1. Introduction

The global energy transition has entered a critical phase, currently facing risks such as geopolitical frictions, slowing energy efficiency improvements, and delayed transitions. Without decisive action over the next decade, the world may fall into a predicament of “disorderly transition” [

1]. Cities, as the “front line” of the energy transition, require policymakers to be more resolute than ever before on the path to cleaner and deeper decarbonization [

2].

The energy transition is a synergistic evolutionary process in which political, economic, social and technological factors are linked and interact with each other to drive changes in the energy system [

3,

4]. Different actors, such as governments, companies, the public sector, research institutions and communities, form a specific social network by interacting and cooperating with each other [

5,

6]. What are the roles of local governments in the network? How do these roles influence the energy transition? While the existing literature has addressed the importance of policymakers in the energy transition and the factors that influence their decision-making [

7,

8], it rarely provides a rich portrait of government roles. Therefore, this study proposes a network analytical framework to semi-quantitatively describe the varying roles of local governments in the urban energy transition, shedding new light on the shaping process and driving mechanisms of the transition.

This study has three main contributions. In terms of theoretical contribution, this study systematically reveals the government-led governance logic in China’s urban energy transition and proposes a framework of “multiple roles” and “dynamic evolution” of local government. It elucidates how local governments, within a top-down policy system, bridge national strategies with local practices, foster collaborative networks, and shape the direction of the energy transition by acting in multiple roles. This deepens the theoretical understanding of the dynamic mechanisms beneath the transition in the Chinese context. In terms of methodological contribution, this study constructs an innovative and replicable analytical framework. By integrating social network analysis with textual analysis, it achieves the quantitative identification and longitudinal tracking of the structural changes in the government’s role. This approach provides a powerful tool for analyzing complex governance dynamics and demonstrates an empirical path that can be referenced for future research. In terms of practical contribution, the study provides a staged and role-based governance pathway that guides local governments to dynamically evolve from direct implementers and leaders in the initial stage, to pathway shapers and drivers during implementation, and ultimately to platform conveners and innovation catalysts in the expansion stage. This suggests that policymakers should focus on building networks and facilitating interactions among heterogeneous actors, which offers significant practical guiding value for energy transition strategies.

This study is structured as follows.

Section 2 begins with an exploration of the origins and key issues of the urban energy transition, and then systematically reviews the role of local governments.

Section 3 briefly introduces the research methodology of combining case studies and network analysis, including the selection of the case city, data sources, and processing.

Section 4 selects some key indicators to measure the networks at each energy transition stage.

Section 5 discusses the multiple roles of local governments and their changing influences in the energy transition based on the results of the measurements. Finally, we draw conclusions and present policy implications.

2. Literature Review

The concept of energy transition emerged from the energy dilemma and the environmental movement in Europe and the United States in the 1970s. In a broad sense, it refers to a radical, systematic and controlled change in energy supply and consumption patterns towards more sustainable or efficient directions, and resulting in more environmentally friendly impacts [

9]. The fundamental goal of the energy transition is to reduce energy consumption while shifting from traditional fossil fuels to clean and renewable energy (RE) such as wind and solar, with the ultimate aim of reducing carbon emissions and mitigating climate change [

10].

The main topics related to the energy transition include alternative energy sources, environmental impacts, energy use efficiency, and energy policy. In the 1980s and 1990s, the massive urbanization movement and the global climate crisis triggered discussions on sustainable urban development, which led to a series of emerging urban concepts that are closely related to energy governance and transition, such as eco-city [

11,

12], low-carbon city [

13], green city [

14], smart city [

15], and so on. Studies have been carried out on urban energy transition and carbon governance, some of which provide case studies to illustrate the roles and responses of local governments in different countries and regions.

Some studies have confirmed the positive role of city governments in the energy transition [

16]. In some European countries where environmental awareness has been established earlier, municipalities are shareholders in local energy utilities and intermediaries in influencing energy and climate policies [

17]. Governments in urban areas such as Almere and Rotterdam [

18], Stockholm [

9], Copenhagen [

19], and Munich [

20] have been actively involved in regional energy master planning since the 1990s. They have issued a package of climate action plans, including the establishment of urban climate networks, the creation of specialized administrative jurisdictions for climate policy, and the launch of regional projects to improve energy efficiency and promote renewable energy [

21]. In the U.S., cities with higher levels of governance such as Los Angeles [

22], San Francisco [

23], and New York City [

24,

25] have been more proactive in engaging in the energy transition and carbon management, despite the fact that the great uncertainty of climate policy at the national level and the traditional localism have led to many mitigation efforts at the municipal level [

26]. City councils in Sydney and Melbourne have demonstrated significant aggregation and influence in promoting local carbon reduction through policies, financial support and services in the implementation of renewable energy projects, and are therefore drivers of the urban energy transition [

27].

However, there are also some local authorities that are either reluctant to engage in, or play only a limited role in, energy and climate initiatives [

28]. For example, the marginalisation of local governments from governance in the UK after the Second World War has led to their generally limited role as niche actors in local energy governance, although in a few cities or towns, such as Aberdeen, Woking, Oxford City, and Surrey County, local authorities have increased their influence in matters of policy development, technological innovation, and community engagement in the regional energy environment [

29,

30]. In South Korea, the implementation of “the Green and Low-carbon City Plan” introduced by the central government has not been smooth at the local level, due to a willingness gap between the central and local governments [

31]. Cases from Cape Town and sub-Saharan urban areas show that, despite the abundance of local energy sources, urban authorities in the African region have largely acted in a climate policy vacuum [

32,

33]. Moreover, the lack of human resources, funding and expertise makes it difficult for them to play a leading role in addressing energy poverty [

34,

35].

While international case studies offer insights into urban energy governance, their application in the Chinese context requires extreme caution. Progress in green innovation, energy efficiency improvements, and clean energy deployment in Chinese cities has primarily relied on centrally driven pilot demonstration projects [

36,

37]. Strengthened central performance evaluations have also significantly incentivized improvements in local energy governance [

38,

39]. However, significant regional differences exist: path dependence, insufficient fiscal incentives, and weak administrative capacity continue to hinder energy transition in central and western regions and resource-based cities [

40,

41], while pilot demonstration projects in eastern and megacities with stronger governance capabilities and a more innovative spirit have been more effective [

42,

43]. While these characteristics resonate with international urban case studies [

18,

23], the governance logic differs significantly. Compared to the international model that combines independent and multi-party participation, China’s urban energy transition is still mainly led by the central government, with local governments playing multiple roles as promoters, coordinators and front-line implementers [

44].

In terms of research methodology, scholars have constructed classical qualitative analytical frameworks such as benchmarking comparisons, dimensions of transition and transition management based on desktop research, field surveys and on-site interviews. The network analysis framework has mainly been used to qualitatively discuss the operational mechanisms within cross-city climate networks and multi-level governance models [

28,

45,

46]. Nochta and Skelcher evaluated the opportunities and limitations of network governance to support low-carbon energy transition in European cities [

47]. In cross-city networks, municipalities are facilitators rather than commanders and implementers of climate governance actions. They must rely vertically on higher levels of government and horizontally on other actors and the social networks they comprise to perform their role [

48,

49]. The engagement and collaboration of local governments with other stakeholders is essential to bridge the gap between local action plans and national policy frameworks and to facilitate information-sharing and cross-scale learning [

50].

Although the importance of governments in the energy transition is widely acknowledged, research still offers limited insight into their specific roles and role dynamics within individual cities. In particular, studies rarely examine intra-city governance networks or provide semi-quantitative analyses that position governments within the broader transition network. Moreover, existing studies do not provide a sufficiently rich picture of the role of local governments in China’s energy transition. Exploring the different roles of local governments in the energy transition through an in-depth case study and network analysis of a Chinese city has both theoretical and practical significance. It not only enriches the literature on China’s specific context but also contributes to the strengthening of local governments’ awareness of their roles and responsibilities in the energy transition.

3. Research Methodology

Considering the exploratory and emergent nature of the focal phenomenon of this study, we adopted a case study approach, as it can reveal underlying processes that are difficult to separate from the context, thus helping to address the “how” question.

Subsequently, we employed a hybrid approach, integrating policy text analysis and dynamic social network analysis (SNA) to identify the multiple roles and changing influences of local governments in the urban energy transition.

Policy text analysis was primarily used for segmenting the transition stages and extracting social network nodes and edges. We first collected core energy planning documents and related policy texts at different levels, from the central to the local, to outline the basic logic of urban energy governance in China and identify the stage characteristics of Qingdao’s energy transition process. We further obtained data on Qingdao’s energy projects during the study period and used text analysis to identify key participants and their collaborative relationships.

Social network analysis was mainly used to identify the role and influence of the Qingdao municipal government in the energy transition.

This analytical framework fills a gap in semi-quantitative assessments of local government roles and offers methodological insights into the complexity of urban energy governance in China.

3.1. Case Selection

Qingdao exhibits typical characteristics of Chinese cities in terms of resource endowments, governance structures, and exploratory governance practices.

First, despite possessing favorable wind and solar resources, the city remains highly dependent on external energy supplies and faces challenges similar to those encountered by many Chinese cities undergoing industrial upgrading. In addition, the variation in resources, industrial bases, and development stages across its subordinate districts and county-level cities mirrors, to some extent, that observed among eastern, central, and western regions in China.

Second, Qingdao’s energy governance model represents a typical example of how central government planning is implemented at the local level. As a northern city, its policy initiatives rely heavily on central guidance and are shaped by local fiscal capacity, industrial structure, and governance strength. Since the central government launched a series of major action plans to advance the energy revolution in 2006, Qingdao has consistently acted as an active applicant for and implementer of central pilot programs. Its efforts in policy localization and innovative governance practices reflect—and can be generalized to—the action logic of many prefecture-level cities driven by central policy directives.

To enhance the generalizability of the case, this study incorporates Tianjin, Ningbo, and Qingdao—industrial port cities with comparable population scales—for a horizontal comparison. Since 2010, the three cities’ energy transitions have proceeded through three distinct periods with broadly similar trajectories. Their energy governance logic also aligns closely: driven by both external policy pressures and internal industrial structures, they have leveraged national fiscal support to begin their transition efforts with pilot projects, gradually progressing towards a systematic upgrade of traditional core industries and urban infrastructure, although the selected pilot areas had distinct local characteristics. See

Table 1.

These similarities suggest that the Qingdao case provides a broadly generalizable basis for examining the role of local governments in the early stages of urban energy transitions in China.

Finally, as a major global port, a C40 member city, and a municipality with independent administrative status, Qingdao hosts a complex governance network involving international organizations, multiple levels of government, state-owned enterprises, functional zones, and research institutions, making it well-suited for social network analysis. Meanwhile, its dynamic energy transition practices offer an effective window for the international community to observe the broader trajectory of China’s low-carbon transition.

3.2. SNA

This study employs social network analysis to identify the role and influence of local governments within energy-transition cooperation networks.

First, basic network indicators—such as size, density, and centrality—are examined to outline the overall structure of urban energy-transition cooperation networks. Next, a set of indicators is selected to capture different attributes of the network structure, enabling the identification and discussion of the multiple roles and influences of local governments within these networks. Theoretically, network structure shapes the distribution of power among stakeholders and the formation of their roles. As one actor among many in energy governance—including enterprises, institutions, communities, and higher-level governments—the functions, behavioral logic, and influence of local governments depend largely on their structural position in the network. For example, whether they are closely connected to other key actors, occupy positions similar to higher-level governments, or bridge otherwise disconnected groups directly affects whether they act as controllers, coordinators, resource integrators, or even innovation catalysts. Accordingly, indicators related to eigenvector centrality, structural equivalence, and structural holes are employed to determine the local government’s central position, its positional relationships with higher-level governments and other clusters, and its bridging or control advantages over heterogeneous information resources.

It should be noted that traditional social network analysis generally focuses on static networks. In contrast, dynamic network research examines changes across two or more time periods, enabling researchers to uncover the interaction mechanisms between network structure and node behavior, as well as the underlying patterns of network evolution. In this study, the selected indicators are applied to measure and compare networks across three stages, thereby revealing how the role and influence of local governments evolve over the course of the energy transition.

3.3. Data Collection and Deposition

This study covers the period from 2010 to 2020. China’s urban energy transition has progressed for approximately a decade, and key institutional and policy shifts—including those in Qingdao—were largely concentrated within this period. After 2020, various disruptions in urban energy governance reduced the continuity and reliability of subsequent data. Moreover, institutional formation and early path dependencies are widely recognized as shaping long-term transition trajectories [

60,

61]. The selected timeframe is therefore appropriate for examining governmental roles and their effects.

Drawing on milestone events identified in the “Qingdao Low-Carbon Development Plan (2014–2020)” and the Implementation Scheme for “Qingdao’s Low-Carbon City Pilot”, and aligning them with the city’s actual transition progress, this study divides Qingdao’s early transition into three stages: initiation (2010–2013), implementation (2014–2016), and implementation expansion (2017–2020).

3.3.1. Data Sources and Retrieval

The analysis begins with the construction of a keyword system. Based on national and local Five-Year Plans and energy policy documents issued since 2005, and on the list of major energy projects in Qingdao during 2010–2020 (see

Table A1 in

Appendix A). Guided by these sources, we conducted a semantic review of each project to extract three categories of attribute keywords: administrative jurisdiction, energy attributes, and energy activity types (see

Table A2 in

Appendix A). Jurisdictional keywords refer to Qingdao and its subordinate districts; energy-attribute keywords involve energy sources, production and processing methods, and clean or renewable features; and activity-type keywords include facility construction, energy-efficiency and emission-reduction measures, low-carbon retrofits, coal-to-electricity substitution, and network upgrades.

Cross-platform searches were conducted using individual and combined keywords to collect data on energy projects planned, initiated, or constructed in Qingdao during 2010–2020. Given China’s regulatory requirements, most energy projects undergo public bidding, and relevant information is published on government and procurement platforms. The primary data sources consist of the China Government Procurement Network and provincial and municipal public resource trading platforms, supplemented by industry-specific bidding websites (see

Table A3 in

Appendix A). The projects span energy production and supply, transmission networks, and end-use activities. Additional information from authoritative media outlets and corporate websites was used to supplement major activities not published on bidding platforms.

3.3.2. Data Cleaning

To ensure data reliability and consistency, a systematic data-cleaning procedure was applied.

First, a preliminary screening retained projects that met the following criteria: (1) occurred from 2010 to 2020; (2) related to energy production, transmission, consumption, management, or low-carbon pilots; (3) contained identifiable information on actors, locations, and timestamps; and (4) documented by at least one credible source (e.g., government, enterprises, procurement platforms, or official media). This yielded 1014 project records, approximately 45% of which concentrated during 2017–2020.

Second, duplicate removal was conducted. As the period coincided with extensive state-owned enterprise reforms, mergers, name changes, and subsidiary restructurings were common. Relevant entities were therefore consolidated, and entity names were standardized to their most recent forms. Project names were matched using string-matching techniques, and duplicates across platforms were identified based on project name, actors, and timestamps.

After cleaning, a project database was constructed containing fields such as time period, administrative location, project title, actors, and attributes. Actors included project owners (e.g., investors or initiators) and contractors. Across the three periods, the final dataset includes 172, 123, and 449 projects, involving 20, 33, and 80 project owners, and 102, 90, and 318 contractors, respectively.

3.3.3. Standardization and Coding

For name standardization, each entity’s most recent legal name (from the National Enterprise Credit Information System) was used. Subsidiaries within the same corporate group were distinguished based on their roles in the project; when necessary, a “Subsidiary–Group” format was adopted. Government and public institutions were differentiated by functional departments.

Prefix codes were assigned as follows: CN—(central units), SD—(Shandong provincial units), QD—(Qingdao municipal or district units), and OP—(organizations outside the province). Local enterprises were allowed to omit the QD—prefix.

Suffix codes include GOV (government departments), RI (research institutes or universities), PS (public service institutions), and standardized abbreviations or pinyin for enterprises.

Following standardization, actors include firms, government agencies, research institutions, and public service organizations. CN-GOV denotes central government departments; QD-GOV refers to municipal and district-level departments.

3.3.4. Nodes and Edges in Network Construction

Actors serve as nodes, and collaborative ties form the edges. Cooperation is identified when two or more actors appear in the same project; multi-actor projects are treated as fully connected, with no edge weights assigned. The three periods (2010–2013, 2014–2016, 2017–2020) are defined based on project time information, with cross-period projects assigned to the year in which construction began. All networks are constructed as undirected and unweighted.

These procedures established the three cooperation networks for Qingdao’s energy transition from 2010 to 2020, as shown in

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3.

4. Measures and Results

The core work of social network analysis is to describe the network structure, the position of the nodes and their roles through some quantitative metrics [

62]. We first calculated the size, density, and centrality of the network at each stage, and the results are shown in

Table 2.

In terms of network scale, the number of participants in energy projects remained relatively stable from Stage I to Stage II. However, in Stage III, during the 13th Five-Year Plan period (2016–2020), the network expanded substantially, surpassing the combined scale of the first two stages. This reflects a marked acceleration of the energy transition, as energy system development and optimization began to affect multiple urban domains, each involving numerous actors, thereby increasing the overall complexity of the energy governance network.

Network density reflects the level of cooperation among stakeholders. Across all three stages, density values indicate relatively loose cooperation and a limited structural influence on individual nodes. Network density decreased substantially from Stage II to Stage III (from 0.0096 to 0.0029).

Network centrality reflects the concentration of power or resources within the network. Measurements show a continuous rise in centrality from Stage I to Stage III, suggesting that a small number of nodes have increasingly strengthened their control, resulting in a growing concentration of network power and resources.

In summary, as the transition advances, urban energy governance networks exhibit a dual trend of expanding scale and the continuous reinforcement of core actors’ dominance.

To verify the stability of these network characteristics, this study employed the Quadratic Assignment Procedure (QAP) to test network density and centrality in Stage III. With 5000 permutations, the low level of network density remained marginally significant (p = 0.062), whereas the high level of network centrality reached a significant level (p < 0.003). These results confirm the increasingly prominent pattern of “scale expansion and dominant strengthening” in urban energy governance networks.

4.1. Eigenvector Centrality

Node centrality is a fundamental metric in network analysis used to assess the relative importance of nodes within a network. Eigenvector centrality, derived from the adjacency matrix, takes into account not only the number of a node’s connections but also the importance of its neighboring nodes, making it well-suited for capturing global network patterns. The principle of the algorithm is described in Algorithm A1 in

Appendix B. In this study, we used the metric to assess node importance within the transition network. The ten most important nodes in each stage are shown in

Table 3.

In Stage I, QD-GOV exhibits the highest centrality (0.587) and clearly occupies the structural center of the network, followed by CN-GOV (0.427). These two nodes hold substantially higher centrality than all others. Aside from QD-RI, which ranks third, the nodes in fourth to tenth positions share identical centrality values (0.155), forming a secondary core whose members exhibit largely indistinguishable levels of importance.

In Stage II, QD-GOV and CN-GOV continue to dominate the network, though their relative positions shift. The centrality of QD-GOV rises to 0.628, while that of CN-GOV declines to 0.247, suggesting an increasing concentration of influence within the municipal government. Meanwhile, the prominence of SD-GOV, several overseas actors, and QD-PS increases, breaking the homogeneity of the previously uniform secondary core.

In Stage III, QD-GOV’s centrality further increases to 0.685—far surpassing that of the second-ranked node, QD-PS (0.142). The centrality values of all remaining nodes are lower than in earlier stages, producing a more flattened distribution. These nodes primarily fall into three categories: public service institutions (PS), research institutions (RIs), and enterprises. Notably, overseas actors no longer appear among the top-ranked nodes.

Overall, QD-GOV consistently remains the most influential actor across all stages, and its dominance intensifies as the transition unfolds.

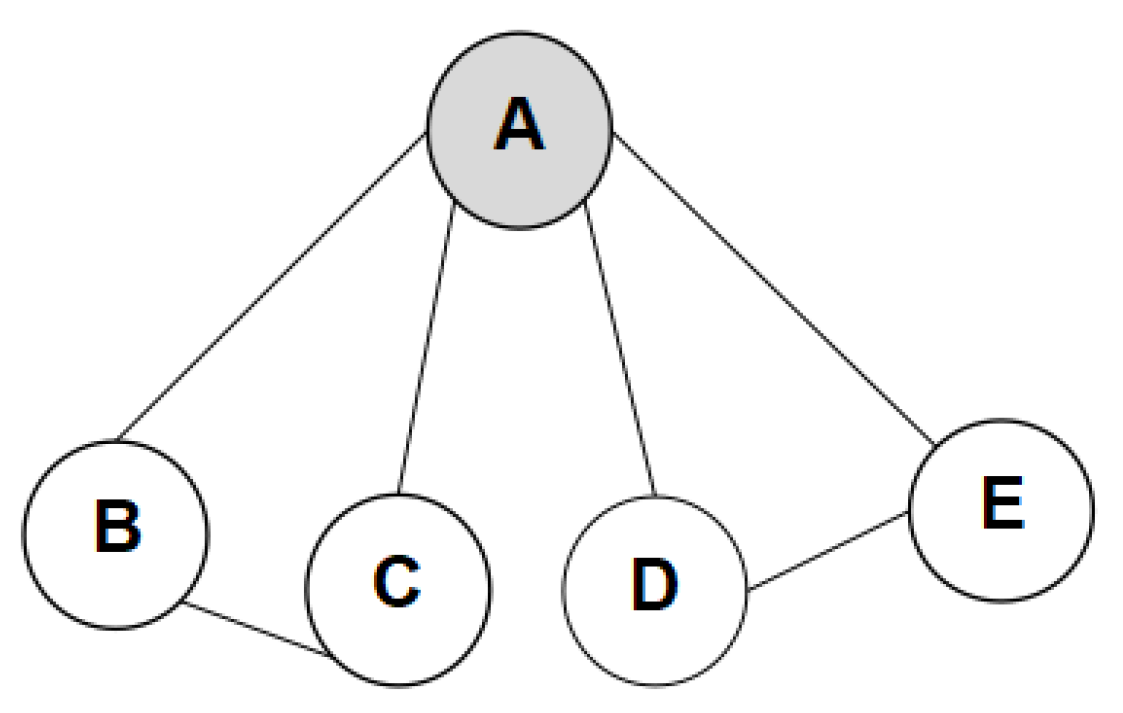

4.2. Structural Equivalence

Structural equivalence is another important concept for describing the positions and roles of network nodes. It denotes the extent to which two nodes occupy the same or similar relational positions—that is, whether they are connected to the same targets in comparable ways (see

Figure 4).

Nodes A and B are linked to the same nodes—C, D, and E—and thus occupy identical positional relationships in the network. Such nodes typically display similar behaviors, functions, and roles, and are therefore to some extent substitutable within the network. In this study’s energy-transition network, structural equivalence often appears among departments or firms with similar mandates. For example, if the Qingdao Environmental Bureau (QD-ENV) and Energy Bureau (QD-ENE) cooperate with the same set of energy firms and research institutions, they are considered structurally equivalent even in the absence of direct interaction.

To measure structural equivalence, the nodes and their associations must first be clustered according to predefined rules and divided into subgroups representing different positions. These subgroups are then converted and correlated to form a network of subgroups.

In this study, the convergent correlation algorithm and the block model approach are used to derive positional divisions for nodes in the original network and in the subgroup network. See Algorithm A2 in

Appendix B for the detailed methodology. The top 10 nodes in each stage were partitioned into eight distinct positions, summarized as follows.

Stage I, (QD-GOV, CN-GOV); (QD-RI, OP-CECEP, HSGE, MESNAC, Sailun, TGOOD, OP-CNOOC, CRSTC).

Stage II, (QD-GOV, CN-GOV, SD-GOV); (OP-AUS, OP-PNG, OP-SINOPEC); (CRSTC, Haiba); (QD-PS); (QD-RI).

Stage III, (HTTPC-DY); (SD-Yitong, Huapeng); (QD-PS, Fenghe); (QD-GOV, OP-RI); (QD-RI, Anjian, SD-RI).

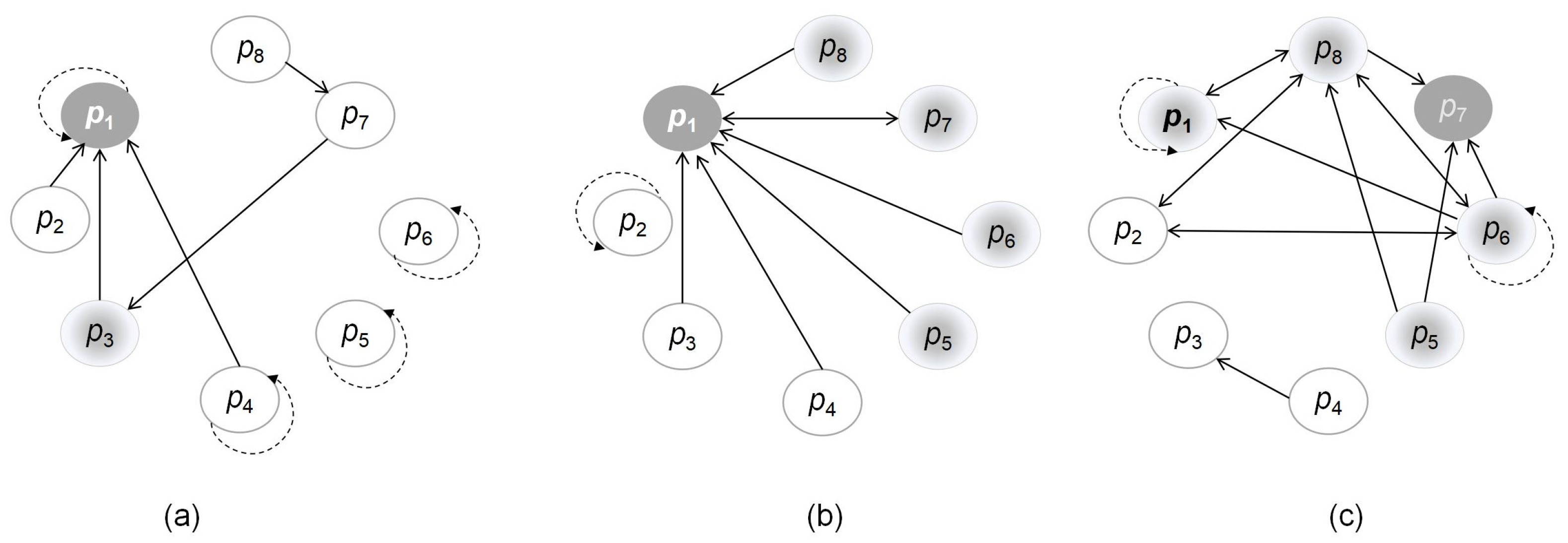

These positions form the subgroup network shown in

Figure 5. The government’s position remained largely consistent across periods, namely

(QD-GOV, CN-GOV),

(QD-GOV, CN-GOV, SD-GOV),

(QD-GOV). This means that governments, as important actors, have structural equivalence in the network and therefore play the same or similar roles. The subgroups containing these governmental roles are called governmental subgroups.

The dark gray position represents the government subgroup, the light gray gradient color indicates the subgroup containing other important actors, the arc-shaped dashed arrow indicates the existence of an internal connection in this subgroup, the one-way arrow line from subgroup to indicates that sends a cooperation request to , and the two-way arrow line indicates the existence of a bilateral cooperation relationship between two subgroups.

The structure of the subgroup network in the initial stage is relatively loose. The governmental subgroup is at the local centre of the network, as only a few non-governmental subgroups have established unilateral cooperation with it. In the second stage, the subgroup network evolved into a typical monocentric structure with the government subgroup in absolute control. In the third stage, the network structure is multi-layered and multi-centred. There is a significant increase in the linkages between the non-governmental subgroups. Among them, and have established unidirectional or bidirectional links with several subgroups, respectively, thus becoming some other important subgroups besides the government subgroup. Overall, the governmental subgroup remains at the top centre, and its influence on the non-governmental subgroups has evolved from horizontal diffusion in the second stage to vertical penetration.

4.3. Structural Holes

Structural holes refer to the absence of ties between otherwise unconnected actors or subgroups in a network, representing non-redundant relationships. Actors located at these “gaps” can span these gaps and gain brokerage advantages by accessing diverse information and exercising control over resource flows. When a node connects two otherwise unconnected actors or subgroups, it occupies a structural hole position (see

Figure 6).

Such nodes—referred to as structural-hole spanners—bridge heterogeneous information and resources across groups and enhance learning and innovation by integrating these disparate inputs. Consequently, they tend to hold greater control and innovation potential within the network. The prominence of this effect is particularly evident in low-density networks. Based on the connections between a structural-hole occupant and the nodes on either side, the roles it assumes can be categorized as learner, convener, or transmitter. Its role directly affects the function and evolutionary trajectory of the network. Are local governments also occupants of structural holes in low-density, loosely structured urban energy transition networks? What roles do they assume in the diffusion of energy transition technologies and resource allocation? This study discusses subgroup networks and individual networks separately.

For subgroup networks with few nodes and a simple structure, as shown in

Figure 5, the occupants of structural holes can be identified directly based on the principle of structural equivalence. The government subgroup occupies more structural holes in the second stage than in the first, indicating greater aggregation and control of heterogeneous resources. The government subgroup occupies more structural holes in the second stage than in the first stage, indicating increased aggregation and control of heterogeneous resources by the government subgroup. In the third stage,

,

, and

are independent of each other and form multiple structural holes that are all occupied by

; the structural holes formed between

and

are jointly occupied by

and

, although

is at the upper level of

, i.e., the information and resources of

ultimately flow to the government subgroup.

Identifying structural hole spanners in the form of individuals can be achieved using the Network Constraint Index (NCI), which can be further combined with an efficiency value to measure the influence of structural holes. The value of NCI indicates the degree of constraint to which a node is connected to other nodes. A smaller value of NCI indicates that the node is likely to occupy a larger number of structural holes. Conversely, a higher value indicates a higher degree of network closure and a lower number of structural holes occupied by the node. The efficiency, on the other hand, indicates the percentage of other nodes connected to that node that are not connected. When the efficiency value approaches 1, this indicates that there is essentially no direct connection among the other nodes connected to the node. Combining the above two metrics to measure the structural holes of node QD-GOV in the energy transition network, we obtained the NCI values of 0.102, 0.023, and 0.008 and the efficiency values of 0.969, 0.999, and 0.999, respectively. This suggests that the node QD-GOV may occupy more than one structural hole in the network in each stage and that other nodes connected to it have few direct connections with each other. Therefore, the node QD-GOV has a strong influence on information and technology intermingling.

5. Discussion

Municipal policymakers are becoming increasingly important in the critical energy transition through planning, government procurement, direct investment, and regulation [

16]. This section portrays the different roles played by local governments based on the above network measurements and Qingdao’s energy transition practices.

5.1. Leaders and Drivers

The Qingdao case illustrates that in China’s urban energy transition, local governments primarily function as leaders and drivers. They shape the transition through agenda-setting and planning, steer energy development via key demonstration projects, and mobilize wider societal participation through pilot initiatives.

Eigenvector centrality provides the clearest evidence of this role. Since the launch of the energy transition initiative in 2010, QD-GOV has consistently remained the dominant node in the network. Its centrality increases from 0.587 (Stage I) to 0.685 (Stage III), indicating that—even as the network expands substantially in Stage III with more projects and actors—the influence of the municipal government is not diluted but rather continues to strengthen.

This strengthening influence is grounded in Qingdao’s policy practices. Textual analysis of the city’s core plans and policy documents from 2005 to 2022 (see

Table A4 in

Appendix A) shows that the local government sets a clear transition agenda. Through the design and implementation of key demonstration projects, it guides the direction of energy development: only actors whose activities or technologies align with these projects tend to emerge as high-value nodes. Moreover, the frequent use of action-oriented terms such as “accelerate”, “promote”, and “strengthen” in documents related to project implementation signals the government’s proactive effort, as a driver, to foster broader participation in energy governance.

5.2. Pathway Shapers

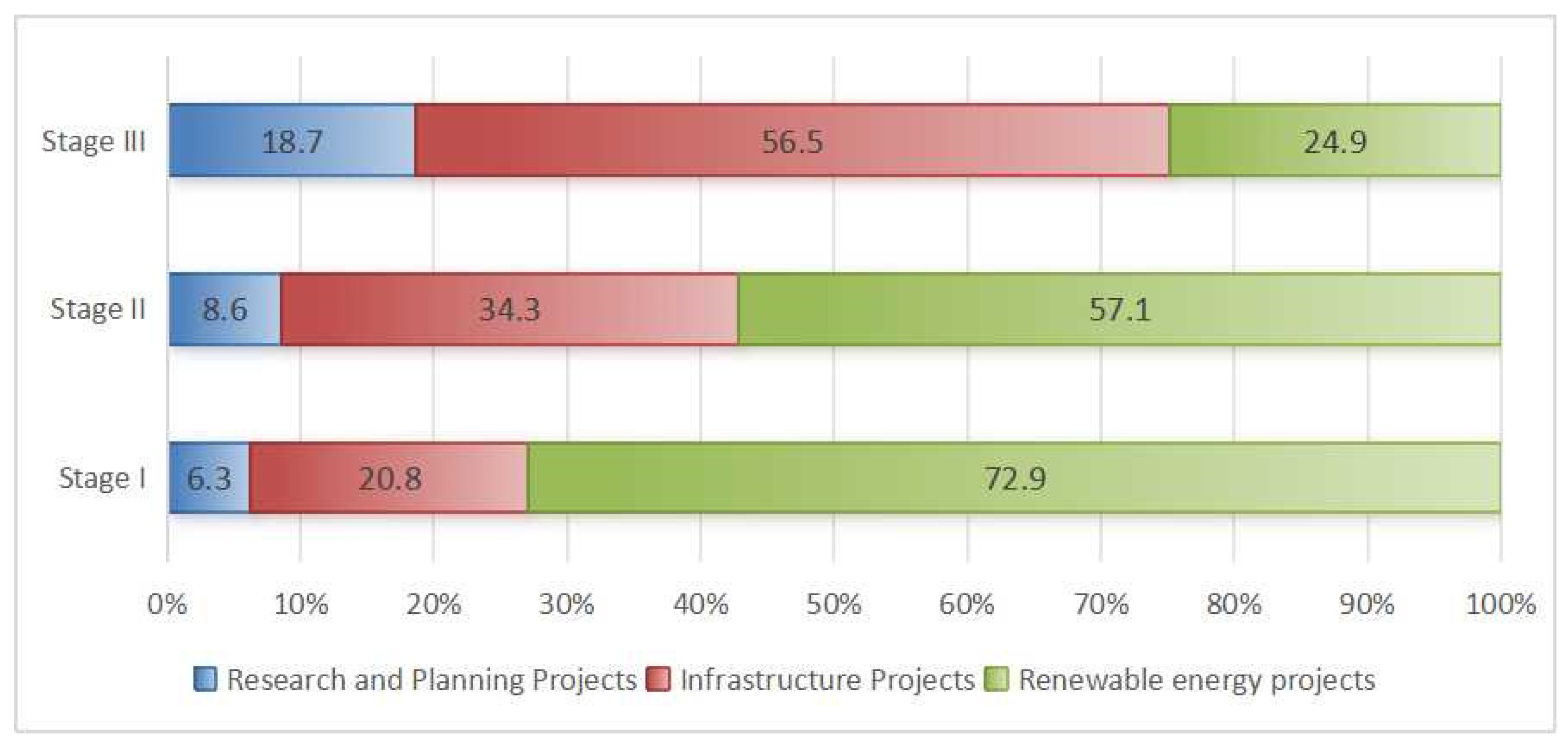

This section examines the role of local governments in shaping the development of urban energy systems and optimizing technological pathways through project investment and construction. This study defines this role as that of a pathway shaper.

An in-depth analysis of node attributes and project collaborators shows that local governments participate in 27.9%, 28.5%, and 43% of all projects across the three periods, respectively, making them the most significant participants in every stage of project investment and construction. Their involvement increases substantially as the transition progresses, and their influence on technological pathway formation continues to strengthen. By Stage III, local governments participate in nearly half of all projects, indicating their evolution from major participants to indispensable pathway definers. The collaborators involved in these government-led projects broadly fall into three categories—research and planning, infrastructure, and renewable energy—and their evolution is illustrated in

Figure 7.

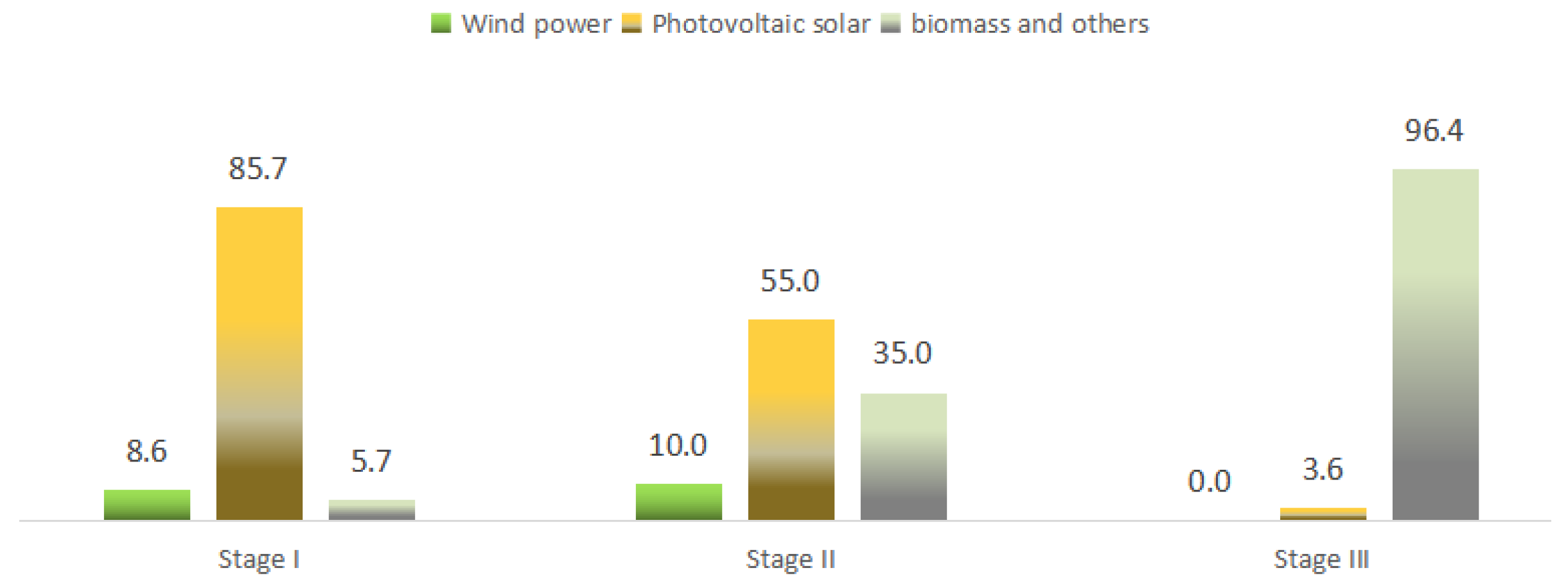

5.2.1. Renewable Energy Development and Utilisation

Renewable energy is a key technological pathway for China to achieve its 2030 targets and optimize its energy system [

63]. From 2010 to 2016, local governments’ pathway-shaping role was reflected in the initiation and construction of a large number of renewable energy projects, including wind, solar, and biomass.

Figure 8 shows the proportion of collaborators involved in these projects across the three periods.

Wind power projects involve large investments but relatively few participants. To attract partners, local governments included the wind power equipment industry in their catalogues of strategic emerging industries in 2011 and introduced a series of supportive measures related to land approvals, fiscal and financial services, and price subsidies. They also established project development service companies. Through these entities, the government not only participated in the preparatory stages of project development but also facilitated the strategic restructuring of the traditional state-owned energy enterprise, the Datang Group, together with emerging wind equipment manufacturers. These efforts have provided critical support for the operation and commissioning of projects such as the Datang (Qingdao) Wind Farm.

Partners in photovoltaic solar projects were mainly engaged in project construction during the first two periods. Qingdao was designated a “National Renewable Energy Building Application Demonstration City” and a “Renewable Energy Application Demonstration Center”, receiving central government subsidies of 98 million yuan in 2011 and 409 million yuan in 2013. These incentives attracted a range of new-energy companies, public utilities, and real estate developers to participate—under municipal leadership—in a series of green and low-carbon building demonstration projects involving shallow geothermal systems, solar thermal applications, and photovoltaic power generation.

Collaborators from the biomass, geothermal, and wastewater treatment sectors emerge as key practitioners in shaping renewable-energy pathways during the third period. Biomass cogeneration and municipal solid-waste incineration power generation led by Hengyuan Thermal Power have even surpassed wind and solar in electricity production.

The government’s sustained efforts have led to a marked improvement in the city’s energy structure. By 2020, renewable energy accounted for 23.4% of total electricity generation, compared with only 6.7% in 2015.

5.2.2. Infrastructure Renovation

Entering Stage III, the government’s role deepens from nurturing specific industries to restructuring the city’s energy infrastructure. Infrastructure upgrades drive technological progress and efficiency gains, substantially improving energy use efficiency and emissions-reduction performance [

64,

65]. Major projects in this period include the Qingdao LNG receiving terminal in Shandong, the expansion of urban natural gas pipelines, and the deployment of clean-energy heating systems for utilities. Correspondingly, several relevant participants—such as Australia Pacific LNG Limited (OP-AUS), ExxonMobil Papua New Guinea (OP-PNG), and Sinopec (OP-SINOPEC)—appear among the top ten nodes in the energy-transition network. Local governments also provide significant financial support to enhance the efficiency of urban energy processing, conversion, and recycling.

5.2.3. Research and Planning

From 2017 to 2020, the proportion of research and planning projects has risen significantly, which means that the local governments are exploring the energy transition in a more forward-looking way. For example, they cooperate with universities and research institutes to develop new energy vehicles, smart grids, and hydrogen energy. Platforms such as the Shandong Energy Research Institute and the Qingdao New Energy Laboratory have been created to enhance the city’s scientific and technological innovation capacity in the field of new energy. In this study, the research and planning groups involved in the above projects are divided into three categories: local, provincial and external. They all appear in the list of important nodes in

Table 3.

In summary, from renewable energy deployment to infrastructure upgrading and, more recently, to research and planning in emerging energy domains, the influence of local governments on the technological pathways of urban energy systems has become increasingly pervasive and far-reaching.

5.3. Implementers and Duty-Bearers

Under China’s vertical allocation-based administrative system, multi-tasking contracts issued by upper-level governments as principals are usually carried out by lower-level governments as agents, who must be guided, supervised, and assessed by their superiors. For example, Qingdao has been listed as the second batch of national low-carbon city pilots according to the document NDRC [2012] 3760. The local governments formulated a corresponding implementation programme in 2013. After the programme was agreed by the NDRC, several major PV solar projects as well as infrastructure projects, such as LNG receiving terminals and oil and gas pipeline network construction, were launched, which were financed by special state grants. In July 2023, the Department of Climate Change Response of the Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China assessed the progress of the pilot low-carbon cities. The role and influence of the central government are reflected in

Table 3. Its eigenvalue ranked second in the first two stages, but decreased from 0.427 to 0.247, indicating that the role of the central government as planner or the local government as implementer is weakened. In the third stage, the latter part of the 13th Five-Year Plan period, local governments are more concerned about their role as duty-bearers, fulfilling top-down tasks on schedule and being evaluated by their superiors.

The same relationship of roles between the upper and lower levels exists between municipalities and grassroots jurisdictions, making governments a distinct subgroup within the network. It can be seen that in China, the role of city governments as planners and decision makers is assigned by their superiors, and they are, in fact, the implementers and duty-bearers of the energy master plan.

It is worth mentioning that Qingdao is a sub-provincial city directly responsible to the central government, and its energy development is more guided by national planning and policy. This explains why the provincial government is less prominent than the central government in the network. In the second stage, the provincial government becomes the third important node due to its joint participation with Qingdao’s city government in the Shandong LNG project, which is a major national energy project. In addition, the Shandong government has provided significant financial support for Qingdao’s Green Power for Industry Plan and Air Pollution Prevention Plan, which has effectively driven the city’s energy transition.

5.4. Conveners and Catalysts

The structural holes and NCI measurements reveal the unique role played by city governments in the aggregation of heterogeneous information resources and the diffusion of emerging knowledge and technologies, as well as the evolution of their influence.

As shown in

Figure 5, the government subgroup occupies multiple structural holes in different stages of the energy transition and has a strong ability to aggregate cross-border information and resources. In particular, in the second stage, the influence of the government subgroup is at its maximum. In the third stage, the convening ability of the government subgroup at

is weakened by the declining status of the CN-GOV and SD-GOV nodes in the network. In practice, this is the result of the reform of China’s administrative approval system, which focuses on the principle of “release, manage and serve”, i.e., the transition of government functions from a control-oriented model to a service-oriented one, so as to improve the business environment and stimulate the vitality of market players. In this stage, city governments draw in heterogeneous information and resources mainly from participants located in different subgroups, especially research institutions. Among them, QD-RI and SD-RI belong to the

subgroup, which occupies several structural holes. Each of them engages in bilateral cooperation with enterprises and public service organizations in other subgroups, and their intellectual outputs are consolidated within the governmental subgroup—led by the municipal government—through mechanisms such as public funding and policy incentives. In addition, local governments are acquiring cutting-edge knowledge and technology for the energy transition through collaboration with research institutes outside the province.

On the other hand, a series of low carbon and clean energy exhibitions and summits organized locally provide city governments with a new role as catalysts for innovation, i.e., to build platforms for enterprises, industry associations, investors, research institutes, as well as users to exchange ideas and learn from each other, and to facilitate and accelerate technological convergence and innovation in the energy industry. This also feeds into the government’s planning capacity. Since 2015, Qingdao has released strategic plans for new energy vehicles, waste incineration and hydrogen energy. The decline in the NCI values—from 0.102 to 0.023 and finally to 0.008—indicates a clear strengthening of QD-GOV’s roles as a convener and facilitator.

Based on the above role analysis and the results of the relevant indicator measurements, we present

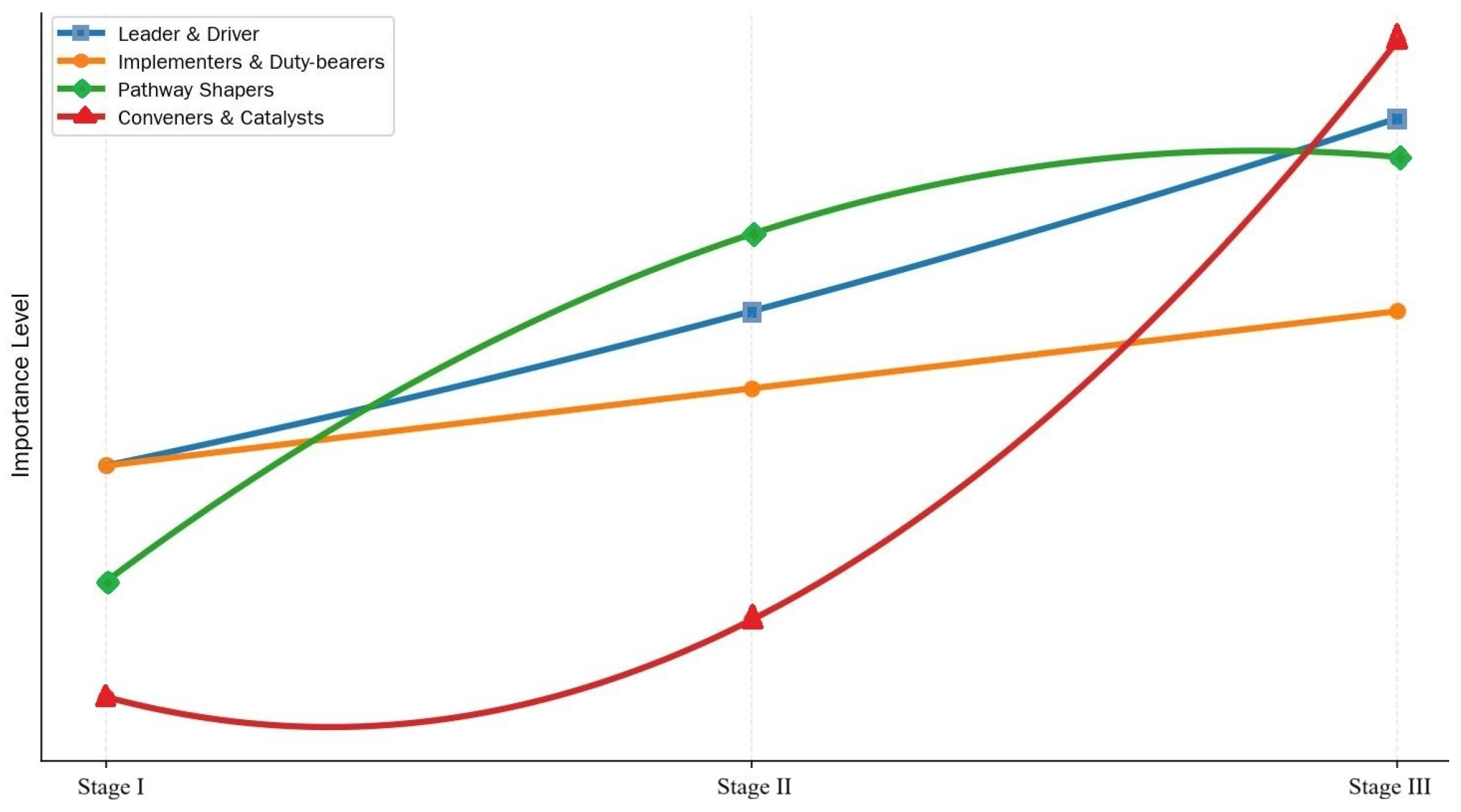

Figure 9, which illustrates how the roles and influence of local governments evolve across different stages of the energy transition. Along the horizontal axis, local governments perform all of these roles simultaneously at each stage, and their influence generally increases as the transition progresses; the most pronounced role is that of convener and promoter, largely driven by the continuous advancement of government digital transformation since 2015. Along the vertical axis, although local governments perform multiple roles within the same stage, the degree of influence associated with each role varies.

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

6.1. Conclusions

This study adopts a case-study design that integrates social network analysis with textual analysis to systematically reveal the roles, influence, and evolutionary dynamics of government in Qingdao’s energy transition from 2010 to 2020. The findings show that as the transition progresses, the scale of the actor network involved in energy governance expands rapidly and its structure becomes increasingly complex. Yet, power within the network simultaneously becomes more concentrated in the hands of local governments, illustrating a governance model in China’s energy transition that is strongly government-led.

The key roles played by local governments in the transition can be grouped into four categories. First, as leaders and drivers, they set the transition agenda and mobilize broad societal participation. Second, as path shapers, they exert substantial influence on technological upgrading and the overall improvement of the urban energy system through direct involvement in project investment and construction. Third, as implementers and carriers of responsibility for higher-level plans, they translate national strategies into measurable performance targets within a top-down governance hierarchy. Fourth, as conveners and catalysts, they bridge diverse and heterogeneous information and resource flows, activating the innovative capacity of the urban energy system.

The evolution of local governmental roles and influence displays distinct stage characteristics. In the initial stage (Stage I), local government primarily acts as an “implementer of higher-level plans” and as a “leader”, launching urban energy-transition pilots by securing policy support and beginning to shape the transition pathway.

In the implementation stage (Stage II), its roles as “driver” and “path shaper” become increasingly visible, while its leadership role is further reinforced. Through ongoing financial support and targeted construction funding, it participates deeply in renewable-energy development and attracts a wide range of partners, thereby consolidating its central position in the network. Meanwhile, by engaging with diverse domestic and international actors, it begins to exhibit the characteristics of a “convener”.

In the implementation expansion stage (Stage III), its leadership in infrastructure transformation and in research and development of emerging energy technologies makes the “path shaper” role even more prominent. At the same time, strengthened by administrative reforms toward service-oriented and digital governance, its influence as “leader” reaches its peak. Yet its function evolves from that of a direct “controller” to that of a “catalyst” for the innovation ecosystem, most notably through building platforms that enable direct interaction among heterogeneous stakeholders.

Overall, this study provides new insights into the governance logic of urban energy transition in the Chinese context. Within a top-down policy system, local governments display strong role multiplicity and adaptability, assuming different functions across governance levels. Through localized practices, they gradually implement national strategies and, in turn, drive the broader evolution of the energy transition from the local to the national scale. The introduction of a multidimensional perspective through network analysis enables this study to quantitatively identify the structural changes in the government’s role over time, providing a new analytical framework for understanding the governance mechanisms of urban energy transition. Simultaneously, it demonstrates a replicable research path for the international community to examine how local actions converge and drive national and even global sustainable development.

6.2. Policy Implications

Local governments are not only core actors in regional energy transition but also crucial forces in advancing global carbon neutrality. At different stages, they must dynamically adjust their roles and responsibilities, promoting a more resilient and higher-quality transition trajectory through institutional innovation and effective multi-level coordination.

6.2.1. Initiation Stage: Strengthening the Roles of Implementer and Leader

Within China’s top-down governance system, municipal governments serve as essential intermediaries linking national strategies with local practices. At this stage, local governments should prioritize their function as implementers of higher-level plans, effectively introducing national policy resources and legitimacy into local governance networks. At the same time, given the relatively weak capacity of market and societal forces, they should take on a proactive leadership role. By launching core demonstration-oriented projects, governments can attract and guide diverse actors—including enterprises, financial institutions, research organizations, and communities—intentionally constructing a collaborative governance network with government at its center and laying the foundation for the deeper progression of the energy transition.

Specific policy recommendations include the following:

Formulating energy transition action plans that align with local resource endowments and industrial structures, thereby providing clear and stable policy expectations for stakeholders.

Selecting demonstration projects with strategic significance, policy synergy, and industrial spillover potential that align with key national priorities, to enable cities to fully utilize policy dividends and resources, strengthen industrial-chain linkages, and rapidly build cooperative networks. These projects should also possess high public visibility to signal commitment to transition and foster wider societal participation.

Prioritizing the introduction of state-owned enterprises, leading private firms, and integrated energy service providers (ESCOs) with technological, financial, or integrative strengths to quickly form a capable core group of collaborators.

6.2.2. Implementation Stage: Emphasizing the Roles of Path Shaper and Driver

In the implementation stage, although the governance network becomes more diversified, local governments continue to occupy a “single-center” position. They should leverage this centrality to shape the city’s energy-transition pathway and accelerate the transition by selecting, supporting, and guiding various types of projects. While maintaining necessary leadership, they should also intentionally cultivate secondary centers to steer the system toward greater resilience and sustainability.

Specific measures include the following:

Establishing a dynamic evaluation mechanism for urban energy transition, identifying and prioritizing mature renewable energy projects with strong transition performance, and designing tailored promotion strategies based on project characteristics and applicable scenarios.

To avoid the vulnerabilities of a single-center network structure, the government should systematically cultivate market-oriented central nodes—such as virtual power plant (VPP) conveners and regional energy-storage operators—in targeted regions or sectors, thereby forming a transition pathway led by the government and jointly governed by multiple stakeholders.

6.2.3. Implementation Expansion Stage: Transitioning to Convener and Catalyst Roles

As the transition advances comprehensively, local governments should gradually shift from direct leadership to enabling role, with a focus on serving as conveners and catalysts. As the most credible and highly coordinated “super node” in the network, the government should identify and connect dispersed resources, information, and technological entities; bridge structural gaps; facilitate cross-level and cross-departmental collaboration; and maximize system-wide value and operational efficiency.

Key tasks include the following:

Promoting the construction of urban energy big-data platforms, establishing unified data standards and sharing mechanisms, attracting enterprises and other stakeholders to participate, and supporting intelligent decision-making and operations in the urban energy sector.

Establishing a regular “government–industry–academia–research–finance” platform, facilitating information exchange among heterogeneous actors through technology salons, project roadshows, and closed-door seminars, filling structural holes, and accelerating the circulation and matching of information, technology, talent, and capital.

Creating a special energy-transition fund guided by government capital and complemented by private investment, prioritizing support for comprehensive projects jointly proposed by multiple partners.

Actively engaging in international platforms such as the C40 Global Summit, SEforALL, and the Global Clean Energy Alliance to strengthen international cooperation and knowledge exchange. While introducing advanced concepts and technologies, it is also important to showcase Qingdao’s experience in promoting coordinated pollution and carbon reduction, thereby enhancing the city’s visibility and influence in global energy governance.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations, which also provide directions for future research to further deepen and extend the analysis.

First, the single-case design limits the generalizability of the findings. While the in-depth examination of Qingdao enables a detailed understanding of how local governments operate within real governance networks, the applicability of these conclusions to other types of cities remains constrained. Future studies could apply this analytical framework to comparative analyses across multiple Chinese cities to assess its broader relevance and identify context-specific variations.

Second, the reliance on publicly available official data may lead to an incomplete representation of governance interactions. Such sources may overlook informal cooperation or off-plan actor relationships that are often critical in shaping transition dynamics. Future research incorporating fieldwork, in-depth interviews, or longitudinal tracking of policy documents could more comprehensively uncover the behavioral logic and role-shaping mechanisms underlying the transition.

Third, the single-layer network approach limits the ability to capture the complexity of multilevel governance structures. Although this study examines some aspects of longitudinal role evolution at the municipal scale, it cannot fully reflect the richer roles local governments play across different governance levels, nor anticipate potential future role shifts. Future work could introduce multilayer network models or dynamic evolution approaches to better capture role changes across spatial and temporal dimensions.

Finally, as China’s urban energy transition becomes increasingly embedded within global climate governance, further research is needed to explore how Chinese local governments position themselves and interact within transnational urban networks. Such work would help expand the international dimension of local transition practices and provide insights into their emerging roles in global energy governance.