Considering Consumer Quality Preferences, Who Should Offer Trade-in Between Manufacturer and Retail Platform?

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Motivation

- (i)

- What is the optimal decision-making and profitability of the manufacturer and the retail platform when they dominate trade-in, respectively?

- (ii)

- What are the implications of different quality sensitivities and market shares of consumers on the profitability of manufacturer and retail platform?

- (iii)

- What is the optimal trade-in model? What is the impact of considering consumer segmentation based on quality preferences on the choice of model?

1.2. Contribution Statement and Article Structure

2. Literature Review

2.1. Trade-in Pricing Decisions

2.2. Trade-in Model Selection

2.3. Trade-in Consumer Segmentation

3. Model Description and Assumption

4. Model Solution

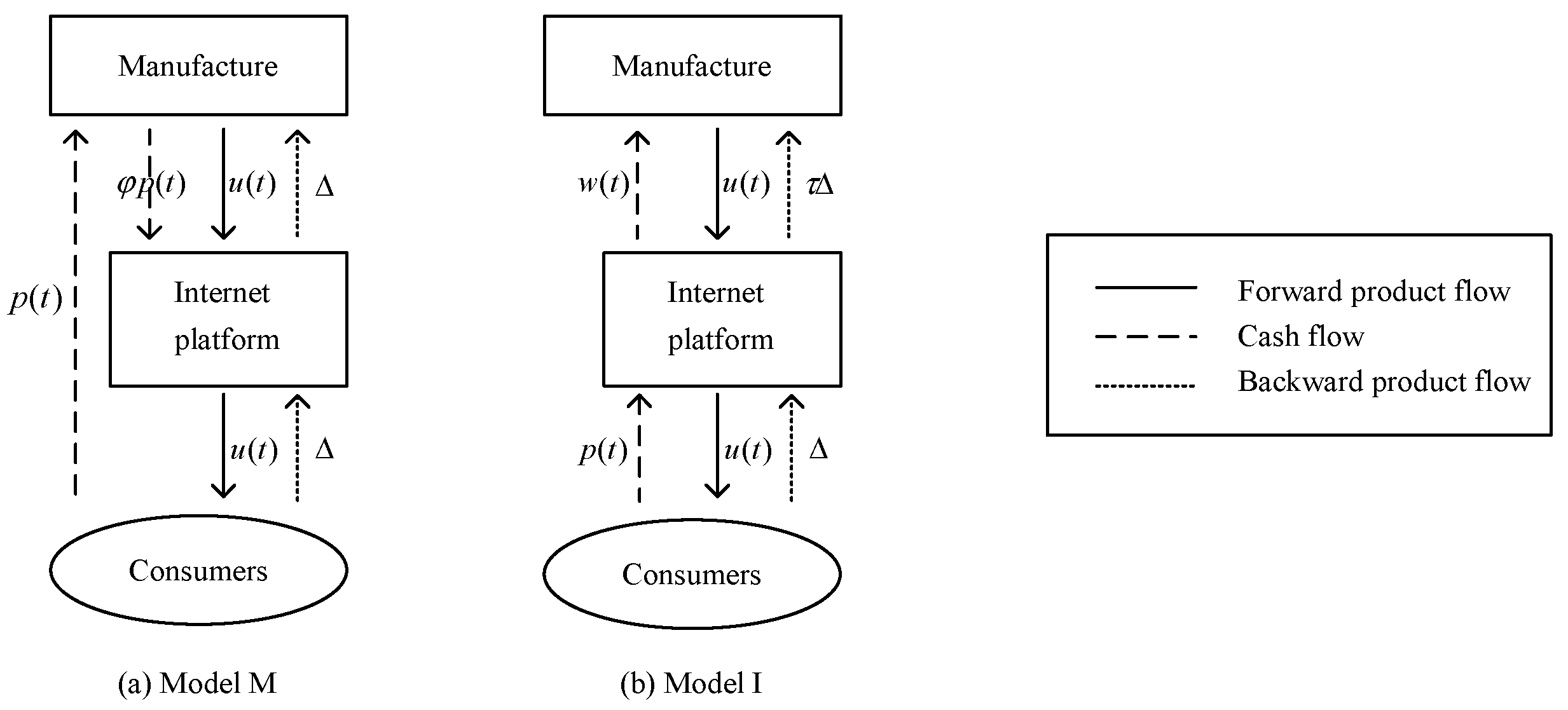

4.1. Manufacturer Offers Trade-in Service (Model M)

4.2. Retail Platform Offers Trade-in Service (Model I)

5. Model Analysis

6. Numerical Calculation Examples

- (i)

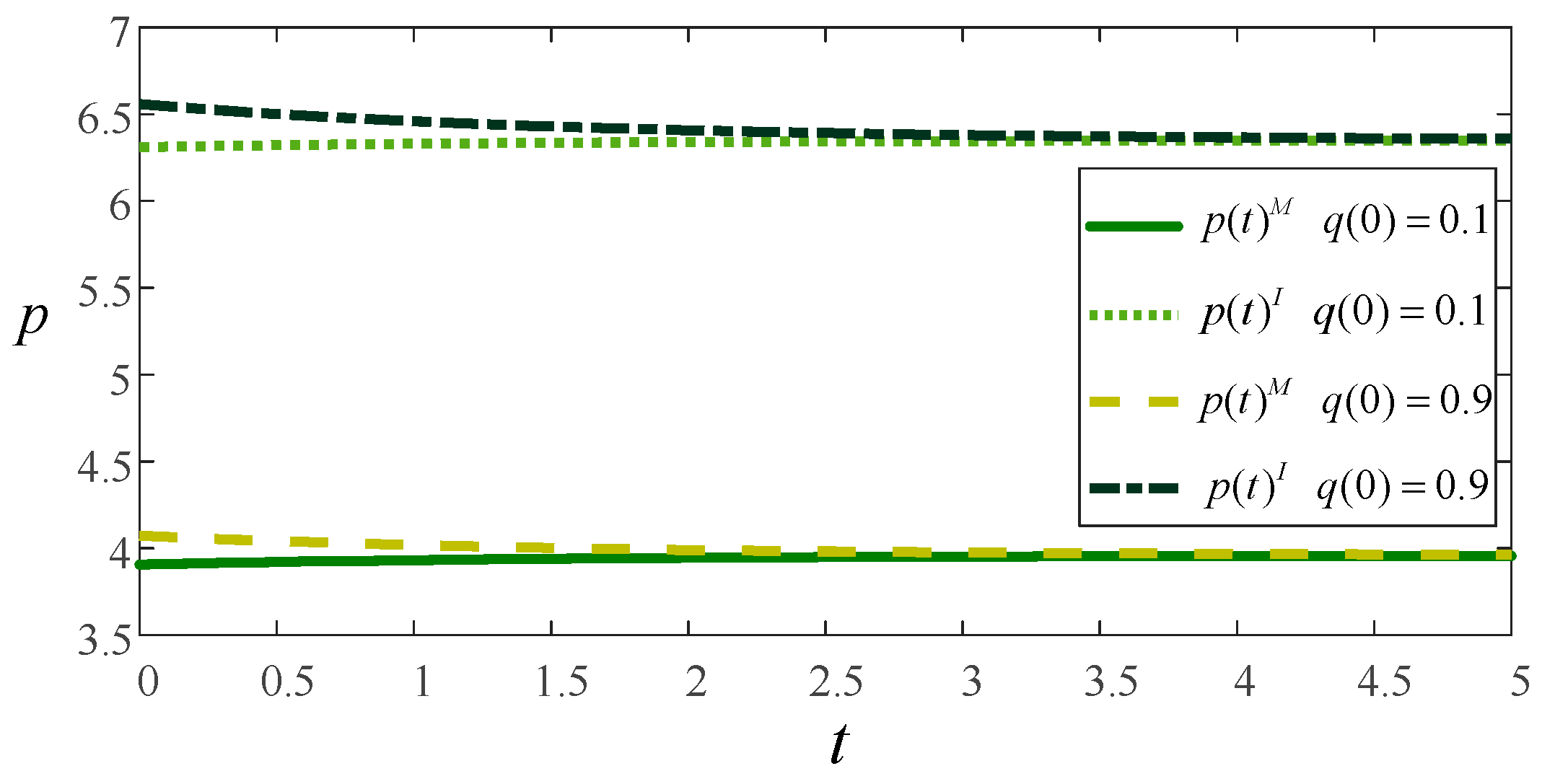

- For innovative companies, particularly those offering products with initially high quality, a skimming pricing strategy is typically employed during the early stages of market entry. This involves setting a relatively high price to attract consumers seeking advanced features, high technological content, and innovative qualities—often referred to as early adopters or tech enthusiasts. After capturing a significant portion of the profit through this approach, the company gradually reduces prices to appeal to a broader consumer base, thereby increasing overall demand. For example, Tesla’s early supercar models, such as the Roadster, were priced above 500,000 yuan. By leveraging patents related to autonomous driving and click technology, Tesla attracted numerous users interested in technological innovation. However, as technological maturity and supply chain stability improve, Tesla has progressively introduced mid-to-high-end models aimed at the mass market.10

- (ii)

- For growing companies, particularly those whose initial product quality is not high, a penetration pricing strategy is typically employed. By setting low prices, these companies can rapidly capture market share and achieve substantial short-term profits. Such pricing also tends to attract pragmatic consumers who prioritize value. As sales extend over time and product performance diminishes, firms need to invest in technological improvements to attract additional customers. The costs incurred during this process can lead to an increase in product prices. For example, Lenovo adopted a similar marketing approach when introducing the Pentium-based computers into the Chinese market. Initially, they quickly gained market share through competitive pricing, establishing themselves as a leading player in China’s desktop computer industry at the time. Subsequently, through continuous technological innovation and R&D, they gradually launched more advanced product categories.11

7. Extension

7.1. Consideration of Government Subsidies

7.2. Net Residual Value of Asymmetrically Recovered Products

8. Conclusions and Management Insights

8.1. Conclusions

- (i)

- In the retail platform-led trade-in resale model, there is a double marginalization effect from the wholesale price to the retail price, which makes the market price of the product in the Model I constantly higher than that of the product in the Model M. The size of the quality improvement inputs in both models depends heavily on the net residual value of the recovered product.

- (ii)

- We observe that innovative companies tend to adopt a skimming pricing strategy, setting higher initial prices to attract early adopters. Subsequently, they gradually reduce quality and prices to appeal to more pragmatic consumers. In contrast, growing firms often employ penetration pricing by initially setting low prices to rapidly capture market share and attract pragmatic buyers. They then increase investment in quality improvements and raise market prices to attract more early adopters.

- (iii)

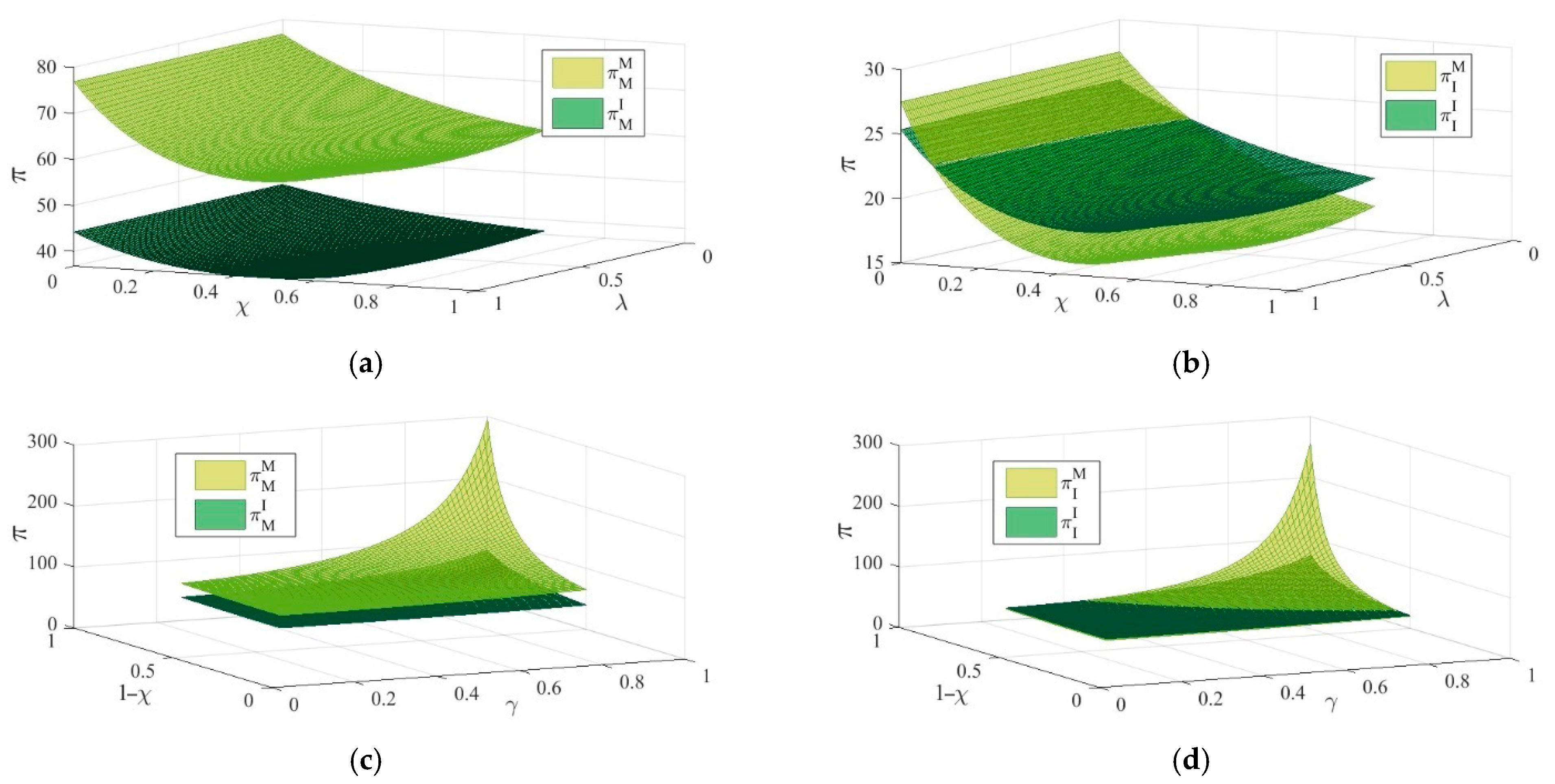

- Focus on the impact of consumer segmentation based on quality preferences on profitability. The results indicate that pragmatic consumers and innovative consumers have completely opposite effects on the profitability of manufacturers and platforms under both models. Specifically, the larger the market share of pragmatic consumers and the more sensitive they are to quality, the lower the profits manufacturers and retail platforms can achieve in the trade-in programs. Conversely, a higher market share of innovative consumers and greater sensitivity to quality enhance the profitability of supply chain members.

- (iv)

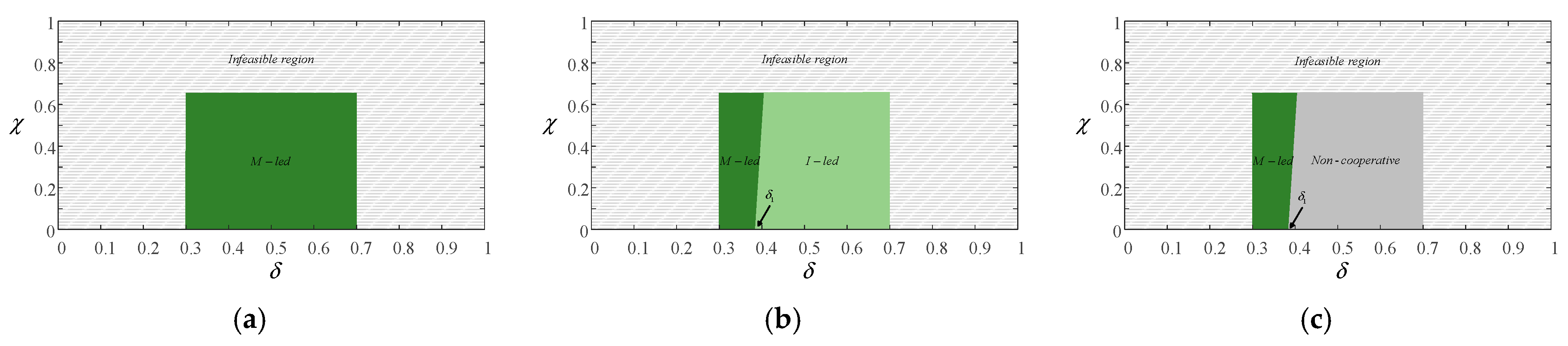

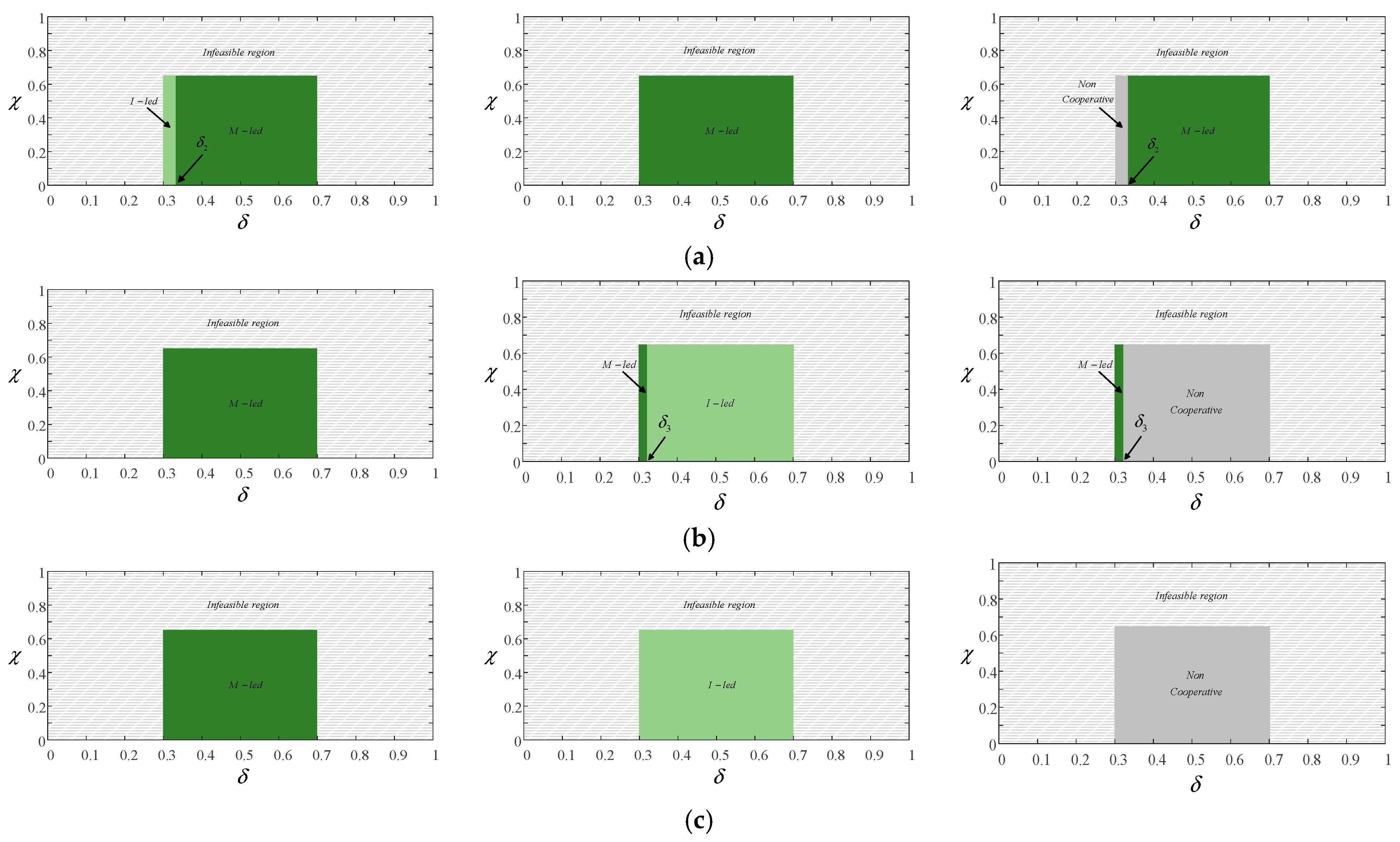

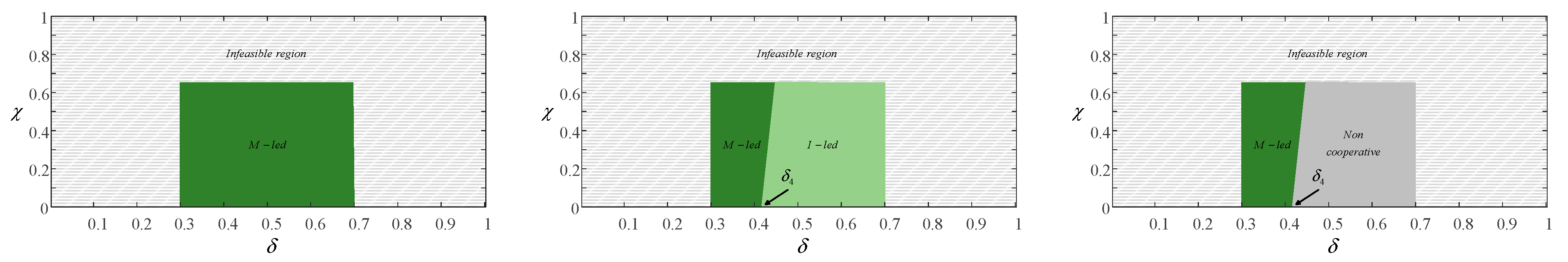

- Regarding the question of who should lead the trade-in program. From an economic efficiency perspective, the manufacturer generally prefers to take the lead in the trade-in process. The retail platform tends to delegate the trade-in authority to the manufacturer when product decay rates are low, whereas they prefer to control the trade-in process themselves when degradation rates are high. The equilibrium where both parties are satisfied occurs when the manufacturer leads the trade-in program under conditions of low product degradation. Considering social and environmental benefits, manufacturer-led trade-in initiatives consistently outperform retail platform-led programs.

- (v)

- Regarding the impact of consumer segmentation on the choice of the trade-in model, we find that the market share of different consumer types can significantly affect the selection of the trade-in approach. As the product decay rate increases, a higher proportion of pragmatic consumers in the market encourages the manufacturer and the retail platform to favor a manufacturer-led trade-in scheme.

- (vi)

- When considering the impact of government subsidies on the choice of the trade-in model, the manufacturer tends to lead the trade-in cooperation when their subsidy support is stronger and the product quality decay rate is high. When both parties receive equal subsidy support, they also prefer manufacturer-led trade-in arrangements when the product quality decay rate is low. However, if the retail platform’s subsidy support is greater, the supply chain members are unable to reach a cooperative agreement.

- (vii)

- Considering the impact of asymmetric net residual values of recovered products on the choice of the trade-in model, a higher net residual value for manufacturer-recovered products compared to retail platform-recovered products will lead both parties to favor a broader scope of manufacturer-led trade-in programs.

8.2. Management Insights

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| M-led | Manufacturer offer trade-in service |

| I-led | Retail platform offer trade-in service |

Appendix A

References

- Van Ackere, A.; Reyniers, D.J. Trade-ins and introductory offers in a monopoly. Rand J. Econ. 1995, 26, 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhai, X.; Chen, L. Optimal pricing strategy under trade-in program in the presence of strategic consumers. Omega 2019, 84, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, S.; Boyaci, T.; Aras, N. Optimal prices and trade-in rebates for durable, remanufacturable products. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2005, 7, 208–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Ma, Z.J.; Dai, Y.; Choi, T.M. Upstream or downstream: Who should provide trade-in services in dyadic supply chains? Decis. Sci. 2021, 52, 1071–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Z.; Ignatius, J.; Chai, J.; Valiyaveettil, K.M.T. To Cooperate or Not: Evaluating process innovation strategies in battery recycling and product innovation. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2025, 283, 109559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Chen, X.; Dasgupta, S. Can trade-ins hurt you? Exploring the effect of a trade-in on consumers’ willingness to pay for a new product. J. Mark. Res. 2008, 45, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Rao, R.S.; Kim, K.; Rao, A.R. More or less: A model and empirical evidence on preferences for under-and overpayment in trade-in transactions. J. Mark. Res. 2011, 48, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezrachi, A.; Stucke, M.E. The curious case of competition and quality. J. Antitrust Enforc. 2015, 3, 227–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Liu, X. Equilibrium decisions for multi-firms considering consumer quality preference. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 227, 107688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, K.; Xu, F.; Fan, C. Management of trade-in modes by recycling platforms based on consumer heterogeneity. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2022, 162, 102721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.H.; Yoon, N.; Chool, H.J. Consumer Segmentation Based on Clothing Purchasing Behavior—The Case of South Korea. China Sci. Technol. Rev. 2015, 37, 104–113. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.; Wang, L.; Chen, J. Dynamic pricing in a trade-in program with replacement and new customers. Nav. Res. Logist. NRL 2020, 67, 334–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Ma, Z.J.; Sheu, J.B. Optimal prices and trade-in rebates for successive-generation products with strategic consumers and limited trade-in duration. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2019, 124, 92–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Guo, X.; Wang, S. Optimal collection delegation strategies in a retail-/dual-channel supply chain with trade-in programs. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2022, 303, 633–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, Y.; Hong, J.; Song, J.; Leng, M. Game-theoretic analysis of trade-in services in closed-loop supply chains. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2021, 152, 102428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.; Li, H.; Tang, C.S. Optimal pricing of two successive-generation products with trade-in options under uncertainty. Decis. Sci. 2015, 46, 565–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, J.; Cao, K. Dynamic joint strategy of channel encroachment and logistics choice considering trade-in service and strategic consumers. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2024, 185, 103528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genc, T.S.; De Giovanni, P. Trade-in and save: A two-period closed-loop supply chain game with price and technology dependent returns. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017, 183, 514–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, P.; Gong, Y.; Mirchandani, P. Trade-in for remanufactured products: Pricing with double reference effects. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 230, 107800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, V.V.; Ferguson, M.; Souza, G.C. Trade-in rebates for price discrimination and product recovery. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2016, 63, 326–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Jia, D.; Zheng, B. The manufacturer’s trade-in partner choice and pricing in the presence of collection platforms. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2022, 168, 102947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Tian, L. Optimizing prices in trade-in strategies for vehicle retailers. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 122004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X. Effects of double subsidies and consumers’ acceptability of remanufactured products on a closed-loop supply chain with trade-in programs. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 447, 141565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, Z.; Gu, Q. ESG and trade credit: Evidence from an emerging market: H. Wanf et. al. Rev. Quant. Financ. Account. 2025, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Feng, L.; Chen, X.; Yang, L.; Choi, T.M. Impacts of selling models: Who should offer trade-in programs in e-commerce supply chains? Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2024, 186, 103524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y. Choosing the right exchange-old-for-new programs for durable goods with a rollover. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2017, 259, 512–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Z.; Fu, K.; Xia, Z.; Wang, Y. Models for closed-loop supply chain with trade-ins. Omega 2017, 66, 308–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Wang, X.J.; Chin, K.S. Trade-in strategies in retail channel and dual-channel closed-loop supply chain with remanufacturing. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2020, 136, 101898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, G.; Ma, L.; Wei, K.; Zhang, Q. Does implementing trade-in and green technology together benefit the environment? In Operations Management for Environmental Sustainability: Operational Measures, Regulations and Carbon Constrained Decisions; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 85–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Tang, W.; Wei, L.; Zhang, J. Price distortion forced by recycling competition under trade-in collaboration. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2024, 62, 7687–7703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.J.; Fong, D.K.; Xu, S.H. Managing trade-in programs based on product characteristics and customer heterogeneity in business-to-business markets. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2011, 13, 108–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Zhou, S.X. Trade-in for cash or for upgrade? Dynamic pricing with customer choice. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2020, 29, 856–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Feng, L.; Govindan, K.; Xu, F. Effects of a secondary market on original equipment manufactures’ pricing, trade-in remanufacturing, and entry decisions. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2019, 279, 751–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Li, Y.; Xu, F.; Deng, Q. Optimal pricing and trade-in policies in a dual-channel supply chain when considering market segmentation. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 2828–2846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zhang, R. Trade-in remanufacturing, customer purchasing behavior, and government policy. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2018, 20, 601–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Tang, Y. Impact of product sharing and heterogeneous consumers on manufacturers offering trade-in programs. Omega 2024, 122, 102949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Dai, Y.; Ma, Z.J.; Choi, T.M. Trade-in operations under retail competition: Effects of brand loyalty. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 310, 397–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Zhu, S.X.; Fu, K. Optimal trade-in and refurbishment strategies for durable goods. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 309, 133–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudzadeh, M. On the Non-Equivalence of Trade-ins and Upgrades in the Presence of Framing Effect: Experimental Evidence and Implications for Theory. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2020, 29, 330–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Li, Y.; Fan, C. Optimization of pricing and quality choice with the coexistence of secondary market and trade-in program. Ann. Oper. Res. 2020, 349, 803–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, D.; Mahapatra, S.; Webster, S. A comparison of buyback and trade-in policies to acquire used products for remanufacturing. J. Bus. Logist. 2017, 38, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvin, D.A. Competing in the Eight Dimensions of Quality. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1987, 87, 101–109. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, Z.; Day, S.J.; Ignatius, J.; Dhamotharan, L.; Chai, J. Digital advertising spillover, online-exclusive product launches, and manufacturer-remanufacturer competition. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2024, 313, 565–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, T.M.; Chan, H.K.; Yue, X. Recent development in big data analytics for business operations and risk management. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2016, 47, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, T.M.; Wallace, S.W.; Wang, Y. Big data analytics in operations management. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2018, 27, 1868–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Wang, M.; Chen, G.; Chen, X. The effect of implementing trade-in strategy on duopoly competition. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2016, 248, 856–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ma, D.; Hu, J. Reseller or Market? E-platform strategy under blockchain-enabled recycling. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 243, 122811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, A.; Narasimhan, R. Dynamics of competing with quality-and advertising-based goodwill. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2006, 175, 462–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, T.; Mukherjee, A.; Chauhan, S.S. Should a powerful manufacturer collaborate with a risky supplier? Pre-recall vs. post-recall strategies in product harm crisis management. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 177, 109037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Carvalho, M.; Zaccour, G. Managing quality and pricing during a product recall: An analysis of pre-crisis, crisis and post-crisis regimes. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 307, 406–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Huang, R.; Sarigöllü, E. Consumer product use behavior throughout the product lifespan: A literature review and research agenda. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 302, 114114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, J.; Hu, S.; Gui, L.; So, K.C.; Ma, Z.J. Optimal subsidy schemes and budget allocations for government-subsidized trade-in programs. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2021, 30, 2689–2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Giovanni, P.; Zaccour, G. A survey of dynamic models of product quality. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 307, 991–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asian, S.; Nie, X. Coordination in supply chains with uncertain demand and disruption risks: Existence, analysis, and insights. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2014, 44, 1139–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, T.M.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, T.E. Quick response in supply chains with stochastically risk sensitive retailers. Decis. Sci. 2018, 49, 932–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scenarios | Companies | Descriptions |

|---|---|---|

| Model M | HP (USA-CA) | HP regularly offers trade-in services for computer products, allowing market-valued second-hand devices to be exchanged for discounts on new purchases. |

| AT&T (USA-TX) | Consumers participating in AT&T’s trade-in program can exchange their old devices for promotional cards, which can be used to pay AT&T bills, purchase new devices, or accessories. | |

| Canon (Japan) | Canon allows consumers to replace their current camera with a new or refurbished Canon camera at a discounted price. | |

| IBM (USA-NY) | Customers in Canada and the U.S. can receive trade-in rebates from IBM if they purchase new equipment from an IBM business partner to replace older IBM equipment or competitively branded equipment. | |

| Model I | eBay (USA-CA) | A program called “Instant Sale” targeting smartphones, enabling consumers participating in the trade-in to receive vouchers for purchasing new devices. |

| Wish (USA-CA) | Starting in March 2024, customers in Europe can join in trade-in on Wish for devices such as smartphones, laptops and tablets. | |

| Gome (HongKong) | In 2016, Gome Butler, a delivery platform for high-quality home appliance after-sales service, formed a closed-loop business from the purchase of goods to re-purchase, in which “trade-in” became an important part of the service system. | |

| Shopee (Singapore) | Shopee offers trade-in programs for a variety of gaming consoles, smartphones and computer devices. Consumers who participate in the trade-in program receive “cash” directly towards the purchase of a new product. |

| Symbol | Definition |

|---|---|

| Exogenous parameter | |

| Market size | |

| Market share of pragmatic consumers | |

| Product quality decay rate | |

| Consumer price sensitivity | |

| Innovative consumers quality sensitivities | |

| Pragmatic consumers quality sensitivities | |

| Commission rates for retail platform when manufacturer dominate trade-in | |

| Percentage of net salvage value share of recycled products received by manufacturer when retail platform dominates trade-in | |

| Net residual value of recycled second-hand products | |

| Quality improvement input cost factor | |

| Initial product perceived quality | |

| Decision variables | |

| Product quality improvement inputs, as determined by the manufacturer | |

| Product sales price, as determined by the trade-in lead party | |

| Wholesale price, manufacturer’s decision when retail platform dominates trade-in | |

| State variable | |

| Perceived product quality at every moment | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, D.; Hu, D.; Hu, J. Considering Consumer Quality Preferences, Who Should Offer Trade-in Between Manufacturer and Retail Platform? Systems 2025, 13, 1043. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13111043

Ma D, Hu D, Hu J. Considering Consumer Quality Preferences, Who Should Offer Trade-in Between Manufacturer and Retail Platform? Systems. 2025; 13(11):1043. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13111043

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Deqing, Di Hu, and Jinsong Hu. 2025. "Considering Consumer Quality Preferences, Who Should Offer Trade-in Between Manufacturer and Retail Platform?" Systems 13, no. 11: 1043. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13111043

APA StyleMa, D., Hu, D., & Hu, J. (2025). Considering Consumer Quality Preferences, Who Should Offer Trade-in Between Manufacturer and Retail Platform? Systems, 13(11), 1043. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13111043