further demonstrates the bistability (i.e., and ) where, when universities’ employment policy interventions partially alleviate the cost pressures of enterprises and graduates, the system may transition to the ideal state (i.e., ) but may also stagnate in a low-efficiency equilibrium (i.e., ) due to uncrossed risk thresholds, highlighting the importance of policy precision. In Scenario 4(a) (i.e., Figure 13e), all three parties adopting passive behavioral strategies (i.e., ) reflects the “low returns–low risk” trap—when participants’ returns fail to cover costs and risk deterrence is insufficient, the system falls into collective inertia. Meanwhile, the bistability (i.e., and ) in Figure 13f,g indicates that through institutional design (such as linking university employment rates to financial allocations and imposing recruitment constraints on corporate ESG ratings), the risk–return ratio can be reconfigured, forcing the system to shift from a passive equilibrium to active behavioral strategies, namely , which aligns with the model conclusion of Scenario 4(b). Therefore, the simulation results in Figure 13 show that the equilibrium state of this tripartite employment game system is highly dependent on the dynamic matching of the economic environment and risk–return structure. From a top–down design perspective, the government needs to construct a three-dimensional regulatory framework of “economy–policy–institution”, strengthening risk-sharing agreements between universities and enterprises during economic expansion to consolidate positive equilibria (Scenario 2), repairing the cost–profit structure through targeted subsidies and tax credits during recessions (guiding Scenarios 3(b)/4(b) towards ), and introducing mandatory assessments and reputational penalty mechanisms for passive equilibria (Scenario 4(a)) to ensure sustainable collaboration in the talent supply chain with institutional rigidity.

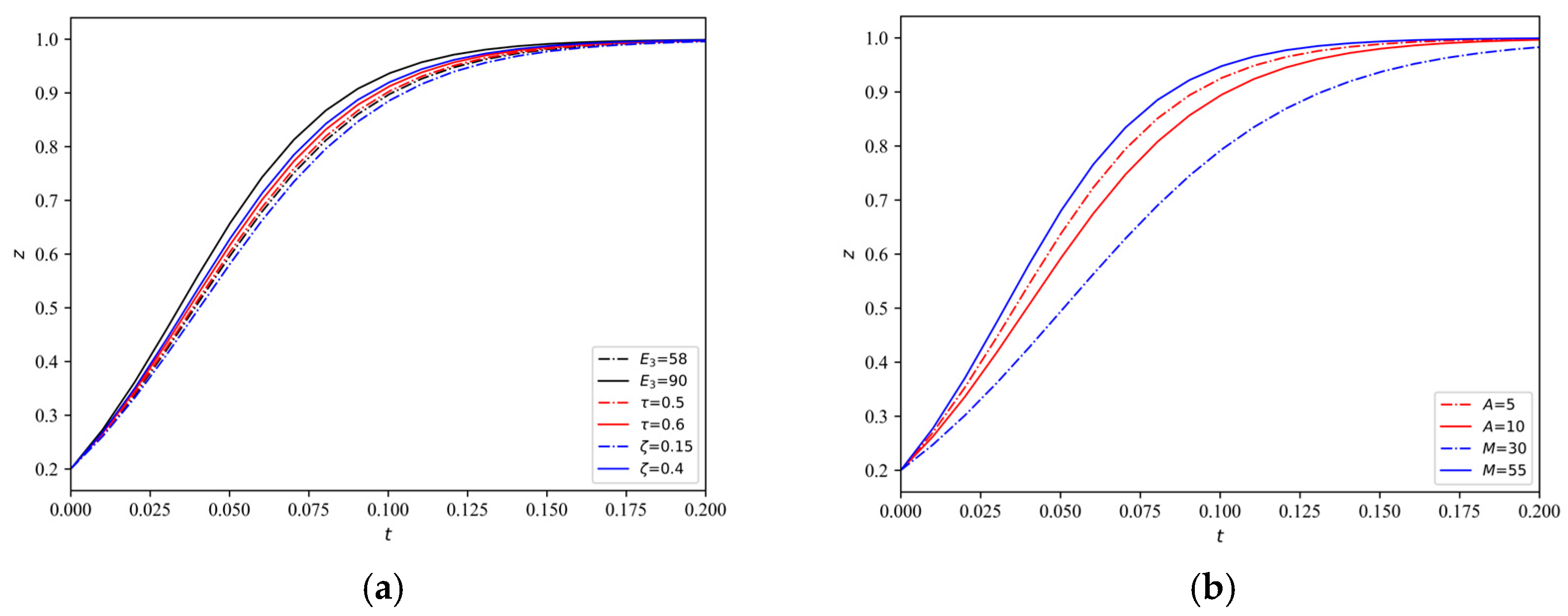

In addition, in order to discuss the influence of relevant parameters of the prospect theory on the evolution path of the game system in other scenarios, sensitivity analysis was conducted for Scenario 3(a) and Scenario 4(a). The parameter values are set in Table 9, and the analysis results are shown in Figure 14.

Table 9.

Parameter sets for the sensitivity analysis under Scenario 3(a) and Scenario 4(a).

Figure 14.

(a) The influence of , , and on enterprises’ strategy under Scenario 3(a); (b) the influence of , , and on graduates’ strategy under Scenario 3(a); (c) the influence of , , and on universities’ strategy under Scenario 3(a); (d) the influence of , , and on enterprises’ strategy under Scenario 4(a); (e) the influence of , , and on graduates’ strategy under Scenario 4(a); (f) the influence of , , and on universities’ strategy under Scenario 4(a).