Systemic Assessment of IoT Readiness and Economic Impact in Postal Services

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Role and Potential of IoT in Postal and Courier Services

1.2. Systems Thinking and the Evaluation of Complex Innovations

1.3. Research Gap and Objective of the Research

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. IoTRIM Model: Readiness Assessment Methodology

- Digital Infrastructure.

- Data Collection and Processing.

- Integration and Interoperability.

- Strategic Orientation.

- Collectible, favoring data that can realistically be obtained from internal reports, databases, or structured expert interviews.

- Comparable, allowing benchmarking across organizations or time periods.

- Representative, capturing technological, data, organizational, and strategic aspects of IoT readiness.

- Flexible, enabling adaptation to other sectors beyond postal services.

2.2. Integration of IoTRIM into the Cobb–Douglas Production Function

- Y = value added (economic output),

- A = total factor productivity (TFP),

- L = labor input (e.g., number of employees or full-time equivalents),

- K = capital input (e.g., physical assets, IT infrastructure),

- I = IoT readiness index (composite score from IoTRIM),

- α, β, γ = elasticity coefficients of respective inputs.

2.3. Simulation and Estimation Approach

2.4. Hypotheses

3. Results

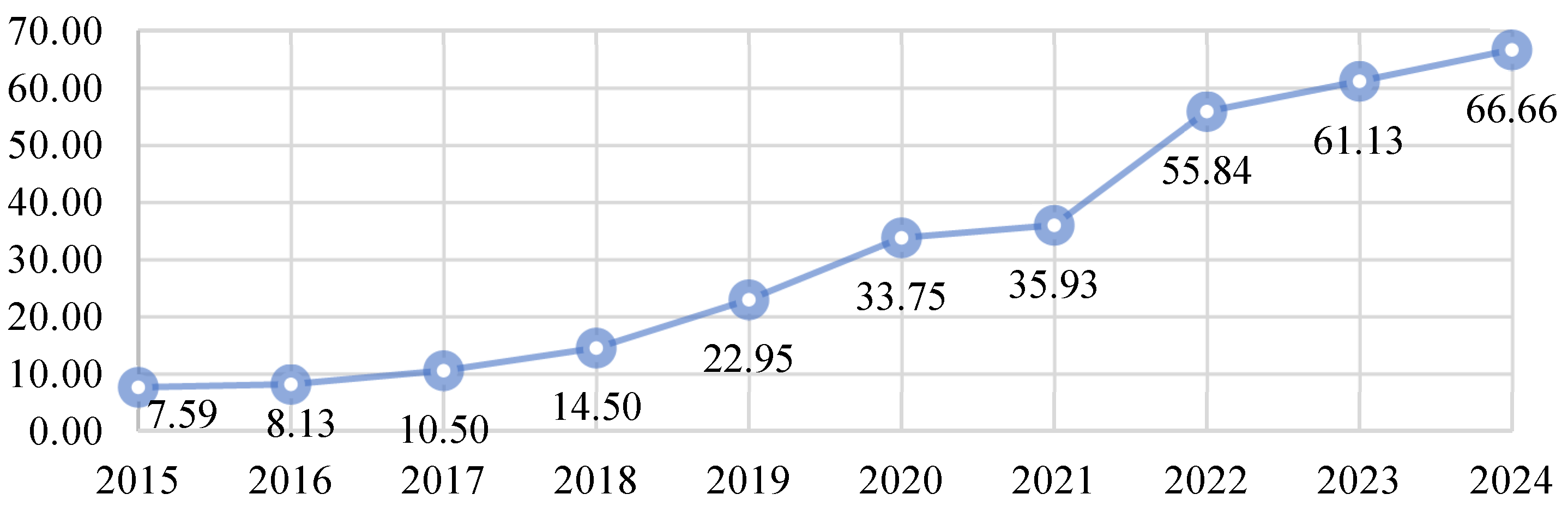

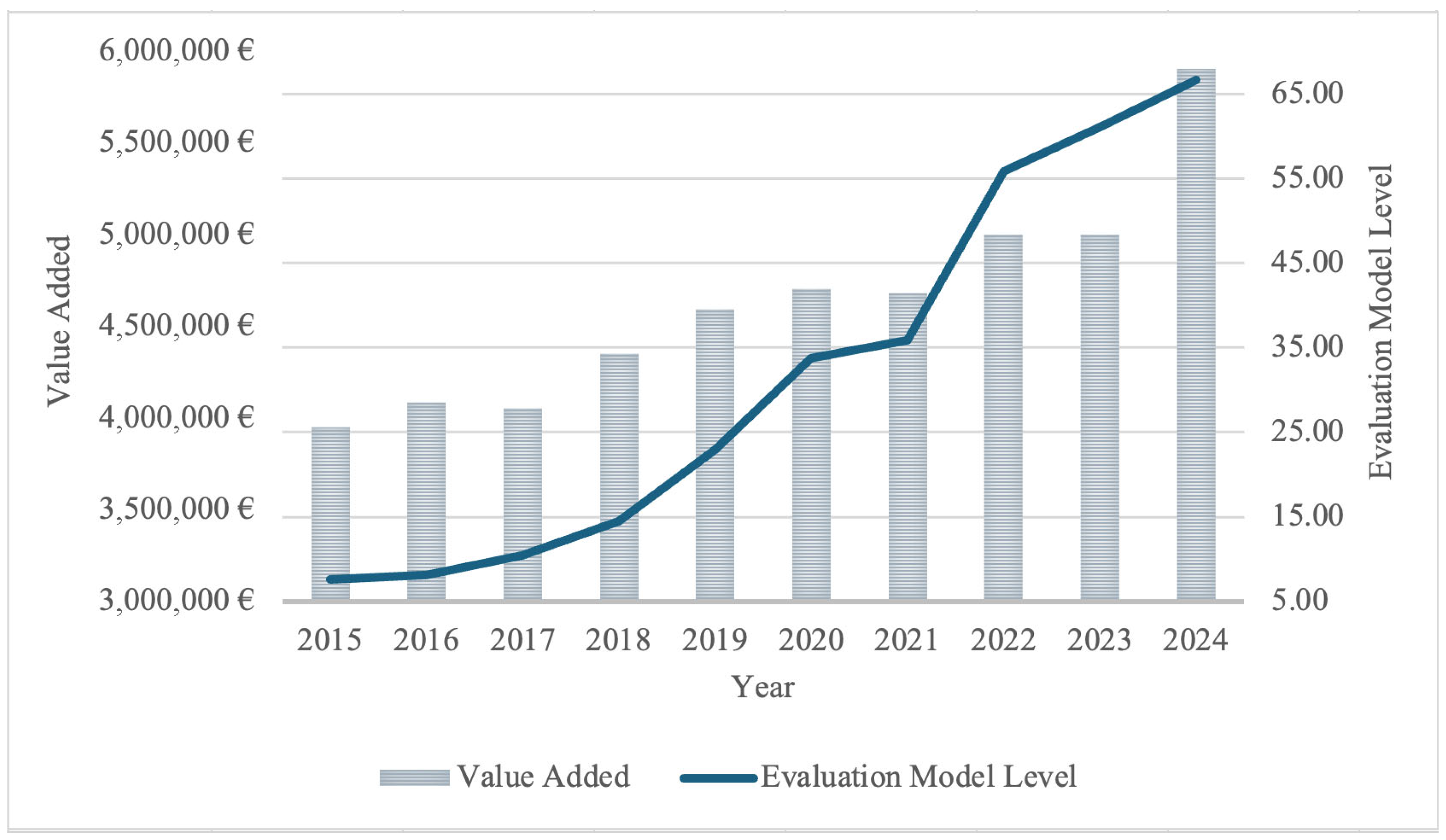

3.1. IoTRIM Model Outcomes

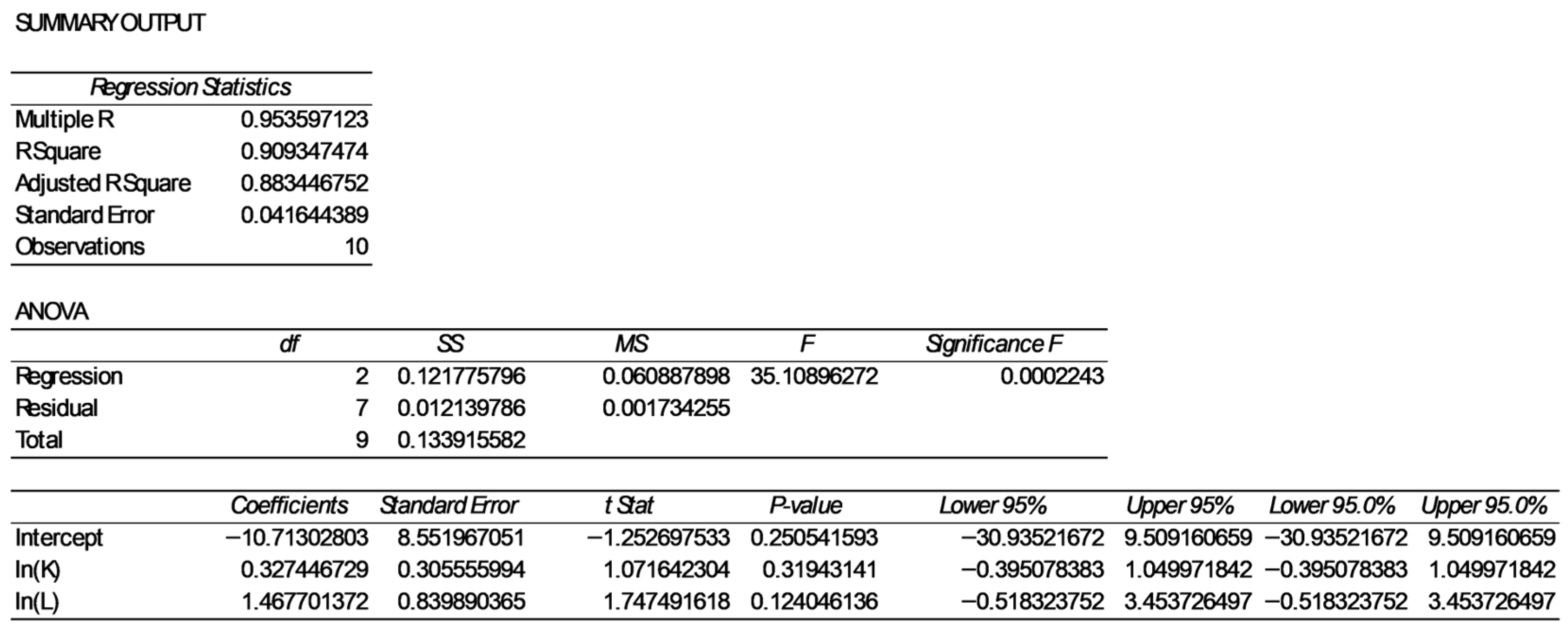

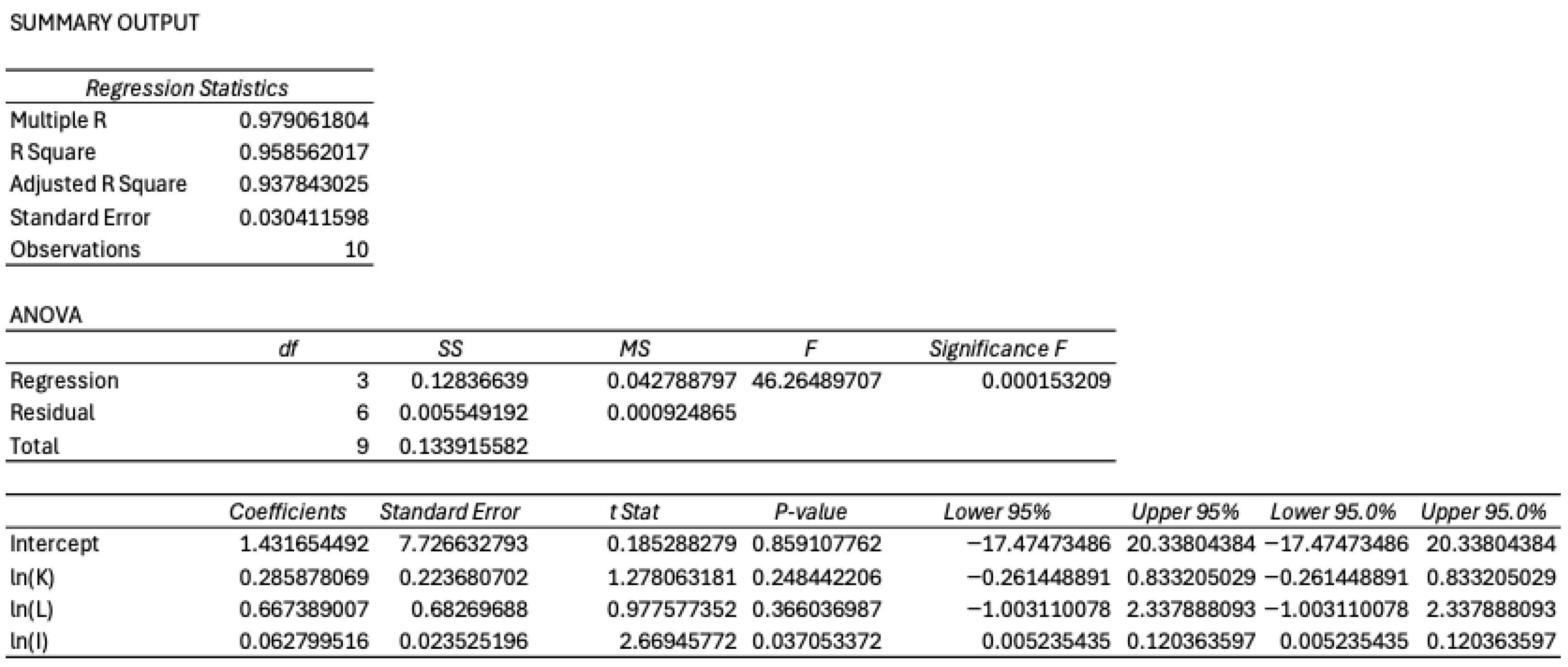

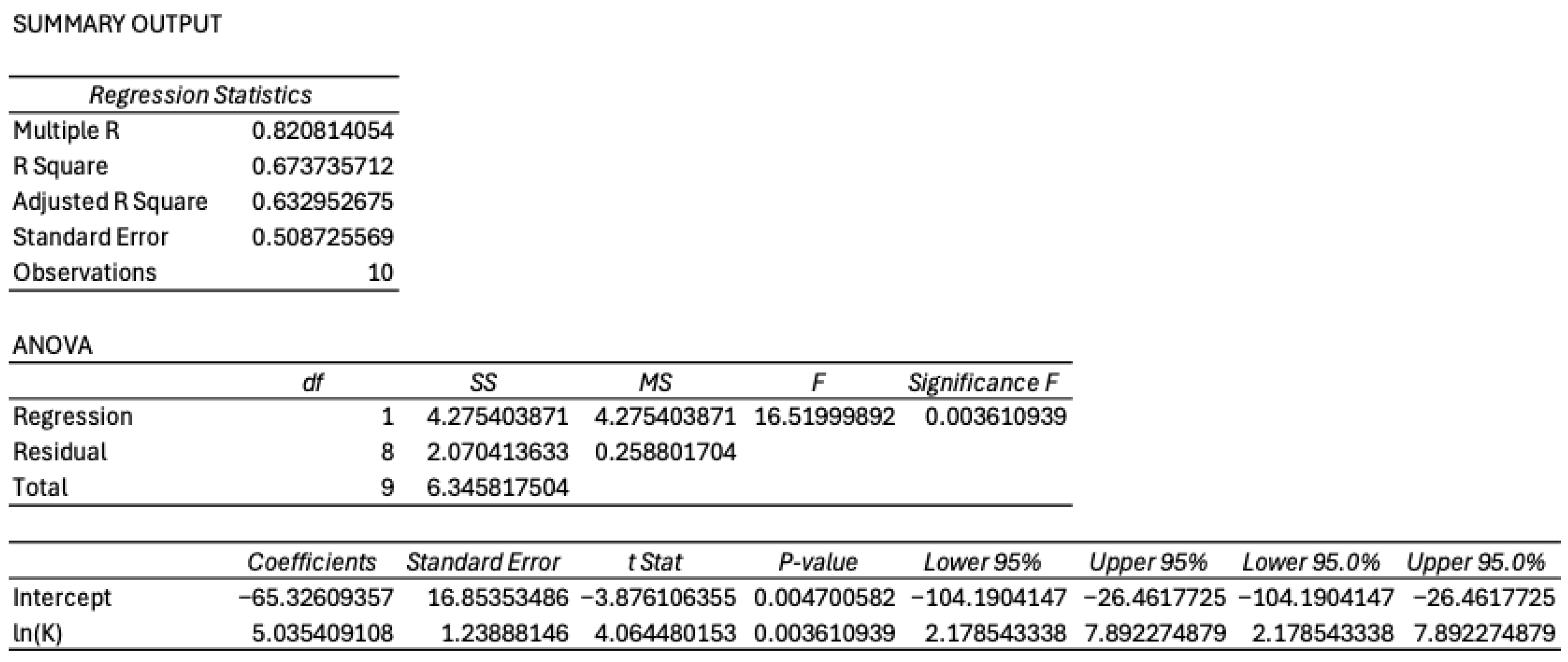

3.2. Extended Cobb–Douglas Production Function

3.2.1. Variance Inflation Factor and Tolerance

3.2.2. Comparison of Coefficients for the Basic and Extended Model

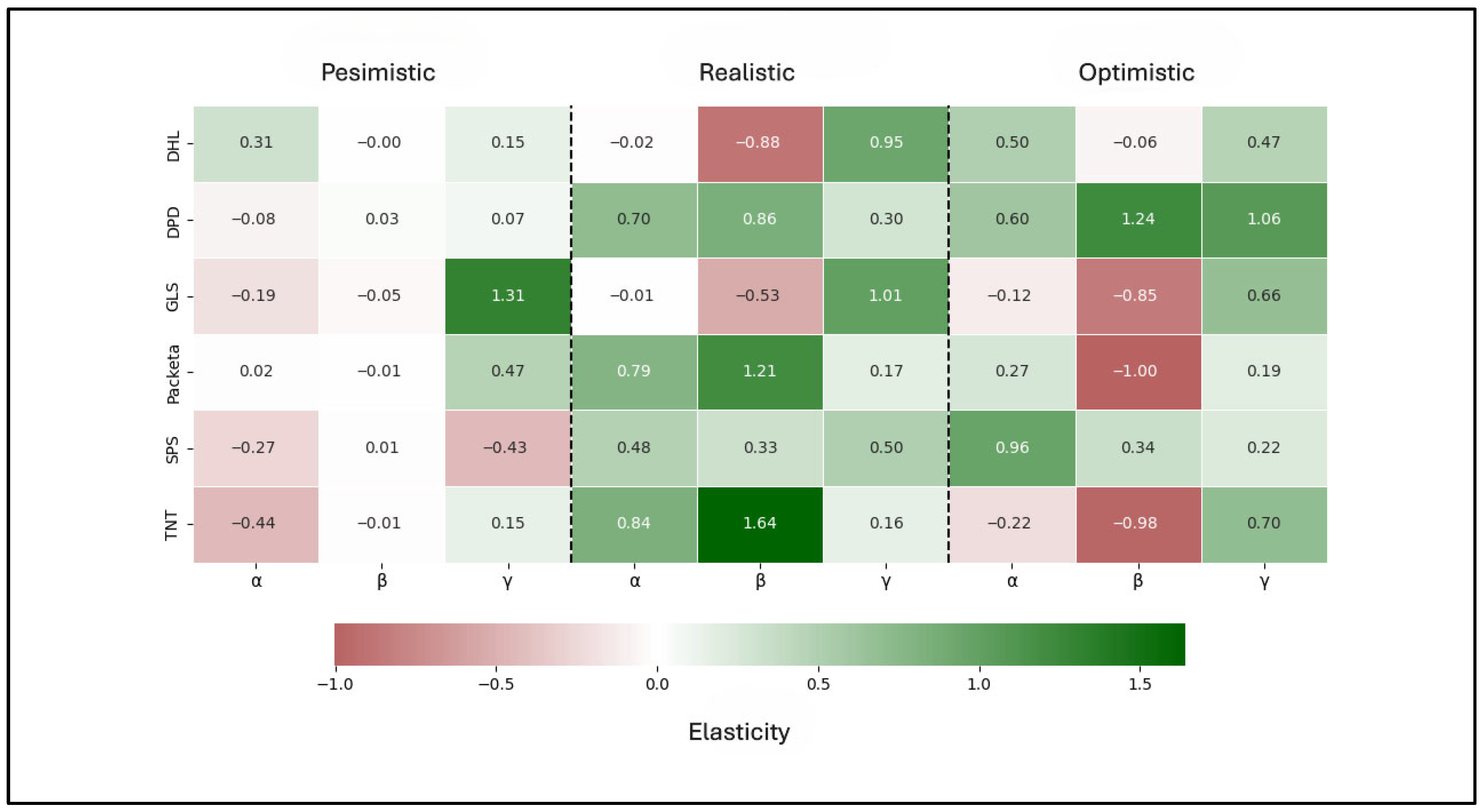

3.3. Scenario Analysis and Monte Carlo Simulation

- Pessimistic scenario: Characterized by adverse macroeconomic conditions, weak investment activity, and slow technological uptake. Under these conditions, output (Y) remains stagnant or declines, capital investment (K) grows minimally, and IoT readiness (I) advances only marginally, while labor (L) changes little. This scenario may correspond to environments with technological debt, operational inefficiencies, or disruptive external shocks, such as regulatory hurdles or prolonged economic downturns.

- Realistic scenario: Represents a continuation of current sectoral trends, with balanced growth in all key variables. Output and capital expand moderately, labor demand remains stable with minor fluctuations, and IoT readiness rises gradually in line with steady digitalization initiatives. Such a trajectory aligns with historical averages and assumes a supportive but not exceptional macroeconomic environment.

- Optimistic scenario: Envisions strong macroeconomic performance, substantial digital investment, and accelerated organizational transformation. Capital and output increase at the highest rates, IoT readiness achieves the most substantial gains, and labor requirements decrease in certain areas due to process automation. This trajectory aligns with global best-practice adoption curves for advanced logistics and smart supply chain systems.

3.3.1. Simulation Highlights

3.3.2. Elasticity Patterns

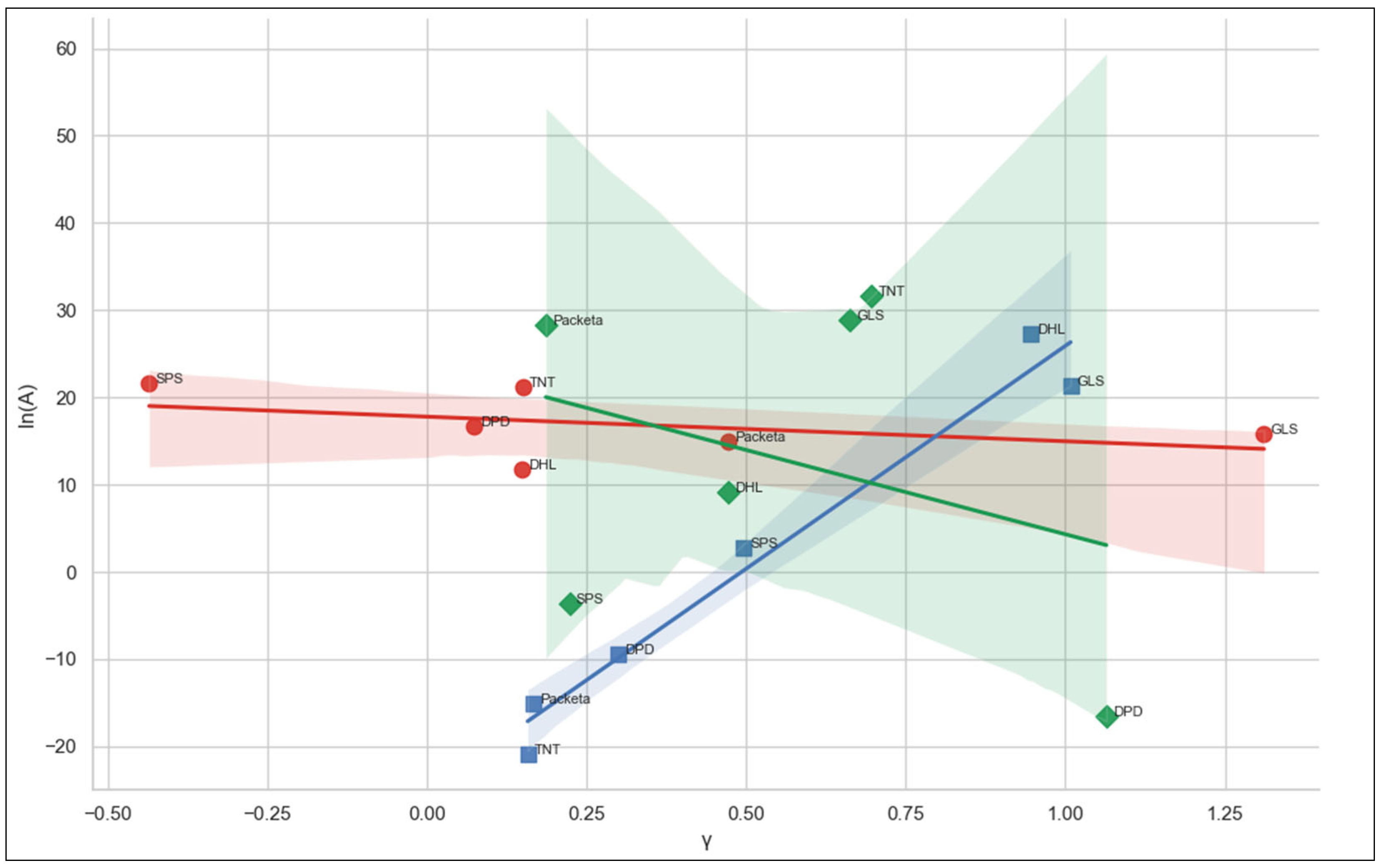

3.3.3. Total Factor Productivity

3.4. Hypothesis Verification

3.4.1. Hypothesis H1

3.4.2. Hypothesis H2

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| IoTRIM | IoT Readiness & Impact Model |

| IT | Information Technology |

| SSE | Sum of Squared Residuals |

| TFP | Total Factor Productivity |

| VIF | Variance Inflation Factor |

Appendix A

| Indicator | Description |

|---|---|

| Ratio of IoT devices per employee | This indicator provides a detailed view of the organization’s technical readiness for IoT implementation. It serves as a key input for assessing overall digital maturity and identifying areas for improvement. Higher values typically correlate with greater automation, stronger system integration, and better responsiveness to operational needs. It is important to track this indicator over time and benchmark it across the industry to evaluate the enterprise’s competitive position in IoT. ➔ Evaluation: 0–100% |

| Share of devices connected in real time | This indicator expresses the extent to which devices are directly connected to the network in real time, which is essential for ensuring immediate responsiveness to operational stimuli. A higher value indicates the ability of the enterprise to dynamically react to changes in the environment or technical conditions. Real-time connectivity provides valuable data for process management, predictive maintenance, and instant decision-making. ➔ Evaluation: 0–100% |

| Share of company premises covered by high-throughput network | This indicator measures the coverage of the enterprise with next-generation networks (e.g., Wi-Fi 6) that allow stable high-capacity data transmission. Availability of such networks is crucial for modern IoT solutions, especially in data-intensive environments. Greater coverage ensures reliable data transfer and supports the scalability of digital solutions. ➔ Evaluation: 0–100% |

| Number of connection outages per month | The number of outages represents an important indicator of the reliability and stability of digital infrastructure. Frequent outages may cause data loss, process interruptions, and reduced trust in IoT solutions. A low frequency of outages indicates a robust network that enables continuous monitoring, data collection, and real-time management. ➔ Evaluation: 0–100% (0/month—100%; 1–4/month—75%; 5–8/month—50%; 9–12/month—25%; >12/month—0%) |

| Share of sensor-acquired data in total data volume | This indicator shows the proportion of data collected through sensors and IoT devices. Sensor-based data are more accurate and timelier, enabling greater automation of processes. A higher share supports the development of a data-driven enterprise and opens opportunities for advanced analytics and predictive modeling. ➔ Evaluation: 0–100% |

| Frequency of data collection | This indicator signals how often the enterprise collects data from its IoT systems. More frequent collection increases decision-making accuracy but requires stronger processing capacities. It balances technical capabilities with operational efficiency. ➔ Evaluation: 0–100% (continuous/<1 s—100%; 1×/1 min—80%; 1×/5 min—60%; 1×/hour—40%; 1×/day—20%; irregular—0%) |

| Share of analytical reports generated monthly | The share of analytical reports generated monthly based on IoT data indicates the extent to which enterprises exploit their data sources for process management and optimization. A higher share reflects advanced use of analytics, supports evidence-based decision-making, and demonstrates digital maturity in data management. ➔ Evaluation: 0–100% |

| Share of automatically processed data | This indicator reflects the degree to which data are processed automatically, without manual intervention. Automation shortens the time between data collection and its use, contributing to rapid process optimization. It also signals advanced data infrastructure and system integration. ➔ Evaluation: 0–100% |

| Existence of an IoT data management platform | This indicator captures whether the enterprise has a platform for managing, monitoring, and visualizing IoT data. Such platforms enable centralized oversight of system performance, support decision-making, and ensure transparency. They are a fundamental tool for effective IoT utilization. ➔ Evaluation: 0–100% (available—100%; not available—0%) |

| Share of departments. using IoT data in decision-making | This indicator expresses the extent to which IoT data are used in enterprise decision-making across departments. It shows whether technologies are strategically embedded or remain marginal. A higher share indicates greater digital maturity and organizational integration. ➔ Evaluation: 0–100% |

| Share of systems connected via API / middleware | This indicator measures the degree of technical integration through standardized interfaces (e.g., APIs, middleware). Such connections enable real-time data exchange, minimize duplication, and enhance interoperability. ➔ Evaluation: 0–100% |

| Share of IoT systems integrated with ERP/CRM/SCM | This indicator tracks the integration of IoT systems with core business applications such as ERP, CRM, or SCM. Integration ensures seamless data flows across organizational levels and supports coordinated decision-making. It is a sign of a mature digital architecture. ➔ Evaluation: 0–100% |

| Share of IoT devices connected via cloud services | This indicator expresses the extent to which IoT devices are connected through cloud services. Cloud solutions provide flexibility, scalability, and real-time availability of data, increasing efficiency and reducing server costs. ➔ Evaluation: 0–100% |

| Existence of unified data interface for IoT data | This indicator evaluates whether a unified data interface exists to ensure consistent access to IoT data across systems and departments. It reduces risks of data fragmentation and enables effective analysis. ➔ Evaluation: 0–100% (available—100%; not available—0%) |

| Existence of standardized protocol (MQTT, CoAP) | This indicator reflects whether the enterprise uses standardized communication protocols that ensure interoperability between IoT devices. Such protocols allow flexible integration of new components into existing systems. ➔ Evaluation: 0–100% (available—100%; not available—0%) |

| Share of devices supporting remote updates | This indicator measures the share of devices that support remote software updates, which are crucial for security, scalability, and reducing maintenance costs. ➔ Evaluation: 0–100% |

| Existence of centralized IoT device management across the entire network | This indicator captures whether a central management system exists for IoT devices across the enterprise. Such systems ensure unified control, greater security, and simplified maintenance. ➔ Evaluation: 0–100% (available—100%; not available—0%) |

| Share of IoT-related expenditure in total investment | This indicator evaluates the enterprise’s investment intensity in IoT technologies. A higher share indicates that digitalization is seen as a priority and that innovative activities are strategically supported. ➔ Evaluation: 0–100% |

| Number of IoT projects implemented in last two years | This indicator tracks the number of IoT projects implemented in the last two years. It signals the enterprise’s technological activity and adaptation to changing market conditions. ➔ Evaluation: 0–100% (≥4 projects—100%; 3 projects—75%; 2 projects—50%; 1 project—25%; none—0%) |

| Existence of a company-level IoT strategy | This indicator evaluates whether the enterprise has a formally defined IoT strategy at the top management level. The presence of such a strategy signals that digitalization is integrated into long-term development and transformation goals, ensuring coordinated implementation and resource allocation. ➔ Evaluation: 0–100% (available—100%; not available—0%) |

| Consideration of IoT data in management decision making | This indicator measures whether data collected from IoT systems are used in decision-making processes at different management levels. It reflects the link between technology infrastructure and management practice, fostering data-driven culture and transparency. ➔ Evaluation: 0–100% (used—100%; not used—0%) |

| Share of employees trained in IoT-related topics | This indicator expresses the share of employees trained in IoT, reflecting the preparedness of human capital to work with new technologies. Skilled staff are a prerequisite for effective IoT implementation. ➔ Evaluation: 0–100% |

| Existence of a performance monitoring system for IoT projects | This indicator tracks the presence of tools for monitoring IoT project performance (e.g., KPIs, dashboards). Transparency and monitoring capabilities increase implementation success. ➔ Evaluation: 0–100% (available—100%; not available—0%) |

| Existence of regular internal audits of IoT implementation | This indicator evaluates whether the enterprise conducts regular audits or evaluations of IoT initiatives. Such practices demonstrate control capacity and continuous improvement. ➔ Evaluation: 0–100% (present—100%; not present—0%) |

Appendix B

References

- Zaoui, F.; Souissi, N. Roadmap for digital transformation: A literature review. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2020, 175, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vial, G. Understanding digital transformation: A review and a research agenda. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2019, 28, 118–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobble, M.M. Digital strategy and digital transformation. Res.-Technol. Manag. 2018, 61, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupeika-Apoga, R.; Petrovska, K.; Bule, L. The effect of digital orientation and digital capability on digital transformation of SMEs during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2022, 17, 669–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzolla, G.; Anderson, J. Digital transformation. Bus. Strategy Rev. 2008, 19, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhlongo, S.; Mbatha, K.; Ramatsetse, B.; Dlamini, R. Challenges, opportunities, and prospects of adopting and using smart digital technologies in learning environments: An iterative review. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schallmo, D.R.; Williams, C.A. History of digital transformation. In Digital Transformation Now! Guiding the Successful Digitalization of Your Business Model; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usai, A.; Fiano, F.; Petruzzelli, A.M.; Paoloni, P.; Briamonte, M.F.; Orlando, B. Unveiling the impact of the adoption of digital technologies on firms’ innovation performance. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.S. Sustainable growth variables by industry sectors and their influence on changes in business models of SMEs in the era of digital transformation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupeika-Apoga, R.; Petrovska, K. Barriers to sustainable digital transformation in micro-, small-, and medium-sized enterprises. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, H.; Marasini, D.P.; Lee, D. Digital transformation trends in service industries. Serv. Bus. 2023, 17, 11–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Jones, P.; Kailer, N.; Weinmann, A.; Chaparro-Banegas, N.; Roig-Tierno, N. Digital transformation: An overview of the current state of the art of research. Sage Open 2021, 11, 21582440211047576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto Setzke, D.; Riasanow, T.; Böhm, M.; Krcmar, H. Pathways to digital service innovation: The role of digital transformation strategies in established organizations. Information Systems Frontiers 2023, 25, 1017–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnet, D.; Westerman, G. The new elements of digital transformation. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2021, 62, 82–89. [Google Scholar]

- Shehadeh, M.; Almohtaseb, A.; Aldehayyat, J.; Abu-AlSondos, I.A. Digital transformation and competitive advantage in the service sector: A moderated-mediation model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, M.I.; Abbas, Q.; Alyas, T.; Alzahrani, A.; Alghamdi, T.; Alsaawy, Y. Digital transformation of public sector governance with IT service management–A pilot study. IEEE Access 2021, 11, 6490–6512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokgohloa, K.; Kanakana-Katumba, M.G.; Maladzhi, R.W.; Xaba, S. Postal digital transformation dynamics—A system dynamics approach. Systems 2023, 11, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samambet, M.; Khouangvichit, C. Outsmarting the hurdles to digitalizing the postal sector: The case of deutsche post, poste italiane, and royal mail. Int. J. Prof. Bus. Rev. 2025, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikavica, B.; Blagojević, M.; Kostić-Ljubisavljević, A. Digital transformation of postal services–key success triggers. In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Advances in Traffic and Communication Technologies, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 26–27 May 2022; pp. 93–98. [Google Scholar]

- Papanikolaou, A.; Varvarousi, E.; Gavala, E. Postal sector digitalisation: Security and vulnerabilities. Int. J. Appl. Syst. Stud. 2024, 11, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onifade, A.Y.; Dosumu, R.E.; Abayomi, A.A.; Agboola, O.A.; Ogeawuchi, J.C. Systematic review of data-integrated GTM strategies for logistics and postal services modernization. Int. J. Sci. Res. Sci. Technol. 2024, 11, 587–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdolsek Draksler, T.; Cimperman, M.; Obrecht, M. Data-driven supply chain operations—The pilot case of postal logistics and the cross-border optimization potential. Sensors 2023, 23, 1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagala, G.H.; Őri, D. Toward SMEs digital transformation success: A systematic literature review. Inf. Syst. E-Bus. Manag. 2024, 22, 667–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soori, M.; Arezoo, B.; Dastres, R. Internet of things for smart factories in industry 4.0, a review. Internet Things Cyber-Phys. Syst. 2023, 3, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illakya, T.; Keerthana, B.; Murugan, K.; Venkatesh, P.; Manikandan, M.; Maran, K. The role of the internet of things in the telecom sector. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Communication, Computing and Internet of Things, Paris, France, 27–29 September 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baláž, M.; Vaculík, J.; Corejova, T. Evaluation of the impact of the internet of things on postal service efficiency in Slovakia. Economies 2024, 12, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, H.; Kling, G.; McGroarty, F.; O’Mahony, M.; Ziouvelou, X. Estimating the impact of the Internet of Things on productivity in Europe. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashat, R.M.; Abourokbah, S.H.; Salam, M.A. Impact of internet of things adoption on organizational performance: A mediating analysis of supply chain integration, performance, and competitive advantage. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, K.; Mohamed, M.; Mohamed, A.W. Internet of Things (IoT) in supply chain management: Challenges, opportunities, and best practices. Sustain. Mach. Intell. J. 2023, 2, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, M.; Gamal, A.; Ahmed, A.I.; Said, L.A.; Elbaz, A.; Herencsar, N.; Soltan, A. Internet of things: A comprehensive overview on protocols, architectures, technologies, simulation tools, and future directions. Energies 2023, 16, 3465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaia, C.; Michaelides, M.P. A review of wireless positioning techniques and technologies: From smart sensors to 6G. Signals 2023, 4, 90–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, K.; Abdelhafid, M.; Kamal, K.; Ismail, N.; Ilias, A. Intelligent driver monitoring system: An Internet of Things-based system for tracking and identifying the driving behavior. Comput. Stand. Interfaces 2023, 84, 103704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, R.; Bajwa, A.; Siddiqui, N.A.; Ahmed, I. Predictive Maintenance In Industrial Automation: A Systematic Review Of IOT Sensor Technologies And AI Algorithms. Am. J. Interdiscip. Stud. 2024, 5, 01–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ileana, M.; Petrov, P.; Milev, V. Optimizing customer experience by exploiting real-time data generated by IoT and leveraging distributed web systems in CRM systems. IoT 2025, 6, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.L.; Lassen, A.; Li, C.; Møller, C. Exploring the value of IoT data as an enabler of the transformation towards servitization: An action design research approach. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2023, 32, 735–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Sharma, N.K.; Mittal, A.; Verma, P. The role of IoT and IIoT in supplier and customer continuous improvement interface. In Digital Transformation and Industry 4.0 for Sustainable Supply Chain Performance; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannad, H.; Andry, J.F. The Sustainable Logistics: Big Data Analytics and Internet of Things. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2023, 18, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Ward, H.; Tukker, A. How Internet of Things can influence the sustainability performance of logistics industries—A Chinese case study. Clean. Logist. Supply Chain 2023, 6, 100094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parab, S.D.; Deshmukh, A.; Vasudevan, H. Understanding the Drivers and Barriers in the Implementation of IoT in SMEs. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent Manufacturing and Automation, Changsha, China, 22–24 December 2023; pp. 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basit, S.A.; Gharleghi, B.; Batool, K.; Hassan, S.S.; Jahanshahi, A.A.; Kliem, M.E. Review of enablers and barriers of sustainable business practices in SMEs. J. Econ. Technol. 2024, 2, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lone, A.N.; Mustajab, S.; Alam, M. A comprehensive study on cybersecurity challenges and opportunities in the IoT world. Secur. Priv. 2023, 6, e318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baimukhanbetova, E.; Tazhiyev, R.; Sandykbayeva, U.; Jussibaliyeva, A. Digital technologies in the transport and logistics industry: Barriers and implementation problems. Eurasian J. Econ. Bus. Stud. 2023, 67, 82–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulchehra, N. Digital Technologies in Postal Infrastructure. J. Mod. Educ. Achiev. 2023, 7, 173–178. [Google Scholar]

- Boom-Cárcamo, E.; Molina-Romero, S.; Galindo-Angulo, C.; del Mar Restrepo, M. Barriers and strategies for digital marketing and smart delivery in urban courier companies in developing countries. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024, 15, 19203–19232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagopal, R.; Hettiarachchi, C.; Zürn, S.G. Using a Result-Oriented Systems Thinking approach to design and evaluate strategies for the digital transformation management of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Sustain. Manuf. Serv. Econ. 2024, 3, 100023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armenia, S.; Barnabé, F.; Nazir, S. Training Present and Future Generations on Sustainable Development and Digital Transformation Through the Lens of Systems Thinking. In Proceedings of the 16th Annual International Conference of Education, Research and Innovation, ICERI2023 Proceedings, Seville, Spain, 3–15 November 2023; pp. 6605–6613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokgohloa, K.; Kanakana-Katumba, M.G.; Maladzhi, R.W.; Xaba, S. A system dynamics approach to postal digital transformation dynamics: A causal loop diagram (CLD) perspective. South Afr. J. Ind. Eng. 2022, 33, 10–31. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10520/ejc-indeng_v33_n4_a3 (accessed on 2 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Kurti, E.; Salavati, S.; Mirijamdotter, A. Using systems thinking to illustrate digital business model innovation. Systems 2021, 9, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichman, R.G.; Nambisan, S.; Halpern, M. Configurational thinking and value creation from digital innovation: The case of product lifecycle management implementation. In Innovation and IT in an International Context: R&D Strategy and Operations; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2013; pp. 115–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prapinit, P.; Kafi, A.; Osman, N.H.; Melan, M. IoT in Courier Services: Impact on Customer Satisfaction and Supply Chain Sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2024, 19, 671–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavi, R.; Dori, Y.J.; Dori, D. Assessing novelty and systems thinking in conceptual models of technological systems. IEEE Transactions on Education 2020, 64, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giray, G.; Tekinerdogan, B.; Tüzün, E. IoT system development methods. In Internet of Things; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; pp. 141–159. ISBN 9781498778510. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, L.; Li, W.; Wu, H.; Liu, J.; Gao, P. Measuring Corporate digital transformation: Methodology, indicators and applications. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.; George, G. International entrepreneurship: The current status of the field and future research agenda. In Strategic Entrepreneurship: Creating an Integrated Mindset; Hitt, M., Ireland, D., Sexton, D., Camp, M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2002; pp. 255–288. [Google Scholar]

- McKinsey & Company. McKinsey Global Surveys 2021: A Year in Review. 2021. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/featured%20insights/mckinsey%20global%20surveys/mckinsey-global-surveys-2021-a-year-in-review.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- OECD. OECD Digital Economy Outlook 2024 (Volume 2): Strengthening Connectivity, Innovation and Trust; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2024; Volume 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daugherty, P.; Wilson, H.J. Radically Human: How New Technology Is Transforming Business and Shaping Our Future; Harvard Business Press: Brighton, MA, USA, 2022; ISBN 1647821096. [Google Scholar]

- Johri, A.; Asif, M.; Tarkar, P.; Khan, W.; Wasiq, M. Digital financial inclusion in micro enterprises: Understanding the determinants and impact on ease of doing business from World Bank survey. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pillar | Evaluation Criterion | Indicator |

|---|---|---|

| Digital infrastructure | Device connectivity | Share of IoT devices per employee |

| Share of devices connected in real time | ||

| Network availability | Share of company premises covered by high-throughput network | |

| Number of connection outages per month | ||

| Data collection & processing | Data collection automation | Share of sensor-acquired data in total data volume |

| Frequency of data collection | ||

| Data analytics utilization | Share of analytical reports generated monthly | |

| Share of automatically processed data | ||

| Existence of an IoT data management platform | ||

| Share of depts. using IoT data in decision-making | ||

| Integration & interoperability | System connectivity | Share of systems connected via API / middleware |

| Share of IoT systems integrated with ERP/CRM/SCM | ||

| Share of IoT devices connected via cloud services | ||

| Existence of unified data interface for IoT data | ||

| Solution adaptability | Existence of standardized protocol (MQTT, CoAP) | |

| Share of devices supporting remote updates | ||

| Existence of centralized IoT device management across the entire network | ||

| Strategic orientation | IoT investment | Share of IoT-related expenditure in total investment |

| Number of IoT projects implemented in last two years | ||

| Governance & planning | Existence of a company-level IoT strategy | |

| Consideration of IoT data in management d.-making | ||

| Share of employees trained in IoT-related topics | ||

| Existence of a perf. monitoring system for IoT projects | ||

| Existence of regular int. audits of IoT implementation |

| Evaluation Criterion | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Device connectivity | 3.50 | 5.00 | 6.50 | 11.00 | 17.50 | 21.50 | 25.00 | 33.50 | 41.50 | 52.50 |

| Network availability | 54.00 | 56.00 | 58.00 | 47.50 | 51.50 | 42.50 | 44.00 | 63.50 | 70.50 | 75.00 |

| Data collection automation | 2.50 | 3.00 | 14.50 | 17.50 | 31.00 | 45.00 | 46.00 | 64.00 | 68.00 | 72.00 |

| Data analytics utilization | 0.75 | 1.00 | 3.75 | 33.25 | 38.00 | 43.25 | 47.00 | 55.25 | 60.50 | 66.75 |

| System connectivity | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.25 | 3.25 | 34.00 | 37.25 | 38.00 | 45.50 | 51.75 | 57.50 |

| Solution adaptability | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.67 | 70.00 | 73.33 | 77.33 | 80.67 | 83.33 |

| IoT investment | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.50 | 7.50 | 9.50 | 12.50 | 24.00 | 30.50 | 39.00 |

| Governance & planning | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 2.40 | 1.00 | 1.60 | 83.60 | 85.60 | 87.20 |

| Pillar | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digital infrastructure | 28.75 | 30.50 | 32.25 | 29.25 | 34.50 | 32.00 | 34.50 | 48.50 | 56.00 | 63.75 |

| Data collection & processing | 1.63 | 2.00 | 9.13 | 25.38 | 34.50 | 44.13 | 46.50 | 59.63 | 64.25 | 69.38 |

| Integration & interoperability | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.63 | 1.63 | 17.83 | 53.63 | 55.67 | 61.42 | 66.21 | 70.42 |

| Strategic orientation | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.75 | 4.95 | 5.25 | 7.05 | 53.80 | 58.05 | 63.10 |

| Year | Value Added (Y) in € | Depreciation of Fixed Assets (K) in € | Personnel Cost (L) in € |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 3,951,482 | 681,104 | 2,301,879 |

| 2016 | 4,083,907 | 722,537 | 2,394,751 |

| 2017 | 4,051,199 | 741,688 | 2,298,172 |

| 2018 | 4,349,418 | 791,511 | 2,472,689 |

| 2019 | 4,593,821 | 810,346 | 2,485,994 |

| 2020 | 4,703,179 | 771,264 | 2,454,411 |

| 2021 | 4,682,109 | 759,383 | 2,430,178 |

| 2022 | 5,004,568 | 853,910 | 2,543,628 |

| 2023 | 5,002,311 | 943,207 | 2,582,742 |

| 2024 | 5,905,823 | 1,083,661 | 2,701,884 |

| No | Baseline Model | Extended Model | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| ln(K) | 0.33 | 0.29 | −0.04 |

| ln(L) | 1.47 | 0.67 | −0.80 |

| Enterprise | Scenario | γ | p-Value (γ) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DHL | pessimistic | 0.1496 | ✔ | 0.7585 | ✘ |

| realistic | 0.9454 | ✔ | 0.0413 | ✔ | |

| optimistic | 0.4721 | ✔ | 0.0625 | ✘ | |

| DPD | pessimistic | 0.0730 | ✔ | 0.7982 | ✘ |

| realistic | 0.2988 | ✔ | 0.2684 | ✘ | |

| optimistic | 1.0643 | ✔ | 0.0040 | ✔ | |

| GLS | pessimistic | 1.3111 | ✔ | 0.2287 | ✘ |

| realistic | 1.0083 | ✔ | 0.0022 | ✔ | |

| optimistic | 0.6620 | ✔ | 0.2513 | ✘ | |

| Packeta | pessimistic | 0.4725 | ✔ | 0.1015 | ✘ |

| realistic | 0.1668 | ✔ | 0.7233 | ✘ | |

| optimistic | 0.1863 | ✔ | 0.2393 | ✘ | |

| SPS | pessimistic | −0.4350 | ✘ | 0.4350 | ✘ |

| realistic | 0.4965 | ✔ | 0.3346 | ✘ | |

| optimistic | 0.2235 | ✔ | 0.2240 | ✘ | |

| TNT | pessimistic | 0.1503 | ✔ | 0.6176 | ✘ |

| realistic | 0.1578 | ✔ | 0.7152 | ✘ | |

| optimistic | 0.6965 | ✔ | 0.0067 | ✔ |

| Enterprise | Scenario | SSE (Baseline) | SSE (Extended) | F | p-Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DHL | pessimistic | 0.021485 | 0.000063 | 2732.39 | 1.99 × 10−11 | H0 not accepted |

| realistic | 0.021485 | 0.000087 | 1964.88 | 7.41 × 10−11 | H0 not accepted | |

| optimistic | 0.021485 | 0.000063 | 2732.39 | 1.99 × 10−11 | H0 not accepted | |

| DPD | pessimistic | 0.262331 | 0.000077 | 27,289.73 | 2.00 × 10−15 | H0 not accepted |

| realistic | 0.262331 | 0.000067 | 31,184.77 | 1.22 × 10−15 | H0 not accepted | |

| optimistic | 0.262331 | 0.000026 | 80,958.41 | 1.11 × 10−16 | H0 not accepted | |

| GLS | pessimistic | 0.080606 | 0.000110 | 5879.91 | 9.32 × 10−13 | H0 not accepted |

| realistic | 0.080606 | 0.000023 | 27,883.19 | 1.89 × 10−15 | H0 not accepted | |

| optimistic | 0.080606 | 0.000134 | 4787.09 | 2.12 × 10−12 | H0 not accepted | |

| Packeta | pessimistic | 0.114749 | 0.000018 | 26,016.16 | 8.86 × 10−9 | H0 not accepted |

| realistic | 0.114749 | 0.000041 | 11,201.95 | 4.78 × 10−8 | H0 not accepted | |

| optimistic | 0.114749 | 0.000005 | 94,829.81 | 6.67 × 10−10 | H0 not accepted | |

| SPS | pessimistic | 0.187342 | 0.000040 | 32,517.59 | 4.25 × 10−14 | H0 not accepted |

| realistic | 0.187342 | 0.000081 | 16,199.02 | 4.88 × 10−13 | H0 not accepted | |

| optimistic | 0.187342 | 0.000007 | 187,334.64 | 1.11 × 10−16 | H0 not accepted | |

| TNT | pessimistic | 0.088198 | 0.000023 | 30,510.25 | 1.33 × 10−15 | H0 not accepted |

| realistic | 0.088198 | 0.000058 | 12,090.46 | 5.23 × 10−14 | H0 not accepted | |

| optimistic | 0.088198 | 0.000014 | 52,180.01 | 1.11 × 10−16 | H0 not accepted |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kováčiková, K.; Baláž, M.; Kováčiková, M.; Novák, A. Systemic Assessment of IoT Readiness and Economic Impact in Postal Services. Systems 2025, 13, 910. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13100910

Kováčiková K, Baláž M, Kováčiková M, Novák A. Systemic Assessment of IoT Readiness and Economic Impact in Postal Services. Systems. 2025; 13(10):910. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13100910

Chicago/Turabian StyleKováčiková, Kristína, Martin Baláž, Martina Kováčiková, and Andrej Novák. 2025. "Systemic Assessment of IoT Readiness and Economic Impact in Postal Services" Systems 13, no. 10: 910. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13100910

APA StyleKováčiková, K., Baláž, M., Kováčiková, M., & Novák, A. (2025). Systemic Assessment of IoT Readiness and Economic Impact in Postal Services. Systems, 13(10), 910. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13100910