1. Introduction

Clearly, not all pieces of knowledge are equally valuable for teaching and learning, and the time and effort of both teachers and learners should be concentrated on the most important and valuable ones.

In education research, concepts such as Big Ideas [

1,

2] and threshold concepts [

3,

4] have been proposed to help teachers and textbook authors determine what to teach. However, most of these concepts are defined vaguely and primarily in terms of their perceived importance or effects in teaching and learning.

For example, Big Ideas are ideas and concepts that unify diverse knowledge into a coherent whole [

1,

2]. Threshold concepts are transformative concepts that fundamentally reshape a learner’s perspective, leading to an integrative and irreversible understanding of the subject, and making it easier to learn other concepts [

3,

4]. Similarly, The International Baccalaureate (IB) key concepts are organizing principles that connect diverse mathematical content and help students appreciate mathematics as a tool for inquiry and understanding the world [

5,

6].

However, the above definitions are functional rather than operational. Here, an operational definition refers to a definition grounded in specific measurements and procedures, such that by following these procedures, one can determine whether a given object belongs to a particular concept. In contrast, a functional definition defines a concept based on the roles or effects of a potential object that belongs to that concept.

Ideally, all definitions should be operational, and the functions of objects associated with a concept should be causally linked to its operational definition. Since Big Ideas, threshold concepts, and IB key concepts are defined functionally, it is very challenging for teachers to determine whether a specific concept, idea, or proposition qualifies as one of these important knowledge types [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Existing approaches to identifying important knowledge, such as expert interviews, surveys, and case analyses, fundamentally rely on expert judgment and experiential intuition, lacking systematic, reproducible criteria. This problem could ideally be addressed if there were an operational definition for each of these concepts.

In this work, we aim to show that concept networks and the corresponding network analysis can potentially provide an operational definition of these concepts, thereby enabling us to determine what to teach.

To achieve this, we constructed a concept network [

13,

14] of mathematics in primary and lower secondary education. We analyzed both Big Ideas from [

2] and IB key concepts [

5,

6], examining whether concept network analysis can deconstruct the characteristics of these important knowledge types and provide operational definitions.

Our primary contribution is demonstrating that concept network analysis can provide operational definitions for important knowledge. While specific network indicators (such as degree centrality) emerge from the analysis, the fundamental advancement lies in establishing the analytical framework itself—showing that important knowledge characteristics can be systematically deconstructed into quantifiable structural features.

This analytical framework offers a promising starting point for systematically addressing “what to teach,” complementing rather than replacing expert judgment. More broadly, this approach provides a promising methodology and perspective for knowledge-focused educational research, contributing to the development of more effective teaching and learning strategies.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Concept Network and Network Analysis in Education Studies

A concept network (also called concept map) is a structured knowledge representation form that emphasizes connections between knowledge elements. In a concept network, nodes represent concepts, and edges represent dependency or associative relationships between them [

13,

14,

15]. This representation not only presents direct connections between knowledge, but also reveals more complex indirect relationships, thus displaying a systematic, analyzable knowledge structure.

From an educational value perspective, a concept network is not only a visualization result of knowledge structure, but the construction process itself is also an effective tool for promoting teaching and learning [

14,

15,

16,

17]. A large number of empirical studies show that in teaching applications, concept networks help students clarify knowledge relationships and construct systematic understanding frameworks [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28].

At the same time, network analysis as a core method for revealing the laws of complex systems has both holistic and individual analytical perspectives. It can both understand the overall structure of the system through relationships between nodes, and describe the function and role of individuals within the system framework [

29,

30,

31]. Over the past ten years, the application of this method in educational research has continued to deepen, and it has been widely used to analyze problems such as peer influence, learner self-regulation, and knowledge construction [

32,

33,

34,

35]. Notably, epistemic network analysis has emerged as a valuable approach in science education and Artificial Intelligence (AI)-supported learning contexts [

36,

37,

38].

The attempt to analyze knowledge structure from a network perspective did not begin with this study. It is worth noting that the work of Yan et al. [

39] took Chinese character hierarchical relationships as the research object and revealed the important role of structured associations in improving language learning efficiency. This study provided an inspiring network analysis approach for language learning. However, the analysis object of that study was the Chinese character system, not the concepts and knowledge structures in disciplinary ontology.

Existing educational network research mostly centers on learning effects, focusing on cognitive changes in learners or the complexity of knowledge structures. For example, some studies evaluate cognitive development through changes in network indicators before and after learning [

40,

41], analyze learners’ memory and knowledge structure patterns through semantic and concept network approaches [

42,

43], or analysis the social networks of learners [

44,

45,

46]. Other scholars use global indicators to characterize the overall complexity of knowledge systems [

47,

48,

49,

50], or analyse the prerequisite relationships of courses [

51]. Although these studies reveal structural characteristics in the learning process, they focus on macro-level patterns and have not been applied to identify individual important concepts within disciplinary knowledge structures.

2.2. Threshold Concepts

Threshold concepts refer to transformative ideas within a discipline that fundamentally alter learners’ understanding and perception of the subject matter [

3,

4]. These concepts are characterized as troublesome, irreversible, and integrative: once mastered, they open new ways of thinking that cannot be unlearned and enable connections across previously disparate knowledge domains [

3,

4,

7,

8]. For instance, in mathematics, the concept of “limit” serves as a threshold concept in calculus: students must grasp that a limit describes the behavior of a function as it approaches a particular point, rather than its value at that point, which represents a conceptual shift from static to dynamic mathematical thinking.

While threshold concepts have proven valuable in curriculum design and pedagogical practice [

52,

53,

54], their application to primary and secondary mathematics education faces a practical limitation. We conducted a comprehensive review of the published literature to identify documented threshold concepts in primary and secondary mathematics; however, no complete inventory currently exists. The majority of threshold concept research has been concentrated in higher education contexts [

3,

4,

7,

8], with only scattered examples identified at earlier educational stages. Consequently, the absence of a comprehensive and systematic list of threshold concepts in primary and secondary mathematics prevents us from using them as a basis for analysis in this study.

2.3. IB Key Concepts

The International Baccalaureate (IB) program employs key concepts as organizing principles for primary and secondary mathematics curricula [

5,

6,

55,

56]. These key concepts serve as broad organizing principles that facilitate interdisciplinary connections and provide meaning to student inquiry. For example, the key concept of “numbers” encompasses the understanding that our number system functions as a language for describing quantities and their relationships, such as how place value determines digit meaning within a base system, and that numerical operations (addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division) are interconnected tools for problem-solving [

6]. Research has demonstrated that IB programs significantly improve student academic outcomes and university preparation [

57,

58].

The IB program emphasizes mathematics as a tool for inquiry and a language for understanding the world. Rather than viewing mathematics as merely a collection of facts and equations to be memorized, the IB approach aims to help students appreciate the power of mathematics in describing and analyzing the world [

6]. This pedagogical philosophy aligns with the functional emphasis of key concepts in organizing curriculum around meaningful understanding rather than procedural knowledge.

2.4. Big Ideas

Big Ideas refer to overarching principles or concepts that guide curriculum development and teaching practices [

1,

59]. These ideas are intended to provide a coherent framework that connects various elements of the curriculum and enhances students’ understanding [

1,

2].

Taking primary and secondary mathematics education as examples, consider the big idea of “Equivalence,” which is defined as “any number, measure, numerical expression, algebraic expression, or equation can be represented in infinitely many ways with the same value” [

2]. This idea enables students to flexibly transform equations and expressions when solving problems. Similarly, the big idea of “Variable” states that “mathematical situations and structures can be translated and represented abstractly using variables, expressions, and equations” [

2]. This allows students to generalize patterns and formulate algebraic relationships, bridging arithmetic reasoning to abstract mathematical modeling.

Many empirical studies have confirmed the effectiveness of Big Ideas in enhancing teaching practices and improving student outcomes across various academic fields, spanning nearly all educational levels and covering disciplines such as Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) education, physics, biology, linguistics, and history [

60,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69,

70,

71,

72].

However, identifying Big Ideas remains challenging for teachers and students [

9,

10,

11,

12], as the functions of Big Ideas, such as providing a coherent framework for connecting pieces of knowledge, are likely the result of their structural roles within the corresponding concept network.

2.5. Research Gap

Existing approaches to identifying important knowledge primarily rely on expert interviews, surveys, and case analyses [

61,

62,

66,

67,

68,

72]. These methods fundamentally depend on expert judgment and experiential intuition, lacking systematic, reproducible criteria [

7,

9]. Meanwhile, while concept network analysis has been applied to assess learning outcomes and cognitive structures [

40,

49,

73], it has not been systematically employed to identify important knowledge within disciplinary structures through node-level analysis.

This study addresses these gaps by proposing a novel idea: transforming functional definitions of important knowledge into operational definitions based on quantifiable network structural characteristics. This transformation shifts the identification of important knowledge from reliance on expert judgment to measurable, reproducible criteria. Furthermore, this approach offers a promising methodology and perspective for knowledge-focused educational research.

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Data

The concept network data used in this study comes from the Institute of Educational System Science at the School of Systems Science, Beijing Normal University. The data covers mathematics concepts and their dependency relationships at the primary and middle school stages. Part of the concept network has been published in Wu’s book

Primary-School Mathematics Done Right [

74].

The dataset includes two basic elements:

Nodes: Represent mathematical concepts, with each node corresponding to a clearly defined concept name.

Edges: Represent dependency relationships between concepts. A directed edge from concept A to concept B indicates “understanding concept B requires concept A as prerequisite knowledge.”

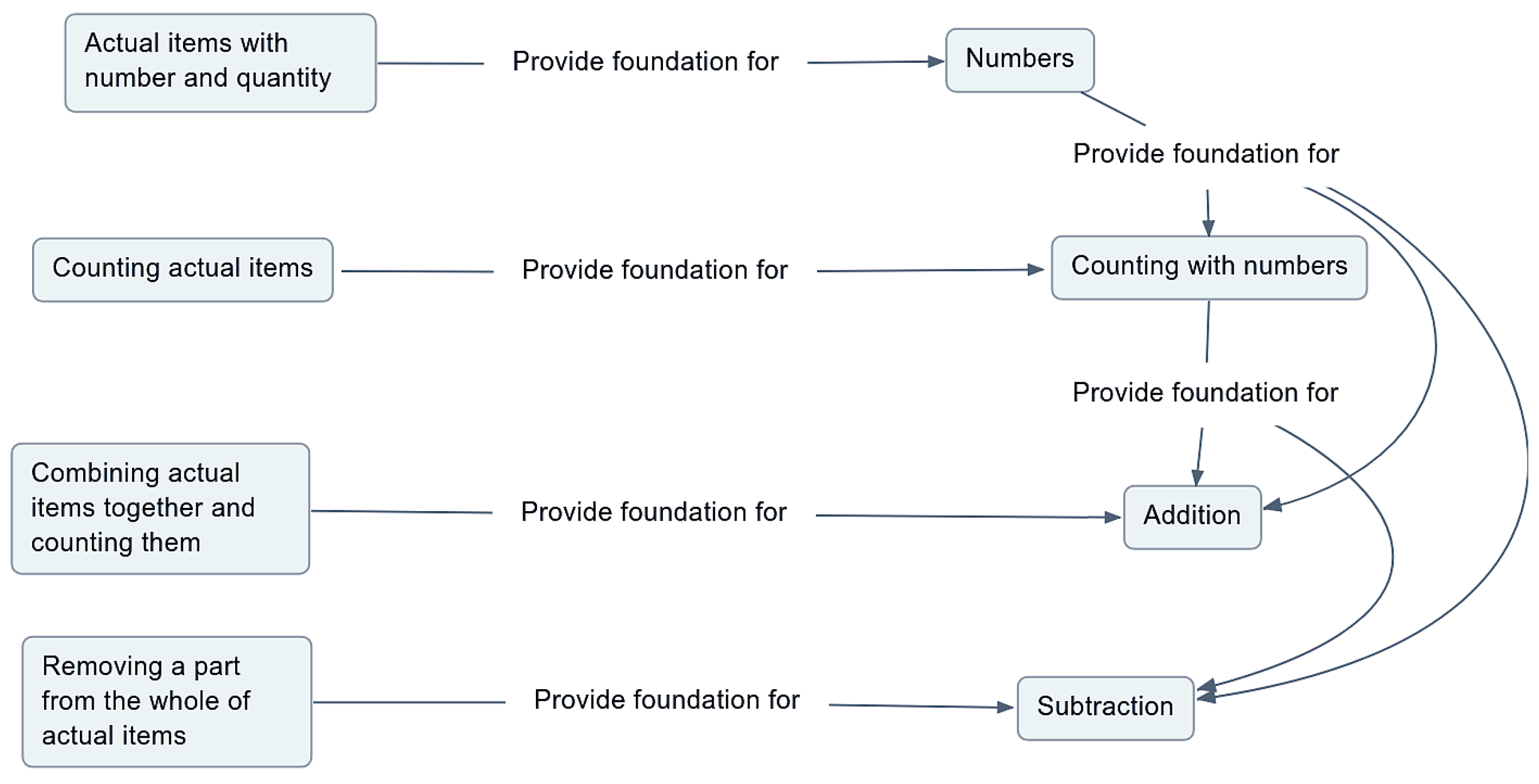

Figure 1 shows a basic structural diagram of the concept network. It displays nodes and their connection relationships to help readers understand how the concept network is constructed.

We conducted a thorough review of the literature on Big Ideas in primary and middle school mathematics education. Surprisingly, although a large number of studies focus on Big Ideas and their value in determining “what to teach” is widely recognized in research and practice [

60,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69,

70], mature cross-disciplinary Big Ideas lists are relatively rare [

2,

67,

75,

76,

77,

78,

79].

Therefore, this study selected the mathematics Big Ideas list published by [

2] as the main data source. This list is recommended by the Cambridge University Mathematics Department, is widely cited in teaching and learning research, and is regarded by academia as a highly credible resource. Subsequently, we aligned the Big Ideas in this list with the corresponding concepts in the existing concept network one by one. Without changing the original network structure, we annotated the Big Ideas in the network.

We also mapped 26 key concepts from the International Baccalaureate (IB) mathematics curriculum [

5,

6] to the concept network. As a comparable educational framework emphasizing foundational organizing principles, IB key concepts provide an independent case for examining whether important knowledge exhibits consistent structural patterns across different curriculum designs.

3.2. Methods

3.2.1. Basic Approach of Concept Network Analysis

The core question of this study is as follows. Can concept network analysis identify structural features that consistently characterize important knowledge across different educational frameworks (Big Ideas and IB key concepts)?

Our basic assumption is that concepts occupying key structural positions in the concept network are often important teaching content.

Specifically, if a concept is prerequisite knowledge for many other concepts, or if it plays a bridging role in connecting different knowledge modules, then this concept has high importance in the knowledge system. This structural importance can be characterized by indicators in network science.

3.2.2. Selection and Educational Interpretation of Network Indicators

We selected six widely used network indicators based on their potential educational significance in characterizing different aspects of how concepts function within knowledge systems. The detailed mathematical formulations for these indicators are provided in

Appendix B.

Out-degree (Equation (

A1)) [

29]: Measures how many subsequent concepts a concept directly supports. High out-degree concepts serve as foundational prerequisites enabling multiple advanced topics.

In-degree (Equation (

A2)) [

29]: Indicates how much prerequisite knowledge supports a concept. High in-degree concepts represent knowledge convergence points integrating multiple prior ideas.

Betweenness centrality (Equation (

A4)) [

80]: Reflects a concept’s role as a bridge connecting different knowledge domains. High betweenness concepts serve as critical intermediaries whose absence may disconnect knowledge modules.

Closeness centrality (Equation (

A5)) [

81]: Captures how efficiently a concept can reach other concepts in the network, indicating its centrality in the overall knowledge structure.

Clustering coefficient (Equation (

A6)) [

82]: Indicates whether a concept sits within a tightly interconnected knowledge module, suggesting its role as an organizing framework for coherent conceptual groups.

Reverse PageRank (Equation (

A7)) [

83]: While out-degree treats all outgoing connections equally, reverse PageRank weights them by the importance of supported concepts. This distinction is educationally meaningful: a concept supporting many advanced topics (high out-degree) may have different pedagogical significance than one supporting a few critical advanced concepts (high reverse PageRank). By including both, we can distinguish concepts that broadly enable subsequent learning from those that specifically enable important subsequent knowledge.

3.2.3. Composite Scoring Method

A single indicator can often only reflect certain aspects of concept characteristics. To systematically characterize the structural importance of concepts, we constructed a composite scoring function that comprehensively evaluates the importance of each concept node by weighting and summing the above network indicators:

where

l is the total number of network indicators used,

is the weight coefficient for each indicator, and

is the normalized value of the

i-th network indicator for node

u. The weights satisfy the normalization constraint

to ensure that each indicator contributes in proportional form. Concepts with the highest scores are considered potential Big Ideas.

Weight determination uses an optimization method to decode the structural features of Big Ideas. We analyze the structural positions of known Big Ideas and search for the optimal weight combination through optimization algorithms that best characterize their network signatures. We use four mature optimization algorithms (Differential Evolution (DE) [

84], Simulated Annealing (SA) [

85], Genetic Algorithm (GA) [

86], and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) [

87]) for independent search to verify the robustness of results.

The optimization objective includes two levels. First, maximize the coverage rate of important knowledge in the top-ranked nodes. Second, minimize the average ranking of important knowledge within the top range. This procedure is applied independently to both Big Ideas and IB key concepts to examine cross-framework consistency.

Technical details of the optimization algorithm are in

Appendix C.

4. Results

This section presents network analysis results for both Big Ideas and IB key concepts. We first analyze Big Ideas through node-level concept network analysis (

Section 4.1,

Section 4.2 and

Section 4.3), then present analysis of IB key concepts (

Section 4.4), demonstrating consistent structural patterns across educational frameworks.

4.1. Determination of Decoding Range

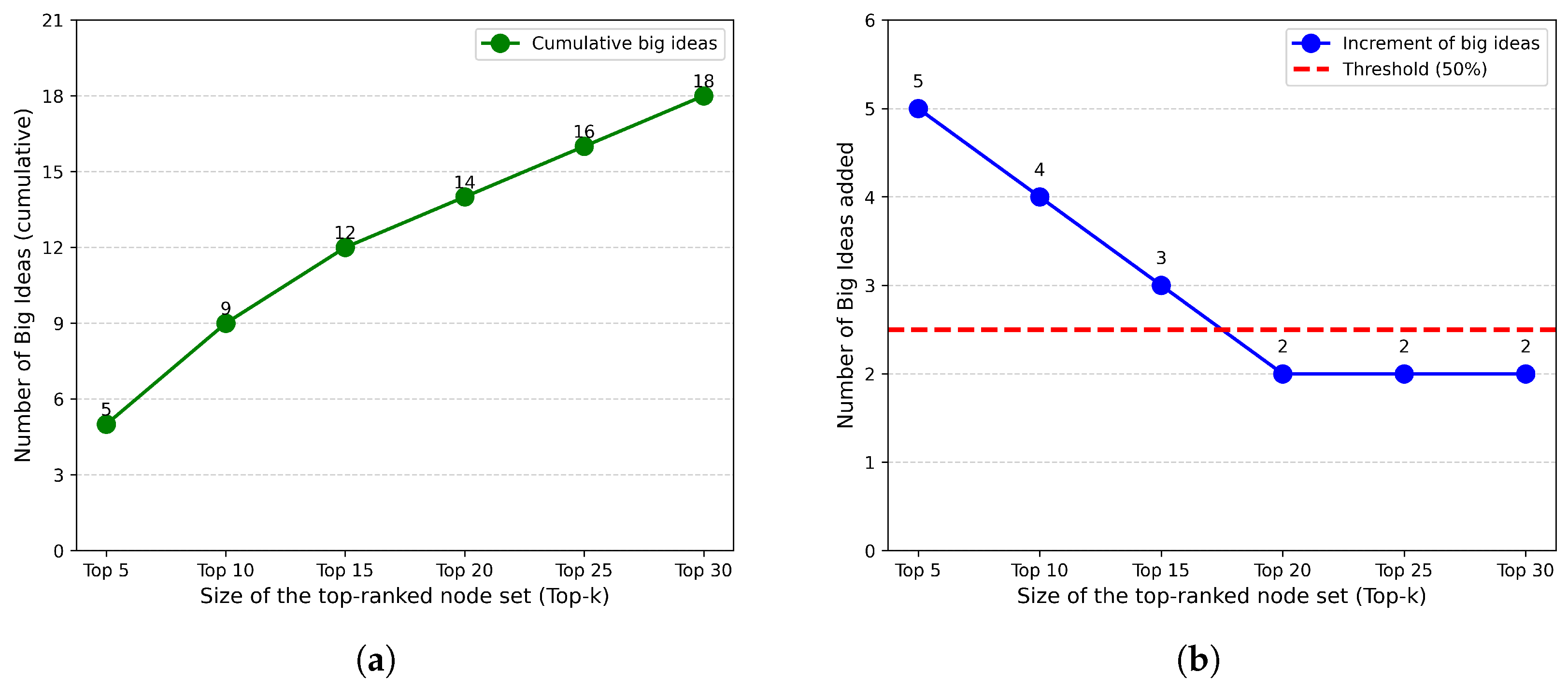

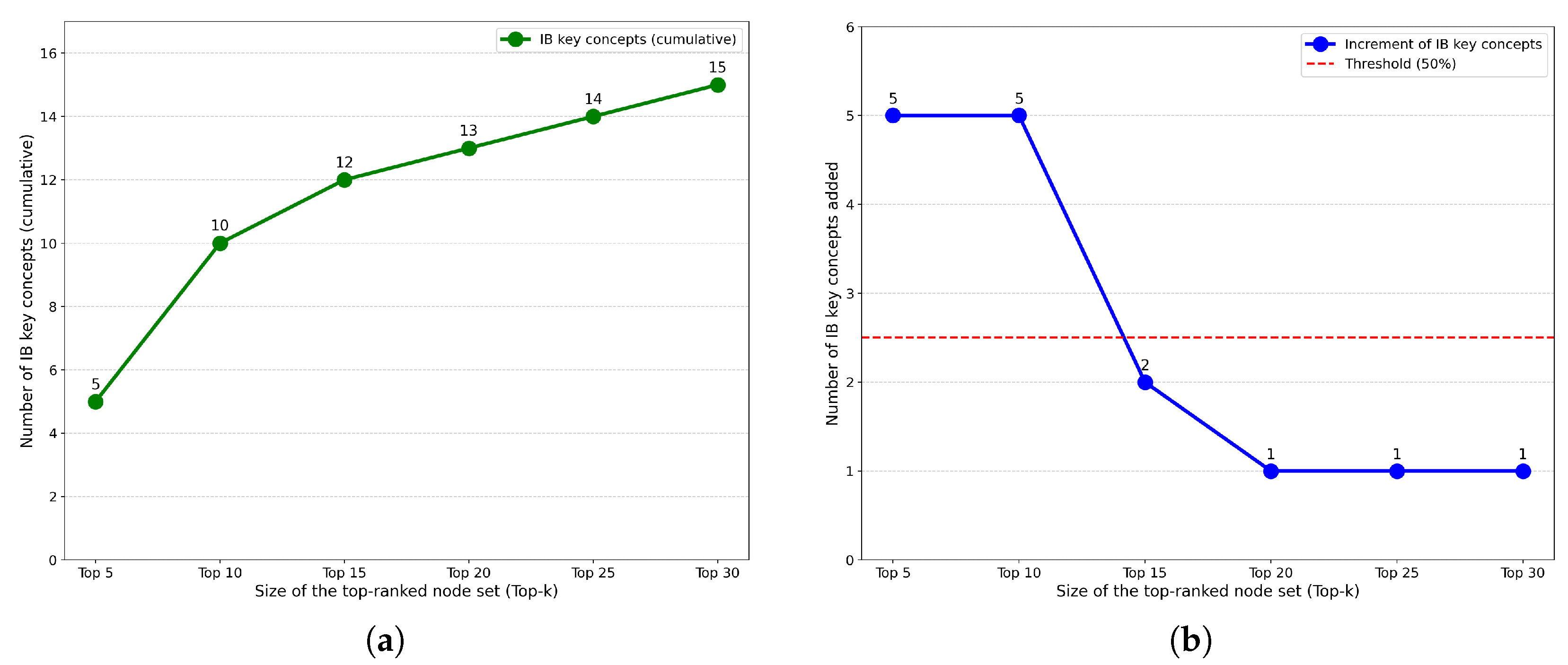

To extract structural features from Big Ideas, we must determine the optimal decoding range (Top-n) that maximizes their concentration while maintaining sufficient coverage. We examine Top-5 through Top-30 in increments of 5 nodes, applying a 50% concentration threshold: when fewer than half of newly added nodes are Big Ideas (i.e., <2.5 of 5 nodes), the range begins diluting the structural signal and we select the previous interval as the decoding range.

Figure 2 shows the distribution pattern. The cumulative count (a) exhibits diminishing returns as

n increases, while the incremental analysis (b) reveals that Top-15 is the concentration turning point: expansions to Top-10 and Top-15 add Big Ideas at 80% and 60% rates, respectively, but subsequent expansions drop to 40%, falling below the threshold.

We therefore set the decoding range as Top-15, which captures 12 Big Ideas (80% of Top-15 nodes) while maintaining high concentration purity. This 80% concentration substantially exceeds the baseline 9.8% (44/447) in the overall network, suggesting that Big Ideas occupy distinguishable structural positions. These patterns reflect fitting to the 44 Big Ideas from [

2].

4.2. Robustness of Structural Patterns

To verify the reliability of the discovered structural features, we employ four different optimization algorithms to independently explore the structural signature.

Table 1 summarizes the contribution weights of different structural features.

The scoring function remains fixed, with the optimization algorithms serving to explore which combinations of network indicators best characterize Big Ideas. We use DE, SA, GA, and PSO to ensure that the discovered structural patterns are not algorithm-dependent. To evaluate the consistency of structural features, we summarize statistics on the top 5% of results from each algorithm ranked by fitness.

Table 1 reveals the structural signature of Big Ideas. Out-degree consistently emerges as the dominant feature (mean weight: 0.50, range: 0.49–0.55, Coefficient of Variation (CV): 6.6%), accounting for approximately 50% of the structural characterization across all algorithms. This indicates that serving as prerequisite for multiple subsequent concepts is a fundamental structural feature. The clustering coefficient shows the highest stability (mean weight: 0.19, CV: 1.1%), indicating that positioning within structurally tight knowledge modules is a consistent characteristic.

In-degree (mean weight: 0.11) and betweenness centrality (mean weight: 0.12) show similar secondary contributions with moderate variation (CV: 26.4% and 24.2%). Betweenness centrality complements in-degree by capturing bridging positions between knowledge modules. Reverse PageRank and closeness centrality have lower contributions (means of 0.07 and near 0, respectively).

The consistency across optimization approaches suggests that the discovered structural patterns reflect stable fitting to Big Ideas rather than algorithmic artifacts. This algorithmic robustness supports the reliability of the operational definition, though it does not address whether these patterns predict importance in independent knowledge sets.

4.3. Distribution Patterns and Structural Characterization

To decode which structural features characterize important knowledge, we employ multi-indicator optimization using Big Ideas as reference cases. This approach explores the structural signature by determining which combinations of network indicators best capture the network positions of known important concepts.

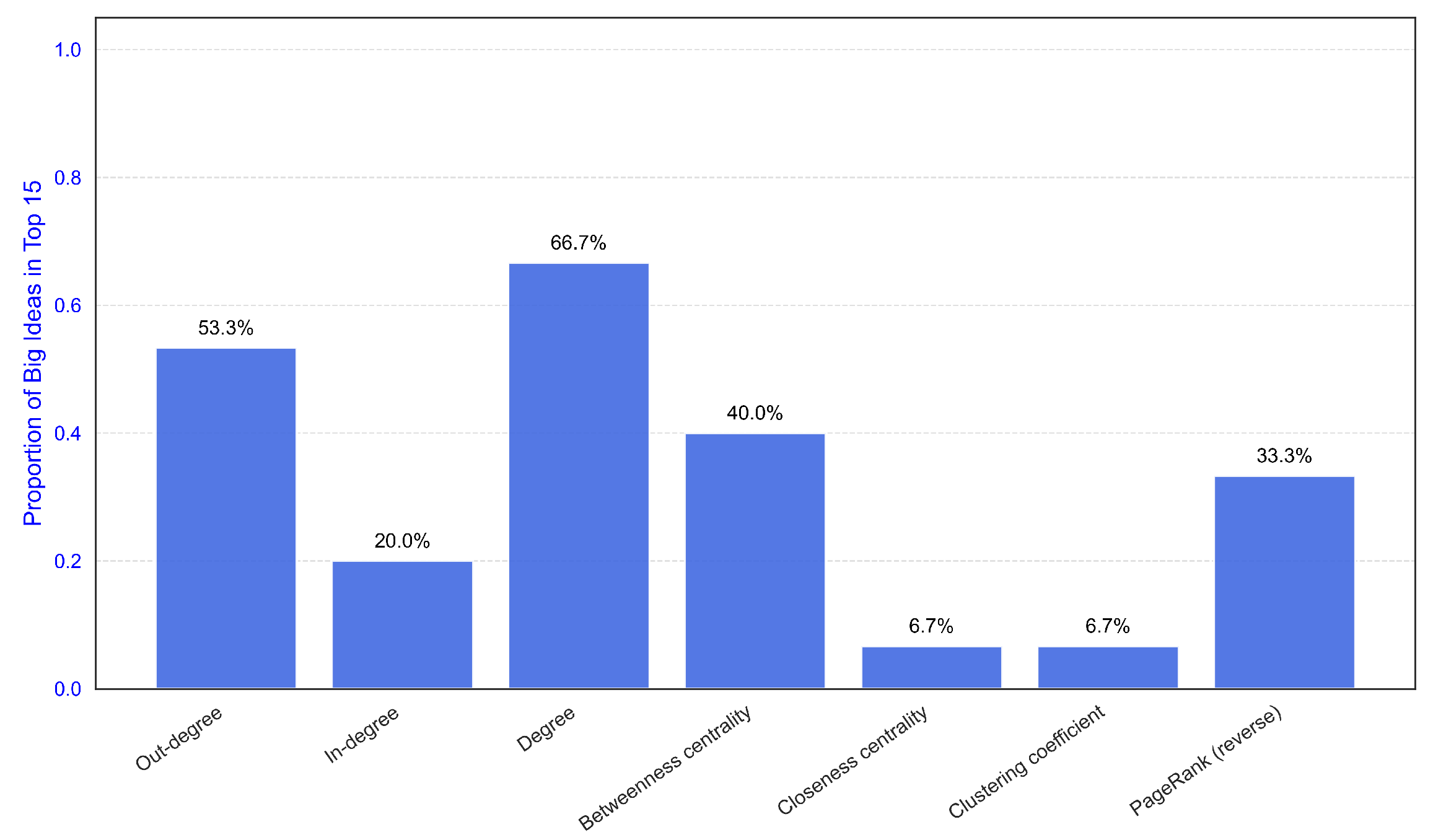

Examining different structural features reveals degree (Equation (

A3)) as the most distinctive single indicator. Among all network measures, degree shows the strongest association with Big Ideas, with 10 out of 15 nodes in Top-15 being Big Ideas (66.7%), suggesting that overall connectivity serves as a key structural signature of important knowledge. The multi-indicator composite approach further refines this characterization by incorporating clustering coefficient and other structural dimensions.

Figure 3 presents a comparative analysis of how different network indicators perform in identifying Big Ideas within Top-15 ranked nodes, demonstrating degree’s superior performance among single indicators.

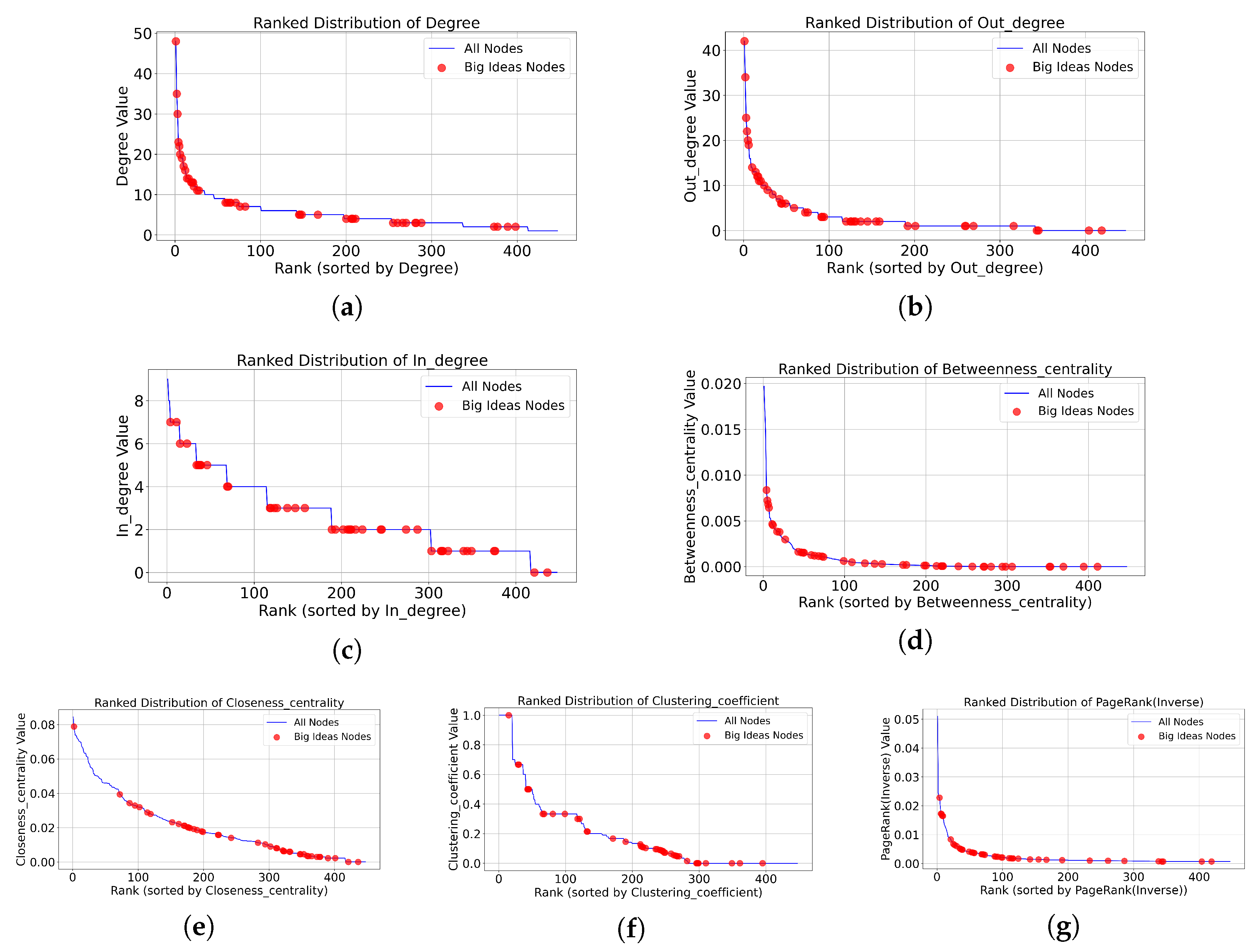

Figure 4 shows how Big Ideas distribute across different network indicators when all concepts are ranked by various structural measures.

Big Ideas exhibit high concentration in top-ranked positions under degree and out-degree rankings, and also show concentration in high clustering coefficient positions. In contrast, under rankings by in-degree, betweenness centrality, and closeness centrality, Big Ideas show less concentrated patterns. These distribution patterns, along with the statistical summaries in

Table 2, indicate that connectivity-based indicators, particularly overall degree and out-degree, most strongly characterize the structural properties of these independently defined important concepts.

The strong performance of degree as a single indicator merits examination of whether it reflects meaningful educational significance beyond network topology. Correlation analysis (

Table 3) reveals that out-degree and in-degree are statistically uncorrelated (

,

), capturing distinct dimensions: generative capacity (supporting subsequent learning) and integration demand (requiring prerequisite knowledge). As their sum, degree synthesizes both dimensions, quantifying how concepts establish interconnections that facilitate knowledge integration, a core pedagogical function. Critically, degree’s correlation with MeanRank (

) substantially exceeds that of out-degree (

) or in-degree (

) alone, demonstrating additional predictive value. This explains degree’s superior performance: it combines complementary, non-redundant structural information rather than being a topological artifact. Clustering coefficient’s high correlation with MeanRank (

) reflects structural consistency across all nodes rather than its discriminative power for Big Ideas.

4.4. Analysis of IB Key Concepts

We applied the same analytical framework to 26 IB key concepts mapped to the concept network. Following the same procedure, we determined the optimal Top-

n focus range as Top-10 based on the 50% concentration threshold criterion (

Figure 5).

The optimization consistently identified out-degree as the dominant feature (mean weight: 54%, CV: 2.4%), followed by in-degree (23%, CV: 5.0%) (

Table 4). The low coefficient of variation values indicate high stability of these features across different optimization algorithms. Together, out-degree and in-degree account for approximately 77% of the structural characterization, with their combination as degree effectively capturing IB key concepts’ pedagogical function of connecting disciplinary knowledge. This structural signature reflects how IB key concepts both support subsequent learning through prerequisite relationships (out-degree) and integrate foundational knowledge through convergence of multiple prior concepts (in-degree), enabling them to serve as organizing principles that bridge different areas of mathematical understanding. The subsequent analysis showing degree’s high identification rate as a single indicator further corroborates these findings.

The correlation matrix (

Table 5) demonstrates that degree centrality exhibits the highest correlation with the composite MeanRank score (

,

), outperforming all other individual indicators. Notably, the relationship between out-degree and in-degree shows weak negative correlation (

,

), indicating they capture complementary structural properties rather than redundant information. The fact that these two components measure distinct dimensions explains why their aggregation into degree provides enhanced predictive power: the correlation between degree and MeanRank (

) markedly surpasses the correlations of either out-degree (

) or in-degree (

) independently.

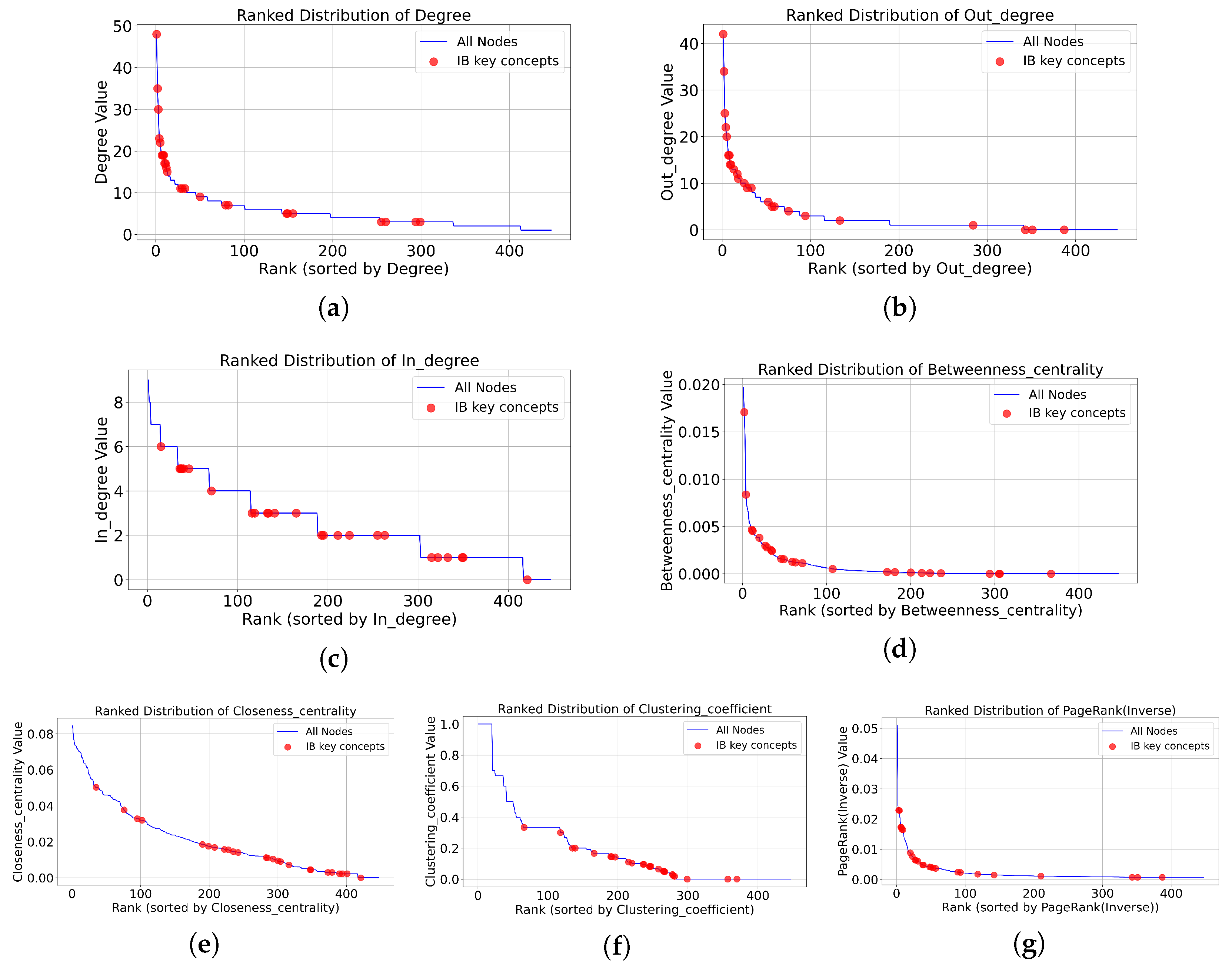

Figure 6 visualizes the positional distribution of IB key concepts when the full concept network is ordered by each structural indicator.

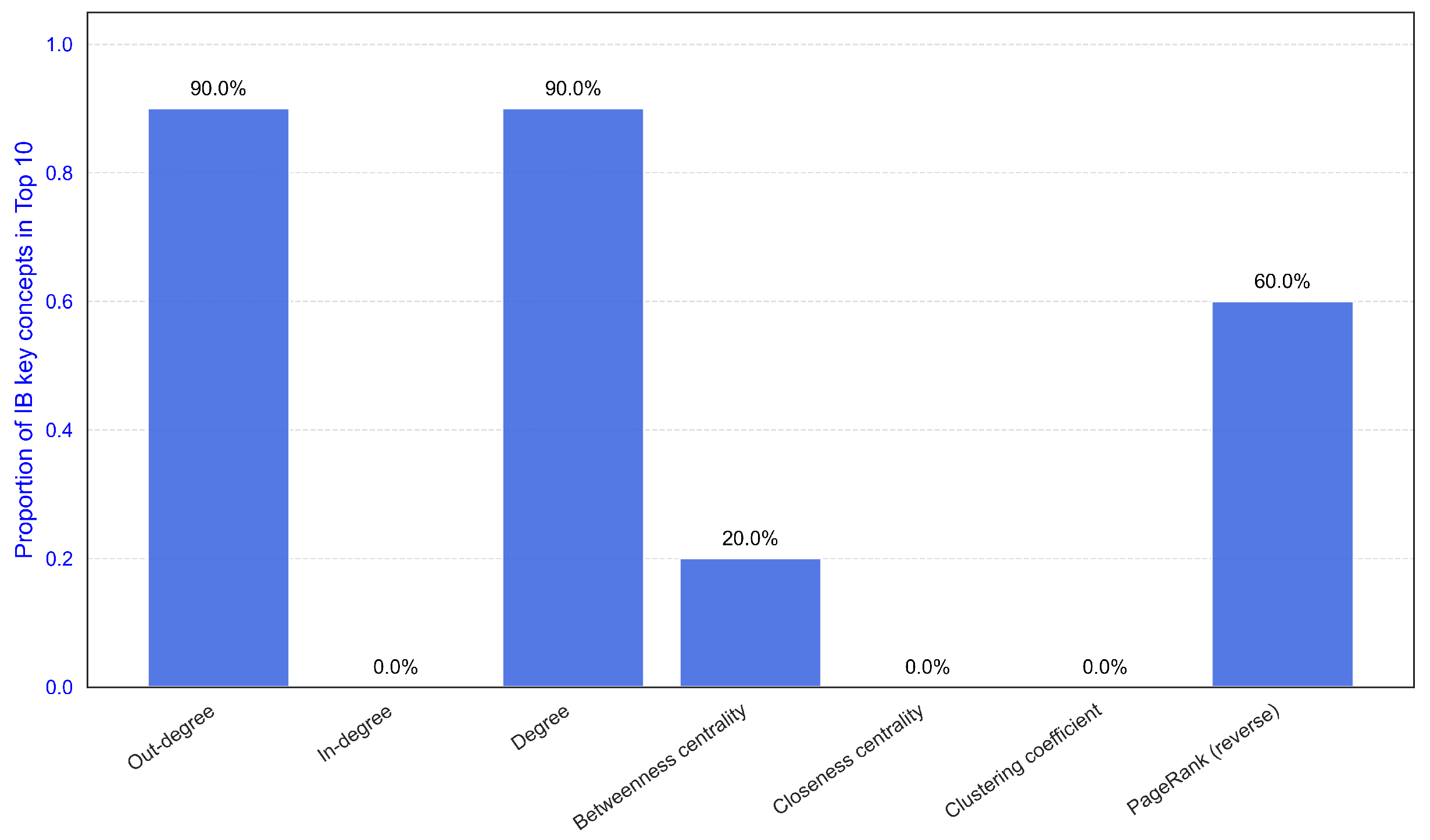

To validate the effectiveness of single indicators, we examined each metric’s ability to identify IB key concepts independently. Degree and out-degree emerged as equally effective, each identifying nine IB key concepts within the Top-10 ranked nodes (

Figure 7). Other indicators showed comparatively lower identification rates: reverse PageRank identified six concepts, while betweenness centrality identified only two concepts.

The analysis of IB key concepts further demonstrates that concept network analysis holds significant potential in achieving operational definitions for different types of important knowledge.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This paper’s primary contribution is demonstrating that concept network analysis can provide operational definitions for important knowledge through systematic deconstruction of their characteristics into quantifiable structural features. Through parallel analysis of 44 Big Ideas and 26 IB key concepts, the analytical framework successfully deconstructs important knowledge characteristics, with the process demonstrating stability across four independent optimization algorithms. While specific indicators emerge from the analysis—degree centrality proves particularly effective, identifying 10 of 15 Big Ideas in Top-15 ranked nodes and 9 of 26 IB key concepts in Top-10 nodes—the fundamental advancement lies in establishing the framework itself. This demonstrates that important knowledge characteristics can be systematically transformed into measurable structural criteria, offering a methodological foundation for addressing the curriculum question of what to teach.

The structural analysis reveals correspondence between network features and educational functions of important knowledge. When optimized against Big Ideas, out-degree emerges as the dominant feature with high weight and remarkable stability, reflecting important knowledge’s capacity to support subsequent learning by serving as prerequisites for multiple advanced concepts. Clustering coefficient emerges as the second most important feature with exceptional consistency, indicating that important knowledge tends to be positioned at the center of tightly connected knowledge modules, enabling it to serve organizing functions in curriculum design. When optimized against IB key concepts, out-degree and in-degree emerge as the primary structural features, with their combination as degree capturing IB key concepts’ pedagogical function of connecting disciplinary knowledge by both supporting subsequent learning and integrating prerequisite concepts into coherent frameworks. Notably, the lower weight of clustering coefficient for IB key concepts suggests they may transcend individual knowledge modules to serve more general connective functions across the knowledge network. Algorithm-independence verification across four optimization methods and correlation analysis among network indicators demonstrate that the revealed features represent structural properties capturing distinct dimensions rather than methodological artifacts.

We acknowledge several limitations that also point to promising future research directions. (1) The current analysis uses learning dependency as the only relationship type, which may overlook other important structural dimensions. Future work should incorporate diverse relationship types (e.g., semantic similarity, conceptual analogy, and application contexts) to construct multi-layer concept networks. (2) The scoring function and weight configuration are optimized specifically on mathematics concept networks. Future research should extend this approach across multiple disciplines (e.g., physics, biology, language learning, and history) to investigate whether optimal indicator combinations and weights vary by discipline or whether universal patterns exist. (3) Systematic and comprehensive collections of important knowledge remain scarce in educational research, constraining available reference cases for this study. Our analysis examined two sets of educationally important concepts: 44 Big Ideas and 26 IB key concepts. Big Ideas and IB key concepts share theoretical similarities as both identify organizing principles for curriculum design, which limits the independence of these two analyses. While both analyses independently converged on similar structural patterns, the sample sizes remain limited for establishing broad predictive validity. Future research should examine structurally diverse frameworks and extend to different disciplines to establish broader generalizability. (4) This study is a theoretical computational investigation and does not include empirical validation in educational settings. Future research should design empirical studies to validate whether concepts identified through network analysis indeed improve learning outcomes compared to traditional curriculum sequencing. (5) We did not conduct systematic sensitivity analysis to examine how results change under network perturbations (e.g., modifying 10% of connections or Big Ideas mappings). Future work should implement comprehensive sensitivity testing to quantify the robustness of identified structural patterns and determine minimal data quality requirements. (6) We did not compare our network-based approach with alternative computational methods such as latent knowledge models or NLP-based curriculum mapping. Future research should conduct systematic benchmarking studies comparing multiple approaches, potentially revealing complementary strengths and enabling hybrid methods. (7) Despite multi-expert consensus processes, complete elimination of subjective judgment in network construction and annotation remains challenging. Future work should explore automated and semi-automated approaches, leveraging NLP-based knowledge extraction and relation extraction from educational texts, to improve objectivity, consistency, and reproducibility while enabling large-scale network construction across diverse educational domains.

Nevertheless, despite these limitations, this study establishes that concept network analysis can systematically provide operational definitions for important knowledge. By demonstrating that important knowledge characteristics can be deconstructed into quantifiable structural features, this research offers a methodological framework and new perspectives for knowledge-focused educational research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.W.; methodology, J.W. and X.C.; software, X.C.; validation, X.C.; formal analysis, X.C.; investigation, X.C.; data curation, X.C.; writing—original draft preparation, X.C.; writing—review and editing, J.W.; visualization, X.C.; supervision, J.W.; project administration, J.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. This study did not involve humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. This study did not involve humans.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the conclusions of this article are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request due to intellectual property restrictions on the original concept network data. Processed analysis data and code are available upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge all individuals who have contributed directly or indirectly to this research. We thank all reviewers and colleagues who provided valuable feedback and suggestions during the development of this research. We also acknowledge the support from all experts who provided valuable feedback and suggestions during the development of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| DAG | Directed Acyclic Graph |

| DE | Differential Evolution |

| GA | Genetic Algorithm |

| PSO | Particle Swarm Optimization |

| SA | Simulated Annealing |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| STEM | Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics |

| IB | International Baccalaureate |

| MYP | Middle Years Programme |

| PYP | Primary Years Programme |

| Q1 | First Quartile |

| Q3 | Third Quartile |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| CV | Coefficient of Variation |

Appendix A. Construction of Concept Network

The concept network used in this study was manually constructed to represent the dependency structure of mathematical knowledge. Each node in the network corresponds to a mathematical concept, idea, or proposition. Each directed edge represents a dependency relationship. Specifically, if there is an edge from node A to node B, it indicates that “understanding concept A is a prerequisite for learning concept B.”

The network construction was conducted by researchers from the Institute of Educational System Science at Beijing Normal University, including the authors. These researchers have sustained engagement with mathematics education through long-term, multi-round training programs and pedagogical discussions with teachers across China. This continued collaboration with practitioners provided the team with deep understanding of both mathematical content structure and pedagogical considerations in curriculum design.

All concepts in the concept network come from textbooks and mathematics books written by domain experts. A total of 447 concepts, ideas, or propositions were selected as network nodes. For each concept drawn from multiple mathematics textbooks, the team collaboratively identified its structural prerequisites and subsequent concepts through iterative expert discussions. The connections between these nodes are established based on structural relationships inherent in concept definitions. For example, the definition of a right triangle is “A triangle with one right angle is called a right triangle.” Therefore, “right angle” and “triangle” are structurally required as prerequisite knowledge for “right triangle.” Similarly, the definition of a right angle is “A right angle equals half of a straight angle,” so “straight angle” is prerequisite knowledge for “right angle.” Through this method, we constructed the entire concept network. The final network contains 447 nodes and 1139 directed edges, forming a directed acyclic graph (DAG) based on learning dependency hierarchy structure.

To ensure the network’s reliability, all construction and annotation processes involved multi-expert discussions in research meetings and teacher training sessions. Rather than relying on individual judgment, the collaborative process was designed to achieve consensus on prerequisite relationships through iterative deliberation, reducing idiosyncratic interpretations.

The annotation of Big Ideas and IB key concepts followed a similar consensus-based process. Experts mapped each important concept to the most conceptually aligned node(s) in the network through group deliberation, based on the definitions and examples provided in the original literature [

2,

5]. The annotation procedures for both sets follow the same basic principles. Here, we use Big Ideas as an example to illustrate the process. We aligned the concepts, ideas, and propositions in Big Ideas lists [

2] one by one with the corresponding nodes in the concept network. For each Big Idea, the team reviewed its definition and examples from the source literature, then collaboratively identified the most conceptually aligned node(s) in the existing concept network. For example, the Big Idea of “Equivalence” is defined as “Any number, measure, numerical expression, algebraic expression, or equation can be represented in infinitely many ways with the same value” [

2]. Through group deliberation, we determined it is highly matched with “Properties of Equation” in the concept network, because “Properties of Equation” precisely concerns the transformation of equations (including numerical and algebraic expressions), and these transformations are carried out while maintaining equal values on both sides of the equation. Although this alignment may not be completely precise, the multi-expert consensus process ensured the highest degree of conceptual matching through systematic deliberation rather than individual judgment. Following the same principle and consensus-based approach, we manually annotated 44 Big Ideas and 26 IB key concepts [

5] nodes in the network.

Through the above method, we annotated the concepts in the concept network most likely to correspond to Big Ideas and IB key concepts without changing the original network structure.

Appendix B. Mathematical Definitions of Network Indicators

This section provides rigorous mathematical definitions of the network indicators used in the study.

Appendix B.1. Out-Degree

where

E is the edge set of the graph, and

represents an edge from node

v pointing to node

u.

Appendix B.4. Betweenness Centrality

where

is the number of shortest paths from node

s to node

t, and

is the number of those shortest paths passing through node

v.

Appendix B.5. Closeness Centrality

where

is the shortest path distance between node

u and node

v.

Appendix B.6. Clustering Coefficient

where

is the number of triangles formed between neighbors of node

v, and

is the degree of node

v.

Appendix B.7. Reverse PageRank

where

d is the damping factor (set to 0.85),

N is the total number of nodes in the graph,

is the set of nodes pointed to by node

v, and

is the in-degree of node

u.

Appendix C. Technical Details of Optimization Algorithms

To ensure effective structural feature extraction from Big Ideas, we used four effective optimization algorithms to independently search for optimal weights . We selected these algorithms because they are all mature global optimization algorithms that can effectively find optimal solutions in complex search spaces, avoiding local optima and enhancing the reliability and robustness of results:

Differential Evolution (DE): A population-based heuristic algorithm that effectively explores the search space through differential mutation and crossover operations [

84].

Simulated Annealing (SA): A probabilistic optimization technique derived from the metallurgical annealing process that can escape local optima by “occasionally accepting worse solutions” [

85].

Genetic Algorithm (GA): A biomimetic evolutionary method that evolves solutions over multiple generations through selection, crossover, and mutation mechanisms [

86].

Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO): An algorithm inspired by swarm intelligence that optimizes candidate solutions based on information sharing among individuals and collective behavior [

87].

The optimization process is as follows:

Step 1: Define fitness function

To evaluate each weight configuration, we define a fitness function to ensure that Big Ideas can be ranked in top positions. The optimization algorithm prioritizes two main objectives when ranking concepts and knowledge units:

Coverage rate: The primary objective is to maximize the proportion of Big Ideas in top nodes, ensuring that the highest-ranked nodes are mainly composed of these key knowledge elements.

Average ranking: The secondary objective is to minimize the average ranking of Big Ideas within top nodes, thereby further distinguishing them from other knowledge elements. Here, we focus on improving the ranking performance of Big Ideas within the “top range,” without considering their ranking outside this range. This approach ensures that attention is focused on the most prominent concepts and their structural characteristics.

Step 2: Initialize weights

Each weight is initialized in the interval to ensure it is non-negative and bounded. This provides a stable starting point for the optimization algorithm and avoids unreasonable or unbounded weights.

Step 3: Perform iterative optimization

Each algorithm iteratively adjusts weights to maximize the fitness function. Optimization stops when termination conditions are met (such as convergence to a stable solution or reaching a preset maximum number of iterations).

Step 4: Record results

For each run, record the best-performing weight set and the corresponding fitness score as the basis for subsequent analysis.

Step 5: Multiple independent runs

Considering the randomness of optimization algorithms, repeat steps 2 to 4 for multiple independent runs (for example, in this study, each algorithm was run 4000 times, totaling 16,000 runs). Each run starts from different initialized weights to explore different regions of the search space.

Step 6: Final weight selection and application

Select the optimal weight set based on fitness scores from all optimization runs, and use it in the scoring function to calculate the algorithm score of each node and determine its relative ranking in the concept network.

Appendix D. Detailed Statistics for Algorithm Robustness Validation

Appendix D.1. Algorithm Robustness Validation for Big Ideas

This subsection presents detailed weight statistics for each network indicator under different optimization algorithms when analyzing Big Ideas.

Table A1.

Detailed statistics for out-degree weights (Big Ideas).

Table A1.

Detailed statistics for out-degree weights (Big Ideas).

| Algorithm | Optimal | Mean | 95% CI | SD | Q1 | Q3 |

|---|

| Differential Evolution | 0.5353 | 0.4871 | [0.4851, 0.4890] | 0.0139 | 0.4835 | 0.4857 |

| Particle Swarm Optim. | 0.5774 | 0.5294 | [0.5243, 0.5344] | 0.0363 | 0.4888 | 0.5636 |

| Genetic Algorithm | 0.5342 | 0.5464 | [0.5450, 0.5478] | 0.0102 | 0.5387 | 0.5516 |

| Simulated Annealing | 0.5725 | 0.4972 | [0.4937, 0.5007] | 0.0249 | 0.4855 | 0.4902 |

Table A2.

Detailed statistics for in-degree weights (Big Ideas).

Table A2.

Detailed statistics for in-degree weights (Big Ideas).

| Algorithm | Optimal | Mean | 95% CI | SD | Q1 | Q3 |

|---|

| Differential Evolution | 0.1652 | 0.0973 | [0.0951, 0.0995] | 0.0157 | 0.0921 | 0.0954 |

| Particle Swarm Optim. | 0.1374 | 0.1346 | [0.1297, 0.1394] | 0.0348 | 0.0970 | 0.1686 |

| Genetic Algorithm | 0.1650 | 0.1646 | [0.1638, 0.1655] | 0.0059 | 0.1651 | 0.1671 |

| Simulated Annealing | 0.1362 | 0.1000 | [0.0967, 0.1033] | 0.0238 | 0.0892 | 0.0941 |

Table A3.

Detailed statistics for betweenness centrality weights (Big Ideas).

Table A3.

Detailed statistics for betweenness centrality weights (Big Ideas).

| Algorithm | Optimal | Mean | 95% CI | SD | Q1 | Q3 |

|---|

| Differential Evolution | 0.0636 | 0.1297 | [0.1276, 0.1318] | 0.0150 | 0.1320 | 0.1341 |

| Particle Swarm Optim. | 0.0764 | 0.0955 | [0.0906, 0.1005] | 0.0355 | 0.0622 | 0.1346 |

| Genetic Algorithm | 0.0637 | 0.0640 | [0.0636, 0.0644] | 0.0029 | 0.0627 | 0.0637 |

| Simulated Annealing | 0.0755 | 0.1249 | [0.1217, 0.1282] | 0.0234 | 0.1326 | 0.1349 |

Table A4.

Detailed statistics for closeness centrality weights (Big Ideas).

Table A4.

Detailed statistics for closeness centrality weights (Big Ideas).

| Algorithm | Optimal | Mean | 95% CI | SD | Q1 | Q3 |

|---|

| Differential Evolution | 0.0001 | 0.0042 | [0.0037, 0.0047] | 0.0036 | 0.0014 | 0.0069 |

| Particle Swarm Optim. | 0.0057 | 0.0005 | [0.0003, 0.0006] | 0.0014 | 0.0000 | 0.0001 |

| Genetic Algorithm | 0.0000 | 0.0004 | [0.0001, 0.0006] | 0.0016 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| Simulated Annealing | 0.0073 | 0.0040 | [0.0036, 0.0044] | 0.0030 | 0.0015 | 0.0061 |

Table A5.

Detailed statistics for clustering coefficient weights (Big Ideas).

Table A5.

Detailed statistics for clustering coefficient weights (Big Ideas).

| Algorithm | Optimal | Mean | 95% CI | SD | Q1 | Q3 |

|---|

| Differential Evolution | 0.1937 | 0.1938 | [0.1936, 0.1939] | 0.0012 | 0.1936 | 0.1943 |

| Particle Swarm Optim. | 0.2004 | 0.1970 | [0.1965, 0.1975] | 0.0034 | 0.1947 | 0.1992 |

| Genetic Algorithm | 0.1938 | 0.1956 | [0.1953, 0.1958] | 0.0019 | 0.1944 | 0.1966 |

| Simulated Annealing | 0.2003 | 0.1948 | [0.1946, 0.1951] | 0.0018 | 0.1940 | 0.1954 |

Table A6.

Detailed statistics for reverse PageRank weights (Big Ideas).

Table A6.

Detailed statistics for reverse PageRank weights (Big Ideas).

| Algorithm | Optimal | Mean | 95% CI | SD | Q1 | Q3 |

|---|

| Differential Evolution | 0.0422 | 0.0880 | [0.0861, 0.0899] | 0.0136 | 0.0898 | 0.0925 |

| Particle Swarm Optim. | 0.0026 | 0.0431 | [0.0380, 0.0481] | 0.0362 | 0.0080 | 0.0836 |

| Genetic Algorithm | 0.0433 | 0.0290 | [0.0274, 0.0306] | 0.0115 | 0.0220 | 0.0385 |

| Simulated Annealing | 0.0081 | 0.0791 | [0.0755, 0.0826] | 0.0254 | 0.0854 | 0.0915 |

Appendix D.2. Algorithm Robustness Validation for IB Key Concepts

This subsection presents detailed weight statistics for each network indicator under different optimization algorithms when analyzing IB key concepts.

Table A7.

Detailed statistics for out-degree weights (IB key concepts).

Table A7.

Detailed statistics for out-degree weights (IB key concepts).

| Algorithm | Optimal | Mean | 95% CI | SD | Q1 | Q3 |

|---|

| Simulated Annealing | 0.5906 | 0.5314 | [0.5251, 0.5376] | 0.0452 | 0.4961 | 0.5617 |

| Differential Evolution | 0.5246 | 0.5291 | [0.5243, 0.5339] | 0.0344 | 0.5068 | 0.5500 |

| Particle Swarm Optim. | 0.5036 | 0.5623 | [0.5545, 0.5701] | 0.0560 | 0.5229 | 0.6007 |

| Genetic Algorithm | 0.4932 | 0.5441 | [0.5371, 0.5512] | 0.0510 | 0.5021 | 0.5759 |

Table A8.

Detailed statistics for in-degree weights (IB key concepts).

Table A8.

Detailed statistics for in-degree weights (IB key concepts).

| Algorithm | Optimal | Mean | 95% CI | SD | Q1 | Q3 |

|---|

| Simulated Annealing | 0.2314 | 0.2247 | [0.2214, 0.2279] | 0.0233 | 0.2071 | 0.2414 |

| Differential Evolution | 0.2243 | 0.2255 | [0.2229, 0.2282] | 0.0188 | 0.2131 | 0.2383 |

| Particle Swarm Optim. | 0.2177 | 0.2537 | [0.2495, 0.2580] | 0.0306 | 0.2302 | 0.2785 |

| Genetic Algorithm | 0.2021 | 0.2343 | [0.2305, 0.2381] | 0.0274 | 0.2133 | 0.2520 |

Table A9.

Detailed statistics for betweenness centrality weights (IB key concepts).

Table A9.

Detailed statistics for betweenness centrality weights (IB key concepts).

| Algorithm | Optimal | Mean | 95% CI | SD | Q1 | Q3 |

|---|

| Simulated Annealing | 0.0736 | 0.0542 | [0.0510, 0.0574] | 0.0229 | 0.0372 | 0.0718 |

| Differential Evolution | 0.0722 | 0.0595 | [0.0565, 0.0625] | 0.0217 | 0.0462 | 0.0753 |

| Particle Swarm Optim. | 0.0257 | 0.0341 | [0.0297, 0.0385] | 0.0317 | 0.0000 | 0.0614 |

| Genetic Algorithm | 0.0499 | 0.0549 | [0.0510, 0.0587] | 0.0276 | 0.0386 | 0.0757 |

Table A10.

Detailed statistics for closeness centrality weights (IB Key Concepts).

Table A10.

Detailed statistics for closeness centrality weights (IB Key Concepts).

| Algorithm | Optimal | Mean | 95% CI | SD | Q1 | Q3 |

|---|

| Simulated Annealing | 0.0341 | 0.0163 | [0.0144, 0.0182] | 0.0139 | 0.0046 | 0.0236 |

| Differential Evolution | 0.0228 | 0.0140 | [0.0126, 0.0155] | 0.0105 | 0.0055 | 0.0204 |

| Particle Swarm Optim. | 0.0000 | 0.0037 | [0.0024, 0.0050] | 0.0094 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| Genetic Algorithm | 0.0200 | 0.0096 | [0.0079, 0.0112] | 0.0120 | 0.0000 | 0.0178 |

Table A11.

Detailed statistics for clustering coefficient weights (IB key concepts).

Table A11.

Detailed statistics for clustering coefficient weights (IB key concepts).

| Algorithm | Optimal | Mean | 95% CI | SD | Q1 | Q3 |

|---|

| Simulated Annealing | 0.0096 | 0.0753 | [0.0678, 0.0828] | 0.0540 | 0.0301 | 0.1139 |

| Differential Evolution | 0.0215 | 0.0710 | [0.0652, 0.0768] | 0.0419 | 0.0373 | 0.1011 |

| Particle Swarm Optim. | 0.1667 | 0.0575 | [0.0498, 0.0651] | 0.0553 | 0.0000 | 0.1036 |

| Genetic Algorithm | 0.1034 | 0.0709 | [0.0633, 0.0784] | 0.0543 | 0.0194 | 0.1167 |

Table A12.

Detailed statistics for reverse PageRank weights (IB key concepts).

Table A12.

Detailed statistics for reverse PageRank weights (IB key concepts).

| Algorithm | Optimal | Mean | 95% CI | SD | Q1 | Q3 |

|---|

| Simulated Annealing | 0.0608 | 0.0981 | [0.0915, 0.1048] | 0.0478 | 0.0553 | 0.1372 |

| Differential Evolution | 0.1346 | 0.1008 | [0.0952, 0.1065] | 0.0408 | 0.0717 | 0.1343 |

| Particle Swarm Optim. | 0.0863 | 0.0887 | [0.0811, 0.0963] | 0.0549 | 0.0410 | 0.1372 |

| Genetic Algorithm | 0.1314 | 0.0863 | [0.0785, 0.0940] | 0.0559 | 0.0299 | 0.1337 |

References

- Wiggins, G.P.; McTighe, J. Understanding by Design, 2nd ed.; Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Charles, R.I.; Carmel, C. Big Ideas and Understandings as the Foundation for Elementary and Middle School Mathematics. J. Math. Educ. 2005, 7, 9–24. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J.; Land, R. Threshold Concepts and Troublesome Knowledge: Linkages to Ways of Thinking and Practising within the Disciplines; Oxford Brookes University: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J.H.F.; Land, R. Threshold Concepts and Troublesome Knowledge (2): Epistemological Considerations and a Conceptual Framework for Teaching and Learning. High. Educ. 2005, 49, 373–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Baccalaureate Organization. Middle Years Programme Mathematics Guide (for Use from September 2020/January 2021); International Baccalaureate Organization (UK) Ltd.: Cardiff, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- International Baccalaureate Organization. Primary Years Programme: Mathematics Scope and Sequence; International Baccalaureate Organization: Cardiff, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rowbottom, D.P. Demystifying Threshold Concepts. J. Philos. Educ. 2007, 41, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbeer, J. Threshold Concepts within the Disciplines: A Report on a Symposium at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, 30 August to 1 September 2006. Planet 2006, 17, 16–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, K.J.; Lewin, J. Big Ideas in the Geography Curriculum: Nature, Awareness and Need. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 2023, 47, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadenfeldt, J.C.; Neumann, K.; Bernholt, S.; Liu, X.; Parchmann, I. Students’ Progression in Understanding the Matter Concept: Students’ Progression in Understanding Matter. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2016, 53, 683–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, S.L.; Smith, C.A.; Gillam, E.M.A.; Wright, T. The Concept Lens Diagram: A New Mechanism for Presenting Biochemistry Content in Terms of “Big Ideas”. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Educ. 2011, 39, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Yuan, R.; Wang, K. Unlocking the Power of Big Ideas in Education: A Systematic Review from 2010 to 2022. Res. Pap. Educ. 2024, 39, 822–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, J.D.; Gowin, D.B. Learning How to Learn; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Novak, J.D. Concept Mapping: A Useful Tool for Science Education. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 1990, 27, 937–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. Teach Less, Learn More; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Novak, J.D.; Cañas, A.J. The Theory Underlying Concept Maps and How to Construct and Use Them; Technical Report IHMC CmapTools 2006-01 Rev 01-2008; Florida Institute for Human and Machine Cognition: Pensacola, FL, USA, 2008; Available online: http://cmap.ihmc.us/Publications/ResearchPapers/TheoryUnderlyingConceptMaps.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Ausubel, D.P.; Novak, J.D.; Hanesian, H.; Ausubel, D.F. Educational Psychology: A Cognitive View, 2nd ed.; Holt, Rinehart & Winston: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Pendley, B.D.; Bretz, R.L.; Novak, J.D. Concept Maps as a Tool to Assess Learning in Chemistry. J. Chem. Educ. 1994, 71, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, J.; Dekkers, J. The Concept Map as an Aid to Instruction in Science and Mathematics. Sch. Sci. Math. 1984, 84, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, J.D. Meaningful Learning: The Essential Factor for Conceptual Change in Limited or Inappropriate Propositional Hierarchies Leading to Empowerment of Learners. Sci. Educ. 2002, 86, 548–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, C.I.; Bal, T.M.P.; Brinchmann, M.F.; Noble, L.R.; Raeymaekers, J.A.M.; Bjornevik, M. The Concept Map as a Substitute for Lectures: Effects on Student Performance and Mental Health. Cogent Educ. 2023, 10, 2218154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, Y.M.; Lee, B.D. Concept Map-Based Learning in an Oral Radiographic Interpretation Course: Dental Students’ Perceptions of Its Role as a Learning Tool. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2023, 27, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khajeloo, M.; Siegel, M.A. Concept Map as a Tool to Assess and Enhance Students’ System Thinking Skills. Instr. Sci. 2022, 50, 571–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, G.; Long, T. Is the Text-Based Cognitive Tool More Effective than the Concept Map on Improving the Pre-Service Teachers’ Argumentation Skills? Think. Ski. Creat. 2021, 41, 100862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.C.; Pu, H.C.; Su, S.J.; Lee, M.S. A Concept Map-Based Remedial Learning System with Applications to the IEEE Floating-Point Standard and MIPS Encoding. IEEE Trans. Educ. 2021, 64, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetya, D.D.; Hirashima, T.; Hayashi, Y. Study on Extended Scratch-Build Concept Map to Enhance Students’ Understanding and Promote Quality of Knowledge Structure. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2020, 11, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, J.; Mintzes, J. The Concept Map as a Research Tool—Exploring Conceptual Change in Biology. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 1990, 27, 1033–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, R.M.; Alpizar, D.; Adesope, O.O.; Nishida, K.R.A. Role of Concept Map Format and Student Interest on Introductory Electrochemistry Learning. Sch. Sci. Math. 2024, 124, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strogatz, S.H. Exploring Complex Networks. Nature 2001, 410, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, R.; Barabási, A.L. Statistical Mechanics of Complex Networks. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2002, 74, 47–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Di, Z. Complex Networks in Statistical Physics. Prog. Phys. 2004, 24, 18–46. [Google Scholar]

- DeLay, D.; Zhang, L.; Hanish, L.D.; Miller, C.F.; Fabes, R.A.; Martin, C.L.; Kochel, K.P.; Updegraff, K.A. Peer Influence on Academic Performance: A Social Network Analysis of Social-Emotional Intervention Effects. Prev. Sci. 2016, 17, 903–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroga, E.; Garcia, I.; Alberto Benitez-Andrades, J.; Benavides, C.; Martin, V.; Marques-Sanchez, P. A Qualitative Study of Secondary School Teachers’ Perception of Social Network Analysis Metrics in the Context of Alcohol Consumption among Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shea, P.; Hayes, S.; Smith, S.U.; Vickers, J.; Bidjerano, T.; Gozza-Cohen, M.; Jian, S.B.; Pickett, A.M.; Wilde, J.; Tseng, C.H. Online Learner Self-Regulation: Learning Presence Viewed through Quantitative Content- and Social Network Analysis. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2013, 14, 427–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, D.W.; Hatfield, D.; Svarovsky, G.N.; Nash, P.; Nulty, A.; Bagley, E.; Frank, K.; Rupp, A.A.; Mislevy, R. Epistemic Network Analysis: A Prototype for 21st-Century Assessment of Learning. Int. J. Learn. Media 2009, 1, 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, J.W.; Parrish, J.; Syed, S.B.; Couch, B. Finding the Connections: A Scoping Review of Epistemic Network Analysis in Science Education. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2025, 34, 937–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Q.; Pang, H.; Tan, S.C.; Lei, J.; Wallace, M.P.; Li, L. What Matters in AI-supported Learning: A Study of Human-AI Interactions in Language Learning Using Cluster Analysis and Epistemic Network Analysis. Comput. Educ. 2023, 194, 104703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Han, Z.; Li, M.; Wang, X.; Zhao, W. Sentiment Evolution with Interaction Levels in Blended Learning Environments: Using Learning Analytics and Epistemic Network Analysis. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2021, 37, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Fan, Y.; Di, Z.; Havlin, S.; Wu, J. Efficient Learning Strategy of Chinese Characters Based on Network Approach. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e69745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, J.; Plummer, R.; Haug, C.; Huitema, D. Learning Effects of Interactive Decision-Making Processes for Climate Change Adaptation. Glob. Environ.-Chang.-Hum. Policy Dimens. 2014, 27, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siew, C.S.Q. Applications of Network Science to Education Research: Quantifying Knowledge and the Development of Expertise through Network Analysis. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchini, S.A.; Wang, S.; Kenett, Y.N.; Beaty, R.E. Mapping the Memory Structure of High-Knowledge Students: A Longitudinal Semantic Network Analysis. J. Intell. 2024, 12, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Fang, J.; Cheng, H.N.H.; Men, Q.; Li, Y. Investigating Online Learners’ Knowledge Structure Patterns by Concept Maps: A Clustering Analysis Approach. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 11401–11422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Du, J. What Participation Types of Learners Are There in Connectivist Learning: An Analysis of a cMOOC from the Dual Perspectives of Social Network and Concept Network Characteristics. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2023, 31, 5424–5441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Qi, C.; Huang, R.; Zuo, H.; He, J. Mathematics Teachers’ Interaction Patterns and Role Changes in Online Research-Practice Partnerships: A Social Network Analysis. Comput. Educ. 2024, 218, 105077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.; Ellis, R.A. Patterns of Student Collaborative Learning in Blended Course Designs Based on Their Learning Orientations: A Student Approaches to Learning Perspective. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2021, 18, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sher, N.; Kent, C.; Rafaeli, S. How ’networked’ Are Online Collaborative Concept-Maps? Introducing Metrics for Quantifying and Comparing the ’Networkedness’ of Collaboratively Constructed Content. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapuza, A. How Concept Maps with and without a List of Concepts Differ: The Case of Statistics. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siew, C.S.Q. Using Network Science to Analyze Concept Maps of Psychology Undergraduates. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 2019, 33, 662–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Gharebhaygloo, M.; Rondi, H.R.; Hortis, E.; Lostalo, E.Z.; Huang, X.; Ercal, G. Comparative Analysis of Course Prerequisite Networks for Five Midwestern Public Institutions. Appl. Netw. Sci. 2024, 9, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavrinides, P.; Zuev, K.M. Course-Prerequisite Networks for Analyzing and Understanding Academic Curricula. Appl. Netw. Sci. 2023, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, E.; Schmutz, A.M.S.; Volschenk, M.; Jacobs, C. How the Mapping of Threshold Concepts across a Master’s Programme in Health Professions Education Could Support the Development of Mastersness. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillmanns, T.; Salomão Filho, A.; Rudra, S.; Weber, P.; Dawitz, J.; Wiersma, E.; Dudenaite, D.; Reynolds, S. Mapping Tomorrow’s Teaching and Learning Spaces: A Systematic Review on GenAI in Higher Education. Trends High. Educ. 2025, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaniyi, N.E.E. Threshold Concepts: Designing a Format for the Flipped Classroom as an Active Learning Technique for Crossing the Threshold. Res. Pract. Technol. Enhanc. Learn. 2020, 15, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrissey, A.M.; Rouse, E.; Doig, B.; Chao, E.; Moss, J. Early Years Education in the Primary Years Programme (PYP): Implementation Strategies and Programme Outcomes; Final Report; Deakin University: Melbourne, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, S.A. Critical Analysis of the International Baccalaureate Primary Years Programme Curriculum Development: Mapping the Journey of International Baccalaureate Education. Cogent Educ. 2024, 11, 2429363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saavedra, A.R. The Academic Impact of Enrollment in International Baccalaureate Diploma Programs: A Case Study of Chicago Public Schools. Teach. Coll. Rec. Voice Scholarsh. Educ. 2014, 116, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, A.; Perry, L.B.; Ledger, S. Impacts of International Baccalaureate Programmes on Teaching and Learning: A Review of the Literature. J. Res. Int. Educ. 2018, 17, 240–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, C.; Francome, T.; Hewitt, D.; Shore, C. Principles for the Design of a Fully-Resourced, Coherent, Research-Informed School Mathematics Curriculum. J. Curric. Stud. 2021, 53, 621–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, A.; Chevrette, M.G.; Acharya, D.D.; Lozano, G.L.; Garavito, M.; Heinritz, J.; Balderrama, L.; Beebe, M.; DenHartog, M.L.; Corinaldi, K.; et al. Tiny Earth: A Big Idea for STEM Education and Antibiotic Discovery. mBio 2021, 12, e03432-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shemwell, J.T.; Avargil, S.; Capps, D.K. Grappling with Long-term Learning in Science: A Qualitative Study of Teachers’ Views of Developmentally Oriented Instruction. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2015, 52, 1163–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, J.D.; Krajcik, J. Building a Learning Progression for Celestial Motion: Elementary Levels from an Earth-Based Perspective. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2010, 47, 768–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, R.G.; Rogat, A.D.; Yarden, A. A Learning Progression for Deepening Students’ Understandings of Modern Genetics across the 5th–10th Grades. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2009, 46, 655–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesnutt, K.; Gail Jones, M.; Corin, E.N.; Hite, R.; Childers, G.; Perez, M.P.; Cayton, E.; Ennes, M. Crosscutting Concepts and Achievement: Is a Sense of Size and Scale Related to Achievement in Science and Mathematics? J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2019, 56, 302–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shemwell, J.T.; Capps, D.K.; Fackler, A.K.; Coogler, C.H. Integrative Analysis Using Big Ideas: Energy Transfer and Cellular Respiration. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2023, 32, 510–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peppler, K.; Wohlwend, K.; Thompson, N.; Tan, V.; Thomas, A. Squishing Circuits: Circuitry Learning with Electronics and Playdough in Early Childhood. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2019, 28, 118–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche Allred, Z.D.; Santiago Caobi, L.; Pardinas, B.; Echarri-Gonzalez, A.; Kohn, K.P.; Kararo, A.T.; Cooper, M.M.; Underwood, S.M. “Big Ideas” of Introductory Chemistry and Biology Courses and the Connections between Them. CBE—Life Sci. Educ. 2022, 21, ar35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deehan, J.; MacDonald, A. “What’s the Big Idea?”: A Qualitative Analysis of the Big Ideas of Primary Science Teachers. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2023, 119, 102189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, R.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Q. Unleashing the Potential of Big Ideas in Language Education: What and How? TESOL Q. 2024, 58, 1801–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimpour, S.; Fitzgerald, M.; Hollow, R. Examining the Mismatch between the Intended Astronomy Curriculum Content, Astronomical Literacy, and the Astronomical Universe. Phys. Rev. Phys. Educ. Res. 2024, 20, 010135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanton, M.; Stephens, A.; Knuth, E.; Gardiner, A.M.; Isler, I.; Kim, J.S. The Development of Children’s Algebraic Thinking: The Impact of a Comprehensive Early Algebra Intervention in Third Grade. J. Res. Math. Educ. 2015, 46, 39–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidowitz, B.; Rollnick, M. What Lies at the Heart of Good Undergraduate Teaching? A Case Study in Organic Chemistry. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2011, 12, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clariana, R.B.; Engelmann, T.; Yu, W. Using Centrality of Concept Maps as a Measure of Problem Space States in Computer-Supported Collaborative Problem Solving. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2013, 61, 423–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. Primary-School Mathematics Done Right; Zhejiang People’s Publishing House: Hangzhou, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Askew, M. Big Ideas in Primary Mathematics: Issues and Directions. Perspect. Educ. 2013, 31, 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Nurnberger-Haag, J.; Courtney, S.; Plaster, K. Big Ideas of Mathematics: A Construct in Need of a Teacher-, Student-, and Family-Friendly Framework. Electron. J. Res. Sci. Math. Educ. 2024, 28, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, B. Big Ideas in Physics and How to Teach Them: Teaching Physics 11–18; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harlen, W.; Bell, D. Principles and Big Ideas of Science Education; Association for Science Education: Hatfield, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tout, D.; Spithill, J.; Trevitt, J.; Knight, P.; Meiers, M. Big Ideas in Mathematics Teaching; The Research Digest, QCT, 2015, 11; Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER): Camberwell, Australia, 2015; Available online: https://research.acer.edu.au/digest/11/ (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Freeman, L.C. A Set of Measures of Centrality Based on Betweenness. Sociometry 1977, 40, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavelas, A. Communication Patterns in Task-Oriented Groups. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1950, 22, 725–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, D.J.; Strogatz, S.H. Collective Dynamics of ‘Small-World’ Networks. Nature 1998, 393, 440–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, L.; Brin, S.; Motwani, R.; Winograd, T. The PageRank Citation Ranking: Bringing Order to the Web; Technical Report; Stanford Infolab: Stanford, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Storn, R.; Price, K. Differential Evolution—A Simple and Efficient Heuristic for Global Optimization over Continuous Spaces. J. Glob. Optim. 1997, 11, 341–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, S.; Gelatt Jr, C.D.; Vecchi, M.P. Optimization by Simulated Annealing. Science 1983, 220, 671–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland, J.H. Adaptation in Natural and Artificial Systems: An Introductory Analysis with Applications to Biology, Control, and Artificial Intelligence; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, J.; Eberhart, R. Particle Swarm Optimization. In Proceedings of the ICNN’95-International Conference on Neural Networks, Perth, WA, Australia, 27 November–1 December 1995; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1995; Volume 4, pp. 1942–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Diagram of nodes and connections in the concept network. Boxes represent individual knowledge units and concepts in the network, and directed arrows represent prerequisite relationships between them.

Figure 1.

Diagram of nodes and connections in the concept network. Boxes represent individual knowledge units and concepts in the network, and directed arrows represent prerequisite relationships between them.

Figure 2.

Distribution pattern of Big Ideas under different ranking ranges. (a) Cumulative count of Big Ideas showing the trend as Top-n increases; (b) incremental number of newly added Big Ideas in each interval, with the red dashed line indicating the 50% threshold. The horizontal axis (Top-n) represents the number of highest-scoring nodes selected, ranging from Top-5 to Top-30 in increments of 5; different values of n indicate the set composed of the top n ranked nodes.

Figure 2.

Distribution pattern of Big Ideas under different ranking ranges. (a) Cumulative count of Big Ideas showing the trend as Top-n increases; (b) incremental number of newly added Big Ideas in each interval, with the red dashed line indicating the 50% threshold. The horizontal axis (Top-n) represents the number of highest-scoring nodes selected, ranging from Top-5 to Top-30 in increments of 5; different values of n indicate the set composed of the top n ranked nodes.

Figure 3.

Concentration of Big Ideas within Top-15 ranked nodes under different network indicators. Degree shows the highest concentration (10/15, 66.7%) among single indicators.

Figure 3.

Concentration of Big Ideas within Top-15 ranked nodes under different network indicators. Degree shows the highest concentration (10/15, 66.7%) among single indicators.

Figure 4.

Distribution of Big Ideas across different network indicators. Subfigures (a–g) show Big Ideas’ positions when all concepts are ranked by: degree, out-degree, in-degree, betweenness centrality, closeness centrality, clustering coefficient, and PageRank (reverse). Red markers indicate Big Ideas’ positions in each ranking. The horizontal axis shows node ranking in descending order by the corresponding indicator (left = high ranking), and the vertical axis shows the indicator value.

Figure 4.

Distribution of Big Ideas across different network indicators. Subfigures (a–g) show Big Ideas’ positions when all concepts are ranked by: degree, out-degree, in-degree, betweenness centrality, closeness centrality, clustering coefficient, and PageRank (reverse). Red markers indicate Big Ideas’ positions in each ranking. The horizontal axis shows node ranking in descending order by the corresponding indicator (left = high ranking), and the vertical axis shows the indicator value.

Figure 5.

Distribution pattern of IB key concepts under different ranking ranges. (a) Cumulative count of IB key concepts showing the trend as Top-n increases; (b) incremental number of newly added IB key concepts in each interval, with the red dashed line indicating the 50% threshold. The horizontal axis (Top-n) represents the number of highest-scoring nodes selected, ranging from Top-5 to Top-30 in increments of 5; different values of n indicate the set composed of the top n ranked nodes.

Figure 5.

Distribution pattern of IB key concepts under different ranking ranges. (a) Cumulative count of IB key concepts showing the trend as Top-n increases; (b) incremental number of newly added IB key concepts in each interval, with the red dashed line indicating the 50% threshold. The horizontal axis (Top-n) represents the number of highest-scoring nodes selected, ranging from Top-5 to Top-30 in increments of 5; different values of n indicate the set composed of the top n ranked nodes.

Figure 6.

Distribution of IB key concepts across different network indicators. Subfigures (a–g) show IB key concepts’ positions when all concepts are ranked by: degree, out-degree, in-degree, betweenness centrality, closeness centrality, clustering coefficient, and PageRank (reverse). Red markers indicate IB key concepts’ positions in each ranking. The horizontal axis shows node ranking in descending order by the corresponding indicator (left = high ranking), and the vertical axis shows the indicator value.

Figure 6.

Distribution of IB key concepts across different network indicators. Subfigures (a–g) show IB key concepts’ positions when all concepts are ranked by: degree, out-degree, in-degree, betweenness centrality, closeness centrality, clustering coefficient, and PageRank (reverse). Red markers indicate IB key concepts’ positions in each ranking. The horizontal axis shows node ranking in descending order by the corresponding indicator (left = high ranking), and the vertical axis shows the indicator value.

Figure 7.

Performance of single network indicators in identifying IB key concepts within Top-10 nodes. Degree and out-degree show equally strong performance (9/10 each), while other indicators demonstrate lower effectiveness. This pattern parallels the Big Ideas results.

Figure 7.

Performance of single network indicators in identifying IB key concepts within Top-10 nodes. Degree and out-degree show equally strong performance (9/10 each), while other indicators demonstrate lower effectiveness. This pattern parallels the Big Ideas results.

Table 1.

Summary of weight statistics under different optimization algorithms (based on top 5% results from 4000 independent runs of each of four algorithms).

Table 1.

Summary of weight statistics under different optimization algorithms (based on top 5% results from 4000 independent runs of each of four algorithms).

| Indicator | Weight Range | Mean Weight | SD | CV |

|---|

| Out-degree | 0.49–0.55 | 0.50 | 0.033 | 6.6% |

| In-degree | 0.10–0.16 | 0.11 | 0.029 | 26.4% |

| Betweenness centrality | 0.06–0.13 | 0.12 | 0.029 | 24.2% |

| Clustering coefficient | 0.19–0.20 | 0.19 | 0.002 | 1.1% |

| Reverse PageRank | 0.03–0.09 | 0.07 | 0.033 | 47.1% |

| Closeness centrality | 0.00–0.01 | 0.00 | 0.003 | — |

Table 2.

Statistical summary of top 5% weights for Big Ideas (focusing on Top-15).

Table 2.

Statistical summary of top 5% weights for Big Ideas (focusing on Top-15).

| Indicator | Optimal | Mean | 95% CI | SD | Q1 | Q3 |

|---|

| Out-degree | 0.5340 | 0.5032 | [0.5019, 0.5046] | 0.0331 | 0.4826 | 0.5346 |

| In-degree | 0.1649 | 0.1120 | [0.1108, 0.1132] | 0.0292 | 0.0954 | 0.1320 |

| Betweenness centrality | 0.0637 | 0.1168 | [0.1156, 0.1180] | 0.0294 | 0.0815 | 0.1339 |

| Closeness centrality | 0.0000 | 0.0012 | [0.0011, 0.0013] | 0.0024 | 0.0000 | 0.0013 |

| Clustering coefficient | 0.1937 | 0.1946 | [0.1945, 0.1947] | 0.0024 | 0.1937 | 0.1948 |