Executive Cognition, Capability Reconstruction, and Digital Green Innovation Performance in Building Materials Enterprises: A Systems Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Literature Review

2.1.1. Executive Cognition and DGI Performance

2.1.2. Reconceptualizing DGI Performance and Capabilities

2.1.3. Executive Cognition and Capability Reconstruction

2.1.4. Executive Cognition, DGI Performance, and Capability Reconstruction

2.2. Hypotheses

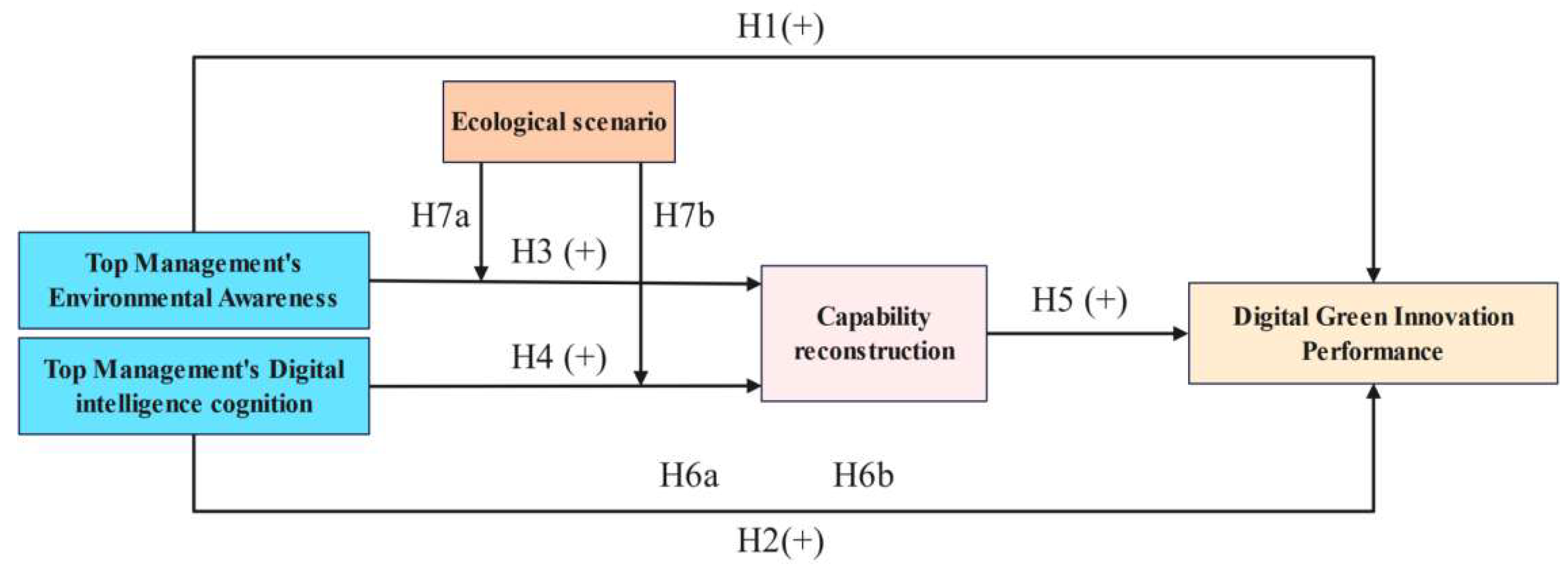

2.2.1. The Impact of Executive Cognition on Digital Green Innovation Performance

- (1)

- The impact of senior executives’ EA on DGI performance

- (2)

- The impact of senior executives’ DIC on DGI performance

2.2.2. The Impact of Executive Cognition on Capability Reconstruction

- (1)

- The impact of executives’ EA on CR

- (2)

- The Impact of senior executives’ DIC on CR

2.2.3. The Impact of DGI Performance on Capability Reconstruction

2.2.4. Connections Between Executive Cognition, DGI Performance, and Capability Reconstruction

- (1)

- The mediating effect of CR

- (2)

- The regulatory effect of ES

2.3. Model Design

3. Methodology

3.1. Methods

3.2. Sample Selection

3.2.1. Questionnaire Data Collection and Screening

3.2.2. Data Screening

3.2.3. Variable Selection Using the fsQCA Method

3.3. Variable Measurement

3.3.1. Measurement of Main Variables

3.3.2. Control Variable Measurement

3.3.3. Variable Calibration

3.4. Common Method Bias

3.5. Reliability and Validity Analysis

3.5.1. Reliability Analysis

3.5.2. Validity Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics Analysis

4.1.1. Basic Characteristics

4.1.2. Statistics Analysis

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

4.2.1. Direct Effect Test

4.2.2. The Mediating Effect of Capability Reconstruction

4.2.3. Regulatory Effect of the Ecological Context

4.3. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.3.1. Types of BMEs

4.3.2. Type of Industry

4.4. Discussion

4.4.1. Necessary Condition Analysis

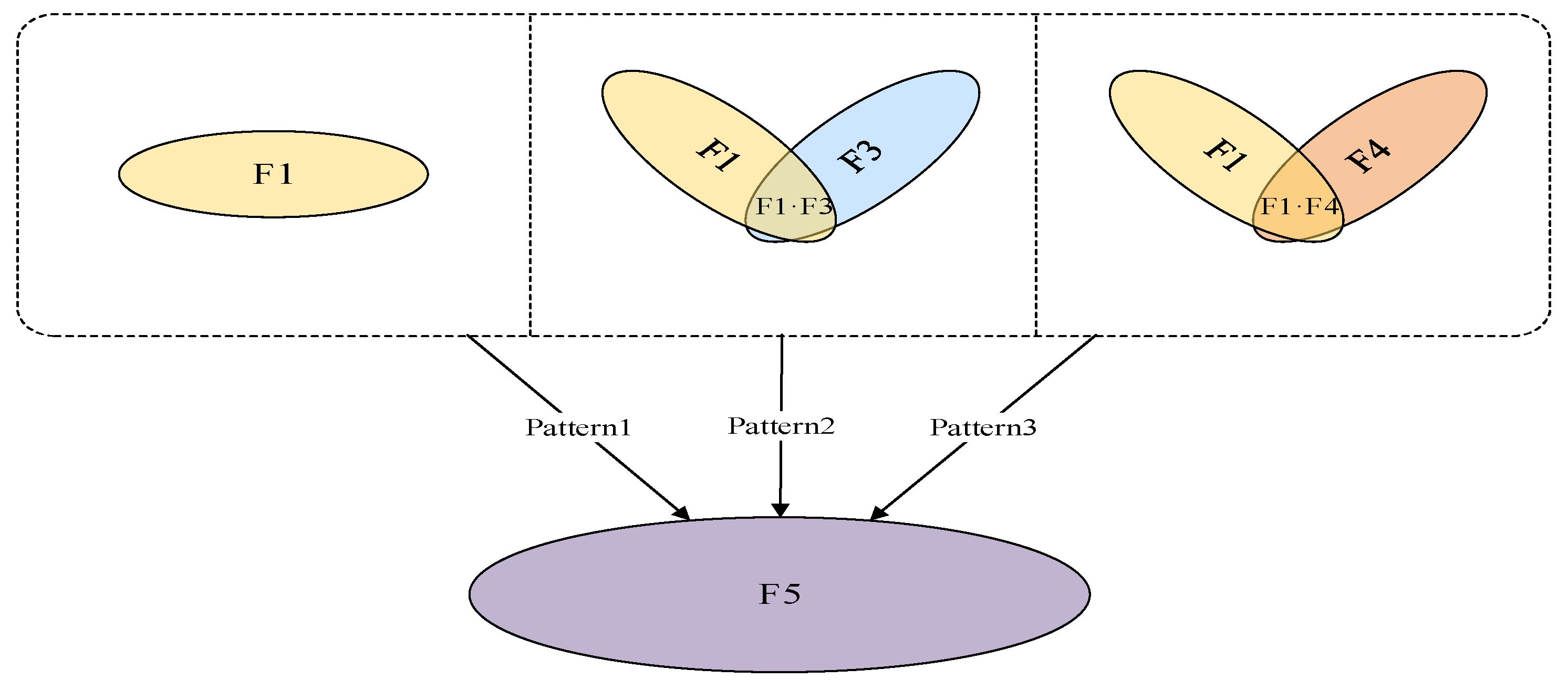

4.4.2. Analysis of the Performance Path of DGI

- (1)

- Environmental-cognitive-driven type.

- (2)

- Cognitive–ability synergy type.

- (3)

- Cognitive–situational symbiosis type.

4.4.3. Robustness Test

5. Conclusions and Future Research Prospects

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Implications

5.2.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMEs | Building materials enterprises |

| EA | Environmental awareness |

| DIC | Digital intelligence cognition |

| CR | Capability reconstruction |

| DGIP | DGI performance |

| ES | Ecological scenario |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Variable | Item | Options |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Information | Years of operation | Less than 3 years 3–5 years 5–10 years More than 10 years |

| Scale of operation | 1. Less than 100 people; 2. 100–300 people; 3. 300–500 people; 4. 500–1000 people; 5. More than 1000 people | |

| Industry category to which it belongs | 1. labor-intensive 2. capital-intensive 3. technology-intensive | |

| Nature | 1. State-owned enterprises 2. Non-state-owned enterprises | |

| Environmental awareness | You can actively engage in environmental governance and planning. You believe that green innovation can enhance the comprehensive competitiveness of enterprises. You think that the current market has a preference for green consumption. Your enterprise actively improves green processes to increase production efficiency. | 1. Very inconsistent 2. Relatively inconsistent 3. Somewhat inconsistent 4. Average 5. Somewhat consistent 6. Relatively consistent 7. Very consistent |

| Digital intelligence cognition | You can proactively acquire knowledge about digital intelligence technology. You believe that enterprises should actively develop digital intelligence technology to enhance their comprehensive competitiveness. You can leverage digital intelligence technology to boost employees’ R&D and innovation capabilities. You can utilize digital intelligence technology to make strategic plans for the enterprise. | |

| Reconstruction of capabilities | Your enterprise can appropriately adjust its existing organizational capabilities and conventional practices. Your enterprise absorbs new knowledge to consolidate and supplement its existing knowledge base. Your enterprise explores and develops brand-new concepts or principles. Your enterprise innovates and adopts different methods, conventions and processes. | |

| Ecological scenario | Your enterprise frequently collaborates with major universities, research institutions, and others on DGI. Your enterprise and its partners mutually disclose relevant information that is helpful for decision-making. Your enterprise and its partners share various types of resources. The innovation ecosystem provides convenience for communication and exchange among each other. | |

| DGI performance | The output value of your company’s new digital green innovative products accounts for a large proportion of the total sales. The customer satisfaction rate of the digital green innovative products developed by your company is relatively high. The digital green innovative activities have increased the company’s sales and profits. Your company has relatively advanced production equipment or technological processes. The market share of the digital green innovative products developed by your company is relatively high. |

Appendix A.2

| Feature | Category | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Within three years | 25.2% |

| Three to five years | 23.6% | |

| 5–10 years | 23.6% | |

| Over 10 years | 27.6% | |

| Scale | Less than 100 people | 30.5% |

| 100–300 people | 31.3% | |

| 300–500 people | 12.2% | |

| 500–1000 people | 12.3% | |

| Over 1000 people | 13.7% | |

| Category | Labor-intensive | 31.9% |

| Capital-intensive | 32.5% | |

| Technology-intensive | 35.6% | |

| Nature | State-owned BMEs | 29.3% |

| Non-state-owned BMEs | 70.7% |

Appendix A.3

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| 1. EA | 1 | ||||||||

| 2. DIC | 0.546 *** | 1 | |||||||

| 3. ES | −0.0539 | 0.004 | 1 | ||||||

| 4. CR | 0.350 *** | 0.361 *** | −0.106 ** | 1 | |||||

| 5. DGIP | 0.338 *** | 0.507 *** | 0.057 | 0.315 *** | 1 | ||||

| 6. Age | 0.082 | 0.056 | −0.065 | 0.031 | −0.002 | 1 | |||

| 7. Scale | 0.022 | −0.018 | 0.026 * | 0.048 | −0.003 | 0.263 *** | 1 | ||

| 8. Category | 0.081 | 0.058 | 0.086 | 0.052 | 0.052 | 0.013 | 0.076 | 1 | |

| 9. Nature | 0.056 | −0.002 | 0.021 | −0.053 | −0.101 ** | −0.043 | −0.193 *** | 0.008 | 1 |

| Mean | 4.258 | 4.305 | 4.230 | 4.066 | 4.175 | 2.532 | 2.486 | 2.038 | 1.713 |

| Std. dev. | 1.276 | 1.229 | 1.411 | 1.417 | 1.065 | 1.146 | 1.392 | 0.823 | 0.456 |

References

- Jha, S.K.; Farooq, A.S.; Ghosh, A. Thin-Film Solar Cells for Building-Integrated Photovoltaic (BIPV) Systems. Architecture 2025, 5, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaji, C.R.; de Azevedo, A.R.G.; Madurwar, M. Sustainable Perspective of Ancillary Construction Materials in Infrastructure Industry: An Overview. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 365, 132864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orenga Panizza, R.; Jalaei, F.; Nik-Bakht, M. Towards Circular Construction: Material and Component Stock Assessment in Montréal’s Residential Buildings. Designs 2025, 9, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FPalma, G.; Scotti, F. Synergies in Sustainability: Assessing the Innovation Effects of Digital and Green Investments in EU Cohesion Policy. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Lau, R.Y.K.; Xie, H.; Liu, H.; Guo, X. Social Executives’ Emotions and Firm Value: An Empirical Study Enhanced by Cognitive Analytics. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 175, 114575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, U.; Zhang, H.; Thanh, H.V.; Anees, A.; Ali, M.; Duan, Z.; Zhang, X. A Robust Strategy of Geophysical Logging for Predicting Payable Lithofacies to Forecast Sweet Spots Using Digital Intelligence Paradigms in a Heterogeneous Gas Field. Nat. Resour. Res. 2024, 33, 1741–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkcan, H. How to Improve Financial Performance Through Sustainable Manufacturing Practices? The Roles of Green Product Innovation and Digital Transformation. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2025, 36, 577–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browder, R.E.; Dwyer, S.M.; Koch, H. Upgrading Adaptation: How Digital Transformation Promotes Organizational Resilience. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2024, 18, 128–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandia, J.A.G.; Gavrila, S.G.; de Lucas Ancillo, A.; del Val Núñez, M.T. Towards Sustainable Business in the Automation Era: Exploring Its Transformative Impact from Top Management and Employee Perspective. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2025, 210, 123908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terchila, S. The Future of Entrepreneurship: Strategic Approaches for Business Adaptation in a Changing Global Environment. From Risks to Opportunities. Stud. Bus. Econ. 2025, 20, 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fannon, R.S.; Hernandez, M.E.J.; Campean, F. Mastering Continuous Improvement (CI): The Roles and Competences of Mid-Level Management and Their Impact on the Organisation’s CI Capability. TQM J. 2021, 34, 102–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Ning, Z.; Chen, L.; Zhang, W. The Impact of Interactive Control in Budget Management on Innovation Performance of Enterprises: From the Perspective of Manager Role Stress. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Wang, C.; Ren, H.; Zhang, W. How Does Executive Green Cognition Affect Enterprise Green Technology Innovation? The Mediating Effect of ESG Performance. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ru, Q. The Impact of Executive Resource Cognition Diversity on Enterprise Innovation Output. Master’s Thesis, Anhui University, Hefei, China, 2023; pp. 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ying, Q.; Chen, Y. The Impact of Executive Cognition on Product Innovation in the New Digital Context. Sci. Res. Manag. 2023, 44, 167–178. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, C.; Lv, W.; Wang, J. The Impact of Digital Technology Innovation Network Embedding on Firms Innovation Performance: The Role of Knowledge Acquisition and Digital Transformation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Zhong, Q.; Lee, C.C. Digitalization, Competition Strategy and Corporate Innovation: Evidence from Chinese Manufacturing Listed Companies. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2022, 82, 102166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, N.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Yu, L. Towards Enterprise Sustainable Innovation Process: Through Boundary-Spanning Search and Capability Reconfiguration. Processes 2021, 9, 2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Zhang, X.; Liu, H. Digital Technology Adoption, Digital Dynamic Capability, and Digital Transformation Performance of the Textile Industry: Moderating Role of Digital Innovation Orientation. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2021, 43, 2038–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Huang, J. The Realization and Transformation Law of the Boundary-Spanning Technological Innovation of Manufacturing Enterprises Based on the Framework of “Internal Reconfiguration—Networking Capability—BSTI”. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2024, 35, 1581–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Jamaluddin, Z. Research on the Impact of Human Resource Management on Improving Enterprise Performance. Forum Res. Innov. Manag. 2024, 2, 18–29. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, R.; Kiran, K.B. Unveiling the Dynamic Capabilities’ Influence on Sustainable Performance in MSMEs: A Systematic Literature Review Utilizing ADO-TCM Analysis. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2025, 17, 561–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Jing, Y.; Song, S.; Liu, W. Prompt Literacy for AIGC Empowerment: Reconstructing Human-AI Interaction Capabilities in the Generative AI Era. Inf. Doc. Serv. 2025, 46, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Zhu, X.; Yu, C.; Zhao, G. Executive External Change Cognition, Capability Reconfiguration and Enterprise Disruptive Innovation. Sci. Sci. Manag. S&T 2023, 44, 164–182. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Li, X. Resource Sensing Behavior, Capability Reconfiguration and Enterprise Innovation Performance: The Moderating Role of Network Routines. J. Cent. South Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2020, 26, 128–136. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, X.; Li, H.; Ma, X. The Impact of Ambidextrous Alliances on Enterprise Capability Reconfiguration under the Moderating Role of Knowledge Aggregation. Manag. J. 2021, 18, 99–109. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Qiu, G. From Product-Dominant Logic to Service-Dominant Logic: Digital Transformation of Enterprises from the Perspective of Capability Reconfiguration. R&D Manag. 2022, 34, 39–53. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, X.; Liu, D. Market Cognition Evolution Mechanism of Latecomer Firms Based on the Dynamic Process of Technological Catch-Up. Manag. World 2021, 37, 180–198. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, M.; Cao, H.; Wang, X. Executive Environmental Cognition, Dynamic Capability and Enterprise Green Innovation Performance: The Moderating Effect of Environmental Uncertainty. Sci. Technol. Manag. Res. 2022, 42, 209–216. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, R.; Wang, L. The Impact of Knowledge Integration Capability on Breakthrough Innovation Based on Exploratory Innovation: The Moderating Effects of Absorptive Capacity and Innovation Openness. Sci. Technol. Manag. Res. 2023, 43, 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Xu, Q. Research on the Relationship Between Managerial Cognitive Characteristics and Enterprise Innovation Capability. Sci. Res. Manag. 2018, 39, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, C.; Wang, Q.; Liu, L. Executive Team Cognition and Novel Business Model Innovation in Startup Enterprises: A Moderated Mediation Effect. R&D Manag. 2021, 33, 97–110. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, P.; Wang, C.; Dai, B. Executive Team Cognitive Ability, External Knowledge Search and Efficiency-Oriented Business Model Innovation: The Moderating Role of Big Data Management Skills. Sci. Technol. Manag. Res. 2022, 42, 129–138. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Wu, Y.; Lan, M.; Ning, X. Factors Influencing Innovation Performance in the Electronics Industry Based on Upper Echelons Theory: A Perspective of Executive Cognition. Ind. Technol. Econ. 2018, 37, 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Petti, C.; Nguyen Dang Tuan, M.; Nham Phong, T.; Pham Thi, M.; Ta Huong, T.; Perumal, V.V. Technological Catch-Up and Innovative Entrepreneurship in Vietnamese Firms. Adm. Sci. 2021, 11, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hällerstrand, L.; Reim, W.; Malmström, M. Dynamic capabilities in environmental entrepreneurship: A framework for commercializing green innovations. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 402, 136692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; An, B.; Liu, L.; Li, B. The Evolution of China’s Management Academic Ecology: A Longitudinal Study from the Perspective of Process Theory. J. Renmin Univ. China 2023, 37, 58–73. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Ning, L.; Gao, Q. How Does Multi-Agent Collaboration Achieve High Digital Innovation Performance? A Configuration Study from the Perspective of the Digital Innovation Ecosystem. J. Northeast. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2024, 26, 52–64. [Google Scholar]

- Sjöstrand, S. Social and Environmental Protection: The Effects of Social Insurance Generosity on the Acceptance of Material Sacrifices for the Sake of Environmental Protection. J. Soc. Policy 2025, 54, 249–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, N.K.; Mishra, N.; Sharma, P.P. Unraveling the Relationship between Corporate Governance and Green Innovation: A Systematic Literature Review. Manag. Res. Rev. 2025, 48, 825–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indrawati, H.; Caska, C.; Hermita, N.; Sumarno, S.; Syahza, A. Green Innovation Adoption of SMEs in Indonesia: What Factors Determine It? Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2025, 17, 19–37. [Google Scholar]

- Mansour, M.; Shubita, M.F.; Lutfi, A.; Saleh, M.W.; Saad, M. Female CEOs and Green Innovation: Evidence from Asian Firms. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhal, F.; Hamrouni, A.; Jilani, I.; Mahjoub, I.; Benkraiem, R. The Power of Inclusion: Does Leadership Gender Diversity Promote Corporate and Green Innovation? Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2024, 67, 102128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehzad, M.U.; Zhang, J.; Naveed, K.; Zia, U.; Sherani, M. Sustainable Transformation: An Interaction of Green Entrepreneurship, Green Innovation, and Green Absorptive Capacity to Redefine Green Competitive Advantage. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2024, 33, 7041–7059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Tang, L.; Ekow, V.A.; Hui, H. Impacts of Digital Government on Regional Eco-Innovation: Moderating Role of Dual Environmental Regulations. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 196, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.C.; Huang, S.Y. The Effect of Chinese-Specific Environmentally Responsible Leadership on the Adoption of Green Innovation Strategy. Energy Environ. 2024, 35, 4114–4132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iriantini, D.B.; Pratono, R.; Suryani, W. Strategy to Build Marketing Performance in the Competitive Advantage of MSMEs in Surabaya. Asia Pac. J. Bus. Econ. Technol. 2024, 4, 38–47. [Google Scholar]

- Anomah, S.; Ayeboafo, B.; Aduamoah, M.; Agyabeng, O. Blockchain Technology Integration in Tax Policy: Navigating Challenges and Unlocking Opportunities for Improving the Taxation of Ghana’s Digital Economy. Sci. Afr. 2024, 24, e02210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, S.; Ding, J.; Shah, D.; Xaba, S.; Shoukat, K. Examining the Impacts of Artificial Intelligence Technology and Computing on Digital Art: A Case Study of Edmond de Belamy and Its Aesthetic Values and Techniques. AI Soc. 2025, 40, 2417–2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.; Kumar, A.; Upadhyay, A. How Do Green Knowledge Management and Green Technology Innovation Impact Corporate Environmental Performance? Understanding the Role of Green Knowledge Acquisition. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 551–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, F.; Velez, M.J. Between Regulation and Global Influence: Can the EU Compete in the Digital Economy? Reg. Sci. Environ. Econ. 2025, 2, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, H.G.; Devinney, J.E. Resource Reconfiguration by Surviving SMEs in a Disrupted Industry. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2024, 62, 140–174. [Google Scholar]

- Selcuk, Y. Digital Intelligence as a Partner of Emotional Intelligence in Business Administration. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2023, 28, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, K.M.; Elshamly, A.; Mahgoub, I.G. Do Regulatory Pressures and Stakeholder Expectations Drive CSR Adherence in the Chemical Industry? Sustainability 2025, 17, 2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, C.; Lou, F. Research on Multi-Stage Strategy of Low Carbon Building Material Production by SMEs: A Three-Party Evolutionary Game Analysis. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 10, 1086642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsen, S.E.; Hamdan, A.; Shoaib, H.M. Digital Transformation and Integration of Artificial Intelligence in Financial Institutions. J. Financ. Rep. Account. 2025, 23, 680–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Chau, K.; Chien, F.; Shen, H. The Impact of Startups’ Dual Learning on Their Green Innovation Capability: The Effects of Business Executives’ Environmental Awareness and Environmental Regulations. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, J.M.M.; Danvila-del-Valle, I.; Méndez-Suárez, M. The Impact of Digital Transformation on Talent Management. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 188, 122291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, M.R.; Gbadegesin, R.G.; Ke, Y. Multinational Enterprise Organizational Structures and Subsidiary Role and Capability Development: The Moderating Role of Establishment Mode. Group Organ. Manag. 2023, 48, 908–952. [Google Scholar]

- Kozachenko, E.; Shirokova, G.; Bodolica, V. Antecedents of Effectuation and Causation in SMEs from Emerging Markets: The Role of CEO Temporal Focus. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2025, 33, 1742–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Chai, J.; Lu, S.; Lin, Z. Evaluating Green Technology Innovation Capability in Intelligent Manufacturing Enterprises: A Z-Number-Based Model. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2024, 71, 5391–5409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Huang, R.; Yang, Z.; Dube, L. CSR Types and the Moderating Role of Corporate Competence. Eur. J. Mark. 2018, 52, 1358–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, N.; Li, M. Research on Collaborative Innovation Behavior of Enterprise Innovation Ecosystem under Evolutionary Game. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 206, 123508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Gao, C.; Zhang, S. The Niche Evolution of Cross-Boundary Innovation for Chinese SMEs in the Context of Digital Transformation—Case Study Based on Dynamic Capability. Technol. Soc. 2022, 68, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Slimane, S.; Coeurderoy, R.; Mhenni, H. Digital Transformation of Small and Medium Enterprises: A Systematic Literature Review and an Integrative Framework. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 2022, 52, 96–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeandri, R.; Albert, C.; Caitlin, F. Innovation Performance: The Effect of Knowledge-Based Dynamic Capabilities in Cross-Country Innovation Ecosystems. Int. Bus. Rev. 2023, 32, 58–71. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Hu, B.; Xiang, Y. Business Ecosystem Governance, Top Management Team Social Capital and Enterprise Business Model Innovation. Manag. Rev. 2023, 35, 163–174. [Google Scholar]

- Du, J.; Gong, X. Energy Efficiency “Leader” System and Enterprise Green Innovation: The Moderating Role of Government Ecological Environment Attention and Executive Environmental Experience. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 2024, 41, 141–150. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J. Exploration and Practice of Rural Ecological Civilization Construction Path under Rural Revitalization. Heilongjiang Grain 2024, 15, 123–125. [Google Scholar]

- Fiss, C.P. Building Better Causal Theories: A Fuzzy Set Approach to Typologies in Organization Research. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 393–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Jia, L. Research on the Driving Mechanism of Chinese Enterprises’ Cross-Border M&A: Based on Qualitative Comparative Analysis of Crisp Sets. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2016, 19, 113–121. [Google Scholar]

- Greckhamer, T.; Furnari, S.; Fiss, C.P.; Aguilera, R.V. Studying Configurations with Qualitative Comparative Analysis: Best Practices in Strategy and Organization Research. Strateg. Organ. 2018, 16, 482–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verweij, S.; Noy, C. Set-Theoretic Methods for the Social Sciences: A Guide to Qualitative Comparative Analysis. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2013, 16, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordanini, A.; Parasuraman, A.; Rubera, G. When the Recipe Is More Important Than the Ingredients: A Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) of Service Innovation Configurations. J. Serv. Res. 2014, 17, 134–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, Z.; Zhao, L.; Elahi, E.; Chang, X. The impact of green management on green innovation in sustainable technology: Moderating roles of executive environmental awareness, regulations, and ownership. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 9, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Fei, G.Z. Network Embeddedness, Digital Transformation, and Enterprise Performance—The Moderating Effect of Top Managerial Cognition. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1098974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strilets, V.Y.; Matrynko, V.; Sokol, A. Intermediary Mechanisms for Reconfiguring the Capabilities of Digital Platforms to Create Innovative Business Models for SMEs. Mark. Infrastruct. 2023, 10, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, A.; Shukla, D.M.; Sharma, S.; Dwivedi, G. Fostering Environmentally Sustainable Business: Analysis of Factors from Entrepreneurial Ecosystem Perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 476, 143667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Zhao, L.; Mehrotra, A.; Salam, M.A.; Yaqub, M.Z. Digital Transformation and Corporate Green Innovation: An Affordance Theory Perspective. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2025, 34, 433–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | Name | Variable Operational Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Condition variable | EA | EA is understood here to encompass the active implementation of environmental governance and planning, the recognition that green innovation enhances the comprehensive competitiveness of BMEs, the understanding that the current market has a green consumption preference, and the active improvement of green processes to increase production efficiency. |

| DIC | DIC includes proactively learning about DIC technologies, actively participating in their development, utilizing these technologies to enhance employees’ research and innovation capabilities, and applying them to formulate strategic measures for BMEs. | |

| CR | CR includes appropriately adjusting existing organizational capabilities and conventional practices, absorbing new knowledge to consolidate and supplement existing knowledge, exploring and developing new concepts or principles, innovating, and adopting different methods, routines, and processes. | |

| ES | The ES encompasses DGI cooperation with universities, research institutes, scientific research institutions, etc., the mutual disclosure of relevant information that supports decision making among partners, the sharing of various types of resources, and communication and exchange. | |

| Outcome variable | DGIP | DGIP indicators include DGI product output value in total sales, customer satisfaction, sales and profits, and market share. |

| Condition | Calibration | Descriptive Statistical Analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subordinate to (95%) | Intersection (50%) | Independent of (5%) | Max | Min | Mean | Std. Dev. | |

| EA | 6.0000 | 4.2500 | 2.2500 | 7.00 | 1.50 | 4.135 | 1.164 |

| DIC | 6.4375 | 4.1250 | 2.5000 | 7.00 | 1.75 | 4.221 | 1.152 |

| CR | 6.4375 | 4.2500 | 2.5000 | 7.00 | 1.50 | 4.217 | 1.162 |

| ES | 6.2500 | 4.2500 | 2.2500 | 7.00 | 1.50 | 4.191 | 1.155 |

| DGIP | 6.2000 | 4.2000 | 3.050 | 7.00 | 2.6 | 4.423 | 0.914 |

| Variable | Question Item | Load Value | Cronbach’s Alpha | α | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EA | X1 | 0.751 | 0.815 | 0.825 | 0.847 |

| X2 | 0.783 | 0.816 | |||

| X3 | 0.735 | 0.820 | |||

| X4 | 0.768 | 0.823 | |||

| DIC | X5 | 0.729 | 0.818 | 0.788 | 0.801 |

| X6 | 0.664 | 0.821 | |||

| X7 | 0.762 | 0.819 | |||

| X8 | 0.650 | 0.823 | |||

| ES | T1 | 0.846 | 0.840 | 0.882 | 0.914 |

| T2 | 0.862 | 0.841 | |||

| T3 | 0.841 | 0.841 | |||

| T4 | 0.852 | 0.842 | |||

| CR | Z1 | 0.742 | 0.833 | 0.789 | 0.842 |

| Z2 | 0.706 | 0.829 | |||

| Z3 | 0.818 | 0.831 | |||

| Z4 | 0.748 | 0.828 | |||

| DGIP | Y1 | 0.768 | 0.829 | 0.799 | 0.833 |

| Y2 | 0.748 | 0.830 | |||

| Y3 | 0.692 | 0.831 | |||

| Y4 | 0.668 | 0.832 | |||

| Y5 | 0.641 | 0.833 |

| Model | χ2/df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-Factor | 1.862 | 0.958 | 0.958 | 0.043 | 0.100 |

| 4-Factor | 3.114 | 0.902 | 0.891 | 0.067 | 0.135 |

| 3-Factor | 8.408 | 0.655 | 0.613 | 0.124 | 0.310 |

| 2-Factor | 10.289 | 0.562 | 0.514 | 0.139 | 0.356 |

| 1-Factor | 11.908 | 0.482 | 0.429 | 0.151 | 0.371 |

| Variable | DGIP | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2 | M3 | |

| Age | −0.003 | −0.029 | −0.033 |

| Scale | −0.021 | −0.022 | −0.006 |

| Category | 0.072 | 0.035 | 0.031 |

| Nature | −0.248 ** | −0.295 *** | −0.238 ** |

| EA | 0.288 *** | ||

| DIC | 0.442 *** | ||

| Constant | 4.521 *** | 3.514 *** | 2.719 *** |

| ∆R2 | 0.006 | 0.122 | 0.265 |

| F | 1.633 *** | 14.523 *** | 35.839 *** |

| Variable | CR | DGIP | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M4 | M5 | M6 | M7 | M8 | M9 | M10 | |

| Age | 0.026 | −0.012 | −0.005 | −0.003 | −0.009 | −0.025 | −0.032 |

| Scale | 0.032 | 0.029 | 0.046 | −0.022 | −0.029 | −0.024 | −0.011 |

| Category | 0.096 | 0.048 | 0.058 | 0.072 | 0.049 | 0.028 | 0.025 |

| Nature | −0.146 | −0.215 | −0.126 | −0.251 ** | −0.215 *** | −0.268 *** | −0.225 ** |

| EA | 0.395 *** | 0.225 *** | |||||

| DIC | 0.418 *** | 0.398 *** | |||||

| CR | 0.236 *** | 0.168 *** | 0.109 *** | ||||

| Constant | 2.638 *** | 2.299 *** | 2.635 *** | 2.299 *** | 2.472 *** | ||

| ∆R2 | 0.126 | 0.129 | 0.123 | 0.127 | 0.281 | ||

| F | 14.442 *** | 15.379 *** | 14.438 *** | 15.379 *** | 32.589 *** | ||

| Variable | CR | |

|---|---|---|

| M11 | M12 | |

| Age | −0.022 | −0.023 |

| Scale | 0.025 | 0.047 |

| Category | 0.064 | 0.086 |

| Nature | −0.218 | −0.154 |

| EA | 0.109 | |

| DIC | 0.052 | |

| CR | −0.356 ** | −0.468 *** |

| EA × ES | 0.064 *** | |

| DIC × ES | 0.086 *** | |

| Constant | 4.210 *** | 4.323 *** |

| ∆R2 | 0.134 | 0.512 |

| F | 11.578 *** | 13.419 *** |

| Variable | CR | DGIP | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M10 | M11 | M4 | M5 | M6 | M7 | M8 | M9 | |

| Age | −0.031 | −0.066 | −0.086 | −0.081 | −0.109 | −0.003 | −0.021 | −0.007 | −0.029 | −0.033 | −0.032 |

| Scale | −0.010 | −0.043 | 0.002 | −0.051 | 0.108 | −0.005 | −0.051 | −0.014 | −0.013 | 0.012 | 0.008 |

| Category | 0.052 | −0.006 | 0.037 | −0.022 | 0.048 | 0.069 | −0.019 | 0.048 | 0.025 | 0.028 | 0.023 |

| Nature | 0.382 *** | −0.015 | 0.168 *** | 0.217 *** | |||||||

| EA | 0.512 *** | 0.279 | 0.446 *** | 0.396 *** | |||||||

| DIC | 0.238 *** | 0.169 *** | 0.113 *** | ||||||||

| CR | −0.396 * | −0.278 | |||||||||

| EA × ES | 0.095 ** | ||||||||||

| DIC × ES | 0.058 | ||||||||||

| Constant | 4.182 ** | 2.916 *** | 2.123 *** | 4.739 *** | 3.318 *** | 4.056 *** | 3.792 *** | 3.188 *** | 2.613 *** | 2.276 *** | 2.052 *** |

| ∆R2 | −0.003 | 0.128 | 0.218 | 0.146 | 0.219 | −0.005 | 0.029 | 0.096 | 0.156 | 0.548 | 0.271 |

| F | 0.089 | 6.108 *** | 10.696 *** | 4.856 *** | 7.429 *** | 0.422 | 1.992 *** | 13.514 *** | 18.293 *** | 42.661 *** | 37.541 *** |

| Variable | CR | DGIP | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M10 | M11 | M4 | M5 | M6 | M7 | M8 | M9 | |

| Age | 0.009 | 0.016 | 0.031 | −0.003 | 0.012 | −0.019 | −0.049 | −0.028 | −0.049 | −0.042 | −0.046 |

| Scale | 0.052 | 0.063 | 0.068 | 0.056 | 0.052 | −0.013 | 0.003 | −0.022 | −0.006 | 0.007 | 0.005 |

| Category | 0.109 | 0.063 | 0.065 | 0.096 | 0.106 | 0.093 | 0.053 | 0.076 | 0.045 | 0.042 | 0.036 |

| Nature | 0.402 *** | 0.153 | 0.349 *** | 0.309 *** | |||||||

| EA | 0.376 *** | −0.083 | 0.462 *** | 0.438 *** | |||||||

| DIC | 0.196 *** | 0.106 ** | 0.078 ** | ||||||||

| CR | −0.348 ** | −0.573 *** | |||||||||

| EA × ES | 0.058 | ||||||||||

| DIC × ES | 0.109 *** | ||||||||||

| Constant | 3.568 *** | 1.972 *** | 2.031 *** | 3.500 *** | 4.849 *** | 3.983 *** | 2.614 *** | 3.304 *** | 2.412 *** | 2.115 *** | 1.968 *** |

| ∆R2 | 0.001 | 0.158 | 0.099 | 0.124 | 0.127 | −0.006 | 0.016 | 0.057 | 0.166 | 2.632 | 0.272 |

| F | 0.968 | 12.365 *** | 10.492 *** | 9.371 *** | 9.518 *** | 0.613 | 16.405 *** | 6.438 *** | 14.661 *** | 32.108 *** | 26.775 *** |

| Variable | CR | DGIP | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M10 | M11 | M4 | M5 | M6 | M7 | M8 | M9 | |

| Age | 0.038 | 0.008 | −0.015 | −0.016 | −0.088 | −0.027 | −0.046 | −0.036 | −0.045 | −0.086 | −0.085 |

| Scale | 0.018 | −0.006 | 0.039 | −0.042 | 0.003 | −0.043 | −0.055 | −0.048 | −0.055 | −0.023 | −0.025 |

| Category | −0.208 | −0.276 | −0.152 | −0.0376 | −0.259 | −0.482 ** | −0.516 *** | −0.442 ** | −0.483 ** | −0.418 ** | −0.409 ** |

| Nature | 0.382 *** | −0.015 | 0.208 *** | 0.159 ** | |||||||

| EA | 0.375 *** | −0.252 | 0.423 *** | 0.408 *** | |||||||

| DIC | 0.186 *** | 0.128 *** | 0.046 | ||||||||

| CR | −0.493 ** | −0.811 *** | |||||||||

| EA × ES | 0.098 * | ||||||||||

| DIC × ES | 0.158 *** | ||||||||||

| Constant | 4.203 *** | 2.872 *** | 2.624 *** | 5.273 *** | 6.332 *** | 5.065 *** | 4.351 *** | 4.298 *** | 3.989 *** | 3.281 *** | 3.162 *** |

| ∆R2 | −0.002 | 0.123 | 0.112 | 0.142 | 0.178 | 0.024 | 0.009 | 0.071 | 0.098 | 0.275 | 0.273 |

| F | 0.416 | 6.411 *** | 5.852 *** | 5.242 *** | 6.589 *** | 2.235 * | 4.3379 *** | 3.902 *** | 4.283 *** | 15.618 *** | 12.576 *** |

| Variable | CR | DGIP | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M10 | M11 | M4 | M5 | M6 | M7 | M8 | M9 | |

| Age | 0.066 | 0.046 | 0.088 | 0.028 | 0.072 | −0.012 | −0.032 | −0.029 | −0.039 | 0.011 | −0.003 |

| Scale | 0.013 | 0.018 | 0.028 | 0.036 | 0.048 | −0.032 | −0.028 | −0.036 | −0.032 | −0.018 | −0.025 |

| Category | −0.169 | −0.296 | −0.189 | −0.235 | −0.136 | −0.013 | −0.106 | 0.059 | −0.056 | −0.005 | 0.025 |

| Nature | 0.368 *** | 0.192 | 0.341 *** | 0.272 *** | |||||||

| EA | 0.462 *** | 0.431 | 0.423 *** | 0.359 *** | |||||||

| DIC | 0.259 *** | 0.179 *** | 0.136 ** | ||||||||

| CR | −0.386 | −0.186 * | |||||||||

| EA × ES | 0.049 | ||||||||||

| DIC × ES | 0.009 *** | ||||||||||

| Constant | 4.136 *** | 2.809 *** | 2.056 *** | 4.189 *** | 2.719 ** | 4.291 *** | 3.062 *** | 3.226 *** | 2.563 *** | 2.418 *** | 2.139 *** |

| ∆R2 | −0.015 | 0.088 | 0.142 | 0.112 | 0.152 | −0.018 | 0.149 | 0.102 | 0.198 | 0.223 | 0.246 |

| F | 0.308 | 4.857 *** | 7.628 *** | 4.348 *** | 5.782 *** | 0.113 | 7.882 *** | 5.453 *** | 8.723 *** | 12.234 *** | 11.268 *** |

| Variable | CR | DGIP | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M10 | M11 | M4 | M5 | M6 | M7 | M8 | M9 | |

| Age | −0.012 | −0.066 | −0.058 | −0.065 | −0.055 | −0.036 | −0.008 | 0.035 | 0.006 | −0.019 | −0.012 |

| Scale | 0.056 | 0.068 | 0.069 | 0.058 | 0.076 | −0.009 | 0.002 | −0.023 | −0.013 | −0.012 | 0.001 |

| Category | −0.061 | −0.074 | −0.075 | −0.062 | −0.083 | −0.263 | −0.273 | −0.249 | −0.258 | −0.281 * | −0.272 * |

| Nature | 0.429 *** | 0.081 | 0.308 *** | 0.238 *** | |||||||

| EA | 0.426 *** | −0.213 | 0.479 *** | 0.428 *** | |||||||

| DIC | 0.249 *** | 0.179 *** | 0.134 ** | ||||||||

| CR | −0.315 | −0.583 ** | |||||||||

| EA × ES | 0.073 | ||||||||||

| DIC × ES | 0.136 ** | ||||||||||

| Constant | 24.168 *** | 2.429 *** | 2.409 *** | 3.968 *** | 5.191 *** | 4.612 *** | 3.368 *** | 3.589 ** | 2.948 *** | 2.629 *** | 2.318 *** |

| ∆R2 | −0.018 | 0.118 | 0.099 | 0.115 | 0.121 | −0.006 | 0.124 | 0.109 | 0.173 | 0.278 | 0.305 |

| F | 0.178 | 6.648 *** | 5.698 *** | 4.728 *** | 4.921 *** | 0.778 | 7.118 *** | 6.279 ** | 8.108 *** | 17.572 *** | 16.012 *** |

| Previous Cause and Condition | High-DGIP | Low-DGIP | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consistency | Coverage Rate | Consistency | Coverage Rate | |

| EA | 0.702 | 0.56 | 0.581 | 0.586 |

| ~ EA | 0.618 | 0.609 | 0.759 | 0.708 |

| DIC | 0.716 | 0.728 | 0.658 | 0.612 |

| ~ DIC | 0.614 | 0.649 | 0.718 | 0.706 |

| CR | 0.692 | 0.765 | 0.579 | 0.601 |

| ~ CR | 0.638 | 0.619 | 0.773 | 0.702 |

| ES | 0.685 | 0.748 | 0.609 | 0.612 |

| ~ ES | 0.629 | 0.635 | 0.746 | 0.701 |

| Variable | DGIP | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Configuration 1 | Configuration 2 | Configuration 3 | |

| EA | ● | ● | ● |

| DIC | ⊗ | ||

| CR | ● | ||

| ES | ● | ||

| Consistency | 0.816 | 0.876 | 0.579 |

| Original coverage | 0.456 | 0.542 | 0.554 |

| Unique coverage | 0.043 | 0.039 | 0.026 |

| Overall coverage | 0.682 | ||

| Overall consistency | 0.813 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, Y.; Wei, Z. Executive Cognition, Capability Reconstruction, and Digital Green Innovation Performance in Building Materials Enterprises: A Systems Perspective. Systems 2025, 13, 1096. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13121096

Ma Y, Wei Z. Executive Cognition, Capability Reconstruction, and Digital Green Innovation Performance in Building Materials Enterprises: A Systems Perspective. Systems. 2025; 13(12):1096. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13121096

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Yonghong, and Zihui Wei. 2025. "Executive Cognition, Capability Reconstruction, and Digital Green Innovation Performance in Building Materials Enterprises: A Systems Perspective" Systems 13, no. 12: 1096. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13121096

APA StyleMa, Y., & Wei, Z. (2025). Executive Cognition, Capability Reconstruction, and Digital Green Innovation Performance in Building Materials Enterprises: A Systems Perspective. Systems, 13(12), 1096. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13121096